Abstract

Chicken bile is a by-product of chicken processing, rich in chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), an active pharmaceutical raw material. In this study, a green measure for the extraction and purification of CDCA from chicken biles by enzymatic hydrolysis and macroporous resins refining was established. For the assisted extraction of CDCA, the active bile salt hydrolase (BSH) from Bifidobacterium was heterologously expressed and applied, its activities on GCDCA and TCDCA were 4.96 ± 0.32 U/mg and 3.07 ± 0.031 U/mg and optimal catalytic conditions for the extraction of CDCA were determined as 0.04 g/g of the enzyme dosage, pH 5.0 and 38 °C. Through validation of the conditions, the yield of CDCA was up to 5.32 %, which was equivalent to that by saponification method. In order to further refine CDCA from the extract obtained by enzyme-assisted extraction, a more preferable resin, AB-8 was selected for the purification of CDCA, which had a good adsorption capacity of 61.06 ± 0.57 mg/g for CDCA. Besides, the obtained CDCA extract was purified through AB-8 resin, the purity of CDCA was improved from 51.7 % to 91.4 % and the recovery yield of CDCA was 87.8 %. The advantages of energy conservation, time saving, economy and environmental friendliness make the measure using enzyme-assisted extraction and macroporous resins refining a promising candidate for isolation of CDCA from chicken bile.

Keywords: Bile salt hydrolase, Chenodeoxycholic acid, Macroporous resin, Adsorption, Purification

Introduction

Chicken bile is digestive juice secreted by chicken liver cells, which has effects on anti-inflammatory, cough relieving, expectorant, detoxifying and eye brightening according to Compendium of Materia Medica, a world renowned treatise on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Studies on the chemical composition and pharmacological activities of chicken bile indicated that bile acids are the main active components in bile and the key for chicken bile to exert pharmacological effects, led chicken bile processing mainly revolved around the extraction of bile acids, especially in extraction of chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA, MW: 392.57), which is a leading constituent and counted for about 80% in total bile acid of chicken bile (Hu et al., 2018). To our knowledge, CDCA is a commonly used drug for treatment of hepatobiliary diseases, including cholesterol stones (Danzinger et al., 1972), cholestatic diseases (Guo and Wei, 2008), primary biliary cirrhosis (Corpechot et al., 2000). CDCA is also used as a synthetic raw material for other effective drugs, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for hepatobiliary diseases (Makino et al., 1975) and obeticholic acid (OCA) for primary billiary cirrhosis (PBC) (Floreani and Mangini, 2018). Additionally, CDCA has been applied in animal feeds for pigs, chickens, and aquatic species, leveraging its impact on lipid metabolism and the health of the liver and gallbladder in these animals (Wang et al, 2024). The wide application of CDCA and its derivatives in medicine and animal feeds has led to a high demand for CDCA, therefore, the studies on extraction for CDCA from chicken bile became increasingly important.

For extraction of CDCA from chicken bile, the first and most important step in extraction is how to release CDCA from bound bile salts owing to CDCA mainly presents in animal bile in the form of bound bile salts (Fiorucci and Distrutti, 2019). A conventional way of extracting CDCA from animal bile material is saponification process. However, saponification process requires long time consumption (>18h), high temperature (>100 °C) and a large amount of strong alkali reagent added (e.g., sodium hydroxide), which is time-consuming, high energy-consumption and environmentally unfriendly (Hu et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2011). In recent years, some progress in the studies of CDCA on extraction and separation technology have been made using saponification process (Yu et al., 2019). However, there are still many problems on how to extract and purify CDCA efficiently, cheaply and environmentally friendly. Along with the development of technology and the stricter requirement of enviromental protection in recent years, it is necessary to establish a novel process with time-saving, energy conservation, environment-friendly and low cost. In nowadays, enzymatic process has became a research hotspot due to its advantages of high efficiency, environmental friendliness, and low energy consumption (Huang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021b; Sharrel et al., 2017).

Bile salt hydrolase (BSH) is produced during the growth and development of intestinal flora, which can catalytic hydrolysis of conjugated bile acids (Joyce et al., 2014). At present, reports on the screening of BSH from strains of lactic acid bacteria were mainly focused on its role in bile acid metabolism and hepatoenteral circulation (Dong and Lee, 2018; Hernández-Gómez et al., 2021; Khodakivskyi et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a), affecting host lipid metabolism and cholesterol dynamic balance (Joyce et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2020) and improving growth indicators and feed utilization efficiency of edible animals (Korpela et al., 2016). However, there are few studies on the application of active BSH to the extraction of bile acids from animal bile, and only a few patents have been reported (Li et al., 2021). The present research shown that lactic acid bacteria universally contain BSH, and its enzyme activity varies greatly due to various factors such as species, growth environment, etc. Among them, the BSH activity of bifidobacterium is higher than orthers’ (Feng et al., 2021; Tanaka et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 2016). Therefore, the extraction of chicken bile acid could be expected to obtain good results assisted by BSH enzyme from bifidobacterium.

The crude CDCA extracted from chicken bile could not meet the medical demand for high purity CDCA. The crude CDCA was viscous, and contained impurities such as proteins, bile acids with similar structures (Yeh and Hwang, 2021). Therefore, it is difficult to purify CDCA from complex extracts to obtain high-purity products, usually requiring repeated chromatography and recrystallization. During the process, it is inevitable to use a large number of flammable, explosive, corrosive, or toxic reagents, resulting in low product yield (Wan et al., 2011; Hu and Wang, 2016). Macroporous resins possess the merits of good separation efficiency, low cost and reusability, which are very suitable for separating complex components in industry and have been proven by a large number of researches and industrial application practices at present (Xi et al., 2015). They can selectively purify target components or compounds from complex extracts (Han et al., 2021). For example, macroporous resins have been successfully applied to purify functional ingredients, such as saponins (An et al., 2021), flavonoids (Shen et al., 2022), anthocyanins (Chang et al., 2012) and amino acids (Xu et al., 2020) and secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) (Zhuang et al., 2021) from natural resources. Nowadays, a small amount of research has been conducted in the separation and purification of CDCA using macroporous resins (Wan et al., 2011; Xi et al., 2018), wherein, the macroporous resins HZ-802 and D101 had been used to purify CDCA from bile acid extracts. However, the former is expensive and inconvenient to industrial scale production and the resin adsorption mechanism of the latter is uncertainty. Thus, it is necessary to further find an efficient and low-cost macroporous resin for purifying CDCA, optimize the separation process and conduct a detailed study on the adsorption mechanism of macroporous resins.

