Abstract

Background:

Acupuncture is a promising treatment for common symptoms after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Our objectives were to explore knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acupuncture, identify health service needs, and assess the perceived feasibility of weekly acupuncture visits among individuals with TBI.

Methods:

We surveyed adults 18 years of age and older with TBI who received care at the University of Washington. Respondents were asked to complete 143 questions regarding acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, injury-related symptoms and comorbidities, and to describe their interest in weekly acupuncture.

Results:

Respondents (n=136) reported a high degree of knowledge about acupuncture as a component of Traditional Chinese Medicine, needle use and safety, but were less knowledgeable regarding that the fact that most conditions require multiple acupuncture treatments to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit. Respondents were comfortable talking with healthcare providers about acupuncture (63.4%), open to acupuncture concurrent with conventional treatments (80.6%) and identified lack of insurance coverage as a barrier (50.8%). Beliefs varied, but respondents were generally receptive to using acupuncture as therapy. Unsurprisingly, respondents with a history of acupuncture (n=60) had more acupuncture knowledge than those without such a history (n=66) and were more likely to pursue acupuncture without insurance (60%), for serious health conditions (63.3%) or alongside conventional medical therapy (85.0%). Half of all respondents expressed interest in participating in weekly acupuncture for up to 12 months and would expect almost a 50% improvement in symptoms by participating.

Conclusion:

Adults with TBI were receptive and interested in participating in weekly acupuncture to address health concerns. These results provide support for exploring the integration of acupuncture into the care of individuals with TBI.

Keywords: acupuncture, neurology, complementary medicine

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant public health concern worldwide.1 Over 2.7 million Americans are evaluated in emergency care or are hospitalized annually with TBI,2 and it is estimated that approximately 3 to 5 million individuals in the United States are living with a TBI-related disability.3–5 Rehabilitation efforts aim to restore self-care skills (including sleep quality) and motor, cognitive and social functioning.3,6 However, gaps remain in current rehabilitation methods and require individually tailored programs and innovative treatments to address the health effects that manifest after injury.3 Innovative approaches with considerable but largely unexplored potential include dietary supplements, novel uses of pharmaceuticals, mind-body practices, music therapy, and acupuncture.7

Acupuncture is increasingly popular in the United States but utilization remains low.8–10 Barriers to its use include low recommendations from healthcare providers and a general lack of familiarity.11–13 Additionally, a lack of insurance benefits for acupuncture might prohibit its utilization.3,14 Insurance coverage for acupuncture varies worldwide, with some countries offering coverage by both government entities and private insurance (e.g. Brazil) and other countries offering no insurance coverage at all (e.g. the Philippines).15 Differences in the recognition and regulation of acupuncture as a medical specialty might contribute to this variation. Specifically in the United States, how acupuncture is regulated varies state-to-state, ranging from oversight from its own medical quality board, having representation on inter-disciplinary medical boards, being included within the statutes governing other professions, or having oversight from within non-medical agencies—variations likely to affect insurance coverage, and therefore access.16 While acupuncture is increasingly becoming a reimbursable service in the United States, nearly half of visits with acupuncturists had no insurance coverage as of 2018.17

Acupuncture may have promise in TBI. For example, animal studies on TBI have demonstrated that acupuncture can decrease neuro-inflammation and scarring,18–20 increase synaptic plasticity,21 increase cerebral blood flow,22 and stimulate neuronal proliferation and differentiation.23–26 Although there is a paucity of research examining the effects of acupuncture in humans with TBI, acupuncture is a promising treatment in other populations for many symptoms that occur post-injury, such as headache,27 depression,28,29 and cognitive difficulties.30–32

Based on the current gaps in rehabilitation and the promise of acupuncture as a viable treatment post-TBI, the purpose of this study was to better understand and characterize knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acupuncture and health service needs in those with TBI. The specific objectives were to: (1) assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acupuncture among persons who have sustained TBI; (2) identify their health service needs based on TBI-related symptoms and comorbidities; and (3) determine their potential interest in participating in weekly acupuncture. We then compared differences in acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs between those with pre-existing acupuncture experience and those without a personal history of acupuncture.

METHODS

Study design and study sample

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in a convenience sample of adults who had sustained TBI at age 18 or older and were evaluated or treated within the University of Washington health system. ICD-10 codes beginning with S06 were used to identify those individuals with a TBI diagnosis. Individuals who could not speak or read English, or made two or more errors on the Six-Item Screener for Cognitive Functioning,33 were excluded. The survey was open from 1 August 2020 through 30 April 2021, and all participants provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington Human Subjects Division approved this study.

Survey information

The survey was comprised of seven data collection instruments. Respondents were asked to respond with information about their most recent injury and current symptomatology. All questions were voluntary and respondents could skip questions or withdraw from the survey at any time. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap),34 hosted through the Institute of Translational Health Sciences (ITHS) at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Demographics and context.

Respondents were queried about their gender, age, race, ethnicity and education. Frequency of poverty was based on federal poverty guidelines and calculated based on the number of persons in each household and household income. We also collected information on the duration of hospitalization after injury and whether the individual was discharged to home, to inpatient rehabilitation or to an assisted living facility. Respondents also provided information on prior acupuncture use.

Acupuncture experience.

For the individuals reporting acupuncture use, we asked about the frequency of acupuncture treatment, the reasons for the treatment, and whether the reasons were for personal wellness or for specific health concerns. The remaining respondents were asked to examine how likely they were to get acupuncture based on their current knowledge.

Acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs.

All three of the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs surveys included the option “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer.” Responses for knowledge questions were “true” and “false” (n=9). We then categorized these true/false responses into answers that were accurate and answers that were inaccurate. The option for “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer” was grouped with the inaccurate responses. Responses for attitudes used Likert-type scales35 with 1 = “strongly agree,” 2 = “agree,” 3 = “disagree,” 4 = “strongly disagree” (n=8). These were then collapsed into the following categories: “agree/strongly agree,” “disagree/strongly disagree,” and “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer.” Similarly, responses for beliefs also used Likert-type scales with 1 = “somewhat likely,” 2 = “very likely,” 3 = “somewhat unlikely,” 4 = “very unlikely” (n=7). These were also grouped into three categories: “somewhat likely/very likely,” “somewhat unlikely/very unlikely,” and “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer.”

