Abstract

Background

Understanding emotional stress stability in populations is crucial because stress is a key factor in causing depression, and it worsens well-being.

Method

In this study, using repeated cross-sectional data from 149 countries from 2007 to 2021 (N = 2,450,043), we examined time trends of psychological stress in populations worldwide.

Results

Over half of the population experienced emotional stress in 20 countries, and 85% of the countries reported worse psychological stress in 2020 compared with 2008. We found that psychological well-being declined most rapidly among young people compared with other age groups. Individuals living and working in all types of locations (rural/farm, town/village, large city, and suburban areas) and employment (full-time, self-employed, part-time, and unemployed), respectively, experienced continuously worsening emotional stress when comparing three time periods (2008–2011, 2012–2019, and 2020–2021). Furthermore, reducing physical pain and increasing income were noted to be more important than solving health problems for the purpose of decreasing stress.

Conclusion

Emotional stress continuously worsened worldwide over the past few decades, but the trend varied among countries. Our findings highlight the significance of improving people’s living environments to reduce their likelihood of experiencing emotional stress.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20961-4.

Keywords: Psychological well-being, Emotional stress, COVID-19, Multination

Introduction

The increasing incidence of global mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression has been well documented, with the World Health Organization noting increasing prevalence [1]. Over the past few decades, daily emotional stress has also worsened significantly worldwide [2]. Research has consistently shown that stress is a major contributor to both mental and physical health issues, including cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancers [3, 4]. Moreover, stress negatively affects workplace productivity, with chronic stress leading to reduced job performance and substantial economic consequences for both individuals and businesses [5, 6]. Psychological stress in the workplace can result in a lifetime loss of approximately $600,000 in income per employee [7]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, as evidenced by the increasing global incidence rates of anxiety and depression during and after the crisis [8, 9].

Addressing population-level emotional stress is crucial for social and economic sustainability. This aligns with key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 3, which focuses on good health and well-being; SDG 8, which emphasizes decent work and economic growth; and SDG 11, which aims to create sustainable cities and communities. Mitigating emotional stress not only enhances public health outcomes but also improves workforce productivity and strengthens community resilience, thereby contributing to the long-term sustainability of economies and societies [10, 11].

Against this background, this study aimed to investigate historical trends in emotional stress at the global level and the potential socioeconomic factors that influence the development of population stress. We utilized data from a large-scale global survey conducted by Gallup, Inc., to measure self-reported emotional stress in 149 countries from 2008 to 2021. We emphasized variations across key demographic groups, including age, residential area, and employment status. In addition, we identified specific countries and regions where emotional stress worsened most severely and rapidly during this period. Finally, we examined the role of subjective socioeconomic factors such as perceived income level, value of hard work, and satisfaction with the educational system as significant determinants of emotional stress across different age groups to provide deeper insights into the socioeconomic drivers that influence emotional well-being trends.

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it extends the work of Daly and Macchia [2] by incorporating a more granular analysis of demographic groups to examine global variations in emotional stress. By providing detailed data on the percentage of the population that experienced stress across age groups, residential areas, and employment statuses, the study offers valuable insights into the broader impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, this study provides a better understanding of the geographic disparities in stress levels by identifying specific regions with populations experiencing severe and rapidly worsening emotional stress. Finally, we focused on subjective socioeconomic factors such as perceived financial insecurity as key determinants of psychological stress. Compared with objective socioeconomic measures, these subjective factors demonstrate stronger effects on emotional stress, which suggests that future coping strategies should prioritize addressing individuals’ perceptions of their socioeconomic conditions to mitigate psychological stress more effectively.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The literature review section discusses previous research on individuals’ negative emotions around the world. The method section explains all the study procedures, and the subsequent. The results and discussion sections present our main findings, and the final section concludes the paper.

Literature review

Worsening global mental health and disparities in access to care are rooted in multiple social, cultural, and economic factors, including poverty, inequality, lack of education and employment opportunities, discrimination, and limited access to resources [12]. Culturally, the widespread stigma surrounding mental illness is a significant barrier to improving global mental health. In many countries, including China, India, Kenya, Romania, Egypt, and the USA, individuals with severe psychiatric disorders are often subjected to significant stigma [13].

Several studies and surveys have focused on daily emotional well-being and mental health [2, 14–41]. Daily emotional stress has also worsened significantly worldwide over the past few decades [2]. DeLongis et al. [14] reported that daily emotional stress has a negative effect on individuals’ health, including worsening headaches, backaches, sore throat, and flu. Moreover, income inequality may also be a determinant of mental illness [20]. In high- and upper-middle-income countries, significantly reduced household income is associated with early onset mental disorders, with this association being stronger for women compared with men [19]. Research suggests that social integration, measured as active participation in the community and civic life, can facilitate the advancement of community mental health services [21]. Specifically, community components play a critical role in addressing global mental health needs and reducing disparities in access to care and support [22].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on mental health services globally [23], particularly in low- and middle-income countries where care systems are already fragile and fragmented [24]. Successful digital delivery of healthcare in high-income countries could be a cost-effective way to enhance health care systems in low- and middle-income countries [25]. However, the rapid spread of COVID-19 has disrupted entire industries and led to widespread job loss and economic insecurity, resulting in severe occupational stress [26]. Workers in essential industries such as healthcare and frontline services are at an increased risk of exposure to COVID-19. Employment instability and the subjective terms of job insecurity and emotional precariousness have affected workers across the EU [27]. Simultaneously, the shift to remote work and closure of many physical workplaces have brought new challenges such as isolation, burnout, and reduced access to support services [28].

The relationships between the individuals experiencing psychological stress and their characteristics have been investigated in previous studies [14, 29–34]. In the working environment, the working demand that individuals should work hard worse individuals' stress [33, 34]. Physical pain, such as headache or backpack pain, is negatively associated with daily emotional stress [14]. Education attainment has a complex relationship with stress in different age groups [29, 31]. The improvement in household income has a favorable effect on reducing stress [30, 32].