In this study, in order to extract and purify CDCA from bile, a enzyme-assistant extraction process and macroporous resin purification method were established (Fig. 1). In the enzyme-assistant extraction process, chicken bile was used as raw materials, highly active bile salt hydrolase were prepared and its optimal enzymolysis conditions were studied by using single-factor tests and response surface design experiments, including enzyme dosage, hydrolysis time, pH and temperature. For the purification of CDCA, ten kinds of macroporous resins with different polarities were collected and the most appropriate resin for isolating CDCA was screened. In addition, through static and dynamic adsorption and desorption experiments, the separation performance of the resin had been further explored, the purification process of the macroporous adsorption resin was established. Furthermore, the adsorption performance of the resin had been studied. This study provides theoretical reference and practical guide for the separation of CDCA from crude bile acids.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of an efficient measure for the isolation of chenodeoxycholic acid from chicken biles using enzyme-assisted extraction and macroporous resins refining.

Materials and methods

Apparatus

A high performance liquid chromatography system was used, equipped with a liquid phase pump (LC-2690), automatic sampler (SIL-10A), refractive index detector (RI-2414), a C18 column (Waters, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) and Empower workstation (Waters, Massachusetts, USA). The weighing was performed on an analytical balance (QUINTIX124-ICN, Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany). Flash columns (5 g) were purchased from Santai Technologies Instrument Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China). Epoch enzyme-labeled instrument (Bio-Tek, Winooski, USA). BT100-2J Longer Pump was purchased from Baoding Longer Precision Pump Co., Ltd. (Baoding, China). CBS-B automatic sampling collector was purchased from Shanghai Husi Analytical Instruments Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). UV-6100 Double Beam spectrophotometer (mapada, shanghai, China). 5810R Centrifuges (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). RE-2000B rotary evaporator was purchased from Shanghai Yarong Biochemical Instrument Factory (Shanghai, China). ZQZY-75BS Oscillating incubator was purchased from Shanghai Zhi Chu Instruments Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). G154DWSA utoclave sterilizer (ZEALWAY, Delaware, USA). WM1000-T ultrasonic homogenizer was purchased from Shanghai Weimi Ultrasonic Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Alpha2-4 LSC basic Freeze dryer (CHRIST, Osterode, Germany). FE28 pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Shanghai, China).

Materials

Chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) standard was purchased from Maclin (Shanghai, China). The chicken bile was provided by Jiangsu Runfeng Company (Jiangsu, China). Acetonitrile was of HPLC grade, formic acid, ethanol, phosphoric acid and other chemicals were of analytical grade. Ten macroporous resins (NKA-9, D101, AB-8, DA201, DM301, HP-20, HPD-100, HPD-750, HPD-826 and X-5) were sourced from Maclin and Solarbio. Their physical properties were listed in Table 1. Soak the resin in 95 % ethanol and shake for 24 hours, then rinse with distilled water until there is no alcohol odor, and finally drain the water for use. Ampicillin was purchased from Maclin (Shanghai, China). Dithiothreitol was provided by Solarbio (Beijing, China). Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside was provided by Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). SDS-PAGE Gel Preparation Kit, Kemas Brilliant Blue G-250 and standard molecular weight proteins were purchased from Beyoncé Biotechnology Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). LB medium was purchased from hopebio (Qingdao, China). E. coli BL21(DE3) was provided by TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China).

Table 1.

Physical properties of macroporous resins.

| Name | Skeleton type | Surface (m2/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) | Polarity | Moisture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB-8 | Styrene | 480-520 | 12-16 | Non-polar | 60-70% |

| D101 | Styrene | 480-520 | 25-28 | Non-polar | 65-75% |

| X-5 | Styrene | 500-650 | 28-30 | Non-polar | 56-66% |

| HPD-100 | Styrene | 650-700 | 8.5-9 | Non-polar | 65-75% |

| DM301 | Styrene | ≥330 | 14-17 | Moderate-polar | 70.2% |

| HP-20 | Styrene | 550-600 | 9-10 | Moderate-polar | 65-75% |

| HPD-750 | Styrene-divinylbenzene | 650-700 | 8.5-9 | Moderate-polar | 65-75% |

| HPD-826 | Styrene-divinylbenzene | 500-800 | 9-10 | Moderate-polar | 60-70% |

| DA201 | Styrene | 500-550 | 10-12 | Polar | 65-75% |

| NKA-9 | Styrene nitrile | 500-550 | 10-12 | Polar | 65-75% |

Methods

High Performance Liquid Chromatography conditions

A inverted C18 (waters, 150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) chromatographic column was used, with column temperature, detection wavelength, and injection volume set at 30 °C, 410 nm, and 20 µL. Acetonitrile-0.1 % formic acid water (60:40) was used as the mobile phase for isocratic elution, with a flow rate controlled at 1.0 mL/min.

Accurately weighed 100 mg of CDCA, placed it in a 10 mL centrifuge tube, added a little methanol to dissolve it completely, then transfered the solution into a 10 ml volumetric flask and volumed it with methanol, thus a 10 mg/mL CDCA solution was prepared. Finally, dilute the stock solution to different concentrations as 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 mg/mL. The test samples were tested under the above chromatographic conditions. Quantitative analysis was carried out using the standard curve method. The standard curve equation (y=133985X-5935.6, R2=0.999) was obtained, and the peak area of CDCA showed a good linear relationship with concentration in the range of 0-10 mg/mL.

Preparation of BSH

The gene sequence of bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium infantis KL412 (GenBank ID: AY530821.1) was obtained from the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The bile salt hydrolase gene was optimized according to the codon preference of E. coli) and synthesized by GENEWIZ Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The obtained gene was cloned into the E. coli expression vector (pET-22b (+)) to obtain a recombinant plasmid (pET-22b (+) - BSH), and then transformed the recombinant plasmid into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The transformed cells were cultured in Luria Bertani (LB) broth at 37 °C and 200 rpm until the bacterial solution absorbance (A600nm) reached 0.8. Then the cells were induced using 0.2 mM inducer (IPTG, isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside) at 20 °C for another 22 hours.

The induced cell suspensions were centrifuged at 10,000 r/min and 4 °C for 10 min, the precipitated cells were obtained and washed twice with 0.01 M PBS (pH 6) containing 10 mM dithiothreitol and then resuspended and adjusted the cells solution with the PBS until the cells solution had an 10 of absorbance (600 nm) value. The cell resuspension was disrupted by ultrasonic cell disruptor for 10 min at 2:3 duty cycle and 75 % amplitude in an ice bath. Then, the cellular lysate was centrifuged for 10 min (10,000 r/min at 4 °C) and the supernatant was obtained and then freeze-dried for use. Finally, the expression results of BSH enzyme in recombinant bacteria were validated through SDS-PAGE analysis and the activities of recombinant expressed BSH enzyme was evaluated by ninhydrin method (Dong et al., 2014), via measuring the content of free amino acids released by enzymatic hydrolysis of bile salts. Specific operations refered to literature methods (Tanaka et al., 1999). An enzyme activity unit was defined as: BSH enzyme hydrolyzes bile salts and can release 1 µmol of amino acids per minute.