Concurrent medical conditions.

Respondents were asked if a healthcare provider had informed them that they had or have any of the following: multiple TBIs, post-traumatic stress disorder, a psychological or psychiatric condition, addiction or a neurological condition such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, seizure disorder or Parkinson’s disease. Respondents answered this questionnaire by indicating “yes” or “no” to each medical condition.

TBI-related symptoms.

Respondents were asked about current symptoms related to the TBI. The 17-item TBI symptom checklist36,37 was adapted for use online without an interviewer. This instrument asks about new or worsening symptoms since the most recent TBI. Respondents indicated which of the 17 symptoms they had been experiencing since the injury. For each symptom present, respondents were then asked about the severity (1 = “not a problem,” 2 = “mild problem,” 3 = “moderate problem,” and 4 = “severe problem”) and if the symptom was new or was present prior to the most recent injury (1 = “yes,” 2 = “no”). If they responded “yes,” we asked if the symptom since the most recent injury had changed (1 = “remained the same,” 2 = “worsened,” or 3 = “better”).

Weekly acupuncture.

Respondents were asked to answer ten questions about their ability or interest to attend weekly acupuncture sessions that would require a one-hour appointment for twelve consecutive weeks, independent of insurance coverage or other monetary cost. We posed “yes” or “no” questions about having transportation and asked the respondents to indicate how much time weekly they could travel one-way in minutes (i.e. <15, 16–30, 31–45, >45). We also asked if respondents would consent to have acupuncture in a community-style clinic setting, versus consent to have acupuncture in a private room with only the acupuncturist present. To explore the acceptable total duration of an acupuncture intervention study, we asked what the maximum duration in weeks or months they would be willing to participate for if there were no changes in symptoms experienced, and the maximum duration they would be able to participate (options being four weeks, six weeks, two months, three months, four months, six months, nine months, twelve months). We also asked what degree of improvement would be considered meaningful to continue having weekly acupuncture during the course of treatment (0–100%) and what degree of improvement would be expected overall as a result of having weekly acupuncture (0–100%).

Analysis

Data were analyzed with R Studio version 4.0.3 statistical software.38 Responses were reported in a descriptive analysis as the percentages of all respondents for categorical variables and the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. We compared the responses for questions about comorbidities, TBI-related symptoms, and knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, between individuals reporting a history of acupuncture use and those who did not report a history of acupuncture use with Chi-square P values for categorical variables with values of 10 or more, and Fisher’s exact test P values for categorical variables that had values less than 10.

RESULTS

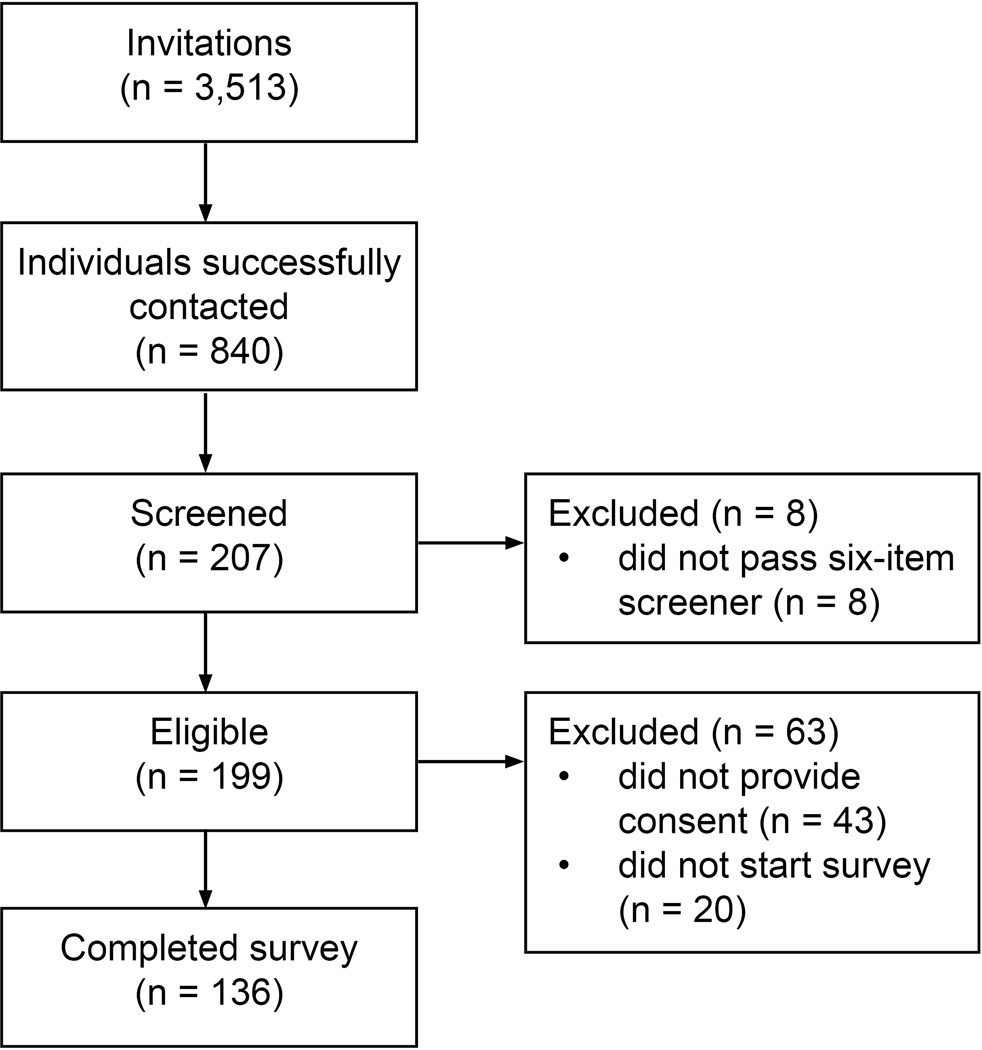

Figure 1 details our study flow. We invited 3,513 adults with TBI via telephone and email to participate in the survey. One hundred and thirty-six adults with a history of TBI responded to the survey during the study period. Of the 126 respondents who answered the question regarding acupuncture history, 60 (44.1%) reported having received acupuncture in the past, and 66 (48.5%) reported never having received acupuncture (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and item response rates

