Abstract

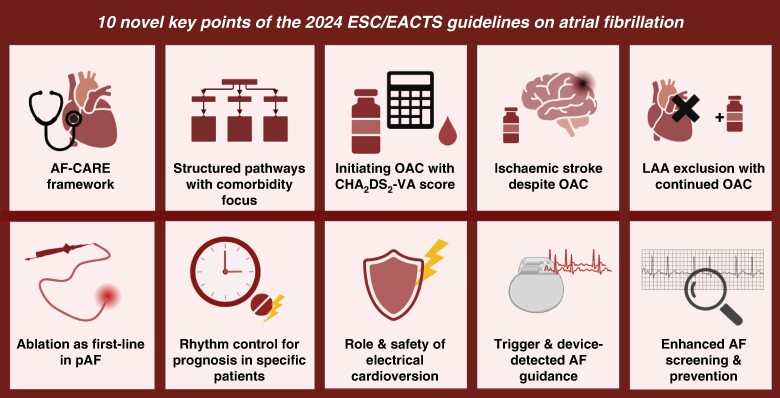

Atrial fibrillation (AF) remains the most common cardiac arrhythmia worldwide and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) have recently released the 2024 guidelines for the management of AF. This review highlights 10 novel aspects of the ESC/EACTS 2024 Guidelines. The AF-CARE framework is introduced, a structural approach that aims to improve patient care and outcomes, comprising of four pillars: [C] Comorbidity and risk factor management, [A] Avoid stroke and thromboembolism, [R] Reduce symptoms by rate and rhythm control, and [E] Evaluation and dynamic reassessment. Additionally, graphical patient pathways are provided to enhance clinical application. A significant shift is the new emphasis on comorbidity and risk factor control to reduce AF recurrence and progression. Individualized assessment of risk is suggested to guide the initiation of oral anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolism. New guidance is provided for anticoagulation in patients with trigger-induced and device-detected sub-clinical AF, ischaemic stroke despite anticoagulation, and the indications for percutaneous/surgical left atrial appendage exclusion. AF ablation is a first-line rhythm control option for suitable patients with paroxysmal AF, and in specific patients, rhythm control can improve prognosis. The AF duration threshold for early cardioversion was reduced from 48 to 24 h, and a wait-and-see approach for spontaneous conversion is advised to promote patient safety. Lastly, strong emphasis is given to optimize the implementation of AF guidelines in daily practice using a patient-centred, multidisciplinary and shared-care approach, with the simultaneous launch of a patient version of the guideline.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Management, Guidelines

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Overview of 10 novel key points in the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on the management of atrial fibrillation. AF, atrial fibrillation; LAA, left atrial appendage; OAC, oral anticoagulant; pAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, atrial fibrillation (AF) remains common and continues to have a large impact on those living with AF, their relatives, and wider society.1–3 Guidelines for the management of AF intend to maintain a 4-year update cycle, with interim updates targeted every 2 years. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) 2024 AF guidelines aim to evaluate and summarize available evidence to assist health professionals in optimizing their diagnostic or therapeutic approach for individual patients with AF.4 The guideline was developed by a specifically assigned task force representing the ESC and EACTS, with contribution by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and endorsement by the European Stroke Organisation. In this iteration of the AF guidelines, 130 recommendations are provided with underpinning evidence from robust clinical research, and a novel structured style is used for each recommendation to aid implementation. In addition, a patient version of the guideline was made available simultaneously (https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Guidelines/Documents/ESC-Patient-Guidelines-Atrial-Fibrillation.pdf). This review aims to highlight 10 novel key aspects of the full ESC/EACTS 2024 Guidelines. Further details can be found in the full ESC/EACTS 2024 AF management guidelines.4

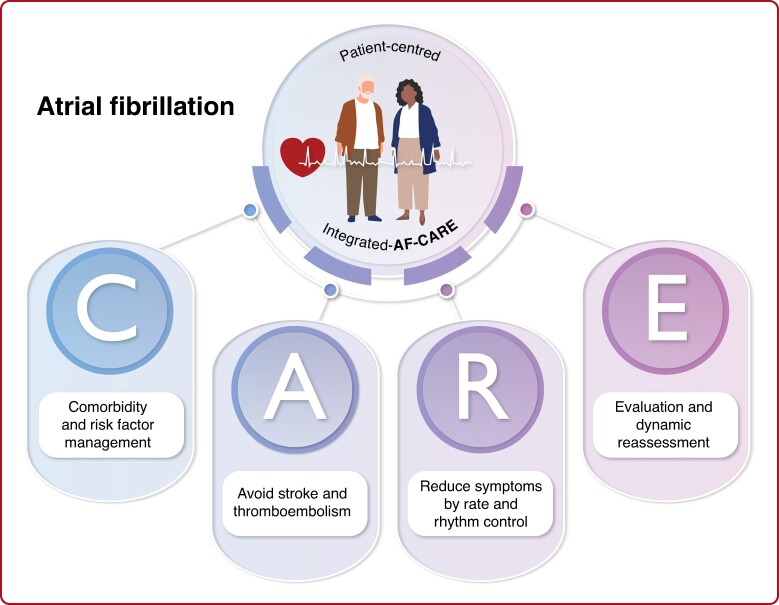

Principles of AF-CARE approach

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF introduced the AF-CARE framework, a structured approach to AF management designed to enhance patient-centred care and outcomes.4,5 AF-CARE builds on previous frameworks,6,7 organizing care into four key pillars that integrate evidence-based management of AF with individualized patient needs (Figure 1). The pillars include: [C] Comorbidity and risk factor management, highlighting and bringing to the forefront the need for thorough evaluation and management of comorbidities and risk factors related to AF; [A] Avoid stroke and thromboembolism, prioritizing stroke and thromboembolism prevention through appropriate anticoagulation; [R] Reduce symptoms by rate and rhythm control, aiming for symptom relief and in specific patient groups adjunctive prognostic benefit; and [E] Evaluation and dynamic reassessment, emphasizing the need for a thorough baseline evaluation of patients with AF, including an echocardiogram for all patients with AF where this might guide treatment decisions, followed by continuous modification of care as patients living with AF and its associated comorbidities and risk factors evolve over time.

Figure 1.

AF-CARE framework. AF, atrial fibrillation; CARE, [C] Comorbidity and risk factor management, [A] Avoid stroke and thromboembolism, [R] Reduce symptoms by rate and rhythm control, [E] Evaluation and dynamic reassessment. Adapted from EHJ 2024.4

The systematic and patient-oriented AF-CARE framework serves as a guide that adapts with each patient, promoting a personalized and adaptive approach to AF management. By aligning care with the changing nature of AF and its associated comorbidities and risk factors, the wishes and needs of patients, and the continuous improvement of the management of AF, AF-CARE aims to improve outcomes and provide equal and optimal quality of care for all those encountering AF.

New patient pathways for atrial fibrillation management with comorbidity and risk factor identification and management as a first step

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines present new structured patient pathways tailored to AF management based on AF temporal patterns—first-diagnosed, paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent. The pathways enhance the clinical application of the AF-CARE framework by providing clear, step-by-step guidance for individualized patient care, ensuring that management strategies can be easily adapted as a patient’s AF and (non-)cardiovascular status changes over time. An interactive mobile app enables a simple and portable approach for healthcare providers to access the 2024 guidelines and is provided free of charge (https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Guidelines-derivativeproducts/ESC-Mobile-Pocket-Guidelines).

