Abstract

Uteri from women undergoing chemoradiotherapy (CRT) may show reactive atypia which may mimic serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC). We aimed to assess the prevalence and morphological/immunohistochemical features of post-radiotherapy serous-like endometrial changes (PoRSEC) in women undergone CRT for locally advanced cervical cancer, with a focus on the differential diagnosis with SEIC. Consecutive patients with locally advanced cervical cancer undergone CRT between 2011 and 2018 were reviewed. Endometrial histological specimens were assessed for the presence of PoRSEC. Twenty-two cases of SEIC were included for comparison. Immunohistochemistry for p53, p16, and Ki67 was performed. Out of 244 reviewed patients, 36 (14.7%) showed PoRSEC. The degree of nuclear atypia was similar between PoRSECs and SEIC. However, a papillary architecture with areas of confluent papillae was only observed in SEIC. SEIC cases showed a high mitotic activity as opposed to PoRSEC cases. The expression of p53 was aberrant in all SEICs but in none of the PoRSECs; however, 13/36 PoRSECs showed p53 positivity in most tumor cells, potentially mimicking a mutation pattern. A block-type p16 expression was observed in all SEICs and in 16/36 PoRSECs. Mean Ki67 expression was 26.9% in SEIC (range 5–70%) and 8.16% in PoRSEC (range 5–35%). While SEIC showed sharp morphological and immunohistochemical demarcation, PoRSEC were more heterogenous and merged imperceptibly with normal endometrium. In conclusion, PoRSEC may mimic SEIC both morphologically and immunohistochemically. However, a papillary architecture with cytological demarcation is typically observed in SEIC but not in PoRSEC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00428-024-03818-4.

Keywords: Serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC), Post-radiotherapy endometrial change, p53, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

With the increasing use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) plus brachytherapy as a standard of care in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma (LACC, stage IB2-IVA, FIGO staging classification, 2018) [1], the recognition of radiation-associated histological changes has become mandatory. Endocervical histological changes after radiotherapy have been reported. Indeed, endocervical cells could appear enlarged; with an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio, the cytoplasm could be eosinophilic or finely vacuolated and the nuclei could loss polarity and show prominent eosinophilic nucleoli [2]. CRT-related changes can also be observed in endometrial epithelial cells; these changes should be considered when assessing endometria undergone CRT-related as they could mimic serous intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC). However, to the best of our knowledge, these changes have only been described in case reports or small case series [3, 4]. Moreover, the differential diagnosis between CRT-related endometrial changes and SEIC has never been systematically assessed.

On this account, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence, morphological features, and immunophenotype of post-radiotherapy serous-like endometrial changes (PoRSEC) and the differential diagnosis with SEIC.

Materials and methods

The study has been approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB) n° IST DIPUSVSP-17–05-2134, and it complied with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

All consecutive hysterectomy specimens (n. 244) of patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma (LACC) managed by CT/RT plus brachytherapy followed by surgery at the Gynecologic Oncology Unit and Radiotherapy of the Catholic University in Rome (Italy), from January 2011 to December 2018, were included. PoRSEC was defined as the presence of an endometrial gland with an epithelium showing the following features: hobnail cells, clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, and presence of nucleoli.

Twenty-two cases of SEIC were used to compare morphological and immunohistochemical features.

All cases were reviewed by four pathologists with expertise in gynecological pathology (G.F.Z., D.A., G.S., N.D.A., and A.T.).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to previously described methods [5] and involved p53 antibodies (clone Do-7), p16 (clone 6H12) (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), Ki67 (clone 30–9), Napsin A (clone MRQ-60, Roche Ventana), and p504s (clone 13H4, Dako).

Immunohistochemistry expressions were categorized according to previously described methods [5, 6]; in particular, p53 was defined as “aberrant” (moderate-to-strong positivity in > 80% of cells or complete absence or cytoplasmic), “wild-type (wt)-high” (positivity in 50–80% of cells with variable intensity), “wt-intermediate” (positivity in 5–50% of cells), and “wt-low” (positivity in < 5% of cells).

Ki67 was reported as the percentage of epithelial cells showing any nuclear staining.

P16 was defined as positive block-type if it showed a “strong and diffuse” nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, diffuse patchy if more than 50% of the cells were positive, low-patchy expression if the positive cells were 5–50%, and absent if < 5%.

The expression of the Napsin A and p504s was defined as negative, focal, and diffuse.