Extraction of CDCA

Enzymatic extraction of CDCA: A certain amount of chicken bile was put into a beaker, the pH was adjusted to the optimal value of the reaction enzyme, then the bile salt hydrolase was added, and finally the beaker was put into a constant temperature water bath for enzymatic hydrolysis. The reaction was terminated by heating at 80 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, butyl ester was added to the enzymolysis reaction solution as an extractant to extract bile acids. The upper solution was taken, concentrated by rotary evaporator and a bile acids extract extract was obtained and dried.

Saponification method for extracting CDCA: 100 mL bile was divided into 5 equal parts and were added into 35 mL pressure-resistant tubes respectively, and 2 g NaOH was added to each tube, then boiled in an oil bath at 110 °C for 22 h. Samples were taken at 5 h, 16 h, 18 h, 20 h, 22 h, respectively, and the saponification was terminated by ice bath cooling. The samples pH were adjusted to 2 ∼ 3 for precipitation, centrifugation, and the precipitation layer were obtained and washed twice with water and then dried. Finally, the bile acids extract yields and their CDCA contents were calculated and measured.

Optimal process for enzymatic extraction of CDCA

Single factor experiments

To investigate the effect of various enzymatic hydrolysis process conditions on the yield of CDCA through a single factor experiment. The enzymatic hydrolysis time was fixed for 3 hours, and the extraction variables were set to A (enzyme dosage: 1, 2, 6, 10, 14 mg/mL), B (pH: 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5), and C (reaction temperature: 27, 32, 37, 42, 47 °C).

Box Behnken experimental design

Based on the single factor experiments, in order to fully investigate the optimal extraction conditions for CDCA, the response surface methodology (RSM) was used to further explored the effects of enzyme dosage, pH, and reaction temperature on the yield of CDCA. Using enzyme dosage (A, g/g), pH (B) and extraction temperature (C, °C) as independent variables and the CDCA yield (Y) was used as the response value for the design experiment. Then, a three-level-three-factor Box Behnken factor design was applied to determine the optimal combination of variables for extracting CDCA from chicken bile using enzymatic hydrolysis.

The effect of three independent variables, dosage of enzyme (0.01–0.05 g/g), extraction pH (3.5–5.5) and enzymolysis temperature (32–42 °C) on CDCA yield was investigated to obtain the optimal extraction conditions for CDCA. Experimental factors and levels are shown in Table S1.

Purification of CDCA

Macroporous resins pretreatment

100g of 10 macroporous resins, including NKA-9, D101, AB-8, DA201, DM301, HP-20, HPD-100, HPD-750, HPD-826 and X-5 were taken into empty column and immersed in purified water. The resins were washed by flushing solvent (95 % ethanol) until the effluent color turned colorless, then washed by purified water until the the flushing water becomed odorless. Finally, the macroporous resins were abtained and stored in water for later use.

Static adsorption and desorption tests

Different types of macroporous resins pre-processed were placed into 30 mL penicillin bottles (1 g of each resin), and 15mL of CDCA solution (5 mg/mL) was injected into it. then, the bottles were capped and shaked at a constant temperature shaking table at 20 °C with a speed of 100 rpm for 18 h to ensure the establishment of adsorption equilibrium. After that, residual CDCA in the adsorbed solutions were detected, the adsorption capacities of all tested resins were calculated. The resins after adsorbing CDCA were rinsed three times with purified water to remove residual solvents. Then, 8 mL of 95 % ethanol was added into each bottles to desorb CDCA at 20 °C and 100 rpm for 4 h and the desorption ratios of all resins were measured. The amount of CDCA bound on resins (Qe, mg/g) and the ratios of CDCA desorpted from resins (D, %) were calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where C0, Ce, and Cd are initial CDCA concentration, equilibrium CDCA concentration and desorption solution concentration (g/L), V0 and Vd are initial CDCA solution volume and desorption solution volume (mL), and W is the the adsorbent dosage (g)..

Selection of adsorption and elution solution for chromatography

15 mL of CDCA solutions (5 mg/mL) dissolved in different adsorption solvents (40 %, 50 %, 60 %, 70 % and 80 % ethanol) were added into penicillin bottles containing 1.0 g of wet AB-8 adsorbent, and then shaked at 20 °C for 24 h to bound CDCA onto the adsorbent. After adsorption, the equilibrium CDCA concentrations were tested and the amounts of CDCA bound on the AB-8 resin were calculated based on mass balance.

The 5 mg/mL CDCA solutions (dissolved in 40 % ethanol) pH were adjusted to 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 6, 6.5 and 8 with H3PO4 and ammonia. The pH-adjusted CDCA solutions were added into penicillin bottles containing 1.0 g of wet AB-8 adsorbent and then achieved adsorption equilibrium. The equilibrium CDCA concentrations were tested and the amount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin under different pH conditions were calculated based on mass balance.

210 mL of CDCA solution (5 mg/mL) dissolved in 40 % ethanol was added into conical flask containing 14 g of wet AB-8 adsorbent, and followed the aforementioned steps to bound CDCA on the AB-8 resin until achieved adsorption equilibrium. The AB-8 resin bound CDCA was rinsed three times with purified water to remove the residual solution. Then, the AB-8 resin bound CDCA was taken and added into six penicillin bottles with an amount of 1 g per bottle. After that, a series of 8 mL ethanol solutions with different concentrations (50 %, 60 %, 70 %, 80 %, 90 % and 95 %) were added into each penicillin bottle, and shaked for desorption at 20 °C and 100rpm for 8 hours to desorb CDCA from the AB-8 resin. The desorption mounts of CDCA were measured and the desorption recovery rates were calculated based on mass balance.

Adsorption isotherms

Determination of the adsorption isotherms of AB-8 for CDCA using 40% ethanol as the adsorption solvent were conducted at pH 3.5. 50 mL of CDCA solutions (using 40% ethanol as the adsorption solvent) with different initial concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 g/L) were added to a penicillin bottles containing 1 g of wet AB-8 resin per bottle, and then oscillated at different temperatures (20 °C, 30 °Cand 40 °C) and 100 rpm for 18 h. The adsorption capacities of CDCA on macroporous resin under different temperatures and initial concentrations were calculated based on mass balance. Described the adsorption behavior between the adsorbent and adsorbate using the following two commonly used theoretical models (Patiha et al., 2016):

The Langmuir equation:

| (3) |

The Freundlich equation:

| (4) |

Where Qe and Ce are the amount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin and equilibrium CDCA concentration, Qm (mg/g) is the theoretical maximum amount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin, while KL (L/mg), KF (mg/g), and 1/n are Langmuir constant, Freundlich constant, and empirical constant, respectively.

Dynamic adsorption and desorption

The dynamic adsorption and desorption tests were conducted in an empty plastic column (12 g), and the prepared AB-8 resin was loaded into the empty column tube through wet-loaded method. The bed volume (BV) of the resin is 6 mL (equivalent to 5 g of macroporous resin).

