Abstract

Background

Several approaches exist to produce local anaesthetic blockade of the brachial plexus. It is not clear which is the technique of choice for providing surgical anaesthesia of the lower arm, although infraclavicular blockade (ICB) has several purported advantages. We therefore performed a systematic review of ICB compared to the other brachial plexus blocks (BPBs). This review was originally published in 2010 and was updated in 2013.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of infraclavicular block (ICB) compared to other approaches to the brachial plexus in providing regional anaesthesia for surgery on the lower arm.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5); MEDLINE (1966 to June 2013) via OvidSP; and EMBASE (1980 to June 2013) via OvidSP. We also searched conference proceedings (from 2004 to 2012) and the www.clinicaltrials.gov trials registry. The searches for the original review were performed in September 2008.

Selection criteria

We included any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ICB with other BPBs as the sole anaesthetic technique for surgery on the lower arm.

Data collection and analysis

The primary outcome was adequate surgical anaesthesia within 30 minutes of block completion. Secondary outcomes included sensory block of individual nerves, tourniquet pain, onset time of sensory blockade, block performance time, block‐associated pain and complications related to the block.

Main results

In our original review we included 15 studies with 1020 participants and excluded two. In this updated review we included seven new studies and excluded six, bringing the total number of included studies to 22 and involving 1732 participants. The control group intervention was the axillary block in 14 studies, supraclavicular block in six studies, mid‐humeral block in two studies, and parascalene block in one study. One study compared ICB to both axillary and supraclavicular blocks. Nine studies employed ultrasound‐guided ICB. The risk of failed surgical anaesthesia 30 minutes after block completion was similar for ICB and all other BPBs (11.4% versus 12.9%, risk ratio (RR) 0.88, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.52, P = 0.64), but tourniquet pain was less likely with ICB (11.9% versus 18.0%; RR of experiencing tourniquet pain 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.92, P = 0.02). Subgroup analysis by method of nerve localization, and by control group intervention, did not show any statistically significant differences in the risk of failed surgical anaesthesia. However when compared to a single‐injection axillary block, ICB was better at providing complete sensory block of the musculocutaneous nerve (RR for failure 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.60, P < 0.0001). ICB had a slightly longer sensory block onset time (mean difference (MD) 1.9 min, 95% CI 0.2 to 3.6, P = 0.03) but was faster to perform than multiple‐injection axillary (MD ‐2.7 min, 95% CI ‐3.4 to ‐2.0, P < 0.00001) or mid‐humeral (MD ‐4.8 min, 95% CI ‐6.0 to ‐3.6, P < 0.00001) blocks.

Authors' conclusions

ICB is as safe and effective as any other BPBs, regardless of whether ultrasound or neurostimulation guidance is used. The advantages of ICB include a lower likelihood of tourniquet pain during surgery, more reliable blockade of the musculocutaneous nerve when compared to a single‐injection axillary block, and a significantly shorter block performance time compared to multi‐injection axillary and mid‐humeral blocks.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Humans; Brachial Plexus; Axilla; Clavicle; Forearm; Forearm/surgery; Musculocutaneous Nerve; Nerve Block; Nerve Block/adverse effects; Nerve Block/methods; Pain Measurement; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ultrasonography, Interventional; Ultrasonography, Interventional/methods

Plain language summary

A comparison of a local anaesthetic injection below the collarbone with other injection techniques for providing anaesthesia of the lower arm

Surgical anaesthesia of the lower arm, from the elbow to the hand, may be provided by injecting local anaesthetic around the brachial plexus (the bundle of nerves passing from the spinal cord in the neck to the arm, through the shoulder). There are several commonly‐used techniques of blocking the brachial plexus but it is not clear which, if any, is the best. This updated systematic review compared the effects of blocking the brachial plexus by injecting local anaesthetic in the area below the collarbone (the infraclavicular block) with other techniques.

We searched the databases until June 2013, and included 22 studies involving 1732 patients of whom 842 had an infraclavicular block and 930 had brachial plexus blockade with another technique. These other techniques were axillary block (injection in the armpit area; 14 studies), supraclavicular block (injection in the area just above the collarbone; six studies), mid‐humeral block (injection in the upper arm; two studies) and parascalene block (injection in the lower neck area; one study). One study compared an infraclavicular block with both an axillary block and a supraclavicular block. The infraclavicular block had a high success rate and was as good as all other blocks in providing anaesthesia of the lower arm. Advantages of the infraclavicular block included a reduced risk of pain from the tourniquet applied to the upper arm during surgery and a faster performance time (four minutes on average) compared to more complex techniques of axillary or mid‐humeral block that used three or four separate injections (instead of just one). Side‐effects were uncommon, and no difference was seen between the infraclavicular block and all other blocks in this regard.

In conclusion, this review showed that the infraclavicular block is an effective and safe choice for producing anaesthesia of the lower arm.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. infraclavicular block versus all other brachial plexus blocks for regional anaesthesia of the lower arm.

| infraclavicular block versus all other brachial plexus blocks for regional anaesthesia of the lower arm | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with regional anaesthesia of the lower arm Settings: Intervention: infraclavicular block versus all other brachial plexus blocks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | infraclavicular block versus all other brachial plexus blocks | |||||

| Adequate surgical anaesthesia ‐ At 30 minutes post‐block assessment interval | Study population | RR 0.88 (0.51 to 1.52) | 1051 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 871 per 1000 | 766 per 1000 (444 to 1000) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 868 per 1000 | 764 per 1000 (443 to 1000) | |||||

| Supplementation required to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.62 to 1.46) | 1412 (17 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 135 per 1000 | 128 per 1000 (84 to 197) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 120 per 1000 | 114 per 1000 (74 to 175) | |||||

| Tourniquet pain | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.47 to 0.92) | 615 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 180 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (85 to 166) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 157 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (74 to 144) | |||||

| Onset time of adequate surgical anaesthesia (minutes) | The mean onset time of adequate surgical anaesthesia (minutes) in the intervention groups was 1.93 higher (0.23 to 3.64 higher) | 726 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |||

| Block performance time (minutes) ‐ multiple‐injection axillary block | The mean block performance time (minutes) ‐ multiple‐injection axillary block in the intervention groups was 2.67 lower (3.36 to 1.98 lower) | 391 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |||

| Block performance time (minutes) ‐ mid‐humeral block | The mean block performance time (minutes) ‐ mid‐humeral block in the intervention groups was 4.8 lower (6.04 to 3.57 lower) | 224 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Subgroup analysis by method of localization showed that there was a significant difference in onset time in the studies using neurostimulation‐guided infraclavicular block but not in the studies using ultrasound‐guided infraclavicular block. 2 Only two studies in this review compared infraclavicular block to mid‐humeral block. Both were by the same investigators.

Background

Description of the condition

Surgical anaesthesia of the lower arm, from the elbow to the hand, may be readily achieved by injection of local anaesthetic around the brachial plexus (Cousins 1998). This regional anaesthesia technique avoids the need for a general anaesthetic and its accompanying risks (airway injuries, postoperative nausea and vomiting, postoperative drowsiness, etc). Control of postoperative pain is also excellent as the sensory block typically persists for several hours following injection.

The brachial plexus originates in the neck from the fifth to the eighth cervical nerve roots (C5 to C8) and the first thoracic nerve root (T1) then descends into the root of the neck and runs under the clavicle (collarbone) through the axilla (armpit) and down the arm. There are several techniques of brachial plexus blockade that can be used to provide anaesthesia for surgery of the lower arm. The brachial plexus may be approached with a needle at various sites along its course. These approaches include interscalene block (where the needle passes between the scalene muscles after piercing the skin in the front of the neck); supraclavicular block (where the skin is pierced lower and more laterally in the root of the neck above the clavicle); infraclavicular block (where the skin is pierced in the area below the clavicle); axillary block (where the skin is pierced in the axilla) and mid‐humeral block (where the skin is pierced in the upper arm). The choice of which technique to use depends upon the practitioner's preference, but also upon the perceived efficacy and safety of each technique.

Description of the intervention

The infraclavicular block targets the brachial plexus in the infraclavicular space, which is pyramidal shaped and contains the brachial plexus, subclavian‐axillary artery and vein, and lymph nodes and loose fatty tissue. The apex is a triangular surface formed by the confluence of the clavicle, scapula and first rib; the base is the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the armpit. Together with their investing fasciae, the posterior wall is formed by the scapula and its associated muscles; and the anterior wall by the pectoralis major and minor. The humerus, and the converging muscles and tendons of the anterior and posterior walls that insert into it, constitute the lateral wall. The bony thoracic cage with its overlying layer of serratus anterior muscle and fascia forms the medial wall. At the level of the infraclavicular space the brachial plexus is organized as three cords (lateral, medial and posterior) surrounding the axillary artery. None of the major terminal branches arise at this level.

