Abstract

The 48-item Healthy Habits Questionnaire (HHQ-48) was developed to (1) monitor positive changes in family lifestyles following engagement in the Parents Plus Healthy Families (PP-HF) parent training programme and (2) be utilised as a standalone measure in clinical settings to identify and track problematic influential behaviours amongst families of children in weight-management services. This study aimed to develop and validate a brief version of the HHQ-48. The scale was administered to a cross-sectional community sample (n = 480), and on two occasions to a control sample (n = 50) and an experimental sample (n = 40) from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the PP-HF programme to assess test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change respectively. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis showed that a 23-item, 4-factor version of the HHQ (i.e., the HHQ-23) best fit the data. The scale and factor subscales had good internal consistency and test-retest reliability. They also had good concurrent and construct validity shown by significant correlations with another scale that assessed lifestyle issues, and scales that assessed parenting satisfaction, family functioning, and children’s strengths and difficulties. The HHQ-23 was sensitive to change following parents completing the PP-HF programme. The HHQ-23 may, therefore, be used to monitor positive changes in family lifestyles following engagement in the PP-HF parent training programme. The HHQ-23 also shows promising potential as a standalone screening measure or as part of a larger battery of screening assessments in paediatric weight-management services.

Keywords: Healthy lifestyle, paediatric, obesity, parental modelling, family environment, physical activity, diet, sedentary, sleep, screentime

Plain language summary

This study aimed to develop a brief version of the 48-item Healthy Habits Questionnaire (HHQ-48), which assesses how parents encourage healthy lifestyles in their children and evaluates the effectiveness of the 8-session Parents Plus – Healthy Families (PP-HF) program aimed at preventing childhood obesity. The HHQ-48 items are grouped into eight categories reflecting the PP-HF sessions: empowering parents, family connection, healthy food routines, healthy meals, active play, managing technology, restful sleep, and a happy, healthy mind. To create a shorter version of the HHQ, 480 parents completed the HHQ-48 and additional family life questionnaires online. Factor analysis identified 23 items grouped into four clusters: Screens and Routines, Activity, Parent-Child Connection, and Healthy Food & Good Example, forming the HHQ-23.The HHQ-23 showed strong correlations with the HHQ-48 and moderate correlations with other established questionnaires on children's lifestyles, parenting satisfaction, family functioning, and children's strengths and difficulties. In a test with 50 parents over eight weeks, HHQ-23 scores were stable. Scores increased for 41 parents who completed the HHQ-23 before and after the PP-HF program, demonstrating the HHQ-23's sensitivity to change.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a complex, chronic, multifactorial condition that is influenced by a combination of genetic, environmental, and behavioural factors (Ang et al., 2013; Cauchi et al., 2016). Lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviours, screentime, sleep patterns, home environment and family dynamics have all been shown to play significant roles in the development and progression of overweight and obesity among children (Aris & Block, 2022; Parkes et al., 2020; Waterlander et al., 2021; Watson et al., 2023). Screening for these factors is paramount as it allows healthcare professionals to identify children susceptible to obesity at an early stage, facilitating prompt intervention to curb additional weight gain and mitigate related health risks (Papamichael et al., 2022; Quick et al., 2017). Hence, assessment measures utilised to evaluate these factors must exhibit sensitivity and specificity tailored to the distinct requirements of this population, especially when applied to monitor the effectiveness of interventions (Krijger et al., 2022).

One such multi-domain assessment measure which has been developed for use in children living with overweight or obesity is the Healthy Habits Questionnaire-48 (HHQ-48, Keating et al., 2019). This 48-item measure was designed to: (1) monitor outcomes associated with a newly devised parenting intervention, the Parent Plus Healthy Families (PP-HF; Keating et al., 2021) programme, which addresses modifiable factors related to childhood overweight and obesity, and (2) as a standalone measure which healthcare professionals can utilise in clinical settings to identify and track problematic contributory (influential) lifestyle factors among children within weight-management services. The PP-HF programme and the HHQ-48 were developed by Parents Plus (https://www.parentsplus.ie). Parents Plus is an Irish charity that has developed a suite of evidence-based parent training programmes to address child and adolescent mental and physical health problems (Carr et al., 2017; Sharry & Fitzpatrick, 2016a, 2016b; Sharry & Hampson, 2022; Sharry, Hampson, & Fanning, 2016; Sharry et al., 2019; Sharry, Murphy, & Keating, 2016).

While the HHQ-48 was developed as part of the PP-HF programme, the full psychometric properties of the measure have not yet been established. Hence, the aim is this study was to develop and validate a brief, factorially valid version of the HHQ and address the following research questions:

1. What is the factor structure of the HHQ?

2. What is the internal consistency reliability of the HHQ, its factor scales, and its a priori content area scales (empowering parents, family connection, healthy food routines, healthy mealtimes, active play, managing technology, restful sleep, happy healthy mind)?

3. What is the test-retest reliability of the HHQ over 6 weeks in cases on a waiting list?

4. Are the HHQ, its factor scales, and a priori subscales responsive to change arising from parent’s engaging in the Parents Plus Healthy Families programme?

5. Does the HHQ have moderate correlations with measures of lifestyle, parental satisfaction, family adjustment, and children’s adjustment?

6. In a large convenience sample, what are the percentile norms for HHQ total scores?

Method

Ethics and preregistration

This study incorporated data from two sources: a cross-sectional community study and a longitudinal study. Both studies were conducted with ethical approval of University College Dublin Human Research Ethics Committee and informed consent of participants; the latter study was also approved by the South-East Health-Service Executive (HSE) ethics board. The study was preregistered on Open Science Framework (OSF) prior to data collection (https://osf.io/sp83n/).

Design

A cross-sectional design was used to address research questions 1, 2, 5 and 6 concerning the factor structure, internal consistency reliability, and concurrent and construct validity, and percentile norms of the HHQ. Four hundred and eighty participants completed the HHQ (N = 480) and other measures detailed below in an online survey. Research questions 3 and 4 were addressed by evaluating longitudinal data from a randomized control trial (RCT) evaluating the effectiveness of the PP-HF programme. The RCT data were collected on two occasions, approximately 8-weeks apart. The inclusion of this data allowed for an evaluation of the test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change of the HHQ arising from participation in the PP-HF programme.