A significant shift in the 2024 guidelines is the emphasis on comorbidity and risk factor management. The guidelines set precise targets for managing AF-associated conditions and risk factors for all those comorbidities with a sufficient evidence base, such as hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea, physical activity, and alcohol intake. Nevertheless, patients with AF may have other (non-)cardiovascular comorbidities that relate to AF and may impact management. These comorbidities and risk factors also require attention by patients and their healthcare professionals.8–11 New evidence demonstrates that effective management of comorbidities and risk factors can improve symptoms and quality of life, reduce AF recurrences, slow or prevent AF progression, improve the outcome of rhythm control strategies, and improve prognosis.9–38

By integrating these new comorbidity targets upfront into the patient pathways, the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines reinforce that AF treatment strategies should not only be effective in controlling AF but also tailored to contribute to the broader health needs of each patient.

Focus on providing oral anticoagulation using a locally validated risk score or the CHA2DS2-VA score

Atrial fibrillation significantly heightens the risk of thromboembolism, including ischaemic stroke, regardless of the temporal pattern of AF.3,39,40 Without appropriate treatment, the risk of ischaemic stroke in patients with AF is elevated five-fold, and one in every five strokes is linked to AF.41 Given this substantial risk, oral anticoagulation [preferably a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC)] is advised for all eligible patients, except those at low risk of incident stroke or thromboembolism. The effectiveness of oral anticoagulation in preventing ischaemic stroke in patients with AF is well-documented.42,43 Antiplatelet therapies alone are not indicated for stroke prevention in AF.44,45

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF introduced an important change in stroke risk assessment and oral anticoagulation initiation. An individualized approach to risk is advised, taking into account all potential thromboembolic risk factors. In the absence of locally validated risk scores, the CHA2DS2-VA score replaces the CHA2DS2-VASc score, with points assigned to the well-known stroke risk factors: congestive heart failure (one point), hypertension (one point), age ≥ 75 years (two points), diabetes mellitus (one point), prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack/arterial thromboembolism (two points), vascular disease (one point), and age 65–74 years (one point). Notably, the CHA2DS2-VA score omits consideration of gender, with the rationale that female sex does not contribute to decision making and is a risk modifier only in older patients that should already be receiving anticoagulation.46–48 In previous guidelines, separate recommendations were given for women and men, adding unnecessary complexity in clinical practice.6 The modification to CHA2DS2-VA seeks to simplify stroke risk assessment, with consistent thresholds regardless of gender.49

Oral anticoagulation using a DOAC, unless the patient has a mechanical valve or moderate–severe mitral stenosis, is advised for patients with AF with clearly elevated thromboembolic risk (CHA2DS2-VA score ≥2). Oral anticoagulation is advised to consider for patients with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1. Physicians should explicitly discuss with their patients that decision making on anticoagulation treatment is dependent on the presence of stroke risk factors, or the presence of amyloidosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or mitral stenosis, and not on the type of AF or any rhythm control strategy employed. Despite maintenance of sinus rhythm or the absence of any AF-related symptoms, patients should continue oral anticoagulation based on the perceived risk of stroke and thromboembolism.42,50–53 Indeed, evidence demonstrates that there is no temporal relationship between ischaemic stroke occurrence and AF episodes.54–56

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF also advocate for periodic reassessment of thromboembolic risk and attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors, to ensure that anticoagulation therapy remains appropriately aligned with each patient’s dynamic risk profile. These updates aim to enhance precision in stroke risk assessment and promote more widespread use of appropriate oral anticoagulation in patients with AF.57–60

Ischaemic stroke despite anticoagulation

Oral anticoagulation is known to substantially reduce the risk of ischaemic stroke in patients with AF, yet a residual risk still remains.61,62 One-third of patients who suffer an ischaemic stroke are already on anticoagulation, which may be associated with factors including non-AF-associated stoke mechanisms, non-adherence, inadequate dosing, and ineffective anticoagulation.63 The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF introduced a new section to address these complex issues.

A thorough diagnostic work-up is advised for patients with AF who experience ischaemic stroke despite being on oral anticoagulation. This assessment should encompass a detailed and comprehensive evaluation of non-cardioembolic causes, vascular risk factors, medication dosage, and adherence to prevent recurrent events. Additionally, the guidelines explicitly advise against adding antiplatelet therapy to oral anticoagulation for preventing recurrent embolic stroke, due to an increased risk of bleeding, and no proven benefit.64,65 While switching from a vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (VKA) to a DOAC may be beneficial for certain patient groups, the guidelines caution against routine switches from one DOAC to another, or from a DOAC to VKA without a clear indication, because these changes have not been demonstrated to be effective and may be harmful in some patients.61,64,65

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF also emphasize avoiding a lower dose of DOAC, unless specific criteria are met (e.g. established renal dysfunction). Inappropriate dose reductions can heighten stroke risk without diminishing bleeding risks, underscoring the importance of adhering to full DOAC dosage to avoid preventable thromboembolism.66–69 New recommendations in the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF aim to enhance the management of patients with AF experiencing a stroke despite anticoagulation, with a focus on appropriate dosing and informed treatment decisions to improve patient outcomes.

Left atrial appendage exclusion as an adjunct to oral anticoagulation in all concomitant, hybrid, or endoscopic surgery procedures

The left atrial appendage has long been recognized as a primary anatomical target for stroke prevention in patients with AF, as more than 90% of AF-related left atrial thrombi are located within it.70 The LAAOS III trial investigated the additive protective role of concomitant left atrial appendage occlusion in patients with AF undergoing cardiac surgery.70 During a 3-year follow-up, left atrial appendage occlusion significantly reduced ischaemic stroke or thromboembolism by one-third.70 Notably, several techniques were used for occlusion achievement (amputation with suture closing, stapling, or epicardial device closure) and 77% of patients with AF continued to receive oral anticoagulation at the end of the study. The incidence of safety events (perioperative bleeding, heart failure, or death) was similar between the compared groups.71 Based on the existing evidence, surgical closure of the left atrial appendage is recommended as an adjunct to oral anticoagulation in patients with AF undergoing cardiac surgery to prevent ischaemic stroke and thromboembolism.70,72–76

Left atrial appendage closure can also be performed during endoscopic or hybrid AF ablation with the use of external clip devices. Observational studies have demonstrated that left atrial appendage clipping during thoracoscopic AF ablation is feasible (95% complete left atrial appendage closure), safe (no intraoperative complications), and associated with a lower-than-expected rate of thromboembolism in patients maintaining post-procedural oral anticoagulation.77 Taking into account the existing non-randomized evidence,78 the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF support that any surgical closure of the left atrial appendage should be considered as an adjunct to oral anticoagulation in patients with AF undergoing endoscopic or hybrid AF ablation to prevent ischaemic stroke and thromboembolism.

