Abstract

The association of 55 dipeptides extracted from aggregation-prone regions of selected proteins was studied by means of multiplexed replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations with the coarse-grained UNRES model of polypeptide chains. Each simulation was carried out with 320 dipeptide molecules in a periodic box at 0.24 mol/dm3 concentration, in the 260–370 K temperature range. The temperature profiles of the degree of association, distributions of dipeptide cluster size, and structures of clusters were examined. It has been found that the dipeptides composed of strongly nonpolar (aromatic or aliphatic) residues associate nearly completely at all temperatures to form tight clusters, while those composed of charged or polar residues exhibited no or residual association. The dipeptides composed of nonpolar and small polar residues and those composed of less hydrophobic residues formed single clusters, gradually dissolving with increasing temperature, while those composed of phenylalanine or tryptophan and polar or charged residues formed multiple irregular clusters with room to accommodate water inside, suggesting the formation of liquid droplets or gels. The logarithms of the average degree of association and the free energy of aggregation per monomer were found to correlate with the dipeptide hydrophobicity.

Introduction

Phase separation of peptides,1 including their aggregation, is important in the design of new materials, including liquid bandages for wound healing.2,3 On the other hand, the association of the peptides formed as a result of the fragmentation of human body proteins, such as the Tau4 or Aβ peptides,5,6 can cause a variety of problems including nerve tissue devastation. Therefore, experimental and theoretical studies of peptide association and the character of the aggregates (oligomers, liquid droplets, gels, or fibrils) play an increasing role in materials and health sciences. Since aggregation is a long process involving many molecules, the use of coarse-grained representations of polypeptide chains in theoretical studies is desirable. Many such studies have been carried out recently, both with general-purpose or dedicated coarse-grained models.7−13

Minimal peptide sequences are the subject of extensive studies with regard to the design of nanomaterials, including those with biomedical application14,15 and hydrogels.16 Specifically, the phenylalanine dipeptide and its derivatives have received considerable attention and were found experimentally to form fibrils, nanotubes, and nanowires.17−19 Moreover, the Fmoc-FF dipeptide has been shown to form fibrils with an α-helical structure at low pH and with β-structure at higher pH values.20 The phenylalanine dipeptide has also been studied extensively by coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) with the Martini model.21−23 The study by Frederix et al.24 suggested the formation of a variety of structures, from spherical aggregates to small nanotubes. Tang et al.25 obtained prolate aggregates of the phenylalanine dipeptide, while Xiong et al.26 and, more recently, Wang et al.27 obtained tubular and vesicular structures.

In the study mentioned above, Frederix et al.24 also investigated the aggregation of all possible natural dipeptide sequences with Martini and defined the aggregation propensity (AP) score as the ratio of the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of the system in the initial energy-minimized configuration to that in the final configuration. In agreement with the experiment, these researchers found that the dipeptides composed of nonpolar aromatic residues are the most capable of association.

Recently, Tang et al.25 studied the aggregation properties, specifically the formation of liquid droplets (liquid–liquid phase separation; LLPS) and solid aggregates (liquid–solid phase separation; LSPS), of all 400 natural dipeptide sequences by coarse-grained canonical MD simulations with the Martini force field with explicit coarse-grained water.21−23 Depending on hydrophobicities and side-chain shapes, they observed solid aggregates, solutions, or aggregates of the liquid droplet structure with high fluidity (quantified in terms of the exchange of dipeptide molecules between the aggregate and water phase). For four dipeptides, QW, WW, GF, and VI, these researchers carried out turbidity measurements at a range of temperatures from 5 to 55 °C. For the WW dipeptide, aggregation persisted until higher temperatures, which is indicative of fibril formation. This finding was confirmed by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.25 For the QW dipeptide, the temperature dependence of turbidity was characteristic of liquid droplet formation. Additional MD simulations carried out at a range of temperatures for QW showed that the aggregation of this dipeptide diminished at a higher temperature, which is indicative of the formation of liquid droplets. No aggregation was detected for the GF and VI dipeptides. Consistent with the results of turbidity measurements, little association was observed in the simulations for the VI dipeptide. However, the association was quite substantial for the GF dipeptide, which contrasted with the experimental results. The authors have proposed a method for the prediction of LLPS properties, based on the clustering and collapse degree determined from coarse-grained simulations.

In our earlier work,28 we applied the highly coarse-grained UNRES model of polypeptide chains developed in our laboratory,29,30 with two interaction sites per amino acid residue and implicit solvent treatment, to study the aggregation of oligopeptides derived from human cystatin, Tau protein, and prion sequences, as well as of those containing the RADA sequence repeats, which were designed as gelating materials. The peptides studied contained from 6 to 32 amino acid residues. Despite the relatively modest size of the simulated systems (8 molecules in a periodic box), UNRES was able to predict peptide aggregation consistent with the experiment.28 Earlier, UNRES was used with success to simulate, among others, the aggregation of Aβ and Tau peptides.31−34

Tang et al.25 noted that highly reduced protein models without an explicit solvent were unable to predict the association of dipeptides, even those composed of strongly hydrophobic amino acid residues. We thought that it is therefore worthwhile to test the ability of UNRES to model dipeptide association. Owing to careful derivation to embed atomistic details in the effective energy function by means of the scale-consistent theory of coarse graining,29,30 UNRES captures side chain anisotropy and also handles the formation of regular backbone hydrogen-bonded structures very well.29,35,36 Moreover, owing to the high degree of coarse graining and implicit solvent representation, it enables us to explore the configurational space of the systems studied extensively. Finally, a high degree of coarse graining in UNRES combined with its tight connection to the physics of interactions could enable us to identify the key factors responsible for aggregation easier compared to using more detailed peptide models.

In this work we studied, by means of coarse-grained simulations with UNRES, the association of 55 dipeptides extracted from the sequences of proteins that are known to phase-separate, namely, UBAP2L (Uniprot: Q14157), WTAP (Uniprot: Q15007), DDX4 (Uniprot: Q9NQI0), and elastin (Uniprot: P15502). The dipeptides studied are also the building blocks of larger peptides, which are now under investigation in our laboratory. The dipeptide sequences considered are collected in Table 1. We used the multiplexed replica-exchange molecular dynamics (MREMD),37,38 which is a very efficient method to generate Boltzmann ensembles at a range of temperatures and enables us to extensively explore their configurational space. On the other hand, it cannot be used, in a direct manner, to simulate the dynamics-related properties (e.g., diffusion and fluidity). We have found that the dipeptides composed of strongly hydrophobic residues form solid aggregates, while those composed of hydrophilic residues remain separated. The behavior of amphiphilic dipeptides has been found to depend on composition, ranging from solid aggregates through small clusters to a separated state.

