ABSTRACT

As a chronic gynecological disease, endometriosis is defined as the implantation of endometrial glands as well as stroma outside the uterine cavity. Proliferation is a major pathophysiology in endometriosis. Previous studies demonstrated a hormone named melatonin, which is mainly produced by the pineal gland, exerts a therapeutic impact on endometriosis. Despite that, the direct binding targets and underlying molecular mechanism have remained unknown. Our study revealed that melatonin treatment might be effective in inhibiting the growth of lesions in endometriotic mouse model as well as in human endometriotic cell lines. Additionally, the drug–disease protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was built, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was identified as a new binding target of melatonin treatment in endometriosis. Computational simulation together with BioLayer interferometry was further applied to confirm the binding affinity. Our result also showed melatonin inhibited the phosphorylation level of EGFR not only in endometriotic cell lines but also in mouse models. Furthermore, melatonin inhibited the phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase (PI3K)—protein kinase B (Akt) pathway and arrested the cell cycle via inhibiting CyclinD1 (CCND1). In vitro and in vivo knockdown/restore assays further demonstrated the involvement of the binding target and signaling pathway that we found. Thus, melatonin can be applied as a novel therapy for the management of endometriosis.

Keywords: CCND1, cell cycle, EGFR, endometriosis, melatonin, PI3K/AKT, proliferation

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disease characterized by the implantation of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity [1]. It affects 5% to 10% of women aged 25 to 35 years old worldwide [2]. Endometriosis induces symptoms including pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility [3]. The prevailing theory regards retrograde menstruation as a critical mechanism triggering endometriotic lesions. During menstruation, viable endometrial fragments with high proliferative ability reflux through the fallopian tubes to adhere and grow on the peritoneal surface, ovary or other cavity, causing invasion growth [4, 5]. Hence, proliferation is identified as one of the major pathophysiology and signal transduction pathways to the progression of endometriotic lesions [6] [7]. Though hormone treatment or surgical therapies are currently applied for endometriosis therapy, however, existing methods exhibited adverse effects such as an increased risk of damaging ovarian reserve [8, 9]. Therefore, developing a novel therapeutical approach is urgently needed to improve the current treatments for endometriosis.

Melatonin (N‐acetyl‐5‐methoxytryptamine), a pleiotropic molecule synthesized and released mainly from the pineal gland, is a circadian rhythm regulator with multiple beneficial effects on female reproductive function [10]. Effects of melatonin in the reproductive system can be put down to its well‐characterized antioxidative effect and other biological functions, such as anti‐cell proliferation, pro‐apoptosis, regulation of steroid hormone production, antiangiogenic activity, regulation of immune modulation as well as neurotrophic effects [11, 12, 13]. Hence, it holds the potential as an effective therapeutic agent for endometriosis. Animal studies have shown that melatonin treatment decreased the volume and weight of endometriotic lesions [14, 15]. A clinical study also observed that melatonin treatment significantly reduced the pain score in endometriosis patients [16]. Although lesion size and pain may not be directly correlated, melatonin appears to exert beneficial effects on both aspects of the disease which warrants for further studies. Recently, it has been determined that melatonin conducted its antiproliferative activity on endometriosis not through its receptor‐dependent mechanisms [17]. However, this is yet to be studied in detail.

Despite its potential therapeutic use, the precise targets and mechanism of action of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis have not been fully elucidated. Hence, we provide in‐depth investigation by integrating silicon analysis and in vivo and in vitro study to unearth the binding targets, cellular signaling, and underlying mechanism of melatonin on the prevention and treatment of endometriosis at the molecular level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Model

To establish an endometriosis model, female C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old), were provided by the Laboratory Animal Service Center and housed in a pathogen‐free environment. Animal ethics reference no. 13‐037‐MIS & 21‐139‐MIS and animal license reference no. (20‐765) in DH/HT&A/8/2/1 Pt.11. The mouse model allows for a controlled study of basic disease mechanisms and provides reproducible results for evaluating therapeutic responses.

Experiment 1: Before surgery, anesthesia (ketamine [100 mg/kg], xylazine [10 mg/kg] in saline water [0.9%]) was administered via intraperitoneal injection. Mice received ovariectomy 7 days before the transplantation of endometrial tissue obtained from donor mice. Subsequently, 100 μg/kg estradiol‐17β (E2; Sigma, Cat. E2758) was intramuscularly injected to synchronize the E2 cycle every 5 days [18]. Endometriotic tissues of the uterine fragments obtained from killed donor mice were cut into fragments (2 mm) with the help of a dermal biopsy punch (Miltex). Subsequently, the establishment of the endometriosis model was achieved on Day 0 through subcutaneous transplantation of four endometrial tissues into the subcutaneous pockets on the abdominal wall of each individual mice, as previously described.

Experiment 2: Following a 1‐week recovery period, mice were allocated into two groups in random, with a daily intraperitoneal injection of a vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] in PBS) or melatonin (10 mg/kg) for 3 weeks (n = 5 per group). Subsequently, two groups of mice were euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation, and the lesions were excised for further analysis.

Experiment 3: The protocol described in experiment 1 was followed in another 20 C57/BL6 female mice. After a 1‐week recovery period, mice were allocated into four groups in random: vehicle, melatonin (10 mg/kg), tyrphostin 4‐(3‐chloroanilino)‐6,7‐dimethoxyquinazoline (AG1478, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the autophosphorylation of EGFR) (10 mg/kg), and melatonin with AG1478 (n = 5 per group). The mice received intraperitoneal injections each day for three continuous weeks and were euthanized finally, with lesions excised. The 10 mg/kg dose was chosen based on previous studies showing therapeutic efficacy in endometriosis models [19, 20]. This dose has been shown to be well‐tolerated and achievable in endometriosis treatment.

After excised, lesions were frozen for the extraction of RNA/protein or paraffin‐embedded for further histological analysis.

2.2. Cell Culture

Two human endometriotic cell lines of Hs832(C).T & 12Z were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA, CRL‐7566) and abm (Richmond, BC, Canada, T0764), respectively. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/nutrient mixture F‐12 Ham medium (Gibco, cat.1103902) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, cat. A4736301) as well as 100 U/mL Penicillin‐Streptomycin (Gibco, cat.15140122) at the temperature of 37°C with 5% CO2 and atmospheric O2 concentration (~20%) in a humidified environment. For the treatments, cells were cultured in six‐ well plates filled with culture medium (2 mL). To induce quiescence before treatments, cells were grown to 70%–80% confluence and then serum starved in a medium without FBS for a period of 24 h.

Melatonin, AG1478, and BYL719 were dissolved in DMSO. For pharmacological inhibitor experiments, specific inhibitors were used to pretreat cells for 1 h before adding melatonin. Following incubation with an inhibitor for 1 h, melatonin was directly added into the well. Subsequently, experimental groups were exposed to all the relevant vehicles and each experiment was at least triply repeated with corresponding passages of cells.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin‐embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 8 min. Sections were further treated with a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h, sections were incubated with specific primary antibodies overnight (4°C) following HRP‐conjugated secondary antibody incubation. Slides were developed using the Dab + , Liquid, 2‐component system (Dako, cat. K346811‐2) and counterstained with hematoxylin. For image capturing, five fields were randomly selected from each section of the individual samples (Leica DM6000B microscope). The integrated optical density values were measured by using Qupath v0.3.1 software. The final cell count was reported as the average of the five fields.

2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation assay was done using 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma‐Aldrich, cat. M5655). HS293(C). T and 12Z cells were seeded in 96‐well assay plates (3000 cells per well) and incubated at 37°C with melatonin treatment in a range from 0 to 100 μM for 24, 48 and 72 h. At the end of incubation, cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT for an additional 3 h. The crystal formazan was dissolved in DMSO. Finally, the concentration was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader, with a wavelength of 630 nm as a reference.

