Abstract

Flavor is a significant factor in determining the popularity of freshwater fish. However, freshwater fish can easily spoil during storage, producing an unpleasant odor. Little research has determined the changes in key off-odor compounds (OOCs) in freshwater fish during storage. In this study, quantitation and odor activity value (OAV) calculations revealed that 19 odorants were important volatile odor compounds in fresh, spoilage, and serious spoilage GCC. Recombination and omission experiments verified that (E)-2-hexenal, acetoin, N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine, trimethylamine (TMA), and ammonia were the key OOCs in spoilage GCC. Additional key OOCs in serious spoilage GCC were cyclohexane isothiocyanato, butylated hydroxytoluene, putrescine, cadaverine and histamine compared to those of spoilage GCC. Correlation analysis showed that 12 amino acids and 10 fatty acids played important roles in the formation of key OOCs. This study provides a theoretical basis for a comprehensive understanding of the formation of key OOCs in GCC during room temperature storage.

Keywords: Grass carp cube, Key off-odor compounds, Molecular sensory science, GC-O-MS, Volatile amines, Aroma recombination and omission

Highlights

-

•

Totally 10 key OOCs formed in GCC during room temperature storage were identified.

-

•

BAs, TMA, and ammonia occupied important positions in the odor deterioration of GCC.

-

•

12 FAAs and 10 FAAs played important roles in the formation of key OOCs.

1. Introduction

Freshwater fishes are the most widely consumed aquatic products in China because of their rapid growth rate, high yields, and abundant nutrients. In 2023, approximately 5.94 million tonnes of grass carp were produced, the highest among all freshwater fishes (2024). Flavor is a decisive factor influencing customer popularity. However, grass carp is highly perishable during storage because of its high moisture content, endogenous enzyme action, and microbial growth (Tao Huang et al., 2020; Zhenlei Liu, Huamao, Deng, Xunxin, & Huang, 2023; Zhuang et al., 2023), which directly affect odor. Off-odor substances formed during storage drastically influence the odor profile of grass carp, thereby decreasing consumer acceptability. Deterioration of freshwater fish is driven by protein degradation, lipid oxidation, and microbial metabolism.(Rong Yang et al., 2020; Sharma, Majumdar, Mehta, Panda, & Ngasotter, 2024) Numerous studies on the changes in volatile odor compounds (VOCs) in freshwater fish during storage have been reported (Mahmoud, Magdy, Tybussek, Barth, & Buettner, 2023; Raju Podduturi, Reinaldo, Hyldig, Jørgensen, & Petersen, 2023), and these studies have mainly focused on the identification and quantitation of VOCs by gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O), gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS), and two-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC × GC–MS). Nevertheless, the key OOCs were not identified, and no recombination or omission experiments were conducted to validate these findings. Therefore, there remains a lack of rigorous and comprehensive research exploring the key OOCs in freshwater fish during storage to obtain better quality and flavor.

Volatile amines in freshwater fish include biological amines (BAs), TMA, and dimethylamine (DMA). These compounds often used to represent the degree of spoilage of freshwater fish (Keli Zhong et al., 2024); however, the contribution of volatile amines to the odor profile of freshwater fish is normally not appreciable. Low volatile amine content contributes little to the odor profile of freshwater fish, although, a significantly undesirable odor was produced when the concentrations of volatile amines were accelerated in the tissues. In recent studies, TMA was normally included in the odor profiles of aquatic products, whereas BAs and ammonia were not. As a class of low-molecular-weight compounds containing amino groups with biological activity, BAs are mainly produced by amino acid decarboxylation or the amination of carbonyl-containing organic compounds by microorganisms (Mohammed, Darwish, Darwish, & Saad, 2021). TMA is generally considered to be the product of trimethylamine oxide under the action of spoilage bacteria, which can give a fishy odor to freshwater fish (Raju Podduturi et al., 2023). In addition, ammonia is the final product of protein degradation (Habibeh Hashemian et al., 2023). To study the key OOCs of GCC systematically, BAs, TMA, and ammonia were determined to assess their contributions to the overall odor profile of GCC.

The “molecular sensory science” technology proposed by Professor Shieberle's team has been widely used in the food flavor research to identify and validate the key VOCs of food substances. Molecular sensory science primarily involves volatile compound extraction, concentration, artificial sniffing, identification, quantitation, OAV calculation, and odor reconstruction. Finally, key VOCs were identified through omission experiments. Zhou et al. used molecular sensory science to characterize the key aroma substances of black tea at different fermentation stages and found that eight components, including phenylacetaldehyde and (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal, were the main contributors to the aroma differences between different degrees of fermentation.(Zhou et al., 2023) In addition, Lin reported that β-damascenone, 2-furfuryl ethyl ether, and ethyl hexanoate were the key aroma compounds of Chinese texiang aroma-type baijiu by molecular sensory science.(Lin et al., 2024).

Few studies have focused on exploring the key OOCs of GCC during storage using molecular sensory science. In this study, the VOCs in GCC during storage were identified and quantitated by GC-O-MS, and the key OOCs were validated through aroma recombination and omission experiments. This work provides a deeper understanding of the key OOCs in GCC, helping improve and control the quality of GCC during storage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

The grass carp (weight: 2.5 ± 0.2 kg) used in this experiment were purchased from Baijiahui Market (Nanchang, China) in August, and were placed in a tank filled with clean water and transported to the laboratory alive. The grass carps were killed using percussive stunning, decapitation, and evisceration, and then cut into cubes measuring approximately 3 × 3 × 2 cm. Only muscles from the back area were used in the experiment. The cubes were placed in a sterile polyethylene bag and put in incubator under room temperature (25 ± 1 °C).

2.2. Chemicals

Standard aromatic compounds were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), Absin (Shanghai, China), and Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reagents were of analytical or chromatography grade. Additionally, a C8-C40 n-alkane mixture (Tanmo, Changzhou, China) was used to calculate the retention index (RI) of the detected aroma compounds, and mixed standard solutions of 37 fatty acid methyl esters were used to identify the fatty acids.

2.3. Determination of total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) value

TVB-N was determined according to the Chinese Standard GB5009.228–2016 (China, 2016b). Briefly, 5 g of the homogenized sample and 0.5 g of magnesium oxide were blended with 50 mL of distilled water. A K9860 fully automatic Kjeldahl Apparatus (Hanon Instruments, China) and 20 g/L boric acid were used for determination, and 0.01 M hydrochloric acid was used for titration. The TVB-N value was determined based on the amount of hydrochloric acid consumed.

2.4. Determination of volatile amines

2.4.1. BAs

Homogenized sample was immersed in 5 % trichloroacetic acid to extract BAs for two cycles and then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. n-Hexane was used to clean the fat; subsequently, 2 M sodium hydroxide solution, saturated sodium bicarbonate solution, and danacyl chloride solution were added and the mixture was kept at 40 °C and away from light for the reaction. 25 % ammonium hydroxide was added to terminate the reaction and acetonitrile was added to bring the volume to 5 mL. The mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, filtered through a 0.45 mm membrane filter, and stored at −20 °C for further analysis.

A high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) with an ultraviolent (UV) detector combined with C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm × 5 μm, Waters Corporation, USA) was used to determine the content of BAs. The operating conditions were as follows: column temperature was 30 °C, moving phase A was 0.1 M ammonium acetate, moving phase B was acetonitrile, sample (20 μL) was injected at a flow rate at 0.8 mL/min, and the peak was detected at 254 nm.

2.4.2. Amine value and TMA

A detection kit (A086-1-1, Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) was used to determine the amine value, and the method was referenced to the specifications. About 0.2 mL sample was mixed with 1 mL protein precipitator A and 1 mL protein precipitator B, then mixed and centrifuged at 7000 r/min for 10 min. Subsequently, 1 mL supernatant was mixed with 1 mL color developing agent A and 1 mL color developing agent B. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min, and then detected at 630 nm. Where 0.2 mL standard diluent and standard application solution replaced sample as blank and standard.

The determination method of TMA was selected according to the Chinese Standard GB5009.179–2016 (China, 2016a). In brief, 10 g sample was mixed with 20 mL 5 % trichloroacetic acid solution, follwed by homogenzed at 8000 r/min for 1 min, and then centrifuged at 4000 r/min for 5 min. About 2 mL supernatant with 5 mL 50 % sodium hydroxide solution were equilibrated at 40 °C for 40 min, and then 100 μL gas from the headspace of bottle was extracted and injected into GC–MS for determination. An Agilent 8890 GC System coupled with an Agilent 5977 B MSD detector (Agilent Technologies, USA) were used for TMA analysis, an DB-WAX column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, USA) was used for detection. Flow rate was set as 1.0 mL, helium as carrier gas, the temperature of the inlet was 220 °C, and the temperature program was: 40 °C held for 3 min, then increased to 220 °C at a rate of 30 °C/min, held for 1 min.

2.5. Free amino acids (FAAs) and free fatty acids (FFAs) analysis

The FAAs composition was determined according to the method reported by Lei, Ke, Huo, Yang, and Liang (2023) About 25 mg sample and 250 μL water freeze-ground for 6 min, and then sonicated at 40 kHz for 30 min and centrifuged at 11000 r/min for 5 min. The supernatant was diluted with 100 μL acetonitrile and centrifuged for 5 min. Then, the supernatant was diluted and then analyzed. An LC-ESI-MS/MS coupled with a ExionLC AD system and a Waters BEH Amide column (100 × 2.1 mm2 × 1.7 μm) were used for detection. The mass spectrometry conditions were performed using an AB SCIEX QTRAP 6500+.

The determination method of FFAs composition was referred to Lei et al. (2023) in which a fatty acid mixed standard was used for identification, and nonadecanoic acid was used as an internal standard for quantitation. About 50 mg sample and 1 mL dichloromethane/methanol (v/v = 1:1) were ground for 3 min and then the sample was sonicated for 15 min, ground and at −20 °C for 15 min, and centrifuged at 11000 r/min for 10 min. Next, 500 μL supernatant was blown dry with nitrogen, and then mixed with 0.5 mL 0.5 mol/L sodium hydroxide methanol solution, water bathed at 60 °C for 30 min. After cooled, 0.5 mL n-hexane was added and centrifuged at 11000 r/min for 10 min, and 100 μL upper layer was used for GC–MS analysis. An 8890-7000D GC–MS detector coupled with a DB-FAST FAME column (20 m × 0.18 mm × 0.2 μm, Agilent, USA) was used for detection. The carrier gas and flow rate were same as TMA detection, the temperature program was as follow: the initial temperature was 80 °C for 0.5 min, then increased at a rate of 70 °C /min to 175 °C, subsequently, ramped up to 230 °C at 8 °C /min and held for 1 min, finally kept at 80 °C for 2 min.