Table 1. Dipeptides Considered in This Study.

| nonpolar dipeptides (8 sequences) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FF | FV | LL | VI | WW | YF | YV | YY | |||||

| polar and charged dipeptides (2 sequences) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | KE | |||||||||||

| amphipolar dipeptides (27 sequences)a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GF | GY | NW | PW | QW | SW | TW | |||||

| FG | FN | FP | FQ | FS | FT | LG | LN | LP | LQ | LS | LT |

| WG | WQ | YG | YN | YP | YQ | YS | YT | ||||

| dipeptides with nonpolar and charged residues (18 sequences) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | DW | DY | EW | FE | KF | KW | KY | RF | RW | WK | YE | YR |

| LD | LE | LH | LK | LR | ||||||||

Proline is listed as a polar residue, since it occurs mainly on the protein surface.

Methods

UNRES Model of Polypeptide Chains and Simulation Procedure

As mentioned in the Introduction, we used the UNRES model of polypeptide chains39,40 to carry out coarse-grained simulations. In UNRES, a polypeptide chain is represented as a sequence of α-carbon (Cα) atoms, with united side chains attached by virtual bonds to the respective Cα atoms and the united peptide groups located in the middle between the consecutive Cα atoms. Only the united peptide groups and united side chains are interaction sites, with the Cαs serving to define the backbone geometry. The solvent is treated in an implicit manner, and the solvent-mediated interactions are present mostly in the side chain–side chain interaction potentials.

The UNRES effective energy function stems from the potential of mean force (PMF) of polypeptide chains in water, in which the degrees of freedom implicit in the model, including the solvent degrees of freedom, are integrated out.29,30,36 The PMF is further expanded into the Kubo cluster-cumulant functions.41 These are, in turn, converted into force field terms by means of the scale-consistent theory of coarse graining developed in our laboratory, which enables us to embed, in an implicit manner, the atomistic details in the effective energy function.29,30 Owing to this feature, the effective interaction potentials have the axial and not the spherical symmetry and multibody terms appear, which are necessary to model the secondary structure correctly.36,42 Consequently, UNRES is able to predict protein structures40,43 and aggregation28,32 in the ab initio mode despite the high degree of coarse graining. Moreover, as originating from the potential of mean force, the UNRES effective energy function depends on temperature, this feature enabling correct reproduction of thermal profiles of average energy, heat capacity, and ensemble-averaged properties, e.g., end-to-end distance.44 However, the temperature dependence does not extend to the side chain–side chain interaction potentials, although the respective attempts were made in the past.45,46

The side chain–side chain interaction potentials in UNRES are mean-field potentials that encompass all interactions between side-chain atoms and the interactions with the solvent, which are implicit in UNRES. Consequently, the Coulombic interactions between charged side chains are contained in the respective mean-field potentials, and no explicit charges are present. A similar approach is used, e.g., in the lattice models in which the charge–charge interactions are taken into account by using appropriate contact energy values.8 The side chain–side chain potentials have been parametrized47 to correspond to physiological pH.

In this work, we used the latest NEWCT-9P variant of the UNRES force field calibrated with the experimental ensembles [determined by means of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy], which included both folded and unfolded structures, of 9 proteins with different secondary structure classes.48 Details of UNRES can be found in the references cited.29,36,39,40,48

In all calculations, the parallelized UNRES program was used,49 which has recently been heavily upgraded and optimized.40

For each dipeptide system, MREMD simulations were carried out for 320 chains in a cubic periodic box with a 130 Å side, with this corresponding to 0.24 mol/dm3 concentration. Peptide concentration was the same as in the work by Tang et al.,25 in which 720 dipeptide molecules were placed in a 170 Å-side periodic water box. The simulations were carried out at constant volume, and the temperature was controlled by means of the Langevin thermostat with water friction scaled down by the factor of 0.02. The UNRES implementation of Langevin MD developed in our earlier work was used,50,51 with further extension to MREMD38 and its adaptation to the temperature-dependent force field.44 Replicas were run at 12 temperatures equal to 260, 272, 279, 284, 288, 291, 294, 298, 308, 322, 341, and 370 K, which were determined by using the Hansmann algorithm52 to provide the maximum number of walks in the temperature space. Four replicas were run at each temperature, giving a total of 48 replicas per system. Each trajectory was started from dipeptide molecules randomly placed in the box, subject to the condition of nonoverlap. The number of MD steps of each trajectory ranged from 20 000 000 to 100 000 000 with the step size of 9.78 fs, with these settings amounting to about 0.2–1.0 μs. However, because the UNRES time scale is about 1000-fold more extended than the all-atom or laboratory time scale, due to averaging out fast-moving degrees of freedom,51,53 a millisecond time scale was covered in our simulations.

Each simulation was run until it converged. The convergence was checked by monitoring the temperature profiles of the average association degree, α(T) (eq 4 of the “Analysis of Simulation Results” section), averaged over the consecutive 5 000 000-step (500-snapshot) windows, taking every eighth snapshot from the respective trajectory window (a total of 3000 snapshots per window, for all 48 trajectories). For each system, the standard deviations of α (σα) at the subsequent simulation windows (except for the last one) between the consecutive windows were calculated and plotted in the window index. For the window with index i, σαi is defined by eq 1

| 1 |

where Tmin = 260 K and Tmax = 370 K are the minimum and the maximum replica temperatures, respectively, and i is the window index. The integration is carried out numerically.

A simulation was considered to be converged if σα stopped to decrease. A sample plot is of σα vs window index is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plot of the standard deviation of the average association degree (σα) between the consecutive 500-snapshot simulation windows for the FF system. The graph was drawn with gnuplot.54

Analysis of Simulation Results

After the convergence was achieved, the last 1000 snapshots from each trajectory with the sampling frequency of 8 (a total of 6000 snapshots) were taken for further analysis, which was carried out by using the UNRES implementation44 of the binless weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM).55 The WHAM enabled us to compute the temperature profiles of the ensemble-averaged quantities and to determine the conformational ensembles at selected temperatures. The conformational ensembles were dissected into five clusters by means of Ward’s minimum-variance method.56 The clusters were ranked by the cumulative probabilities of the constituent conformations, as described in our earlier work.44 The structure closest to the mean structure of the respective cluster was selected as a representative of the entire cluster. Selected structures were converted to the all-atom structures by using the cg2all algorithm,57,58 followed by refinement with AMBER59 with the ff19SB force field60 and implicit-solvent generalized Born surface area (GBSA) model,61,62 as described in our earlier work.63

For the analysis of the dependence of peptide association on temperature, we used the fractions of dipeptide molecules in clusters with size m, fm (where f1 is the fraction of monomeric dipeptide molecules), the average cluster size, m, and the average degree of association, α. These quantities are defined by eqs 2–4, respectively.

