Abstract

Background

Cervical ectropion is frequently associated with vaginal symptoms requiring therapeutic intervention. However, no scientific consensus has been reached regarding the use of local re-epithelialization therapy to prevent severe bleeding, wound inflammation, and infection of cervical lesions.

Objective

The aim of our study was to investigate the aspect of the cervix by colposcopy after a 3-month treatment with an intravaginal medical device in the context of postoperative care of the symptomatic ectropion. The study analyzed additional clinical parameters, such as the evolution of primary and secondary inflammation and the degree of cervical epithelialization as secondary objectives.

Methods

Our pilot study included 27 participants with symptomatic cervical ectopy, with or without an associated human papillomavirus infection. The treatment protocol consisted of the monthly delivery of the medical device intravaginally, during day 1 to day 15, with a total study duration of 3 months.

Results

The medical device had a positive impact on cervical epithelialization, in terms of aspect of the cervix returning to normal for 100% of the participants. Between study visits, it was observed that primary inflammation was reduced by 85.19%, whereas vaginal ulceration, colpitis, and leukorrhea were improved by 70.37%, 81.48%, and by 66.67%, respectively.

Conclusions

The degree of cervical epithelialization reflects how well the cervix has healed after an injury or infection. The device showed clinical performance in complete re-epithelialization after surgical procedures. Moreover, our study findings suggest that supportive treatment with this intravaginal medical device can be recommended for cervical wound healing in patients with human papillomavirus infection. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04735718.

Key words: cervical ectopy, cervical epithelialization, human papillomavirus, medical device, postoperative care, vaginal bleeding

Introduction

High estrogen exposure, particularly during puberty or pregnancy, can significantly influence cervical cells in the context of cervical ectropion (CE) and other related conditions. During the different phases of female reproduction, the cervical area undergoes specific transitions.1 Ectropion is seen frequent as a normal physiological state, after the menarche, when the columnar epithelium grows and becomes exposed in the ectocervix. It is associated with a red appearance because of exposed blood vessels, and it can be asymptomatic or symptomatic.

Asymptomatic ectropion is quite benign, and in developed countries, no treatment is prescribed. However, symptomatic CE is linked to various clinical conditions, such as urinary tract infections, candidiasis, vaginitis, cervicitis, or cervical dyskaryosis.2 Although the cervix acts like a barrier to prevent bacteria and viruses from entering the uterus, the squamous–cylindrical junction is the main site through which human papillomavirus (HPV) enters the epithelium and can disseminate into its deep cells. As such, CE is also correlated with HPV infection, as well as other pathologic conditions such as benign neoplasms and premalignant and malignant anomalies.3,4 The treatment of CE has an important significance for preventing the occurrence of precancerous lesions and cervical cancer.5 The plethora of symptoms linked to CE include vaginal discharge, vulvar itching, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, postcoital bleeding, nocturia, and frequency of micturition.6,7

During pregnancy, estrogen levels rise significantly, which can lead to a more pronounced CE associated with increased vascularization and mucus production, leading to the cervix becoming sensitive and more prone to bleeding.

Prevalence studies show that CE can vary between 14% and 54.9%, and it increases with parity.8, 9, 10 A multitude of cervical lesions appear as a result of exposure to estrogen or more controversial, infection with HPV.11, 12, 13, 14 Oral contraceptives, particularly those containing estrogen, have a well-documented connection with CE.15

The management of symptoms in CE such as increased vaginal discharge, postcoital bleeding, or spotting is focused on improving patient quality of life. Regional differences in the treatment arsenal exist, whereas several studies reveal different therapeutic approaches, such as diathermy, electrocoagulation, microwave coagulation, or cryotherapy.16, 17, 18 Postsurgical scars on the cervix, such as those resulting from procedures like loop electrosurgical excision procedure, conization, or cervical laceration repair, may also be managed conservatively if asymptomatic. To our knowledge, few studies, if any, are focusing on the postoperative management of cervical wounds in the Western population. Also, in most studies performed to date, the improvement of the appearance of the cervix was taken as evidence of the success of the treatment rather than the symptoms’ management.

The primary aim of our study was to investigate the aspect of the cervix by colposcopy after a 3-month treatment with an intravaginal medical device in the context of postoperative care of the symptomatic ectropion. The study analyzed additional clinical parameters, such as the evolution of primary and secondary inflammation, the cervical mucosa epithelialization, and the symptoms’ relief. Tolerability was assessed through the rate of treatment-related adverse events in patients participating in the clinical investigation.