2.6. Sensory analysis for odor profile

Sensory analysis was performed according to the method reported by Shen et al. (2023) with some modifications. The experiments were conducted using a group of ten members (six females and four males) from Jiangxi Normal University. Before the formal experiment, the participants received perception training four times a week. Seven attributes were defined as the following flavor references: trimethylamine hydrochloride for “fishy” attribute, 1-octen-3-ol for “mushroom” attribute, hexenal for “grassy” attribute, butyric acid for “odor” attribute, ferric oxide for “metallic” attribute, acetic acid for “sour” attribute, and ammonium hydroxide for “ammoniacal” attribute. A ten-point interval scale was used to describe the odor profile of GCCs, where 0 represented imperceptible, 1 represented weak, 5 represented significant, and 9 represented extremely strong. Ethical guidelines, legal requirements, and the privacy rights of participants were observed. Experiments has been granted by college and conducted with the knowledge and consent of the participants, and all data was used only with the explicit consent of the participants.

2.7. Aroma extraction by solvent-assisted flavor evaporation (SAFE)

The GCC was smashed and then immersed in 150 mL methylene dichloride for 6 h. The supernatant was retained and extracted twice. Subsequently, the organic layer was distilled using the SAFE technique at 45 °C under high vacuum. Anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) was added to the SAFE fraction for dehydration, and then the SAFE fraction was concentrated to 2 mL for analysis.

2.8. Aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA)

The original odor concentrate of extract was stepwise diluted with methylene dichloride to 1:2n (n = 1–8) until no odorant could be sniffed, and aliquots (1 μL) of each fraction were analyzed by GC-O-MS. Three trained sensory panelists were recruited to complete the test, and the flavor dilution factor (FD) was defined as the maximum dilution at which VOCs could be detected.

2.9. GC-O-MS analysis

The GCC was analyzed by GC–MS using an Agilent 8890 GC System equipped with an Agilent 5977 B MSD detector (Agilent Technologies, USA). The method used for GC–MS was consistent with that used by Hu, Jiang, Wang, Li, and Tu (2023) Separations were performed on two different polarity columns: DB-WAX for polar (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, USA) and HP-5 MS UI (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, USA) for non-polar. Helium was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The oven temperature was programmed from an initial temperature of 40 °C, held for 3 min, increased to 240 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, and then held at 240 °C for 15 min. 1 μL of sample was injected into the GC at a temperature of 250 °C, mass spectra were collected from 35 to 350 m/z, and the instrument was operated in electron ionization (EI) mode with 70 eV electron impact energy.

GC-O analysis was performed using a sniffer 9100 system (Brechbühler AG, Switzerland). Three experienced assessors described the odors of the VOCs; only the compounds smelled by two or three evaluators were identified as odor-active substances. The sniffing time was approximately 51 min, and the program settings for the temperature were consistent with those described above.

The identification of VOC was performed by comparing odor description, retention indice (RI), retention times (RT) coupled with mass spectra (MS) to standard. The calculation of RI was as follow:

where ti was the retention time of VOC detected; tn was the retention time of Cn; tn+1 was the retention time of Cn+1.

The standard was diluted with dichloromethane to 6 different standard concentrations, and then determined by GC–MS and obtained the calibration curve of each VOC for quantitation. The calibration curves of VOCs were shown in Table S1.

2.10. Determination of odor thresholds and OAVs calculation

The odor thresholds of VOCs referred to the book (Gemert, 2015), and those who could not be found were determined according Czerny et al. (2008). The OAVs of the volatile compounds were calculated as the concentration of the compound and its aroma threshold recorded in the literature or determined in this study.

2.11. Aroma reconstitution and aroma omission experiments

Before the aroma reconstitution experiment, the odorless matrix was prepared as follows: mashed GCC was mixed with diethyl ether and pentane in a 2:1:1 (m/m/m) ratio until no odor could be detected.(Chen, Liu, Li, Xu, & Xu, 2024) Then, the VOCs with OAV ≥ 1 were added to the odorless matrix in a brown weighing bottle according to the original concentrations. The sensory assessment group was 10 experienced panelists, as previously mentioned. Panelists evaluated the similarity between the recombinant and original samples using sensory analysis.

For omission tests, model aroma mixtures were prepared by deleting one compound from the complete recombination system. Panelists were required to distinguish the omission model from the two fully reconstituted samples using a triangulation test. The significance of omission experiments was according to sensory analysis dictionary: 9 or 10 of ten panelists could distinguish the omission model correctly was defined as very highly significant (P < 0.001); 8 and 7 of ten panelists could distinguish the omission model correctly were defined as highly significant (P < 0.01) and significant (P < 0.05), respectively; 6 or less panelists could distinguish the omission model correctly was defined as not significant (P > 0.05).

2.12. Statistical analysis

All experiments and samples were performed in triplicate, and the results were presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). One-way analysis of variance with Duncan's multiple comparison test was performed using the SPSS software (version 16.0; International Business Machines Corporation, USA). Figures were painted with Origin 2019b (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) and Chemdraw Ultra 7.0 (Perkin Elmer, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Changes of TVB-N values

TVB-N is mainly composed of ammonia and primary, secondary, and tertiary amines; the concentrations of these compounds are typically used to reflect the freshness of meat products. In general, 20 mg/100 g is regarded as the critical value for the consumption of aquatic products, according to the Chinese Standard (GB 2733–2015).(Andre et al., 2022) In this study, five points were selected to characterize different degrees of freshness: fresh, within the critical value, reaching the critical value, exceeding 20 % of the critical value, exceeding 50 % of the critical value, and exceeding 100 % of the critical value. Several different time points, T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5, were selected through preliminary experimentation to be 0, 7, 13, 18, 21, and 28 h, respectively. The TVB-N values are shown in Table 1 and all met the expectations. These results were in agreement with that of Senapati et al., (Mukut Senapati, 2020) who observed that the TVB-N values of Tilapia at 0, 7, 12, 18 and 21 h were about 13, 17, 22, 28 and 31 mg/100 g at 25 °C. The increase in TVB-N values is closely related to the decomposition of biological macromolecules, such as proteins and fats, by microorganisms and enzymes to produce basic nitrogen-containing substances including ammonia and amines.(Huang et al., 2022) Generally, an increase in the TVB-N value corresponds to an enhancement of the unpleasant odor of the sample and an increase in the variety and concentration of VOCs. (See Fig. 1, Fig. 2.)

Table 1.

Changes of TVB-N values in GCC during room temperature storage.

| Number | Time/h | TVB-N/mg•100 g−1 |

|---|---|---|

| T0 | 0 | 12.51 ± 0.22 |

| T1 | 7 | 16.73 ± 0.68 |

| T2 | 13 | 20.81 ± 0.15 |

| T3 | 18 | 25.18 ± 0.35 |

| T4 | 21 | 34.76 ± 0.34 |

| T5 | 28 | 87.20 ± 0.73 |

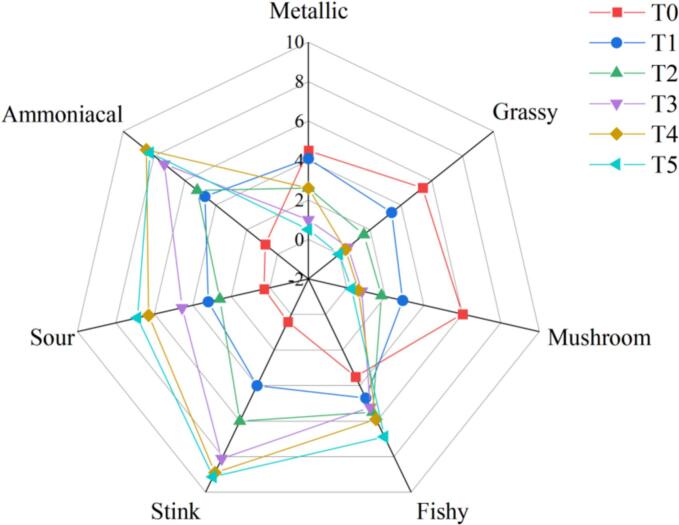

Fig. 1.

Odor profile of GCC during room temperature storage.

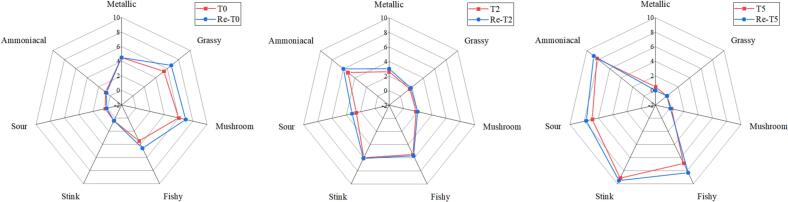

Fig. 2.

Comparative odor profile analysis of T0, T2, T5 and Re-T0, Re-T2, Re-T5.

3.2. Sensory analysis for odor profile

During room temperature storage, the odorants produced by GCCs were found to have seven odor attributes. In general, the metallic, grassy, and mushroom attributes decreased significantly as storage time extended (P < 0.05), and the attributes of fishy, stink, sour, and ammoniacal increased significantly (P < 0.05). At T0, the GCC was fresh, and the metallic, grassy, and mushroom scores were 4.5, 5.4, and 6.0, respectively, whereas the stink (0.4), sour (0.3), and ammoniacal (0.8) scores were all less than 1.0. At T1, the attributes including stink (4.0), sour (3.2), ammoniacal (4.7), and fishy (4.7) were still within an acceptable range. At T2, the fishy, stink, sour, and ammoniacal scores were 5.5, 6.0, 2.6, and 5.2, respectively, and the odor of GCC was not acceptable. These results were consistent with the TVB-N values.

3.3. FAAs composite analysis

FAAs are commonly considered important odor precursors that can produce acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, and other flavor compounds through transamination, dehydrogenation, decarboxylation, and reduction reactions.(Liu, Zhao, Zeng, & Xu, 2024) As shown in Table 2, 17 amino acids were analyzed, including 13 aliphatic, 2 aromatic, and 2 heterocyclic amino acids. During the storage, the total contents of FAAs increased from 616.56 to 1131.28 mg/100 g, which indicated that the proteins of GCCs hydrolyzed significantly (P < 0.05). Aliphatic amino acids were reported to be converted to oxidation compounds by enzymes, subsequently producing heterocyclic compounds such as thiophene, thiazole, and sulfides, which have a significant impact on the overall flavor. In addition, some aliphatic amino acids can be transformed into amines via deamination and decarboxylation reactions (Yi Shen et al., 2021). The aliphatic amino acid content increased from 558.79 to 918.42 mg/100 g during storage, providing sufficient substances for the formation of VOCs such as alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones. In addition, the aromatic amino acid content increased during the entire storage process; in particular, tryptophan increased from 29.13 to 207.89 mg/100 g, which can be further converted to tryptamine. Heterocyclic amino acids initially increased and then decreased. The changes in the content of heterocyclic amino acids might affect the formation of heterocyclic volatile compounds in GCCs during storage.

