Abstract

Background and objective

The 2014 Hazelwood coal mine fire exposed residents in nearby Morwell to high concentrations of particulate matter <2.5 µm (PM2.5) for approximately 6 weeks. This analysis aimed to evaluate the long-term impact on respiratory health.

Methods

Adults from Morwell and the unexposed town of Sale completed validated respiratory questionnaires and performed spirometry, gas transfer and oscillometry 3.5–4 years (round 1) and 7.3–7.8 years (round 2) after the fire. Individual PM2.5 exposure levels were estimated using chemical transport models mapped onto participant-reported time-location data. Mixed-effects regression models were fitted to analyse associations between PM2.5 exposure and outcomes, controlling for key confounders.

Results

From 519 (346 exposed) round 1 participants, 329 (217 exposed) participated in round 2. Spirometry and gas transfer in round 2 were mostly lower compared with round 1, excepting forced vital capacity (FVC) (increased) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (minimal change). The effect of mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure changed from a negative effect in round 1 to no effect in round 2 for both pre-bronchodilator (p=0.005) and post-bronchodilator FVC (p=0.032). PM2.5 was not associated with gas transfer in either round. For post-bronchodilator reactance and area under the curve, a negative impact of PM2.5 in round 1 showed signs of recovery in round 2 (both p<0.001).

Conclusion

In this novel study evaluating long-term respiratory outcomes after medium-duration high concentration PM2.5 exposure, the attenuated associations between exposure and respiratory function may indicate some recovery in lung function. With increased frequency and severity of landscape fires observed globally, these results inform public health policies and planning.

Keywords: Respiratory Function Test, COPD epidemiology, Occupational Lung Disease, Respiratory Measurement

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Evidence is currently lacking on the long-term sequelae of high concentration PM2.5 exposure, from extreme landscape fire events lasting weeks to months, on lung physiology and function.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We found that previously observed deficits in adult lung function, measured using spirometry, gas transfer and oscillometry 3.5 years after a prolonged coal mine fire, may recover in the longer-term.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

With increased frequency of prolonged landscape fires observed globally, these results inform public health, and emergency response, policy makers and planners of the need to limit smoke exposure in fire-effected communities.

Introduction

Continued exposure to ambient air pollution, especially particulate matter (PM) from sources such as industry, vehicle exhaust, biomass fuels, and landscape fires such as wildfires and mine fires, is leading to premature deaths and disease worldwide. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 highlighted particulate matter air pollution as the leading contributor to global disease burden and premature deaths, a burden disproportionately borne by low-income and middle-income countries.1 In particular, fine PM with a median aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm (PM2.5) is able to infiltrate deep into the lung periphery and the blood stream.2 3 It was estimated that 4.1 million premature deaths in 2019, representing 7.3% of total deaths globally and 4.7% of global disability-adjusted life years, were attributable to the long-term exposures to PM2.5.4 5 There is a strong causal association between PM2.5 exposure and cardiopulmonary diseases.6 Increasing PM2.5 exposure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) prevalence and lung function decline have been well documented.7

Evidence is currently lacking on the long-term sequelae of PM2.5 exposure from medium-term ambient PM2.5 exposure (weeks to months) from extreme events such as prolonged landscape fires on lung physiology and function.8 Indeed, studies of landscape fires often use secondary data, such as hospital presentation records, to infer respiratory associations.9 With climate change, and the increasing frequency, intensity and duration of landscape fires globally, addressing these gaps in evidence is critical to formulation of health policies.10

In February 2014, a fire in the Hazelwood open-cut brown coal mine, located in the Latrobe Valley, south-eastern Australia, exposed nearby residents to significant ambient air pollution for approximately 6 weeks. The adjacent town of Morwell, with a population at the time numbering approximately 14 000, experienced the most extreme smoke levels. Hourly mine fire-related PM2.5 concentrations were estimated to have reached 3700 µg/m311 12 during the initial phase of the fire. The daily average National Environment Protection Measure standard of 25 µg/m3 was breached on 27 days during February and March 2014 in Morwell.12 A Victorian Government appointed Board of Inquiry into the mine fire heard that the Latrobe Valley community, particularly those in Morwell, reported a variety of physical symptoms including sore and stinging eyes, coughing, shortness of breath, headaches, chest pain, fatigue, mouth ulcers, blood noses and rashes.13

The Hazelwood Health Study (HHS; hazelwoodhealthstudy.org.au) was established to investigate the long-term adverse health outcomes in people exposed to the mine fire smoke. The Study’s Hazelinks Stream, which analysed administrative health service use data, reported dose-response associations between increasing PM2.5 exposure and increased respiratory-related ambulance attendances,14 emergency department presentations and hospital admissions,15 general practitioner and specialist consultations16 and dispensing of medications.17