Participants

A total of 571 parents/caregivers were recruited for this study: a longitudinal sample (n = 91) from a randomized control trial (RCT) evaluating the effectiveness of the PP-HF programme and a cross-sectional community sample (n = 480) recruited from an online research platform. Research questions 3 and 4 were addressed by evaluating the RCT longitudinal data. The RCT data were collected on two occasions, approximately 8-weeks apart. The inclusion of this data allowed for an evaluation of the test-retest reliability (control sample n = 50) and sensitivity to change of the HHQ arising from participation in the PP-HF programme (experimental sample n = 41). Demographic characteristics of the 3 samples are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of three samples.

| Community sample N = 480 | Test-retest clinical sample N = 50 | Sensitivity to change clinical sample N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender parent | Mother | f | 309 | 45 | 38 |

| % | 64.4% | 90.0% | 92.7% | ||

| Father | f | 171 | 5 | 3 | |

| % | 35.6% | 10.0% | 7.3% | ||

| Parent’s age | 20–29 | f | 30 | 1 | 1 |

| % | 6.3% | 2.0% | 2.4% | ||

| 30–39 | f | 192 | 22 | 15 | |

| % | 40.0% | 44.0% | 36.6% | ||

| 40–49 | f | 170 | 21 | 24 | |

| % | 35.4% | 42.0% | 58.5% | ||

| 50–59 | f | 60 | 5 | 1 | |

| % | 12.5% | 10.0% | 2.4% | ||

| 60 or over | f | 28 | 1 | 0 | |

| % | 5.8% | 2.0 | 0 | ||

| Number of children | 1-3 children | f | 461 | 40 | 38 |

| % | 96.0% | 80.0% | 92.7% | ||

| 4-6 children | f | 19 | 9 | 3 | |

| % | 4.0% | 18.0% | 7.3% | ||

| 7-9 children | f | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| % | 0 | 2.0% | 0 | ||

| Gender children | Boys | f | 161 | 14 | 11 |

| % | 33.5% | 28.0% | 26.8% | ||

| Girls | f | 149 | 10 | 11 | |

| % | 31.0% | 20.0% | 26.8% | ||

| Boys and girls | f | 170 | 26 | 19 | |

| % | 35.4% | 52.0% | 46.3% | ||

| Child’s age | Mostly under 5 years | f | 117 | 7 | 10 |

| % | 24.4% | 14.0% | 24.4% | ||

| Mostly between 6-12 years | f | 244 | 30 | 22 | |

| % | 50.8% | 60.0% | 53.7% | ||

| Ages spread from under 5 years–12 years | f | 119 | 13 | 9 | |

| % | 24.8% | 26.0% | 22.0% | ||

| Parents marital status | Married | f | 303 | 28 | 26 |

| % | 63.1% | 56.0% | 63.4% | ||

| Single | f | 38 | 8 | 7 | |

| % | 7.9% | 16.0% | 17.1% | ||

| Separated | f | 13 | 3 | 4 | |

| % | 2.7% | 6.0% | 9.8% | ||

| Divorced | f | 14 | 3 | 1 | |

| % | 2.9% | 6.0% | 2.4% | ||

| Living with partner | f | 108 | 8 | 3 | |

| % | 22.5% | 16.0% | 7.3% | ||

| Widowed | f | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| % | 0.8% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Ethnicity | Irish | f | 0 | 28 | 27 |

| % | 0 | 58.6% | 65.9% | ||

| Oher white background | f | 420 | 19 | 11 | |

| % | 87.5% | 34.3% | 26.8% | ||

| Other Asian background | f | 41 | 0 | 2 | |

| % | 8.5% | 0% | 4.9% | ||

| Other black background | f | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| % | 2.9% | 0% | 0 | ||

| Irish traveller | f | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| % | 0 | 2.9% | 0% | ||

| African | f | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| % | 1.0% | 4.3% | 2.4% | ||

| Country | Ireland | f | 12 | 38 | 41 |

| % | 2.5% | 76.% | 100% | ||

| UK | f | 468 | 12 | 0 | |

| % | 97.5% | 24.0% | 0 | ||

| Employment status | Employed | f | 394 | 26 | 21 |

| % | 82.1% | 52.0% | 51.2% | ||

| Unemployed | f | 86 | 24 | 20 | |

| % | 17.9% | 48.0% | 52.0% | ||

| Employment type | Unskilled work | f | 21 | 3 | 1 |

| % | 4.4% | 6.0% | 2.4% | ||

| Semi-skilled work | f | 83 | 5 | 5 | |

| % | 17.3% | 10.0% | 12.2% | ||

| Non-manual work | f | 39 | 1 | 1 | |

| % | 8.1% | 2.0% | 2.4% | ||

| Managerial/technical work | f | 149 | 8 | 7 | |

| % | 31.0% | 16.0% | 17.1% | ||

| Professional/employer | f | 147 | 10 | 14 | |

| % | 30.6% | 20.0% | 34.1% | ||

| Farmer | f | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| % | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Own-account workers | f | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| % | 1.0% | 2.0% | 0% | ||

| Other | f | 36 | 22 | 13 | |

| % | 7.5% | 44.0% | 31.7% | ||

Sample size

The three samples were large enough to permit adequately powered analyses. A sample of 480 was adequate for factor analysis of the 48-item HHQ, based on a minimum requirement of 10 cases per item, and a wide-ranging review of sample size recommendations for factor analysis by Kyriazos (2018). With regard to test-retest reliability, a power analysis based on Table 1a in Bujang et al. (Bujang & Baharum, 2017) showed that minimum samples of 22, 15 and 10 were required for detecting Intraclass correlations of 0.5, 0.6 and 0.7 respectively, with a p value of .05 and a power value of 0.8. With regard to sensitivity to change, a power analysis with G*Power (Kang, 2021) showed that to detect an effect size of d = 0.5 with a dependent t test having a p value of .05 and power value of 0.8, a sample of at least 27 would be required.

Instruments

The following scales were used in this study.