| Study sample (n=136) |

Acupuncture use (n=60) |

No acupuncture Use (n=66) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses n (%) | Value | Responses n (%) | Value | Responses n (%) | Value | P | |

|

| |||||||

| Age | 122 (89.7) | 46.8 ± 16.4 | 54 (90.0) | 47.4 ± 13.7 | 61 (92.4) | 45.2 ± 18.4 | — |

| Gender | 128 (94.1) | 56 (93.3) | 64 (97.0) | — | |||

| Female | 70 (54.7) | 27 (48.2) | 39 (60.9) | — | |||

| Male | 58 (45.3) | 29 (51.8) | 25 (39.1) | — | |||

| Race | 128 (94.1) | 57 (95.0) | 64 (97.0) | — | |||

| White | 81 (63.3) | 33 (57.9) | 43 (67.2) | — | |||

| Non-White | 25 (19.5) | 13 (22.8) | 12 (18.8) | — | |||

| More than one race or unknown | 22 (17.2) | 11 (19.3) | 9 (14.1) | — | |||

| Ethnicity | 123 (90.4) | 55 (91.7) | 60 (90.9) | — | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (11.4) | 7 (12.7) | 7 (11.7) | — | |||

| Unknown | 7 (5.7) | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.3) | — | |||

| Education | 129 (94.9) | 57 (95.0) | 64 (97.0) | — | |||

| High school diploma or less, General equivalency diploma | 4 (3.1) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.1) | — | |||

| Some college, college, technical college | 87 (67.4) | 38 (66.7) | 45 (70.3) | — | |||

| Post-graduate | 38 (29.5) | 17 (29.8) | 17 (26.6) | — | |||

| Persons in household | 127 (93.4) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 58 (96.7) | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 62 (93.9) | 2.1 ± 1.1 | — |

| Poverty level | 129 (94.9) | 58 (96.7) | 63 (95.5) | — | |||

| Below poverty line | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | — | |||

| Maybe below poverty line | 13 (10.1) | 5 (8.6) | 8 (12.7) | — | |||

| Above poverty line | 95 (73.6) | 44 (75.9) | 44 (69.8) | — | |||

| Did not disclose | 20 (15.5) | 8 (13.8) | 11 (17.5) | — | |||

| Hospitalization | 136 (100) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | — | |||

| Did not go to the hospital | 27 (19.9) | 8 (13.3) | 18 (27.3) | — | |||

| Less than 24 hours | 38 (27.9) | 17 (28.3) | 16 (24.2) | — | |||

| Between 24 and 48 hours | 12 (8.8) | 2 (3.3) | 8 (12.1) | — | |||

| More than 48 hours | 59 (43.4) | 33 (55.0) | 24 (36.4) | — | |||

| Disposition | 113 (83.1) | 53 (88.3) | 51 (77.3) | — | |||

| Home | 91 (80.5) | 38 (71.7) | 44 (86.3) | — | |||

| In-patient rehabilitation | 20 (17.7) | 13 (24.5) | 7 (13.7) | — | |||

| Assisted living facility | 2 (1.8) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | — | |||

| Comorbiditiesa | |||||||

| Multiple TBIs | 134 (98.5) | 51 (38.1) | 59 (98.3) | 26 (44.1) | 66 (100) | 21 (31.8) | 0.17 |

| PTSD, psych | 132 (97.1) | 67 (50.8) | 59 (98.3) | 31 (52.5) | 66 (100) | 32 (48.5) | 0.65 |

| Addiction/substance use | 126 (92.6) | 10 (7.9) | 54 (90.0) | 4 (7.4) | 66 (100) | 6 (9.1) | 0.80 |

| Epilepsy/seizure | 129 (94.9) | 14 (10.9) | 56 (93.3) | 5 (8.9) | 66 (100) | 7 (10.6) | 1.00 |

| Stroke | 127 (93.4) | 7 (5.5) | 55 (91.7) | 4 (7.3) | 66 (100) | 3 (4.5) | 0.70 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 128 (94.1) | 0 (0) | 56 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 66 (100) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Parkinson’s | 126 (92.6) | 0 (0) | 55 (91.7) | 0 (0) | 65 (98.5) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Other neurological disorder | 130 (95.6) | 32 (24.6) | 57 (95.0) | 18 (31.6) | 66 (100) | 13 (19.7) | 0.12 |

| TBI-related symptomsa | |||||||

| Cognitionb | 132 (97.1) | 98 (74.2) | 59 (98.3) | 46 (78.0) | 65 (98.5) | 47 (72.3) | 0.47 |

| Balance disordersc | 131 (96.3) | 90 (68.7) | 59 (98.3) | 42 (71.2) | 65 (98.5) | 44 (67.7) | 0.67 |

| Sensory inputd | 130 (95.6) | 86 (66.2) | 58 (96.7) | 43 (74.1) | 66 (100) | 39 (59.1) | 0.08 |

| Headache | 128 (94.1) | 79 (61.7) | 56 (93.3) | 43 (76.8) | 65 (98.5) | 31 (47.7) | 0.001 |

| Fatigue | 131 (96.3) | 75 (57.3) | 59 (98.3) | 39 (66.1) | 65 (98.5) | 33 (50.8) | 0.08 |

| Irritability and temper | 131 (96.3) | 60 (45.8) | 58 (96.7) | 33 (56.9) | 65 (98.5) | 22 (33.8) | 0.01 |

| Anxiety | 130 (95.6) | 59 (45.4) | 59 (98.3) | 35 (59.3) | 65 (98.5) | 21 (32.3) | 0.003 |

| Sleep | 130 (95.6) | 56 (43.1) | 58 (96.7) | 26 (44.8) | 65 (98.5) | 25 (38.5) | 0.47 |

| Sexual difficulties | 127 (93.4) | 23 (18.1) | 56 (93.3) | 13 (23.2) | 64 (97.0) | 9 (14.1) | 0.20 |

Abbreviations: PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder. TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Respondents were able to select more than one choice.