The first description of a neurostimulation‐guided infraclavicular block was by Raj and colleagues (Raj 1973) in 1973. Whiffler (Whiffler 1981) followed in 1981 with his description of the technique using the coracoid process as the chief surface landmark, but it was not until Kilka and colleagues (Kilka 1995) described their vertical infraclavicular plexus block in 1995 that interest in the infraclavicular approach really blossomed. Since then several other variants of the neurostimulation‐guided infraclavicular block, using slightly different surface landmarks, have been described and adopted into clinical practice (Borgeat 2001; Jandard 2002; Kapral 1996; Kapral 1999; Minville 2004; Salazar 1999; Wilson 1998). Most recently, ultrasound‐guided techniques of infraclavicular block (Dingemans 2007; Sandhu 2006) in which the axillary artery and surrounding brachial plexus are directly visualized using ultrasound have become popular. By allowing direct visualization of the needle tip, target nerves and the spread of local anaesthetic as it is injected ultrasound can increase the efficacy of the block (McCartney 2010).

How the intervention might work

The purported advantages of infraclavicular block are as follows. First, it provides comprehensive anaesthesia of the upper limb as it blocks the brachial plexus where the three cords run close together in a neurovascular bundle with the axillary artery. The axillary block often fails to block the axillary nerve and musculocutaneous nerves (which have usually branched off at this level) whilst the interscalene and supraclavicular approaches may often fail to provide anaesthesia in the distribution of the ulnar nerve (Cousins 1998). There also appears to be a lower incidence of tourniquet pain with the infraclavicular block, which is attributed to spread to the intercostobrachial nerve that runs close to the brachial plexus in the infraclavicular space (Desroches 2003; Sandhu 2006). Secondly, the risk of inadvertent lung or pleural puncture is lower than with the interscalene and supraclavicular approaches (Cousins 1998) as the lung does not lie in the path of the needle. Thirdly, by piercing the skin below the clavicle, injury to the other neurovascular structures in the neck are avoided (unlike with the interscalene or supraclavicular approaches). Fourthly, infraclavicular block does not require abduction of the arm at the shoulder and can be performed in any arm position. Finally, it is an ideal site for inserting a catheter for continuous infusion of local anaesthetic. The bulk of the pectoralis muscle firmly anchors the catheter, arm movement is not impaired and hygiene is easily maintained (Brown 1993).

Why it is important to do this review

There are several techniques of brachial plexus blockade that can be used to provide anaesthesia for surgery of the lower arm. Given the advantages listed above, the infraclavicular block may be the technique of choice. We sought to establish if this was indeed the case by performing a systematic review of the efficacy and safety of infraclavicular block as compared to other approaches to block the brachial plexus for regional anaesthesia. Our original review (Chin 2010) found that the infraclavicular block was as effective as all other techniques of brachial plexus blockade with the advantages of being faster to perform, and less tourniquet pain. At the time, there were insufficient data to conclude if these findings applied to ultrasound‐guided approaches as well. Since then, there has been a large amount of research conducted into ultrasound‐guided peripheral nerve blocks.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of infraclavicular block compared to other approaches to the brachial plexus in providing regional anaesthesia for surgery on the lower arm.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), regardless of blinding, that compared infraclavicular block with another technique of brachial plexus blockade. We excluded any study that was not randomized or that did not have infraclavicular block as one of its treatment arms.

Types of participants

We included all patients, both adults and children, undergoing surgery of the lower arm (hand, forearm or elbow) under regional anaesthesia; including those where a planned combined regional and general anaesthetic was used.

Types of interventions

The included studies had to have at least one treatment arm in which the infraclavicular approach to the brachial plexus was used. The other treatment arm(s) had to consist of an alternative technique to anaesthetize the plexus, including interscalene, supraclavicular, axillary, or mid‐humeral approaches. We included any variation of these techniques, including:

single shot or continuous catheter techniques;

single or multiple nerve stimulation techniques;

localization of the brachial plexus by means of surface landmarks, elicitation of paraesthesiae, neurostimulation, or ultrasound guidance;

any local anaesthetic agent.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Adequate surgical anaesthesia from the block alone within 30 minutes of block completion. This was defined as commencement of surgery at or before 30 minutes after the block was performed, and without the patient receiving supplemental local anaesthetic injection, systemic analgesia, or general anaesthesia.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures (efficacy)

2. The need for supplemental local anaesthetic blocks or systemic analgesia, or both, to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia.

3. The need for general anaesthesia to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia.

4. Complete sensory block in individual nerve territories within 30 minutes after completion of block performance. We considered all seven terminal nerves of the brachial plexus: the axillary nerve (AxN), medial brachial cutaneous nerve (MBCN), medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (MABCN), musculocutaneous nerve (MCN), median nerve (MN), ulnar nerve (UN), and radial nerve (RN). The method of sensory block testing was not pre‐specified.

5. Tourniquet pain. We did not specify a priori a strict definition or method of assessment of this outcome.

6. Onset time of sensory block. This was defined as the time in minutes from completion of the block to the absence or decrease of any sensation in the operative area.

7. Duration of postoperative analgesia. This was defined as the time in minutes from block completion to the patient's first request for additional analgesia.

8. Block performance time in minutes. We did not specify a priori a strict definition or method of assessment of this outcome.

Secondary outcome measures (safety and comfort)

9. Pain associated with block performance. We extracted data on the intensity of block‐associated pain using a visual analogue score (VAS) from 0 to 10.

10. Complications of the block procedure. We looked at five complications: pneumothorax; vascular puncture; Horner's syndrome; neurological deficits, including residual neuropraxias unrelated to the surgical site, lasting more than 24 hours; systemic complications related to administration of local anaesthetic, including cardiorespiratory arrest, symptoms of local anaesthetic toxicity, or any other events reported by study investigators. We extracted the number of patients who were reported to have these complications. We did not specify a priori a strict definition or method of assessment for these events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In the first version of this review (Chin 2010), we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL using the strategies detailed in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3, respectively, up until September 2008. For this update, we received search downloads from Karen Hovhannisyan (KH) as Trial Search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG) for the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 5); MEDLINE (1966 to week 5 May 2013) via OvidSP; and EMBASE (1980 to 2013 Week 22) via OvidSP.

Searching other resources

We searched the following conference proceedings (2004 to 2012):

American Society of Anesthesiologists' Annual Meeting;

American Society of Regional Anesthesia Annual Meeting;

International Anesthesia Research Society Annual Meeting;

Canadian Anesthesiologists' Society Annual Meeting;

European Society of Regional Anaesthesia Annual Meeting.

We also checked the reference lists of the included studies and the clinical trials registry at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Our last search took place on 7 June 2013. We contacted the corresponding authors of identified trials for more information, especially regarding unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In the first version of this review (Chin 2010), two authors (Ki Jinn Chin (KJC) and Veerabadran Velayutham (VV)) independently reviewed the abstracts of all references identified by the searches, obtained full‐text copies of potentially relevant trials, and assessed them according to the parameters outlined in 'Criteria for considering studies for this review'. Only trials meeting these criteria were included in the review. All disagreements were resolved by discussion and mutual consensus.

For this update, three of the current review authors (KJC, Husni Alakkad (HA) and Sanjib Das Adhikary (SDA)) independently selected potentially eligible studies from the search downloads provided by the CARG Trial Search Co‐ordinator (KH). We obtained full‐text copies of these studies and independently reviewed them to ensure they met the criteria for inclusion. Consensus on study inclusion and exclusion was reached by discussion amongst the three authors (KJC, HA and SDA).

Data extraction and management

In the first version of this review (Chin 2010), data were independently extracted from included studies by two authors (KJC and Mandeep Singh (MS)) using a piloted data extraction form modified from one developed by the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion and mutual consensus. Wherever possible we contacted primary investigators for further details of their trials and missing data. We entered all data independently into the Cochrane Review Manager software, version 5.2 (RevMan 5.2) and checked for differences in the data using the double entry facility in the software.

In this update, two authors (KJC, SDA, or HA) again independently extracted information and data from each study using the data extraction form as described above. Extracted data were independently entered by at least two authors into an Excel spreadsheet and checked for differences before being entered into the Cochrane Review Manager software, version 5.2 (RevMan 5.2).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the first version of this review (Chin 2010), we assessed trial quality using criteria developed by the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group, which included assessments of allocation bias, observer bias, and attrition bias.

In this update, two authors assessed risk of bias for previously and newly‐included trials using the tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2011). The seven criteria used are listed below. For each criterion, 'Low' indicates a low risk of bias, 'High' represents a high risk of bias, and 'Unclear' indicates that there was insufficient information to make a judgement of the degree of risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

1. Random sequence generation

2. Allocation concealment

3. Blinding of participants and personnel

4. Blinding of outcome assessment (subdivided into main and other outcomes)

5. Incomplete outcome data

6. Selective outcome reporting

7. Other potential biases

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes, and mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for continuous outcomes. Where the outcome was a positive or desirable one (for example adequate surgical anaesthesia), the risk ratio of the non‐event was reported.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the original study investigators whenever there were missing data. If no further information could be obtained from the study investigators, the data were assumed to be missing at random and only available data were analysed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic and gave consideration to the appropriateness of pooling and meta‐analysis. We explored causes of heterogeneity, especially where there was evidence of significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 more than 40%), and performed subgroup analyses where appropriate. Where significant heterogeneity could not be explained we employed a random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986); in all other cases we applied a fixed‐effect model. In cases where it was not possible or appropriate to combine studies we provided a narrative synthesis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not formally assess reporting bias using a funnel plot. We attempted to limit reporting bias by considering all studies irrespective of language and by searching for unpublished data in conference proceedings and clinical trials registries.