Materials and methods

Study design

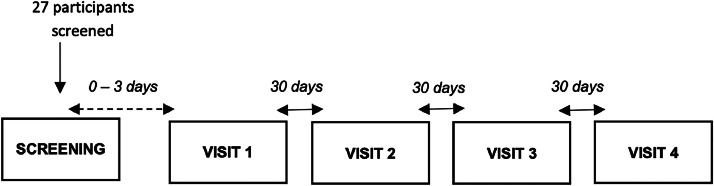

This study was designed as an open-label, non-comparative, non-randomized, pilot, multicentric, and national clinical investigation. The study took place between July 9, 2021 (first participant in) and January 6, 2023 (last participant out), in 3 investigational sites located in Romania, as follows: Institutul National pentru Sanatatea Mamei si Copilului “Alessandrescu-Rusescu”—Department of Obstetrics–Gynecology III Bucharest, Emergency County Clinical Hospital “Pius Brinzeu” Timisoara—Department of Obstetrics-Gynecology II, and Misca Medical Center Timisoara, Department of Obstetrics–Gynecology. A study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. The study registration number is NCT04735718 (www. clinicaltrials.gov).

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart.

The device's performance in nonspecific vaginitis was confirmed in a recent study,19 where for 72.34% patients it was observed that the medical device had a beneficial effect on reducing the score of vaginal symptoms, with a high safety profile. Within 3 months of treatment with the medical device, the changes in inflammatory and parabasal epithelial cells were relevant, with 32 study participants recording an improvement.

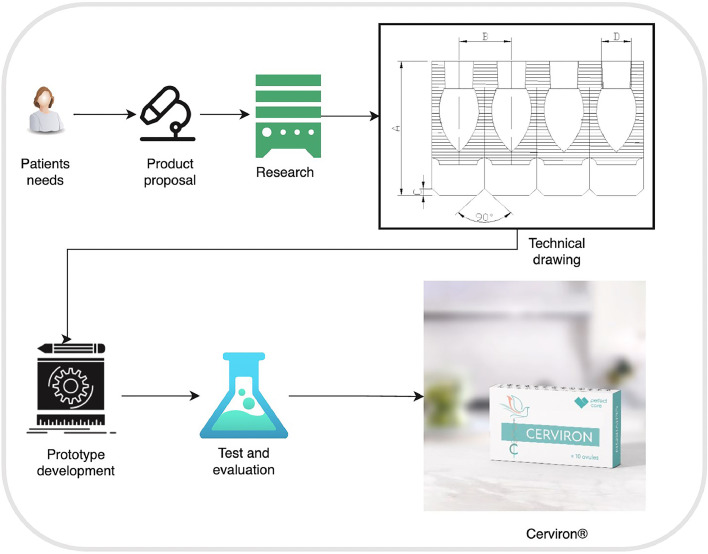

The medical device

The intravaginal device was authorized following the provisions of the Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC and is marketed by Perfect Care Distribution within the territories of Europe and Middle East. The device is formulated as vaginal ovules with a complex composition as follows: bismuth subgallate 100 mg, hexylresorcinol 2 mg, vegetable collagen 15 mg, Calendula officinalis 10 mg, Hydrastis canadensis 10 mg, Thymus vulgaris 10 mg, and Curcuma longa 10 mg. The instructions for use specify its field of use as an adjuvant in the treatment of acute and chronic vulvovaginitis of mechanical origin caused by changes in vaginal pH and changes of the vaginal flora and cervical lesions of mechanical origin. The recommended use of the device is 1 ovule per day inserted on the first day after the menstruation, applied during 15 consecutive days. Its adjuvant role in the treatment of nonspecific vaginitis was outlined in a recent clinical investigation (NCT04735705) and a real-world study (NCT05668806) confirmed its intended use as a treatment for cervical lesions of different etiologies.17,20 It favors the healing and re-epithelialization processes and reduces the proliferation of endogenous pathogens. The medical device is indicated for the treatment of vaginal symptoms such as leukorrhea, vaginal pruritus, burns in the vaginal area, rash, vaginal discharge with malodour, dysuria, dyspareunia, and vaginal bleeding. It is typically used for procedure-related injuries associated with vaginal or cervical trauma (eg, after vaginal birth, surgery, and radiation), age-related dryness, or various pathologies (eg, vulvovaginitis).

The study architecture is represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Study architecture.

Participant population

The target population for this clinical investigation included women aged 18 to 65 years presenting a normal cervical cytology report, for example, negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, atypical glandular cells or slightly modified to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance in the last 6 months, who underwent surgical removal of benign, cervical lesions and with characteristic signs and symptoms. Vulnerable subjects were not enrolled in this clinical investigation. Patients with a previous history of any malignancy, including patients with vulvar, vaginal, or cervical cancer or with undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding, were excluded.

Ethical and regulatory aspects of the study

Written consent for study participation was collected from all patients before any research-specific procedure. General Data Protection Regulation was followed, and patients have been informed about their right to request that their data be removed from the study database. The National Ethics Committee (CNBMDM) evaluated all study-related documentation and released its favorable opinion before the site initiation. Initial Approval 2DM was received on April 1, 2021 (protocol number CYRON/02/2021; NCT04735718). The clinical data were gathered and assessed by the Helsinki Declaration's ethical criteria.

