Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction and α-synuclein (αSyn) aggregation are key contributors to Parkinson’s Disease (PD). While genetic and environmental risk factors, including mutations in mitochondrial-associated genes, are implicated in PD, the precise mechanisms linking mitochondrial defects to αSyn pathology remain incompletely understood, hindering the development of effective therapeutic interventions. Here, we identify the loss of branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDK) as a mitochondrial risk factor that exacerbates αSyn pathology by disrupting Complex I function. Our findings reveal a consistent downregulation of BCKDK in dopaminergic (DA) neurons from A53T-αSyn mouse models, PD patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, and postmortem brain tissues. BCKDK deficiency leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced membrane potential and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production upon administration of a stressor, which in turn promotes αSyn oligomerization. Mechanistically, BCKDK interacts with the NDUFS1 subunit of Complex I to stabilize its function. Loss of BCKDK disrupts this interaction, leading to Complex I destabilization and enhanced αSyn aggregation. Notably, restoring BCKDK expression in neuron-like cells rescues mitochondrial integrity and restores Complex I activity. Similarly, in patient-derived iPS cells differentiated to form dopaminergic neurons, NDUFS1 and phosphorylated aSyn levels are partially restored upon BCKDK expression. These findings establish a mechanistic link between BCKDK deficiency, mitochondrial dysfunction, and αSyn pathology in PD, positioning BCKDK as a potential therapeutic target to mitigate mitochondrial impairment and neurodegeneration in PD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40478-024-01915-8.

Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a multifactorial disease primarily marked by the progressive loss of motor function, which results from the degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) and the accumulation of α-synuclein (αSyn) inclusions, known as Lewy bodies [1, 2]. As the second most common neurodegenerative disease, PD is associated with an increasing prevalence and is clinically characterized by motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, and bradykinesia [3–5]. While the exact etiology of PD remains unclear, mitochondrial dysfunction is recognized as a key contributor to its pathogenesis, occurring early in the disease progression [6–8]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in PD manifests through several mechanisms, including impaired fission and fusion dynamics, damage to the electron transport chain (ETC), and elevated oxidative stress. These factors collectively drive the degeneration of neurons, particularly DA neurons, which are highly susceptible due to their elevated energy demands [9–13]. A notable aspect of PD pathology is the interaction between mitochondria and αSyn. Studies have shown that αSyn enters mitochondria, where it binds directly with mitochondrial proteins, exacerbates oxidative stress, disrupts ETC function, promotes mitochondrial fragmentation, and induces mitochondrial DNA damage. The combination of mitochondrial dysfunction and αSyn toxicity creates a detrimental cycle, accelerating DA neuronal loss [11, 14–19].

Certain familial forms of PD are caused by mutations in mitochondria-related genes; however, these only account for about 10% of PD cases. For most patients, the disease lacks clear genetic causes. In this context, genome wide association studies (GWAS) have provided valuable insights into the genetic underpinnings of PD by identifying common, lower-risk genetic variants that contribute to disease development. Among the mitochondrial-related genes highlighted in PD GWAS [20–23], branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDK) stands out. BCKDK is a key regulator of the branched chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolic pathway, which involves the conversion of BCAAs—valine, leucine, and isoleucine—into branched chain ketoacids (BCKAs). These BCKAs are further catabolized in the mitochondrial matrix by the branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKD) complex that catalyzes the irreversible decarboxylation of BCKAs into their corresponding branched chain acyl-CoA esters [24]. BCKD activity is regulated by BCKDK: BCKDK phosphorylates and inactivates the E1a subunit of BCKD, thus serving as a negative regulator of BCAA metabolism [25].

Emerging evidence suggests that BCKDK deficiency affects mitochondrial bioenergetics as well as fission and fusion dynamics, and BCAAs have been shown to play a part in preventing oxidative damage [26–28]. Notably, disruption of the BCAA metabolic pathway induces parkinsonism and dopaminergic neuron death in C. elegans [29]. In mice, BCKDK knockout results in significantly reduced BCAA levels, neurological abnormalities, and inhibited protein synthesis [27]. BCKDK deficiency in patients is linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, specifically a form of autism accompanied by intellectual disability, motor impairments, and epilepsy [30]. Primary fibroblasts from patients with BCKDK deficiency exhibit altered mitochondrial function, including increased oxidative stress, bioenergetics depletion, and hyperfusion [26]. Allelic expression profiling of the PD-associated BCKDK rs14235 locus in human brain samples identifies it as an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL), suggesting an association between altered BCKDK expression and PD [31]. The BCKDK rs14235 A allele correlates with prominent alterations to the structural and functional neuronal networks in PD patients, including increased assortativity and lower small-worldness factors, though, unexpectedly, these correspond to reduced rigidity scores and milder motor symptoms. The mechanisms by which BCKDK allelic expression affects network topology and efficiency are unknown, but it emerges as a promising potential risk factor in PD [32].

Despite these observations, the role of BCKDK in neurodegenerative disorders, like PD, has not been fully examined. Here, we report that BCKDK protein levels are reduced in various in vitro and in vivo models of PD. In DA neuronal cells, BCKDK knockdown worsens cell viability, mitochondrial dysfunction, and αSyn pathology. Furthermore, we demonstrate that BCKDK binds directly to Complex I via the NDUFS1 subunit, and that this interaction is compromised in cell models expressing mutant αSyn. The loss of this interaction reduces Complex I levels and activity, while compensatory restoration of BCKDK in these PD cell models rescues Complex I and overall mitochondrial function and ameliorates αSyn pathology. These findings highlight a novel role for BCKDK in modulating mitochondrial health and αSyn toxicity in PD, positioning it as a potential therapeutic target.

Results

BCKDK protein levels are reduced in mouse, patient, and cell models of PD

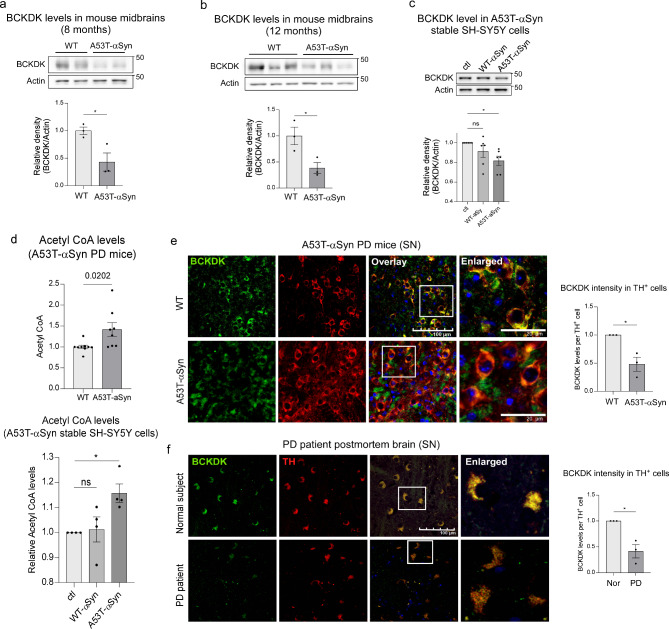

To investigate the alterations in BCKDK expression in PD, we began by examining BCKDK protein levels in A53T-αSyn overexpressing mice, a well-established model for studying αSyn-mediated neuropathology [33]. Midbrain lysates from 8- and 12-month-old A53T-αSyn overexpressing mice, representing presymptomatic and symptomatic stages of PD-associated motor dysfunction, were analyzed. Western blot analysis revealed a sustained and significant reduction in BCKDK protein levels in the midbrain of A53T-αSyn mice at both presymptomatic (57% reduction; p = 0.025) and symptomatic (62% reduction; p = 0.036) stages compared to age-matched wildtype (WT) mice (Fig. 1a, b). Additionally, in neuron-like SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either WT-αSyn-myc or A53T-αSyn-myc [34], a decrease in BCKDK protein levels (18% decrease; p = 0.018) was observed in mutant αSyn expressing neurons (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