Healthy Habits Questionnaire (HHQ; Keating et al., 2019) is a 48-item measure which yields an overall score and scores for 8 a priori thematic subscales each comprising six items. The subscales assess parent empowerment, healthy food routines, healthy meals, active play, managing technology, sleep habits, healthy and happy mind, and family connection. Responses to items are rated on a 3- point Likert scale ranging from 0 = rarely to 2 = mostly with higher scores.

Lifestyle Behaviour Checklist (LBC; West & Sanders, 2009) is a 25-item measure that yields scores reflecting (1) parental perceptions of their children’s weight-related lifestyle problems, and (2) parents’ confidence in dealing with these. For each item parents rate the extent to which a specific lifestyle behaviour is a problem on a Likert scale, with ratings ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much. Parents also rate their confidence in dealing with each specific problematic behaviour on a Likert scale, with item ratings ranging from 1 = certain I can’t do it to 10 = certain I can do it.

Kansas Parental Satisfaction Scale (KPS; James et al., 1985) is a 3-item scale that measure parents’ satisfaction with themselves as a parent, satisfaction with the behaviour of their children, and satisfaction with their relationship with their children. Parents respond on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = extremely dissatisfied to 7 = extremely satisfied.

Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE; Carr & Stratton, 2017) is a 15-item scale that yields an overall family functioning score and scores on subscales that assess family strengths, difficulties, and communication. A six-point Likert scale is employed for each item - ranging from 1 = describes my family extremely well to 6 = that does not describe my family at all.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001) is a 25-item instrument that assesses parent perceptions of children’s behaviour. It yields scores for prosocial behaviour, conduct problems, inattention/hyperactivity problems, emotional symptoms, peer relationship problems and total difficulties scales. Three-point response formats are used for all items ranging from 0 = not true to 2 = certainly true.

Procedure

Participants in the community sample were recruited from the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland via Prolific (https://www.prolific.co). Prolific is a robust online research platform dedicated to facilitating impactful research endeavours, specialising in participant recruitment and management for online research projects, ensuring swift, dependable, and top-tier data collection. Participants recruited through Prolific read an information sheet, signed a consent form, completed the assessment pack on the Pavlovia (https://pavlovia.org) platform, and were paid £4.50 for engagement in the study.

Participants for the test-retest and sensitivity to change samples were recruited from 16 agencies, agencies primarily based in Ireland with one in the UK, who participated in a parallel cluster-randomised non-blinded control trial of the Parents Plus Healthy Families (PP-HF) programme. These agencies included various healthcare centres, schools, family resource centres, and child protection agencies. Participants were divided into intervention and control groups, with the former attending the 8-week PP-HF program. Data collection occurred before and after the intervention, with a follow-up for the intervention group. Randomisation was carried out in matched pairs using a coin flip method (facilitated by the website: https://justflipacoin.com).Agencies were matched based on pragmatic considerations, aiming to group those serving similar populations together, like matching primary care centres and family resource centres. The trial was non-blinded, and randomisation occurred in two phases in December 2021 and July 2022. Data from 91 trial participants who completed assessment measures at baseline and 6 weeks were used in the current study.

Data analysis plan

To address the first research question about the factor structure of the HHQ, exploratory factors analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted on two randomly selected subsamples each comprising 240 participants (n = 240) of the whole community sample (N = 480). The EFA was conducted using the IBM SPSS (Version 29) software and the CFA was conducted using the IBM AMOS version 27 software (Arbuckle, 2019). The suitability of the data for factor analysis was determined with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO; Kaiser & Rice, 1974) sampling adequacy index and Bartlett’s (1950) test of sphericity, with KMO values greater >0.8 and Bartlett’s test significant at p < .05 indicating suitability. To determine the factor structure of the HHQ the EFA was conducted on a randomly selected 50% subsample (n = 240) of the whole sample (N = 480) using Principal Axis Factoring with Promax rotation thus allowing factors to be correlated. The number of factors to be retained, and items to be retained within factors were determined with reference to parallel analysis (conducted using the parallel analysis engine devised by Patil Vivek and colleagues, 2017), scree plots, eigenvalues >1, item loadings >0.35 and the absence of high cross loadings >.35 on more than one factor. A CFA on a randomly selected 50% subsample of the complete dataset (N = 240) was conducted to check that the factor structure which emerged from the EFA fitted the data adequately. The adequacy of the model fit was assessed with the following indices and criteria: a ratio χ2/df < 2.5; comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) values >0.90 and >0.95 indicating good and excellent fits respectively; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) with values <0.08 and <0.05 indicating good and excellent model fits respectively (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016). To address the second question about internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s (1951) alpha was computed for the overall scale, a priori subscales, scales containing only those items retained in the factor analysis solution, and factor subscales. To address the third research question about test-retest reliability, intraclass correlations (Qin et al., 2019) were computed between HHQ scores returned on two occasions six weeks apart in a subsample of 50 cases in a waiting list control group of a RCT. To address the fourth question about sensitivity to change, this was assessed by evaluating the statistical significance of the difference between means of 41 (training group) cases before and after completing the PP-HF programme and expressing the magnitude of this difference as a standardized response mean (SRM) which is an effect size measure used to gauge the responsiveness of a scale to therapeutic change (Husted et al., 2000). To address the fifth question concerning the correlations between the HHQ and other measures, Pearson product moment correlations were calculated between the HHQ and the LBC, KPS, SCORE, and SDQ using data from the community sample (N = 480). This provided information about concurrent and construct validity. To address the 6th question, percentile norms were established using data from the community sample (N = 480).