We aimed to provide a comprehensive picture of psychological stress in the global population that depicts several aspects. First, this paper presents the percentage of people worldwide who experienced emotional stress between 2007 and 2021 on the basis of the world stress data collected by Gallup, Inc., with 2,450,043 valid observations. Furthermore, we show the time trends in emotional stress based on different factors, including age, living area, and employment status. Moreover, we aim to present the universality of and variation in the continuously worsening population stress in each of the 149 countries and regions, using self-reported psychological stress measurements, and to identify populations with rapidly worsening emotional stress. Finally, socioeconomic characteristics and health factors will be investigated as determinants of psychological and emotional stress.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, investigations of the global trends in emotional stress during the past decades are expected to provide a better understanding of the global emotional stress viewpoint. Furthermore, demonstrating psychological stress in the global population during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with that before the pandemic might clarify the effects of the pandemic in terms of changes in global psychological stress. Moreover, to present the psychological well-being of the population worldwide, data on individual-level distress status were collected from 2,450,043 valid responses, providing a more reliable investigation and avoiding the small sample problem. Finally, the associations between economic, social, and health factors and population psychological stress are demonstrated, and the results are expected to help reduce emotional stress.

Methods

The global repeated cross-sectional data used in this study were derived from 149 countries and regions ranged between, collected by the Gallup World Poll between 2007 to 2021, see Table A1 for each year. A representative sample covers 98% of the global population, the Table 1 displayed the list of the countries. A random sampling method was adopted for each country to enhance the nationally representative data. Face-to-face survey and telephone interviews are adopted; face-to-face surveys lasted approximately one hour and telephone interviews lasted approximately half an hour. Repeated cross-sectional surveys were conducted annually in several countries. In total, the repeated cross-sectional survey data from 149 countries and regions, with 2,450,043 valid responses. Detailed information regarding the interview is provided in the Gallup 2013 and Gallup 2021 [31, 32]. The cross-sectional survey was annually conducted by Gallup, Inc., with the sample size of the observations ranging between 112,075–141,936 worldwide. For the specific targeted nation, the observations ranged between 5000–70,416 for each country, to avoid problems caused by small sample sizes.

Table 1.

The number of the observations by country/region

| Country Name | No. obs | Country Name | No. obs | Country Name | No. obs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 15,137 | Guatemala | 14,150 | Northern Cyprus | 7,056 |