Results

Morphology

Among 244 reviewed uteri, PoRSECs were observed in 36 (14.7%) cases.

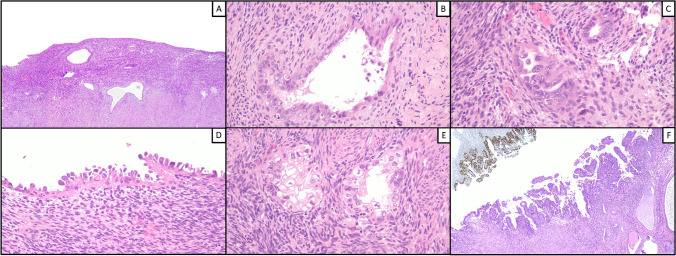

Cell morphology was similar between PoRSEC and SEIC, as both showed nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia with occasional nucleoli, frequent hobnail cells, and eosinophilic cytoplasm, sometimes with clarification. Regarding architecture, neither SEIC nor PoRSEC showed branching papillae or prominent glandular crowding; however, unlike PoRSECs, SEICs were at least focally characterized by simple papillae with areas of confluence. An evident mitotic activity was noted in SEIC cases but not in PoRSEC cases. A widespread involvement of the endometrium was observed in most PoRSEC cases (26/36, 72.2%) but also in a minority of SEIC cases (4/22, 18.2%). In all SEIC cases, there was a sharp cytological demarcation between SEIC and uninvolved endometrium; in PoRSEC cases, SEIC-like areas merged imperceptibly with more bland areas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Morphological features of PoRSEC. SEIC-like glands that merged imperceptibly with more bland areas characterize endometria with PoRSEC (A). Nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia with occasional nucleoli, frequent hobnail cells, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and clarification are the main features of PoRSEC (B, C, D, E). Note the simple papillae with areas of confluence and the sharp cytological demarcation between SEIC (with aberrant p53) and uninvolved endometrium (F)

