Abstract

BACKGROUND

A ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt is an alternative to a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt for managing hydrocephalus, especially when VP shunt insertion is not feasible. Despite its decline in use, the VA shunt remains vital for certain patients. This report highlights a rare complication of bilateral vocal cord paralysis following VA shunt insertion for hydrocephalus secondary to subarachnoid hemorrhage.

OBSERVATIONS

A woman in her 60s with a history of hypertension and giant liver cysts developed hydrocephalus after a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Because of her abdominal anatomical problems, VA shunt insertion assisted by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was chosen. Postoperatively, she experienced sudden dyspnea and upper airway stridor, diagnosed as bilateral vocal cord paralysis, necessitating an emergency tracheostomy. Gradual improvement was noted over the following month.

LESSONS

Bilateral vocal cord paralysis can be a potential complication of TEE-assisted VA shunt procedures. To mitigate this risk, preoperative assessments of vocal cord function and swallowing are recommended. Alternatives to TEE, such as fluoroscopy or smaller probes, can be considered for patients with risk factors, including severe subarachnoid hemorrhage and prolonged intubation.

Keywords: hydrocephalus, transesophageal echocardiography, ventriculoatrial shunt, vocal cord paralysis

ABBREVIATIONS: CT = computed tomography, ICA-PCoM = internal carotid artery–posterior communicating artery, TEE = transesophageal echocardiography, VA = ventriculoatrial, VP = ventriculoperitoneal, VPL = ventriculopleural.

A ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt is a type of cerebrospinal fluid shunt used for hydrocephalus. This shunt is particularly suitable for patients who cannot receive a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt due to factors such as intra-abdominal pathologies, infection, or technically challenging abnormal anatomy inadequate for VP shunt insertion.1 Although several reports have revealed that both VP shunts and VA shunts show no significant differences in procedure revisions, infections, and shunt-related mortality,2 the widespread preference for the simplicity and efficacy of the VP shunt has led to a decline in the use of VA shunts.3 Consequently, there have been few recent reports on VA shunts, especially regarding their complications. In this report, we describe a rare case of bilateral vocal cord paralysis following VA shunting for hydrocephalus after subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Illustrative Case

A woman in her 60s with a history of hypertension and giant liver cysts was brought to our hospital with a sudden onset of headache and loss of consciousness. On arrival, her Glasgow Coma Scale score was E1V1M4. Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage with hydrocephalus (Fig. 1A), and cerebral angiography showed an aneurysm in the left internal carotid artery–posterior communicating artery (ICA-PCoM), leading to a diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a ruptured aneurysm, classified as World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies grade V. The patient underwent intubation, ventricular drainage for hydrocephalus, and coil embolization for the ruptured ICA-PCoM aneurysm. Intensive care was continued, and her neurological condition improved. The ventricular drain was removed on the 9th day, and she was extubated on the 13th day. She then regained her ability to speak and began walking and swallowing training.

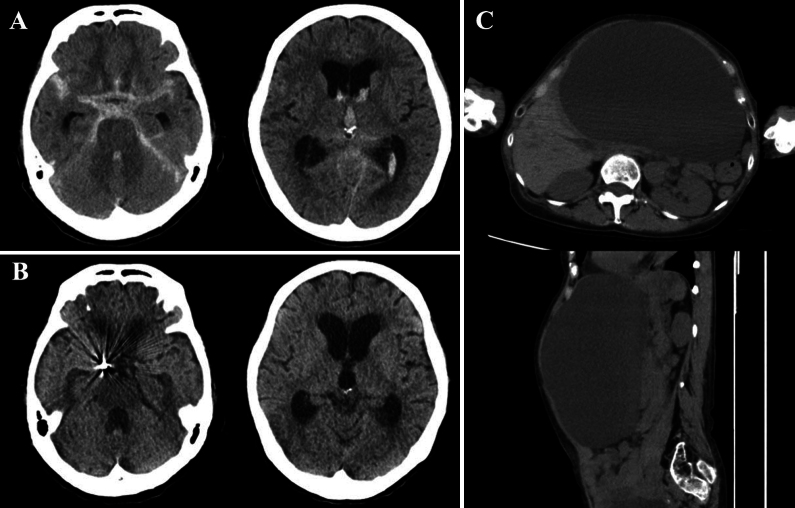

FIG. 1.

