Abstract

Objective

To investigate delays in the presentation to hospital and evaluation of patients with suspected stroke.

Design

Multicentre prospective observational study.

Setting

22 hospitals in the United Kingdom and Dublin.

Participants

739 patients with suspected stroke presenting to hospital.

Main outcome measures

Time from onset of stroke symptoms to arrival at hospital, and time from arrival to evaluation by a senior doctor.

Results

The median age of patients was 75 years, and 400 were women. The median delay between onset of symptoms and arrival at hospital was 6 hours (interquartile range 1 hour 48 minutes to 19 hours 12 minutes). 37% of patients arrived within 3 hours, 50% within 6 hours. The median delay for patients using the emergency service was 2 hours 3 minutes (47 minutes to 7 hours 12 minutes) compared with 7 hours 12 minutes (2 hours 5 minutes to 20 hours 37 minutes) for referrals from general practitioners (P<0.0001). Use of emergency services reduced delays to hospital (odds ratio 0.45, 95% confidence interval 0.23 to 0.61). The median time to evaluation by a senior doctor was 1 hour 9 minutes (interquartile range 33 minutes to 1 hour 50 minutes) but was undertaken in only 477 (65%) patients within 3 hours of arrival. This was not influenced by age, sex, time of presentation, mode of referral, hospital type, or the presence of a stroke unit. Computed tomography was requested within 3 hours of arrival in 166 (22%) patients but undertaken in only 60 (8%).

Conclusion

Delays in patients arriving at hospital with suspected stroke can be reduced by the increased use of emergency services. Over a third of patients arrive at hospital within three hours of stroke; their management can be improved by expediting medical evaluation and performing computed tomography early.

What is already known on this topic

Delay in presentation and assessment of patients with suspected stroke prevents the possible benefits from thrombolysis being achieved

Little is known about the presentation and early management of patients with acute stroke in the United Kingdom

What this study adds

Most patients with suspected stroke in the United Kingdom arrive at hospital within six hours of the onset of symptoms

Not all patients are evaluated by a senior doctor within three hours of arrival at hospital and most do not undergo computed tomography

The potential for thrombolysis in patients with acute stroke can be improved significantly by greater use of emergency services and expediting evaluation and investigations by doctors

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and long term disability and is associated with high costs.1,2 Recent studies show that thrombolysis is an effective treatment in selected patients but needs to be undertaken within three hours and no later than six hours from the onset of symptoms.3–6 Most guidelines emphasise the rapid assessment of patients with suspected stroke,7 but this is not the case for most patients.8–10 Studies in the United States have shown that underutilisation of emergency medical services and delays in hospital assessment are important impediments to thrombolysis,11–19 which can be modified readily to improve the care of stroke.11–13

The uptake of thrombolysis has been more cautious in the United Kingdom than it has in North America and western Europe for two reasons.20,21 Firstly, because meta-analysis of studies does not support the widespread use of thrombolytic therapy in the routine practice of stroke management in that benefit is marginal and mortality may be increased,5 and secondly, because of the perception that most patients present too late to be eligible for treatment.22,23 Factors associated with the late presentation of stroke have been investigated in single centre studies in Britain,23,24 but the results may not be generalisable, and findings of large studies in the United States and Europe may not be applicable because of differences in healthcare systems. We aimed to investigate delays in the presentation to hospital and evaluation of patients with stroke in the United Kingdom and to identify measures that could improve their early management.

Participants and methods

Setting and patients

The study was conducted in 11 teaching hospitals and 11 district general hospitals in the United Kingdom and Dublin. Six teaching hospitals and five general district hospitals had a stroke unit. Thrombolysis was offered routinely at one hospital and as part of research at three hospitals.

Consecutive patients with signs or symptoms suggestive of an acute stroke were included over a specified four week period. Most patients presented to an emergency department, but when hospitals lacked such a service patients were seen in acute assessment units. Patients who were already admitted to hospital at the time of onset of stroke symptoms were excluded. Investigators were limited to a maximum enrolment of 40 patients at each site to maximise geographical diversity.