| Albania | 15,149 | Guinea | 11,153 | Norway | 13,042 |

| Algeria | 12,165 | Guyana | 501 | Oman | 2,016 |

| Angola | 4,000 | Haiti | 5,537 | Pakistan | 22,842 |

| Argentina | 16,060 | Honduras | 15,009 | Palestine | 18,104 |

| Armenia | 15,082 | Hong Kong | 12,141 | Panama | 15,111 |

| Australia | 16,286 | Hungary | 15,172 | Paraguay | 16,081 |

| Austria | 16,035 | Iceland | 5,136 | Peru | 16,006 |

| Azerbaijan | 14,080 | India | 69,530 | Philippines | 18,290 |

| Bahrain | 15,324 | Indonesia | 19,707 | Poland | 16,120 |

| Bangladesh | 20,333 | Iran | 17,944 | Portugal | 16,095 |

| Belarus | 14,829 | Iraq | 19,123 | Puerto Rico | 1,000 |

| Belgium | 16,132 | Ireland | 15,527 | Qatar | 7,060 |

| Belize | 1,006 | Israel | 16,167 | Romania | 15,122 |

| Benin | 13,042 | Italy | 18,064 | Russia | 37,047 |

| Bhutan | 3,040 | Ivory Coast | 10,029 | Rwanda | 12,504 |

| Bolivia | 16,008 | Jamaica | 4,069 | Saudi Arabia | 21,533 |

| Bosnia Herzegovina | 16,119 | Japan | 20,214 | Senegal | 16,000 |

| Botswana | 12,116 | Jordan | 20,066 | Serbia | 15,700 |

| Brazil | 19,243 | Kazakhstan | 16,080 | Sierra Leone | 13,149 |

| Bulgaria | 14,095 | Kenya | 17,209 | Singapore | 15,692 |

| Burkina Faso | 15,015 | Kosovo | 15,270 | Slovakia | 13,132 |

| Burundi | 5,000 | Kuwait | 16,050 | Slovenia | 14,562 |

| Cambodia | 16,626 | Kyrgyzstan | 16,081 | Somalia | 3,191 |

| Cameroon | 16,200 | Laos | 11,575 | Somaliland | 7,000 |

| Canada | 18,536 | Latvia | 14,195 | South Africa | 17,112 |

| Central African Republic | 5,000 | Lebanon | 20,143 | South Korea | 18,138 |

| Chad | 14,111 | Lesotho | 4,000 | South Sudan | 4,000 |

| Chile | 16,348 | Liberia | 11,000 | Spain | 18,056 |

| China | 70,416 | Libya | 6,060 | Sri Lanka | 16,549 |

| Colombia | 16,000 | Lithuania | 15,120 | Sudan | 7,592 |

| Comoros | 9,000 | Luxembourg | 11,028 | Suriname | 504 |

| Congo Brazzaville | 12,092 | Madagascar | 11,016 | Sweden | 16,798 |

| Congo Kinshasa | 8,000 | Malawi | 13,000 | Switzerland | 11,539 |

| Costa Rica | 16,011 | Malaysia | 15,326 | Syria | 11,452 |

| Croatia | 15,152 | Maldives | 1,000 | Taiwan | 15,033 |

| Cuba | 1,000 | Mali | 15,130 | Tajikistan | 18,080 |

| Cyprus | 13,648 | Malta | 13,093 | Tanzania | 16,017 |

| Czech Republic | 14,181 | Mauritania | 16,092 | Thailand | 18,479 |

| Denmark | 16,515 | Mauritius | 8,059 | Togo | 10,130 |

| Djibouti | 5,000 | Mexico | 17,099 | Trinidad and Tobago | 2,522 |

| Dominican Republic | 16,079 | Moldova | 16,080 | Tunisia | 16,293 |

| Ecuador | 16,135 | Mongolia | 14,070 | Turkey | 19,065 |

| Egypt | 26,998 | Montenegro | 13,921 | Turkmenistan | 10,089 |

| El Salvador | 16,089 | Morocco | 14,101 | Uganda | 16,016 |

| Estonia | 14,338 | Mozambique | 9,000 | Ukraine | 16,404 |

| Eswatini | 3,110 | Myanmar | 10,800 | United Arab Emirates | 24,995 |

| Ethiopia | 11,229 | Nagorno Karabakh | 1,000 | United Kingdom | 38,676 |

| Finland | 14,796 | Namibia | 7,008 | United States | 18,499 |

| France | 18,014 | Nepal | 18,202 | Uruguay | 16,103 |

| Gabon | 11,086 | Netherlands | 15,795 | Uzbekistan | 15,080 |

| Gambia | 3,120 | New Zealand | 14,844 | Venezuela | 16,080 |

| Georgia | 16,164 | Nicaragua | 16,108 | Vietnam | 18,155 |

| Germany | 42,419 | Niger | 14,016 | Yemen | 16,140 |

| Ghana | 16,018 | Nigeria | 19,006 | Zambia | 15,027 |

| Greece | 15,093 | North Macedonia | 15,300 | Zimbabwe | 16,086 |

The self-reported emotional stress approach was applied to measure individuals’ stress status in 149 countries by asking the respondents whether they experienced stress the previous day. Among the populations studied, the age groups include young-, middle-, and older-aged individuals; the living areas include rural/farm, small town/village, large city, and suburb of a large city; and employment status includes employed full-time for an employer, employed full-time for self, employed part-time do not want full-time, unemployed, employed part-time want full-time, and out of the workforce.

Variable setting

Emotional stress

The psychological stress, also denoted as emotional stress in this study, was measured through self-report, by asking the respondents whether they had experienced stress yesterday, with the choices being “1 = yes” and “0 = no.” Furthermore, the demographic and socioeconomic background of the targetted individuals are divided as follows. The six employment status types were employed full-time for an employer, employed full-time for self, employed part-time do not want full-time, unemployed, employed part-time want full-time, and out of the workforce. The respondents’ living areas were categorized as rural/farm, small town/village, large city, and suburb of a large city; to reduce missing values for respondents’ living status, an alternative was applied as “don’t know” or “refused.” Data were collected from respondents between the ages of 17 and 99.

Emotional stress determinant characteristics

(1) Physical pain experience was used as a dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent felt physical pain, and 0 otherwise. (2) Another dummy variable was health problems, which was equal to 1 if the individual had a health problem, and 0 otherwise. (3) Education system dissatisfaction was a dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent reported feeling dissatisfied with the education system, and 0 otherwise. Education attainment includes primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education. (4) Household size was a categorical variable ranging from 1 to 32, with a larger number indicating a larger household size. (5) “Should work hard” was a dummy variable equaling 1 if the individual answered that he/she should work hard, and 0 otherwise.

Respondents’ subjective feelings about household income were measured by asking whether they were living comfortably based on their present income: living comfortably on the present income = 1, getting by on the present income = 2, finding it difficult on the present income = 3, and finding it very difficult on the present income = 4. Per capita income quintiles reflected the reconstructed household income levels, ranging between 1 to 5, with higher numbers indicating higher household income: 20% was defined as the poorest group = 1, the second 20% poorest group = 2, the middle 20% income level = 3, the fourth 20% income level = 4, and the richest 20% group = 5.

(6) The food and shelter index was described according to Gallup, Inc., as follows: “it assesses the ability people have to meet basic needs for food and shelter. Lower scores on this index indicate that more respondents reported struggling to afford food and shelter in the past year, while higher scores indicate fewer respondents reported such struggles.” (7) The communications index reflected people’s social connections via electronic communications by asking the respondents whether they had a landline telephone or mobile phone to make and receive personal calls and whether their homes had Internet access. (8) The civic engagement index measured individuals’ inclination to volunteer about their and assistance to other situations. This index measured individuals’ commitment to their current community. For this, the survey asked about respondents’ donations to charity or time spent volunteering for an organization or helping a stranger.

Methodology

Comprehensive repeated cross-sectional worldwide individual-level data were applied to present the global trends in and characteristics of the population’s emotional stress. The population stress trends from 2007 to 2021 and the repeated cross-sectional Internet survey data were derived from 149 countries and regions, with 2,450,043 total valid responses. The determinant characteristics were estimated using a logit model, as shown in Eq. (1). Logit, probit, and linear probability models were considered appropriate when the dependent variable was a dummy variable indicting whether an individual experienced stress. The logit model is shown in the major results, whereas the probit and linear probability models were used to confirm that the results are robust.

| 1 |

where denotes the probability of an individual in a country experiencing daily emotional stress. In the survey, the variable measures the respondents’ emotional stress as a dummy variable. If a respondent experienced emotional stress on the during the previous day, it equals 1; otherwise, it equals 0. is a set of variables, including individuals’ demographics and socioeconomic backgrounds. is a set of variables describing an individual’s overall well-being. is a constant term, and and are the vectors of the parameters. To measure the fit of the regression model, pseudo R-squared and likelihood-ratio tests were used. All regressions were performed using Stata 16.