Table 2.

Changes of FAA contents in GCC during room temperature storage.

| Amino acids | Concentration (mg/100 g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |

| Aliphatic amino acid | 558.79 ± 0.95d | 603.83 ± 17.36c | 622.24 ± 5.55c | 692.98 ± 8.66b | 694.22 ± 12.35b | 918.42 ± 8.88a |

| Thr | 5.74 ± 0.19 bc | 8.36 ± 2.28 a | 6.84 ± 0.24 ab | 7.94 ± 0.13 a | 6.89 ± 0.19 ab | 4.25 ± 0.34 c |

| Val | 4.44 ± 0.09 e | 4.60 ± 0.04 e | 6.89 ± 0.19 d | 9.77 ± 0.51 c | 14.21 ± 0.67 b | 37.40 ± 0.88 a |

| Met | 1.44 ± 0.21 e | 1.85 ± 0.06 e | 3.36 ± 0.06 d | 7.85 ± 0.80 c | 11.75 ± 0.79 b | 21.12 ± 0.85 a |

| Leu | 4.87 ± 0.14 e | 4.10 ± 0.34 e | 8.83 ± 1.09 d | 14.71 ± 0.62 c | 22.69 ± 0.68 b | 61.61 ± 0.86 a |

| Lys | 31.00 ± 1.23 b | 29.65 ± 1.25 b | 36.20 ± 0.69 a | 25.26 ± 0.80 c | 12.06 ± 0.81 d | 9.15 ± 0.34 e |

| Ile | 7.20 ± 0.15 c | 12.38 ± 0.90 b | 16.62 ± 0.07 a | 15.46 ± 1.35 a | 5.37 ± 1.63 c | 2.67 ± 0.43 f |

| Glu | 12.27 ± 0.80 b | 11.53 ± 0.24 b | 19.66 ± 0.74 a | nd | nd | nd |

| Asn | nd | nd | nd | 55.85 ± 0.55 c | 86.05 ± 1.18 b | 107.38 ± 6.25 a |

| Gln | 113.15 ± 3.54 d | 133.77 ± 7.66 c | 127.04 ± 4.76 c | 148.45 ± 3.13 b | 154.32 ± 5.53 b | 215.45 ± 1.76 a |

| Arg | 11.39 ± 0.37 f | 80.22 ± 0.62 e | 106.77 ± 0.78 d | 138.14 ± 1.95 c | 173.52 ± 1.09 b | 267.74 ± 0.53 a |

| Ala | 19.01 ± 0.73 a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Tau | 261.72 ± 0.79 a | 245.08 ± 3.67 b | 210.68 ± 2.18 d | 238.10 ± 2.63 c | 207.35 ± 3.91 d | 191.65 ± 2.58 e |

| Gly | 86.56 ± 1.36 a | 72.29 ± 1.54 c | 79.37 ± 0.90 b | 31.45 ± 0.63 d | nd | nd |

| Aromatic amino acid | 31.52 ± 0.60f | 38.02 ± 1.28e | 44.91 ± 0.70d | 126.21 ± 1.09c | 155.32 ± 1.63b | 212.86 ± 0.91a |

| Tyr | 2.39 ± 0.26 e | 2.62 ± 0.14 e | 4.26 ± 0.03 d | 7.91 ± 0.15 a | 7.47 ± 0.17 b | 4.96 ± 0.15 c |

| Trp | 29.13 ± 0.72 f | 35.41 ± 1.17 e | 40.65 ± 0.72 d | 118.30 ± 1.23 c | 147.84 ± 1.71 b | 207.89 ± 0.88 a |

| Heterocyclic amino acid | 26.25 ± 0.49b | 6.15 ± 0.64e | 40.99 ± 0.11a | 24.57 ± 0.80c | 17.31 ± 0.56d | nd |

| Pro | 20.75 ± 0.52 c | nd | 37.27 ± 0.14 a | 22.34 ± 0.67 b | 15.46 ± 0.41 d | nd |

| His | 5.50 ± 0.21 a | 6.15 ± 0.64 a | 3.72 ± 0.24 b | 2.23 ± 0.16 c | 1.85 ± 0.15 c | nd |

| ∑FAA | 616.56 ± 0.94 f | 648.00 ± 19.11 e | 708.14 ± 6.06 d | 843.76 ± 8.47 c | 866.84 ± 13.16 b | 1131.28 ± 8.44 a |

Different letters represented significant difference (P < 0.05); nd means not detected.

3.4. FFA composite analysis

As important flavor precursors, FFAs can be oxidized and degraded into small molecules, such as aldehydes and ketones, which can then influence the odor profile of aquatic products.(Liu et al., 2024) The changes in the FFA composition of GCCs are shown in Table 3. A total of 29 FFAs were detected in GCCs during the entire storage process, including 14 saturated fatty acids (SFAs), 7 monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and 8 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). SFAs (accounting for 31.9–43.7 % of total fatty acids) and MUFAs (accounting for 34.8–47.7 % of total fatty acids) were the most abundant FFAs in GCCs during room temperature storage. The content of SFAs showed a general increasing trend (704.22 μg/g at T0 to 1103.01 μg/g at T4) with the extension of storage time (except for T5 at 563.97 μg/g). The increase in the SFA content may be related to the conversion of some unsaturated fatty acids into saturated fatty acids; a similar result was observed by Czerner, Agustinelli, Guccione, and Yeannes (2015). Palmitic acid (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0) were the most abundant SFAs in GCC, accounting for more than 86 % of the total SFA content. The trend of change in MUFAs was consistent with that of SFAs, including palmitoleic acid (C16:1), elaidic acid (C18:1n9t), and oleic acid (C18:1n9c), which accounted for more than 93 % of the MUFA content in all groups. PUFAs in aquatic products are easily oxidized because of their large number of conjugated double bonds (Fereidoon Shahidi, 2022). In this study, the PUFA content decreased significantly as the storage time progressed (decreasing from 569.63 μg/g at T0 to 358.83 μg/g at T5), possibly oxidizing and degrading into aldehydes, alcohols, ketones, and other small molecule compounds, imparting an undesirable odor to GCC.(Chu, Mei, & Xie, 2023) In addition, the total FFA content showed significant fluctuations throughout the storage process, which may have been induced by endogenous enzymes.(Xu et al., 2018).

Table 3.

Changes of FFA contents in GCC during room temperature storage.

| Fatty acids |

Concentration (mg/100 g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |

| C10:0 | 0.27 ± 0.11 ab | 0.34 ± 0.10 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 c | 0.17 ± 0.04 bc | 0.15 ± 0.02 bc |

| C12:0 | 15.16 ± 0.93 b | 22.42 ± 6.50 a | 4.8 ± 0.31 c | 6.29 ± 1.21 c | 6.25 ± 1.67 c | 6.87 ± 1.41 c |

| C13:0 | 0.07 ± 0.01 c | 0.14 ± 0.03 bc | 0.26 ± 0.10 a | 0.17 ± 0.02 abc | 0.23 ± 0.06 ab | 0.19 ± 0.04 ab |

| C14:0 | 40.86 ± 9.50 ab | 41.57 ± 9.90 ab | 33.60 ± 0.51 ab | 37.28 ± 4.68 ab | 43.12 ± 2.57 a | 28.81 ± 4.41 b |

| C15:0 | 5.90 ± 1.17 b | 5.68 ± 1.11 b | 6.79 ± 0.10 ab | 7.98 ± 1.11 a | 8.46 ± 0.67 a | 5.66 ± 0.82 b |

| C16:0 | 490.66 ± 12.83 d | 472.74 ± 54.30 d | 615.00 ± 14.62 c | 686.91 ± 6.61 b | 863.87 ± 14.77 a | 397.58 ± 37.88 e |

| C17:0 | 6.43 ± 0.87 ab | 5.36 ± 0.54 b | 6.44 ± 0.08 ab | 7.01 ± 0.50 a | 7.52 ± 0.30 a | 6.41 ± 0.67 ab |

| C18:0 | 132.07 ± 5.77 ab | 100.86 ± 7.70 b | 89.99 ± 56.13 b | 138.30 ± 32.15 ab | 161.19 ± 17.46 a | 110.76 ± 12.66 ab |

| C19:0 | 1.67 ± 0.01 a | 1.64 ± 0.05 ab | 1.64 ± 0.02 ab | 1.61 ± 0.02 ab | 1.64 ± 0.01 ab | 1.55 ± 0.10 b |

| C20:0 | 7.53 ± 2.18 a | 6.79 ± 0.95 ab | 7.40 ± 0.30 a | 7.58 ± 0.95 a | 8.24 ± 0.32 a | 5.03 ± 0.51 b |

| C21:0 | 0.33 ± 0.05 bc | 0.21 ± 0.02 d | 0.24 ± 0.09 cd | 0.44 ± 0.06 a | 0.43 ± 0.04 ab | 0.06 ± 0.01 e |

| C22:0 | 2.93 ± 0.38 a | 2.43 ± 1.05 ab | 0.92 ± 0.19 c | 1.63 ± 0.36 bc | 1.72 ± 0.05 bc | 0.90 ± 0.09 c |

| C23:0 | 0.30 ± 0.02 a | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.16 ± 0.02 b | 0.33 ± 0.07 a | 0.03 ± 0.00 d | nd |

| C24:0 | 0.06 ± 0.03 d | 0.07 ± 0.01 cd | 0.11 ± 0.00 bc | 0.20 ± 0.04 a | 0.14 ± 0.01 b | nd |

| ∑SFA | 704.22 ± 23.36cd | 660.52 ± 62.99d | 767.45 ± 49.71c | 895.84 ± 36.43b | 1103.01 ± 31.77a | 563.97 ± 55.65e |

| C14:1 | 0.19 ± 0.06 d | 0.51 ± 0.11 b | 0.30 ± 0.01 c | 1.18 ± 0.01 a | 1.20 ± 0.04 a | 1.16 ± 0.01 a |

