Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are the most common types of mental disorders among cancer patients. Many research studies carried out in African countries indicate that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent, but the results vary across regions. Thus, this study aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among cancer patients in Africa.

Methods

The databases EMBASE, PubMed, African Journals Online, and Google Scholar were used to identify articles. This systematic review and meta-analysis included 32 (31 for depression and 25 for anxiety) original articles from 11 African countries. To detect publication bias, Egger regression tests and funnel plot analysis were employed. A sensitivity analysis and a subgroup analysis were carried out.

Results

The pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients was found to be 53.21% (95% CI: 47.47–58.94) and 53.32% (95% CI: 46.85, 59.80) respectively. Across regions, the prevalence of depression among cancer patients was 60.03 (95% CI: 55.85–64.21), 53.59 (95% CI: 45.31–61.87), and 43.92 (95% CI: 36.17–51.67) in North, East, and West Africa, respectively. The pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients was 64.85 (95% CI: 54.81–74.88) in North Africa, 49.53 (95% CI: 40.72–58.33) in East Africa, and 46.23 (95% CI: 38.98–53.48) in West Africa. Advanced stages of cancer (AOR = 3.8; 95% CI: 1.73, 8.42), less educated (AOR = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.28–5.14), and having no financial support (AOR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.67) were factors associated with depression. Advanced stages of cancer (AOR = 5.44; 95% CI: 1.95, 15.18) and no financial assistance (AOR = 2.88; 95% CI: 1.79, 4.63) were factors associated with anxiety.

Conclusion

Depression and anxiety among cancer patients are highly prevalent in Africa. Being at an advanced stage of cancer, low educational attainment, and not having financial support were all associated with depression symptoms; in addition, having advanced cancer and not having financial support were also associated with anxiety symptoms. Therefore, it is critical to screen cancer patients for anxiety and depression and provide them with appropriate interventions when these conditions arise.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-024-06389-5.

Keywords: Depression, Anxiety, Cancer, Africa, A systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Africa is divided into five primary regions: North, West, East, Central, and Southern Africa. It consists of 54 recognized independent nations and two contested territories. As of 2024, the continent’s population stands at approximately 1.46 billion, ranking it as the second most populous continent after Asia. This substantial population underscores Africa’s global importance, with its diverse cultures, economies, and rapidly growing urban centers playing a key role in shaping the future [1, 2]. Cancer, a leading cause of death worldwide, is a complex and multidisciplinary disease with significant psychosocial implications [3]. “The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in 2018, cancer was responsible for approximately 18 million new cases and 9.6 million deaths globally’’ [4]. Cancer also leads to depression and anxiety, making life more difficult for patients [3]. Cancer is rapidly affecting health in Africa, with a suggested 70% increase in new cases by 2030 due to population growth and aging, highlighting the urgent need for effective prevention and control methods [5]. Africa faces a lack of resources for cancer patients, leading to shorter hospital stays and more outpatient treatments, causing stress and mental health issues like depression and anxiety among patients [6].

The global prevalence of depression among cancer patients was 27%, and the sub-group analysis of this study shows that the highest prevalence of depression was observed among patients with colorectal cancer at 32% [7]. Furthermore, other worldwide meta-analysis studies demonstrate that depression was prevalent in 980 (21.7%) of patients with brain tumors [8] and in 30.2% of patients with breast cancer specifically [9]. The pooled prevalence of anxiety among breast tumors was found in the Americas (38%), Eastern Mediterranean (56%), Europe (38%), South-East Asia (42%), and Western Pacific (26%) regions, according to a meta-analysis study that comprised 128 articles [10]. Several studies have also shown, through a range of assessment tools, that cancer patients experience high levels of anxiety and depression. In a review in low- and middle-income countries, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies show that the prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients was 21% and 18%, respectively, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of mental disorders and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [11]. In Africa, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer patients was 33.3–88% [12, 13] and 25–88% [13, 14], respectively.

Depression and anxiety are common among cancer patients, leading to higher mortality rates and reduced survival [15, 16]. These mental health issues can lead to symptom control issues, such as patients struggling to communicate their pain, treatment delays from missed appointments due to lack of motivation, and impaired quality of life due to social isolation. Patients may avoid social interactions because of feelings of worthlessness, leading to further isolation and a diminished sense of well-being [16–19], increased suicide risk and cancer progression [15, 20]. In Africa, the financial burden of therapy exacerbates the stress on patients and their families [21, 22]. Factors contributing to these mental health issues include reactions to the cancer diagnosis, disease stage, low education, financial difficulties [11, 23–27]. Additionally, sociodemographic and clinical factors like age, occupation, pain severity, hormonal therapy, and social support also play a significant role in influencing these symptoms [25, 27, 28].

Determining the precise prevalence of anxiety and depression among African cancer patients will help to develop more effective prevention interventions. Individual studies included in the current meta-analysis have shown that cancer patients in Africa experience high levels of anxiety and depression. However, the findings are inconsistent, with anxiety prevalence ranging from 33.3 to 88% [12, 13] and depression prevalence ranging from 25 to 88% [13, 14]. As a result, these varying figures make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Thus, this study aims to fill this epidemiological gap by determining the pooled prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among patients with cancer in Africa.

Research questions

What is the pooled prevalence of depression among cancer patients in Africa?

What is the pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa?

What are the associated factors for depression among cancer patients in Africa?

What are the associated factors for anxiety among cancer patients in Africa?

Methodology

Protocol registration and reporting

This meta-analysis and systematic review protocol was registered with registration number CRD42024516880 in the Prospective Register of Systemic Review (PROSPERO). The (PRISMA 2020) guidelines were used in the search strategy and publication selection for the review [29] (Additional file 1).

Study screening and selection

This study was conducted to determine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and associated factors among cancer patients in Africa. EMBASE, and PubMed along with databases such as African Journals Online, ScienceDirect, and the WHO database portal for low- and middle-income countries (e.g., Research4Life and Global Index Medicus), as well as other gray literature from Google Scholar, and Google were searched for original articles published in English from June 2012 to November 10, 2023. A search strategy was developed for each database using free texts and controlled vocabularies (Mesh). The search for these articles was carried out until February 10, 2024. The following keywords were used for the search: (“magnitude” OR “prevalence” OR “epidemiology) AND (“depression” OR “depressive symptoms” OR “anxiety” OR “anxiety symptoms”) AND (“associated factors” OR “determinants” OR “risk factors” OR “predictors” OR “correlate”) AND “cancer,” OR “neoplasm,” OR “tumor” OR “malignancy”) AND using an African search filter developed by Pienaar et al., to identify prevalence studies [30] Additional file 2 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in conducting this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All the articles included in this review and meta-analysis were cross-sectional, and published from June 2012 to November 10, 2023. The inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis are as follows:

Studies that report the prevalence of depression among cancer patients.

Studies that report the prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients.

Studies that report both the prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients.

The articles were published in English only, and.

Articles conducted in Africa only.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis are as follows:

Studies that reported the prevalence of neither anxiety nor depression.

Reviews, editorial letters, poster presentations, and case reports were excluded.

Studies published in languages other than English.

Studies conducted outside the continent of Africa.

In addition, research that lacked complete data access and duplicated studies were also excluded.

Outcome of interest

There are four primary outcomes for this systematic review and meta-analysis study. The first outcome was to determine the pooled prevalence of depression among cancer patients in Africa. The second outcome is to determine the pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa. The third and fourth outcomes were to identify the pooled effects of factors associated with depression and anxiety.

Data extraction

Two experienced researchers, GT and MAK, independently searched the same databases using identical search terms. Four additional authors also assist the two authors (GT and MAK). After combining the articles from both searches in EndNote X20 software, duplicates were identified and removed. Two independent reviewers, GMT and GK both mental health professionals experienced in conducting reviews assessed the titles and abstracts of the publications for eligibility based on predetermined criteria. After carefully reviewing the article titles, abstracts, and full texts, this was arranged using Microsoft Excel 2010 by two independent reviewers (GMT and GK). At this stage, discrepancies in decision-making were resolved through discussions with the senior author (MM). Finally, articles approved by all reviewers in the selection processes were included in the study. For instance, in the first sheet of the Excel file, we extracted the following information to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depression: the first author’s name, the year the study was conducted, the year of publication, the study design, the country or region where the study took place, the screening tool used to assess depression or anxiety, the sample size, and the reported prevalence of depression and anxiety. For the associated factors outcome, we extracted data such as the first author’s name, the country or region where the study was conducted, the sample size, the reported prevalence of anxiety and depression, the associated factors, and the corresponding odds ratio data for depression and anxiety. This information was organized in a separate Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The combined estimated effects of the related covariates and prevalence of depression and anxiety, together with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and odds ratios, were also extracted.

