Abstract

Background

Previous studies have examined the quality of life of patients with coeliac disease. There is a lack of understanding about potential changes in emotional responses and life challenges after diagnosis. This exploratory study aimed to evaluate the emotional impact, life challenges and quality of life in people living with coeliac disease in Germany.

Methods

An online survey was conducted among patients with coeliac disease to assess difficulties in implementing a gluten‐free diet in daily life activities, including food shopping and preparation, and eating away from home, as well as additional costs of time and money. Furthermore, the questionnaire assessed the time of diagnosis, emotions felt after diagnosis and today, compliance regarding the gluten‐free diet and sociodemographic data. Participants were recruited in 2022 via social media, newsletters and websites. Out of 1286 participants who had taken part in the survey, 766 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the data analysis.

Results

The majority of the respondents (aged 18–83 years) were female (93%) and almost 50% were diagnosed more than 5 years ago. Negative emotion ratings related to the disease were associated with age at the time of diagnosis and years passed since diagnosis. While compliance was high with 89% of respondents strictly adhering to the gluten‐free diet, patients with coeliac disease reported mainly life challenges in social situations involving food such as out‐of‐home consumption in restaurants, at work and while travelling. These challenges appear to persist over time.

Conclusions

Negative emotions and difficulties in implementing a gluten‐free diet are negatively impacting individuals with coeliac disease, particularly in the first months after diagnosis. Particularly adolescents and young adults appear to be negatively impacted. The study emphasises the need to improve the quality of life in all impacted areas through better guidance and improved training of health professionals as well as food providers outside of home and through psychological counselling in the first year of diagnosis to better help individuals improve their quality of life.

Keywords: adherence, coeliac disease, emotions, gluten‐free diet, life challenges, quality of life

This study examines life challenges, such as food purchases, food preparation, out‐of‐home consumption and emotional impact of adults living with coeliac disease in Germany.

Summary

People living with coeliac disease experience challenges across all areas of life, along with a significant emotional impact from the disease.

This survey of individuals with coeliac disease indicated that emotional coping and the ability to manage daily life activities like shopping, dining out and travelling, improve over time.

Some everyday life difficulties persist over time and appear to be more challenging when diagnosed as adolescents and young adults than as children or older adults.

Effective self‐management education, particularly when diagnosed as young adults, needs to be improved and the availability of gluten‐free meals outside of home including food provider education needs to be enhanced.

1. Introduction

Individuals living with coeliac disease have to adhere to a strict gluten‐free diet as the only treatment option [1]. When following a gluten‐free diet in a strict manner to avoid any type of cross‐contamination and accidental intake of gluten, is complex, time‐consuming, costly and negatively impacts many areas of life [2, 3].

Coeliac disease is caused by a reversible inflammatory reaction in the small bowel mucosa, which can lead to diarrhoea, constipation, bloating, nausea and vomiting, as well as non‐gastro‐intestinal symptoms, including headaches, skin rashes and joint or bone pain [1, 4]. This globally rising autoimmune condition affects about 1% of the adult population in Europe and worldwide and an estimated 0.3% of adults in Germany with a higher prevalence in children than in adults [5, 6] and a higher prevalence in women than in men [7]. The disease can occur at any age from early childhood to adulthood, with two likely onsets either in the first 2 years of life or in the second or third decades of life [1]. In the long term, if untreated, the mucosal damage and inflammation can cause weight loss and micronutrient deficiencies [8, 9]. Nevertheless, adherence to a gluten‐free diet appears to be one of the biggest challenges of the disease [10].

Not only is a gluten‐free diet currently the only available effective treatment, but various study results also indicate that strict diet compliance is associated with better coping skills, fewer depressive symptoms and overall less emotional distress compared with a less strict diet [11, 12]. It remains unclear whether improved coping and reduced depressive symptoms and distress lead to better adherence to a gluten‐free diet, or if individuals with better coping skills and fewer depressive feelings are more inclined to adhere to the diet. Enhanced emotional well‐being appears to result in improved diet adherence [13], while following a strict gluten‐free diet also seems to enhance emotional well‐being [14], suggesting a bidirectional relationship.

Research on quality of life in individuals living with coeliac disease shows associations with good adherence to a gluten‐free diet, better coping skills, less psychological distress, less clinical severity at diagnosis and better quality of life [3, 12, 15]. However, patients with coeliac disease appear to experience a lower quality of life compared with people without coeliac disease [2, 15]. They also show symptoms of depression and anxiety. A survey of adults with coeliac disease by Silvester et al. [16] reveals social isolation as the largest adverse effect of requiring a gluten‐free diet. The diagnosis of a chronic disease often leads to negative quality of life consequences, with higher risks for depressive symptoms in the first years and a decrease in symptoms over time [17].

Regarding coeliac disease, studies show emotional improvements in years 1 and 2; however, there is also evidence of persistent depressive symptoms over time [18, 19]. A prospective study with 53 patients with coeliac disease reveals improvements in quality of life from baseline at 1 year but a decline at 4 years [20], which was mainly related to poor adherence to a gluten‐free diet. In another study with children and adolescents, some areas related to quality of life slightly improve over time, while emotional and social functioning show no improvement and even a decrease for up to 10 years after diagnosis [21]. These inconsistent results could be due to the improved physical health after diagnosis, which is accompanied by feelings of relief and less emotional distress on the one hand, and the consecutive challenge during social contexts with peers, friends and family on the other, which might be related to frustration, anxiety and emotional distress [21, 22]. More than 15 years ago, Zarkadas et al. [23] published the results of a questionnaire sent to all members of both the Canadian Celiac Association and Coealique Québec. Almost 6000 respondents with biopsy‐confirmed coeliac disease reported difficulties in daily life, including the emotional impact of following a gluten‐free diet. The results show improvements in negative emotions related to the time passed since the initial diagnosis, but areas of life such as eating away from home remained difficult and frustrating. These particular challenges of out‐of‐home consumption were confirmed by studies in Greece and New Zealand [24, 25].

There are only a few studies describing the challenges of living with coeliac disease in large adult populations [23, 24, 25]. Detailed descriptions of everyday emotional and social difficulties, as well as of different life challenge domains in adults in Germany and Central Europe, are missing. Using an adapted version of the Canadian questionnaire, this study aims to evaluate the challenges of daily life following a gluten‐free diet and its emotional impact on individuals diagnosed with coeliac disease in Germany.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

Upon approval, an adapted version of the Canadian questionnaire [23] was used and translated into German. Regarding the emotions associated with following a gluten‐free diet, participants were asked to recollect their emotions experienced in the first few months after diagnosis and during the past month (at the time of the survey). A list of 10 emotions was provided for both time frames, with Likert scale answer options from ‘never’ (=1) to ‘very often’ (=5). Questions regarding difficulties and challenges experienced when following a gluten‐free diet included aspects, such as food shopping, food preparation, eating with friends and family, eating at work, restaurant visits and holidays/travel, using a 5‐point Likert scale (‘never’ (=1) to ‘very often’ (=5).