2.5. Crystal Violet Staining

HS293(C). T and 12Z cells were seeded in 6‐well plates. Upon completion of incubation, cells were first stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution (Abcam, cat. 246820) for 20 min (R.T.) and washed by 1× PBS. Then cells were air‐dried for photograph following the standard protocol.

2.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis

To evaluate the cell cycle progression, the harvested cells were fixed with 70% ethanol, and stained with Cell Cycle Analysis Kit (Sigma‐Aldrich, cat. MAK344) complying with the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The measurement of fluorescence intensity was achieved by a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX LX Flow Cytometer in FL‐2 channel.

2.7. Human Samples

Laparotomic or laparoscopic surgery was conducted to obtain ectopic and eutopic endometriotic tissue sections. Patients diagnosed with ovarian or peritoneal endometriosis were included in the study. The diagnosis of endometriosis was made based on clinical symptoms, ultrasound imaging, and confirmation by laparotomic or laparoscopic surgery. Infertile women without endometriosis served as control patients. For control patients, the absence of endometriosis was confirmed through clinical evaluation and ultrasound. Demographic characteristics of the participants were listed in Supporting Information S1: Table 1. This study was approved by the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong and The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Human ethics reference no. 2014.144‐T. All patients had informed written consent before tissues collection.

2.8. Identification of Melatonin Targets and Endometriosis‐Associated Targets

SwissTargetPrediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) was used for the prediction of the potential melatonin targets. Batman (http://bionet.ncpsb.org/batman-tcm/) as well as SEA (http://sea.bkslab.org/) databases were also adopted to identify the known melatonin targets. Targets associated with endometriosis were identified from the CTD (http://ctdbase.org/), GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), as well as NCBI Gene databases (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/). Meanwhile, these targets were further validated and cross‐checked using the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Thresholds based on confidence scores and interaction probabilities (above 0.7) were applied to identify high‐confidence interactions.

2.9. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Analysis

Venny 2.1 was used to obtain common melatonin and endometriosis targets (potential therapeutic targets). Cytoscape 3.7.2 was adopted for the construction of a drug–target–disease network. Additionally, String version 11 (https://string-db.org) was used for protein network analysis, with a medium confidence threshold of 0.7 to define the PPI. Default enrichment was carried out to illustrate the network around the input. To elucidate the effect of potential therapeutic targets on gene functions/signaling pathways, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were carried out using ClusterProfiler package of R 3.6.3. Besides, the KEGG Pathway database (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html) was employed to recognize the class of each KEGG pathway, preparing for further analysis.

2.10. In Silico Molecular Analysis

Molecular docking was used for the prediction of the noncovalent binding of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) to melatonin. The PDB structure of EGFR and ERBB2 was obtained from a protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org). Besides, Autodock Tools (version 4.2) as well as Autodock Vina (version 1.1.2) were operated to stimulate the affinity energy of complexes as previously described. Ligplot (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LIGPLOT/) was adopted to render the 2D interaction scheme of ligand‐protein complexes and identify the residues involved in intermolecular interaction as previously described. In addition, Autodock was utilized to render the 3D interaction scheme of ligand‐protein complexes.

2.11. Octet Biorad96e Analysis

Recombinant proteins of EGFR and ERBB2 (Abcam) were immobilized to an Octet® Super Streptavidin (SSA) biosensors (Sartorius) using an Octet RED96e (FortéBio). To investigate binding kinetics assays, a serial dilution of 6 concentrations (1, 10, 100, 1000 uM) of melatonin was dissolved in DMSO, and PBS was added to a black polypropylene 96‐well microplate (Greiner Bio‐one, Frickenhausen, Germany). Each assay cycle, composed of baseline incubation in PBS, association in compound solution, as well as dissociation in PBS, was repeatedly performed for every concentration with an RBD‐loaded/blank probe. Data were analyzed by using Octet Data Analysis HT v.10.

2.12. Western blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (Sigma‐Aldrich, cat. C2978) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Sigma‐Aldrich, cat. P8340) and protease/phosphatase Inhibitor (Cell Signaling Technology. Cat 5872). After separation by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transfer onto PVDF membranes, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h and incubated subsequently with primary antibodies diluted in 5% nonfat milk/TBS for overnight at 4°C and matched HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Bio‐Rad Laboratories) and imaged with a ChemiDoc MP Imager (Bio‐Rad Laboratories).

2.13. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real‐Time PCR (RT‐qPCR)

Lesions were collected in RNA later solution at the temperature of 4°C and incubated for a period of 24 h. The supernatant tissues were stored at the temperature of −80°C for use. The extraction of total RNA was carried out using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) complying with the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Subsequently, RNA (500 ng) was reverse‐transcribed into first‐strand cDNA with the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time) (Takara; cat RR036A). Gene expression was amplified by TB Green Premix ExTaq (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara; cat RR420A), followed by quantitation by LightCycler 480 quantitative PCR system (Roche, Switzerland). PCR primers for all examined genes were listed in Supporting Information S1: Table 2. RT‐qPCR was triply performed, with the mean value of mRNA levels calculated. The comparative Ct method was adopted to relatively quantify mRNA levels, with GAPDH serving as the reference gene and the formula 2–ΔΔCt for calculation.

2.14. Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Transfection

SiRNA transfection was adopted to knock down endogenous EGFR and phosphatidylinositol‐4, 5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) expression. Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) was used to transfect cells with siEGFR and siPIK3CA (Santa Cruz). The siCONTROL siRNA (Santa Cruz) was used as the transfection control.

2.15. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the PRISM software package (version 9). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. All experiments were obtained from at least three independent experiments. The number of replicates for each in vitro experiment was 3 (n = 3) and the number of animals per group in the in vivo studies was 5 (n = 5). For data comparison, two‐tail Student's t‐test or one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test were employed accordingly. Statistical significance was defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