Catheter ablation as first-line rhythm control option in suitable patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Catheter ablation is a well-acknowledged invasive treatment for AF.79 Evidence-based credentials have established catheter ablation as the treatment of choice in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF who are intolerant or resistant to anti-arrhythmic drugs.80–83 Based on accumulating evidence, the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF upgraded the role of catheter ablation as first-line rhythm control treatment option in anti-arrhythmic drug-naive patients with paroxysmal AF. This upgrade is supported by multiple randomized controlled trials, demonstrating that catheter ablation has superior efficacy and similar safety in comparison to anti-arrhythmic drugs regarding reduction of AF recurrences, alleviation of patient symptoms, improvement of quality of life, and delayed progression of AF.84,85–93

While catheter ablation is now a potential first option for maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with AF, this does not mean that every patient with paroxysmal AF should undergo catheter ablation. In essence, patients with paroxysmal AF should be informed about the possibility of catheter ablation, as part of the [R] pillar, after managing the [C] and [A] pillars. Every patient suitable for catheter ablation should be informed about the need for holistic AF treatment in the context of the entire AF-CARE pathway. Furthermore, every treatment decision in the management of patients with AF should be made together with each patient (shared decision making), considering the wishes and needs of each patient, and all potential treatment options in the context of respective risks and benefits. Note that ‘first-line’ is not synonymous with ‘first-time’, as several studies have demonstrated the unpredictable natural course of AF with one-quarter of patients presenting with no recurrence or a single AF recurrence during 3-year follow-up with continuous monitoring.94 The superiority of catheter ablation as first-line treatment in paroxysmal AF was demonstrated in randomized trials including patients with a substantial number of AF recurrences (e.g. median value of three symptomatic AF episodes per month in the EARLY-AF trial).85 Therefore, the pertinent favourable results should not be extrapolated to patients having experienced limited paroxysmal AF episodes.

Rhythm control in selected patients can improve prognosis

Rhythm control is effective in alleviating AF-related symptoms and improving quality of life.95,96 In addition, in specific patient categories, sinus rhythm maintenance can also offer prognostic benefits. The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF have issued specific recommendations for rhythm control in these patient groups.

Implementation of a rhythm control strategy is advised to consider within 12 months of an AF diagnosis in selected patients with high risk of stroke or thromboembolism to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization, as evidenced by the Early treatment of Atrial fibrillation for Stroke prevention Trial (EAST-AFNET 4).97,98 It is crucial to consider that the characteristics of the enrolled patients in EAST-AFNET-4 (median duration since AF diagnosis 36 days, 54% in sinus rhythm and 30% asymptomatic at baseline) may not represent all patients with AF encountered in everyday practice.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that ablation may also confer benefits extending beyond symptom control in selected patient categories. Catheter ablation is advised in patients with AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction presumed to be due to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, with the aim of reversing left ventricular dysfunction.99,100 Several clinical factors [New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, heart failure aetiology, and AF pattern] and imaging factors (left atrial dilatation and presence of atrial or ventricular fibrosis) may aid in the selection of suitability for catheter ablation.101 Furthermore, AF catheter ablation is advised to be considered in selected patients with AF and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, where this could be expected to reduce heart failure hospitalization and mortality.99,102–106 Nevertheless, data on the prognostic benefit of catheter ablation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients are not fully consistent, since there are also negative trials.107,108 Therefore, the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF emphasize the need for a patient-centred individualized approach in this patient group.

Prioritize patient safety during cardioversion of atrial fibrillation

Cardioversion of AF is associated with a risk of stroke or thromboembolism in patients who have not received appropriate anticoagulation or where imaging has not excluded an intra-cardiac thrombus.50,51,109,110 This risk is variable and depends on patient characteristics and the duration of AF. The previously employed AF duration threshold of 48 h, which allowed early cardioversion without the need for anticoagulation or thrombus screening using transoesophageal echo, has been questioned by observational data.111–113 Furthermore, documentation of AF onset is dependent on patient self-reporting, and thus the reliable estimation of AF duration remains challenging. In the context of prioritizing safety, the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF recommend a shorter cut-off of 24 h known duration of AF for early cardioversion in patients who have not received at least 3 weeks of effective anticoagulation or thrombus exclusion with transoesophageal echocardiography.

Electrical cardioversion is highly effective in restoring sinus rhythm and is valuable in various clinical scenarios. In emergency settings, electrical cardioversion is recommended for patients with haemodynamic instability to improve immediate outcomes. Electrical cardioversion may also be used when the impact of AF-related symptomatology is not clear, or as a diagnostic tool when the benefits of restoring sinus rhythm are uncertain. The correlation between symptoms and heart rhythm is poor in patients with intermittent AF, since patient symptoms are not specific and may be due to coexistent comorbidities.114 A substantial percentage of patients without self-reported AF-related symptoms may experience improvement in their symptomatic status and functional class after electrical cardioversion.115 The diagnostic utility of electrical cardioversion may also prove helpful in patients with AF and impaired left ventricular function when AF-mediated tachycardiomyopathy is a differential diagnosis. In these cases, electrical cardioversion can assess the potential recovery of systolic function with sinus rhythm restoration.115 If AF is identified as the primary driver of systolic dysfunction, the patient could then be considered for catheter ablation.

Despite the utility of electrical cardioversion, spontaneous conversion to sinus rhythm is very likely in patients presenting with recent onset AF. In the RACE 7 ACWAS trial (Rate Control vs. Electrical Cardioversion Trial 7—Acute Cardioversion vs. Wait and See), comparing an early cardioversion with a wait-and-see approach, 69% of patients in the wait-and-see group (receiving only rate-control medications) experienced spontaneous recovery to sinus rhythm.116 Furthermore, the wait-and-see strategy was non-inferior to early cardioversion in maintaining sinus rhythm at 4 weeks, with more than 90% of patients in sinus rhythm. Therefore, a wait-and-see approach for spontaneous conversion to sinus rhythm should be considered as treatment option in shared decision making in patients without haemodynamic compromise as an alternative to immediate cardioversion. Regardless of approach and whether electrical or pharmacological cardioversion is used, it remains crucial that patients receive adequate therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 3 weeks before scheduled cardioversion, either by adherence to direct oral anticoagulants or consistent INR values >2 if using vitamin K antagonists.

New guidance for trigger-induced and device-detected sub-clinical atrial fibrillation

Trigger-induced AF is a new AF episode in close proximity to a precipitating and potentially reversible factor. The most common precipitating factor for AF is sepsis, which is linked to an AF prevalence of 9–20%, and the chances of AF development increase with high degrees of inflammation.117–120 Other triggers include alcohol use, illicit drugs, and chronic inflammatory conditions. New in the 2024 guidelines, is advice to manage trigger-induced AF following the AF-CARE principles, emphasizing the need to address underlying reversible triggers and potential other comorbidities and risk factors. Long-term oral anticoagulation in patients with trigger-induced AF is advised to be considered according to perceived individual risk of stroke or thromboembolism, and started when potential increased bleeding risks related to certain acute triggers have been addressed. This advice reflects the observational evidence that these patients have similar AF recurrence rates, thromboembolic, and mortality risk as patients with clinical AF, although randomized trials are lacking in this context.121–124

New guidance has also been provided for device-detected sub-clinical AF (asymptomatic episodes of AF detected on continuous monitoring devices). The ARTESiA trial (Apixaban for the Reduction of Thromboembolism in Patients With Device-Detected Sub-Clinical Atrial Fibrillation) demonstrated that apixaban reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism compared with aspirin, although it also increased major bleeding risk.125 The NOAH trial (non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial high rate episodes), which examined edoxaban compared with placebo, was terminated early due to futility and safety concerns, and found increased bleeding risk without associated efficacy.126 With the currently available evidence, direct oral anticoagulants may be considered for patients with device-detected sub-clinical AF, high stroke risk, and low bleeding risk, acknowledging the high chance of progression to clinical AF (6–9% per year), but also the bleeding risk accompanying anticoagulation. Whether a threshold exists based on certain duration of AF (episodes or burden) is still unclear.127

Expanded strategies for screening and early detection of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained arrhythmia worldwide and yet AF often remains undetected; its prevalence is expected to rise due to population growth, ageing, and improved survival from other cardiac conditions.128,129 The guidelines provide expanded approaches to population-based screening, early detection, and primary prevention of AF.