Adherence to a gluten‐free diet was assessed by asking for agreement with the statement ‘I always follow a strict gluten‐free diet’. Answer options included ‘fully agree’ to ‘fully disagree’ on a 4‐point Likert scale. Compliance with a gluten‐free diet was assessed by asking about the frequency of having consciously consumed gluten in the last year (‘never’, ‘one or two times in the last year’, ‘three or five times in the last year’, ‘every two months’, ‘once per month’, ‘weekly’).

Further questions on extra time and money spent due to the gluten‐free diet were added (‘Do you think it takes extra effort to plan a restaurant visit/to grocery shop/to prepare meals?’ Yes, about ‐insert‐ minutes; No extra effort; Not specified; ‘Do you think you have additional costs at restaurants/at the grocery store?’ Yes, about ‐insert‐ €; No additional costs; Not specified). For the three questions on quality of life and self‐perceived physical and mental health, a 5‐point Likert scale was used (‘How do you rate your overall physical/mental health/quality of life?’ bad ‐ less good ‐ good ‐ very good ‐ excellent). Self‐reported height and weight were assessed to calculate participants' BMI.

Inclusion criteria were individuals 18 years of age or older with self‐reported medically diagnosed coeliac disease, which included antigen testing or a biopsy for those diagnosed after the age of 18 years, and at least antigen testing for those diagnosed in childhood or adolescence (under the age of 18 years [26]).

From July through September of 2022, social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook were used to distribute the questionnaire. In addition to a personally created Instagram account for the study (10,200 accounts reached), 23 out of 52 contacted influencers with over 1000 followers targeting this specific population were asked to help distribute the questionnaire. Those influencers who posted the questionnaire were asked to do so again (‘story‐repost’). Additionally, the Facebook page of the German Coeliac Association (12,021 members, 6763 followers) and the group Olivers glutenfreie Welt (Olivers gluten‐free world) advertised a link to the study (29,372 members on Facebook, 5524 followers on Instagram). The German Coeliac Association also published a link to the questionnaire on their homepage (about 40,000 members). The survey software Unipark, provided by Tivian, was used to develop and distribute the questionnaire.

The final version of the questionnaire was pretested using another influencer with 448 followers and about 10 completed questionnaires. It took approximately 25 min to fill out the questionnaire.

Once potentially interested participants visited the website, they were informed about the study's purpose and procedures. In addition, information on data protection measures was given. Interested participants could indicate their approval by ticking the box indicating that they had read the data protection plan, were 18 years of age or older and wanted to participate in the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Hohenheim.

2.2. Data Analysis

Data was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 27. The results are presented as percentages or mean with standard deviation in the text and tables, and mean with 95% confidence intervals in the figures. Since not all respondents answered all questions, the sample size varies for each question. BMI was calculated using self‐reported weight and height. For this exploratory data analysis, associations between emotions and time passed since diagnosis were tested by Spearman's rho, as well as associations between compliance and time passed since diagnosis and age group. Results with an α value of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For this exploratory data analysis, associations between emotions and time passed since diagnosis were tested by Spearman's rho, as well as associations between compliance, time passed since diagnosis and age group. ANOVA with Games–Howell post‐hoc comparisons was conducted to analyse differences in emotions after diagnosis between age groups at diagnosis. T tests were conducted to analyse differences in current difficulties and challenges with respect to the time passed since diagnosis, and current emotions between compliant and noncompliant participants. Results with an α value of 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In total, the survey was viewed 2916 times, 1693 individuals started the questionnaire and 1286 completed it. Using only data from individuals over the age of 18 years who had been diagnosed by a doctor (employing antigen testing and biopsy for adults and antigen testing when diagnosed in childhood [27]), 766 respondents were included in this analysis.

Sample characteristics can be found in Table 1. More women (N = 713) than men (N = 48) participated in the survey (three considered themselves a diverse gender, and one did not provide information regarding gender), and 47.1% of the sample received their diagnosis more than 5 years ago. While the mean age at the time of diagnosis was about 24 years, 20.6% were diagnosed before the age of 15 years, 48.6% between the ages of 16 and 29 years and 30.8% after the age of 30 years. Adherence to a gluten‐free diet was high, with 89.0% reporting they always follow a gluten‐free diet. While 87.8% of the participants indicated they had been compliant in the last year, 6.8% indicated they had not been compliant once or twice in the last year, 2.3% indicated they had not been compliant three to five times in the last year and only three participants reported eating gluten weekly.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Mean age (±SD) in years (N = 766) | 31.89 ± 11.16 | Range 18–83 |

| Female (%) (N = 765) | 93.0 | |

| BMI (%) (N = 746) | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 7.1 | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.99) | 67.2 | |

