Abstract

Background

Previous observational studies examining the relationship between cadmium exposure and various cancers have yielded conflicting results. This study aims to comprehensively clarify the relationship between blood cadmium concentration (BCC) and nine specific cancers.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2018 identified 36,991 participants. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between BCC and the risk of nine specific cancers. Additionally, Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses were conducted to investigate potential causal relationships.

Results

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the NHANES data indicated a positive association between BCC and the risk of bladder and lung cancers (P < 0.05) and a negative association with the risk of kidney and prostate cancers (P < 0.05). The MR analyses demonstrated a causal relationship between BCC and kidney cancer (P < 0.05). Additionally, it uncovered causal associations with breast, cervical, and colon cancers (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Elevated BCC was associated with an increased risk of bladder and lung cancers while demonstrating an inverse relationship with kidney and prostate cancers. MR analysis revealed that cadmium exposure may act as a protective factor against breast, cervical, colon, and kidney cancers, that must be confirmed with new studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01692-9.

Keywords: Blood cadmium concentration, Cancer, Mendelian randomization analyses, NHANES

Introduction

Cadmium is a toxic heavy metal prevalent in the environment due to industrial emissions, cigarette smoke, and contaminated food and water, with a half-life of 20 to 30 years [1]. Long-term exposure to cadmium is linked to various adverse health effects, including kidney failure, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease [2]. Additionally, cadmium is classified by the IARC as a Class 1 carcinogen, primarily due to its well-characterized carcinogenic effects in lung cancer [3]. However, the number of studies on certain cancer types is limited, and observational studies have produced varying and inconsistent conclusions.

In recent years, several studies have yielded unexpected conclusions. In two of three prospective cohorts, cadmium exposure was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer, and this association remained negative after meta-analysis [4]. Another cohort study with 261 cases indicated that cadmium levels were a protective factor against prostate cancer [5]. Furthermore, most retrospective studies found no significant association between cadmium exposure and cancer incidence. Even for lung cancer, where evidence was relatively strong, a meta-analysis of three cohort studies in the general population and five in the occupational population did not find a contributing effect of cadmium exposure [6]. Therefore, the relationship between cadmium exposure and some cancers remains unclear.

This study aimed to elucidate the causal relationships between blood cadmium concentration (BCC) and risk of nine specific cancers. To achieve this, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were utilized, and Mendelian randomization (MR) was employed as the analytical approach. The NHANES provides a comprehensive repository of health and nutritional data from a representative sample of the U.S. population, collected through detailed interviews and physical examinations. This extensive dataset includes critical information on blood cadmium, enabling a comprehensive analysis of its potential impact on each of nine cancers.

To reinforce causal inferences and address limitations such as confounding and reverse causation, we utilized MR, which employed genetic variants as instruments to infer causality, offering a robust analytical framework [7]. This combined approach not only enhanced the validity of our findings but also provided valuable insights for developing targeted public health interventions.

Methods

Overall study design

This study comprised two principal components. Initially, the association between BCC and nine prevalent cancers was examined using the NHANES database, with adjustments for numerous confounding variables. Subsequently, Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis was conducted using pooled data from two cohort studies and a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to investigate causality at the genetic level.

Cross-sectional study

Study population

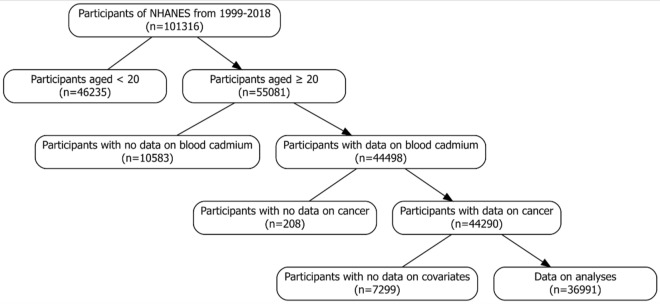

Data for this study were sourced from the NHANES database covering the years 1999–2018. The NHANES, administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), assesses the health and nutritional status of a representative sample of U.S. residents [8]. BCC was quantified for nearly all participants, who also completed a comprehensive questionnaire. After excluding individuals with missing covariate information, a total of 36,991 subjects were included in the analysis. The recruitment process is illustrated in Fig. 1. The survey protocol received approval from the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection of eligible participants in the NHANES

Blood cadmium concentration

BCC was quantified using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). For detailed laboratory procedures, blood sample collection, and processing methods, please refer to the NHANES Laboratory Methods for Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury. Prior to analysis, blood samples underwent a simple dilution step with a diluent consisting of 1 part sample, 1 part water, and 48 parts diluent. Measurements below the limit of detection were adjusted by dividing by the square root of 2. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) guidelines for quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC). For comprehensive QA/QC guidelines, please visit the NHANES Laboratory Procedures Manual.