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

with

| 5 |

| 6 |

where fmi is the fraction of dipeptide molecules in clusters with size m at snapshot i, mi is the average cluster size at snapshot i, nmi is the number of clusters with size m at snapshot i, nci is the total number of clusters at snapshot i, np = 320 is the total number of dipeptide molecules in the simulation box, wi(T) is the weight of snapshot i for temperature T calculated with WHAM,44,55 and N is the number of snapshots in the batch. For each temperature, the conformational weights are normalized to 1 (eq 7).

| 7 |

To gain insights into the association thermodynamics, we calculated the free energies of cluster formation. The free energy of the formation of a cluster with size m, ΔFm, from monomers is defined by eq 8. Because the temperature dependence of the side chain–side chain interaction potentials is not included in UNRES and the expressions for the energy and entropy of the system contain the explicit derivative of the effective UNRES energy function (which has the physical sense of a potential of mean force) in temperature,44 we did not compute and analyze the energies and entropies. To avoid the dependence on cluster size, we subsequently computed the free energies of cluster formation per monomer, ΔF̂m, from eq 9.

| 8 |

| 9 |

where fm is the fraction of the oligomers with size m calculated from the results of simulations using eq 2. We noticed that F̂m becomes nearly constant with increasing oligomer size very quickly; a sample plot is shown in Figure 2. Therefore, we defined the free energy of aggregation per monomer, ΔF̂aggr, as the average of ΔF̂m over the last n largest clusters, where n = 5 for moderately and weakly aggregating dipeptides or less for strongly associating peptides, for which only the monomers and aggregates with n < 5 which comprise almost all molecules are present (eq 10).

| 10 |

where mmax is the maximum cluster size for the dipeptide system under consideration. It should be noted that we could not determine ΔF̂aggr for the WG dipeptide system, which exhibited very strong association in our simulations, except for high temperatures, because the fraction of monomers (f1) was effectively 0.

Figure 2.

Plot of the dependence of the aggregation free energy per monomer (eq 10) for the YY dipeptide system at T = 280, 300, and 320 K on cluster size. The graph was drawn with gnuplot.54

The clusters were identified and the dipeptide molecules were assigned to the subsequent clusters by using the procedure described in our earlier work.28 Briefly, for a given snapshot, pairs of dipeptide molecules were searched in the numerical order of molecules’ indices, for which at least one pair of side chains of different molecules was in contact, as determined by the contact function introduced in our earlier work (eq 8 of ref (64)). Once the first pair had been found, the other molecules whose side chains were in contact with at least one of the molecules of the pair were searched and added to the first cluster. Each molecule already present in the cluster was marked in order not to be considered in further searches. Subsequently, the cluster was expanded by adding the next molecules to the cluster in contact with at least one molecule of the cluster. When no further dipeptide molecules were found in contact with any molecule of the cluster, the search for the first cluster was concluded, and a new search was started to build the next cluster, with the remaining molecules that had not been marked as already belonging to a cluster. The procedure ended when the list of molecules had been exhausted. If no molecules were found close to a given molecule, that molecule alone formed a cluster of size 1.

Results

Dependence of Dipeptide Association on Temperature

We begin with the analysis of the dependence of the fraction of dipeptide clusters (eq 2) on the cluster size and temperature. The respective heat maps of the selected representative systems LL (nonpolar and nonpolar), SS (polar and polar), LK (nonpolar and charged), LN (nonpolar and polar), LS (nonpolar and small polar), and FN (aromatic nonpolar and polar) are shown in Figure 3A–F, respectively. The heat maps of all systems are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. It should be noted that because the solvent is implicit in UNRES and the potentials of side chain–side chain interactions do not depend on temperature,47 the association of nonpolar dipeptides, which is mainly of the hydrophobic type, may be exaggerated at low temperatures. Specifically, in contrast to explicit-solvent simulations with the Martini model reported by Tang et al.,25 we do not observe the decrease of the association degree at low temperatures.

Figure 3.

Heat maps of the fractions of dipeptide clusters plotted in temperature and association degree for the LL (A), SS (B), LK (C), LN (D), LS (E), and FN (F) dipeptide systems obtained from MREMD simulations with 320 dipeptide molecules at the concentration of 0.24 mol/dm3. The decimal logarithm color scale of the fraction of clusters of a given association degree is shown on the right of each panel. The graphs were drawn with gnuplot.54

As shown in Figure 3A, the LL dipeptide is almost completely associated until T > 310 K; at high temperatures, some monomers and small oligomers detach from the cluster. It is remarkable that the cluster did not split into smaller parts. The SS system, on the other hand, exhibits no remarkable association over the entire temperature range (Figure 3B). When leucine is combined with the charged lysine residue (Figure 3C) or with the polar glutamine residue (Figure 3D), some association occurs at low temperatures, with the cluster size and populations decreasing quickly with increasing temperature.

The association degree heat map of the LS–dipeptide system (Figure 3E) is different from that described above. Its characteristic feature is a curved ravine starting at low temperatures, with the association degree of around 0.8 and going down to T = 290 K and association degree of 0.2, then gradually extending to the whole temperature range at a lower association degree. It can be noted that the region on the right to the ravine corresponds to a small association degree, which decreases steadily with increasing temperature. The monomers are dominant in this region. Thus, it resembles the characteristics of the LN and LK dipeptides and other dipeptides composed of nonpolar and strongly polar or charged residues. Conversely, the low-temperature region resembles the characteristics of nonpolar pairs, with a high degree of association (large clusters) dominating, from which only monomers and small oligomers detach. The maximum association degree decreases as the temperature increases; however, the separation of the high- and low-association regions indicates that it corresponds to the detachment of monomers and small oligomers from a cluster and not to splitting of the cluster into smaller parts. In other words, the cluster becomes gradually dissolved as the temperature increases. Starting from about T = 290 K, the separation between small- and large-size dipeptide clusters becomes gradually smaller until about T = 300 K where the cluster becomes completely dissolved and only small oligomers remain. The cluster-dissolution process is illustrated in Figure 4, in which the distributions and cumulative distributions of the cluster size at T = 270, 290, and 310 K are shown. The cluster size distributions and cumulative distributions for all systems are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. It could also be noted that the ravine separating the high–low-association degree regions would probably occur for all systems, if the temperature range was sufficiently broad. However, the temperature range is constrained to that in which water forms a liquid phase.

Figure 4.

Distributions and cumulative distributions of dipeptide clusters with various sizes at T = 270 K (A), T = 290 K (B) and T = 310 K (C) for the LS–dipeptide system. The graphs were drawn with gnuplot.54

The FN system exhibits different behaviors. The diagram resembles the right part of that of LS; however, the association degree at T = 280 K ranges from 0 to 0.7 and reaches 0.3 even at T = 300 K. Inspection of the distributions and cumulative distributions at selected temperatures shown in Figure 5 confirms the broad spread of the association degree and sample system structures indicate many small- and moderate-size clusters, which are close to each other.