| Overweight (25–29.99) | 19.1 | |

| Obese (30+) | 6.2 | |

| How long ago did you start with your gluten‐free diet? (%) (N = 765) | ||

| Less than 6 months | 38 (5.0) | |

| 6–12 months | 62 (8.1) | |

| 1–2 years | 106 (13.9) | |

| 2–5 years | 199 (26.0) | |

| 5+ years | 360 (47.1) | |

| Mean age (±SD) at diagnosis in years (N = 766) | 24.8 ± 12.1 | Range 1–70 |

| Strict adherence (yes) (%) (N = 766) | 89.0 | |

| Strict compliance (‘never uncompliant’) (%) (N = 764) | 87.8 |

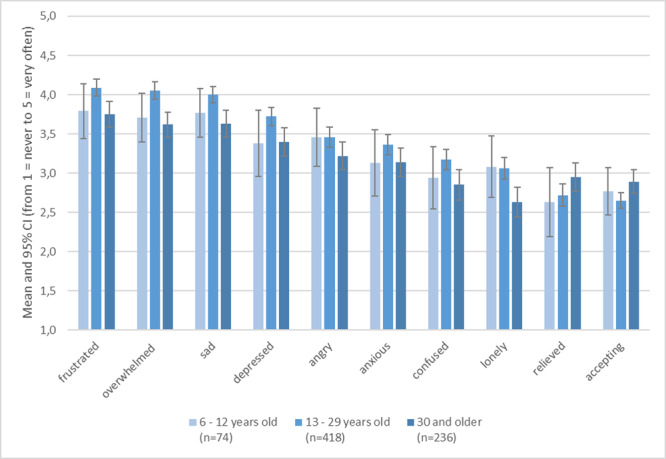

The self‐reported emotional impact during the first few months after diagnosis was divided into age groups at the time of diagnosis and is reported in Figure 1. Participants who were older at the time of diagnosis showed milder negative emotions and appeared to be more accepting of the diagnosis than younger participants. The adolescent and young adult group showed the strongest negative emotions regarding their diagnosis. The differences are significant for the following emotions: frustrated (F(2,677) = 7.110, p < 0.001), overwhelmed (F(2,677) = 10.531, p < 0.001), sad (F(2,675) = 7.408, p < 0.001), depressed (F(2,675) = 5.105, p = 0.006), confused (F(2,673) = 4.134, p = 0.016), lonely (F(2,676) = 7.155, p < 0.001) and accepting (F(2,671) = 3.631, p = 0.027). Post hoc procedures (Games–Howell) showed that these differences were significant only between the age groups ‘13–29’ and ‘30 and older’.

Figure 1.

Mean emotional impact ratings (1,0 = never to 5,0 = very often) experienced in the first few months after diagnosis by age group at the time of diagnosis (without those diagnosed under the age of 6 years).

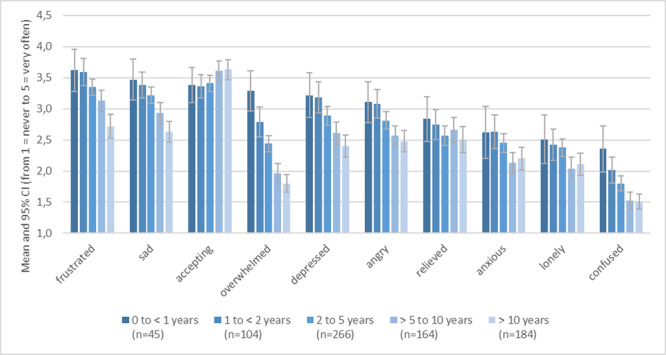

Figure 2 reports the changes in (mean) emotions during the month before the survey, depending on the time since diagnosis. These emotions appeared to decline as more time passed, while the feeling of acceptance increased. Except for the feeling ‘relieved’, all other emotions showed a significant association (p ≤ 0.001) with time passed since diagnosis (Spearman's rho is between −0.361 for ‘overstrained’ and −0.123 for ‘lonely’, the only significant positive value is 0.129 for ‘accepting’).

Figure 2.

Mean emotional impact ratings (1,0 = never to 5,0 = very often) experienced in the last month before taking the survey by years passed since diagnosis.

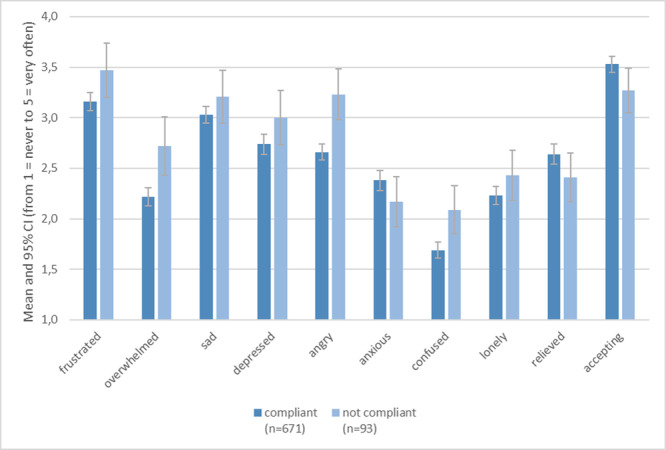

While the large majority of participants described themselves as compliant, an examination of the relationship between emotional impact and compliance showed higher impact ratings in noncompliant participants (see Figure 3). Significant emotional differences between compliant and noncompliant participants were found, with less compliant participants being angrier (p < 0.001), more often overwhelmed (p = 0.001), confused (p = 0.002), frustrated (p = 0.033) and less accepting (p = 0.025).

Figure 3.

Mean recent emotional impact ratings due to following a gluten‐free diet by compliance or noncompliance with a gluten‐free diet.

Regarding the time since diagnosis, the largest percentage of noncompliance could be found in the first year following diagnosis, with 29.5% of the participants belonging to this group indicating that they did not always comply with a strict gluten‐free diet. The group with the highest compliance ratings consisted of individuals diagnosed 5–10 years ago (92.2%), followed by those diagnosed 2–5 years ago (89.8%) and 1–2 years ago (88.5%). Additionally, 86.1% of those aged 20–29 were classified as adherent, while 95.3% of participants over the age of 50 adhered to a gluten‐free diet. Overall, age group was positively associated with adherence (ρ = 0.076, p = 0.035) and compliance (ρ = 0.136, p < 0.001).

3.1. Challenges Due to the Gluten‐Free Diet

The mean additional time needed to prepare food due to dietary restrictions was about 85 min per week (N = 379), while the mean extra time spent shopping was about 31 min per week (N = 581), with additional costs varying widely among participants. The mean additional amount of money in Euros spent per week was 34.59 € (median: 25.00 €; N = 709), but some participants reported spending up to 250 € more per week. The most frequently reported additional cost was 20 € more per week. Furthermore, a large majority of participants reported incurring additional time and expenses when eating out. The mean additional time required to ensure a gluten‐free meal at restaurants (e.g., planning ahead and speaking with restaurant personnel) was about 26 min per restaurant visit (N = 555). Moreover, the mean additional expense was 7 € (median: 5 €; N = 523).

Table 2 reports the challenges experienced and strategies used by participants in different areas of life, including food purchases, food preparation, social settings, while travelling/vacationing, as well as self‐reported health and overall quality of life. Additional items can be found in Table A1.

Table 2.

