Abstract

Low-grade chronic inflammation without obvious infection is defined as “inflammageing” and a key driver of skin ageing. Although the importance of modulating inflammageing for treating skin diseases and restoring cutaneous homeostasis is increasingly being recognized. However, the mechanisms underlying skin inflammageing, particularly those associated with natural treatments, have not been systematically elucidated. This review explores the signaling pathways associated with skin inflammageing, as well as the natural plants and compounds that directly or indirectly target these pathways. Nine signaling pathways and 60 plants/constituents related to skin anti-inflammageing are discussed, exploring plant mechanisms to mitigate skin inflammageing. Common natural plants with anti-inflammageing activity are detailed by active ingredients, mechanisms, therapeutic potential, and quantitative effects on skin inflammageing modulation. This review strengthens our understanding of these botanical ingredients as natural interventions against skin inflammageing and provides directions for future research.

Keywords: cutaneous homeostasis, inflammageing, plant extract, skin ageing

Introduction

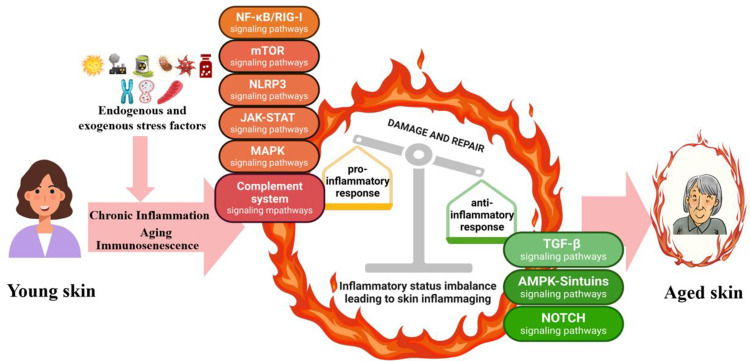

Age-associated sterile, chronic, and low-grade inflammation is commonly termed inflammageing, and is a marker of biological ageing, multimorbidity, and mortality risk.1 Inflammageing occurs in all organs of our body, and the skin is the most intuitive manifestation. Skin becomes increasingly inflamed with age, with abundant cell inflammation accelerating ageing of the skin, leading to wrinkles, sagging skin, and possibly cancer.2 Skin inflammageing is traditionally considered detrimental to human health because of its association with pro-inflammatory factor accumulation and various skin issues. However, from an evolutionary standpoint, inflammageing is increasingly seen as an adaptive or remodeling process.3 Thus, targeting the ageing immune system for immune rejuvenation could be a strategic approach to preserve skin homeostasis and enhance immune-inflammatory functions. Balancing pro-inflammageing and anti-inflammageing states is crucial to effectively address inflammatory skin ageing. As such, understanding the specific mechanisms of skin inflammageing will improve our ability to facilitate healthy skin ageing. External factors such as UV radiation, particulate matter (PM2.5), and seasonal changes all exacerbate inflammageing. Cellular senescence, inflammasome dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, autophagy, ubiquitin-proteasome system impairment, and DNA damage responses also contribute to skin inflammageing.4 These processes are governed by several signaling pathways, including NF-κB/RIG-I, mTOR, TGF-β, AMPK–SIRTs, complement system, NLRP3, Notch, JAK–STAT, and MAPK pathways (Figure 1).5–11 However, the pathways that affect skin inflammageing have not yet been systematically summarized.

Figure 1.

Cellular signaling pathways involved in the regulation of skin inflammaging. Imbalances in skin-related inflammation leads to skin aging.

Notes: Created in BioRender. Ren, Q. (2024) https://BioRender.com/p66l768.

Botanicals such as quercetin, fisetin, and resveratrol exert anti-inflammatory and anti-ageing benefits.12,13 Botanical extract-based skincare is recommended by physicians to combat inflammageing.14 Thus, natural plant extracts or monomers that target inflammageing pathways show potential as effective preventive strategies.15 This comprehensive review explores research from the past 13 years available from PubMed and ScienceDirect to update our understanding of skin inflammageing pathways and identify significant medicinal plant extracts or monomers with potential anti-inflammageing effects on the skin. Despite some plant chemical properties remaining uncharacterized, their pharmacological evaluation has supported the advancement of skincare products sourced from plants with clinically proven anti-inflammageing benefits.

Role of Signaling Pathways in Skin Inflammageing

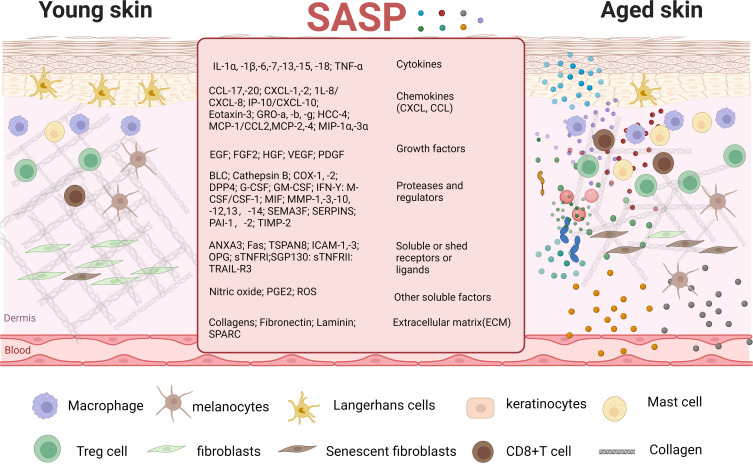

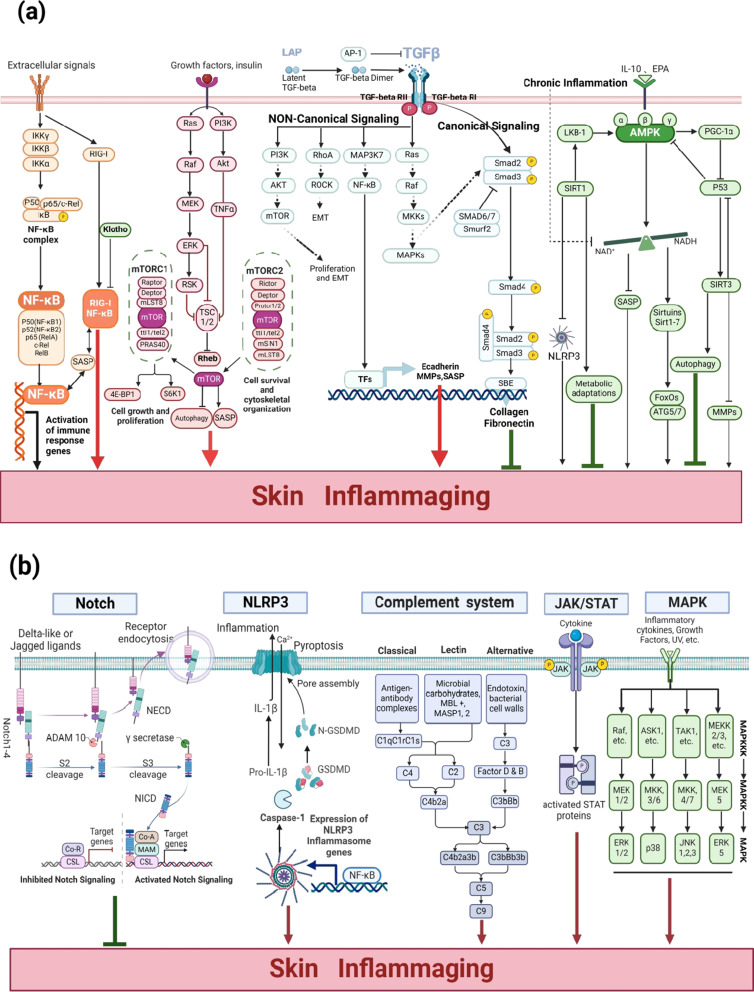

The main features of senescent cells are manifested in the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Skin inflammageing occurs when senescent cells accumulate in the skin and release SASP factors, including IL-(1β, −6, −8, −18), TNF-α and CRP; these cells include keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, and immune cells4 (Figure 2). Typically, a less than two-fold increase in pro-inflammatory mediators is a positive response by the skin that maintains homeostatic stability, known as cold-inflammageing. However, continuous exposure to external stressors such as UV light and pollution can promote senescence and inflammatory phenotypes in skin.16 Furthermore, disruption of the skin’s homeostatic balance increases the formation of cytokines (two- to four-fold increase).17 This review involved an extensive literature search, followed by integration of the findings regarding the signaling pathways related to skin inflammageing, including NF-κB/RIG-I, mTOR, TGF-β, AMPK–SIRTs, Notch, complement system, NLRP3, JAK–STAT, and MAPK, to elucidate the mechanisms of inflammageing (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cells and molecules involved in skin inflammaging. In the process of skin inflammageing, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, and immune cells secrete SASP. SASP further causes aging of surrounding young cells, forming a vicious cycle.

Notes: Created in BioRender. Ren, Q. (2024) https://BioRender.com/q47v111.

Figure 3.