Data collection

Data at each hospital were collected by independent observers who were given formal training and standardised instructions on definitions and data collection techniques. The observers were alerted by triage staff on arrival of a patient with suspected stroke, regardless of time of day. They monitored patient management for the first three hours after arrival by using a structured format of prespecified variables considered to be important in stroke management. Clinical staff were not aware of the purpose of data collection or of the specific variables being monitored.

Time from onset of symptoms and time of arrival at hospital were recorded. The onset of stroke was defined as the time neurological deficit was first noticed by the patient or an observer. If symptoms were present on awakening, the onset of stroke was considered to be the time the patient fell asleep. For patients in whom time of onset was not documented, midnight on the day of onset was considered the onset time. The timing of various assessments and investigations (including computed tomography) after arrival at hospital was recorded. Delay to evaluation by a senior doctor was defined as the interval between the arrival time and evaluation by a doctor (senior house officer or a higher grade doctor on the admitting medical team) empowered to take decisions on specialist investigations and management. Information on the modes of referral was collected. These were classified as a 999 ambulance call by the patient or a relative (emergency services), a non-emergency referral by a general practitioner, a 999 ambulance call by a general practitioner (general practitioner plus 999), or other methods including arrival on own or by public transport.

Statistical analyses

All data were scrutinised at a local level and verified against source records for completeness and accuracy. Data for individual centres were anonymised before analysis to ensure confidentiality and to prevent bias. Analysis was undertaken on an intention to treat basis and included all patients irrespective of final diagnosis. Median values with interquartile range were reported because of the skewed distribution of data.

Two principal sets of time intervals were of major interest; time from onset of signs or symptoms of stroke to arrival at hospital and time from arrival at hospital to evaluation by a senior doctor. Logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the effect of patient characteristics, time of onset, mode of referral, and hospital characteristics on the likelihood of delay in arrival after the onset of stroke. A similar model was constructed for delays in evaluation by a senior doctor. Patients with missing data for any of the variables were excluded from the analyses. We conducted a forward stepwise logistic regression model at a significance level of 0.2 for variable entry into the model. We presented the results of this analysis as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 739 patients were studied. The median age of patients was 75 years, with the largest proportion of patients being between 65 and 85 years (table 1). Time of onset for most of the patients with suspected stroke (62%) was between 6 am and 6 pm. The time could not be accurately determined for patients who had a stroke during sleep; the definition for onset in these patients was probably responsible for the relatively high proportion of strokes reported between 6 pm and midnight and the relatively low proportion reported between midnight and 6 am. The most common type of stroke was ischaemic, accounting for 505 of the 565 (89%) patients with stroke in the sample. Acute stroke was not the final diagnosis in nearly one in five patients suspected with a stroke on presentation (table 1). Diagnoses in these patients ranged from old stroke with an acute infective or metabolic disturbance to other neurological disease (for example, acute confusion states, space occupying lesions) and non-neurological disorders (for example, infections, metabolic or metastatic disease). No significant differences were found between hospitals for patient characteristics, time of onset of symptoms, time of presentation, and the final diagnosis.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of 739 patients with suspected stroke

| Attribute

|

No (%) of patients

|

|---|---|

| Median age (years; n=737): | 75* |

| <55 | 80 (11) |

| 55-64 | 96 (13) |

| 65-74 | 192 (26) |

| 75-84 | 255 (36) |

| ⩾85 | 114 (15) |

| Women (n=737) | 400 (54) |

| Documented time of onset (n=646): | |

| 00 00 to 05 59 | 59 (9) |

| 06 00 to 11 59 | 242 (37) |

| 12 00 to 17 59 | 164 (25) |

| 18 00 to 23 59 | 181 (28) |

| Time of arrival at hospital (n=736): | |

| 00 00 to 05 59 | 40 (5) |

| 06 00 to 11 59 | 214 (29) |

| 12 00 to 17 59 | 314(43) |

| 18 00 to 23 59 | 168 (23) |

| Mode of referral (n=736): | |

| Emergency services | 320 (43) |

| General practitioner referrals | 330 (45) |

| General practitioner referral plus emergency services | 36 (5) |

| Others | 50 (7) |

| Final diagnosis (n=739): | |

| Acute ischaemic stroke | 405 (55) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 100 (14) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 49 (7) |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 11 (1.5) |

| Others | 156 (21) |

| Not established | 18 (2.5) |

Interquartile range 66-82.