Current difficulties and challenges experienced when following a gluten‐free (GF) diet (in %, total N = 766) of participants with ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 721) and of participants with < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45).

| ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 721) | < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never/rarely | Sometimes | Often/very often | Never/rarely | Sometimes | Often/very often | |

| Food purchases | ||||||

| Hard to tell from the ingredient list if a packaged food is GF** | 75.8 | 16.6 | 7.6 | 62.2 | 15.6 | 22.3 |

| I can find a variety of GF foods in local stores | 2.1 | 18.5 | 79.4 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 80.0 |

| Resent time needed to read all ingredient lists** | 41.5 | 33.5 | 25.1 | 20.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Frustrated with the variety of names for gluten on food labels** | 54.4 | 24.3 | 21.4 | 36.3 | 29.5 | 34.1 |

| Food preparation | ||||||

| Difficult to prepare both GF and gluten‐containing meals | 35.0 | 23.8 | 41.2 | 40.0 | 23.3 | 36.6 |

| Frustrating to bake with GF flours in favourite recipes** | 43.9 | 27.3 | 28.9 | 21.4 | 26.2 | 52.4 |

| Limited GF choices for carried lunches | 10.7 | 24.1 | 65.2 | 7.0 | 23.3 | 69.8 |

| GF meals are more difficult to prepare** | 46.0 | 34.1 | 19.9 | 33.3 | 31.1 | 35.6 |

| Have to cook more often | 20.5 | 10.7 | 68.8 | 29.6 | 9.1 | 61.4 |

| Enjoy the challenge of making GF foods* | 36.0 | 34.5 | 29.5 | 50.0 | 38.6 | 11.3 |

| I only cook gluten‐free for the whole family | 13.0 | 13.8 | 73.3 | 25.0 | 9.1 | 65.9 |

| I store gluten‐free foods in a separate area* | 13.4 | 4.6 | 82.0 | 22.7 | 11.4 | 65.9 |

| Eating with friends/family | ||||||

| My friends understand my dietary needs | 5.2 | 24.5 | 70.3 | 8.9 | 24.4 | 66.6 |

| People think a little gluten will not hurt me | 44.6 | 26.0 | 29.4 | 37.8 | 26.7 | 35.6 |

| Embarrassed by my dietary needs | 44.6 | 26.0 | 29.4 | 37.8 | 26.7 | 35.6 |

| Feel that I am a burden | 13.8 | 27.6 | 58.6 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 66.7 |

| Bring my own food when visiting | 7.3 | 26.0 | 66.7 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 75.0 |

| Hard to ask others to accommodate my GF diet | 29.7 | 27.6 | 42.8 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 44.4 |

| Avoid going to social events involving food | 32.4 | 35.5 | 32.0 | 36.4 | 31.8 | 31.8 |

| Check ingredient lists on the foods I eat when at family/friends | 12.2 | 16.6 | 71.2 | 14.2 | 11.9 | 73.9 |

| Do not like others to feel sorry for me | 12.8 | 18.0 | 69.3 | 26.7 | 17.8 | 55.6 |

| Find it difficult to refuse gluten‐containing foods offered to me | 74.9 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 73.4 | 15.6 | 11.1 |

| Invite friends/family to eat at my home instead of going to a restaurant | 16.7 | 20.2 | 63.0 | 13.3 | 22.2 | 64.4 |

| Eating at school/work | ||||||

| GF meals are available | 80.0 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 82.1 | 14.3 | 3.6 |

| Difficult to bring own food | 44.5 | 37.3 | 18.2 | 47.5 | 35.0 | 17.5 |

| Embarrassed about my GF diet | 52.0 | 25.9 | 22.1 | 47.5 | 20.0 | 32.5 |

| Feeling left out because of my GF diet | 25.9 | 42.8 | 31.3 | 29.7 | 32.4 | 37.8 |

| Difficult for me to be the centre of attention because of my GF diet | 11.9 | 21.1 | 67.0 | 18.0 | 25.6 | 56.4 |

| Have snacks on hand | 5.5 | 15.8 | 78.8 | 5.0 | 20.0 | 75.0 |

| Talk to others about coeliac disease and the GF diet | 9.8 | 35.3 | 55.0 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 67.5 |

| Business meals/events stress me | 7.2 | 20.2 | 72.6 | 3.3 | 23.3 | 73.3 |

| If an event involves food, remind people about my GF diet | 24.8 | 22.4 | 52.8 | 30.5 | 33.3 | 36.1 |

| Offer to bring a GF dish to events involving food | 10.0 | 17.4 | 72.7 | 7.9 | 26.3 | 65.8 |

| Restaurant visits | ||||||

| Limited restaurant choices | 2.1 | 8.2 | 89.7 | 2.3 | 15.9 | 81.8 |

| Frustrated because of limited choices in the restaurant | 8.7 | 24.0 | 50.4 | 8.9 | 24.4 | 66.7 |

| Enquire about the gluten content of all foods (incl. seasoning sauces) | 27.2 | 13.5 | 59.2 | 27.9 | 16.3 | 55.8 |

| Worry about the cook's knowledge of how to prepare GF food | 7.7 | 18.5 | 73.8 | 8.9 | 20.0 | 71.1 |

| Use the internet to find restaurants that serve GF foods | 3.0 | 8.7 | 88.3 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 88.8 |

| Limited choices at fast food restaurants | 1.8 | 6.9 | 91.3 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 94.9 |

| Enjoy going out to eat as much as I did before my GF diet | 66.7 | 18.0 | 15.3 | 72.7 | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| Travelling | ||||||

| Worry about travelling because of my dietary restrictions | 39.6 | 30.5 | 29.9 | 29.3 | 43.9 | 26.8 |

| Enjoy travelling as much as I did before my GF diet | 42.8 | 21.9 | 35.5 | 45.0 | 27.5 | 27.5 |

| Difficult to bring own GF food while travelling | 19.7 | 35.9 | 44.5 | 13.2 | 31.6 | 55.2 |

| Worry that I cannot find GF foods while travelling* | 18.1 | 26.5 | 55.5 | 4.7 | 27.9 | 67.4 |

| Sad that I cannot eat many of the local food specialties | 7.8 | 14.7 | 77.5 | 2.6 | 18.4 | 78.9 |

| Embarrassed to ask for GF food everywhere while travelling | 27.8 | 24.8 | 47.5 | 17.9 | 25.6 | 56.4 |

| Travelling abroad is difficult because I cannot read the packages to determine if the food is gluten‐free | 31.3 | 35.2 | 33.4 | 25.8 | 35.5 | 38.7 |

| Others | ||||||

| Feel guilty when thinking about possibly passing the disease on to my children/grandchildrena | 37.2 | 22.8 | 33.7 | 26.7 | 22.2 | 40.0 |

| Feel in control of my GF diet** | 1.0 | 7.4 | 91.2 | 2.2 | 28.9 | 68.9 |

Abbreviation: GF, gluten‐free.

Data omitted for ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (n = 45) and for < 1 year passed since diagnosis (n = 5).

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01 (T test).