CDCA extract solutions (dissolved in 40.0 % ethanol) with diferent loading concentrations (CDCA comtent: 3.85 mg/mL and 5.72 mg/mL) were pumped through AB-8 macroporous resin column at a flow rate of 2 BV/h using a peristaltic pump. The effluents were collected through an automatic sampler with 0.5 BV per tube. The CDCA contents in the effluents were measured and the amounts of CDCA bound on the AB-8 resin were calculated to study the relationship between adsorption capacities and sample concentration. In addition, the CDCA extract solutions (5 mg/mL) were pumped through the AB-8 resin column at different flow rates (2 BV/h, 4 BV/h and 6 BV/h). the CDCA contents in effluents were tested and the amounts of CDCA bound on the AB-8 resin were calculated to investigate the relationship between adsorption capacities and flow rate. Finally, the adsorption curve was drawed.

After that, the loaded column was washed with purified water (2BV) to remove residual solution and then eluted gradiently with different concentrations of ethanol solutions (40 %, 50 % and 60 %) at a flow rate of 1 BV/h. The effluents were collected through an automatic sampler with 0.5 BV per tube. the qualitative and quantitative analysis of CDCA in the eluent was carried out through TLC and HPLC.

Results and discussion

Preparation and identification of enzyme

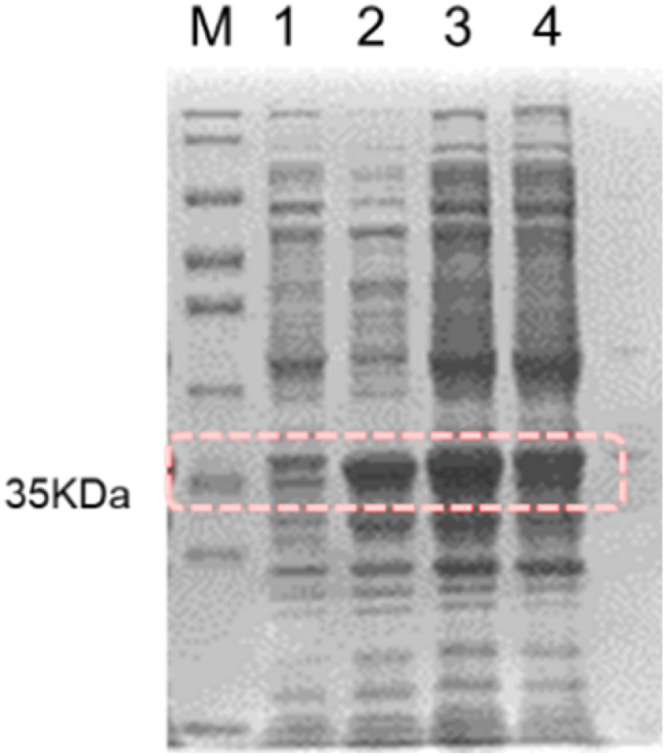

In this study, bile salt hydrolase was obtained by recombining E. coli with BSH-gene and its inducing expression. The activities of bile salt hydrolase on GCDCA and TCDCA substrates were tested and the results showed that the activities of BSH on GCDCA and TCDCA substrates were 4.96 ± 0.32 U/mg and 3.07 ± 0.031 U/mg, respectively. In addition, the crude BSH was analyzed comparatively using SDS-PAG, a specific band appeared at a molecular weight of about 35 KDa (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the known relative molecular mass of BSH, implied that bile salt hydrolase was expressed.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE of recombinant protein. M: Standard Marker; 1: un-induced E.coli BL21 (DE3) (pET-22b (+)) products; 2: the supernatant obtained by breaking cell walls of induced E.coli BL21 (DE3) (pET-22b (+)); 3: induced E.coli BL21 (DE3) (pET-22b (+)); 4: the precipitation obtained by breaking cell walls of induced E.coli BL21 (DE3) (pET-22b (+)).

Optimization of process for enzyme treatment extraction of CDCA

The effect of enzyme dosage on the extraction

The effect of enzyme dosage on the yield of CDCA was shown in Fig. S1a when hydrolysis conditions at 37 °C and pH 5.5 for 1.5 h. As the enzyme dosage increased, the contact between substrate and enzyme became more sufficient, and the reaction became more complete. When the enzyme concentration increased from 0.005 g/g to 0.03 g/g, the yield of CDCA was significantly increased (P<0.05). When the enzyme concentration increased from 0.03 g/g to 0.05 g/g, the increase in CDCA yield was not significant (P>0.05), this may because the substrate was limited and the reaction had reached saturation. Continuing to increase the enzyme concentration at this time would cause waste of biological enzymes. Therefore, the three enzyme dosages of 0.01 g/g, 0.03 g/g and 0.05 g/g could be selected to be optimized for response surface experiments.

Effect of pH on activity of BSH

The effect of pH on the yield of CDCA was shown in Fig. S2b when hydrolysis conditions at 0.03 g/g enzyme dosage and 37 °C for 1.5 h. From pH 4.5 to 5.0, with the pH increased, the yield of CDCA was significantly increased (P<0.05), peaked at pH 5.0. Within the range of pH 5.0-6.5, as the pH increased, the yield of CDCA showed a significant downward trend (P<0.05), mainly due to the gradual decrease of bile salt hydrolytic enzyme activity and hydrolysis effect. Due to the continuous increase in pH during the enzyme reaction, it was necessary to adjust the pH of the reaction solution timely during the reaction process to ensure that the reaction remained within the optimal pH range. Based on the above single factor analysis, the value of pH 4.5, 5.0 and 5.5 were selected to be optimized for the RSM experiments for enzyme hydrolysis.

The effect of temperature on the extraction of CDCA

The effect of temperature on the yield of CDCA was shown in Fig. S2c when hydrolysis conditions at 0.03 g/g enzyme dosage and pH 5.5 for 1.5 hours. As the temperature increased during the period when the temperature rose between 27 °C and 37 °C, the yield of CDCA showed a rising trend and peaked at 37 °C. When the temperature exceeded 37 °C, as the temperature increased, the yield decreased. During the temperature rised between 27 °C and 37 °C, enzyme activity was improved, the probability of the collision between enzyme and substrate was increased, and hydrolysis was strengthened. However, When the temperature rised by more than 37 °C, it had a negative impact on enzyme activity. Therefore, 32 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C could be selected to be optimized for the RSM experiments for enzyme hydrolysis.

