Abstract

Background

No clear consensus exists regarding the safest anti-diabetic drugs with the least adverse events on bone health. This umbrella systematic review therefore aims to assess the published meta-analysis studies of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in this field.

Methods

All relevant meta-analysis studies of RCTs assessing the effects of anti-diabetic agents on bone health in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) were collected in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). English articles published until 15 March 2023 were collected through the search of Cochrane Library, Scopus, ISI Web of Sciences, PubMed, and Embase using the terms “Diabetes mellitus”, “anti-diabetic drugs”, “Bone biomarker”, “Bone fracture, “Bone mineral density” and their equivalents. The methodological and evidence quality assessments were performed for all included studies.

Results

From among 2220 potentially eligible studies, 71 meta-analyses on diabetic patients were included. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-is) showed no or equivalent effect on the risk of fracture. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is) and Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1Ras) were reported to have controversial effects on bone fracture, with some RCTs pointing out the bone protective effects of certain members of these two medication classes. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) were linked with increased fracture risk as well as higher concentrations of C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx), a bone resorption marker.

Conclusion

The present systematic umbrella review observed varied results on the association between the use of anti-diabetic drugs and DM-related fracture risk. The clinical efficacy of various anti-diabetic drugs, therefore, should be weighed against their risks and benefits in each patient.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-024-01518-2.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Anti-diabetic agents, Bone biomarkers, Bone mineral density, Bone fracture

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder that affects more than 400 million people worldwide, a prevalence that is expected to increase to more than 783 million by 2045 [1]. DM and antidiabetic drugs are associated with various complications, some of which are linked with their effect on bone health and thus the fracture risk [2–4]. In the past few years, a high prevalence of osteoporosis has been reported in different DM populations. This is while the global prevalence of osteoporosis in diabetes patients has not been well documented.

Bone health can be assessed either by measuring bone mineral density (BMD), which reflects the amount of mineralized bone tissue per unit volume, or bone turnover markers (BTMs) that reveal the rate of bone formation and resorption [5]. Both BMD and BTMs values are influenced by various factors, such as age, sex, genetics, hormones, nutrition, physical activity, and medications [2, 6–9]. It is well-known that compared to non-diabetic individuals, patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) patients generally have higher BMD values, whereas those suffering from type 1 diabetes (T1DM) have lower BMD values [10]. More rapid bone loss after the onset of T1DM is believed to be the reason behind this finding.

Oral antidiabetic drugs, based on their mechanisms of action, are classified into several classes, namely Biguanides (e.g., metformin), Sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide), Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), (e.g., pioglitazone), Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is), (e.g., sitagliptin), Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-is), (e.g., dapagliflozin), and Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1Ras), (e.g., liraglutide). These drugs have different effects on glucose metabolism, insulin secretion, body weight, and lipid profile, which may in turn affect bone metabolism [11–16]. Some oral antidiabetic drugs, such as metformin, have shown beneficial effects on bone health, including an increase in BMD values and reduced fracture risk [17, 18]. Other oral antidiabetic drugs, such as thiazolidinediones are believed to affect the bone negatively [19, 20]. There is, however, no consensus over the effects of insulin or other oral antidiabetic drugs on bone health are controversial and scarce [21, 22]. The existing meta-analysis studies of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have not been able to provide a definite assumption in determining the safest treatment option with the least adverse events on bone health [23, 24]. Considering the global rise in the prevalence of both DM and osteoporosis, we have conducted a systematic umbrella review of the meta-analysis studies on the impact of anti-diabetic agents on bone health in patients with T2DM.

Material and methods

In this umbrella systematic review, we have collected all the relevant meta-analysis studies of the RCTs assessing the effects of anti-diabetic agents on bone health in T2DM patients. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Endocrine & Metabolism Research Institute- Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1401.155). The systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [25].

Search strategy

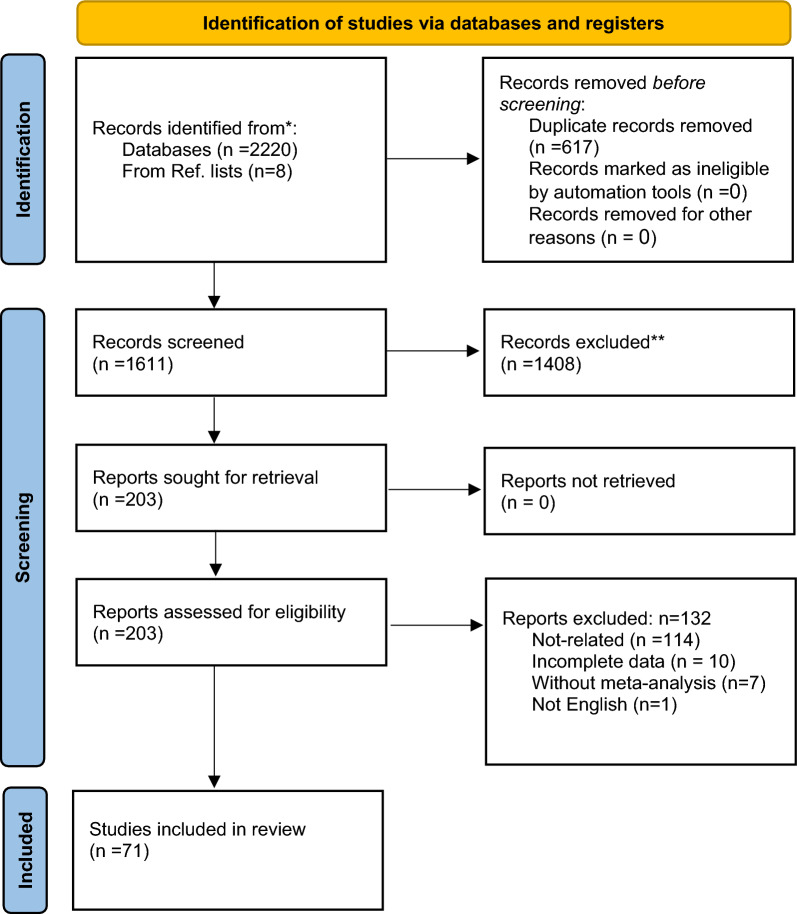

A medical information specialist and a review team collaboratively designed the electronic search strategies. We searched the English databases, namely Cochrane, Scopus, ISI Web of Sciences, PubMed, and Embase with the end date of 15 March 2023. The medical subject headings (MESH) “Diabetes mellitus”, “antidiabetic drugs”, “Bone biomarker”, and “Bone fracture, “bone health”, “Bone mineral density” and their equivalents were used for the search (Table S1). Additionally, a manual search was conducted to identify missing articles. The title, keywords, and abstract of these articles were then evaluated. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study review process

Study selection

All the relevant meta-analyses of RCTs conducted to assess the effect of the antidiabetic drugs (alone or in combination) on bone health in terms of their influence on biomarkers, bone density/mass (osteopenia, osteoporosis), or fracture compared with the placebo, or a control group were included. Observational meta-analyses, commentaries, and studies on nonmetabolic bone diseases such as Paget's disease were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The extracted data including the name of the first author, publication year, data collection, study design, study population, sample size (total, control, and treatment arm), intervention, quality assessment, and main outcomes was recorded in two separate Excel sheets. The results of the initial screening were entered into the EndNote software. After eliminating the duplicates, two reviewers evaluated the titles and the abstracts independently to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Thereafter, the full text of the remaining articles was evaluated. If an agreement between the two reviewers was not possible, a third reviewer was asked to decide.

The studies with low methodological quality were also highlighted in this step. “A Measurement Tool to Assess Multiple Systematic Reviews-2” (AMSTAR-2) and “Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE)” checklists were used to help with the methodological and evidence quality assessment, respectively [26, 27].

Results

General characteristics

Our search strategy yielded a total of 2220 potentially eligible studies published until 15 March 2023 in the selected electronic databases. A total of 2157 studies were excluded due to being irrelevant based on either the PICO or the inclusion criteria.

Seventy-one systematic reviews and meta-analyses were finally included in our umbrella systematic review; 8 out of which were retrieved through manual searching of the references of the included studies.

These RCTs were mainly conducted on individuals with T2DM, with some suffering from cardiovascular diseases (CVD), chronic kidney diseases (CKD), and heart failure (HF) as well T1DM or T2DM. which the majority of these studies consisted of patients with T2DM. All the studies were conducted on both male and female participants. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 80 years. The evaluated anti-diabetic drugs included SGLT-is, DPP-4is, TZDs, GLP-1RAs, Sulphonylureas, Metformin, Insulin, Voglibose (alpha-glucosidase inhibitor), Aleglitazar (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist) and Nateglinide (Meglitinide). The baseline characteristics, the main findings of the included studies, and their quality assessment results are demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included meta-analyses of clinical trials

| References | Design | Study population | Total (N) | Sex (F, M, B) | Mean Age (y) |

Included studies (N) | Intervention/control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture | ||||||||

| 1 | Adil et al. [72] |

Conference, RCTs |

T2DM | 22,437 | UN | NR | 17 | TZDs/placebo or Met or Sulfonylureas or other diabetic drugs |

| 2 | Arnott et al. [28] | RCTs | T2DM, CKD, HF | 74,550 | 11 | SGLT2 inhibitors | ||

| 3 | Arnott et al. [29] | RCTs | T2DM | 38,723 | B | 55–72 | 4 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 4 | Augusto et al. [30] | RCTs | T2DM |