Population-based screening of AF through systematic programmes is now clearly distinguished from opportunistic detection during routine healthcare visits. Routine heart rhythm assessment during healthcare contact is recommended for all individuals aged ≥65 years to facilitate earlier detection of AF.130,131 Population-based screening using a prolonged non-invasive ECG-based approach in patients with AF aged ≥75 years or ≥65 years with additional CHA2DS2-VA risk factors should be considered to ensure timely detection of AF.132–135 The evidence on refinement of potential screening target populations, optimal screening durations, utility of new diagnostic and consumer wearable technologies, as well as the overall cost-effectiveness of routine and population-based screening is still too sparse to provide clear guidance.95,136

Summary and conclusions

The recently published 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF provide a comprehensive update of the evidence-based recommendations for optimal contemporary management of AF.4

One of the most significant changes is the introduction of the AF-CARE framework. Building on previous approaches, placing [C] Comorbidity and risk factor management at the forefront is a major shift. The proposed benefits are that better comorbidity and risk factor management will substantially contribute to improvement of symptoms and quality of life, reduction of AF recurrences, prevention of AF progression, enhanced effectiveness of rhythm control strategies, and lead to improvement in prognosis.

Concerning [A] Avoidance of stroke and thromboembolism, the new guidelines prioritize prevention through the appropriate use of oral anticoagulation based on locally validated risk scores or the CHA2DS2-VA score (using the same treatment cut-off regardless of gender). In addition, guidance is provided on trigger-induced AF, device-detected sub-clinical AF, and approaches to reduce the residual risk of stroke despite anticoagulation. The role of left atrial appendage occlusion needs further study, but is now indicated in all endoscopic, hybrid, or concomitant cardiac surgery procedures as an adjunct to oral anticoagulation.

Substantial evidence updates have enabled more targeted approaches to [R] Reduce symptoms by rate and rhythm control, necessitating a shared decision-making approach between patients and their multidisciplinary healthcare professionals. Catheter ablation of AF has been upgraded to a first-line rhythm control option in patients with paroxysmal AF in addition to those failing anti-arrhythmic drug therapy. The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF also provide guidance to improve prognosis with rhythm control in selected patients and more detailed information on how to safely perform cardioversion of AF.

Finally, the addition of [E] Evaluation and dynamic reassessment is an important and constructive step to ensure better provision of lifelong, optimal AF management, including identification and timely treatment of changing individual risk factors to prevent progression and adverse outcomes related to AF.

The 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF have introduced patient flow charts that cover the major aspects of AF-CARE, using a consistent writing style for all recommendations (the intervention proposed, the population it is applied to, and the potential value to the patient, followed by any exceptions). Making the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF easier to read and more simple to follow will hopefully lead to better implementation. As evidenced by the ESC’s first randomized trial (STEEER-AF), delivering guideline-adherent management is critical if we are to reduce patient, health care, and societal burdens of AF,137 with a key role for the education of patients, carers, and healthcare professionals.4,138 All recommendations in the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF were supported by detailed supplementary evidence tables to provide a clear insight into all available evidence, limitations, and research gaps. The patient representatives of the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF also designed a patient version of the guidelines, to inform and empower patients with AF about their specific management options, with the goal to improve engagement and self-management of AF, and to facilitate optimal shared decision making.139,140

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff at the European Society of Cardiology Heart House for their assistance to develop the 2024 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on AF, and to the reviewers across many countries that provided their time and expertise to help the guideline task force.

Contributor Information

Michiel Rienstra, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, P.O. Box 30.001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands.

Stylianos Tzeis, Department of Cardiology, Mitera Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Karina V Bunting, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Valeria Caso, Stroke Unit, Santa Maria della Misericordia-University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy.

Harry J G M Crijns, Department of Cardiology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Tom J R De Potter, Department of Cardiology, OLV Hospital, Aalst, Belgium.

Prashanthan Sanders, Centre for Heart Rhythm Disorders, University of Adelaide and Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Emma Svennberg, Department of Medicine Karolinska University Hospital (MedH), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Ruben Casado-Arroyo, Department of Cardiology, H.U.B.-Hôpital Erasme, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium.

Jeremy Dwight, ESC Patient Forum, Sophia Antipolis, France.

Luigina Guasti, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy; Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology, ASST-Settelaghi, Varese, Italy.

Thorsten Hanke, Clinic For Cardiac Surgery, Asklepios Klinikum, Harburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Tiny Jaarsma, Department of Cardiology, Linkoping University, Linkoping, Sweden; Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Maddalena Lettino, Department for Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Diseases, Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori, Monza, Italy.

Maja-Lisa Løchen, Department of Clinical Medicine, UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway; Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, Norway.

R Thomas Lumbers, Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, London, UK; Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK; University College Hospital, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, London, UK.

Bart Maesen, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Inge Mølgaard, ESC Patient Forum, Sophia Antipolis, France.

Giuseppe M C Rosano, Department of Human Sciences and Promotion of Quality of Life, Chair of Pharmacology, San Raffaele University of Rome, Rome, Italy; Department of Cardiology, San Raffaele Cassino Hospital, Cassino, Italy; Cardiovascular Academic Group, St George’s University Medical School, London, UK.

Renate B Schnabel, Cardiology University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site Hamburg/Kiel/Lübeck, Germany.

Piotr Suwalski, Department of Cardiac Surgery and Transplantology, National Medical Institute of the Ministry of Interior and Administration, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland.

Juan Tamargo, Pharmacology and Toxicology School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain.

Otilia Tica, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; Department of Cardiology, Emergency County Clinical Hospital of Bihor, Oradea, Romania.

Vassil Traykov, Department of Invasive Electrophysiology, Acibadem City Clinic Tokuda University Hospital, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Dipak Kotecha, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK.