Cognition includes memory and concentration.

Balance disorders include dizziness, problems with balance and/or problems with coordination.

Sensory input includes blurred vision, being bothered by noise, being bothered by light, problems with taste and/or problems with smell.

Acupuncture use means self-reported current or past acupuncture treatment. 126 out of 136 answered acupuncture history question (92.6 % response rate). Values presented are number (percentage of respondents) for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Significant p values (p<0.05) are indicated in bold font.

As shown in Table 1, similar responses between individuals who had a history of receiving acupuncture and those who did not were observed for gender, race, ethnicity, education level, number of persons in the household, poverty and hospital disposition. Respondents reporting an acupuncture history were approximately two years older than respondents reporting no acupuncture history (47.4 ± 13.7 vs. 45.2 ± 18.4 years old, respectively). More individuals with an acupuncture history had been hospitalized for >48 hours compared to those reporting no acupuncture use (55.0% vs. 36.4%, respectively). Compared to respondents without an acupuncture history, more respondents with an acupuncture history reported TBI-related symptoms of headache (76.8% vs. 47.7%, P=0.001), anxiety (59.3% vs. 32.3%, P=0.003), and irritability/temper (56.9% vs. 33.8%, P=0.01).

Among all 136 respondents reporting symptoms related to their TBI, most symptoms had appeared after the injury (Table 2), although a large proportion had pre-existing anxiety (49.2%), sleep issues (44.6%) and/or irritability (41.4%).

Table 2.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) symptom checklist (n=136)

| Symptom severitya | Symptom changesb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | Had Symptoms | Not a problem | Mild problem | Moderate problem | Severe problem | Present before last injury | Same | Better | Worse | |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Headache | 128 (94.1) | 79 (61.7) | 6 (7.6) | 28 (35.4) | 27 (34.2) | 18 (22.8) | 25 (31.6) | 7 (28.0) | 12 (48.0) | 6 (24.0) |

| Fatigue | 131 (96.3) | 75 (57.3) | 4 (5.3) | 26 (34.7) | 34 (45.3) | 11 (14.7) | 12 (16.0) | 5 (41.7) | 5 (41.7) | 2 (16.7) |

| Dizzinessc | 129 (94.9) | 72 (55.8) | 6 (8.3) | 45 (62.5) | 17 (23.6) | 3 (4.2) | 7 (9.7) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) |

| Blurred vision | 126 (92.6) | 40 (31.7) | 6 (15.0) | 23 (57.5) | 10 (25.0) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Concentration | 131 (96.3) | 82 (62.6) | 4 (4.9) | 29 (35.4) | 31 (37.8) | 18 (22.0) | 27 (32.9) | 8 (29.6) | 18 (66.7) | 1 (3.7) |

| Noise | 127 (93.4) | 59 (46.5) | 5 (8.5) | 13 (22.0) | 28 (47.5) | 13 (22.0) | 14 (23.7) | 2 (14.3) | 10 (71.4) | 2 (14.3) |

| Light | 127 (93.4) | 60 (47.2) | 2 (3.3) | 33 (55.0) | 15 (25.0) | 10 (16.7) | 13 (21.7) | 3 (23.1) | 7 (53.8) | 3 (23.1) |

| Irritability | 130 (95.6) | 58 (44.6) | 2 (3.4) | 28 (48.3) | 16 (27.6) | 12 (20.7) | 24 (41.4) | 6 (25.0) | 16 (66.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| Temper | 129 (94.9) | 39 (30.2) | 4 (10.3) | 20 (51.3) | 6 (15.4) | 9 (23.1) | 10 (25.6) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| Memory | 132 (97.1) | 84 (63.6) | 2 (2.4) | 28 (33.3) | 37 (44.0) | 17 (20.2) | 17 (20.2) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (58.8) | 1 (5.9) |

| Anxiety | 130 (95.6) | 59 (45.4) | 4 (6.8) | 18 (30.5) | 26 (44.1) | 11 (18.6) | 29 (49.2) | 10 (34.5) | 16 (55.2) | 3 (10.3) |

| Sleepc | 130 (95.6) | 56 (43.1) | 2 (3.6) | 18 (32.1) | 17 (30.4) | 18 (32.1) | 25 (44.6) | 11 (44.0) | 11 (44.0) | 3 (12.0) |

| Balance | 131 (96.3) | 67 (51.1) | 8 (11.9) | 34 (50.7) | 24 (35.8) | 1 (1.5) | 12 (17.9) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) |

| Sexual difficulties | 127 (93.4) | 23 (18.1) | 1 (4.3) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Coordination | 130 (95.6) | 52 (40.0) | 7 (13.5) | 26 (50.0) | 15 (28.8) | 4 (7.7) | 5 (9.6) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Taste | 126 (92.6) | 16 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (31.2) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (31.2) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Smell | 126 (92.6) | 21 (16.7) | 2 (9.5) | 7 (33.3) | 5 (23.8) | 7 (33.3) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) |

Values are for n (%) of respondents answering each question about the presence of symptoms for each item in the 17-item TBI symptom checklist.36,37

Values are for n (%) of respondents reporting the presence of each specific symptom from the 17-item TBI symptom checklist.36,37

Dizziness and sleep both had one respondent not complete the questions about symptom severity.