136 096 participants (83 092 on SGLT2 inhibitors) |

B | Average 52.4 | 46 systematic reviews 175 RCT (2 fracture: 28,873 participants) | SGLT2/placebo or active comparators |

| 5 | Azhari et al. [73] |

Conference RCTs |

NR | NR | NR | NR | 14 | Pioglitazone vs. placebo |

| 13 | Pioglitazone vs. AHGs | |||||||

| 6 | Azhari et al. [74] |

Conference RCTs |

NR | 37,709/25,016 | B | NR | 79 |

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) Pioglitazone/placebo or other anti-hyperglycemic agents (AHG) |

| 7 | Azharuddin et al. [67] |

Conference RCTs |

T2DM | 8584 | NR | 54.30–72.60 | 7 |

DPP-4i/sulfonylureas as add-on therapy to metformin |

| 8 | Azharuddin et al. [31] | Network meta-analysis RCTS | T2DM | 32,343 | B | 51- 69 | 40 | SGLT2 inhibitors/Placebo or active control |

| 9 | Bai et al. [32] | RCTs | T2DM | 44,107 | B | 63.8 years | 6 | SGLT2 inhibitors/placebo |

| 10 | Chai et al. [34] | Network meta RCTs | T2DM | 165,081 | B | 57.68 yrs (SD: 5.08) | 177 | DPP-4i, GLP-1 RAs, or SGLT-2i/placebo or other antidiabetic agents [metformin (Met), insulin, sulfonylurea (SU), thiazolidinedione (TZD), andalpha-glucosidase inhibitor (AGI)] |

| 11 | Cao et al. [33] | RCTs |

With/ without T2DM, advanced CKD |

1114 | B | 61.9–70.1 yrs | 3 | SGLT2 inhibitors/placebo |

| 12 | Chen et al. [65] | RCTs | Diabetes, CKD, heart failure | 26,177 (1149 developed bone fractures: 591 (4.52%) in dapagliflozin, 558 (4.26%) in placebo) | B | NR | 3 | Dapagliflozin/placebo |

| 13 | Chen et al. [102] | RCTs | T2DM | 93,772 | B | 49.7–78.3 yrs | 87 | DDP-4Is (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, vildagliptin, alogliptin, linagliptin, trelagliptin, anagliptin)/placebo |

| 14 | Cheng et al. [65] | RCTs | T2DM | 23,372 | B | NR | 30 | SGLT2 inhibitors/placebo |

| 15 | Cheng et al. [35] | RCTs | T2DM |

39,795 (107 fracture in the GLP-1 RAs group and 134 in control group) |

B | NR | 38 | GLP-1 Ras/placebo and other anti-diabetic drugs |

| 16 | Clar et al. [75] | RCTs (7 DBRCT) | T2DM | 3092 | B | 46- 59 yrs | 8 | Adding pioglitazone to an insulin regimen vs. insulin alone (with/without another oral agents) |

| 17 | Doni et al. [103] | RCTs | T2DM | 2566 | B | > 70 yrs | 4 | DPP4Is/no treatment, placebo |

| 4611 | 3 | DPP4Is add on standard care/SU add on standard care | ||||||

| 18 | Donnan et al. [36] | RCTs | T2DM |

4687 treatments 2333 control |

NR | NR | 109 | SGLT2i/placebo, active comparators |

| 19 | Fu et al. [104] | RCTs (61: DBRCT) | T2DM | 62,206 | B | 49.7–74.9 yrs | 62 | DPP4I/placebo or other anti-diabetic medications |

| 20 | Gong et al. [37] | RCTs | CVD in with/without T2DM | 66,551 | B | > 18 yrs | 8 | SGLT2 inhibitors/placebo |

| 21 | Han et al. [80] | DBRCTs | T2DM | 9320 | B | 52–74 | 3 |

Aleglitazar/ placebo |

| 22 | Jiang et al. [66] | RCTs | T2DM | 18,891 | 55–78 | 5 | Dapagliflozin/placebo | |

| 23 | Kanie et al. [82] | Network meta RCTs | NR | 129,465 | NR | 31 | DDP4I, GLP-1, SGLT2I/placebo | |

| 24 | Kaze et al. [38] | RCTs |

Diabetic kidney disease T2DM |

10,577 (4 Studies, 6 data) |

B | Median: 65.2 | 5 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 25 | Kong et al. [105] |

updated meta-analysis RCTs |

T2DM | 111,539 | 49.4–71.6 | 110 | DDP4-i (sitagliptin, Liraglutide) | |

| 26 | Lee et al. [16] | RCTs | T2DM | 28,560 | B | 63 | 4 | SGLT-2i/placebo |

| 27 | Li et al. [40] | RCTs | CKD and DM, HF | 38,612 | B | 61.9–69 | 3 | SGLT2i/placebo or no treatment |

| 28 | Li et al. [41] | RCTs | T1DM | 4568 | 42–46 | NR | 5 studies (9 reported data) | SGLT2i placebo |

| 29 | Li et al. [42] | RCTs | T2DM | 20,895 | B | 42–80 | 27 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 30 | Liao et al. [76] | RCTs | pre-diabetes or T2DM | 5608 | B | 48–70 | 4 | Pioglitazone/placebo or other glucose-lowering agents |

| 31 | Lo et al. [43] | RCTs | DM with CKD | 2860 | B | 5 | SGLT2i/placebo | |

| 32 | Loke et al. [77] | RCT | T2DM | 13,715 | B | NR | 10 | Thiazolidinediones/control |

| 33 | Lou et al. [46] | RCTs | T2DM | 85,122 | B | NR | 78 | SGLT2i/placebo or other active treatment |

| 34 | Lu et al. [45] | RCTs | T1DM | 5384 | 38–56 | NR | 7 | SGLT-2i/placebo as add-on therapy on insulin |

| 35 | Lu et al. [46] | RCTs | HF with/without T2DM | 16,460 | B | Median age 60 yrs | 8 | SGLT-2i/placebo as add-on therapy insulin |

| 36 | Mabilleau et al. [68] | RCTs | T2DM | 4255 | B | 56.4 ± 1.9 yrs | 7 | GLP-1Ra/placebo or other antidiabetic agents |

| 37 | Mamza et al. [106] | RCTs | T2DM | 36,402 | B | 57.5 ± 5.4 yrs | 51 |

DPP-4i/placebo DPP-4i with an active comparator |

| 38 | Monami et al. [107] | RCTs | T2DM | 21,055 | B | NR | 28 | DPP-4i/placebo or active drugs |

| 39 | Mukai et al. [47] | RCTs | DM | 789 | B | > 18 | 4 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 40 | Munsaka et al. [69] |

Congress, DBRCTs |

T2DM | 16,933 | NR | NR | 20 | Alogliptin/metformin, sulfonylurea, thiazolidinediones, insulin, thiazolidinediones + metformin, thiazolidinediones + sulfonylurea, insulin + metformin, or standard of care |

| 41 | Pavlova, et al. [70] | RCTs | T2DM | 3172 | NR | NR | 6 | Pioglitazone/other antidiabetic drugs or placebo |

| 42 | Qian et al. [21] | RCTs | T2DM | 19,500 | NR | 51.6–60.7 | 25 | SGLT2i + Met/Metsulfonylurea, DPP-4i, SGLT2i, and GLP-1 |

| 43 | Qiu et al. [48] | RCTs | CHF/CKD/T2DM | 59,692 | NR | NR | 8 | SGLT2i/Placebo |

| 44 | Ruanpeng, et al. [49] |

Congress, RCTs |

T2DM | 12,464 | NR | NR | 20 | Canaglifl ozin/Placebo |

| Dapaglifl ozin/Placebo | ||||||||

| Empagliflozin ozin/Placebo | ||||||||

| 45 | Shrestha et al. [50] | RCTs | HF in with/without DM | 12,004 | B | > 18 | 6 | SGLT2i/Placebo |

| 46 | Sim et al. [51] |

Network Meta RCTs |

T2DM | 76,734 | B | NR | 15 | SGLT2i, Glitazones |

| 47 | Sinha [71] | prospective trials | T2DM with CVD or its high risk | 9213 | B | > 18 | 4 | Pioglitazone/non-pioglitazone |

| 48 | Su et al. [84] | RCTs | diabetic or non-diabetic population | 5912 | B | 45.9–59.5 | 8 | Liraglutide/Exenatide,Glimepiride,Sitagliptin, Orlistat or Placebo |

| 5294 | 10 | Exenatide/Insulin Glargine, Biphasic Insulin Aspart, Glimepiride, Insulin Lispro | ||||||

| 49 | Taha et al. [52] | DBRCT (Congress) | HF with/without DM | 95,594 | B | NR | 62 | SGLT2i/Placebo |

| 50 | Tang et al. [53] | Network meta RCTs | T2DM | 31,557 | B | Mean > 51.6 | 38 | Canagliflozin100, 300/Placebo |

| Dapagliflozin 1, 2.5, 5, 10/Placebo | ||||||||

| Empagliflozin 10, 25/Placebo | ||||||||

| 51 | Teo et al. [54] | Network meta RCT | DM |

SGLT1/2i: 14,996 SGLT2i: 43,333 |

NR | NR | 24 | Placebo vs SGLT1/2i |

| 52 | Toyama et al. [55] | RCTs | T2DM and CKD | 7363 | B | 63.5–68.5 | 8 | SGLT2i/placebo or active control |

| 53 | Tsai et al. [24] | Network meta-analysis RCT | T2DM | 19,1361 | B | 56.8 | 161 | GLP1-RA |

| Insulin | ||||||||

| Sulfonylurea | ||||||||

| Metformin | ||||||||

| SGLT-2i | ||||||||

| DPP-4i | ||||||||

| TZD | ||||||||

| 54 | Wang et al. [5] | RCTs | DM | 11,153 | B | ≥ 65/ < 65 | 2 | Ipragliflozin & Empagliflozin/Placebo |

| 55 | Wu et al. [3] | RCTs | T2DM |

Total: 42,886 [29,503 (regulatory submissions), 13,383 (scientific reports)] |

B | 48—68 | 5(regulatory submissions), 4 (scientific reports) | SGLT2i/controls |

| 56 | Yang et al. [58] | RCTs | T2DM | 1115 | B | ≥ 18 | 5 | SGLT2i mono therapy or add-on therapy/control |

| 57 | Yang et al. [23] | Network meta RCT | T2DM | 70,207 | B | 57.8 | 7 | Alogliptin/Placebo |

| 13 | Linagliptin/Placebo | |||||||

| 13 | Saxagliptin/Placebo | |||||||

| 20 | Sitagliptin/Placebo | |||||||

| 6 | Cildagliptin/Placebo | |||||||

| 58 | Younes et al. [59] | RCTs | HF with/without DM | 15,663 | B | 63–80 | 4 | SGLT2i/Placebo |

| 59 | Zelniker et al. [60] | RCTs | T2DM | 34,305 | B | Median 63.5 | 3 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 60 | Zhang et al. [86] | Network meta RCT | DM | 221,364 | B | < 65 | 117 |