Data collection

The clinical investigation included patients under treatment with Cerviron® (Perfect Care Manufacturing SRL, 82 Complexului Street, Buildings C1, C2 and C3, Mihailesti, Giurgiu County, Romania) vaginal ovules for approximately 3 months (Fig. 1). At study entry and at 1, 2, and 3 months after the initial screening visit, participants were interviewed and received visual cervical examinations by colposcopy. At each visit, participants received a standardized pelvic examination with placement of a speculum and visualization of the cervix. Prospective data were collected from each participant, such as initial diagnosis, colposcopy examination results, re‑epithelialization degree, vaginal symptoms, any worsening symptoms, and adverse events.

The colposcope examination included distinct data on primary and secondary inflammation, based on the underlying causes. Primary inflammation was considered the initial inflammatory response that directly resulted from the exposure of glandular cells on the ectocervix, because of CE, whereas secondary inflammation was considered when other factors (such as fungi, bacterial colonization, or HPV) exacerbated the inflammatory response, leading to more pronounced symptoms.

Each participant performed visits (screening visit for eligibility evaluation, administration of the medical device, site visit after 30 days, site visit after 60 days, site visit after 90 days). The screening medical history included data related to early onset on sexual activity (before the age of 18 years), multiple or single sexual partner, any immune system deficiencies, the usage of oral contraceptives for a period longer than 5 years, past vaginal symptoms (such as dyspareunia, bleeding, dysuria, leucorrhea, malodour), any allergies, smoking and alcohol consumption history, any vaginal infections present in the last 6 months, date of the last menstrual cycle, usage of intrauterine devices, and any surgical interventions (such as hysterectomy or other). A Babes Papanicolaou smear was collected from all participants during the screening procedures.

A total number of 27 participants were screened during the enrolment period of 15 months, between July 12, 2021, and October 18, 2022. Of 27 patients enrolled in the clinical study, 1 patient (0207) did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and as such, was not included in the clinical trial and another patient (0307) was lost to follow-up. The safety population included the 25 participants receiving the treatment as per protocol. All patients had a 100% compliance.

The effects were measured as differences in clinical performance determined by colposcopy examination and the presence of vaginal symptoms assessed by the study participant between the baseline visit and 3 successive study visits (scheduled at 30-day intervals). The evaluation of the medical device's performance comprised the following clinical outcomes: aspect of the cervix, change in vaginal discharge aspect, change in vaginal inflammation, and participant satisfaction at the end of therapy.

Colposcopy examination with LEO-2100I was performed at baseline and following the 3 consecutive months the medical device was applied. A colposcope examination of the cervix was performed using Lugol's iodine to assess the aspect of the cervix. Normal aspect was defined as follows: no tissue and cellular changes, normal appearance of the cervix, and normal appearance of the vaginal smear. Abnormal aspect was defined by tissue and cellular changes: wounds and inflammation of the vaginal and cervical mucosa or cellular abnormalities that indicate the appearance of cervical neoplasm or precancerous lesions.

Aspect of the cervix was rated during all visits by clinical examination defined as follows: complete epithelization (the cervical surface has fully regenerated with squamous epithelial cells covering the entire area. The cervix appears smooth, with no visible lesions or areas of raw tissue); partial epithelization with some areas of the cervix being regenerated with epithelial tissue but other areas are showing focal hyperplasia areas; absent epithelization (the area is ulcerated or highly inflamed).

The change in vaginal discharge aspect was rated per investigator during each visit on an intensity scale from 1 to 5 as follows: 0 = no symptoms are present, 1 = mild symptoms are present, 2/3 = moderate symptoms, 4 = severe symptoms, and 5 = very severe and unbearable symptoms.

Based on the underlying causes, the investigators rated inflammation as primary and secondary. The presence of erosions, ulcers, colpitis, vaginal discharge, and vaginal irritation were rated as present or absent during clinical examination.

The degree of satisfaction was measured by a 5‑point Likert scale during the last study visit (after 90 days) as follows: very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, unsatisfied, and very unsatisfied.

Adverse events and concomitant medications were collected at each visit. Each participant was followed up for 3 months or approximately 90 days. The data were exported and analyzed using Analyse-It for Mi- Microsoft Excel, version 5.90 (Analyse-It Software Ltd, Leeds, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and generation of tables, figures, and patient data listings were performed using R statistical software version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The overall type I error was preserved at 5%; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and 95% CIs were calculated.

To evaluate changes of proportions over time before and after the treatment, for categorical variables, a 2-proportions z-test or Fisher's exact test was performed. The change in vaginal score between visits was evaluated using the Kruskall-Wallis test and for detecting the change in vaginal score for the first 30 days of treatment Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed.

The following primary results were collected in this study: colposcopy examination, the presence of primary and secondary inflammation, the presence of erosions, ulcers, colpitis, vaginal discharge, and vaginal irritation.

As secondary outcomes, the following clinical symptoms and signs were verified to demonstrate the efficacy and performance of Cerviron: re-epithelialization degree (by visual examination), primary inflammation, secondary inflammation, erosion, ulceration, colpitis, vaginal discharge, and vaginal irritations. A typical satisfaction survey (5-point Likert scale) was used as a measurement of participant satisfaction and comfort.