Cancer status

Cancer data in this study were obtained from NHANES questionnaire surveys. Participants were initially asked whether they had ever been informed of a diagnosis of cancer or malignancy. If they responded affirmatively, they were then asked to specify the type of cancer. Rigorous quality assurance protocols, including standardized interviews and validation procedures, were employed to ensure the accuracy of the data. This approach yielded reliable data on cancer prevalence and incidence, facilitating robust epidemiological research. An example of the questionnaire/interview could be viewed at the website: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015–2016/MCQ_I.htm.

Covariates

This study included several potential confounding variables that may have influenced the observed outcomes, including age, sex, race, education level, annual family income, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI). The specific categorization of each covariate is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by tertiles of BCC

| Baseline characteristics | Tertiles of blood cadmium concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Low | Middle | High | P-value | |

| N | 36,991 | 12,686 | 12,633 | 11,672 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 49.58 (18.08) | 43.87 (16.88) | 52.49 (18.31) | 52.63 (17.60) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (%) | |||||

| Male | 17,837 (48.2) | 7029 (55.4) | 5414 (42.9) | 5394 (46.2) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 19,154 (51.8) | 5657 (44.6) | 7219 (57.1) | 6278 (53.8) | |

| Race (%) | |||||

| Mexican | 6374 (17.2) | 2437 (19.2) | 2496 (19.8) | 1441 (12.3) | < 0.001 |

| White | 16,742 (45.3) | 5695 (44.9) | 5481 (43.4) | 5566 (47.7) | |

| Black | 7557 (20.4) | 2452 (19.3) | 2499 (19.8) | 2606 (22.3) | |

| Other | 6318 (17.1) | 2102 (16.6) | 2157 (17.1) | 2059 (17.6) | |

| Education (%) | |||||

| Less than high school degree | 9864 (26.7) | 2659 (21.0) | 3356 (26.6) | 3849 (33.0) | < 0.001 |

| High school degree | 8582 (23.2) | 2648 (20.9) | 2786 (22.1) | 3148 (27.0) | |

| More than high school degree | 18,545 (50.1) | 7379 (58.2) | 6491 (51.4) | 4675 (40.1) | |

| Annual family income (%) | |||||

| Under $20,000 | 9949 (26.9) | 2625 (20.7) | 3186 (25.2) | 4138 (35.5) | < 0.001 |

| Over $20,000 (include 20,000) | 27,042 (73.1) | 10,061 (79.3) | 9447 (74.8) | 7534 (64.5) | |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||

| Yes | 16,918 (45.7) | 3071 (24.2) | 5046 (39.9) | 8801 (75.4) | < 0.001 |

| No | 20,073 (54.3) | 9615 (75.8) | 7587 (60.1) | 2871 (24.6) | |

| BMI (%) | |||||

| < 25 | 10,869 (29.4) | 3138 (24.7) | 3484 (27.6) | 4247 (36.4) | < 0.001 |

| 25–30 | 12,443 (33.6) | 4194 (33.1) | 4457 (35.3) | 3792 (32.5) | |

| > 30 | 13,679 (37.0) | 5354 (42.2) | 4692 (37.1) | 3633 (31.1) | |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD or as n (%). The tertile ranges were defined as Low (≤ 0.26 μg/L), Middle (0.26 μg/L < BCC ≤ 0.50 μg/L), and High (> 0.50 μg/L). The P-value for differences across BCC tertiles was determined using the χ2 test for categorical variables, ANOVA for continuous variables, or the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-parametric comparisons

Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into three groups based on the tertiles of their BCC: Low, Middle, and High. The chi-square test was utilized to analyze categorical variables, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous variables. Following this, multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore the association between BCC and each of the nine cancers. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.2.1, with a P-value of < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Mendelian randomization

Study design

We conducted a univariable two-sample MR analysis to investigate the potential causal relationship between genetically predicted BCC and nine specific cancers. For the MR analysis to yield reliable inferences regarding causality, three core assumptions must be satisfied: (1) the genetic variants used as instrumental variables should be significantly associated with blood cadmium levels; (2) these genetic variants must be independent of any confounding factors; and (3) they should influence cancer risk exclusively through their impact on blood cadmium levels. This study was conducted and reported following the STROBE-MR guidelines.

Instrumental variables

The instrumental variables (IVs) used to assess BCC were obtained from two studies: the HUNT study [9], which included 6,564 Europeans, and the PIVUS study [10], which included 949 Europeans. Genetic variables were selected as instrumental variables based on the following three criteria [11]: (1) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) significantly associated with blood cadmium levels (P < 5E-6 according to the number of available SNPs); (2) removal of SNPs with linkage disequilibrium (r-squared value < 0.001 in a window of 10,000 kilobases); and (3) retention of strong instrumental variables (computed F-value > 10). Further details regarding the SNPs that were ultimately included can be found in Table S1.