BCKDK is decreased in DA neurons in patients and αSyn mouse models of PD. (a) Total lysates from the midbrains of 8-month wild type (WT) or A53T-αSyn expressing mice were assessed via Western blot (WB) using anti-BCKDK and anti-β-Actin (labeled Actin) antibodies. The density of BCKDK versus actin is quantitated and shown in histogram. n = 3 mice/group. (b) Total lysates from the midbrains of 12-month WT and A53T-αSyn mice were subjected to WB analysis; quantifications indicate ratio of the density of BCKDK signal to that of β-Actin and are shown in histogram. n = 3 mice/group. (c) DA neuronal SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either myc, WT- αSyn-myc, or A53T-αSyn-myc were lysed and assessed using WB with the anti-BCKDK and anti-β-Actin antibodies. Data was quantified using blot intensities (normalized to β-Actin) from 6 independent experiments. (d) Acetyl CoA levels were assessed in mouse brain midbrains and cell samples using an Acetyl CoA ELISA kit. (e) Brain sections of 12-month WT and A53T-αSyn mice were stained with anti-BCKDK and anti-TH antibodies. n = 3 mice/group; scale bar: 100 μm. Average immunodensity of BCKDK in TH-expressing cells is plotted for each sample. (f) Brain sections from postmortem brain samples obtained from normal subjects and PD patients were stained using anti-BCKDK and anti-TH antibodies. BCKDK immunodensity per TH+ cell was quantified. n = 3 patients/group; scale bar: 100 μm. All data shown are mean ± SEM; all data were analyzed using either the Student’s t test or One-way ANOVA

BCKDK is a negative regulator of the branched chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolic pathway, which breaks down valine, leucine, and isoleucine into a variety of metabolites, including Acetyl CoA [24]. We therefore assessed Acetyl CoA levels via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as a measure of BCAA metabolic activity. In A53T-αSyn-expressing mice, Acetyl CoA levels at presymptomatic stage were significantly elevated (42% increase; p = 0.020) in the midbrain, consistent with the reduced BCKDK activity (Fig. 1d, upper panel). Similarly, SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing A53T-αSyn displayed an increase in Acetyl CoA levels (16% increase; p = 0.030) (Fig. 1d, lower panel) as well as an increase in BCAT-1 and BCKD, key enzymes of the BCAA metabolic pathway (Suppl. Figure 1a), further supporting the notion of impaired BCKDK function in this PD cell culture model.

Lastly, we assessed the immunodensity of BCKDK in PD mice and PD patient brains. Immunofluorescence staining using anti-BCKDK and anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, a DA neuronal marker) antibodies in 12-month-old A53T-αSyn mice revealed a significant reduction in BCKDK immunodensity (52% decrease; p = 0.014) specifically within TH+ DA neurons of the SN (Fig. 1e). In contrast, BCKDK intensity in non-DA neurons and non-neuronal cells was comparable between WT and A53T-αSyn expressing mice (Suppl. Figure 1b-d). Consistently, immunofluorescence staining on postmortem SN tissue from PD patients also revealed a pronounced reduction in BCKDK intensity (59% decrease; p = 0.011) in TH+ neurons compared to healthy subjects (Fig. 1f, Suppl. Figure 1e). These findings underscore the widespread and consistent loss of BCKDK in DA neurons, both in experimental models and in human PD pathology.

BCKDK deficiency results in mitochondrial defects and worsened αSyn pathology

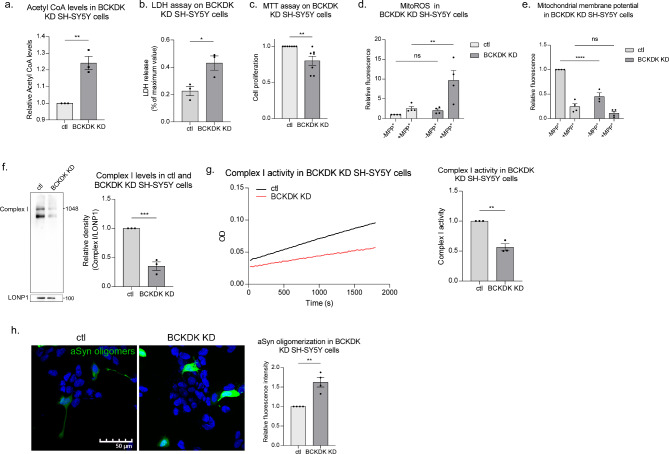

To mimic the BCKDK deficiency observed in PD models, we generated a stable BCKDK knockdown DA neuronal cell line, achieving an 87% knockdown efficiency in BCKDK expression in SH-SY5Y cells (Suppl. Figure 2a). These BCKDK-deficient cells displayed elevated Acetyl CoA levels (24% increase; p = 0.004), suggesting enhanced BCAA metabolism due to the loss of BCKDK (Fig. 2a). BCKDK knockdown cells exhibited greater release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (210% increase; p = 0.031) compared to control cells, suggesting reduced cell viability upon BCKDK downregulation (Fig. 2b). Cellular metabolic activity was assessed using the MTT assay, which measures the reduction of the tetrazolium dye MTT by NAD(P)H-dependent cellular oxidoreductase enzymes. BCKDK deficient cells exhibited a moderate but statistically significant reduction in metabolic activity (20% decrease; p = 0.008) compared to controls (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, mitochondrial oxidative stress, measured using the MitoSOX superoxide indicator dye, was not significantly changed under basal conditions in BCKDK deficient cells. However, upon treatment with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a Complex I inhibitor widely used to model PD, BCKDK deficient cells exhibited a dramatic increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (376% increase; p = 0.010) (Fig. 2d), suggesting a vulnerability to mitochondrial stress. One possibility is that under normal conditions ROS clearance pathways compensate for BCKDK loss-induced oxidative stress, but mitochondria are left more susceptible to additional stressors. Additionally, we determined the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) via tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM) staining and found a marked loss (55% decrease; p < 0.0001) of the MMP in our BCKDK knockdown cells. Interestingly, the addition of MPP+ did not further exacerbate the loss of MMP in BCKDK-deficient cells (Fig. 2e). Thus, BCKDK depletion alone is sufficient to induce mitochondrial depolarization comparable to that caused by MPP+. These results suggest that BCKDK is crucial for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function, and its deficiency exacerbates mitochondrial stress under conditions that mimic PD. Moreover, the pronounced increase in ROS upon MPP+ exposure points to a potential interaction between BCKDK and Complex I dysfunction in PD pathology.

Fig. 2.

BCKDK deficiency induces mitochondrial damage and αSyn oligomerization. (a) BCKDK knockdown stable SH-SY5Y cell lines were harvested and subjected to Acetyl CoA ELISA assay. n = 3 independent experiments. (b) Cell viability was assessed in stable BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells using LDH assay. n = 3 independent experiments. (c) Cell proliferation was assessed in stable BCKDK knockdown cells using MTT assay. n = 7 independent experiments. (d) Mitochondrial oxidative stress was measured using the MitoSOX fluorescent dye, a superoxide indicator. MPP+ was added where indicated at a concentration of 1mM for 48 h prior to MitoSOX treatment. Cells were imaged and fluorescence intensity was quantified for each group. n = 4 independent experiments. (e) Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using TMRM fluorescent dye, which localizes to mitochondria with intact membrane potentials. MPP+ was added at a concentration of 1mM for 48 h prior to TMRM treatment; fluorescence intensity was quantified. n = 4 independent experiments. (f) Blue Native PAGE was conducted with lysates obtained from mitochondrial fractions of control and BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells. Complex I was detected using an anti-NDUFS6 antibody. Complex I levels were normalized to LonP1 protein levels, which were measured using SDS-PAGE. n = 3 independent experiments. (g) Complex I activity was assessed using a Complex I enzyme activity assay kit. n = 3 independent experiments. (h) Control and BCKDK knockdown cells were transfected with αSyn tagged with N- or C-terminus Venus fluorescent protein fragments for 48 h. Cells were imaged and fluorescence intensity per expressing cell was quantified. n = 4 independent experiments. All data are mean ± SEM with at least three independent repeats. Data were analyzed using either Student’s t test or One-way ANOVA