Results

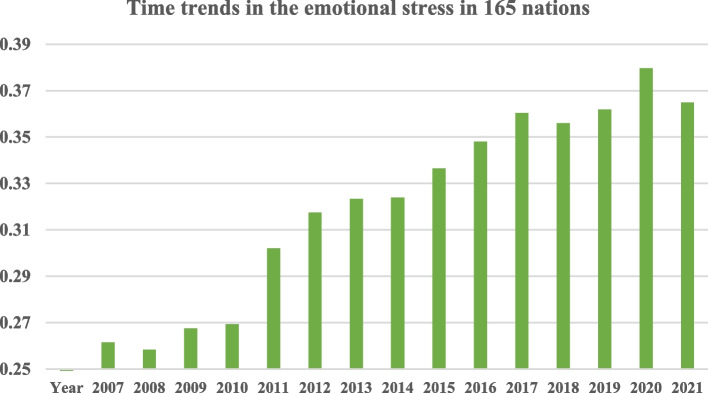

Figure 1 shows the increasing share of individuals who had experienced emotional stress the day before the survey from 2007 to 2021. In 2007, approximately 26% of individuals reported experiencing emotional stress; however, the share of the population experiencing stress continuously increased, reaching approximately 38% in 2020. During and after the 2008–2011 finance crisis, on average, approximately 28% of the respondents reported experiencing emotional stress the day prior to the crisis. However, from 2012 to 2019, on average, approximately 36% of the respondents experienced stressed, and, moreover, 37% of the respondents reported experiencing emotional stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding global trends in emotional stress, the results showed that population emotional stress continuously worsened between 2007 to 2021.

Fig. 1.

Time trends of emotional stress in 149 countries and regions from 2007 to 2021. Note: The stress data were derived from 149 countries and regions (N = 2,450,043). Emotional stress was measured through self-report, by asking the respondents whether they had experienced stress yesterday, with the choices being “1 = yes” and “0 = no”

Figure 2 displays a world map of the percentage of the population experiencing emotional stress in 149 countries and regions. Panel (A) presents the population’s emotional stress during–2008–2011, whereas Panels (B) and (C) show the percentage of the population experiencing stress from 2012 to 2019 and 2020 to 2021.

Fig. 2.

Individuals’ emotional stress status distribution worldwide. Data sources: The World Internet Survey was conducted by Gallup, Inc., from 2007 to 2021. Emotional stress was measured through self-report, by asking the respondents whether they had experienced stress yesterday, with the choices being “1 = yes” and “0 = no”

Comparing the emotional stress in the three periods, the populations of various countries have increasingly experienced emotional stress, and individuals experienced the worst emotional stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared to the emotional stress during the 2008 financial crisis, only 18 countries showed an improvement in psychological well-being: Algeria, Austria, Bahrain, Cyprus, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Latvia, Mauritius, New Zealand, Philippines, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. In contrast, approximately 85% of all countries showed worsening population emotional stress compared to the population emotional stress status in the 2008 financial crises. On average, compared to the emotional stressful experienced in 2008, psychological stress increased by 12.5% in the population of each country during the pandemic. These increases in emotional stress varied in magnitude, and the rapidly worsening countries are Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, China, Congo Brazzaville, Ecuador, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Mali, Peru, Senegal, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Venezuela, and Zambia. People in developing nations were more likely to experience psychological stress, and the rapid increase in the number of people experiencing psychological stress is remarkable.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of the population experiencing emotional stress in different groups for–2008–2011, 2012–2019, and 2020–2021. The percentage of participants who reported experiencing emotional stress one day prior is summarized by age group (A), living area (B), and employment status (C).

Fig. 3.

Population emotional stress trends in different groups. Note: Data sources: A survey of 149 countries and regions from 2007 to 2021, conducted by Gallup, Inc. Table A2 and Table A3 displayed the description statistics. Emotional stress was measured through self-report, by asking the respondents whether they had experienced stress yesterday, with the choices being “1 = yes” and “0 = no”

Among the different age groups, young-aged individuals showed a rapid time trend of worsening emotional stress. Individuals in the 17–23 and 24–45 age groups experienced significant rapid stress worsening when comparing the periods during the 2008 financial crisis, 2012–2019, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021. Compared to the other age groups, in–2002–2019, older-aged individuals (over 60 years of age) experienced the most stress, whereas during the COVID-19 pandemic, the young-aged group experienced the worst emotional stress. Notably, from 2008 to 2011, on average, less than 30% of the respondents reported experiencing psychological stress among all age groups; however, from 2020 to 2021, all age groups experienced moderate stress levels over 30%. Moreover, young-aged people showed rapid worsening in terms of psychological stress.

Individuals in all types of living areas, including rural/farm, town/village, large city, and suburban areas, experienced continuously worsening emotional stress when comparing the three time periods of 2008–2011, 2012–2019, and 2020–2021. The results indicate that individuals showed the worst emotional stress during the pandemic period and the best during the 2008 financial crisis. Notably, individuals living in rural areas, on farms, in towns, and in villages showed the most rapid worsening of emotional stress compared to individuals living in large cities and suburban areas. From 2008 to 2011, individuals living in large cities and suburban areas experienced the most stress; however, from 2020 to 2021, those living in rural areas or on farms experienced the most stress.

Regarding employment status, comparing stress levels in 2008, 2012, and 2020, the results showed that individuals with each employment type, including full-time, self-employment, part-time, unemployed, part-time (want full-time employment), and the out of the workforce, appeared the least emotionally stressed in 2008 and the most stressed in 2020. On average, over one-third of the respondents experienced emotional stress between 2020–2021.

Table 2 presents the shares of individuals experiencing stress in the overall population of 127 countries and regions from 2020 to 2021, displayed in order starting from the worst.

Table 2.