Outcome data

This MR study included nine common cancers with pooled data primarily derived from the UK Biobank, the Finnish Consortium, and the Genetic Consortium. For detailed information on the GWAS data used in this study, please refer to Table S2.

Statistical analysis

The inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method was selected as the primary analysis due to its high statistical power, although it does not account for horizontal pleiotropy. To address potential pleiotropy, we incorporated the weighted median (WM) method and the MR-Egger regression as secondary approaches. The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each standard deviation (SD) increase in cadmium concentrations. Sensitivity analyses were essential to assess potential heterogeneity and pleiotropy. The Cochran Q test was employed for evaluating heterogeneity among the genetic IVs. Vertical pleiotropy was assessed using the MR-Egger regression intercept [12]. Furthermore, leave-one-out (LOO) analyses were performed to determine if any SNPs were exerting a disproportionate influence on the MR estimates. All MR analyses were performed using the R version 4.2.1 and the “TwoSampleMR” R package.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of NHANES

The study analyzed data from 36,991 NHANES participants spanning from 1999 to 2018. Participants were divided into three groups based on BCC tertiles: Low (≤ 0.26 μg/L), Middle (0.26 μg/L < BCC ≤ 0.50 μg/L), and High (> 0.50 μg/L). As shown in Table 1, individuals in the High BCC group were generally older, more likely to be thin women, and predominantly of White ethnicity. This group also tended to have lower educational attainment and income levels, and a higher incidence of smoking.

Relationships of blood cadmium concentration with nine cancers

Table 2 presents the distribution of cancer incidence across BCC tertiles for nine specific cancers. Using three logistic regression models, we evaluated the independent association between BCC and cancer risks. After final multivariate adjustments (Model 3), ORs and 95% CIs for the low, middle, and high cadmium groups were as follows: for bladder cancer, 1 (reference), 2.16 (1.08–4.81), and 3.15 (1.56–7.08) (P = 0.003); for breast cancer, 1, 0.88 (0.69–1.13), and 0.87 (0.67–1.13) (P = 0.299); for cervical cancer, 1 (reference), 0.92 (0.63–1.35), and 1.38 (0.97–2.01) (P = 0.081); for colon cancer, 1 (reference), 1.06 (0.75–1.52), and 1.18 (0.82–1.72) (P = 0.384); for kidney cancer, 1 (reference), 0.44 (0.24–0.80), and 0.77 (0.42–1.40) (P = 0.387); for lung cancer, 1 (reference), 1.50 (0.59–4.61), 3.51 (1.50–10.27) (P = 0.009); for melanoma, 1, 0.72 (0.52–1.01), and 0.71 (0.49–1.02) (P = 0.066); for ovarian cancer, 1 (reference), 0.84 (0.47–1.54), and 1.71 (0.97–3.11) (P = 0.070); and for prostate cancer, 1 (reference), 0.95 (0.76–1.18), and 0.66 (0.51–0.86) (P = 0.002) as shown in Table 3. The analysis confirmed significant differences in bladder cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer between the high and low groups. Notably, a significant difference was also observed between the middle and low groups with regard to kidney cancer.

Table 2.

The distributions of patients with cancer across BCC tertiles

| Total | Low | Middle | High | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 2152 | 501 | 817 | 834 | < 0.001 |

| Bladder cancer | 97 (4.5) | 9 (1.8) | 39 (4.8) | 49 (5.9) | < 0.001 |

| Breast cancer | 505 (23.5) | 109 (21.8) | 208 (25.5) | 188 (22.5) | < 0.001 |

| Cervical cancer | 253 (11.8) | 53 (10.6) | 65 (8.0) | 135 (16.2) | < 0.001 |

| Colon cancer | 257 (11.9) | 49 (9.8) | 102 (12.5) | 106 (12.7) | < 0.001 |

| Kidney cancer | 74 3.4) | 27 (5.4) | 20 (2.4) | 27 (3.2) | 0.411 |

| Lung cancer | 79 (3.7) | 5 (1.0) | 17 (2.1) | 57 (6.8) | < 0.001 |

| Melanoma cancer | 232 (10.8) | 71 (14.2) | 85 (10.4) | 76 (9.1) | 0.482 |

| Ovary cancer | 94 (4.4) | 20 (4.0) | 27 (3.3) | 47 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Prostate cancer | 561 (26.1) | 158 (31.5) | 254 (31.1) | 149 (17.9) | < 0.001 |

Table 3.