(a) The core regulatory pathways involved skin inflammaging (including NF-κB/RIG-I, mTOR, TGF-β, AMPK–SIRTs pathways). Created in BioRender. Ren, Q. (2024) https://BioRender.com/s82l596. (b) The other regulatory pathways of skin inflammaging (including complement system, NLRP3, Notch, JAK–STAT, and MAPK pathways). Created in BioRender. Ren, Q. (2024) https://BioRender.com/h71i391.

Role of the NF-κB/RIG-I Pathway

NF-κB activation, driven by ageing factors such as ROS, senescent cells, and DNA damage, leads to increased inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), further amplifying inflammatory and age-related disturbances through classical pathway activation.18 The trans-activation motifs of NF-κB are key regulators associated with ageing across human tissues, and persistent NF-κB signaling activation fosters cellular senescence.19 SASP produced by senescent cells necessitates NF-κB signaling to impact adjacent youthful cells.20 RIG-I, a pattern recognition receptor in the skin, identifies viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns,21 and its blockade mitigates senescence-associated inflammation, extending cell growth.22 RIG-I is upregulated in senescent cells via the ATM-IRF1 axis, which mediates IL-6 and IL-8 expression.23 Klotho, by interacting with RIG-I, inhibits induced IL-6 and IL-8 expression, acting as an anti-ageing agent by dampening RIG-I-mediated inflammation.24 Loss of the ageing-related protein Klotho triggers the NF-κB/RIG-I pathway, enhancing pro-inflammatory mediator production.25 Furthermore, RIG-I promotes keratinocyte proliferation and wound repair by inducing tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 (TIMP-1) expression through NF-κB signaling pathway.23 NF-κB/RIG-1 activation driven by ageing factors therefore increases inflammatory cytokine production and affects skin ageing.15

Role of the mTOR Signaling Pathway

The mTOR regulates cell growth, metabolism, and nutrient signaling, with hyperactivation often linked to inflammation.26 This pathway comprises two complexes: mTORC1 is vital for regulating cell growth and substrate phosphorylation to increase anabolism (eg, mRNA translation, and lipid synthesis) or inhibit catabolism (eg, autophagy); mTORC2 promotes cell survival and cytoskeletal organization via Akt activation, with both complexes contributing to inflammageing (Figure 3a).27 Overexpression of the upstream mTOR modulators (eg, PI3Ks, Akt, TNF-α, Ras, Raf kinase, MEK, ERK1/2, and Rsk) escalates mTORC1 activity, positioning mTOR at the center of inflammageing processes.26 mTOR overactivation induces cellular senescence, whereas inhibition through rapamycin or genetic interventions halts senescence, attenuates SASP, and prolongs the lifespan of mice.28,29 Thus, inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR or RAS/ERK/mTOR pathways and restoring autophagy may decelerate skin cell senescence. Consequently, the mTOR signaling pathway, and especially its imbalances, affect skin inflammation and cell ageing. Therefore, maintaining balanced mTOR signaling is crucial for skin health.

Role of the TGF-β Signaling Pathway

TGF-β, a multifaceted cytokine, regulates cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and cellular homeostasis.30 TGF-β signaling is crucial for modulations to the skin inflammageing process. TGF-β1 is secreted in a latent form, activated when the LAP is cleaved by mediators such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2/MMP9, ROS, and integrins.31 This pathway is divided into classical and non-classical routes. Non-classical signaling pathways include interactions with RAS, MAP3K7, Rho/Rock, and PI3K/AKT.32 Activation of TGF-β/Ras promotes cellular ageing, cell cycle arrest, and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-6, −1β, −8, −1α, and MCP).33 Thus, signaling through TGF-β/Ras and its downstream effectors exacerbates skin inflammageing. Moreover, Ras signaling may be involved in skin inflammageing in animals.34 TGF-β activates MAP3K7 (also known as TAK1) to stimulate the NF-κB pathway, thereby exacerbating skin inflammageing.35 TGF-β also stimulates the Rho/ROCK pathway to promote pro-inflammatory factor release. Furthermore, TGF-β activates PI3K/AKT to stimulate the mTOR pathway, thereby exacerbating skin inflammageing. Thus, TGF-β non-classical pathway activation primarily affects other factors to subsequently aggravate skin inflammageing. Furthermore, as part of the SASP, TGF-β contributes to maintaining the senescent phenotype and age-related pathologies.30

The core function of classical TGF-β signaling in the skin is the induction of type I pre-collagen synthesis and connective tissue growth factor secretion.36 Classically, TGF-β initiates signaling by binding to TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII, leading to Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation.37 These phosphorylated Smads form a complex with Smad4, which then regulates gene expression in the nucleus through Smad binding elements ageing impacts TGF-β signaling, with decreased TGF-βRII expression in aged dermal fibroblasts disrupting the TGF-β pathway, thereby reducing collagen synthesis and increasing degradation, ultimately leading to skin thinning.32,36 TGF-β signaling impairment and TGF-β ligand upregulation results in cellular inflammation.30 Thus, classical TGF-β pathway activation promotes type I collagen production via the Smad pathway, thereby inhibiting skin inflammageing (Figure 3a). In summary, TGF-β is involved in skin inflammageing through classical and non-canonical pathways, and targeting the TGF-β signaling pathway could help modulate the inflammageing phenotype.

Role of the AMPK–SIRTs Pathway

AMPK is crucial for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis and sensing metabolic stress, it regulates inflammation, oxidative stress, autophagy, and other pathways.38 AMPK enzyme activity declines in aged skin39 and is lost in keratinocytes after acute injury or UVB exposure, which leads to the hyperproliferation and activation of mTOR signaling.40 Metformin, a diabetes medication and anti-ageing agent, utilizes AMPK to curb stress-induced cellular proliferation40 and modulates mitochondrial function, reducing age-related inflammation.41 AMPK can regulate the AMPK/SIRT1 and AMPK/mTOR pathways, which relieve neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain.42 Furthermore, Activation of AMPK enhances the biosynthesis and/or stability of NAD+. This augmentation in NAD+ concentration subsequently serves as a critical signal to induce the expression of Sirt1.43 Sirt1, in turn, deacetylates LKB-1, an AMPK activator, forming a positive feedback loop.44 In terms of functionality, activation of AMPK can suppress mTORC1 through activating TSC1/2, and it also prompts Sirtuins to catalyze the deacetylation of FoxO proteins or autophagy-associated proteins, namely ATG5 and ATG7,45 resulting in an upregulation of PGC-1α expression which improves mitochondrial biogenesis, and cytoplasmic p53 inhibition, which facilitates autophagy.43 Sirtuins, comprising seven proteins (SIRT1–SIRT7), play a pivotal role in postponing cellular ageing and augmenting organismal lifespan through the regulation of various cellular mechanisms.46 Age-related metabolic inflammation depletes NAD+, which subsequently reduces Sirt activity. The absence of Sirt1 diminishes mitochondrial biogenesis, while the depletion of mitochondrial Sirt3 weakens mitochondrial antioxidant defenses and repair mechanisms. Additionally, a reduction in NAD+ levels can hinder the function of Sirt2 and elevate the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome.47 Thus, inflammation may induce a positive feedback loop by altering the Sirtuin function, which promotes inflammageing. SIRT1 deacetylase-activated keratinocytes counteract the inflammatory response induced by LPS48 (Figure 3a). Thus, AMPK–SIRTs pathway activation could help resist inflammageing damage to the skin.

Role of Other Pathways

The mechanisms underlying skin inflammageing are intricate and involve activating NF-κB/RIG-I, mTOR, and TGF-β non-classical signaling pathways, which exacerbate inflammation and accelerate skin ageing. Conversely, AMPK–SIRTs and TGF-β classical signaling pathway activation could inhibit inflammageing damage. Several additional signaling pathways have been identified, including Notch, the complement system, and the NLRP3, JAK–STAT, and MAPK signaling pathways; however, relatively little evidence exists for their direct regulation of skin inflammageing and fewer modulators appear to act primarily via these pathways.

The process of epidermal differentiation and proliferation is orchestrated by Notch signaling.49 The Notch pathway may regulate various age-related skin diseases characterized by chronic inflammation.50 In healthy human skin, Notch receptors and ligands are abundantly expressed in epidermal keratinocytes. Notch signaling has the potential to eliminate senescent cells within the epidermis. Furthermore, a decline in JAG1 expression in the basal layer as a result of ageing may contribute to the accumulation of senescent cells due to weakened Notch signaling activity.51 Therefore, enhanced JAG1/Notch signaling may help clear epidermal senescent cells and alleviate skin inflammation and ageing (Figure 3b).

Keratinocytes express a variety of genes associated with inflammasomes, providing evidence for the notion that inflammasomes are involved in the process of skin inflammageing.8 NLRP3 is involved in pyroptosis. When NLRP3 is activated, the NLRP3 inflammasome assembles to form a complex, which then activates pro-Caspase-1 to form active cleaved Caspase-1 and induces the thermogenic executive protein GSDMD to form cytotoxic GSDMD-N. This is then recruited to the cell membrane to form thermogenic pores, promoting IL-1β and IL-18 expression.52 Skin inflammageing is accompanied by NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The depletion of NAD+ serves as a non-transcriptional initiating cue for the activation of NLRP3, facilitated by the clustering of mitochondria around the nucleus. Furthermore, the reduction of NAD+ levels associated with ageing can prompt the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in environments abundant in ATP.53 Moreover, NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition improved the lifespan of the murine model for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria,54 indicating that the NLRP3 pathway is pivotal for managing skin inflammageing, and that suppression of this pathway can effectively alleviate inflammageing symptoms (Figure 3b).