Data synthesis

We summarized the results using meta‐analyses performed in the Cochrane Review Manager software, version 5.2 (RevMan 5.2). We expressed the treatment effect as a risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous data, and as a mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous data. We performed a sensitivity analysis on outcomes likely to be affected by study differences in the patient population, interventions or methodological quality.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there was evidence of significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 40%), or where there was good reason to expect clinical heterogeneity, we considered subgroup analyses based on:

the approach to the brachial plexus used in the control group (parascalene, supraclavicular, axillary, mid‐humeral);

the method used to locate the brachial plexus (paraesthesiae, electrostimulation, ultrasound);

the number of separate nerve stimulations elicited, i.e. whether a single‐ or multiple‐injection technique was used;

whether a single‐shot or continuous catheter technique was used;

the technique used for the infraclavicular approach;

the volume of local anaesthetic used;

the type of local anaesthetic used;

the age of the patient (children versus adults);

the type of surgery performed (vascular, orthopaedic, etc).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis if the methodological quality or baseline characteristics of the patients in the studies differed significantly, or if there were a significant number of withdrawals or dropouts in the included studies.

Results

Description of studies

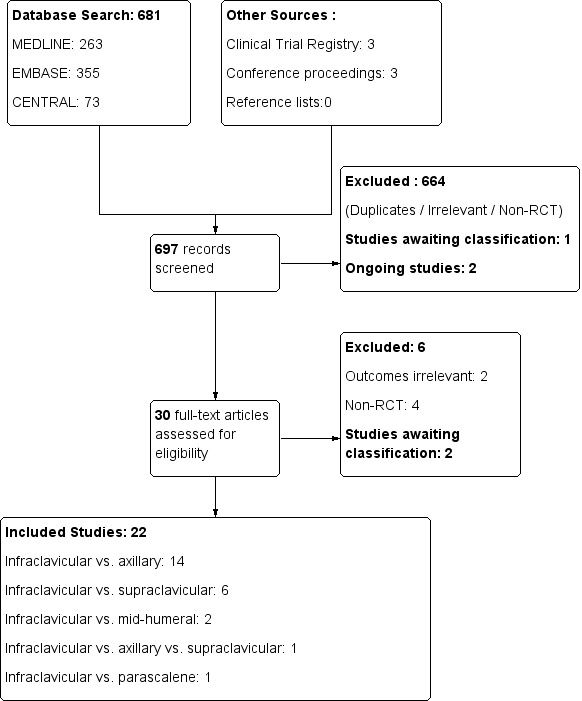

See Figure 1

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

In the first version of this review (Chin 2010), screening of the results of the electronic search identified 17 potentially relevant studies that compared infraclavicular block and other approaches to the brachial plexus. We identified a further two studies that were ongoing (Danelli 2008; Russo 2008) and were therefore not included. We excluded two studies (Neuburger 1998; Rodriguez 2003) because they were not randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The final analysis included 15 RCTs with a total patient enrolment of 1020 participants.

In this update, three authors (KJC, HA and SDA) independently screened the search results from three databases: CENTRAL (36 references), EMBASE (175 references), and MEDLINE (85 references). We identified 15 potentially relevant studies for which we reviewed the full‐text reports (Figure 1).

We excluded two studies that had already been included in the first version of the review (De Jose Maria 2008; Tran 2008), and another two studies that were not RCTs (Fredrickson 2011; Mariano 2008) (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Two studies (Astore 2012; Lopez Morales 2011) were available only as conference abstracts and both contained insufficient information to determine the validity of the data. We were unsuccessful in contacting the study investigators for clarification. Both of these studies were not included for analysis in this review and were placed in the Studies awaiting classification table.

Of the remaining nine studies, we excluded two (Mariano 2011a; Mariano 2011b) as they were not designed to examine this review's primary outcome of surgical anaesthesia. In addition, the study reported in Mariano 2011a had been prematurely terminated and thus the validity of the data could not be determined.

Of the two studies identified as ongoing in the first version of the review, one (Russo 2008) had been published and was included in this update (as Tran 2009). The other (Danelli 2008) was listed as completed in the clinical trials registry at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov but we were unable to locate any data for the study; we have placed it in the Studies awaiting classification table. We identified two more ongoing studies (Boivin 2013; Hillel Yaffe 2013) from the clinical trials registry (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Included studies

We included a total of 22 studies in this updated review, seven of which were new, with a total patient enrolment of 1732 participants. Details of individual studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

The geographical distribution of the studies was as follows: four studies from Denmark (Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009); three studies each from France (Deleuze 2003; Minville 2005; Minville 2006) and Canada (Arcand 2005; Tran 2008; Tran 2009); two studies each from Austria (Fleischmann 2003; Kapral 1999) and Korea (Song 2011; Yang 2010); one study each from Spain (De Jose Maria 2008), Germany (Heid 2005), Finland (Niemi 2007), Italy (Caruselli 2005), the Netherlands (Rettig 2005), New Zealand (Fredrickson 2009), Turkey (Ertug 2005) and the United States (Tedore 2009).

Eighteen of the studies were in adults, and three studies were in children (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Fleischmann 2003). There were four studies in patients undergoing emergency surgery for trauma of the arm (Caruselli 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Kapral 1999; Minville 2006) and one study in uraemic patients undergoing arterio‐venous fistula creation (Niemi 2007). The rest of the studies were in patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery of the distal upper limb.

Control group intervention

All 22 studies met the inclusion criterion of comparing infraclavicular block in one treatment group to any alternative approach to the brachial plexus in the other group. This second treatment group consisted of axillary block in 13 studies (Deleuze 2003; Ertug 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Heid 2005; Kapral 1999; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Niemi 2007; Rettig 2005; Song 2011; Tedore 2009; Tran 2008); mid‐humeral block in two studies (Minville 2005; Minville 2006); supraclavicular block in five studies (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Yang 2010); and parascalene block in one study (Caruselli 2005). One study (Tran 2009) compared three treatment groups: infraclavicular block, supraclavicular block, and axillary block.

Method of nerve localization

Nine studies utilized ultrasound guidance (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Song 2011; Tedore 2009; Tran 2008; Tran 2009) to locate the brachial plexus for infraclavicular blockade. Four of these studies (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2009) compared it to an ultrasound‐guided supraclavicular block, two compared it to an ultrasound‐guided axillary block (Frederiksen 2010; Song 2011), one compared it to a multiple‐injection neurostimulation‐guided axillary block (Tran 2008), and one compared it to a transarterial double‐injection axillary block (Tedore 2009). Tran et al compared ultrasound‐guided infraclavicular block with ultrasound‐guided supraclavicular and axillary blocks (Tran 2009).

All other studies used a combination of surface landmarks and neurostimulation to locate the brachial plexus.

Local anaesthetic type and volume

A long‐acting local anaesthetic was used in nine studies (bupivacaine (Ertug 2005); ropivacaine (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Deleuze 2003; Fleischmann 2003; Heid 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Rettig 2005; Yang 2010)), a short‐acting local anaesthetic in nine studies (lidocaine (Fredrickson 2009; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Song 2011; Tran 2009); mepivacaine (Frederiksen 2010; Kapral 1999; Niemi 2007; Tedore 2009)), and a mixture of short‐ and long‐acting anaesthetics in four studies (1 to 1 ropivacaine and mepivacaine mixture (Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009); 1 to 1 bupivacaine and lidocaine mixture (Tran 2008); 1 to 3 bupivacaine and lidocaine mixture (Arcand 2005)).

Four of the adult studies utilized a weight‐based formula in calculating the local anaesthetic volume (Arcand 2005: 0.5 ml/kg up to 40ml; Koscielniak‐N 2000: range of 20 to 40 ml; Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009: 0.5 ml/kg and range of 30 to 50 ml; Niemi 2007: 35 to 50 ml; Tedore 2009: 40 to 50 ml for weight of 50 kg or less, and 50 to 60 ml for weight of more than 50 kg). The more recent studies using ultrasound‐guided techniques tended to use lower fixed volumes (Song 2011: 20 ml; Fredrickson 2009: 30 ml; Tran 2009: 35 ml). The rest of the adult studies used a fixed volume of at least 40 ml.

Complications and side‐effects

None of the studies specified whether the presence of tourniquet pain was self reported or elicited by direct questioning.

The methods of assessment of complications of the block varied slightly between studies. Pneumothorax was excluded by the absence of clinical symptoms in 13 studies (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Deleuze 2003; Ertug 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Song 2011; Yang 2010) and by chest x‐ray in one study (Kapral 1999). Vascular puncture was explicitly mentioned as an outcome in 17 studies (De Jose Maria 2008; Deleuze 2003; Ertug 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Heid 2005; Kapral 1999; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Tran 2008; Tran 2009; Yang 2010). Horner's syndrome was explicitly mentioned in 10 studies (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Deleuze 2003; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Tran 2008; Tran 2009; Yang 2010). Persistent neurological deficit was assessed in 14 studies at varying post‐block intervals: four studies (Deleuze 2003; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Tedore 2009; Yang 2010) at 24 to 48 hours; four studies (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Frederiksen 2010; Tran 2009) at one week; three studies (Ertug 2005; Fredrickson 2009; Tedore 2009) at 10 to 14 days; and four studies (Koscielniak‐N 2000; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005) at two to four weeks. Systemic local anaesthetic toxicity was explicitly mentioned as an outcome in 10 studies (Deleuze 2003; Ertug 2005; Heid 2005; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Niemi 2007; Rettig 2005; Tran 2008).

