Abstract

Background

Chronic diseases pose significant threats to persons’ well-being and mental health leading to stress, anxiety and depression without effective resilience strategies. However, experiences to gain resilience in living with chronic disease in the context of Asian countries remain insufficiently explored. This review seeks to provide a comprehensive summary of qualitative evidence that explores the lived experience that cultivates resilience in chronic diseases among adults within Asian countries.

Methods

A comprehensive review of five databases - Web of Sciences, Ebsco (Medline), PubMed, Science Direct, and Scopus was carried out, following the Joanna Brings Institute (JBI) standards and employing PRISMA Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guideline. The review encompassed studies published in English from January 2013 to December 2023. Four reviewers assessed the literature’s eligibility and extracted relevant lived experiences to address the research question based on prior studies. Subsequently, a content analysis was performed.

Results

Of the 3651 articles screened, 12 were included in this review. Three key themes emerged: (1) Sociocultural norms shaped resilience, delved into the culturally-mediated childhood development, traditional cultural beliefs, social relationships and supports and spirituality (2) Positive emotions nurtured resilience highlighted optimistic about becoming healthy, self-efficacy in self-care, endurance during hardship, self-reflection on health, acceptance of having disease, and appreciation of life while (3) Problem-solving strategies fostered resilience underlined improve disease literacy, ability to deal with disease challenges and engage in meaningful activities.

Conclusion

Our review addresses important research gaps on sociocultural norms that shaped resilience in chronic disease despite a small number of research. Therefore, this warrants further studies on how the traditional cultures and beliefs influence resilience among the Asian population living with chronic disease. Further research should thoroughly describe the qualitative methodologies and theoretical framework to provide more comprehensive information on the experience of resilience in chronic disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-024-02296-2.

Keywords: Lived experience, Resilience, Chronic disease, Sociocultural

Background

Chronic disease or non-communicable disease (NCD) is defined broadly as conditions that last one year or more and require ongoing medical attention or limit activities of daily living or both [1]. Annually, the most common NCD deaths are cardiovascular diseases, or 17.9 million people, followed by cancers (9.3 million), chronic respiratory diseases (4.1 million), and diabetes (2.0 million, including kidney disease deaths caused by diabetes) [2]. Chronic disease poses a detrimental effect on a patient’s psychological, physical health, and financial stability, resulting in stress, anxiety and depression [3]. Depression was found to have a negative correlation with resilience [4, 5]. Resilience is the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and behavioural flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands [6] and is one of the essential elements in preventing mental health problems. Specifically, in the context of chronic disease, resilience is defined as the ability to maintain healthy levels of function over time despite adversity or to return to normal function after adversity [7]. Self-care, adherence to treatment programs, health-related quality of life, illness perceptions, self-empowerment, optimism and social support were among the factors that promoted resilience in chronic disease [8]. Despite the numerous personal and environmental support, resilience in self-care remains a substantial challenge for researchers, clinicians, and individuals living with chronic diseases. Research on lived experience explores the fundamental meanings of a phenomenon from the perspective of the individual who lives with it [9]. Exploring the lived experience of maintaining resilience in adults with chronic diseases offers valuable insights into patients’ perspectives on molding resilience, which may diverge from those of healthcare providers and researchers.

Asian populations have distinct social, cultural, and life values which may be different from their Western counterparts [10] and may likely influence their implications for being resilient. Therefore, understanding patients’ sociocultural contexts is vital to developing a holistic approach and guiding the development of interventions tailored to their unique needs.

The study of resilience in NCDs has been assessed especially in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cancers [11–19]. Seven.

Seven systematic reviews have explored resilience in chronic disease in the context of factors associated with resilience [8], resilience definition [6], the influence of resilience in progress illness and health outcome [47], resilience scores [20], resilience intervention [21], the relationship between resilience and self-care [22], and theoretical models, measures, and outcomes of resilience in older adults with multimorbidity [23]. Despite the extensive international research, no previous review has been done on the lived experience of resilience in managing chronic disease within the Asian population context Therefore, this review aims to map the literature and summarise the qualitative evidence that explores the the experiences of gaining resilience in managing health among adults living with chronic disease in Asian countries.

Methods

This scoping review utilizes the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) approach [24, 25]. The JBI guidance for conducting scoping reviews is outlined in one of the chapters in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis published by the JBI Collaboration [25]. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (the PRISMA-ScR) as the reporting guideline [26]. The review protocol was preregistered at the Open Science Framework (OSF) website (10.17605/OSF.IO/WPZ4E). Ethical approval was not required for this review.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were applied according to population, concept and context (PCC) monomeric to identify the central concept in the preliminary review and refine the search strategy.

Population

Adults aged 18 years and above with one or more chronic diseases were included in the review. We included the common NCDs related to resilience study which are DM, hypertension, CAD, HF, COPD, CKD, stroke, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and cancer. We excluded congenital diseases and psychiatric diseases. Congenital diseases were excluded because the development of resilience in individuals born with the disease may differ significantly from those who acquire a chronic disease later in life, and psychiatric diseases were omitted, as they may independently influence the capacity for resilience.

Concept

The review included studies that explored the lived experiences of participants’ resilience and ability to overcome the difficulties in living with chronic disease, including the participants’ factors that shaped resilience in chronic disease, participants’ emotional responses that nurtured resilience and participants’ adaptive skills to gain resilience while living with chronic disease.

Context

The review included studies conducted in Asian countries as listed in the United Nations Statistic Division (Appendix I). We included studies conducted in primary care or hospital settings with English full text. Studies in other languages were excluded Studies in other languages were excluded to ensure the information we extracted was precise since the authors were not proficient in certain languages and had limited resources to spend on the translation process.