The HHS Adult Cohort (n=4056) was established in 2016 and comprised adult residents of Morwell (exposed) and Sale (unexposed but otherwise similar town—refer to table 1 in Holt et al18) who completed the Adult Survey.19 20 A subgroup of 519 cohort members subsequently participated in round 1 (R1) of the HHS adult Respiratory Stream in 2017–2018.18 Adult Cohort members who had reported an asthma attack or current asthma medication use in the Adult Survey were oversampled (40%) to provide ability for further evaluation of effects in asthmatics. The HHS adult Respiratory Stream aimed to investigate the association between exposure to mine fire-related PM2.5 and lung function at approximately 3, 6 and 9 years after the event.18 At R1, 3.5 years after the fire, there was a clear dose-response relationship between medium-duration but extreme mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure and spirometry consistent with COPD in non-smokers21 and worsening lung mechanics.18

Table 1. Participant characteristics at the time of each clinical assessment round.

| Characteristic | Round 1 | Round 2 |

| n=519 | n=329 | |

| Town, n (%) | ||

| Morwell | 346 (67%) | 217 (66%) |

| Sale | 173 (33%) | 112 (34%) |

| At the time of the mine fire: daily exposure to fire-related PM2.5 (µg/m3), median (Q1–Q3) | ||

| Morwell | 11.7 (7.2–18.4) | 11.8 (7.2–17.4) |

| Sale | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.9 (16.1) | 57.9 (15.2) |

| Age category at each round, n (%) | ||

| <45 years | 151 (29%) | 73 (22%) |

| 45–65 years | 211 (41%) | 139 (42%) |

| >65 years | 157 (30%) | 117 (36%) |

| Female, n (%) | 306 (59%) | 195 (59%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed | 229 (44%) | 143 (43%) |

| Other (retired, home duties, study, other) | 216 (42%) | 153 (47%) |

| Unemployed/unable to work | 74 (14%) | 33 (10%) |

| Post-secondary education, n (%) | 291 (57%) | 196 (60%) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 166 (9) | 167 (9) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 85.6 (21.3) | 86.6 (21.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 31.0 (7.4) | 30.8 (7.4) |

| BMI, n (%) | ||

| Underweight/normal (BMI <25 kg/m2) | 99 (19%) | 66 (20%) |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30 kg/m2) | 167 (32%) | 100 (30%) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 253 (49%) | 163 (50%) |

| Self-reported asthma, n (%) | 229 (44%) | 147 (45%) |

| Spirometric COPD, n (%) | 59 (12%) | 41 (13%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Non-smoker | 249 (48%) | 173 (53%) |

| Ex-smoker | 186 (36%) | 114 (35%) |

| Current smoker | 84 (16%) | 42 (13%) |

Missing: education n=10; height n=2; weight n=3; BMI n=3; COPD n=20.

BMI, Body Mass Index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PM2.5, particulate matter <2.5 µg/m³; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile

In a second round of respiratory testing (R2) conducted in 2021, we aimed to investigate the longer-term impacts of mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure on respiratory health. Because background ambient PM2.5 exposure had the potential to confound associations between fire-related PM2.5 exposure and health, and because many of the HHS participants were potentially exposed to ambient smoke from the 2019 to 2020 ‘Black Summer’ wildfires, examination of PM2.5 levels in Morwell and Sale during these wildfires was conducted.

Methods

Study design and setting

The Respiratory Stream of the HHS is a longitudinal cohort study. A flowchart showing the study recruitment process is provided in online supplemental figure S1 in Supporting Information. Recruitment for R2 was originally planned for 2020; however, that was postponed due to COVID-19-related lockdowns. R2 data collection went ahead in the Latrobe Valley between May and November 2021.

Patient and public involvement

The Latrobe Valley community has had ongoing involvement in the design and conduct of the HHS. In the immediate aftermath of the mine fire, a Board of Inquiry into the Hazelwood coal mine fire held 10 community consultations encouraging members to describe their experiences and concerns. The Board also received more than 700 public submissions and heard from six independent experts and 13 community witnesses. The HHS was subsequently designed in direct response to the community’s concerns. The HHS Community Advisory Committee (CAC) was later convened in February 2015 and has met at least quarterly since. The CAC initially comprised five community lay persons and representatives from seven local organisations (Latrobe City Council, Latrobe Community Health Service, Latrobe Regional Hospital, the Department of Health Gippsland, Federation University, Wellington Shire and the Central Gippsland Health Service Board). In July 2021, the CAC merged with the activities of the existing Latrobe Health Assembly (LHA) and became the LHA HHS subcommittee, comprising four LHA members and four community members. The Committee provides advice on all aspects of the HHS’s activities including study design, recruitment and disseminations of findings.