3. Results

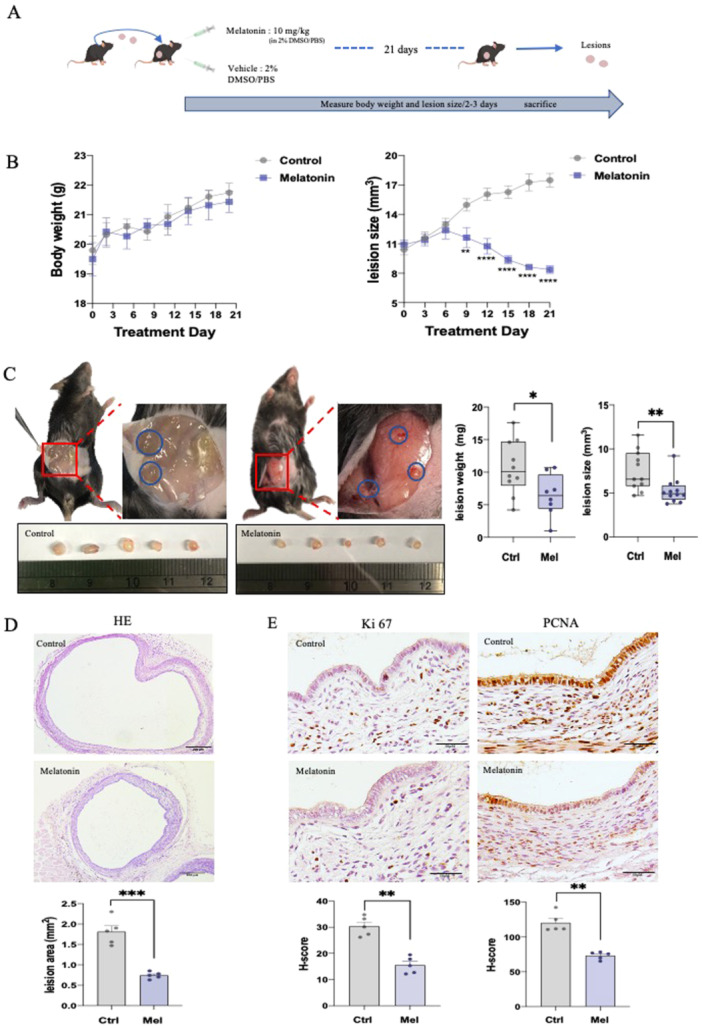

3.1. Administration of Melatonin Blocked the Development of Endometriotic Lesions Among C57/BL6 Mice

we first evaluate the therapeutic effects of melatonin on endometriotic lesions in vivo using an experimental endometriosis mouse model. Seven to eight weeks female mice were subject to 100 μL of DMSO (vehicle) or melatonin (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) daily over a 3‐week period (Figure 1A). During the administration, lesion size was significantly diminished in the melatonin‐treated mice with unchanged body weight compared to DMSO control groups (Figure 1B). After treatment, both the net weight and size of the lesion were significantly decreased in the melatonin‐treated group (Figure 1C). In addition, the H&E staining histology of the endometriotic lesions showed the lesion area was significantly decreased in melatonin‐treated group compared with the control group (Figure 1D). The expressions of Ki67 and PCNA, as proliferative marker proteins, were also decreased in the lesions of mice with melatonin treatment (Figure 1E). Melatonin was shown to be effective in the suppression of lesion growth without affecting body weight in endometriosis mouse model. Moreover, the proliferative markers expression levels were decreased after melatonin treatment in vivo.

Figure 1.

Administration of melatonin suppressed the development of endometriotic lesions in C57/BL6 mice (n = 5/group). (A) In vivo mouse model (schematic). (B) Body weight and lesion size were measured every 2–3 d. (C) Representative images of endometriotic lesions implanted in mouse subcutaneous. After sacrificing, lesions were isolated, photographed, measured and weighted. (D) Representative H&E staining images of lesions. (E) IHC staining of Ki67 and PCNA in paraffin sections of lesions. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

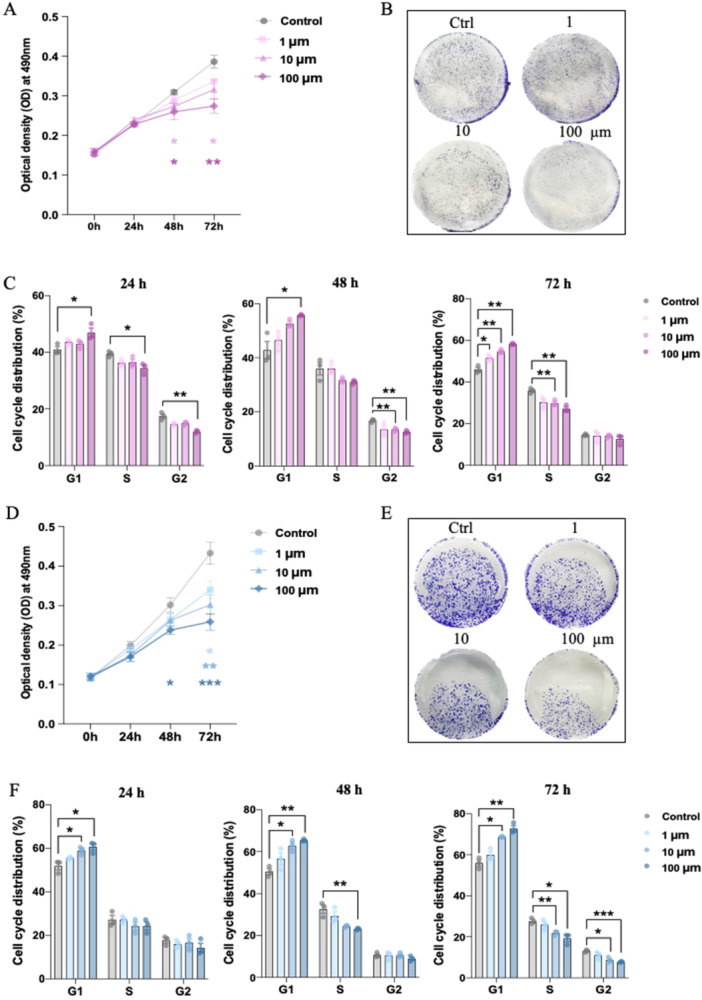

3.2. Inhibition of Melatonin on the Cell Growth in Endometriotic Cells

To investigate the anti‐proliferation effect in depth, we employed two widely used endometriotic cell lines, 12Z and Hs832(C).T cells, to verify the impact of melatonin on the growth of endometriotic cells. Both 12Z and Hs832(C).T cells were administered with escalating doses of melatonin (1, 10, and 100 μM) for 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. We found a growth inhibitory effect of melatonin on the cells particularly after 48 and 72 h, this inhibitory effect was markedly evident at the 100 μM dosage (Figure 2A,D). The crystal violet assay also showed a significant reduction in both the number and size of colonies formed by the 12Z and Hs832(C).T cells with melatonin treatment (Figure 2B,E). To ascertain the potential for melatonin‐induced cell growth suppression, we conducted a cell cycle progression analysis. After melatonin treatment, both cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and assessed cell cycle distribution using flow cytometry. Results showed that the percentage of G1 phase of 12Z & Hs832(C).T cells was upregulated following 100 μM melatonin treatment (Figure 2C,F and Figure S1A,B). We further tested the effect of melatonin on various genes that are related to the regulation of the cell cycle. As shown in Figure S1C,D, the decreasing effects on CCND1 were observable in 12Z & Hs 832(C).T cells. These findings suggested the inhibition effects of melatonin treatment on endometriotic cell proliferation through cell cycle arrest. Furthermore, CCND1 was regarded as the main factor to regulate the cell cycle process after melatonin treatment in endometriosis.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effects of melatonin on the cell growth in endometriotic cells (n = 3/group). (A, D) MTT assay analysis of cell viability in 12Z and Hs 832(C).T cell lines with melatonin treatment. (B, E) Crystal violet stain assay of 12Z and Hs 832(C). T cell lines with melatonin treatment. (C, F) Cell cycle distribution of 12Z and Hs 832(C).T cell lines with melatonin treatment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