HRs (95% CIs) for specific cancers according to BCC

| Blood cadmium | Model 1 OR (95%CI) | P value | Model2 OR (95%CI) | P value | Model3 OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 4.36(2.21–9.61) | < 0.001 | 2.23(1.12–4.95) | 0.032 | 2.16(1.08–4.81) | 0.041 |

| High | 5.94(3.07–12.94) | < 0.001 | 3.33(1.70–7.30) | 0.001 | 3.15(1.56–7.08) | 0.003 |

| Breast cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.93(1.53–2.45) | < 0.001 | 0.88(0.69–1.13) | 0.307 | 0.88(0.69–1.13) | 0.309 |

| High | 1.89(1.49–2.40) | < 0.001 | 0.86(0.67–1.10) | 0.231 | 0.87(0.67–1.13) | 0.299 |

| Cervical cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.23(0.86–1.78) | 0.259 | 1.12(0.78–1.63) | 0.541 | 0.92(0.63–1.35) | 0.669 |

| High | 2.79(2.04–3.87) | < 0.001 | 2.63(1.90–3.68) | < 0.001 | 1.38(0.97–2.01) | 0.081 |

| Colon cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 2.1(1.50–2.98) | < 0.001 | 1.1(0.78–1.58) | 0.581 | 1.06(0.75–1.52) | 0.731 |

| High | 2.36(1.69–3.35) | < 0.001 | 1.27(0.90–1.81) | 0.174 | 1.18(0.82–1.72) | 0.384 |

| Kidney cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 0.74(0.41–1.32) | 0.315 | 0.42(0.23–0.75) | 0.004 | 0.44(0.24–0.80) | 0.008 |

| High | 1.09(0.64–1.86) | 0.759 | 0.64(0.37–1.10) | 0.104 | 0.77(0.42–1.40) | 0.387 |

| Lung cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 3.42(1.35–10.40) | 0.016 | 2.14(0.84–6.55) | 0.139 | 1.5(0.59–4.61) | 0.428 |

| High | 12.45(5.51–35.68) | < 0.001 | 7.68(3.37–22.14) | < 0.001 | 3.51(1.50–10.27) | 0.009 |

| Melanoma cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.2(0.88–1.65) | 0.251 | 0.74(0.53–1.03) | 0.077 | 0.72(0.52–1.01) | 0.053 |

| High | 1.16(0.84–1.61) | 0.358 | 0.73(0.52–1.03) | 0.069 | 0.71(0.49–1.02) | 0.066 |

| Ovary cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.36(0.76–2.45) | 0.302 | 0.84(0.47–1.53) | 0.563 | 0.84(0.47–1.54) | 0.572 |

| High | 2.56(1.54–4.42) | < 0.001 | 1.65(0.98–2.89) | 0.067 | 1.71(0.97–3.11) | 0.070 |

| Prostate cancer | ||||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.63(1.33–1.99) | < 0.001 | 0.9(0.73–1.12) | 0.345 | 0.95(0.76–1.18) | 0.631 |

| High | 1.03(0.82–1.28) | 0.828 | 0.58(0.45–0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.66(0.51–0.86) | 0.002 |

Model 1: Non-adjusted

Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, and race

Model 3: Adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, annual family income, smoking status, and BMI

MR of blood cadmium concentration and nine cancers

To evaluate the impact of BCC on nine different cancers, we conducted two-sample MR analyses. The MR results presented in Table 4 indicated that elevated BCC was associated with a reduced risk of cervical cancer (P = 0.047, OR = 0.924, 95% CI 0.855–0.999) and kidney cancer (P = 0.019, OR = 0.868, 95% CI 0.771–0.977). Furthermore, our findings indicated a potential protective effect against colon and breast cancer, albeit with a relatively modest magnitude (P = 0.008, OR = 0.997, 95% CI 0.995–0.999 for breast cancer and P = 0.038, OR = 1.000, 95% CI 0.999–1.000 for colon cancer). The weighted median and MR-Egger methods produced results consistent with those from the IVW method. Sensitivity analyses, including Cochran’s Q test and MR-Egger intercept, showed no evidence of directional pleiotropy (Table S3). Additionally, MR-PRESSO detected no outliers and confirmed the absence of heterogeneity. LOO analyses further validated these findings (Figure S1). Given the limited number of SNPs associated with blood cadmium, reverse MR analysis was not feasible.

Table 4.

Mendelian randomization analyses results for BCC on cancers

| Outcome | Nsnp | OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 13 | 1.038(0.947–1.138) | 0.423 |

| Weighted median | 13 | 1.011(0.891–1.147) | 0.868 |

| MR Egger | 13 | 1.031(0.888–1.197) | 0.696 |

| Breast cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 11 | 0.997(0.995–0.999) | 0.008 |

| Weighted median | 11 | 0.997(0.994–1.000) | 0.036 |

| MR Egger | 11 | 0.997(0.993–1.000) | 0.123 |

| Cervical cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 12 | 0.924(0.855–0.999) | 0.047 |

| Weighted median | 12 | 0.977(0.874–1.093) | 0.685 |

| MR Egger | 12 | 0.891(0.792–1.002) | 0.082 |

| Colon cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 13 | 1.000(0.999–1.000) | 0.038 |