| C16:1 | 91.94 ± 17.57 d | 105.35 ± 20.40 cd | 122.82 ± 2.07 bc | 136.25 ± 7.47 ab | 158.44 ± 12.90 a | 100.36 ± 16.92 cd |

| C17:1 | 5.60 ± 1.06 c | 5.81 ± 1.20 c | 7.08 ± 0.00 bc | 8.20 ± 1.25 ab | 8.92 ± 0.58 a | 6.02 ± 0.49 c |

| C18:1n9t | 470.29 ± 11.59 c | 407.75 ± 54.18 c | 497.80 ± 40.67 c | 675.81 ± 77.56 b | 850.74 ± 48.65 a | 612.98 ± 2.61 b |

| C18:1n9c | 77.99 ± 8.60 ab | 73.11 ± 6.00 bc | 65.75 ± 0.83 c | 72.17 ± 3.17 bc | 84.73 ± 4.13 a | 75.46 ± 5.98 abc |

| C20:1 | 30.22 ± 4.29 b | 26.88 ± 3.03 b | 29.41 ± 0.61 b | 30.30 ± 3.64 b | 32.97 ± 1.02 b | 41.91 ± 7.02 a |

| C22:1n9 | 5.06 ± 0.34 b | 5.06 ± 1.34 b | 4.42 ± 0.6 b | 9.19 ± 1.63 a | 3.83 ± 0.84 b | 3.94 ± 0.07 b |

| ∑MUFA | 681.29 ± 32.34d | 624.48 ± 72.26d | 727.58 ± 39.74cd | 933.10 ± 89.28b | 1140.84 ± 61.34a | 841.85 ± 32.88bc |

| C18:2n6c | 191.99 ± 27.11 a | 182.15 ± 33.23 a | 93.50 ± 2.45 b | 129.21 ± 20.26 b | 124.22 ± 13.65 b | 210.57 ± 11.62 a |

| C18:3n6 | 6.36 ± 0.68 bc | 8.36 ± 1.25 ab | 8.09 ± 0.97 ab | 10.36 ± 1.83 a | 10.90 ± 2.24 a | 4.98 ± 0.87 c |

| C18:3n3 | 212.67 ± 66.36 a | 45.74 ± 8.00 b | 43.10 ± 9.06 b | 62.11 ± 0.77 b | 53.20 ± 1.98 b | 43.83 ± 7.44 b |

| C20:3n6 | 25.75 ± 1.03 bc | 25.79 ± 1.84 bc | 26.54 ± 0.01 b | 28.03 ± 3.13 b | 30.23 ± 3.11 a | 17.48 ± 1.41 c |

| C20:3n3 | 2.47 ± 0.84 b | 2.36 ± 0.05 b | 2.87 ± 0.32 ab | 2.40 ± 0.04 b | 3.36 ± 0.05 a | 2.69 ± 0.07 ab |

| C20:4n6 | 84.61 ± 19.15 a | 97.98 ± 11.33 a | 57.7 ± 5.82 b | 57.17 ± 11.29 b | 52.32 ± 2.45 b | 46.41 ± 5.62 b |

| C20:5n3 (EPA) | 15.35 ± 0.14 ab | 13.15 ± 1.10 ab | 12.19 ± 0.43 b | 14.63 ± 1.43 ab | 14.59 ± 0.31 ab | 16.64 ± 4.45 a |

| C22:6n3 (DHA) | 30.42 ± 0.75 a | 32.06 ± 5.92 a | 16.94 ± 6.57 b | 14.2 ± 3.28 b | 11.74 ± 1.87 b | 16.23 ± 0.24 b |

| ∑PUFA | 569.63 ± 104.45a | 407.60 ± 28.60b | 260.93 ± 9.08d | 318.12 ± 35.35bcd | 312.44 ± 17.41cd | 358.83 ± 10.38bc |

| Total fatty acids | 1955.14 ± 133.18bc | 1692.59 ± 151.73d | 1755.95 ± 21.90cd | 2147.06 ± 153.08b | 2556.28 ± 81.98a | 1764.65 ± 86.89cd |

“nd” represented not detected.

Different letters represented significant difference (P < 0.05); nd means not detected.

3.5. Identification of VOCs

SAFE was used to extract VOCs and identify the volatile compounds in the samples. The obtained VOCs were further analyzed using AEDA combined with GC-O-MS. To confirm the VOCs with different odors, the line retention index (RI) of the compounds was determined using two chromatographic columns with different polarities (DB-WAX and HP-5 MS UI).

As shown in Table 3, a total of 40 VOCs with FD ≥ 2 were identified from the GCCs in different freshness degrees based on the AEDA results. Generally, more VOCs were detected as the degree of freshness decreased. Eight compounds were detected at T0, 12–14 compounds at T1, T2, T3, and T4; and 18 at T5. Besides two unknown compounds, the remaining 38 volatile compounds were classified into eight chemical classes, including two aldehydes, six alcohols, five ketones, seven esters, two acids, six nitrogen/sulfur-containing compounds, six aromatic compounds, and four hydrocarbons. According to the TVB-N values, the samples at T0 and T1 were relatively fresh, and the main grassy and metallic odors of T0 and T1 were generated by heptadecyl acetate (FD = 4 at T1) and naphthalene (FD = 8 and 64 at T0 and T1, respectively).(Wang et al., 2022) Nevertheless, the samples at T2, T3, T4, and T5 were corrupted, and the odors of these groups were mainly sour, stink, fishy, and ammoniacal. Among these samples, the main stink odor was generated by cyclohexane isothiocyanate (FD values of 32, 64, 32, and 128 at T2, T3, T4, and T5, respectively) and phenol (FD values of 2 and 8 at T4 and T5, respectively). The fishy odor was mainly produced by methyl diethyldithiocarbamate (FD value of 8 at T5) and N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine (FD values of 8, 64, 64, and 2 at T2, T3, T4, and T5, respectively). Ethyl 4-pyridylacetate significantly contributed to the ammoniacal odor, with FD values of 8 and 16 at T4 and T5, respectively. In addition, 1,3,5-trioxane,(Laohakunjit, 2007) benzophenone, dibutyldithiocarbamic acid methyl ester, succinimide, eugenol, and 2-methyl-undecane also played important roles in the odors of the T2, T3, T4, and T5 groups. Furthermore, the FD values of cyclohexane isothiocyanato, methyl diethyldithiocarbamate, and N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine increased with time, which may be closely correlated with the increased fishy, stink, and ammoniacal odors of the samples.

3.6. Concentrations of volatile compounds and OAV analysis

Based on the results of the AEDA combined with volatile amine determination, 48 VOCs were quantitated in this study. Among these compounds, the concentrations and OAVs of TMA and ammonia were higher than those of all other compounds. The initial content of TMA was 21,884.69 μg/L, which was maintained within approximately 25,028.53 μg/L. However, the concentration increased to 51,042.79 μg/L at T3 and then sharply rose to 136,830.54 μg/L at T5. The increase in TMA content might be ascribed to the strengthened activity of spoilage microorganisms, which were responsible for the enhanced fishy odor (Shuai Zhuang, Gao, Tan, Hong, & Luo, 2023). As the storage time increased, the ammonia content increased in the tissue after death, which was attributed to an increase in protein degradation (Shuai Zhuang, Zhang, & Luo, 2020). The concentration of ammonia in the fresh GCC was 47,511.68 μg/L, which initially increased to 71,910.36 μg/L at T1 and 91,322.38 μg/L at T2, then further to 123,162.40, 205,013.51, and 427,683.36 μg/L at T3, T4, and T5, respectively. Consistent with this observation, the OAVs of ammonia increased during the entire storage process, and the increase in ammonia content directly strengthened the ammoniacal smell of GCC.

The concentrations of putrescine, cadaverine, and histamine were significantly higher than other VOCs, followed by spermidine, while the concentrations of tryptamine, phenylethylamine, tyramine, and agmatine were lower than 11,000 μg/L during the whole storage process (Table 4). Among these, histamine and tyramine exhibited the strongest toxic effects (Jinjin Ma, Zhang, & Yan, 2023). According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the tolerable levels of histamine and tyramine for human health are 50 and 600 mg/kg,(EFAA, 2011) respectively. The concentrations of histamine (19,779.46 μg/L) and tyramine (4564.57 μg/L), corroborated by the TVB-N values, were within the limits until T2. Moreover, the concentrations of putrescine (13,329.62 μg/L increased to 527,253.48 μg/L), cadaverine (nd increased to 621,058.19 μg/L), histamine (nd increased to 618,123.82 μg/L), and spermidine (7011.01 μg/L increased to 103,314.24 μg/L) all increased across the storage time. The increased trend of these BAs might probably because that the increased pH affected the rates of biochemical reactions. At high pH, microorganisms and endogenous enzymes could react with FAAs and other low molecular weight compounds, accelerating the formation of BAs. (Wangli Dai et al., 2021) Conversely, the concentrations of tyramine and agmatine generally decreased during storage. No BAs had OAV ≥ 1 at T0 and T1, and only the OAV of putrescine (1.31) and cadaverine (3.67) were greater than 1 at T2, which could explain the weak ammoniacal and fishy scores of the T0, T1, and T2 groups. However, the OAVs for putrescine, cadaverine, and histamine were > 1 from T3 to T5, particularly for cadaverine and histamine. Additionally, the OAVs of tryptamine were 1.01 and 1.10 at T4 and T5, respectively. According to the results, the increased BA content played an important role in strengthening the fishy and ammoniacal odors of GCC. (See Table 5.)

Table 4.