Excluded studies

Six studies were excluded for the reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Two of these had previously been identified in the first version of this review. Four new studies were identified and excluded for the following reasons: two of them were not RCTs (Fredrickson 2011; Mariano 2008), and two of them were not designed to examine the outcomes of interest in this review (Mariano 2011a; Mariano 2011b).

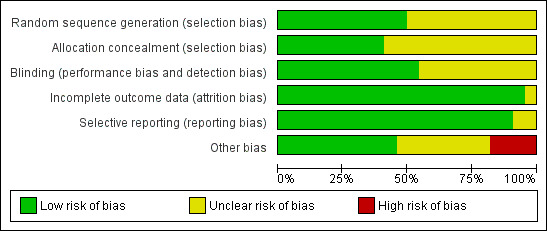

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias judgements for each of the included studies are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and described in the risk of bias tables in Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The risk of selection bias was judged to be unclear in the majority (10) of the studies as little or no details were provided on the method of random sequence generation or allocation concealment. The risk of selection bias was deemed low in eight studies (Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Niemi 2007; Tedore 2009; Tran 2009) which explicitly described adequate random sequence generation and allocation concelament. Three studies (Fredrickson 2009; Heid 2005; Song 2011) described adequate random sequence generation but were unclear on allocation concealment. Caruselli 2005 described adequate allocation concealment but did not provide details on the method of random sequence generation.

Blinding

Blinding of the outcome assessor was explicitly mentioned in 12 studies (Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Heid 2005; Kapral 1999; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Niemi 2007; Rettig 2005; Tran 2009; Yang 2010); it was unclear if this occurred in the other studies. Blinding of the patient was not explicitly mentioned in any of the studies.

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies had dropouts due to technical difficulties with block performance. They did not report outcomes for these patients (Arcand 2005: three patients; Koscielniak‐N 2000: one patient; Niemi 2007: one patient). In the study of De Jose Maria 2008 the block procedure was abandoned in two patients following arterial puncture; outcomes were not available for these patients. Two studies had incomplete reporting of some outcomes (Fleischmann 2003: nine patients; Niemi 2007: three patients). As there were only a relatively small number of missing outcomes we did not attempt to impute optimistic and pessimistic missing outcomes for a sensitivity analysis.

Selective reporting

All pre‐specified and relevant outcomes were reported in the majority of studies. Three studies that did not report results for certain relevant outcomes were judged to be at unclear risk of reporting bias as there was insufficient information to determine if this omission was made a priori or post hoc.

Other potential sources of bias

There were several methodological differences between the studies that may have affected the assessment of block efficacy. Three studies allowed for only a 15‐minute or shorter interval between completion of the block and the assessment of block efficacy (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Tedore 2009); four studies allowed a 50 to 60‐minute interval (Heid 2005; Niemi 2007; Rettig 2005; Yang 2010); and the rest of the studies allowed an interval of 30 minutes. Five studies used a weight‐based formula in calculating local anaesthetic volume (Arcand 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Niemi 2007), which would have led to the use of volumes < 40 ml in some patients. Four studies did not supplement inadequate blocks with additional local anaesthetic injections or systemic analgesics (Ertug 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Rettig 2005; Tran 2009) but instead went straight to general anaesthesia as the method of rescue. These differences were of minor concern and the studies were judged to be at low or unclear risk of bias.

We judged four studies to be at high risk of other bias. In De Jose Maria 2008, an unusual technique of ultrasound‐guided intraclavicular block was used which may have contributed to the incidence of arterial puncture and subsequent abandonment of the block in two patients; these patients were classified as block failures. In the other three studies (Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Yang 2010) the investigators stated that they had greater experience with the infraclavicular block than the comparator technique; this may have influenced the observed success rates of surgical anaesthesia.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcome

1. Adequate surgical anaesthesia from the block alone, within 30 minutes of block completion

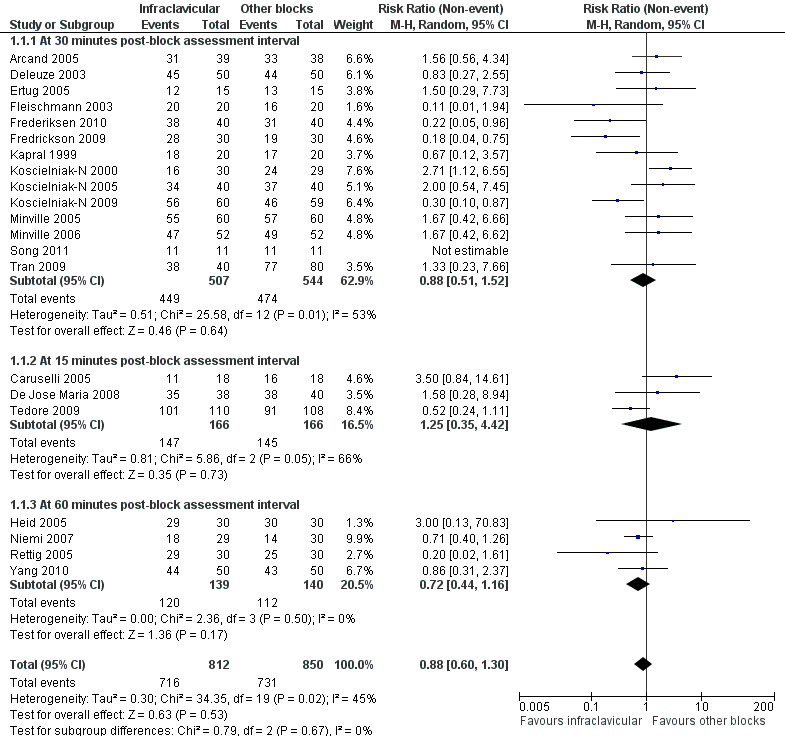

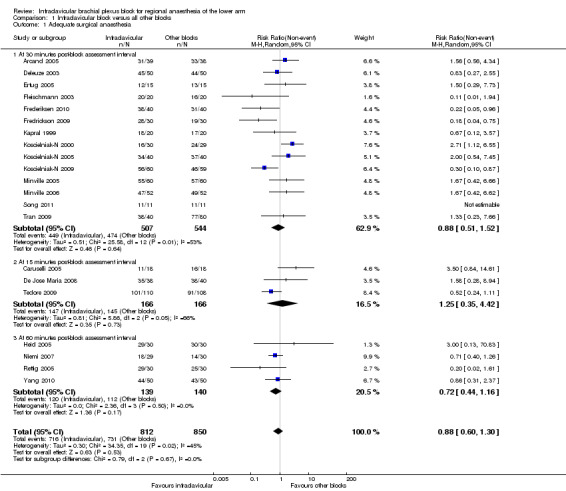

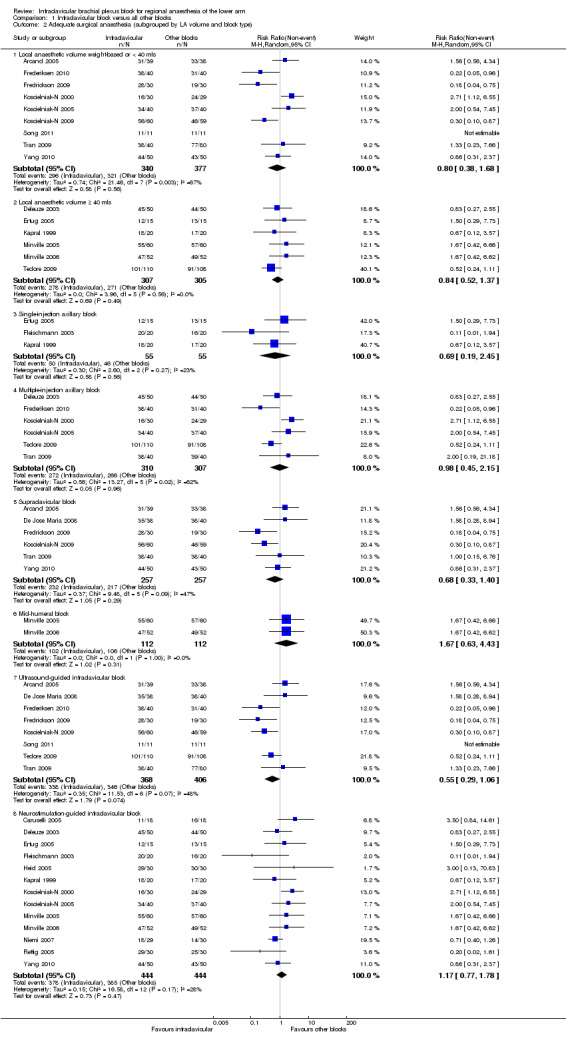

Twenty‐one studies (all except Tran 2008) evaluated the outcome of surgical anaesthesia. Fourteen studies, involving a total of 1051 participants, did so at an interval of 30 minutes after block completion. The remaining seven studies (involving 564 participants) assessed surgical anaesthesia at intervals of 15 minutes (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Tedore 2009) or 50 to 60 minutes (Heid 2005; Niemi 2007; Rettig 2005; Yang 2010) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, outcome: 1.1 Adequate surgical anaesthesia, subgrouped by time of block assessment.