Results

Factor structure

To answer the first research question about the factor structure of the HHQ, EFA and CFA indicated that the HHQ contained 4 factors which were named: Factor 1: Screens and routines, Factor 2: Activity, Factor 3: Parent-child connection and Factor 4: Healthy food and good example. Twenty-three of the 48 items were retained in this 4-factor version of the HHQ. For the EFA, the KMO Index (0.82 > 0.8) and significant Bartlett’s test result ) confirmed the factorability of the data set (n = 240). Results of an EFA using Principal Axis Factoring with Promax rotation and Kaiser Normalization are presented in Table 2. A 4-factor solution containing 28 items was achieved by removing 20 items with either low loadings (<.35), or high cross loadings (>.35). On more than one factor. This was supported by the parallel analysis and the scree plot inspection. Item loadings ranged from .36 to .83. All factors had eigenvalues >1 and cumulatively explained 44.23% of the variance.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis of the HHQ.

| HHQ-48 item no. | Factor 1 - screens and routines | F 1 | F2 | F 3 | F 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Mealtimes are a screen-free time in our home | .821 | |||

| 24 | Mealtimes are a social time to chat in our house | .753 | |||

| 33 | We have screen-free places in our home, including bedrooms and the dinner table | .594 | |||

| 21 | We sit down together as a family to eat meals | .580 | |||

| 41 | My child has a consistent and relaxing bedtime routine | .410 | |||

| 35* | We have social screen times in our house when I am involved. For example, watching TV or playing a video game together | .383 | |||

| 40 | My child does not use screens to fall asleep. For example, watching TV or using their phone in bed | .360 | |||

| Factor 2 - activity (6 items) | |||||

| 28 | My children get active | .830 | |||

| 31 | My children engage in regular activities that they enjoy, for example: Sports, hide and seek, dancing, chasing | .719 | |||

| 30 | My children get 60 minutes of activity in their daily routine | .679 | |||

| 27 | We have an environment in our home which promotes physical activity | .666 | |||

| 29 | We find creative ways to be active at home | .418 | |||

| 07 | I Spend fun time with each of my children daily, for example playing a game, reading a book, going for a walk | .401 | |||

| Factor 3 - parent-child connection | |||||

| 45 | I help my children to manage their feelings | .692 | |||

| 44 | I talk to my children about feelings | .685 | |||

| 34* | I take steps to ensure my children are safe online. For example, teaching safety, using ‘parental controls’ on devices | .477 | |||

| 08* | I set aside a time each day to check-in one to one with my children | .447 | |||

| 48 | I encourage my children’s passions by helping them to find interests that fit with their strengths and abilities | .437 | |||

| 43 | I encourage my children by praising them more than I criticise them | .384 | |||

| 11 | I actively listen to my children | .362 | |||

| Factor 4 - Healthy food and good example | |||||

| 12 | We eat a balanced diet using the food pyramid as a guide | .522 | |||

| 04 | I Create a healthy home environment for my children. For example, I limit treats and screentime in the home | .509 | |||

| 37 | I lead by example – I control my own screen time | .505 | |||

| 06* | When changing habits, I lead by example and make positive changes myself | .502 | |||

| 23 | I lead by example and show my children how to eat healthy foods | .446 | |||

| 16 | My children eat a healthy breakfast each morning, for example: Porridge and fruit | .417 | |||

| 46* | I take care of my own emotional well-being as a parent | .414 | |||

| 19 | I give my children ‘treat foods’ in small portions. For example: I give a couple of sweets rather than a whole bag | .357 | |||

| Eigen value | 6.29 | 2.43 | 2.08 | 1.58 | |

| Percent of variance explained | 22.49 | 6.68 | 7.41 | 5.65 | |

| Cumulative percent of variance explained | 22.49 | 31.17 | 38.58 | 44.23 | |

Note. N = 240. The extraction method was principal axis factoring with an Promax rotation with Kaiser Normalization. *These items were removed from the final short version of the HHQ, because they compromised the fit of the model in CFA.

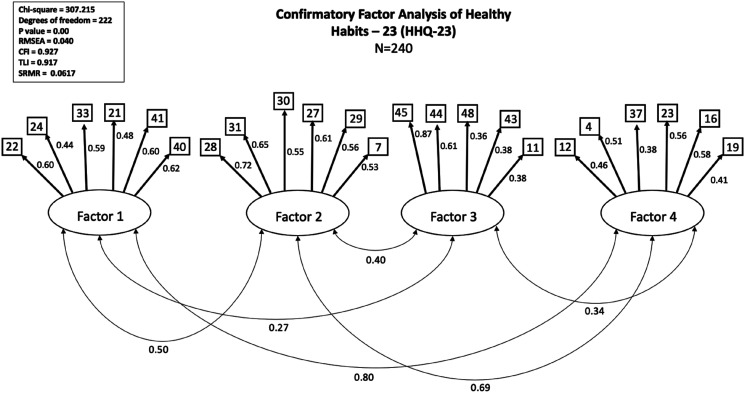

A CFA applied on a data subsample (n = 240) indicated that the factor structure which emerged from the EFA fitted the data adequately. However, 5 items had low loadings (<0.35), and when removed improved the model fit. The results of the CFA are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis of HHQ (n = 240). All factor loadings are standardised.

The final 4-factor solution contained a total of 23 HHQ items and will be referred to as the HHQ-23. The factors were named: Factor 1: Screens and routines (6 items), Factor 2: Activity (6 items), Factor 3: Parent-child connection (5-items), and Factor 4: Healthy food and good example. Fit indices fell within the range for a good model fit χ2/df = 1.384 (<.25), CFI = 0.927 (>.9), TLI = 0.917 (>.9), RMSEA = 0.040 (<.08), SRMR = 0.0617 (<.08). Correlations between factor scales ranged from .22 to .53 as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, alpha reliability coefficients, and correlations between HHQ-48, HHQ - 23 and its factors scales with measures of relational functioning, lifestyle, and wellbeing.

| Variables | M | SD | Cronbach’s alpha reliability | Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHQ-48 total | HHQ-23 total | HHQ Factor 1 | HHQ Factor 2 | HHQ Factor 3 | HHQ Factor 4 | ||||

| Healthy habits questionnaire (HHQ) | |||||||||

| HHQ-48 total | 72.97 | 11.46 | .89 | 1 | |||||

| HHQ-23 total | 35.33 | 6.63 | .85 | .94 | 1 | ||||

| Factor 1: Screens and routines | 9.11 | 2.68 | .75 | .70 | .78 | 1 | |||

| Factor 2: Activity | 9.11 | 2.44 | .79 | .70 | .76 | .36 | 1 | ||

| Factor 3: Parent-child connection | 9.02 | 1.41 | .68 | .53 | .52 | .22 | .34 | 1 | |

| Factor 4: Healthy food & good example | 8.09 | 5.90 | .69 | .79 | .81 | .53 | .47 | .27 | 1 |

| Lifestyle behaviour checklist (LBC) | |||||||||

| LBC total child lifestyle problems | 52.53 | 18.18 | .89 | −.38 | −.36 | −.29 | −.23 | −.25 | −.28 |