To further investigate the potential link between BCKDK and Complex I, we performed Blue Native PAGE on BCKDK deficient SH-SY5Y cells and found a significant decrease in Complex I levels upon BCKDK knockdown (Fig. 2f). Curiously, this blot showed two bands when probed for Complex I; we suspect the lower bands represent partially assembled subcomplexes. Blue Native PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining showed that the four other oxidative phosphorylation complexes were not significantly altered upon BCKDK knockdown, indicating that BCKDK acts specifically on Complex I (Suppl. Figure 2b). This decrease in Complex I levels was accompanied by a reduction in NADH-dependent enzyme activity (44% decrease; p = 0.002), as demonstrated by the decreased oxidation of NADH to NAD+ (Fig. 2g). These data support the idea that the loss of BCKDK acts on Complex I, reducing both its abundance and functionality.

These findings implicate BCKDK in the regulation of mitochondrial function, particularly in maintaining Complex I integrity. However, it remained unknown whether BCKDK deficiency directly influenced PD-associated pathologies. Since αSyn aggregation is a hallmark of PD and there is a well-documented reciprocal relationship between αSyn and Complex I dysfunction [11, 12], we sought to determine if BCKDK loss influenced αSyn oligomerization. To address this, we employed bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) to measure αSyn oligomerization in our BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells. Cells were co-transfected with αSyn constructs fused to VN and VC fragments of the Venus fluorescent protein, which emits a fluorescent signal upon αSyn oligomer formation [35]. Our results showed a significant increase in αSyn oligomerization (54% increase; p = 0.011) in BCKDK knockdown cells (Fig. 2h). Consistently, immunofluorescence staining using an anti-aggregated αSyn antibody showed a corresponding increase in αSyn aggregation in BCKDK knockdown cells (Suppl. Figure 2c), indicating that BCKDK deficiency exacerbates αSyn pathology.

BCKDK deficiency induces changes largely in metabolism-related pathways

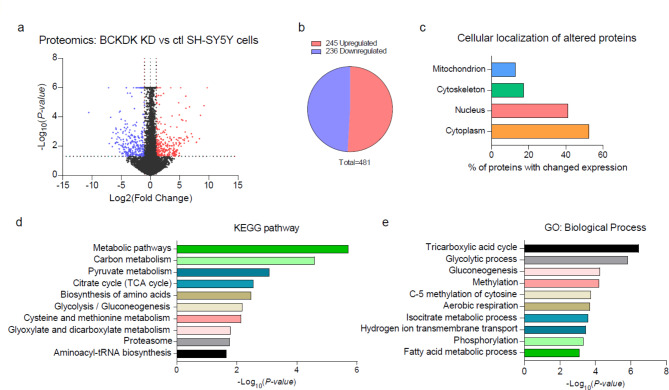

To further elucidate the impact of BCKDK deficiency in DA neurons, we conducted a label free unbiased proteomic analysis on our stable BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cell lines. Of the approximately 27,000 proteins identified, 481 were significantly altered in BCKDK deficient cells (p < 0.05) when compared to controls (Fig. 3a, b). After applying a minimum log2(fold change) threshold of 1, we identified 245 upregulated and 236 downregulated proteins (Fig. 3b, Suppl. Table 1). Functional annotation of these significantly upregulated or downregulated proteins showed that 52% were expressed in the cytoplasm, 41% were expressed in the nucleus, and 13% were expressed in the mitochondria (Fig. 3c). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis identified several metabolic pathways significantly affected by BCKDK knockdown, with prominent alterations in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, along with carbon metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (Fig. 3d). Further gene ontology (GO) analysis of the altered proteins reinforced that the TCA cycle was the pathway most strongly associated with BCKDK deficiency (Fig. 3e). These findings support our earlier findings of mitochondrial defects in BCKDK deficient cells, while also pointing to broader metabolic disruptions, suggesting that BCKDK loss impacts the overall bioenergetic landscape of the cell.

Fig. 3.

Proteomic analysis of BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells. Three independent samples of stable control and BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to proteomic analysis. (a) Volcano plot representing fold change and p value of BCKDK knockdown cells compared to control SH-SY5Y cells. Blue points represent significantly downregulated proteins; red points represent significantly upregulated proteins. Cutoffs were defined as p < 0.05 and at least two-fold changes. (b) Chart representing the ratio of upregulated and downregulated significant proteins. (c) Subcellular localization of altered proteins. (d, e) Pathway analysis of selected proteins. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) databases were used for functional annotation

BCKDK interacts with NDUFS1, a subunit of Complex I

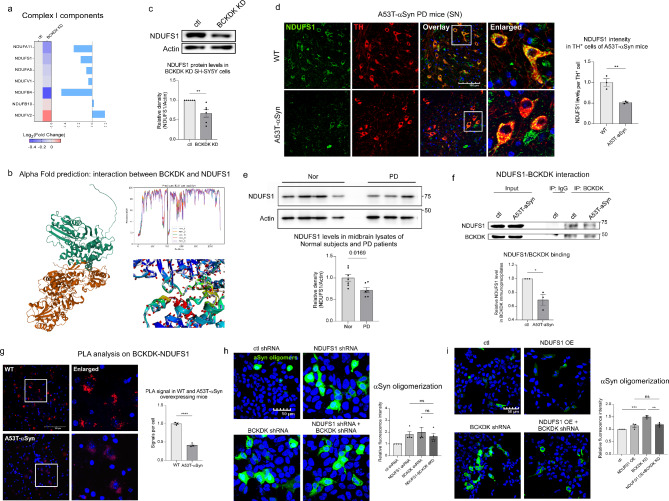

Among the proteins involved in the TCA cycle that were most affected by BCKDK knockdown in SH-SY5Y cells, we identified seven significantly altered subunits of Complex I: NDUFA11, NDUFS1, NDUFA5, NDUFV1, NDUFB4, NDUFB10, NDUFV2 (Fig. 4a). Using AlphaFold2, we predicted potential interactions between BCKDK and these subunits [36], with a promising interaction with the subunit NDUFS1 identified (Fig. 4b, Suppl. Figure 3). Since NDUFS1 is oriented toward the mitochondrial matrix, it presents a likely target for BCKDK binding. Thus, we focused on NDUFS1 in our study. Western blot analysis revealed a 34% reduction in NDUFS1 levels in BCKDK-deficient SH-SY5Y cells (p = 0.005, Fig. 4c). Similarly, immunofluorescence staining in 12-month A53T-αSyn expressing mice demonstrated a significant decrease in NDUFS1 intensity (49% decrease; p = 0.007) specifically in TH+ DA neurons (Fig. 4d, Suppl. Figure 4a), and lysates derived from the midbrains of postmortem healthy individuals and PD patients analyzed via Western blot also showed a decrease in NDUFS1 levels in PD patients (28% decrease; p = 0.017) (Fig. 4e, Suppl. Figure 4b).

Fig. 4.