Types of evidence sources

Our review encompassed all qualitative research articles, including but not limited to phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, action research, and feminist research. Notably, review articles were excluded, but the reference lists were assessed for eligible studies. Master’s or PhD theses were included. Findings from mixed-method studies were also incorporated, provided the qualitative data could be separated.

Systematic search and selection process

We performed an initial search using on PubMed database using the keywords “lived experience”, “resilience”, “chronic disease” and “Asia* countries”. We analyzed the titles and abstracts and the index terms used to describe the articles and refined our search keywords based on these findings. Next, a second search was executed across subject and citation databases: PubMed, Ebsco (MEDLINE), Science Direct, Web of Science, and Scopus, using all the identified keywords and index terms. The keywords were divided into four index terms: lived experience, resilience, chronic disease and Asian countries (Appendix II). We opted not to conduct a grey literature search because websites containing experiences (personal blogs, narratives etc.) can be extensive and lack scholarly relevance.

We included all articles published from January 2013 until December 2023. Identified articles were imported into EndNote and checked for duplicates. The search process was done on January 1st 2024 and was completed on January 25th 2024 with assistance from a subject expert librarian. Identified articles were exported into Endnote (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA), and checked for duplicates before being transferred into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) to continue the screening process. Finally, we evaluated the reference list of the identified articles for possible eligible studies.

Data collection and extraction

Two reviewers (MMZ and a second reviewer either RAR or RDM) independently conducted the title and abstract screening to determine eligibility. If there was any doubt about eligibility, the articles were included for further full-text review. Any disagreement was resolved through discussions with a third reviewer (AAK). The assessment of methodological appraisal and risk of bias was not performed in line with the JBI guidelines [24].

Data from selected studies were extracted and charted in data extraction form: author, year of publication, country, objectives, populations, theoretical framework methodology, and lived experiences with resilience. Data extraction included specific details for population, concept, context, and findings relevant to the review objectives. We utilised an inductive coding approach to identify data on the concept of lived experience with resilience [27]. We reviewed thoroughly the original studies multiple times to familiarize ourselves with the data. MMZ would refer back to the full text for further clarification during the coding of qualitative data when required. A descriptive qualitative content analysis was used to categorise the findings into a coding framework [28]. Data summaries and the coding themes were discussed, agreed upon among all co-authors and revised appropriately.

Results

Identification of studies

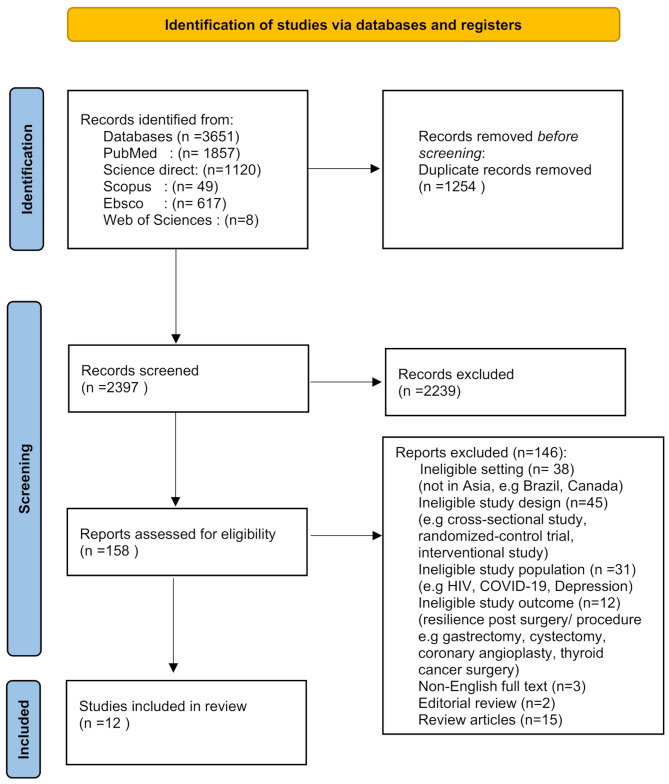

A total of 3651 papers were found and 12 were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the article selection process (PRISMA-ScR diagram 2000)

Characteristics of included studies

The articles were published between 2017 and 2023, representing five studies conducted in Southeast Asia, three from Eastern, three from Southern, and one from Western Asian regions (Table 1). Six studies employed a phenomenological approach, two studies were described as “qualitative studies” without mentioning the specific qualitative approach, two studies employed grounded theory, and one study employed a descriptive approach and a case study approach respectively. The studies involved participants aged 24 to 82 years. There were 150 participants in all 12 studies. The target participants were six studies among cancer patients, two studies in DM, one study among CKD, IBD and RA respectively and one study among the elderly with underlying chronic diseases not specified.

Table 1.

Summary of the included articles. (n = 12)

| No | 1st author, Year | Country (Asia region) | Aim of study | Qualitative approach | Underlying theory or framework | Population description | Number of participants | Data collection methods | Data analysis approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Hassani et al.; 2017 [29] |

Iran | To understand the meaning of resilience for hospitalized older people who experience chronic conditions. | A qualitative descriptive phenomenological approach. | Not mentioned |

Purposive sampling of hospitalised patients aged at least 65 years, having at least one chronic disease diagnosed by a specialist physician, willingness to express feelings pertinent to the subject of the study, ability to express rich experiences, and no psychological and cognitive disorders. |