Figure 5.

Distributions and cumulative distributions of dipeptide clusters with various sizes at T = 270 K (A), T = 290 K (B) and T = 310 K (C) for the FN–dipeptide system. The graphs were drawn with gnuplot.54

As can be seen from the panels of Figure S1 of the Supporting Information, the other systems copy one of the four characteristics. The dipeptides composed of nonpolar residues exhibit the strongly associated behavior of the LL system at all temperatures (Figure 3A). The dipeptides composed of a charged, polar, or nonpolar (except for phenylalanine and tryptophan) and a charged or strongly polar residue exhibit no or little association at all temperatures, as the SS, LK, and LN dipeptides do (Figure 3B–D). The dipeptides composed of a nonpolar and a weakly polar or a small residue (G, S, T, or P) and the YY dipeptide exhibit the behavior of the LS system (Figure 3E), with a ravine region in the temperature–association degree heat map separating the regions of strong and no association. Finally, the dipeptides containing phenylalanine and, to a smaller extent, tryptophan and a charged or strongly polar residue form clusters with various sizes, similar to those in the FN system (Figure 3F).

Dependence of Association Propensity on Hydrophobicity

A color map of the decimal logarithm of the average association degree α (eq 4) at T = 300 K is shown in Figure 6. The amino acid residues are arranged in the order proposed by Miyazawa and Jernigan,65 which basically corresponds to decreasing hydrophobicity except that proline is placed at the end of the list. For the sake of completeness, the amino acid residues not considered in this study are also indicated in the axes of the diagram. As shown, all dipeptides composed of hydrophobic residues considered in this study except for those containing tyrosine (which is moderately hydrophobic) possess a high association propensity. Conversely, those containing charged or polar residues possess reduced association propensity. The aggregation free energies per monomer, ΔF̂aggr (eq 10), shown in Figure 7, and the numerical values collected in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information exhibit qualitatively the same dependence on dipeptide composition.

Figure 6.

Color map of the decimal logarithm of the average association degree α (eq 4) at T = 300 K. Each dipeptide is represented as a square, with the abscissa and ordinate corresponding to the N- and the C-terminus, respectively. The color scale is on the right of the map. The graph was drawn with gnuplot.54

Figure 7.

Color map of the aggregation free energy per monomer, ΔF̂aggr, at T = 300 K. Each dipeptide is represented as a square, with the abscissa and ordinate corresponding to the N- and the C-terminus, respectively. The color scale (in kcal/mol) is on the right of the map. The graphs was drawn with gnuplot.54

The dependence of the average association degree on residue hydrophobicity is shown more quantitatively in Figure 8, where the decimal logarithm of the average association degree is plotted vs the sum of hydrophobicities, defined as the free energies of transfer from the water to the n-octanol phase calculated from the water–n-octanol partition coefficients of amino acids, as determined by Fauchère and Pliška.66 It can be seen that the dependence has a sigmoidal character. The dipeptides with a strongly negative hydrophobicity sum are almost completely associated. Additionally, the GF and WG pairs also exhibit a high association degree. The reason for this is probably the small size of glycine, which leaves room for strong phenylalanine–phenylalanine interactions. On the other hand, the FG dipeptide does not associate so strongly. The difference in the association propensity of the two sequences can be attributed to differences in local geometry.

Figure 8.

Plot of the decimal logarithm of the average association degree α (eq 4) vs the sum of hydrophobicities defined based on the work of Fauchére and Pliška66 of the dipeptides studied in this work at T = 300 K. The line is the fitted sigmoid curve.

The dipeptides with a less negative or a positive hydrophobicity sum exhibit only residual association, while those with an intermediate hydrophobicity sum are on the slope of the sigmoid, exhibiting correlation between hydrophobicity sum and the logarithm of the association degree.

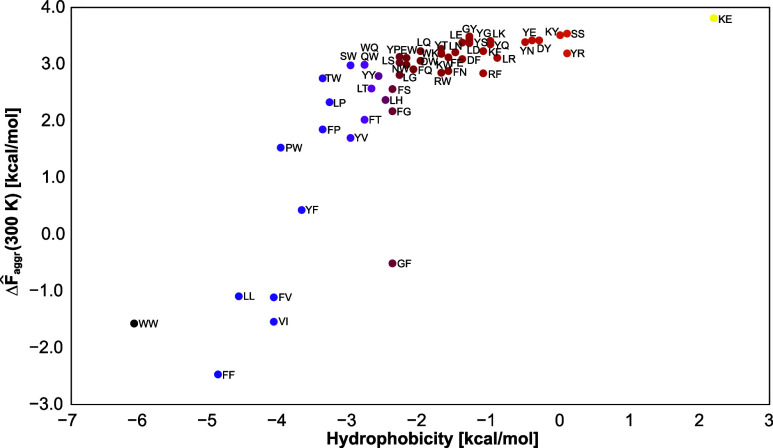

The aggregation free energies per monomer are also correlated to the sums of hydrophobicities, as shown in Figure 9. However, in contrast to the dependence of the decimal logarithm of the average association degree on hydrophobicity (Figure 8), a sharp increase in the negative hydrophobicity section is observed, while the aggregation free energy per monomer grows more slowly with hydrophobicity, starting from a hydrophobicity sum of about −3.

Figure 9.

Plot of the aggregation free energy per monomer, ΔF̂aggr (eq 10), vs the sum of hydrophobicities defined based on the work of Fauchére and Pliška66 of the dipeptides studied in this work at T = 300 K.

A correlation of the aggregation rate and hydrophobicity was found in the experimental study of the dependence of the aggregation of human muscle acylphosphatase (AcP) on mutation by Chiti et al.,67 and an exponential dependence of the fibril formation time (with negative coefficients at the exponents) on the contact energies of hydrophobic-type residues was found in the Monte Carlo simulation study by Li et al.8 of octapeptide aggregation using an on-lattice model. While our study concerns ensembles at equilibrium and not kinetics, which cannot be directly determined based on MREMD simulations, it can be assumed that the aggregation rates are related to the free energies of aggregation. Therefore, the results of these two studies conform with those of ours regarding the dependence of the aggregation propensity on hydrophobicity.

Structures of Dipeptide Clusters

Representative structures of the ensembles of the dipeptides studied in coarse-grained representation (obtained by processing the results of MREMD simulations with WHAM and clustering, as described in the “Analysis of Simulation Results” section) are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information, while those of the systems discussed in detail in this section are shown in Figures 10–12.

Figure 10.