Quality assessment

The retrieved articles were imported into EndNote X20 for gathering and arranging search results and eliminating duplicate entries. Two authors (GMT, and GK) evaluated the quality of the primary studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria. Two additional authors also assist the two authors (GMT and GK). There are nine questions on this tool. A score of 1 was given for “yes” and 0 for “not reported or not appropriate” for each question. Subsequently, the results were summarized to provide an overall score that ranged from 0 to 9. Articles quality was rated as high 8–9, medium 5–7, or low 0–4 based on the points that were categorized [31]. Inclusion in the final analysis was based on papers of high and medium quality (greater than or equal to 5). All discrepancies among the reviewers were resolved through discussions between the reviewers, with guidance from the senior author (MM).

Statistical analysis

After being extracted, the data were put into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and exported to STATA 17.0 for analysis. A forest plot was used to visually represent the prevalence of anxiety and depression, with a 95% confidence interval. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was used to identify the pooled effect size of factors associated with depression and anxiety. The index of heterogeneity (I2 statistics) was used to determine the degree of heterogeneity among the included articles. Therefore, based on Higgins’ I² values: less than 25% represents no heterogeneity, 25–49% represents low heterogeneity, 50–74% represents moderate heterogeneity, and values greater than or equal to 75% represent high heterogeneity [32]. Using sensitivity analysis, and sub-group analysis, the potential sources of heterogeneity were identified. Subgroup analyses were conducted with consideration for the study area (country), region, the country, the sample size, the study year, tool types, and type of cancer. Publication bias was assessed by using both observation of the symmetry in the funnel plots and Egger weighted regression tests [33, 34]. In Egger’s test, a p-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistically significant publication bias.

Results

Study selection

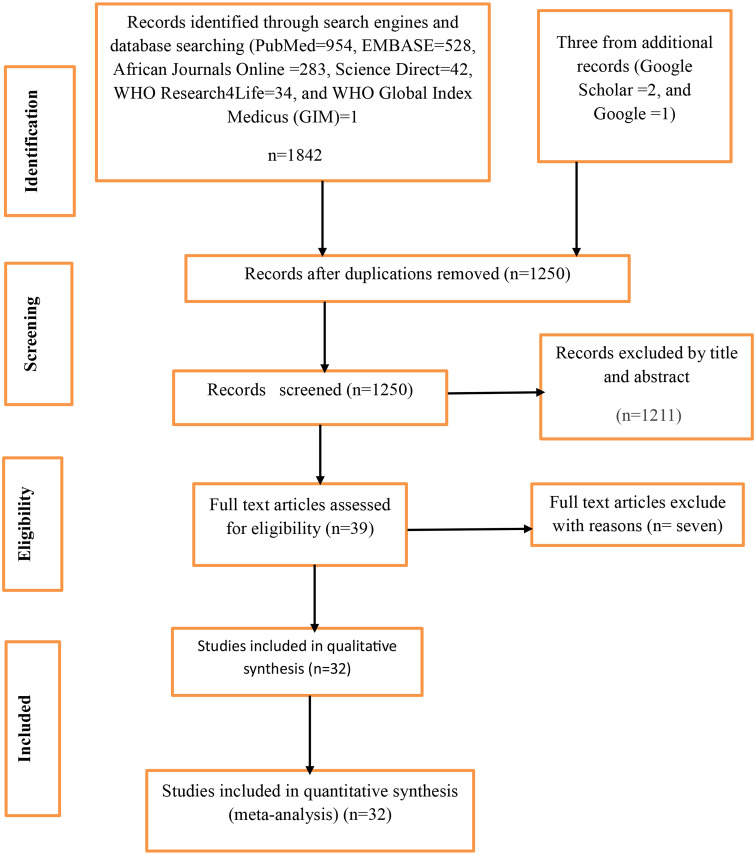

A total of 1845 articles were retrieved through database literature searching, including manual searching. Of these, 595 articles were excluded due to duplication, and 1,211 unrelated articles were excluded by their title and abstracts. The remaining 39 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion; of them, seven full-text articles were excluded with reasons. Finally, 32 studies were included in the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flows diagram

Characteristics of included studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 32 published articles on 6,436 cancer patients from 11 different African countries. Out of this, 24 articles reported both depression and anxiety, seven studies reported depression alone, and one study reported anxiety only. Generally, the pooled prevalence of anxiety and depression was determined using 31 and 25 articles, respectively. The cross-sectional study design was used in all of the papers that made up this review; the sample sizes varied from 51 to 428 and were published between June 2012 and November 10, 2023. Of the 32 studies included, five focused on gynecological cancer; nine included breast cancer patients only; one included orofacial cancer; and others included all malignancies. The majority of the studies [10] were conducted in Ethiopia, four in Kenya, four in Morocco, four in Nigeria, two in Egypt, two in Rwanda, two in Sudan, one in Zambia, one in Ghana, one in Tunisia, and one in Cameroon. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (HADS) were employed in 19 investigations, the Beck Depression Scale in 5, and the Patient Health Questionnaire in three studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of original articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients in Africa

| Authors, publication year |

Country | Participants included | Tool used | Outcome reported | Sample size |

Prevalence of depression in % | Prevalence of anxiety in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atinafu et al., 2022 [26] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 171 | 47.4 | 64.9 |

| Berihun et al., 2017 [27] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 77 | 58.44 | 51 |

| Ayalew et al., 2022 [63] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 415 | 58.8 | 60 |

| Endeshaw et al., 2022 [64] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 392 | 60.2 | 57.1 |

| Abraham et al., 2022 [65] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 423 | 54.6 | 40.4 |

| Belay et al., 2022 [51] | Ethiopia | breast cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 333 | 58.6 | 60.7 |

| Kulkarni, 2022 [66] | Kenya | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 100 | 33 | 39 |

| Asiagi 2019 [12] | Kenya | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 195 | 39 | 33.3 |

| Ali, 2021 [13] | Kenya | Gynecological cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 120 | 88 | 88 |

| Habimana et al., 2023 [67] | Rwanda | All cancer patients | BDI and Trait Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety and depression | 425 | 42.6 | 40.9 |

| Uwayezu et al., 2019 [68] | Rwanda | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 96 | 67.7 | 52.1 |

| Al Bdour and Mohamed, 2018 [69] | Sudan | Orofacial cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 51 | 47.1 | 39.2 |

| Bakhiet et al., 2021 [70] | Sudan | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 255 | 41.2 | 26.7 |

| Ebob-Anya and Bassah, 2022 [71] | Cameroon | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 120 | 47.5 | 50 |

| Alagizy et al., 2020 [72] | Egypt | Breast cancer patients | BDI and Manifest Anxiety Scale | Anxiety and depression | 64 | 68.6 | 73.3 |

| Aly et al., 2017 [73] | Egypt | Breast cancer patients | BDI and Manifest Anxiety Scale | Anxiety and depression | 96 | 46.87 | 49.96 |

| Azizi et al., 2023 [74] | Morocco | Gynecological cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 103 | 61.2 | 62.1 |

| Aquil et al., 2021 [75] | Morocco | Gynecological cancer patients | Not reported | Anxiety and depression | 100 | 59 | 66 |

| Omari et al., 2023 [76] | Morocco | Breast cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 209 | 59.62 | 47.85 |

| Mahlaq et al., 2023 [52] | Morocco | Breast cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 230 | 62.6 | 77.4 |

| letaief KSONTINI et al., 2021 [77] | Tunisia | Breast cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 100 | 62 | 77 |

| Asuzu and Adenipekun, 2015 [78] | Nigeria | All cancer patients | BDI and Fear of Progression | Anxiety and depression | 206 | 31.6 | 36.9 |

| Alegbeleye and Biyi-Olutunde, 2023 [79] | Nigeria | Gynecological cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 75 | 61.3 | 52 |

| Kugbey, 2022 [80] | Ghana | Breast cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety and depression | 205 | 37.3 | 48.5 |

| Baraki et al., 2020 [81] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | patient health questionnaire | Depression only | 302 | 70.86 | |

| Belete et al., 2022 [82] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | patient health questionnaire | Depression only | 420 | 33.1 | |

| Wondimagegnehu et al., 2019 [14] | Ethiopia | Breast cancer patients | patient health questionnaire | Depression only | 428 | 25 | |

| Saina et al.,2021 [83] | Kenya | All cancer patients | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | Depression only | 79 | 59.5 | |

| Popoola and Adewuya, 2012 [84] | Nigeria | Breast cancer patients | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview | Depression only | 124 | 40.3 | |

| Olagunju et al., 2013 [85] | Nigeria | All cancer patients | Depression Scale Revised | Depression only | 200 | 49 | |

| Paul et al., 2016 [86] | Zambia | Gynecological cancer patients | BDI | Depression only | 102 | 80 | |

| Wurjine and Goyteom, 2020 [87] | Ethiopia | All cancer patients | HADS | Anxiety only | 220 | 38.6 |

Quality assessment results

The quality of the included primary studies, as assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria, revealed that 23 articles (71.9%) were rated as high quality, while the remaining 9 articles (28.1%) were rated as medium quality (Additional file 3).

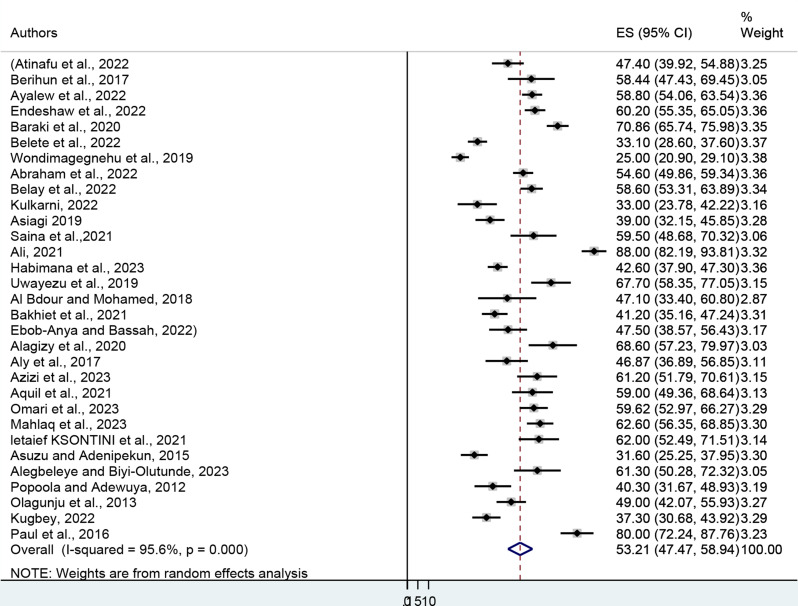

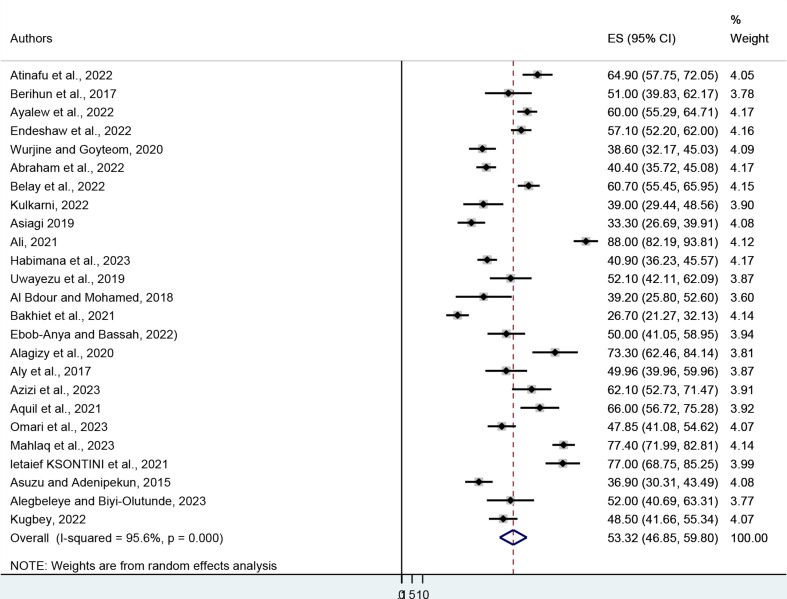

Prevalence of depression and anxiety

A sample of 6,216 cancer patients was drawn from 31 published articles to estimate the pooled prevalence of depression. The minimum and maximum prevalence of depression were reported at 25% in Ethiopia and 88% in Kenya respectively. The pooled prevalence of depression among cancer patients was found to be 53.21% (95% CI: 47.47–58.94). The heterogeneity was I2 = 95.6, P = 0.000) (Fig. 2). In terms of anxiety prevalence, it was observed that the minimum and maximum prevalence of anxiety were reported at 26.7% in Sudan and 88% in Kenya, respectively. The results of 25 studies involving 4,781 respondents indicated that the overall pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa was 53.32% (95% CI: 46.85, 59.80). The heterogeneity (I2 = 95.6, P = 0.000) (Fig. 3). From the above results, the I2 test showed higher heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of depression among cancer patients in Africa

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa

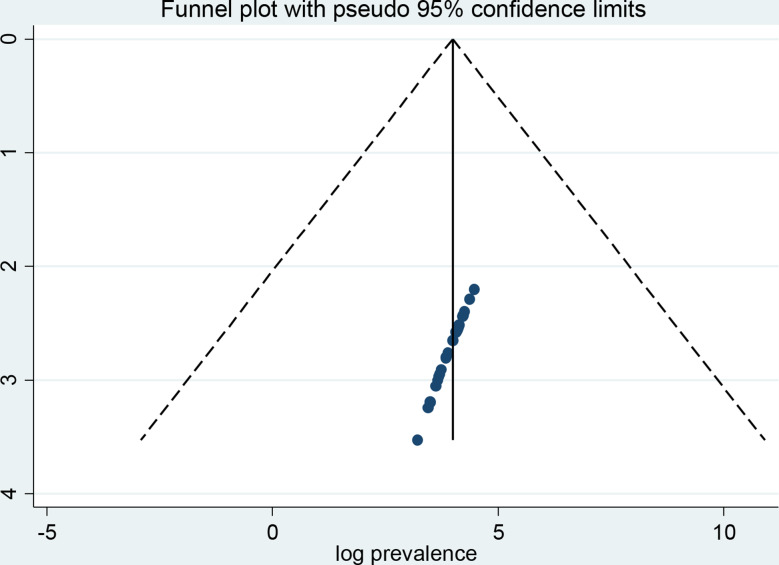

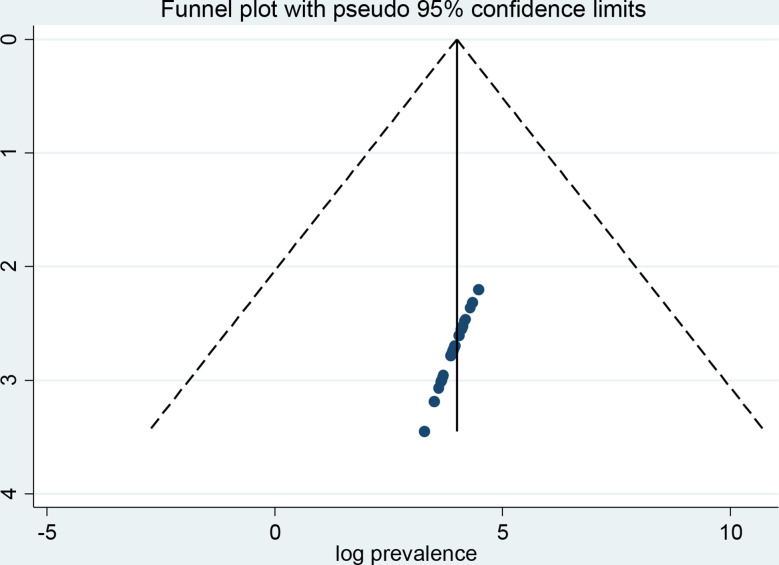

Publication bias

A funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were employed to investigate the possibility of publication bias. When looking at depression in cancer patients, the funnel plot triangle result shows a symmetric distribution, which suggests that there was no publication bias in any of the included studies (Fig. 4). The Egger’s regression weighted test (p = 0.241) also indicates the absence of publication bias (Table 2). Regarding anxiety, the funnel plot test triangle exhibits symmetry (Fig. 5), and Egger’s regression weighted test yielded no statistically significant difference (p = 0.792) (Table 3). Together, these tests demonstrate that there is no publishing bias in the included studies.

Fig. 4.

A funnel plot test of depression among cancer patients

Table 2.

Egger’s test of depression among cancer patients in Africa

| Std_Eff | | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P>|t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | | 40.63371 | 9.307573 | 4.37 | 0.000 | 21.59758 | 59.66983 |

| bias | | 3.325203 | 2.778652 | 1.20 | 0.241 | -2.357779 | 9.008184 |

Fig. 5.

A funnel plot test of anxiety among cancer patients

Table 3.

Egger’s test of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa

| Std_Eff | | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P>|t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | | 49.9628 | 11.31753 | 4.41 | 0.000 | 26.55071 | 73.37489 |

| bias | | 8,837,334 | 3.308199 | 0.27 | 0.792 | -5.959798 | 7.727265 |

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was carried out using the cancer types in which the study was conducted, the study regions, the country, the sample size, the study year, and the tools used to screen for anxiety and depression symptoms to identify potential sources of heterogeneity. As a result, patients with gynecological cancer had the highest prevalence of depression, at 70.31 (95% CI: 57.64–82.98), compared to 49.56 (95% CI: 43.27–55.84), 51.03 (95% CI: 39.68–62.37), and 47.10 (95% CI: 33.40–60.80) among patients with all types of cancer, breast, and orofacial cancer, respectively. Across regions, the prevalence of depression among cancer patients was 60.03 (95% CI: 55.85–64.21), 53.59 (95% CI: 45.31–61.87), and 43.92 (95% CI: 36.17–51.67) in North, East, and West Africa, respectively. Based on the countries where the study was conducted, the highest prevalence of depression was reported in Morocco at 60.86% (95% CI: 57.09–64.64), while the lowest was observed in Sudan at 42.16% (95% CI: 36.63–47.69). During the study period, the prevalence of depression was 50.77% (95% CI: 39.94–61.60) before 2019, increasing to 54.63% (95% CI: 47.19–62.07) in 2019 and afterward. In studies where the study period was not specified, the prevalence of depression was 54.33% (95% CI: 40.85–67.82). Subgroup analysis showed that in studies with fewer than 200 participants, the prevalence of depression was 56.94% (95% CI: 48.58–65.30). However, in studies with a sample size of 200 or more, the prevalence of depression was 48.92% (95% CI: 41.21–56.64). Based on the screening tools used, the prevalence of depression among cancer patients using the hospital and anxiety depression scale (HADS), patient health questionnaire (PHQ), Beck depression inventory, and other tools was 55.11 (95% CI: 49.21–61.01), 42.950 (95% CI: 16.67–69.23), 53.72 (95% CI: 36.58–70.85), and 51.52 (95% CI: 42.95–60.08), respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of depression among cancer patients in Africa

| Characteristics | Studies | Sample | Prevalence of depression in % | I2(%) | P-value | Egger test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of depression | 31 | 6,216 | 53.21% (95% CI: 47.47–58.94) | 95.6 | 0.000 | 0.241 |

| Region | ||||||

| North | 7 | 902 | 60.03 (95% CI: 55.85–64.21) | 38.7 | 0.134 | |

| East | 18 | 4,384 | 53.59 (95% CI: 45.31–61.87) | 97.1 | 0.000 | |

| West | 6 | 930 | 43.92 (95% CI: 36.17–51.67) | 83.1 | 0.000 | |

| Countries | ||||||

| Ethiopia | 9 | 2,961 | 51.81 (95% CI: 41.03–62.58) | 97.4 | 0.000 | |

| Kenya | 4 | 494 | 54.95 (95% CI: 26.68–83.22) | 98.1 | 0.000 | |

| Rwanda | 2 | 521 | 54.81 (95% CI: 30.22–79.40) | 95.5 | 0.000 | |

| Sudan | 2 | 306 | 42.16 (95% CI: 36.63–47.69) | 0.0 | 0.440 | |

| Egypt | 2 | 160 | 57.56 (95% CI: 36.27–78.85) | 87.4 | 0.005 | |

| Morocco | 4 | 642 | 60.86 (95% CI: 57.09–64.64) | 0.0 | 0.901 | |

| Nigeria | 4 | 605 | 45.06 (95% CI:33.33–56.80) | 88.5 | 0.000 | |

| Cameron, Tunisia, Ghana, and Zambia | 4 | 527 | 56.65 (95% CI: 36.82–76.48) | 95.8 | 0.000 | |

| Study year | ||||||

| Before 2019 | 11 | 1,860 | 50.77 (95% CI: 39.94–61.60) | 95.8 | 0.000 | |

| 2019 and after | 12 | 2,927 | 54.63 (95% CI: 47.19–62.07) | 94.2 | 0.000 | |

| Study year not reported | 8 | 1,429 | 54.33 (95% CI: 40.85–67.82) | 96.6 | 0.000 | |

| Based on sample size | ||||||

| Less than 200 | 17 | 1,773 | 56.94 (95% CI: 48.58–65.30) | 93.2 | 0.000 | |

| 200 and above | 14 | 4,443 | 48.92 (95% CI: 41.21–56.64) | 96,6 | 0.000 | |

| Types of study population | ||||||

| All cancer patients | 16 | 3,876 | 49.56 (95% CI: 43.27–55.84) | 93.9 | 0.000 | |

| gynecological cancer patients | 5 | 500 | 70.31 (95% CI: 57.64–82.98) | 91.2 | 0.000 | |

| Breast cancer | 9 | 1,789 | 51.03 (95% CI: 39.68–62.37), | 96.0 | 0.000 | |

| orofacial cancer | 1 | 51 | 47.10 (95% CI: 33.40–60.80) | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Screening tool used | ||||||

| HADS | 19 | 3,670 | 55.11 (95% CI: 49.21–61.01) | 92.8 | 0.000 | |

| Beck depression inventory | 5 | 893 | 53.72 (95% CI: 36.58–70.85) | 96.3 | 0.000 | |

| patient health questionnaire (PHQ) | 3 | 1,150 | 42.95 (95% CI: 16.67– 69.23) | 99.0 | 0.000 | |

| *Other tools | 4 | 503 | 51.52 (95% CI: 42.95–60.08 | 96.0 | 0.000 | |

*Other tools: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Depression Scale Revised, and an unreported screening tool

The pooled prevalence of anxiety among patients with all types of cancer (general), breast, gynecological, and orofacial cancers was 45.36 (95% CI: 38.79–51.93), 62.06 (95% CI: 51.94–72.18), 67.41 (95% CI: 50.52–84.30), and 39.20 (95% CI: 25.80–52.60), respectively. Across regions, the pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients was 64.85 (95% CI: 54.81–74.88) in North Africa, 49.53 (95% CI: 40.72–58.33) in East Africa, and 46.23 (95% CI: 38.98–53.48) in West Africa. Sub-group analysis by country indicated that the highest prevalence of anxiety occurred in Morocco, observed at 63.40% (95% CI: 48.98–77.81), whereas the lowest prevalence was found in Sudan at 31.39% (95% CI: 19.53–43.25). Throughout the study period, the prevalence of anxiety before 2019 was 46.00% (95% CI: 40.11–51.90), increasing to 53.26% (95% CI: 44.74–61.79) in 2019 and thereafter. For studies that did not specify their study period, the prevalence of anxiety was 57.56% (95% CI: 42.64–72.48). In studies with sample sizes of fewer than 200 participants, the prevalence of anxiety was 57.15% (95% CI: 47.38–66.92), while studies with 200 or more participants reported a prevalence of 48.68% (95% CI: 40.14–57.21). Furthermore, the pooled prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients using the screening tool HADS was 53.39 (95% CI: 45.92–60.86), whereas the Manifest Anxiety Scale was 61.53 (95% CI: 38.66–84.41) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa

| Characteristics | Studies | Sample | Prevalence of anxiety in % | I2(%) | P-value | Egger test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of anxiety | 25 | 4,781 | 53.32% (95% CI: 46.85, 59.80) | 95.6 | 0.000 | 0.792 |

| Region | ||||||

| North | 7 | 902 | 64.85 (95% CI: 54.81–74.88) | 90.6 | 0.000 | |

| East | 14 | 3,273 | 49.53 (95% CI: 40.72–58.33 | 96.5 | 0.000 | |

| West | 4 | 606 | 46.23 (95% CI: 38.98–53.48) | 68.4 | 0.024 | |

| Countries | ||||||

| Ethiopia | 7 | 2031 | 53.27 (95% CI: 45.43–61.12) | 92.2 | 0.000 | |

| Kenya | 3 | 415 | 53.51 (95% CI: 15.56–91.47) | 98.8 | 0.000 | |

| Rwanda | 2 | 521 | 45.59 (95% CI: 34.76–56.42) | 74.7 | 0.047 | |

| Sudan | 2 | 306 | 31.39 (95% CI: 19.53–43.25) | 65.2 | 0.090 | |

| Egypt | 2 | 160 | 61.53 (95% CI: 38.66–84.41) | 89.6 | 0.002 | |

| Morocco | 4 | 642 | 63.40 (95% CI: 48.98–77.81) | 93.4 | 0.000 | |

| Nigeria | 2 | 281 | 43.72 (95% CI: 28.99–58.45) | 80.4 | 0.024 | |

| Cameron, Tunisia, and Ghana | 3 | 425 | 58.46 (95% CI: 40.39–76.53) | 93.5 | 0.000 | |

| Study year | ||||||

| Before 2019 | 5 | 743 | 46.00 (95% CI: 40.11–51.90) | 51.0 | 0.086 | |

| 2019 and after | 12 | 2,525 | 53.26 (95% CI: 44.74–61.79) | 95.0 | 0.000 | |

| Study year not reported | 8 | 1,513 | 57.56 (95% CI: 42.64–72.48) | 97.5 | ||

| Based on the sample size | ||||||

| Less than 200 | 14 | 1,368 | 57.15 (95% CI: 47.38–66.92) | 94.1 | 0.000 | |

| 200 and above | 11 | 3,443 | 48.68 (95% CI: 40.14–57.21) | 96.3 | 0.000 | |

| Types of study population | ||||||

| All cancer patients | 13 | 3,095 | 45.36 (95% CI: 38.79–51.93) | 92.9 | 0.000 | |

| gynecological cancer patients | 4 | 398 | 67.41 (95% CI: 50.52–84.30) | 93.5 | 0.000 | |

| Breast cancer | 7 | 1,237 | 62.06 (95% CI: 51.94–72 | 93.0 | 0.000 | |

| orofacial cancer | 1 | 51 | 39.20 (95% CI: 25.80–52.60) | 0.00 | 0.000 | |

| Screening tool used | ||||||

| HADS | 20 | 3,890 | 53.39 (95% CI: 45.92–60.86 | 96.0 | 0.000 | |

| Manifest Anxiety Scale | 2 | 160 | 61.53 (95% CI: 38.66–84.41) | 89.6 | 0.002 | |

| Other tools | 3 | 731 | 47.44 (95% CI: 33.24–61.64) | 92.8 | 0.000 | |

Other tools: Trait Anxiety Inventory, Fear of Progression and an unreported screening tool

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was carried out to look into the heterogeneity of those articles and find out how the results of one study affected the prevalence of depression and anxiety overall. The outcome demonstrated that all values fall within the estimated 95% confidence interval, suggesting that the omission of one study did not significantly affect the meta-analysis’s prevalences (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of depression and anxiety among cancer patients in Africa

| Study omitted | Depression | Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate 95% CI | Heterogeneity | Point estimate 95% CI | Heterogeneity | |||

| I2 (%) | P-value | I 2 | P-value | |||

| Atinafu et al., 2022 [26] | 53.4 (47.50,59.31) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 52.83 (46.1759.50) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Berihun et al., 2017 [27] | 53.1 (47.19,58.90) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.41 (46.76–60.07) | 95.8 | 0.000 |

| Ayalew et al., 2022 [63] | 53.02 (47.04, 59.0) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.03 (46.20-59.87) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Endeshaw et al., 2022 [64] | 52.97 (47.01,58.92) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.16 (46.30-60.02) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Abraham et al., 2022 [65] | 53.16 (47.15, 59.18) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.88 (47.17–60.60) | 95.5 | 0.000 |

| Belay et al., 2022 [51] | 53.02 (47.07, 58.98) | 95.7 | 53.0 (46.22–59.79) | 95.7 | 0.000 | |

| Kulkarni, 2022 [66] | 53.86 (48.05, 59.68) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.90 (47.27–60.53) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Asiagi 2019 [12] | 53.69 (47.82, 59.56) | 95.7 | 0.00 | 54.18 (47.63–60.72) | 95.5 | 0.000 |

| Ali, 2021 [13] | 51.98 (46.75, 57.21) | 94.5 | 0.000 | 51.82 (46.01–57.63) | 94.2 | 0.000 |

| Habimana et al., 2023 [67] | 53.58 (47.61, 59.54) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.86 (47.14–60.59) | 95.5 | 0.000 |

| Uwayezu et al., 2019 [68] | 52.73 (46.91, 58.56) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.37 (46.70-60.05 | 95.8 | 0.000 |

| Al Bdour and Mohamed, 2018 [69] | 53.39 (47.54, 59.23) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.85 (47.24–60.46) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Bakhiet et al., 2021 [70] | 53.62 (47.72, 59.52) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 54.48 (48.26–60.69) | 94.9 | 0.000 |

| Ebob-Anya and Bassah, 2022 [71] | 53.40 (47.51, 59.28) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.46 (46.77–60.15) | 95.8 | 0.000 |

| Alagizy et al., 2020 [72] | 52.73 (46.90, 58.55) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 52.53 (45.96–59.11) | 95.6 | 0.000 |

| Aly et al., 2017 [73] | 53.41 (47.54, 59.28) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.46 (46.79–60.13) | 95.8 | 0.000 |

| Azizi et al., 2023 [74] | 52.95 (47.09, 58.81) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 52.97 (46.31–59.63) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Aquil et al., 2021 [75] | 53.02 (47.15, 58.89) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 52.81 (46.17–59.44) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Omari et al., 2023 [76] | 52.99 (47.09, 58.89) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.56 (46.82–60.29) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Mahlaq et al., 2023 [52] | 52.89 (47.0, 58.77) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 52.28 (45.99–58.57) | 95.0 | 0.000 |

| letaief KSONTINI et al., 2021 [77] | 52.92 (47.07, 58.78) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 52.34 (45.84–58.84) | 95.5 | 0.000 |

| Asuzu and Adenipekun, 2015 [78] | 53.94 (48.17, 59.72) | 95.5 | 0.000 | 54.02 (47.41–60.64) | 95.6 | 0.000 |

| Alegbeleye and Biyi-Olutunde, 2023 [79] | 52.95 (47.10, 58.80) | 95.8 | 0.000 | 53.37 (46.72–60.03) | 95.8 | 0.000 |

| Kugbey, 2022 [80] | 53.75 (47.89, 59.60) | 95.7 | 0.000 | 53.53 (46.79–60.27 | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Baraki et al., 2020 [81] | 52.59 (46.86, 58.33) | 95.4 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Belete et al., 2022 [82] | 53.91 (48.16, 59.65) | 95.3 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Wondimagegnehu et al., 2019 [14] | 54.18 (48.90, 59.47) | 94.4 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Saina et al.,2021 [83] | 53.01 (47.15, 58.86) | 95.8 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Popoola and Adewuya, 2012 [84] | 53.63 (47.77, 59.49) | 95.7 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Olagunju et al., 2013 [85] | 53.35 (47.43, 59.27) | 95.8 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Paul et al., 2016 [86] | 52.31 (46.63, 57.98) | 95.4 | 0.000 | Not applicable | ||

| Wurjine and Goyteom, 2020 [87] | Not applicable | 53.95 (47.30–60.60) | 95.6 | 0.000 | ||

Factors associated with depression and anxiety

Based on the primary studies that were included, many factors have been associated with anxiety and depression, whereas certain ones seem to help protect cancer patients from anxiety and depression. We only take into account factors that have been reported in two or more studies for this meta-analysis to provide pooled factors affecting depression and anxiety.

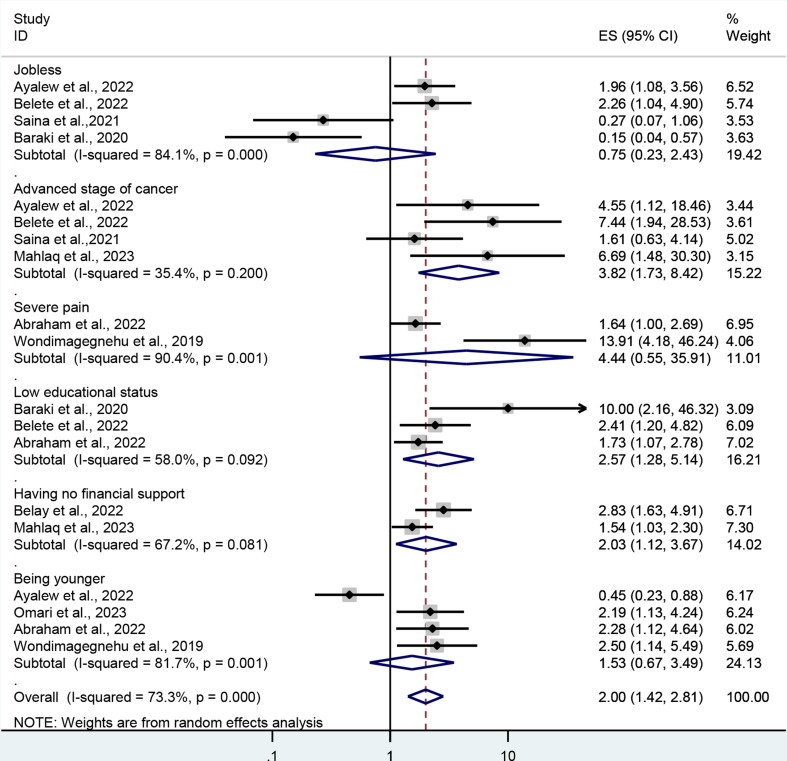

In terms of depression, factors that have been reported more than once and associated either positively or negatively with depression include being unemployed, having an advanced stage of cancer, experiencing severe pain, having a low educational status, lacking financial support, and being younger. However, this meta-analysis revealed that only advanced stages of cancer, low educational status, and having no financial support were factors affecting depression among cancer patients. Therefore, the odds of depression were 3.8 (AOR = 3.8; 95% CI: 1.73, 8.42) times higher in individuals with advanced stages of cancer than in those with early-stage disease. In addition, patients who had low educational status were 2.57 (AOR = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.28–5.14) times higher than their counterparts. The current meta-analysis also shows that patients who have no financial support are about two (AOR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.67) times more likely to have depression than patients who have strong financial support (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The forest plot shows associated factors of depression among cancer patients

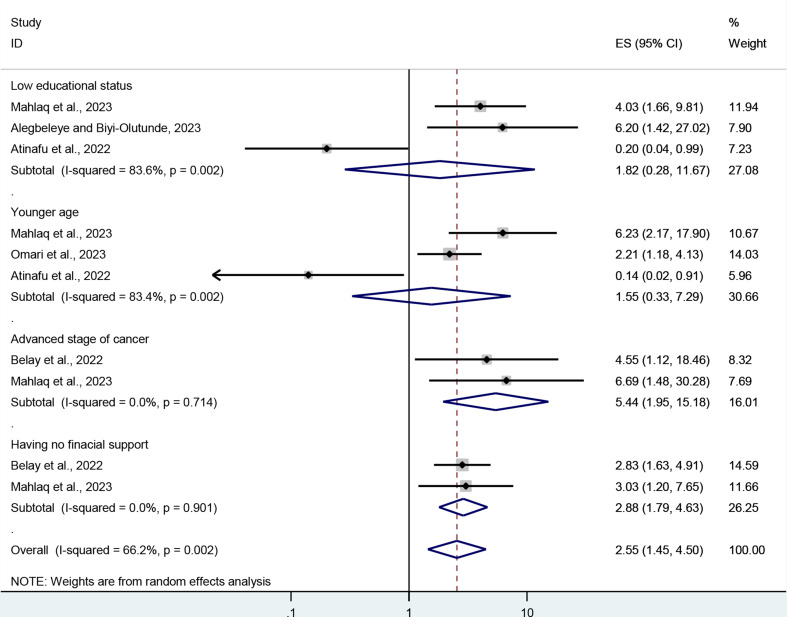

For anxiety, patients not attending more than high school, being younger, having an advanced stage of cancer, and having no financial support were factors reported and associated either positively or negatively with anxiety more than once in the included studies. However, only advanced stages of cancer and having no financial support were associated with anxiety in this meta-analysis. The pooled odds ratio (AOR) showed that compared to early stages, stage four cancer patients had 5.44 higher odds of anxiety (AOR = 5.44; 95% CI: 1.95, 15.18). Additionally, according to this meta-analysis, patients with no financial assistance were around 2.9 (AOR = 2.88; 95% CI: 1.79, 4.63) times more likely to experience anxiety than those with high financial support (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The forest plot shows associated factors of anxiety among cancer patients

Discussion

Depression and anxiety are the most common types of mental disorders among cancer patients. This review and meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of depression among African cancer patients was 53.21%, with a 95% confidence interval (47.47, 58.94). This outcome is consistent with a meta-analysis study that was carried out in Iran and China, yielding 50.1 and 54.9%, respectively [35, 36]. In a meta-analysis study conducted across continents, the subgroup analysis revealed the prevalence of depression among cancer patients in the Eastern Mediterranean region ranged from 49 to 51%, which is consistent with the current meta-analysis [10].

On the contrary, the current finding was significantly higher than with a different systematic review and meta-analysis study that was carried out at a different period, as follows: In low- and middle-income countries, the pooled prevalence of depression among cancer patients as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria was 21% [11]. The various diagnostic tools used in the earlier and current meta-analyses may be the cause of the disparity. While diagnostic instruments like the DSM and ICD were employed in earlier research, screening tools like HADS, PHQ, and the Depression Inventory were utilized to assess all of the original papers included in the current meta-analysis, which may have overestimated the prevalence of depression [37, 38].

In a review of 128 meta-analyses across continents, the prevalence of depression was 40% in Africa, 23–25% in America, 27–29% in Europe, and 23–33% in Southeast Asia [10]. According to a systematic study and meta-analysis with a global, regional, and national focus conducted by researcher Mejareh et al., the prevalence of depression was 27% worldwide and 36% in Africa [39]. The current study is also higher than a meta-analysis study specifically conducted among brain tumors (21.7%) [8], and breast cancer (32.2%) [40]. The variation in results could be attributed to differences in socioeconomic factors between earlier studies and the current one. In all the previous meta-analyses, developed countries were included, whereas the current analysis focuses exclusively on African countries. The high prevalence of depression among cancer patients in Africa may be due to the region’s poor healthcare infrastructure, the quality of patient care, and limited socioeconomic resources for treatment [39, 41]. Another possible reason for the variation is the different tools used in the previous and current meta-analyses. The earlier studies employed diagnostic tools, which are stricter and may have resulted in a lower prevalence. In contrast, the current meta-analysis utilized screening tools, which could have overestimated the prevalence of depression [37, 38]. Additionally, differences in study design may contribute to the disparity. The current meta-analysis includes only cross-sectional studies, whereas the earlier meta-analyses also incorporated longitudinal and cohort studies, which may influence the reported prevalence of depression.

In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled estimated prevalence of anxiety among cancer patients in Africa was found to be 53.32% (95% CI: 46.85, 59.80), and this is consistent with a meta-analysis study conducted in the Eastern Mediterranean region and Chinese adults, which found 56% and 49.69%, respectively [10, 35]. In contrast, the current meta-analysis reported a higher prevalence of depression among cancer patients in African countries compared to low- and middle-income countries, where the prevalence was 18% [11]. The results were also higher than those of a national-based meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia and Iran, which resulted in 45.1% and 40.9%, respectively [36, 42]. The current meta-analysis is also significantly higher than a meta-analysis study across continents in Africa (19%), the Americas (38%), Europe (38%), South-East Asia (42%), and the Western Pacific (26%) [10]. A global pooled prevalence of anxiety specifically among digestive cancer was 20.4% [43], and breast tumor was 41.9% [44]. All results showed that they were lower than the current meta-analysis study.

The variation could be due to differences in mythology, screening tools, and study design in the included original articles between the previous and current studies. For example, the meta-analysis of studies conducted in low and middle-income countries included only original articles assessed by diagnostic tools like the DSM and ICD, whereas the current meta-analysis included only original articles assessed by screening tools like the HADS, Manifest Anxiety Scale, Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Fear of Progression. Such differences might be that diagnostic clinical interviews based on the DSM and ICD use strict criteria for clinical depression, which lowers the prevalence of anxiety symptoms, but studies that applied self-report screening tools might overestimate the prevalence of anxiety in cancer patients [45, 46]. The original articles included in the current review were also conducted through a cross-sectional study design, but the previous ones also included cohort observational studies. This may affect the results of the current and previous studies [46]. The increasing prevalence in the current study might be due to the remarkable advancements in identifying diseases and communication technologies, which have indeed affected public awareness of the disease as well as making people sensitive to its potentially devastating consequences [47, 48].

In analyzing the factors that contribute to depression and anxiety in cancer patients, it was observed that those in advanced stages, such as stage 4, are significantly more vulnerable to these symptoms than patients in earlier stages. A pooled meta-analysis revealed that individuals with advanced cancer have 3.82 times higher odds of developing depression and nearly 5.5 times higher odds of experiencing anxiety. This connection between disease progression and mental health is further reinforced by two meta-analyses: one focusing on depression in brain tumor patients and another examining depression and anxiety in cancer patients from low- and middle-income countries. These studies provide additional evidence that the severity of the disease and limited resources can exacerbate mental health challenges in cancer patients [8, 11]. Patients with advanced cancer frequently endure a range of somatic, symptoms that significantly impact their quality of life. These include persistent fatigue, excessive drowsiness, and a general decline in overall well-being. Additionally, many experience noticeable weight loss and a deterioration in their ability to carry out daily activities, contributing to a reduced functional status. As a result, treatment adherence becomes more challenging, as patients struggle to maintain the energy or motivation to comply with recommended therapies. Prolonged hospital stays also become more common. These physical burdens are often closely associated with psychological challenges, such as depression and anxiety, creating a complex interplay between mental and physical health that can further exacerbate both conditions [49, 50].

Patients with limited financial support are significantly more prone to depression and anxiety compared to those with strong financial support, as shown by two primary studies on depression and two on anxiety included in this meta-analysis [51, 52]. The pooled adjusted odds ratio (AOR) indicated that patients with inadequate financial support had 2.9 times higher odds of experiencing anxiety symptoms and were more than twice as likely to suffer from depression compared to those with strong financial assistance. This finding is further supported by a study conducted across 13 countries, which demonstrated a strong association between financial stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in cancer patients [53]. Financial hardship poses a major challenge for cancer patients in Africa, significantly increasing the risk of anxiety and depression. The burden of financial stress often disrupts their livelihoods, making it difficult for patients to maintain employment, fulfill familial and social obligations, and actively participate in their treatment plans. As a result, many patients face not only the physical and emotional toll of cancer but also the added strain of economic instability, which can worsen their overall well-being. Surveys consistently show a strong correlation between financial toxicity and mental health issues, with patients reporting higher rates of anxiety, depression, and a decline in their physical, emotional, and social quality of life [53–57].

According to the current pooled factor meta-analysis, patients with lower educational status were more than two-and-a-half times as likely to experience depression as their counterparts. Similar results were found in a single study among Indian breast cancer patients [58], among Korean cancer patients [59], and a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted in low- and lower-middle-income countries [11]. Lower education levels among cancer patients are linked to an increased rate of depression, largely because these individuals often lack knowledge about terminal illness, treatment outcomes, and disease recurrence, leading to increased discomfort, tension, and anxiety. Furthermore, lower educational attainment is associated with diminished feelings of control and resilience, which are crucial for coping with the emotional challenges of cancer. As a result, these patients may struggle to navigate their healthcare journeys effectively, further exacerbating their risk of developing depression [58, 60–62].

Limitations of the study

The study has some important limitations; it included only 11 African countries to generalize the findings throughout the continent. Due to language bias, the analysis only included articles written in English and the authors lacked privileged access to the Scopus search engine. Additionally, the age range of participants was not specified in the original articles included in the analysis. Moreover, the studies were conducted using a cross-sectional study design, which provides insights into temporal relationships but does not establish a true cause-and-effect relationship. There was also a notable degree of heterogeneity within the studies.

Conclusion and recommendations

A significant pooled prevalence of anxiety and depression is found among cancer patients in Africa, per this meta-analysis. Being at an advanced stage of cancer, low educational attainment, and not having financial support were all associated with depression symptoms; in addition, only having advanced cancer and not having financial support were associated with anxiety symptoms.

Therefore, it is crucial to screen cancer patients for depression and anxiety, as well as to provide them with successful interventions when these conditions arise. Increased comfort and reduced stress levels are achieved by broadening the scope of financial support available to cancer patients. Patients in advanced stages should also receive psychosocial support; greater attention should be paid to raising awareness, particularly among less educated patients; and improved management practices should be implemented to prevent depression and anxiety in cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Since the original publications included laid the foundation for this systematic review and meta-analysis, we would like to thank the authors.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odd ratio

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CI

Confidence interval

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- MINI

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

In addition to conceptualizing the study, GN worked on its design, data extraction, article analysis, review, interpretation, report writing, and manuscript preparation. Involved in the data extraction were GT, YAW, GK, TT, GMT, GR, and SF. Significant contributions to the manuscript’s drafting and the quality evaluation of the included studies were made by MM, MAK, and FA. Each author accepted the submitted version of the paper and made contributions to it.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

All the data is present in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.NATIONS U. Population divertion of the world 2024.

- 2.Branch SS, Division US. Countries or areas / geographical regions. Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2024.

- 3.Grassi L, Spiegel D, Riba M. Advancing psychosocial care in cancer patients. F1000Research. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Jemal A. Cancer in Africa 2012. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(6):953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magrath I, Sutcliffe S. Building capacity for cancer treatment in low-income countries with particular reference to East Africa. Cancer Control. 2014;8:7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mejareh ZN, Abdollahi B, Hoseinipalangi Z, Jeze MS, Hosseinifard H, Rafiei S, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of depression among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63(6):527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J, Zeng C, Xiao J, Zhao D, Tang H, Wu H, et al. Association between depression and brain tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(55):94932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javan Biparva A, Raoofi S, Rafiei S, Masoumi M, Doustmehraban M, Bagheribayati F, et al. Global depression in breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(7):e0287372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Calderon J, García-Muñoz C, Heredia-Rizo AM, Cano-García FJ. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer around the world: an overview of systematic reviews evaluating 128 meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2024;351. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Walker ZJ, Xue S, Jones MP, Ravindran AV. Depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders in patients with cancer in low-and lower-middle–income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JCO Global Oncol. 2021;7:1233–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogega KA, FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH ANXIETY AND, DEPRESSION AMONG ADULT CANCER. PATIENTS ATTENDING TEXAS CANCER CENTRE, NAIROBI KENYA 2019.

- 13.Ali HS. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with cervical Cancer at Cancer Treatment Centre. Kenyatta National Hospital: UON; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wondimagegnehu A, Abebe W, Abraha A, Teferra S. Depression and social support among breast cancer patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y-H, Li J-Q, Shi J-F, Que J-Y, Liu J-J, Lappin JM, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1487–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gharaei HA, Dianatinasab M, Kouhestani SM, Fararouei M, Moameri H, Pakzad R et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression among breast cancer survivors in Iran: an urgent need for community supportive care programs. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.McDermott CL, Bansal A, Ramsey SD, Lyman GH, Sullivan SD. Depression and health care utilization at end of life among older adults with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(5):699–708. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegel D, Butler LD, Giese-Davis J, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, et al. Effects of supportive‐expressive group therapy on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized prospective trial. Cancer. 2007;110(5):1130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shim E-J, Lee JW, Cho J, Jung HK, Kim NH, Lee JE, et al. Association of depression and anxiety disorder with the risk of mortality in breast cancer: a National Health Insurance Service study in Korea. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;179:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown ML, Lipscomb J, Snyder C. The burden of illness of cancer: economic cost and quality of life. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:91–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomás CC, Oliveira E, Sousa D, Uba-Chupel M, Furtado G, Rocha C et al. Proceedings of the 3rd IPLeiria’s International Health Congress: Leiria, Portugal. 6–7 May 2016. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Capuron L, Ravaud A, Dantzer R. Early depressive symptoms in cancer patients receiving interleukin 2 and/or interferon alfa-2b therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharyya S, Bhattacherjee S, Mandal T, Das DK. Depression in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in a tertiary care hospital of North Bengal, India. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61(1):14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyei K, Oswald J, Njoku A, Kyei J, Vanderpuye V. Anxiety and depression among breast cancer patients undergoing treatment in Ghana. Afr J Biomedical Res. 2020;23(2):227–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atinafu BT, Demlew TM, Tarekegn FN. Magnitude of anxiety and depression and associated factors among palliative care patients with cancer at Tikur Anbessa specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Berihun F, Haile S, Abawa M, Mulatie M, Shimeka A. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety and depression among cancer patients in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Arch Depress Anxiety. 2017;3(2):042–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tadele N. Evaluation of quality of life of adult cancer patients attending Tikur Anbessa specialized referral hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25(1):53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pienaar E, Grobler L, Busgeeth K, Eisinga A, Siegfried N. Developing a geographic search filter to identify randomised controlled trials in Africa: finding the optimal balance between sensitivity and precision. Health Inform Libr J. 2011;28(3):210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13(3):147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J Chin Integr Med. 2009;7(9):889–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y-L, Liu L, Wang Y, Wu H, Yang X-S, Wang J-N, et al. The prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darvishi N, Ghasemi H, Rahbaralam Z, Shahrjerdi P, Akbari H, Mohammadi M. The prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cancer in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(12):10273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersson A, Boström KB, Gustavsson P, Ekselius L. Which instruments to support diagnosis of depression have sufficient accuracy? A systematic review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(7):497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levis B, Yan XW, He C, Sun Y, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Comparison of depression prevalence estimates in meta-analyses based on screening tools and rating scales versus diagnostic interviews: a meta-research review. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mejareh ZN, Abdollahi B, Hoseinipalangi Z, Jeze MS, Hosseinifard H, Rafiei S, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of depression among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63(6):527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pilevarzadeh M, Amirshahi M, Afsargharehbagh R, Rafiemanesh H, Hashemi S-M, Balouchi A. Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;176:519–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azevedo MJ, Azevedo MJ. The state of health system (s) in Africa: challenges and opportunities. Historical perspectives on the state of health and health systems in Africa, volume II: the modern era. 2017:1–73.

- 42.Geremew H, Abdisa S, Mazengia EM, Tilahun WM, Tesfie TK, Endalew B. Anxiety and depression among cancer patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1341448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S. Anxiety and depression prevalence in digestive cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Supportive Palliat Care. 2023;13(e2):e235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hashemi S-M, Rafiemanesh H, Aghamohammadi T, Badakhsh M, Amirshahi M, Sari M, et al. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:166–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Megbowon ET, David OO. Information and communication technology development and health gap nexus in Africa. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1145564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ElKefi S, Asan O. How technology impacts communication between cancer patients and their health care providers: a systematic literature review. Int J Med Informatics. 2021;149:104430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1665–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith EM, Gomm S, Dickens C. Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17(6):509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belay W, Labisso WL, Tigeneh W, Kaba M. Magnitude and factors associated with anxiety and depression among patients with breast cancer in central Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:957592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahlaq S, Lahlou L, Rammouz I, Abouqal R, Belayachi J. Factors associated with psychological burden of breast cancer in women in Morocco: cross–sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones SM, Ton M, Heffner JL, Malen RC, Cohen SA, Newcomb PA. Association of financial worry with substance use, mental health, and quality of life in cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17(6):1824–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, Rhondali W, Tayjasanant S, Ochoa J, et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Oncologist. 2015;20(9):1092–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malhotra C, Harding R, Teo I, Ozdemir S, Koh GC, Neo P, et al. Financial difficulties are associated with greater total pain and suffering among patients with advanced cancer: results from the COMPASS study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3781–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abrams HR, Durbin S, Huang CX, Johnson SF, Nayak RK, Zahner GJ, et al. Financial toxicity in cancer care: origins, impact, and solutions. Translational Behav Med. 2021;11(11):2043–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Udayakumar S, Solomon E, Isaranuwatchai W, Rodin DL, Ko Y-J, Chan KK, et al. Cancer treatment-related financial toxicity experienced by patients in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(8):6463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mukherjee A, Mazumder K, Ghoshal S. Impact of different sociodemographic factors on mental health status of female cancer patients receiving chemotherapy for recurrent disease. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24(4):426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim SJ, Rha SY, Song SK, Namkoong K, Chung HC, Yoon SH, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress among Korean cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(3):246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed]

- 61.Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T. Depression in palliative care patients–a prospective study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2001;10(4):270–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Laing D, editors. Effects of acute exercise on state anxiety in breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum; 2001. [PubMed]

- 63.Ayalew M, Deribe B, Duko B, Geleta D, Bogale N, Gemechu L, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms and their determinant factors among patients with cancer in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2022;12(1):e051317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Endeshaw D, Walle TA, Yohannes S. Depression, anxiety and their associated factors among patients with cancer receiving treatment at oncology units in Amhara Region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2022;12(11):e063965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abraham Y, Fanta T. Depression and anxiety prevalence and correlations among cancer patients at Tikur Anbesa Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018: cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:939043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kulkarni S. Prevalence of Depression, anxiety, and suicidality among breast Cancer patients at Kenyatta National Hospital. Kenya: University of Nairobi; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Habimana S, Biracyaza E, Mpunga T, Nsabimana E, Nzamwita P, Jansen S. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among patients with cancer seeking treatment at the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence in Rwanda. Front Public Health. 2023;11:972360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uwayezu MG, Gishoma D, Sego R, Mukeshimana M, Collins A. Anxiety and depression among cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors at a Rwandan referral hospital. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2019;2(2):118–25. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al Bdour Z, Mohamed EA. Anxiety and depression in a sample of Disfigured Orofacial Cancer patients at Khartoum Teaching Dental Hospital, Sudan. J Adv Med Dent Sci Res. 2018;6(2):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bakhiet TE, Ali SM, Bakhiet AM. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among adult patients undergoing chemotherapy in Khartoum, Sudan: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disorders Rep. 2021;6:100218. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ebob-Anya B-A, Bassah N. Psychosocial distress and the quality of life of cancer patients in two health facilities in Cameroon. BMC Palliat care. 2022;21(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alagizy H, Soltan M, Soliman S, Hegazy N, Gohar S. Anxiety, depression and perceived stress among breast cancer patients: single institute experience. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aly H, Abd ElGhany Abd ElLateef A, El Sayed Mohamed A. Depression and anxiety among females with breast cancer in sohag university: results of an interview study. Remed Open Access 2017;2:1080.

- 74.Azizi A, Achak D, Boutib A, Chergaoui S, Saad E, Hilali A et al. Association between cervical cancer-related anxiety and depression symptoms and health-related quality of life: a Moroccan cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2023;22.

- 75.Aquil A, Azmaoui NE, Mouallif M, Guerroumi M, Zaeria H, Jayakumar AR, et al. Anxio-depressive symptoms in Moroccan women with gynecological cancer: relief factors. Bull Cancer. 2021;108(5):472–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Omari M, Amaadour L, Zarrouq B, Al-Sheikh YA, El Asri A, Kriya S, et al. Evaluation of psychological distress is essential for patients with locally advanced breast cancer prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: baseline findings from cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.letaief KSONTINIF, Lajnef I, Zenzri Y, Gabsi A, Ayadi M, Mezlini A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in breast Cancer patients in Tunisia. 2021.

- 78.Asuzu C, Adenipekun A. Correlates of depression and anxiety among the cancer patients in the radiotherapy clinic in Uch, Ibadan, Nigeria. 2015.

- 79.Alegbeleye JO, Biyi-Olutunde O. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among Gynaecological Cancer patients at a Tertiary Health Facility in Southern Nigeria. J Biosci Med. 2023;11(7):96–111. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kugbey N. Comorbid anxiety and depression among women receiving care for breast cancer: analysis of prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2022;22(3):166–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baraki AG, Tessema GM, Demeke EA. High burden of depression among cancer patients on chemotherapy in University of Gondar comprehensive hospital and Felege Hiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Belete AM, Alemagegn A, Mulu AT, Yazie TS, Bewket B, Asefa A, et al. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy during the era of COVID-19 in Ethiopia. Hospital-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(6):e0270293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saina C, Gakinya B, Songole R. Factors associated with depression amongpatients with breast cancer at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya. 2021.

- 84.Popoola AO, Adewuya AO. Prevalence and correlates of depressive disorders in outpatients with breast cancer in Lagos, Nigeria. Psycho-oncology. 2012;21(6):675–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Olagunju AT, Aina OF, Fadipe B. Screening for depression with Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Revised and its implication for consultation–liaison psychiatry practice among cancer subjects: a perspective from a developing country. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(8):1901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paul R, Musa G, Chungu H. Prevalence of depression among cervical cancer patients seeking treatment at the cancer diseases hospital. IOSR J Dent Med Sci Ver XI. 2016;15(6):2279–861. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wurjine TH, Goyteom MH. Prevalence of cancer pain, anxiety and associated factors among patients admitted to oncology ward, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia, 2019. Open J Pain Med. 2020;4(1):009–17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data is present in the manuscript.