The challenges associated with food purchases primarily involve concerns about the accuracy of label information and the presence of numerous unfamiliar ingredients that contain gluten. In the area of food preparation, the extra time spent cooking and worries about contamination were widely apparent. Most challenges were observed in social settings. Over 66% of the participants indicated that other people think a little gluten will not hurt them. Moreover, feelings of being a burden, drawing attention and being embarrassed about their dietary restrictions were common. Finding food and meals outside the home was described as difficult by the majority of participants, particularly in work/school settings. Limited restaurant choices and meal options in restaurants, along with concerns about correct preparation and potential contamination by restaurant personnel, were stated issues. Participants saw it as their responsibility to inform others and to be as well informed as possible whenever necessary. They often searched the internet or asked for information from fellow patients with coeliac disease. Almost 43% of the participants reported no longer enjoying travelling as much as they did before their diagnosis, and over 75% indicated they were often/very often sad that they could not try local food specialities on holidays or while travelling. While quality of life and physical health were described as good, very good or excellent by the majority of the participants (over 80% of the respondents), over 26% reported their mental health as fair or poor.

The last column of Table 2 clearly shows the higher ratings of perceived and experienced difficulties based on the years since diagnosis. The first 12 months appeared to be particularly difficult with regard to learning about gluten‐containing products, correct and tasty preparation of gluten‐free foods, communication with others and overall gaining control over the changed lifestyle. Interestingly, other areas of life seemed to remain challenging throughout the years, such as the lack of variety and choices in gluten‐free products and (restaurant) meals, the extra time spent cooking meals, bringing along meals and snacks and eating while travelling.

Comparing participants who recently received a diagnosis of coeliac disease (< 1 year) with those who were diagnosed more than 1 year ago revealed significantly lower ratings in self‐reported physical (M = 2.98, SD = 0.81 vs. M = 3.24, SD = 0.82; t(764) = −2.061, p = 0.04) and mental health (M = 2.80, SD = 0.89 vs. M = 3.19, SD = 0.92; t(765) = −2. 128, p = 0.34) but no differences in quality of life (M = 3.20, SD = 0.73 vs. M = 3.37, SD = 0.82) as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Self‐reported rating of physical and mental health as well as quality of life (in %, total N = 765) of participants with ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 721) and of participants with < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45).

| ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 720) | < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Bad/less good | Good | Very good/excellent | Bad/less good | Good | Very good/excellent |

| Physical health | 16.7 | 46.3 | 37.1 | 26.7 | 48.9 | 24.4 |

| Mental health | 25.4 | 42.2 | 32.4 | 35.6 | 44.4 | 20.0 |

| Quality of life | 12.4 | 45.7 | 42.0 | 13.3 | 57.8 | 28.8 |

4. Discussion

This is the first study to explore the emotional impact and the self‐reported current and past challenges of individuals diagnosed with coeliac disease in Germany. The results show that negative emotions seem less pronounced in people diagnosed a long time ago, which could be explained by the use of coping strategies such as the continuous gathering of more information regarding disease management and accepting their reduced choices, particularly outside home. This finding has also been confirmed by the Canadian study that served as the foundation for this study [23], and more generally by a study in Portugal where age at onset was negatively associated with the social domain of a quality of life questionnaire [28]. In addition, successfully managing chronic diseases seems to be influenced by disease acceptance and health literacy [28, 29, 30]. However, as this and other studies have found, while coping mechanisms and resilience might be activated, a substantial proportion of people with coeliac disease still experience ongoing negative emotions, particularly regarding certain areas of life, such as away‐from‐home consumption [16, 24, 31].

Furthermore, receiving a diagnosis at an early age is not only beneficial for preventing further health complications and comorbidities [32, 33], but it also seems that the emotional strain both at the time of diagnosis and throughout the years is reduced [34]. However, the risk of eating disorders seems higher in paediatric chronic disorders [35], including gastrointestinal disorders [36] and specifically coeliac disease [37, 38]. Various studies show maladaptive eating behaviours in adolescents with coeliac disease [39, 40]. Since coeliac disease appears to precede the development of eating disorders by almost 10 years [41], the critical teenage years might be particularly challenging for teenagers with coeliac disease, and our results seem to indicate that a diagnosis during adolescence and young adulthood might be related to a stronger negative emotional impact [42]. A study with adolescents revealed more problems at school and in peer interactions with late coeliac disease diagnosis [43]. Given the impact of a gluten‐free diet on people's social life, it seems apparent why this age group is affected the most [29, 31].

Consistent with other studies [44, 45], adherence to a strict gluten‐free diet in this study seems to be associated with the person's age and a reduced negative emotional impact of following the diet. The older participants seemed to have better dietary compliance. The direction of the relationship of emotional impact and compliance, however, remains unknown. It is possible that emotional stability and resilience promote compliance [13, 46], but it is also possible that compliance supports the feelings of control and with it improves patients' emotional states [47].

The results of this study show an average increase in financial costs of almost 35 € per week. Other studies confirm the economic burden of the disease [48, 49]. The increased costs for grocery shopping can be a burden not only for lower socioeconomic households but also for households with more than one person with coeliac disease and for households where all members decide to eat gluten‐free to support their family members with coeliac disease. Worries about the financial constraints when purchasing gluten‐free food can, in itself, impact the quality of life [50].

Quality of life seems to be particularly impacted by the disease in the first years after diagnosis. In our study, only about one‐quarter of the participants who were recently diagnosed described their quality of life as very good to excellent, while over 42% of the remaining sample indicated very good or excellent quality of life. Similar results are observed in other studies, including a study conducted in Italy that found lower ratings on a ‘health concern’ subscale in individuals with coeliac disease aged more than 35 years compared with younger individuals [51]. Other studies show a negative relationship between both stress and quality of life, as well as emotion‐focused coping and quality of life in patients with coeliac disease [52], with better scores depending on the time passed since the diagnosis [44, 45]. Furthermore, studies reveal associations between hypervigilance in following a gluten‐free diet, dysphoria and lower quality of life [53, 54]. It is possible that similar challenges in maintaining a strict diet arise during the initial months following a diagnosis.

