Abstract

Introduction

Clinical nursing preceptors (CNPs) teach nursing skills to students in real medical scenarios and develop their professionalism. The adequacy of CNPs’ teaching competencies affects the effectiveness of student learning, so it is crucial to seek the best evidence for teaching competency interventions. This report describes a protocol for a systematic review to identify and analyse interventions to enhance the teaching competencies of CNPs. The aims of this systematic review are to (1) summarise the characteristics, quality, effectiveness and limitations of existing intervention programmes that support or train CNPs in teaching competencies; and (2) identify knowledge gaps related to teaching competencies interventions for CNPs, thereby supporting future research on constructing and improving preceptor intervention programmes.

Methods and analysis

This protocol follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Protocols 2015 checklist. We will report this systematic review following the updated PRISMA 2020 checklist. Between 1 May 2024 and 30 May 2024, we will search PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and ProQuest (Health & Medical Collection). The intervention studies that focus on enhancing and supporting the core competencies of CNPs will be included. The two researchers will conduct the study screening, data extraction and quality appraisal independently. Disagreements will be addressed by discussion or the involvement of a third researcher. We will evaluate the quality of the included studies using the modified Educational Interventions Critical Appraisal Tool. Furthermore, we will label the training programme levels using Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation Model.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not applicable to this study. We will share the findings from the study at national and/or international conferences and in a peer-reviewed journal in the field of nurse education.

Keywords: Education, Medical; Nursing Care; Nurses; Systematic Review

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The systematic review will ensure rigour by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Protocols 2015 and PRISMA 2020 checklists.

The systematic review will evaluate the quality of each study according to the modified Educational Interventions Critical Appraisal Tool.

Kirkpatrick’s model will be used to label training programmes with the level they have covered.

This systematic review may fail to include relevant literature that is outside the databases searched.

This systematic review is limited to include studies published between January 2010 and May 2024.

Introduction

Clinical nursing education is the process of learning nursing care in a healthcare setting such as a hospital or community clinic.1 2 Clinical nursing preceptors (CNPs) play a crucial role in clinical nursing education as they teach nursing skills to students in real medical scenarios and develop their professionalism.3 4 CNPs show students how to apply theory to practice, assess patient needs and implement individualised care.4 5 They can personally demonstrate how to gain a patient’s trust and communicate well with them.5 These tutorials orientate students to the cultural and social aspects of the clinical environment, helping shape their professional values as they prepare for practice.3 6 An increasing number of hospitals are adopting preceptorship-based models of clinical nursing education, where a preceptor supervises a student for a designated period of time.7

As educators in clinical settings, CNPs’ core competencies significantly impact the learning effectiveness of students and new nurses as effective guidance in the educational process requires specialised skills.8 Core competencies of CNPs have been discussed in some previous studies.9,11 For instance, a Delphi study that included 25 experts identified core competencies for clinical nurse educators. These competencies include clinical teaching, clinical nursing skills, management and leadership, as well as innovation and research.9 In Chen’s study, seven core competencies for nurse mentors were identified in order of importance: teaching traits, clinical nursing profession, communication and collaboration, teaching pedagogy, reaction of contingency, critical thinking and reflection and consultation on academic writing.10 In 2016, the WHO defined the nurse educator core competencies as the professional knowledge, attitudes and skills required to provide high-quality nursing education.11 Adequate teaching skills, clinical nursing competencies and good communication and management qualities are core elements of qualified CNPs. CNPs with excellent core competencies can enhance new nurses’ nursing competence and career satisfaction. Additionally, they can improve nursing students’ confidence and clinical critical thinking.12,14

CNPs are typically clinical registered nurses, and transitioning from clinical expert to educator can be challenging.15 Therefore, novice preceptor members must be supported in their shift from clinical expert to CNPs through comprehensive training programmes.16 It has been noted that without guidance and support novice clinical teachers will struggle to perform.16 17 Trained CNPs know how to accurately transfer knowledge to nursing students and new nurses using appropriate teaching methods, such as scenario-based simulation and case-based learning methods.18 19 In addition, CNPs with educational instruction and training understand the connection between clinical teaching objectives and student performance.16 20 They can use assessment checklists aligned with the objectives to ensure that students have understood and mastered the knowledge.20 21