22 elderly with at least one chronic disease ( 10 males, 12 females) |

In-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews. | Collaizzi’s analysis method |

| 2 |

Oruc et al.; 2023 [30] |

Turkey | To develop an explanatory framework to gain a deeper understanding of the resilience process in women diagnosed with gynecological cancers. | A qualitative grounded theory approach. | Salutogene-sis Model | A combination of purposeful and theoretical sampling of patients diagnosed with gynecological cancer and had to (1) know the diagnosis, (2) have stage 2–3 gynecological cancer, and (3) volunteer to participate in the study. | 20 women with gynecological cancer. | In-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews. | Open, axial, selective coding, and constant comparative methods. |

| 3 |

Kusnanto et al.; 2020 [31] |

Indonesia | To explore diabetes resilience among adults with regulated T2DM. | A qualitative case study approach. | Not mentioned |

Snowball sampling of patients aged 24–65 years old, -diagnosed with T2DM at least 5 years, plasma glucose of < 200 mg/dL -no recurrent foot ulcer, actively healthy lifestyle, able to do self-care, able to overcome adversity, endure and achieve a better life through adherence to medication and diet. |

15 patients with T2DM, (7 males, 8 females) |

In-depth interview | Thematic analysis |

| 4 |

Arifin et al.; 2020 [32] |

Indonesia | To know what adult type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) felt before becoming resilient. | A qualitative phenomenological design. | Not mentioned | Snowball sampling of patients aged 24–65 years old, diagnosed T2DM at least 5 years, -with resilience condition(controlled blood sugar, good diet management, medicine, and activity) |

10 patients with T2DM, (4 males, 6 females) |

Semi-structured, and face-to-face interviews. | Thematic analysis |

| 5 |

Pradila et al.; 2021 [33] |

Indonesia |

1. To investigate the emotional perception of patients in coping with this phenomenon 2. To explain the resilience of elderly patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis. |

A qualitative phenomenological design. | Not mentioned | Snowball sampling of patients age > 60 years old, male, married, chronic kidney disease (CKD) who have been on hemodialysis for more than one year, and adhere to hemodialysis. | Three male CKD patients. | In-depth, semi-structured interviews | Not specified |

| 6 |

Nordin et al.; 2022 [34] |

Malaysia | To explore the experiences of women with breast cancer and the role that resilience plays in their coping with it. | A qualitative phenomenological approach | Not mentioned |

Purposive sampling of Malaysian females, aged 18 years or older and diagnosed with breast cancer by a medical professional within the last five years. |

18 women with breast cancer | In-depth, semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| 7 |

Samsuri et al.; 2022 [35] |

Malaysia | To examines the experiences faced by employed female cancer survivors when developing resilience. | A qualitative phenomenological approach | Wheel of Wellness, Model of Resilience, and Stages of Resilience | Snowball sampling of (1) cancer-surviving employed women who have returned to work but are continuing with treatment, (2) have endured an operation, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or medication, (3) diagnosis and prognosis must be at least five years prior to being pronounced as survivors. | 10 employed women of breast cancer survivor | In-depth, semi-structured interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| 8 |

Zhang et al.; 2018 [36] |

China | To investigate resilience factors that helped Chinese breast cancer patients adapt to the trauma in the traditional Chinese cultural context | A qualitative research design (Approach not specified) | The social ecosystem theory. |

Purposive sampling of participants (1) ≥ 18 years of age, (2) diagnosis of breast cancer has lasted more than one month, (3) scored at least 64 points on the Chinese version of the Resilience Scale (RS-14), (4) lack of psychotic episode, (5) agreement to participation in the interview and complete the recording of talks. |

15 Chinese breast cancer patients | Checklist-guided interviews | Content analysis |

| 9 | Luo et al.; 2019 [37] | China |

To understand the resilience experiences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and develop a resilience framework. |

A qualitative descriptive approach. | Kumpfer’s resilience framework |

The maximum variation sampling approach- to select participants purposely who are varied in age, gender, course of the disease, marital status, and working conditions to gain diverse resilience experiences. |

15 patients with IBD (8 males, 7 females) | Semi-structured interviews | Content analysis |

| 10 | Chou et al.; 2023 [38] | Taiwan | To explore the process of resilience in individuals with colorectal cancer. | A qualitative study (Modified grounded theory) | Not mentioned | A purposive sampling strategy of individuals diagnosed with stage I to III CRC within the last five years, > 20 years of age, and able to communicate in Mandarin. Individuals with stage IV CRC, recurrent CRC or more than one cancer diagnosis were excluded. |

16 patients with CRC ( 11 males, 5 females) |

In-depth, semi-structured interviews | Modified grounded theory analysis |

| 11 | Chavare et al.; 2020 [39] | India | (1) To explore the process of resilience through the lived experiences of patients. (2) To investigate the way resilience influences health outcomes. | A qualitative study (Approach not specified) | Not mentioned |

(Sampling method not specified) (i) Patients having a diagnosis for a minimum six months (ii) Absence of terminal disease iii) Absence of psychiatric disease and any pharmacological treatment for psychiatric disease. |

8 women with RA. | In-depth, semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| 12 | Walton et al.; 2022 [40] | India |

1. To identify common protective resilient factors that enabled the adult female cancer survivors to cope with the cancer experience. 2. To identify potential barriers to the resilience of adult female cancer survivors |

A qualitative approach using phenomenological design | Not mentioned |

Purposive and Maximum Variation Sampling Methods of adult female breast cancer survivors who were between 18 and 70 years of age had completed treatment and were symptom-free for the past 3 months and not exceeding 3 years. Exclusion criteria were – Adult female breast cancer survivors who were with metastasis, terminally ill and with comorbidities like renal, cardiac and neurological conditions. |

14 female breast cancer survivors. | In-depth, semi-structured interview | Colaizzi’s data analysis framework |

The majority of the studies used purposive sampling for recruitment. All used semistructured interviews for data collection except one study not mentioned and one study used checklist-guide interview. Most of the studies used thematic analysis or content analysis as their approach for data analysis except two studies employed Colaizzi’s method analysis, one study employed modified grounded theory analysis, one study employed interpetive phenomenological analysis and one study not specified. However, a few of the studies did not justify their chosen qualitative approach and many did not mention any theories or frameworks that guided their studies.