Presentation to hospital

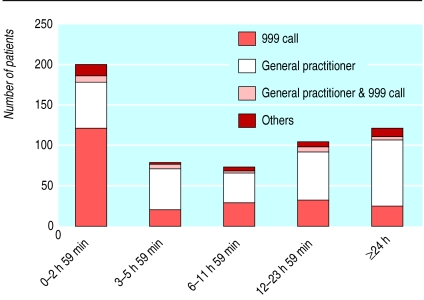

Most patients (95%) arrived at the hospital between 6 am and midnight, regardless of the time of onset of symptoms or mode of referral (table 1). The median delay between onset of symptoms and arrival at the hospital was six hours (interquartile range 1 hour 48 minutes to 19 hours 12 minutes). More than a third of the patients had arrived at hospital within three hours and nearly half within six hours of the onset of symptoms (table 2). No differences were found in the delay from onset of symptoms to arrival at hospital between patients with a final diagnosis of stroke or transient ischaemic attack from those with other diagnoses. The proportion of patients in different age groups did not vary significantly within different time intervals suggesting that older (⩾75 years) patients were as likely to present to hospital early as younger patients. Overall, 43% (320 patients) of patients were brought by ambulance to the hospital after a 999 call to the emergency services by the patient or a relative (table 1). A similar proportion (45%) of patients consulted their general practitioner and were referred to hospital as non-urgent admissions. Overall, 81% (56 of 69) of the patients who arrived at hospital within an hour of the onset of symptoms were brought in by the emergency services compared with 7% (5 of 69) who first saw their general practitioner (figure). The median time between the onset of stroke and arrival at hospital for patients using the emergency service was 2 hours and 3 minutes (47 minutes to 7 hours and 12 minutes), which was significantly less than the 7 hours and 12 minutes (2 hours 5 minutes to 20 hours 37 minutes) for patients who first saw their general practitioner (P<0.0001). General practitioners used the emergency services for only 36 (5%) patients, in whom the median delay between onset of symptoms and presentation was 3 hours 47 minutes (2 hours 33 minutes to 6 hours 54 minutes).

Table 2.

Overall delay times. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Interval

|

Results

|

|---|---|

| Onset of symptoms to arrival (n=729) | |

| Median time (interquartile range) | 6 h (1 h 48 min to 19 h 12 min) |

| Time interval: | |

| 0 to 2 h 59 min | 271 (37) |

| 3 to 5 h 59 min | 93 (13) |

| 6 to 11 h 59 min | 85 (12) |

| ⩾12 h | 280 (38) |

| Arrival to initial assessment by emergency doctor (n=736) | |

| Median time (interquartile range) | 37 min (16 min to 1 h 12 min)* |

| Time interval: | |

| 0-15 min | 163 (22) |

| 16-30 min | 121 (16) |

| 31-45 min | 113 (15) |

| 46-60 min | 82 (11) |

| 61-120 min | 151 (20) |

| 121-179 min | 50 (7) |

| ⩾180 min | 56 (8) |

| Arrival to assessment by senior doctor (n=736) | |

| Median time (interquartile range) | 1 h 9 min (33 min to 1 h 50 min)* |

| Time interval: | |

| 0-15 min | 65 (9) |

| 16-30 min | 37 (5) |

| 31-60 min | 121 (16) |

| 61-120 min | 156 (21) |

| 121-179 min | 98 (13) |

| ⩾180 min | 259 (35) |

Median in 485 patients who arrived at emergency department within three hours of onset of stroke.

Factors associated with delays greater than 6 hours between onset of symptoms and arrival at hospital were time of onset between midnight and 6 am (odds ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 1.04 to 1.45) and admission to a teaching hospital (1.09, 1.01 to 1.54). Emergency services requested by the patient or a relative were associated with a significantly shorter delay to admission (0.45, 0.23 to 0.61). Delays in presentation were not affected by age, sex, final diagnosis of ischaemic stroke, or the existence of a stroke unit.