The skin’s complement system is activated via three pathways: lectin, classical, and alternative (Figure 3b).9 Keratinocytes produce complement proteins such as C3, Factor B, and C4, which are regulated and promoted by TNF-α, IL-1α, and IFN-γ.55 Inhibiting the C5aR1 signaling cascade within the complement system leads to a decrease in skin microbial diversity and also dampens the expression of cytokines, pattern recognition receptors, and antimicrobial peptides, thereby compromising the skin’s defense against pathogenic microorganisms.56 With ageing, the skin’s complement system increases and activates, potentially contributing to the process of inflammageing.57 For example, UV light stimulates epidermal keratinocytes to produce C3 and completion factor B via the alternative pathway.58 An overactive complement system can damage the dermoepidermal junction, leading to the release of MMPs and ROS that degrade the extracellular matrix ECM.16 The complement system also affects melanocyte function and may be associated with age spot development.16 Complement activation-mediated inflammageing may contribute to enlarged facial pores, a prominent feature of ageing skin.59 Understanding how the complement system drives skin inflammageing and ageing-related skin diseases could provide valuable insights for dermatologists and researchers related to the development of improved therapeutics.

The JAK–STAT signaling pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases of the skin, including vitiligo, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis.10 JAKs are a family of four proteins, JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, that regulate inflammation by activating intracytoplasmic transcription factors called STAT.60 Inflammation triggered by the JAK–STAT signaling pathway inhibits epidermal stem cell function, leading to skin ageing.61

MAPK is a group of serine/threonine protein kinases comprising three families, ERK, JNK, and P38. Among them, ERK consists of ERK1/2 and ERK5, P38 MAPK consists of p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ isoforms, and JNK consists of JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3 isoforms. The MAPK pathway has three levels of signaling: the MAPK, the MAPK kinase (MEK or MKK), and the kinase of the MAPK kinase (MEKK or MKKK). These three kinases can be sequentially activated.62 The MAPK pathway promotes the production of MMPs and inflammatory cytokines through the regulation of SASP, which leads to cellular senescence.11 TNF-α rapidly activates the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, causing the premature senescence of human skin fibroblasts.63

Regulatory Roles of Natural Plants in Skin Inflammageing

Scientific advances increasingly facilitate research into the superior efficacy of natural plants as modulators of skin inflammageing. This section underscores the potential of natural plants as adjunctive treatments to combat skin inflammageing by modulating inflammatory and ageing-related pathways. Tables 1–4 detail 60 plant extracts and monomers that influence skin health through the key identified signaling pathways. The aim is to correlate these natural extracts and monomers with observed anti-inflammatory and anti-ageing effects, providing insights into their specific actions on skin health.

Table 1.

Natural Plants That Regulate Skin Inflammageing via the NF-κB/RIG-I Pathway

| No. | Natural Plant/Compound | Plant Sources/Main Compounds | Mechanism of Action | Model of Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Centella asiatica extract | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, and terpenoids | NF-κB pathway; iNOS; COX-2; TNF-α; IL-1β, −1α; IgE; p65; p50; DNA | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [64–67] |

| 2 | Pomegranate | Anthocyanins, catechin, ellagic acid and gallic acids, and other polyphenolic compounds | NF-κB pathway; MMP-1, −3; Col1A1; Timp3 | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [68–72] |

| 3 | Quercetin | Various natural plants such as Sophora japonica L., Psidium guajava L. | NF-κB and Src/Syk/NF-κB pathways; MMP1, −2, −3, −9; COX-2; SOD1, −2; IL-1β, −6, −8, −17, −10; PKCδ; JAK2; GSH; CAT; MDA; TRAF3; α-MSH; TNF-α | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [12,73–75] |

| 4 | Quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucuronide | Wine, Hypericum hirsutum, Nelumbo nucifera, Oenothera biennis, and green beans | NF-κB pathways; AP-1; α-MSH; TNF-α; COX-2 | Human keratinocytes and melanoma cells | [76] |

| 5 | EGCG | Tea | NF-κB/RIG-I pathway; AP-1; IL-1, −6, −8, −17; PCNA; MMP-1; collagenase mRNA; TRAF6; SOD; CAT; MDA; JAK2; STAT1; STAT3 | Mouse model and in vitro experiments | [77–79] |

| 6 | Luteolin | Leaves, stems, and branches of Reseda odorata L. and a variety of natural herbs, vegetables, and fruits | NF-κB pathways; NO; MDA; pro-inflammatory mediators (eg, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8,-17,-22, TNF-α, and COX-2) | Clinical trial; mouse models and in vitro experiments | [80] |

| 7 | Carotenoids | β-carotene, astaxanthin, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, capsaicin, and astaxanthin | NF-κB, AKT/mTOR and Bcl-2 pathways | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [81,82] |

| 8 | Pterostilbene | Blueberries | NF-κB pathway; ROS; COX-2; MMP-9; AQP-3 | Mice model and HaCaTs | [83] |

| 9 | Myricetin | Natural foods such as berries, vegetables, teas, wine, and herbs | NF-κB pathway; pro-inflammatory mediators (eg, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-13, IL-8 and CCL17); MMP-9 | Cell experiments | [84] |

| 10 | Artemisinin | Artemisia annua L. | NF-κB pathway; IL-1β, −6; TNFα; TLR2; chemokines (CXCL10, CCL20, CCL2, and CXCL2); ROS; p16INK4a; SOD; β-catenin; apoptosis; proliferation | Mouse models and cell experiments | [85] |

| 11 | Sulforaphane | Eg, broccoli, brussels sprouts, cabbage | NF-κB pathway; COX-2; IL-6; TNF-α; IL-1β; AP-1; STAT1; MITF; ET-1; PGE2; TYRP1; tyrosinase | Mouse models and cell experiments | [86,87] |

| 12 | Lithospermum erythrorhizon (Gromwell) root extract | Shikonin | NF-κB pathways; Nrf2/ARE; inhibiting glycation; TNF-α | Cell experiments | [88,89] |

| 13 | Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker extract | Polymethoxyflavones; methoxyflavones | NF-κB pathway; IL-6, −8; COX-2; collagen and elastin fibers | Mice models and cell experiments | [90] |

| 14 | Soy isoflavones | Daidzein and genistein | NF-κB pathway; COX-2; IL-6, −1α; antioxidant enzymes | Clinical Trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [91,201] |

Table 2.

Natural Plants That Regulate Skin Inflammageing via the mTOR Signaling Pathway

| No. | Natural Plant/Compound | Plant Sources/Main Compounds | Mechanism of Action | Model of Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | Cordyceps | Cordyceps sinensis; Cordyceps cicadae (Miq.) | ROS/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway; HAS2; MMP12 collagen and elastin synthesis | Cell experiments | [92–97] |

| 16 | Curcumin | Curcuma longa L. | mTOR pathway; IL-17, −6, −1β; TNF-α; IFN-γ; involucrin; filaggrin; PPAR-γ; TLR4-MD2; mRNA; involucrin; filaggrin | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [98–102] |

| 17 | Fisetin | Found in fruits and vegetables, including strawberries, apples, and cucumbers. | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway; mTOR/IL-17A; IL-6β,-53; autophagy; MMPs; COX-2; Nrf2 | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [103–109] |

| 18 | Anthocyanin | Purple sweet potato, pomegranates, and grapes. | PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/MEK/ERK/mTOR pathway; 4E-BP; MMP-9, −2 | Mice models and cell experiments | [110–115] |

| 19 | Myrothamnus flabellifolia extract | Phenolic compounds | mTOR pathway; Park2; Atg7; LC3B; NLRP3; ROS, NF-κB, IL-1β, IL-6, MMPs; caspase-1; HMGB1; RAGE; filaggrin; claudin-1 | Clinical Trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [116] |

| 20 | Novel phytopeptides | – | mTOR pathway | Vitro experiments | [117] |

| 21 | Chrysanthemum boreale flowers extract | Handelin | mTOR/AMPK pathway | Cell experiments | [118] |

| 22 | Latifolin | Dalbergia odorifera T. | mTOR pathway; Nrf2; SIRT1; IL-6; IL-8; RANTES; MDC; ICAM-1; p38; JNK | Cell experiments | [119] |

| 23 | Stigmasterol | Vegetable fats or oils from many plants |

AKT/mTOR pathway; TNF-α, IL-1β,-6; iNOS; COX-2; caspase-3; JAK–STAT pathway | Mice models and cell experiments | [120] |

| 24 | Mangosteen | α-, β-, γ-mangostins, isogarcinol, and gartanin | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway; MMP-1,-9; IL-23/Th17; TNF-α; IL-2,-10; IFN-γ | Mice models and cell experiments | [121–123] |

| 25 | Momordica charantia L. extract | Terpenoids, saponins, flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, phenols, etc. | PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway | Mice model | [124] |

| 26 | Isatis tinctoria L. leaf extract | 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, anthranilic acid, kynurenic acid, and linarin |

mTOR/NF-κB/SASP, MAPK/NF-κB pathway; SA-β-GAL | Cell experiment | [125] |

| 27 | Amaranthus cruentus L. seed oil | Palmitic acid; oleic acid; linoleic acid; stearic acid | AKT/mTOR pathway | Cell experiment | [126] |

| 28 | Mikania micrantha L. extract | Flavonoids | FAK/Akt/mTOR pathway; MMP-2, −9 | Animal models and in vitro experiments | [127] |

| 29 | Nypa fruticans Wurmb extract | Polyphenols and flavonoids | PI3K/AKT/mTOR/CREB and MAPK signaling pathways | Cell experiment | [202] |

Table 3.