Identified domains

We mapped and summarized the identified codes for the concept of lived experience explored in the included studies into three main categories, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mapping the lived experience of resilience in chronic disease among adults in Asian countries

| 1st Author | SOCIOCULTURAL NORMS SHAPE RESILIENCE |

POSITIVE EMOTIONS NURTURE RESILIENCE |

COPING STRATEGIES TO GAIN RESILIENCE |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childrearing cultural background | Traditional Cultural beliefs |

Social relationships and support |

Spirituality | Optimistic about becoming healthy | Self-efficacy in self-care | Endurance during hardships |

Self-reflection on health |

Acceptance of having disease | Appreciation of life |

Improve disease literacy | Ability to deal with disease challenges |

Engage in meaningful activities | |

| Hassani et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Oruc et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Kusnanto et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Ariffin et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Pradilla et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Nordin et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Samsuri et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Zhang et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Luo D et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Chou et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Chavare et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Walton et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

Theme 1: sociocultural norms shaped resilience

The experience of resilience in chronic disease influenced by sociocultural background has been found in studies from most Asian regions [29–32, 34–40]. Most participants in such studies have stated that their journey experiences toward resilience in living with chronic disease were influenced by childhood upbringing [29, 37], traditional cultural beliefs [29, 37], social relationships and supports [29–32, 34–40] and spirituality [29, 34–39].

Culturally-mediated childhood development

The cultural background during childhood upbringing was reported in two studies from the Southern and Eastern Asia regions [29, 37]. The childhood experiences of a participant from Iran, who had assumed the role of caregiver to her mother with asthma and who had managed the home when her parents were ill, had helped her to be strong when dealing with difficulties in life [29]. Culturally, Asian children are trained to take care of sick family members and hold responsibilities to manage their living so that they will grow up to be resilient adults [29].

On the other hand, in Chinese culture, participants had been edified by Confucian ethics, and the impetus to fight chronic disease was seen as the family’s responsibility [37]. These cultural beliefs about health care have been instilled in all family members since childhood for generations and have helped participants to have resilience in facing adversity in later life [37].

Traditional cultural beliefs

Two studies from Eastern and Southern Asia regions indicated the role played by traditional culture and beliefs that encourage participants to become resilient in life [29, 37]. The cultural relationships between husband and wife have shaped participants’ resilience in the Southern Asian region [29].

Regarding culture, China has a distinctly different culture from those of other countries. Confucian ideologies such a “Ren” and “Li” in Chinese culture mean that Chinese people tend to repress their inner feelings and possess strong endurance against psychological distress [37]. Traditional ideologies, such as “Ren” encourage people to repress their negative emotions [37]. One participant stated:

“I seldom talk about my disease to my parents because I do not want them to worry about me.” [37].

Another Asian traditional culture in Iran prescribes that wives are not advised to express their negative feelings unless they are requested to do so by their husbands to encourage harmonious relationships between spouses [29].

“My husband never asks me how I feel.” [29] They explained that their husbands’ emotions were more important [29]. The partners prioritised each other’s needs over their own, leading to a tendency to hide negative feelings to create harmony within the relationships, thus influencing their resiliency [29].

Social relationships and supports

Eleven out of 12 studies have reported that social support encouraged resilience in Asian adults living with chronic disease [29–32, 34–40]. In Asian countries, family members provided technical, financial, and emotional support to the participants living with chronic disease [29–32, 34–40]. Culturally, the dynamic of the social relationship has provided much support to the patients by the children and extended relatives, hence strengthening their resilience in managing their disease [34–40].

Many participants were able to arrange finances for treatment through help from family members [29, 34, 39, 40]. The medical expenses of some participants from India and Malaysia were supported by their daughters [34, 40]. A participant stated:

“I am more comfortable talking with my eldest daughter. She always gives me an opinion. [.] I always go out with them. They always give me moral support other than financial aid. My second daughter said, she always prays for me.” [34].

A study in Indonesia demonstrated that participants were able to cope better with the disease by having good relationships with spouses and children as they never felt lonely [31]. Most of the participants’ experiences, and the support they had received from their spouses, families and extended families had fostered their resilience [29–32, 34–40].

“My mother-in-law was very supportive. She gave me strength to fight day by day and to move on.” [40].

In addition, employers and colleagues were also concerned and gave support in terms of motivation, financial aid and medical leave [34, 37, 40]. Doctor-patient relationship highly influenced the patient’s morale to bounce back to normal life. Participants expressed that the healthcare personnel at the tertiary care hospital were very approachable, explained the treatment, clarified their doubts and counselled them [34, 39, 40].

Spirituality

Half of the studies indicated that Asian culture also attributed the ability to maintain personal well-being while living with a chronic disease to spirituality [29, 34–36, 39, 40]. Malaysian participants described that spirituality and believing in God had helped them to accept their fate as cancer patients [34, 35]. A few Chinese participants who believed in Buddhism held the opinion that their souls would exist in other forms after they passed away and they believed that bodhisattva would bless them if they did good things that were beneficial to others [36]. Indian participants with underlying cancer acknowledged the grace of God in their lives through prayer, yoga, meditation, and listening to motivational songs and speeches to remain resilient [39, 40].