Sulfonylureas, DPP-4i, inhibitors, bromocriptine-QR, meglitinides, SGLT2i, TZD, biguanides, GLP-1RA, insulin, a-glucosidase/Placebo |

| 61 | Zhang et al. [88] | RCTs + non-RCTs | T2DM | 138,690 | B | Middle‑aged, elderly | 7 | Insulin/oral anti‑diabetic |

| 62 | Zhang et al. [85] | RCTs, case- control study or cohort study | T2DM | 9047 | B | > 50–77 | 11 | Sulfonylurea/not sulfonylurea (5 studies: thiazolidinedione, 6 studies: metformin, 4 studies: insulin) |

| 63 | Zhang et al. [89] | Network meta RCT | T2DM | 49,602 | NR | NR | 54 | Semaglutide |

| Exenatide | ||||||||

| Liraglutide | ||||||||

| Lixisenatide | ||||||||

| Albiglutide | ||||||||

| Dulaglutide | ||||||||

| 64 | Zheng et al. [90] | Network RCT | T2DM | NR | B | NR | 20 | Hypoglycemic agents + metformin/uncontrolled with metformin |

| 65 | Zheng et al. [63] | RCTs |

CVD with/ without T2DM |

34,533 | NR | NR | 5 |

SGLT-2i/Placebo or drugs other than SGLT-2i |

| 66 | Zhu et al. [78] | RCTs | T2DM, IGT, Alzheimer | 24,544 | B | NR | 22 | TZD/Placebo or other oral antidiabetics |

| 67 | Zou et al. [64] | RCTs | HF with/without DM | 10,634 | B | 66.2–76.5 | 5 | SGLT2i/Placebo |

| 68 | Zuo et al. [79] | RCTs | T2DM, PCOs, MetS | 320 | B | 32–64 | 2 | Pioglitazone/Placebo |

| Bone biomarker | ||||||||

| 69 | Billington et al. [87] | RCTs |

T2DM, IGT, MetS, HIV, PCOS, healthy PM |

3743 | B | 56 yrs | 18 |

TZDs/metformin, sulfonylureas or placebo |

| 70 | Sun et al. [1] | RCTs | Abnormal glucose metabolism, PCOs | 932 | NR | NR | 10 | Pioglitazone/Placebo,Metformin,exenatide |

| 71 | Zuo et al. [79] | RCTs | T2DM, PCOs, MetS | 65 | B | 32–64 | 2 | Pioglitazone/Placebo |

| BMD | ||||||||

| 72 | Billington et al. [87] | RCTs |

T2DM, IGT, MetS, HIV, PCOS, healthy PM |

3743 | B | 56 yrs | 18 |

TZDs/metformin, sulfonylureas or placebo |

| 73 | Dutta et al. [88] | RCTs | NR | 421 | B | 47–66 yrs | 2 | lobeglitazone in intervention arm, and placebo/active comparator |

| 74 | Li et al. [42] | RCTs | T2DM | 1303 | B | 43–68 | 3 | SGLT2i/placebo |

| 75 | Loke et al. [77] | RCTs | T2DM | 94 | F | 32–68 | 2 | Thiazolidinediones/Placebo |

| 76 | Sun et al. [1] | RCTs | abnormal glucose metabolism, PCOs | 932 | NR | NR | 10 | Pioglitazone/Placebo,Metformin,exenatide |

| 77 | Zhu et al. [78] | RCTs | T2DM, IGT, Alzheimer | 24,544 | B | NR | 6 | TZD/Placebo or other oral antidiabetics |

| 78 | Zuo et al. [79] | RCTs | T2DM, PCOs, MetS | 467 | B | 32–64 | 3 | Pioglitazone/Placebo |

| References | Intervention | ROB Assessment (yes/no) | Effects model | MA metric | MA outcomes | Heterogeneity | GRADE Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg) | Duration (w) | Estimates | 95% CI | p Value | I2 (%) | p Value | ||||||

| Fracture | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Adil et al. [72] | UN | UN | N | Random | OR | 1.33 | 1.09–1.64 | 0.006 | UN | UN |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| 2 | Arnott et al. [28] | NR | RR |

Total: 1.07 T2DM: 1.06 CKD: 1.03 HF: 1.06 |

0.99–1.15 0.97–1.15 0.87–1.22 0.89–1.27 |

0.089 0.191 0.714 0.5 |

0 2.1 0 0 |

0.834 0.551 0.441 0.956 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|||

| 3 | Arnott et al. [29] | Empagliflozi (10, 25), Canagliflozi (100, 300), Dapagliflozin (10) | mean 139 | Y | Fixed | RR | Overall:1.08 | 0.98, 1.18 | 0.127 | 20.3 | 0.288 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 4 |

Augusto et al. [30] (2021) |

Dapagliflozin (2.5, 5, 10) Empagliflozin (10, 25), Canagliflozin (100, 200, 300) mg | 24–160 | Y | Fixed | RR | 0.67 | 0.42, 1.07 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.69 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Network meta-analysis | OR | 1.02 | 0.84, 1.23 | NR | 22.8 | NR | ||||||

| 5 | Azhari et al. [73] | NR | NR | y | NR | RR | 1.21 | 1.01–1.45 | 0.04 | 32% | NR |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| 1.08 | 0.73–1.59 | 0.70 | 15% | |||||||||

| 6 | Azhari et al. [74] | NR | NR | Y | Fixed | RR | 1.33 | 1.19–1.48 | < 0.00001 | NR | NR |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| 7 | Azharuddin et al. [67] | NR | 30–104 | UN | Fixed | OR | 1.45 | 0.82–2.57 | 0.21 | 0% | 0.86 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 8 | Azharuddin et al. [31] | Dapagliflozin (2.5, 5, 10), canagliflozin (100), Empagliflozin (5, 10, 25) mg |

24-51w (n = 14), 52-160w (n = 26) |

Y | Fixed | OR |

Vs. Placebo canagliflozin (0.57) dapagliflozin (0.58) empagliflozin (0.78) vs. active control Overall (1.01) canagliflozin (2.6) dapagliflozin (2.6) empagliflozin (3.7) |

0.12–1.90 0.13–2.00 0.23–2.80 0.83–1.23 0.69–16.00 0.52–22.00 1.0–27.00 |

0.91 | 27 | 0.01 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 9 | Bai et al. [32] | NR | 52–202 | Y | UN | HR | 1.07 | 0.98–1.17 | 0.152 | 0% | 0.899 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 10 | Chai et al. [34] | NR | 24–54 | Y | Random | OR |

DPP-4i vs. Insulin: 0.86 vs. Met: 1.41 vs. SU: 0.77 vs. TZD: 0.82 vs. AGI: 4.92 vs. Placebo:1.04 GLP-1RAs vs. Insulin: 1.05 vs. Met: 1.72 vs. SU: 0.94 vs. TZD: 1.00 vs. AGI: 5.99 vs. Placebo:1.27 SGLT-2i vs. Insulin:0.88 vs. Met: 1.44 vs. SU: 0.79 vs. TZD: 0.83 vs. AGI: 5.01 vs. Placebo:1.06 |

0.39–1.90 0.48–4.19 0.50–1.20 0.27–2.44 0.23–103.83 0.84–1.29 0.54–2.04 0.55–5.38 0.55–1.62 0.32–3.10 0.28–130.37 0.88–1.83 0.39–1.97 0.48–4.30 0.48–1.31 0.27–2.57 0.23–107.48 0.81–1.39 |

NR | NR | NR |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

| 11 | Cao et al. [33] | Empagliflozin (10, 25), Canagliflozin, Sotagliflozin (200, 400), Dapagliflozin (10) mg | 24–126 | Y | Random | RR | 0.78 | 0.42–1.46 | 0.44 | NR | NR |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 12 | Chen et al. [65] | 10 mg/d | Max. follow-up 4.2 years | Y | Fixed | OR | 1.06 | 0.94–1.20 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.58 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 13 | Chen et al. [102] | NR | 52 | Y | Fixed | OR | 1.01 | 0.90–1.12 | 0.92 | 0% | 1.00 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 14 | Cheng et al. [65] | Dapagliflozin (2.5, 5, 10), Empagliflozin (10, 25), Canagliflozin (100, 300) mg | > 24 | Y | Fixed | OR |

Pooled total: 0.86 Dapagliflozin Total: 0.90 2.5 mg: 0.31 5 mg: 2.44 10 mg: 1.10 Empagliflozin Total: 0.88 10 mg: 0.96 25 mg: 0.85 Canagliflozin Total: 0.76 100 mg: 1.11 300 mg: 0.58 |

0.70–1.06 0.48–1.68 0.03–3.04 0.70–8.46 0.58–2.09 0.70–1.12 0.73–1.27 0.64–1.12 0.45–1.28 0.62–1.98 0.29–1.17 |