| LBC total parental confidence in managing child lifestyle problems | 196.01 | 39.10 | .96 | .24 | .20 | .09 | .14 | .20 | .18 |

| Kansas parenting satisfaction scale (KPS) | |||||||||

| KPS Total satisfaction score | 15.90 | 2.27 | .75 | .39 | .36 | .25 | .23 | .33 | .29 |

| Systemic clinical outcome and routine evaluation | |||||||||

| SCORE - total family functioning | 2.01 | .65 | .89 | .39 | −.35 | −.21 | −.25 | −.42 | −.21 |

| SCORE - family strengths | 2.18 | .76 | .84 | .41 | −.38 | −.21 | −.31 | −.45 | −.24 |

| SCORE - family difficulties | 1.90 | .78 | .77 | .31 | −.26 | −.19 | −.17 | −.28 | −.17 |

| SCORE - family communication | 1.95 | .72 | .70 | .27 | −.24 | −.15 | −.16 | −.35 | −.13 |

| Strengths and difficulties questionnaire | |||||||||

| Total difficulties | 8.35 | 5.17 | .82 | .31 | −.32 | −.26 | −.26 | −.13 | −.25 |

| Conduct problems | 1.09 | 1.30 | .60 | .24 | −.22 | −.21 | .10 | −.19 | −.15 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention problems | 3.63 | 2.30 | .78 | .26 | −.26 | −.24 | .16 | −.09 | −.23 |

| Emotional symptoms | 1.83 | 1.95 | .73 | .22 | −.24 | −.17 | −.25 | −.03 | −.20 |

| Peer relation problems | 1.79 | 1.70 | .60 | .16 | −.17 | −.11 | −.19 | −.09 | −.10 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 6.67 | 2.07 | .78 | .26 | .24 | .17 | .18 | .30 | .14 |

Note. N = 480. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. For a 2-tailed test, Pearson product moment correlations of r = .15 are significant at p < .001; correlations of r = .12 are significant at p < .01, and correlations of r = .09 are significant at p < .05. Correlations of .1, .3 and .5 are considered small, medium, and large respectively.

Internal consistency reliability

In answer to the second research question about the internal consistency reliability of the HHQ, Cronbach alpha analyses showed that the HHQ-23 had good internal consistency reliability. The reliability of the HHQ-23 was .85. The reliability coefficients for Factor 1: Screens and routines, Factor 2: Activity, Factor 3: Parent-child connection and Factor 4: Healthy food and good example scales were .75, .79, .68 and .69 respectively. The internal consistency reliability coefficient of the HHQ-23 (.85) was only marginally lower than that of the HHQ-48 (.89). Apart from the Active Play subscale which had a reliability coefficient of .78, the remaining HHQ-48 a priori subscale reliability coefficients, which ranged from .45 to .66, were lower than those of the four factor scales of the HHQ-23. (See Table S1 in supplementary material).

Test-retest reliability

In answer the third research question about test-retest reliability, the HHQ-23 and its factor scales showed a high level of test-retest reliability (>.8) over a six-week period in a sample of 50 participants. The test-retest intraclass correlation for the HHQ-23 was .87. Those for Factor 1: Screens and routines, Factor 2: Activity, Factor 3: Parent-child connection and Factor 4: Healthy food and good example scales were .83, .87, .86 and .83 respectively. These test-retest intraclass correlations were quite similar to those of the HHQ-48, and its’ a-priori subscales. The test-retest reliability coefficient for the HHQ-48 was .90, and those of its eight subscales ranged from .75 to .87. (See Table S1 in supplementary material).

Responsiveness to change

In answer to the fourth research question about responsiveness to change, the HHQ-23, and its factor scales showed responsiveness to change arising from parental participation in the PP-HF Programme in a sample of 41 participants, as shown in Table 3. Paired sample t-tests showed that mean scores on the HHQ-23 and three of four factor scales improved significantly from pre- to post-intervention. The standardized response mean (SRM) for the HHQ-23 total was .445. SRMs for HHQ-23 Factor 1: Screens and routines, Factor 2: Activity, and Factor 4: Healthy food and good example scales were .312, .384, and .498 respectively and associated with significant change. The SRM for Factor 3: Parent-child connection was .111, and the difference between pre- and post- intervention mean scores was not significant. SRM values greater than .8, between .5 and .8, and between .2 and .5 indicate high, medium, and low responsiveness to change respectively. Thus, the HHQ-23 total and 3 of its factor subscales showed low responsiveness to change. In contrast the SRM of the HHQ-48 total was .631, indicating medium responsiveness to change. Three HHQ-48 eight a priori subscales showed medium responsiveness to change with SRMs between .584 and .694; four showed low responsiveness to change with SRMs between .294 and .403. One HHQ-48 a priori scale (restful sleep) was not significantly responsive to change. The SRM results in Table 3 indicate that HHQ-23 is less responsive to change than the HHQ-48.

Table 3.

Responsiveness of the HHQ to change arising from parents plus healthy families parent training programme.

| Pre-PPHF M (SD) N = 41 |

Post-PPHF M (SD) N = 41 |

t | p | SRM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHQ-23 total and factor scales | |||||

| HHQ-23 total | 35.10 (7.17) | 38.20 (5.54) | 2.850** | .003 | .445 |

| Factor 1: Screens and routines (6 items) | 9.07 (2.61) | 9.93 (2.17) | 1.999* | .026 | .312 |

| Factor 2: Activity (6 items) | 8.63 (2.48) | 9.54 (2.35) | 2.455** | .009 | .384 |

| Factor 3: Parent-child connection (5 items) | 8.78 (1.57) | 8.93 (1.25) | 0.713 | .240 | .111 |

| Factor 4: Healthy food & good example (6 items) | 8.61 (2.67) | 9.80 (1.72) | 3.188*** | .001 | .498 |

| HHQ-48 total and a priori subscales | |||||

| HHQ-48 item total | 70.56 (12.38) | 78.54 (9.89) | 4.036*** | <.001 | .631 |

| HHQ empowering parents | 9.20 (1.89) | 10.41 (1.45) | 4.019*** | <.001 | .628 |