Results

Out of the 26 participants initially enrolled, 25 patients completed the study. During the colposcopy examination, at the screening visit, participants presented cervical erosions, ulcerations, and colpitis macularis (“strawberry cervix”). Three patients have had Nabothian cysts and 4 participants had an associated HPV infection. Primary inflammation was present for all study participants. Table 1 shows the demographic data of all study participants.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Baseline characteristics | Experimental |

|

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age (years): mean ± SD | 26 | 36.96 ± 10.28 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 26 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 26 | 100 |

| Height (cm): mean ± SD | 26 | 166.00 ± 5.51 |

| Weight (kg): mean ± SD | 26 | 65.31 ± 9.44 |

| Patient in menopause | ||

| Yes | 1 | 3.80 |

| No | 25 | 96.20 |

| Tobacco consumption | ||

| Yes | 6 | 23.10 |

| No | 20 | 76.90 |

| Alcohol | ||

| Yes | 2 | 7.69 |

| No | 23 | 88.46 |

| Unknown | 1 | 3.85 |

| Regular menstrual cycle | ||

| Yes | 25 | 96.20 |

| No | 1 | 3.80 |

Success was defined by resolution (normal colposcopy result) and substantial improvement in clinical signs after 90 days of treatment with Cerviron. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The colposcopy examination results.

| Colposcopy examination | Visits |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 90 days | |

| Normal | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) |

| Abnormal | 25 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total number of patients | 25 | 25 |

After 3 months of treatment with Cerviron, for 100% of the participants (N = 25) the colposcopy results were rated as normal (P < 0.001; 95% CI, 96–100).

At the same time, the following clinical symptoms were verified: primary and secondary inflammation, signs of cervical erosion, ulceration, colpitis, abnormal discharge, and vaginal irritation. Thus, at the first visit, 96% of the study participants (N = 24) presented primary inflammation, 84% (N = 21) erosion, 68% (N = 17) vaginal ulcerations, 92% (N = 23) colpitis, and 80% (N = 20) vaginal secretions. Table 3 shows all the clinical symptoms that were investigated to determine the effectiveness of the medical device.

Table 3.

Analysis related to vaginal symptoms—comparison between visits.

| Vaginal symptoms | Baseline |

90 d |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence | Absence | Presence | Absence | ||

| Primary inflammation | 24 (96%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P < 0.001 |

| Secondary inflammation | 5 (20%) | 20 (80%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P = 0.050* |

| Erosion | 21 (84%) | 4 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P < 0.001 |

| Ulceration | 17 (68%) | 8 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P < 0.001 |

| Colpitis | 23 (92%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P < 0.001 |

| Vaginal discharge | 20 (80%) | 5 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P < 0.001 |

| Vaginal irritations | 5 (20%) | 20 (80%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (100%) | P = 0.050* |

P value was obtained with the 2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction.

P value was obtained with Fisher's exact test.

It can be observed that after 90 days of treatment primary inflammation, vaginal erosion, ulceration, colpitis, and vaginal secretion were reduced by 100%.

The effect of the medical device on different vaginal symptoms was verified. Thus, at the first visit, 96% of the study participants (N = 24) presented primary inflammation, 84% (N = 21) erosion, 68% (N = 17) vaginal ulcerations, 92% (N = 23) colpitis, and 80% (N = 20) vaginal secretions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Degree of re-epithelialization between each visit.

| Degree of re-epithelialization | Baseline | 30 d | 60 d | 90 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | 18 (72%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Partial | 7 (28%) | 24 (96%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

| Complete | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 22 (88%) | 25 (100%) |

Degree of re-epithelialization

The degree of epithelialization was assessed every 30 days (at each visit) using a score as follows: 1—absent, 2—partial, and 3—complete. The change in the degree of epithelialization during visits 1 to 4 is shown in Table 4.

After 30 days of treatment with the medical device, a significant improvement in the degree of epithelialization was observed (P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). After 60 days, 88% of the study participants patients had a complete local re-epithelialization (P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). At the end of the treatment schedule, after 90 days, all patients presented a complete degree of epithelialization, which shows a very good performance in terms of local re-epithelialization (P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test).

Change in vaginal symptoms

A range of symptoms were assessed during the study, as secondary objectives, presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Means and SDs of each symptom between visits.

| Measure | Baseline | 30 d | 60 d | 90 d | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | 1.44 ± 1.16 | 0.56 ± 0.71 | 0.04 ± 0.20 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | P < 0.001 |

| Malodour | 1.52 ± 1.33 | 0.56 ± 0.71 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | P < 0.001 |

| Dysuria | 1.40 ± 1.35 | 0.80 ± 1.19 | 0.16 ± 0.62 | 0.20 ± 1.00 | P < 0.001 |

| Dyspareunia | 1.68 ± 1.57 | 0.68 ± 0.85 | 0.00 ± 0.64 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | P < 0.001 |

| Pain | 1.60 ± 1.32 | 0.56 ± 0.65 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | P < 0.001 |

| Leucorrhea | 2.08 ± 1.38 | 0.56 ± 0.65 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | P < 0.001 |

Note. Mean and SD are presented by the form μ and the SD.

P value is obtained using the Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric test.