0.16 0.74 0.32 0.16 0.77 0.31 0.77 0.25 0.3 0.73 0.13 |

0 0 0 3 10 3 0 23 0 0 0 |

0.66 0.55 0.99 0.38 0.35 0.41 0.81 0.26 0.48 0.66 0.88 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 15 | Cheng et al. [35] | NR | 24 weeks or more | Y | Fixed | OR |

Pooled total: 0.71 Liraglutide: 0.56 Lixisenatide: 0.55 Exenatide: 1.77 Dulaglutide: 0.76 Albiglutide: 0.84 Semaglutide: 0.87 Taspoglutide: 1.58 |

0.56–0.91 0.38–0.81 0.31–0.97 0.87–3.58 0.32–1.85 0.32–2.24 0.39–1.95 0.06–38.97 |

0.007 0.002 0.04 0.11 0.55 0.73 0.73 0.78 |

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 – |

0.95 0.96 0.54 0.62 0.82 0.54 0.73 NA |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 16 | Clar et al. [75] | 30–45 mg/d | 12–138 | Y | Random | RR |

F: 1.9 M: 1.1 |

– | – | – | – |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 17 | Doni et al. [103] | NR | 24–274 | Y | Random | RR | 1.15 | 0.52–2.53 | – | – | – |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 1.05 | 0.29–3.89 | |||||||||||

| 18 | Donnan et al. [36] |

Ertugliflozin (5, 15), Dapagliflozin (1, 2.5, 5, 10), Empagliflozin (10, 25), Canagliflozin (50, 100, 200, 300), Ipragliflozin (50), Tofogliflozin (10, 20, 40), Remogliflozin (100, 250, 500, 1000), Sotagliflozin (75, 200, 400) mg |

1–208 | Y | Random | RR |

Vs. placebo: 0.87 Vs. Met: 0.69 Vs. SU: 1.15 |

0.69–1.09 0.19–2.51 0.66–2.0 |

1.3 0 0 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

||

| 19 | Fu et al. [104] | NR | 12–160 | Y | Fixed | RR |

Total: 0.95 Alogliptin: 0.79 Linagliptin: 1.25 Saxagliptin: 1.03 Anagliptin: 4.16 Vildagliptin: 0.47 |

0.83–1.10 0.55–1.13 0.66–2.38 0.87–1.22 0.22–78.51 0.13–1.78 |

0.50 0.19 0.50 0.73 0.34 0.27 |

0 | 1.00 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 20 | Gong et al. [37] | Y | Random | RR | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.83 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

||

| 21 | Han et al. [80] | 150 µg/d | 10–156 | Random | OR | 1.19 | 0.67–2.09 | 0.56 | 12 | 0.32 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| 22 | Jiang et al. [66] | 10 mg | 6–219 | Y | Random | RR | 0.99 | 0.48–2.03 | 0.98 | 38 | 0.19 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 23 | Kanie et al. [82] | 38–168 | Y | OR |

DPP4i (OR 1.00) uncertain about the effect of GLP-1RA SGLT2i (OR 1.02) |

0.83–1.19 NA 0.88–1.18 |

NA 0.82 |

NA 0 |

0.96 0.96 |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

||

| 24 | Kaze et al. [38] |

Median 120 |

Y | Random | RR | 1.00 | 0.84–1.20 | 0 | 0.953 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

||

| 25 | Kong et al. [105] |

Sita: 100 mg Lira: 1.8 mg |

12–234 | Y | Fixed | OR | 0.97 | 0.88–-1.08 | 0 | 0.996 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| 26 | Lee et al. [16] | Dapagliflozin (10), canagliflozin (100, 300), empagliflozin (10, 25) | 115–202 | No | Random | RR | 1.02 | 0.92–1.14 | 0.70 | 0 | 0.89 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 27 | Li et al. [40] | Dapagliflozin (10), canagliflozin (100, 300) | > 116 | Y | Random | HR | 1.08 | 0.85–1.38 | 0.69 | 0 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 28 | Li et al. [41] | Dapagliflozin (5, 10), Sotagliflozin (200, 400) | 24–52 | Y | Mixed | RR | 0.84 | 0.56–1.25 | 0.0 | 0.936 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| 29 | Li et al. [42] | Dapagliflozin (2.5, 5, 10), canagliflozin (100, 300), empagliflozin (10, 25), ertugliflozin (5, 15) mg | 24–206 | Y | Fixed | RR | 1.02 | 0.81–1.28 | 0 | 0.776 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 30 | Liao et al. [76] | > 48w follow-up | Y | Fixed | RR | 1.52 | 1.17 to 1.99 | 0.002 | 39% | 0.18 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 31 | Lo et al. [43] |

eGFR: 30- < 60 RR |

0.81 | 0.31–2.10 | 0.66 | 50.61 |

⨁◯◯◯ Very Low |

|||||

| 32 | Loke et al. [77] | 48–192 | OR |

Total: 1.45, women: 2.23 men: 1.00 |

1.18–1.79 1.65–3.01 0.73–1.39 |

0.001 p < 0.001 0.98 |

27% 0% 0% |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

||||

| 33 | Lou et al. [46] | canagliflozin, dapagliflozin,empagliflozin | 12–296 | Y | Fixed | OR |

Total: 1.03 Canagliflozin: 1.17 Dapagliflozin: 1.02 Empagliflozin: 0.89 |

0.95–1.12 1.00–1.37 0.90–1.15 0.73–1.10 |

0.49 0.05 0.79 0.30 |

0 32 0 0 |

0.62 0.11 0.95 0.62 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 34 | Lu et al. [45] | Canagliflozin (100, 300), Dapagliflozin (5, 10),Sotagliflozin (75, 200, 400), Empagliflozin (2.5, 10, 25) | 12 -52 | Y | Random | RR | 0.89 | 0.65–1.21 | 0 | 0.702 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 35 | Lu et al. [46] | Varied doses | 36–202 | Y | RR | 1.02 | 0.77–1.36 | less than 20% |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|||

| 36 | Mabilleau et al. [68] | ≥ 24 w (mean 67.4 w) | Y | Random | OR | 0.75 | 0.28–2.02 | 0.569 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|||

| 37 | Mamza et al. [106] | 12–205, average 47.8 | Y | Mixed | OR |

DPP-4i/placebo (OR 0.82) DPP-4i/active comparator (OR 1.59) |

0.57–1.16 0.91– 2.80 |

0.9 0.9 |

0 0 |

0.992 0.932 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| 38 | Monami et al. [107] | at least 24 w | Y | Random | OR | 0.60 | 0.37–0.99 | 0.045 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|||

| 39 | Mukai et al. [47] | Varied | 4–24 | Y | Random | RR | 0.85 | 0.20–3.61 | 0.82 | 5 | 0.37 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 40 | Munsaka et al. [69] | NR | 12–216 | NR | NR | Incidence rate per 100 patients-years | − 0.32 | −0.68, 0.04 | NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 41 | Pavlova, et al. [70] | NR | 56–192 | N | Random | OR |

T:1.18 F: 2.02 M:0.82 |

T: 0.82–1.71 0.94–4.38 0.51–1.33 |

6 9 0 |

0.38 0.35 0.45 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

|

| 42 | Qian et al. [21] | NR | 24–208 | Y | MIX | OR | 0.97 | 0.71–1.32 | NR | 0 | 0.86 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 43 | Qiu et al. [48] | NR | NR | Y | Random | RR | 1.07 | 0.99–1.16 | NR | 0 | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 44 | Ruanpeng, et al. [49] | NR | ≥ 24 | NR | Random | RR | 0.66 | 0.37–1.19 | NR | 0 | NR |

⊕ ◯◯◯ Very Low |

| 0.84 | 0.22–3.18 | |||||||||||

| 0.57 | 0.20–1.59 | |||||||||||

| 45 | Shrestha et al. [50] | Canagliflozin (100, 300)/Sotagliflozin (200) mg/d/Dapagliflozin (10) | 4–188 | Y | Fixed | OR | 1.15 | 0.94–1.41 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.84 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 46 | Sim et al. [51] | NR | NR | Y | RR |

SGLT2: 1.05 Glitazone: 1.51 |

0.91 -1.19 1.03 -2.13 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

||||

| 47 | Sinha [71] | 15, 30, 45 | 26–208 | Y | OR |

Female: 2.05 Overall:1.31 |

Female:1.28–3.27 Overall:0.98–1,75 |

22.20 22.77 |

0.29 0.27 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

||

| 48 | Su et al. [84] | 0.6,1.2,1.8 | 16–104 | Y | Fixed | OR | 0.38 | 0.17, 0.87 | 0 | 0.864 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

|

| 2 mg QW/10 mcg BID | 12–52 | 2.09 |

1.03, 4.21 |

0 | 0.7445 | |||||||

| 49 | Taha et al. [52] | NR | NR | NR | Random | RR | 1.02 | 0.94–1.10 | NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ◯◯◯ Very Low |

| 50 | Tang et al. [53] | NR | 24–160 | Y | Random | OR | 1.15 | 0.71–1.88 | 0.95 | 22.8 | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 0.68 | 0.37–1.25 | |||||||||||

| 0.93 | 0.74–1.18 | |||||||||||

| 51 | Teo et al. [54] | NR | At least 12w | Y | NR | RR |

Placebo/SGLT12i: T2DM (T1DM):1.02 (1.43) Placebo/SGLT2i: T2DM (T1DM):0.97 (1.09) SGLT12i/SGLT2i: T2DM (T1DM):0.95 (0.76) |