Immunohistochemistry

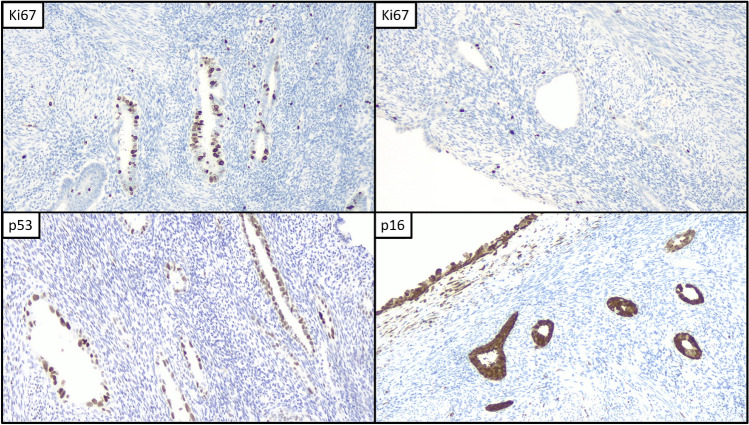

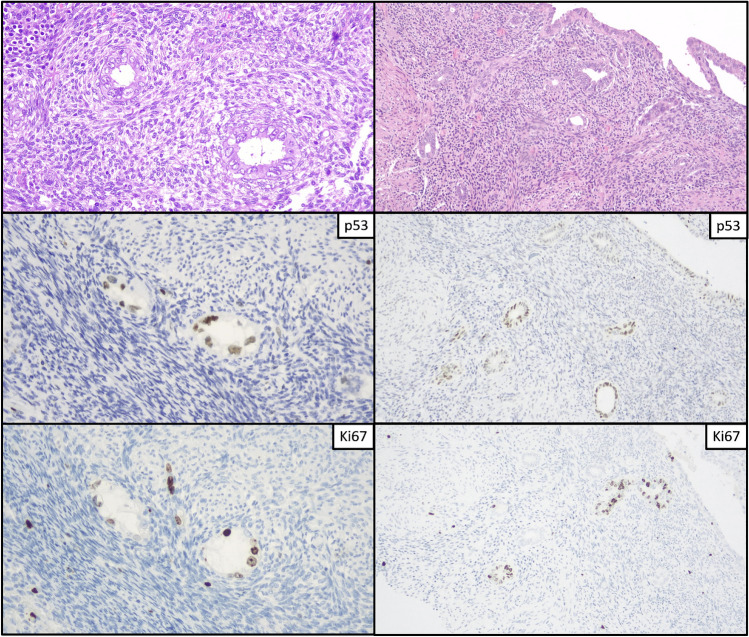

All SEIC cases showed a mutant pattern of p53 (moderate-to-strong positivity in > 80% of cells) overexpression, while PoRSEC cases showed a wild-type expression, including a wt-low pattern in 6/36 (16.7%) cases, a wt-intermediate pattern in 17/36 (47.2%) cases, and a wt-high pattern in 13/36 (36.1%) cases. Ki67 index was higher than 10% in only a minority of PoRSEC (8/36, 22.2%), with the higher value being 35%. On the other hand, all but three SEIC cases (86.4%) had a Ki67 index ≥ 10%, with the higher value being 70%. The mean Ki67 index was 8.2% in PoRSEC and 26.6% in SEIC (Figs. 2, 3). P16 showed a block-type pattern in all cases of SEIC and in 16/36 (44.4%) PoRSEC cases; the remaining PoRSEC cases showed a diffuse-patchy expression (16/36, 44.4%), a low expression (3/36, 8.3%), or absent expression (1/36, 2.8%) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical features of PoRSEC. Different range of Ki67, overexpression of p53, and block-type positivity of p16

Fig. 3.

Morphological and immunohistochemical features of PoRSEC. Two cases with endometrial glands showing nuclear atypia and occasional nucleoli with high expression of p53 and low-to-high Ki67 index

Table 1.

Clinical, morphological, and immunohistochemical data

| Diagnosis | PoRSEC | SEIC |

|---|---|---|

| N. patients | 36 | 22 |

| Age | 50.2 | 67.3 |

| Endometrial involvement | ||

| Focal | 10 | 18 |

| Diffuse | 26 | 4 |

| Ki67 (mean) | 8.20% | 26.60% |

| p16 | ||

| BT | 16 | 22 |

| DP | 16 | 0 |

| LP | 3 | 0 |

| Abs | 1 | 0 |

| p53 | ||

| Ab | 0 | 22 |

| H-wt | 13 | 0 |

| I-wt | 17 | 0 |

| L-wt | 6 | 0 |

p16—BT block type, DP diffuse patchy, LP low patchy, Abs absent. p53—H-wt-high wild type, I-wt-intermediate wild type, L-wt-low wild type, Ab aberrant

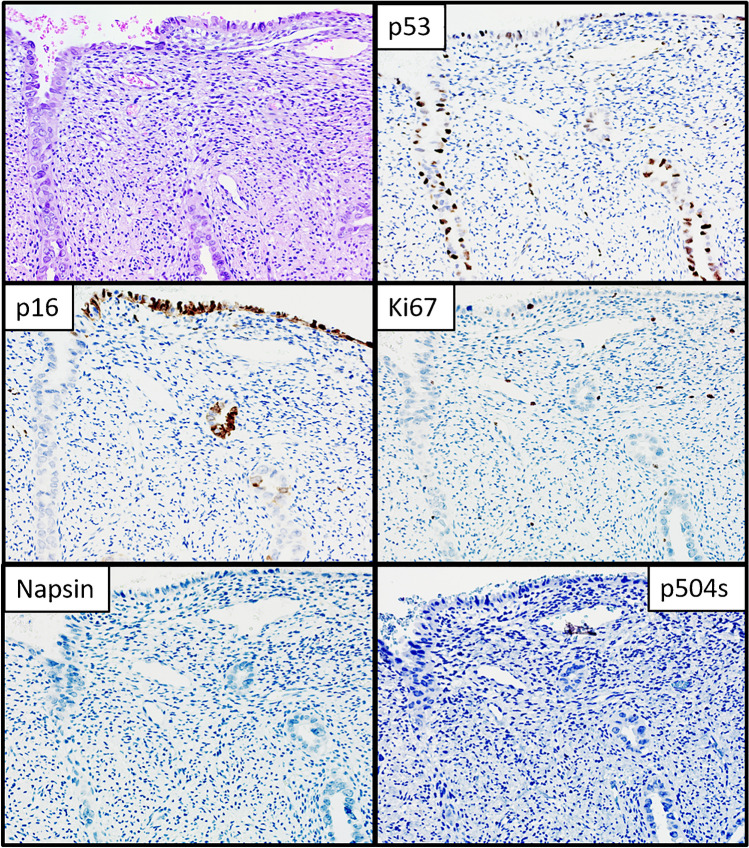

Twenty-one cases with hobnail or clear cell appearance were tested for NapsinA and P504S and were all negative (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Morphological and immunohistochemical features of PoRSEC. A case with endometrial glands showing hobnail appearance with expression of p53 and p16 with a low Ki67 index. No expression of NapsinA and p504s was observed