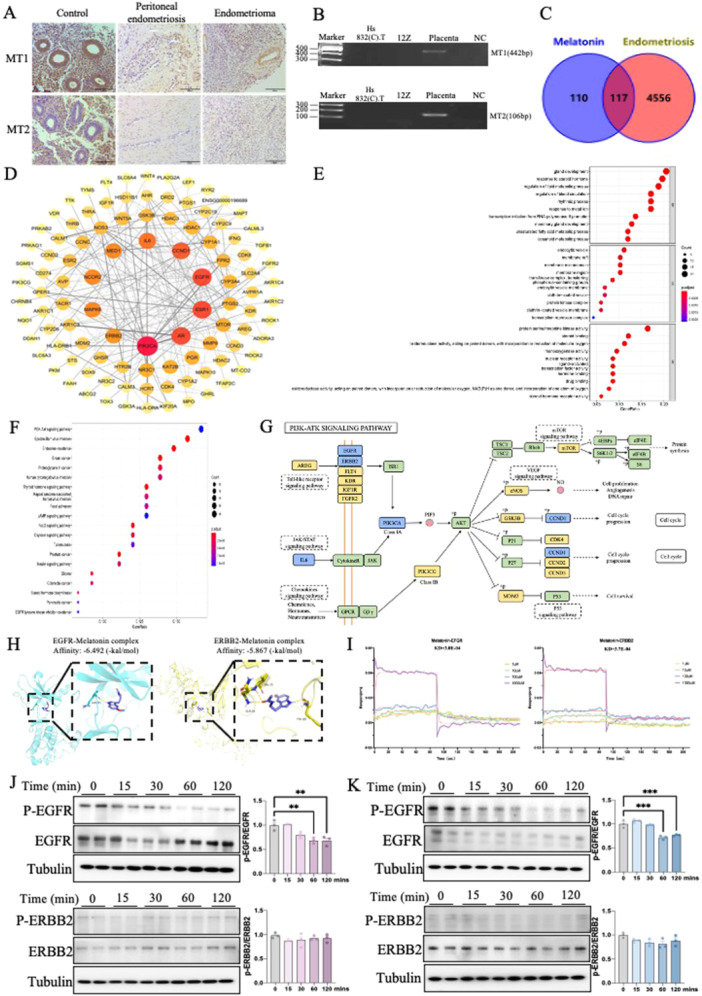

3.3. Melatonin Inhibited Endometriosis via a Non‐Classic Pathway

Typically, melatonin binds to its conventional receptors (MT1 and MT2) to regulate intracellular signaling. However, in certain cases, it may exert its functions through receptor‐independent activity. To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which melatonin acts in endometriosis, we first examined the immunostaining of melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2) in normal and endometriotic tissues. The primary goal of this immunostaining is to determine spatial distribution patterns of melatonin receptors in endometriosis. However, melatonin receptor expression levels were not detectable in ectopic peritoneal lesions compared to the control endometrium using the IHC method (Figure 3A). We further tested their gene expression level by RT–qPCR amplification with specific primers yielded the expected single amplicon of MT1 (442 bp) and MT2 (106 bp). We chose the placenta as a positive control due to the known high expression of melatonin receptors in this tissue [21]. The gel of PCR production showed the expression levels of melatonin receptors were absent in both 12Z & Hs832(C).T cells compared with human placental tissue (positive control) (Figure 3B). Therefore, our findings suggest melatonin may exert its protective effects via nonclassical pathway.

Figure 3.

Melatonin inhibits endometriosis via a non‐classic pathway. (A) IHC staining was performed to detect the expression levels of MT1 and MT2 in normal and endometriosis patients. (B) MT1 and MT2‐specific primers and visualized in agarose gels by ethidium bromide staining. (C) 117 collective targets of melatonin and endometriosis were identified. (D) Protein‐protein interaction network of these collective targets. The node sizes and colors are illustrated from red to yellow and big to small in descending order of degree values. (E, F) Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of collective targets of melatonin and endometriosis. Top 10 significantly enriched terms in biological processes (BPs), molecular functions (MFs) and cellular components (CCs) respectively. Top 20 significantly enriched KEGG pathways statistics. The X‐axis is the GeneRatio of the term and the Y‐axis is the name of the terms. The darker the color, the smaller the adjusted p‐value. The larger the circle, the greater the number of target genes in the term. (G) Distribution of the most potential therapeutic targets on significantly enriched PI3K‐AKT signaling pathway. The blue nodes represent key genes, the yellow nodes represent overlapping targets of melatonin and endometriosis targets, and the green nodes represent the other targets in the PI3K‐AKT signaling pathway. (H) The interaction of melatonin with EGFR and ERBB2 was analyzed by molecular docking. (I) The binding affinity of melatonin with EGFR and ERBB2 was measured by bio‐layer interferometry assay. (J, K) The levels of p‐EGFR and p‐ERBB2 with melatonin treatment in 12Z (n = 3) and Hs 832(C).T (n = 3) cell lines were evaluated by western blot analysis, and their relative intensity were calculated by Image J. NC (negative control), water. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

To investigate the potential underlying mechanism of melatonin cure endometriosis, we then employed in silloc screening to identify the cross‐over genes of melatonin and endometriosis. A total of 227 genes related to melatonin was predicted from Swiss Target Prediction, Batman, SEA and uniport database based on the pharmacophore model as well as the principle of structural similarity. We screened out 4,673 endometriosis‐related genes from GeneCards, NCBI and CTD databases. As shown in the Venn diagram, there was a total of 117 candidate genes intersected between those two gene groups (Figure 3C). We then constructed a protein‐protein interaction (PPI) network based on those candidate genes using STRING software (Figure 3D). The prioritization of key targets was analyzed according to the degree, betweenness centrality, average shortest path length and closeness centrality of the nodes. The most potential top 10 targets were PIK3CA, AR, EGFR, ESR1, CCND1, IL6, MAPK8, MED1, NCOR2, and ERBB2. Moreover, GO enrichment showed the top 10 GO terms of biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions (Figure 3E). Importantly, when we further annotated the potential genes into the KEGG pathway, we identified those key genes were mainly distributed in the phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase (PI3K) ‐ protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway, indicating a novel potential signaling for melatonin ameliorate endometriosis (Figure 3F,G). The PI3K/AKT pathway plays a pivotal role in both cellular proliferation as well as survival, especially in endometriosis. Studies have demonstrated the exploration of the PI3K/Akt pathway, particularly in terms of its involvement in cell cycle progression, represents a significant advancement in addressing the existing challenges associated with treating endometriosis. Meanwhile, EGFR and ERBB2, which were among the top 10 potential targets, were also involved in the PI3K/Akt pathway. While other identified targets such as ESR1 could potentially affect the PI3K/Akt pathway, existing literatures showed in the ectopic endometrium from the cyst walls of ovarian endometriomas, ESR1 mRNA and the expression of protein ERα were attenuated compared with eutopic endometrial tissues and cells [22]. Thus, it could be inferred that melatonin might mainly target EGFR and ERBB2 and then affect the PI3K/Akt pathway to regulate cell cycle progression in endometriosis. To investigate whether melatonin mediates endometriosis through this signal, we first evaluated the interactions between melatonin and EGFR/ERBB2 by molecular docking and biolayer interferometry (BLI) analysis. The 2D and 3D interaction schemes showed the binding pockets and interactions of EGFR‐melatonin (affinity energy of ‐6.492 kcal/mol) and ERBB2‐melatonin (affinity energy of ‐5.867 kcal/mol) complexes. We further examined the association and dissociation constant of the 2 targets to melatonin bindings using BLI with an Octet RED96e system for confirmation. The equilibrium constant (KD) of EGFR‐melatonin and ERBB2‐melatonin were 300 and 370 μM, respectively. Both computation stimulation of affinity energy and BLI analysis of kinetic affinity confirmed that melatonin had the ability to stably bind to EGFR and ERBB2 (Figure 3H,I and Figure S2).

Additionally, we performed a western blot to confirm our computational results. Melatonin was added in the cells with a series dosages for different time points, melatonin significantly decreased phosphorylated EGFR (p‐EGFR) in both 12Z & Hs832(C).T cells. By contrast, it did not significantly change the level of p‐ERBB2 in both two cell lines (Figure 3J,K). In support of this data, our in vivo study also demonstrated that melatonin can significantly decrease phosphorylated EGFR (p‐EGFR) in endometriotic lesions (Figure S3). Overall, our findings suggested that the melatonin‐classical pathway was abolished in endometriotic cells due to a lack of classical receptors MT1 and MT2. However, melatonin may prevent the endometriosis onset through the PI3K‐Akt pathway by targeting EGFR phosphorylation.