Theme 2: positive emotions nurtured resilience

Being optimistic about becoming healthy [29–33, 35–40], self-efficacy in self-care [29–33, 37–40], endurance when going through hardship [29, 31, 35, 36, 40], self-reflection on health [30, 34, 36–38], acceptance of having a disease [29, 30, 32–35, 38–40] and appreciation of life [29, 34, 36, 40] were the positive psychological experiences that encouraged resilience to chronic disease among adults in Asian countries.

Optimistic about becoming healthy

Most Asian participants were optimistic and had positive thoughts that they would one day become healthy [29–33, 35–40]. One participant from Indonesia mentioned that he had to be confident that he would get healthy and live a happy life [32]. A participant with kidney disease had the belief that his hopes could be achieved [33].

A participant with underlying cancer in Iran strongly believed that there was a cure for his disease and that it could be found while he was still alive [29]. Another participant from China said that she was very sad when she found out about the diagnosis, but after listening to the details of her condition, she believed she would get well soon [36]. Participants with type 2 diabetes highlighted how they started to gain resilience to get well and believed the disease could be controlled [31]. Positive thoughts and strong determination assisted them to face the hardship of living with the illness [35, 37–39].

Self-efficacy in self-care

Self-efficacy in performing self-care was reported in nine studies from Southern, Eastern and Southeast Asian regions as one of the experiences promoting resilience in chronic disease [29–33, 37–40]. Diabetic participants stated that once they learnt they had diabetes, they changed their diet, adopted more healthy eating behaviours, did not consume sweet foods and complied with the recommended diet [31]. They also started taking medicine regularly and exercising adequately [31].

Some of the participants had the attitude of living their lives and maintaining their health by checking on their conditions regularly and had a way of anticipating problems or developing personal strategies, such as maintaining an active lifestyle, during the treatment process [31, 32, 37–40].

Endurance during hardship

This review found that Asian participants had the endurance to keep themselves strong and healthy [29, 31, 35, 36, 40]. A participant mentioned he would do anything to be healthy, achieve a good quality of life and also be useful to his family and community [31].

A participant with cancer had the strength and courage to go through the hardship of fighting cancer while having a sick child who had undergone a kidney transplant [36]. Participants from India endured the side effects of chemotherapy without complaining to others [40].

Self-reflection on health

Five studies from Eastern and Southeast Asia regions demonstrated the role of self-reflection by describing how patients compared themselves with other patients who had more severe illnesses or were less fortunate [30, 34, 36–38].

A participant from Malaysia stated:

“When I did the radiotherapy, before that I said I was the person with the worst problem in this world, no one else. When I was in the hospital, I realized other people were worse off than me.” [34].

Some participants reflected on their aim in life because they had previously neglected their health [30, 36, 38].

“I reassessed and changed my priorities. I know I have to do some better things for my body because I did not treat my body well before.” [38].

Acceptance of having a chronic disease

Most participants from the Asian regions expressed that accepting their diagnoses, the pain, and the difficult situations of having these chronic diseases, had motivated them to get treatment [29, 30, 32–35, 38–40].

A participant with underlying DM from Indonesia stated:

“The important thing is not stress. Live happily. Alhamdulillah, now I can accept this pain.” [32].

A participant from Turkiye explained:

“When I learned I had cancer, I thought it was a disease that could happen to anyone. I immediately accepted my illness and started early treatment. I have easily adapted to the treatments. Accepting being resilient was my first step toward healing. I am recovering now.” [30].

Appreciation of life

Participants in four of the studies expressed their appreciation of life by acknowledging their blessings and maintaining harmonious relationships with their families [29, 34, 36, 40]. A participant from Iran mentioned:

“I have a good wife. The children are good. I still have the power to walk. All these give me hope.” [29].

Participants from India expressed a deep sense of gratitude and appreciation for having a second chance at life and felt a renewed strength to get back to work and move on with their lives [40].

Theme 3: problem-solving strategies fostered resilience

Asian adults shared how they were able to be resilient in living with chronic disease through improving disease literacy [30, 35–37, 39], being able to deal with disease challenges [29–35, 37–40] and engaging in meaningful activities [31, 32, 34–37, 39, 40].

Improved disease literacy

Five out of ten studies explained that improving knowledge had helped participants cope with the difficulties of handling their disease [30, 35–37, 39]. Some patients sought information about their disease on the internet or read books to gain a scientific understanding of the disease [35–37, 39].

“I read a lot of online blogs of patients suffering from RA. I searched many websites explaining the facts about RA. I realized that I don’t need to worry and get scared because of this disease. I understood that I could lead a normal life with the disease.” [39].

Some participants obtained knowledge about the disease through the explanation from the healthcare professionals (HCPs) and hence experienced less anxiety during the treatment process [30]. A participant stated:

“At the beginning of treatment, I knew little about breast cancer and bad mood troubled me for a long period. After learning relevant knowledge, I realized that the five-year survival rate of breast cancer patients was higher than I had previously anticipated. I felt lucky and grateful.” [36].

Ability to deal with disease challenges

Difficulties in getting treatment, side effects of medications and disease recurrence were among the challenges faced by participants. 11 studies indicated that participants used many strategies to deal with the challenges of chronic disease [29–35, 37–40].

In Indonesia, participants with CKD were able to find ways to overcome obstacles during hemodialysis [33] and participants with DM actively sought treatment whenever they felt unwell [31].

Participants from China shared that they persevered in finding personal solutions to manage bowel movement side effects after chemotherapy [38]. Another participant from India changed her way of performing daily tasks [39]:

“In the kitchen, I could not lift heavy utensils. Therefore, I started using light-weighted utensils.” [39].

Engaged in meaningful activities

Eight studies reported that the experience of engaging in meaningful activities had helped participants to stay resilient while living with chronic disease [31, 32, 34–37, 39, 40]. Participants from China found new hobbies to remain resilient while living with cancer [36].