Sample structures of the hydrophobic aggregates, after converting the coarse-grained structures to all-atom structures, of the LL (A), FF (B), and WW (C) dipeptide systems at T = 290 K obtained in UNRES/MREMD simulations. The structures were drawn with PyMol.68

Figure 12.

Sample structure of the FN–dipeptide system, after converting the coarse-grained structures to all-atom structures, at T = 290 K (A) and stereoview of a close-up of one of the clusters (B). The structures were drawn with PyMol.68

The dipeptides composed of hydrophobic residues form tight clusters with a nearly spherical shape except for those containing tryptophan, which exhibits a substantial anisotropy, reflecting the high anisotropy of tryptophan side chains. Sample aggregate structures (after conversion to the all-atom representation) for the LL, FF, and WW dipeptides are shown in Figure 10A–C. The association is of the hydrophobic type and the peptide groups do not form strong hydrogen bonds, due to the lack of space available after making favorable side chain–side chain contacts. Compared to the results obtained by Tang et al. with the Martini force field,25 the aggregates containing the dipeptides with aromatic side chains exhibit a less pronounced anisotropy, which could be caused by the differences in the coarse-grained models and by a greater number of dipeptide molecules in the calculations reported in ref (25) (720 vs 320).

As discussed in the “Dependence of Dipeptide Association on Temperature” section, many dipeptides, including those composed of polar and small nonpolar residues, are characterized by a ravine in the temperature–association degree heat maps, indicating a gradual dissolution of the aggregate as temperature increases. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 11A–C for the LS dipeptide at T = 270, 290, and 300 K, respectively. Compared to the nonpolar dipeptides, the clusters are less tight; however, they gradually dissolve by losing monomers and small oligomers instead of breaking into parts. For the LS dipeptide, the clusters maintain a nearly spherical shape. Consequently, such dipeptides can be considered to be capable of forming liquid droplets. When tryptophan is combined with a small polar residue, the clusters are flat and not spherical, as illustrated for the TW dipeptide system (Figure 11D).

Figure 11.

Sample structures of the LS dipeptide system, after converting the coarse-grained structures to all-atom structures, at T = 270 K (A), T = 290 K (B), and T = 300 K (C) and of the TW dipeptide system at T = 270 K (D). Periodic box boundaries are shown. The structures were drawn with PyMol.68

As shown in the “Dependence of Dipeptide Association on Temperature” section, the dipeptides composed of strongly nonpolar and larger charged or hydrophilic residues exhibit a continuity of clusters with various sizes. As an example, the structure of the FN system at T = 290 K is shown in Figure 12. It can be seen from the figure that the clusters have irregular shapes and are thin to enable the exposure of the polar asparagine side chain to water. There also is a quite substantial empty space between the dipeptide molecules, enabling penetration of the clusters by water. This feature of the clusters is exposed in panel B of Figure 12, in which a stereoview of a close-up of one of the clusters is shown. It can also be noted that the clusters are close to each other. Consequently, the system is likely to form liquid droplets or gels over a range of temperatures.

Discussion

We examined, by means of MREMD simulations with the physics-based coarse-grained UNRES model,39,40 the phase separation in 55 selected dipeptides composed of residues with varying sizes and polarities. As opposed to previous studies24,25 which were carried out by using canonical simulations at a given temperature, the use of MREMD enabled us to obtain the temperature dependence of the formation of peptide clusters without the need of doing additional simulations for selected systems. The calculations were carried out assuming a relatively high dipeptide concentration of 0.24 mol/dm3, as in the earlier work by Tang et al.25 The association of the strongly hydrophobic dipeptides was found to be almost independent of temperature, while those composed of polar or charged residues as well as those of weakly polar and nonpolar or charged residues exhibited little or no association. Strong, temperature-independent association was also exhibited by the WG and GF dipeptides. This result suggests that shape compatibility also contributes to the association. The use of an implicit solvent and temperature-independent side chain–side chain interaction potentials did not enable us to capture the decrease of hydrophobic association at low temperatures.

For most of the systems studied, the dependencies of dipeptide association propensity and cluster size on the residue character agree with those obtained by Tang et al. by using canonical coarse-grained MD simulations with the Martini force field.25 However, KE was found to form only small oligomers in our simulations (Figure S1), while it was found to form loose aggregates in those with Martini.25 On the other hand, judging from the respective panel in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information of ref (25), the EK dipeptide was predicted not to form larger clusters. There are no solubility data of the KE dipeptide, but EK is referred to as sparingly soluble in water.69 The dipeptides composed of nonpolar aliphatic residues were predicted not to associate in the simulations with Martini,25 while the LL and VI dipeptides were found to associate strongly in our simulations. The H-Leu-Leu-OH compound is referred to as lightly soluble in water.70 Moreover, heterochiral l-Leu-d-Ala, l-Leu-d-Ala, l-Leu-d-Ile, and l-Leu-d-Leu dipeptides were found to form fibrils in buffered aqueous solutions at neutral pH and in water–acetonitrile mixtures.71 Even though alternate chirality might result in tighter side-chain packing, these data suggest that the LL dipeptide could associate. On the other hand, Tang et al. have found by turbidity measurements that VI does not associate.25 It should be noted, however, that the dipeptide concentration in their turbidity measurements was much smaller (0.0015 or 0.003 mol/dm3) than in simulations (0.24 mol/dm3).

The degree of association of the dipeptides with intermediate summary hydrophobicity depended on temperature and correlated well with the sum of the free energies of transfer of amino acids from water to n-octanol determined by Fauchére and Pliška66 (Figure 8). The aggregation free energies (eq 10) also exhibited a good correlation with the sum of the free energy of transfer, with a remarkably steeper slope for strongly hydrophobic dipeptides (Figure 9). The obtained propensities to association agree with the available experimental data,17−19,25,72−75 in particular with those pertaining to the FF dipeptide, which has been studied extensively because of its role in designing peptide-based materials.17−19

For most of the strongly associating dipeptides, isotropic aggregates were obtained, while for those containing the tryptophan residues, prolate aggregates were obtained. This result reflects the pronounced anisotropy of the tryptophan side chain. Specifically, we obtained nearly isotropic aggregates for the phenylalanine dipeptide, which is known to form fibrils, nanotubes, and nanowires.17−19 Such structures were obtained in a number of simulation studies with the Martini force field,24,26,27 in which, however, up to 10 000 dipeptide molecules were simulated. Therefore, the differences of the shape of the FF dipeptide aggregates obtained in our study and in other coarse-grained studies are probably due, in part, to the different sizes of the system. This observation is supported by the fact that only slightly prolate FF aggregates were obtained in the study by Tang et al.,25 in which 720 molecules were simulated. On the other hand, it has been shown that the shape of FF aggregates strongly depends on the force field variant even if the Martini force field is used.76

Moderately associating dipeptides formed mostly isotropic clusters (except for those containing tryptophan, which formed flat clusters), gradually dissolving with increasing temperature by abstraction of monomers and small oligomers but not by breaking into smaller clusters. Those dipeptides were composed either of moderately hydrophobic amino acid residues (such as tyrosine) or of strongly hydrophobic residues and small polar residues. Due to small cluster sizes, it can be expected that such dipeptides can associate into liquid droplets. On the other hand, the dipeptides composed of phenylalanine and larger polar or charged residues (e.g., FN, FQ, and RF) formed irregular thin clusters with various sizes, which are close to each other and contain empty space inside to accommodate water, suggesting the formation of liquid droplets or gels.