Response surface optimization of extraction

Based on the aforementioned single factor experimental analysis, taking the yield of CDCA as responses, and three factors (A: enzyme dosage; B: pH; C: extraction temperature) and three levels were selected for the Box-Behnken design, as shown in Table S2. RSM was used to optimize the enzymatic treatment of chicken bile. 17 rounds of testing were conducted to optimize three parameters for extracting CDCA from chicken bile. The experimental results were shown in the Table S2 and obtained the quadratic multiple regression equation of the model: Y1=5.19+0.70A-0.076B+0.15C+0.060AB-0.031AC+0.25BC-0.77A2-0.47B2-0.33C2. The absolute value of each coefficient indicates the influence of each factor on the yield of CDCA. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the model using Design Expert 8.0.6 software, the results were as shown in Table 2. The analysis of variance results indicated that the F value of the model was 1188.23, and the P value < 0.0001, indicated that the model was extremely significant. P value of the lack of fit was 0.5345 (p>0.05) indicated that the difference was not significant, and the correction coefficient R2Adj=0.9172, indicated that the model had high reliability. Enzyme dosage (A), pH (B), temperature (C), interaction term between enzyme dosage and pH (AB), interaction term between enzyme dosage and hydrolysis temperature (AC), interaction term between pH and hydrolysis temperature (BC), and quadratic terms of each factor all significantly affected the response value, indicated that these factors affected the yield of CDCA significantly. According to the F value judgment, the order in which various factors affected the yield of CDCA was: enzyme dosage (A)>temperature (C)>pH (B). Among the interaction terms, AB and BC had a extremely significant effect on the model (p<0.05) and AC had no significant effect on the model (p >0.05).

Table 2.

Analysis of variance of the experimental results of the Box–Behnken design.

| Source | Sum of square | df | Mean square | F value | p-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | 8.70 | 9 | 0.97 | 1188.23 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| A | 3.91 | 1 | 3.91 | 4806.63 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| B | 0.046 | 1 | 0.046 | 56.58 | 0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| C | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 221.67 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| AB | 0.014 | 1 | 0.014 | 17.54 | 0.0041 | ⁎⁎ |

| AC | 0.00376 | 1 | 0.00376 | 4.62 | 0.0686 | |

| BC | 0.24 | 1 | 0.24 | 300.43 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| A2 | 2.51 | 1 | 2.51 | 3089.81 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| B2 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.94 | 1160.48 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| C2 | 0.45 | 1 | 0.45 | 559.37 | <0.0001 | ⁎⁎ |

| Residual | 0.005694 | 7 | 0.008134 | - | - | - |

| Lack of fit | 0.002217 | 3 | 0.007390 | 0.85 | 0.5345 | - |

| Pure Error | 0.003477 | 4 | 0.008692 | - | - | - |

| Cor total | 8.70 | 16 | - | - | - | - |

| R2=0.9586 R2Adj=0.9172 | ||||||

Extremely significant level

According to the equation derived, the relationships between the response of each factor and the experimental level were visualized using 3D response surface plots (Fig. 3). From the graph, it can see the best condition of enzyme treatment extraction, which condition with 0.04 g/g of enzyme dosage, 38.04 °C of temperature and 5.0 of pH value, the yield of CDCA can reach maximum (5.39%). Under the above optimized conditions, the experimental yield of CDCA was 5.32%, which was very close to 5.39% of the predicted value. In addition, the purity of CDCA was determined to be 51.7%.

Fig. 3.

Response surfaces and contour plots show the effects of dosage of enzyme (A), pH (B) and enzymolysis temperature (°C) on the yield of CDCA. (a) Dosage of enzyme and pH; (b) Dosage of enzyme and enzymolysis temperature; (c) Enzymolysis temperature and pH.

Saponification

Through the saponification of chicken bile for 5, 16, 18, 20 and 22 hours, the yield of CDCA were investigated, and the change trendence of the yield of CDCA at different saponification times was analyzed, the results were shown in Table S3. As saponification time extended, the yield of CDCA increased and peaked at 22 h with 5.32% of the yield . When the saponification time ranged from 0 to 5 th hours, the yield of CDCA increased quickly with 4.43%±0.35% of the yield at 5th hour. As the saponification time between 6 th to 20 th hour, the yield growth had slowed down, the yield only increased from 4.43 %±0.35 % to 5.25 %±0.12 %, and between 20th to 22th hour, there was almost no increase in yield, with 5.32 %±0.21 % of the yield at 22th hour, indicated that saponification was almost complete in 20 hours, which is close to 22 h of the saponification time commonly used in industrial process[8]. The saponification process needed a long time and under 110 °C of high temperature, which was inconvenient for technical personnel to operate and high energy consumption. In addition, a large amount of strong alkali (about 10%) was used in the process, which is unfriendly to the environment.

Static adsorption and desorption

Adsorbent capability of different resins

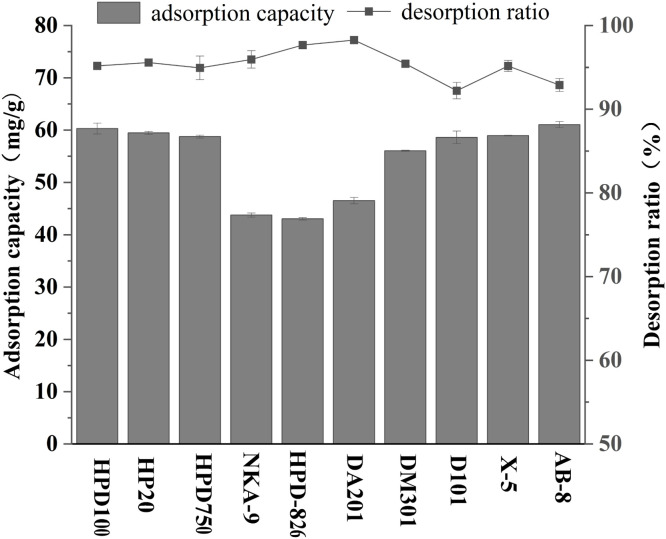

It was widely known that the adsorption capacities and selectivities of adsorbents could be influenced by their polarity, pore size, pore volume and surface area (Zhang and Yan, 2004). In order to screen suitable macroporous resins for the separation and purification of CDCA, we conducted static adsorption and desorption experiments on ten macroporous resins, including 4 non polar resins (HPD-100, AB-8, D101, and X-5), 3 mid polar resins (HP-20, HPD750 and DM301) and 3 polar resins (NKA-9, HPD826 and DA201), and the experimental results were shown in Fig. 4. In the experiments, non polar resins and mid polar resins showed higher adsorption capacities for CDCA than polar resins. This result appeared to be consistent with the principle of similar compatibility in resin adsorption selectivity, CDCA is composed of a non polar steroidal mother core skeleton, and the weak polarity of CDCA is the main factor affecting its adsorption (Zhou et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2016). The adsorption and desorption properties are related to the characteristics of the resin and the chemical characteristics of the solute (Liu et al., 2005). HPD-100 and AB-8 resins showed the highest comprehensive capacities (P<0.05), with adsorption capacities ranging from 60.30 ± 1.04 to 61.06 ± 0.57 mg/g. In addition, the desorption experiment showed that all the ten types of macroporous resins used in the experiment achieved a desorption rate of over 90 % for CDCA. Therefore, taking into account price and other factors, AB-8 resin was selected as the most suitable resin and used in further experiments.

Fig. 4.

Static adsorption capacities and desorption ratios of ten macroporous resins.