Pooled analysis of the 14 studies evaluated at 30 minutes, using the random‐effects model because of significant heterogeneity (P = 0.01, I2 = 53%), showed no significant difference in the proportion of each group with surgical anaesthesia (88.6% of patients achieved surgical anaesthesia following infraclavicular block (ICB) compared to 87.1% with all other blocks; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.88, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.52, P = 0.64, I2 = 53%) (Analysis 1.1.1). Recognising that the seven other studies could contribute to our understanding of the incidence of adequate surgical anaesthesia, we performed an overall analysis including all trials (Analysis 1.1). The overall pooled results also showed that there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients achieving adequate surgical anaesthesia (88.2% with ICB versus 86.0% with all other blocks; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.88, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.30, P = 0.53, I2 = 45%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 1 Adequate surgical anaesthesia.

Subgroup analysis by volume of local anaesthetic showed that there was no significant difference between ICB and other blocks in providing adequate surgical anaesthesia regardless of whether a fixed volume ≥ 40 ml was injected (90.5% versus 88.9%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.84, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.37, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.2.1) or whether volume was weight‐based or fixed at < 40 ml (87.1% versus 85.1%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.80, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.68, I2 = 67%) (Analysis 1.2.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 2 Adequate surgical anaesthesia (subgrouped by LA volume and block type).

Subgroup analysis by control group intervention did not indicate any significant differences when comparing ICB to either: a) single‐injection axillary block (91.0% versus 83.6%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.69, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.45, P = 0.56. I2 = 23%) (Analysis 1.2.3); b) multiple‐injection axillary block (87.7% versus 86.6%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.98, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.15, P = 0.96, I2 = 62%) (Analysis 1.2.4); c) supraclavicular block (90.3% versus 84.4%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.68, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.40, P = 0.29, I2 = 47%, I2 = 47%) (Analysis 1.2.5); or d) a mid‐humeral block (91.1% versus 94.6%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 1.67, 95% CI 0.63 to 4.43, P = 0.31, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.2.6).

Eight studies (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Tedore 2009; Tran 2009) utilized an ultrasound‐guided ICB technique, and pooled analysis of this subgroup did not show a statistically significant difference between ICB and the control group intervention (91.8% versus 85.2%; RR of no surgical anaesthesia with ICB 0.55, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.06, I2 = 48%).

Secondary outcomes

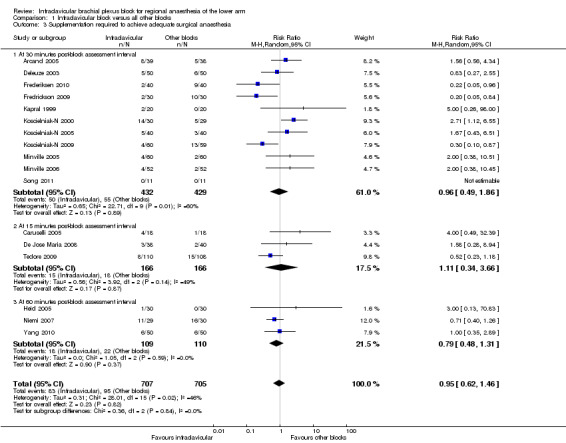

2. The need for supplemental local anaesthesia, systemic analgesia, or both, to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia

Seventeen out of the 21 studies that evaluated the outcome of surgical anaesthesia dealt with inadequate surgical anaesthesia by supplementing with either local anaesthesia injections, systemic analgesia, or both. Four studies (Ertug 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Rettig 2005; Tran 2009) resorted to general anaesthesia in the first instance and were excluded from this analysis. Overall pooled analysis showed there was no significant difference between ICB and other blocks in the likelihood of requiring supplementation (11.7% versus 13.5%; RR of requiring supplementation 0.95, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.46, P = 0.82, I2 = 46%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 3 Supplementation required to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia.

Subgroup analysis by time of block assessment also found that there was no difference in the likelihood of supplementation regardless of whether this was done 30 minutes (Analysis 1.3.1), 15 minutes (Analysis 1.3.2), or 60 minutes (Analysis 1.3.3) after block performance.

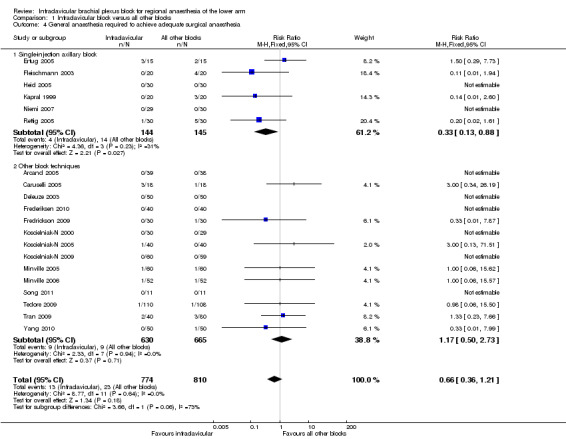

3. The need for general anaesthesia for completion of surgery, to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia

The need for general anaesthesia for completion of surgery, to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia, was reported in 20 studies. This was all except De Jose Maria 2008 and Tran 2008, in which all patients received a planned general anaesthetic. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients requiring general anaesthesia with an ICB compared to other blocks (1.7% versus 3.2%; RR of requiring general anaesthesia with ICB 0.66, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.21, P = 0.18, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 4 General anaesthesia required to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia.

When compared to a single‐injection axillary block, however, the need for general anaesthesia was significantly less likely with an ICB (2.8% versus 9.7%; RR of requiring general anaesthesia with ICB 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.88, P = 0.03, I2 = 31%) (Analysis 1.4.1).

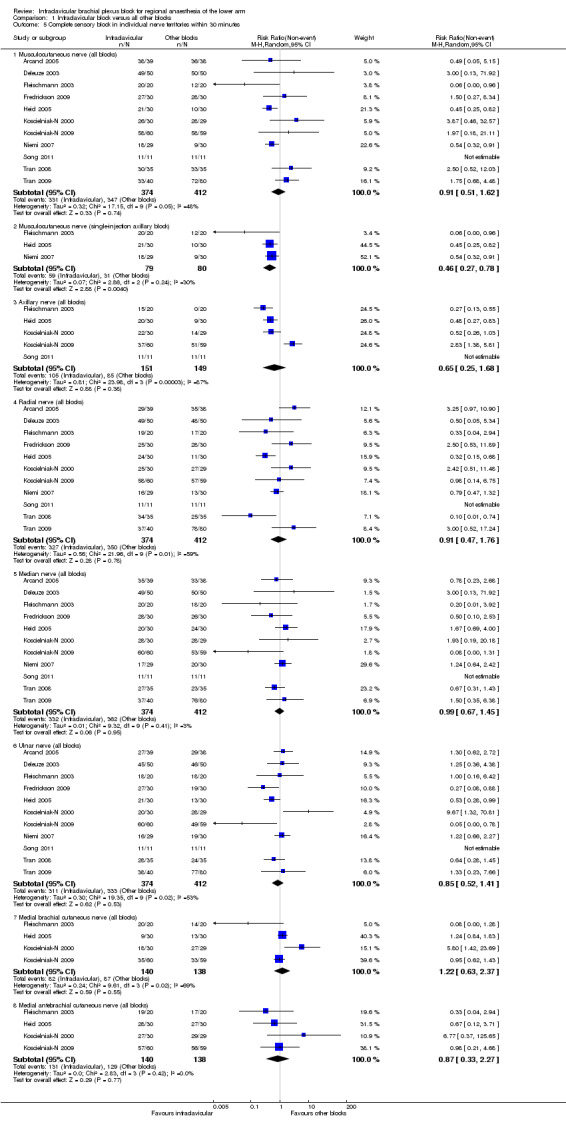

4. Complete sensory block in individual nerve territories within 30 minutes of completion of block performance

Eleven studies reported the incidence of complete sensory block at 30 minutes after block completion in the four major terminal nerve distributions of the brachial plexus (musculocutaneous nerve, median nerve, radial nerve, ulnar nerve) (Arcand 2005; Deleuze 2003; Fleischmann 2003; Fredrickson 2009; Heid 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Niemi 2007; Song 2011; Tran 2008; Tran 2009). Four of these studies also reported the incidence of sensory block in three other nerve distributions supplied by the brachial plexus: the axillary nerve, medial brachial cutaneous nerve, and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (Fleischmann 2003; Heid 2005; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2009).

Pooled analysis of all studies showed that complete sensory block of the musculocutaneous nerve (MCN) was equally likely following ICB or all other blocks (88.5% versus 84.2%; RR of failure with ICB to obtain complete sensory block of MCN at 30 minutes 0.91, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.62, P = 0.74, I2 = 48%). When ICB was compared to only single‐injection axillary blocks, however, ICB was much more likely to produce sensory block of the MCN (74.7% versus 38.8; RR of failure with ICB to obtain complete sensory block of the MCN at 30 minutes 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.78, P = 0.004, I2 = 30%) (Analysis 1.5.2).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 5 Complete sensory block in individual nerve territories within 30 minutes.

There were no significant differences between ICB and other blocks in the incidence of complete sensory block of the other terminal nerves (Analysis 1.5.3 to 1.5.8).