Participant recruitment and characteristics

Participants were eligible for the 2021 Respiratory Stream R2 assessment if they had participated in R1 in 2017.18 Participants were excluded if they were aged over 90 years, or identified to be deceased. Otherwise, eligible participants were also excluded if a contraindication to spirometry was identified—including recent surgery, myocardial infarction, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, open pulmonary tuberculosis or known aneurysms.22 Recruitment was via mailed invitation, email, Short Message Service or phone call, depending on the last known contact details. Measurement of participant characteristics varied across the Adult Survey and clinical assessment rounds. Level of education, ethnicity, sex and town (Morwell/Sale) were obtained from the Adult Survey.20 In both R1 and R2, height and weight were measured during the clinic assessments, and age, employment and smoking history collected via questionnaires. Participants were classified as current, ex-smokers (current non-smokers with >100 lifetime cigarettes) or non-smokers (<100 lifetime cigarettes).23

Exposure assessment

Individual level mine fire exposure for all participants was previously calculated by mapping the hourly spatial and temporal distribution of mine fire-related PM2.5 concentrations onto participants’ time-location diary data captured as a part of the Adult Survey; detailed elsewhere.18,20 Australia’s Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation provided the PM2.5 distributions by rigorously estimating the fire emissions and using them in a high-resolution prognostic meteorological and dispersion model with local wind data assimilation and an appropriate plume rise mechanism.12 The model estimated hourly PM2.5 concentrations in 100 m2 grids within Morwell, and in 3 km2 grids within Sale, while participant diaries provided residential, work and other (eg, leave or travel) addresses across each day and night of the mine fire period. Mean 24-hour mine fire-related PM2.5 concentrations experienced by participants during the mine fire ranged from 0 to 56 µg/m3.

In addition to the coal mine fire, some participants were potentially exposed to smoke from the 2019 to 2020 ‘Black Summer’ wildfires, with Sale (unexposed to the mine fire), being closer to the region with major fires (far eastern Victoria) than Morwell. As described in more detail in Supporting Material online supplemental appendix S1, including online supplemental figures S2, S3, we used hourly PM2.5 data from the Environment Protection Authority of Victoria to evaluate possible exposure variations between the towns of Morwell and Sale, as a result of this event.

Because usual background ambient PM2.5 also had the potential to confound associations, we obtained annual mean ambient PM2.5 data for Morwell and Sale from 2009 to 2022, which included both the mine fire and the Black Summer wildfire period.

Clinical measures

Respiratory testing was performed by trained respiratory scientists at all sites for both data collection rounds, following standard operating procedures and in accordance with current respiratory measurement standards where available. Spirometry and gas transfer (transfer or diffusing factor of the lung for carbon monoxide; Tlco) were measured using the EasyOne Pro Lab Respiratory Analysis System (ndd Medical Technologies AG, Zürich, Switzerland) in line with international standards.24,26

Oscillometry was assessed using the Forced Oscillation Technique with the Tremoflo C-100 device (Thorasys, Montreal, Canada) in line with standards current at time of testing.27 28 Indices reported included resistance at 5 Hz (R5), difference in resistance at 5 and 19 Hz (R5-19), reactance at 5 Hz (X5) and the area under the reactance curve at 5 Hz (Ax5). Test acceptability was evaluated using guidelines on coherence criteria available at the time of the test.

Spirometry and oscillometry were performed before and after administration of short-acting bronchodilator (300 µg salbutamol). Bronchodilator use in the previous 24 hours was recorded, as bronchodilator therapy was unable to be withheld prior to assessment due to ethical reasons.

Participants were considered as having COPD if spirometry demonstrated a post-bronchodilator (BD) ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) < lower limit of normal (fifth percentile) using the Global Lung Initiative spirometry reference values.29 Self-reported asthma was captured via a modified European Community Respiratory Health Survey questionnaire30 in both rounds.

Spirometry quality was assessed according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society technical standards applicable at time of testing and graded accordingly.25 26 31 Results graded less than A or B were reviewed by an experienced, senior respiratory scientist (BB) and included or excluded based on likely validity of results.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (such as means and SD) were used to report characteristics and outcome differences between rounds. Mean differences in outcomes between the two rounds were compared with a mean of zero using one sample t-tests. To investigate potential selection bias, participant characteristics and outcomes at R1 were compared between the participants and non-participants of the R2 testing.

Z-scores of spirometry and gas transfer indices, calculated from the Global Lung Function Initiative reference equations for Spirometry and Tlco,29 32 were used as outcome variables. Non-linear transformations were used for oscillometry variables, as a high proportion of our participants fell outside the required prediction range for the published algorithm18 33 with z-scores used in sensitivity analyses.

To model the effect of mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure on each outcome over time, linear mixed effects models with random intercepts were used to account for repeated measurements. The models measured the effects of: (1) mine-fire related PM2.5 exposure (10 µg/m3 increase), (2) changes over time (from R1 to R2 using an indicator variable) and (3) whether the effect of exposure on the outcome changed over time (interaction between exposure and time). To assist with interpretation, the results were reported as effects of exposure (coefficients and 95% CI) on the outcome at R1 and R2 using linear combination of coefficients as well as p values for interaction terms (indicating whether the two coefficients were statistically distinguishable).