| Weighted median | 13 | 1.000(0.999–1.000) | 0.146 |

| MR Egger | 13 | 0.999(0.999–1.000) | 0.104 |

| Kidney cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 12 | 0.868(0.771–0.977) | 0.019 |

| Weighted median | 12 | 0.952(0.821–1.104) | 0.517 |

| MR Egger | 12 | 0.917(0.765–1.101) | 0.376 |

| Lung cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 11 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.984 |

| Weighted median | 11 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.908 |

| MR Egger | 11 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.820 |

| Melanoma cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 11 | 1.000(1.000–1.001) | 0.447 |

| Weighted median | 11 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.771 |

| MR Egger | 11 | 1.000(0.999–1.002) | 0.590 |

| Ovary cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 9 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.444 |

| Weighted median | 9 | 1.000(0.999–1.001) | 0.581 |

| MR Egger | 9 | 1.000(0.999–1.002) | 0.604 |

| Prostate cancer | |||

| Inverse variance weighted | 12 | 0.973(0.923–1.027) | 0.323 |

| Weighted median | 12 | 0.975(0.912–1.041) | 0.449 |

| MR Egger | 12 | 0.955(0.878–1.037) | 0.299 |

Statistical significance is highlighted in bold, denoting a p-value of less than 0.05

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the relationship between cadmium exposure and cancers occurring in various parts of the body using a large database combined with MR methods. This study revealed that BCC may produce disparate effects on various types of cancer. On the one hand, the NHANES database indicated that elevated BCC was associated with an increased risk of bladder and lung cancers, while they were inversely associated with the development of kidney and prostate cancers. On the other hand, MR found it to be a protective factor for breast, cervical, colon, and kidney cancers.

As indicated in the introduction, the relationship between cadmium exposure and cancers at various body sites remains unclear due to inconsistent or even conflicting results from cohort studies in recent years. In a study of 509 histologically confirmed breast cancer cases and 1170 controls, Strumylaite et al. identified a significant positive correlation between cadmium exposure and breast cancer risk [13]. In contrast, Gaudet et al. conducted three prospective cohort studies comprising 816, 294, and 325 breast cancer patients, respectively. Their findings indicated no association between cadmium levels and breast cancer risk in the study that included 816 cases. However, the other two studies demonstrated a significant negative association between cadmium exposure and breast cancer risk [4]. Another large cohort study also revealed no correlation between cadmium exposure and breast cancer risk. Notably, a significant negative correlation was identified in the subgroup analysis of ER-/PR- breast cancer [14]. A more recent meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies demonstrated a significant association between elevated cadmium levels and an increased risk of breast cancer. However, the observed heterogeneity was considerable, and after excluding studies with significant heterogeneity, the results indicated no association between cadmium exposure and breast cancer risk [15].

The majority of previous studies have indicated a positive correlation between cadmium levels and the risk of bladder and lung cancer [6, 16–22]. While the MR analysis did not yield significant results. This discrepancy likely stemmed from the MR method's reliance on genetic variants as proxies for cadmium exposure, which might not have been strongly correlated in our analysis. Despite this, the NHANES findings and previous research indicated that cadmium exposure indeed increased bladder and lung cancer risks. The carcinogenic potential of cadmium is partly mediated through its ability to induce oxidative stress and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to DNA damage, disruption of cellular homeostasis, and aberrant gene expression [23]. Moreover, cadmium can act as an endocrine disruptor by mimicking estrogen, thereby influencing hormone-sensitive cancer development, such as breast and prostate cancers [24]. These mechanisms are further modulated by the body's trace element balance; for instance, copper's pro-oxidant properties can exacerbate cadmium-induced oxidative damage, while selenium’s antioxidant function may counteract it [25]. The interplay between these elements can significantly affect cancer susceptibility and progression. For prostate cancer, Julin et al. prospectively followed 41,089 men to assess the association between cadmium-based exposures and prostate cancer incidence and found that cadmium exposure was significantly associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer [26]. Similar results were obtained in the study by Nam et al. [27]. But three meta-analyses have suggested no association between cadmium exposure and prostate cancer risk [28–30]. As for kidney cancer, Song et al. conducted a meta-analysis of nine case–control studies and one prospective cohort study, which demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation between cadmium exposure and the risk of developing renal cancer [31]. These findings are contrary to our own, as the meta-analysis included primarily occupational populations with high-risk exposures, who often have considerably higher cadmium levels than the general population. Consequently, the observed effects differed between the general population and this occupational cohort. Although in two observational studies, Wu et al. found no association between cadmium exposure and renal cancer risk in smokers [32], whereas Hsueh et al. reported that, after adjusting for smoking and other factors such as age, sex, and alcohol consumption, there was no significant association between cadmium exposure and kidney cancer risk in the general population [33]. In addition, the number of available studies for other types of cancer is insufficient to permit the drawing of conclusions. The dualistic nature of cadmium's impact on cancer may be linked to its interactions with the body's oxidative stress response and trace element homeostasis. While cadmium exposure promotes ROS formation and DNA damage, trace elements such as selenium and zinc play protective roles by enhancing cellular antioxidant capacity and stabilizing DNA structure [34, 35]. Recent studies underscore that antioxidant defenses mediated by these trace elements can influence cancer susceptibility and patient outcomes [36, 37]. Thus, cadmium’s role in cancer risk and progression may depend on the balance of these elements, the genetic makeup of the individual, and the presence of other environmental stressors. This perspective is critical for interpreting why cadmium may act as both a carcinogen and a protective factor under different biological contexts.