BCKDK interacts with NDUFS1, a subunit of Complex I. (a) Proteomic analysis identifies seven Complex I subunits altered in BCKDK knockdown cells. (b) AlphaFold2 structural prediction of a potential binding site between BCKDK (green) and NDUFS1 (orange). Predicted IDDT per position and close-up of the predicted interaction site are shown. (c) Total lysates of control and BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to Western blotting (WB) using the indicated antibodies. WB density of the NDUFS1 signal was quantitated and normalized to that of β-Actin (labeled Actin). n = 6 independent experiments. (d) Immunofluorescence staining was performed in 12-month WT and A53T-αSyn mouse sections using anti-NDUFS1 and anti-TH antibodies. Fluorescence intensity of NDUFS1 was quantified per TH+ cell, and the average was obtained for each repeat. n = 3 mice/group; scale bar: 100 μm. (e) Total lysates from the midbrains of postmortem healthy individuals and PD patients were analyzed via Western blot using anti-NDUFS1 and anti-β-Actin antibodies. NDUFS1 band density was normalized to β-Actin for each sample, then all samples were normalized to the average of the control group. n = 7 healthy, 6 PD. (f) Coimmunoprecipitation was performed on SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either myc or A53T-αSyn-myc plasmids, with anti-BCKDK antibody. IgG was used as a negative control. After pulldown, samples were assessed via Western blot using anti-NDUFS1 and anti-BCKDK antibodies; NDUFS1 signal density was normalized to BCKDK signal density, and the myc and A53T- αSyn-myc groups were compared. n = 3 independent experiments. (g) Proximity ligation assay was conducted on 12-month WT and A53T-αSyn mouse brain sections using anti-BCKDK and anti-NDUFS1 antibodies. Fluorescent puncta represent the proximity between the two proteins. n = 3 mice/group; scale bar: 100 μm. (h) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with αSyn tagged with N and C fragments of the Venus fluorophore and either control shRNA, NDUFS1 shRNA, BCKDK shRNA, or NDUFS1 shRNA and BCKDK shRNA. Cells were imaged 48 h after transfection. Fluorescence intensity per expressing cell was quantified. n = 4 independent experiments. (i) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with αSyn tagged with N and C fragments of the Venus fluorophore and either control plasmids (ctl shRNA and myc), NDUFS1-myc expression plasmid, or BCKDK shRNA. Cells were imaged 48 h after transfection and fluorescence intensity per expressing cells was quantified. n = 3 independent experiments. All data shown are mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments; all data are analyzed using either Student’s t test or One-way ANOVA

Further, co-immunoprecipitation using an anti-BCKDK antibody demonstrated BCKDK and NDUFS1 binding in cells, and the interaction was significantly reduced in our stable A53T-αSyn expressing SH-SY5Y cell line (31% decrease; p = 0.016) (Fig. 4f). Proximity ligation assay (PLA) on 12-month WT and A53T-αSyn expressing mouse tissue confirmed the binding between BCKDK and NDUFS1 in vivo. Again, a reduction of PLA positive puncta between BCKDK and NDUFS1 was observed in A53T-αSyn PD mouse brains (58% decrease; p < 0.0001, Fig. 4g).

Next, we examined if the αSyn oligomerization induced by BCKDK loss depends on NDUFS1 deficiency. To address this, we conducted an αSyn BIFC assay on HEK293T cells with BCKDK knockdown, NDUFS1 knockdown, or a double knockdown. HEK293T cells were used because of their high transfection efficiency compared to SH-SY5Y cells. We hypothesized that if BCKDK influences αSyn pathology primarily through NDUFS1, then knocking down both proteins would not exacerbate αSyn oligomerization beyond what was observed with either single knockdown. We found that, indeed, knockdown of either NDUFS1 or BCKDK caused a similar increase in αSyn oligomerization, and the double knockdown did not produce any further increase (Fig. 4h, Suppl. Figure 4c). To further investigate this relationship, we determined whether compensating for NDUFS1 loss rescues αSyn pathology observed in BCKDK deficient cells. We expressed an NDUFS1 construct in BCKDK knockdown cells and then conducted an αSyn BiFC assay. While BCKDK knockdown led to a 49% increase in αSyn oligomerization, expression of NDUFS1 significantly rescued this phenotype (Fig. 4i). These lines of evidence support our hypothesis that BCKDK and NDUFS1 may operate on the same pathway to promote αSyn oligomerization. Collectively, our data suggest that BCKDK binds to Complex I via NDUFS1, and that the loss of this binding destabilizes the complex I and incurs mitochondrial damage. This mitochondrial impairment likely drives the αSyn pathology observed in BCKDK-deficient models of PD.

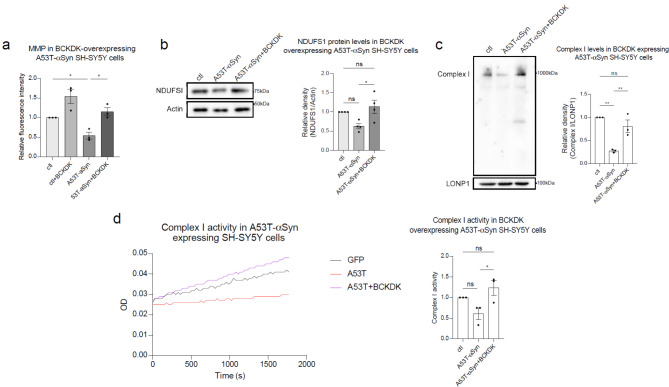

BCKDK overexpression restores mitochondrial function in cells expressing mutant αSyn

To determine whether replenishing BCKDK levels could mitigate PD-associated cell damage, we overexpressed a BCKDK-myc construct in stable A53T-αSyn expressing SH-SY5Y cell lines and assessed various aspects of mitochondrial function (Suppl. Figure 5a). We found that the MMP, measured using TMRM fluorescent dye, was reduced (45% decrease; p = 0.042) in mutant αSyn expressing cells. Significantly, BCKDK overexpression rescued this loss, restoring the MMP to near-normal levels (Fig. 5a). Next, we evaluated NDUFS1 protein levels by western blot analysis, as NDUFS1 is a key subunit of Complex I and has been shown to interact with BCKDK (Fig. 4). In line with previous findings (Fig. 4), NDUFS1 expression was reduced in A53T-αSyn expressing cells, but this reduction was reversed by the expression of BCKDK, supporting the notion that the NDUFS1-BCKDK interaction plays a role in stabilizing NDUFS1 assembly and preventing its loss (Fig. 5b). This rescue of the Complex I subunit corresponds with a rescue of the complex itself: we measured Complex I levels in these DA neurons using Blue Native PAGE and again found that transfection of mutant αSyn expressing cells with BCKDK-myc restores Complex I to approximately normal levels (Fig. 5c). Lastly, we assessed Complex I activity using an NADH-based assay. A53T-αSyn expressing cells exhibited a reduction in complex activity, and BCKDK overexpression rescued this loss, indicating that BCKDK expression was sufficient to restore both Complex I level and activity (Fig. 5d). These lines of findings emphasize that BCKDK is required for maintaining mitochondrial health and protecting against αSyn-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in PD models.

Fig. 5.