All models controlled for potential confounding factors (including education and employment, smoking status, self-reported asthma, spirometric COPD and other factors related to testing: age, gender, height and weight were included for outcomes without z-scores) and were weighted to correct for oversampling of asthmatics. Pre-bronchodilator outcomes were also adjusted for whether inhaled medication was withheld by asthmatics prior to spirometry. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing data in all regression analyses.34 Data were analysed using Stata v16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX 2017).

Results

Participant characteristics

From 519 (346 exposed from Morwell, 173 from Sale) R1 participants, 329 (217 exposed) participated in R2 (see online supplemental figure S1 in Supporting Information). Online supplemental tables S1, S2 in Supporting Information compare R2 participants with non-participants, indicating that characteristics were similar except for higher loss to follow-up among current smokers. Table 1 presents participant characteristics by respiratory assessment round. Participant demographic characteristics were comparable across clinical assessment rounds, except for higher loss to follow-up among current smokers. Two-thirds of participants were from Morwell, and 59% were female. The mean age was 54.9 years (SD 16.1) in R1 and 57.9 years (SD 15.2) in R2. Half the participants were categorised as obese (Body Mass Index; BMI ≥30 kg/m2), around 45% reported an asthma diagnosis, and approximately 13% had COPD based on spirometry at R1.

Examination of PM2.5 levels during the 2019–2020 ‘Black Summer’ wildfires suggested no evidence of different exposures between the two towns of Morwell and Sale (refer to online supplemental appendix S1 and online supplemental figures S2, S3 in Supporting Information). We also found little difference in annual mean background ambient PM2.5 between Morwell (7.9 μg/m3) and Sale (7.6 μg/m3) from 2009 to 2022.

Descriptive statistics for the study outcomes (z-scores for spirometry and gas transfer; transformed scores for oscillometry) are given in table 2 with crude values provided in online supplemental table S3 in Supporting Information and z-scores for oscillometry variables in online supplemental table S4 in Supporting Information. Spirometry and gas transfer z-scores in R2 were slightly lower compared with R1 assessment, except for FVC.

Table 2. Respiratory outcome means (z-scores or transformed) by assessment round and crude mean differences for those completing both rounds (R2–R1).

| Outcomes | Round 1 | Round 1(subset who participated in R2) | Round 2 | Differences (R2–R1) | ||

| n=519 | n=329 | n=329 | n=329 | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean diff | 95% CI | P value | |

| Spirometry (z-scores) | ||||||

| Pre-BD FEV1 | −0.49 (1.18) | −0.47 (1.16) | −0.41 (1.20) | 0.06 | (−0.01, 0.12) | 0.078 |

| Pre-BD FVC | −0.16 (1.03) | −0.13 (1.03) | 0.11 (1.09) | 0.24 | (0.17, 0.3) | <0.001 |

| Pre-BD FEV1/FVC | −0.61 (1.10) | −0.60 (1.07) | −0.86 (1.00) | −0.25 | (−0.31, –0.19) | <0.001 |

| Pre-BD FEF25%–75% | −0.57 (1.17) | −0.56 (1.14) | −0.71 (1.06) | −0.14 | (−0.21, –0.08) | <0.001 |

| Post-BD FEV1 | −0.18 (1.16) | −0.15 (1.11) | −0.15 (1.18) | −0.01 | (−0.07, 0.05) | 0.690 |

| Post-BD FVC | 0.00 (0.98) | 0.03 (0.96) | 0.16 (1.05) | 0.12 | (0.06, 0.18) | <0.001 |

| Post-BD FEV1/FVC | −0.32 (1.12) | −0.31 (1.09) | −0.49 (1.09) | −0.17 | (−0.22, –0.12) | <0.001 |

| Post-BD FEF25-75% | −0.17 (1.22) | −0.15 (1.19) | −0.28 (1.14) | −0.12 | (−0.17, –0.06) | <0.001 |

| Gas transfer (z-scores) | ||||||

| TLco | −0.19 (1.35) | −0.06 (1.25) | −0.18 (1.32) | −0.12 | (−0.21, –0.03) | 0.008 |

| Hb corrected TLco | −0.16 (1.32) | −0.04 (1.21) | −0.21 (1.33) | −0.17 | (−0.25, –0.09) | <0.001 |

| VA | −0.43 (1.04) | −0.40 (1.02) | −0.48 (0.97) | −0.08 | (−0.15, –0.01) | 0.030 |

| Kco | 0.17 (1.29) | 0.29 (1.23) | 0.21 (1.29) | −0.08 | (−0.16, 0.00) | 0.043 |

| Hb corrected Kco | 0.21 (1.27) | 0.32 (1.20) | 0.19 (1.29) | −0.12 | (−0.2, –0.04) | 0.002 |

| Oscillometry (non-linear transformed) | ||||||

| Pre-BD ln(R5) | 1.34 (0.39) | 1.33 (0.38) | 1.34 (0.38) | −0.02 | (−0.05, 0.02) | 0.275 |