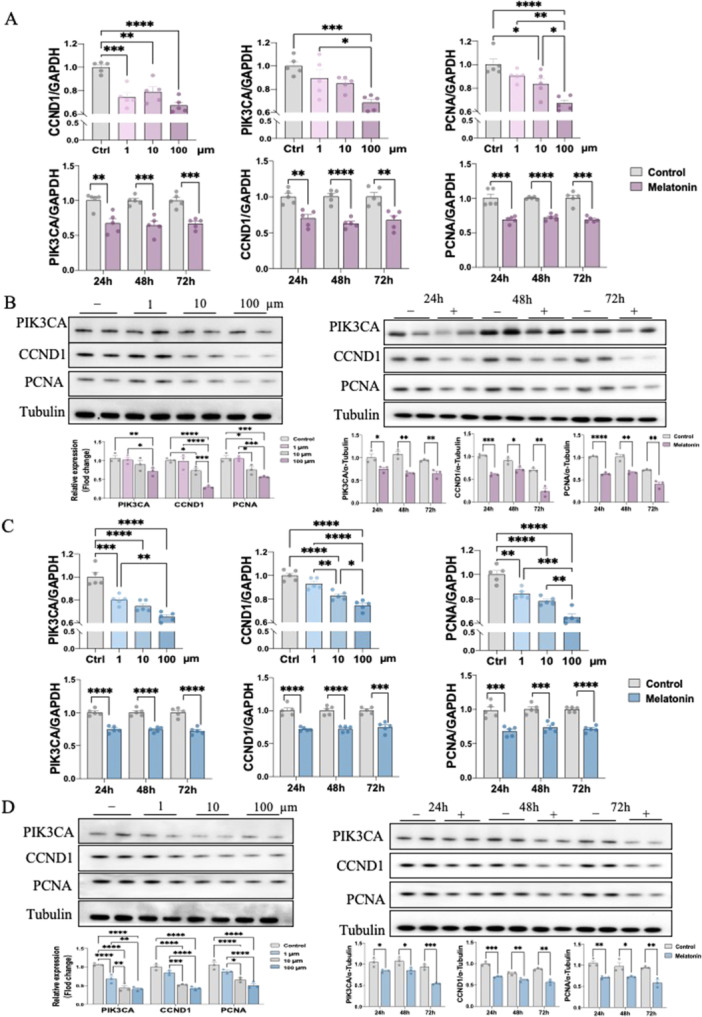

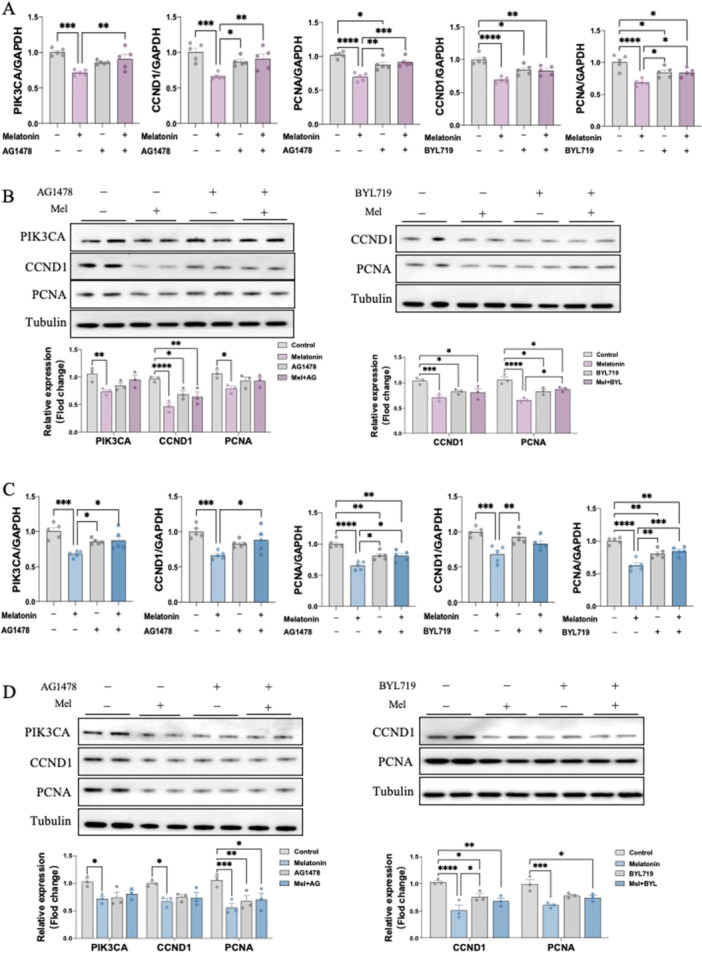

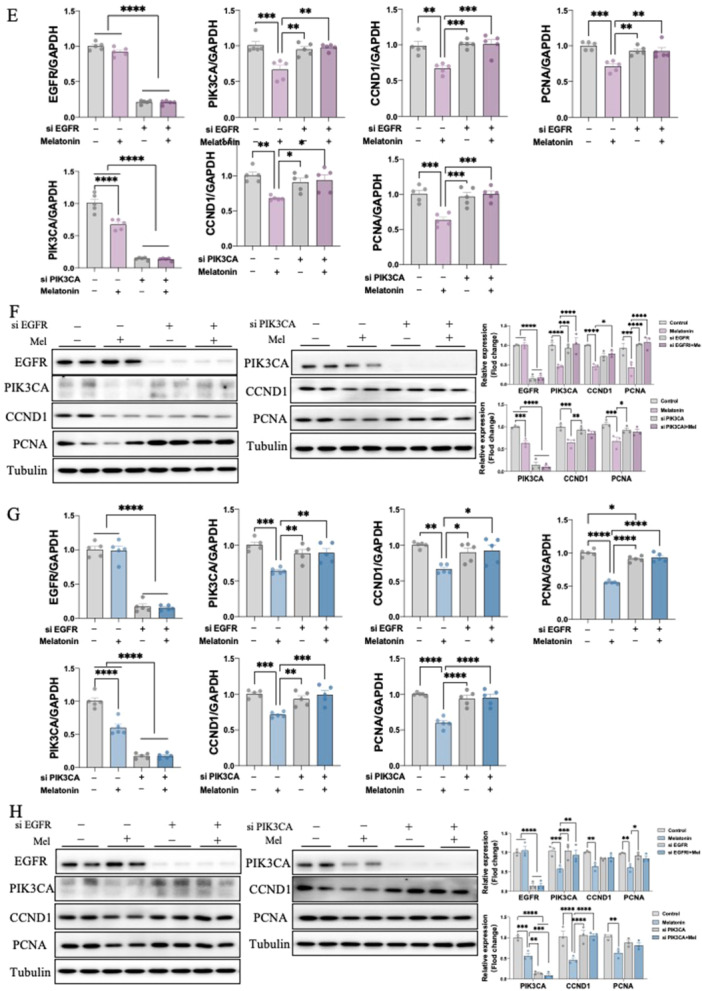

3.4. Inhibitory Mechanism of Melatonin on Endometriosis In Vitro

To investigate the downstream pathway of how melatonin activates EGFR signaling, we then performed in vitro experiments in 12Z & Hs 832(C).T cells. Notably, melatonin treatment resulted in significant inhibitory effects on downstream gene expression including, PIK3CA, CCND1, as well as proliferation marker PCNA in a dosage‐dependent manner at 24, 48 and 72 h (Figure 4A,C). We further confirmed their effects on protein levels using western blot (Figure 4B,D). Interestingly, pre‐treating 12Z & Hs 832(C).T cells with EGFR antagonist, AG1478, reversed the inhibitory effect of melatonin on the mRNA and protein expression level of PIK3CA, CCND1 and PCNA. Likewise, alpelisib (BYL719), a PIK3CA antagonist, also prevented the melatonin‐induced CCND1 and PCNA downregulation (Figure 5A–D). Next, to further validate whether melatonin exerts anti‐endometriosis function through the EGFR/PIK3CA pathway, we knockdown these two key factors in both 12Z & Hs 832(C).T cells using specific siRNA. The transfection efficiencies of siRNA sequences of EGFR and PIK3CA were detected by both RT‐qPCR and western blot, with high efficiencies to remarkably decreasing EGFR and PIK3CA expression, respectively (Figure 5E–H). our result demonstrated that EGFR knockdown abolished the downregulation of mRNA and protein expressions of PIK3CA, CCND1 and PCNA by melatonin treatment in 12Z & Hs 832(C).T cells. Similarly, silence PIK3CA restored the reduced expressions of CCND1 and PCNA after melatonin treatment (Figure 5E–H). Therefore, by employing in vitro studies with function‐in and function‐out experiments, our findings suggested that melatonin prevents endometriosis through EGFR/PIK3CA/CCND1 pathway.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory mechanism of melatonin on endometriosis in vitro (n = 3/group). (A, C) The RNA expression levels of PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA in 12Z and Hs 832(C).T cells were determined by RT‐qPCR. (B, D) The protein expression levels of PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA in 12Z and Hs 832(C).T cells were determined by western blot and their relative intensity were calculated by Image J. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

EGFR and PIK3CA directly mediate the inhibiting effects of melatonin in endometriotic cell lines (n = 3/group). 12Z and Hs 832(C).T cells were pretreated with vehicle control (DMSO), AG1478, or BYL719 for 1 h and then exposed to melatonin for 24 h. (A and C) The RNA expression levels of PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA were determined by RT‐qPCR. (B, D) The protein expression levels of PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA were determined by western blot and their relative intensity were calculated by Image J. 12Z and Hs 832(C).T Cells were transfected with 100 nM control siRNA (si‐Ctrl), EGFR siRNA (si‐EGFR) or PIK3CA siRNA (si‐PIK3CA) for 24 h and then treated with melatonin for 24 h. (E, G) The RNA expression levels of EGFR, PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA were determined by RT‐qPCR. (F, H) The protein expression levels of EGFR, PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA were determined by western blot and their relative intensity were calculated by Image J. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