Conclusions

The results of our study strongly suggest that dipeptide hydrophobicity is the primary factor responsible for their association propensity (Figure 8). This dependence was found stronger in our simulations than in those by Tang et al.25 with the Martini force field21−23 because strong association of dipeptides with both aliphatic side chains was observed in our study but not in the former. We have found that shape compatibility plays some role, as can be seen from unusually strong predicted association propensities of the dipeptides composed of phenylalanine or tryptophan and small residues (glycine, threonine, or serine), although this factor has not been found as important as in the earlier coarse-grained simulations by Tang et al.25

The obtained results have demonstrated that the highly coarse-grained UNRES model is able to reproduce the essential features of the association of dipeptides, even though it was designed and parametrized to simulate protein folding, in which the formation of a regular secondary structure through backbone hydrogen-bonding interactions coupled with backbone local conformational states states29,30,42,77,78 is certainly more important than in dipeptide association. On the other hand, the present UNRES does not capture the weakening of hydrophobic association at low temperatures and seems to underestimate the anisotropy of dipeptide clusters. We are now working on improving UNRES by introducing an explicit coarse-grained solvent in UNRES on the one hand and temperature dependence of side chain–side chain interactions of the implicit solvent UNRES on the other hand (as attempted in our earlier work45,46) and by introducing a finer representation of aromatic side chains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Centre under grant UMO-2021/40/Q/ST4/00035 (to ML and AL) and by the Natural Science Foundation of China (22161132013) to Chun Tang. Computational resources were provided by (a) the Centre of Informatics, Tricity Academic Supercomputer & Network (CI TASK) in Gdańsk, (b) the Interdisciplinary Center of Mathematical and Computer Modeling (ICM), University of Warsaw, under grant no. GA71-23, and (c) our 796-processor Beowulf cluster at the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Gdańsk.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c06305.

Heat maps of the fractions of dipeptide clusters plotted in temperature and the association degree for all 55 dipeptide systems; most probable structures of the systems; maximum cluster sizes and aggregation free energies per monomer at T = 300 K along with standard deviations; and sums of dipeptide hydrophobicities (PDF)

Contents of the zip archive (TXT)