Examining specific life challenges and situational difficulties not only shows improvement of these difficulties over time, but it also indicates that some challenges and frustrating circumstances appear to persist. These areas are mainly centred around other people's limited knowledge of coeliac disease and its management, the availability of gluten‐free food and the lack of variety in gluten‐free options during out‐of‐home consumption, including work‐related events, holidays or restaurant visits. The fact that over 60% of participants agreed with the statement that people think a little bit of gluten will not harm them highlights a lack of knowledge in the general population, which may be fuelled by the hype surrounding gluten‐free products consumed for reasons other than coeliac disease [55]. While the popular trend of not consuming gluten is beneficial in terms of increased availability and variety of gluten‐free products, it also seems to cause misconceptions and confusion between choosing to eat a gluten‐free diet and the physiological requirement to strictly avoid gluten. Increased public education about the disease, particularly in the out‐of‐home/catering industry, is necessary to reduce patients' negative emotions and their health risks. Particularly, supporting young adults in the first year after their diagnosis, helping them cope with challenges and facilitating adjustments required by this disease may be necessary steps to prevent future health complications and disease (e.g., depression, eating disorders).

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Present Study

While this study managed to reach a large number of people with coeliac disease in Germany, it is not a representative sample of the general German population with coeliac disease, and women are overrepresented. In general, using self‐reports is prone to response and recall bias, with the potential for over‐ and underreporting. This might have been the case for the recall of emotions during the first months after diagnosis. The recall of emotions might have also been influenced by how long ago the diagnosis was made at the time of the survey. Additionally, not all questions were validated or have been used in previous studies, which would strengthen the validity of the results. However, using both social media and the platform of the German Coeliac Association as recruitment tools can be considered a strength of the study.

5. Conclusions

Coeliac disease greatly impacts all aspects of patients' lives. Various connected aspects, such as the emotional impact of following a strict gluten‐free diet, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, compliance, financial means and out‐of‐home consumption, all influence the quality of life for individuals with coeliac disease. Out‐of‐home consumption at work, in restaurants, and even abroad seems to be one the most challenging areas of life. Also, the first year after diagnosis, especially if diagnosed as a teenager or young adult, appears to be a critical aspect of managing coeliac disease that should be examined closely and addressed in future research. Supporting individuals with coeliac disease by improving the availability of gluten‐free meals away from home could be a potential strategy to decrease negative feelings and reduce challenges. Emphasising psychological counselling during the first year after diagnosis, particularly for young adults, could be crucial. By assisting them in managing challenges and facilitating the necessary adjustments that accompany this disease, counsellors can help prevent potential future health complications and conditions, such as depression and eating disorders, and possibly enhance their quality of life [56].

Author Contributions

C.R. and A.D. developed and carried out the questionnaire. N.S.B. wrote the manuscript and analysed the data with support from A.B. C.R. and A.D. provided feedback for the manuscript. N.S.B. supervised the project. No generative AI and AI‐assisted technologies were used in the writing process.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Hohenheim. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/jhn.13413.

Transparency Declaration

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported. The lead author affirms that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the Canadian Celiac Association for the provision of their questionnaire. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

1.

Table A1.

Additional current difficulties and challenges experienced when following a gluten‐free (GF) diet (in %, total N = 766) of participants with ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 721) and of participants with < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45).

| ≥ 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 721) | < 1 year passed since diagnosis (N = 45) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never/rarely | Some‐times | Often/very often | Never/rarely | Some‐times | Often/very often | |

| Food purchases | ||||||

| Annoyed at having to contact companies if products are GF | 49.0 | 16.9 | 34.3 | 50.0 | 22.2 | 27.8 |

| Think that GF information from companies may not be correct | 56.0 | 29.2 | 14.8 | 41.9 | 41.9 | 16.3 |

| Food preparation | ||||||

| Worry about making mistakes with the GF diet** | 55.0 | 23.9 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 35.6 | 44.4 |

| Make and freeze extra gluten‐free meals* | 46.2 | 32.6 | 21.3 | 60.5 | 27.9 | 11.7 |

| Eating with friends/family | ||||||

| My family understands my dietary needs* | 4.6 | 12.4 | 83.0 | 4.4 | 24.4 | 71.1 |

| Suspect that family/friends are afraid to invite me for meals | 48.8 | 27.3 | 23.9 | 31.0 | 42.9 | 26.2 |

| Feel neglected because of my dietary needs | 39.1 | 33.1 | 27.7 | 34.9 | 27.9 | 37.2 |

| Share my best GF recipes* | 33.2 | 30.9 | 36.0 | 48.8 | 24.4 | 26.8 |

| It is easier to take charge of meals | 6.1 | 16.8 | 77.0 | 6.8 | 11.4 | 81.9 |

| Restaurant visits | ||||||

| Call ahead to enquire about GF menu choices | 24.8 | 24.9 | 50.3 | 34.1 | 27.3 | 38.6 |

| Cannot go to restaurants because meals could be contaminated | 45.5 | 23.0 | 30.4 | 42.1 | 39.5 | 18.5 |

| Restaurants in my area manage to provide correct information about gluten in their meals | 44.1 | 34.3 | 21.7 | 27.9 | 51.2 | 20.9 |

| Dislike the assumption that I am responsible for choosing a restaurant | 18.3 | 27.6 | 54.1 | 22.2 | 31.1 | 46.6 |

| Ask for printed information about gluten content | 35.2 | 16.6 | 48.2 | 46.2 | 17.9 | 35.8 |

| Look for recommendations by others with CD for appropriate restaurants | 8.4 | 21.0 | 70.6 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 75.0 |

| Travelling | ||||||

| Look for recommendations by others with CD for an appropriate holiday destination | 27.2 | 22.6 | 50.2 | 39.5 | 18.4 | 42.2 |

| Take translated information about the GF diet when abroad | 36.5 | 17.4 | 46.1 | 4.7 | 27.9 | 67.4 |

| Research restaurants on the internet before I leave home | 6.9 | 10.4 | 82.8 | 2.3 | 20.9 | 76.7 |

| Contact the local Coeliac Society about sources of GF foods | 86.9 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 90.9 | 0.0 | 9.1 |

| Carry a doctor's letter indicating that I require a GF diet | 85.9 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 13.2 | 31.6 | 55.2 |

| My GF diet restricts the countries I travel to | 35.4 | 24.9 | 39.7 | 51.5 | 21.2 | 27.3 |