0.80–1.31 0.88–1.07 0.73–1.24 |

NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 52 | Toyama et al. [55] | Canagliflozin dapagliflozin empagliflozin ertugliflozin | 1–201.6 | Y | Random | HR/RR | Overall:1.01 | 0.67, 1.52 | 0 | 0.64 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 53 | Tsai et al. [24] | NR | > 24w | Y | Random | OR | 0.7 | 0.5–0.96 | NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 0.78 | 0.39–1.56 | |||||||||||

| 0.79 | 0.56–1.12 | |||||||||||

| 0.96 | 0.54–1.73 | |||||||||||

| 1.05 | 0.87–1.26 | |||||||||||

| 1.22 | 0.98–1.53 | |||||||||||

| 1.4 | 0.97–2.04 | |||||||||||

| 54 | Wang et al. [5] | NR | NR | Y | Mixed | OR | 0.54 | 0.15–1.95 | 0.348 | 0 | 0.423 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 55 | Wu et al. [3] | N | Random Fixed | RR |

Regulatory submissions: 0·99 Scientific reports: 0·96 |

0·82–1.21 0·78–1·18 |

29% 21% |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

||||

| 56 | Yang et al. [58] | Canagliflozin 100 mg | < 24 w | Y | Random | RR | 1.60 | 0.48, 5.29 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.83 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 57 | Yang et al. [23] | NR | 12–206 | Y | NR | OR | 0.54 | 0.29–1.01 | NR | 0 | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 1.09 | 0.53–2.27 | |||||||||||

| 1.11 | 0.85–1.47 | |||||||||||

| 0.55 | 0.27–1.13 | |||||||||||

| 1.15 | 0.31–4.25 | |||||||||||

| 58 | Younes et al. [59] | NR | NR | N | Random | OR | 1.06 | 0.88–1.27 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.93 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 59 | Zelniker et al. [60] |

Empagliflozin (10, 25), Canagliflozin (100, 300), Dapagliflozin (10) |

115–201.6 | Y | Fixed | RR | 1.08 | 0.98, 1.20 | 0.11 | 42.1 | 0.18 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| 60 | Zhang et al. [86] | varied | ≥ 48 | Y | Random (dose–response) | RR |

DDP4i: omarigliptin 1.33, sitagliptin 1.29 vildagliptin 1.17 saxagliptin 2.04 linagliptin 0.9 alogliptin 0.76 trelagliptin 3.51 GLP-1 dulaglutide 0.91 exenatide 0.95 liraglutide 0.73 semaglutide 0.66 lixisenatide 0.92 albiglutide 0.29 TZD: rosiglitazone 1.2 pioglitazone 1.14 SU: Glipizide 0.67 gliclazide 0.75 glibenclamide 0.98 glimepiride 0.45 metformin 0.81 voglibose 0.03 insulin 0.68 nateglinide 1.35 SGLT2i: Canagliflozin 0.62 Dapagliflozine 0.9 Empagliflozin 1.19 Eurtagliflozin 2.47 |

0.21–8.24 0.27–6.47 0.23–6.16 0.38–12.09 0.18–4.66 0.12–4.87 1.58–13.70 0.17–4.88 0.15–5.96 0.14–3.92 0.13–3.41 0.2–6.3 0.04–0.93 0.21–6.83 0.31–4.25 0.12–3.74 0.05–9.46 0.22–4.25 0.09–2.17 0.14–4.56 0.0–0.11 0.12–3.86 0.24–7.55 0.13–3.08 0.16–5.14 0.24–5.89 0.16–9.95 |

< 0.05 | 44 |

0.64 0.84 0.58 0.88 0.96 0.90 0.77 0.83 0.40 0.65 0.64 0.94 0.35 0.86 0.42 0.32 0.73 0.90 0.93 0.62 0.34 0.38 0.55 0.72 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 61 | Zhang et al. [88] | 110–1056 | Random | RR | 1.13 | 0.92–1.39 | 0.252 | 84.1 | < 0.001 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

||

| 62 | Zhang et al. [85] | 40–624 | Y | Fixed | OR |

Sulfonylurea vs non-sulfonylurea 1.14 Sulfonylurea vs thiazolidinedione 0.90 Sulfonylurea vs metformin 1.25 Sulfoanylurea vs insulin 0.81 |

1.08–1.19 0.76–1.06 1.18–1.32 0.74–0.89 |

0.59 |

88.9 57.2 77.5 55.5 |

< 0.001 0.053 < 0.001 0.081 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

| 63 | Zhang et al. [89] | NR | > 26 | Y | Random | RR | 0.47 | 0.04, 3.63 | NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 0.17 | 0.03, 0.67 | |||||||||||

| 0.49 | 0.18, 1.13 | |||||||||||

| 0.39 | 0.05, 1.79 | |||||||||||

| 0.31 | 0.04, 1.77 | |||||||||||

| 0.31 | 0.06, 1.33 | |||||||||||

| 64 | Zheng et al. [90] | NR | 12–208 | Y | Random | OR |

Met + sul/Met 0.76 Met + DDP4i/Met 1.07 Met + SGLT2i/Met 0.77 Met + TZD/Met 1.38 |

0.25–3.12 0.36, 4.21 0.24, 3.58 0.39, 6.32 |

NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 65 | Zheng et al. [63] | NR | NR | Y | Fixed | RR | 1.11 | 0.99–1.23 | 0.08 | 24 | 0.26 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 66 | Zhu et al. [78] | Pioglitazone (15,30,45), Rosiglitazone (2,4,8) | 28–264 | Y | Fixed | OR |

T:1.41 F: 1.94 M:1.02 Pioglitazone:1.73 Rosiglitazone:2.01 |

T:1.23–1.62 F:1.60–2.35 M:0.83–1.27 Pioglitazone: 1.18–2.55 Rosiglitazone: 1.61–2.51 |

< 0.001 | 10 | 0.32 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 67 | Zou et al. [64] | NR | > 24 | Y | Random | RR | 1.07 | 0.90–1.26 | NR | NR | NR |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| 68 | Zuo et al. [79] | 30–45 mg/d | ≥ 16 | Y | Random | OR | 1.96 | 0.47–8.10 | 0.35 | 5 | 0.31 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| Bone biomarker | ||||||||||||

| 69 | Billington et al. [87] |

Rosiglitazone (4, 8) mg Pioglitazone (15, 30, 45) mg, balaglitazone (10–20) mg |

median trial duration 48 weeks | Y | Random | WMD |

CTX: 11% difference BSAP: 1% PINP: 3.7% Osteocalcin − 0.8% |

0.5, 21.5 − 5.6, 7.6 − 5.1, 12.5 − 5.2, 3.6 |

0.04 0.8 0.4 0.7 |

Sig Sig Sig Non- Sig |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 70 | Sun et al. [1] | 15–45 mg/d | > 12 | Y | Random | MD | − 7.66 | − 15.18, − 0.15 | 0.05 | 58 | 0.05 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| 71 | Zuo et al. [79] | 30–45 mg/d | ≥ 16 | Y | Fixed | MD | − 0.81 | − 2.93, − 1.31 | 0.45 | 0 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

|

| BMD | ||||||||||||

| 72 | Billington et al. [87] |

Rosiglitazone (4, 8) mg Pioglitazone (15, 30, 45) mg, balaglitazone (10–20) mg |

median trial duration 48 weeks | Y | Random | WMD |

Lumbar spine difference − 1.1% total hip − 1.0% forearm − 0.9% femoral neck − 0.7% total body − 0.3% |

− 1.6, − 0.7 − 1.4, − 0.6 − 1.6, − 0.3 − 1.4, 0.0 − 0.5, 0.0 |

< 0.0001) < 0.0001 0.007 0.06 0.08 |

0 19 0 56 0 |

0.8 0.3 0.8 0.02 0.6 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 73 | Dutta et al. [88] | lobeglitazone 0.5 mg/d | > 24 | Y | Random | MD |

Femoral neck % change: 0.07 |

− 0.19, -− 0.33 | 0.60 | 91 | 0.001 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

| 74 | Li et al. [42] | Dapagliflozin (10), canagliflozin (100, 300), ertugliflozin (5, 15) mg | 26–104 | Y | Fixed | WMD |

Total: 0.08 Spine: − 0.04 femoral neck: 0.29 total hip: 0.18 distal forearm: − 0.20 |

−0.09, 0.26 − 0.43, 0.35 − 0.13, 0.71 − 0.09, 0.45 − 0.60, 0.20 |

11.3 0.0 50.7 40.3 0.0 |

0.336 0.894 0.132 0.187 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

| 75 | Loke et al. [77] | 14–16 | WMD |

Lumbar spine: − 1.11 hip: − 1.50 |

– 2.08, − 0.14 – 2.34, – 0.67 |

0.02 p < 0.001 |

0 0 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

||||

| 76 | Sun et al. [1] | 15-45 mg/d | > 12 | Y | Fixed | MD |

Lumbar Spine − 1.58 femoral neck − 0.08 total hip − 0.66 Total body − 0.4 distal radius − 1.04 |

− 2.07, − 1.09 − 1.32, 1.17 − 1.38, 0.06 − 0.78, −0.03 −1.78, − 0.31 |

0.00001 0.9 0.07 0.03 0.005 |

8 68 49 16 0 |

0.37 0.01 0.08 0.31 0.75 |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

| 77 | Zhu et al. [78] | Pioglitazone (15,30,45), Rosiglitazone (2,4,8) | 28–264 | Y | Fixed | SMD |

Lumbar spine: − 0.47 Hip: − 0.35 Femoral neck: − 0.32 |

− 0.63, − 0.31 − 0.53, − 0.18 − 0.48, − 0.15 |

< 0.0001 < 0.0001 0.0002 |

0 0 0 |

0.57 0.76 0.72 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ High |

| 78 | Zuo et al. [79] | 30–45 mg/d | ≥ 16 | Y | Fixed | MD |

T: − 0.7 Lumbar Spine 0.0 femoral neck 0.0 total hip − 0.03 |

− 0.9, − 0.5 − 0.06, 0.06 − 0.06, 0.05 − 0.09, 0.03 |

< 0.001 0.98 0.87 0.41 |

0 0 0 48 |

0.67 NR NR NR |

⊕ ⊕ ◯◯ Low |

ROB: Risk of Bias; B: Both; F: Female; M: Male; UN: Unknown; NR: not reported; MA: meta-analysis; RCTs: randomized controlled trials; DBRCTs: double-blind controlled trials; SBRCTs: single-blind controlled trials, WMD: Weighted mean difference; SMD: Standardized mean difference; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; COTs: cross over trials, MetS: Metabolic syndrome; PM: Post-menopausal, CKD: Chronic kidney disease, NA: Not applicable, SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; CTX: C-terminal end of the telopeptide of type I collagen; BSAP: Bone specific alkaline phosphatase; PINP: procollagen type I N-propeptide

The quality of the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses was assessed using the AMSTAR-2 tool. Among the included studies, 22 were rated as “High”, 15 as “Moderate”, 20 as “Low”, and the remaining 14 studies as “Very Low” quality. Table 2 provides details on the AMSTAR-2 ratings. The GRADE rating demonstrated 27 of the studies to be based on “High”, 29 on “Moderate”, 12 on “Low”, and the remaining 3 studies on “Very Low” quality evidence. Table 1 includes data on the quality of the evidence for each individual study.