A: Initial CT scans showing a subarachnoid hemorrhage. B: CT scans on day 60 showing enlarged ventricles and a diagnosis of secondary hydrocephalus. C: CT scans showing giant liver cysts.

Subsequent observation revealed hydrocephalus caused by the subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 1B). The liver cysts (Fig. 1C) were asymptomatic and showed no signs of infection. However, due to their large size, there was concern that they could be injured during VP shunt placement. This, along with the potential need for future abdominal surgeries, led to the decision to perform VA shunt insertion instead. Although a ventriculopleural (VPL) shunt was considered as an option, the VA shunt was chosen because of our greater experience. Furthermore, recent literature has reported a higher rate of complications with VPL shunts, including a 16% incidence of pleural effusion and a 54% revision rate.4 Given these factors, the VA shunt was considered the more suitable choice in our case. VA shunt insertion was performed on the 62nd day. To determine an optimal location and guide the atrial catheter, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE; Philips EPIQ7G Ultrasound, tube outer diameter 15 mm × 12 mm) was used in addition to intraoperative fluoroscopy.

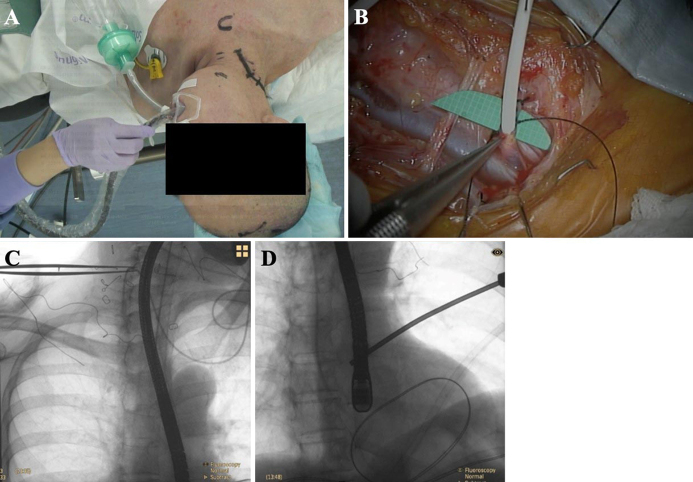

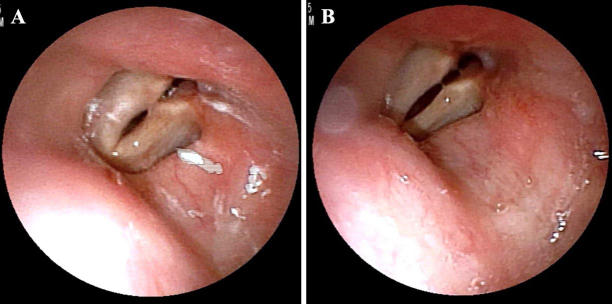

After intubation and induction of general anesthesia, the patient was placed supine with her head turned to the left. Then, the TEE probe was inserted by the anesthesiologist (Fig. 2A). The right anterior horn puncture was performed, and a shunt catheter was inserted subcutaneously into the facial vein. To ensure direct visual insertion of the distal catheter into the internal jugular vein, open dissection was performed instead of a percutaneous catheter technique. The right internal jugular vein and facial vein were exposed without injury to the superior laryngeal and the vagus nerves (Fig. 2B). The distal atrial catheter was placed in the right atrium with the guidance of intraoperative fluoroscopy and TEE (Fig. 2C and D). Postoperatively, the patient was extubated, and her respiratory status was stable. However, 3 days after VA shunt insertion, she suddenly developed dyspnea and upper airway stridor. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy revealed that the bilateral vocal cords were fixed (Fig. 3), and a diagnosis of bilateral vocal cord paralysis was made. An emergency tracheotomy was performed to secure the airway. One month after VA shunt insertion, her vocal cord paralysis gradually improved, and she was able to speak with a speech cannula.