Abbreviations: CD, coeliac disease; GF, gluten‐free.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01 (T test).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Caio G., Volta U., Sapone A., et al., “Celiac Disease: A Comprehensive Current Review,” BMC Medicine 17 (2019): 142, 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Möller S. P., Hayes B., Wilding H., Apputhurai P., Tye‐Din J. A., and Knowles S. R., “Systematic Review: Exploration of the Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Quality of Life in Adults Living With Coeliac Disease,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 147 (2021): 110537, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee A. R., Ng D. L., Diamond B., Ciaccio E. J., and Green P. H. R., “Living With Coeliac Disease: Survey Results From the U.S.A,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 25, no. 3 (2012): 233–238, 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gujral N., “Celiac Disease: Prevalence, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis and Treatment,” World Journal of Gastroenterology 18 (2012): 6036–6059, 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh P., Arora A., Strand T. A., et al., “Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16, no. 6 (2018): 823–836.e2, 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mustalahti K., Catassi C., Reunanen A., et al., “The Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Europe: Results of a Centralized, International Mass Screening Project,” Annals of Medicine 42, no. 8 (2010): 587–595, 10.3109/07853890.2010.505931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. King J. A., Jeong J., Underwood F. E., et al., “Incidence of Celiac Disease is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 115 (2020): 507–525, 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rondanelli M., Faliva M. A., Gasparri C., et al., “Micronutrients Dietary Supplementation Advices for Celiac Patients on Long‐Term Gluten‐Free Diet With Good Compliance: A Review,” Medicina 55 (2019): 337, 10.3390/medicina55070337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kreutz J. M., Adriaanse M. P. M., Van Der Ploeg E. M. C., and Vreugdenhil A. C. E., “Narrative Review: Nutrient Deficiencies in Adults and Children With Treated and Untreated Celiac Disease,” Nutrients 12 (2020): 500, 10.3390/nu12020500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aljada B., Zohni A., and El Matary W., “The Gluten‐Free Diet for Celiac Disease and Beyond,” Nutrients 13, no. 11 (2021): 3993, 10.3390/nu13113993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sainsbury K. and Marques M. M., “The Relationship Between Gluten Free Diet Adherence and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Coeliac Disease: A Systematic Review With Meta‐Analysis,” Appetite 120 (2018): 578–588, 10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sainsbury K., Halmos E. P., Knowles S., Mullan B., and Tye‐Din J. A., “Maintenance of a Gluten Free Diet in Coeliac Disease: The Roles of Self‐Regulation, Habit, Psychological Resources, Motivation, Support, and Goal Priority,” Appetite 125 (2018): 356–366, 10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dimidi E., Kabir B., Singh J., et al., “Predictors of Adherence to a Gluten‐Free Diet in Celiac Disease: Do Knowledge, Attitudes, Experiences, Symptoms, and Quality of Life Play a Role?,” Nutrition 90 (2021): 111249, 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halmos E. P., Deng M., Knowles S. R., Sainsbury K., Mullan B., and Tye‐Din J. A., “Food Knowledge and Psychological State Predict Adherence to a Gluten‐Free Diet in a Survey of 5310 Australians and New Zealanders With Coeliac Disease,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 48, no. 1 (2018): 78–86, 10.1111/apt.14791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nachman F., Mauriño E., Vázquez H., et al., “Quality of Life in Celiac Disease Patients,” Digestive and Liver Disease 41, no. 1 (2009): 15–25, 10.1016/j.dld.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silvester J. A., Weiten D., Graff L. A., Walker J. R., and Duerksen D. R., “Living Gluten‐Free: Adherence, Knowledge, Lifestyle Adaptations and Feelings Towards a Gluten‐Free Diet,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 29, no. 3 (2016): 374–382, 10.1111/jhn.12316h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Polsky D., Doshi J. A., Marcus S., et al., “Long‐Term Risk for Depressive Symptoms After a Medical Diagnosis,” Archives of Internal Medicine 165, no. 11 (2005): 1260–1266, 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zingone F., Siniscalchi M., Capone P., et al., “The Quality of Sleep in Patients With Coeliac Disease,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 32, no. 8 (2010): 1031–1036, 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Canova C., Rosato I., Marsilio I., et al., “Quality of Life and Psychological Disorders in Coeliac Disease: A Prospective Multicentre Study,” Nutrients 13, no. 9 (2021): 3233, 10.3390/nu13093233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nachman F., del Campo M. P., González A., et al., “Long‐Term Deterioration of Quality of Life in Adult Patients With Celiac Disease Is Associated With Treatment Noncompliance,” Digestive and Liver Disease 42, no. 10 (2010): 685–691, 10.1016/j.dld.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crocco M., Malerba F., Calvi A., et al., “Health‐Related Quality of Life in Children With Coeliac Disease and in Their Families: A Long‐Term Follow‐Up Study,” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 78, no. 1 (2024): 105–112, 10.1002/jpn3.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wagner G., Berger G., Sinnreich U., et al., “Quality of Life in Adolescents With Treated Coeliac Disease: Influence of Compliance and age at Diagnosis,” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 47, no. 5 (2008): 555–561, 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817fcb56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zarkadas M., Dubois S., MacIsaac K., et al., “Living With Coeliac Disease and a Gluten‐Free Diet: A Canadian Perspective,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 26, no. 1 (2013): 10–23, 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aspasia S., Emmanuela‐Kalliopi K., Nikolaos T., Eirini S., Ioannis S., and Anastasia M., “The Gluten‐Free Diet Challenge in Adults With Coeliac Disease: The Hellenic Survey,” PEC Innovation 1 (2022): 100037, 10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharp K., Walker H., and Coppell K. J., “Coeliac Disease and the Gluten‐Free Diet in New Zealand: The New Zealand Coeliac Health Survey,” Nutrition & Dietetics/Nutrition and Dietetics 71, no. 4 (2014): 223–228, 10.1111/1747-0080.12105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Werkstetter K. J., Korponay‐Szabó I. R., Popp A., et al., “Accuracy in Diagnosis of Celiac Disease Without Biopsies in Clinical Practice,” Gastroenterology 153, no. 4 (2017): 924–935, 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaves C., Raposo A., Zandonadi R. P., Nakano E. Y., Ramos F., and Teixeira‐Lemos E., “Quality of Life Perception Among Portuguese Celiac Patients: A Cross‐Sectional Study Using the Celiac Disease Questionnaire (CDQ),” Nutrients 15, no. 9 (2023): 2051, 10.3390/nu15092051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qiu C., Zhang X., Zang X., and Zhao Y., “Acceptance of Illness Mediate the Effects of Health Literacy on Self‐Management Behaviour,” European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 19, no. 5 (2020): 411–420, 10.1177/1474515119885240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wysocki G., Czapla