Input data for MREMD calculations; fractions of the monomer and subsequent aggregates at all temperatures of the MREMD temperature range; and PDB files with representative structures of the systems studied (ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yuan C.; Li Q.; Xing R.; Li J.; Yan X. Peptide self-assembly through liquid-liquid phase separation. Chem 2023, 9, 2425–2445. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han C.; Zhang Z.; Sun J.; Li K.; Li Y.; Ren C.; Meng Q.; Yang J. Self-assembling peptide-based hydrogels in angiogenesis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 10257–10269. 10.2147/IJN.S277046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzyńska M.; Sawicka J.; Deptuła M.; Sosnowski P.; Sass P.; Peplińska B.; Pietralik-Molińska Z.; Fularczyk M.; Kasprzykowski F.; Zieliński J.; et al. Release systems based on self-assembling RADA16-I hydrogels with a signal sequence which improves wound healing processes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6273 10.1038/s41598-023-33464-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goux W. J.; Kopplin L.; Nguyen A. D.; Leak K.; Rutkofsky M.; Shanmuganandam V. D.; Sharma D.; Inouye H.; Kirschner D. A. The formation of straight and twisted filaments from short tau peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26868–26875. 10.1074/jbc.M402379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M.; Spillantini M. G.; Jakes R.; Rutherford D.; Crowther R. A. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 1989, 3, 519–526. 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.-P.; Arai T.; Miklossy J.; McGeer P. L. Aβ and tau form soluble complexes that may promote self aggregation of both into the insoluble forms observed in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 1953–1958. 10.1073/pnas.0509386103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereau T.; Deserno M. Generic coarse-grained model for protein folding and aggregation. Biophys. J. 2009, 96 (3), 405a. 10.1063/1.3152842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. S.; Co N. T.; Reddy G.; Hu C.-K.; Straub J. E.; Thirumalai D. Factors governing fibrillogenesis of polypeptide chains revealed by lattice models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 218101 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.218101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.; Shea J. E. Coarse-grained models for protein aggregation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 209–220. 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szała B.; Molski A. Chiral structure fluctuations predicted by a coarse-grained model of peptide aggregation. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 5071–5080. 10.1039/D0SM00090F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie I. M.; Caflisch A. Simulation studies of amyloidogenic polypeptides and their aggregates. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6956–6993. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mioduszewski Ł.; Bednarz J.; Chwastyk M.; Cieplak M. Contact-based molecular dynamics of structured and disordered proteins in a coarse-grained model: Fixed contacts, switchable contacts and those described by pseudo-improper-dihedral angles. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2023, 284, 108611 10.1016/j.cpc.2022.108611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatafta H.; Khaled M.; Kav B.; Olubiyi O. O.; Strodel B. A brief history of amyloid aggregation simulations. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2024, 14 (1), e1703 10.1002/wcms.1703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chibh S.; Mishra J.; Kour A.; Chauhan V. S.; Panda J. J. Recent advances in the fabrication and bio-medical applications of self-assembled dipeptide nanostructures. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 139–163. 10.2217/nnm-2020-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acet Ö.; Shcharbin D.; Zhogla V.; Kirsanov P.; Halets-Bui I.; Acet B. O.; Gök T.; Bryszewska M.; Odabaşı M. Dipeptide nanostructures: Synthesis, interactions, advantages and biomedical applications. Colloids Surf., B 2023, 222, 113031 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.113031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S.; Das S.; Nandi A. K. A review on recent advances in polymer and peptide hydrogels. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 1404–1454. 10.1039/C9SM02127B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reches M.; Gazit E. Casting metal nanowires within discrete self-assembled peptide nanotubes. Science 2003, 300, 625–627. 10.1126/science.1082387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.; Zhu P.; Li J. Self-assembly and application of diphenylalanine-based nanostructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1877–1890. 10.1039/b915765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Han T. H.; Kim Y.-I.; Park J.; Choi J.; Churchill D. G.; Kim S. O.; Hee H. Role of water in directing diphenylalanine assembly into nanotubes and nanowires. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 583–587. 10.1002/adma.200901973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing R.; Yuan C.; Li S.; Song J.; Li J.; Yan X. Charge-induced secondary structure transformation of amyloid-derived dipeptide assemblies from β-sheet to α-helix. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1537–1542. 10.1002/anie.201710642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monticelli L.; Kandasamy S. K.; Periole X.; Larson R. G.; Tieleman D. P.; Marrink S.-J. The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 819–834. 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrink S. J.; Tieleman D. P. Perspective on the Martini model. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6801–6822. 10.1039/c3cs60093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza P. C. T.; Alessandri R.; Barnoud J.; Thallmair S.; Faustino I.; Grünewald F.; Patmanidis I.; Abdizadeh H.; Bruininks B. M. H.; Wassenaar T. A.; et al. Martini 3: A general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 382–388. 10.1038/s41592-021-01098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederix P. W. J. M.; Ulijn R. V.; Hunt N. T.; Tuttle T. Virtual screening for dipeptide aggregation: Toward predictive tools for peptide self-assembly. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 2380–2384. 10.1021/jz2010573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Bera S.; Yao Y.; Zeng J.; Lao Z.; Dong X.; Gazit E.; Wei G. Prediction and characterization of liquid-liquid phase separation of minimalistic peptides. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100579 10.1016/j.xcrp.2021.100579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Q.; Jiang Y.; Cai X.; Yang F.; Li Z.; Han W. Conformation dependence of diphenylalanine self-assembly structures and dynamics: Insights from hybrid-resolution simulations. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 4455–4468. 10.1021/acsnano.8b09741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Wang K.; Zhao X.; Xu X.; Sun T. Influence of pH on the self-assembly of diphenylalanine peptides: molecular insights from coarse-grained simulations. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 5749–5757. 10.1039/D3SM00739A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskupek I.; Czaplewski C.; Sawicka J.; Iłowska E.; Dzierżyńska M.; Rodziewicz-Motowidło S.; Liwo A. Prediction of aggregation of biologically-active peptides with the UNRES coarse-grained model. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1140. 10.3390/biom12081140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan A. K.; Makowski M.; Augustynowicz A.; Liwo A. A general method for the derivation of the functional forms of the effective energy terms in coarse-grained energy functions of polymers. I. Backbone potentials of coarse-grained polypeptide chains. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 124106 10.1063/1.4978680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Czaplewski C.; Sieradzan A. K.; Lubecka E. A.; Lipska A. G.; Golon Ł.; Karczyńska A.; Krupa P.; Mozolewska M. A.; Makowski M.. et al. Scale-consistent approach to the derivation of coarse-grained force fields for simulating structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics of biopolymers. In Computational Approaches for Understanding Dynamical Systems: Protein Folding and Assembly; Strodel B.; Barz B., Eds.; Academic Press: London, 2020; Vol. 170, pp 73–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Liwo A.; Browne D.; Scheraga H. A. Mechanism of fiber assembly; treatment of Aβ-peptide peptide aggregation with a coarse-grained united-residue force field. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 404, 537–552. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Liwo A.; Scheraga H. A. A study of the α-helical intermediate preceding the aggregation of the amino-terminal fragment of the Aβ-amyloid peptide (1–28). J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 12978–12983. 10.1021/jp2050993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Maisuradze N.; Kachlishvili K.; Scheraga H. A.; Maisuradze G. G. Elucidating important sites and the mechanism for amyloid fibril formation by coarse-grained molecular dynamics. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 201–209. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Maisuradze G.; Scheraga H. Dependence of the formation of Tau and A Beta peptide mixed aggregates on the secondary structure of the N-terminal region of A Beta. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 7049–7056. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b04647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Pincus M. R.; Wawak R. J.; Rackovsky S.; Scheraga H. A. Prediction of protein conformation on the basis of a search for compact structures; test on avian pancreatic polypeptide. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 1715–1731. 10.1002/pro.5560021016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Czaplewski C.; Pillardy J.; Scheraga H. A. Cumulant-based expressions for the multibody terms for the correlation between local and electrostatic interactions in the united-residue force field. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 2323–2347. 10.1063/1.1383989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee Y. M.; Pande V. S. Multiplexed-replica exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding simulation. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 775–786. 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74897-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaplewski C.; Kalinowski S.; Liwo A.; Scheraga H. A. Application of multiplexing replica exchange molecular dynamics method to the UNRES force field: tests with α and α + β proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 627–640. 10.1021/ct800397z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Baranowski M.; Czaplewski C.; Gołaś E.; He Y.; Jagieła D.; Krupa P.; Maciejczyk M.; Makowski M.; Mozolewska M. A.; et al. A unified coarse-grained model of biological macromolecules based on mean-field multipole-multipole interactions. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2306. 10.1007/s00894-014-2306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan A. K.; Czaplewski C.; Krupa P.; Mozolewska M. A.; Karczyńska A. S.; Lipska A. G.; Lubecka E. A.; Gołaś E.; Wirecki T.; Makowski M.. et al. Modeling the Structure, Dynamics, and Transformations of Proteins with the UNRES Force Field.Protein Folding: Methods and Protocols; Muñoz V., Ed.; Springer US: New York, NY, 2022; pp 399–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo R. Generalized cumulant expansion method. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1962, 17, 1100–1120. 10.1143/JPSJ.17.1100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolinski A.; Skolnick J. Discretized model of proteins. I. Monte Carlo study of cooperativity in homopolypeptides. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 9412–9426. 10.1063/1.463317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniak A.; Biskupek I.; Bojarski K. K.; Czaplewski C.; Giełdoń A.; Kogut M.; Kogut M. M.; Krupa P.; Lipska A. G.; Liwo A.; et al. Modeling protein structures with the coarse-grained UNRES force field in the CASP14 experiment. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2021, 108, 108008 10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.108008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Khalili M.; Czaplewski C.; Kalinowski S.; Ołdziej S.; Wachucik K.; Scheraga H. A. Modification and optimization of the united-residue (UNRES) potential energy function for canonical simulations. I. Temperature dependence of the effective energy function and tests of the optimization method with single training proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 260–285. 10.1021/jp065380a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski E.; Makowski M.; Ołdziej S.; Czaplewski C.; Liwo A.; Scheraga H. A. Towards temperature-dependent coarse-grained potentials of side-chain interactions for protein folding simulations. I. Molecular dynamics study of a pair of methane molecules in water at various temperatures. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2009, 22, 547–552. 10.1093/protein/gzp028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldziej S.; Czaplewski C.; Liwo A.; Scheraga H. A.. Towards temperature dependent coarse-grained potential of side-chain interactions for protein folding simulations. In 2010 IEEE International Conference on BioInformatics and BioEngineering; IEEE, 2010; pp 263–266.