Early assessment in hospital

A nurse recorded heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, and glucose concentrations in 634 (86%) patients within 15 minutes of arrival at hospital and in 688 (93%) patients within 30 minutes of arrival. In contrast, only 163 of 736 (22%) patients were seen within 15 minutes of arrival by a doctor from an emergency or assessment unit and 284 (38%) within 30 minutes of arrival (table 2). Evaluation by a senior doctor from the admitting medical team was undertaken in 477 (65%) patients within 3 hours of arrival at hospital. Of these patients, 26 (5%) were seen by a consultant, 115 (24%) by a specialist registrar, and 336 (70%) by a senior house officer. Computed tomography within 3 hours of arrival was requested in 166 (22%) patients but was undertaken in only 60 (8%). The interval between presentation to hospital and assessment by a senior doctor was not influenced by the age or sex of the patient, time of presentation, final stroke diagnosis, mode of referral, initial assessment by a doctor, academic status of hospital, or the presence of a stroke unit.

Discussion

Around 37% of patients with suspected stroke present to hospital within three hours of the onset of symptoms and 50% within six hours of the onset of symptoms, similar to that reported in US studies.8–14 Therefore thrombolysis may be a realistic option in the United Kingdom. In keeping with US reports, early presentation was not influenced by age or sex but was significantly reduced by activating emergency services.11,13,14 Although teaching hospitals were associated with greater delays in presentation, this may reflect their location within an inner city and associated factors of education, social deprivation, and traffic congestion.

The study identified considerable delays in assessment of patients after arrival at hospital. Some of the delays in assessment may have resulted from the knowledge that the patient was stable after assessment by nursing staff (hence low priority) and compounded by the absence of established protocols for intervention for acute stroke in most hospitals. These factors may also be responsible for the low rate of early computed tomography; scanning was requested in less than a quarter of patients and undertaken in less than 10% within three hours of arrival. The existence of a stroke unit did not result in more patients being assessed early or the uptake of more computed tomography. However, all the hospitals had stroke specialists and probably provided better stroke services than the UK average.

The study is representative because it covered geographically diverse areas and included unselected patients with suspected stroke. The distribution of age and sex of patients was consistent with stroke registry data from other sources, suggesting that sampling was not biased.25 Clinical staff were not informed of the objectives or measures of the study, and independent assessors were used to reduce observer bias. Although the potential for measurement bias in time of onset of symptoms existed, this was unlikely to be significant because of the consistency of results between hospitals and comparability with previous studies.8–14 The study was designed to be simple for accuracy and reliability, and data were not collected on education specific to stroke in patients, family members, or healthcare professionals. These factors are likely to influence both the time to presentation to hospital as well as delays in assessment at hospital.

The study highlights the needs of service development to improve the management of acute stroke. Efforts should be made at all levels (patient, ambulance services, general practitioners) to encourage the use of emergency services as the most direct means of reducing delays in getting to hospital and increasing the number of patients eligible for therapies. That nearly one in five patients with suspected stroke have non-stroke diagnoses emphasises the importance of early evaluation by a specialist and early involvement of specialist stroke services. Most importantly, the perception that delays in presentation prevent early specialist management of stroke in the United Kingdom is not justified, and there is a good case for bringing stroke practice in line with other developed countries.26

Figure.

Number of patients arriving within each time interval by mode of referral

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff who collected data and J M Gregson for contributions in the initial phases of the study. The Acute Stroke Intervention Study Group consisted of: R Dijkhuizen (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary), D O'Neill (Adelaide and Meath Hospitals, Dublin), K Fullerton (Belfast City Hospital), P Syme (Borders General Hospital, Melrose), D Jenkinson (Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch), B Chapman (Edinburgh Royal Infirmary), N Baldwin (Gloucestershire Royal Hospital), P Tyrrell (Hope Hospital, Salford), L Kalra (King's College Hospital, London), T Robinson (Leicester Hospital), M Wani (Morriston Hospital, Swansea) R MacWalter (Ninewells Hospital, Dundee), S Ellis (North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary, Stoke on Trent), R Curless (North Tyneside General Hospital, Newcastle), J Horsley (Ormskirk District General Hospital), C Jack (Royal Liverpool Hospital), M M Brown (St George's Hospital, London), C S Gray (Sunderland Royal Hospital), M Power (Ulster Hospital, Dundonald), A K Sharma (University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool), K R Lees (Western Infirmary, Glasgow), and D G Smithard (William Harvey Hospital, Ashford, Kent).