5. Tourniquet pain

Pain or discomfort related to the application of a surgical tourniquet on the upper arm was reported as an outcome in eight studies (Deleuze 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Minville 2005; Minville 2006). Tourniquet pain was significantly less likely with an ICB than with other blocks (11.9% versus 18.0%; RR of experiencing tourniquet pain with ICB 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.92, P = 0.02, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 6 Tourniquet pain.

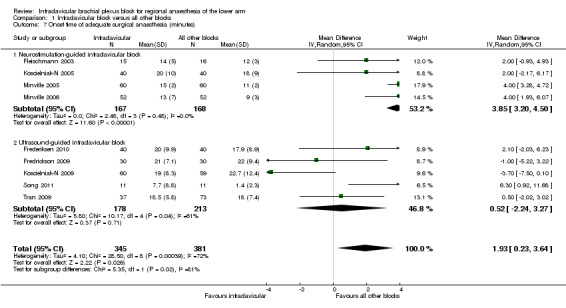

6. Onset time of adequate surgical anaesthesia

Nine studies reported block onset time, however this was not precisely defined in two studies (Koscielniak‐N 2005; Minville 2006). In five studies (Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Minville 2005; Song 2011) onset time was defined as the time from block completion to the onset of analgesia (and not anaesthesia). Pooled analysis of all nine studies showed that block onset time was slightly longer following ICB. The mean difference (MD) of 1.9 min was statistically but not clinically significant (95% CI 0.2 to 3.6 min, P < 0.03, I2 = 72%) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 7 Onset time of adequate surgical anaesthesia (minutes).

Four out of the nine studies (Fleischmann 2003; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Minville 2005; Minville 2006) compared neurostimulation‐guided ICB to another neurostimulation‐guided technique. In this subgroup, the difference in block onset time was more marked (MD 3.9 min, 95% CI 3.2 to 4.5 min, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.7.1). It should be noted that three out of these four studies were comparing ICB to multiple‐injection axillary (Koscielniak‐N 2005) or mid‐humeral (Minville 2005; Minville 2006) blocks. When only ultrasound‐guided ICB was considered, however, there was no difference in the onset time between groups (MD 0.5 min, 95% CI ‐2.2 to 3.3 min, P = 0.71, I2 = 61%) (Analysis 1.7.2).

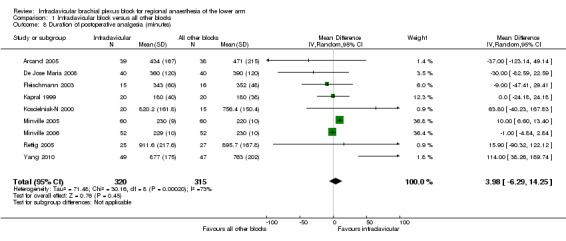

7. Duration of postoperative analgesia

Nine studies assessed the duration of postoperative analgesia, defined as the time from block completion to the first request for or use of additional analgesics (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Fleischmann 2003; Kapral 1999; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Yang 2010) (Analysis 1.8). The difference in duration between ICB and all other brachial plexus blocks was neither clinically nor statistically significant (MD 4.0 min, 95% CI ‐6.3 to 14.3 min, P = 0.45, I2 = 73%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 8 Duration of postoperative analgesia (minutes).

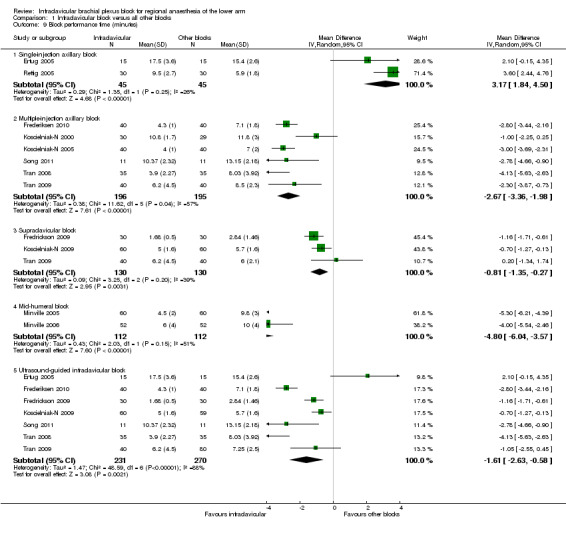

8. Block performance time

Twelve studies measured block performance time (Arcand 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Ertug 2005; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Song 2011; Tran 2009). We did not report a pooled meta‐analysis of all studies because of the significant statistical and clinical heterogeneity amongst the comparator block techniques. Instead, we performed pooled meta‐analysis of subgroups in which the comparator techniques used were clinically similar. It took 3.2 minutes longer on average to perform an ICB compared to a single‐injection axillary block (95% CI for MD 1.8 to 4.5 min, P < 0.00001, I2 = 26%) (Analysis 1.9.1). However, ICB was faster to perform compared to a multiple‐injection axillary block (MD ‐2.7 min, 95% CI ‐3.4 to ‐2.0 min, P = 0.04, I2 = 57%) (Analysis 1.9.2) and a multiple‐injection mid‐humeral block (5.3 versus 9.9 min; MD ‐4.8 min, 95% CI ‐6.0 to ‐3.6 min, P < 0.00001, I2 = 51%) (Analysis 1.9.4). ICB was also faster to perform than a supraclavicular block (MD ‐0.8 min, 95% CI ‐1.4 to ‐0.3 min, P = 0.003, I2 = 39%) (Analysis 1.9.3) but this difference was not clinically significant. Finally, a subgroup analysis of the six studies using an ultrasound‐guided ICB technique showed that this was slightly faster (MD ‐1.6 min, 95% CI ‐2.6 to ‐0.6 min, P = 0.002, I2 = 88%) (Analysis 1.9.5) than the control group intervention (which comprised supraclavicular (Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Tran 2009) and axillary (Frederiksen 2010; Song 2011; Tran 2008; Tran 2009) blocks).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 9 Block performance time (minutes).

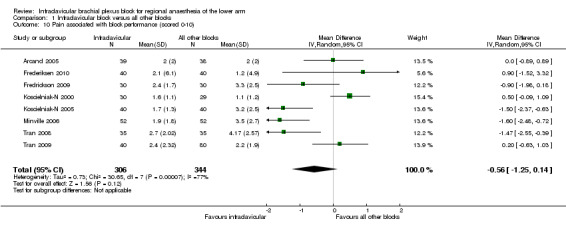

9. Pain associated with block performance

Nine studies measured block‐associated pain scores (Arcand 2005; Fleischmann 2003; Frederiksen 2010; Fredrickson 2009; Koscielniak‐N 2000; Koscielniak‐N 2005; Minville 2006; Tran 2008; Tran 2009). We were unable to obtain numerical data for Fleischmann 2003 and hence this study was not included in the analysis. The block‐associated pain score (as measured on an 11‐point VAS of 0 to 10) was lower in the ICB group but this difference was not statistically or clinically significant (MD ‐0.6, 95% CI ‐1.3 to 0.1, P = 0.12, I2 = 77%) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 10 Pain associated with block performance (scored 0‐10).

Two of these studies evaluated block‐associated pain in the setting of surgery for trauma to the arm, using different measures. Minville et al (Minville 2006) evaluated the intensity of pain on a 0 to 10 scale and reported a MD of ‐1.60 (95% CI ‐2.48 to ‐0.72, P = 0.0004) in patients receiving an ICB compared to a mid‐humeral block. Kapral et al (Kapral 1999) reported the occurrence of pain (not further defined) in 5 (25%) versus 16 (80%) patients receiving ICB and axillary blocks, respectively (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.69, P < 0.01).

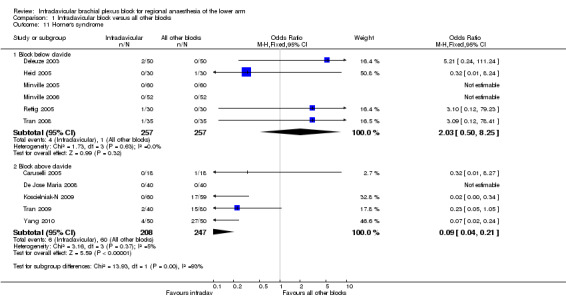

10. Complications of the block procedure

Eleven studies looked at the incidence of Horner's syndrome (Analysis 1.11). In six of these studies (Deleuze 2003; Heid 2005; Minville 2005; Minville 2006; Rettig 2005; Tran 2008) ICB was compared to blocks below the clavicle (axillary or mid‐humeral) and there was no significant difference in the risk of Horner's syndrome (1.6% versus 0.4%; RR of Horner's syndrome with ICB 2.03, 95% CI 0.50 to 8.25, P < 0.32, I2 = 0%). However, when ICB was compared to blocks above the clavicle (supraclavicular or parascalene) in the other five studies (Caruselli 2005; De Jose Maria 2008; Koscielniak‐N 2009; Tran 2009; Yang 2010), the risk of Horner's syndrome was significantly lower with ICB (2.9% versus 24.3%; RR of Horner's syndrome 0.09, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.21, P < 0.00001, I2 = 5%).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks, Outcome 11 Horner's syndrome.