Discussion

This study showed that PoRSEC may show morphological and immunophenotypical overlap with SEIC. However, a papillary architecture with confluent papillae is observed in SEIC but not in PoRSEC. Moreover, SEIC shows cytological demarcation with normal endometrium, while PoRSEC appears as a diffuse change which merges imperceptibly with normal glands.

The distinction between reactive/regenerative atypia and true neoplastic atypia can be challenging. In the endometrium, reactive changes may raise the concern of several types of premalignant and malignant lesions, such as atypical hyperplasia, complex papillary proliferations, and SEIC [7–10]. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia and complex papillary proliferations are characterized by glandular crowding and branching papillae, respectively, which are typically absent in reactive changes [11, 12]. By contrast, SEIC may replace the epithelial lining of endometrial atrophic glands without affecting their arrangement. The typical feature of SEIC is the presence of high-grade nuclear atypia with striking pleomorphism [13]. Endometrial reactive changes can show an “SEIC-like” atypia, including nuclear enlargement and pleomorphism, nuclear clarification or hyperchromasia, evident nucleoli, eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, and hobnail changes [9, 10]. This kind of atypia was also observed in our series of PoRSECs.

Our study was the first to systematically assess the morphological and immunophenotypical features of PoRSEC and the differential diagnosis with SEIC.

We found that, although the degree of atypia was similar between PoRSECs and SEICs, the former showed no evident mitotic activity. This finding is coexistent with those of our previous study, which showed no mitotic activity in endometrial metaplastic/reactive changes coexistent with cancer [5]. However, in our experience, mitotic figures can occasionally be found in reactive changes; this can be concerning, especially when the amount of examined tissue is scarce.

Although SEIC lacks branching papillae and prominent glandular crowding (as discussed above), it does show architecture complexity in the form of simple papillae which are areas of confluence, typically restricted to the surface endometrium, which was not observed in PoRSEC. Moreover, SEIC appeared as a circumscribed lesion, with a sharp cytological demarcation between the SEIC area and the background atrophic endometrium. On the other hand, PoRSECs extensively involved the endometrium with no abrupt transition between areas with high-grade atypia and areas with low-grade or no atypia.

Immunohistochemically, SEIC is characterized by a mutation-type p53 pattern; this reflects the presence of underlying TP53 mutation and can also be observed in the earliest precursor of serous carcinoma, i.e., the so-called p53 signature [13]. Consistently, we observed a mutation-type p53 pattern in all included SEIC cases. As expected, all PoRSEC cases showed a p53-wt expression; however, more than one-third of PoRSEC cases had a “wt-high” pattern, that is, a p53 positivity in 50–80% of tumor cells. Before strict criteria to define a mutation-type pattern were defined, a wt-high pattern was often interpreted as aberrant [14]. However, even in the presence of strict criteria, the distinction between the two patterns can be difficult at times.

P16 and Ki67 are adjunctive markers in the diagnosis of SEIC. Indeed, SEIC characteristically shows a strong and diffuse (“block-type”) p16 expression and a high Ki67 expression (indicating a high proliferation index) [15]. A block-type p16 expression was observed in all SEIC cases and in almost half of PoRSEC cases. A similar finding was observed in metaplastic/reactive changes in our previous study and may constitute a further pitfall. Regarding Ki67, the mean value of SEIC was considerably higher than that of PoRSEC; however, the two groups showed a partial overlap, with the highest value among PoRSEC being 35% and the lowest value among SEIC being 5%.

Overall, PoRSEC showed a heterogeneous pattern of immunohistochemical markers, as opposed to SEIC. Therefore, SEIC shows both a morphological and immunohistochemical demarcation, which is generally absent in PoRSECs.

Finally, a complete absence of NapsinA and p504s staining could be useful to rule out a diagnosis of clear cell—EIN.

Remarkably, this study only included patients with LACC treated with CRT, in which PoRSEC can be expected. However, in our experience, PoRSEC can also be observed in benign uteri from patients who underwent CRT for other carcinomas. If the information regarding the previous CRT is missing, the pathologist might not consider the possibility of PoRSEC. It appears therefore necessary to recognize the crucial morphological and immunohistochemical features of PoRSEC, in order to avoid a serious misdiagnosis.