Effect of permeate pH and adsorption kinetics

The pH of the sample solution had a significant impact on the adsorption performance of the resin. The effect of pH on the mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin was shown in Fig. S2a. As the pH of the sample solution increased, the adsorption capacities of AB-8 resin decreased, this trend was similar to the study by Xi[26]. As the pH value of the CDCA solution was adjusted to 3.5, the mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin peaked with 72.65 ± 0.58 mg/g. It was found that there was no significant difference in adsorption capacity between pH 2.5 and pH 3.5 (P>0.05). When the pH value of the CDCA solution increased from 3.5 to 8.0, the mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin rapidly decreased. As the pH value of the solution was adjusted to 8.0, the adsorption capacity reached the lowest mount with 53.97 ± 0.28 mg/g (P<0.05). CDCA belongs to weakly acidic compound and gets better solubility as a salt under alkaline conditions, this could explain why CDCA is easily adsorbed under acidic conditions. According to the above investigation experiments, pH 3.5 was selected as the optimal solution pH value for CDCA purification.

In addition, the adsorption kinetics curve of the mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin at 30 °C was drawn and shown in Fig. S2d. The adsorption capacity rapidly increased in the 2 hours, then the growth rate slowed down and reached adsorption equilibrium in about 3 hours.

Effect of loading solvent concentrations and eluent concentrations on the mount of CDCA bound AB-8 resin

The effects of CDCA loading solutions dissolved with a series of different ethanol (40%, 50%, 60%, 70% and 80%, v/v) on the mount of CDCA bound AB-8 resin were investigated and the results were as shown in Fig. S2b. With the ethanol concentration rose, the mount of CDCA bound AB-8 resin decreased, and the CDCA loading solution dissolved with 40% ethanol obtained highest adsorption capacity of 71.84 ± 0.27 mg/g. Due to CDCA is insoluble in water and soluble in ethanol, if the proportion of water in loading solvent is too high, CDCA will precipitate. However, if the proportion of ethanol is too high, it will negatively effect the resin's adsorption performance. Therefore, 40% ethanol was selected as the most suitable ethanol concentration.

The effects of different ethanol (50 %, 60 %, 70 %, 80 %, 90 % and 95 %, v/v) on the desorption capacities were investigated and the results were as shown in Fig. S2c. As the ethanol concentration rose, the mount of CDCA desorped from AB-8 resin increased and reached the highest adsorption ratio with 92.32 ± 1.51 % using 95 % ethanol as elution.

Adsorption isotherms

The isothermal adsorption equations of AB-8 resin for CDCA were researched at three different temperatures and fit by two classical models (Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm) (Vijayakumar et al., 2012), the results were shown in in Fig. 5a. As the temperature rose, the mount of CDCA bound on the AB-8 resin decreased. The mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin peaked with the value of 150.90 ± 0.58 mg/g (P<0.05) at 20 °C and 6 g/L concentration of CDCA solution. The two classical models demonstrated analogous trends, with their respective parameters and determination coefficients presented in Table S4. The correlation coefficients suggested that both models were effective in analyzing the adsorption mechanism of CDCA on AB-8 resin. It was observed that the adsorption of CDCA onto AB-8 resin presented characteristics of both monolayer and multilayer adsorption (Sandhu and Gu, 2013). Furthermore, the R-squared values for the Langmuir model were consistently higher than those for the Freundlich model across all tested temperatures, suggesting that the Langmuir model provided a better description of the adsorption behavior of CDCA on AB-8 resin. The decreasing trend of Qm and KF values with increasing temperatures indicated that the adsorption of CDCA by AB-8 resin was an exothermic process, which is advantageous for adsorption at lower temperatures (Mota et al., 2019). Additionally, the constant 1/n values, derived from the Freundlich isotherm and all less than 1, confirmed that AB-8 resin has a strong affinity for CDCA, indicating efficient absorption (Aljeboree et al., 2017).

Fig. 5.

Isothermal adsorption curves of AB-8 for CDCA at different temperatures (a) and dynamic absorption breakthrough curves of CDCA adsorption at different loading concentrations (b) and flow rates (c).

Dynamic adsorption and desorption

The study of dynamic adsorption and desorption can effectively describe the adsorption features of the AB-8 for CDCA. In this experiment, 5 % of the CDCA content in the sample solution was defined as a breakthrough point in the elution, which can be used to determine the most suitable loading concentration and flow rate for dynamic adsorption.

According to isothermal adsorption curves of the AB-8 on the adsorption of CDCA, the loading concentrations can affects adsorption performance. So different loading concentrations of CDCA were investigated for the CDCA adsorption. Here, concentrations 5.72 mg/mL and 3.85 mg/mL were examined and their breakthrough curves are shown in Fig. 5b. The curves showed that the breakthrough point appeared at 13 BV for high loading concentration (5.72 mg/mL), and later at 18 BV for low loading concentration (3.85 mg/mL). However, different concentrations had little effect on the adsorption capacities. The mass transfer zones of different loading concentrations were highly similar, with 83.16 mg/g of adsorption capacities at 3.85 mg/mL and 89.23 mg/g at 5.72 mg/mL. The effect of loading concentration on the adsorption capacity was not significant. When the concentration of the loading solution was high, the time to reach equilibrium was short, so it is more advantageous to choose a higher concentration sample solution for loading in the experiment.

The flow rate of the sample solution affects the interaction between solute and resin, thereby affecting the mount bound on the resin (Liu et al., 2009). The effect of flow rate on the adsorption process during sample loading was shown in Fig. 5c. The breakthrough point appeared at 17.5 BV at the lowest flow rate (2 BV/h), and the optimal adsorption time at 2 BV/h was 8.75 h, which was 1.67 times and 2.05 times longer than the adsorption time at 4 BV/h and 6 BV/h, respectively. The higher the flow rate and the earlier the breakthrough point appeared, indicated that some CDCAs lost without being adsorbed by the resin due to the high flow rate. The results implied that the lower the flow rate, the greater the dynamic adsorption capacities. The adsorption capacity was 80.85 mg/g at a flow rate of 2 BV/h, 44.1 mg/g at a flow rate of 4 BV/h, and 34.98 mg/g at a flow rate of 6 BV/h. The mobile phase permeated slowly at low flow rates, allowing sufficient time for CDCA to fully diffuse to the binding site. From the perspective of adsorption capacities, the flow rate during sample loading was controlled at 2 BV/h.

CDCA purifification

When purifying CDCA through AB-8 resin, consideration should be given to the separation of CDCA and impurities. The main impurity in the CDCA extraction solution was CA. CDCA and CA have similar structures with only one hydroxyl group different. There are two hydroxyl groups in CDCA, while there are three hydroxyl groups in CA. Therefore, CDCA has stronger hydrophobicity than CA. CDCA is more easily adsorbed on hydrophobic adsorbents and is more difficult to elute. The concentration of eluent is crucial for purification of CDCA, the selection of elution solvent was shown in Fig. 6a. When using 50% ethanol to elute CDCA in dynamic desorption, although CDCA was eluted earlier from the resin column, the elution curve of CDCA and impurity CA partially overlapped, making it difficult to effectively separate. When using 30 % ethanol for elution, CDCA and CA were eluted in small amounts, making it difficult to separate and time-consuming. Therefore, 40 % ethanol was selected as the starting ethanol concentration for gradient elution.