Odor contribution of VOCs in GCC under different freshness degrees.

| No. | Compounds | CAS | RI |

FD factor a |

Odor description c | Identification d | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB-WAX | HP-5MS UIb | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |||||

| Aldehydes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1,3,5-trioxane | 110–88-3 | 1154 | 648 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 32 | chloroform-like | MS/RI/O/S | ||

| 2 | (E)-2-hexenal | 6728-26-3 | 1283 | 862 | 2 | green apple, bitter almond | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||

| 1 | acetoin | 513–86-0 | 1268 | 730 | 2 | fishy | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 2 | 3-hexen-1-ol | 544–12-7 | 1363 | 902 | 2 | paint, sour | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 3 | α-terpineol | 98–55-5 | 1683 | 1190 | 2 | clove | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | 3-(methylthio)-1-propanol | 505–10-2 | 1702 | 995 | 2 | donkey-hide gelatin, fishy | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 5 | 3-methoxy-1-butanol | 2517-43-3 | 1805 | 830 | 8 | ink | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 6 | phenylethyl alcohol | 60–12-8 | 1888 | 1116 | 2 | rose-like, fruity | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Ketones | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 4-heptanone | 123–19-3 | 1223 | 865 | 8 | coffee | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 2 | 3-undecanone | 2216-87-7 | 1557 | 1265 | 2 | leathery, scorching, stink | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 3 | acetophenone | 98–86-2 | 1626 | 1068 | 4 | sunflower seed | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxy-4-methylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one | 10,396–80-2 | 2086 | 1472 | 2 | 2 | musty, humus | MS/RI/O/S | ||||

| 5 | benzophenone | 119–61-9 | 2442 | 1625 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 64 | dusty | MS/RI/O/S | ||

| Esters | ||||||||||||

| 1 | carbamic acid, methyl ester | 598–55-0 | 1616 | 882 | 2 | green, grassy | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 2 | triethyl phosphate | 78–40-0 | 1649 | / | 2 | soy sauce | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 3 | methyl diethyldithiocarbamate | 686–07-7 | 1983 | 1379 | 8 | beany, oat, fishy | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | dibutyldithiocarbamic acid methyl ester | 38,351–44-9 | 2257 | 1430 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 4 | rice, fishy | MS/RI/O | ||

| 5 | ethyl 4-pyridylacetate | 54,401–85-3 | 2338 | / | 8 | 16 | ammoniacal | MS/O/S | ||||

| 6 | 1,3,5-tri-2-propenyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione | 1025-15-6 | 2367 | 1670 | 2 | coconut | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 7 | heptadecyl acetate | 822–20-8 | 2498 | / | 4 | fruity, grassy, metallic | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Acids | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 4-methyl-pentanoic acid | 646–07-1 | 1859 | 993 | 2 | sweet, sour | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 2 | 2,2-dimethyl-butanoic acid | 595–37-9 | 2043 | 1877 | 2 | halad, fatty | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Nitrogen/Sulfur-containing compounds | ||||||||||||

| 1 | N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine | 121–69-7 | 1526 | 1093 | 8 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 2 | beany, steamed rice, fishy | MS/RI/O/S | |

| 2 | cyclohexane isothiocyanato | 1122-82-3 | 1648 | 1232 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 128 | soy sauce, leathery, stink | MS/RI/O/S |

| 3 | 3-methyl-butanamide | 541–46-8 | 1805 | / | 4 | woody, herbal, grassy | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | 4-tert-butyl-1(1-thioxo-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-benzene | 72,194–24-2 | 2076 | / | 8 | musty, humus | MS/O/S | |||||

| 5 | succinimide | 123–56-8 | 2431 | / | 16 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 64 | peppermint, grassy | MS/RI/O/S | |

| 6 | dodecanamide | 1120-16-7 | 2739 | / | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | paint, yuzu flavor, grassy | MS/RI/O/S | ||

| Aromatic compounds | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1,2,3,4-tetramethyl-benzene | 488–23-3 | 1479 | 1150 | 8 | paint, phenolic | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 2 | naphthalene | 91–20-3 | 1710 | 1179 | 8 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 2 | bitter almond, camphor, grassy | MS/RI/O/S |

| 3 | butylated hydroxytoluene | 128–37-0 | 1897 | 1523 | 2 | stink | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | phenol | 108–95-2 | 1981 | 990 | 2 | 8 | phenolic, plastic, rubber, smoky, stink | MS/RI/O/S | ||||

| 5 | eugenol | 97–53-0 | 2140 | 1358 | 16 | 4 | 2 | woody, pine nut | MS/RI/O/S | |||

| 6 | 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol | 96–76-4 | 2287 | 1513 | 8 | woody, green, sweet | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Hydrocarbons | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 2-methyl-undecane | 7045-71-8 | 1196 | 1166 | 4 | 16 | 8 | beany, fishy | MS/RI/O/S | |||

| 2 | styrene | 100–42-5 | 1244 | 886 | 2 | 2 | 2 | paint | MS/RI/O/S | |||

| 3 | caryophyllene | 87–44-5 | 1584 | 1418 | 2 | paint | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| 4 | heptadecane | 629–78-7 | 1701 | 1206 | 8 | donkey-hide gelatin | MS/RI/O/S | |||||

| Unknowns | ||||||||||||

| 1 | unknown-1 | / | 1796 | / | 2 | woody | O | |||||

| 2 | unknown-2 | / | 2127 | / | 2 | wine | O | |||||

FD factor was determined by AEDA on a DB-WAX capillary column.

“/” represented the compounds were not detected.

Odor quality was detected by GC-O.

MS, identified by NIST 20 mass spectral database; RI, agreed with the retention indices published in literature; O, agreed with the odor characteristics published in literature; S, agreed with the retention time of standards.

Table 5.

Concentrations and OAVs of volatile compounds in GCC during room temperature storage.

| Compounds |

Threshold (μg/L) a | Concentration (μg/L) |

OAV |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | ||

| Aldehydes | 35.37 ± 1.59e | 169.19 ± 30.46c | 134.51 ± 8.79cd | 117.7 ± 5.28d | 227.54 ± 43.96b | 1029.05 ± 3.01a | |||||||

| 1,3,5-trioxane | 5080 | 35.37 ± 1.59d | 169.19 ± 30.46b | 134.51 ± 8.79bc | 117.7 ± 5.28c | 227.54 ± 43.96a | 117.22 ± 4.83c | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| (E)-2-hexenal | 10 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 911.83 ± 3.51a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 91.18 |

| Alcohols | 22.41 ± 1.03d | 175.45 ± 9.56c | 309.53 ± 8.91b | 149.87 ± 5.62c | 809.29 ± 65.77a | 124.45 ± 6.78c | |||||||

| acetoin | 14 | 22.41 ± 1.03d | 23.82 ± 1.4d | 304.81 ± 8.53b | 142.95 ± 4.81c | 793.18 ± 67.1a | 31.36 ± 4.69d | 1.60 | 1.70 | 21.77 | 10.21 | 56.66 | 2.24 |

| 3-hexen-1-ol | 70 | nd | nd | nd | 4.80 ± 0.84a | 5.40 ± 0.48a | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | < 1 | nd |

| α-terpineol | 4.6 | nd | 6.41 ± 0.99b | 4.72 ± 0.41bc | 2.12 ± 0.20c | 7.61 ± 2.79b | 35.67 ± 1.83a | nd | 1.39 | 1.03 | < 1 | 1.65 | 7.75 |

| 3-(methylthio)-1-propanol | 5 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 7.45 ± 0.65a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1.49 |

| 3-methoxy-1-butanol | 12 | nd | 145.21 ± 7.41a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 12.10 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| phenylethyl alcohol | 45 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.10 ± 0.16b | 49.96 ± 0.66a | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | 1.11 |

| Ketones | 13.89 ± 0.63d | 33.65 ± 4.03b | 49.78 ± 0.82a | 9.99 ± 0.29de | 8.96 ± 0.60e | 25.91 ± 3.10c | |||||||

| 4-heptanone | 8.2 | nd | nd | 1.04 ± 0.34a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | nd | nd |

| 3-undecanone | 8.3 | 5.07 ± 0.17a | nd | 1.30 ± 0.04b | 0.84 ± 0.26b | nd | 5.05 ± 1.24a | < 1 | nd | < 1 | < 1 | nd | < 1 |

| acetophenone | 36 | 5.45 ± 0.26d | 11.26 ± 0.20b | 18.54 ± 0.38a | 6.04 ± 0.36d | 7.10 ± 0.52c | 4.06 ± 3.51d | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxy-4-methylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one | 8600 | nd | 17.57 ± 3.74b | 22.17 ± 0.71a | nd | nd | 11.97 ± 3.86c | nd | < 1 | < 1 | nd | nd | < 1 |

| benzophenone | 1400 | 3.36 ± 0.24c | 4.82 ± 0.42b | 6.73 ± 0.34a | 3.11 ± 0.18c | 1.86 ± 0.17d | 2.80 ± 0.31c | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Esters | 258.86 ± 4.64c | 449.71 ± 9.26a | 285.03 ± 14.39b | 237.75 ± 9.45d | 161.15 ± 6.13f | 192.06 ± 2.80e | |||||||

| carbamic acid, methyl ester | > 129 | 8.15 ± 0.46b | 12.53 ± 0.27a | 6.59 ± 0.89c | 7.22 ± 0.37c | 1.21 ± 0.11e | 3.94 ± 0.07d | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| triethyl phosphate | 6000 | 24.02 ± 3.09a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| methyl diethyldithiocarbamate | 350.6 | 124.22 ± 3.37d | 161.41 ± 9.23b | 177.53 ± 8.82a | 140.35 ± 3.81c | 124.51 ± 5.82d | 35.18 ± 1.30e | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| dibutyldithiocarbamic acid methyl ester | 3200 | 4.43 ± 0.46c | 5.60 ± 0.41b | 7.15 ± 0.67a | 6.51 ± 0.85ab | 3.13 ± 0.61d | nd | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd |

| ethyl 4-pyridylacetate | 4.52 | nd | nd | nd | 2.30 ± 0.37c | 4.74 ± 0.10b | 15.52 ± 1.66a | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | 1.05 | 3.43 |

| 1,3,5-tri-2-propenyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione | 1750 | 68.8 ± 3.21b | 117.06 ± 1.27a | 72.36 ± 8.44b | 57.23 ± 0.53c | 22.92 ± 0.92d | 115.99 ± 1.27a | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| heptadecyl acetate | 1560 | 29.25 ± 2.16b | 153.11 ± 2.93a | 21.40 ± 6.96b | 24.13 ± 4.97b | 4.64 ± 0.31c | 21.41 ± 5.02b | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Acids | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.60 ± 0.22b | 29.42 ± 3.90a | |||||||

| 4-methyl-pentanoic acid | 810 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 29.42 ± 3.90a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 |

| 2,2-dimethyl-butanoic acid | 1603 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.6 ± 0.22a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd |

| Nitrogen/Sulfur-containing compounds | 69.01 ± 2.80c | 71.07 ± 2.11c | 128.26 ± 5.48a | 59.22 ± 2.53d | 70.50 ± 1.10c | 101.50 ± 8.97b | |||||||

| N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine | 5 | 12.66 ± 1.26e | 44.06 ± 0.91bc | 42.32 ± 0.44c | 33.23 ± 1.54d | 50.62 ± 0.64b | 68.53 ± 8.24a | 2.53 | 8.81 | 8.46 | 6.65 | 10.12 | 13.71 |