Ratio of stressful people to total population in each country from 2020 to 2021

| Country name | Feel emotional stress | Rank | Country name | Feel emotional stress | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 74.7 | 1 | Belgium | 35.3 | 63 |

| Lebanon | 66.3 | 2 | Japan | 35.1 | 64 |

| Turkey | 63.2 | 3 | South Korea | 35.0 | 65 |

| Ecuador | 60.0 | 4 | Kosovo | 34.9 | 66 |

| Greece | 59.7 | 5 | Australia | 34.7 | 67 |

| Jordan | 57.6 | 6 | Bulgaria | 34.6 | 68 |

| Peru | 57.4 | 7 | United Arab Emirates | 34.5 | 69 |

| Tanzania | 55.2 | 8 | United Kingdom | 34.5 | 70 |

| Egypt | 53.3 | 9 | Bangladesh | 34.4 | 71 |

| China | 52.9 | 10 | Myanmar | 34.4 | 72 |

| Tunisia | 52.3 | 11 | Slovakia | 34.3 | 73 |

| Iraq | 52.0 | 12 | Finland | 34.0 | 74 |

| Albania | 51.7 | 13 | Singapore | 33.8 | 75 |

| Costa Rica | 51.5 | 14 | Jamaica | 33.8 | 76 |

| Uganda | 51.3 | 15 | Montenegro | 33.8 | 77 |

| El Salvador | 51.3 | 16 | Nepal | 33.6 | 78 |

| Venezuela | 51.1 | 17 | Romania | 33.6 | 79 |

| Bolivia | 51.0 | 18 | Paraguay | 33.5 | 80 |

| Sierra Leone | 50.9 | 19 | Bosnia Herzegovina | 33.5 | 81 |

| Dominican Republic | 50.1 | 20 | Czech Republic | 33.2 | 82 |

| Malta | 49.5 | 21 | Israel | 33.1 | 83 |

| Cyprus | 49.5 | 22 | Armenia | 33.0 | 84 |

| Ghana | 49.4 | 23 | Morocco | 33.0 | 85 |

| Iran | 49.3 | 24 | Serbia | 32.8 | 86 |

| Mexico | 48.5 | 25 | Panama | 32.6 | 87 |

| Colombia | 48.5 | 26 | Hungary | 32.5 | 88 |

| Philippines | 48.3 | 27 | Spain | 32.3 | 89 |

| Sri Lanka | 48.2 | 28 | Ivory Coast | 32.0 | 90 |

| Senegal | 47.2 | 29 | Mozambique | 31.9 | 91 |

| United States | 46.6 | 30 | Iceland | 31.7 | 92 |

| Canada | 46.4 | 31 | Slovenia | 31.5 | 93 |

| Brazil | 46.0 | 32 | Pakistan | 31.2 | 94 |

| Zambia | 44.4 | 33 | New Zealand | 31.0 | 95 |

| Cameroon | 44.3 | 34 | Norway | 30.8 | 96 |

| Burkina Faso | 44.0 | 35 | Switzerland | 30.3 | 97 |

| Thailand | 43.6 | 36 | India | 29.7 | 98 |

| Nigeria | 43.5 | 37 | Germany | 29.5 | 99 |

| Honduras | 43.2 | 38 | Malaysia | 29.5 | 100 |

| Cambodia | 42.9 | 39 | Taiwan | 29.2 | 101 |

| Nicaragua | 42.7 | 40 | Algeria | 29.1 | 102 |

| Chile | 42.3 | 41 | Namibia | 28.6 | 103 |

| Argentina | 41.9 | 42 | Benin | 28.4 | 104 |

| Portugal | 41.2 | 43 | Laos | 28.4 | 105 |

| Hong Kong | 40.8 | 44 | Estonia | 28.3 | 106 |

| Italy | 40.3 | 45 | Austria | 28.3 | 107 |

| Poland | 40.3 | 46 | Sweden | 27.8 | 108 |

| Uruguay | 39.8 | 47 | Saudi Arabia | 27.8 | 109 |

| Zimbabwe | 39.6 | 48 | Georgia | 27.4 | 110 |

| Ireland | 39.1 | 49 | Malawi | 25.9 | 111 |

| Croatia | 39.0 | 50 | Latvia | 25.4 | 112 |

| Vietnam | 38.9 | 51 | Ethiopia | 25.1 | 113 |

| Congo Brazzaville | 38.8 | 52 | Lithuania | 25.0 | 114 |

| North Macedonia | 37.9 | 53 | Moldova | 23.8 | 115 |

| Tajikistan | 37.1 | 54 | Ukraine | 22.9 | 116 |

| Kenya | 36.8 | 55 | Netherlands | 22.8 | 117 |

| Gabon | 36.5 | 56 | Denmark | 21.8 | 118 |

| Mali | 36.5 | 57 | Russia | 19.1 | 119 |

| Guinea | 36.4 | 58 | Indonesia | 18.8 | 120 |

| France | 36.3 | 59 | Mongolia | 18.7 | 121 |

| Togo | 35.9 | 60 | Mauritius | 18.3 | 122 |

| South Africa | 35.6 | 61 | Uzbekistan | 15.2 | 123 |

| Bahrain | 35.5 | 62 | Kazakhstan | 15.1 | 124 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 13.6 | 125 |

The data were collected via face-to-face and telephone interview surveys by Gallup, Inc. from 2020 to 2021

Overall, over half of the population reported experiencing emotional stress in 20 countries: Afghanistan, Lebanon, Turkey, Ecuador, Greece, Jordan, Peru, Tanzania, Egypt, China, Tunisia, Iraq, Albania, Costa Rica, Uganda, El Salvador, Venezuela, Bolivia, Sierra Leone, and the Dominican Republic. These countries showed a high ratio of psychological stress within the population, which might be caused by numerous characteristics that could threaten citizens’ generalized living environment, such as social security, economic status, and strict social movement management caused by COVID-19.