| Pre-BD ln((R5-R19)+1) | 0.50 (0.44) | 0.48 (0.44) | 0.42 (0.47) | −0.10 | (−0.15, –0.05) | <0.001 |

| Pre-BD exp(X5) | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.26 (0.16) | 0.25 (0.17) | 0.00 | (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.888 |

| Pre-BD ln(Ax5) | 2.10 (0.99) | 2.04 (0.99) | 2.11 (1.11) | −0.02 | (−0.11, 0.08) | 0.735 |

| Post-BD ln(R5) | 1.24 (0.36) | 1.22 (0.36) | 1.20 (0.39) | −0.05 | (−0.08, –0.02) | 0.002 |

| Post-BD ln((R5-R19)+1) | 0.43 (0.37) | 0.41 (0.36) | 0.35 (0.42) | −0.09 | (−0.13, –0.05) | <0.001 |

| Post-BD exp(X5) | 0.30 (0.17) | 0.32 (0.17) | 0.30 (0.19) | 0.00 | (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.549 |

| Post-BD ln(Ax5) | 1.82 (0.94) | 1.74 (0.92) | 1.78 (1.08) | −0.06 | (−0.14, 0.03) | 0.174 |

Missing: oscillometry pre-BD R1 n=44; oscillometry post-BD R1 n=41; spirometry pre-BD R1 n=11; spirometry post-BD R1 n=11; gas transfer R1 n=11; oscillometry pre-BD R2 n=3; oscillometry post-BD R2 n=2; spirometry pre-BD R2 n=6; spirometry post-BD R2 n=7; gas transfer R2 n=4.

Ax5, area under the reactance curve at frequency 5 HzBD, bronchodilator; diff, difference; FEF, forced expiratory flow; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; Hb, haemoglobin; Kco, carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; R1, round 1; R2, round 2; R5, resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference in resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; TLco, transfer/diffusion factor of the lung for carbon monoxide; VA, alveolar vol; X5, reactance at frequency 5 Hz

Spirometry quality was very good with less than 1% of R1 tests, and only 1.5% of R2 tests, excluded based on likely validity of results (online supplemental table S5 in Supporting Information).

The associations between mine fire-related Pm2·5 exposure and lung function

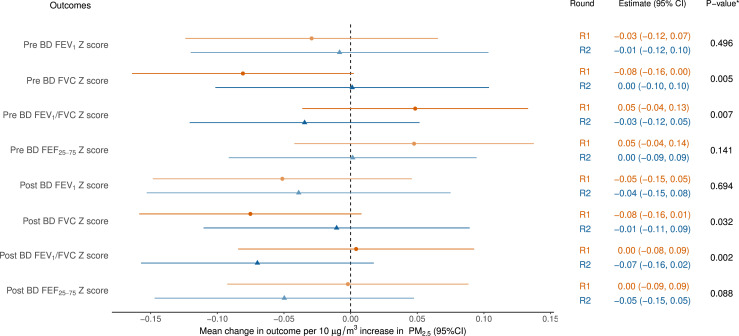

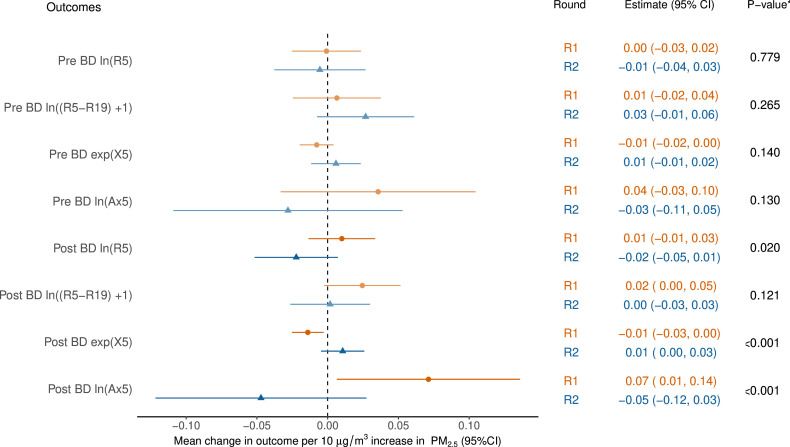

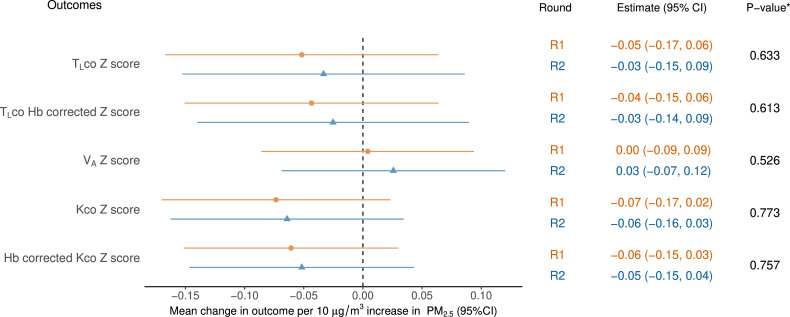

Figures13 show the estimated effect of mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure on each lung function outcome at R1 and R2 as well as the p values for the interaction term between exposure and round (pint).

