Abstract

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) regulates both oxidative stress and mitochondrial biogenesis. Our previous study reported the cardioprotection of calycosin against triptolide toxicity through promoting mitochondrial biogenesis by activating nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), a coregulatory effect contributed by Nrf2 was not fully elucidated. This work aimed at investigating the involvement of Nrf2 in mitochondrial protection and elucidating Nrf2/NRF1 signaling crosstalk on amplifying the detoxification of calycosin. Results indicated that calycosin inhibited cardiomyocytes apoptosis and F-actin depolymerization following triptolide exposure. Cardiac contraction was improved by calycosin through increasing both fractional shortening (FS%) and ejection fraction (EF%). This enhanced contractile capacity of heart was benefited from mitochondrial protection reflected by ultrastructure improvement, augment in mitochondrial mass and ATP production. NRF1 overexpression in cardiomyocytes increased mitochondrial mass and DNA copy number, whereas NRF1 knockdown mitigated calycosin-mediated enhancement in mitochondrial mass. For nuclear Nrf2, it was upregulated by calycosin in a way of disrupting Nrf2-Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1) interaction, followed by inhibiting ubiquitination and degradation. The involvement of Nrf2 in mitochondrial protection was validated by the results that both Nrf2 knockdown and Nrf2 inhibitor blocked the calycosin effects on mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration. In the case of calycosin treatment, its effect on NRF1 and Nrf2 upregulations were respectively blocked by PGCα/Nrf2 and NRF1 knockdown, indicative of the mutual regulation between Nrf2 and NRF1. Accordingly, calycosin activated Nrf2/NRF1 and the signaling crosstalk, leading to mitochondrial biogenesis amplification, which would become a novel mechanism of calycosin against triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10565-024-09969-z.

Keywords: Calycosin, Triptolide, Mitochondrial biogenesis, NRF1, Nrf2

Introduction

Triptolide (TP), the potential antitumor candidate (Noel et al. 2019), possesses multiorgan toxicity especially cardiotoxicity, which limits its development in clinical application (Xi et al. 2017). Abundant evidences have indicated that mitochondrial dysfunction is the prominent hallmark of TP-induced cardiotoxicity (Xi et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2014). Mitochondria are key organelles that play a major role in energy production in cardiomyocytes, and vital to maintain cellular homeostasis due to regulating multiple biochemical processes including intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, redox homeostasis, as well as controlling pathways involved in cell survival (Bonora et al. 2019). Based on these diverse effects, mitochondrial deficiency in structure and function may lead to contractile dysfunction (Wu et al. 2022a), which results in the onset of cardiotoxicity induced by triptolide (Qi et al. 2023). Calycosin, the potential cardiovascular protective agent (Deng et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2022), was previously demonstrated to attenuate triptolide-induced cardiac impairment by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis (Qi et al. 2023).

Mitochondrion is the self-renewal organelle called mitochondrial biogenesis that new mitochondria are generated and separated from the ones already existing (Popov 2020), usually in response to higher energy demand. NRF1 is the firstly discovered regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (Scarpulla et al. 2012), which plays the critical role in transcriptional regulation of nuclear genome encoded mitochondrial proteins, including subunits of the five respiratory complexes (Kelly and Scarpulla 2004), members responsible for mtDNA transcription (Huo and Scarpulla 2001) and replication such as TFAM (transcription factor A, mitochondrial) (Piantadosi and Suliman 2006), and components of mitochondrial protein transport apparatus like TOM20 (Outer mitochondrial membrane 20) (Kelly and Scarpulla 2004). Additionally, NRF1 is responsible for stabilizing mtDNA copy number (Huo and Scarpulla 2001), simultaneously increasing mtDNA encoded mitochondrial protein expression. Our previous study indicated that NRF1 was significantly upregulated by calycosin (Qi et al. 2023), resulting in mitochondrial biogenesis promotion, but the potential regulatory mechanism remained to be clarified.

Nrf2 is widely recognized as a primary regulator for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis that positively regulates the transcription of antioxidant enzyme by binding to antioxidant responsive element (ARE) (Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova 2014). In addition to antioxidant, Nrf2 is also a modulator for mitochondrial biogenesis (Esteras and Abramov 2022; Merry and Ristow 2016; Dinkova-Kostova and Abramov 2015). Pantadosi (Piantadosi et al. 2008) demonstrated that Nrf2 was able to positively regulate NRF1 by binding to the ARE sequences presented in the region of Nrf1 gene. Moreover, Tfam, the representative NRF1 target gene was also upregulated by Nrf2 activation (Merry and Ristow 2016). Pharmacological activation of Nrf2 with DMF, the firstly approved Nrf2 activator in clinics, enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and function (Hayashi et al. 2017), whereas Nrf2 deficiency led to mitochondrial content reduction (Zhang et al. 2013). These findings indicated that Nrf2 modulates the two important cytoprotective pathways, antioxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis protection. Nrf2 was activated by calycosin for oxidative stress alleviation (Lu et al. 2022). However, the involvement of Nrf2 in calycosin-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis promotion was not investigated.

Nrf2 is tightly regulated through multiple mechanism, among which Keap1, the substrate adaptor protein for Cullin 3 (Cul3)/Rbx1 ubiquitin ligase, is the most well-known negative regulator (Ulasov et al. 2022). Under basal condition, Nrf2 is mainly located in cytoplasm by binding to Keap1, facilitating to be continuously degraded by ubiquitylation-proteasomal systems. Disturbance of Nrf2-Keap1 interaction results in a rapid accumulation of Nrf2 in cytoplasm, followed by translocating into the nucleus to form a heterodimer with a small Maf protein, which contributes to binding to the ARE sequence of target gene and initiating the transcription (Ulasov et al. 2022). Whether this direct interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1 is disturbed by calycosin needs further investigation. Nrf2 is positively regulated by PGC-1α, the coactivator for multiple transcription factor, through direct interaction in nucleus for target gene transcription, such as Nrf1 (Li et al. 2021). In addition to Nrf2, NRF1 was also coactivated by PGC-1α for mitochondrial biogenesis-related gene transcription, which has been confirmed to be the underlying mechanism for calycosin inducing mitochondrial protection in our present study (Qi et al. 2023). PGC-1α-mediated coactivation in both NRF1 and Nrf2 might trigger the crosstalk between these two transcription factors, eventually resulting in mitochondrial biogenesis amplification.

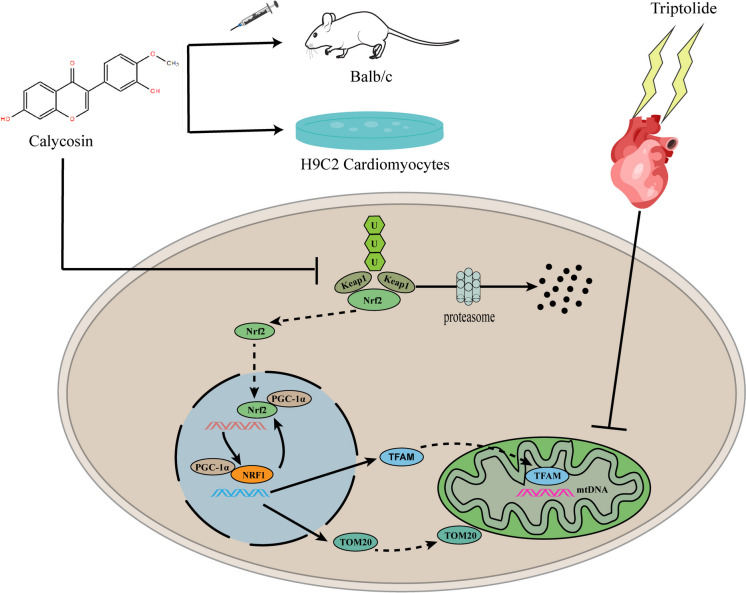

Here we reported that Nrf2 was activated by calycosin through disrupting Nrf2-Keap1 interaction, followed by inhibiting ubiquitination and degradation. Nrf2 accumulated in cytoplasm and then translocated to nucleus where it interacted with PGC-1α for initiating Nrf1 transcription. The upregulated NRF1 was further activated by PGC-1α for mitochondrial biogenesis promotion. NRF1 upregulation reactivated Nrf2, which established a positive feedback loop, resulting in mitochondrial biogenesis amplification. Therefore, the activation of Nrf2/NRF1 signaling crosstalk would facilitate calycosin to become a promising agent for cardiotoxicity treatment.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatment

Male Balb/c mice (6 ~ 8 weeks) obtained from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) were placed in the condition with relative stable temperature (24 ± 2 ℃) and humidity (50 ± 5%) in a 12 h light/dark cycle. The mice were freely obtained food and water. All procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of animal ethics and protocols of Shanxi university of Chinese medicine (AWE202403129).