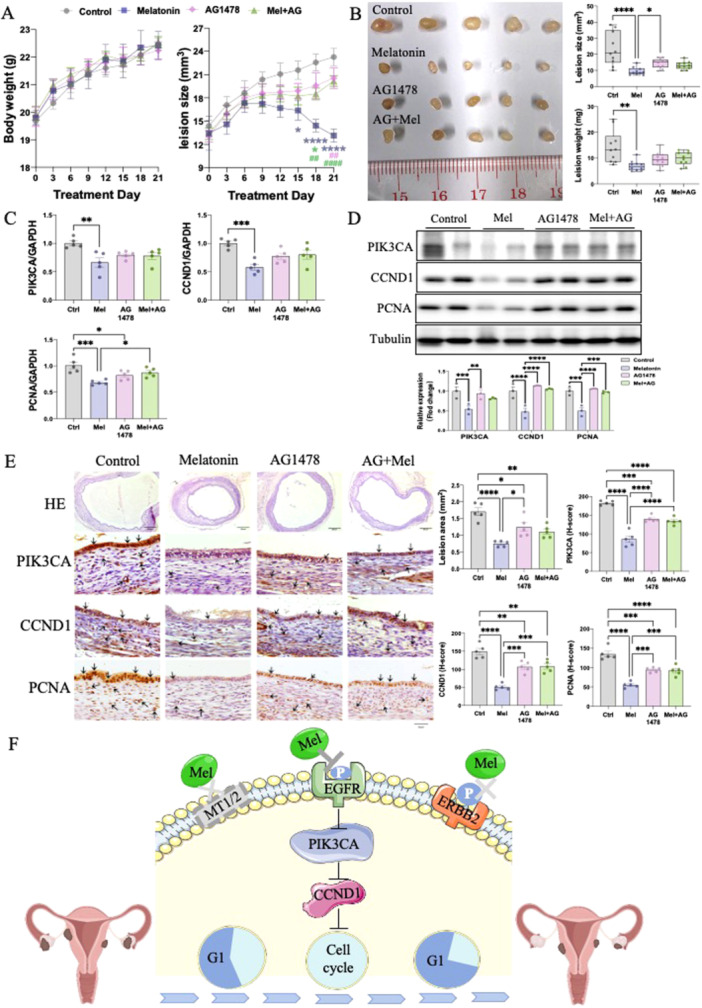

3.5. Inhibitory Mechanism of Melatonin on Endometriosis In Vivo

To validate the mechanism of melatonin in vivo, the EGFR‐specific inhibitor AG1478 was adopted to block its function. Endometriosis models established following the same method, mice received DMSO (vehicle control), AG1478 (10 mg/kg), melatonin (10 mg/kg) with/without AG1478 (10 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection for three continuous weeks. During treatment, no significant changes in body weight were recorded across different treatment groups (Figure 6A). For lesions size, only melatonin‐treated mice exhibited significantly smaller lesions. However, the therapeutic effects of melatonin were largely blocked when combined with AG1478 injection (Figure 6B). We further isolated lesions from each group after sacrifice. Results showed a significantly decreased net lesion weight and size in the melatonin‐treated group. By contrast, no significant difference was observed when blocking EGFR using AG1478 (Figure 6B). Furthermore, changes in the mRNA and protein expression level of endometriotic lesions. Comparable outcomes to those observed in the aforementioned in vitro functional studies were noted, and melatonin treatment presented a similar inhibitory effect on PIK3CA and CCND1, as well as PCNA. These data also showed that a combination of melatonin and AG1478 treatment could recover the downregulating effects of melatonin alone (Figure 6C,D). The lack of alterations in melatonin with the AG1478 group suggests that after AG1478 blocked the EGFR signaling, the action of melatonin in endometriosis was also blocked sufficiently. This result implies that melatonin's effects are dependent on EGFR activity. Similar results were further observed and confirmed using HE & IHC staining (Figure 6E). Taken together, it could be inferred that melatonin might bind to EGFR and suppress its phosphorylation, reducing the levels of PIK3CA and CCND1, thereby arresting the cell cycle and inhibiting proliferation in endometriosis (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Inhibitory mechanism of melatonin on endometriosis in vivo (n = 5/group). (A) Body weight and lesion size were measured every 2–3 d throughout the treatments. (B) Representative endometriotic lesions were photographed, measured, and weighed from each group. (C) PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA mRNA levels in endometriotic lesions were examined by RT‐qPCR. The protein expression levels of PIK3CA, CCND1and PCNA in each group were determined by western blot and their relative intensity was calculated by Image J. (E) Representative H&E staining images of lesions. IHC staining of PIK3CA, CCND1 and PCNA in paraffin sections of lesions. (F) Schematic representation of melatonin‐induced mechanisms in endometriosis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Collectively, our results suggest that melatonin inhibits proliferation in endometriosis through binding to EGFR, suppresses its phosphorylation, and reduces PIK3CA and CCND1 levels.

4. Discussion

This study elucidates the mechanism underlying melatonin's inhibitory effect on endometriosis both in vitro and in vivo, contributing valuable insight to the existing literature on potential therapeutic strategies for this condition.