Table 2.

Results of assess the methodological quality of meta-analysis

| Refs. | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Summary AMSTAR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adil et al. [72] | N | PY | N | PY | N | N | N | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Arnott et al. [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Arnott et al. [29] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Augusto et al. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Azhari et al. [73, 74] | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Azhari et al. [32] | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Azharuddin et al. [67] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Azharuddin et al. [31] | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Bai et al. [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Billington et al. [87] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Cao et al. [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Chai et al. [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Chen et al. [102] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | LQ |

| Chen et al. [65] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Cheng et al [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Cheng et al. [81] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Clar et al. [75] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Doni et al. [103] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Donnan et al. [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Dutta et al. [88] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Fu et al. [104] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Gong et al. [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Han et al. [80] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Jiang et al. [66] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Kanie et al. [82] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Kaze et al. [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Kong et al. [105] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Lee et al. [16] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | MQ |

|

Li et al. [41] (2016) |

Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Li et al. [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Li et al. [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Liao et al. [76] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Lo et al. [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | HQ |

| Loke et al. [77] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Lou et al. [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Lu et al. [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Lu et al. [46] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Mabilleau et al. [68]) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | MQ |

|

Mamza et al. [106] (2016) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Monami et al. [107] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Mukai et al. [47] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | N | Y | Y | P Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | MQ |

| Munsaka et al. [69] | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | CLQ |

| Pavlova et al. [70] | Y | N | N | P Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | CLQ |

| Qian et al. [21] | Y | P Y | N | P Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | LQ |

| Qiu et al. [48] | Y | N | N | P Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CLQ |

| Ruanpeng et al. [49] | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | CLQ |

| Sim et al. [51] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Sinha [71] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | LQ |

| Shrestha et al. [50] | Y | Y | N | P Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | LQ |

| Su et al. [84] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | N | N | Y | P Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | CLQ |

| Sun et al. [22] | Y | N | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CLQ |

| Taha et al. [52] | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | CLQ |

| Tang et al. [53] | Y | P Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | Y | P Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | CLQ |

| Teo et al. [54] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | HQ |

| Toyama et al. [55] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | HQ |

| Tsai et al. [24] | Y | Y | N | P Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Tsai et al. [24] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | CLQ |

| Wang et al. [5] | Y | Y | N | P Y | N | Y | P Y | P Y | P Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | MQ |

| Wu et al. [3] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | LQ |

| Yang et al. [23] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Yang et al. [58] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Younes et al. [59] | Y | P Y | N | P Y | Y | N | N | P Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | CLQ |

| Zelniker et al. [60] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | MQ |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Y | Y | N | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | P Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Zhang Z et al. [85] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | HQ |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | P Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | CLQ |

| Zhang et al. (2021) | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Zheng et al. [62] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | P Y | P Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | HQ |

| Zheng, et al. [63] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | CLQ |

| Zhu, et al. [78] | Y | P Y | N | P Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | CLQ |

| Zou et al. [64] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LQ |

| Zuo et al. [79] | Y | Y | N | P Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | CLQ |

Y: Yes; N: No; PY: Partial yes; CLQ: Critically low quality; LQ: low quality; HQ: High quality; MQ: Moderate quality

We reported the results considering three distinct bone health parameters, namely fracture, bone mineral density (BMD), and bone biomarkers. The summary of the results is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the results

| Drug | Fracture (n) | Bone biomarker | BMD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric (n) | Refs. | Marker (n) | Refs. | Site (n) | Refs. | |

| SGLT-2i |

HR/RR No increase (28) OR No increase (11) |

HR/RR [2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 19, 22, 24, 26, 28–30, 32, 36, 39, 42, 44, 45, 47, 70, 72, 74, 76, 82, 87, 102–105] OR |

– |

WMD, or SMD ↓Total hip (5) ↓Lumbar Spine (4) ↓Femoral neck (3) ↓distal radius (2) ↓Total body (3) |

[10, 20, 48, 66, 67, 69] | |

| SGLT-1i |

WMD, or SMD ↑Total hip (1) ↓Lumbar Spine (1) ↑Femoral neck (1) ↓distal radius (1) ↑Total body (1) |

[30] | ||||

| DDP-4i |

RR, OR Total (14) varied (↓↑) ↓Alogliptin (4) ↓↑Sitagliptin (3) |

– | – | |||

| TZDs |

RR, OR ↑Total (12) ↑Pioglitazone (7) ↑Rosiglitazone(2) |

WMD: ↓BSAP (2), ↓OS (1), ↑CTX (1), ↑PINP (1) |

[10, 21, 51 | – | ||

| GLP-1 receptor agonists |

RR, OR ↓↑varied (6) uncertain effect (1) ↓Subclasses except Exenatide (3) ↓↑Exenatide (4) |

[25] |

– | – | ||

| Sulphonylureas |

RR, OR ↓ (4) |

[40, 45, 46, 107] | – | – | ||

| Metformin (alone or combination) |

RR, OR ↓ (3) |

[40, 45, 107] | – | – | ||

| Insulin |

RR, OR ↓ (3) |

[40, 45, 68] | – | – | ||

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor |

RR ↓ (1) |

[45] | – | – | ||

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist |

OR ↑ (1) |

[23] | – | – | ||

| Meglitinide |

RR ↑ (1) |

[45] | – | – | ||

Anti-diabetic agents and bone fracture

A total of 68 studies reported data on bone fracture. Among the included studies, 39 investigated the role of SGLT2i (one study; SGLT1i), nine discussed DPP-4i, eight meta-analyses were on TZDs, and seven studies were on GLP-1RAs. The AMSTAR-2 quality rating for 21 of the studies was “High”, 15 were marked as “Moderate”, 19 were considered “Low” quality, and the rest were described as “critically low” quality studies. According to the GRADE rating for the quality of evidence, 27 studies were “High”, and 29 were classified as “Moderate” quality evidence. Nine studies were considered as “Low”, and the remaining three studies were marked as “Very low” quality evidence.

SGLT-2i

The included studies demonstrated no or equivalent effect of the SGLT-2i drug consumption on the risk of developing bone fracture, ranging from HR/RR: 0.57–1.60, and OR: 0.54–0.15 [21, 24, 29–64]. In terms of specific drugs, Dapagliflozin was discussed in seven studies [31, 35, 44, 53, 63, 65, 66] having an RR (0.90–0.99) and OR (0.58–1.06). Canagliflozin was discussed in six studies [31, 35, 44, 53, 58, 63] having an RR (0.62–1.60) and OR (0.57–1.17); Empagliflozin was discussed in seven studies [31, 35, 44, 49, 53, 56, 90] having an RR (0.57–1.19) and OR (0.54–0.93). In one study, conducted as a network meta-analysis [62], the OR of combined metformin and SGLTi consumption in patients in whom monotherapy had failed with metformin was 0.77 (CI95% 0.24, 3.58). The overall heterogeneity for the included SGLT-2i studies was “Low”.

DPP-4i

The data for the effect of DPP-4i on fracture risk was inconclusive with RR ranging from 0.95 to 1.15 and OR ranging from 0.57 to 2.80 versus consumption placebo or other hypoglycemic agents [23, 24, 46–51, 65, 67–71]. One study [47] demonstrated an increased fracture risk following DPP-4i compared to Sulphonylureas (OR: 1.45, CI95% 0.82, 2.57). One network meta-analysis [68] showed the combination of DPP-4i and Metformin to be associated with an increase in fracture risk (OR: 1.07, CI 95% 0.36, 4.21). Four studies [23, 46, 48, 71] reported Alogliptin to decrease the risk of fracture (one study reported OR: 0.54, one study reported incidence rate per 100 patient-year: − 0.32, and two reported RR: 0.76, 0.79). Sitagliptin was discussed in three distinct studies [23, 46, 49], reporting contrasting results (OR: 0.55–1.29). The heterogeneity of the included studies was “Low”.

TZDs

All the studies assessing the effect of TZDs [24, 61, 62, 70–79] demonstrated an increase in fracture risk compared to placebo or other active comparators; RR from 1.08 to 1.9, and OR from 1.18 to 1.96. Four studies compared the TZDs on the fracture risk in different genders [70, 75, 77, 78], and reported an increased risk of fracture in women (RR: 1.9, and OR: 2.23, 2.02, 1.94 in women). Six studies focused on Pioglitazone [61, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76, 78, 79] and demonstrated its use to be linked with an increased risk of fracture (RR: 1.08–1.52, and OR: 1.18–1.96). One study assessed the fracture risk following Pioglitazone + insulin consumption versus sole intake of insulin [75] and found 0.8 increase in fracture risk for the former in women. The effect of Rosiglitazone was discussed in two studies [61, 78], demonstrating a 20–60% increase in fracture risk. In one network meta-analysis [62], the OR of combined metformin and TZDs in patients in whom monotherapy had failed with metformin was 1.38 (CI95% 0.39, 6.32). No significant heterogeneity was reported in studies analyzing the TZD effects. Aleglitazar, another peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist, was assessed in one study [80], in which its consumption was shown to increase the fracture risk (OR: 1.19, CI95% 0.67, 2.09).