During this analysis, it was observed that treatment with Cerviron reduces bleeding score after 90 days in all cases from a mean score of 1.44 ± 1.16 points at baseline to 0.00 ± 0.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001), malodour score after 90 days in all cases from a mean score of 1.52 ± 1.33 points at baseline to 0.00 ± 0.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001), dysuria symptoms from a mean score of 1.40 ± 1.35 points at baseline to 0.20 ± 1.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001), dyspareunia symptoms from a mean score of 1.68 ± 1.57 points at baseline to 0.00 ± 0.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001), pain score after 90 days in all cases from a mean score of 1.60 ± 1.32 points at baseline to 0.00 ± 0.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001), and leucorrhea symptoms after 90 days in all cases from a mean score of 2.08 ± 1.38 points at baseline to 0.00 ± 0.00 points at the final visit (P < 0.001).

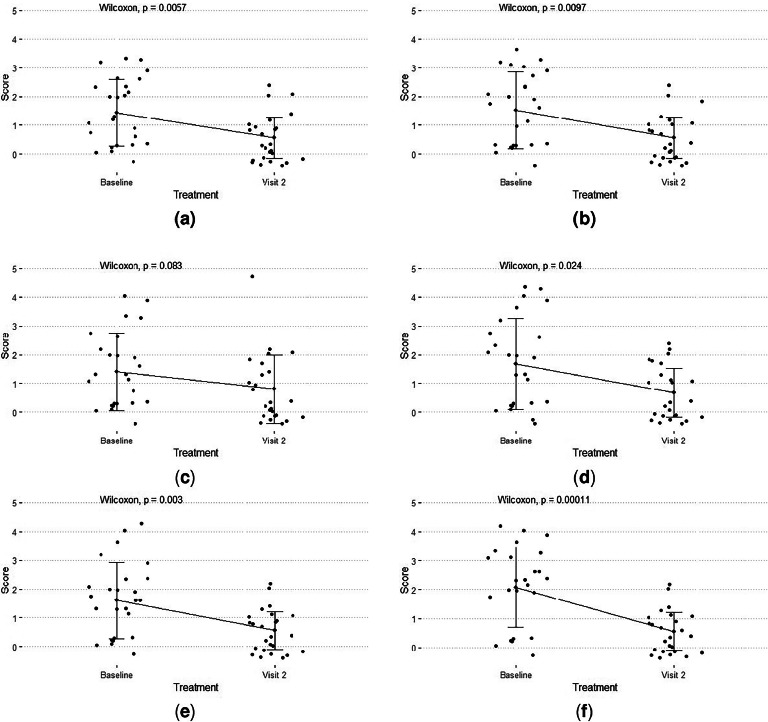

Treatment with Cerviron shows significant efficacy (Fig. 3A) in reducing bleeding score after 30 days with 61.11% from 1.44 ± 1.16 at baseline to 0.56 ± 0.71 (P < 0.05). Also, it shows significant efficacy to reduce malodour score with 63.16% (Fig. 3B) from 1.52 ± 1.33 points to 0.56 ± 0.71 points (P < 0.05), dysuria with 42.86% (Fig. 3C) from 1.40 ± 1.35 points to 0.80 ± 1.19 points (P = 0.083), dyspareunia score with 59.52% (Fig. 3D) from 1.68 ± 1.57 points to 0.68 ± 0.85 points (P < 0.05), pain score with 65.00% (Fig. 3E) from 1.60 ± 1.32 points to 0.56 ± 0.65 points (P < 0.05), and leucorrhea symptoms with 73.08% (Fig. 3F) from 2.08 ± 1.38 points to 0.56 ± 0.65 points (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Improvement of scores after 30 days of treatment with Cerviron (A) bleeding; (B) malodour; (C) dysuria; (D) in dyspareunia; (E) in pain; (F) in leucorrhea.

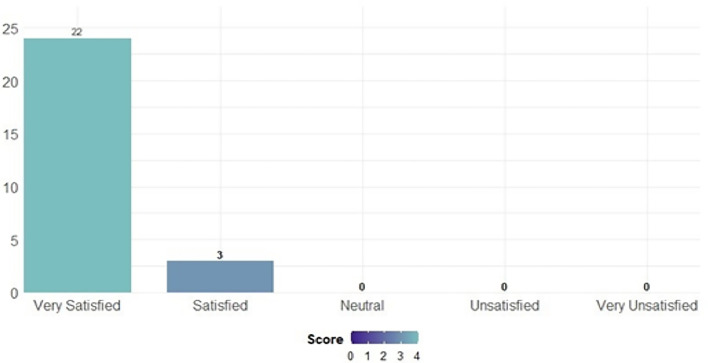

The degree of satisfaction when using the medical device was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. The evaluation of participant satisfaction was summarized in Fig. 4. The majority of participants (88%) in the study declared themselves very satisfied (N = 22), whereas 12% (N = 3) were satisfied with the product.

Fig. 4.

Participant satisfaction score—Likert scale.

Safety profile

At the final study visit, none of the study participants presented treatment-related adverse events, which indicate a high safety profile.