| HHQ family connection | 6.39 (2.11) | 7.68 (1.90) | 3.735*** | <.001 | .584 |

| HHQ healthy food routines | 12.17 (3.26) | 14.29 (2.42) | 4.441*** | <.001 | .694 |

| HHQ healthy meals | 8.93 (2.33) | 9.72 (2.03) | 1.881* | .034 | .294 |

| HHQ active play | 7.15 (2.29) | 7.83 (2.08) | 2.141* | .019 | .335 |

| HHQ managing technology | 8.90 (2.46) | 9.95 (1.86) | 2.576** | .007 | .403 |

| HHQ restful sleep | 8.32 (1.66) | 88.56 (1.58) | 1.168 | .125 | .183 |

| HHQ happy healthy mind | 9.51 (2.01) | 10.07 (1.55) | 1.893* | .033 | .296 |

Note. HHQ = Healthy habits questionnaire. M = Mean. SD = Standard deviation. t = dependent t test result. p = probability level. SRM = Standardised Response Mean. SRM >0.8 indicates high, 0.5–0.8 medium, and 0.2–<0.5 low responsiveness. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Correlation between HHQ and other scales: concurrent and construct validity

In answer to the fifth research question about the associations between the HHQ-23 and other measures (shown in Table 4), in the community sample (N = 480) significant (p < .001) correlations with medium sized absolute values between .30 and .36 were found between the HHQ-23 total and LBC total child lifestyle problems (r = −.36), KPS parenting satisfaction (r = .36), SCORE-15 total family functioning (r = −.35), and SDQ total difficulties (r = −.32). A significant (p < .001) but smaller correlation (r = .20) was found between the HHQ-23 total and LBC total parental confidence in managing child lifestyle problems. This pattern of correlations between the HHQ-23 total, and the summary or total scores of other scales included in this study supports the concurrent and construct validity of the HHQ-23.

There were significant (p < .001) small correlations with absolute values between .17 and .26 between the HHQ-23 total and the three SCORE-15 and five SDQ subscales, with the exception of SCORE-15 family strengths which had a medium sized correlation with the HHQ-23 total (r = .38, p < .001). There were small to medium correlations with absolute values between .03 and .45 between the four HHQ-23 factor scales and LBC, KPS, SCORE-15 and SDQ total and subscale scores. All of these correlations were significant at least at p < .05, with the exception of the correlation between SDQ child’s emotional symptoms and HHQ-23 Factor 3: Parent-child connection (r = .03, p > .05). This pattern of correlations involving HHQ-23 factor scores, and subscale scores of other scales included in this study provides further support for the concurrent and construct validity of the HHQ-23.

It is noteworthy that there was a correlation of .94 between the HHQ-23 and HHQ-48, and that the pattern of correlations between the HHQ-48 and LBC, KPS, SCORE-15, and SDQ scales and subscales was similar to that of the HHQ-23.

HHQ norms

In answer to the sixth research question about percentile norms, a set of norms was developed based on HHQ-23 total scores of the online community sample of 480 parents.

HHQ-23 total scores and corresponding percentiles at approximately 10 percentile intervals were as follows: 25 = 10th, 30 = 22nd, 33 = 32nd, 34 = 38th, 36 = 49th, 38 = 63rd, 39 = 70th, 41 = 83rd, 43 = 94th, and 46 = 100th percentile. There is a full set of HHQ-23 norms in Table S2 in supplementary materials.

Discussion

This study addressed 6 research questions and led to the following conclusions related to these questions. (1) A shorter 23-item version of the HHQ with 4 factors best fits the data. (2) The HHQ-23 and its factor scales have good internal consistency reliability. (3) The HHQ-23 and its factor scales have good rest-retest reliability. (4) The HHQ-23 and three of its factor scales are responsive to change arising from engaging in the PP-HF programme. (5) The HHQ-23 and its factor scales have good concurrent and construct validity shown by significant correlations with another scale that assessed lifestyle issues, and scales that assessed parenting satisfaction, family functioning, and children’s strengths and difficulties. (6) HHQ norms based on responses of an online community sample were established. In light of these conclusions, the HHQ-23 may be used to monitor positive changes in family lifestyles following engagement in the PP-HF parent training programme. Likewise, considering (1) the validity with other lifestyle and behavioural measures and (2) recognising that the shorter 23-item version of the HHQ succinctly examines four separate domains which are highly relevant to this population (i.e. Albataineh et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2019; Janssen, 2014; Warnick et al., 2019), it is reasonable to assert that the HHQ-23 shows potential as a standalone clinical assessment tool (for paediatric weight management services and beyond). The following section will discuss the ramifications of these findings in terms of strengths, limitations, and avenues which future studies could explore.

Given the limited number of measures in this area, a large number of childhood obesity intervention outcome studies (i.e. Eiffener et al., 2019; Fagg et al., 2014; Skjåkødegård et al., 2022) have relied on generic clinical assessment measures, such as the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and the SDQ (SDQ; Goodman, 2001), or one dimensional measures, such as the Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ; Wardle et al., 2001), in lieu of cohort-specific, multifactorial tools. However, because these generic measures were not designed for children at risk of obesity, many relevant factors may have not been captured or considered, and a more specific measure which maps onto the modifiable factors which interventions seek to address would have been more appropriate. Fortunately, findings from this study showcase the utility of the HHQ-23 as an adequate measure for tracking positive outcomes for family functioning and lifestyle intervention programmes which target childhood obesity, such as the PP-HF programme.

As previously highlighted in a systematic review conducted by the primary author of this paper, there is a paucity of validated, multi-factorial assessment measures with robust psychometric proprieties for children aged between 2 and 12 years old who are living with overweight and obesity, or at risk of developing obesity (Davis et al., 2024). An additional finding from this review determined that a considerable number of assessment instruments only assessed one construct – such as dietary intake alone or physical activity alone – and consequently omitted to account for the multi-factorial influences on obesity and overweight in this population. Indeed, findings from another recent review conducted by Krijger and colleagues on lifestyle screening measures for an expanded age range of 0–18 years old noted that tool validation was limited (Krijger et al., 2022). This review also emphasised that there is a considerable need for a specific, easy-to-administer measure. The HHQ-23 addresses many of these outstanding characteristics: easy to administer and score (i.e., consistent 3-point Likert scale used throughout), brief and accessible, assesses numerous domains relevant to this population and has robust psychometric properties.