Natural Plants That Regulate Skin Inflammageing via the TGF-β Signaling Pathway

| No. | Natural Plant/Compound | Plant Sources/Main Compounds | Mechanism of Action | Model of Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Prunus yeonesis Matsum. extract | Genistein, naringenin, sakuranetin, prunetin, and amygdalin | TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway; MMP-1, −3; NO | Clinical trial and cell experiments | [129–132] |

| 31 | Eucalyptus globulus L. extract | Phenolic compounds | TGF-β/Smad pathway; MMPs; β-galactosidase; IL-6, NO and other pro-inflammatory mediators | Mice model and cell experiments | [128,133] |

| 32 | Ellagic acid | Berries and pomegranates | TGF-β/Smad pathway; IL-1β, −6; elastin; collagen; Col1A1; TERT; Timp3; MMP3 | Mice model and cell experiments | [134–138] |

| 33 | Terminalia arjuna extract | Pentacyclic triterpenoids | TGF-β signaling pathway; TEWL; IL-6, COX-2, inos and ODC | Clinical Trial and mice model | [139,140] |

| 34 | Portulaca oleracea L. extract | Oleracone C; portulacanone A; portulacanon D | TGF-β/Smad Pathway; MMP-1; type I. procollagen; IL-1β,-8; TNF-α; NF-κB pathway | Clinical Trial and cell experiments | [141,142] |

| 35 | Seaweed extract | Fucosterol; low-molecular-weight fucoidan | TGF-β1/AP-1 signaling; MMPs; FGF-2; IL-1β,-6; p-c-Jun,-Fos; NF-κB; p38-MAPK; Erk1/2; JNK | Animal models and cell experiments | [143] |

| 36 | Limonium tetragonum (Thunb.) Bullock extract | Myricetin 3-O-β-d-galacto-pyranoside | TGFβ/Smad pathway; pro-inflammatory cytokines; MMP-1; collagen | Cell experiments | [144] |

| 37 | Sacha inchi albumin extract | – | TGF/Smad pathway; TNF-α; IL-6; MDA | Mice model | [145] |

| 38 | Red bean extract | Caffeic acid, rutin, and rosmarinic acid | TGF-β1; MMP-1; IL-1β, −6, −8, CCL17/TARC and CCL22/MDC | Cell experiments | [146] |

| 39 | Prunella vulgaris L. extract | Polyphenols, vitamins, polysaccharides, amino acids, and alkaloids | TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway; MMPs, TNF-α and IL-6 | Cell experiments | [19] |

| 40 | Phyllanthus emblica L. fruit extract | homoplantaginin | ERK/TGF-β/Smad pathway; MAPK/AP-1 pathway; IL-1α,-6; PGE2; COX-2 | Cell experiments | [147] |

| 41 | Salvia plebeian extract | Rutin, glyceroclycolipids, kaempferolrutinoside, etc. | TGF-β/Smad pathway; MMP-1; IL-6 | Animal models and cell experiments | [148] |

| 42 | Panax notoginseng extract | Ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Re, Rg1, and notoginsenoside R1 | TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway; MMP-1; IL-6; COX-2 | Cell experiments | [149,150] |

| 43 | Acer tataricum subsp. Ginnala extract | Ginnalin A | TGFβ/Smad pathway; MMP1; TNF-α, IL-1β, −6 | Cell experiments | [151] |

| 44 | Astragalus and Radix Rehmanniae extract | Saponins, flavonoids and polysaccharides; catalpol, inosine, and echinacoside | TGFβ/Smad pathway; Ras/MAPK; collagens; TIMP-3; MMP-3 | Cell experiments | [37] |

| 45 | Rubus idaeus extract | Anthocyanins, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds | TGFβ/Smad pathway; MMPs; collagens; SOD; Nrf2; NF-κB; COX-2; MAPK | Cell experiments | [203] |

Table 4.

Natural Plants That Regulate Skin Inflammageing via the AMPK–Sirtuins and Other Signaling Pathways

| No. | Natural Plant/Compound | Plant Sources/Main Compounds | Mechanism of Action | Model of Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma extract | Cryptotanshinone, tanshinone and salvianolic acid B | AMPK/sirt1, AMPK/ULK1 signaling pathway; MMPs; ROS; IL-4, −10, −2, −6; IFN-γ; NF-κB p65; autophagy; MDA; CAT, Nrf2; NQO1; HO-1 | Mouse models and in vitro experiments | [152–158] |

| 47 | Youngia denticulata extract | Phenolic compounds | AMPK–sirtuins, AMPK/Nrf pathway; MMPs; TNF-α; COX-2; IL-6; p65; p50; autophagic | Cell experiments | [159–164] |

| 48 | Ginseng | Ginsenosides | LKB1/ AMPK/SIRT1 pathway; inflammatory factor; type I collagen; MMPs | Clinical Trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [46,165–170] |

| 49 | Almond Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A.Webb extract | Fatty acids, phytochemical polyphenols, VE and chlorogenic acid | AMPK–sirtuin pathway; COL1A1; COL1A2; TNF-α; hyaluronic acid synthase mRNA; GR signaling; MCP-1; CCL-5 | Clinical trial and cell experiments | [171–178] |

| 50 | Icariin | Epimedium | SIRT6; NF-κB | Mice model | [179] |

| 51 | Aronia melanocarpa extract | Phenolic compounds | AMPK/SIRT1/NF-κB, PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway; MMP-1, 3; immunoreactivity of collagen types I and III; pro-inflammatory mediators | Mice model and in vitro experiments | [117,180] |

| 52 | Crocus sativus extract | Polyphenols | SIRT1 | Clinical trial | [181] |

| 53 | Tinospora cordifolia extract | Alkaloids, terpenoids, sitosterols, flavonoids, and phenolic acids | AMPK–sirtuins signaling pathway; PI3K/AKT; IL-1α, −1β, −6, −8; IFN-γ; PGE-2; TNF-α | Mouse model | [182] |

| 54 | Peanut skin extract | Oligosaccharides and flavonoids | AMPK; MMP-3, −9; TRP-1; DPPH; MITF; Tyrosinase; Collagenase | Mice model and cell experiments | [183,184] |

| 55 | Hypericum perforatum extract | Hyperforin | AMPK mRNA; Il1; Il6; Il23; Il17a; Il22; antimicrobial peptides (AMPs); IL-6; IL-17A; TNF-α;MAPK/STAT3 | Mice model and cell experiments | [185,186] |

| 56 | Resveratrol | The skin of the grape, blueberry, raspberry, mulberry, and peanut. | AMPK; NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, TLR4/NF-κB/STAT3, NOTCH; Wnt signaling pathway; p53, p16, p19, NLRP3 and Cas1 p20; (MMP)-1, MMP-9, MMP3 and interleukin-8; CAT, GSH, SOD, MAPK-AP-1/NF-κB-TNF-α/IL-6, iNOS, COX-2-mediated inflammation-induced ageing; and p53-Bax-cleaved caspase-3-cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis induced ageing | Clinical trial; animal models and in vitro experiments | [39,187–189] |

| 57 | Echinacea purpurea L. Moench extract | Phenolic compounds | Complement system pathway; C3a/C3aR pathway; anti-collagenase, anti-elastase, anti-hyaluronidase activity | Animal models and in vitro experiments | [58,190] |

| 58 | Impatiens textori Miq. extract | Palmitoleic acid, palmitelaidic acid and methyl undecanoate | NLRP3 pathway; IL-1β; caspase-1 | Cell experiments | [191] |

| 59 | Piceatannol | Peanuts and grapes | JAK1/STAT3 pathway; Notch pathway; COX-2, iNOS, AP-1, MMP-1, IKKβ, MAPK, mTOR | Cell experiments | [192–194] |

| 60 | Houttuynia cordata Thunb. | Volatile oils, polysaccharides, and flavonoids | MAPK pathway | Cell experiments | [195,196] |

Inhibitor of the NF-κB/RIG-I Pathway

Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (CA) (Asian pennywort or Gotu kola) is widely used in Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine. This plant contains alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, and terpenoids, which exhibit anti-cancer, wound-healing, anti-bacterial, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects.197 The CA phytosome inhibits NF-κB activities, halts IκBα degradation, and reduces p65 and p50 nuclear translocation.64 CA extract in lotion form protects DNA from UV-induced damage, reducing thymine photodimerization by over 28% and downregulating IL-1α expression.65 A moisturizing lotion containing CA stem cell extract significantly improved skin moisture and barrier function for up to 24 h.66 Moreover, oral supplementation with CA (Centellicum®) effectively ameliorated cutaneous stretch marks over a relatively short period.67 These results indicate that CA extract is a potent modulator of skin inflammageing.

Punica granatum L. (pomegranate) extract, derived from a deciduous tree in the Lythraceae family, is recognized for its anti-inflammatory and anti-senescence properties, primarily through NF-κB pathway inhibition.68 Rich in compounds such as anthocyanins, catechin, ellagic acid, gallic acids, and other polyphenols,69 punicalagin from the extract mitigates UV-induced growth arrest in the ageing human fibroblast cell line HFB4, enhances Col1A1 and Timp3 gene expression, preserves collagen levels, and reduces MMP3.70 The primary dye in pomegranate arils, anthocyanins, decreased facial wrinkles in volunteers using a cold cream containing these compounds.71 Fermented pomegranate extracts have demonstrated improvements in skin moisture, brightness, elasticity, and collagen density after eight weeks, effectively preventing skin ageing.72 Thus, daily consumption of pomegranate extracts supports skin health by combating inflammation and decelerating the ageing process.

Quercetin is a promising anti-inflammageing agent, offering anti-inflammatory, anti-ageing, and antioxidant effects via the NF-κB pathway.12 Quercetin significantly reduces inflammatory cytokine production in primary human keratinocytes,73 decreases MDA levels in the skin tissues of psoriasis-like mice via NF-κB pathway inhibition,74 and directly targets PKCδ and JAK2, protecting against UV-induced skin ageing and inflammation.75 Quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucuronide (Q-3-G), a glucuronide conjugate of quercetin, has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, moisturizing, and anti-melanogenesis effects in human keratinocytes and melanoma cells because of NF-κB pathway modulations.76 Quercetin also downregulates pro-inflammatory genes and cytokines such as COX-2 and TNF-α in HaCaT cells and reduces melanin production in B16F10 cells,76 highlighting its potential as an effective anti-inflammageing compound.

Green tea’s primary polyphenolic catechin, Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), along with its structural isomer GCG and a compound containing digallate (specifically, theaflavin-3,3ʹ-digallate), exhibit robust inhibitory effects on RIG-I. At low micromolar concentrations, EGCG interacts with RIG-I in HEK293T cells, thereby suppressing RIG-I signaling. Furthermore, it dampens IL-6 secretion and IFN-β mRNA production in BEAS-2B cells.77 EGCG also mitigates UV-induced MMP-1 expression, exhibiting anti-ageing effects. EGCG treatment reduced UVA-induced skin damage, such as roughness and sagginess, and protected against decreases in dermal collagen in hairless mouse skin.78 Additionally, EGCG obstructed the UV-triggered escalation of collagen secretion and collagenase mRNA levels in fibroblast cultures.79 Potential plant-derived RIG-I pathway inhibitors include β-sitosterol,60 Abelmoschus manihot total flavones,198 Asphodelus microcarpus leaf extract,199 and berberine.200 Although direct evidence for improving skin inflammageing is lacking, these inhibitors show potential.

Phytochemicals such as luteolin,80 carotenoids,81,82 pterostilbene,83 myricetin,84 artemisinin,85 sulforaphane,86,87 Lithospermum erythrorhizon (Gromwell) root extract,88,89 Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker,90 and soy isoflavones91,201 are also beneficial for managing skin inflammageing. These compounds contribute to skin health by inhibiting the NF-κB/RIG-I signaling pathway, indicating their potential as therapeutic agents for promoting skin health and anti-ageing.

Inhibition of the mTOR Pathway

Cordyceps exert anti-ageing, anti-inflammation, and anti-oxidative stress effects, and their efficacy is attributed to their rich composition of active compounds, including cordyceps, nucleosides, polysaccharides, sterols, proteins, amino acids, polyphenols, and peptides.93 Cordyceps sinensis counters cigarette smoke extract-induced cellular senescence by inhibiting the ROS/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway;94 it also shields human skin cells from UV-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage.93,95 Cordyceps cicadae (Miq.) aqueous extract enhances HAS2 expression and reduces MMP-12 expression in human skin fibroblasts, demonstrating moisturizing and anti-ageing capabilities.96 Cordyceps medium-loaded nanoparticles prompted a significant 2.76-fold increase in skin regeneration in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) by upregulating ECM production (collagen and elastin synthesis) and repairing H2O2-induced cell damage.92 Cordyceps extract is an ideal topical solution for skin inflammageing as it mitigates inflammatory factor secretion, reduces cellular senescence, and boosts collagen synthesis.97

Curcumin, a phytochemical in turmeric, inhibits the phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, which are downstream targets of mTOR, in Rh1 and Rh30 cells. It mechanistically blocks mTOR by destabilizing mTORC1 through raptor dissociation at low concentrations and disrupts mTORC2 by detaching Rictor at higher concentrations.98 Curcumin and its metabolites have extended the lifespan of several ageing models, including C. elegans, D. melanogaster, yeast, and mice.99–101 Nano-formulated curcumin has a potential for anti-ageing and wound healing.99 Curcumin also inhibits the proliferation of differentiated HaCaT cells by reducing IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6 levels.100 A clinical study of 28 women in their 30s who used a turmeric-containing gel (Tricutan®) for four weeks reported improved skin firmness according to self-assessments.101 Turmeric hot water extract countered elevated TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA and protein levels induced by UVB in the skin of healthy subjects and led to increased hyaluronic acid production by keratinocytes, as well as enhanced facial skin hydration.102 Thus, curcumin has emerged as a potent anti-inflammageing agent and moisturizer.

Fisetin, a flavonol found in various fruits and vegetables such as strawberries, apples, persimmons, and onions, has also emerged as a potent anti-inflammageing agent. Recognized for its senolytic, antioxidant, and anti-proliferative properties, fisetin acts as a natural source of senolytics, offering a novel treatment for ageing.103 Fisetin also effectively addresses psoriasis and other inflammatory skin conditions by modulating the mTOR/IL-17A, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and autophagy pathways across several models.104,105 Moreover, fisetin suppresses cutaneous melanocytic lesions by targeting the Akt/mTOR signaling axis106 and inhibits α-MSH- and IBMX-induced melanosis in B16F10 melanoma cells, simultaneously upregulating mRNA for skin fibril-related genes.107 Furthermore, fisetin reduces MMP, ROS, PGE1, TNF-α, IL-6β, IL-53, and cyclooxygenase-2 expression, mitigating UVB-induced skin inflammation, DNA damage, wrinkles, and sunspots.108 Finally, fisetin enhances filaggrin expression, protecting against the UVB-induced disruption of barrier function.109

Anthocyanins, water-soluble flavonoid pigments from Sambucus canadensis, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.110 These compounds significantly mitigate cell senescence and lens ageing by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. This inhibition promotes the apoptosis of senescent cells, increases autophagic and mitophagic flux, and enhances mitochondrial renewal to maintain cellular homeostasis.111 Purple sweet potato (PSP) anthocyanins reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in rats with neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury,112 and extend the lifespan of D. melanogaster by activating autophagy via AKT-1, PI3K, and mTOR gene downregulation and 4E-BP upregulation, while increasing lysosome production and autophagy activation. Thus, PSP extract can be used to delay skin inflammageing.113 Furthermore, anthocyanins from pomegranates and grapes, as well as caffeic acid from various natural sources, inhibit mTORC1 by preventing the phosphorylation of S6K1 and AKT at the Ser473 residue mediated by mTORC1.114 Furthermore, mulberry anthocyanins reduce MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in the ECM of melanoma B16-F1 cells by targeting the Ras/MEK/ERK/mTOR pathway.115

A clinical trial showed that a phytocosmetic formulation containing Myrothamnus flabellifolia leaf extracts significantly improved skin ageing markers, including spot length, wrinkle area and volume, skin lightening, and homogeneity, by downregulating mTOR genes.116 Additionally, novel phytopeptides have shown efficacy in restoring cellular homeostasis, modulating oxidation, and hyperproliferation, thereby impacting the mTOR pathway.117 Peptides are favored over small-molecule drugs given their higher specificity and lower cytotoxicity, with plant-derived natural peptides having a long history of human consumption, indicating minimal potential adverse effects compared with synthetic or nonspecific therapeutics.117 Various natural plants and compounds, including Handelin from Chrysanthemum boreale flowers,118 Latifolin,119 Stigmasterol,120 α-,β-,γ-mangostins, isogarcinol, and gartanin from Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen),121–123 Momordica charantia L.,124 Isatis tinctoria L. leaf,125 Amaranthus cruentus L. seed oil,126 Mikania micrantha L.,127 and Nypa fruticans Wurmb,202 are potential modulators of skin inflammageing via the mTOR signaling pathway. However, further in vitro and in vivo studies are required to verify their effects.

Modulation of the TGF-β Signaling Pathway

Prunus yeonesis Matsum. (Rosaceae) is recognized for its anti-allergy, anti-ageing, and anti-inflammatory properties. The bark extract was traditionally used for treating coughs, urticaria, pruritus, dermatitis, asthma, and measles.129 Prunetin from P. yeonesis extract (PYE) exhibited anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages and an LPS-induced septic shock model.130 Polyphenols from the bark show high antioxidant activity, contributing to anti-ageing effects.131 Moreover, PYE at 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL enhanced type I procollagen production in UVB-irradiated normal HDFs via the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. This involved the upregulation of TGF-β1 by Smads and the downregulation of transcription activator protein-1 and MAP kinase, resulted in reduced MMP-1 and MMP-3 production.131 PYE also reduced nitric oxide secretion in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells. In an SLS-stimulated patch test, PYE showed lower visual and erythema scores compared with a placebo on days 5 and 9, indicating potent anti-inflammageing effects in vitro and in vivo.132 These qualities position PYE as a promising ingredient for skincare products.