BCKDK expression rescues mitochondrial function in A53T-αSyn cell models. (a) SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either myc or A53T-αSyn were transfected with BCKDK-myc for 48 h, then stained with TMRM fluorescence dye to measure mitochondrial membrane potential. Fluorescence intensity was quantified per field of view and normalized to the number of cells. Averages for each repeat are shown in the accompanying histogram. n = 3 independent experiments. (b) Total lysates were harvested from stable myc or A53T-αSyn cells transfected with BCKDK-myc for 48 h and subjected to Western blot. Band density of NDUFS1 was normalized to β-Actin (labeled Actin). n = 4 independent experiments. (c) Blue Native PAGE was conducted with mitochondrial fractions to detect Complex I. LonP1, a mitochondrial matrix protein, was used as a mitochondrial loading control. Complex I was marked using an anti-NDUFS6 antibody. n = 3 independent experiments. (d) Complex I activity was assessed using a Complex I enzyme activity assay kit. The resulting slopes were compared as measures of complex activity. n = 3 independent experiments. All data shown are mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments and were analyzed using One-way ANOVA

BCKDK expression ameliorates PD phenotypes in DA neurons derived from patient iPS cells

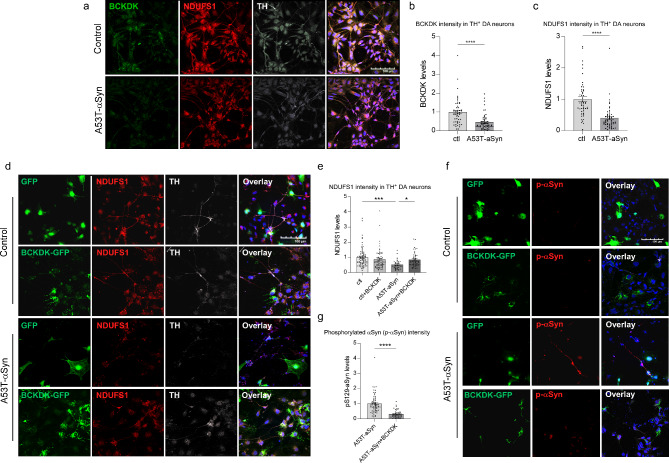

DA neurons were differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from PD patients carrying the A53T-αSyn mutation using our established protocol [34, 37, 38]. Three independent differentiations were conducted, with a DA neuron differentiation efficiency of 24–28% per group. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a significant reduction in both BCKDK (64% decrease; p < 0.0001) and NDUFS1 (60% decrease; p < 0.0001) expression in TH+ neurons derived from A53T-αSyn-expressing PD patient iPSCs compared to isogenic controls (Fig. 6a-c). To investigate the therapeutic potential of BCKDK, we transduced iPSC-derived neurons with a GFP-tagged lentiviral BCKDK construct for 48 h, resulting in a partial restoration of NDUFS1 levels (Fig. 6d, e). This suggests that BCKDK re-expression can mitigate NDUFS1 loss in PD-derived DA neurons, which may ameliorate Complex I loss and mitochondrial dysfunction in disease conditions.

Fig. 6.

BCKDK expression rescues neuronal damage in DA neurons derived from PD patient iPSCs. iPSCs derived from A53T- αSyn expressing PD patients and their isogenic controls were differentiated into DA neurons. Three independent differentiations were performed. (a-c) Cells were stained using anti-BCKDK, anti-NDUFS1, and anti-TH antibodies. Average fluorescence intensity per TH+ cell was quantified; fluorescence intensities normalized to the average of the control group are shown in histograms. n = 3 independent experiments. (d, e) Differentiated cells were infected with either GFP or BCKDK-GFP lentivirus for 48 h, fixed, and stained for NDUFS1. Fluorescence intensity per TH+ cell was quantified and normalized to average of the control group. n = 3 independent experiments. (f, g) Differentiated cells were infected with either GFP or BCKDK-GFP lentivirus for 48 h, fixed, and stained for phosphorylated Ser129 αSyn. Fluorescent intensity per TH+ cell was quantified; all values were normalized to the average of the control group. n = 3 independent experiments. Each data point represents one TH+ cell. All data shown are mean ± SEM; individual data points represent relative fluorescent intensity of single cells. Data were analyzed using either Student’s t test or One-way ANOVA

Phosphorylation of αSyn at Ser129 promotes the accumulation of oligomeric αSyn, accelerates aggregate formation in neurons, and induces neuronal loss in mouse models [39–41]. Elevated levels of αSyn-pS129 were observed near fragmented mitochondrial membranes in DA neurons from A53T-αSyn PD patient iPSCs, with no enrichment on ER or Golgi membranes, indicating that αSyn-pS129 is closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction [42]. Consistent with our previous findings [34], we observed a significant increase in pS129 αSyn in DA neurons derived from A53T-αSyn PD iPSCs. Notably, BCKDK overexpression significantly reduced pS129 αSyn levels (Fig. 6f, g), further supporting the role of BCKDK in alleviating αSyn pathology. These findings indicate that BCKDK restoration may offer a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate αSyn aggregation and neurodegeneration in PD.

Discussion

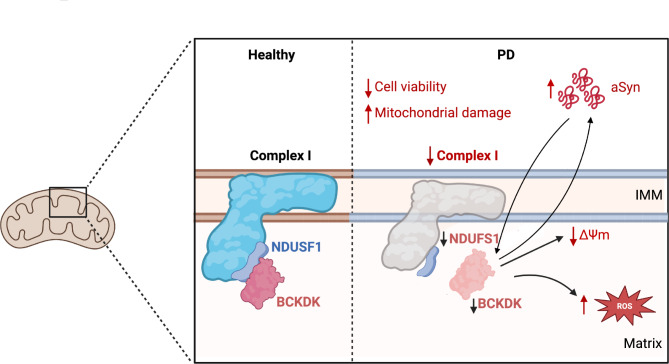

Previous computational analyses of PD patient genetic data have identified a host of risk factors potentially affecting disease progression [22, 23]. In this study, we focus on one of these mitochondrial risk factors, BCKDK, and delineate its role in αSyn pathology and PD progression. First, we establish the loss of BCKDK as a biologically relevant risk factor in PD, showing that BCKDK protein levels are consistently and selectively reduced in DA neurons in PD patients and in mutant αSyn expressing mouse disease models. Second, we find that BCKDK loss compromises mitochondrial function, and more specifically, Complex I function, and that this relationship is mediated by the direct binding of BCKDK to the Complex I subunit NDUFS1. We also observe that BCKDK deficiency promotes αSyn oligomerization, and that this exacerbation of αSyn pathology is mediated by the loss of NDUFS1 that accompanies the loss of BCKDK. Third, we confirm that overexpression of BCKDK in mutant αSyn expressing cells rescues Complex I levels and function. This extends to our patient-derived iPSC models, where BCKDK expression corrects both NDUFS1 levels and αSyn phosphorylation. In summary, our findings establish a new risk factor in PD-associated mitochondrial and αSyn dysfunction (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic summarizing the effects of BCKDK loss

The primary function of BCKDK, and its most common avenue of study, is as a kinase that regulates branched chain amino acid metabolism by acting on the complex BCKD. BCKDK phosphorylates the BCKDHA subunit on Ser-337, resulting in the inactivation of its enzymatic activity [43]. Several conditions associated with BCKDK involve altered BCAA levels in the bloodstream or tissue. Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD), for example, is characterized by elevated plasma BCAA levels caused by mutations in the subunits of BCKD, and BCAA depletion is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [30, 44–46]. Our work, however, reveals a novel mechanism by which BCKDK acts on the mitochondria and on cellular metabolism as a whole. We demonstrate that BCKDK binds to the Complex I subunit NDUFS1, which is exposed within the mitochondrial matrix. NDUFS1 is the largest subunit of Complex I, at 75 kDa, located on the mitochondrial inner membrane; it is a component of the iron-sulfur fragment of the enzyme that has NADH dehydrogenase and oxidoreductase activity, and its loss results in deficits in oxidative phosphorylation [47, 48]. The binding of NDUFS1 to BCKDK potentially stabilizes NDUFS1 and Complex I, and we suspect that the reduction in BCKDK levels lessens NDUFS1 stability, and therefore Complex I stability, sufficient to cause an increase in Complex I degradation.

Similarly, mutant αSyn expressing cells exhibit a decrease in Complex I levels and activity; it is unclear if this change is mediated in a significant manner by the loss of BCKDK. We have observed a reduction in BCKDK protein levels in A53T-αSyn expressing cells, but only moderately, and it is as of yet undetermined the extent of its effect on Complex I. We do find, however, that expression of myc-tagged BCKDK in mutant αSyn expressing SH-SY5Y cells rescues both Complex I levels and activity, suggesting that the protein plays some role in Complex I dysfunction in these mutant cells. Future studies should aim to determine the contact points and stability of this binding, and the impact of the interaction on Complex I stability. We hypothesize that BCKDK deficiency reduces Complex I stability and therefore causes an increase in its degradation. It is also unknown what, if any, other direct interactions BCKDK has and how these may impact mitochondrial function.