Values presented are number (percentage of respondents)

Prior acupuncture use

Table 3 details the self-reported use of acupuncture, including the frequency of and indications for treatment, for the 126 respondents who responded to the question. For those with a history of acupuncture, the frequency was most commonly weekly (48.3%), occurring primarily for health concerns (78.3%) but also for personal wellness (48.3%). Eighteen of 66 respondents with no history of acupuncture use (27.7%) reported that they were unlikely to receive acupuncture because of a lack of knowledge about it.

Table 3.

Acupuncture experience including frequency of and reasons for treatment

| Responses n (%) | Value n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| History of acupuncture (n = 60) | ||

| Frequency of treatment | 60 (100) | |

| Only one time | 9 (15.0) | |

| A few times per year | 7 (11.7) | |

| Once a month | 11 (18.3) | |

| Every week | 29 (48.3) | |

| More than once weekly | 4 (6.7) | |

| Reasons | ||

| Health concerns | 60 (100) | 47 (78.3) |

| Personal wellness | 60 (100) | 29 (48.3) |

| Health concerns (n=45) | 45 (75.0) | |

| Musculoskeletal complaints | 19 (42.2) | |

| Neurologic complaints | 11 (24.4) | |

| Other | 14 (31.1) | |

| Personal wellness (n=29) | 29 (48.3) | |

| Physical wellness | 28 (96.6) | |

| Mental wellness | 12 (41.4) | |

| Spiritual wellness | 7 (24.1) | |

| Overall health maintenance | 19 (65.5) | |

| No history of acupuncture (n = 66) | ||

| Unlikely to get because of a lack of knowledge | 65 (98.5) | 18 (27.7) |

126 out of 136 answered acupuncture history question (92.6% response rate). Values presented are numbers (percentage of respondents).

Acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs

Table 4 displays the acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs items for the 126 individuals providing a response to the acupuncture history question.

Table 4.

Responses to acupuncture knowledge, attitudes and beliefs questions, and data completeness

| Study sample (n=136) |

Acupuncture use (n=60) |

No acupuncture use (n=66) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses n (%) | Value n (%) | Responses n (%) | Value n (%) | Responses n (%) | Value n (%) | P | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Acupuncture knowledge | |||||||

| A medical treatment from traditional Chinese medicine | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.001 | |||

| Correct | 117 (87.3) | 58 (96.7) | 51 (77.3) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 17 (12.7) | 2 (3.3) | 15 (22.7) | ||||

| Inserts needles through the skin | 133 (97.8) | 59 (98.3) | 66 (100) | 1.0 | |||

| Correct | 129 (97.0) | 57 (96.6) | 64 (97.0) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 4 (3.0) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Treats more than pain | 133 (97.8) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.01 | |||

| Correct | 106 (79.1) | 53 (88.3) | 46 (69.7) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 28 (20.9) | 7 (11.7) | 20 (30.3) | ||||

| Use for overall wellness | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.002 | |||

| Correct | 96 (72.2) | 51 (85.0) | 40 (60.6) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 37 (27.8) | 9 (15.0) | 26 (39.4) | ||||

| Manages medical symptoms | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.85 | |||

| Correct | 87 (64.9) | 41 (68.3) | 40 (60.6) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 47 (35.1) | 19 (31.7) | 26 (39.4) | ||||

| Does not use medicine on the needles | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.004 | |||

| Correct | 93 (69.4) | 48 (80.0) | 37 (56.1) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 41 (30.6) | 12 (20.0) | 29 (43.9) | ||||

| Uses single-use needles | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Correct | 90 (67.2) | 50 (83.3) | 34 (51.5) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 44 (32.8) | 10 (16.7) | 32 (48.5) | ||||

| Does not have many side-effects | 133 (97.8) | 59 (98.3) | 66 (100) | 0.02 | |||

| Correct | 82 (61.7) | 42 (71.2) | 33 (50.0) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 51 (38.3) | 17 (28.8) | 33 (50.0) | ||||

| Multiple treatments are usually needed | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Correct | 59 (44.0) | 36 (60.0) | 19 (28.8) | ||||

| Incorrect/DNKEa | 75 (56.0) | 24 (40.0) | 47 (71.2) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Acupuncture attitudes | |||||||

| Talk to HCP about getting | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.1 | |||

| Likely | 85 (63.4) | 42 (70.0) | 37 (56.1) | ||||

| Unlikely | 46 (34.3) | 18 (30.0) | 26 (39.4) | ||||

| DNKE | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.5) | ||||

| Get with insurance | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.1 | |||

| Likely | 117 (87.3) | 56 (93.3) | 54 (81.8) | ||||

| Unlikely | 14 (10.4) | 4 (6.7) | 10 (15.2) | ||||

| DNKE | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Get with no insurance | 132 (97.1) | 60 (100) | 64 (97.0) | 0.001 | |||

| Likely | 59 (44.7) | 36 (60.0) | 20 (31.3) | ||||

| Unlikely | 67 (50.8) | 24 (40.0) | 39 (60.9) | ||||

| DNKE | 6 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.8) | ||||

| Tell HCP if receiving | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.15 | |||

| Likely | 120 (89.6) | 52 (86.7) | 60 (90.9) | ||||

| Unlikely | 12 (9.0) | 8 (13.3) | 4 (6.1) | ||||

| DNKE | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Use at same time as regular treatments | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.36 | |||

| Likely | 108 (80.6) | 51 (85.0) | 50 (75.8) | ||||

| Unlikely | 18 (13.4) | 7 (11.7) | 10 (15.2) | ||||

| DNKE | 8 (6.0) | 2 (3.3) | 6 (9.1) | ||||

| Get before seeing HCP if sick | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Likely | 26 (19.4) | 16 (26.7) | 5 (7.6) | ||||

| Unlikely | 97 (72.4) | 44 (73.3) | 50 (75.8) | ||||

| DNKE | 11 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (16.7) | ||||

| Get with a serious health condition | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Likely | 72 (53.7) | 38 (63.3) | 28 (42.4) | ||||