The inconsistency in the preexisting results can be attributed to three primary factors. First, recall bias is an inherent limitation in observational studies, as participants may not accurately remember or report past behaviors and exposures, leading to misclassification and biased estimates. Second, despite rigorous adjustment methods, the influence of confounding factors cannot be entirely eradicated. These confounders may introduce significant variability and obscure the true associations between variables of interest. Third, the phenomenon of reverse causation, where the outcome influences the exposure, complicates the interpretation of observational data. To address these limitations, MR offers a robust alternative. By leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables, MR can effectively mitigate recall bias, control for confounding factors, and establish a more reliable direction of causality. Consequently, MR studies provide more compelling and credible evidence, enhancing the validity and generalizability of the findings.

Our study, while employing novel MR methods to explore the relationship between cadmium exposure and specific cancer types, has several limitations. Firstly, this study uses a single measurement of BCC, which may not capture long-term cadmium exposure accurately, especially given cadmium's prolonged half-life and potential accumulation over time. Multiple measurements over time would provide a more reliable assessment of chronic cadmium exposure and its role in cancer risk. And our primary participants were exclusively of European ancestry. Although this minimizes bias from population heterogeneity, it also limits the generalizability of our findings to other populations, warranting further investigation. Secondly, to increase the number of SNPs, we relaxed the p-threshold between instrumentation and exposure, which could potentially violate the first assumption of the MR design. However, the fact that the F-statistic for each SNP exceeded 10 suggests that weak instruments were not included in our analysis. Thirdly, we could not completely eliminate pleiotropy since the specific biological functions of the SNPs remain unknown. Nonetheless, the consistency of estimates across different MR models and the results of sensitivity analyses, which did not detect pleiotropy, provide some reassurance about the robustness of our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study represents a significant advancement in understanding the complex relationship between cadmium exposure and cancer risk. We identified that elevated BCC was associated with an increased risk of bladder and lung cancers while demonstrating an inverse relationship with kidney and prostate cancers. Additionally, MR analysis revealed that cadmium exposure may act as a protective factor against breast, cervical, colon, and kidney cancers. These findings reconcile some of the inconsistencies observed in previous observational studies and highlight the potential of MR to provide more robust and causally informative insights. Nevertheless, the favorable results of MR should not be used to underestimate the hazards of cadmium exposure. Sufficient efforts should be made to reduce cadmium exposure, and more research is needed to supplement and further elucidate the association between cadmium exposure and various types of cancers in the future.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support and resources provided by the NHANES database and sincerely thank all the projects who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- BCC

Blood cadmium concentration

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- ICP-MS

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- CLIA

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

- QA/QC

Quality assurance and quality control

- BMI

Body mass index

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- IVs

Instrumental variables

- SNPs

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- IVW

Inverse-variance weighted

- WM

Weighted median

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- SD

Standard deviation

- LOO

Leave-one-out

Author contributions

LL was the principal investigator, overseeing the study's design, analysis, and manuscript preparation. JW was pivotal in data collection and initial drafting. SD focused on statistical analysis and drafting critical sections. GC and BW were essential for editing the manuscript. YW, YS, KX, and JC assisted with literature review. SH provided critical input during the revision phase and contributed extensively to the interpretation, and substantial enhancements to the discussion sections. All authors collaborated on finalizing and approving the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 2022M722680, Jiangsu provincial Science and Technology Program, Grant/Award Number: BK20231169 and High-level Hospital Construction Project of Jiangsu Province, Grant/Award Number: LCZX202402.

Data availability

Data collected and analyzed in this study are available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. The remaining data from the study can be found in the article and supplementary materials. Should further clarification be required, the corresponding author can be contacted.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NHANES protocols were authorized by the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all NHANES participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jiang Wang and Sijia Deng have contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Shuguang Han, Email: hsgxyfy@163.com.