Fig. 6.

Dynamic desorption ratios of AB-8 macroporous resins. (a) Investigation of gradient ethanol dolution concentration. (b) Gradient elution curve of CDCA. 0–24 BV was obtained by eluting with 40.0% ethanol, and 25–45 BV was obtained by eluting with 50.0% ethanol. (c) The amount of CDCA in the elution fractions detected by TLC. S was a CDCA extract sample before purification, 1–24 (40%) and 0.5–22 (50%) were the BV numbers of collecting tube was eluted by 40% and 50.0% ethanol, 3 mL (0.5 BV) for each tube.

The AB-8 resin column was loaded with the crude extract of chicken bile acid, which prepared by the optimization method obtained in 3.2 and then rinsed with 40 % ethanol and then 50% ethanol, successively, the CDCA bound on the AB-8 resin was eluted and purified. Detection of elution fractions was carried out by the CDCA contents of each elution fraction were measured by HPLC (Fig. 6b) and TLC (Fig. 6c). The result showed that impurity CA was eluted out in 12 BV of 40.0 % ethanol and purified CDCA were eluted between 13 BV and 50 BV. The purity of CDCA in the crude extract was 51.7 % and the purity of CDCA purified was 91.4 %. The crude extract was purified using AB-8 macroporous resin, resulting in a 39.7 % increase in CDCA purity and a 87.8 % recovery rate. Thus, AB-8 resin could be used as effective adsorbent to purify CDCA.

Conclution

This study established a process route for enzymatic extraction of CDCA from chicken bile, and optimized the extraction conditions through single factor experiments and Box Behnken response surface methodology. The results showed that the yield of CDCA significantly improved after optimization. The BBD model of response surface methodology could predict the yield of CDCA, providing a valuable analytical tool for evaluating different process conditions. The feasibility of enzymatic extraction of chicken bile acid was investigated, and two extraction methods, enzymatic method and saponification method were compared. Biological enzymatic extraction of chicken bile acid has obvious effects and outstanding advantages than saponification method. Such as active enzymes could replace strong bases and work at lower temperatures (about 38 °C). These conditions were mild and easy to operate, low energy consumption, environmentally friendly and more convenient for the subsequent purification of CDCA. Here, we further optimized the enzymatic hydrolysis conditions to obtain the optimal conditions parameters, as follows: 0.04 g/g of the enzyme dosage, pH 5.0 and 38 °C of the temperature. Under these conditions, the yield of CDCA extracted from chicken bile achieved 5.32 %, which was equivalent to the saponification extraction by 22 h. This indicated that the enzymatic extraction of CDCA from chicken bile was feasible and had strong practical significance and reference value.

The CDCA extract obtained by enzyme-assisted extraction was further refined through a macroporous resin purification process. The preferable resin and its adsorption kinetics, adsorption isotherms, solution pH, and adsorbent elution conditions were investigated through static adsorption and desorption experiments. As a result, AB-8 macroporous resin was selected from 10 kinds of resins to be suitable for purifying CDCA. In adsorption experiment of AB-8 resin, the mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 macroporous resin rapidly increased in 2 h and reached adsorption equilibrium at 3th hours. The maximum mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 resin was achieved at pH 3.5, and for resulting in good results, 40% ethanol was selected as the adsorption solvent for loading; The maximum mount of CDCA bound on AB-8 decreased with increasing temperature, and adsorption was an exothermic process. Low temperature was conducive to the adsorption of CDCA. The loading concentration and flow rate of the CDCA initial solution, and gradient elution conditions were investigated via dynamic adsorption and desorption experiments. The loading concentration had little effect on the adsorption capacity and flow rate had a negative effect on the adsorption capacity, the dynamic adsorption capacity was higher at lower flow rate. Finally, the parameters of purification process were determined to be 5.72 mg/mL of loading concentration of chicken bile acid, 2 BV/h of loading flow rate and gradient elution with 40 % and 50 % ethanol. The purity of crude bile acid extract and purified CDCA samples were detected by HPLC. The purity of CDCA in crude chicken bile extract was 51.7 %, while the purity of purified CDCA sample was 91.4 %, purity increased 39.7 % and with a recovery rate of 87.8 %. This indicated that AB-8 resin, as an adsorption material for CDCA purification, had good purification ability and could be used for further industrial production.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-41) and Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(24)1020).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2024.104573.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Aljeboree A.M., Alshirifi A.N., Alkaim A.F. Kinetics and equilibrium study for the adsorption of textile dyes on coconut shell activated carbon. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:S3381–S3393. [Google Scholar]

- An S.J., Niu D., Wang T., Han B.K., He C.f., Yang X.L., Sun H.Q., Zhao K., Kang J.F., Xue X.H. Total saponins isolated from corni fructus via ultrasonic microwave-assisted extraction attenuate diabetes in mice. Foods. 2021;10:670. doi: 10.3390/foods10030670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X.L., Wang D., Chen B.Y., Feng Y.M., Wen S.H., Zhan P.Y. Adsorption and desorption properties of macroporous resins for anthocyanins from the calyx extract of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) J. Agr. Food Chem. 2012;60:2368–2376. doi: 10.1021/jf205311v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpechot C., Carrat F., Bonnand A.M., Poupon R.E., Poupon R. The effect of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on liver fibrosis progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2000;32:1196–1199. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzinger R.G., Hofmann A.F., Schoenfield L.J., Thistle J.L. Dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by chenodeoxycholic acid. N. Engl. J. Med. 1972;286:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197201062860101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.X., Zhang J., Lee B., Du G.C., Chen J., Li H.Z. Secretory expression of bile salt hydrolase gene from Secretory expression of bile salt hydrolase gene from Lactobacillus plantarum BBE7 in Pichia pastoris. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2014;20:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Lee B.H. Bile salt hydrolases: structure and function, substrate preference, and inhibitor development. Protein Sci. 2018;27:1742–1754. doi: 10.1002/pro.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Ding Y., Guo Y.B., Liang H.Z., Liu G.Q., Ai L.Z., Wang G.Q. Research progress on the cholesterol-lowering effects of bile salt hydrolase. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;37:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S., Distrutti E. Chenodeoxycholic acid: an update on its therapeutic applications. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2019;256:265–282. doi: 10.1007/164_2019_226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floreani A., Mangini C. Primary biliary cholangitis: old and novel therapy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018;47:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Wei L. Application progress of ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of cholestatic diseases. Infectious Disease Inf. 2008;21:213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Chio C., Ma T., Kognou A., Qin W. Extracting flavonoid from ginkgo biloba using lignocellulolytic bacteria paenarthrobacter sp. and optimized via response surface methodology. Biofuel. Bioprod. Bior. 2021;1:867–878. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Gómez J.G., López-Bonilla A., Trejo-Tapia G., Ávila-Reyes S.V., Jiménez-Aparicio A.R., Hernández-Sánchez H. In vitro bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity screening of different probiotic microorganisms. Foods. 2021;10:674. doi: 10.3390/foods10030674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.Z., Feng N., Zhang J.Q. Study on the factors influencing the extraction of chenodeoxycholic acid from duck bile paste by calcium salt method. J. App. Chem. 2018;2018:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.Z., Wang J.M. Preparation and application of chenodeoxycholic acid and its derivatives. Prog. Chem. 2016;28:814–828. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Lu F.Y., Wu Y.J., Wang D.Y., Xu W.M., Zou Y., Sun W.Q. Enzymatic extraction and functional properties of phosphatidylcholine from chicken liver. Poultry Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce S.A., MacSharry J., Casey P., Kinsella M.E.F., Shanahan F., Hill C., Gahan C.G.M. Regulation of host weight gain and lipid metabolism by bacterial bile acid modification in the gut. Pnas. 2014;111:7421–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323599111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodakivskyi P.V., Lauber C.L., Yevtodiyenko A., Bazhin A.A., Goun E.A. Noninvasive imaging and quantification of bile salt hydrolase activity: from bacteria to humans. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eaaz9857. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpela K., Salonen A., Virta L.J., Kekkonen R.A., Forslund K., Bork P., Vos W.M.D. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. L., T. Shen, X. Y. Du, and W. Cheng. 2021. A kind of method that utilizes bovine bile high-efficiency enzyme to extract bile acid. CN Pat. No. CN112322684A.