Discussion

The active ingredient bismuth subgallate could be a factor involved in protecting the wound from trauma and bacteria because of its local astringent action, forming a protective barrier in the vaginal mucosa. Histometric measurements in studies of bismuth subgallate-treated wounds showed a larger area of ulceration of bismuth subgallate-treated wounds on the first day.19,21

Reducing primary inflammation associated with cervical ectopy

The pathogenesis of CE involves increased levels of circulating estrogens.22 Straub studied the complex processes of inflammation related to estrogen signaling toward immune cell trafficking.23 The T-helper 17 cells producing interleukins are the main T-cells responsible for chronic inflammation. A correlation was found between CE and the development of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis with overlapping symptoms.24 Additionally, cervical erosions lead to the occurrence of acute of chronic cervicitis in some cases.

The degree of cervical epithelization reflects how well the cervix has healed after an injury, infection, or medical procedure. It ranges from complete epithelization, where the cervix has fully regenerated its epithelial tissue, to delayed or incomplete epithelization, where healing is impaired. Factors influencing epithelization include the severity of the initial lesion, type of treatment, patient's general health, and hormonal status. Regular follow-up and monitoring are essential to ensure proper healing and address any complications.

An important finding of this study is that the medical device seems to exert a beneficial effect in reducing primary inflammation associated with CE. Clinical symptoms such as vaginal erosion, ulceration, and abnormal leukorrhea production have markedly improved under treatment. These findings support and extend its role in improving sexual function in these patients, by reducing dyspareunia and dysuria, associated with any cervical lesions.25 In a similar study, topical treatment with vaginal ovules containing aqueous extract of Triticum vulgare for 2 months resulted in a significant decrease of symptoms related to CE and a significant reduction of the size of the ectropion area.26

The risks of the HPV infection and cellular reprogramming

When the cervix is exposed to low vaginal pH or HPV infection, there is a risk of development of metaplasia. An association between ectopy and HPV was found in a cross-sectional study, conducted by Rocha-Zavaleta et al14 According to the study results, the researchers found a higher general HPV rate and a higher rate of HPV-16 in women with CE.14 As such, evolution of CE can inform preventive strategies in cervical cancer.27 The study by Sarkar and Steele suggested that there was an association between cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and ectopy.28 The transformation zone is a precursor to low-grade dysplasia, which can culminate in high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma.29 Moreover, histopathological diagnosis shows that postcoital bleeding is often associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical polyps, and inflammatory cervical smears bearing a high risk for invasive cervical cancer.30 During our present investigation, 4 study participants had an associated HPV infection. The degree of epithelialization was very good, and also the aspect of the cervix improved in 90 days, after the treatment with Cerviron vaginal ovules. As such, supportive treatment with Cerviron can be recommended for cervical wound healing and/or symptom relief in patients with HPV infection.

Routine treatment in CE is recommended, especially when considering taking preventive action against cervical cancer. Ectopy is modified over time by squamous metaplasia, epithelialization, low pH, trauma, and possibly by cervical infection. There is a relationship between squamous metaplasia and induction of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Cells undergoing metaplasia are more susceptible to carcinogens. Precancerous lesions often develop at the squamous–columnar junction, that is, the area of transition between glandular and stratified epithelium, which is the location where metaplasia is most intense. Also, cervical cysts left untreated can induce considerable enlargement of the cervix, which can lead to symptomatology.

Prevention of infections with sexually transmitted microorganisms such as Chlamydia trachomatis

Recognition of CE should alert the clinician to the possibility of a genital Chlamydia infection. Opportunistic screening for Chlamydia in young people should be offered to reduce the prevalence of infection and its sequelae. Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted disease associated with CE.6,31 In women, chlamydial infection usually presents as cervicitis, which can lead to up to 30% to 50% of pelvic inflammatory disease episodes.32 Of 26 participating patients, there were 0 cases of infection involving sexually transmitted microorganisms such as C. trachomatis. As such, Cerviron supportive therapy may be prescribed in sexually active patients for at least 1 to 3 months, 10 to 15 consecutive days, to prevent these infections. Through its ingredient, bismuth subgallate, Cerviron ovules exert a local protective action on mucous membranes and raw surfaces.21,33 Moreover, it contains collagen with nutritive, hydrating, healing, and trophic effects. Collagen is a key protein favoring the forming the scars during the healing of conjunctive tissues because of its chemotactic role. Many collagen bandages were developed to improve the repair of the wound, especially of noninfected, chronic, idle cutaneous ulcerations. The Marigold extract (Calendula officinalis) exerts the role of preventing fatty base degradation.