Liantao Li, Email: liliantao@xzhmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Branca JJV, Morucci G, Pacini A. Cadmium-induced neurotoxicity: still much ado. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(11):1879–82. 10.4103/1673-5374.239434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Urinary cadmium and mortality from all causes, cancer and cardiovascular disease in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):782–91. 10.1093/ije/dyv086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straif K, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V, WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens–part C: metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):453–4. 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaudet MM, Deubler EL, Kelly RS, Ryan Diver W, Teras LR, Hodge JM, Levine KE, Haines LG, Lundh T, Lenner P, Palli D, Vineis P, Bergdahl IA, Gapstur SM, Kyrtopoulos SA. Blood levels of cadmium and lead in relation to breast cancer risk in three prospective cohorts. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(5):1010–6. 10.1002/ijc.31805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YC, Pu YS, Wu HC, Wu TT, Lai MK, Yang CY, Sung FC. Cadmium burden and the risk and phenotype of prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:429. 10.1186/1471-2407-9-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Xun P, Nishijo M, He K. Cadmium exposure and risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies among general and occupational populations. J Eposure Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2016;26(5):437–44. 10.1038/jes.2016.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Higgins JPT, Timpson NJ, Dimou N, Langenberg C, Golub RM, Loder EW, Gallo V, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Egger M, Richards JB. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614–21. 10.1001/jama.2021.18236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011–2014. Vital Health Stat Series 2 Data Evaluat Methods Res. 2014;162:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moksnes MR, Hansen AF, Wolford BN, Thomas LF, Rasheed H, Simić A, Bhatta L, Brantsæter AL, Surakka I, Zhou W, Magnus P, Njølstad PR, Andreassen OA, Syversen T, Zheng J, Fritsche LG, Evans DM, Warrington NM, Nøst TH, Åsvold BO, Brumpton BM. A genome-wide association study provides insights into the genetic etiology of 57 essential and non-essential trace elements in humans. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):432. 10.1038/s42003-024-06101-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng E, Lind PM, Lindgren C, Ingelsson E, Mahajan A, Morris A, Lind L. Genome-wide association study of toxic metals and trace elements reveals novel associations. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(16):4739–45. 10.1093/hmg/ddv190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess S, Small DS, Thompson SG. A review of instrumental variable estimators for Mendelian randomization. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26(5):2333–55. 10.1177/0962280215597579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):30–42. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strumylaite L, Kregzdyte R, Bogusevicius A, Poskiene L, Baranauskiene D, Pranys D. Cadmium exposure and risk of breast cancer by histological and tumor receptor subtype in white caucasian women: a hospital-based case-control study. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):3029. 10.3390/ijms20123029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amadou A, Praud D, Coudon T, Danjou AMN, Faure E, Leffondré K, Le Romancer M, Severi G, Salizzoni P, Mancini FR, Fervers B. Chronic long-term exposure to cadmium air pollution and breast cancer risk in the French E3N cohort. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(2):341–51. 10.1002/ijc.32257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florez-Garcia VA, Guevara-Romero EC, Hawkins MM, Bautista LE, Jenson TE, Yu J, Kalkbrenner AE. Cadmium exposure and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2023;219: 115109. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.115109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung CJ, Chang CH, Liou SH, Liu CS, Liu HJ, Hsu LC, Chen JS, Lee HL. Relationships among DNA hypomethylation, Cd, and Pb exposure and risk of cigarette smoking-related urothelial carcinoma. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;316:107–13. 10.1016/j.taap.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feki-Tounsi M, Olmedo P, Gil F, Khlifi R, Mhiri MN, Rebai A, Hamza-Chaffai A. Cadmium in blood of Tunisian men and risk of bladder cancer: interactions with arsenic exposure and smoking. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013;20(10):7204–13. 10.1007/s11356-013-1716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu HT, Lee HL, Cheng HH, Chang CH, Liu CS, Hsiao PJ, Chang H, Lien CS, Chung MC, Chung CJ. Relationships of multiple metals exposure, global DNA methylation, and urothelial carcinoma in central Taiwan. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96(6):1893–903. 10.1007/s00204-022-03260-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cigan SS, Murphy SE, Stram DO, Hecht SS, Marchand LL, Stepanov I, Park SL. Association of urinary biomarkers of smoking-related toxicants with lung cancer incidence in smokers: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent. 2023;32(3):306–14. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee NW, Wang HY, Du CL, Yuan TH, Chen CY, Yu CJ, Chan CC. Air-polluted environmental heavy metal exposure increase lung cancer incidence and mortality: a population-based longitudinal cohort study. Sci Total Environ. 2022;810: 152186. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lener MR, Reszka E, Marciniak W, Lesicka M, Baszuk P, Jabłońska E, Białkowska K, Muszyńska M, Pietrzak S, Derkacz R, Grodzki T, Wójcik J, Wojtyś M, Dębniak T, Cybulski C, Gronwald J, Kubisa B, Pieróg J, Waloszczyk P, Scott RJ, Lubiński J. Blood cadmium levels as a marker for early lung cancer detection. J Trace Element Med Biol. 2021;64:126682. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nawrot T, Plusquin M, Hogervorst J, Roels HA, Celis H, Thijs L, Vangronsveld J, Van Hecke E, Staessen JA. Environmental exposure to cadmium and risk of cancer: a prospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(2):119–26. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;160(1):1–40. 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Psaltis JB, Wang Q, Yan G, Gahtani R, Huang N, Haddad BR, Martin MB. Cadmium activation of wild-type and constitutively active estrogen receptor alpha. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1380047. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1380047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubiński J, Lener MR, Marciniak W, Pietrzak S, Derkacz R, Cybulski C, Gronwald J, Dębniak T, Jakubowska A, Huzarski T, Matuszczak M, Pullella K, Sun P, Narod SA. Serum Essential elements and survival after cancer diagnosis. Nutrients. 2023;15(11):2611. 10.3390/nu15112611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julin B, Wolk A, Johansson JE, Andersson SO, Andrén O, Akesson A. Dietary cadmium exposure and prostate cancer incidence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(5):895–900. 10.1038/bjc.2012.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam Y, Park S, Kim E, Lee I, Park YJ, Kim TY, Kim MJ, Moon S, Shin S, Kim H, Choi K. Blood Pb levels are associated with prostate cancer prevalence among general adult males: linking national cancer registry (2002–2017) and KNHANES (2008–2017) databases of Korea. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2024;256: 114318. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2023.114318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Farahmandian P, Fadaei A, Sadeghi R. Investigating the relationship between cadmium exposure and the risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2024;53(3):553–67. 10.18502/ijph.v53i3.15136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, Xun P, Nishijo M, Carter S, He K. Cadmium exposure and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies among the general and occupational populations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25814. 10.1038/srep25814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ju-Kun S, Yuan DB, Rao HF, Chen TF, Luan BS, Xu XM, Jiang FN, Zhong WD, Zhu JG. Association between Cd exposure and risk of prostate cancer: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(6): e2708. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song JK, Luo H, Yin XH, Huang GL, Luo SY, Lin DUR, Yuan DB, Zhang W, Zhu JG. Association between cadmium exposure and renal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17976. 10.1038/srep17976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu H, Weinstein S, Moore LE, Albanes D, Wilson RT. Coffee intake and trace element blood concentrations in association with renal cell cancer among smokers. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(1):91–9. 10.1007/s10552-021-01505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsueh YM, Lin YC, Huang YL, Shiue HS, Pu YS, Huang CY, Chung CJ. Effect of plasma selenium, red blood cell cadmium, total urinary arsenic levels, and eGFR on renal cell carcinoma. Sci Total Environ. 2021;750: 141547. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Złowocka-Perłowska E, Baszuk P, Marciniak W, Derkacz R, Tołoczko-Grabarek A, Słojewski M, Lemiński A, Soczawa M, Matuszczak M, Kiljańczyk A, Scott RJ, Lubiński J. Blood and serum Se and Zn levels and 10-year survival of patients after a diagnosis of kidney cancer. Biomedicines. 2024;12(8):1775. 10.3390/biomedicines12081775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietrzak S, Marciniak W, Derkacz R, Matuszczak M, Kiljańczyk A, Baszuk P, Bryśkiewicz M, Sikorski A, Gronwald J, Słojewski M, Cybulski C, Gołąb A, Huzarski T, Dębniak T, Lener MR, Jakubowska A, Kluz T, Scott RJ, Lubiński J. Correlation between selenium and zinc levels and survival among prostate cancer patients. Nutrients. 2024;16(4):527. 10.3390/nu16040527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matuszczak M, Kiljańczyk A, Marciniak W, Derkacz R, Stempa K, Baszuk P, Bryśkiewicz M, Sun P, Cheriyan A, Cybulski C, Dębniak T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Lener MR, Jakubowska A, Szwiec M, Stawicka-Niełacna M, Godlewski D, Prusaczyk A, Jasiewicz A, Lubiński J. Zinc and its antioxidant properties: the potential use of blood zinc levels as a marker of cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Antioxidants. 2024;13(5):609. 10.3390/antiox13050609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matuszczak M, Kiljańczyk A, Marciniak W, Derkacz R, Stempa K, Baszuk P, Bryśkiewicz M, Cybulski C, Dębniak T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Lener M, Jakubowska A, Szwiec M, Stawicka-Niełacna M, Godlewski D, Prusaczyk A, Jasiewicz A, Kluz T, Tomiczek-Szwiec J, Lubiński J. Antioxidant properties of zinc and copper-blood zinc-to copper-ratio as a marker of Cancer risk BRCA1 mutation carriers. Antioxidants. 2024;13(7):841. 10.3390/antiox13070841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and analyzed in this study are available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. The remaining data from the study can be found in the article and supplementary materials. Should further clarification be required, the corresponding author can be contacted.