Thirty mice were randomly and averagely divided into five groups with six mice each. The mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of calycosin once daily for constant 28 days at the concentration of 2, 4 and 8 mg/kg respectively. Following calycosin last injection, triptolide (1.5 mg/kg) was used to establish cardiotoxicity by a single intraperitoneal injection in mice. After 24 h, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane for cardiac echocardiography determination. Calycosin at 4 mg/kg could significantly protect against triptolide-induced cardiac contraction dysfunction. In the following experiment, 4 mg/kg was chosen for investigating mitochondrial protection of calycosin.

ML385 (# HY-100523, Med Chem Express, USA) was used to investigate the involvement of Nrf2 in calycosin-mediated protection in mitochondria. Twenty-four mice were randomly and averagely divided into four groups with six mice each. Mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of calycosin (4 mg/kg) once daily for constant 28 days. After the last injection, mice were exposed to a single intraperitoneal injection of triptolide (1.5 mg/kg). ML385(30 mg/kg) were intraperitoneally injected in mice from the fourteenth day of calycosin injection once every two days for consecutive 7 injections. 24 h later following triptolide injection, the mice were deeply anesthetized and their hearts were immediately harvested for mitochondrial respiration detection. The harvested heart was frozen in liquid nitrogen with one part and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde with another part.

Echocardiography

Cardiac contraction was determined by echocardiography in Vero-LAZR-X micro-ultrasound system. Mice were deeply anesthetized in 1.5% isoflurane. Echocardiography of the left ventricle was obtained by slowly adjusting the ultrasound beam. Left ventricular function, including fractional shortening (FS%), ejection fraction (EF%), stroke volume and cardiac output was evaluated from M-mode images.

Transmission electron microscopy

The freshly harvested heart tissues were rapidly fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 ℃ for 2 h and washed with PBS. Hearts were post-fixed in 1% osmic acid at room temperature for 2 h. Following gradient dehydration, tissues were embedded and sliced. The ultramicrocut was stained in 3% uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 15 min and then visualized in transmission electron microscopy (HITACHI, HT7700) to obtain high resolution mitochondrial images.

Mitochondrial respiration detection

Mitochondrial respiration was detected with high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2 k, Oroboros, Austria). In brief, the freshly harvested heart tissues (10 mg) were homogenized using a Dounce tissue grinder with 200 μL MiR05 (60101–01, Oroboros, Austria). Then 50 µL homogenates were used to determine mitochondrial respiration. Briefly, glutamate (G, 20 mM, Oroboros, Austria), malate (M, 4 mM, Oroboros, Austria) and ADP (D, 1.5 mM, Oroboros, Austria) were sequentially added to determine complex I leak and complex I phosphorylation respiration. Succinate (S, 10 mM, Oroboros, Austria) was used for complex II phosphorylation respiration determination. Oligomycin (Omy, 0.03 µM, Oroboros, Austria), CCCP (U, 0.2–0.3 µM, Oroboros, Austria) and rotenone (Rot, 10 µM, Oroboros, Austria) were respectively used for determining ATP production, maximal uncoupled respiration of electron transfer system and CII ETS. Additionally, antimycin A (AA, 2.5 μM, Oroboros, Austria) was administrated to measure residual oxygen consumption (ROX). Finally, ascorbate and TMPD (As + Tm, 2 mM and 0.5 mM, respectively, Oroboros, Austria) were added to determine complex IV-related phosphorylation respiration. These data were recorded in DatLabacquisition software 5.2 (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria).

Cell culture and treatment

H9C2 cardiomyocytes obtained from “Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences” were cultured in DMEM (12100061, Thermo Fisher, USA), consisting of 10% FBS (A5670801, Thermo Fisher, USA), 100 U/L penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (P1400, Solarbio, China). Triptolide (CAS:38748–32-2, purity ≥ 98%, #A0104, Chengdu Must Biotechnology Co., LTD) (200 nM) treatment for 24 h was used to induce toxicity in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. H9C2 cardiomyocytes were simultaneously exposed to different concentration of calycosin (CAS:20575–57-9, purity ≥ 98%, #A0514, Chengdu Must Biotechnology Co., LTD) (50, 100 and 200 μM) for investigating the protection of calycosin against triptolide-induced cardiomyocyte toxicity.

Cycloheximide (CHX, #HY-12320, Med Chem Express, USA) was used to observe Nrf2 degradation among groups. H9C2 cardiomyocytes treated by CHX (50 μM) were simultaneously interfered with triptolide (200 nM) or triptolide (200 nM) plus calycosin (200 μM) for 0, 2, 4, 8 and 12 h respectively.

MG132 (#HY-13259, Med Chem Express, USA), the proteasome inhibitor, was introduced to investigate the involvement of ubiquitination in the distinct expression of Nrf2 among groups. H9C2 cardiomyocytes with MG132 (10 μM) treatment were concurrently treated with triptolide or triptolide plus calycosin for 24 h.

F:actin and G:actin detection

H9C2 cardiomyocytes were washed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. After that, H9C2 cardiomyocytes were simultaneously stained with phalloidin (0.165 μM, 40737ES75, Yeasen Biotechnology, China) and deoxyribonuclease (0.3 μM, D12371, Thermo Fisher, USA) for 90 min at room temperature. DAPI (1:2000, 62249, Thermo Fisher, USA) was used for staining cell nucleus. ImageXpress Micro 4 (Molecular Devices, USA) was used for F:actin and G:actin visualization. The fluorescence intensity of F:actin and G:actin was analyzed and calculated by the software in ImageXpress Micro 4.

Western blotting

Proteins in cardiomyocytes and heart tissues were obtained by RIPA lysis buffer (AR0102, Boster Biological Technology, China) in which 1 mM PMSF (AR1178, Boster Biological Technology) and proteinase inhibitor (04693116001, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were added. The total protein was harvested by collecting the supernatants after centrifuging lysates at 13,000 × g for 15 min. Protein concentration was determined by BCA kit (AR0197, Boster Biological Technology). Nuclear proteins of H9C2 cardiomyocytes were extracted using the commercial Kit (P0028, Beyotime, China). 20 μg protein were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by transferring to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, California, USA). The transferred membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk for 4 h at room temperature, and then incubated with specific primary antibody (anti-Bax, 1:1000, 50599–2-Ig, Proteintech; anti-Keap1, 1:1000, 10503–2-AP, Proteintech; anti-ubiquitin, 1:1000, 10201–2-AP, Proteintech; anti-actin, 1:1000, 20536–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-BcL-2, 1:1000, 26593–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-caspase-3, 1:1000, 9662, cell signaling technology; anti-TOM20, 1:1000, 11802–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-NRF1, 1:1000, ab175932, Abcam; anti-Nrf2, 1:1000, 16396–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-TFAM, 1:2000, 22586–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-PGC-1α, 1:1000, PA5-72948, Thermo Fisher; anti-LaminB, 1:5000, A16909, ABclonal; anti-GAPDH, 1:3000, AP0063, Bioworld Technology; anti-HO-1, 1:1000, 10701–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-NQO1, 1:1000, 11451–1-AP, Proteintech) overnight at 4 ℃, followed by incubating with HRP conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, 60382121, Thermo Fisher) for 90 min at room temperature. Western blot bands were determined by using ECL kit (RPN2232, Cytiva, USA) on an Amersham Imager 600 (Cytiva).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed to investigate the expression and visualize the distribution of Nrf2 and TOM20 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. H9C2 cardiomyocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min, followed by blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. After that, cardiomyocytes were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-TOM20, 1:200, 11802–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-Nrf2, 1:200, 16396–1-AP, Proteintech; anti-Keap1, 1:200, 60027–1-Ig, Proteintech; anti-PGC-1α, 1:200, 66369–1-Ig, Proteintech) overnight at 4℃, followed by incubating with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (1:500, ab150077, Abcam) or goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 647) (1:500, ab150115, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Cell nucleus was stained by DAPI. The expression of related proteins was visualized using ImageXpress Micro 4 and laser scanning confocal microscope (FV1000, OLYMPUS, Japan).

The expression of Nrf2 and NRF1 in heart tissues were also measured by immunofluorescence. The freshly harvested heart tissues were embedded with OCT, followed by quick-frozen with liquid nitrogen. Heart cryosections at 4 μM thickness were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by permeabilization with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Then the cryosections were blocked in 1% BSA for 1 h. After that, the slices were immune-stained with anti-Nrf2(1:200, 16396–1-AP, Proteintech) and anti-NRF1(1:200, ab175932, Abcam) at 4 ℃ overnight. After primary antibody incubation, the slices were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) for 1 h at room temperature. The cryosections were further stained with DAP1 for 5 min to observe cell nucleus. Then the slices were viewed on laser scanning confocal microscope.