“After receiving treatment, I wanted to enrich my life with new hobbies. I spent almost all of my free time knitting. My friends liked my achievement very much.” [36].

Listening to music, shopping, sports, going out and travelling, or resting, were common activities to remain positive and encourage resilience [35, 37]. Some participants participated in various types of complementary therapy such as yoga, meditation and listening to music, while others enjoyed going out with their friends at restaurants [39, 40].

“I love going out with my friends and trying different restaurants. Even though at times my jaw is stiff and I cannot eat, I go out to restaurants with my friends and enjoy the time.” [39].

Discussion

This review found three themes that comprise the lived experiences of resilience. Together these three overarching themes describe the resilience process as documented in published research and consist of diverse ethnicities, genders, and cultures making it applicable to Asian adult populations with chronic diseases.

Interestingly, Asian socio-cultural norms in terms of childhood experience and traditional cultural beliefs play a distinctive role in moulding resilience to chronic disease. This is echoed in a study from Hong Kong that found that resilience is associated with early living conditions and experiences such as family socialisation, childhood religious belief, and other experiences that have been associated with resilience in later life [41].

Asian parenting beliefs are shaped by a cultural emphasis on family members’ interdependence [42]. A study comparing childrearing philosophies among immigrant Chinese and European American mothers revealed different cultures [43]. Both groups of mothers emphasized the value of loving their children; however, European American mothers emphasized the importance of love to foster the child’s self-esteem, whereas Chinese mothers emphasized the importance of love to foster a close and lasting parent-child relationship [43]. Chinese mothers were driven by relational goals and concentrated primarily on harmonious relationships among family members, while European American mothers were driven by individual goals [43]. Asian cultures tend to lean towards collectivism while European American cultures tend to favour independence and individualism [44]. In the Collectivist culture, people are interdependent within their in-groups (family, tribe, or nation), prioritize the goals of their in-groups, shape their behavior primarily based on in-group norms, and behave communally [44]. This collectivist orientation elucidates participants’ concerned about their roles and relationships within their social groups. In addition, the influence of filial piety, as part of the cultural practices of the region, is a deeply ingrained value that dictates the respect, support and care children owe to their parents and the elderly [45].

Our review revealed traditional Chinese culture known as “Ren” and “Li”, encourages people to repress inner feelings to develop resilience in living with chronic disease [37]. Ren” and “Li,” two components from the five constant virtues are the core of pre-Qin Confucianism and important parts of traditional Chinese moral values [58]. “Ren” refers to inner moral sentiments while “Li” is extrinsic behavioral norms [58]. In many East-Asian, interdependent cultural contexts, emotional suppression is more common and less detrimental to psychological well-being and relationships than in Western cultural contexts [46, 47]. Some Southeast Asian women reported suppressing their emotions due to concerns about how others may perceive them [48]. A similar study on the perception of spousal support among women with breast cancer found that Asian-American women were predicted to be self-sacrificing and take care of their husbands and families, while European-American women were allowed to be reliant [49]. However, in the perceptions of Western folk theory and psychology, emotional suppression is considered unhealthy and associated with both poor psychological outcomes and low interpersonal well-being [50, 51].

Our review demonstrates spirituality across the cultures of Malays, Chinese, Indians, and Buddhists promotes a positive mindset and hopeful attitude to cope with chronic disease [29, 34–36, 39, 40]. The review showed similar findings to a study among African American adults with diabetes that highlighted the importance of spirituality, religious beliefs, and coping strategies in self-care activities [52].

Previous reviews found that self-efficacy, self-esteem, optimism, endurance, perseverance, internal locus, adaptability and acceptance of illness were reported as positive psychological responses that cultivate resilience in chronic illness [18, 19] and showed similar findings to our review. Furthermore, our review expands on this understanding as our qualitative data reveals the additional values of self-reflection on health and appreciation of life that fostered resilience in Asian adults with chronic diseases.

Previous existing reviews on resilience in living with chronic disease among non-Asian countries echo our findings on improved disease literacy, that is, educating one’s self or seeking information from books or the internet or joining information sessions [54] as well as adapting one’s activities such as taking things more slowly [55]. These studies highlighted the importance of engaging in meaningful activities as a key part of adjusting such as going on holidays, exercising, gardening, baking, or going for walks [54–56]. The studies have shown coping skills to gain resilience in living with chronic disease to be similar among Asian and non-Asian countries.

Our review identified several gaps in the literature and areas for future research. People’s resilience to chronic disease in Asia is strongly influenced by the nature of Asian culture. Despite the small number of studies, our review has identified the lack of focus in previous qualitative studies on the strong influence of the Asian sociocultural environment on the lived experience towards resilience in managing chronic diseases among the adults. Their experience during childhood, the social relationships within families, and the life challenges they faced have all contributed to strengthen their resilience. The review addressed the cultural dimensions of filial piety [29, 37] alongside traditional beliefs rooted in religiosity and spirituality [29–32, 34–40], using the examples of Confucianism and Buddhism that shaped resilience [36, 37]. The review examined the role of Ren and Li’s cultural frameworks [37] and highlighted collectivist culture within family structures, which nurtured resilience among adults living with chronic diseases in Asian countries [29–32, 34–40]. Still, additional research is required to delve deeper into the impact and scope of this cultural influence on clinical practices and policy development for adults with chronic illnesses within the Asian context. It is also essential to explore how this cultural outlook affects Asian individuals living in non-Asian countries Several qualitative data categories in our findings exhibit regional differences in terms of their prominence [29, 31, 34, 37, 40]. These distinctions could reflect divergent research priorities among authors from different regions, but they might also signify varying factors shaping resilience among adults in diverse Asian regions. Future studies should consider this heterogeneity into account, to consolidate the essence of this phenomenon among Asian populations.