M., Uchmanowicz B., et al., “Influence of Disease Acceptance on the Quality of Life of Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis – Single Centre Study,” Patient Preference and Adherence 17 (2023): 1075–1092, 10.2147/PPA.S403437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeanes Y. M., Kallos S., Muhammad H., and Reeves S., “Who Gets an Annual Review for Coeliac Disease? Patients With Lower Health Literacy and Lower Dietary Adherence Consider Them Important,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 37 (2024): 1022–1031, 10.1111/jhn.13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bathrellou E., Georgopoulou A., and Kontogianni M., “Perceived Barriers to Gluten‐Free Diet Adherence by People With Celiac Disease in Greece,” Annals of Gastroenterology 36, no. 3 (2023): 287–292, 10.20524/aog.2023.0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paarlahti P., Kurppa K., Ukkola A., et al., “Predictors of Persistent Symptoms and Reduced Quality of Life in Treated Coeliac Disease Patients: A Large Cross‐Sectional Study,” BMC Gastroenterology 13 (2013): 75, 10.1186/1471-230X-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. H. L., G. E., and S. L., “Better Dietary Compliance in Patients With Coeliac Disease Diagnosed in Early Childhood,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 38 (2003): 751–754, 10.1080/00365520310003318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meyer S. and Lamash L., “Illness Identity in Adolescents With Celiac Disease,” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 72 (2021): e42–e47, 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quick V. M., Byrd‐Bredbenner C., and Neumark‐Sztainer D., “Chronic Illness and Disordered Eating: A Discussion of the Literature,” Advances in Nutrition 4, no. 3 (2013): 277–286, 10.3945/an.112.003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Satherley R., Howard R., and Higgs S., “Disordered Eating Practices in Gastrointestinal Disorders,” Appetite 84 (2015): 240–250, 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mazzone L., Reale L., Spina M., et al., “Compliant Gluten‐Free Children With Celiac Disease: An Evaluation of Psychological Distress,” BMC Pediatrics 11 (2011): 46, 10.1186/1471-2431-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cadenhead J. W., Wolf R. L., Lebwohl B., et al., “Diminished Quality of Life Among Adolescents With Coeliac Disease Using Maladaptive Eating Behaviours to Manage a Gluten‐Free Diet: A Cross‐Sectional, Mixed‐Methods Study,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 32, no. 3 (2019): 311–320, 10.1111/jhn.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tokatly Latzer I., Lerner‐Geva L., Stein D., Weiss B., and Pinhas‐Hamiel O., “Disordered Eating Behaviors in Adolescents With Celiac Disease,” Eating and Weight Disorders ‐ Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 25, no. 2 (2020): 365–371, 10.1007/s40519-018-0605-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conviser J. H., Fisher S. D., and McColley S. A., “Are Children With Chronic Illnesses Requiring Dietary Therapy at Risk for Disordered Eating or Eating Disorders? A Systematic Review,” International Journal of Eating Disorders 51, no. 3 (2018): 187–213, 10.1002/eat.22831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karwautz A., Wagner G., Berger G., Sinnreich U., Grylli V., and Huber W. D., “Eating Pathology in Adolescents With Celiac Disease,” Psychosomatics 49, no. 5 (2008t): 399–406, 10.1176/appi.psy.49.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wheeler M., David A. L., Kennedy J., and Knight M., “I Sort of Never Felt Like I Should be Worried About it or That I Could be Worried About it’” An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Perceived Barriers to Disclosure by Young People With Coeliac Disease,” British Journal of Health Psychology 27, no. 4 (2022): 1296–1313, 10.1111/bjhp.12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wagner G., Berger G., Sinnreich U., et al., “Quality of Life in Adolescents With Treated Coeliac Disease: Influence of Compliance and age at Diagnosis,” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 47, no. 5 (2008): 555–561, 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817fcb56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fueyo‐Díaz R., Montoro M., Magallón‐Botaya R., et al., “Influence of Compliance to Diet and Self‐Efficacy Expectation on Quality of Life in Patients With Celiac Disease in Spain,” Nutrients 12, no. 9 (2020): 2672, 10.3390/nu12092672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Rosa A., Troncone A., Vacca M., and Ciacci C., “Characteristics and Quality of Illness Behavior in Celiac Disease,” Psychosomatics 45, no. 4 (2004): 336–342, 10.1176/appi.psy.45.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jin Y., Bhattarai M., Kuo W., and Bratzke L. C., “Relationship Between Resilience and Self‐Care in People With Chronic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 32 (2023): 2041–2055, 10.1111/jocn.16258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barberis N., Quattropani M. C., and Cuzzocrea F., “Relationship Between Motivation, Adherence to Diet, Anxiety Symptoms, Depression Symptoms and Quality of Life in Individuals With Celiac Disease,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 124 (2019): 109787, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stevens L. and Rashid M., “Gluten‐Free and Regular Foods: A Cost Comparison,” Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research 69 (2008): 147–150, 10.3148/69.3.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singh J. and Whelan K., “Limited Availability and Higher Cost of Gluten‐Free Foods,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 24 (2011): 479–486, 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zysk W., Głąbska D., and Guzek D., “Social and Emotional Fears and Worries Influencing the Quality of Life of Female Celiac Disease Patients Following a Gluten‐Free Diet,” Nutrients 10, no. 10 (2018): 1414, 10.3390/nu10101414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marsilio I., Canova C., D'Odorico A., et al., “Quality‐of‐Life Evaluation in Coeliac Patients on a Gluten‐Free Diet,” Nutrients 12, no. 10 (2020): 2981, 10.3390/nu12102981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith M. M. and Goodfellow L., “The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Coping Strategies of Adults With Celiac Disease Adhering to a Gluten‐Free Diet,” Gastroenterology Nursing 34, no. 6 (2011): 460–468, 10.1097/SGA.0b013e318237d201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elwenspoek M., Banks J., Desale P. P., Watson J., and Whiting P., “Exploring Factors Influencing Quality of Life Variability Among Individuals With Coeliac Disease: An Online Survey,” BMJ Open Gastroenterology 11, no. 1 (2024): e001395, 10.1136/bmjgast-2024-001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wolf R. L., Lebwohl B., Lee A. R., et al., “Hypervigilance to a Gluten‐Free Diet and Decreased Quality of Life in Teenagers and Adults With Celiac Disease,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 63, no. 6 (2018): 1438–1448, 10.1007/s10620-018-4936-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reilly N. R., “The Gluten‐Free Diet: Recognizing Fact, Fiction, and Fad,” The Journal of Pediatrics 175 (2016): 206–210, 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rose C., Law G. U., and Howard R. A., “The Psychosocial Experiences of Adults Diagnosed With Coeliac Disease: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis,” Quality of Life Research 33, no. 1 (2024): 1–16, 10.1007/s11136-023-03483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.