Notwithstanding, this validation study of HHQ-23 had a number of limitations, which may be explored and addressed in future studies to further establish the potential applicability of this measure. The factor analysis of the HHQ-23 was conducted in a large community sample which was invariably a sample of convenience and likely to have been highly heterogenous. Future studies may seek to refine the scope of the cohort to parents/caregivers of children living with overweight or obesity. Furthermore, body mass indices (BMI) or a record of the children’s’ weight statuses were not gathered for this study, as given that the community study was conducted online, it was not feasible on this occasion to accurately gather this data. Hence, future studies may try and administer this measure in a more specialised setting such as a weight management clinic (or similar) to further standardise the HHQ-23. A further limitation is that the HHQ-23, while briefer and more factorially valid that the HHQ-48, has achieved these advantages at the cost of becoming marginally less responsive to change than the HHQ-48. Future psychometric investigations of the HHQ may focus on identifying an item set with a high level of responsiveness to change, but which is also brief and factorially valid.

In conclusion, this study entailed a thorough exploration of the psychometric properties of the HHQ, which has led to the formation of a valid, robust, and precise assessment measure. This measure can be utilised in clinical settings, such as paediatric weight management clinics, as well as for research purposes, enabling the monitoring of outcomes for interventions aimed at preventing and managing childhood obesity.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for The healthy habits questionnaire (HHQ): Validation of a measure designed to assess problematic influential behaviours amongst families of children living with obesity or a risk of developing obesity by Bríd Áine Davis, Claire O’Dwyer, Adele Keating, John Sharry, Eddie Murphy, Alan Doran, Finiki Nearchou and Alan Carr in Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Author biographies

Dr. Bríd Áine Davis, PhD, DPsychSc, is a Clinical Psychologist based in Dublin, Ireland. She obtained her Professional Doctorate in Clinical Psychology from University College Dublin (UCD), where her thesis focused on evaluating and validating the ‘Healthy Habits Questionnaire,’ developed in collaboration with the Parents Plus Healthy Families Programme.

Dr. Claire O’Dwyer, DPsychSc, is a Clinical Psychologist based in Dublin, Ireland. She completed her Professional Doctorate in Clinical Psychology with University College Dublin (UCD), in which her thesis centred on a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) evaluation of the Parents Plus Healthy Families Programme.

Dr. Adele Keating, DPsychSc, is a Clinical Psychologist, Adjunct Assistant Professor with the UCD School of Psychology, and Group Facilitator Trainer and Programme Co-developer with the Parents Plus charity based in the Mater Hospital, Dublin.

Professor John Sharry, DPsych, is a Social Worker, Adjunct Professor with the UCD School of Psychology, and Programme Co-developer, Co-founder, and Clinical Director of the Parents Plus charity based in the Mater Hospital, Dublin.

Dr. Eddie Murphy, DPsychSc, is a Clinical Psychologist, Principal Psychology Manager with the Health Service Executive (HSE) in Laois/Offaly, Ireland, and Adjunct Associate Professor with the UCD School of Psychology.

Alan Doran, MPsychSc, is a Clinical Psychologist and Principal Clinical Psychology Manager with the Health Service Executive (HSE) in Meath, Ireland.

Dr. Finiki (Niki) Nearchou, PhD, is an Associate Professor in Psychology with the UCD School of Psychology and Research Director of the UCD Doctoral Programme in Clinical Psychology

Professor Alan Carr, PhD, is a Professor of Clinical Psychology, Founding Director of the UCD Professional Doctoral Programme in Clinical Psychology, and Research Advisor to the Parents Plus charity.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by a Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) (Doctorate in Clinical Psychology - Training Fees) and Parents Plus Charity (Online Recruitment Stipend).

Ethics and integrity policies: This research was conducted and manuscript produced in a way consistent with CCP&P ethics and integrity policies.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

This research was conducted with ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee, University College Dublin, and informed consent of participants.

ORCID iDs

Bríd Áine Davis https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4606-4432

Alan Carr https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4563-8852

References

- Achenbach T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behaviour checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Albataineh S. R., Badran E. F., Tayyem R. F. (2019). Overweight and obesity in childhood: Dietary, biochemical, inflammatory and lifestyle risk factors. Obesity Medicine, 15, 100112. 10.1016/j.obmed.2019.100112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ang Y. N., Wee B. S., Poh B. K., Ismail M. N. (2013). Multifactorial influences of childhood obesity. Current Obesity Reports, 2, 10–22. 10.1007/s13679-012-0042-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. L. (2019). Amos. IBM SPSS.Version 26.0. [Google Scholar]

- Aris I. M., Block J. P. (2022). Childhood obesity interventions—going beyond the individual. JAMA Paediatrics, 176(1), Article e214388. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett M. S. (1950). Tests of significance in factor analysis. British Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 77–85. 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bujang M. A., Baharum N. (2017). A simplified guide to determination of sample size requirements for estimating the value of intraclass correlation coefficient: A review. Archives of Orofacial Sciences, 12(1), 1–11. 10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A., Hartnett D., Brosnan E., Sharry J. (2017). Parents Plus systemic, solution-focused parent training programs: Description, review of the evidence base, and meta-Analysis. Family Process, 56(3), 652–668. 10.1111/famp.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A., Stratton P. (2017). SCORE family assessment questionnaire: A decade of progress. Family Process, 56(2), 285–301. 10.1111/famp.12280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauchi D., Glonti K., Petticrew M., Knai C. (2016). Environmental components of childhood obesity prevention interventions: An overview of systematic reviews. Obesity Reviews, 17(11), 1116–1130. 10.1111/obr.12441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Davis B. Á., O’ Dwyer C., Davis M. E., Looney K., Carr (2024). A systematic review of psychometric scales that assess familial, lifestyle, and behavioural factors for children living with overweight or obesity, or at risk of developing obesity. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. [Google Scholar]