Footnotes

Funding: This project was supported by an unrestricted grant from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Competing interests: LK and MMB have been reimbursed by Boehringer Ingelheim to attend conferences. AKS and KRL have been reimbursed by Boehringer Ingelheim to attend conferences and to give lectures. RIV is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. None of the authors stand to gain financially from publication.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart and stroke statistical update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hankey GJ, Warlow CP. Treatment and secondary prevention of stroke: evidence, costs and effects on individuals and populations. Lancet. 1999;354:1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grotta JC. Acute stroke therapy in the millennium: consummating the marriage between the laboratory and the bedside: the Feinberg lecture. Stroke. 1999;30:1722–1728. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bath PM, Lees KR. ABC of arterial and venous disease: acute stroke. BMJ. 2000;320:920–923. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wardlaw JM, del Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T. Cochrane Library. Issue 1. Oxford: Update software; 2000. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lees KR. Thrombolysis. Brit Med Bull 2000;389-400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, Jagoda A, Marler JR, Mayberg MR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers. JAMA. 2000;283:3102–3109. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MA, Doliszny KM, Shahar E, McGovern PG, Arnett DK, Luepker RV. Delayed hospital arrival for acute stroke: the Minnesota stroke survey. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:190–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzan IL, Furlan AJ, Way LE, Farnk JI, Harper DL, Hinchey JA, et al. A systematic audit of iv tPA in Cleveland area hospitals. Stroke. 1999;30:266. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenson K, Rosamond W, Morris D. Prehospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke care. Neuroepidemiology. 2001;20:65–76. doi: 10.1159/000054763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacy C, Suh D, Bueno M, Kostis J.for the STROKE Collaborative Study Group. Delay in presentation and evaluation for acute stroke: Stroke Time Registry for Outcomes Knowledge and Epidemiology (STROKE) Stroke 20013263–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder E, Rosamond W, Morris D, Evenson K, Hinn A. Determinants of emergency medical services use in a population with stroke symptoms: the Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Stroke. 2000;31:2591–2596. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S. Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke. The Genentech Stroke Presentation Survey. Stroke. 2000;31:2585. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kothari R, Jauch E, Broderick J, Brott T, Sauerbeck L, Khoury J, et al. Acute stroke: delays to presentation and emergency department evaluation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosamond W, Gorton R, Hinn A, Hohenhaus S, Morris D. Rapid response to stroke symptoms: the Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH) Study. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menon SC, Pandey DK, Morganstern LB. Critical factors in determining access to acute stroke care. Neurology. 1998;51:427–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wester P, Radberg J, Lundgren B, Peltonen M.for the Seek-Medical-Attention-in-Time Study Group. Factors associated with delay admission to hospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke and TIA Stroke 19993040–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris D, Rosamond W, Hinn A, Gorton R. Time delays in accessing stroke care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bratina P, Greenberg L, Pasteur W, Grotta J. Current emergency department management of stroke in Houston, Texas. Stroke. 1995;26:409–414. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intercollegiate Working Party on Stroke. National clinical guidelines on stroke. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coronary Heart Disease/Stroke Task Force report. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barer D, Main A, Lodwick R. Practicability of early treatment of acute stroke. Lancet. 1992;339:1540–1541. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91306-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harper GD, Haigh RA, Potter JF, Castleden CM. Factors delaying hospital admission after stroke in Leicestershire. Stroke. 1992;23:835–838. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salisbury HR, Banks BJ, Footitt DR, Winner SJ, Reynolds DJM. Delay in presentation of patients with acute stroke to hospital in Oxford. Q J Med. 1998;91:635–640. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.9.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, Warlow C. A prospective study of acute cerebrovascular disease in the community: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. II. Incidence, case fatality rates and overall outcome at one year of cerebral infarction, primary intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:16–22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hacke W. A late step in the right direction for stroke care. Lancet. 2000;356:869–870. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]