| Unlikely | 47 (35.1) | 21 (35.0) | 24 (36.4) | ||||

| DNKE | 15 (11.2) | 1 (1.7) | 14 (21.2) | ||||

| Stop if asked by HCP to quit, even if feeling better | 132 (97.1) | 60 (100) | 64 (97.0) | 0.01 | |||

| Likely | 52 (39.4) | 22 (36.7) | 29 (45.3) | ||||

| Unlikely | 69 (52.3) | 37 (61.7) | 26 (40.6) | ||||

| DNKE | 11 (8.3) | 1 (1.7) | 9 (14.1) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Acupuncture beliefs | |||||||

| Must believe in acupuncture for it to work | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | .004 | |||

| Agree | 22 (16.4) | 10 (16.7) | 11 (16.7) | ||||

| Disagree | 94 (70.1) | 48 (80.0) | 40 (60.6) | ||||

| DNKE | 18 (13.4) | 2 (3.3) | 15 (22.7) | ||||

| Have improved outcomes if combined with conventional treatment | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Agree | 84 (62.7) | 46 (76.7) | 32 (48.5) | ||||

| Disagree | 18 (13.4) | 10 (16.7) | 8 (12.1) | ||||

| DNKE | 32 (23.9) | 4 (6.7) | 26 (39.4) | ||||

| Should not use concurrently with conventional treatment | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.002 | |||

| Agree | 4 (3.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

| Disagree | 96 (71.6) | 51 (85.0) | 39 (59.1) | ||||

| DNKE | 34 (25.4) | 8 (13.3) | 25 (37.9) | ||||

| Limited benefits for a serious medical condition | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | <0.001 | |||

| Agree | 12 (9.0) | 3 (5.0) | 8 (12.1) | ||||

| Disagree | 83 (61.9) | 47 (78.3) | 30 (45.5) | ||||

| DNKE | 39 (29.1) | 10 (16.7) | 28 (42.4) | ||||

| Hesitant to have because of a lack of evidence | 133 (97.8) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.003 | |||

| Agree | 19 (14.3) | 4 (6.7) | 14 (21.2) | ||||

| Disagree | 102 (76.7) | 55 (91.7) | 41 (62.1) | ||||

| DNKE | 12 (9.0) | 1 (1.7) | 11 (16.7) | ||||

| Requires a religious belief | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.25 | |||

| Agree | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Disagree | 130 (97.0) | 60 (100) | 63 (95.5) | ||||

| DNKE | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.5) | ||||

| Should only be used when feeling well | 134 (98.5) | 60 (100) | 66 (100) | 0.26 | |||

| Agree | 6 (4.5) | 3 (5.0) | 3 (4.5) | ||||

| Disagree | 115 (85.8) | 54 (90.0) | 54 (81.8) | ||||

| DNKE | 13 (9.7) | 3 (5.0) | 9 (13.6) | ||||

Acupuncture use means self-reported current or past acupuncture treatment. 126 out of 136 answered acupuncture history question (92.6% response rate). Values number (percentage of respondents). P-values are for comparison between the two groups reporting a history of acupuncture or no history of acupuncture. Significant p values (p<0.05) are indicated in bold font.

Abbreviations: DKNE, “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer”; HCP, healthcare provider.

Incorrect category includes responses for “do not know enough about acupuncture to answer.”

When comparing respondents reporting a history of acupuncture to respondents without an acupuncture history, respondents with a history of acupuncture had higher levels of knowledge about the connection of acupuncture to Traditional Chinese Medicine (96.7% correct), about needle use (80.0% correct), safety (83.3% correct), side-effects (71.2% correct), the fact that most medical conditions require multiple treatments (60.0% correct) and usual indications for treatment (three questions, mean 80.5% correct).

Most respondents indicated they would communicate with their healthcare provider about acupuncture, get acupuncture if there were insurance coverage, and receive acupuncture concurrently with allopathic treatments. When comparing respondents reporting a history of acupuncture to respondents without an acupuncture history, respondents with an acupuncture history felt more favorably about acupuncture, responding they would be more likely to get it in the absence of insurance coverage (60.0% vs. 31.3%, P=0.001), before seeing a health care provider if sick (26.7% vs. 7.6%, P<0.001) and if they had a concerning health condition (63.3% vs. 42.4%, P<0.001). Additionally, respondents with an acupuncture history more often reported that they would be unlikely to stop acupuncture therapy at the recommendation of their doctor (61.7% vs. 40.6%, P=0.01).

Beliefs about acupuncture varied widely over the survey sample. A majority of respondents, however, felt that acupuncture has health benefits and disagreed its use required specific personal or religious beliefs. When comparing respondents reporting a history of acupuncture to respondents without an acupuncture history, respondents with a history of acupuncture were more open to the idea of using it as a medical therapy, including in combination with conventional allopathic therapies, when sick, or even if there is a lack of evidence for its use.

Weekly acupuncture

The 136 respondents in our study sample reported a broad spectrum of requirements to participate in weekly acupuncture (Table 5). Respondents generally had transportation (87.8%). There was wide distribution in travel time one-way, but over half (55.4%) of respondents indicated willingness to travel more than 30 minutes. Over half (61.2%) of respondents would be willing to receive acupuncture in one room where others are receiving acupuncture concurrently, and a majority (97.7%) would be willing to receive acupuncture in a private room. Over three-quarters (84.3%) of respondents were willing to participate in acupuncture for at least 12 weeks, and 53.5% of the respondents were willing to participate in weekly acupuncture up to 12 months. However, there was wide variability in how long respondents would participate in weekly sessions if they had not felt improvement, with 32.0% reporting they would stop before 12 weeks. Notably, respondents reported that they would need to see, on average, a 45.6% improvement in their symptoms to keep going weekly and expected an overall 49.9% improvement in symptoms by participating.

Table 5.