| cyclohexane isothiocyanato | 5.67 | 4.53 ± 0.61b | 4.76 ± 0.51b | 7.49 ± 1.30a | 3.32 ± 0.73b | 9.49 ± 1.96a | 2.82 ± 1.00b | < 1 | < 1 | 1.32 | < 1 | 1.67 | < 1 |

| 3-methyl-butanamide | 5200 | 40.11 ± 2.08b | nd | 62.91 ± 5.90a | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | < 1 | nd | nd | nd |

| 4-tert-butyl-1(1-thioxo-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-benzene | 6970 | nd | nd | nd | 10.81 ± 0.02a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | nd |

| succinimide | 5130 | 3.62 ± 0.39b | 5.87 ± 0.44a | 6.68 ± 0.70a | 4.03 ± 0.06b | nd | 1.76 ± 0.22c | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd | < 1 |

| dodecanamide | 2200 | 8.09 ± 0.28c | 16.38 ± 0.85b | 8.85 ± 1.93c | 7.84 ± 0.68c | 10.39 ± 0.50c | 28.39 ± 3.82a | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Aromatic compounds | 1196.34 ± 37.08c | 2110.41 ± 171.79b | 2885.52 ± 143.13a | 2177.96 ± 82.75b | 744.09 ± 18.00d | 1135.43 ± 46.11c | |||||||

| 1,2,3,4-tetramethyl-benzene | 61 | nd | nd | nd | 53.07 ± 1.43a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | nd |

| naphthalene | 1 | 70.88 ± 3.18d | 93.21 ± 2.82c | 236.17 ± 1.48a | 72.21 ± 1.21d | 111.34 ± 5.46b | 44.68 ± 0.24e | 70.88 | 93.21 | 236.17 | 72.21 | 111.34 | 44.68 |

| butylated hydroxytoluene | 1 | 13.18 ± 0.11d | 12.92 ± 2.13d | 24.43 ± 1.67c | 16.05 ± 3.14d | 154.59 ± 3.91a | 40.25 ± 0.85b | 13.18 | 12.92 | 24.43 | 16.05 | 154.59 | 40.25 |

| phenol | 30 | 27.88 ± 5.08b | 44.45 ± 2.22a | 51.54 ± 2.38a | 27.05 ± 1.49b | 8.77 ± 0.48c | 50.55 ± 8.98a | < 1 | 1.48 | 1.72 | < 1 | < 1 | 1.69 |

| eugenol | 0.71 | 894.36 ± 30.13c | 1671.04 ± 148.60b | 2378.86 ± 140.38a | 1846.98 ± 78.12b | 192.24 ± 8.77d | 894.06 ± 40.86c | 1259.66 | 2353.58 | 3350.51 | 2601.38 | 270.76 | 1259.24 |

| 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol | 500 | 190.05 ± 2.25b | 288.8 ± 17.75a | 194.51 ± 7.93b | 162.61 ± 2.63c | 277.16 ± 7.98a | 105.89 ± 3.13d | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Hydrocarbons | 381.77 ± 14.87e | 575.03 ± 36.64e | 249.77 ± 4.79d | 134.55 ± 7.08c | 399.3 ± 13.07b | 249.31 ± 16.42a | |||||||

| 2-methyl-undecane | 10,000 | nd | nd | 16.30 ± 1.64a | 8.16 ± 0.18b | 5.16 ± 1.17c | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd |

| styrene | 3.6 | 339.09 ± 8.44b | 510.91 ± 34.22a | 172.29 ± 5.93d | 126.4 ± 6.91e | 329.35 ± 8.19b | 249.31 ± 16.42c | 94.19 | 141.92 | 47.86 | 35.11 | 91.49 | 69.25 |

| caryophyllene | 64 | nd | 64.13 ± 3.12a | 61.18 ± 0.72a | nd | 64.79 ± 7.85a | nd | nd | 1.00 | < 1 | nd | 1.01 | nd |

| heptadecane | 12,000 | 42.68 ± 6.47a | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Volatile amines | 117,340.92 ± 1118.58b | 154,051.34 ± 3654.96bc | 263,745.30 ± 9756.02bc | 822,560.33 ± 14,082.74c | 1,534,852.99 ± 38,776.66a | 2,435,894.47 ± 107,252.44a | |||||||

| tryptamine | 10,000 | 7873.38 ± 644.37b | 6910.16 ± 195.84bc | 4510.40 ± 75.58d | 5940.37 ± 325.75cd | 10,091.36 ± 524.45a | 10,962.83 ± 1946.18a | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | 1.01 | 1.10 |

| phenylethylamine | 25,000 | 5824.75 ± 342.94ab | 4828.85 ± 421.17c | 6532.57 ± 609.45c | 6264.85 ± 238.40a | 5375.75 ± 313.21bc | nd | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd |

| putrescine | 20,000 | 13,329.62 ± 291.57d | 18,558.11 ± 995.67d | 26,181.88 ± 1625.84d | 113,624.27 ± 2959.05c | 224,206.38 ± 10,731.11b | 527,253.48 ± 32,977.04a | < 1 | < 1 | 1.31 | 5.68 | 11.21 | 26.36 |

| cadaverine | 20,000 | nd | 11,609.82 ± 440.38e | 73,355.02 ± 4971.69d | 186,577.42 ± 6292.32c | 333,939.79 ± 11,533.29b | 621,058.19 ± 41,022.5a | nd | < 1 | 3.67 | 9.33 | 16.70 | 31.05 |

| histamine | 70,000 | nd | nd | 19,779.46 ± 975.82d | 320,239.07 ± 49.85c | 650,450.12 ± 22,609.21a | 618,123.82 ± 18,105.26b | nd | nd | < 1 | 4.57 | 9.29 | 8.83 |

| tyramine | 10,000 | 4237.72 ± 97.62b | 5414.20 ± 637.89a | 4564.57 ± 204.31b | nd | nd | nd | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd | nd | nd |

| spermidine | 129,000 | 7011.01 ± 674.23c | 4885.03 ± 548.97c | 7458.59 ± 995.19c | 9346.2 ± 11.48c | 33,299.37 ± 2285.11b | 103,314.24 ± 8651.01a | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| agmatine | 24,000 | 9668.06 ± 1401.6a | 4906.27 ± 408.03c | 4843.76 ± 236.34c | 6362.96 ± 477.19b | 4811.47 ± 215.14c | nd | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | nd |

| TMA | 600 | 21,884.69 ± 1547d | 25,028.53 ± 364.73d | 25,196.67 ± 4639.7d | 51,042.79 ± 2675.82c | 67,665.24 ± 2328.76b | 127,498.55 ± 9331.99a | 36.47 | 41.71 | 41.99 | 85.07 | 112.78 | 228.05 |

| ammonia | 1250 | 47,511.68 ± 2142.78e | 71,910.36 ± 3462.40de | 91,322.38 ± 2698.33cd | 123,162.4 ± 9680.62c | 205,013.51 ± 6540.42b | 427,683.36 ± 38,174.32a | 38.01 | 57.53 | 73.06 | 98.53 | 164.01 | 342.15 |

The thresholds of compounds were referenced to the literature or determined.

Different letters represented significant difference (P < 0.05).

Aldehydes and alcohols play a significant role in the odor profiles of aquatic products because of their low thresholds.(Lei et al., 2023) In this study, the concentrations of aldehydes and alcohols were high throughout the storage period. Remarkably, the content and OAV (always higher than 1) of acetoin were relatively high, which may contribute to the fishy odor of GCC.(Zhao, Fan, & Xu, 2021) The concentrations of α-terpineol were low, but its OAVs were always higher than 1, with the exception of T0 and T3, due to its low threshold. In addition, (E)-2-hexenal had an OAV of 91.18 at T5, reflecting the green apple and bitter almond odor. The concentration of 1,3,5-trioxane was high in all groups, but its threshold was high; therefore, its contribution to GCC was limited. In addition, 3-(methylthio)-1-propanol, most likely converted from methionine,(Liu et al., 2024) was detected at T5 (7.45 μg/L) with an OAV of 1.49. Phenylethyl alcohol was detected in T4 and T5, and the OAV was 1.11 at T5, producing a rose-like, fruity odor for the GCC in the late period of deterioration. Based on the results of the concentrations and OAVs, the aldehydes and alcohols most likely impart a fishy odor to the GCC, especially after spoilage, as is widely reported.(Liu et al., 2024).

Aromatic compounds were regarded as the third-most important VOCs in this study because of their high concentrations and low thresholds. Butylated hydroxytoluene and phenol mainly contributed to the stink odor of GCC, particularly during the later period of deterioration. Phenol has been detected in stinky tofu brine and identified as a key volatile compound responsible for the stink odor of stinky tofu by Tang et al.(Hui Tang et al., 2022) Naphthalene (bitter almond, camphor, grassy, OAV > 40) and eugenol (woody, pine nut, OAV > 270, which reached 3350.51 at T2) were also significant contributors to the odor profiles of GCC. Additionally, the concentrations of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (woody, green, and sweet) were higher than 100 μg/L in all groups (even reaching 288.80 μg/L at T1), and also had a coordination effect on the overall odor.

As for nitrogen/sulfur-containing compounds, the concentrations of N,N-dimethyl- benzenamine increased in almost all groups, with the exception of T3 (33.23 μg/L), from 12.66 μg/L at T0 to 68.53 μg/L at T5. Furthermore, its OAVs were greater than 1 in all groups, ranging from 2.53 to 13.71 and contributed beany, steamed rice, and fishy odors to the overall odor profile of GCC. Additionally, the contents of cyclohexane isothiocyanato were low (2.82 to 9.49 μg/L), but the OAVs were higher than 0.5, particularly at T2 (1.32) and T4 (1.67). It mainly contributes a soy sauce, leathery, and stink-like odor to the GCC. These results might have resulted in a decline in sensory scores, which agrees with the results obtained by the sensory analysis.

Unsaturated hydrocarbons like styrene (OAVs ranged from 35.11 to 141.92) and caryophyllene (OAV of 0.86, 0.79, and 1.01 at T1, T2, and T4, respectively) mainly contributed a paint odor to the GCC.(Septiana et al., 2020).