Conclusion

Endometria from patients with LACC can show PoRSECs, which may morphologically and immunohistochemically mimic SEIC. Although the expression of p53, p16, and Ki67 is advisable for the differential diagnosis, there may be an overlap between SEIC and PoRSEC. In such a case, the presence of morphological and immunohistochemical demarcation, which is present in SEIC but not in PoRSECs, may be a useful aid.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

DA: conception, histological assessment, immunohistochemical assessment, data interpretation, writing (first draft and review and editing); GS: conception, histological assessment, immunohistochemical assessment, data interpretation, writing (first draft and review and editing); AT: conception, histological assessment, immunohistochemical assessment, writing (review and editing); NDA: conception, histological assessment, immunohistochemical assessment, writing (review and editing); AS: conception, histological assessment, writing (first draft); FI: data interpretation, validation, writing (review and editing); BPU: literature search, photomicrographs, writing (first draft); SS: literature search, photomicrographs, writing (first draft); AR: literature search, writing (first draft); MV: literature search, photomicrographs, writing (first draft); CF: data interpretation, validation, writing (first draft); RB: molecular procedures, writing (first draft); FC: molecular procedures, writing (review and editing); GFZ: histological assessment, immunohistochemical assessment, data interpretation, validation, writing (review and editing).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Consent to participate

A written consent was obtained from the patient. Data were anonymized.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Damiano Arciuolo and Giulia Scaglione contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Markovina S, Rendle KA, Cohen AC et al (2022) Improving cervical cancer survival-a multifaceted strategy to sustain progress for this global problem. Cancer 128(23):4074–4084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesack D, Wahab I, Gilks CB (1996) Radiation-induced atypia of endocervical epithelium: a histological, immunohistochemical and cytometric study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 15(3):242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim EK, Yoon G, Kim HS (2016) Chemotherapy-induced endometrial pathology: mimicry of malignancy and viral endometritis. Am J Transl Res 8(5):2459–2467 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wales C, Fadare O (2018) Chemotherapy-associated endometrial atypia: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Int J Surg Pathol 26(3):229–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travaglino A, Inzani F, Santoro A et al (2021) Endometrial metaplastic/reactive changes coexistent with endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma: a morphological and immunohistochemical study. Diagnostics (Basel) 12(1):63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelico G, Santoro A, Inzani F et al (2021) An emerging anti-p16 antibody-BC42 clone as an alternative to the current E6H4 for use in the female genital tract pathological diagnosis: our experience and a review on p16ink4a functional significance, role in daily-practice diagnosis, prognostic potential, and technical pitfalls. Diagnostics 11(4):713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolae A, Preda O, Nogales FF (2011) Endometrial metaplasias and reactive changes: a spectrum of altered differentiation. J Clin Pathol 64(2):97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip PP (2018) Benign endometrial proliferations mimicking malignancies: a review of problematic entities in small biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch 472(6):907–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCluggage WG, McBride HA (2012) Papillary syncytial metaplasia associated with endometrial breakdown exhibits an immunophenotype that overlaps with uterine serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 31(3):206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon RA, Peng SL, Liu F et al (2011) Tubal metaplasia of the endometrium with cytologic atypia: analysis of p53, Ki-67, TERT, and long-term follow-up. Mod Pathol 24(9):1254–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travaglino A, Raffone A, Saccone G et al (2019) Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of coexistent cancer: WHO versus EIN criteria. Histopathology 74(5):676–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu D, Chen T, Yu K et al (2022) A 2-tier subdivision of papillary proliferations of the endometrium (PPE) only emphasizing the complexity of papillae precisely predicts the neoplastic risk and reflects the neoplasia-related molecular characteristics-a single-centered analysis of 207 cases. Virchows Arch 481(4):585–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng W, Xiang L, Fadare O, Kong B (2011) A proposed model for endometrial serous carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 35(1):e1–e14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Köbel M, Ronnett BM, Singh N, Soslow RA, Gilks CB, McCluggage WG (2019) Interpretation of P53 immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinomas: toward increased reproducibility. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 38 Suppl 1(Iss 1 Suppl 1):S123-S131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Nafisi H, Ghorab Z, Ismill N et al (2015) Immunophenotypic analysis in Early Müllerian serous carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 34(5):424–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.