- Liwo A.; Ołdziej S.; Pincus M. R.; Wawak R. J.; Rackovsky S.; Scheraga H. A. A united-residue force field for off-lattice protein-structure simulations. I. Functional forms and parameters of long-range side-chain interaction potentials from protein crystal data. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 849–873. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Sieradzan A. K.; Lipska A. G.; Czaplewski C.; Joung I.; Żmudzińska W.; Hałabis A.; Ołdziej S. A general method for the derivation of the functional forms of the effective energy terms in coarse-grained energy functions of polymers. III. Determination of scale-consistent backbone-local and correlation potentials in the UNRES force field and force-field calibration and validation. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 155104 10.1063/1.5093015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwo A.; Ołdziej S.; Czaplewski C.; Kleinerman D. S.; Blood P.; Scheraga H. A. Implementation of molecular dynamics and its extensions with the coarse-grained UNRES force field on massively parallel systems; towards millisecond-scale simulations of protein structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6 (3), 890–909. 10.1021/ct9004068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili M.; Liwo A.; Rakowski F.; Grochowski P.; Scheraga H. A. Molecular dynamics with the united-residue model of polypeptide chains. I. Lagrange equations of motion and tests of numerical stability in the microcanonical mode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 13785–13797. 10.1021/jp058008o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili M.; Liwo A.; Jagielska A.; Scheraga H. A. Molecular dynamics with the united-residue model of polypeptide chains. II. Langevin and Berendsen-bath dynamics and tests on model α-helical systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 13798–13810. 10.1021/jp058007w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebst S.; Troyer M.; Hansmann U. H. Optimized parallel tempering simulations of proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 174903 10.1063/1.2186639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan A. K.; Sans-Duñó J.; Sans-Duñó J.; Lubecka E. A.; Czaplewski C.; Lipska A. G.; Leszczynski H.; Ocetkiewicz K. M.; Proficz J.; Czarnul P.; Krawczyk H. Optimization of parallel implementation of UNRES package for coarse-grained simulations to treat large proteins. J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 44, 602–625. 10.1002/jcc.27026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.; Kelley C.. et al. Gnuplot 4.6: An Interactive Plotting Program 2013http://gnuplot.sourceforge.net/. (accessed November 3, 2024).

- Kumar S.; Bouzida D.; Swendsen R. H.; Kollman P. A.; Rosenberg J. M. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992, 13, 1011–1021. 10.1002/jcc.540130812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh F.; Heck A.. Multivariate Data Analysis; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Heo L.; Feig M.. One Bead Per Residue Can Describe All-Atom Protein Structures 2023https://github.com/huhlim/cg2all. (accessed November 3, 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heo L.; Feig M. One bead per residue can describe all-atom protein structures. Structure 2024, 32, 97–111. 10.1016/j.str.2023.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon-Ferrer R.; Case D. A.; Walker R. C. An overview of the Amber biomolecular simulation package. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013, 3, 198–210. 10.1002/wcms.1121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C.; Kasavajhala K.; Belfon K.; Raguette L.; Huang H.; Migues A.; Bickel J.; Wang Y.; Pincay J.; Wu Q.; Simmerling C. ff19SB: Amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 528–552. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongan J.; Simmerling C.; McCammon J. A.; Case D. A.; Onufriev A. Generalized Born model with a simple, robust molecular volume correction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 156–169. 10.1021/ct600085e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Simmerling C. Fast pairwise approximation of solvent accessible surface area for implicit solvent simulations of proteins on CPUs and GPUs. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 5797–5814. 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubecka E. A.; Karczyńska A. S.; Lipska A. G.; Sieradzan A. K.; Ziȩba K.; Sikorska C.; Uciechowska U.; Samsonov S. A.; Krupa P.; Mozolewska M. A.; et al. Evaluation of the scale-consistent UNRES force field in template-free prediction of protein structures in the CASP13 experiment. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 92, 154–166. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ołdziej S.; Liwo A.; Czaplewski C.; Pillardy J.; Scheraga H. A. Optimization of the UNRES force field by hierarchical design of the potential-energy landscape: 2. Off-lattice tests of the method with single proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 16934–16949. 10.1021/jp0403285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa S.; Jernigan R. L. Estimation of effective interresidue contact energies from protein crystal structures: quasi-chemical approximation. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 534–552. 10.1021/ma00145a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchère J.-L.; Pliška V. Hydrophobic parameters-π of amino-acid side-chains from the partitioning of N-acetyl-amino-acid amides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1983, 18, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F.; Stefani M.; Taddei N.; Ramponi G.; Dobson C. M. Rationalization of the effects of mutations on peptide andprotein aggregation rates. Nature 2003, 424, 805–808. 10.1038/nature01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, LLC, The PyMOL molecular graphics system. 2010.

- https://www.chemicalbook.com/ChemicalProductProperty_EN_CB8389792.htm. (accessed November 3, 2024).

- https://www.chemicalbook.com/price-india/H-LEU-LEU-OH.htm. (accessed November 3, 2024).

- Scarel E.; De Corti M.; Polentarutti M.; Pierri G.; Tedesco C.; Marchesan S. Self-assembly of heterochiral, aliphatic dipeptides with Leu. J. Pept. Sci. 2024, 30, e3559 10.1002/psc.3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot N. S.; Parella T.; Aviles F.; Vendrell J.; Ventura S. Ile-Phe dipeptide self-assembly: Clues to amyloid formation. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 1732–1741. 10.1529/biophysj.106.096677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.; Cui Y.; He Q.; Wang K.; Li J.; Mu W.; Wang B.; Ou-yang Z. C. Reversible transitions between peptide nanotubes and vesicle-like structures including theoretical modeling studies. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 5974–5980. 10.1002/chem.200800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbaud J.-B.; Vey E.; Boothroyd S.; Smith A. M.; Ulijn R. V.; Saiani A.; Miller A. F. Enzymatic catalyzed synthesis and triggered gelation of ionic peptides. Langmuir 2010, 26, 11297–11303. 10.1021/la100623y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amdursky N.; Molotskii M.; Gazit E.; Rosenman G. Elementary building blocks of self-assembled peptide nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15632–15636. 10.1021/ja104373e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Teijlingen A.; Smith M. C.; Tuttle T. Short peptide self-assembly in the Martini coarse-grain force field family. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 644–654. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L. C.; Corey R. B. Stable configurations of polypeptide chains. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 1953, 141, 21–33. 10.1098/rspb.1953.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland D.; Scheraga H. A.. Theory of Helix-Coil Transitions in Biopolymers; Academic Press: N.Y., 1970. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.