The study results show that a 45-day treatment (3 treatment sessions of 15 days each) with Cerviron vaginal ovules was beneficial in providing a complete degree of cervical epithelialization and reduced the multitude of vaginal symptoms, including bleeding, inflammation, malodour, dysuria, dyspareunia, pain, and leucorrhea. This result was consistent with previous clinical studies reporting similar benefits for the same medical device, NCT04735705, and NCT05668806.19,20

Cerviron usefulness in patients with intrauterine contraceptive devices

The usage of intrauterine contraceptive devices could be linked to inflammation and trauma of the cervix. Because vaginal discharge is a common symptom of intrauterine contraceptive devices users, changing the method of contraception is a common practice for women who are unable to accept the increase in physiological discharge associated with CE. Cerviron should be recommended in patients using intrauterine contraceptive devices to reduce vaginal discharge, reduce primary inflammation, and improve the epithelialization of the cervical area.34

Patterns of recurrence in cervical cancer

Considering our study cohort relevant for the topic of cervical cancer recurrence, we emphasize a cautious consideration of surgical approach is needed in cervical cancer, balancing the immediate benefits of minimally invasive surgery against its long-term oncological implications. The findings published by Corrado et al indicate a notable difference in recurrence rates between the minimally invasive surgery showing higher rate of recurrence, compared with the abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with The 2018 revised International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB1 and IB2 cervical cancer.35 Also, another critical finding is that, despite the advantages of total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in terms of recovery and perioperative outcomes, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy groups. However, this study reported that the total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy group had a higher recurrence rate.36

Study strengths and limitations

Our study had several strengths. First, the development of local therapies for patients pending ablative treatment for CE is extremely useful. Second, we believe our study paves the way for continuous research in preventive strategies against the development of cervical cancer. The cohort of this study and the various outcomes can be a hallmark that the patient's tailored treatment could be improved. Third, the results of this study can guide treatment decisions during the management of inflammation related to CE and cervical wounds.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the study cohort was small, which affects the generalizability of the study results. The small sample size can be explained by the nature of the study design (pilot investigation) and the treatment response in an early interim analysis. Within the interim analysis performed in a subset of 5 patients, it was observed that Cerviron improves colposcopy examination in approximately 60% of treated patients. The eligibility criteria constraints were given as a reason for the small number of recruited patients. An interim analysis was conducted to explain keeping the effect size even on a smaller sample size. Expecting the effect size of 0.6, we re-estimated the sample size with type I error at 5% and type II at 20% (power 80%) in at least 20 patients. Second, the study timeframe of 3 months should be extended to verify the long-term performance of the device. Therefore, a study with larger sample is necessary to elucidate the real impact of the treatment in a more diverse population setting and during a longer exposure over time.

Conclusions

Cerviron ovules proved to be a well-tolerated adjuvant therapy promoting cervical epithelialization after ablative therapies. The medical device favors the re-epithelialization of the damaged tissue and reduces vaginal inflammation. Its topical application was observed to be effective in reducing vaginal symptoms such as vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, malodour, dysuria, and dyspareunia.

These findings suggest its use in the management of nonmalignant cervical disease, including cervicitis, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical polyps, Nabothian cysts, cervical hypertrophy, or cervical genital warts. Moreover, our study findings suggest that supportive treatment with Cerviron can be recommended for cervical wound healing in patients with HPV infection. As the medical device under consideration seems to exert relevant changes in the symptoms associated with inflammation that could also support faster tissue repair, a future research goal is the evaluation of its performance as a maintenance treatment in desquamative inflammatory vaginitis or other inflammatory-mediated skin diseases of the genitalia. The clinical investigation and its details were submitted to www.clinicaltrials.gov, under reference ID NCT04735718.

Declaration of competing interest

R.P. is currently employed at MDX Research. A.R.P. provided statistical input while working for MDX Research. MDX Research was involved in the study design, site selection, collection, statistical analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. The authors have indicated that they have no other conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

Acknowledgments

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

Perfect Care Distribution provided financial support for the clinical investigation. However, Perfect Care Distribution had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author contributions

Dr Petre, Pharm Petrita, and Dr Toader were involved in the study design methodology and original draft preparation. Dr Toader, Dr Alexa, and Dr Petre performed the laboratory measurements and data entry. Pharm Petrita performed clinical data monitoring and data analysis. Pharm Pinta performed the statistical analysis. Pharm Petrita, Dr Petre, and Dr. Bita were involved in interpretation of results, manuscript review and editing. All authors participated in the interpretation of the study results. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants who voluntarily enrolled in the study. The authors also thank Florentina Liliana Calancea for the technical support provided during data management collection and to Perfect Care Distribution for providing a research grant.