FIG. 2.

A: Intraoperative image showing insertion of the TEE probe. B: The left internal jugular vein and facial vein were exposed without injuring the superior laryngeal nerve or vagus nerve, and a catheter was inserted into the facial vein. C and D: The combination of fluoroscopy and TEE allowed us to more precisely locate the distal atrial catheter.

FIG. 3.

Results of fiberoptic laryngoscopy: vocal cords when not speaking (A) and vocal cords when vocalizing (B).

Informed Consent

The necessary informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

We report a case of bilateral vocal cord paralysis on the 3rd day after a TEE-assisted VA shunt insertion for hydrocephalus secondary to severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. An emergency tracheostomy was performed, and the patient’s vocal cord paralysis gradually improved.

Bilateral vocal cord paralysis causes symptoms such as wheezing, hoarseness, and dysphagia. This severe complication can lead to dyspnea and respiratory failure, depending on the position of the fixed vocal cords. Most causes are iatrogenic, such as injury from cardiovascular surgery, thyroid surgery, multiple tracheal intubations, and nasogastric tube placement.5 Neurological diseases and idiopathic conditions are also known causes, and a combination of these factors can contribute to this complication. Airway management needs to be promptly evaluated, and if necessary, a tracheostomy should be performed. It has been reported that more than 30% of patients required a tracheostomy.6

In the present case, there was no obvious damage to the superior laryngeal or vagus nerves during exposure of the internal jugular vein and the facial vein during the surgical procedure. The mechanical stimulation of the larynx by intraoperative TEE was considered to be the main cause of the vocal cord paralysis.

TEE is known to be useful during VA shunt procedures. It facilitates visualization of the distal atrial catheter and more accurate placement into the atrium.7–11 It has been reported that the mean operative time was shorter in the group in which TEE was used than in the group in which fluoroscopy alone was used (144 versus 224 minutes).1 On the other hand, complications of bilateral vocal cord paralysis have not been reported.1

Vocal cord paralysis associated with TEE after cardiovascular surgery is a relatively well-known complication.12 The use of TEE was considered a potential confounding factor for laryngeal trauma, and emergency operations and blind placement of TEE probes are risk factors, while laryngeal fiberscopy-guided TEE reduces vocal cord injury.13 Furthermore, to perform a VA shunt insertion, exposure of the internal jugular vein and its branch, the facial vein, is needed, and the head must be rotated. This can make insertion of the TEE probe more challenging, potentially increasing mechanical stimulation of the larynx. In published papers on the use of TEE in VA shunt insertion,1, 9, 14 placement of the TEE probe was consistently done before head positioning. However, in our case, the TEE tube was placed after head positioning, which may explain the unusual complication of bilateral vocal cord paralysis. To prevent this, TEE probe placement should be done before head rotation, potentially with laryngeal fiberscopy guidance.

Bilateral vocal cord paralysis due to mechanical irritation of the larynx associated with the intraoperative use of TEE is considered similar to the pathogenesis of nasogastric tube syndrome. Nasogastric tube syndrome causes vocal fold paralysis due to ischemia and inflammation from infection of the posterior cricoid cartilage, which is caused by pressure and friction from the nasogastric tube. This leads to paralysis and necrosis of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.12, 15, 16 Vocal cord paralysis is known to be transient, often recovering within 1 day to 3 months, during which time a tracheostomy may be necessary.17 Even a thin nasogastric tube of about 10 Fr can cause this syndrome, though it is more likely with thicker tubes used for prolonged periods.18–20