ATP measurement in H9C2 cardiomyocytes and heart tissues

H9C2 cardiomyocytes and heart tissues were lysed, and the ATP content was measured using an enhanced ATP assay kit (S0027, Beyotime). The procedure was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative RT-PCR

TRIZOl reagent (108–95-2, TaKaRa, Japan) was used for total RNA extraction. The RNA was reverse transcription to cDNA by TaqMan Reverse Reagents (RR047A, TaKaRa). Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted with a Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master (RR820A, TaKaRa) on 7900HT Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA). Gene expressions were measured by 2−ΔΔCt quantification method. Primer sequences were shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Measurement of mtDNA copy number

DNeasy Kit (69504, QIAGEN, Germany) was used to extracted total DNA in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA expression of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) that encoded by mtDNA was measured by qRT-PCR, and normalized by GAPDH. The primer sequences were shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Transfection

H9C2 cardiomyocyte with 70–80% confluence was transfected with siRNA for Nrf1, Nfe2l2 and Ppargc1α knockdown respectively by using transfection reagent and related-siRNA (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd). The siRNA sequences were presented below:

siNrf1: 5′-GAGCCACAUUAGAUGAAUATT-3′;

si Nfe2l2: 5′-GGAGGCAAGACAUAGAUCUTT-3′;

siPpargc1α: 5′-GCCAAACCAACAACUUUAUTT-3′;

siNC: 5′-UUCUUCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′.

Nrf1 was overexpressed by transfecting pcDNA 3.1-Nrf1 plasmid with Lipofectamine 2000 (11668019, Thermo Fisher, USA) in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. After transfection the cells were cultured in DMEM for 6 h, followed by incubation in complete DMEM consisting of 10% FBS for another 48 h.

Co-immunoprecipitation and ubiquitination assay

Co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP) assay was conducted according to the protocol of a commercial Kit (26146, Thermo Fisher). H9C2 cardiomyocytes were lysed and centrifuged to harvest supernatants. Protein concentration was quantified by BCA kit. Control agarose resin was used to bind 1 mg protein of supernatants to avoid nonspecific binding at 4 ℃ for 2 h. Following that, anti-Nrf2 (1:100, 16396–1-AP, Proteintech) and anti-normal IgG (2729, Cell Signaling Technology) was added for antigen–antibody combination at 4 ℃ overnight. For ubiquitination assay, the incubated antibody was changed to anti-ubiquitin (1:100, 80992–1-RR, Proteintech). The immunoprecipitations were exposed to 20μL protein A + G agarose beads for 4 h. After washing, the beads were then boiled with loading buffer and evaluated by immunoblotting analysis.

Dual luciferase assay

Nrf1 promoter (form −2,000 bps upstream of TSS to 111bps downstream of TSS) was synthesized by Hanbio Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). 293 T cells with the confluence of 70–80% were simultaneously transfected with plasmids of pGL3-basis and pRL-SV40-Renilla by using LipoFiterTM (Hanbio Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), in combination with pcDNA 3.1-Nfe2l2 plasmid or not. After transfecting for 48 h, the lysates were obtained by passive lysis buffer. Dual-luciferase substrate system (Hanbio Biotechnology) was used to simultaneously detect the activities of both firefly luciferase and renilla luciferase.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 22.0) was used to analyze experimental results. Statistical significance between two groups was analyzed by t-test, and one-way ANOVA was used for more group comparison. Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 indicates for statistically significance, and P < 0.01 for extremely significance.

Results

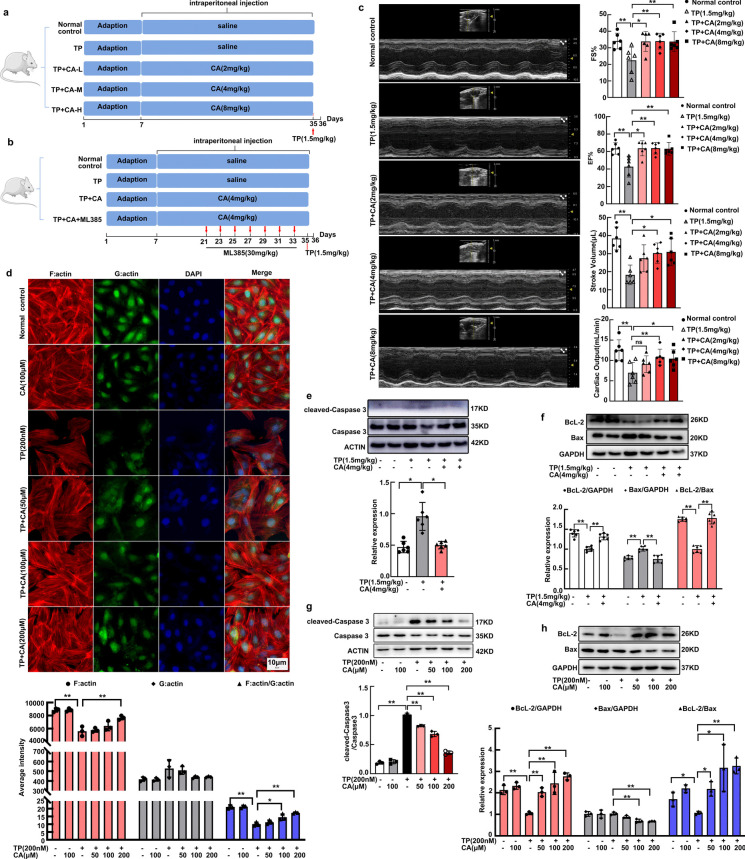

Protection of calycosin against triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity

Triptolide-induced cardiac pathological changes have been investigated in previous study, we focused on cardiac contraction here. Both FS% and EF%, the golden indexes for cardiac contractile capacity were significantly impaired by triptolide, leading to stroke volume and cardiac output reduction. After calycosin treatment, FS% and EF% were significantly recovered, accompanied by the restoration of stroke volume and cardiac output (Fig. 1c). Cardiomyocytes contraction is initiated by mutual slipping between thin filament and thick filament. The precise assembly of actin-based thin filaments is crucial for cardiomyocytes contraction. We further investigated the actin dynamics of H9C2 cardiomyocytes by labeling F:actin with Phalloidin and G:actin with Deoxyribonuclease. Results indicated that actin cytoskeleton was impaired in triptolide-induced H9C2 cardiomyocytes which was characterized by F:actin depolymerization (Fig. 1d). After calycosin treatment, F:actin polymerization was dose-dependently restored (Fig. 1d). Heart apoptosis was dramatically induced by triptolide as reflected by the increased ratio of cleaved-caspase3 to caspase 3 (Fig. 1e) and decreased ratio of BcL-2 to Bax (Fig. 1f). In addition, H9C2 cardiomyocytes apoptosis was observed after triptolide exposure, reflected by increased expression of cleaved-caspase3 (Fig. 1g) and Bax (Fig. 1h), accompanied with the decreased expression of BcL-2 (Fig. 1h). The apoptosis in vivo (Fig. 1e, f) and in vitro (Fig. 1g, h) were significantly alleviated by calycosin. In conclusion, triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity was significantly improved by calycosin.

Fig. 1.

Calycosin attenuated triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity. (a, b) The visual diagram of experimental procedure. (c) Balb/c mice were treated with triptolide (1.5 mg/kg) alone or in combination with calycosin at diverse concentrations (2 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg, or 8 mg/kg), cardiac function was examined by echocardiography. FS%, EF%, stroke volume and cardiac output were calculated. (d) H9C2 cardiomyocytes were interfered with triptolide in presence or absence of calycosin, the cytoskeleton was visualized. And the F:actin, G:actin and F:actin/G:actin were determined to analyze the degree of microfilament polymerization among groups. The fluorescence intensity was calculated by software in ImageXpress Micro 4. (e, f) The expression of apoptosis-related protein (caspase 3, cleaved-caspase 3, Bax and BcL-2) in heart tissues were determined by western blot. (g, h) The expression of apoptosis-related protein (caspase 3, cleaved-caspase 3, Bax and BcL-2) in cardiomyocytes were determined by western blot. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