Melatonin is involved in various biological processes, including cell viability, homeostasis, oxidative stress, as well as inflammation [23]. Typically, it binds to its conventional receptors to regulate intracellular signaling. However, in certain cases, it may exert its functions through receptor‐independent activity [24] [25]. For instance, previous studies showed that in a receptor‐independent manner, melatonin could reduce the overproduction of androgens. The administration of luzindole failed to restore the lowered mRNA levels of steroidogenic enzymes among porcine theca cells [26]. Meanwhile, receptor‐independent melatonin pathways were also investigated in the context of hyperbaric hyperoxia, hyperthyroidism, as well as sepsis [24]. Melatonin was also found to operate in a receptor‐independent fashion by binding to nuclear receptors to modulate proliferation [27]. Based on the above evidence, melatonin is thought to serve as either a paracrine or a tissue factor, which is reliant on the cellular environment with different endocrine signaling [23]. We confirmed a lower expression of melatonin receptors among endometriotic tissues and endometriotic cells. As previously demonstrated by the observed alteration in proliferation status following exposure to melatonin and its antagonist of luzindole, it has been verified that the antiproliferative effect of melatonin on endometriosis was achieved based on receptor‐independent mechanisms [17].

Based on the evidence of its receptor‐independent activity, we analyzed the potential targets and identified EGFR as the binding target of melatonin to regulate proliferation in endometriosis. EGFR is a tyrosine kinase receptor, and its activation affects numerous processes important to cancer development and progress [28]. Generally, EGFR signaling is activated through the binding of a ligand to the extracellular ligand binding domain, which initiates the autophosphorylation, resulting in the activation of receptors and further initiating a signaling cascade that drives on various cellular responses, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis [29]. Even EGFR signaling is crucial for normal cellular processes, it has been demonstrated that EGFR expression and activity are significantly higher in endometriosis [30, 31, 32]. This differential expression suggests that EGFR may play an important role in endometriosis, indicating endometriotic cells might be more sensitive to EGFR as a potential target for endometriosis. In addition, the immunoreactivity of p‐EGFR was determined higher endometriosis, especially in ovarian endometrioma and advanced‐stage endometriosis [32]. Our results showed melatonin can inhibit the activity of EGFR in endometriotic cell lines and mouse models. The optimal therapeutic windows where melatonin could preferentially affect hyperactive EGFR signaling in endometriotic cells without affecting normal healthy cells need to be researched further.

Melatonin's antiproliferative effects have been widely investigated [33]. It not only arrests the cell cycle but also regulates proliferation in normal and cancer cells. Melatonin has been shown to suppress the RNA expression of cyclin D1 among human breast cancer cells, as well as the RNA and protein expression levels of cyclin D1, cyclin B1, CDK1, and CDK4 among osteosarcoma cells [34, 35, 36]. In addition, melatonin has been demonstrated to impede the RNA expressions of cyclins and CDKs, thereby hindering the G1‐phase's progression in dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells in rats [37]. A crucial target of endometriosis therapy is to induce cell cycle arrest. Inhibition of cyclin D1 has been found to contribute to cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 stage and impede endometriosis development [17]. Consistent with that, melatonin decreased the growth of endometriotic cells by inducing G1 phase arrest in our study.

The PI3K/AKT pathway plays a pivotal role in both cellular proliferation as well as survival, especially in endometriosis [38, 39, 40]. Studies have demonstrated the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in endometriosis, which promotes the development of ectopic endometriotic lesions in mouse models [41]. Therefore, the exploration of the PI3K‐AKT pathway, particularly in terms of its involvement in cell cycle progression, represents a significant advancement in addressing the existing challenges associated with treating endometriosis [42]. Inversely, in our research, the level of PI3K was remarkably decreased after treatment of melatonin, which showed melatonin‐suppressed endometriosis development by inhibition of the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Melatonin treatment was demonstrated to suppress the growth of endometriotic lesions in mice and the proliferation of endometriotic cells in vitro in our study. The regulatory effect of melatonin was further validated to be mediated by its ability to bind to EGFR and reduce its phosphorylation level. Then, melatonin downregulated the activities of the signaling pathways of PI3K and CCND1, arresting the G1 phase to regulate the cell cycle and suppress the growth of endometriosis. Thus, it could be inferred that melatonin shows potential as a therapeutic drug against endometriosis. Although the mouse model has been widely validated in endometriosis research, key limitations such as anatomical differences that may affect disease progression, surgically induced rather than spontaneous endometriosis and incomplete replication of the complex inflammatory environment seen in human endometriosis still need to be considered. Thus, further preclinical studies on a large scale are required to take on endometriosis patients.

It's noteworthy that melatonin's mechanism, as revealed in this study, does not seem to induce significant side effects, at least in terms of animal body weight, which remained stable across the different treatments. This may be advantageous when considering the potential clinical application of melatonin, as it might present a more favorable side effect profile than current therapeutic options for endometriosis.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that melatonin has a significant inhibitory effect on endometriosis through the modulation of EGFR and PIK3CA pathways. These insights may pave the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for endometriosis.

Author Contributions

Yao Wang and Chi‐Chiu Wang concepted and designed experiments. Yiran Li, Sze‐Wan Hung, Xu Zheng, Yang Ding, Zhouyurong Tan, Ruizhe Zhang, Yuezhen Lin and Yi Song performed the experiments. Yiran Li and Sze‐Wan Hung analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. Tao Zhang, Yao Wang and Chi‐Chiu Wang reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved to publish this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the SSFCRS, CUHK, Hong Kong (Grant Nos.: 0670/22) and CMDF, Hong Kong (Grant Nos.: 23B2/034A_R1).

Contributor Information

Yao Wang, Email: yaowang1@cuhk.edu.hk.