3.7. Aroma recombination and omission experiments

In order to validate the above experimental results, recombination tests were performed with the 19 compounds with OAV ≥ 1 mentioned above. The structural formulas of the 19 VOCs are shown in Fig. S1. To reflect the changes in the odor profile of GCC during room temperature storage, we selected T0, T2, and T5 for aroma recombination experiments. The results shown in Fig. 3 demonstrated that Re-T0, Re-T2, and Re-T5 were very similar to the aroma profiles of the T0, T2, and T5 groups (P < 0.05), respectively, proving that the recombined models reflected the odor profiles of the original systems. For Re-T0, the odor attribute scores of sour and ammoniacal were lower than those of T0, whereas the scores for grassy, mushroom, and fishy attributes were higher than those of T0. In contrast, the odor profile of Re-T2 was extremely closed to that of the original model. For Re-T5, the odor attribute scores of stink, ammoniacal, and sour were higher than those of T5, whereas the score of the metallic attribute was lower than that of T5. The difference between the original system and recombined model probably because the interaction between the volatile components and non-volatile components affected the volatilization of odor. (Fangxue Chen et al., 2023).

Fig. 3.

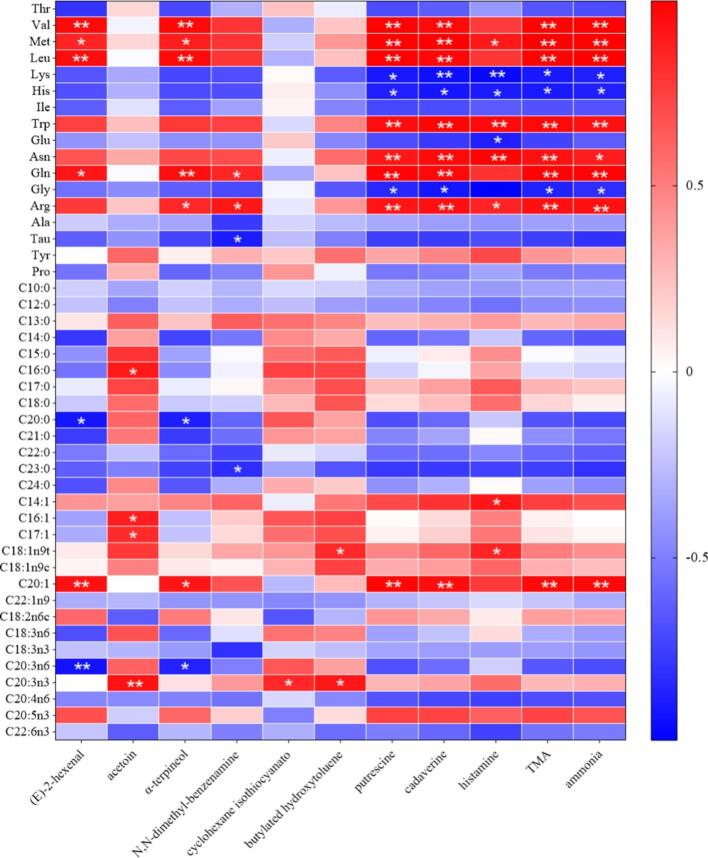

Correlation analysis between the key odor compounds and odor precursor compounds. Red indicated positive relation, and blue revealed negative relation. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Omission tests can further verify the contributions of individual VOC to the odor profile. The results of omission tests are shown in Table 6. Five, eight, and thirteen odorants dramatically influenced the odor characteristics of the T0, T2, and T5 recombination models, respectively. At T0, styrene, eugenol, and TMA contributed significantly to the overall odor profile (P < 0.01), which was correctly judged by eight of ten panelists with the absence. Naphthalene and ammonia also played important roles in the odor profile at T0 (P < 0.05). As the degree of deterioration increased, the number of VOCs that influenced the odor profile of the GCC significantly increased. In the Re-T2 model, naphthalene and eugenol contributed the most to the overall odor profile of GCC (P < 0.001), with TMA and ammonia also dramatically influencing the odor profile (P < 0.01). Additionally, styrene, acetoin, (E)-2-hexenal, and N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine were also identified as important odorants in the overall odor profiles, and seven of the ten panelists correctly judged the significant difference in the absence of these odorants. For the Re-T5 model, TMA and ammonia were identified as the most important odorants in the overall odor profile, which were correctly judged by all the panelists in the absence. Styrene, (E)-2-hexenal, N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine, cyclohexane isothiocyanato, butylated hydroxytoluene, eugenol, putrescine, and cadaverine also contributed significantly to the overall odor profile (P < 0.01). Additionally, α-terpineol, phenylethyl alcohol, naphthalene, and histamine also played important roles in the overall odor profile (P < 0.05). These results were in accordance with the changes in sensory scores. It was interesting that not all the VOC with OAV ≥ 1 showed a significant difference, such as 3-(methylthio)-1-propanol, ethyl 4-pyridylacetate, phenol, and tryptamine. Therefore, it is not accurate that the higher the OAV, the higher significance level caused in omission test. This may probably because of the synergistic, antagonistic or masking effects between different VOCs. (Xiaojing Zhang, Xia, Jiang, Liu, & Xu, 2022).

Table 6.

| No. | Compounds | Omission test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T2 | T5 | ||

| 1 | (E)-2-hexenal | nd | 7* | 8** |

| 2 | acetoin | 5 | 7* | 6 |

| 3 | α-terpineol | nd | 6 | 7* |

| 4 | 3-(methylthio)-1-propanol | nd | nd | 6 |

| 5 | phenylethyl alcohol | nd | nd | 7* |

| 6 | ethyl 4-pyridylacetate | nd | nd | 6 |

| 7 | N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine | 3 | 7* | 8** |

| 8 | cyclohexane, isothiocyanato | 6 | 6 | 8** |

| 9 | naphthalene | 7* | 9*** | 7* |

| 10 | butylated hydroxytoluene | 5 | 6 | 8** |

| 11 | phenol | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 12 | eugenol | 8** | 9*** | 8** |

| 13 | styrene | 8** | 7* | 8** |

| 14 | tryptamine | nd | nd | 5 |

| 15 | putrescine | nd | 5 | 8** |

| 16 | cadaverine | nd | 6 | 8** |

| 17 | histamine | nd | nd | 7* |

| 18 | TMA | 8** | 8** | 10*** |

| 19 | ammonia | 7* | 8** | 10*** |

Number of correct judgments from 10 assessors evaluating the aroma difference by means of a triangle test.

Significance: ***, very highly significant (P ≤ 0.001); **, highly significant (P ≤ 0.01); *, significant (P ≤ 0.05).

3.8. Correlation analysis between the key OOCs and odor precursor compounds

To observe the relationship between key OOCs (Fig. S2) and odor precursor compounds, a correlation heat map was constructed. As shown in Fig. 3, OOCs contained putrescine, cadaverine, TMA, and ammonia were significantly negatively correlated with Lys, His, and Gly (P < 0.05), indicating that Lys, His, and Gly may be odor precursor compounds of putrescine, cadaverine, TMA, and ammonia. However, a prominent positive correlation was observed between OOCs (putrescine, cadaverine, TMA, and ammonia) and amino acids (Val, Met, Leu, Asn, Gln, and Arg (P < 0.01), suggesting that these amino acids were closely associated with the formation of putrescine, cadaverine, TMA, and ammonia. Additionally, histamine levels negatively correlated with Lys, His, Glu, and Gly (P < 0.05), suggesting that histamine may be derived from these amino acids (Maria Carmela Ferrante, 2023). Moreover, Val, Met, Leu, and Gln showed significant correlation with (E)-2-hexenal, α-terpineol, putrescine, cadaverine, TMA, and ammonia (P < 0.01), indicating that the production of these OOCs might be related to Val, Met, Leu, and Gln. In addition, Tau, Gln, and Arg appeared to be involved in the production of N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine. These results suggested that amino acid degradation may play an important role in the odor deterioration of GCC, resulting in OOCs (Shuai Zhuang et al., 2021).

In addition to amino acid degradation, fatty acid degradation also affected the odor of GCC during room temperature storage. It has been reported that phospholipids and triglycerides in fats are decomposed into fatty acids by heat; unsaturated fatty acids are further decomposed into alkyl radicals and hydroxyl peroxides under the action of free radicals and reactive oxygen species, which then react with each other to generate more stable volatile flavor compounds, including aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones (Lujie Chenga et al., 2023). In this study, (E)-2-hexenal and α-terpineol showed a strong negative correlation with arachidic acid (C20:0) and arachidonic acid (C20:3n6) (P < 0.05), suggesting that (E)-2-hexenal and α-terpineol might be converted from arachidic acid (C20:0) and arachidonic acid (C20:3n6). However, eicosenoic acid (C20:1) positively correlated with OOCs (P < 0.01), suggesting that eicosenoic acid (C20:1) may be closely related to their formation. In addition, acetoin strongly correlated with palmitic acid (C16:1), palmitoleic acid, heptadecenoic acid (C17:1), and eicosatrienoic acid (C20:3n3) (P < 0.05). In addition, palmitic acid (C16:0), trichosoic acid (C23:0), myristoleic acid (C14:1), and elaidic acid (C18:1n9t) are closely related to the formation of some OOCs (P < 0.05).

It can be inferred that the degradation of amino acids and fatty acids played an important role in the formation of odorous substances that contributed to the unpleasant odor of GCC during room temperature storage, consistent with the results of previous studies (Cai et al., 2021). Therefore, it is important to inhibit these reactions during storage of grass carp and other freshwater fish.

4. Conclusion

In this study, the odor profile changes in GCC during room temperature storage were quantitatively revealed. In total, 19 key volatile compounds were identified and quantitated in fresh, spoilage, and serious spoilage GCC. Aroma recombination and omission experiments revealed that 11 compounds including (E)-2-hexenal, acetoin, α-terpineol, N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine, cyclohexane isothiocyanato, butylated hydroxytoluene, putrescine, cadaverine, histamine, TMA, and ammonia were the key OOCs of GCC during room temperature storage. Among them, acetoin, N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine, and TMA were found to contribute a fishy odor to GCC. (E)-2-hexenal was found to contribute significantly to the bitter almond odor after GCC spoilage. Cyclohexane isothiocyanate and cadaverine contributed a stink odor to GCC, especially during the last period of deterioration. Ammonia, putrescine, cadaverine and histamine played important roles in the ammoniacal odor of GCC. Moreover, the results of correlation analysis showed that 12 amino acids (Val, Met, Leu, Lys, His, Trp, Glu, Asn, Gln, Gly, Arg, and Tau) and 10 fatty acids (palmitic acid, arachidic acid, trichosoic acid, myristoleic acid, palmitic acid, heptadecenoic acid, elaidic acid, eicosenoic acid, arachidonic acid, and eicosatrienoic acid) played important roles in the formation of key OOCs in GCC during room temperature storage. In this study, the key OOCs of GCC during room temperature storage were analyzed, providing a theoretical basis for the composition analysis of freshwater fish during storage. In future studies, the differences in key odorous substances between room temperature and cold storage needed to be studied further.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hao Wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Chengwei Yu: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Yanan Sun: Formal analysis. Ning Cui: Investigation, Data curation. Bizhen Zhong: Investigation. Bin Peng: Investigation. Mingming Hu: Data curation. Jinlin Li: Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Zongcai Tu: Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program Gan-Po Juncai support program of Jiangxi Province (No.20232BCJ22021), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.32060557 and 32260635), Outstanding Youth Project of Jiangxi Natural Science Foundation (No.20224ACB215010), Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education Key Project (No. GJJ2200310), the earmarked fund for CARS (No.CARS-45). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.102011.