Approximately 30–50% of the population experienced psychological stress in 77 countries, including developing countries and major developed countries, such as the United States, Japan, and France. Notably, the countries with the least number of people experiencing psychological stress (i.e., less than 20% of the population), are developing rather than developed nations, such as Russia, Indonesia, Mongolia, Mauritius, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. In these places, although the country is developing, families might be able to afford daily expenses without stress. Psychological stress may worsen with economic development, while stressful experiences are more strongly influenced by a safe social environment and fewer negative experiences.

Table 3 shows the regression results on the psychological stress determinant characteristics using the logit model based on global stress data from 2008 to 2021. The marginal effects of the determinant factors are presented by age group. The ages for each group range from 13–24 years, 24–45 years, 46–60 years, 61–75 years, and 76 years, whereas the ages ranged from 13–23 years in columns 1 to 5.

Table 3.

Determinant characteristics of respondents’ daily emotional stress

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 ~ 23 | 24 ~ 45 | 46 ~ 60 | 61 ~ 75 | 76 ~ | |

| Physical pain experience | 0.186*** | 0.210*** | 0.198*** | 0.163*** | 0.135*** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.006) | |

| Health problem | 0.025*** | 0.026*** | 0.015*** | 0.021*** | 0.023*** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.006) | |

| Household size | -0.006*** | -0.008*** | -0.005*** | -0.000 | 0.003** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Education system dissatisfaction | 0.037*** | 0.029*** | 0.031*** | 0.032*** | 0.039*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.006) | |

| Feel about income | 0.024*** | 0.048*** | 0.062*** | 0.056*** | 0.055*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Should work hard | -0.024*** | -0.033*** | -0.021*** | -0.021*** | -0.031*** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.007) | |

| Food and Shelter index | -0.001*** | -0.001*** | -0.001*** | -0.001*** | -0.001*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Communication index | 0.001*** | 0.002*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Civic engagement index | 0.001*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Per capita income quintiles | -0.011*** | -0.012*** | -0.006*** | 0.001 | -0.002 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Reference (primary education) | |||||

| Secondary | 0.034*** | 0.020*** | -0.003 | -0.035*** | -0.016** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.007) | |

| Tertiary | 0.063*** | 0.055*** | 0.027*** | -0.019*** | -0.005 |

| (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.010) | |

| Women | 0.020*** | 0.005*** | 0.003 | 0.017*** | 0.025*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.006) | |

| Observations | 148,648 | 359,347 | 164,479 | 87,872 | 22,428 |

| LR chi2(13) | 9074.33 | 26680.26 | 12572.33 | 7486.49 | 1797.95 |

| Prob > chi2 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0535 | 0.0584 | 0.0602 | 0.0744 | 0.0734 |

Standard errors are in parentheses. The coefficients (marginal effects) of the determinant factors are presented by age group

***p < 0.01

**p < 0.05

Physical pain had the greatest impact on individuals’ psychological stress. The coefficients for physical pain experience were positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. This shows that people with physical pain are more likely to report experiencing psychological stress. The magnitudes of the coefficients ranged between 0.144 to 0.198 among the age groups. The results suggest that, on average, individuals with physical pain show 14.4–19.8% higher experience of psychological stress. This indicates that if the control or release of physical pain has a large favorable effect and will reduce individuals’ stress levels. Health problems consistently worsened individuals’ psychological stress in each age group. The coefficient of health problems was positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that people with health problems have worse psychological well-being. However, the magnitude of the impact of health status was much smaller than that of physical pain.

The young-aged group preferred a small household member size; however, there was no significant effect of household size. A small-sized family results in better psychological well-being for individuals aged between 13–60 years. These results differ from those of the older-age group. This might be because older people need to rely on younger family members in their daily lives. The employee should work hard shows the less psychological stressful on the people. The coefficients for work hard were negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that people experience less emotional stress if they feel they should work hard in their lives.

Whether individuals had the financial ability to meet their daily expenses had a significant effect on respondents’ psychological well-being and whether they experienced emotional stress. The coefficient for subjective feelings about household income showed it had a significant effect on individuals’ emotional stress. Among the age groups, although the young aged, and old aged people experienced when they had difficulties meeting their expenses on the present income. Middle-aged people were more likely to experience a subjective financial problems when they experienced financial difficulties, and were 24.4% more likely to experience emotional stress compare to people who could live comfortably on their current income. Regarding objective household income levels, the per capita income quintiles were consistently negative and statistically significant for the young- and middle-aged groups. This suggests that objective income level affects people in the young and middle-aged groups, indicating that families in a higher quartile for household income are less likely to experience emotional stress. Comparing the magnitudes of the impact of financial status on individual psychological well-being, the magnitude of the coefficients for subjective feelings about income were much greater than the objective measurement based on the per capita income quintiles. The results suggest that subjective measurement of an individual’s satisfaction with their income is more crucial than objective measurement of household income status.

Satisfaction with the educational system showed a significant effect on psychological well-being. The coefficients were all positive and statistically significant, showing that dissatisfaction with the current educational system worsens psychological well-being across all age groups. The coefficients for working hard were negative across all age groups, suggesting that the people with the value of hard working experience less emotional stress. The gender differences in experiencing emotional stress are confirmed in the regression results. The women's age coefficients were positive for the following age ranges, with the statistical significance set at 1%: 13–23, 24–45, 61–75, and ≥ 76 years. The results suggest that the women tended to experience higher emotional stress levels than the men. Regarding educational attainment, the effects of educational attainment on emotional stress.