Eucalyptus globulus L. (EG) (myrtle family) contains an essential oil in the leaves that is rich in compounds such as thymol, 1,8-cineole, linalool, limonene, and pinenes, and acclaimed for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. EG extract promotes collagen synthesis by modulating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, including the inhibition of negative Smad regulators. Treatment of UV-irradiated HDFs with 1 to 100 μg/mL EG extract resulted in decreased MMP and IL-6 expression, alongside increased TGF-β1 and type 1 procollagen levels. Additionally, this treatment prevented activation of the AP-1 transcription factor.128 Furthermore, EG essential oil and hydrodistillation residual water minimized the activation of senescence markers, such as β-galactosidase and MMPs, while increasing collagen type I expression and exerting strong anti-inflammatory effects by reducing nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory mediators.133 Therefore, EG extract shows potential as an anti-inflammageing substance.

Ellagic acid (EA), a polyphenolic compound found in numerous fruits (eg, raspberries, pomegranates, and plums), seeds (eg, walnuts and almonds), and vegetables, either exists in free form or as part of ellagitannins. EA exerts antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-ageing effects.134 Specifically, EA shields HaCaT cells and mice from photoageing by modulating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway (TGF-β1➔pSmad3➔Smad7).135 The topical application of 10 μmol/L EA to SKH-1 hairless mice, exposed to UV-B for eight weeks, significantly reduced skin wrinkles and UBV-induced inflammation, decreased IL-1β and IL-6 production, prevented inflammatory macrophage infiltration, and reduced ICAM-1 expression in UVB-irradiated keratinocytes and mouse epidermis.136 Moreover, EA boosts elastin and collagen production in HDFs.137 Chitosan-coated niosomes containing EA-modulated skin ageing-related genes (upregulating Col1A1, TERT, Timp3, and downregulating MMP3) in HFB4 cells, thereby protecting collagen levels and decelerating skin ageing.138

Pentacyclic triterpenoids from Terminalia arjuna may enhance in vitro TGF-β expression and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion, significantly increasing skin hydration, reducing transepidermal water loss, and improving skin elasticity.139,140 Oleracone C, derived from Portulaca oleracea mitigated UVB-induced MMP changes and type I pre-collagen production in human keratinocytes through the TGF-β/Smad pathway.141 Additionally, two compounds from P. oleracea extract, portulacanone A and portulacanone D, inhibited MMP-1 secretion and boosted type I procollagen production in UVB-stressed human keratinocytes, demonstrating potent anti-ageing effects.142 Fucosterol,143 Myricetin 3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside from extracts of Limonium tetragonum (Thunb.) Bullock,144 Sacha inchi albumin,145 red bean (Vigna angularis),146 Prunella vulgaris L.,19 Phyllanthus emblica L. fruit,147 Salvia plebeian,148 Panax notoginseng,149,150 Acer tataricum subsp. Ginnala,151 Astragalus and Radix Rehmanniae,37 and Rubus idaeus203 all showed efficacy in mitigating inflammageing-induced skin damage. These effects are mediated by modulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway, highlighting the potential of these compounds as therapeutic agents for skin health and anti-ageing.

Regulation of the AMPK–SIRTs Signaling Pathway

Danshen (Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma) is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine and exhibits extensive pharmacological benefits, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-ageing vasodilatory, lipid-lowering, and improved energy metabolism effects.153 The active compounds of danshen are primarily fat-soluble tanshinones, such as cryptotanshinone, and water-soluble tanshinone, notably salvianolic acid B.154 Cryptotanshinone enhances mitochondrial biosynthesis in skin cells via the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway, reducing skin ageing and extending the lifespan of budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, indicating its potential or delaying senescence.155 Cryptotanshinone also shows promise in dermatology, including psoriasis treatment,156 UV-induced melanoma mitigation,152 and scar formation reduction.157 Salvianolic acid B activates the AMPK/ULK1 pathway, enhancing the autophagic degradation of pS757-ULK1 and autophagic activity in astrocytes.152 Salvianolic acid B boosts autophagy, significantly increases Beclin1 expression, a marker of autophagy, and increases the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 B (LC3B) II/LC3B I ratio. Additionally, salvianolic acid B extends cell survival, enhances the release of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4, IL-10, IL-2, IL-6, and IFN-γ), and reduces apoptosis; it can also reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, which is attributed to activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 pathway.158 Thus, danshen extract represents a potential skin anti-inflammageing agent.

Youngia denticulata (YD, Asteraceae; synonym: Crepidiastrum denticulatum) is a traditional vegetable in Korea. YD extract contains phenolic compounds such as dicaffeoylquinic acid chicoric acid, youngiasides A, B, and C, showing anti-inflammatory, anti-ageing and antioxidant activity.159,160 These compounds decrease MMPs, including MMP-1, −2, −3, and −9, in HaCaT cells and HDFs, increase collagen production via the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway in HDFs, and inhibit NF-κB-mediated inflammation.161 Treatment with YD extract results in significant autophagic vesicle formation within the non-cytotoxic range and induces AMPK phosphorylation without mTOR inhibition.162 The role of autophagic signaling pathway in skin homeostasis has been thoroughly investigated.163 Besides its critical role in epidermal differentiation, autophagy contributes to skin barrier integrity, inflammation reduction, and ageing mitigation.164 Anti-pollution efficacy was evaluated using benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and cadmium chloride (CdCl2) as model compounds; the YD extract protected against cytotoxicity and effectively reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines,162 indicating its potential as an anti-inflammageing cosmetic ingredient.

Ginseng is a perennial herb of the Araliaceae family that is widely used in Asia. Its efficacy is attributed to triterpenoid saponins called ginsenosides, which are categorized into three groups, with microbial transformation producing their active metabolites. Notably, ginsenosides with two glucopyranosyl groups at the C-3 position are recognized as SIRT1 activators. These compounds target the SIRT1 signaling pathway, offering therapeutic potential against oxidative stress, inflammation, ageing, and depression.165 The ginsenoside metabolite 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol mitigates UV-induced MMP-1 expression in HDFs by enhancing liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and AMPK phosphorylation.166 Ginsenoside Rb1, by activating the SIRT1/AMPK pathway, diminishes endothelial cell senescence.46 Comprehensive clinical investigations have validated the anti-inflammageing benefits of ginseng extract on skin and the regulation of MMPs and type I collagen in human fibroblasts to augment skin elasticity and hydration.167 Additionally, ginsenoside Rb1 decreases IL-1β release at injury sites in mice, which mitigates inflammation.168 Ginseng extracts, as anti-ageing components, also enhance immunity and modulate inflammation.169 Herbal formulations with ginseng extract are leading natural candidates for innovative dermocosmetics exhibiting anti-ageing benefits for the skin.170

Almond (Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb), a leading nut crop globally, is a rich source of fatty acids, phytochemical polyphenols, and antioxidants, including vitamin E and chlorogenic acid. Almond bark polyphenol extract notably enhances AMPK phosphorylation and mitigates TNF-α-induced cellular inflammation by reducing the secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and chemokine ligand 5.171 This extract also prolongs the lifespan of yeast, possibly because it preserves mitochondrial function with age.172 β-Violanone from almond oil counters the suppression of dexamethasone-induced collagen and hyaluronic acid synthesis in HDFs.173 A study on skin massage with almond oil-infused essential oils indicated significant alleviation of itchiness and mental stress in 64 women (≥65 years old).174 Moreover, almond oil exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-ageing, wound-healing, and skin barrier-restoration effects 183,184. Topical almond oil and extract application diminishes UVB-induced photoageing both in vitro and in vivo.177 Furthermore, regular almond consumption can reduce facial wrinkles and pigment intensity in postmenopausal women.178

Natural compounds such as icariin179 and extracts of Aronia melanocarpa,117,180 Crocus sativus,181 Tinospora cordifolia,182 peanut skin,183,184 and Hypericum perforatum185,186 modulate AMPK signaling. The plant extracts and compounds reviewed in this study attenuate inflammatory senescence by regulating the AMPK–SIRTs pathway. SIRT enzymes have drawn significant interest for their pivotal role in anti-ageing. Thus, comprehensive research into the AMPK–SIRTs pathway and the molecular underpinnings of inflammageing highlights phytotherapies targeting this pathway as novel interventions for managing skin inflammageing.204

Regulation of Other Pathways

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a natural phenol found in grape, blueberry, raspberry, mulberry, and peanut skins, which exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-ageing properties.39 As the most potent Notch activator, resveratrol is thus capable of alleviating skin inflammageing damage,187 potentially by inducing cell death via the ROS-dependent inactivation of the Notch/PTEN/AKT cascade reaction.188 Resveratrol also inhibits mast cells, sphingosine kinase-1, STAT3, expression of senescence markers (p53, p16, and p19), inflammasome markers (NLRP3 and Cas1 p20), nuclear translocation of NF-κB, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-18, and activation of the NF-κB p65 signaling pathway.189

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench extract suppresses inflammation by inhibiting the C3a/C3aR signaling pathway in the complement system in TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis rats.58 E. purpurea extract exhibits significant anti-collagenase (78.5 ± 0.0%), anti-elastase (69.0 ± 1.4%), and anti-hyaluronidase activity (64.2 ± 0.3%).190 This extract may impede skin inflammageing by inhibiting the complement system.