This review has also identified that some of the qualitative studies were insufficient in articulating their qualitative approach and theoretical frameworks and were unclear in concluding the qualitative findings. In some studies, the thematic explanations were notably brief, consisting of a few sentences accompanied by related quotes. Conversely, qualitative findings typically demand a deeper interpretation and contextualization guided by the underlying theoretical frameworks [57]. The lack of detailed descriptions of the results hinders the reader’s ability to grasp the study’s context and outcomes fully. Future research should comprehensively report the qualitative methodologies employed, offering essential information on the study’s philosophical foundations.

Limitations

The study has several limitations that may affect the rigour of the findings. Firstly, the scoping review approach we employed primarily aims to identify research gaps and summarise findings but does not encompass a formal quality assessment of the included studies. This limitation constrains the utility of our findings for informing policy and clinical practice. Secondly, we omitted studies related to congenital diseases and psychiatric diseases within the realm of chronic diseases. This exclusion may affect the generalisability of our findings regarding the factors influencing resilience among Asians living with chronic diseases. Thirdly, we may have overlooked data from studies conducted in languages other than English, as these were excluded from our review.

Strengths

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive scoping review on experiences to gain resilience in chronic disease based on qualitative studies originating from Asian countries. We believe that this review contributes significantly to the global understanding of the journey to be resilient in adults having chronic diseases, specifically from the perspective of Asian individuals living in Asian countries.

Conclusion

The Asian sociocultural norms, emotional responses and coping strategies exert significant impact on resilience development among adults with chronic diseases in Asia. The depth of personal and sociocultural impact on the resilience of adults and its ramifications for the management and policies concerning chronic diseases in the Asian context warrants further research. Studies on the sociocultural lived experiences of resilience among adults living with chronic disease in Asian nationsare scarce and provide limited insights into their qualitative methodologies and findings. Future research should also comprehensively detail the methodologies to furnish contextual information regarding the theoretical framework and approach of the qualitative study design.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Academic Librarian Nurul Azurah, who assisted with developing the search strategy.

Abbreviations

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- HCPs

Healthcare professionals

- HF

Heart failure

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- JBI

Joanna Brings Institute

- NCDs

Non-communicable disease

- PRISMA-ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Author contributions

MMZ: Conceptualisation, design and methodology, formal analysis, writing (lead) original draft preparation, review and editing. RAR: Supervisor, conceptualisation; design and methodology, writing original draft (supporting); review and editing (equal). RM: Primary supervisor, conceptualisation, design and methodology, formal analysis, writing original draft preparation (supporting), review and editing (equal). AAK: Supervisor, conceptualisation, design and methodology, formal analysis, writing original draft preparation (supporting), review and editing (supporting). NSR: Industry partner, conceptualisation, design and methodology, review and editing (supporting) and NM: Supervisor, conceptualisation, design and methodology, review and editing (supporting). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided for this research through the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grants Scheme (FRGS/1/2021/SKK04/USM/02/4).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Human ethics and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Razlina Abdul Rahman, Email: razlina@usm.my.

Rosediani Muhamad, Email: rosesyam@usm.my.

References

- 1.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

- 2.Noncommunicable Disease. World Health Organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- 3.Eggenberger SK, Meiers SJ, Krumwiede N, Bliesmer M, Earle P. Reintegration within families in the context of chronic illness: a family health promoting process. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn. 2011;3(3):283–92. 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2011.01101.x [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cal SF, Sá LR, Glustak ME, Santiago MB. Resilience in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Cogent Psychol. 2015;2(1):1024928. 10.1080/23311908.2015.1024928 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wermelinger Ávila MP, Lucchetti ALG, Lucchetti G. Association between depression and resilience in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(3):237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resilience. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience

- 7.Johnston MC, Porteous T, Crilly MA, Burton CD, Elliott A, Iversen L, et al. Physical disease and resilient outcomes: a systematic review of resilience definitions and study methods. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(2):168–80. 10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart DE, Yuen T. A systematic review of resilience in the physically ill. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(3):199–209. 10.1016/j.psym.2011.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Persp Med Educ. 2019;8(2):90–7. 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Servaes J. Reflections on the differences in Asian and European values and communication modes. Asian J Commun. 2000;10(2):53–70. 10.1080/01292980009364784 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesantes MA, Lazo-Porras M, Ávila-Ramírez JR, Caycho M, Villamonte GY, Sánchez-Pérez GP, et al. Resilience in vulnerable populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1180–8. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Love MF, Wood GL, Wardell DW, Beauchamp JE. Resilience and associated psychological, social/cultural, behavioural, and biological factors in patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20(6):604–17. 10.1093/eurjcn/zvaa008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghulam A, Bonaccio M, Costanzo S, Gianfagna F, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. Psychological resilience, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disturbances: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:817298. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.817298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JW, Mealy R, Saldanha IJ, Loucks EB, Needham BL, Sims M, et al. Multilevel resilience resources and cardiovascular disease in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2022;41(4):278–90. 10.1037/hea0001069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketcham A, Matus A, Riegel B. Resilience and depressive symptoms in adults with cardiac disease: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;37(4):312–23. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans L, Bell D, Smith SMS. Resilience in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure. Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;1(14). 10.21767/2572-5548.100014