Chi‐Chiu Wang, Email: ccwang@cuhk.edu.hk.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Zondervan K. T., Becker C. M., and Missmer S. A., “Endometriosis,” Longo D. L., ed. The New England Journal of Medicine 382, no. 13 (2020): 1244–1256, 10.1056/NEJMra1810764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bulun S. E., Yilmaz B. D., Sison C., et al., “Endometriosis,” Endocrine Reviews 40, no. 4 (2019): 1048–1079, 10.1210/er.2018-00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fuldeore M. J. and Soliman A. M., “Prevalence and Symptomatic Burden of Diagnosed Endometriosis in the United States: National Estimates From a Cross‐Sectional Survey of 59,411 Women,” Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 82, no. 5 (2017): 453–461, 10.1159/000452660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sampson J. A., “Peritoneal Endometriosis Due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue Into the Peritoneal Cavity,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 14, no. 4 (1927): 422–469, 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)30003-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nap A. W., “Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis,” in Endometriosis: Science and Practice, 1st ed. (2012): 42–53, 10.1002/9781444398519.ch5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vercellini P., Viganò P., Somigliana E., and Fedele L., “Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and Treatment,” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 10, no. 5 (2014): 261–275, 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaskivuo T., “Apoptosis and Apoptosis‐Related Proteins in Human Endometrium,” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 165, no. 1–2 (2000): 75–83, 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferrero S., Evangelisti G., and Barra F., “Current and Emerging Treatment Options for Endometriosis,” Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 19, no. 10 (2018): 1109–1125, 10.1080/14656566.2018.1494154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunselman G. A. J., Vermeulen N., Becker C., et al., “ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women With Endometriosis,” Human Reproduction 29, no. 3 (2014): 400–412, 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Genario R., Morello E., Bueno A. A., and Santos H. O., “The Usefulness of Melatonin in the Field of Obstetrics and Gynecology,” Pharmacological Research 147 (2019): 104337, 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardeland R., Cardinali D. P., Srinivasan V., Spence D. W., Brown G. M., and Pandi‐Perumal S. R., “Melatonin‐A Pleiotropic, Orchestrating Regulator Molecule,” Progress in Neurobiology 93, no. 3 (2011): 350–384, 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernando S., Wallace E. M., Vollenhoven B., et al., “Melatonin in Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Pilot Double‐Blind Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Clinical Trial,” Frontiers in Endocrinology 9, no. SEP (2018): 1–11, 10.3389/fendo.2018.00545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Espino J., Macedo M., Lozano G., et al., “Impact of Melatonin Supplementation in Women With Unexplained Infertility Undergoing Fertility Treatment,” Antioxidants 8, no. 9 (2019): 338, 10.3390/antiox8090338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cetinkaya Kocadal N., Attar R., Yildirim G., et al., “Melatonin Treatment Results in Regression of Endometriotic Lesions in an Ooferectomized Rat Endometriosis Model,” Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association 14, no. 2 (2013): 81–86, 10.5152/jtgga.2013.53179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Güney M., Oral B., Karahan N., and Mungan T., “Regression of Endometrial Explants in a Rat Model of Endometriosis Treated With Melatonin,” Fertility and Sterility 89, no. 4 (2008): 934–942, 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwertner A., Conceição Dos Santos C. C., Costa G. D., et al., “Efficacy of Melatonin in the Treatment of Endometriosis: A Phase Ii, Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Trial,” Pain 154, no. 6 (2013): 874–881, 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park S., Ham J., Yang C., et al., “Melatonin Inhibits Endometriosis Development by Disrupting Mitochondrial Function and Regulating tiRNAs,” Journal of Pineal Research 74, no. 1 (2023): 1–17, 10.1111/jpi.12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He Y., Liang B., Hung S. W., et al., “Re‐Evaluation of Mouse Models of Endometriosis for Pathological and Immunological Research,” Frontiers in Immunology 13 (2022): 1–12, 10.3389/fimmu.2022.986202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cetinkaya N., Attar R., Yildirim G., et al., “The Effects of Different Doses of Melatonin Treatment on Endometrial Implants in an Oophorectomized Rat Endometriosis Model,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 291, no. 3 (2015): 591–598, 10.1007/s00404-014-3466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yilmaz B., Kilic S., Aksakal O., et al., “Melatonin Causes Regression of Endometriotic Implants in Rats by Modulating Angiogenesis, Tissue Levels of Antioxidants and Matrix Metalloproteinases,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 292, no. 1 (2015): 209–216, 10.1007/s00404-014-3599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lanoix D., Ouellette R., and Vaillancourt C., “Expression of Melatoninergic Receptors in Human Placental Choriocarcinoma Cell Lines,” Human Reproduction 21, no. 8 (2006): 1981–1989, 10.1093/humrep/del120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chantalat E., Valera M. C., Vaysse C., et al., “Estrogen Receptors and Endometriosis,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 8 (2020): 2815, 10.3390/ijms21082815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Hardeland R., et al., “Melatonin: A Hormone, a Tissue Factor, an Autocoid, a Paracoid, and an Antioxidant Vitamin,” Journal of Pineal Research 34, no. 1 (2003): 75–78, 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Pilar Terron M., Flores L. J., and Koppisepi S., “Medical Implications of Melatonin: Receptor‐Mediated and Receptor‐Independent Actions,” Advances in medical sciences 52 (2007): 11–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reppert S. M., “Melatonin Receptors: Molecular Biology of a New Family of G Protein‐Coupled Receptors,” Journal of Biological Rhythms 12, no. 6 (1997): 528–531, 10.1177/074873049701200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang H., Pu Y., Luo L., Li Y., Zhang Y., and Cao Z., “Membrane Receptor‐Independent Inhibitory Effect of Melatonin on Androgen Production in Porcine Theca Cells,” Theriogenology 118 (2018): 63–71, 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zemła Agata, Grzegorek Irmina, Dzięgiel Piotr, and Jabłońska Karolina, “Melatonin Synergizes the Chemotherapeutic Effect of Cisplatin in Ovarian Cancer Cells Independently of MT1 Melatonin Receptors,” In Vivo 31, no. 5 (2018): 801–809, 10.21873/invivo.11133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cheng W. L., Feng P. H., Lee K. Y., et al., “The Role of Ereg/Egfr Pathway in Tumor Progression,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 23 (2021): 12828, 10.3390/ijms222312828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paul M. D. and Hristova K., “The RTK Interactome: Overview and Perspective on RTK Heterointeractions,” Chemical Reviews 119, no. 9 (2019): 5881–5921, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsieh Y. Y., Chang C. C., Tsai F. J., Lin C. C., and Tsai C. H., “T Homozygote and Allele of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2073 Gene Polymorphism Are Associated With Higher Susceptibility to Endometriosis and Leiomyomas,” Fertility and Sterility 83, no. 3 (2005): 796–799, 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ejskjær K., Sorensen B. S., Poulsen S. S., Mogensen O., Forman A., and Nexo E., “Expression of the Epidermal Growth Factor System in Eutopic Endometrium From Women With Endometriosis Differs From That in Endometrium From Healthy Women,” Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 67, no. 2 (2009): 118–126, 10.1159/000167798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhan H., Peng B., Ma J., et al., “Epidermal Growth Factor Promotes Stromal Cells Migration and Invasion via Up‐Regulation of Hyaluronate Synthase 2 and Hyaluronan in Endometriosis,” Fertility and Sterility 114, no. 4 (2020): 888–898, 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Favero G., Moretti E., Bonomini F., Reiter R. J., Rodella L. F., and Rezzani R., “Promising Antineoplastic Actions of Melatonin,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 9, no. OCT (2018): 1–13, 10.3389/fphar.2018.01086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dong C., Yuan L., Dai J., et al., “Melatonin Inhibits Mitogenic Cross‐Talk Between Retinoic Acid‐Related Orphan Receptor Alpha (RORα) and ERα in MCF‐7 Human Breast Cancer Cells,” Steroids 75, no. 12 (2010): 944–951, 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu L., Xu Y., and Reiter R. J., “Melatonin Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Osteosarcoma Cell Line Mg‐63,” Bone 55, no. 2 (2013): 432–438, 10.1016/j.bone.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu L., Xu Y., Reiter R. J., et al., “Inhibition of ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway Is Involved in Melatonin's Antiproliferative Effect on Human MG‐63 Osteosarcoma Cells,” Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 39, no. 6 (2016): 2297–2307, 10.1159/000447922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pizarro J. G., Yeste‐Velasco M., Esparza J. L., et al., “The Antiproliferative Activity of Melatonin in B65 Rat Dopaminergic Neuroblastoma Cells Is Related to the Downregulation of Cell Cycle‐Related Genes,” Journal of Pineal Research 45, no. 1 (2008): 8–16, 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu J. S. L. and Cui W., “Proliferation, Survival and Metabolism: The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signalling in Pluripotency and Cell Fate Determination,” Development 143, no. 17 (2016): 3050–3060, 10.1242/dev.137075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cinar O., Seval Y., Uz Y. H., et al., “Differential Regulation of Akt Phosphorylation in Endometriosis,” Reproductive BioMedicine Online 19, no. 6 (2009): 864–871, 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Samartzis E., Noske A., Dedes K., Fink D., and Imesch P., “ARID1A Mutations and PI3K/AKT Pathway Alterations in Endometriosis and Endometriosis‐Associated Ovarian Carcinomas,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 9 (2013): 18824–18849, 10.3390/ijms140918824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilson M. R., Holladay J., and Chandler R. L., “A Mouse Model of Endometriosis Mimicking the Natural Spread of Invasive Endometrium,” Human Reproduction 35, no. 1 (2020): 58–69, 10.1093/humrep/dez253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alfakeeh A. and Brezden‐Masley C., “Overcoming Endocrine Resistance in Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer,” Current Oncology 25 (2018): 18–27, 10.3747/co.25.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.