Isabelle C Van Gelder, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, P.O. Box 30.001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

M.R. reports consultancy fees from Bayer (OCEANIC-AF national PI) and InCarda Therapeutics (RESTORE-1 national PI) to the institution. M.R. reports an unrestricted research grant from the Dutch Heart Foundation and is conducted in collaboration with and supported by the Dutch CardioVascular Alliance, 01-002-2022-0118 EmbRACE. Unrestricted research grant from ZonMW and the Dutch Heart Foundation; DECISION project 848090001. Unrestricted research grants from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: an initiative with the support of the Dutch Heart Foundation; RACE V (CVON 2014–9), RED-CVD (CVON2017-11). Unrestricted research grant from Top Sector Life Sciences and Health to the Dutch Heart Foundation [PPP Allowance; CVON-AI (2018B017)]. Unrestricted research grant from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement; EHRA-PATHS (945260). S.T. reports speaker fees from Bayer (AF). S.T. reports no funding. K.V.B. is funded through a Career Development Fellowship from the British Heart Foundation (FS/CDRF/21/21032). V.C. reports payment for consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member from Pfizer (AF) and EVER Neuro Pharma (Stroke). V.C. is funded through Bayer AG as an executive committee member of the OCEANIC trial programme trials and an unrestricted research grant from Boehringer-Ingelheim (Stroke). H.J.G.M.C. reports payment for consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member from Daiichi Sankyo (AF), Sanofi Aventis (AF), Roche Diagnostics (AF), and Acesion Pharma (AF). H.J.G.M.C. is funded through research grants from DZHK and ZonMW. T.J.R.D.P. reports payment for consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member from Boston Scientific (AF), Biosense Webster (AF), Adagio Medical (AF and SCD), and Abbott Vascular (Other). Stock options in Adagio Medical. T.J.R.D.P. reports no funding. P.S. reports serving on the medical advisory board for Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, CathRx, and Pacemate. The University of Adelaide has received on behalf of P.S. research funds from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Abbott, and Becton Dickenson. P.S. is supported by an Investigator Grant Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. E.S. reports payment for consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member from Pfizer (Arrhythmias, General), Abbott (AF), Astra Zeneca (AF), Bayer (AF), Johnson & Johnson (AF), Bristol Myers Squibb (AF), and Merck Sharp & Dohme (AF). E.S. reports no funding. R.C.A. reports speaker educational fees from St Jude Medical and Johnson & Johnson (2021). R.C.A. reports speaker fees, honoraria, and consultancy fees from Abbott (Arrhythmias, General) and Boston Scientific (Arrhythmias, General) in 2022. R.C.A. reports payment from Abbott (Training and Education) to his institution in 2023. J.D. reports receipt of royalties for intellectual property from Oxford University Press (Cardiovascular medicine) in 2021. J.D. reports employment in the healthcare industry with PassPACES, an education course for candidates for the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians examination, in 2021. J.D. continues to report receipt of royalties for intellectual property from Oxford University Press (Other) in both 2022 and 2023. L.G. reports research funding from Sanofi Aventis (Cardiovascular prevention) in 2021. L.G. reports research funding from Sanofi Aventis (Education/organization of local educational activities) in 2022. L.G. reports payment from Sanofi Aventis (Risk Factors and Prevention) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding to her department or institution in 2023. T.H. reports direct personal payment from Atricure (Atrial Fibrillation Management and LAA management) and Bioventrix (Heart Failure treatment) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2021. T.H. reports direct personal payment from Atricure (Atrial Fibrillation) and Edwards Lifesciences (Valvular Heart Disease) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2022. T.H. reports payment from Atricure (Atrial Fibrillation) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding to his institution in 2023. T.J. reports direct personal payment from Boehringer-Ingelheim (Heart failure) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2021. T.J. reports direct personal payment from Boehringer-Ingelheim (History of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and Allied Professions) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2022. T.J reports payment from Boehringer-Ingelheim (History of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and Allied Professions) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding to her institution in 2023. M.L. reports direct personal payment from Boehringer-Ingelheim (Anticoagulants), Pfizer (Anticoagulants), Bristol Myers Squibb (Anticoagulants), Sanofi Aventis (Antithrombotic agents and lipid-lowering drugs), and Edwards Lifesciences (Percutaneous cardiac devices) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2021. M.L. reports direct personal payment from Bristol Myers Squibb (Atrial Fibrillation, Pharmacology, and Pharmacotherapy), Novartis (Risk Factors and Prevention), and Amarin (Risk Factors and Prevention) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2022. M.L. reports payment from Pfizer (Atrial Fibrillation, Pharmacology, and Pharmacotherapy), Bristol Myers Squibb (Atrial Fibrillation, Pharmacology, and Pharmacotherapy), Daiichi Sankyo (Risk Factors and Prevention), Novartis (Risk Factors and Prevention), and Amarin (Risk Factors and Prevention) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding to her institution in 2023. M.L. reports direct personal payment from Sanofi Aventis (Acute Coronary Syndromes), BMS/Pfizer (Atrial Fibrillation), and Bayer AG (Atrial Fibrillation) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2022. M.L. reports payment from Sanofi Aventis (Atrial Fibrillation), Bayer AG (Atrial Fibrillation), and BMS/Pfizer (Cardiovascular Disease in Special Populations) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding to her institution in 2023. M.L. also reports receipt of royalties for intellectual property from Gyldendal Akademisk Forlag (Publisher) for Atrial Fibrillation and Cardiovascular Disease in Special Populations. R.T.L. reports research funding from Pfizer (Heart Failure) in 2021 and from Pfizer (Genomic research for the identification of drug targets for heart failure, Principal Investigator) in 2022, both under his direct/personal responsibility to his department or institution. R.T.L. also reports ongoing research funding in 2023 from the British Heart Foundation, Health Data Research UK, Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health, and the Pfizer Innovative Target Exploration Network. R.T.L. reports payment from HealthLumen (Myocardial Disease, Research Methodology) and Fitfile (Research Methodology) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2023, as well as funding from Overcome (Chronic Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure) for travel to and attendance of events and meetings unrelated to these activities. R.T.L. further declares that he is a discretionary beneficiary of a trust that holds shares in Norgine BV, a pharmaceutical company, which should be disclosed in view of holding an ESC position. B.M. reports payment from Medtronic (AF) and Atricure (AF) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles in 2021. He also reports research funding from Medtronic (AF) under his direct/personal responsibility to his department or institution. In 2022, B.M. reports payment from Medtronic (Atrial Fibrillation) and Atricure (Atrial Fibrillation) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and other roles, as well as research funding from Medtronic (research grant 1: 95,000 EUR over 2 years, research grant 2: 240,000 EUR over 4 years, Principal Investigator). In 2023, B.M. reports payment from Atricure (Atrial Fibrillation) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and related travel funding, and payment from Medtronic (Atrial Fibrillation) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and travel funding. He also reports research funding from Medtronic for PhD student funding and serves as a PhD supervisor under his direct/personal responsibility to his department or institution. I.M. reports membership with the Danish Heart Association in 2021. G.M.C.R. reports payment from Abbott Laboratories (Dyslipidaemia), Vifor International (Iron Deficiency), Menarini (Ischaemic heart disease/arterial hypertension), and AstraZeneca (speaker fees) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member roles in 2021. In 2022, G.M.C.R. reports payment from AstraZeneca (Chronic Heart Failure), Vifor International (Chronic Heart Failure), Menarini [Coronary Artery Disease (Chronic)/Chronic Coronary Syndromes (CCS)], and Abbott Laboratories (Risk Factors and Prevention) for similar roles. G.M.C.R. is a member of the Scientific Board of the Heart Failure Policy Network. In 2023, G.M.C.R. reports payment from AstraZeneca (Chronic Heart Failure), Vifor International (Chronic Heart Failure), Menarini [Coronary Artery Disease (Chronic)/Chronic Coronary Syndromes (CCS)], and Abbott Laboratories (Risk Factors and Prevention) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, committee member roles, and related travel funding. G.M.C.R. continues his affiliation with the Scientific Board of the Heart Failure Policy Network. R.B.S. reports direct personal payment from Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer (speaker fees) for Atrial