Impatiens textori Miq. (Balsaminaceae) is a traditional medicinal herb used to treat inflammation-related skin infections and allergic disorders. The extracts demonstrate inhibitory effects on interleukin 1β secretion and reduce ASC oligomerization and caspase-1 maturation by attenuating NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which were observed at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL.191 Additionally, the extracts exhibited stimulatory effects on HaCaT cell proliferation, migration, sprout outgrowth, and the synthesis of types I and IV collagen.191 These extracts also alleviate the dulling effect of skin color that is characteristic of skin inflammageing.191 Furthermore, Myrothamnus flabellifolia leaf extracts and resveratrol can attenuate inflammageing damage to the skin by inhibiting NLRP3, as outlined in Table 1 for natural plants 19 and 56.

Piceatannol is a resveratrol metabolite commonly found in red wine grapes. It reduces atopic dermatitis by inhibiting JAK1 and decreasing JAK–STAT protein phosphorylation.192 It also inhibits MMP-1 expression via the JAK1/STAT3 pathway in keratinocytes. Piceatannol exhibits various effects on the skin, including promoting collagen production, inhibiting melanin synthesis, inducing the antioxidant glutathione, and eliminating ROS.193 A clinical trial showed that passion fruit seed extract, when taken orally, is rich in piceatannol and can improve the moisture levels of dry skin and reduce fatigue,194 implying that the compound has a skin inflammageing-prevention effect. Furthermore, EGCG, sulforaphane, stigmasterol, Hypericum perforatum extracts, and resveratrol can attenuate inflammageing damage to the skin by inhibiting STAT, as outlined in Tables 1, 2, and 4 for natural plants 5, 11, 23, 55, and 56.

Houttuynia cordata Thunb. (Saururaceae), a native perennial herb, contains many active compounds, including volatile oils, water-soluble polysaccharides, and flavonoids, and exhibits antioxidant, anti-ageing, and anti-inflammatory activities.195 The hyperoside-enriched fraction obtained from H. cordata inhibits skin ageing by regulating the MAPK signaling pathway and attenuating JNK/ERK/c-Jun activation in HDFs.196 Furthermore, extracts of Isatis tinctoria L. leaves, Nypa fruticans Wurmb, seaweed, Phyllanthus emblica L. fruit, Astragalus and Radix Rehmanniae, Rubus idaeus, Hypericum perforatum, and piceatannol can attenuate skin inflammageing damage by inhibiting MAPK, as outlined in Tables 2–4 for natural plants 26, 29, 35, 40, 44, 45, 55, and 59.

Conclusion

Chronic low-level inflammation contributes to ageing and age-related degenerative diseases, which manifest outwardly as skin ageing, including wrinkles, sagging, thinning, and pigmentation changes. This review explores the mechanisms of skin inflammageing, focusing on nine critical signaling pathways: NF-κB/RIG-I, mTOR, TGF-β, AMPK–SIRTs, complement system, NLRP3, Notch, JAK–STAT, and MAPK. In the natural environment, the process of skin inflammageing is marked by complexity, involving intricate interactions among multiple signaling pathways. Notably, the NF-κB signaling pathway intersects with MAPK, PI3K, and TGF-β pathways to collectively regulate this inflammageing process in the skin. AMPK can regulate AMPK/mTOR pathways, which relieve neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain.42 Additionally, this review highlights how various natural plant extracts and monomers impact skin inflammageing through these pathways. Due to their diverse composition, plant extracts exhibit unparalleled advantages in addressing multiple interventions concurrently. This research therefore strengthens our understanding of skin inflammageing mechanisms and identifies promising natural interventions against skin inflammageing, as well as key directions for future research. Unfortunately, few natural plants modulate Notch, the complement system, NLRP3, JAK–STAT, or MAPK pathways. This requires more attention from relevant researchers on the botanical regulators of these pathways, to determine their effectiveness and safety in more skin inflammageing related in vitro and animal models, detailed, well-controlled and larger scale dose-response randomized clinical trials. Limited in-depth animal and clinical studies exist on the regulatory effects of plants extracts, such as Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench, on skin inflammageing via the complement system or other signaling pathways. Further investigation by relevant researchers is warranted. Therefore, future research should explore active substances that affect inflammageing in the identified plant species to promote further development in this field. Given the complex compositions and mechanisms of action of natural plants, clinical trials are required to evaluate their actual effects, safety, and effectiveness. Additionally, the use of natural molecules derived from plant extracts to modulate skin inflammageing is a promising area for future exploration. Elucidating the effects of these natural plant extracts and active chemical monomers on the prevention of skin inflammageing will also enrich the library of raw materials available for treating skin inflammageing. Future research should also aim to discover new natural plants that offer more possibilities for counteracting skin inflammageing damage.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Yunnan Characteristic Plant Extraction Laboratory, grant number 2022YKZY001 and 2022YKZY006.