- 17.Aizpurua-Perez I, Perez-Tejada J. Resilience in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;49:101854. 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George T, Shah F, Tiwari A, Gutierrez e, Ji J, Kuchel GA, et al. Resilience in older adults with cancer: a scoping literature review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14(1):101349. 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.19, Sihvola S, Kuosmanen L, Kvist T. Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022;56:102079. 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gheshlagh RG, Sayehmiri K, Ebadi A, Dalvandi A, Dalvand S, Tabrizi KN. Resilience of patients with chronic physical diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(7):e38562. 10.5812/ircmj.38562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim GM, Lim JY, Kim EJ, Park S-M. Resilience of patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(4):797–807. 10.1111/hsc.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Y, Bhattarai M, Kuo W-c, Lisa B. Relationship between resilience and self-care in people with chronic conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(9–10):2041–55. 10.1111/jocn.16258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seong H, Lashley H, Bowers K, Holmes S, Fortinsky RH, Zhu S, et al. Resilience in relation to older adults with multimorbidity: a scoping review. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;48:85–93. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

- 25.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19(1):3–10. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, McInerney P, Alexander L, Tricco AC, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synthesis. 2023;21(3):520–32. 10.11124/jbies-22-00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassani P, Izadi-Avanji FS, Rakhshan M, Majd HA. A phenomenological study on resilience of the elderly suffering from chronic disease: a qualitative study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:59–67. 10.2147/prbm.S121336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oruc M, Demirci AD, Kabukcuoglu K. A grounded theory of resilience experiences of women with gynecological cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;64:102323. 10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kusnanto K, Arifin H, Widyawati IY. A qualitative study exploring diabetes resilience among adults with regulated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):1681–87. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arifin H, Kusnanto K, Widyawati IY. How did i feel before becoming type 2 diabetes mellitus? A qualitative study in adult type 2 diabetes. Indonesian Nurs J Educ Clin (INJEC). 2020;5(1):27–34. 10.24990/injec.v5i1.280 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradila DA, Satiadarma MP, Darmawhan US. The resilience of elderly patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis. Adv Social Sci Educ Humanit Res (JASSAH). 2021;570:1191–96. 10.2991/assehr.k.210805.187 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordin A, Mohamed Hussin NA. The journey towards resilience among Malaysian woman with breast cancer. Illn Crises Loss. 2023;0(0). 10.1177/10541373221147393

- 35.Sumari M, Kassim NM, Razak NSAA. A conceptualisation of resilience among cancer surviving employed women in Malaysia. Qual Rep. 2022;27(8):1552–78. 10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5327 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, Li H, Liu A, Wang H, Mei Y, Dou W. Factors promoting resilience among breast cancer patients: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2018;54(3):293–303. 10.12659/msm.907730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo D, Lin Z, Shang XC, Li S. I can fight it! A qualitative study of resilience in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6(2):127–33. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chou YJ, Wang YC, Lin BR, Shun SC. Resilience process in individuals with colorectal cancer: a qualitative study. J Qual Life Res. 2023;32(3):681–90. 10.1007/s11136-022-03242-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chavare S, Natu S. Exploring resilience in Indian women with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative approach. J Psychosoc Res. 2020;15(1):305–17. 10.32381/JPR.2020.15.01.26 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walton M, Lee P. Lived experience of adult female cancer survivors to discover common protective resilience factors to cope with cancer experience and to identify potential barriers to resilience. Indian J Palliat Care. 2023;29(2):186–94. 10.25259/IJPC_214_2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Cheung CK, Kam PK. Resiliency in older Hong Kong Chinese: using the grounded theory approach to reveal social and spiritual conditions. J Aging Stud. 2012;26(3):355–67. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chao R, Tseng V. Parenting of asians. Handb Parent. 2002;4:59–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chao RK. Chinese and European American cultural models of the self-reflected in mothers’ childrearing beliefs. Ethos. 1995;23:328–54. 10.1525/eth.1995.23.3.02a00030

- 44.Triandis HC. Individualism-collectivism, personality. J Pers. 2001;69:907–24. 10.1111/1467-6494.696169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xing G. Filial piety in Chinese Buddhism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. 28 Mar. 2018; https://oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-559

- 46.Butler EA, Lee TL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and culture: are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion. 2007;7(1):30–48. 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Nakagawa S. Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94(6):925–37. 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahmati A, Poormirzaei M, Bagheri M. Investigating the emotional theory of mind in Iranian married women: a descriptive phenomenological study. Qual Rep. 2019;24(4):906–17. 10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3589 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch DK. Breast cancer patients’ perceptions of their husbands’ support in a cross-cultural context. Psychooncology. 2003;12(1):24–37. 10.1002/pon.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–62. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haga SM, Kraft P, Corby E-K. Emotion regulation: antecedents and well-being outcomes of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression in cross-cultural samples. J Happiness Stud. 2009;10(3):271–91. 10.1007/s10902-007-9080-3 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi SA, Hastings JF. Religion, spirituality, coping, and resilience among African Americans with diabetes. J Relig Spiritual Soc Work. 2019;38(1):93–114. 10.1080/15426432.2018.1524735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:208. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Windle G, Roberts J, MacLeod C, Algar-Skaife K, Sullivan MP, Brotherhood E, et al. I have never bounced back’: resilience and living with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27(12):2355–67. 10.1080/13607863.2023.2196248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarre S, Redlich C, Tinker A, Sadler E, Bhalla A, McKevitt C. A systematic review of qualitative studies on adjusting after stroke: lessons for the study of resilience. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(9):716–26. 10.3109/09638288.2013.814724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Windle G, Bennett KM, MacLeod C and the CFAS WALES research team. The influence of life experiences on the development of resilience in older people with co-morbid health problems. Front Med. 2020;7:502314. 10.3389/fmed.2020.502314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. 10.1097/acm.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu B, Xing F, Fan M and Zhu T (2021) Research on the Evolution of “Ren” and “Li” in SikuQuanshu Confucian Classics. Front. Psychol. 12:603344. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.603344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.