References

- 1.De Tomasi JB, Opata MM, Mowa CN. Immunity in the cervix: interphase between immune and cervical epithelial cells. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2019/7693183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleppa E, Holmen SD, Lillebø K, et al. Cervical ectopy: associations with sexually transmitted infections and HIV. A cross-sectional study of high school students in rural South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:124–129. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu Z, Chen H, Zheng X-M, Chen M-L. Expression and clinical significance of high risk human papillomavirus and invasive gene in cervical carcinoma. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017;10:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham SV. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin Sci. (Lond) 2017;131:2201–2221. doi: 10.1042/CS20160786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merera D, Jima GH. Precancerous cervical lesions and associated factors among women attending cervical screening at Adama Hospital Medical College, Central Ethiopia. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:2181–2189. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S288398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matiluko AF. Cervical ectropion. Part 2: assessment of symptomatic women. Trends Urology Gynaecol Sexual Health. 2009;14:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agah J, Sharifzadeh M, Hosseinzadeh A. Cryotherapy as a method for relieving symptoms of cervical ectopy: a randomized clinical trial. Oman Med J. 2019;34:322–326. doi: 10.5001/omj.2019.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal P, Ben Amor A. StatPearls Publishing; StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL: 2020. Cervical Ectropion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Junior JE, Giraldo PC, Gonçalves AKS, et al. Uterine cervical ectopy during reproductive age: cytological and microbiological findings. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:401–404. doi: 10.1002/dc.23053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotarcea S, Stefanescu C, Adam G, et al. The importance of ultrasound monitoring of the normal and lesional cervical ectropion treatment. Curr Health Sci J. 2016;42:188–196. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.42.02.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewavisenti RV, Arena J, Ahlenstiel CL, Sasson SC. Human papillomavirus in the setting of immunodeficiency: pathogenesis and the emergence of next-generation therapies to reduce the high associated cancer risk. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang LY, Lieberman JA, Ma Y, et al. Cervical ectopy and the acquisition of human papillomavirus in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1164–1170. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182571f47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinelli M, Musumeci R, Sechi I, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among Italian women referred for a colposcopy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:5000. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16245000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha-Zavaleta L, Yescas G, Cruz RM, Cruz-Talonia F. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical ectopy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;85:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anastasiou E, McCarthy KJ, Gollub EL, et al. The relationship between hormonal contraception and cervical dysplasia/cancer controlling for human papillomavirus infection: a systematic review. Contraception. 2022;107:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pegu B, Srinivas BH, Saranya TS, et al. Cervical polyp: evaluating the need of routine surgical intervention and its correlation with cervical smear cytology and endometrial pathology: a retrospective study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020;63:735–742. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shallal F. Clinical observation of electrocauterization alone and post-electrocauterization MEBO application therapy in the treatment of cervical erosion. Mustansiriya Med J. 2015;14:7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakhipova GZ, Abenova NA, Zhumabaeva TN, et al. Clinical experience in management of patients with cervical erosion and ectopia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020;8(B):226–230. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toader DO, Olaru RA, Iliescu D-G, et al. Clinical performance and safety of vaginal ovules in the local treatment of nonspecific vaginitis: a national, multicentric clinical investigation. Clin Ther. 2023;45:873–880. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petre I, Sirbu DT, Petrita R, et al. Real‑world study of Cerviron® vaginal ovules in the treatment of cervical lesions of various etiologies. Biomed Rep. 2023;19:1–9. doi: 10.3892/br.2023.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakami PA, Velez-Montoya R, Castillejos-Chevez A, et al. Safety and efficacy of bismuth subgallate as an hemostatic agent in an animal experimental model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1510. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado LC, Jr, Dalmaso ASW, Carvalho HBD. Evidence for benefits from treating cervical ectopy: literature review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2008;126:132–139. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802008000200014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:521–574. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell L, King M, Brillhart H, Goldstein A. Cervical ectropion may be a cause of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. J Sex Med. 2017;14:e366. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma J, Kan Y, Zhang A, et al. Female sexual dysfunction in women with non-malignant cervical diseases: a study from an urban Chinese sample. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manna P, Gallo A, Bitonti G, et al. Efficacy of a Triticum vulgare extract as a treatment of cervical ectropion: a prospective observational cohort study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2024;28:254–257. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw E, Ramanakumar AV, El-Zein M, et al. Reproductive and genital health and risk of cervical human papillomavirus infection: results from the Ludwig-McGill cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:116. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1446-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar P.K., Steele P.R.M. Routine colposcopy prior to treatment of cervical ectopy: Is it worthwhile? J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;16(2):96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giroux V, Rustgi AK. Metaplasia: tissue injury adaptation and a precursor to the dysplasia–cancer sequence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen O, Schejter E, Agizim R, et al. Postcoital bleeding is a predictor for cervical dysplasia. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soares LC, Braz FLTA, Araújo AR, Oliveira MAP. Association of sexually transmitted diseases with cervical ectopy: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:452–457. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee A, Kim TH, Lee HH, et al. Therapeutic approaches to atrophic vaginitis in postmenopausal women: a systematic review with a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Menopausal Med. 2018;24:1–10. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2018.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright KO, Mohammed AS, Salisu-Olatunji O, Kuyinu YA. Cervical ectropion and intra-uterine contraceptive device (IUCD): a five-year retrospective study of family planning clients of a tertiary health institution in Lagos Nigeria. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:946. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrado G, Anchora LP, Bruni S, et al. Patterns of recurrence in FIGO stage IB1-IB2 cervical cancer: comparison between minimally invasive and abdominal radical hysterectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2023;49 doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.107047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pecorino B, D'Agate MG, Scibilia G, et al. Evaluation of surgical outcomes of abdominal radical hysterectomy and total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a retrospective analysis of data collected before the LACC trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:13176. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.