Abbreviations

NF-κB/RIG-I, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells/retinoic acid-inducible gene I; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; JAK, janus kinase; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL, interleukin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ATM-IRF1, Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated-interferon regulatory factor 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-Kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; Ras, the renin-angiotensin system; Raf, serine/threonine kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; Rsk, ribosomal S6 kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RhoA, ras homolog family member A gene; Rock, Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase; LAP, latency associated peptide; AP-1, activator protein-1; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; LKB-1, liver kinase B1; FoxO, forkhead Box O; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha; P53, tumor protein P53; NICD, Notch Intracellular Domain; GSDMD, gasdermin D; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; ECM, extracellular matrix; ECM, extracellular matrix; HDF, human dermal fibroblast; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Baechle JJ, Chen N, Makhijani P, Winer S, Furman D, Winer DA. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of ageing. Mol Metabol. 2023;74:101755. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2023.101755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung HY, Kim DH, Lee EK, et al. Redefining chronic inflammation in ageing and age-related diseases: proposal of the senoinflammation concept. Ageing Dis. 2019;10(2):367–382. doi: 10.14336/AD.2018.0324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammageing and anti-inflammageing: a systemic perspective on ageing and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilkington SM, Bulfone-Paus S, Griffiths CEM, Watson REB. Inflammageing and the Skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(4s):1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabowska K, Nowacka-Chmielewska M, Barski J, Liskiewicz D. Inflammageing - contributing mechanisms and cellular signaling pathways. Postepy Biochem. 2021;67(2):177–192. doi: 10.18388/pb.2021_375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pająk J, Nowicka D, Szepietowski JC. Inflammageing and immunosenescence as part of skin ageing-A narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijms24097784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quillard T, Charreau B. Impact of notch signaling on inflammatory responses in cardiovascular disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(4):6863–6888. doi: 10.3390/ijms14046863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awad F, Assrawi E, Louvrier C, et al. Photoaging and skin cancer: is the inflammasome the missing link? Mech Ageing Dev. 2018;172:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer EC, Thielen AJ, Langereis JD, et al. The contribution of the alternative pathway in complement activation on cell surfaces depends on the strength of classical pathway initiation. Clin Transl Immunol. 2023;12(1):e1436. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solimani F, Meier K, Ghoreschi K. Emerging topical and systemic JAK inhibitors in dermatology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2847. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu HM, Cheng MY, Xun MH, et al. Possible mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced skin cellular senescence, inflammation, and cancer and the therapeutic potential of plant polyphenols. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Li C, Zhang W, Wang Y, Qian P, Huang H. Inflammation and ageing: signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):239. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01502-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbas H, Kamel R, El-Sayed N. Dermal anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-ageing effects of compritol ATO-based resveratrol colloidal carriers prepared using mixed surfactants. Int J Pharm. 2018;541(1–2):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fougère B, Boulanger E, Nourhashémi F, Guyonnet S, Cesari M. Chronic inflammation: accelerator of biological ageing. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(9):1218–1225. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JE, Lee KW. Molecular targets of phytochemicals for skin inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(14):1533–1550. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666180426113247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang Y, Lyga J, Targets AD. Inflammageing in skin and other tissues - The roles of complement system and macrophage. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2014;13:153–161. doi: 10.2174/1871528113666140522112003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giunta S, Wei Y, Xu K, Xia S. Cold-inflammageing: when a state of homeostatic-imbalance associated with ageing precedes the low-grade pro-inflammatory-state (inflammageing): meaning, evolution, inflammageing phenotypes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2022;49(9):925–934. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bektas A, Schurman SH, Sen R, Ferrucci L. Human T cell immunosenescence and inflammation in ageing. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102(4):977–988. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RI0716-335R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Hwang E, Lin P, Gao W, Ngo HTT, Yi TH. Prunella vulgaris L. exerts a protective effect against extrinsic ageing through NF-κB, MAPKs, AP-1, and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways in UVB-aged normal human dermal fibroblasts. Rejuvenation Res. 2018;21(4):313–322. doi: 10.1089/rej.2017.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rovillain E, Mansfield L, Caetano C, et al. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B signalling promotes cellular senescence. Oncogene. 2011;30(20):2356–2366. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawamura T, Ogawa Y, Aoki R, Shimada S. Innate and intrinsic antiviral immunity in skin. J Dermatological Sci. 2014;75(3):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu F, Gu J. Retinoic acid inducible gene-I, more than a virus sensor. Protein Cell. 2011;2(5):351–357. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1045-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu H, Li Q, Huang Q, et al. RIG-I contributes to keratinocyte proliferation and wound repair by inducing TIMP-1 expression through NF-κB signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238(8):1876–1890. doi: 10.1002/jcp.31049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Wu S, Ren H, Gu J. Klotho suppresses RIG-I-mediated senescence-associated inflammation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(3):254–262. doi: 10.1038/ncb2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng Y, Wang PH, Zhang M, Du JR. ageing-related renal injury and inflammation are associated with downregulation of Klotho and induction of RIG-I/NF-κB signaling pathway in senescence-accelerated mice. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0371-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Eming SA, Ding X. Role of mTOR signaling cascade in epidermal morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Biology. 2022;11(6):931. doi: 10.3390/biology11060931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leo M, Sivamani RK. Phytochemical modulation of the Akt/mTOR pathway and its potential use in cutaneous disease. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306(10):861–871. doi: 10.1007/s00403-014-1480-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(8):1049–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fok WC, Zhang Y, Salmon AB, et al. Short-term treatment with rapamycin and dietary restriction have overlapping and distinctive effects in young mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(2):108–116. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tominaga K, Suzuki HI. TGF-β signaling in cellular senescence and ageing-related pathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5002. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bora NS, Mazumder B, Mandal S, et al. Amelioration of UV radiation-induced photoageing by a combinational sunscreen formulation via aversion of oxidative collagen degradation and promotion of TGF-β-Smad-mediated collagen production. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;127:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ke Y, Wang XJ. TGFβ signaling in photoageing and UV-induced skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(4s):1104–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikegami K, Yamashita M, Suzuki M, et al. Cellular senescence with SASP in periodontal ligament cells triggers inflammation in ageing periodontal tissue. Ageing. 2023;15(5):1279–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendoza MC, Er EE, Blenis J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36(6):320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang HW, Lan Y, Li A, et al. Myricetin suppresses TGF-β-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1288883. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1288883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quan T, Shao Y, He T, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Reduced expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) mediates collagen loss in chronologically aged human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(2):415–424. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Fong CC, Yu WK, et al. Herbal formula astragali radix and rehmanniae radix exerted wound healing effect on human skin fibroblast cell line Hs27 via the activation of transformation growth factor (TGF-β) pathway and promoting extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Phytomedicine. 2012;20(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(2):121–135. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ido Y, Duranton A, Lan F, Weikel KA, Breton L, Ruderman NB. Resveratrol prevents oxidative stress-induced senescence and proliferative dysfunction by activating the AMPK-FOXO3 cascade in cultured primary human keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0115341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crane ED, Wong W, Zhang H, O’Neil G, Crane JD. AMPK Inhibits mTOR-driven keratinocyte proliferation after skin damage and stress. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(9):2170–2177.e2173. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bharath LP, Agrawal M, McCambridge G, et al. Metformin enhances autophagy and normalizes mitochondrial function to alleviate ageing-associated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020;32(1):44–55.e46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiang HC, Lin LX, Hu XF, et al. AMPK activation attenuates inflammatory pain through inhibiting NF-κB activation and IL-1β expression. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1411-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desjardins EM, Smith BK, Day EA, et al. The phosphorylation of AMPKβ1 is critical for increasing autophagy and maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis in response to fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(48):e2119824119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119824119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Liu Y, Jiang K, Wen Z, Cao X, Wu S. Linear ubiquitination of LKB1 activates AMPK pathway to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome response and reduce chondrocyte pyroptosis in osteoarthritis. J Orthop Transl. 2023;39:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2022.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadria M, Layton AT. Interactions among mTORC, AMPK and SIRT: a computational model for cell energy balance and metabolism. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00706-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng Z, Wang M, Cheng C, et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 reduces H2O2-induced HUVEC dysfunction by stimulating the sirtuin-1/AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(1):247–256. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker KA, Basisty N, Wilson DM, Ferrucci L. connecting ageing biology and inflammation in the omics era. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(14). doi: 10.1172/JCI158448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JH, Moon JH, Lee YJ, Park SY. SIRT1, a class III histone deacetylase, regulates LPS-induced inflammation in human keratinocytes and mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of hinokitiol. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(6):1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siebel C, Lendahl U. Notch signaling in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(4):1235–1294. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Li X, Xing X, et al. Notch-Hes1 Signaling regulates IL-17A(+) γδ (+)T cell expression and IL-17A secretion of mouse psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020:8297134. doi: 10.1155/2020/8297134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshioka H, Yamada T, Hasegawa S, et al. Senescent cell removal via JAG1-NOTCH1 signalling in the epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2021;30(9):1268–1278. doi: 10.1111/exd.14361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang Y, Xu W, Zhou R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(9):2114–2127. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00740-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shim DW, Cho HJ, Hwang I, et al. Intracellular NAD(+) depletion confers a priming signal for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:765477. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.765477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González-Dominguez A, Montañez R, Castejón-Vega B, et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome improves lifespan in animal murine model of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(10):e14012. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elieh Ali Komi D, Shafaghat F, Kovanen PT, Meri S. Mast cells and complement system: ancient interactions between components of innate immunity. Allergy. 2020;75(11):2818–2828. doi: 10.1111/all.14413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chehoud C, Rafail S, Tyldsley AS, Seykora JT, Lambris JD, Grice EA. Complement modulates the cutaneous microbiome and inflammatory milieu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(37):15061–15066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307855110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santoro A, Bientinesi E, Monti D. Immunosenescence and inflammageing in the ageing process: age-related diseases or longevity? Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101422. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu D, Wang H, Yan M, et al. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench extract suppresses inflammation by inhibition of C3a/C3aR signaling pathway in TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;307:116221. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu W, Chen F, Feng X, Shang J, Luo X, Chen Y. Potential role of inflammageing mediated by the complement system in enlarged facial pores. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2024;23(1):27–32. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou BX, Li J, Liang XL, et al. β-sitosterol ameliorates influenza A virus-induced proinflammatory response and acute lung injury in mice by disrupting the cross-talk between RIG-I and IFN/STAT signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(9):1178–1196. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0403-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doles J, Storer M, Cozzuto L, Roma G, Keyes WM. Age-associated inflammation inhibits epidermal stem cell function. Genes Dev. 2012;26(19):2144–2153. doi: 10.1101/gad.192294.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng Y, Chen J, Shi Y, Fang X, Tang Z. MAPK signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma: biological function and targeted therapy. Cancers. 2022;14(19):4625. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mavrogonatou E, Konstantinou A, Kletsas D. Long-term exposure to TNF-α leads human skin fibroblasts to a p38 MAPK- and ROS-mediated premature senescence. Biogerontology. 2018;19(3–4):237–249. doi: 10.1007/s10522-018-9753-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ju Ho P, Jun Sung J, Ki Cheon K, Jin Tae H. Anti-inflammatory effect of Centella asiatica phytosome in a mouse model of phthalic anhydride-induced atopic dermatitis. Phytomedicine. 2018;43:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maramaldi G, Togni S, Franceschi F, Lati E. Anti-inflammageing and antiglycation activity of a novel botanical ingredient from African biodiversity (Centevita™). Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2014;7:1–9. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S49924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Milani M, Sparavigna A. The 24-hour skin hydration and barrier function effects of a hyaluronic 1%, glycerin 5%, and Centella asiatica stem cells extract moisturizing fluid: an intra-subject, randomized, assessor-blinded study. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2017;10:311–315. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S144180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu S, Belcaro G, Hosoi M, Feragalli B, Luzzi R, Dugall M. Postpartum stretchmarks: repairing activity of an oral Centella asiatica supplementation (Centellicum®). Minerva Ginecologica. 2018;70(5):629–634. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4784.18.04254-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman MM, Islam MR, Akash S, et al. Pomegranate-specific natural compounds as onco-preventive and onco-therapeutic compounds: comparison with conventional drugs acting on the same molecular mechanisms. Heliyon. 2023;9(7):e18090. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saeed M, Naveed M, Bibi J, et al. The promising pharmacological effects and therapeutic/medicinal applications of Punica Granatum L. (Pomegranate) as a functional food in humans and animals. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2018;12:24–38. doi: 10.2174/1872213X12666180221154713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mohamad EA, Aly AA, Khalaf AA, et al. Evaluation of natural bioactive-derived punicalagin niosomes in skin-ageing processes accelerated by oxidant and ultraviolet radiation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:3151–3162. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S316247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 71.Abdellatif AAH, Alawadh SH, Bouazzaoui A, Alhowail AH, Mohammed HA. Anthocyanins rich pomegranate cream as a topical formulation with anti-ageing activity. J Dermatol Treat. 2021;32(8):983–990. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1721418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chan LP, Tseng YP, Liu C, Liang CH. Fermented pomegranate extracts protect against oxidative stress and ageing of skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(5):2236–2245. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]