Figure 1. Models of spirometry as a function of mine fire-related PM2.5. *p values for the interaction term between exposure and round. All models adjusted for education, employment, asthma and smoking status. Pre-BD outcomes also adjusted for whether inhaled medication was withheld. BD, bronchodilator; FEF, forced expiratory flow; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; PM2.5, particulate matter <2.5 µg/m³; R1, round 1; R2, round 2.

Figure 3. Models of oscillometry as a function of mine fire-related PM2.5. *p values for the interaction term between exposure and round. All models adjusted for age, gender, height, weight, education, employment, asthma, spirometric chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and smoking status. Pre-BD outcome also adjusted for whether inhaled medication was withheld prior to spirometry. Ax5, area under the reactance curve at 5 Hz; BD, bronchodilator; PM2.5, particulate matter <2.5 µg/m³; R1, round 1; R2, round 2; R5, resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference in resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; X5, reactance at 5 Hz.

Spirometry and gas transfer in R2 were lower compared with R1, excepting FVC (unadjusted mean increase 60 mL). Using FVC z-score as an example (figure 1), there was a small mean decrease of 0.08 in baseline (pre-BD) FVC z-score for every 10 µg/m3 increase in mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure (95% CI: −0.16 to 0.00) in R1, which was reduced to no mean change of 0.0 (−0.10 to 0.11) in R2. The overall effect of exposure changed over time from a negative effect in R1 to no effect in R2 (pint=0.005). This effect was similar to post-BD FVC z-score (pint=0.032). As a result, a reversed direction of association for FEV1/FVC z-scores was evident both at pre-BD (pint=0.007) and post-BD (pint=0.002). However, generally, the estimated mean change in spirometry outcomes with increasing PM2.5 exposure overlapped with the null effect in both rounds (figure 1). Similarly, exposure to mine fire-related PM2.5 was not found to be associated with gas transfer at either round, and the effect was unchanged between rounds (figure 2).

Figure 2. Models of gas transfer as a function of mine fire-related PM2.5. *p values for the interaction term between exposure and round. All models adjusted for education, employment, spirometric chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and smoking status. Hb, haemoglobin; Kco, carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; PM2.5, particulate matter <2.5 µg/m³; R1, round 1; R2, round 2; TLco, transfer/diffusion factor of the lung for carbon monoxide; VA, alveolar vol.

Figure 3 shows the estimated effect of PM2.5 exposure on transformed oscillometry outcomes. The main changes were for post-BD resistance (ln[R5]), reactance (exp[X5]) and area under the reactance curve (ln[Ax5]). For both post-BD reactance and area under the reactance curve, a negative impact of exposure in R1 showed signs of recovery in R2 (both pint<0.001). These results were consistent using the oscillometry z-scores as a function of PM2.5 (see online supplemental figure S4 in Supporting Information).

Discussion

Assessment of participants at 3.5–4 (round 1) and 7.3–7.8 years (round 2) after the Hazelwood coal mine fire revealed an attenuated association between medium-duration exposure to extreme coal mine fire-related PM2.5 and several respiratory function measures. The effect of exposure on spirometry changed over time, from a negative effect in R1 to no effect in R2 for both pre-bronchodilator and post-bronchodilator FVC. The estimated mean change in spirometry with increasing PM2.5 exposure overlapped with a null effect in both rounds. This null finding evaluating the association between PM2.5 exposure and change in lung function is consistent with prior community-based cohort studies from Europe.35 36

This was the first study using oscillometry to evaluate the long-term respiratory impact after medium-duration coal mine fire smoke-related PM2.5 exposure. R1 revealed a clear dose-response association between coal mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure and a more negative respiratory system reactance.18 We acknowledge that part of this observed effect may be attributable to normal ageing. The underlying mechanism remains unclear, although one possible explanation might be early peripheral airway changes with accelerated pulmonary ageing. For the estimated effect of PM2.5 exposure on transformed oscillometry outcomes, both post-bronchodilator reactance and area under the reactance curve, a negative impact of exposure in R1 showed signs of recovery in R2. This observation may reflect potential recovery of lung function following an episode of medium-duration high-intensity PM2.5 exposure.

Oscillometry assesses lung mechanics and may detect early changes in peripheral airway function that conventional spirometry cannot.27 Oscillometry has previously been used to evaluate changes in lung mechanics in firefighters exposed to asbestos37 and dust exposure from the World Trade Centre following the 9/11 attacks,38 39 where spirometry was normal, but abnormalities were detected in oscillometry. To our knowledge, no prior study has evaluated the long-term sequelae of PM2.5 exposure from landscape fires such as mine fires or biomass fuel smoke using oscillometry. Our findings add valuable insights into the impact of coal mine fire-related PM2.5 on lung function.