However, CNPs’ educational support and training programmes vary significantly in quantity and quality, as well as in focus and format.22 The quality of these intervention programmes directly impacts the effectiveness of training, leading to inconsistent core competencies among CNPs.23 Therefore, it is important to seek the best evidence for core competencies interventions. There have been some reviews summarising intervention programmes for CNPs.423,26 DeWolfe’s review concluded that there was a lack of reliable evidence about which particular strategy was more effective, but did not assess the quality of the studies using specific criteria or numerical indicators.24 Windey’s review included only quantitative studies of clinical residency preceptor programmes and did not consider other healthcare scenarios.25 Kamolo’s review search was limited to the term ‘Preceptor’ and may have overlooked other studies that included related terms.26 Wu’s review is limited to online training programmes.4 Griffiths’ review only included clinical preceptor programmes for undergraduate students, omitting preceptor programmes for graduate students and new nurses.23 Additionally, it retrieved articles only from CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar, which may have led to the omission.23 Although these reviews provide insights into preceptor training programmes, they do not comprehensively examine the best evidence on intervention programmes for CNPs.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to identify and analyse existing interventions to enhance the core competencies of CNPs. This study will evaluate the quality of articles using quantitative indicators and summarise the effectiveness and limitations of intervention programmes. This systematic review will answer the following questions: (1) What interventions are available globally to strengthen the core competencies of CNPs? (2) What are the characteristics of these interventions? (3) What is the quality rating of these studies? (4) How effective are the interventions and what are their limitations?

Methods

This systematic review will focus on identifying and analysing intervention studies that enhance the core competencies of CNPs. This protocol for a systematic review will follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Protocols 2015 checklist.27 We will report this systematic review following the updated PRISMA 2020 checklist.27 We have registered the protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies

Studies will be included if they

Report interventions to enhance CNPs’ core competencies;

Focus on clinical registered nursing professionals who are currently or have supervised undergraduate, graduate and new nurses in the clinical setting.

Are experimental, quasi-experimental or mixed-methods design studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

Have full-text availability. The authors of the articles will be approached if a full-text version is not available online. However, if the authors’ contact information is not available or the authors do not respond to the inquiry, these studies will be excluded.

Studies will be excluded if they:

Are not primary studies (eg, discussion papers, letters and editorials) or case studies.

Only report on the construction and content of the intervention programme and do not implement the intervention.

Only address the professional competencies of nurses and does not include teaching-related competencies.

Search strategy

Between 1 May 2024 and 30 May 2024, we will search PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and ProQuest (Health & Medical Collection). Articles published between January 2010 and May 2024 will be included as they respond to transformative developments in nursing education and the need for high-quality evidence. Searches strategies will include Medical Subject Heading (if available) and free-text terms. References in all eligible literature were also searched to prevent omissions. The main search concepts will be teaching competenc* / core competenc* ; preceptor* / educator* / instructor* / supervisor* ; workshop* / training / program* /Intervention* ; nurs*. The search will not be limited to a specific language in order to include as much of the available evidence as possible. More specific details about search strategy are presented in online supplemental table S1 of the supplementary material. Two independent researchers will conduct the article search, and in case of inconsistency, a third researcher will intervene to decide.

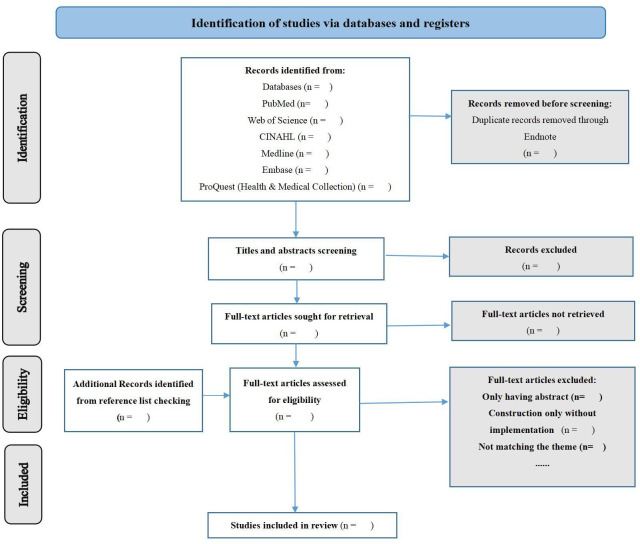

Study screening

We will use the literature manager EndNote and the online software Covidence to conduct the study screening. First, we will import the retrieved literature and references that meet the inclusion criteria into EndNote. After deleting duplicate records, the remaining articles will be imported into Covidence. Two independent researchers will read the titles and abstracts and screen out articles that do not fit the topic. Then they will read the full text to determine whether the article type and the conceptualisation being measured met the requirements, The final included articles will undergo data extraction and quality appraisal. The flowchart of the screening process is shown in figure 1. A third researcher will intervene to decide when there is a difference of opinion.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the literature selection process.