Interestingly, we note a seemingly circular relationship between BCKDK and αSyn. Cell models overexpressing A53T-αSyn display reduced BCKDK levels, while cells with a BCKDK deficiency exhibit worsened αSyn pathology, represented by an increase in αSyn oligomerization. We suspect that the two proteins are interrelated, and that dysregulation of either protein would drive further dysregulation of the other, resulting in a positive feedback loop that causes progressive cell degeneration. Though we claim that BCKDK and αSyn act on one another, we cannot draw any conclusions about the initial modes of dysregulation in PD. In other words, it is unclear whether BCKDK dysregulation precedes αSyn accumulation, or vice versa. Previous studies have noted that BCAA levels are reduced in the plasma of PD patients, both at early and late stages [49]. We examined the effects of BCAA deprivation in cell culture by exposing SH-SY5Y cells to leucine-free media for seven days. These cells express moderately reduced levels of BCKDK and exhibit greater αSyn oligomerization as demonstrated by BIFC assay. This increase in αSyn oligomerization is rescued by BCKDK overexpression (Suppl. Figure 5b, c). One possibility is that early BCAA dysregulation in PD patients drives both BCKDK and αSyn imbalances, which then continue to influence each other. However, more work needs to be done before any conclusions can be drawn in this regard.

To conclude, we establish that the patterns seen in mouse and cell models of PD are also present in our iPSC lines. Specifically, we observe a decrease in BCKDK and NDUFS1 levels in iPSCs derived from patients with familial A53T-αSyn-associated PD. We also find that expressing BCKDK in these PD patient-derived cells partially rescues NDUFS1 levels and attenuates αSyn pathology, measured via phosphorylation levels. Future studies should assess the impact of BCKDK overexpression on the development and progression of Parkinsonism in mouse models. Induction of BCKDK expression in A53T-αSyn expressing mice via adeno-associated virus (AAV) injection would allow us to determine whether early administration of BCKDK can prevent or ameliorate the neurological and behavioral defects associated with disease.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

BCKDK (sc-374425; immunoblotting: 1:100, immunostaining: 1:25) and BCKDE1A (sc-67200; immunoblotting: 1:1000) antibodies was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. NDUFS1 (68253-1-Ig, 12444-1-1AP; immunoblotting: 1:1000, immunostaining: 1:400), NDUFS6 (14417-1-AP; immunoblotting: 1:1000), and LONP1 (15440-1-AP; immunoblotting: 1:3000), BCAT1 (13640-1-AP, immunoblotting: 1:1000), and ATPB (17247-1-AP; immunoblotting: 1:3000) antibodies were from Proteintech. ß-actin (A1978, immunoblotting: 1:10000) and IgG (12–370; coimmunoprecipitation: 2ug) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. αSyn phospho-S129 (ab168381; immunostaining: 1:1000), αSyn aggregate (ab209538; immunostaining: 1:1000), tyrosine hydroxylase (ab76442; immunostaining: 1:500), and the OXPHOS complex antibody cocktail (ab110413; immunoblotting: 1:1000) were from Abcam. Tyrosine hydroxylase (MAB318) antibody was purchased from Millipore. MPP+ (D048), protease inhibitor, and protein phosphatase inhibitor were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DAPI (D1308) and secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor #A-11008, #A-11001, #A-11011, #A-11004, #A-21449) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either a pLKO3.1 control shRNA (Addgene; #8453) or BCKDK shRNA plasmid (Sigma-Aldrich; TRCN0000199200) were cultured in 1:1 DMEM/F12 media with 10% FBS, 100ug/ml penicillin, 100ug/ml streptomycin, and 1ug/ml puromycin. Myc, myc-αSyn WT, or myc-αSyn A53T [34] expressing stable SH-SY5Y cell lines were cultured in FBS (10%) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%) supplemented DMEM/F12 media treated with 400ug/ml G418. BCKDK-myc plasmid was purchased from Origene (RC203601). Leucine-free media was from ThermoFisher (#30030); cells were cultured in 1:1 leucine-free DMEM/F12 media supplemented with FBS (10%) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%). HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM media supplemented with FBS (10%) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%). Cells were kept in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator.

Induced pluripotent stem cells and neuronal differentiation

The PD iPS cell line (RUCDR Infinite Biologics; αSyn A53T; NN0004337) and its isogenic control (NN0004344) were differentiated into dopaminergic neuron-enriched cultures as described in [37, 50]. Briefly, iPS cell colonies were plated on Matrigel (2.5%) coated plates in mTeSR media, treated with SB431542 (10 μm) and Noggin (100ng/ml) in Neural Media (NM; Neurobasal and DMEM/F12 (1:1), B-27 Supplement Minus Vitamin A, N2 Supplement, GlutaMAX, 100units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) with FGF2 (20ng/µl) and EGF (20ng/µl) for 7 days, then treated with human recombinant Sonic hedgehog (SHH, 200ng/ml) in neuronal differentiation medium (Neurobasal and DMEM/F12 (1:3), B27, N2, GlutaMax and P/S) for 4 days. Cells were then incubated in neuronal differentiation medium containing BDNF (20ng/ml), ascorbic acid (200 μm), SHH (200ng/ml), and FGF8b (100ng/ml) for 3 days, then treated with BDNF, ascorbic acid, GDNF (10ng/ml), TGF-b (1ng/ml), and cAMP (500 μm). All growth factors were from Pepro Tech. Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine/laminin coated coverslips. Three independent differentiations were performed, each lasting 27 days. Differentiating iPSCs were infected at day 25 with either GFP or BCKDK-GFP lentivirus using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of one, then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde after 48 h for staining. Lentiviral vectors (GFP: pLV[Exp]-EF1A>/EGFP; BCKDK-GFP: pLV[Exp]-EF1A > hBCKDK[NM_005881.4]/EGFP) were constructed and packaged by VectorBuilder.

Animal model and PD patient tissue

αSyn A53T [B6.Cg-Tg(Prnp-SNCA*A53T)23Mkle/J, JAX Stock No: 006823] breeders (C57Bl/6J genetic background) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University and were performed based on the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male mice were used and were maintained at 12 h light/dark cycles.

Postmortem patient samples were obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NeuroBioBank under the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB). All donated specimens were assessed by board-certified neuropathologists to establish a disease condition diagnosis. Age-matched tissue sections from 3 healthy individuals (1 female, 2 male) and 3 PD patients (1 female, 2 male) were used in immunostaining. For immunoblotting, midbrain lysates from a total of 7 healthy male subjects and 6 male PD patients were assessed. Patient information is provided in the Supplemental Information (Suppl. Figure 1e, Suppl. Figure 4b).

Immunoblotting

Total cell lysates were extracted by first washing cells with 1X PBS, then incubating them in total lysis buffer (10mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.9], 150mM NaCl, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) at 4 °C for 30 min. Lysates were collected and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 g; the supernatant was collected for immunoblotting analysis. Protein concentrations were measured via Bradford assay, and samples were prepared in Laemmli buffer with equal amounts of total protein. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the appropriate antibodies. Blots were visualized with ECL. The resulting bands were analyzed using ImageJ; intensity of each band was measured and normalized to the indicated loading control. Mouse samples run concurrently were normalized to the average of the control (WT) samples.