Ability of respondents to attend weekly acupuncture treatments (n=136)

| Responses n (%) |

Value | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Has transportation | 131 (96.3) | 115 (87.8) |

| Travel time one-way | 130 (95.6) | |

| < 15 minutes | 13 (10.0) | |

| 16–30 minutes | 45 (34.6) | |

| 31– 45 minutes | 26 (20.0) | |

| > 45 minutes | 46 (35.4) | |

| Would be treated in one room where other individuals are also receiving treatments at the same time | 129 (94.9) | 79 (61.2) |

| Would be treated in a private room alone | 131 (96.3) | 128 (97.7) |

| Willingness to attend: duration with improvement | 127 (93.4) | |

| 4 weeks | 9 (7.1) | |

| 6 weeks | 3 (2.4) | |

| 2 months | 8 (6.3) | |

| 3 months | 11 (8.7) | |

| 4 months | 9 (7.1) | |

| 6 months | 16 (12.6) | |

| 9 months | 3 (2.4) | |

| 12 months | 68 (53.5) | |

| Willingness to attend: duration with no improvement | 128 (94.1) | |

| 4 weeks | 16 (12.5) | |

| 6 weeks | 13 (10.2) | |

| 2 months | 12 (9.4) | |

| 3 months | 21 (16.4) | |

| 4 months | 12 (9.4) | |

| 6 months | 23 (18.0) | |

| 9 months | 2 (1.6) | |

| 12 months | 29 (22.7) | |

| Degree of improvement to keep attending (mean, SD) | 125 (91.9) | 45.6 (24.8) |

| Degree of expected overall (mean, SD) | 123 (90.4) | 49.9 (23.6) |

Values are presented as number and percent of response rate for categorical variables, and the mean, standard deviation for continuous variables where noted.

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of this study was to characterize knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acupuncture, and assess health service needs in people following a TBI. Overall, this study found that individuals with a prior history of TBI had moderate levels of preexisting knowledge about acupuncture, were receptive to receiving the therapy, and were open to discussing its use with their health care provider. We also found that individuals with TBI and a prior history of acupuncture had greater knowledge and more positive attitudes and beliefs towards acupuncture. These data provide new information regarding acceptability and feasibility of acupuncture use in individuals with TBI, and indicate that patients are willing and able to participate in an acupuncture study to address post-TBI symptoms.

Results of this study indicate that respondents felt that lack of insurance coverage was a significant barrier to acupuncture use, with no insurance benefits accounting for an almost 50% reduction in willingness to participate in acupuncture post-TBI. While this reduction was not as significant among respondents with prior acupuncture use, lack of insurance coverage is likely a barrier for integration of acupuncture therapy in the United States, as it is common for individuals to self-pay.17,39 Most chronic conditions require many weeks of acupuncture for sustained therapeutic benefits, and most respondents did not know that multiple acupuncture treatments are typically necessary to establish a full therapeutic benefit. The median cost to a patient ranges from $45 to $150 USD per acupuncture treatment in the absence of insurance coverage.40 Given the large TBI burden resulting in substantial financial challenges,41 the cost of acupuncture for the uninsured is prohibitive, even though acupuncture is desired and may be associated with symptom relief post-TBI. Added to this are the costs of time for missed work, transportation and/or caregiver costs. The lack of insurance coverage is likely to prohibit many people with TBI with limited resources from accessing acupuncture, and the lack of access to acupuncture treatment may therefore represent an equity challenge for individuals with TBI.

These results further suggest acupuncture is not only acceptable to individuals with TBI but that referral for acupuncture by their healthcare providers might translate into greater utilization. Collectively, we posit formal research should be conducted in individuals with TBI to examine the utility of acupuncture. Collaboration between acupuncturists and traditional allopathic health care providers would be a means to facilitate the study of acupuncture in TBI recovery, including in the management of ongoing post-TBI symptoms. Additionally, use of acupuncture varies significantly among different regions within the United States, with the greatest use found in the Western regions and the lowest in the Southern regions.11 These results provide an opportunity for education of healthcare providers in regions where the use of acupuncture is low.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this research are its novel focus, assessment of feasibility, acceptability, barriers and facilitators, and detailed characterization of the study sample, including symptoms of individuals with TBI, all of which will inform future research. Limitations include the cross-sectional design and convenience sampling, as well as underrepresentation of non-Whites and Hispanics, which limits generalizability. Data from a recent article using Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) survey data from 2010 to 2019 indicates that most acupuncture users in the United States are White.17 As such, acupuncture use and distinct knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acupuncture are likely to vary in other ethnic and racial groups, so the frequency of acupuncture use across racial and ethnic groups with TBI merits future study. Another limitation is that we do not have information on the military service member status of the respondents. Clinical characteristics of TBI in military service members might present differently than individuals who are not military service members. As such, we are unable to draw any conclusions based on military service status. We are also unable to draw any conclusions based on the length of time since injury. A large proportion of respondents reported having had multiple TBIs, and we do not know from our data when each TBI occurred. It is possible that, for some respondents, the initial or early injuries occurred prior to the implementation of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 coding system. Lastly, ten respondents did not answer the acupuncture use question, and it is possible this exclusion may have biased our results in making comparisons between respondents who reported acupuncture use and respondents who did not report acupuncture use.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that individuals with TBI are receptive to and able to utilize acupuncture, and many are already receiving it. Patients with TBI should be informed that acupuncture typically requires multiple treatments over many weeks to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit. Future research should examine the effectiveness of acupuncture on various clinical sequelae post-injury in individuals with TBI, especially for symptoms that are common after TBI, such as cognition, balance disorders, impaired sensory input and headache.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington School of Nursing and University of Washington School of Medicine for their support of the work.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under a National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) supplement to the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) KL2 award TR002317 (MDS), under grants from the NIH under a NCCIH R01AT010598 (JAD), and under grants from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 5R49CE003087-03 (MSV). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Institute of Translational Health Sciences (ITHS). REDCap at ITHS was supported by NCATS (award no. UL1TR002319, KL2 TR002317 and TL1 TR002318). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