Wildfire particulate matter may be more harmful than equivalent exposures to urban background PM2.5.40 Based on previous Hazelwood Health Study findings21 41 42 and our current research, this could also apply to coal mine fire PM2.5. The WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines provide recommendations on air quality levels and interim targets for six key air pollutants.43 However, they do not take into account variations in PM2.5 toxicity from different emission sources or the pattern or exposure, such as acute high-intensity compared with chronic exposure. Assessing the relative impact of PM2.5 exposure from landscape fires, such as coal mine fires, relative to other PM2.5 exposure, such as exhaust emissions, is a pressing public health concern, particularly in the face of global warming and increased frequency and severity of prolonged landscape fires of all kinds. Public health policy should consider the different toxicity of PM2.5 emission sources when formulating recommendations and guidelines and planning appropriate public health responses for future episodes.

Strengths and limitations

This study has many strengths. The sample was drawn from a population-based survey. This research has used various objective measures of lung function (spirometry, gas transfer and oscillometry) to evaluate respiratory health. To date, most observational studies have typically relied on secondary data sets; for example, hospitalisations.40 With a second round of data collection, we were able to conduct a longitudinal analysis of the impact of PM2.5 exposure on changes in lung function. The models adjusted for relevant confounders, including smoking. A further strength was use of individual mine fire-related PM2.5 exposure estimates from high-resolution chemical transport models and time-location diaries.

Limitations of this study include attrition over the 3-year follow-up period. The participation rate in round 2 was affected by movement restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. However, non-participants were not significantly different from those lost to follow-up, apart from current smoking, which has been frequently observed. It is possible that the reversal of associations with PM2.5 could represent loss of statistical power. Wide CIs also indicate statistical uncertainty possibly due to small sample sizes. We did not have individual level PM2.5 exposure data from the ‘Black Summer’ wildfires nor individual ambient/background PM2.5 data. However, examination of annual ambient PM2.5 levels between 2009 and 2022, and hourly PM2.5 levels during the 2019–2020 wildfires, suggested no evidence of different exposures between the two towns of Morwell and Sale.44 Finally, the analysis conducted multiple comparisons and may contain chance findings.

Conclusions

The attenuated association between PM2.5 exposure and respiratory function measures may indicate some long-term recovery in lung function following medium-term adverse effects. Our study highlighted that oscillometry has an important adjunct role to spirometry in the detection of early changes in lung mechanics associated with environmental and occupational exposures. With climate change driving increased frequency and severity of prolonged landscape fires which burn for weeks to months, as the Hazelwood coal mine fire did, these results inform public health policies and planning for future events. Further studies are required to confirm the findings and better understand the longer-term respiratory consequences of PM2.5 exposure from landscape fire smoke.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The Respiratory Stream clinics were set up in facilities provided by the Central Gippsland Health Service, Sale and The Healthcare Centre, Morwell. We thank Shantelle Allgood and David Poland from Monash Rural Health who oversaw all aspects of participant recruitment, and Sharon Harrison from the Monash School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine for assistance with purchasing, logistics and set up of the clinics.

Footnotes

Funding: The Hazelwood Health Study is funded by the Victorian State Government Department of Health; however, this paper presents the views of the authors and not the Department. The funding body had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee Project Number 1078 and Alfred Health Ethics Committee Project number 90/21. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data may be available from the authors but only with the permission of the overseeing ethics committees and the Victorian State Government Department of Health.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

Nicolette R Holt, Email: nicholt6@gmail.com.

Catherine L Smith, Email: catherine.l.smith@monash.edu.

Caroline X Gao, Email: caroline.gao@monash.edu.

Brigitte Borg, Email: b.borg@alfred.org.au.

Tyler Lane, Email: tyler.lane@monash.edu.

David Brown, Email: david.brown@monash.edu.

Jillian Ikin, Email: jill.blackman@monash.edu.

Annie Makar, Email: anniemakar@hotmail.com.

Thomas McCrabb, Email: T.Mccrabb@alfred.org.au.

Mikayla Thomas, Email: mikaylathomas.mt@gmail.com.

Kris Nilsen, Email: K.Nilsen@alfred.org.au.

Bruce R Thompson, Email: b.thompson@unimelb.edu.au.

Michael J Abramson, Email: michael.abramson@monash.edu.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Brauer M, Roth GA, Aravkin AY, et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2162–203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiordelisi A, Piscitelli P, Trimarco B, et al. The mechanisms of air pollution and particulate matter in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:337–47. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9606-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leikauf GD, Kim S-H, Jang A-S. Mechanisms of ultrafine particle-induced respiratory health effects. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:329–37. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0394-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IHME GBD results. 2020. https://www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/gbd-results Available.