Blue native PAGE

Mitochondrial fractions were isolated by washing cells with PBS, then incubating them in mitochondrial lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, protease inhibitor cocktail, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min at 4 °C. Lysates were collected and homogenized using a 25-gauge needle. Homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4 °C; supernatants were then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The remaining pellets were washed with mitochondrial lysis buffer and spun again at 10,000 g for 20 min. Mitochondrial pellets were incubated on ice in 1x NativePAGE Sample Buffer (NativePAGE™ Sample Prep Kit; Thermo Fisher; BN2008) containing 2% Digitonin (sigma, D141) for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations of the resulting supernatant were determined, and samples were prepared with NativePAGE 5% G-250 Sample Additive. Samples were run on pre-cast native 4–16% Bis-Tris gels using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, then either incubated in Brilliant Blue R staining solution or transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed using the indicated antibodies. Gels incubated in Brilliant Blue were transferred to Coomassie destaining solution overnight. Band densities for immunoblots were normalized to LonP1, which was used as a loading control, and stained gels were normalized to total protein levels.

Immunostaining

Mouse sections were obtained from 12-month control and A53T-αSyn expressing mice that were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Frozen brain sections were used for all tissue staining; sections were permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS buffer for 5 min, blocked in 6% normal goat serum with 0.3% Triton X-100 for one hour, then incubated in primary antibody diluted in 3% normal goat serum with 0.3% Triton X-100 overnight at 4 °C, then with the appropriate 488/568/633/647nm secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. All incubation was performed in a humidified chamber, and slides were washed three times for 5 min each using PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 after each step. Slides were incubated with DAPI for 10 min at room temperature to stain nuclei, then mounted (Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium; Agilent; S302580-2).

Frozen tissue sections from postmortem healthy individuals and PD patients were used for staining; sections were permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, then blocked for one hour in 6% normal goat serum with 0.3% Triton X-100. Slides were incubated in the indicated primary antibodies, diluted using 3% normal goat serum with 0.3% Triton X-100, and placed in a humidity chamber at 4 °C overnight. Slides were then incubated with 488/568nm secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Slides were washed using 0.1% PBS-Triton X-100 three times after every step. Stained tissue was mounted using Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium.

All immunostained sections were imaged using an Olympus confocal microscope. Staining was quantified as fluorescence intensity per cell expressing the indicated marker, as measured using ImageJ, and averages were taken for each biological repeat.

Proximity ligation assay

Mouse tissue sections were permeabilized using 0.1% PBS-Triton X-100 for 5 min, then blocked with PLA blocking buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C in BCKDK and NDUFS1 antibodies; this was followed by incubation in the provided PLA probes (Rabbit PLUS, Mouse MINUS In Situ PLA Probes; Sigma-Aldrich; DUO92002) for 1 h at 37 °C. Samples were incubated in ligase buffer for 30 min at 37 °C, then in amplification buffer for 100 min at 37 °C. Slides were mounted using Duolink In Situ Mounting Medium with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; DUO82040), and mounted slides were imaged using confocal microscopy. Fluorescence intensity was measured for each field of view using ImageJ software, then normalized to the number of cells, determined using DAPI-stained nuclei.

AlphaFold2

BCKDK (O14874) and NDUFS1 (P28331) amino acid sequences were obtained from the UniProtKB database. Structure prediction was conducted as described in [36] using the provided code.

αSyn BIFC

SH-SY5Y or HEK293T cells were cultured on coverslips coated with a gelatin-fibronectin solution (1% gelatin; 0.5% fibronectin) and a poly-D-lysine-laminin solution (0.1 mg/ml PDL overnight at 4 °C; 5ug/ml laminin for 1 h at 37 °C), respectively. Cells were transfected with two tagged αSyn plasmids, VN-αSyn (Addgene #89470) and αSyn-VC (Addgene #89471) for 48 h, then treated with DAPI for 10 min, washed 3 times with PBS, and mounted using Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium. Where indicated, cells were co-transfected with BCKDK shRNA (Sigma-Aldrich; TRCN0000199200), NDUFS1 shRNA (Sigma-Aldrich; TRCN0000064631), or NDUFS expression plasmid (DNASU; HsCD00860978). Mounted coverslips were imaged using an Olympus confocal microscope at 405 nm and 488 nm. Fluorescence intensity at 488 nm was quantified per cell, indicated by DAPI signal, using ImageJ software. Averages were taken for each biological repeat.

Acetyl CoA ELISA

Cells were pelleted, washed, and lysed in PBS using a water bath sonicator (3 × 1 min, 80 kHz). Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 g, and kit instructions (A-CoA ELISA kit; Elabscience; E-EL-0125) were used to measure Acetyl CoA levels. In brief, samples were added to the Micro ELISA plate for 90 min, followed by the provided Biotinylated Detection Ab, HRP Conjugate, and Substrate reagent. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Mouse samples run concurrently were normalized to the average of the control (WT) samples.

Measurement of Complex I activity

Control and BCKDK KD SH-SY5Y cell pellets were collected, washed, and lysed in PBS using a water bath sonicator (3 × 1 min, 80 kHz). Detergent (Complex I Enzyme Activity Assay Kit; Abcam; ab109721) was added and samples were left on ice for 30 min, then centrifuged at 16,000 g for 20 min. Complex I activity was then determined over the course of 30 min by following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, plates were incubated with lysates for 3 h, then washed and incubated with the provided NADH/dye solution. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm every 20 s for 30 min.

Measurement of cell viability

Stable control and BCKDK knockdown cells were cultures in 96-well plates and were assayed using a Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich; #11644793001). Cells were incubated in fresh media for 6 h prior to assay; 30 min prior to assay, 1% Triton X-100 was added to the “high control” group. Media was collected from each well into a new 96-well plate and freshly prepared reaction solution, provided in the kit, was added to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, then absorbance was measured at 492 nm and 692 nm (for background). Results were quantified as a percentage of LDH release in comparison to the “high control” group.

Measurement of cell proliferation

Stable control and BCKDK knockdown cells were plated in 96-well plates, treated with MPP+ (1mM, 48 h), then incubated at 37 °C with the two reagents (MTT labeling agent, 4 h; Solubilization solution, 16 h) provided in the MTT assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich; #11465007001). Absorbance was measured at 590 nm and 690 nm (as background). Sample absorbances were normalized to those of the control cells.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Stable control and BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells were cultured on coverslips coated overnight at 4 °C with a gelatin-fibronectin solution (1% gelatin; 0.5% fibronectin), treated with MPP+ (1mM, 48 h), then incubated with 0.25 μm TMRM and DAPI for 25 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were washed 3 times with PBS, then mounted using a mounting medium (Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium; Agilent; S302580-2). Coverslips were imaged using a Keyence BZ-X700 microscope, and the resulting images were analyzed using the ImageJ software. Total fluorescence intensity of the red channel and number of cells (using DAPI) were quantified for each field of view. The average fluorescence intensity for each group was taken for each biological repeat.

Measurement of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Stable control and BCKDK knockdown SH-SY5Y cells were cultured on coverslips coated overnight at 4 °C with gelatin-fibronectin, treated with MPP+ (1mM, 48 h), then incubated in 5 μm MitoSOX Red fluorescent dye (Invitrogen, M36008) and DAPI for 10 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were washed 3 times with PBS, then mounted using a mounting medium (Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium; Agilent; S302580-2). Coverslips were imaged using a Keyence BZ-X700 microscope, and the resulting images were analyzed using the ImageJ software. Total fluorescence intensity of the red channel and number of cells (using DAPI) were quantified for each field of view. The average fluorescence intensity for each group was taken for each biological repeat.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Total cell lysates were prepared from SH-SY5Y cells as described above. Total protein concentrations were measured using Bradford assay, and 1 mg of protein in 1 ml of total lysis buffer was incubated with 2ug of either BCKDK primary antibody or control IgG antibody overnight at 4 °C with slow rotation. Protein A/G beads (30ul; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-2003) were added and slowly shaken for 2 h at 4 °C, then centrifuged and washed 4 times with total lysis buffer (4000 g x 3 min). Laemmi buffer (15ul) was added and samples were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min, cooled, and centrifuged again; immunoblotting was then performed on the resulting supernatant using the indicated antibodies. NDUFS1 protein levels were quantified using ImageJ and normalized to BCKDK protein levels for each pulldown group. Total lysates not subjected to immunoprecipitation were also assessed to confirm expression of the proteins of interest.

Proteomic analysis

Control and BCKDK knockdown cells were harvested, lysed using 2% SDS, and probe sonicated twice. Samples were prepared using filter-aided sample preparation (FASP), as described in [51]. Samples were washed in acetone, reduced in 10mM DTT in 3 M urea with water bath sonication, alkylated with 25mM iodoacetamide, then digested using trypsin/Lys-C. Samples were diluted in 0.1% formic acid for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

Lysed proteins from each group were loaded onto a column with blanks in between. Data were acquired using an Orbitrap Velos Elite mass spectrometer equipped with a Waters nanoACQUITY LC system. Peptides were desalted on a trap column and resolved on a reversed-phase column, then were introduced into the nanospray mode. Peptides in the range of 380 to 1800amu were scanned for; the proteins were identified with Mascot and quantified.

Statistical analysis

All cell culture and animal experiments were conducted with at least three independent repeats. Data were analyzed using either the Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test for comparison across groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the NIH NeuroBioBank for providing the human postmortem brain tissues and brain donors and their families for the tissue samples used in this study.

Author contributions

A.J. performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. D.H. collected animal samples and cultured DA neurons derived from iPS cells. Y.T.S, R.H.W and S.A.G assisted in experimental design and data analysis. X.Q. conceived, designed, and supervised all the studies and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01AG065240, R01NS115903, R01AG076051 and RF1AG074346 to X.Q.); Vinney Scholar Award for Alzheimer’s disease to X.Q.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by Case Western Reserve University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed based on the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sufficient procedures were employed to reduce the pain and discomfort of the mice during the experiments. Postmortem patient samples were obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NeuroBioBank under the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Research Ethics Board. All brains were donated to the NBB by informed consent through the Brain and Tissue Repositories sites.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Poewe W et al (2017) Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ (1991) Ageing and parkinson’s disease: Substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radhakrishnan DM, Goyal V (2018) Parkinson’s disease: A review. Neurol India. 10.4103/0028-3886.226451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tysnes OB, Storstein A (2017) Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm 124 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Beitz JM (2014) Parkinson’s disease: A review. Front Biosci - Sch. 10.2741/s415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perier C, Vila M (2012) Mitochondrial biology and Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 10.1101/cshperspect.a009332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Turnbull DM, Reeve AK (2019) Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—cause or consequence? Biology 8:38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JS, Davis RL, Sue CM (2018) Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: New Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 10.1007/s11910-018-0829-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo X et al (2013) Inhibition of mitochondrial fragmentation diminishes Huntington’s disease-associated neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest 123:5371–5388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos D, Esteves AR, Silva DF, Januário C, Cardoso SM (2015) The impact of mitochondrial fusion and fission modulation in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. mol neurobiol 52 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK (2008) Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M710012200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.González-Rodríguez P et al (2021) Disruption of mitochondrial complex I induces progressive parkinsonism. Nature 599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Dias V, Junn E, Mouradian MM (2013) The role of oxidative stress in parkinson’s disease. J Park Dis 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Henderson MX, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2019) Y. α-Synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease and related α-synucleinopathies. Neurosci Lett 709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Calabresi P et al (2023) Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies: from overt neurodegeneration back to early synaptic dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Vicario M, Cieri D, Brini M, Calì T (2018) The close encounter between alpha-synuclein and mitochondria. Front Neurosci 12:388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Maio R et al (2016) α-synuclein binds to TOM20 and inhibits mitochondrial protein import in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 8:78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surmeier DJ, Obeso JA, Halliday GM (2017) Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Choi ML et al (2022) Pathological structural conversion of α-synuclein at the mitochondria induces neuronal toxicity. Nat Neurosci 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Blauwendraat C et al (2020) Genetic modifiers of risk and age at onset in GBA associated Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Brain. 10.1093/brain/awz350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nalls MA et al (2019) Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang D et al (2017) A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat Genet 49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Nalls MA et al (2014) Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet 46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Charlton M (2006) Branched-chain amino acids: Metabolism, physiological function, and application. J Nutr [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wynn RM et al (2004) Molecular mechanism for regulation of the human mitochondrial branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex by phosphorylation. Structure 12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Oyarzabal A et al (2016) Mitochondrial response to the BCKDK-deficiency: Some clues to understand the positive dietary response in this form of autism. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohl L et al (2024) Partial suppression of BCAA catabolism as a potential therapy for BCKDK deficiency. Mol Genet Metab Rep 39:101091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwasa M et al (2013) Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Reduces Oxidative Stress and Prolongs Survival in Rats with Advanced Liver Cirrhosis. PLoS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mor DE et al (2020) Metformin rescues Parkinson’s disease phenotypes caused by hyperactive mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA 10.1073/pnas.2009838117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Tangeraas T et al (2023) BCKDK deficiency: a treatable neurodevelopmental disease amenable to newborn screening. Brain 146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Langmyhr M et al (2021) Allele-specific expression of Parkinson’s disease susceptibility genes in human brain. Sci Rep 11:504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z et al (2023) BCKDKrs14235 A allele is associated with milder motor impairment and altered network topology in Parkinson’s disease

- 33.Lee MK et al (2002) Human α-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53 → Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with α-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 99, 8968–8973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hu D et al (2019) Alpha-synuclein suppresses mitochondrial protease ClpP to trigger mitochondrial oxidative damage and neurotoxicity. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 137:939–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Outeiro TF et al (2008) Formation of Toxic Oligomeric α-Synuclein Species in Living Cells. PLoS ONE 3:e1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jumper J et al (2021) Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Su YC, Qi X (2013) Inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission reduced aberrant autophagy and neuronal damage caused by LRRK2 G2019S mutation. Hum Mol Genet 22:4545–4561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen HN et al (2011) LRRK2 Mutant iPSC-Derived DA Neurons Demonstrate Increased Susceptibility to Oxidative Stress. Cell Stem Cell 8:267–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawahata I, Finkelstein DI, Fukunaga K (2022) Pathogenic Impact of α-Synuclein Phosphorylation and Its Kinases in α-Synucleinopathies. Int J Mol Sci 23:6216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson JP et al (2006) Phosphorylation of Ser-129 Is the Dominant Pathological Modification of α-Synuclein in Familial and Sporadic Lewy Body Disease. J Biol Chem 281:29739–29752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karampetsou M et al (2017) Phosphorylated exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils exacerbate pathology and induce neuronal dysfunction in mice. Sci Rep 7:16533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan T et al (2018) Cardiolipin exposure on the outer mitochondrial membrane modulates α-synuclein. Nat Commun 9:817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch CJ, Adams SH (2014) Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Blackburn PR et al (2017) Maple syrup urine disease: Mechanisms and management. Appl Clin Genet 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Strauss KA et al (2020) Branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase deficiency (maple syrup urine disease): Treatment, biomarkers, and outcomes. Mol Genet Metab 129 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Gao Q et al (2024) The association between branched-chain amino acid concentrations and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in preschool-aged children. Mol Neurobiol 61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Li JL et al (2021) Mitochondrial Function and Parkinson’s Disease: From the Perspective of the Electron Transport Chain. Front Mol Neurosci 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Read AD, Bentley RE, Archer SL, Dunham-Snary KJ (2021) Mitochondrial iron–sulfur clusters: Structure, function, and an emerging role in vascular biology: Mitochondrial Fe-S Clusters – a review. Redox Biol 47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Zhang Y et al (2022) Plasma branched-chain and aromatic amino acids correlate with the gut microbiota and severity of Parkinson’s disease. Npj Park Dis 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Nguyen HN et al (2011) LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M (2009) Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods 6 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.