In our case, a tracheal tube (7 Fr, 2.3 mm), a nasogastric tube (14 Fr, 4.7 mm), and a TEE probe (15 mm) were inserted into the larynx during the VA shunt insertion, totaling 22 mm of prostheses. Preoperative CT showed that the distance between the thyroid cartilage and the anterior margin of the fifth cervical vertebra was 29 mm. Thus, the total long diameter of these devices occupied 75% of the space around the vocal folds. The pressure from the fixed tracheal and nasogastric tubes, combined with the friction from the TEE probe, which moved with each manipulation, likely caused mechanical irritation to the larynx, resulting in bilateral vocal cord paralysis. The patient’s vocal cord paralysis gradually improved after the operation, which was also consistent with the characteristics of nasogastric tube syndrome.

Furthermore, this patient had multiple risk factors for vocal cord paralysis. Upon emergency presentation, the patient had a severe subarachnoid hemorrhage with significantly impaired consciousness, necessitating emergency tracheal intubation in the emergency department. After stabilization of the intracranial condition and during recovery of her swallowing function, she was reintubated for a VA shunt insertion 49 days after extubation. The combination of prolonged tracheal intubation for more than 1 week after severe subarachnoid hemorrhage, repeated tracheal intubation within 2 months, long-term nasogastric tube placement, and intraoperative TEE could have led to severe postoperative vocal cord paralysis in our case.

When planning a VA shunt insertion with TEE assistance for secondary hydrocephalus following severe subarachnoid hemorrhage, additional preoperative risk assessment may be necessary. This includes observation of the vocal folds with laryngeal fiberscopy and evaluation of swallowing function. If the preoperative evaluation suggests compromised laryngeal function, alternatives such as fluoroscopy or the use of a smaller probe are recommended.11 By preoperatively measuring the distance between the tracheal bifurcation and the right atrial junction of the superior vena cava, it is possible to accurately place the distal atrial catheter using fluoroscopy alone.

This report has several limitations. First, a causal relationship between TEE used in VA shunt insertion and bilateral vocal cord paralysis cannot be proven. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis is known to result from a combination of various factors, and this was the case in our patient. We considered TEE to be strongly involved among the multifactors because the onset was immediately after VA shunt placement with TEE, and the intraoperative position was challenging for TEE insertion. Second, we did not observe the vocal cords with a laryngeal fiberscope or assess swallowing function preoperatively, so there is no guarantee that these tests could prevent postoperative bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

Lessons

We experienced a case of bilateral vocal cord paralysis on the 3rd postoperative day after a TEE-assisted VA shunt insertion for hydrocephalus secondary to severe subarachnoid hemorrhage, which resulted in an emergency tracheostomy. Although combined TEE in VA shunt insertion is useful for accurate placement of the catheter tip, bilateral vocal cord paralysis can occur as a potential complication. To prevent this complication, it may be necessary to insert the TEE under laryngeal fiberscopy guidance before positioning the patient’s head. If a patient has risk factors such as severe subarachnoid hemorrhage, management of tracheal intubation for more than 1 week, repeated tracheal intubation within 2 months, or long-term nasogastric tube placement, it is recommended that they undergo thorough preoperative vocal cord observation and swallowing function evaluation to fully assess the indication for TEE-assisted VA shunt placement.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Maruyama, Ikeda, Yoshida, Nakatomi. Acquisition of data: Ikeda, Fujii, Yoshida, Seiya, Takahashi, Kagiwata, Nagai, Onoda. Analysis and interpretation of data: Maruyama, Ikeda, Yoshida, Seiya, Takahashi, Onoda. Drafting the article: Ikeda, Fujii. Critically revising the article: Maruyama, Ikeda, Fujii, Nakatomi. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Maruyama, Ikeda, Fujii, Yoshida, Seiya, Takahashi, Onoda, Okada. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Maruyama. Study supervision: Noguchi, Nakatomi.