- Eiffener E., Eli K., Ek A., Sandvik P., Somaraki M., Kremers S., Nowicka P. (2019). The influence of pre-schoolers’ emotional and behavioural problems on obesity treatment outcomes: Secondary findings from a randomized controlled trial. Paediatric Obesity, 14(11), Article e12556. 10.1111/ijpo.12556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagg J., Chadwick P., Cole T. J., Cummins S., Goldstein H., Lewis H., Law C. (2014). From trial to population: A study of a family-based community intervention for childhood overweight implemented at scale. International Journal of Obesity, 38(10), 1343–1349. 10.1038/ijo.2014.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang K., Mu M., Liu K., He Y. (2019). Screen time and childhood overweight/obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 45(5), 744–753. 10.1111/cch.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. T., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husted J. A., Cook R. J., Farewell V. T., Gladman D. D. (2000). Methods for assessing responsiveness: A critical review and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(5), 459–468. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00206-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D. E., Schumm W. R., Kennedy C. E., Grigsby C. C., Shectman K. L., Nichols C. W. (1985). Characteristics of the Kansas Parental Satisfaction Scale among two samples of married parents. Psychological Reports, 57(1), 163–169. 10.2466/pr0.1985.57.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I. (2014). Active play: An important physical activity strategy in the fight against childhood obesity. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 105(1), e22–e27. 10.17269/cjph.105.4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H. F., Rice J. (1974). Little jiffy, mark iv. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 111–117. 10.1177/001316447403400115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. (2021). Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* Power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18(17), 1–12. 10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating A., Sharry J., Doody (2019). Healthy habits questionnaire. Parents Plus. [Google Scholar]

- Keating A., Sharry J., Doody N., Choudhry M. A. (2021). Parents Plus healthy families programme: A parenting course promoting healthy living. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (4th ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Krijger A., Ter Borg S., Elstgeest L., van Rossum C., Verkaik-Kloosterman J., Steenbergen E., Joosten K. (2022). Lifestyle screening tools for children in the community setting: A systematic review. Nutrients, 14(14), 2899. 10.3390/nu14142899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology, 9(08), 2207. 10.4236/psych.2018.98126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichael M. M., Karaglani E., Boutsikou T., Dedousis V., Cardon G., Iotova V., Feel4Diabetes-Study Group . (2022). How do the home food environment, parenting practices, health beliefs, and screen time affect the weight status of European children? The Feel4Diabetes study. Nutrition, 103, 111834. 10.1016/j.nut.2022.111834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes A., Green M., Pearce A. (2020). Do bedroom screens and the mealtime environment shape different trajectories of child overweight and obesity? Research using the growing up in scotland study. International Journal of Obesity, 44(4), 790–802. 10.1038/s41366-019-0502-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil Vivek H., Singh S. N., Mishra S., Todd Donavan D. (2017). Parallel analysis engine to aid in determining number of factors to retain using R. [Computer software]. https://analytics.gonzaga.edu/parallelengine/ [Google Scholar]

- Qin S., Nelson L., McLeod L., Eremenco S., Coons S. J. (2019). Assessing test-retest reliability of patient-reported outcome measures using intraclass correlation coefficients: Recommendations for selecting and documenting the analytical formula. Quality of Life Research, 28(4), 1029–1033. 10.1007/s11136-018-2076-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick V., Martin-Biggers J., Povis G. A., Hongu N., Worobey J., Byrd-Bredbenner C. (2017). A socio-ecological examination of weight-related characteristics of the home environment and lifestyles of households with young children. Nutrients, 9(6), 604. 10.3390/nu9060604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Fitzpatrick C. (2016. a). Parents Plus children’s programme: A DVD-based parenting course on managing behaviour problems and promoting learning and confidence in children aged 6-11. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Fitzpatrick C. (2016. b). Parents Plus adolescents programme: A DVD based parenting course on managing conflict and getting on better with older children and teenagers aged 11-16 years. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Hampson G. (2022). Parents Plus ADHD children’s programme. An evidence-Based parenting course for parents of children aged 6-12 years with Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Dublin. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Hampson G., Fanning M. (2016). Parents Plus early years programme: A DVD-based parenting course on promoting development and managing behaviour problems in young children aged 1-6. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Hampson G., O’Leary A. (2019). Parents Plus Special Needs Programme. An evidence-based parenting course for parents of adolescents with intellectual disability. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [Google Scholar]

- Sharry J., Murphy M., Keating A. (2016). Parents Plus – Parenting when separated programme. Parents Plus. https://www.parentsplus.ie [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjåkødegård H. F., Conlon R. P., Hystad S. W., Roelants M., Olsson S. J., Frisk B., Juliusson P. B. (2022). Family‐based treatment of children with severe obesity in a public healthcare setting: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Obesity, 12(3), Article e12513. 10.1111/cob.12513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Guthrie C. A., Sanderson S., Rapoport L. (2001). Development of the children's eating behaviour questionnaire. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42(7), 963–970. 10.1017/S0021963001007727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick J. L., Stromberg S. E., Krietsch K. M., Janicke D. M. (2019). Family functioning mediates the relationship between child behaviour problems and parent feeding practices in youth with overweight or obesity. Translational Behavioural Medicine, 9(3), 431–439. 10.1093/tbm/ibz050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterlander W. E., Singh A., Altenburg T., Dijkstra C., Luna Pinzon A., Anselma M., Stronks K. (2021). Understanding obesity‐related behaviours in youth from a systems dynamics perspective: The use of causal loop diagrams. Obesity Reviews, 22(7), Article e13185. 10.1111/obr.13185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A., Dumuid D., Maher C., Fraysse F., Mauch C., Tomkinson G. R., Olds T. (2023). Parenting styles and their associations with children's body composition, activity patterns, fitness, diet, health, and academic achievement. Childhood Obesity, 19(5), 316–331. 10.1089/chi.2022.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West F., Sanders M. R. (2009). The lifestyle behaviour checklist: A measure of weight-related problem behaviour in obese children. International Journal of Paediatric Obesity, 4(4), 266–273. 10.3109/17477160902811199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for The healthy habits questionnaire (HHQ): Validation of a measure designed to assess problematic influential behaviours amongst families of children living with obesity or a risk of developing obesity by Bríd Áine Davis, Claire O’Dwyer, Adele Keating, John Sharry, Eddie Murphy, Alan Doran, Finiki Nearchou and Alan Carr in Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry.