Abstract

Background

Achieving informed consent is a core clinical procedure and is required before any surgical or invasive procedure is undertaken. However, it is a complex process which requires patients be provided with information which they can understand and retain, opportunity to consider their options, and to be able to express their opinions and ask questions. There is evidence that at present some patients undergo procedures without informed consent being achieved.

Objectives

To assess the effects on patients, clinicians and the healthcare system of interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive healthcare treatments and procedures.

Search methods

We searched the following databases using keywords and medical subject headings: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 5, 2012), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to July 2011), EMBASE (OvidSP) (1980 to July 2011) and PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to July 2011). We applied no language or date restrictions within the search. We also searched reference lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials and cluster randomised trials of interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive healthcare procedures. We considered an intervention to be intended to promote informed consent when information delivery about the procedure was enhanced (either by providing more information or through, for example, using new written materials), or if more opportunity to consider or deliberate on the information was provided.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors assessed the search output independently to identify potentially‐relevant studies, selected studies for inclusion, and extracted data. We conducted a narrative synthesis of the included trials, and meta‐analyses of outcomes where there were sufficient data.

Main results

We included 65 randomised controlled trials from 12 countries involving patients undergoing a variety of procedures in hospitals. Nine thousand and twenty one patients were randomised and entered into these studies. Interventions used various designs and formats but the main data for results were from studies using written materials, audio‐visual materials and decision aids. Some interventions were delivered before admission to hospital for the procedure while others were delivered on admission.

Only one study attempted to measure the primary outcome, which was informed consent as a unified concept, but this study was at high risk of bias. More commonly, studies measured secondary outcomes which were individual components of informed consent such as knowledge, anxiety, and satisfaction with the consent process. Important but less commonly‐measured outcomes were deliberation, decisional conflict, uptake of procedures and length of consultation.

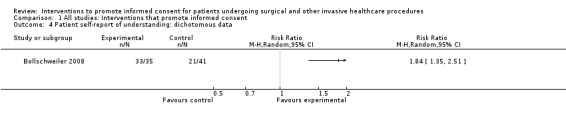

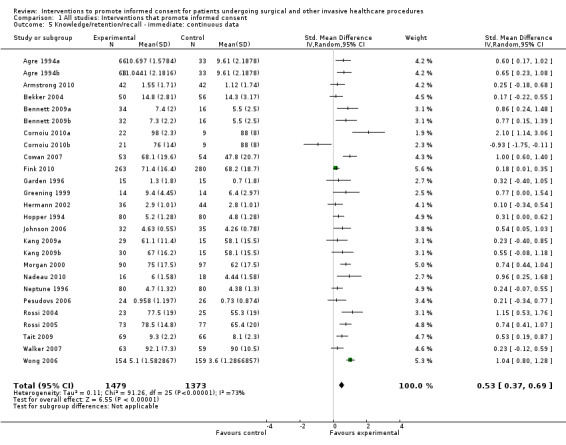

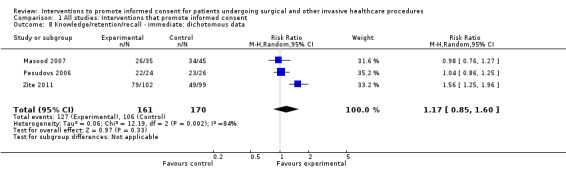

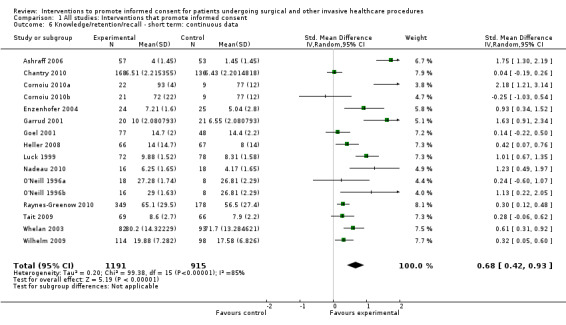

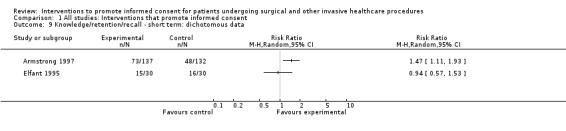

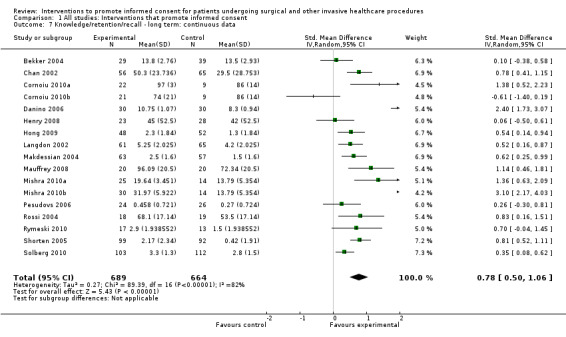

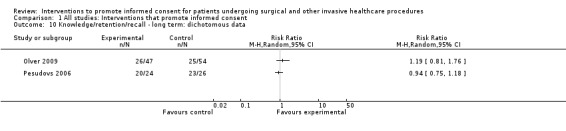

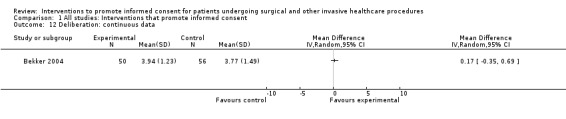

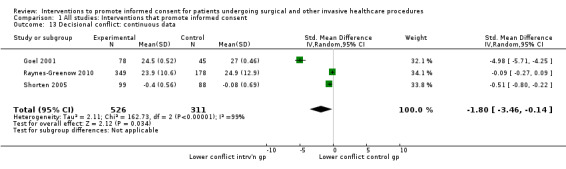

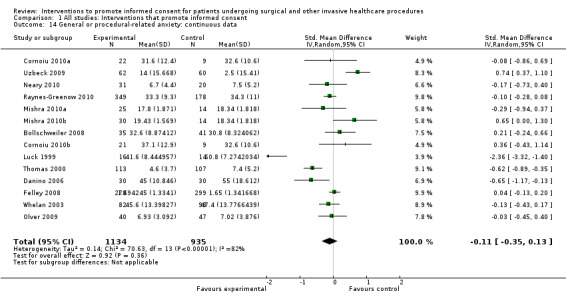

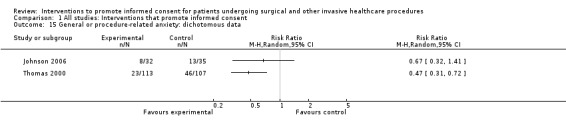

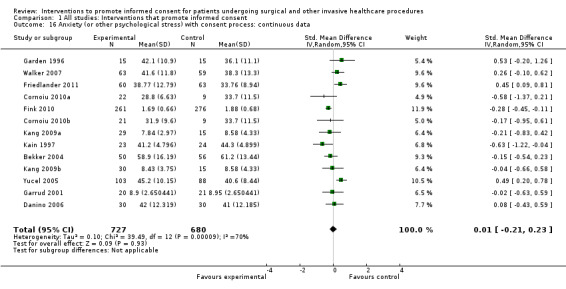

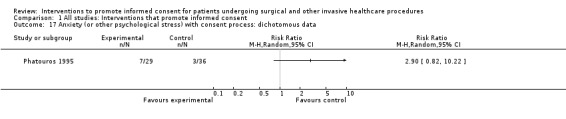

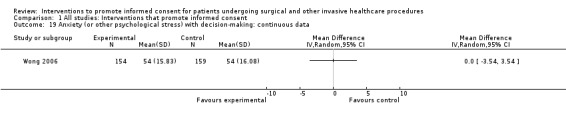

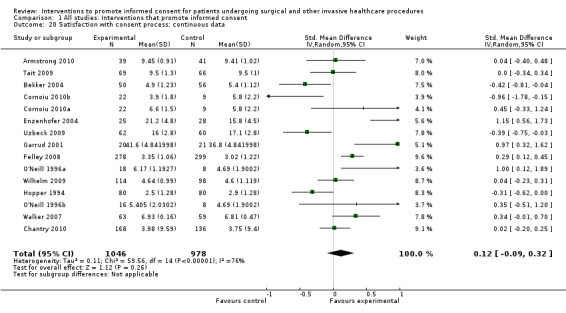

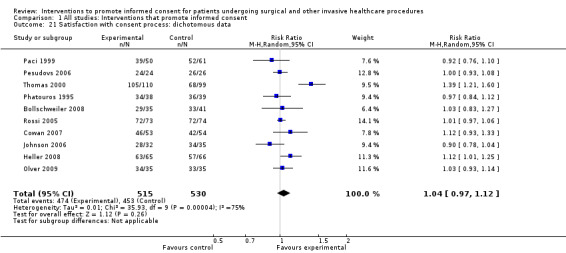

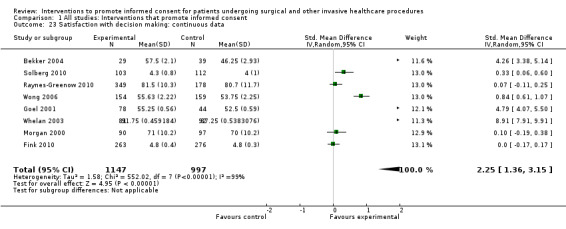

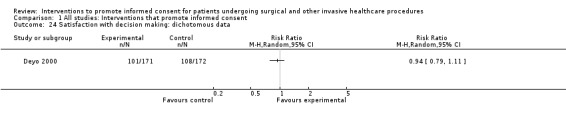

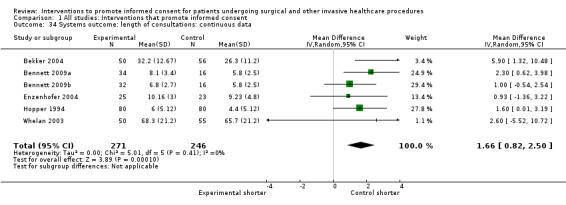

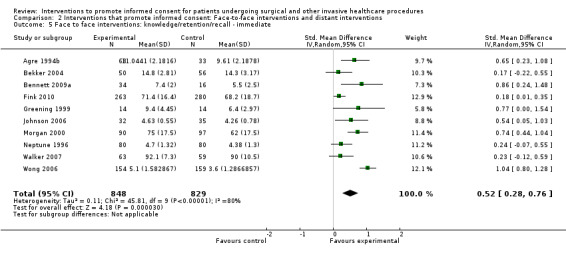

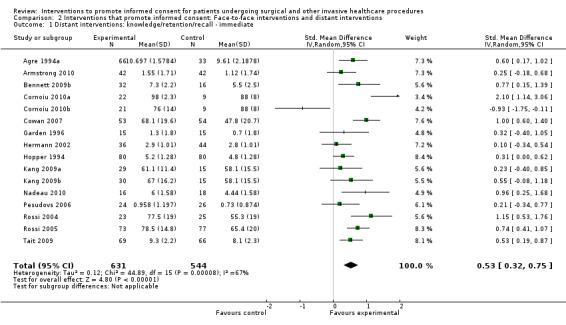

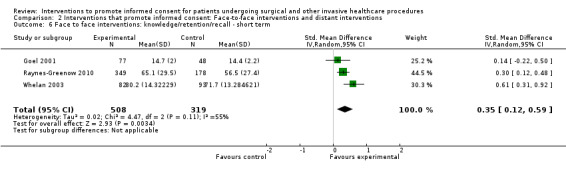

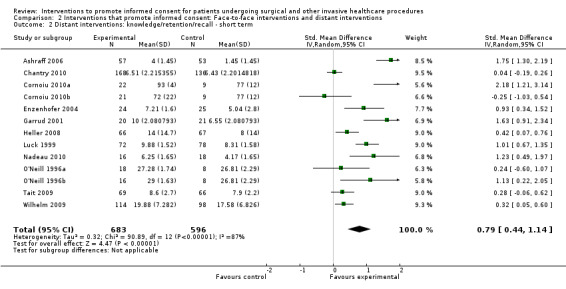

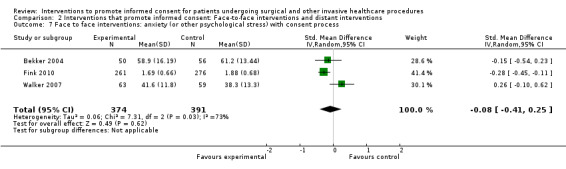

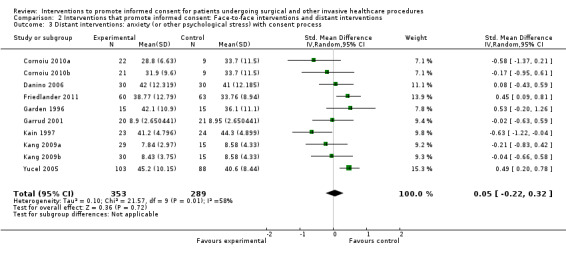

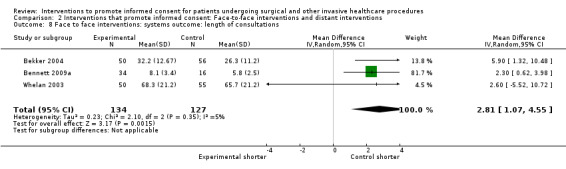

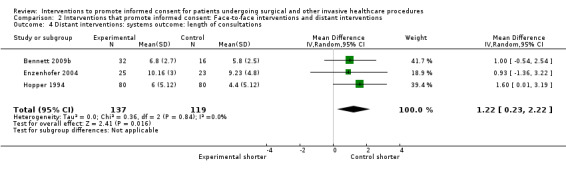

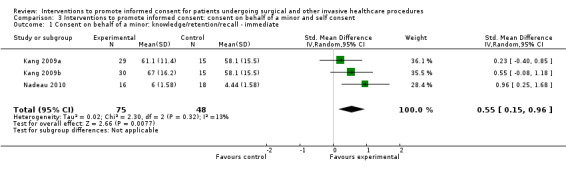

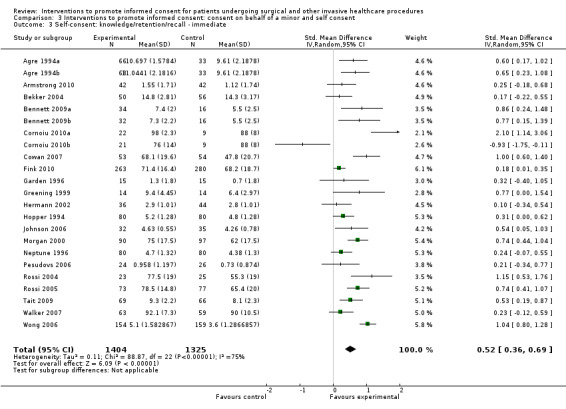

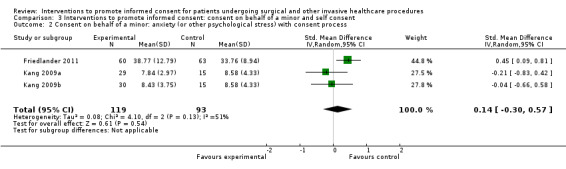

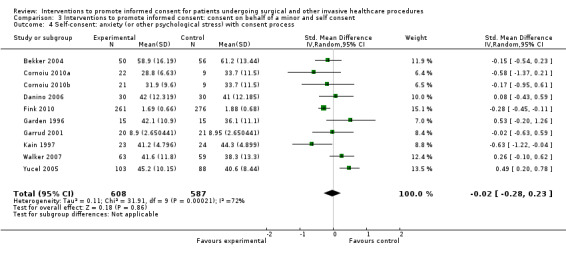

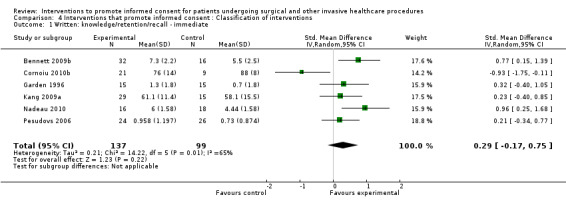

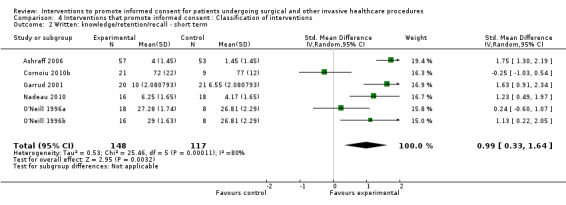

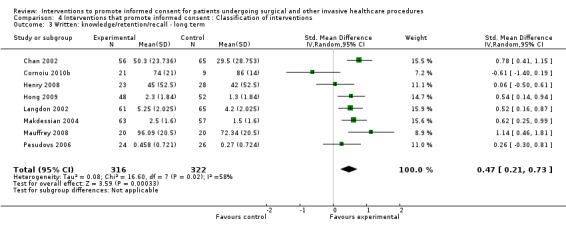

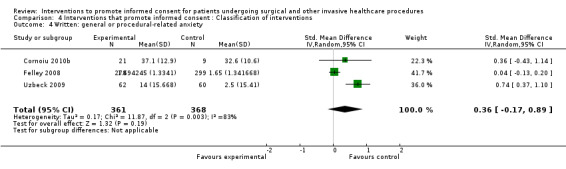

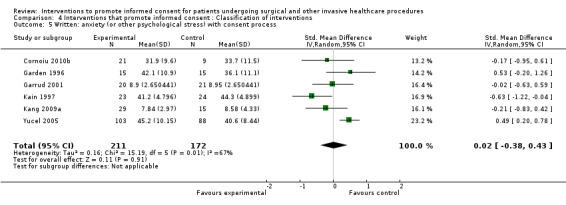

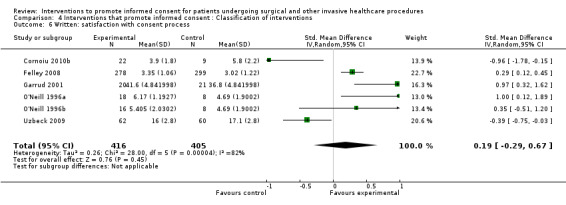

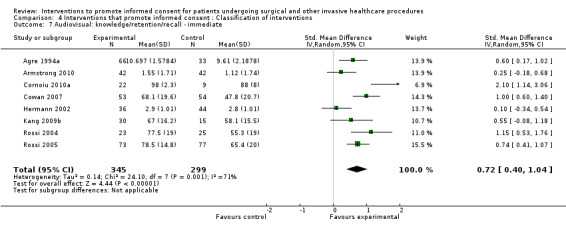

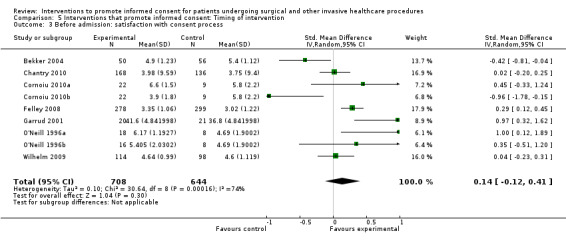

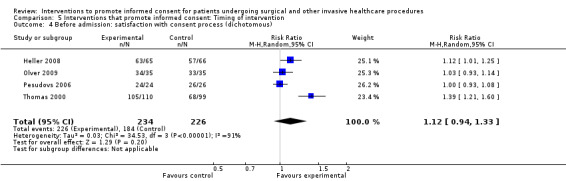

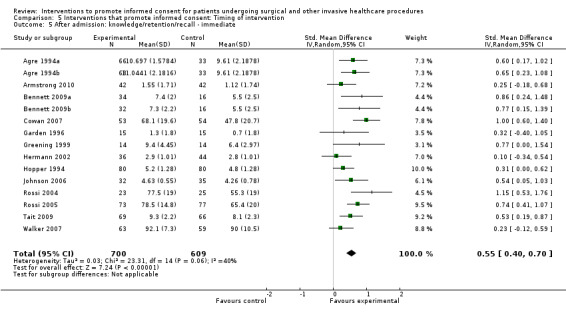

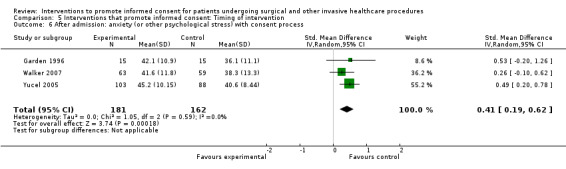

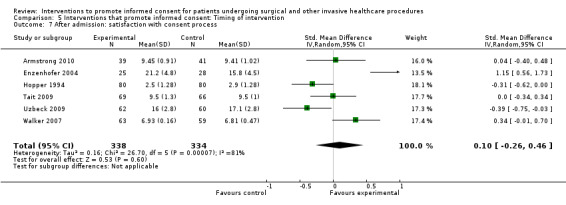

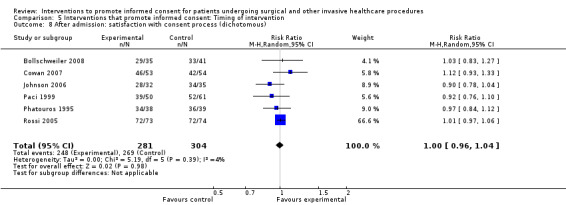

Meta‐analyses showed statistically‐significant improvements in knowledge when measured immediately after interventions (SMD 0.53 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.69) I2 73%), shortly afterwards (between 24 hours and 14 days) (SMD 0.68 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.93) I2 85%) and at a later date (15 days or more) (SMD 0.78 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.06) I2 82%). Satisfaction with decision making was also increased (SMD 2.25 (95% CI 1.36 to 3.15) I2 99%) and decisional conflict was reduced (SMD ‐1.80 (95% CI ‐3.46 to ‐0.14) I2 99%). No statistically‐significant differences were found for generalised anxiety (SMD ‐0.11 (95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.13) I2 82%), anxiety with the consent process (SMD 0.01 (95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.23) I2 70%) and satisfaction with the consent process (SMD 0.12 (95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.32) I2 76%). Consultation length was increased in those studies with continuous data (mean increase 1.66 minutes (95% CI 0.82 to 2.50) I2 0%) and in the one study with non‐parametric data (control 8.0 minutes versus intervention 11.9 minutes, interquartile range (IQR) of 4 to 11.9 and 7.2 to 15.0 respectively). There were limited data for other outcomes.

In general, sensitivity analyses removing studies at high risk of bias made little difference to the overall results.

Authors' conclusions

Informed consent is an important ethical and practical part of patient care. We have identified efforts by researchers to investigate interventions which seek to improve information delivery and consideration of information to enhance informed consent. The interventions used consistently improve patient knowledge, an important prerequisite for informed consent. This is encouraging and these measures could be widely employed although we are not able to say with confidence which types of interventions are preferable. Our results should be interpreted with caution due to the high levels of heterogeneity associated with many of the main analyses although we believe there is broad evidence of beneficial outcomes for patients with the pragmatic application of interventions. Only one study attempted to measure informed consent as a unified concept.

Keywords: Humans; Surgical Procedures, Operative; Decision Support Techniques; Endoscopy; Informed Consent; Informed Consent/statistics & numerical data; Pamphlets; Patient Education as Topic; Patient Education as Topic/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Teaching Materials

Plain language summary

Interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive healthcare procedures

Before patients have an operation or other invasive procedure (e.g. endoscopy) it is crucial for the healthcare professional to explain what the treatment involves, what alternatives exist and the risks and benefits of the different treatment options. This process is known as ‘informed consent’ and aims to provide sufficient information to allow patients to understand their treatment options and to choose between them.

Research suggests that when informed consent is obtained, the information provided by healthcare professionals is often unclear or insufficient, leading to misunderstanding, a worse treatment response and even litigation. A number of interventions have been developed to improve the quality of information provided to patients, including written pamphlets, videos and websites. It is unclear whether these interventions work in clinical practice.

In this review we summarise studies of interventions designed to improve information delivery or to improve consideration of information for informed consent.

We searched the scientific literature to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions designed to improve informed consent in clinical practice. We wanted to determine primarily whether these interventions improved all components of ‘informed consent’ (understanding, deliberation and communication of decision). Other individual outcomes of direct relevance to patients (e.g. recall/knowledge, understanding, satisfaction and anxiety), those related to healthcare professionals (e.g. ease of use of intervention, satisfaction) and system outcomes (e.g. cost, rates of procedural uptake) were also assessed.

We included 65 studies involving a total of 9021 patients. The studies varied according to the type of intervention, the procedure for which consent was sought, the clinical setting and the outcomes measured. Most interventions were written or audio‐visual. Only one study assessed all the elements of informed consent, but the design was not robust; all other studies assessed only components of informed consent. When the results of multiple studies were combined, we found that interventions improved knowledge of the planned procedure, immediately (up to 24 hours), in the short term (1 to 14 days) and the long term (more than 14 days). Satisfaction with decision making was increased; decisional conflict was reduced; and consultation length may be increased. There were no differences between the intervention and control for the outcomes of generalised anxiety, and either anxiety or satisfaction associated with the consent process.

Limitations of the review include difficulties combining the results of studies due to variation in the procedures undergone by patients, the interventions used and outcomes measured. This means that we are uncertain as to which specific interventions are most effective but pragmatic steps to improve information delivery and consideration of the information are likely to benefit patients.

Background

Description of the condition

Before many healthcare procedures can be undertaken, there is an accepted legal and ethical principle that a suitably‐trained clinician must obtain informed consent from the patient (or consumer). Obtaining informed consent usually requires a discussion between clinician and patient about a surgical or invasive healthcare intervention which results in the patient understanding what the procedure will involve, the risks and benefits of the procedure and their likelihood, and alternative management options, and then agreeing (or declining) to undergo the procedure. The process of achieving informed consent may occur as a single event or over a series of encounters and discussions in outpatient clinics or, for inpatients, on hospital wards. The consent discussion may be supported to a greater or lesser degree by the provision of comprehensive written, video or web‐based information. However it is achieved, it is most clearly shown as concluding when the patient signs a consent form.

Patients are usually required to give consent for a procedure because, while the intention of the procedure is to diagnose or improve their health, there is a risk of injury or other negative outcomes. The most common use of consent relates to surgical procedures but it is also important for a range of other interventions to investigate or treat diseases. Examples include: diagnostic interventions, for example endoscopy, bronchoscopy and angiography; procedures associated with childbirth and pregnancy, for example delivery by caesarean section, amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling; and curative procedures, for example chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Consent is usually required for all procedures where the patient is under general anaesthetic, although there may not be a requirement to seek consent for the anaesthetic itself. In emergencies, or when the patient is too ill to provide written consent, clinicians are still expected to seek the oral consent of the patient and document this. In such circumstances they may also seek the consent of a relative or other delegate. Clinicians are also required to seek the consent of a relative or delegate if the patient is under 16 years old, or if the patient is not capable of giving informed consent due, for example, to intellectual disability. If it is not possible to seek consent, for example because the patient is unconscious and no relatives or other delegates are available, clinicians are expected to exercise their judgement and act in the patient's best interests. Clinical trials or research procedures require additional consent, by which the patient confirms their agreement to take part in clinical research. This form of consent (consent for research studies) is excluded from this review and is discussed in other reviews (Ryan 2009;Hon 2012).

The signed consent form is frequently used as evidence of informed consent. However, this is often an oversimplification since there is a risk of acquiescence by a patient who may not be fully informed. For consent to be valid it must be given voluntarily by a patient who has the capacity to consent to the intervention in question and who has done each of the following:

Understood the information provided;

Retained that information long enough to be able to make the decision;

Weighed up the information as part of the decision‐making process; and

Communicated their decision (DoH 2009).

These requirements for informed consent are supported by Marteau who described a model to measure informed choice with regard to antenatal screening (Marteau 2001). This involves assessing the patient's knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. This model aims to measure the patient's knowledge (for example of antenatal screening), their attitude towards the screening (either positive or negative), and whether their behaviour (uptake or refusal of the test) is consistent with their attitudes.

Regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council, British Medical Association and Department of Health in the United Kingdom (UK), the American Medical Association and the Australian Medical Council provide guidance for clinicians about the information they should discuss with the patient during the informed consent process (AMA 2009; AMC 2009; BMA 2009; DoH 2001DoH 2009; GMC 2008). Information that should be discussed includes the intended benefits and risks and their likelihood, and the alternative options including doing nothing.

There are three standards of disclosure (or information provision) which may be applied when discussing the risks associated with surgical or invasive healthcare procedures:

The ‘professional standard’: a physician is to provide information that a physician of good standing in the physician’s community of peers would provide to his or her patient.

The ‘reasonable person standard’: a physician is to provide that information that a hypothetical reasonable person in the position of the patient would want to know.

The ‘subjective person standard’: a physician is to provide that information that the particular individual patient in question would want to know (Mazur 2009).

Failure to achieve fully‐informed consent has led to a number of legal judgements which have clarified the interpretation of consent with particular emphasis on the provision of information. In Chester v Afshar, a UK case concerning the risks associated with spinal surgery, the House of Lords held that a failure to warn a patient of the risk of injury inherent in surgery, however small the probability, denies the patient the chance to make fully‐informed decisions (Chester v Afshar 2004; DoH 2009). In the United States, in Canterbury v Spence the appellate court held that ‘every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done to their own body' and stated that ‘the nature of the doctor‐patient relationship demands that the physician volunteer that information even if the patient does not ask’ (Canterbury v Spence 1972). In Australia, the High Court inRogers v Whitaker found unanimously against a surgeon who was considered to have provided inadequate information. The court stated that it is part of the doctor's duty to disclose 'material' risks. A risk is held to be material if "in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient's position, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it or if the medical practitioner is, or should be aware that the particular patient, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it" (Rogers v Whitaker 1992).

These cases indicate that there is a minimum amount of information that the patient needs in order to make an informed choice, although the depth and breadth of this information will vary from procedure to procedure, and some patients will request further details whilst others prefer to have less information. This may require clinicians to give information to patients who have said that they do not want to know more about the planned intervention.

The UK Department of Health emphasises that if the patient has not been given adequate information, or if they do not understand the information, or have not had sufficient opportunity to ask questions, the consent may not be valid even if the patient has signed a consent form. Conversely, properly informed verbal consent, without a signed consent form, is not a bar to treatment (DoH 2001; DoH 2009).

Problems with consent may occur because clinicians sometimes underestimate or undervalue the information needs of patients (Beisecker 1990). Alternatively they may overestimate the amount of information they give (Makoul 1995), lack the skills to give information (Jenkins 1999) or use technical language or jargon. Patients may feel pressured into consenting to a procedure that they have concerns about, or that they have not had adequate opportunity to discuss (Dixon‐Woods 2006). This can be through over‐emphasis of the benefits of a particular treatment, shortage of time, the clinician's manner or lack of empowerment on the part of the patient. Patients’ ability to seek further relevant information may also be influenced by how empowered they feel to ask questions, their knowledge of medical care and their physical condition (Akkad 2004).

A further challenge can involve the clinician translating population‐based estimates to an individual risk for that particular patient (Edwards 2002). Also patients may attach differing significance to different risks and benefits, and their perceptions of them may vary.

Clinicians may focus upon communicating specific technical risks of negative outcomes when talking to patients about the procedure, for example the risk of wound infection, bowel perforation or death (Barkin 2009;Ergina 2009). Some of these are of concern to patients, but sometimes this approach overrides consideration of other concerns of greater importance to the particular patient. These may include the consequences of the procedure, for example pain or length of time off work. The provision of complex information can be even more difficult when caring for a sick patient in an emergency, particularly if the clinician believes the information may add to the patient’s stress (Jefford 2002).

There are also organisational barriers to achieving informed consent. Ideally clinicians will talk to patients some time (at least two or three days) before the intervention or procedure. This allows the patient time to reflect on the discussion and deliberate on their options. However, often the signing of the consent form (and thus the formal consent discussion) is delayed until the patient is admitted (or attends as a day case) for the procedure. Then consenting can become a hurried ritual that does not allow the patient enough time to fully consider their decision (Elwyn 2008).

The use of a standardised consent form may add to the ritualised nature of consent discussion by making the process seem repetitive and ritualistic to the clinician. This can lead to the clinician becoming desensitised to the patient’s fears and concerns, as the clinician may view the treatment as being routine and commonplace (Picano 2004). Notably, only 41% of patients believe that the use of consent forms made their wishes known, and 46% believe that the primary function of the consent form was to protect the hospital (Akkad 2006). Any standardisation of the process runs the risk of failing to promote patient autonomy (Habiba 2004).

Description of the intervention

Ensuring informed consent presents challenges for both clinicians and healthcare organisations. Interventions to promote informed consent usually target patients, clinicians, or both. Interventions for patients generally provide information (ideally evidence based) about the treatment options, associated benefits, harms, probabilities and scientific uncertainties. Where they also encourage the patients to clarify personal values, ask questions and weigh up the pros and cons of choosing surgery (or a procedure), these interventions can be seen to fulfil the definition of 'decision aids' (Stacey 2011). The interventions may involve face to face contact, or online, video, telephone or leaflet‐based information. Interventions for clinicians generally address skills to improve how they share information, or direct them to concise sources of information. Interventions may also be organisational, for example the provision of more time for the patient to consider the procedure and ask questions.

Interventions may be categorised by whom they target (patients or clinicians); the purpose (e.g. general educational, encouraging shared decision making, etc); the format (media used: e.g. electronic, paper) and the timing and method of delivery (e.g. remote patient access at home, access supervised by a clinician).

How the intervention might work

Often patients do not fully understand the information provided during the consent process (Brezis 2008). However a clear set of skills for clinicians can be identified which, if used, increases the likelihood that patients will understand and be able to recall complex clinical information. Furthermore these include specific skills for shared decision making, risk communication and the use of decision aids. Clinicians can be trained in these skills (Silverman 2005).

Decision aids have been shown to improve patients’ knowledge regarding options, clarify perceptions of risk, reduce decisional conflict, reduce the number of people feeling passive about decision making and decrease the proportion of people remaining undecided (Stacey 2011). Where decision aids address conditions for which procedures requiring consent are among the options, they may promote informed consent through greater knowledge and consistency of personal values or attitudes with an enacted choice (for or against the treatment or procedure).

Why it is important to do this review

Over 4 million surgical procedures are undertaken in England each year (Royal College of Surgeons of England 2011), which all require patient consent. Similar volumes of procedures will occur in other similar countries. In addition there will be considerable numbers of other procedures requiring consent. However, the consent consultation frequently does not meet the needs of the patient (Akkad 2004). Reports indicate that patients do not receive sufficient information, that the information is not fully understandable or that the information patients receive is not tailored to their particular needs (Schattner 2006). Failure to achieve informed consent is the basis of many formal complaints, and costly litigation. Adequate information provision has additional wider benefits for patients, including increased satisfaction, more rapid symptom resolution, reduced emotional distress, reduced use of analgesia and possibly shorter hospital admissions (Egbert 1964; Hall 1988;Roter 2006). Informed patients are more likely to make conservative treatment options, such as declining surgical procedures, thus possibly reducing overall health costs (Kennedy 2002). Synthesis of the evidence aimed to establish the most robust evidence for the effectiveness of interventions in this field and thus promote implementation and identify the need for further research.

There may be some overlap with other reviews and protocols. Interventions to improve shared decision making (Duncan 2010;Légaré 2010) and informed consent in research have been reviewed (Ryan 2009), but there are no other Cochrane protocols or reviews that examine informed consent in relation to surgical or other invasive procedures alone. Gøtzsche and Jørgensen (Gøtzsche 2013) examined screening for breast cancer with mammography, noting the need for better information to promote informed consent for screening, but their review was not of interventions to promote informed consent. Other interventions, for example the provision of more information on a surgeon's performance, might also be of benefit; however Henderson and Henderson in their systematic review of this intervention identified no relevant studies (Henderson 2010).

Doust and colleagues (Doust 2007) are conducting a review of interventions to minimise harm from screening, including interventions which enhance knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening, but this does not consider any procedures that may follow the screening. Our own earlier review on interventions before healthcare consultations for helping patients get the information they require (Kinnersley 2007) also does not focus on surgical procedures but covers a range of settings, including primary care and outpatient medical settings. The Cochrane review ‘Decision aids to help people who are facing health treatment or screening decisions’, by Stacey et al (Stacey 2011) includes trials in which decision aids have been used to help patients make a decision about treatment options, but the trials do not analyse the informed consent process itself, and many of them do not address conditions directly related to invasive procedures.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical or other invasive healthcare treatments and procedures.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including cluster randomised trials.

Types of participants

Patients aged 16 years and over being asked to give consent for a surgical or other invasive healthcare treatment or procedure, either for themselves, or on behalf of a minor or someone else for whom they have responsibility.

We excluded trials in which:·

the patients were aged 16 years and over but were unable to consent to the procedure themselves (because they lacked capacity);·

the patients were detained in hospital (for example under the Mental Health Act in the UK);

the consent being obtained was to take part in a research trial (even if the trial itself involved an invasive procedure).

Types of interventions

Adhering to our protocol (Kinnersley 2011) we considered studies with interventions that:

targeted healthcare professionals, or patients, or both, who were participating in the consent process for a surgical or other invasive healthcare procedure, or

targeted organisational change of the consenting of these patients.

Interventions, even if targeted at clinicians, were required to have the intention of improving patients' understanding of their treatment options (including declining any intervention) and the procedure under consideration, evaluating their options, or helping them retain and recall the information provided, and thus their ability to provide informed consent.

Where the interventions targeted patients, we included studies in which the participants were undergoing procedures, as well as studies in which patients were considering more generally the possible treatment options for their condition, as long as this included at least one surgical or invasive option.

We excluded interventions that focused on the condition alone, or on conditions for which there was no surgical or invasive option. For example, interventions for patients undergoing cholecystectomy or considering treatment options for gallstones, which included cholecystectomy, were eligible to be included in the review. However, interventions that simply provided more information about gallstones without consideration of treatment options were excluded, as were interventions providing information about treatment options for conditions such as eczema (for which there are, as far as we are aware, none requiring consent).

We included interventions in any format/medium.

Comparisons were made between interventions and usual care (controls). Where there were multiple intervention arms we divided the control groups accordingly.

Types of outcome measures

We took a comprehensive approach to outcomes, as the obtaining of consent is a complex process with effects on the patient, the clinician and the healthcare system (CCCRG 2008).

Primary outcomes

Informed consent

The primary outcome was ‘informed consent’. For us to support an investigator’s view that he or she was measuring informed consent we sought evidence that the outcome measure took account of the patient going through the process of being provided with information about a procedure, which they had understood, retained and weighed up sufficiently to make a decision, which they had then communicated to the clinicians caring for them.

In doing this, we also considered Marteau’s model of informed choice (Marteau 2001) which places emphasis on patients’ decision making being supported by evidence of knowledge and consistent values (or satisfaction with the decision).

Ideally, informed consent or informed choice would be a single measure (dichotomised ‐ achieved or not achieved) of the effects of the intervention for a patient. Although we took the view that it would be more likely that trials reported understanding/knowledge, retention/weighing up, attitudinal and uptake measures at group levels (e.g. Evans 2007) it proved difficult to interpret data on different outcomes within individual studies. Instead we present the data for particular outcomes across studies and consider the meaning of these results in the Discussion.

Secondary outcomes

The initial secondary outcomes were the component elements of informed consent as described above.

Patient understanding

Since understanding has various facets and interpretations, we considered there was overlap between understanding, knowledge and recall. However we used Mazur's model of understanding to develop a framework to assess the patient's level of understanding in more depth or to report single facets (e.g. knowledge) (Mazur 2009). Indeed in some studies authors stated that they were assessing understanding, but in fact used instruments measuring only recall or knowledge. In these cases, we re‐classified the outcomes measured. For example, if a researcher described the measurement of understanding when in fact we believed it to represent the measurement of knowledge, we classified this as knowledge; the distinction being that understanding implied a deeper level of comprehension. For instance, a patient may know that they need surgery because they have appendicitis, without necessarily understanding that they need surgery with an awareness to some extent of the pathophysiological process and the consequences of not having surgery.

We sought data on the following aspects of understanding:

Understanding in terms of asking the patient directly if the information had been understood (patient‐reported understanding);

Understanding in terms of evidence of comprehension of the information provided, and the patient's situation beyond simple factual recall;

Understanding in terms of the way the patient used the information provided. If the information has been understood, subsequent decisions by the patient should be consistent with their personal values. Evidence of this process was considered to be present for the outcomes of deliberation and decisional conflict.

Knowledge/retention/recall

Knowledge/retention/recall were most commonly measured by assessing the extent to which the patient ‘knew’ the information with which they had been provided about the procedure; for example, what the patient knew about appendicectomy. Most often it would be the case that patients were recalling information told to them during the consent consultation. However, in some cases this knowledge may have reflected information that the patient had gathered before the consent process for this particular episode of health care. So, before an episode of appendicitis, many patients will know that the appendix is a part of the bowel (although they may not understand what part of the bowel it is, and the role it plays in sickness and in health). For simplicity we equated ‘recall’ of information provided in the consent consultation with wider knowledge and have reported this as 'knowledge'.The timing of measurement of knowledge also provided information as to the retention of information. To make comparisons we made a pragmatic decision to categorise the outcomes depending upon the time of measurement after the intervention into immediate (24 hours or less), short‐term (between 24 hours and 14 days) and long‐term (15 days or more).

Deliberation (weighing up)

Making an informed decision or choice requires someone to consider carefully (deliberate) or weigh up the information, and how it fits with their personal circumstances and values (Elwyn 2010). We examined studies in which researchers claimed to have measured deliberation, and report on both the methods used and the intervention effects.

Communication of decision

Communication of decision is generally demonstrated (in cases of assent to the procedure) by the patient signing a consent form as discussed above. However, researchers may attempt to measure closely‐related concepts, such as confidence in the decision, consistency of decision making or decisional conflict (Stacey 2011).

Other patient outcomes

We also collected data on:

Satisfaction and anxiety with decision making;

Satisfaction and anxiety with the consent process;

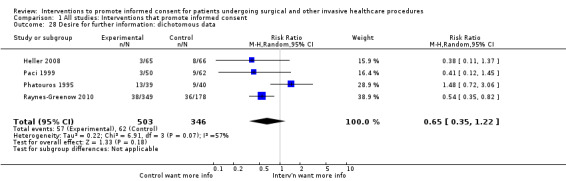

Desire for further information;

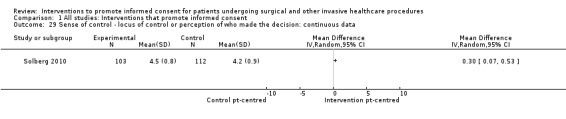

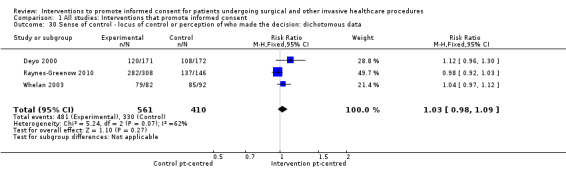

Sense of control ‐ locus of control or perception of who made the decision:

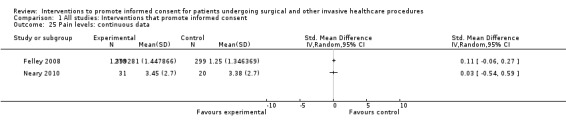

Pain experienced or analgesia use.

Clinician outcomes

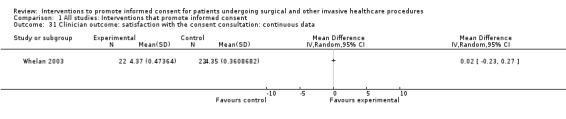

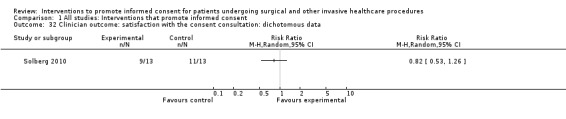

We collected data on the following clinician outcomes:

Satisfaction with the 'consent consultation' (or process);

Ease of use of intervention(s) to improve gaining of informed consent;

Confidence in patient's decision and whether an informed choice was made.

System outcomes

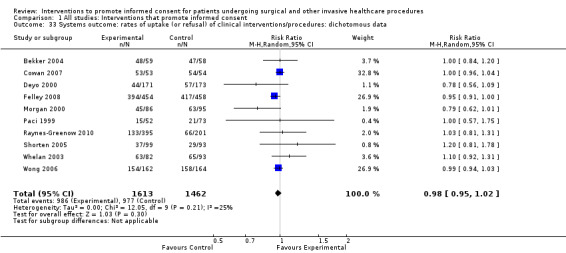

To further judge the effects of interventions, it was necessary to assess changes to the overall healthcare system, and further evidence of patient implementation of choices. We collected data on the following outcomes:

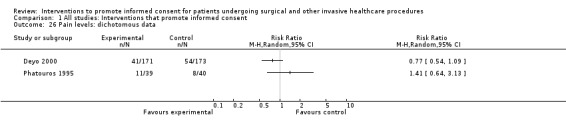

Rates of uptake (or refusal) of clinical interventions/procedures;

Postponement of clinical interventions/procedures;

Delay in decision making or request for more information/further consultations;

Complaints and litigation;

Adverse procedural outcomes;

Economic/resource use data (e.g. length of consultations, cost of surgery/procedure choices, number of consultations, and length of hospital stay).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We performed an electronic search from database inception to July 2011 in MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP) and PsycINFO (OvidSP) using Medical Subject Headings and text words, applying a randomised controlled trial filter to capture the study types included in the review. We also searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Library, issue 5, 2012. We applied no language or date restrictions within the search. The detailed search strategies are in Appendices (1 to 4).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included trials and relevant published reviews to identify further potentially‐relevant studies. We had planned to search a number of additional sources as specified in the review protocol (Kinnersley 2011), but decided that complete coverage of the area was already ensured by the our search of the above databases.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Stage 1

We conducted the searches for relevant trials, combining the results into a single database and eliminating duplicates.

Stage 2

We screened titles and abstracts to eliminate obviously irrelevant studies. To ensure consistent application of inclusion criteria, we screened the titles in batches of 20, with 3 authors discussing their results. Disagreements were discussed with the wider author team. Once a high level of consistency was achieved two authors worked independently on larger batches of abstracts, again with disagreements being discussed with the wider team.

Stage 3

We retrieved full text copies of all potentially‐relevant papers, including those for which the description was insufficient to make a decision about inclusion. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between the two assessing authors and an arbiter from the review team (PK or AE). Studies excluded at this stage are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Stage 4

Two review authors then reviewed relevant studies to ascertain whether there were multiple reports from single studies and linked these together if applicable to produce a final set of studies for inclusion in the review. These were entered into RevMan 5 software.

Stage 5

We scanned the reference lists of included studies to check for further possibly‐relevant studies which had not been identified. These were re‐entered at Stage 3.

Data extraction and management

Two authors independently extracted data from each included study using a modified Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group data collection checklist that had been predetermined and piloted by the review authors (Appendix 5). The authors each entered the data onto a separate electronic form. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by discussion between all review authors or, where this was not possible, between the two review authors extracting data and an arbiter (PK or AE). The data included the study methods, setting and participants, interventions, outcomes and results.

Extracted data were entered into RevMan 5 by one author and checked for accuracy against the original data by a different author (variable combinations of authors for individual studies). In cases of missing data we tried to contact the authors of the studies by email to obtain the relevant information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

When assessing the risk of bias we used criteria in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed and reported on the risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2011), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual quality elements for RCTs: randomisation; allocation concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias. In all cases, two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion and consensus. Table 1 shows an overview of the rules that we applied when assessing the risk of bias.

1. Risk of bias: Rules applied when assessing the risk of bias.

| Risk of bias domain | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk |

| Random sequence generation | Clearly described and appropriate method of randomisation (e.g. computerised randomisation). | No description of random sequence generation. | Alternation or allocation by date or hospital number |

| Allocation concealment | Clearly described and appropriate method of allocation concealment (e.g. central or pharmacy allocation). | No description of allocation concealment. | Inappropriate method of allocation concealment or evidence that allocation procedure was not adhered to. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Clearly described and appropriate method of blinding of BOTH participants and personnel. | No description of blinding of participants and personnel. | Inappropriate method of blinding, evidence that blinding procedure was not adhered to or study was ‘unblinded’ for EITHER participants or personnel. |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Clearly described and appropriate method of blinding of outcome assessors. | No description of blinding of outcome assessors. | Inappropriate method of blinding, evidence that blinding procedure was not adhered to or study was ‘unblinded’ for outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data | Attrition of participants of < 40%. | No description of attrition. | Attrition of participants of ≥ 40%. |

| Selective outcome reporting | Protocol available and all outcomes pre‐specified were reported in the final publication. | No protocol available. | Protocol available and one or more outcomes pre‐specified were not reported in the final publication. |

| Other sources of bias | No evidence of elements of high risk of bias. | Not applied. | Evidence of any of:

|

When assessing randomisation we checked that the investigators had described an adequate random component in the sequence generation. These were judged to have met this criterion were considered low risk of bias. Those that had used a non‐random component were judged not to have met the criterion and marked as high risk.

We assessed whether allocation concealment was adequate and whether blinding was adequate, (blinding of the participants and personnel, performance bias and blinding of outcome assessment, detection bias) with those that were adequate being categorised as low risk and those that were judged to be inadequate being high risk. Where there was insufficient evidence, studies were classed as unclear.

We also examined outcome data to ensure that the effect of incomplete data (attrition bias) had been adequately addressed. Studies with no loss to follow up or an attrition rate of less than 40% were considered low risk and those that had a greater than 40% attrition were considered high risk. Where there was insufficient evidence, studies were classed as unclear.

We assessed selective outcome reporting as well. If a study had a protocol and this was followed then it was considered low risk, studies were considered high risk if one or more pre‐specified outcomes were not reported. Studies with no available protocol were considered to be unclear.

We then looked at other potential risks of bias; such as threats to validity as detailed in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool, potential contamination of the intervention or sources of funding leading to competing interests.

We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods as required. If we received no response, the study was marked as unclear for the relevant domain. We incorporated the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment into the review through systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the items, leading to an overall assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies and a judgement about the internal validity of the review results.

Measures of treatment effect

The two main types of outcomes were continuous and dichotomous. Continuous outcomes were summarised using standardised estimated mean differences. Dichotomous outcomes were summarised using relative risks. For the measures of variance we calculated 95% confidence intervals for the effect estimates. If only non‐parametric data were reported in studies, this was included as narrative description for each relevant outcome to summarise findings in the literature as fully as possible.

For the primary outcome (informed consent/choice), we aimed to identify reports of individual informed consent (achieved or not achieved) for meta‐analysis. If there were studies which reported changes in understanding, values or choices made at group level only, we reported these separately and considered if it was appropriate to include them in a meta‐analysis.

Where studies had multiple outcomes in the same outcome category we identified the main outcome for the study by:

Selecting the primary outcome as identified by the publication authors;

If no primary outcome was specified, selecting the one specified in the sample size calculation;

If there was no sample size calculation, we ranked the effect estimates and selected the median effect estimate.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies in which clusters of individuals were randomised or allocated to intervention groups, but intervention was intended at the level of the individual, are problematic because they may lead to artificially small P values if standard statistical methods are used. We intended to account for this by re‐calculating the statistical significance accounting for intra‐cluster correlations. However, in the event only two studies were found that employed cluster randomisation (Paci 1999; Solberg 2010). Paci 1999 randomised by day of visit which would not be expected to produce appreciable clustering. Solberg 2010 randomised by centre but the impact of clustering possible from this one study was not deemed sufficient to re‐analyse the data. We note the unit‐of‐analysis error.

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact all authors to obtain additional data. In addition we attempted to clarify the method of randomisation and whether allocation was concealed . We tried to carry out an intention‐to‐treat analysis where this was not reported by the authors and the authors did not respond to our enquiries. If sufficient data were not available, we carried out an available case analysis and consider the implications of the missing data in the Discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the statistical heterogeneity in meta‐analyses by visually inspecting the scatter of effect estimates on forest plots and by the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We categorised I2 values of 0% to 30% as indicating little evidence of heterogeneity, 31% to 60% as moderate heterogeneity, 61% to 80% as substantial heterogeneity and over 80% as considerable heterogeneity.

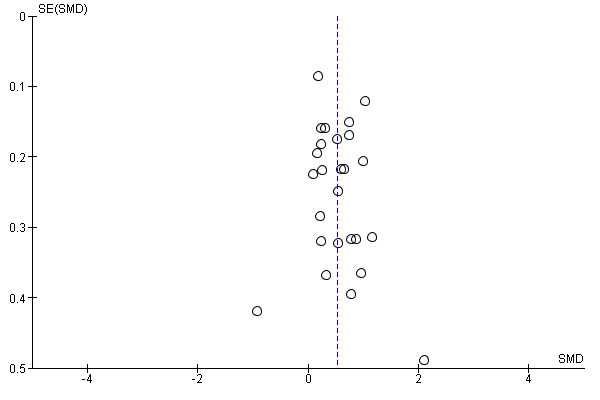

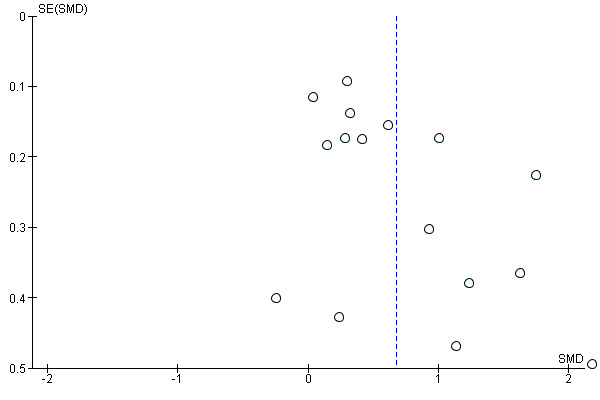

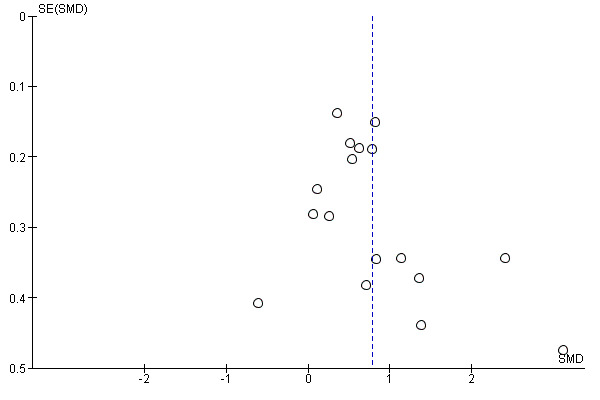

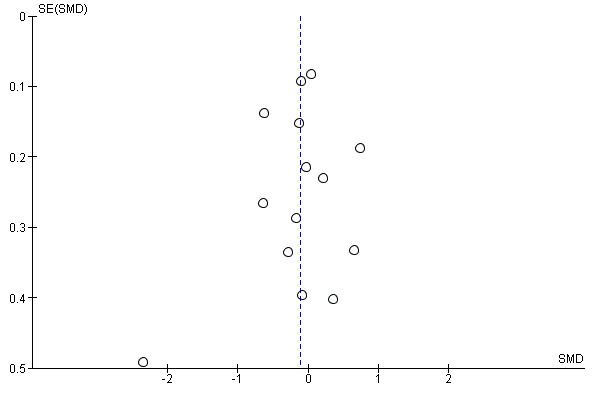

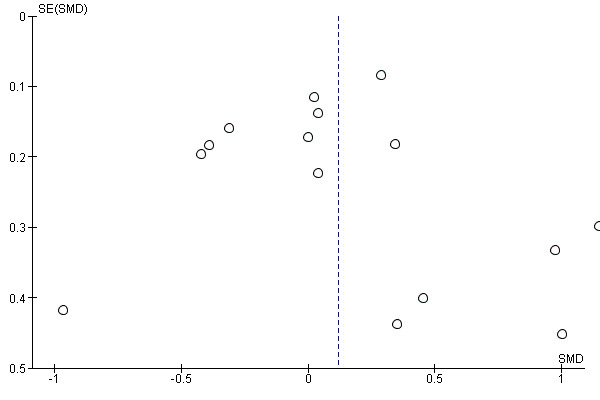

Assessment of reporting biases

Where possible, we accessed the Clinical Trials Registry to determine whether studies were reporting their pre‐specified primary outcomes. Where there was evidence of selective outcome reporting, this is reflected in the 'Risk of bias' assessment (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). Where sufficient RCTs and data for a given outcome were available, we conducted a visual inspection of the funnel plots to investigate any asymmetry as an indication of publication bias.

Data synthesis

For all studies, we have produced tables of summary statistics and graphs of the data. Although the procedures vary in complexity, we consider it likely that it is the type of intervention which is more important than the type of procedure that was being undertaken, and therefore our main focus was on types of intervention and assessing whether there were consistent benefits (or harms) across similar interventions.

We conducted a meta‐analysis of those studies and outcomes which appear homogenous (minimum of three studies) (Treadwell 2006) using a random‐effects model. Although our original intention was only to conduct meta‐analyses where heterogeneity was low (I2 statistic < 50%) we concluded it was more useful to conduct meta‐analyses regardless of the I2 statistic and leave it to the reader to take note of the heterogeneity of the studies. We performed data synthesis using RevMan 5.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Several features of the interaction between patient and clinician may affect communication, the interaction, and thus the opportunity to achieve informed consent for procedures. We planned and attempted to undertake the following comparisons:

face‐to‐face interventions versus distant interventions (for example web‐based);

interventions targeted at clinicians versus those targeted at patients or at organisational change;

the age of patients (young 16 to 35 years; middle‐aged 36 to 60 years; older 61 to 80 years, elderly over 80 years);

interventions targeted at a specific procedure (i.e. whether to undergo, for example, an operation such as knee replacement for osteoarthritis) or at a condition more generally (but for which at least one option may be surgical (e.g. a decision aid addressing menorrhagia)).