- Liu X.P., Li X.N., Xu H.X. Chem. Ind. Press; Beijing, China: 2005. Separation Engineering of Chinese Herb Medicine; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.F., Shan L., Wang X.G. Purification of soybean phosphatidylcholine using 113-III ion exchange macroporous resin packed column chromatography. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 2009;86:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Makino I., Shinozaki K., Yoshino K., Nakagawa S. Dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by ursodeoxycholic acid. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1975;72:690–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota M.I.F., Barbosa S., Pinto P.C.R., Ribeiro A.M., Ferreira A., Loureiro J.M., Rodrigues A.E. Adsorption of vanillic and syringic acids onto a macroporous polymeric resin and recovery with ethanol: water (90:10 %V/V) solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019;217:108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Patiha E.H., Hidayat Y., Firdaus M. The langmuir isotherm adsorption equation: the monolayer approach. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016;107 [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu A.K., Gu L. Adsorption/desorption characteristics and separation of an-thocyanins from muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) juice pomace by use of macroporous adsorbent resins. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2013;61:1441–1448. doi: 10.1021/jf3036148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrel R., Mohandas A., Embalil M.A., Raveendran S., Parameswaran B., Ashok P. Recent advancements in the production and application of microbial pectinases: an overview. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio. 2017;16:381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Shen D.B., Labreche F., Wu C., Fan G.J., Li T.T., Dou J.F., Zhu J.P. Ultrasound-assisted adsorption/desorption of jujube peel flavonoids using macroporous resins. Food Chem. 2022;368 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Doesburg K., Iwasaki T., Mierau I. Screening of lactic acid bacteria for bile salt hydrolase activity. J. Dairy Sci. 1999;82:2530–2535. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar G., Tamilarasan R., Dharmendirakumar M. Adsorption, kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies on the removal of basic dye Rhodamine-B from aqueous solution by the use of natural adsorbent perlite. J. Mater. Env. Sci. 2012;3:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wan J.F., He J.M., Cao X.J. A novel process for preparing pure chenodeoxycholic acid from poultry bile. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2011;18:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.Q., Yu H.N., Feng X., Tang H.Y., Xiong Z.Q., Xia Y.J., Ai L.Z., Song X. Specific bile salt hydrolase genes in Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 and relationship with bile salt resistance. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;145 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Hu J., Lv W., Lu W., Lv M. Optimized extraction of astaxanthin from shrimp shells treated by biological enzyme and its separation and purification using macroporous resin. Food Chem. 2021;363 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.H., Li K.L., Jiao H.C., Zhao J.P., Li H.F., Zhou Y.L., Cao A.Z., Wang J.M., Wang X.J., Lin H. Dietary bile acids supplementation decreases hepatic fat deposition with the involvement of altered gut microbiota and liver bile acids profile in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024;15:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40104-024-01071-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi L.S., Mu T.H., Sun H.N. Preparative purification of polyphenols from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves by AB-8 macroporous resins. Food Chem. 2015;172:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi X.Z., Guo S.S., Cao H., Cui X.W., Zhou J.D., Hu C.Q., Wang L., Duan T.Y., Huang L.Y., Li J. Optimization of macroporous resin purification of chenodeoxycholic acid and preliminary study on its lipid lowering function. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;34:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.J., Qiao Z.N., Huang G.S., Long M.F., Yang T.W., Zhang X., Shao M.L., Xu Z.H., Rao Z.M. Optimization of l-arginine purification from Corynebacterium crenatum fermentation broth. J. Sep. Sci. 2020;43:2936–2948. doi: 10.1002/jssc.202000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh Y.H., Hwang D.F. High-performance liquid chromatographic determiation for bile components in fish, chicken and duck. J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2021;751:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin B.X., Shi J.K., Kong L.H., Yang R.Q., Ai L.Z., Xiong Z.Q. Heterologous expression of four bile salt hydrolases in lactobacillus fermentum AR497. Food Mach. 2020;36:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Zeng H.N., Wan J.F., Cao X.J. Computational design of a molecularly imprinted polymer compatible with an aqueous environment for solid phase extraction of chenodeoxycholic acid. J. Chromatogr. A. 2019;1609 doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.Z., Yan Y. Application of adsorption resin separation technique in traditional China medicine research. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2004;29:628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.L., Zhang J., Chen J., Du G.C. Expression, purification and enzymatic properties study of the bile salt hydrolase from bifidobacterium in Escherichia coli. J. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;35:792–800. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.F., Wang L.L., Chen L.C., Liu T.B., Sha R.Y., Mao J.W. Enrichment and separation of steroidal saponins from the fibrous roots of Ophiopogon japonicus using macroporous adsorption resins. RSC. Adv. 2019;9:6689–6698. doi: 10.1039/c8ra09319a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Bo T.T., Chen X.Y., Wang X.X., Long M.D. Separation of succinic acid from aqueous solution by macroporous resin adsorption. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2016;61:856–864. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang C.C., Liu C.R., Shan C.B., Ma C.M. High-yield production of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside from flaxseed hull by extraction with alcoholic ammonium hydroxide and chromatography on microporous resin. Food Prod. Process and Nutr. 2021;3:35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.