Contributor Information

Jinlin Li, Email: lijinlin405@126.com.

Zongcai Tu, Email: 004756@jxnu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Andre R.S., Mercante L.A., Facure M.H.M., Sanfelice R.C., Fugikawa-Santos L., Swager T.M., Correa D.S. Recent progress in amine gas sensors for food quality monitoring: Novel architectures for sensing materials and systems. ACS Sensors. 2022;7(8):2104–2131. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.2c00639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L., Ao Z., Tang T., Tong F., Wei Z., Yang F., Shu Y., Liu S., Mai K. Characterization of difference in muscle volatile compounds between triploid and diploid crucian carp. Aquaculture Reports. 2021;20 doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2021.100641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu H., Li C., Xu Y., Xu B. Revealing the characteristic aroma and boundary compositions of five pig breeds based on HS-SPME/GC-O-MS, aroma recombination and omission experiments. Food Research International. 2024;178 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.113954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y., Mei J., Xie J. Exploring the effects of lipid oxidation and free fatty acids on the development of volatile compounds in grouper during cold storage based on multivariate analysis. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;20 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerner M., Agustinelli S.P., Guccione S., Yeannes M.I. Effect of different preservation processes on chemical composition and fatty acid profile of anchovy (Engraulis anchoita) International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2015;66(8):887–894. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2015.1110687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerny M., Christlbauer M., Christlbauer M., Fischer A., Granvogl M., Hammer M.…Schieberle P. Re-investigation on odour thresholds of key food aroma compounds and development of an aroma language based on odour qualities of defined aqueous odorant solutions. European Food Research and Technology. 2008;228(2):265–273. doi: 10.1007/s00217-008-0931-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFAA Scientific opinion on risk based control of biogenic amine formation in fermented foods. EFSA Journal. 2011;9:2393–2486. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fangxue Chen L.S., Shi X., Deng Y., Qiao Y., Wu W., Xiong G.…Shi L. Characterization of flavor perception and characteristic aroma of traditional dry-cured fish by flavor omics combined with multivariate statistics. Lwt. 2023;173 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fereidoon Shahidi A.H. Role of lipids in food flavor generation. Molecules. 2022;27:5014. doi: 10.3390/molecules27155014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemert L.V. Science Press; 2015. Complications of flavour threshold values in water and other media. [Google Scholar]

- Habibeh Hashemian M.G., Dashtian K., Mosleh S., Hajati S., Razmjoue D., Khan S. Cellulose acetate/MOF film-based colorimetric ammonia sensor for non-destructive remote monitoring of meat product spoilage. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;249 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Jiang Q., Wang H., Li J., Tu Z. Insight into the effect of traditional frying techniques on glycosylated hazardous products, quality attributes and flavor characteristics of grass carp fillets. Food Chemistry. 2023;421 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Dong K., Wang Q., Huang X., Wang G., An F., Luo Z., Luo P. Changes in volatile flavor of yak meat during oxidation based on multi-omics. Food Chemistry. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui Tang P.L., Chen L., Ma J.K., Guo H.H., Huang X.C., Zhong R.M.…Jiang L.W. The formation mechanisms of key flavor substances in stinky tofu brine based on metabolism of aromatic amino acids. Food Chemistry. 2022;392 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinjin Ma Y.N., Zhang L., Yan X. Ratio of histamine-producing/non-histamine-producing subgroups of tetragenococcus halophilus determines the histamine accumulation during spontaneous fermentation of soy sauce. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2023;89 doi: 10.1128/aem.01884-22. e01884–01822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keli Zhong Y.Z., He Y., Liang T., Tian M., Wu C., Tang L.…Li J. A sensing label or gel loaded with an NIR emission fluorescence probe for ultra-fast detection of volatile amine and fish freshness. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2024;318 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2024.124501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohakunjit N. Postharvest survey of volatile compounds in five tropical fruits using headspace-solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) Hortence: A Publication of the American Society for Horticultural ence. 2007;42:309–314. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.42.2.309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C., Ke H., Huo Y., Yang Q., Liang P. Physicochemical, flavor, and microbial dynamic changes of cured large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) roe. ACS Food Science & Technology. 2023;3(4):683–698. doi: 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.2c00415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Fan W., Xu Y., Zhu D., Yang T., Li J. Characterization of key odorants in Chinese Texiang aroma and flavor type Baijiu (Chinese liquor) by means of a molecular sensory science approach. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2024;72(2):1256–1265. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c07053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhao Y., Zeng M., Xu X. Research progress of fishy odor in aquatic products: From substance identification, formation mechanism, to elimination pathway. Food Research International. 2024;178 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujie Chenga X.L., Tian Y., Wang Q., Li X., An F., Luo Z.…Huang Q. Mechanisms of cooking methods on flavor formation of Tibetan pork. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;19 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M.A.A., Magdy M., Tybussek T., Barth J., Buettner A. Comparative evaluation of wild and farmed rainbow trout fish based on representative chemosensory and microbial indicators of their habitats. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023;71(4):2094–2104. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c07868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria Carmela Ferrante R.M. Focus on histamine production during cheese manufacture and processing: A review. Food Chemistry. 2023;419 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed E., Darwish H.W., Darwish I.A., Saad A.S. Solid-state potentiometric sensor for the rapid assay of the biologically active biogenic amine (tyramine) as a marker of food spoilage. Food Chemistry. 2021;346 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukut Senapati P.P.S. Onsite fish quality monitoring using ultra-sensitive patch electrode capacitive sensor at room temperature. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2020;168 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju Podduturi G.d.S.D., Reinaldo J.d.S., Hyldig G., Jørgensen N.O.G., Petersen M.A. Characterization and finding the origin of off-flavor compounds in Nile tilapia cultured in net cages in hydroelectric reservoirs, S˜ ao Paulo state, Brazil. Food Research International. 2023;173 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Yang A.X., Chen Y., Sun N., Jinjie Z., Jia R., Huang T., Yang W. Effect of laver powder on textual, rheological properties and water distribution of squid (Dosidicus gigas) surimi gel. Journal of Texture Studies. 2020;51:968–978. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Septiana S., Yuliana N.D., Bachtiar B.M., Putri S.P., Fukusaki E., Laviña W.A., Wijaya C.H. Metabolomics approach for determining potential metabolites correlated with sensory attributes of Melaleuca cajuputi essential oil, a promising flavor ingredient. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2020;129(5):581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Majumdar R.K., Mehta N.K., Panda S.P., Ngasotter S. Enhancing the shelf life of Tilapia surimi with Mosambi peel extract: Protection against oxidative, structural, and textural degradation during frozen storage. ACS Food Science & Technology. 2024;4(2):436–446. doi: 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.3c00522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Zhang J., Sun H., Zu Z., Fu J., Fan R., Chen Q., Wang Y., Yue P., Ning J., Zhang L., Gao X. Sensomics-assisted characterization of fungal-flowery aroma components in fermented tea using eurotium cristatum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023;71(48):18963–18972. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c05273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai Zhuang H.H., Zhang L., Luo Y. Spoilage-related microbiota in fish and crustaceans during storage: Research progress and future trends. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2020;20:252–288. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai Zhuang X.L., Li Y., Zhang L., Hong H., Liu J., Luo Y. Biochemical changes and amino acid deamination & decarboxylation activities of spoilage microbiota in chill-stored grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) fillets. Food Chemistry. 2021;336 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai Zhuang Y.L., Gao S., Tan Y., Hong H., Luo Y. Mechanisms of fish protein degradation caused by grass carp spoilage bacteria: A bottom-up exploration from the molecular level, muscle microstructure level, to related quality changes. Food Chemistry. 2023;403 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Huang J.L., Fang Z., Yu W., Li Z., Xu D., Yang W., Zhang J. Preparation and characterization of irradiated kafirin-quercetin film for packaging cod (Gadus morhua) during cold storage at 4 °C. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2020;13:522–532. doi: 10.1007/s11947-020-02409-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Qu F., Wang P., Zhao L., Wang Z., Han Y., Zhang X. Characterization analysis of flavor compounds in green teas at different drying temperature. Lwt. 2022;161 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wangli Dai S.G., Xu M., Wang W., Yao H., Zhou X., Ding Y. The effect of tea polyphenols on biogenic amines and free amino acids in bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis) fillets during frozen storage. Lwt. 2021;150 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaojing Zhang P.G., Xia W., Jiang Q., Liu S., Xu Y. Characterization of key aroma compounds in low-salt fermented sour fish by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, odor activity values, aroma recombination and omission experiments. Food Chemistry. 2022;397 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li L., Regenstein J.M., Gao P., Zang J., Xia W., Jiang Q. The contribution of autochthonous microflora on free fatty acids release and flavor development in low-salt fermented fish. Food Chemistry. 2018;256:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Shen L.H., Xia B., Ni Z., Elam E., Thakur K., Zhang J., Wei Z. Effects of different sulfur-containing substances on the structural and flavor properties of defatted sesame seed meal derived Maillard reaction products. Food Chemistry. 2021;365 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Fan W., Xu Y. Characterization of key aroma compounds in pixian broad bean paste through the molecular sensory science technique. Lwt. 2021;148 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhenlei Liu W.Y., Huamao W., Deng S., Xunxin Y., Huang T. The mechanisms and applications of cryoprotectants in aquatic products: An overview. Food Chemistry. 2023;408 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.135202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., He C., Qin M., Luo Q., Jiang X., Zhu J.…Ni D. Characterizing and decoding the effects of different fermentation levels on key aroma substances of Congou black tea by sensomics. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023;71(40):14706–14719. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang S., Liu Y., Gao S., Tan Y., Hong H., Luo Y. Mechanisms of fish protein degradation caused by grass carp spoilage bacteria: A bottom-up exploration from the molecular level, muscle microstructure level, to related quality changes. Food Chemistry. 2023;403 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.