For the subgroup analyses we divided the studies into the subgroups of interest and conducted meta‐analyses where possible. We present for each subgroup analysis the standardised mean difference, confidence intervals and measure of heterogeneity for continuous data and, in the case of dichotomous data, relative risks, confidence intervals and measure of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis based on the risk of bias identified in the studies. Studies identified as being of greatest risk of bias, specifically regarding randomisation, attrition and blinded outcome assessment were systematically removed from the analysis and we report the effects on the effect estimate.

Consumer participation

We engaged consumer input and representation from Cynnws Pobl (involving people), the consumer network of Clinical Research Collaboration Cymru, for advice on outcome measures, searching for types of interventions and assistance in analysis and interpretation of the effects of interventions across consumer/participant groups.

We also recruited clinician representatives to form a clinician reference group. A range of clinicians (surgical, medical and nursing) who are involved in the consent process were recruited from hospitals in South Wales and South West England, including surgical, radiological and other disciplines. They provided feedback on the results of the review and assisted with the writing of the plain language summary.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

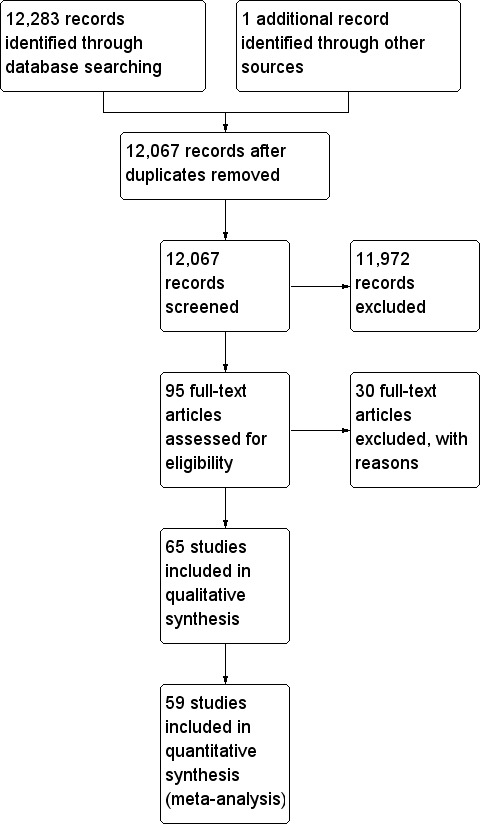

The electronic searches conducted yielded 12,283 references and other sources retrieved 1 reference. The number of records after removal of duplicates was 12,067. From these, we identified 271 papers for further examination of the full text. Ninety‐five studies were identified for data extraction and preliminary inclusion but 30 of these studies were subsequently excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Thus Sixty‐five studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis. A flow diagram of the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Size of review

We included 65 studies with a total of 9021 participants in the review (see Characteristics of included studies). Individual studies ranged from 20 participants (Wadey 1997) to 596 participants (Raynes‐Greenow 2010).

Five studies (six intervention arms) contributed only non‐parametric data so were included in qualitative synthesis only (Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Gerancher 2000; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Mason 2003; Wadey 1997).

In seven studies, two separate interventions were compared with one control (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b;Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b). For these studies we split the control group to make independent comparisons with each intervention group. Each of these studies is listed twice in the Included studies list, to enable appropriate reporting and analysis. Overall, there are 72 treatment arms for analysis from the 65 studies.

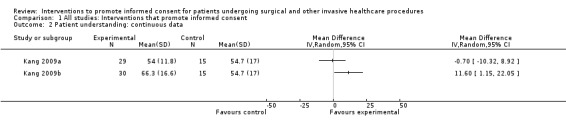

Settings

Sixty three studies were set in hospital/secondary care and two studies were conducted in dental practice (Johnson 2006; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b). Twenty five studies were from the USA, 14 from the UK, eight from Australia, seven from Canada, three from Germany, two from Ireland, and one from each of Austria, France, Italy, New Zealand, Switzerland and Turkey. Sixty three studies were written in English; one was translated from French (Danino 2006) and another from German (Hermann 2002).

Participants

Studies focused on adults who were providing informed consent for themselves (60 studies) or were doing this on behalf of a minor (5 studies). Studies had similar exclusion criteria, which referred to a lack of competence to consent or language barriers for the interventions.

Interventions

Intervention types were broadly grouped into audio‐recorded aids (audio‐cassette recording of the consultation or containing information about consent), non‐interactive audio‐visual aids (onscreen DVD, video or software package which the participant watched from beginning to end), interactive multimedia (onscreen DVD, video or software package for which the participant was able to select material to review out of order), written interventions (intervention delivered on paper), decision aids (including multi‐component decision aids), structured consent processes (processes the clinician used to structure the consultation e.g. flip‐sheets, question prompt sheets), question prompt sheets (given to the patient to use) or altering the timing of consent (relative to the time of the procedure). The interventions used in studies are summarised in the following table:

Procedures

Participants were generally those attending for elective procedures but included some emergency procedures. The procedures are summarised in the following table:

| Procedure type | Number of studies (intervention arms) | References |

| Surgical | 32 (35 intervention arms) | Armstrong 1997; Armstrong 2010; Ashraff 2006; Bollschweiler 2008; Chan 2002; Chantry 2010; Cornoiu 2010b; Cornoiu 2010a; Danino 2006; Deyo 2000; Fink 2010; Garrud 2001; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Hong 2009; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Masood 2007; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010b; Mishra 2010a; Nadeau 2010; Neary 2010; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Pesudovs 2006; Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Wilhelm 2009; Zite 2011 |

| Invasive medical procedure e.g. endoscopy, colonoscopy, angiogram, bronchoscopy | 10 (12 intervention arms) | Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Elfant 1995; Enzenhofer 2004; Felley 2008; Friedlander 2011; Luck 1999; Phatouros 1995; Tait 2009; Uzbeck 2009 |

| Anaesthetics e.g. general anaesthesia, epidural analgesia, regional anaesthesia | 4 (4 intervention arms) | Garden 1996; Gerancher 2000; Kain 1997; Paci 1999 |

| Electroconvulsive therapy | 1 (1 intervention arm) | Greening 1999 |

| Dental procedures | 2 (3 intervention arms) | Johnson 2006; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b |

| Paediatrics e.g. neonatal circumcision, inguinal hernia repair, ENT surgery, endoscopy or orthodontics | 5 (6 intervention arms) | Chantry 2010; Friedlander 2011; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Nadeau 2010; Rymeski 2010 |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (2 intervention arms) | Olver 2009; Thomas 2000 |

| Antenatal screening procedures for Down Syndrome (including invasive options for screening) | 1 (1 intervention arm) | Bekker 2004 |

| Invasive radiology (spinal and facet joint injections, urography, intra‐venous contrast CTs) | 5 (6 intervention arms) | Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Cowan 2007; Hopper 1994; Neptune 1996; Yucel 2005 |

Description of interventions

Development

We analysed included studies for data on how the interventions were developed (Table 2). For 42 of 72 intervention arms (58.3%) it appeared that the interventions were designed for the trial with no validation or piloting (Armstrong 2010; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bekker 2004; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Chan 2002; Chantry 2010; Cowan 2007; Danino 2006; Elfant 1995; Enzenhofer 2004; Fink 2010; Garden 1996; Garrud 2001; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Hermann 2002; Hong 2009; Kain 1997; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Neary 2010; O'Neill 1996a ;O'Neill 1996b; Olver 2009; Pesudovs 2006; Phatouros 1995; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Rossi 2004; Tait 2009; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Wilhelm 2009; Yucel 2005; Zite 2011). For 16 of 72 intervention arms (22.2%) there appeared to be reasonable efforts to pilot and validate the interventions (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Bollschweiler 2008; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Deyo 2000; Goel 2001; Hopper 1994; Johnson 2006; Morgan 2000; Neptune 1996; Shorten 2005; Solberg 2010; Thomas 2000; Whelan 2003; Wong 2006). For 4 of 72 intervention arms (5.5%) the intervention was modified from standard procedures (Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Masood 2007; Uzbeck 2009) and for another 4 intervention arms (5.5%) the intervention was the introduction of a standard procedure not currently in use (Friedlander 2011; Luck 1999; Rossi 2004; Rymeski 2010). For 6 intervention arms (8.3%) no details were provided (Armstrong 1997; Ashraff 2006; Felley 2008; Gerancher 2000; Neary 2010; Paci 1999).

2. Details of the development of the intervention, the exposure to the intervention, the training for delivery of the intervention and evaluation of the intervention delivery; 72 treatment arms reported here.

| Development of the intervention | Number of intervention arms |

| no details | 6 |

| designed for trial ‐ no validation | 42 |

| designed for trial ‐ reasonable effort for validation/piloting | 16 |

| modified from standard information | 4 |

| standard information ‐ no modifications | 4 |

| Total | 72 |

| Exposure to the intervention | |

| once | 65 |

| twice | 1 |

| multiple exposures to the same intervention | 4 |

| two different interventions at different times | 2 |

| Total | 72 |

| Training for delivery of intervention | |

| none needed | 22 |

| no details | 35 |

| no training | 0 |

| brief training | 9 |

| structured/extensive training | 2 |

| all delivered by key researcher | 4 |

| Total | 72 |

| Evaluation of delivery of the intervention | |

| no details | 59 |

| evidence of fidelity/reliability of delivery | 13 |

| Total | 72 |

Exposure to the intervention

Studies were analysed for data on the number of exposures participants had to the interventions (Table 2). In 65 intervention arms (90.2%) participants were exposed to the intervention once (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Armstrong 1997; Ashraff 2006; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bekker 2004; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Bollschweiler 2008; Chan 2002; Chantry 2010; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Danino 2006; Deyo 2000; Elfant 1995; Enzenhofer 2004; Felley 2008; Fink 2010; Friedlander 2011; Garden 1996; Garrud 2001; Gerancher 2000; Goel 2001; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Hermann 2002; Hong 2009; Hopper 1994; Johnson 2006; Kain 1997; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Luck 1999; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Masood 2007; Mauffrey 2008; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; Neary 2010; Neptune 1996; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Olver 2009; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Phatouros 1995; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Tait 2009; Uzbeck 2009; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Wilhelm 2009; Wong 2006; Yucel 2005; Zite 2011). One arm (1.4%) gave two exposures to the same intervention (Armstrong 2010). Four arms (5.5%) gave participants multiple exposures to the same Intervention (Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Thomas 2000; Whelan 2003). Two arms (2.7%) gave the consumers two exposures to two different interventions (Shorten 2005; Solberg 2010).

Training for delivery of intervention

For 35 intervention arms (48.6%) no details were provided of the training given to staff delivering the intervention (Table 2) (Agre 1994b; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bollschweiler 2008; Chan 2002; Danino 2006; Elfant 1995; Fink 2010; Garden 1996; Garrud 2001; Gerancher 2000; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Hong 2009; Hopper 1994; Kain 1997; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Mauffrey 2008; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; Neptune 1996; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Phatouros 1995; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Rossi 2004; Shorten 2005; Solberg 2010; Walker 2007; Yucel 2005). For 22 intervention arms (30.5%), little or no training appeared necessary, for example if the intervention was delivered by the participants viewing a video (Agre 1994a; Armstrong 1997; Ashraff 2006; Chantry 2010; Felley 2008; Friedlander 2011; Hermann 2002; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Luck 1999; Masood 2007; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Neary 2010; Olver 2009; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Tait 2009; Thomas 2000; Uzbeck 2009; Wilhelm 2009; Wong 2006). For nine intervention arms (12.5%) brief training was given to staff involved (Armstrong 2010; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Deyo 2000; Enzenhofer 2004; Goel 2001); for two intervention arms (2.7%) structured and extensive training was given (Johnson 2006; Whelan 2003); and for four intervention arms (5.5%) all interventions were delivered by the key researcher (Bekker 2004; Greening 1999; Wadey 1997; Zite 2011).