There was no difference between the ICB and other blocks in the observed risk of any of the other reported complications (Table 2). The overall complication rate was low; in particular, it should be noted that there were no instances of documented pneumothorax in 558 participants who received an ICB.

1. Complications of block procedurea.

| Complication | Infraclavicular block | All other blocks | Overall rate | RR (95% CI)c | P value |

| Pneumothorax | 0/558(0) | 2/557 (0.4) | 2/1115 (0.2) | 0.20 (0.01, 4.06) | 0.29 |

| Vascular puncture | 36/653 (5.5) | 47/691 (6.8) | 83/1344 (6.2) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.18) | 0.25 |

| Horner's syndrome | 10/465 (2.2) | 61/504 (12.1) | 71/969 (7.3) | 0.19 (0.10, 0.35) | <0.0001 |

| Transient neurological deficit | 12/470 (2.6) | 9/509 (1.8) | 21/979 (2.1) | 1.35 (0.56, 3.25) | 0.51 |

| Systemic LAb toxicity | 1/412 (0.2) | 3/542 (0.7) | 4/954 (0.4) | 0.37 (0.04, 3.50) | 0.38 |

| Phrenic nerve palsy | 0/60 (0) | 7/59 (11.9) | 7/119 (5.9) | 0.07 (0.00, 1.12) | 0.06 |

a. All complication rates are reported as n/N (%).

b. LA: local anaesthetic.

c. RR: risk ratio with respect to infraclavicular block, CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Infraclavicular block (ICB) is as effective as other techniques of brachial plexus blockade for providing surgical anaesthesia of the lower arm (Table 1), with an average success rate of 88% in the studies included in this review (Table 3). Subgroup analysis by method of nerve localization (ultrasound or neurostimulation) and by the different comparator block techniques did not show a significant difference in anaesthetic efficacy, with one possible exception. The ICB may be a superior technique compared to the single‐injection axillary block; as there was a significantly lower risk of requiring general anaesthesia and of failing to achieve sensory block of the musculocutaneous nerve with ICB. The latter observation is not surprising given that the musculocutaneous nerve has usually separated from the brachial plexus in the axilla and is therefore prone to being missed unless it is deliberately sought out with an additional injection with axillary block.

2. Success rate of surgical anaesthesia.

| Study | Infraclavicular block (%) | All other blocks (%) |

| Arcand 2005 | 79.5 | 86.8 |

| Caruselli 2005 | 61.1 | 88.9 |

| De Jose Maria 2008 | 92.1 | 95.0 |

| Deleuze 2003 | 90.0 | 88.0 |

| Ertug 2005 | 80.0 | 86.7 |

| Fleischmann 2003 | 100.0 | 80.0 |

| Frederiksen 2010 | 95 | 77.5 |

| Fredrickson 2009 | 93.3 | 63.3 |

| Heid 2005 | 96.7 | 100.0 |

| Kapral 1999 | 90.0 | 85.0 |

| Koscielniak‐N 2000 | 53.3 | 82.8 |

| Koscielniak‐N 2005 | 85.0 | 92.5 |

| Koscielniak‐N 2009 | 93.3 | 78.0 |

| Minville 2005 | 91.7 | 95.0 |

| Minville 2006 | 90.4 | 94.2 |

| Niemi 2007 | 62.1 | 46.7 |

| Rettig 2005 | 96.7 | 83.3 |

| Song 2011 | 100 | 100 |

| Tedore 2009 | 91.8 | 84.3 |

| Tran 2009 | 95.0 | 96.3 |

| Yang 2010 | 88.0 | 86.0 |

| Overall | 88.2 | 86.0 |

In the first version of this review, we observed a slightly higher risk of requiring supplementation of surgical anaesthesia following an ICB compared to other blocks, and we suggested that one reason could be a slower onset time of sensory block. In the current update, there was no difference in the risk of requiring supplementation (Table 1). Our best estimate of the mean difference in onset time between an ICB and all other blocks, while still statistically significant, has also decreased from 3.9 to 1.9 minutes (Table 1), and is now of little clinical significance. Six out of seven of the new studies identified and included in this update utilized an ultrasound‐guided technique of ICB, and it is likely that the increased accuracy of local anaesthetic injection around the brachial plexus afforded by ultrasound contributed to both of these outcomes (McCartney 2010). This is supported by the subgroup analysis of ultrasound‐guided ICB, which showed no significant difference in onset time between ICB and all other blocks.

The first version of the review also found that surgical anaesthesia was significantly less likely following ICB in the subgroup of studies that used variable weight‐based local anaesthetic volumes of less than 40 ml. We postulated that this was because the cords of the brachial plexus are dispersed around the axillary artery in the infraclavicular region and thus an adequate volume is important in ensuring complete local anaesthetic spread. In the current update, there was no difference in the incidence of surgical anaesthesia in the subgroup of studies using weight‐based dosing or local anaesthetic volumes less than 40 ml. Once again, this change may be due to the increased accuracy of the ultrasound‐guided technique of ICB.

One advantage of the ICB over other brachial plexus blocks is a decreased risk of tourniquet pain, which in turn may reduce the need for additional intraoperative sedatives or analgesics (Table 1). The decrease in tourniquet pain has been attributed to local anaesthetic spread to the intercostobrachial nerve. This arises from the second thoracic nerve root and runs through the axilla in close proximity to the axillary vein and infraclavicular space to supply part of the medial surface of the upper arm (Sandhu 2006). The ICB was also faster to perform than the multiple‐injection techniques of axillary block and mid‐humeral block, by an average time difference of three and five minutes respectively (Table 1). This advantage is slightly offset by the increased sensory block onset time observed with ICB.

The overall complication rate of the ICB was low and no different from that observed with the other blocks. In particular, there were no reported cases of pneumothorax. The risk of Horner's syndrome was also significantly reduced with the ICB approach. The proximity of the axillary artery and vein to the brachial plexus accounts for the fact that vascular puncture was the most commonly observed complication of ICB. This is a consideration in patients with coagulation abnormalities as the relatively deeper location of the axillary vessels in the infraclavicular region may make it harder to achieve haemostasis by compression.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This update includes 22 studies and 1732 participants in total. Six studies (514 participants) compared ICB to supraclavicular block, and six studies (617 participants) compared the ICB to a multiple‐injection axillary block technique. Analysis of both these subgroups showed no significant differences in surgical anaesthesia. Since the late 2000s, the trend in peripheral nerve block techniques and regional anaesthesia has been to use ultrasound guidance rather than surface landmarks or neurostimulation to locate nerves (Chin 2008). Nine out of the 22 studies (894 participants) utilized ultrasound‐guided ICB, and seven of these studies compared it to another ultrasound‐guided brachial plexus block (supraclavicular or axillary). Subgroup analysis by method of nerve localization (ultrasound‐guided or neurostimulation‐guided) did not show a significant difference between ICB and other brachial plexus blocks in either group. We therefore believe that this review is a valid representation of the available evidence addressing the question of which brachial plexus block is most suited to regional anaesthesia of the lower arm, and that the findings are applicable to current practice.

Quality of the evidence

The majority of the studies were methodologically sound with overall low risk of bias. The commonest reason for unclear risk of bias was insufficient detail regarding random sequence generation (10 studies) and allocation concealment (13 studies). Ten studies did not explicitly describe blinding of the outcome assessor. The most significant methodological limitation that was identified was performance bias. In two studies (Frederiksen 2010; Koscielniak‐N 2009) the investigators stated that the ICB was the preferred approach to the brachial plexus at their institution, and that this may have influenced study outcomes in favour of the ICB. In another study (De Jose Maria 2008) the technique of ICB used may have been suboptimal, contributing to a perceived higher failure rate of ICB. A sensitivity analysis showed, however, that there was still no difference between ICB and other brachial plexus blocks with respect to the primary outcome of adequate surgical anaesthesia when these three studies were excluded.

Potential biases in the review process

There was significant statistical heterogeneity in many of the comparisons, which we believe is largely due to the clinical diversity in the interventions studied. We attempted to address this by subgroup analysis, where appropriate, and by applying the random‐effects model.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Tran 2007 reviewed the evidence from randomized controlled trials regarding the optimal approaches and techniques for brachial plexus blockade. They identified nine studies that compared ICB with either supraclavicular block, axillary block, or mid‐humeral block. The conclusions of their narrative review were consistent with the findings of this review, namely that the anaesthetic efficacy of ICB is similar to that of supraclavicular block and multiple‐injection axillary or mid‐humeral block, but is superior to that of a single‐injection axillary block. In another narrative review restricted to ultrasound‐guided brachial plexus blocks, McCartney 2010 identified only four studies that compared ICB to supraclavicular block and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to make a definitive recommendation on the relative efficacy and adverse effects of the two techniques.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Infraclavicular block is an excellent choice for providing surgical anaesthesia of the lower arm. It is as safe and effective as any other technique of brachial plexus block, regardless of whether ultrasound or neurostimulation guidance is used. It is also more effective at preventing tourniquet pain. At the same time, the infraclavicular block is faster to perform than the more complex multiple‐injection techniques of axillary block and mid‐humeral block that target individual nerves. A possible influence of local anaesthetic volume and block onset time on efficacy of the infraclavicular block was observed in the original review; this is no longer apparent in this update, and is likely to be due to the increased accuracy of injection with ultrasound guidance.

Implications for research.