GLP-1RAs

Focusing on GLP-1RAs, most studies pointed towards its risk reducing effect compared to placebo or other active comparator; OR: 0.70–0.95 [24, 61, 68, 81]. A single study, however, demonstrated an increase when compared with placebo, OR: 1.27 [34] whereas another study failed to determine any certain effects [82]. Three studies [61, 81, 83] confirmed a significant reduction in fracture risk with the consumption of the GLP-1 RA class (Semaglutide [RR: 0.47, 0.66, OR: 0.87], Liraglutide [RR: 0.49, 0.73, OR:0.56], Albiglutide [RR: 0.29, 0.31, OR: 0.84], Lixiseglutide [RR: 0.39, 0.92, OR: 0.55], and Dulaglutide [RR: 0.31, 0.91, OR: 0.76]. As for Exenatide, two studies [61, 83] reported reduced fracture risk (from 5 to 83%), whereas two others [81, 84] demonstrated an increase (OR: 1.77, 2.09).

Sulphonylureas

Sulphonylureas were discussed in four studies. Two of them [24, 85] showed contradictory effects on the fracture risk following the medication use (OR: 0.79, 1.14). One network meta-analysis [62] demonstrated a decrease in fracture risk when combining Sulphonylureas with Metformin (OR: 0.76, CI95% 0.25, 3.12). Another network meta-analysis of 117 RCTs comparing several Sulphonylurea drugs vs. placebo concluded that Glipizide, Gliclazide, Glibenclamide, and Glimepiride decreased the risk of fracture by 33%, 25%, 2%, and 55%, respectively [61].

Insulin

The fracture risk following insulin consumption was assessed in three separate studies [24, 61, 86]. Compared to oral anti-diabetic drugs, one study on 7 RCTs demonstrated a 13% (RR: 1.13) increase in the fracture risk [86]. Two network meta-analysis, one (with 117 RCTs) concluded an OR: 0.68 [61] and the other an OR:0.78 [24] for fracture risk reduction following insulin consumption.

Metformin

The fracture risk following Metformin consumption compared to placebo was discussed in two network meta-analysis studies [24, 61], with one showing an RR: 0.81, CI95% 0.14, 4.56, and the other demonstrating an OR: 0.96, CI95% 0.54, 1.73. The combination of metformin with other anti-diabetic agents are reported in previous sections [62].

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor

A network meta-analysis study [61] demonstrated Voglibose to be responsible for a 97% reduction in fracture risk compared with placebo (RR: 0.03, CI95% 0, 0.11).

Meglitinide

Nateglinide (the Meglitinide class) was discussed in one network meta-analysis study [61] and was associated with a 35% increase in the fracture risk (RR: 1.35, CI95% 0.24, 7.55).

Anti-diabetic agents and BMD

A total of seven studies pooling the data of 44 RCTs, including 31,504 individuals with abnormal glucose metabolism, T2DM, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, or Alzheimer, assessed the effects of anti-diabetic drugs on the BMD [22, 42, 77–79, 87, 88]. The AMSTAR-2 rating of their quality confirmed two as “high”, two as “moderate”, and the remaining as “critically low” quality. As for the GRADE classification, five studies were based on “High” quality evidence, and two were “Low”.

Except for one study evaluating SGLT-2i [42], all the studies were on TZDs (specifically Pioglitazone). While a single study showed Lobeglitazone [88] to increase the BMD values at the femoral neck (MD: 0.07 [CI95% − 0.19, − 0.33]), other TZD studies reduced the BMD values at different sites (total hip, lumbar spine, forearm, femoral neck, distal radius, total body). The former, however, combined data from two RCTs and had a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 91%, p-value: 0.6). Only one of these studies [42] compared the effect of SGLT-2i with placebo, reporting an increase in BMD values at total body (WMD: 0.08 [CI95% − 0.09, 0.26]), femoral neck (WMD: 0.29 [CI95% − 0.13, 0.71]), and total hip (WMD: 0.18 [CI95% − 0.09, 0.45]) but decreased values at the lumbar spine (WMD: -0.04 [CI95% − 0.43, 0.35]) and distal forearm (WMD: − 0.2 [CI95% − 0.60, 0.20]).

Anti-diabetic agents and bone biomarkers

Conclusively, only three studies, which pooled the data of 30 RCTs on 4740 individuals with abnormal glucose metabolism, T2DM, metabolic syndrome, or polycystic ovary syndrome, discussed the effects of anti-diabetic drugs on bone biomarkers [22, 79, 87]. The AMSTAR-2 quality ratings marked one study as “moderate” quality and two others as “critically low”. As for the GRADE classification, one study was considered to be based on “high” and others on “low” quality evidence.

The only drug class studied in this regard was TZDs. Two studies [22, 87] reported the decreasing effect of Pioglitazone on the bone-specific Alkaline Phosphatase (BSAP), (MD: − 0.81 [CI95% − 2.93, − 1.31], − 7.66 [CI95% − 15.18, − 0.15]). The other study [94] pooled the data of 18 RCTs, showing an increased effect on C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) (WMD: 11% [CI95% 0.5, 21.5]), BSAP (WMD: 1% [CI95% − 5.6, 7.6), procollagen type I N-propeptide (PINP) (WMD: 3.7% [CI95% − 5.1, 12.5]) and a decreasing effect on osteocalcin (WMD: -0.8 [CI95% − 5.2, 3.6). However, the heterogeneity of this study was significant.

Discussion

The current systematic umbrella review summarized the evidence of meta-analysis studies assessing the impact of anti-diabetic agents on bone health outcomes in patients with diabetes. As it could be seen in Table 1, the majority of the included studies were on T2DM individuals and only two were specifically conducted on T1DM patients [41, 45]. The comparison of the findings, however, revealed the effect of the anti-diabetic agents on the bone to be irrespective of the type of diabetes and specifically related to the mechanism of action of the medication.

A total of 68 studies assessed bone fractures. The 42 studies on various medications from the SGLT2i group showed no or equivalent effect on the risk of fracture. This is while SGLT2i is believed to enhance bone resorption and fracture risk through stimulating the tubular reabsorption of phosphate and subsequently increasing parathyroid hormone (PTH) concentrations [89]. Furthermore, serum PTH increases the concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), which per se promotes bone loss. Moreover, hyponatremia, one of the well-known side effects of this medication class, can also increase the risk of osteoporosis and fracture through arginine vasopressin and its negative effects on osteoblasts [90]. In line with this finding, several other studies have also supported the association between certain SGLT2is (canagliflozin) and increased fracture risk, pointing out treatment with this group to contribute to higher CTx (23–37%) and PTH, but lower 25-OH vitamin D concentrations [91, 92]. In this regard, a pooled analysis of 10 trials suggested that the increased risk of fracture following canagliflozin treatment only occurs in the presence of other possible risk factors such as older age, a prior history/risk of cardiovascular disease, lower baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate or higher diuretic use [93]. Not all studies, however, confirm this finding [53].

Theoretically, DPP-4is and GLP-1 RAs have similar effect on the bone as they both increase the GIP and GLP-1 levels. Many of the studies on the GLP-1Ras class reported the agent to reduce the fracture risk. This is because the GLP-1 is believed to increase bone density through stimulating osteoblast proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, their effects only appear after 52 weeks of treatment [83, 94]. DPP-4is, on the other hand, are believed to influence the activity of osteoclasts directly through modulating not only GLP-1 and GIP but also neuropeptide Y (NPY) and substance P [23]. From among the studies on DPP-4i, either consumed alone or in combination with other hypoglycemic agents, Alogliptin (4 studies) was the only oral agent to be linked with reduced fracture risk. The others reported contracting findings despite the low heterogeneity of the included studies. These findings corroborate with the Bayesian meta-analyses performed in this regard [61]. The reason behind the contradictory effect of different DPP-4is on bone fracture could be their divergent active metabolites and molecular structures and therefore discrepancies in their pharmacokinetic profiles, which can affect the pathways of bone metabolism and bone turnover differently [23, 95].

This is while the thirteen meta-analyses on TZDs supported the consumption of these anti-diabetic agents, regardless of being used alone or in combination with insulin or metformin, to be associated with a significant increase fracture risk. No significant heterogeneity was reported in the studies analyzing the TZD effects. Our findings illustrated the effects of the oral agents from the sulphonylurea class as well as insulin on the fracture risk to be controversial. This is while sulphonylureas are considered to have a positive effect on bone through enhancing the secretion of IGF-1 and reducing the levels of CTx, a marker of osteoclast activity. Animal studies have also shown these medications promote the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts by activating the PI3K/ATK pathway. This results in increased ALP and osteocalcin mRNA activity, which can induce bone formation [96]. The intervention time of the included sulphonylurea studies ranged from 40 to 624 weeks [22, 45, 46, 86]. Previous studies, however, had stressed that, like GLP-1Ras, at least 52 weeks are needed for the bone effects of the medications from the sulphonylurea class to occur [97]. The drug, however, can increase the fracture risk through causing hypoglycemic attacks and falls.