Evaluation of the delivery of the intervention

In 59 intervention arms (81.9%) there was no evidence of evaluation of the delivery of the intervention (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Armstrong 1997; Armstrong 2010; Ashraff 2006; Bekker 2004; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Chan 2002; Chantry 2010; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Danino 2006; Elfant 1995; Fink 2010; Friedlander 2011; Garden 1996; Garrud 2001; Gerancher 2000; Goel 2001; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Hermann 2002; Hong 2009; Hopper 1994; Johnson 2006; Kain 1997; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Luck 1999; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Masood 2007; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Nadeau 2010; Neary 2010; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Phatouros 1995; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Solberg 2010; Tait 2009; Uzbeck 2009; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Whelan 2003; Wilhelm 2009; Yucel 2005; Zite 2011) and in 13 intervention arms (18.1%) there was evidence of checks on the fidelity and reliability of the delivery of the interventions (Table 2) (Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bollschweiler 2008; Deyo 2000; Enzenhofer 2004; Felley 2008; Morgan 2000; Neptune 1996; Olver 2009; Rymeski 2010; Shorten 2005; Thomas 2000; Wong 2006).

Details of the consent process in the control group

In 33 intervention arms (45.8%) the control groups received verbal information only in their consent consultation (Table 2) (Armstrong 1997; Armstrong 2010; Ashraff 2006; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bekker 2004; Chantry 2010; Cowan 2007; Elfant 1995; Enzenhofer 2004; Felley 2008; Friedlander 2011; Hermann 2002; Hopper 1994; Johnson 2006; Langdon 2002; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; Neary 2010; Neptune 1996; Paci 1999; Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Wilhelm 2009). In 23 intervention arms (30.9%) participants in the control group received standardised or particular written information as well as verbal information (Bollschweiler 2008; Danino 2006; Deyo 2000; Garden 1996; Garrud 2001; Goel 2001; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Luck 1999; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Olver 2009; Phatouros 1995; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Solberg 2010; Thomas 2000; Uzbeck 2009; Whelan 2003; Yucel 2005; Zite 2011). In 12 intervention arms (16.7%) the consenting clinician used a checklist of points to cover when talking to the patients (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Chan 2002; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Gerancher 2000; Hong 2009; Mauffrey 2008; Pesudovs 2006; Tait 2009). In one intervention arm (1.4%) a dummy intervention was used (Wong 2006); in another one (1.4%) an audiovisual intervention was used (Fink 2010); and in two (2.8%) no details were provided (Kain 1997; Shorten 2005). See Table 3 for an overview of the consent process in the control group.

3. Details of the consent process in the control group.

| Details of the consent process in the control group | Number of intervention arms |

| No details | 2 |

| verbal only | 33 |

| verbal + standardised leaflet | 20 |

| verbal + special leaflet | 3 |

| verbal + checklist | 12 |

| verbal + dummy intervention | 1 |

| audiovisual | 1 |

| Total | 72 |

Missing data/contact with authors

For 39 studies we sought clarification from the authors, usually about sources of bias, and we received responses from 28 authors (Armstrong 2010; Ashraff 2006; Bekker 2004; Bollschweiler 2008; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Deyo 2000; Fink 2010; Garden 1996; Gerancher 2000; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Henry 2008; Kain 1997; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Luck 1999; Masood 2007; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; Olver 2009; Pesudovs 2006; Phatouros 1995;Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Tait 2009; Wilhelm 2009) (contacted but no reply – Armstrong 1997; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Chan 2002; Elfant 1995; Garrud 2001; Goel 2001; Johnson 2006; Lavelle‐Jones 1993; Neptune 1996; Uzbeck 2009; Whelan 2003). We used unpublished data from 16 studies (Armstrong 2010; Bekker 2004; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Fink 2010; Garden 1996; Kain 1997; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Luck 1999; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; Olver 2009; Tait 2009; Wilhelm 2009).

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Seven of these studies (Altaie 2011; Clark 2011; Finch 2009; Gyomber 2010; Migden 2008; Scanlan 2003; Stanley 1998) met the inclusion criteria but had no usable data; details are shown in Table 4.

4. Studies with unusable or insufficient data for analysis.

| Study | Details of study | Details of data |

| Altaie 2011 | A three armed RCT looking at patients recall of knowledge. 36 patients undergoing strabismus surgery were randomised to either standardised consent, standardised plus written information or standardised plus written that included a quiz in the leaflet. A questionnaire was administered on admission which asked the same questions as the quiz. |

No numbers presented in the results. |

| Clark 2011 | RCT looking at patient recall of knowledge. 50 patients admitted for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the USA were randomised to either a power point presentation or to usual care. A questionnaire was completed after the power point (before surgery) to test knowledge. |

Results show mean scores for the two groups but there is not enough detail to extract a SD. Unable to contact authors |

| Finch 2009 | RCT looking at patient recall of knowledge. 100 patients admitted for a transurethral resection of prostate in the UK were randomised to either standard consent or a more detailed written form. These forms were given the night before surgery and recall was tested with a questionnaire three hours later. |

Data not presented in usable form for this review. Unable to make contact with author |

| Gyomber 2010 | RCT looking at patient recall of knowledge. 40 patients admitted for a radical prostatectomy in Australia were randomised to either standard consent or consent in an interactive multimedia form. Recall was tested immediately after the intervention was given. |

Medians and N values are the only data shown |

| Migden 2008 | RCT looking at patient recall of knowledge, satisfaction with the consent process and time of consultation. 11 patients under going Mohs surgery in the USA were randomised to either standard consent or consent with a video. Satisfaction collected on a Likert scale and no details of how knowledge was tested. |

Data not presented in usable form for this review. Time given as a mean with no SD. No data given on knowledge and satisfaction. Contact with author ‐ he is unable to give raw data |

| Scanlan 2003 | RCT looking at patients recall of knowledge . 28 patients undergoing cataract surgery in Canada were randomised to either receive or not to receive further written in formation after the consent consultation. Knowledge was assessed by a questionnaire at time of consultation and one week after surgery. |

Data not presented in usable form for this review. Unable to obtain raw data from authors |

| Stanley 1998 | A four armed RCT that looked at knowledge and anxiety with the consent process. 32 patients undergoing femoral popliteal bypass or carotid surgery in Australia were randomised into groups of normal consent, more detailed written consent, more detailed verbal consent and more detailed written and verbal consent. HADS scores for anxiety and a questionnaire for knowledge were administered after the consent process. |

No extractable data available. |

Risk of bias in included studies

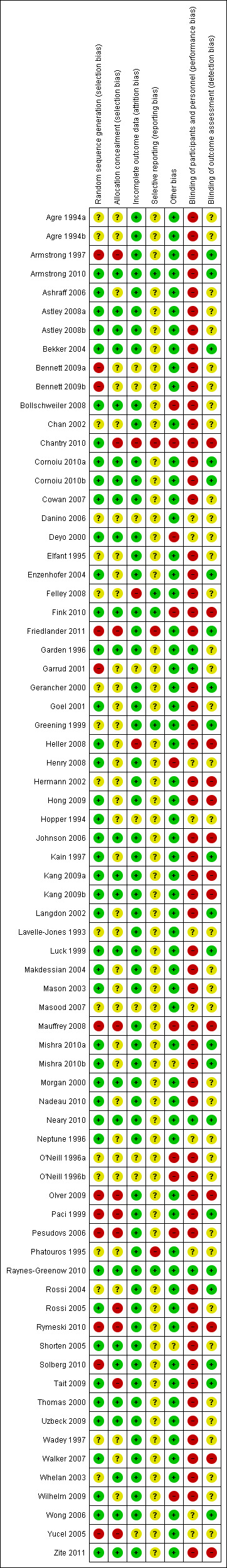

Overall 11 studies were considered to be at high risk of bias regarding random sequence generation, 9 at high risk for attrition bias and 20 studies were considered at high risk for blinding of outcomes (Figure 2). Please refer to Characteristics of included studies for further information on individual studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Eleven studies (12 arms) were at high risk of selection bias with poor methods for random sequence generation (Armstrong 1997; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Friedlander 2011; Garrud 2001; Mauffrey 2008; Olver 2009; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Rymeski 2010; Solberg 2010; Yucel 2005).

Eleven studies were at high risk of allocation/selection bias with no rigorous methodology to remove the chance of predicting allocation (Armstrong 2010; Chantry 2010; Friedlander 2011; Mauffrey 2008; Olver 2009; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Tait 2009; Yucel 2005).

Blinding

Due to the nature of the research, informed consent was sought for these studies and some level of understanding of the group allocation by patients or clinicians was likely in most cases. Therefore blinding of participants or personnel was difficult to achieve. Fifty‐one studies (58 arms) were at high risk of performance bias (Agre 1994a; Agre 1994b; Armstrong 1997; Armstrong 2010; Ashraff 2006; Astley 2008a; Astley 2008b; Bekker 2004; Bennett 2009a; Bennett 2009b; Bollschweiler 2008; Chan 2002; Chantry 2010; Cornoiu 2010a; Cornoiu 2010b; Cowan 2007; Elfant 1995; Enzenhofer 2004; Felley 2008; Fink 2010; Friedlander 2011; Gerancher 2000; Goel 2001; Greening 1999; Heller 2008; Hermann 2002; Hong 2009; Johnson 2006; Kain 1997; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Langdon 2002; Luck 1999; Makdessian 2004; Mason 2003; Mauffrey 2008; Mishra 2010a; Mishra 2010b; Morgan 2000; Nadeau 2010; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Olver 2009; Paci 1999; Pesudovs 2006; Rossi 2004; Rossi 2005; Rymeski 2010; Shorten 2005; Solberg 2010; Tait 2009; Thomas 2000; Uzbeck 2009; Wadey 1997; Walker 2007; Whelan 2003; Wilhelm 2009; Zite 2011).

Twelve studies (13 arms) were at high risk of detection bias (Chantry 2010; Fink 2010; Heller 2008; Hermann 2002; Hong 2009; Johnson 2006; Kang 2009a; Kang 2009b; Mauffrey 2008; Olver 2009; Rymeski 2010; Walker 2007; Zite 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies were at high risk of attrition bias due to attrition rates above the 40% threshold. In Chantry 2010 43% of the control group and 47% of the intervention group were lost to follow up; in Felley 2008 the drop out rate was 46%; and in Heller 2008 the drop out rate was 51%.

Selective reporting

Three studies were at high risk of reporting bias. In Chantry 2010 data on satisfaction were not included at one month follow up and only 10 of 14 questions were used in a composite knowledge score; in Friedlander 2011we judged there were differences between the registered protocol and the published report; and in Phatouros 1995 again there were missed data on outcomes which were reported in the methods as being measured.

Other potential sources of bias

Nine studies (10 arms) were at high risk of other bias with fidelity or contamination concerns (Bollschweiler 2008; Chantry 2010; Deyo 2000; Fink 2010; Henry 2008; Mauffrey 2008; O'Neill 1996a; O'Neill 1996b; Pesudovs 2006; Wilhelm 2009).

Effects of interventions

Studies using all types of intervention were included in the main analysis and contribute to the results. Subgroup analyses were then performed to evaluate the effects of face‐to‐face versus distant implementation of interventions, effects on different age groups, effects of different types of interventions, and effects of timing of the intervention prior to the procedure being undertaken.

Our main results are summarised in Table 5.

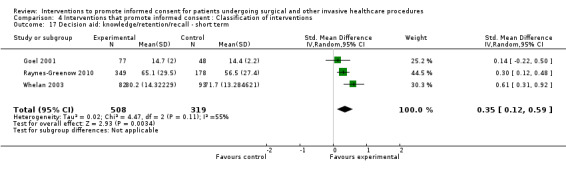

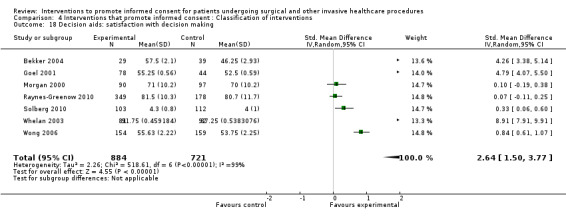

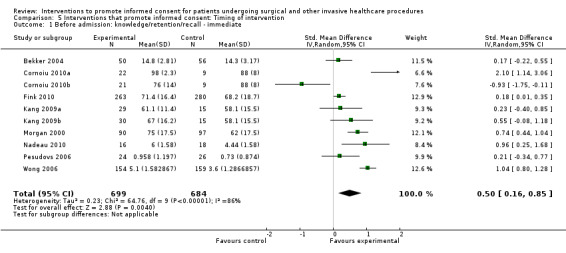

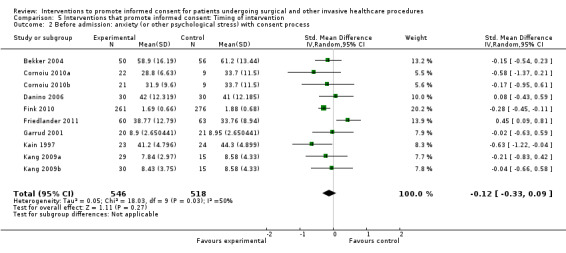

5. Overview of findings.

| Intervention | Number of studies (arms) | Immediate knowledge | Short‐term knowledge | Long‐term knowledge | Generalised anxiety | Anxiety with the consent process | Decisional conflict | Satisfaction with the consent process | Satisfaction with the decision making |

| All interventions | 65 (72 arms) |

22 studies (26 arms) SMD 0.53 (0.37 to 0.69) I2 = 73% |

14 studies (16 arms) SMD 0.68 (0.42 to 0.93) I2 = 85% |

15 studies (17 arms) SMD 0.78 (0.50 to 1.06) I2 = 82% |

12 studies (14 arms ) SMD ‐0.11 (‐0.35 to 0.13) I2 = 82% |

11 studies (13 arms ) SMD 0.01 (‐0.21 to 0.23) I2 = 70% |

3 studies (3 arms) SMD ‐1.80 (‐3.46 to ‐0.14) I2 = 99% |

13 studies (15 arms) SMD 0.12 (‐0.09 to 0.32) I2 = 76% |

8 studies (8 arms) SMD 2.25 (1.36 to 3.15) I2 = 99% |

|

All interventions Dichotomous data |

3 studies (3 arms) RR1.17 (0.85 to 1.60) I2 = 84% |

No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | 10 studies (10arms) RR 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) I2 = 75% |

No data | |

| Face‐to‐face interventions | 16 (16 arms) |

10 studies (10 arms) SDM 0.52 (0.28 to 0.76) I2 = 80% |

3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.35 (0.12 to 0.59) I2 = 55% |

No data | No data | 3 arms (3 studies) SMD ‐0.08 (‐0.41 to 0.25) I2 = 73% |

No data | No data | As above in ‘all interventions’ |

| Distant interventions | 51 (56 arms) |

14 studies (16 arms) SDM 0.53 (0.32 to 0.75) I2 = 67% |

11 studies (13 arms) SMD 0.79 (0.44 to 1.14) I2 = 87% |

Not analysed | Not analysed | 8 studies (10 arms) SMD 0.05 (‐0.22 to 0.32) I2 = 58% |

Not analysed | Not analysed | |

| Consent on behalf of a minor | 5 (6 arms) |

2 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.55 (0.15 to 0.96) I2 = 13% |

No data | No data | No data | 2 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.14 (‐0.03 to 0.57) I2 = 51% |

No data | No data | No data |

| Self consent | 60 (66 arms) |

20 studies (23 arms) SMD 0.52 (0.36 to 0.69) I2= 75% |

Not analysed | Not analysed | Not analysed | 9 studies (10 arms) SMD ‐0.02 (0.28 to 0.23) I2=72% |

Not analysed | Not analysed | Not analysed |

| Written | 26 (27 arms) |

6 studies (6 arms) SMD 0.29 (‐0.17 to 0.75) I2 = 65%) |

5 studies (6 arms) SMD 0.99 (0.33 to 1.64) I2 = 80% |

8 studies (8 arms) SMD 0.47 (0.21 to 0.73) I2 = 58% |

3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.36 (‐0.17 to 0.89) I2 = 83% |

6 studies (6 arms) SMD 0.02 (‐0.38 to 0.43) I2 = 67% |

No data | 5 studies (6 arms) SMD 0.19 (‐0.29 to 0.67) I2 = 82% |

No data |

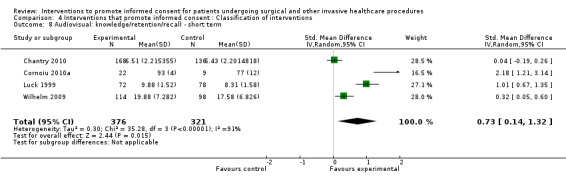

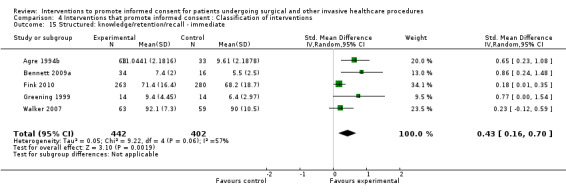

| Audio‐visual | 19 (19 arms) |

8 studies (8 arms) SMD 0.72 (0.40 to 1.04) I2 = 71% |

4 studies (4 arms) SMD 0.73 (0.14 to 1.32) I2 = 91% |

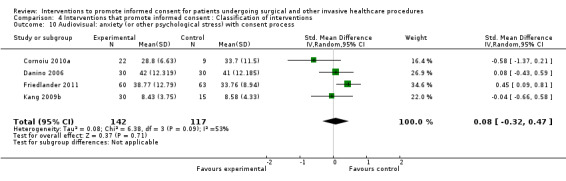

No data | 5 studies (5 arms) SMD ‐0.48 (‐1.07 to 0.12) I2 = 86% |

4 studies (4 arms) SMD 0.08 (‐0.32 to 0.47) I2 = 53% |

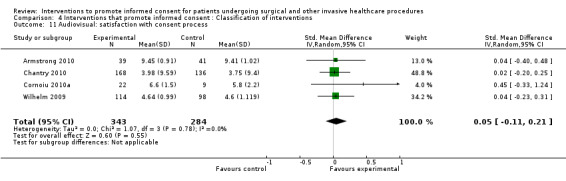

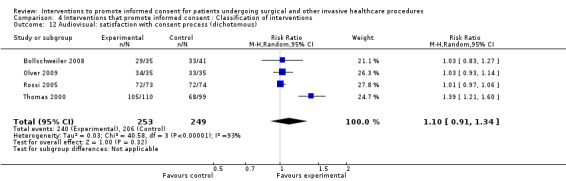

No data | 4 studies (4 arms) SMD 0.05 (‐0.11 to 0.21) I2= 0% Dichotomous data 4 studies RR 1.10 (0.91 to 1.34) I2 = 93% |

No data |

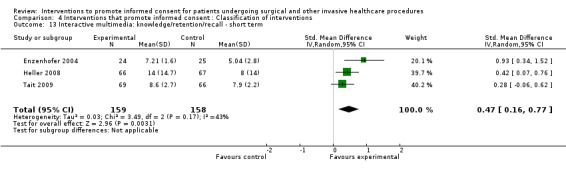

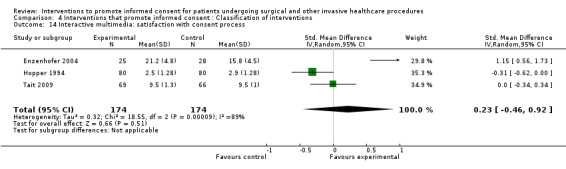

| Interactive multimedia | 6 (6 arms) |

No data | 3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.47 (0.16 to 0.77) I2 = 43% |

No data | No data | No data | No data | 3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.23 (‐0.46 to 0.92) I2 = 89% |

No data |

| Structured consent | 6 (6 arms) |

5 studies (5 arms) SMD 0.43 (0.16 to 0.70) I2 = 57% |

No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

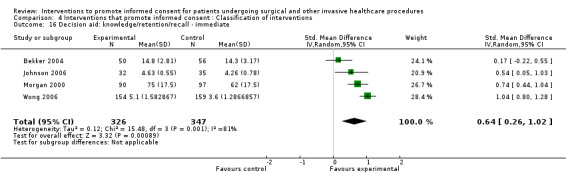

| Decision aids and mixed | 9 (9 arms) |

4 studies (4 arms) SMD 0.64 (0.26 to 1.02) I2 = 81% |

3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.35 (0.12 to 0.59) I2 = 55% |

No data | No data | No data | As above in ‘all interventions’ | No data | 7 studies (7 arms) SMD 2.64 (1.50 to 3.77) I2 = 99% |

| Before admission for procedure | 38 (42 arms) |

8 studies (10 arms ) SDM 0.50 (0.16 to 0.85) I2 = 86% |

Not analysed | Not analysed | Not analysed | 8 studies (10 arms) SMD ‐0.12 (‐0.33 to 0.09) I2= 50% |

3 studies as above in ‘all interventions’ | 7 studies (8 arms) SMD 0.14 (‐0.12 to 0.41) I2= 74% Dichotomous data 4 studies RR 1.12 (0.94 to 1.33) I2 = 91% |

As above in ‘all interventions’ 8 studies |

| During admission for procedure | 24 (27 arms) |

13 studies (15 arms ) SDM 0.55 (0.40 to 0.70) I2 = 40% |

No data | No data | No data | 3 studies (3 arms) SMD 0.41 (0.19 to 0.62) I2= 0% |

No data | 6 studies (6 arms) SMD 0.10 (‐0.26 to 0.46) I2= 81% Dichotomous data 6 studies RR 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) I2 = 4% |

No data |

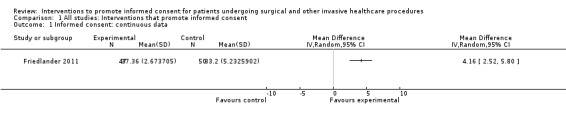

Primary outcome: informed consent

One study with 47 participants in the intervention group and 50 participants in the control group measured informed consent (Friedlander 2011). This study examined the impact of a web‐based learning module for parents of children undergoing endoscopy. The measure of consent was based on a modified questionnaire first published by Woodrow (Woodrow 2006), and included questions to examine the parent’s knowledge of risks, benefits and alternative treatments along with questions which explored if the parent understood what they had been told about risks, benefits, alternatives, their ability to explain what they had been told to another person and if they knew their right to refuse the procedure. A maximum score of 40 was considered to indicate that the participants had given informed consent. The intervention group (47 participants) had a statistically significantly higher mean score than the control group (50 participants) (Intervention group mean 37.4; control group mean 33.2; mean difference 4.16 (95% CI 2.52 to 5.80)) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All studies: Interventions that promote informed consent, Outcome 1 Informed consent: continuous data.

Meta‐analysis for this primary outcome was not possible and the risk of bias was high for most domains, including two of the three deemed most important for this review (randomisation bias and attrition bias), but it was considered at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment.

Secondary outcomes

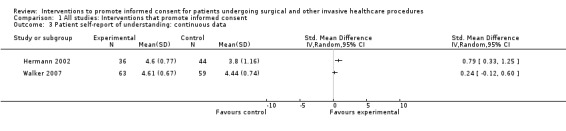

Patient understanding