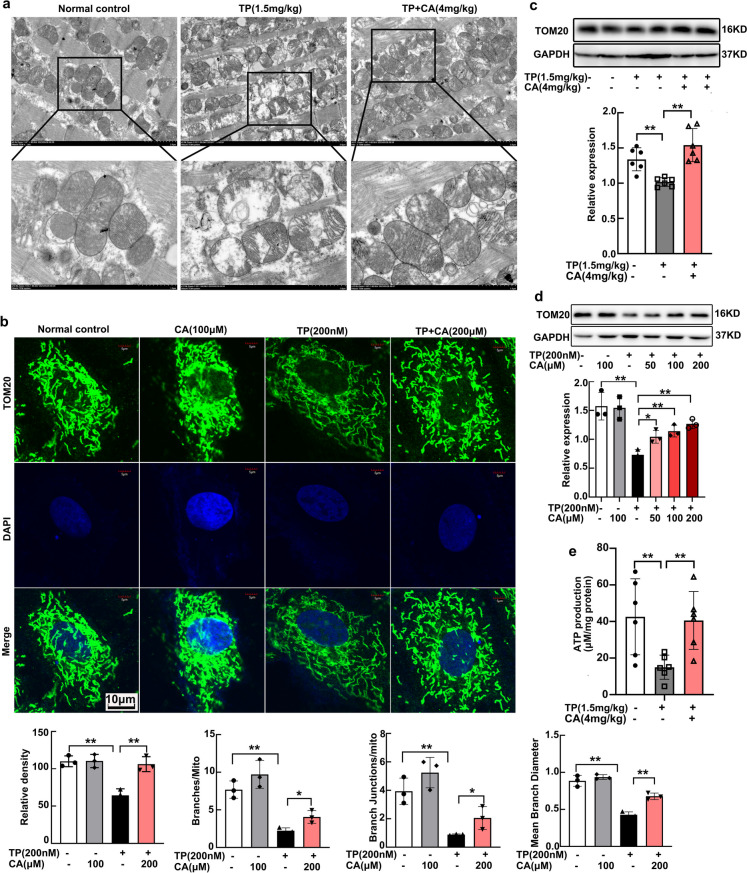

Triptolide-induced cardiac mitochondrial impairment was alleviated by calycosin

Mitochondrial dysfunction has a direct detrimental effect on cardiac contraction and apoptosis. Herein we investigated the mitochondrial mass and structure in vivo and in vitro. Mitochondrial ultrastructure of heart tissues was visualized by transmission electronic microscopy. Triptolide induced mitochondrial swelling, loss of cristae and formation of internal vesicles (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescent staining of TOM20, the mitochondrial outer membrane protein, was conducted for mitochondrial structure illustration of cardiomyocytes. After triptolide intervention, mitochondrial branch was significantly impaired, reflected by the decreased amount of mitochondrial branch, reduction in branch junction and mean branch diameter. These indicated that the mitochondria were elongated and loosen by triptolide, leading to less connection between each other (Fig. 2b). The impairment of mitochondrial structure both in vivo and in vitro was significantly alleviated by calycosin (Fig. 2a, b). Mitochondrial mass has been analyzed by Mito-tracker staining in our previous study, and was detected by TOM20 expression here. TOM20 expression in heart tissues and in H9C2 cardiomyocytes were significantly repressed by triptolide, and restored by calycosin (Fig. 2c, d). The dysregulation of both mitochondrial content and structure directly resulted in energy generation deficiency. Triptolide declined ATP production in heart tissues, while calycosin recovered it almost identical to the normal control (Fig. 2e). Accordingly, calycosin significantly attenuated triptolide-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction.

Fig. 2.

Calycosin attenuated triptolide-induced cardiac mitochondria dysfunction. (a) Mitochondrial ultrastructure in heart tissues were visualized by transmission electron microscope (TEM). (b) Mitochondria in H9C2 cardiomyocytes were stained with TOM20 and visualized by confocal microscopy, fluorescence intensity and the mitochondrial structure were respectively calculated and analyzed by ImageJ. (c, d) The expression of TOM20 in heart tissues and H9C2 cardiomyocytes were determined by western blot. (e) ATP production in heart tissues were measured by chemiluminescence. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

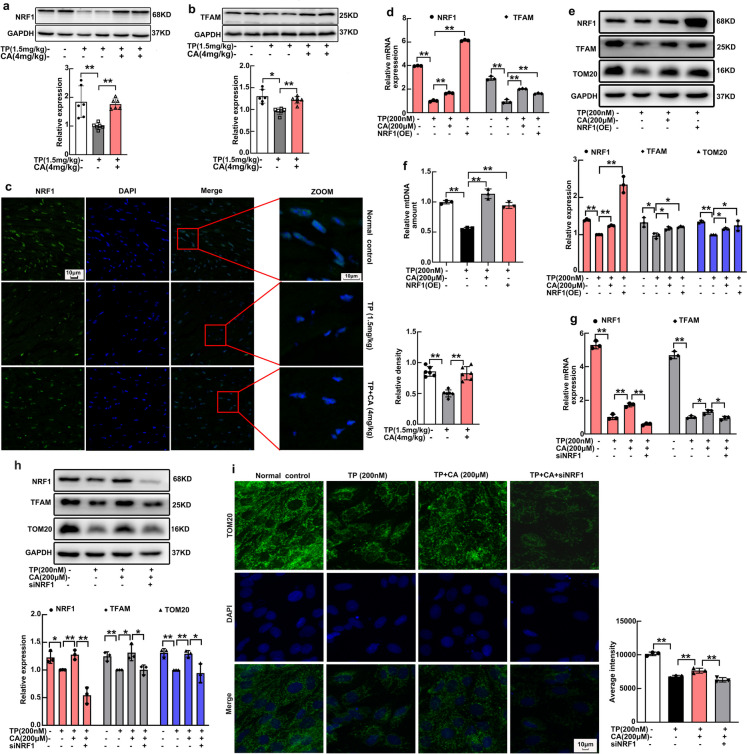

Calycosin enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis in NRF1-dependent manner

NRF1 expression in H9C2 cardiomyocytes has been confirmed to be repressed by triptolide and recovered by calycosin in our previous study. In this present study, we further determined the expression of NRF1 in heart tissues. Triptolide also significantly reduced heart expression of NRF1 (Fig. 3a), followed by downregulation of TFAM (Fig. 3b), the representative NRF1 target gene. After calycosin treatment, the expression of both NRF1 and TFAM were significantly recovered (Fig. 3a, b). Immunofluorescent staining manifested the same result that NRF1 expression in heart tissues were decreased by triptolide and increased by calycosin (Fig. 3c). To investigate the involvement of NRF1 in calycosin-triggered mitochondrial protection, NRF1 overexpression in H9C2 cardiomyocytes was generated. NRF1 was successfully overexpressed in H9C2 cardiomyocytes both at mRNA (Fig. 3d) (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and protein levels (Fig. 3e) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The mRNA of TFAM was also upregulated following NRF1 overexpression (Fig. 3d), along with protein expression of TOM20 and TFAM (Fig. 3e), as well as mtDNA copy number (Fig. 3f) increase. The protective effect of NRF1 overexpression on mitochondrion was similar with that of calycosin. Verso validation was simultaneously conducted to further investigate the critical role of NRF1 in calycosin-mediated mitochondrial protection. NRF1 was also successfully knockdown by siNrf1 (Fig. 3g, h). The enhancement of calycosin in TFAM (Fig. 3g, h) and TOM20 (Fig. 3h, i) expression were significantly abrogated by siNrf1. Above results all demonstrated that NRF1 is closely involved in the protection of calycosin in mitochondrial biogenesis.

Fig. 3.

NRF1 expression and NRF1-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis were promoted by calycosin. (a) NRF1 expression in heart tissues were determined by western blot. (b) TFAM expression in heart tissues were determined by western blot. (c) NRF1 expression in heart tissues were visualized by immunofluorescent staining, fluorescence intensity was calculated by ImageJ. (d) The mRNA expression of Nrf1 and Tfam in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 overexpression was measured by qRT-PCR. (e) Mitochondrial mass (TOM20 expression), together with TFAM expression in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 overexpression was determined by western blot. (f) Mitochondrial mtDNA copy number in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 overexpression was determined by qRT-PCR. (g) The mRNA expression of Nrf1 and Tfam in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 knockdown was measured by qRT-PCR. (h) The expression of NRF1, TFAM and TOM20 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 knockdown was determined by western blot. (i) Mitochondrial mass in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf1 knockdown was visualized by immunofluorescent staining of TOM20, fluorescence intensity was calculated by software in ImageXpress Micro 4. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

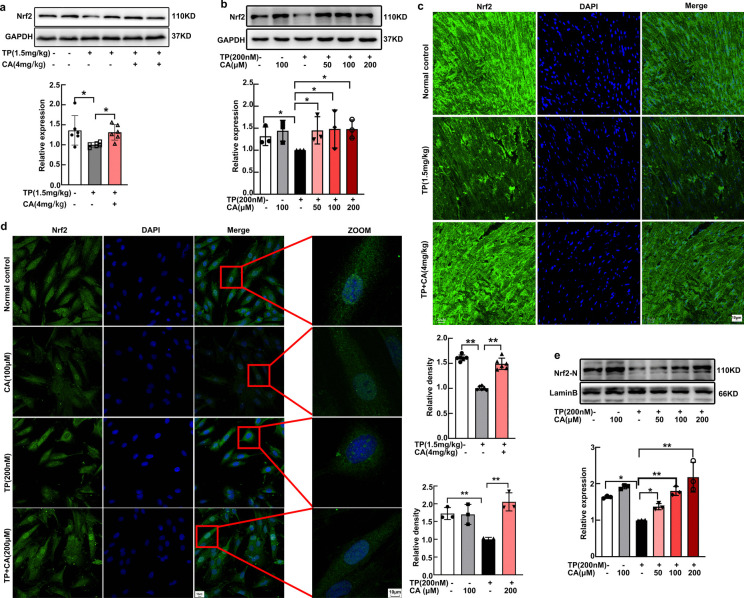

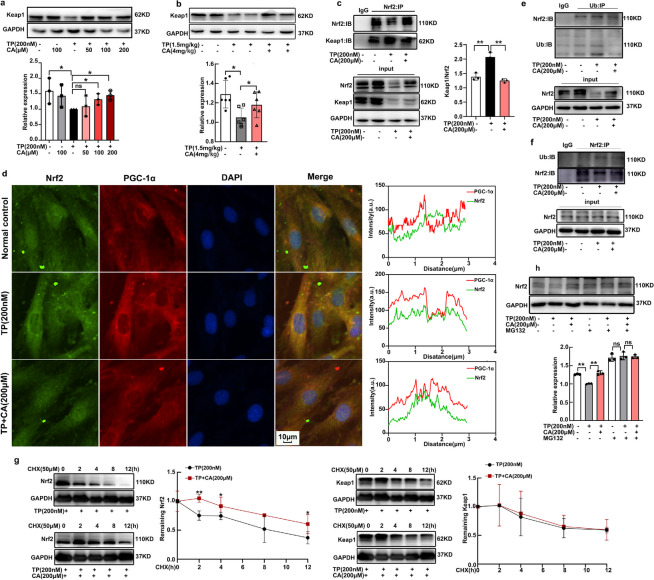

Nrf2 was activated by calycosin through disturbing Nrf2-Keap1 interaction and decreasing the ubiquitination and degradation

Calycosin was demonstrated to attenuated triptolide-induced NRF1 downregulation in our previous research, but the underlying mechanism still needs further investigation. Nrf2 was reported to control the expression of NRF1. Hence, we focus on the impact of calycosin on Nrf2 expression. Calycosin significantly improved triptolide-induced Nrf2 downregulation in heart tissues, as reflected by both western blot (Fig. 4a) and immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 4c). The total Nrf2 expression was also increased by calycosin in triptolide-treated H9C2 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4b). Since Nrf2 was a transcription factor, we focused on the distribution of Nrf2 in nucleus. Calycosin dose-dependently increased nuclear Nrf2 distribution (Fig. 4e), as manifested by western blot. To clearly visualize the flexible location of Nrf2 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes among groups, immunofluorescent staining was conducted. In normal condition, Nrf2 could be observed in both nucleus and cytoplasm, then Nrf2 was scattered out of nucleus after triptolide intervention, following calycosin treatment Nrf2 was redistributed in nucleus again (Fig. 4d). This accumulation of Nrf2 in nucleus enhanced the expression of HO-1(Supplementary Fig. 2a) and NQO1 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), the widely recognized Nrf2 target gene. In conclusion, Nrf2 was significantly activated by calycosin in triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity.

Fig. 4.

Nrf2 was activated by calycosin in triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity. (a) Nrf2 expression in heart tissues were determined by western blot. (b) Total expression of Nrf2 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes was determined by western blot. (c) Nrf2 expression in heart tissues were visualized by immunofluorescent staining, fluorescence intensity was calculated by ImageJ. (d) Nrf2 distribution in nucleus was visualized by immunofluorescent staining, fluorescence intensity was calculated by ImageJ. (e) The expression of Nrf2 in nucleus was determined by western blot. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

Nrf2 was regulated by varying signals, of which Keap1 was considered as the main negative regulator. Therefore, we determined the effect of calycosin on Keap1 expression in triptolide-treated H9C2 cardiomyocytes and heart tissues. On contrary to our hypothesis that triptolide upregulated Keap1 and calycosin downregulated it for Nrf2 stabilization, triptolide reduced Keap1 expression and calycosin restored it (Fig. 5a, b). To understand the regulatory mechanism, we examined the direct Nrf2-Keap1 interaction among groups by CoIP assay. Results indicated that Nrf2-Keap1 interaction was enhanced by triptolide and disrupted by calycosin (Fig. 5c). In addition, dual immunofluorescence staining of Nrf2 and Keap1 was conducted to visualize Nrf2-Keap1 colocalization in cardiomyocytes among groups. Keap1 mainly located in cytoplasm no matter in normal condition or after triptolide and calycosin treatment. Nrf2 mainly distributed in nucleus in normal condition. After triptolide intervention, the distribution was increased in cytoplasm, which facilitated Nrf2-Keap1 colocalization (Fig. 5d). Following calycosin treatment, Nrf2 was relocated in nucleus, leading to disturbing this colocalization (Fig. 5d). The change of Nrf2-Keap1 interaction directly resulted in the alteration of Nrf2 ubiquitination. Triptolide induced Nrf2 ubiquitination, and calycosin decreased the ubiquitination (Fig. 5e, f). When protein synthesis was disrupted by CHX, the degradation of Nrf2 and Keap1 were determined from 2 to 12 h. The degradation rates of Keap1 were equivalent in triptolide-treated and triptolide plus calycosin-treated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5g). On the contrary, Nrf2 degradation was significantly inhibited by calycosin (Fig. 5g). To further confirm the involvement of ubiquitination in Nrf2 degradation in this experiment. MG132, the proteasome inhibitor, was used to prevent the degradation of Nrf2. After MG132 exposure, the expression of Nrf2 was increased no matter in normal control group or in triptolide treated- and triptolide + calycosin treated-groups. Importantly, the expression of Nrf2 between triptolide treated-group and triptolide + calycosin treated-group showed no significant difference following MG132 intervention (Fig. 5h), indicative of the involvement of ubiquitination in different expression of Nrf2 among groups. Accordingly, calycosin activated Nrf2 by disrupting the direct interaction of Nrf2 and Keap1, resulting in ubiquitination and degradation inhibition.

Fig. 5.

Nrf2 was activated by calycosin through disturbing Nrf2-Keap1 interaction, followed by inhibiting the ubiquitination and degradation. (a), (b) The expression of Keap1 in both H9C2 cardiomyocytes and heart tissues were measured by western blot. (c) The direct interaction of Nrf2 and Keap1 was determined by CoIP assay. (d) Dual immunofluorescence staining of Nrf2 and Keap1 was conducted by ImageXpress Micro 4, the Nrf2-Keap1 colocalization analysis was measured by Image J. (e), (f) Ubiquitination of Nrf2 was determined by immunoprecipitation (IP) assay. (g) The degradation of Nrf2 and Keap1 after CHX exposure were determined by western blot. (h) The expression of Nrf2 before and after MG132 exposure was determined by western blot. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

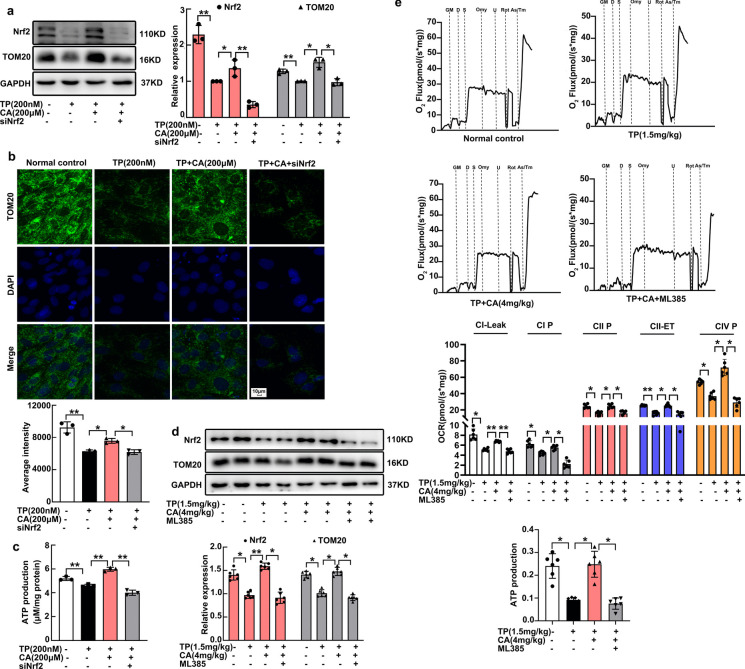

Nrf2 was another regulator for Calycosin promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration

To examine the involvement of Nrf2 in the protection of calycosin in mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration, we used siNfe2l2 in vitro and ML385 in vivo. The enhancement of calycosin in mitochondrial mass of H9C2 cardiomyocytes were significantly blocked by siNfe2l2, as reflected by western blot and immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 6a, b). Consistently, calycosin-mediated increase in ATP production was also mitigated by siNfe2l2 (Fig. 6c). In heart tissues, the mitochondrial content that has been augmented by calycosin was also significantly reduced by ML385 (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Calycosin promoted mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration by activating Nrf2. (a), (b) Mitochondrial mass (TOM20 expression) in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf2 knockdown was determined by western blot and immunofluorescent staining, fluorescence intensity was calculated by the software in ImageXpress Micro 4. (c) ATP production in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf2 knockdown was determined by chemiluminescence. (d) Mitochondrial mass in heart tissues after Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 exposure was determined by western blot. (e) Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacity and electron transfer system (ETS) activity in heart tissues after Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 exposure, was measured by using Oxygraph-2 k respirometer. Mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity was indicated by CI Leak, CI P, CII P and CIV P, ETS activity of complex II was termed as CII ETS. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin; CI Leak, Complex I leak; CI P, Complex I OXPHOS; CII P, Complex II OXPHOS; CIV P, Complex IV OXPHOS; CII ET, Complex II electron transfer system

In line with the alteration in mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial respiratory was also altered. We examined the mitochondrial respiration in heart tissues using the Oxygraph-2 k respirometer, during which mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacity and electron transfer system (ETS) activity, including CI leak, CI-, CII-, CIV-OXPHOS, and CII-ETS were detected. The glutamate (G)/malate (M)/ADP (D)-stimulated complex I related respiration, succinate (S)-supported complex II related respiration, and ascorbate (As)/tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (Tm)-stimulated complex IV related respiration were significantly decreased by triptolide (Fig. 6e), together with the inhibition in ETS activity of complex II. These decreases eventually resulted in a significant reduction in ATP production. On the contrary, calycosin almost restored both OXPHOS capacity of complex I, complex II and complex IV, and complex II ETS activity, which lead to ATP output restoration (Fig. 6e). These results were in consistent with our previous results that calycosin attenuated triptolide-induced mitochondrial respiratory chain complex subunits downregulation in heart tissues (Qi et al. 2023). When ML385 was applied, the protection of calycosin in mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity and ETS activity, as well as ATP production were all blocked (Fig. 6e). In conclusion, Nrf2 was another regulator for calycosin promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration.

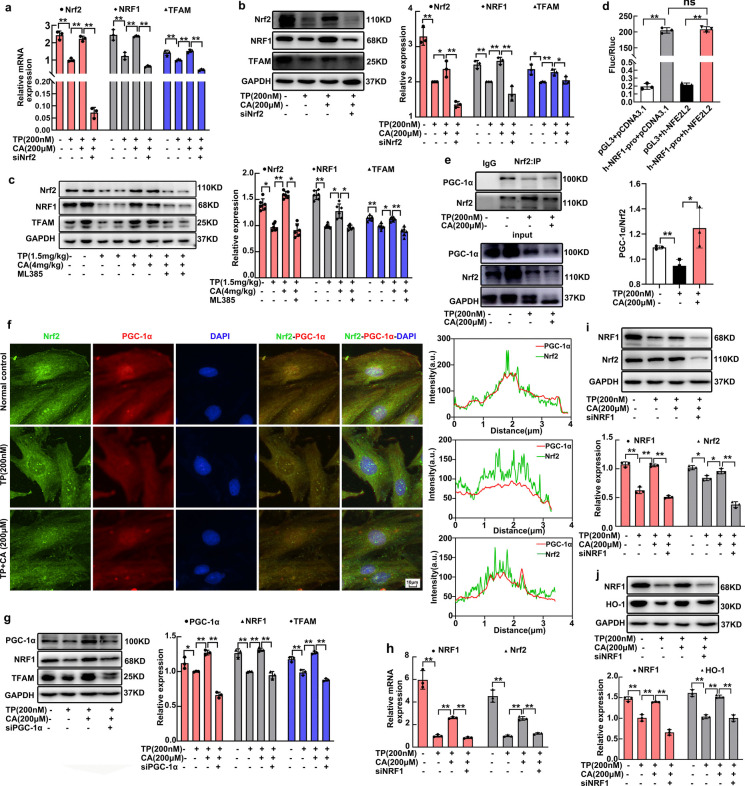

Nrf2/NRF1 signaling crosstalk was activated by calycosin

Since NRF1 was reported to be regulated by Nrf2, we investigated the critical role of Nrf2 in calycosin-triggered NRF1 upregulation. Nrf2 inhibitor and siNfe2l2 were respectively used in vivo and in vitro for verso validation. Nrf2 was successfully knockdown by siNfe2l2 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes at mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7a, b). Nrf2 knockdown induced NRF1 reduction at normal condition (Supplementary Fig. 3a), meanwhile calycosin-mediated NRF1 upregulation was also significantly blocked by siNfe2l2 (Fig. 7a, b). Following NRF1 inhibition, TFAM upregulation was also inhibited by siNfe2l2 (Fig. 7a, b). In vivo, the elevated expression of NRF1 and TFAM in calycosin-treated heart tissues were decreased by Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 (Fig. 7c). These data demonstrated that Nrf2 is indispensable for NRF1 upregulation. Moreover, we performed dual-luciferase reporter assays in 293 T cells to examine whether Nrf2 directly bound to the promoter of Nrf1. Nrf1 promoter from 2kbps upstream of the TSS to 111bps downstream of TSS for Nrf2-binding sites was harvested. However, report activity of Nrf1 was not significantly amplified by Nrf2 overexpression (Fig. 7d), suggesting that Nrf2 promoted NRF1 expression in a manner not directly binding to the promoter.

Fig. 7.

Nrf2/NRF1 signaling crosstalk was activated by calycosin. (a) Nrf2 knockdown was confirmed by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression of Nrf1 and Tfam in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf2 knockdown was measured by qRT-PCR. (b) The expression of NRF1 and TFAM in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after Nrf2 knockdown was measured by western blot. (c) Nrf2 expression in heart tissues after ML385 intervention were detected by western blot. The expression of NRF1 and TFAM in heart tissues after Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 exposure were also measured by western blot. (d) The involvement of Nrf2 in the luciferase report activity of Nrf1 was measured by dual-luciferase reporter assay. (e) The interaction of Nrf2 and PGC-1α after calycosin exposure was determined by CoIP assay. (f) Dual immunofluorescence staining of Nrf2 and PGC-1α was conducted by ImageXpress Micro 4, the Nrf2-PGC-1α colocalization analysis was measured by Image J. (g) The expression of NRF1, and TFAM in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after PGC-1α knockdown was measured by western blot. (h) NRF1 knockdown was confirmed by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression of Nrf2 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after NRF1 knockdown was measured by qRT-PCR. (i) The expression of Nrf2 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after NRF1 knockdown was measured by western blot. (j) The expression of HO-1 in H9C2 cardiomyocytes after NRF1 knockdown was measured by western blot. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6 for in vivo study and n = 3 for in vitro study, (ns: P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). TP, triptolide; CA, calycosin

Transcriptional activity of Nrf2 was usually activated by PGC-1α, the coactivator for both Nrf2 and NRF1. PGC-1α was reported to be interacted with Nrf2 for NRF1 transcription accompanied by mitochondrial biogenesis promotion previously (Li et al. 2021). Therefore, Nrf2-PGC-1α interaction was investigated in this present study by CoIP assay and dual immunofluorescence staining. These results demonstrated that Nrf2-PGC-1α interaction was weakened by triptolide and enhanced by calycosin (Fig. 7e, f). This alteration mainly occured in nucleus as illustrated in immunofluorescence (Fig. 7f). PGC-1α has been convincedly demonstrated to be critical in calycosin-mediated mitochondrial protection in our previous research (Qi et al. 2023). Whether PGC-1α was essential for NRF1 expression. PGC-1α was knockdown by siPpargc1α in H9C2 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7g) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Then the promotion of calycosin in NRF1 expression was significantly mitigated, followed by TFAM expression inhibition (Fig. 7g). These data indicated that Nrf2/PGC-1α signaling was important in calycosin-induced NRF1 expression and mitochondrial biogenesis.