Data extraction

The data from all included studies will be extracted descriptively. Details of the data extraction will include (1) the characteristics of the study (online supplemental table S2 of the supplementary material, including first author and year, country, sample, design, primary outcomes, data collection method, results); (2) information on intervention programmes (online supplemental table S3 of the supplementary material, including first author, year and country, training title, contents, mode of delivery, theoretical framework, effectiveness and limitations of programme) and (3) results of the quality appraisal (online supplemental table S4 of the supplementary material). The two researchers will conduct the data extraction independently, and any disagreements will be resolved through discussions. For mixed-method studies, we will extract the research methods, tools and results for both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of each study. Additionally, we will summarise the effectiveness and limitations of the intervention from both perspectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of the study outcomes.

Quality appraisal and data synthesis

The quality of the included articles will be evaluated using a modified checklist instrument for critically appraising studies of educational interventions, developed by Morrison et al.28 The name of this instrument is ‘Educational Interventions Critical Appraisal Tool (EICAT)’.28 This instrument was developed by an iterative process and piloted. It has nine separate questions that focus on the research question, intervention, educational context, study design, methodology of the outcome measures and so on. Some questions have more precise entries under them, making the list a total of 22 criteria. The quality of the studies will be determined by answering these 22 criteria.

Although this checklist makes provisions for study design and intervention, the development team does not attach scores or grades to each question. This makes it difficult to directly compare the results of quality appraisal. In contrast, the modified EICAT (mEICAT) assigns a score to each criteria, with a score of 1 and 0 for ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. Each study will receive a quality rating based on its total score of the mEICAT (High, Moderate, Low). The score range for each of the quality ratings was determined by the following interval width equation: (Highest score (22) − 1) / Number of rating levels (3), which is equal to the interval width of 7. Thus, included studies that have a total score of 0–7 will be determined ‘Low’, a total score of 8–14 will be determined ‘Moderate’ and a total score of 15 or higher will be determined ‘High’. The quality ratings of the studies also represent the quality of the intervention programme. Although such ratings would somewhat ignore the uniqueness and applicability of each intervention, they facilitate comparisons across interventions and the generation of best evidence. The results of this part are presented in online supplemental table S4 of the supplementary material.

Kirkpatrick’s model, also known as Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation, is a key tool for assessing the effectiveness of training.29 Kirkpatrick’s model consists of four levels: Reaction, Learning, Behaviour and Results.29 It can be used to assess formal or informal learning and can be used for any style of training. This model is globally recognised as one of the most effective evaluations of training.30 31 The first level is learner-focused, measuring whether learners find the training relevant, engaging and useful for their roles.29 The second level assesses whether learners have acquired the knowledge, skills, attitude, confidence and commitment targeted by the training programme.29 The third level evaluates behavioural changes, indicating whether learners are applying what they learnt in their job roles.29 The fourth level examines whether the achievement of targeted outcomes resulting from the training, as well as the support and accountability of organisational members.29 Labelling training programmes according to the levels of Kirkpatrick’s model helps clarify the depth and breadth of their content.

First, researchers will respond to each mEICAT questions by selecting either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ based on the article’s content, assigning a score of 1 for ‘Yes’ and 0 for ‘No’. Second, we will calculate a total score for each study, ranging from 0 to 22. Finally, articles will be rated as ‘High’, ‘Moderate’ or ‘Low’ based on the total score and assigned the corresponding Kirkpatrick’s levels. The entire process above will be done independently by two researchers, and any disagreements will be resolved through discussions. The results are presented in online supplemental table S4 of the supplementary material.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public will be involved in this study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not applicable to this study. We will share the findings from the study at national and/or international conferences and in a peer-reviewed journal in the field of nurse education.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.72104250) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No.2022JJ40642).

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088939).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Ke Liu, Email: 2641323590@qq.com.

Shuyi Wang, Email: wsy251941@csu.edu.cn.

Xirongguli Halili, Email: 747228557@qq.com.

Qirong Chen, Email: qirong.chen@csu.edu.cn.

Minhui Liu, Email: mliu62@jhu.edu.