- 5.Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoek G, Krishnan RM, Beelen R, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio- respiratory mortality: a review. Environ Health. 2013;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ. 2022;378:e069679. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu R, Yu P, Abramson MJ, et al. Wildfires, Global Climate Change, and Human Health. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2173–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2028985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilera R, Hansen K, Gershunov A, et al. Respiratory hospitalizations and wildfire smoke: a spatiotemporal analysis of an extreme firestorm in San Diego County, California. Env Epidemiol. 2020;4:e114. doi: 10.1097/ee9.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balmes JR. Where There’s Wildfire, There’s Smoke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:881–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1716846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmerson K, Reisen F, Luhar A, et al. Air quality modelling of smoke exposure from the hazelwood mine fire. 2016. https://hazelwoodhealthstudy.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1636434/hazelwood_airqualitymodelling_december2016_final.pdf Available.

- 12.Luhar AK, Emmerson KM, Reisen F, et al. Modelling smoke distribution in the vicinity of a large and prolonged fire from an open-cut coal mine. Atmos Environ (1994) 2020;229:117471. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teague B, Catford J, Hazelwood PS. Hazelwood mine fire inquiry report Victorian government. 2014. https://apo.org.au/node/41121 Available.

- 14.Gao CX, Dimitriadis C, Ikin J, et al. Impact of exposure to mine fire emitted PM2.5 on ambulance attendances: A time series analysis from the Hazelwood Health Study. Environ Res. 2021;196:110402. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y, Gao CX, Dennekamp M, et al. The association of coal mine fire smoke with hospital emergency presentations and admissions: Time series analysis of Hazelwood Health Study. Chemosphere. 2020;253 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson AL, Gao CX, Dennekamp M, et al. Coal-mine fire-related fine particulate matter and medical-service utilization in Australia: a time-series analysis from the Hazelwood Health Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:80–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson AL, Dipnall JF, Dennekamp M, et al. Fine particulate matter exposure and medication dispensing during and after a coal mine fire: A time series analysis from the Hazelwood Health Study. Environ Pollut. 2019;246:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.12.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt NR, Gao CX, Borg BM, et al. Long-term impact of coal mine fire smoke on lung mechanics in exposed adults. Respirology. 2021;26:861–8. doi: 10.1111/resp.14102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson AL, Gao CX, Dennekamp M, et al. Associations between Respiratory Health Outcomes and Coal Mine Fire PM2.5 Smoke Exposure: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4262. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikin J, Carroll MTC, Walker J, et al. Cohort Profile: The Hazelwood Health Study Adult Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;49:1777–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasad S, Gao CX, Borg B, et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults Exposed to Fine Particles from a Coal Mine Fire. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19:186–95. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202012-1544OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper BG. An update on contraindications for lung function testing. Thorax. 2011;66:714–23. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.139881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42049 Available. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e70–88. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1600016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00016-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oostveen E, MacLeod D, Lorino H, et al. The forced oscillation technique in clinical practice: methodology, recommendations and future developments. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:1026–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00089403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King GG, Bates J, Berger KI, et al. Technical standards for respiratory oscillometry. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1900753. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00753-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II Steering Committee The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1071–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00046802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, et al. Recommendations for a Standardized Pulmonary Function Report. An Official American Thoracic Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1463–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanojevic S, Graham BL, Cooper BG, et al. Official ERS technical standards: Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for the carbon monoxide transfer factor for Caucasians. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700010. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00010-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oostveen E, Boda K, van der Grinten CPM, et al. Respiratory impedance in healthy subjects: baseline values and bronchodilator response. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1513–23. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00126212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adam M, Schikowski T, Carsin AE, et al. Adult lung function and long-term air pollution exposure. ESCAPE: a multicentre cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:38–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00130014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Götschi T, Sunyer J, Chinn S, et al. Air pollution and lung function in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1349–58. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schermer T, Malbon W, Newbury W, et al. Spirometry and impulse oscillometry (IOS) for detection of respiratory abnormalities in metropolitan firefighters. Respirology. 2010;15:975–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman SM, Maslow CB, Reibman J, et al. Case-control study of lung function in World Trade Center Health Registry area residents and workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:582–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1909OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oppenheimer BW, Goldring RM, Herberg ME, et al. Distal airway function in symptomatic subjects with normal spirometry following World Trade Center dust exposure. Chest. 2007;132:1275–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilera R, Corringham T, Gershunov A, et al. Wildfire smoke impacts respiratory health more than fine particles from other sources: observational evidence from Southern California. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melody SM, Ford JB, Wills K, et al. Maternal exposure to fine particulate matter from a large coal mine fire is associated with gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Environ Res. 2020;183:108956. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimitriadis C, Gao CX, Ikin JF, et al. Exposure to mine fire related particulate matter and mortality: A time series analysis from the Hazelwood Health Study. Chemosphere. 2021;285 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization . WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lane TJ, Carroll M, Borg BM, et al. Long-term effects of extreme smoke exposure on COVID-19: A cohort study. Respirology. 2024;29:56–62. doi: 10.1111/resp.14591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.