Finally, the results showed that multiple comprehensive social connections had complex effects on individuals’ emotional stress. The lower the food and shelter index, the worse the affordability of food and shelter, and this showed a significant effect on individuals’ emotional stress. Individuals’ comprehensive communication networks showed a statistically significant favorable effect on psychological well-being. Moreover, the civic engagement index showed that the more involve individuals were in civic engagement, they more likely they were to experience stress.

Discussion

On the basis of a large-scale longitudinal survey across 149 countries and regions, this study investigated the historical change of emotional stress across demographic groups, including age, living area, and employment status. Moreover, we identified countries with populations experiencing high levels of and rapidly worsening emotional stress. In this section, we mainly discuss the results in three ways.

First, the study shows a global trend of continuously worsening emotional stress from 2007 to 2021, aligning with and extending the findings of Almeida et al. [37], who documented similar trends in the United States during the 1990s and 2010s. This trend has been continually observed across multiple countries and regions, suggesting that the increase in emotional stress is not confined to specific locations but reflects a broader global pattern. During the observation period, the COVID-19 pandemic created a significant global shock [2], amplifying emotional stress across various demographic groups. Younger individuals, those living in rural areas, and people with unstable employment experienced the highest levels of vulnerability. Our findings on age-related emotional stress revealed a pattern divergent from those observed in previous studies. Almeida et al. [38] suggested that advancing age generally confers a protective effect against daily stress, with older individuals experiencing lower levels of emotional strain than their younger counterparts. However, the present study demonstrates an opposing trend in which emotional stress appeared to increase with age, particularly during periods of global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that the cumulative challenges posed by large-scale disruptions might have undermined the typically observed age-related resilience to stress. These findings underscore the need to reexamine the impacts of global shocks on emotional well-being across age groups, challenging established assumptions regarding stress and aging trajectories.

Second, our findings suggest that psychological distress has become a widespread issue, with notable heterogeneity across countries and regions in the past decades. Situations that cause severe emotional stress (i.e., more than half of the population reported that they experienced emotional stress the day before) were observed in 20 countries (see Table 2), highlighting the urgent need for targeted mental health interventions and support systems in these regions. Perceived daily emotional stress is likely to lead to stress-induced social avoidance, as noted by daSilva et al. [39]. In regions where this behavior is prevalent, reduced social interactions can further exacerbate social and economic challenges. In 77 countries, approximately 30–50% of the population reported experiencing psychological stress. Furthermore, 85% of the countries reported worsening psychological stress over the past decades, indicating that a significant portion of the global population is struggling with increasing mental health challenges.

Third, our findings highlight several key determinants of emotional stress. A particularly strong factor is physical pain, which was found to significantly worsen psychological well-being across all age groups. Individuals experiencing physical pain were 25% more likely to report psychological stress, consistent with a previous report [40], and this effect was almost ten times greater than that of health problems. Furthermore, several subjective eco-social factors have shown significant impacts on emotional stress, such as perceived household financial status and dissatisfaction with the educational system. Subjective household income level is more likely to influence psychological well-being than objective income level, which suggests that more attention should be paid to people experiencing subjective poverty [41]. Similarly, dissatisfaction with societal institutions such as the educational system can lead to increased frustration and stress, especially when individuals perceive that these systems fail to provide adequate opportunities for advancement or stability. These factors emphasize the importance of addressing broader social inequalities and perceived inadequacies in public services to mitigate emotional stress. Health problems or physical pain experiences are negatively associated with stress, and the results are consistent with those of previous studies [14]. The greater workload is more likely associated with experiencing daily emotional stress; the results are consistent with the previous studies [33, 34]. Moreover, household income improvement or higher per capita income quantile has favorable effects on reducing individuals’ emotional stress, and the results are in line with the previous studies [30, 32].

Conclusion

Using large-scale repeated cross-sectional data collected between 2007 and 2021 from 149 countries and regions (N = 2,450,043), this study examined the trends, demographic variations, and subjective determinants of emotional stress across populations. The findings show a global increase in the incidence of emotional stress over the past few decades, including the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results underscore the critical role of subjective socioeconomic factors in shaping individuals' emotional stress levels.

Furthermore, the findings suggest several key policy implications. First, targeted mental health interventions should be developed for vulnerable groups such as those experiencing physical pain or financial insecurity, as these groups are disproportionately affected by emotional stress. Second, social safety nets, particularly in areas such as income security, education, and health-care access, should be strengthened to alleviate the socioeconomic pressures that contribute to heightened stress levels. Finally, resilience-building programs that address mental health in the wake of global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic should be integrated into economic recovery plans to foster long-term emotional well-being and societal stability.

The limitations are acknowledged as follows. In the measurement of stress, this study applied daily emotional stress, which may be different from long-term stress (e.g., longer than 2 weeks) as adopted in the major depression measurement developed by the World Health Organization. Although the negative relationship between headache or backache and daily emotional stress was confirmed in a previous study, further study is needed to clarify the relationship between daily emotional distress and health status. Moreover, further studies on long-term stress measurement and investigations of the negative impacts of stress on health are recommended.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

Xiangdan Piao conducted the analysis, prepared the primary manuscript and participated the manuscript revision. Xie Jun prepared the primary manuscript and participated the manuscript revision. The Shunsuke Managi made the data available.

Funding

This work was supported by JST-MiraiProgram Grant Number JPMJMI22I4, Japan and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP20H00648 and JP24K16420. This research is funded by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number Grant Number 23K17082.). This research was supported by Support for research activities through the Women’s Activity Transformation Program 2023 Iwate University. This research is supported by the Tohoku Initiative for Fostering Global Researchers for Interdisciplinary Sciences (TI-FRIS).

Data availability

The data are publicly unavailable; Gallup, Inc. provided data access permission and other de-identified data for the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey is designed by the Gallup Inc. and the datasets are collected by the Gallup Inc. The data applied in this study is that the Urban Institute of the Kyushu University purchased the world stress data collected by a third-party company (Gallup, Inc.) between 2007 to 2021, the study design was approved by the appropriate legal and ethics review board of Kyushu University. All the methods proceeded in accordance with ethical guidelines and were approved by the ethical committee of Kyushu University.

The data were collected with informed consent from participants by Gallup Inc., meeting the legal and ethical guidelines of Kyushu University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Global burden of mental disorders and the need for comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level. 2011. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB130/B130_9-en.pdf. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

- 2.Daly M, Macchia L. Global trends in emotional distress. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2023;120(14):e2216207120. 10.1073/pnas.2216207120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685. 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esch T, Stefano GB, Fricchione GL, Benson H. Stress in cardiovascular diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8(5):RA93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adaramola SS. Job stress and productivity increase. Work. 2012;41:2955–8. 10.3233/WOR-2012-0547-2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganster DC, Rosen CC. Work stress and employee health. J Manag. 2013;39(5):1085–122. 10.1177/0149206313475815. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piao X, Managi S. Evaluation of employee occupational stress by estimating the loss of human capital in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):411. 10.1186/s12889-022-12751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, Chen-Li D, Iacobucci M, Ho R, Majeed A, McIntyre RS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawachi I. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–67. 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Burns JK, Dhingra M, Tarver L, Kohrt BA, Lund C. Income inequality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):76–89. 10.1002/wps.20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirmayer LJ, Swartz L. Culture and Global Mental Health. In: Patel V, and others, editors. Global Mental Health: Principles and Practice. New York: Oxford Academic; 2014. 10.1093/med/9780199920181.003.0003. Accessed 6 Dec 2024.

- 13.Kleinman A. Global mental health: a failure of humanity. Lancet. 2009;374:603–4. 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61510-5. Pubmed:19708102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(3):486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(5):808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howland M, Armeli S, Feinn R, Tennen H. Daily emotional stress reactivity in emerging adulthood: temporal stability and its predictors. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;30(2):121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myin-Germeys I, van Os J, Schwartz JE, Stone AA, Delespaul PA. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(12):1137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rickenbach EH, Condeelis KL, Haley WE. Daily stressors and emotional reactivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and cognitively healthy controls. Psychol Aging. 2015;30(2):420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawakami N, et al. Early-life mental disorders and adult household income in the world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:228–37. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.009. Pubmed:22521149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro WS, et al. Income inequality and mental illness-related morbidity and resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:554–62. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30159-1. Pubmed:28552501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumgartner JN, Susser E. Social integration in global mental health: what is it and how can it be measured? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2013;22:29–37. 10.1017/S2045796012000303. Pubmed:22794167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohrt BA, et al. The role of communities in mental health care in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-review of components and competencies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1279. 10.3390/ijerph15061279. Pubmed:29914185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hossain MM, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Research. 2020;9:636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kola L, et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:535–50. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00025-0. Pubmed:33639109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kola L. Global mental health and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:655–7. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30235-2. Pubmed:32502468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kniffin KM, et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am Psychol. 2021;76:63–77. 10.1037/amp0000716. Pubmed:32772537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Q. Employment precarity, COVID-19 risk, and workers’ well-being during the pandemic in Europe. Work Occup. 2022:073088842211264. 10.1177/07308884221126415.

- 28.Yamamura E, Tsustsui Y. The impact of closing schools on working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence using panel data from Japan. Rev Econ Household. 2021;19:41–60. 10.1007/s11150-020-09536-5. Pubmed:33456424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jareebi MA, Alqassim AY. The impact of educational attainment on mental health: a causal assessment from the UKB and FinnGen Cohorts. Medicine. 2024;103(26):e38602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan N, Guariglia A, Moore P, Xu F, Al-Janabi H. Financial stress and depression in adults: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon BC, Nikolaev BN, Shepherd DA. Does educational attainment promote job satisfaction? The bittersweet trade-offs between job resources, demands, and stress. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(7):1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R, Liu S, Huang C, Darabi D, Zhao M, Heinzel S. The influence of perceived stress and income on mental health in China and Germany. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e17344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, Hammarström A, Hogstedt C, Marteinsdottir I, Skoog I, Träskman-Bendz L, Hall C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264. 10.1186/s12889-017-4153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Too LS, Leach L, Butterworth P. Is the association between poor job control and common mental disorder explained by general perceptions of control? Findings from an Australian longitudinal cohort. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(3):311–20. 10.5271/sjweh.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallup. Worldwide research methodology and codebook. 2013. https://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/8494/download/89823. Accessed 21 Oct 2024.

- 36.Gallup. World Poll Methodology. 2021. https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2024.

- 37.Almeida DM, Charles ST, Mogle J, Drewelies J, Aldwin CM, Spiro A, Gerstorf D. Charting adult development through (historically changing) daily stress processes. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):511–24. 10.1037/amp0000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almeida DM, Rush J, Mogle J, Piazza JR, Cerino E, Charles ST. Longitudinal change in daily stress across 20 years of adulthood: results from the national study of daily experiences. Dev Psychol. 2023;59(3):515–23. 10.1037/dev0001469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.daSilva AW, Huckins JF, Wang W, Wang R, Campbell AT, Meyer ML. Daily perceived stress predicts less next day social interaction: evidence from a naturalistic mobile sensing study. Emotion. 2021;21(8):1760–70. 10.1037/emo0000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Borszcz GS, Cano A, Radcliffe AM, Porter LS, Schubiner H, Keefe FJ. Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(9):942–68. 10.1002/jclp.20816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lado M, Alonso P, Cuadrado D, Otero I, Martínez A. Economic stress, employee commitment, and subjective well-being. Rev Psicol Trab Organ. 2023;39(1):7–12. 10.5093/jwop2023a2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly unavailable; Gallup, Inc. provided data access permission and other de-identified data for the current study.