References

- 1.Immonen K, Oikarainen A, Tomietto M, et al. Assessment of nursing students’ competence in clinical practice: A systematic review of reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;100:103414. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Sala R, Coppola D, Ruozi C, et al. Competence assessment of the clinical tutor: a multicentric observational study. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:e2021016. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS2.11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgess A, van Diggele C, Roberts C, et al. Key tips for teaching in the clinical setting. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu XV, Chan YS, Tan KHS, et al. A systematic review of online learning programs for nurse preceptors. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;60:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennbrant S. Determination of the Concepts “Profession” and “Role” in Relation to “Nurse Educator”. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32:430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson M-C, Sawatzky J-A. Clinical placement anxiety in undergraduate nursing students: A concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;87:104329. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin N. Clinical supervision in undergraduate nursing students: a review of the literature. J Bus Educ Sch Teach. 2013:34–42. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1167345.pdf Available. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins-Weintaub E, Goodwin M, Fingerhood M. Competency-based evaluation: Collaboration and consistency from academia to practice. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2023;35:142–9. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye J, Tao W, Yang L, et al. Developing core competencies for clinical nurse educators: An e-Delphi-study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;109:105217. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen T-T, Hsiao C-C, Chu T-P, et al. Exploring core competencies of clinical nurse preceptors: A nominal group technique study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;56:103200. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2016. Nurse educator core competencies.http://who.int/hrh/nursing_midwifery/nurse_educator050416.pdf Available. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ke YT, Kuo CC, Hung CH. The effects of nursing preceptorship on new nurses’ competence, professional socialization, job satisfaction and retention: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:2296–305. doi: 10.1111/jan.13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin C, Bliss J, Poole K. Does Preceptorship improve confidence and competence in Newly Qualified Nurses: A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;60:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause SA. Precepting Challenge: Helping the Student Attain the Affective Skills of a Good Midwife. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:37–46. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perryman KW. Nurse practitioner preceptor education to increase role preparedness. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2022;34:763–8. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross JG, Silver Dunker K. New Clinical Nurse Faculty Orientation: A Review of the Literature. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2019;40:210–5. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silver Dunker K, Manning K. Live Continuing Education Program for Adjunct Clinical Nursing Faculty. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39:16–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pohjamies N, Haapa T, Kääriäinen M, et al. Nurse preceptors’ orientation competence and associated factors-A cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:4123–34. doi: 10.1111/jan.15388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cen X-Y, Hua Y, Niu S, et al. Application of case-based learning in medical student education: a meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:3173–81.:25726. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202104_25726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KV. Improving Adjunct Nursing Instructors’ Knowledge of Student Assessment in Clinical Courses. Nurse Educ. 2016;41:108–10. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Good B. Improving Nurse Preceptor Competence With Clinical Teaching on a Dedicated Education Unit. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2021;52:226–31. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20210414-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suplee PD, Gardner M, Jerome-D’Emilia B. Nursing faculty preparedness for clinical teaching. J Nurs Educ. 2014;53:S38–41. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20140217-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths M, Creedy D, Carter A, et al. Systematic review of interventions to enhance preceptors’ role in undergraduate health student clinical learning. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;62:103349. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeWolfe JA, Perkin CA, Harrison MB, et al. Strategies to prepare and support preceptors and students for preceptorship: a systematic review. Nurse Educ. 2010;35:98–100. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181d95014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Windey M, Lawrence C, Guthrie K, et al. A Systematic Review on Interventions Supporting Preceptor Development. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2015;31:312–23. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamolo E, Vernon R, Toffoli L. A critical review of preceptor development for nurses working with undergraduate nursing students. Int J Caring Sci. 2017:1089–100. https://internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/50_kamolo_special_10_2.pdf Available. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison JM, Sullivan F, Murray E, et al. Evidence-based education: development of an instrument to critically appraise reports of educational interventions. Med Educ. 1999;33:890–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurt S. Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation. Educ Technol. 2018 https://educationaltechnology.net/kirkpatrick-model-four-levels-learning-evaluation/ Available. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston S, Coyer FM, Nash R. Kirkpatrick’s Evaluation of Simulation and Debriefing in Health Care Education: A Systematic Review. J Nurs Educ. 2018;57:393–8. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20180618-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang X, Wang R, Chen J, et al. Kirkpatrick’s evaluation of the effect of a nursing innovation team training for clinical nurses. J Nursing Management . 2022;30:2165–75. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]