Supplemental Information

Previous Presentations

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 153rd Meeting of the Kanto Branch of the Japan Neurosurgical Society, Tokyo, Japan, March 23, 2024.

Correspondence

Keisuke Maruyama: Kyorin University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. kskmaru@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Isaacs AM, Krahn D, Walker AM, Hurdle H, Hamilton MG. Transesophageal echocardiography-guided ventriculoatrial shunt insertion. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2020;19(1):25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira LB, Hakim F, Semione GDS, et al. Ventriculoatrial shunt versus ventriculoperitoneal shunt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2023;94(5):903-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quintero ST, Ramirez-Velandia F, Hortua Moreno AF, Vera L, Rugeles P, Azuero Gonzalez RA. Ventriculo-atrial shunt with occlusion of the internal jugular vein: operative experience and surgical technique. Chin Neurosurg J. 2024;10(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira LB, Porto S, Jr, Andreão FF, et al. Are ventriculopleural shunts the second option for treating hydrocephalus? A meta-analysis of 543 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024;244:108396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Özbal Koç AE, Türkoğlu SB, Erol O, Erbek S. Vocal cord paralysis: what matters between idiopathic and non-idiopathic cases? Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2016;26(4):228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lechien JR, Hans S, Mau T. Management of bilateral vocal fold paralysis: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;170(3):724-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soyeur D, Born J, Lenelle J, Stevenaert A. Two-dimensional echographic localization of intracardiac cerebrospinal fluid shunt catheters. Neurosurgery. 1984;14(1):2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calliauw L, Vandenbogaerde J, Kalala O, Caemaert J, Martens F, Vandekerckhove T. Transesophageal echocardiography: a simple method for monitoring the patency of ventriculoatrial shunts. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(6):1018-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrail KM, Muzzi DA, Losasso TJ, Meyer FB. Ventriculoatrial shunt distal catheter placement using transesophageal echocardiography: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(5):747-749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuang HL, Chang CN, Hsu JC. Minimally invasive procedure for ventriculoatrial shunt—combining a percutaneous approach with real-time transesophageal echocardiogram monitoring: report of six cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(1):62-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machinis TG, Fountas KN, Hudson J, Robinson JS, Troup EC. Accurate placement of the distal end of a ventriculoatrial shunt with the aid of real-time transesophageal echocardiography. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(1):153-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohr LM, Dargan M, Hague A, et al. The incidence of dysphagia in pediatric patients after open heart procedures with transesophageal echocardiography. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(5):1450-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YY, Chia YY, Wang PC, Lin HY, Tsai CL, Hou SM. Vocal cord paralysis and laryngeal trauma in cardiac surgery. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2017;33(6):624-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chui J, MacDougall K, Ng W. Real-time 3D transesophageal echocardiography for the placement of ventriculoatrial shunt: a case series and technical note. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. Published online January 17, 2024. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofferman RA, Haisch CE, Kirchner JA, Hardin NJ. The nasogastric tube syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1990;100(9):962-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nehru VIN, Al Shammari HJ, Jaffer AM. Nasogastric tube syndrome: the unilateral variant. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12(1):44-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apostolakis LW, Funk GF, Urdaneta LF, McCulloch TM, Jeyapalan MM. The nasogastric tube syndrome: two case reports and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2001;23(1):59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sano N, Yamamoto M, Nagai K, Yamada K, Ohkohchi N. Nasogastric tube syndrome induced by an indwelling long intestinal tube. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(15):4057-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subotic U, Hannmann T, Kiss M, Brade J, Breitkopf K, Loff S. Extraction of the plasticizers diethylhexylphthalate and polyadipate from polyvinylchloride nasogastric tubes through gastric juice and feeding solution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(1):71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGinnis CM, Worthington P, Lord LM. Nasogastric versus feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(6):80-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]