Fibrillation (AF) in 2021. R.B.S. has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 648131), from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 847770 (AFFECT-EU), and from the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK e.V.) (81Z1710103); the German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF 01ZX1408A), and ERACoSysMed3 (031L0239). In 2022, R.B.S. received direct personal payment from Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer [Atrial Fibrillation (AF)]. R.B.S. continued to receive funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under Horizon 2020, the European Union’s Horizon Europe research programme under the grant agreement ID: 101095480, German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK e.V.) (81Z1710103 and 81Z0710114), and the German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF 01ZX1408A). In 2023, R.B.S. reports ongoing research funding from the EU, ERACoSysMed3 (031L0239), and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme [grant agreement no. 847770 (AFFECT-EU)], as well as funding from the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK e.V.) (81Z1710103 and 81Z0710114) and the German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF 01ZX1408A). R.B.S. also reports receiving payment from Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb [Atrial Fibrillation (AF)] and Bayer Healthcare (Chronic Heart Failure) for speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member roles, including travel funding related to these activities. P.S. reports direct personal payment from Medtronic (speaker bureau, minimally invasive surgical valve coronary, and arrhythmia treatment) and Atricure (speaker bureau, minimally invasive surgical valve coronary, and arrhythmia treatment) in 2021. In 2022, P.S. received direct personal payment from Medtronic for various services, with four items checked. In 2023, P.S. reports receiving payment from Medtronic for multiple services (four items checked), as well as payment from Atricure for Atrial Fibrillation (AF), including speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, committee member roles, and travel funding related to these activities. O.T. reports travel and meeting support from Sun Wave Pharma (Other) in 2022, independent of the above activities. She is a member of several professional organizations, including the ESC Young National Ambassador for Acute Cardiovascular Care Association, ESC-HFA Scientific Committee on Acute Heart Failure, ESC-HFA Scientific Committee on Atrial Disorders, ESC ACVC Task Force on Digital Health, WG on Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases, WG on e-Cardiology, WG on Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Council on Stroke, and several other cardiology-related groups. She is also a regular member of the EAPCI, EAPC, and Romanian Society of Cardiology, where she serves as a Core leader for the Young Cardiologists of the Romanian Society of Cardiology. V.T. reports direct personal payments from the healthcare industry, including consultancy fees from Abbott, and payments for ECG-related activities from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. He has received payments for NOAC-related activities from Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Berlin Menarini. Additionally, V.T. has received fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme for pharmacological treatment of arrhythmias (beta blockers), Novartis for prevention of cardiac disease (unrelated to any specific product), AstraZeneca for SGLT2 inhibitors, and Medtronic for sudden cardiac death. In 2022, V.T. received speaker fees and honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim for Atrial Fibrillation (AF) and pharmacology and pharmacotherapy, Abbott for supraventricular tachycardia (non-AF), and Servier for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD). V.T. also received travel and meeting support from Johnson & Johnson for Atrial Fibrillation (AF) and AstraZeneca for chronic heart failure. In 2023, V.T. received payments, including speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy, advisory board fees, and travel funding for activities related to Atrial Fibrillation (AF) from Johnson & Johnson, chronic heart failure from Novartis and Pfizer, device therapy from Biotronik, and supraventricular tachycardia (non-AF) from Abbott. Funding for travel to and attendance at events unrelated to the listed activities was provided by Pfizer for chronic heart failure. D.K. reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR CDF-2015-08-074 RATE-AF; NIHR130280 DaRe2THINK; NIHR132974 D2T-NeuroVascular; and NIHR203326 Biomedical Research Centre), the British Heart Foundation (PG/17/55/33087, AA/18/2/34218, and FS/CDRF/21/21032), the EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative (BigData@Heart 116074), EU Horizon and UKRI (HYPERMARKER 101095480), UK National Health Service Data for R&D Subnational Secure Data Environment Programme, UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Regulators Pioneer Fund, the Cook and Wolstenholme Charitable Trust, and the European Society of Cardiology supported by educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim/BMS–Pfizer Alliance/Bayer/Daiichi Sankyo/Boston Scientific, the NIHR/University of Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and British Heart Foundation/University of Birmingham Accelerator Award (STEEER-AF). In addition, he has received research grants and advisory board fees in the past from Bayer, Amomed, and Protherics Medicines Development. I.C.V.G. reports payment for consultancy, advisory board fees, investigator, and committee member from Bayer (AF). I.C.V.G. is supported by unrestricted research grants from the Dutch Heart Foundation and Medtronic to the institution.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- 1. Cheng S, He J, Han Y, Han S, Li P, Liao H et al. Global burden of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021. Europace 2024;26:euae195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walli-Attaei M, Little M, Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray A, Torbica A, Maggioni AP et al. Health-related quality of life and healthcare costs of symptoms and cardiovascular disease events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a longitudinal analysis of 27 countries from the EURObservational Research Programme on Atrial Fibrillation general long-term registry. Europace 2024;26:euae146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mobley AR, Subramanian A, Champsi A, Wang X, Myles P, McGreavy P et al. Thromboembolic events and vascular dementia in patients with atrial fibrillation and low apparent stroke risk. Nat Med 2024;30:2288–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, Crijns HJGM et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024;45:3314–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandes A, Pedersen SS, Hendriks JM. A call for action to include psychosocial management into holistic, integrated care for patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2024;26:euae078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rienstra M, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Smit MD, Brügemann J et al. Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 trial. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:2050–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Wong CX et al. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: a long-term follow-up study (LEGACY). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Middeldorp ME, Pathak RK, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Elliott AD, Mahajan R et al. PREVEntion and regReSsive effect of weight-loss and risk factor modification on atrial fibrillation: the REVERSE-AF study. Europace 2018;20:1929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pinho-Gomes A-C, Azevedo L, Copland E, Canoy D, Nazarzadeh M, Ramakrishnan R et al. Blood pressure-lowering treatment for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation: an individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parkash R, Wells GA, Sapp JL, Healey JS, Tardif J-C, Greiss I et al. Effect of aggressive blood pressure control on the recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: a randomized, open-label clinical trial (SMAC-AF [Substrate Modification with Aggressive Blood Pressure Control]). Circulation 2017;135:1788–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olsson LG, Swedberg K, Ducharme A, Granger CB, Michelson EL, McMurray JJV et al. Atrial fibrillation and risk of clinical events in chronic heart failure with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results from the Candesartan in Heart failure-Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kotecha D, Holmes J, Krum H, Altman DG, Manzano L, Cleland JGF et al. Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2014;384:2235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zannad F, McMurray JJV, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pandey AK, Okaj I, Kaur H, Belley-Cote EP, Wang J, Oraii A et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors and atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e022222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, de Boer RA, DeMets D, Hernandez AF et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with HF with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: DELIVER trial. JACC Heart Fail 2022;10:184–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1451–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N Engl J Med 2021;384:117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R et al. Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with atrial fibrillation: the CARDIO-FIT study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:985–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hegbom F, Stavem K, Sire S, Heldal M, Orning OM, Gjesdal K. Effects of short-term exercise training on symptoms and quality of life in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2007;116:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Osbak PS, Mourier M, Kjaer A, Henriksen JH, Kofoed KF, Jensen GB. A randomized study of the effects of exercise training on patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2011;162:1080–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malmo V, Nes BM, Amundsen BH, Tjonna A-E, Stoylen A, Rossvoll O et al. Aerobic interval training reduces the burden of atrial fibrillation in the short term: a randomized trial. Circulation 2016;133:466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oesterle A, Giancaterino S, Van Noord MG, Pellegrini CN, Fan D, Srivatsa UN et al. Effects of supervised exercise training on atrial fibrillation: a META-ANALYSIS OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2022;42:258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elliott AD, Verdicchio CV, Mahajan R, Middeldorp ME, Gallagher C, Mishima RS et al. An exercise and physical activity program in patients with atrial fibrillation: the ACTIVE-AF randomized controlled trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2023;9:455–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Voskoboinik A, Kalman JM, De Silva A, Nicholls T, Costello B, Nanayakkara S et al. Alcohol abstinence in drinkers with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2020;382:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holmqvist F, Guan N, Zhu Z, Kowey PR, Allen LA, Fonarow GC et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy on outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation-results from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF). Am Heart J 2015;169:647–54.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, Haffajee CI, Das S, Kumar K et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li L, Wang Z-W, Li J, Ge X, Guo L-Z, Wasng Y et al. Efficacy of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea with and without continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Europace 2014;16:1309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naruse Y, Hiroshi T, Makoto S, Mariko Y, Hidekazu T, Yumi H et al. Concomitant obstructive sleep apnea increases the recurrence of atrial fibrillation following radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: clinical impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Heart rhythm Heart Rhythm 2013;10:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albert CM, Cook NR, Pester J, Moorthy MV, Ridge C, Danik JS et al. Effect of marine omega-3 fatty acid and vitamin D supplementation on incident atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Qureshi WT, Nasir UB, Alqalyoobi S, O’Neal WT, Mawri S, Sabbagh S et al. Meta-analysis of continuous positive airway pressure as a therapy of atrial fibrillation in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1767–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shukla A, Aizer A, Holmes D, Fowler S, Park DS, Bernstein S et al. Effect of obstructive sleep apnea treatment on atrial fibrillation recurrence: a meta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2015;1:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nalliah CJ, Wong GR, Lee G, Voskoboinik A, Kee K, Goldin J et al. Impact of CPAP on the atrial fibrillation substrate in obstructive sleep apnea: the SLEEP-AF study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022;8:869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Friberg L, Hammar N, Rosenqvist M. Stroke in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: report from the Stockholm Cohort of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:967–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Banerjee A, Taillandier S, Olesen JB, Lane DA, Lallemand B, Lip GYH et al. Pattern of atrial fibrillation and risk of outcomes: the Loire Valley Atrial Fibrillation Project. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:2682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke 1991;22:983–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener H-C, Hart R, Golitsyn S et al. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:806–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Själander S, Själander A, Svensson PJ, Friberg L. Atrial fibrillation patients do not benefit from acetylsalicylic acid. Europace 2014;16:631–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tomasdottir M, Friberg L, Hijazi Z, Lindbäck J, Oldgren J. Risk of ischemic stroke and utility of CHA2 DS2-VASc score in women and men with atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol 2019;42:1003–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu VC-C, Wu M, Aboyans V, Chang S-H, Chen S-W, Chen M-C et al. Female sex as a risk factor for ischaemic stroke varies with age in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2020;106:534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mikkelsen AP, Lindhardsen J, Lip GYH, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Olesen JB. Female sex as a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:1745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Champsi A, Mobley AR, Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Wang X, Shukla D et al. Gender and contemporary risk of adverse events in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2024;45:3707–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cappato R, Ezekowitz MD, Klein AL, Camm AJ, Ma C-S, Le Heuzey J-Y et al. Rivaroxaban vs. vitamin K antagonists for cardioversion in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Goette A, Merino JL, Ezekowitz MD, Zamoryakhin D, Melino M, Jin J et al. Edoxaban versus enoxaparin-warfarin in patients undergoing cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (ENSURE-AF): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2016;388:1995–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brunetti ND, Tarantino N, De Gennaro L, Correale M, Santoro F, Di Biase M. Direct oral anti-coagulants compared to vitamin-K antagonists in cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2018;45:550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Steinberg JS, Sadaniantz A, Kron J, Krahn A, Denny DM, Daubert J et al. Analysis of cause-specific mortality in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Circulation 2004;109:1973–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sgreccia D, Manicardi M, Malavasi VL, Vitolo M, Valenti AC, Proietti M et al. Comparing outcomes in asymptomatic and symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 81,462 patients. J Clin Med 2021;10:3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Camen S, Ojeda FM, Niiranen T, Gianfagna F, Vishram-Nielsen JK, Costanzo S et al. Temporal relations between atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke and their prognostic impact on mortality. Europace 2020;22:522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brambatti M, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Morillo CA, Capucci A, Muto C et al. Temporal relationship between subclinical atrial fibrillation and embolic events. Circulation 2014;129:2094–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chao T-F, Lip GYH, Liu C-J, Lin Y-J, Chang S-L, Lo L-W et al. Relationship of aging and incident comorbidities to stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:122–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weijs B, Dudink EAMP, de Vos CB, Limantoro I, Tieleman RG, Pisters R et al. Idiopathic atrial fibrillation patients rapidly outgrow their low thromboembolic risk: a 10-year follow-up study. Neth Heart J 2019;27:487–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bezabhe WM, Bereznicki LR, Radford J, Wimmer BC, Salahudeen MS, Garrahy E et al. Stroke risk reassessment and oral anticoagulant initiation in primary care patients with atrial fibrillation: a ten-year follow-up. Eur J Clin Invest 2021;51:e13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fauchier L, Bodin A, Bisson A, Herbert J, Spiesser P, Clementy N et al. Incident comorbidities, aging and the risk of stroke in 608,108 patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide analysis. J Clin Med 2020;9:1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seiffge DJ, De Marchis GM, Koga M, Paciaroni M, Wilson D, Cappellari M et al. Ischemic stroke despite oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol 2020;87:677–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Senoo K, Lip GYH, Lane DA, Büller HR, Kotecha D. Residual risk of stroke and death in anticoagulated patients according to the type of atrial fibrillation: AMADEUS trial. Stroke 2015;46:2523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Meinel TR, Branca M, De Marchis GM, Nedeltchev K, Kahles T, Bonati L et al. Prior anticoagulation in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol 2021;89:42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Polymeris AA, Meinel TR, Oehler H, Hölscher K, Zietz A, Scheitz JF et al. Aetiology, secondary prevention strategies and outcomes of ischaemic stroke despite oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022;93:588–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Paciaroni M, Caso V, Agnelli G, Mosconi MG, Giustozzi M, Seiffge DJ et al. Recurrent ischemic stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation who suffered an acute stroke while on treatment with nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: the RENO-EXTEND study. Stroke 2022;53:2620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yao X, Shah ND, Sangaralingham LR, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant dosing in patients with atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:2779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Steinberg BA, Shrader P, Thomas L, Ansell J, Fonarow GC, Gersh BJ et al. Off-label dosing of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and adverse outcomes: the ORBIT-AF II registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Alexander JH, Andersson U, Lopes RD, Hijazi Z, Hohnloser SH, Ezekowitz JA et al. Apixaban 5mg twice daily and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced age, low body weight, or high creatinine: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:673–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Guenoun M, Cohen S, Villaceque M, Sharareh A, Schwartz J, Hoffman O et al. Characteristics of patients with atrial fibrillation treated with direct oral anticoagulants and new insights into inappropriate dosing: results from the French National Prospective Registry: PAFF. Europace 2023;25:euad302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Whitlock RP, Belley-Cote EP, Paparella D, Healey JS, Brady K, Sharma M et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion during cardiac surgery to prevent stroke. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lakkireddy D, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Windecker S, Thaler D, Price MJ, Gambhir A et al. Mechanisms, predictors, and evolution of severe peri-device leaks with two different left atrial appendage occluders. Europace 2023;25:euad237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Caliskan E, Sahin A, Yilmaz M, Seifert B, Hinzpeter R, Alkadhi H et al. Epicardial left atrial appendage AtriClip occlusion reduces the incidence of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery. Europace 2018;20:e105–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nso N, Nassar M, Zirkiyeva M, Lakhdar S, Shaukat T, Guzman L et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery with left atrial appendage occlusion versus no occlusion, direct oral anticoagulants, and vitamin K antagonists: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022;40:100998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ibrahim AM, Tandan N, Koester C, Al-Akchar M, Bhandari B, Botchway A et al. Meta-analysis evaluating outcomes of surgical left atrial appendage occlusion during cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2019;124:1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Park-Hansen J, Holme SJV, Irmukhamedov A, Carranza CL, Greve AM, Al-Farra G et al. Adding left atrial appendage closure to open heart surgery provides protection from ischemic brain injury six years after surgery independently of atrial fibrillation history: the LAACS randomized study. J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;13:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Soltesz EG, Dewan KC, Anderson LH, Ferguson MA, Gillinov AM. Improved outcomes in CABG patients with atrial fibrillation associated with surgical left atrial appendage exclusion. J Card Surg 2021;36:1201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. van Laar C, Verberkmoes NJ, van Es HW, Lewalter T, Dunnington G, Stark S et al. Thoracoscopic left atrial appendage clipping: a multicenter cohort analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Aarnink EW, Ince H, Kische S, Pokushalov E, Schmitz T, Schmidt B et al. Incidence and predictors of 2-year mortality following percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion in the EWOLUTION trial. Europace 2024;26:euae188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Boersma L, Andrade JG, Betts T, Duytschaever M, Pürerfellner H, Santoro F et al. Progress in atrial fibrillation ablation during 25 years of Europace journal. Europace 2023;25:euad244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, De Paola A, Marchlinski F, Natale A et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jaïs P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, Daoud E, Khairy P, Subbiah R et al. Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study. Circulation 2008;118:2498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Poole JE, Bahnson TD, Monahan KH, Johnson G, Rostami H, Silverstein AP et al. Recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic drug therapy in the CABANA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:3105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mont L, Bisbal F, Hernández-Madrid A, Pérez-Castellano N, Viñolas X, Arenal A et al. Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation: a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (SARA study). Eur Heart J 2014;35:501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wazni OM, Dandamudi G, Sood N, Hoyt R, Tyler J, Durrani S et al. Cryoballoon ablation as initial therapy for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2021;384:316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Andrade JG, Wells GA, Deyell MW, Bennett M, Essebag V, Champagne J et al. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2021;384:305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kuniss M, Pavlovic N, Velagic V, Hermida JS, Healey S, Arena G et al. Cryoballoon ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drugs: first-line therapy for patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace 2021;23:1033–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cosedis Nielsen J, Johannessen A, Raatikainen P, Hindricks G, Walfridsson H, Kongstad O et al. Radiofrequency ablation as initial therapy in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1587–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Morillo CA, Verma A, Connolly SJ, Kuck KH, Nair GM, Champagne J et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (RAAFT-2): a randomized trial. JAMA 2014;311:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, Verma A, Bhargava M, Saliba W et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:2634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chen S, Pürerfellner H, Ouyang F, Kiuchi MG, Meyer C, Martinek M et al. Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drugs as ‘first-line’ initial therapy for atrial fibrillation: a pooled analysis of randomized data. Europace 2021;23:1950–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Noujaim C, Assaf A, Lim C, Feng H, Younes H, Mekhael M et al. Comprehensive atrial fibrillation burden and symptom reduction post-ablation: insights from DECAAF II. Europace 2024;26:euae104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Serban T, Mannhart D, Abid Q-U-A, Höchli A, Lazar S, Krisai P et al. Durability of pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Europace 2023;25:euad335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Schmidt B, Bordignon S, Neven K, Reichlin T, Blaauw Y, Hansen J et al. EUropean real-world outcomes with Pulsed field ablatiOn in patients with symptomatic atRIAl fibrillation: lessons from the multi-centre EU-PORIA registry. Europace 2023;25:euad185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Simantirakis EN, Papakonstantinou PE, Kanoupakis E, Chlouverakis GI, Tzeis S, Vardas PE. Recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation after the first clinical episode: a prospective evaluation using continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring. Clin Cardiol 2018;41:594–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Linz D, Andrade JG, Arbelo E, Boriani G, Breithardt G, Camm AJ et al. Longer and better lives for patients with atrial fibrillation: the 9th AFNET/EHRA consensus conference. Europace 2024;26:euae070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Schnabel RB, Marinelli EA, Arbelo E, Boriani G, Boveda S, Buckley CM et al. Early diagnosis and better rhythm management to improve outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: the 8th AFNET/EHRA consensus conference. Europace 2023;25:6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Rillig A, Eckardt L, Borof K, Camm AJ, Crijns HJGM, Goette A et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term sodium channel blocker therapy for early rhythm control: the EAST-AFNET 4 trial. Europace 2024;26:euae121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A et al. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hunter RJ, Berriman TJ, Diab I, Kamdar R, Richmond L, Baker V et al. A randomized controlled trial of catheter ablation versus medical treatment of atrial fibrillation in heart failure (the CAMTAF trial). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sugumar H, Prabhu S, Costello B, Chieng D, Azzopardi S, Voskoboinik A et al. Catheter ablation versus medication in atrial fibrillation and systolic dysfunction: late outcomes of CAMERA-MRI study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2020;6:1721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Tzeis S, Gerstenfeld EP, Kalman J, Saad EB, Sepehri Shamloo A, Andrade JG et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2024;26:euae043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chen S, Pürerfellner H, Meyer C, Acou W-J, Schratter A, Ling Z et al. Rhythm control for patients with atrial fibrillation complicated with heart failure in the contemporary era of catheter ablation: a stratified pooled analysis of randomized data. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens L et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sohns C, Fox H, Marrouche NF, Crijns HJGM, Costard-Jaeckle A, Bergau L et al. Catheter ablation in end-stage heart failure with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1380–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]