It should be added that while a network meta-analysis study linked Voglibose (alpha-glucosidase inhibitor) with reduced fracture risk, others have suggested Nateglinide (Meglitinide) and Aleglitazar (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist) to have an opposite effect. The main reason behind the controversial results of these studies is the need for long follow ups to accurately assess the effect of these hypoglycemic agents on the fracture risk. Other reasons for such different observations could be the variations noted in the length of intervention, dosage, participants’ characteristics and lifestyle habits, and even the geographical latitudes of the study sites, as a long list of variables are linked with fracture. Moreover, some of these studies were conducted in Europe whereas others were from Japan and other parts of the world. This is while the incidence of fracture is significantly different in various parts of the world, mainly because of the diversity in the genetic profile and lifestyle, complicating the interpretation of the results [98, 99]. On the other hand, hypoglycemia and increased risk of falls is believed to be the main reason behind the increased risk of fracture associated with certain hypoglycemic agents such as sulfonylureas. The incidence of hypoglycemia or glycemic control were not recorded in the included studies, making it impossible to determine the real reason behind our findings.

BMD is another determinant of bone health and a powerful predictor of fracture risk. The evidence behind the influence of hypoglycemic agents on bone mass is limited [22, 42, 77–79, 87, 88]. Except for one study on SGLT-2i [42], the remaining seven studies were on TZDs. From among the latter studies, Lobeglitazone [88] was associated with an increase in BMD values at femoral neck, whereas other TZD studies were linked with a decrease in the BMD values at different sites. It was mainly concluded that the TZD-mediated decline in BMD values were not the main reason for the increased fracture risk, stressing on the microarchitecture changes at cortical sites as the culprit. No significant decline was noted in the cortical sites compared with the trabecular regions. While the increased fracture risk was mainly noted following long-term treatments (> 2 years), the meta-analyses did not have sufficient power to detect small changes in BMD before and after 6 months of treatment with only three were extended beyond one year.

Only three studies assessed the effects of anti-diabetic drugs (only TZD) on bone biomarkers. However, due to inadequate evidence, such interpretations should be made with caution. One of these studies documented the decreasing effect of TZD on BSAP, which is a bone formation marker. This is in line with other studies suggesting long-term TZD consumption to be associated with BMD decline. This is while another study of 18 RCTs showed TZD to increase both bone resorption (CTx) and formation markers (BSAP, PINP) while decreasing osteocalcin, another bone formation marker. In addition to high heterogeneity, the limited number of studies made the subgroup analysis to assess the real effect of this medication class on promoting the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells challenging. This is while the effect of TZDs on the induction of osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis is well-known [100, 101]. The differences in the study period along with the relatively long differentiation periods and lifespan of these cell types could be the reason behind such controversial findings.

Our systematic review had several limitations. The main limitation was the heterogeneity of the meta-analyses in terms of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, studied populations, study protocol and intervention durations. Considering the low incidence of fracture in certain populations, long follow ups are needed to accurately estimate the fracture risk. Moreover, the limited number of studies on certain hypoglycemic agents made subgroup analysis and thus the interpretation of the results difficult. It should also be added that some of the included meta-analyses had a low and even critically low quality; we, however, did not exclude them as it would have made the final analysis challenging. On the other hand, the large population studied in the included research as well as the inclusion of both traditional and network meta-analysis provided us with the opportunity to study the direct and indirect effect of several anti-diabetic medication on bone health. To our knowledge this is the most comprehensive review performed in this field to date.

Conclusions

The present review has observed varied results on the association between the use of anti-diabetic drugs and DM-related fracture risk. It could however be concluded that when deciding upon the DM treatment options, the clinical efficacy of various anti-diabetic drugs must be weighed against their benefits and risks on organs such as bones in each patient. For instance, despite lack of clinical studies, DPP-4i seems be a safer option for diabetic patients at risk of fracture. TZDs, on the other hand, should be avoided in these individuals.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Examples of the search strategy in the searched web databases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR-2

Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews-2

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- BSAP

Bone-specific Alkaline Phosphatase

- BTMs

Bone turnover markers

- CTx

C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- MESH

Medical subject headings

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

- SGLT-is

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

- DPP-4is

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

- GLP-1Ras

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

- TZDs

Thiazolidinediones

Author contributions

PKH and FF-R: methodology, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; OT-M: supervision, data curation, methodology, validation, writing, reviewing, and editing; SMHZ-G: methodology, data curation, and reviewing; PKH: methodology, data curation, reviewing and editing; MM, SHE, BL: data curation, reviewing, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences & health services grant numbered 1401-4-221-64821. The funder had no role in any part of study, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by Research Ethics Committees of Endocrine & Metabolism Research Institute- Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1401.155).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pouria Khashayar and Farid Farahani Rad have equally contributed as first authors. Ozra Tabatabaei-Malazy and Patricia Khashayar have equally contributed as correspondance authors.

Contributor Information

Ozra Tabatabaei-Malazy, Email: tabatabaeiml@gmail.com.

Patricia Khashayar, Email: patricia.kh@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183: 109119. 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert MP, Pratley RE. The impact of diabetes and diabetes medications on bone health. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(2):194–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu B, Fu Z, Wang X, Zhou P, Yang Q, Jiang Y, et al. A narrative review of diabetic bone disease: characteristics, pathogenesis, and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1052592. 10.3389/fendo.2022.1052592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HS, Hwang JS. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus and antidiabetic medications on bone metabolism. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20(12):78. 10.1007/s11892-020-01361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Zheng L, Theopold J, Schleifenbaum S, Heyde C-E, Osterhoff G. Methods for bone quality assessment in human bone tissue: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2022;17(1):174. 10.1186/s13018-022-03041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenblatt MB, Tsai JN, Wein MN. Bone turnover markers in the diagnosis and monitoring of metabolic bone disease. Clin Chem. 2017;63(2):464–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong L, Liu D, Wu F, Wang M, Cen Y, Ma L. Correlation between bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in patients undergoing long-term anti-osteoporosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Sci. 2020;10(3):832. 10.3390/app10030832. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajabi M, Ostovar A, Sari AA, Sajjadi-Jazi SM, Mousavi A, Larijani B, et al. Health-related quality of life in osteoporosis patients with and without fractures in Tehran. Iran J Bone Metab. 2023;30:37–46. 10.11005/jbm.2023.30.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohi YH, Golestani A, Panahi G, Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Khalagi K, Fahimfar N, et al. The association between anti-diabetic agents and osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and osteosarcopenia among Iranian older adults; Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) program. Daru. 2023. 10.1007/s40199-023-00497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuominen JT, Impivaara O, Puukka P, Rönnemaa T. Bone mineral density in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(7):1196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackuliak P, Kužma M, Payer J. Effect of antidiabetic treatment on bone. Physiol Res. 2019;68(Suppl 2):S107–20. 10.33549/physiolres.934297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalaitzoglou E, Fowlkes JL, Popescu I, Thrailkill KM. Diabetes pharmacotherapy and effects on the musculoskeletal system. Diab/Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(2): e3100. 10.1002/dmrr.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhury A, Duvoor C, Reddy Dendi VS, Kraleti S, Chada A, Ravilla R, et al. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:6. 10.3389/fendo.2017.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlén AD, Dashi G, Maslov I, Attwood MM, Jonsson J, Trukhan V, et al. Trends in antidiabetic drug discovery: FDA approved drugs, new drugs in clinical trials and global sales. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12: 807548. 10.3389/fphar.2021.807548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yen FS, Hsu CC, Wei JCC, Hou MC, Hwu CM. Selection and warning of evidence-based antidiabetic medications for patients with chronic liver disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9: 839456. 10.3389/fmed.2022.839456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DSU, Lee H. Adherence and persistence rates of major antidiabetic medications: a review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2022;14(1):12. 10.1186/s13098-022-00785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Yu L, Ye Z, Lin R, Sun AR, Liu L, et al. Association of metformin use with fracture risk in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;13:1038603. 10.3389/fendo.2022.1038603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang LX, Wang GY, Su N, Ma J, Li YK. Effects of different doses of metformin on bone mineral density and bone metabolism in elderly male patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(18):4010–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonough AK, Rosenthal RS, Cao X, Saag KG. The effect of thiazolidinediones on BMD and osteoporosis. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4(9):507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecka-Czernik B. Bone loss in diabetes: use of antidiabetic thiazolidinediones and secondary osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2010;8(4):178–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian BB, Chen Q, Li L, Yan CF. Association between combined treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors and metformin for type 2 diabetes mellitus on fracture risk: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(12):2313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun T, Yan T, Zhao Y, Chen A. Pioglitazone decreased bone mineral density and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(6):e701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J, Huang C, Wu SS, Xu Y, Cai T, Chai SB, et al. The effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors on bone fracture among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0187537. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai WH, Cheng KH, Cheng YT, Tsai MC, Kong SK, Chien MN, et al. Risk of fracture caused by anti-diabetic drugs in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;192: 110082. 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358: j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adil M, Ghosh P, Venkata SK, Raygude K, Gaba D, Kandhare AD, et al. Effect of anti-diabetic drugs on risk of fracture in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a network meta-analytic synthesis of randomized controlled trials of thiazolidinediones. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A526. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.724. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnott C, Fletcher RA, Neal B. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, amputation risk, and fracture risk. Heart Fail Clin. 2022;18(4):645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnott C, Li Q, Kang A, Neuen BL, Bompoint S, Lam CSP, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(3): e014908. 10.1161/JAHA.119.014908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augusto GA, Cassola N, Dualib PM, Saconato H, Melnik T. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: an overview of 46 systematic reviews. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(10):2289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azhari H, Haig C, Dawson J. Pioglitazone and risk of fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4:725. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azhari H, Haig C, Dawson J. Thiazolidinediones and risk of bone fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Scott Med J. 2018;63(1):66. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azharuddin M, Sharma M. A meta-analytic synthesis of DPP4 inhibitors compared to sulfonylureas as add-on therapy to metformin and risk of fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Osteoporosis Int. 2022;32(Suppl 1):S387. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azharuddin M, Adil M, Ghosh P, Sharma M. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and fracture risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic literature review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;146:180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]