Whether the expression of Nrf2 was regulated by NRF1? We further investigated the influence of NRF1 knockdown on Nrf2 expression. Consistently, NRF1 knockdown induced Nrf2 inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 3b), and the upregulation of Nrf2 by calycosin was also abrogated by NRF1 knockdown (Fig. 7h, i), indicative of the involvement of NRF1 in Nrf2 expression. In addition, the expression of HO-1, the downstream molecule of Nrf2, was also blocked by NRF1 knockdown (Fig. 7j). These data indicated the mutual regulation between NRF1 and Nrf2 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic of Nrf2/NRF1 signaling activation by calycosin amplified mitochondrial biogenesis in triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity. Calycosin disrupted Nrf2-Keap1 interaction, followed by inhibiting Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation. Nrf2 was translocated to nucleus where it interacted with PGC-1α for initiating NRF1 transcription, which further promoted mitochondrial biogenesis. NRF1 upregulation reactivated Nrf2, which established a positive feedback loop, leading to mitochondrial biogenesis amplification

Discussion

In this work, mitochondrial protective effect of calycosin and the underlying mechanism were studied in vivo and in vitro. Results indicated that mitochondrial content together with its ultrastructure were improved by calycosin, which ultimately resulted in enhancement of cardiac contractile capacity. Mechanically, coactivation of NRF1 and Nrf2 signaling was suggested to be involved in amplifying mitochondrial biogenesis using calycosin. Therefore, we proposed that calycosin might be a promising agent for treating cardiotoxicity by the mitochondrion target.

Calycosin, the isoflavonoid compound isolated from Astragali radix (Li et al. 2022), was the well-known heart protective agent that it significantly improved myocardial infarction (Chen et al. 2022), heart failure (Wang et al. 2022) and attenuated chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity (Zhai et al. 2020). Doxorubicin (DOX), the representative chemotherapeutic agent with cardiotoxicity side effect, was rescued by calycosin via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Zhai et al. 2020) and antioxidative stress. Triptolide was a potential antitumor candidate and the cardiotoxicity was also reversed by calycosin. Calycosin was a safe agent that the therapeutic concentration of calycosin reached 200 μM in H9C2 cardiomyocytes for DOX cardiotoxicity treatment. This concentration was also effective in treating triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity. The oral bioavailability of calycosin was not satisfied that it suffered from poor solubility. Intraperitoneal injection was applied in triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity treatment and 4 mg/kg exerts sufficient effects.

Mitochondria have been recognized as primary organelle for sustaining myocardial tissue homeostasis in that it plays a pivotal role in the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Zhou and Tian 2018). Heart is the organ with active metabolism that requires large amount of energy for contraction and relaxation of cardiomyocytes. Therefore, mitochondrial dysfunction usually induces a direct detrimental effect on the contractile capacity of cardiomyocytes. In this present study, triptolide-induced cardiac contraction dysfunction as reflected by the reduction in fractional shortening and ejection fraction in vivo and F:actin depolymerization in vitro, is due to the decrease in mitochondrial mass and impairment in mitochondrial structure, eventually resulting in cardiomyocytes apoptosis. An increasing number of antitumor agents in solid and hematological tumors treatment have been demonstrated to induce cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction (Varga et al. 2015), among which anthracyclines (ANTs), primarily DOX has attracted considerable attention worldwide (Rocca et al. 2022; Damiani et al. 2016; Kim and Choi 2021; Sangweni et al. 2022). Mitochondrial-targeted therapy, particularly mitochondrial quality control homeostasis is expected to become a promising therapeutic approach for DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (Wu et al. 2022b, 2023). Calycosin with mitochondrial protection potential (Huang et al. 2021) has been proved to attenuate DOX-induced cardiotoxicity previously (Lu et al. 2021; Zhai et al. 2020), and was confirmed to ameliorate triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity in the present study.

The sufficient mitochondrial mass, together with precise mitochondrial quality control is indispensable for enormous ATP output for supporting the continuous pumping function of cardiomyocytes (Picca et al. 2018). Mitochondrial biogenesis controls the mitochondrial content and is implicated in mitochondrial quality control. NRF1 is the most well-known mitochondrial biogenesis-related transcription factor that mainly locates in nucleus responsible for transcriptional regulation of gene involved in multiple mitochondrial function. Calycosin has been confirmed to increase the expression of respiratory complexes subunits in our previous investigation, and was demonstrated to increase the expression of TFAM and TOM20 in this present study, both of which are attributed to its promotion on NRF1 upregulation. NRF1 overexpression showed the similar protection to calycosin on mitochondria, and NRF1 knockdown blocked the enhancement of calycosin on TFAM and TOM20 expression. Above results all indicated that calycosin-triggered mitochondrial protection is dependent on NRF1.

Nrf2 was another regulator for mitochondrial biogenesis (Huang et al. 2023). In this present study, Nrf2 was also upregulated by calycosin especially nuclear Nrf2, followed by NQO1 and HO-1 upregulation, the target genes of Nrf2, which indicated the activated effect of calycosin on Nrf2. The activity of Nrf2 is precisely controlled by Keap1 through direct interaction. Antioxidant are usually prone to downregulate Keap1 for Nrf2 stabilization (Li et al. 2021) in cytoplasm. However, Nrf2 activation by calycosin was not due to Keap1 downregulation. On the contrary, calycosin upregulated Keap1 instead of decreasing its expression. Hence, we focused on the direct combination of Keap1 and Nrf2. Keap1-Nrf2 interaction was dramatically disturbed by calycosin, resulting in the decrease of Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation, which eventually led to Nrf2 accumulation in nucleus for transcriptional activity activation. Accordingly, calycosin-mediated Nrf2 activation was attributed to its disturbance in Keap1-Nrf2 interaction.

How did these two transcription factors of Nrf2 and NRF1 interact for positive regulation in mitochondrial biogenesis? Previous study demonstrated that Nrf2 initiated the transcription of Nrf1 by occupying the ARE sequences of Nrf1 gene (Piantadosi et al. 2008). However, the regulation of Nrf2 protein to Nrf1 gene might be more sophisticated than that. Luciferase report assay in this present study achieved an opposite result that luciferase report activity of Nrf1 was not significantly amplified by Nrf2 overexpression, which reflected no direct combination between Nrf1 promoter and Nrf2 protein. Whether the regulatory mode of Nrf2 to Nrf1 genes is in coincident with IL1b and IL1a genes regulation that Nrf2 binds to the proximity of IL1b and IL1a genes affecting RNA pol II recruitment (Kobayashi et al. 2016), needs further verification. The transcriptional regulation of Nrf2 in NRF1 was reported to be activated by PGC-1α via direct interaction previously (Li et al. 2021). Therefore, we investigated Nrf2-PGC-1α interaction by both CoIP and dual immunofluorescence staining. Nrf2-PGC-1α interaction was weakened by triptolide and enhanced by calycosin and consistently the expression of Nrf2 and PGC-1α was decreased by triptolide and increased by calycosin, both of which explained the distinct regulation in NRF1 expression. Further, the verso validation was introduced by knockdown of Nrf2 and PGC-1α with siRNA. Then calycosin-triggered NRF1 upregulation was almost blocked, indicative of the importance of Nrf2/ PGC-1α signaling in NRF1 expression. The upregulated NRF1 ultimately promoted mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration. To further verify the impact of Nrf2 in calycosin-mediated mitochondrial protection, Nrf2 knockdown and Nrf2 inhibitor were respectively used in vitro and in vivo. Both mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration that promoted by calycosin was abrogated by Nrf2 inhibition. Intriguingly, the crosstalk between Nrf2 and NRF1 might exist that NRF1 knockdown simultaneously led to Nrf2 inhibition. Calycosin-mediated enhancement in Nrf2 and its target gene HO-1 expression was also blocked by NRF1 knockdown. Given to that, the bidirectional activation of Nrf2 and NRF1 by calycosin might establish a positive feedback loop, eventually leading to mitochondrial biogenesis amplification.

Nrf2 was a key regulator for multiple cytoprotective pathways, including anti-inflammation, antioxidation and mitochondrial protection. Calycosin-mediated Nrf2 activation may result in a comprehensive protection in triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity more than that mitochondrial biogenesis enhancement alone. Inflammation and oxidative stress are usually related to mitochondrial dysfunction. Therefore, understanding the interactions among these processes is beneficial to clarify and comprehensively understand the role of calycosin, and promote its further development and utilization in clinic.

Conclusions

In summary, our study illustrated that calycosin bidirectionally activated transcription factor Nrf2 and NRF1, positively triggering Nrf2/NRF1 signaling crosstalk, resulting in mitochondrial biogenesis amplification, which facilitated it to become a promising candidate for mitochondria-related disease treatment and improving mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiotoxicity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the related fund for providing financial supports for this experiment. And we appreciate the contributions of all the members participating in this study.

Author contributions

Xiao-Ming Qi and Qing-Shan Li contributed to the conception and design of the study. Xiao-Ming Qi, Wei-Zheng Zhang and Yu-Qin Zuo performed the experiment and analyzed the data. Yuan-Biao Qiao, Yuan-Lin Zhang and Jin-Hong Ren reviewed the manuscript. Xiao-Ming Qi and Qing-Shan Li wrote the manuscript. Qing-Shan Li funded and supervised the research.

Funding

The work is funded by the Key Research and Development Plan (Key Project) of Shanxi Province (Grant number 202102130501005), Basic Research Program of Shanxi province (Grant number 202203021212349), Scientific and technological innovation project of Shanxi provincial department of education (Grant number 2022L331).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of animal ethics and protocols of Shanxi university of Chinese medicine (AWE202403129).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bonora M, Wieckowski MR, Sinclair DA, Kroemer G, Pinton P, Galluzzi L. Targeting mitochondria for cardiovascular disorders: therapeutic potential and obstacles. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(1):33–55. 10.1038/s41569-018-0074-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Xu H, Xu T, Ding W, Zhang G, Hua Y, Wu Y, Han X, Xie L, Liu B, Zhou Y. Calycosin reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac function in post-myocardial infarction mice by suppressing TGFBR1 signaling pathways. Phytomedicine. 2022;104:154277. 10.1016/j.phymed.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani RM, Moura DJ, Viau CM, Caceres RA, Henriques JA, Saffi J. Pathways of cardiac toxicity: comparison between chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and mitoxantrone. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(9):2063–76. 10.1007/s00204-016-1759-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Chen H, Long J, Song J, Xie L, Li X. Calycosin: a review of its pharmacological effects and application prospects. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19(7):911–25. 10.1080/14787210.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):179–88. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteras N, Abramov AY. Nrf2 as a regulator of mitochondrial function: Energy metabolism and beyond. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;189:136–53. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi G, Jasoliya M, Sahdeo S, Saccà F, Pane C, Filla A, Marsili A, Puorro G, Lanzillo R, Morra VB, Cortopassi G. Dimethyl fumarate mediates Nrf2-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(15):2864–73. 10.1093/hmg/ddx167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(4):199–218. 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Xue LF, Hu B, Liu HH. Calycosin-loaded nanoliposomes as potential nanoplatforms for treatment of diabetic nephropathy through regulation of mitochondrial respiratory function. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):178. 10.1186/s12951-021-00917-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Wu Z, Zhang J, Wang K, Zhao Q, Chen M, Yan S, Guo Q, Ma Y, Ji L. Andrographolide attenuated MCT-induced HSOS via regulating NRF2-initiated mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant response. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39(6):3269–85. 10.1007/s10565-023-09832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo L, Scarpulla RC. Mitochondrial DNA instability and peri-implantation lethality associated with targeted disruption of nuclear respiratory factor 1 in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(2):644–54. 10.1128/MCB.21.2.644-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DP, Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev. 2004;18(4):357–68. 10.1101/gad.1177604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CW, Choi KC. 2021 Effects of anticancer drugs on the cardiac mitochondrial toxicity and their underlying mechanisms for novel cardiac protective strategies. Life Sci. 2021;277:119607. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, Tanaka N, Moriguchi T, Motohashi H, Nakayama K, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11624. 10.1038/ncomms11624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Feng YF, Liu XT, Li YC, Zhu HM, Sun MR, Li P, Liu B, Yang H. Songorine promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2 induction during sepsis. Redox Biol. 2021;2021(38):101771. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Han B, Zhao H, Xu C, Xu D, Sieniawska E, Lin X, Kai G. Biological active ingredients of Astragali Radix and its mechanisms in treating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Phytomedicine. 2022;98:153918. 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Lu L, Gao L, Wang Y, Wang W. Calycosin attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via autophagy regulation in zebrafish models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137:111375. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CY, Day CH, Kuo CH, Wang TF, Ho TJ, Lai PF, Chen RJ, Yao CH, Viswanadha VP, Kuo WW, Huang CY. Calycosin alleviates H2O2-induced astrocyte injury by restricting oxidative stress through the Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Environ Toxicol. 2022;37(4):858–67. 10.1002/tox.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry TL, Ristow M. Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NFE2L2, Nrf2) mediates exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis and the anti-oxidant response in mice. J Physiol. 2016;594(18):5195–207. 10.1113/JP271957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel P, Hoff DD, Saluja AK, Velagapudi M, Borazanci E, Han H. Triptolide and its derivatives as cancer therapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(5):327–341. 10.1016/j.tips.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Mitochondrial transcription factor A induction by redox activation of nuclear respiratory factor 1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(1):324–33. 10.1074/jbc.M508805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS, Babiker A, Suliman HB. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ Res. 2008;103(11):1232–40. 10.1161/01.RES.0000338597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picca A, Mankowski RT, Burman JL, Donisi L, Kim JS, Marzetti E, Leeuwenburgh C. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms as molecular targets in cardiac ageing. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(9):543–54. 10.1038/s41569-018-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov LD. Mitochondrial biogenesis: An update. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(9):4892–9. 10.1111/jcmm.15194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi XM, Qiao YB, Zhang YL, Wang AC, Ren JH, Wei HZ, Li QS. PGC-1α/NRF1-dependent cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis: A druggable pathway of calycosin against triptolide cardiotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023;2023(171):113513. 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca C, Francesco EM, Pasqua T, Granieri MC, Bartolo AD, Cantafio ME, Muoio MG, Gentile M, Neri A, Angelone T, Viglietto G, Amodio N. Mitochondrial determinants of anti-cancer drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Biomedicines. 2022;10(3):520. 10.3390/biomedicines10030520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangweni NF, Gabuza K, Huisamen B, Mabasa L, Vuuren D, Johnson R. Molecular insights into the pathophysiology of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: a graphical representation. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96(6):1541–50. 10.1007/s00204-022-03262-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla RC, Vega RB, Kelly DP. Transcriptional integration of mitochondrial biogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(9):459–66. 10.1016/j.tem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulasov AV, Rosenkranz AA, Georgiev GP, Sobolev AS. Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling: Towards specific regulation. Life Sci. 2022;2022(291):120111. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga ZV, Ferdinandy P, Liaudet L, Pacher P. Drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiotoxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309(9):H1453-1467. 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Li W, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Cao J, Tan NN, Yang S, Lu L, Zhang Q, Wei P, Ma X, Wang W, Wang Y. Calycosin as a Novel PI3K Activator Reduces Inflammation and Fibrosis in Heart Failure Through AKT-IKK/STAT3 Axis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:828061. 10.3389/fphar.2022.828061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Zhang Z, Zhang W, Liu X. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial therapies in heart failure. Pharmacol Res. 2022a;2022(175):106038. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BB, Leung KT, Poon EN. Mitochondrial-targeted therapy for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022b;23(3):1912. 10.3390/ijms23031912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Wang L, Du Y, Zhang Y, Ren J. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms as therapeutic targets in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44(1):34–49. 10.1016/j.tips.2022.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi C, Peng S, Wu Z, Zhou Q, Zhou J. Toxicity of triptolide and the molecular mechanisms involved. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;2017(90):531–41. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y, Wang W, Wang L, Pan J, Cheng Y, Shen F, Huang Z. Triptolide induces p53-dependent cardiotoxicity through mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2018;2018(355):269–85. 10.1016/j.taap.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J, Tao L, Zhang S, Gao H, Zhang Y, Sun J, Song Y, Qu X. Calycosin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation via the sirtuin 1-NOD-like receptor protein 3 pathway. Phytother Res. 2020;34(3):649–59. 10.1002/ptr.6557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YJ, Wu KC, Klaassen CD. Genetic activation of Nrf2 protects against fasting-induced oxidative stress in livers of mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59122. 10.1371/journal.pone. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Tian R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(9):3716–26. 10.1172/JCI120849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Xi C, Wang W, Fu X, Liang J, Qiu Y, Jin J, Xu J, Huang Z. Triptolide-induced oxidative stress involved with Nrf2 contribute to cardiomyocyte apoptosis through mitochondrial dependent pathways. Toxicol Lett. 2014; 230(3):454–66. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Not applicable.