COMPETING INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2006. pp. 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury–related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths — United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017; 66(9): 1–16. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thurman DJ, Alverson C, Dunn KA, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: a public health perspective. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1999; 14(6): 602–615. DOI: 10.1097/00001199-199912000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Langlois JA, et al. Prevalence of long-term disability from traumatic brain injury in the civilian population of the United States, 2005. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2008; 23(6): 394–400. DOI: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000341435.52004.ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucke-Wold BP, Smith KE, Nguyen L, et al. Sleep disruption and the sequelae associated with traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015; 55: 68–77. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucke-Wold BP, Logsdon AF, Nguyen L, et al. Supplements, nutrition, and alternative therapies for the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Nutr Neurosci 2018; 21(2): 79–91. DOI: 10.1080/1028415X.2016.1236174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes PM, Bloom B and Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007: National Health Statistics Reports; no 12. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, et al. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med 2006; 12(7): 639–648. DOI: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National Health Statistics Reports; no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin S, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Qu H, et al. Acupuncture use in the United States: who, where, why, and at what price? Health Mark Q 2015; 32(2): 113–128. DOI: 10.1080/07359683.2015.1033929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao T, Li Q, DeRito JL, et al. Barriers to acupuncture use among breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional analysis. Integr Cancer Ther 2018; 17(3): 854–859. DOI: 10.1177/1534735418754309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadeghi R, Heidarnia MA, Tafreshi MZ, et al. The reasons for using acupuncture for pain relief. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014; 16(9): e15435. DOI: 10.5812/ircmj.15435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sodders MD, Osborn MP and Vavilala MS. Student knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about acupuncture: an exploratory study. Acupunct Med 2021; 39(6): 718–720. DOI: 10.1177/09645284211009904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stumpf SH, Hardy ML, McCuaig S, et al. Acupuncture practice acts: a profession's growing pains. Explore (NY) 2015; 11(3): 217–221. DOI: 10.1016/j.explore.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candon M, Nielsen A and Dusek JA. Trends in insurance coverage for acupuncture, 2010–2019. JAMA Network Open 2022; 5(1): e2142509. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin S-J, Cao L-X, Cheng S-B, et al. Effect of acupuncture on the TLR2/4-NF- κB signalling pathway in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Acupunct Med 2018; 36(4): 247–253. DOI: 10.1136/acupmed-2017-011472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang W-C, Hsu Y-C, Wang C-C, et al. Early electroacupuncture treatment ameliorates neuroinflammation in rats with traumatic brain injury. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016; 16: 470. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-016-1457-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu MM, Lin JH, Qing P, et al. Manual acupuncture relieves microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury by inhibiting the RhoA/ROCK2 pathway. Acupunct Med 2020; 38(6): 426–434. DOI: 10.1177/0964528420912248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Chen C, Yang X, et al. Acupuncture improved neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury by activating BDNF/TrkB pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2017; 2017: 8460145. DOI: 10.1155/2017/8460145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Chuang CH, Hsu YC, Wang CC, et al. Cerebral blood flow and apoptosis-associated factor with electroacupuncture in a traumatic brain injury rat model. Acupunct Med 2013; 31(4): 395–403. DOI: 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang S, Chen W, Zhang Y, et al. Acupuncture induces the proliferation and differentiation of endogenous neural stem cells in rats with traumatic brain injury. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016; 2016: 2047412. DOI: 10.1155/2016/2047412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhang Y-M, Chen S-X, Dai Q-F, et al. Effect of acupuncture on the Notch signaling pathway in rats with brain injury. Chin J Integr Med 2018; 24(7): 537–544. DOI: 10.1007/s11655-015-1969-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y-M, Dai Q-F, Chen W-H, et al. Effects of acupuncture on cortical expression of Wnt3a, β-catenin and Sox2 in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Acupunct Med 2016; 34(1): 48–54. DOI: 10.1136/acupmed-2014-010742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y-M, Zhang Y-Q, Cheng S-B, et al. Effect of acupuncture on proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells in brain tissues of rats with traumatic brain injury. Chin J Integr Med 2013; 19(2): 132–136. DOI: 10.1007/s11655-013-1353-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacPherson H, Vickers A, Bland M, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain and depression in primary care: a programme of research. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacPherson H, Richmond S, Bland M, et al. Acupuncture and counselling for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2013; 10(9): e1001518. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CA, Armour M, Lee MS, et al. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; (3): CD004046. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia Y, Zhang X, Yu J, et al. Acupuncture for patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017; 17: 556. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-017-2064-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong T, Pei C, Chen J, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture therapy for chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients. Med Sci Monit 2018; 24: 2919–2927. DOI: 10.12659/MSM.909712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Yang H, Zhang J, et al. Efficacy and safety assessment of acupuncture and nimodipine to treat mild cognitive impairment after cerebral infarction: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016; 16: 361. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-016-1337-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care 2002; 40(9): 771–781. DOI: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000024610.33213.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42(2): 377–381. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 1932; 22(140): 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLean A Jr., Dikmen S, Temkin N, et al. Psychosocial functioning at 1 month after head injury. Neurosurgery 1984; 14(4): 393–399. DOI: 10.1227/00006123-198404000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson HJ, Rivara FP and Wang J. Effect of age on longitudinal changes in symptoms, function, and outcome in the first year after mild-moderate traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Nurs 2020; 52(2): 46–52. DOI: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nahin RL, Barnes PM and Stussman BJ. Insurance coverage for complementary health approaches among adult users: United States, 2002 and 2012. NCHS data brief, no 235. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan AY, Wang DD, Ouyang H, et al. Acupuncture price in forty-one metropolitan regions in the United States: an out-of-pocket cost analysis based on OkCopay.Com. J Integr Med 2019; 17(5): 315–320. DOI: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma VY, Chan L and Carruthers KJ. Incidence, prevalence, costs, and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the United States: stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95(5): 986–995. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]