Ultrasound guidance has largely replaced neurostimulation in modern brachial plexus blockade, and has improved the efficacy of all the commonly‐used techniques. Given the high success rates reported in recent studies, it is unlikely that additional comparative trials will lead to a demonstration of a difference in efficacy between the various techniques. Going forward, it is our opinion that learning curves, ease of block performance, and adverse effects will be the key factors that determine an individual practitioner's choice of which brachial plexus block to perform. We therefore recommend that future research should focus on these areas.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 August 2013 | New search has been performed | In the previous version (Chin 2010), the databases were searched

until September 2008. For this update, we re‐ran the

searches until 7 June 2013. The risk of bias tool was updated. The abstract and plain language summary were updated. The discussion section was updated. |

| 8 August 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This review is an update of the previous Cochrane

systematic review (Chin

2010) that included 15 randomized controlled

trials (RCTs). Two new authors, Sanjib Das Adhikary and Husni Alakkad, have replaced the previous authors Veerabadran Velayutham and Victor Chee in updating this version. We identified 13 potential new papers, we included seven studies that met our inclusion criteria. We excluded two papers which were non‐RCTs and two studies which did not examine the outcomes of interest in this review. Two additional studies were only published as abstracts and were not included or analysed as data and methodological details were lacking. In general our review reaches the same primary conclusions as Chin 2010. However the inclusion of more trials increased the precision of the estimates of the relative risk of inadequate surgical anaesthesia, and removed some of the slight differences in secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses that had been noted in the previous review (Chin 2010), e.g. risk of requiring supplementation, risk of inadequate surgical anaesthesia in studies using weight‐based local anaesthetic dosing. We also applied several additional sensitivity and subgroup analyses, which supported the overall results. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2010 | Amended |

|

| 1 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

Acknowledgements

For this review update we continue to be grateful for the help and advice received for the previous version from the people listed in the previous acknowledgements (Chin 2010). We would like to acknowledge the contributions made to the previous version by Veerabadran Velayutham and Victor Chee, which we have drawn upon in this updated version.

We are very grateful to Karen Hovhannisyan for running the search strategies for this update, and to Jane Cracknell for her continued support and patience.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy (via OvidSP)

1. (((an?esth* or analg*) adj3 regional) or ((nerve or plexus or brachial) and (block* or an?esthe* or analg*))).mp. or (exp Brachial Plexus/ and (exp Anesthesia, Conduction/ or exp Analgesia/)) 2. ((infraclavicul* or coracoids*) and (axillar* or interscalene or supraclavicular or brachial or humeral)).mp. 3. 1 and 3

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy (via OvidSP)

1. (((an?esth* or analg*) adj3 regional) or ((nerve or plexus or brachial) and (block* or an?esthe* or analg*))).mp. or exp regional anesthesia/ 2. ((infraclavicul* or coracoids*) and (axillar* or interscalene or supraclavicular or brachial or humeral)).mp. 3. 1 and 2

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Brachial Plexus explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Anesthesia, Conduction explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Analgesia explode all trees #4 (#1 AND ( #2 OR #3 )) #5 ((an?esth* or analg*) near regional) or ((nerve or plexus or brachial) and (block* or an?esthe* or analg*)) #6 (#4 OR #5) #7 ((infraclavicul* or coracoids*) and (axillar* or interscalene or supraclavicular or brachial or humeral)) #8 (#6 AND #7)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Infraclavicular block versus all other blocks.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adequate surgical anaesthesia | 21 | 1662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.60, 1.30] |

| 1.1 At 30 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 14 | 1051 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.51, 1.52] |

| 1.2 At 15 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 3 | 332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.35, 4.42] |

| 1.3 At 60 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 4 | 279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.44, 1.16] |

| 2 Adequate surgical anaesthesia (subgrouped by LA volume and block type) | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Local anaesthetic volume weight‐based or < 40 mls | 9 | 717 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.38, 1.68] |

| 2.2 Local anaesthetic volume ≥ 40 mls | 6 | 612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.52, 1.37] |

| 2.3 Single‐injection axillary block | 3 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.19, 2.45] |

| 2.4 Multiple‐injection axillary block | 6 | 617 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.45, 2.15] |

| 2.5 Supraclavicular block | 6 | 514 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.33, 1.40] |

| 2.6 Mid‐humeral block | 2 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.63, 4.43] |

| 2.7 Ultrasound‐guided infraclavicular block | 8 | 774 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.29, 1.06] |

| 2.8 Neurostimulation‐guided infraclavicular block | 13 | 888 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.77, 1.78] |

| 3 Supplementation required to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia | 17 | 1412 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.62, 1.46] |

| 3.1 At 30 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 11 | 861 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.49, 1.86] |

| 3.2 At 15 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 3 | 332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.34, 3.66] |

| 3.3 At 60 minutes post‐block assessment interval | 3 | 219 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.48, 1.31] |

| 4 General anaesthesia required to achieve adequate surgical anaesthesia | 20 | 1584 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.36, 1.21] |

| 4.1 Single‐injection axillary block | 6 | 289 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.13, 0.88] |

| 4.2 Other block techniques | 14 | 1295 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.50, 2.73] |

| 5 Complete sensory block in individual nerve territories within 30 minutes | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Musculocutaneous nerve (all blocks) | 11 | 786 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.51, 1.62] |

| 5.2 Musculocutaneous nerve (single‐injection axillary block) | 3 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.27, 0.78] |

| 5.3 Axillary nerve (all blocks) | 5 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.25, 1.68] |

| 5.4 Radial nerve (all blocks) | 11 | 786 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.47, 1.76] |

| 5.5 Median nerve (all blocks) | 11 | 786 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.67, 1.45] |

| 5.6 Ulnar nerve (all blocks) | 11 | 786 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.52, 1.41] |

| 5.7 Medial brachial cutaneous nerve (all blocks) | 4 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.63, 2.37] |

| 5.8 Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (all blocks) | 4 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.33, 2.27] |

| 6 Tourniquet pain | 8 | 615 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.47, 0.92] |

| 7 Onset time of adequate surgical anaesthesia (minutes) | 9 | 726 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.23, 3.64] |

| 7.1 Neurostimulation‐guided infraclavicular block | 4 | 335 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.85 [3.20, 4.50] |

| 7.2 Ultrasound‐guided infraclavicular block | 5 | 391 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [‐2.24, 3.27] |

| 8 Duration of postoperative analgesia (minutes) | 9 | 635 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.98 [‐6.29, 14.25] |

| 9 Block performance time (minutes) | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Single‐injection axillary block | 2 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.17 [1.84, 4.50] |

| 9.2 Multiple‐injection axillary block | 6 | 391 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.67 [‐3.36, ‐1.98] |

| 9.3 Supraclavicular block | 3 | 260 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.81 [‐1.35, ‐0.27] |

| 9.4 Mid‐humeral block | 2 | 224 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.80 [‐6.04, ‐3.57] |

| 9.5 Ultrasound‐guided infraclavicular block | 7 | 501 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.61 [‐2.63, ‐0.58] |

| 10 Pain associated with block performance (scored 0‐10) | 8 | 650 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.56 [‐1.25, 0.14] |

| 11 Horner's syndrome | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Block below clavicle | 6 | 514 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [0.50, 8.25] |

| 11.2 Block above clavicle | 5 | 455 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.04, 0.21] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arcand 2005.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | N = 80; adult; BMI <35; 56 male, 24 female; ASA 1‐3; surgery of the distal arm/forearm/hand; Canadian study | |

| Interventions |

Injectate in both blocks: bupivacaine 0.5% and lidocaine 2% in 1:3 ratio with 1:200,000 epinephrine in volume of 0.5 ml/kg to a maximum of 40 ml Sedation for block: IV midazolam 0.5‐2 mg and fentanyl 25‐100 μg as needed Intraoperative sedation: propofol infusion when needed |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Blocks performed by single physician, a resident with

previous experience of 11 blocks in each

technique. Sensory block in individual territories at specific time points is defined for this review as no sensation (rather than blunt or no sensation), so as to be consistent with studies using a 2‐point (all‐or‐none) scale of block intensity. No dichotomous data on block‐associated pain was available. There were 2 failures to perform block (unable to visualize plexus) in the supraclavicular group; 1 failure to perform block (unable to obtain stimulation) in the infraclavicular group. These were included only in the analysis of block performance time. Other outcomes analysed on an available‐case basis (infraclavicular n=39, supraclavicular n = 38). Block performance time was only reported as mean values and subdivided by early or late stage of study. There was evidence of a learning effect on the block performance time, which became shorter as the study progressed. Abbreviations: AN = axillary nerve, MABCN = medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, MBCN = medial brachial cutaneous nerve, MCN = musculocutaneous nerve, MN = medial nerve, RN = radial nerve, UN = ulnar nerve |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of randomization method in text |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of randomization method in text |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No mention of blinding of patients or outcome assessors in text |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Failure to perform block in two patients (infraclavicular) and one patient (supraclavicular). Only block performance time, and no other outcomes, were reported for these patients |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All pre‐specified and relevant outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | A weight‐based formula was used to calculate local anaesthetic volume: 0.5ml/kg up to a maximum of 40ml. The use of lower volumes (<40ml) may have reduced infraclavicular block success |

Caruselli 2005.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial | |