ABSTRACT

Coffee has long been popular worldwide. The rise in lifestyle-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, dementia, and others has motivated coffee usage and illness prevalence studies. Some studies show coffee consumers are at risk for such diseases, whereas others show its active components protect them. Policymakers and the public need a comprehensive umbrella review to make healthy choices and enjoy coffee. Coffee consumption and stroke, CHD, and dementia outcomes have been distinguished using the PICO search strategy in PubMed with a filter for meta-analysis. We included 10 years of investigations until October 2023. MeSH terms “coffee intake,” “stroke, dementia,” and “transient ischemic attack,” comparing stroke risk with coffee consumption were used. The study excluded case reports and non-human, non-English observational research. The stroke risk of coffee was examined using RevMan software. Coffee consumption’s stroke risk ratio (RR), 95% CI, and I2 were estimated. Forest plots with P values ≤ 0.05 are significant. The umbrella review includes 11 meta-analyses from 457052 papers, totalling 11.96 million individuals. Drinking up to 4 cups of coffee daily reduced stroke risk by 12% compared with not drinking any coffee (0.88 (CI of 0.84-0.92, I2 of 13%, P < 0.00001)). Coffee drinkers had a 1.19 risk ratio for cardiovascular diseases compared to non-coffee drinkers (CI: 0.99–1.38, I2 = 84%, P < 0.00001). The dementia risk ratio for caffeine users was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.82-0.97, I2 = 46%, P < 0.00001) compared with non-consumers. Our analysis covering 5.42 million individuals found that 4 cups of coffee consumed a day reduced stroke risk by 12%. Coffee may reduce ischemic and haemorrhagic strokes by preserving endothelium and antioxidants. Coffee may lessen dementia risk, according to our study’s 0.94 pooled risk ratio after sensitivity analysis. Heavy coffee drinkers had a greater CHD risk, as per our findings. Heavy coffee drinkers were more at risk.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular stroke, coffee consumption, dementia, stroke

Why was this Study Done

Why was this study performed? The continued prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and neurodegenerative illnesses continues to be a considerable burden on both morbidity and mortality worldwide. Stroke, coronary heart disease (also known as CHD), and dementia are three of the most prevalent diseases that contribute to the overall burden of disease in the world. Due to the close pathological sharing of these three diseases, they have been studied for a long time. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the possible impact that coffee drinking may have on these illnesses, as it has become popular worldwide. The findings of studies examining the connection between drinking coffee and CVDs such as stroke and heart disease, as well as the link between coffee and dementia, have been inconsistent and occasionally contradictory.

What did the researchers do, and what did they find? Our study included a total of 11 meta-analyses, comprising more than 9 million people all over the world. It included prospective studies on coffee consumption and the risk of acquiring stroke, CVD, and dementia. Our study showed that compared with no coffee consumption, people who drink coffee have about 12 per cent less chance of getting stroke, 6% less risk of getting dementia, but a slight increased risk of CVD (5–19%).

How do we infer the findings? These findings explain a possible beneficial effect of coffee on the prevention of stroke and dementia but not on CHD. Based on our umbrella meta-analysis, we suggest adding some statutory warnings in collaboration with nutrition guidelines about the increased risk of CHD associated with excessive coffee consumption. We recommend further prospective studies targeting specifically looking for coffee while matching patients with other risk factors to further confirm this.

Manuscript relevant to the journal –as a leading journal catering to the needs of primary physician, family physician and public health we believe this manuscript holds relevance to both the coffee consumers in all walks of life and for doctors who can guide the common folks about how much coffee can they consume for staying healthy.

Introduction

The continued prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and neurodegenerative illnesses continues to be a considerable burden on both morbidity and mortality worldwide. These conditions continue to pose serious problems for global health. Stroke, coronary heart disease (also known as CHD), and dementia are three of the most prevalent diseases that contribute to the overall burden of disease in the world. In contrast, coronary heart disease (CHD), which is characterized by the obstruction of coronary arteries, can lead to myocardial infarctions. Strokes, which are characterized by decreased blood supply to the brain, lead to a spectrum of neurological impairments. Dementia, a catchall term for cognitive decline, memory loss, and decreased day-to-day functioning, makes the healthcare issue much worse. The burden of these conditions is quantified in Disability-Adjusted Life Years, also known as DALYs. DALYs represent the number of years of a healthy life that are lost owing to illness, disability, or death at an earlier age. The Global Burden of Disease Study found that cardiovascular diseases and dementia were among the major causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) throughout the globe in the year 2020. This highlights the critical need for thorough research into the prevention and management of these conditions (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators.[1] Link Between Coffee Drinking and Diseases: In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the possible impact that coffee drinking may have on these illnesses. The global popularity of coffee as a beverage is well-known, and caffeine, its primary component, is found not only in coffee but also in tea, soda, energy drinks, chocolate, and even medicines, among other sources.[2,3] Global coffee production in 2020/2021 reached 175.35 million 60-kilogram bags, whereas the United States consumed nearly 26 million 60-kilogram bags during the same period, with Americans drinking an average of 1.87 cups of coffee per day. Leaders in coffee consumption were from Northern Europe countries such as Finland and Norway. Overall consumption of coffee was lowest in Asia compared with the US and Europe.[4] A coffee cup’s characteristics are determined by the type of bean, roast, grind, and brewing method.[5] This interest has been spurred on by the link between coffee consumption and diseases. Caffeine, chlorogenic acids, and antioxidants are just some of the bioactive chemicals that may be found in coffee, which is one of the beverages that is consumed on a global scale more than any other. The findings of studies examining the connection between drinking coffee and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as stroke and heart disease, as well as the link between coffee and dementia, have been inconsistent and occasionally contradictory. Although some research points to the possibility of protective effects of coffee consumption against these diseases because of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics of coffee, other studies point to the possibility of coffee’s raising blood pressure and cholesterol levels as a cause for concern.[6] In their study, they found protective effects in cases of coffee consumption and dementia before and after stroke. Matsushita et al.,[7] in their study too, found similar results. They concluded that drinking more than 3 cups of coffee per day could effectively reduce the risk of dementia by 50%. The recently shared results from the Hunt study, however, do not support the findings and instead tell us it’s the type of coffee that decides whether dementia will set in or not. As a consequence of this, the investigation into the nature of the link between coffee drinking and the aforementioned conditions is one that is fraught with both intrigue and difficulty.[8] Because of the close pathology sharing of the three diseases, i.e., stroke, chronic heart disease, and dementia, they have been studied for quite some time. And we chose these three diseases for their close pathology, linkages, and problem burden.[9]

Rationale for an Umbrella Review: An umbrella review is a convincing method to synthesize and critically evaluate the existing data because there is a large body of literature on the association between coffee intake and stroke, coronary heart disease, and dementia. This body of literature includes separate meta-analyses and systematic reviews. An umbrella review is a methodical and open-ended means of evaluating the consistency, volume, and quality of previously conducted meta-analyses. As a result, it provides a more in-depth comprehension of the present state of knowledge. An umbrella review is a type of research that takes the findings of several meta-analyses and combines them into a single body of information to help uncover trends, sources of heterogeneity, and potential causes of bias across studies. This strategy can also be helpful in identifying research gaps and topics that require more exploration, which is an important aspect of the research process.[10]

The Novelty of the Study and Its Aims: This umbrella review is unusual since it provides a thorough synthesis of the information that has previously been gathered regarding the connection between drinking coffee and the risk of having a stroke, coronary heart disease, or dementia. This work intends to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced explanation of these connections by carefully examining the findings from multiple meta-analyses. These findings were collected from a variety of sources. The following is a list of the particular goals that this study aims to accomplish: The purpose of this study is to do a comprehensive evaluation of the available meta-analyses that investigate the link between coffee consumption and stroke, as well as critically evaluate their quality and methodology. To assess the consistency and degree of connections between coffee intake and CHD across several meta-analyses, it is necessary to examine these associations. To determine whether or not there is a link between drinking coffee and the risk of developing dementia, taking into account the many different types of research designs and population variables that exist.

Methods

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the occurrence of various morbid conditions such as stroke, coronary heart disease, and dementia in coffee drinkers when compared with non-drinkers. Our secondary endpoints were a type of stroke and a type of coffee drinker.

Definitions

Study-Study-specific details are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the included studies with various defining components

| Characteristics of the studies involved in this meta-analysis | Study name; Year | Study design | Study period | Studies in meta -analysis | Total sample size | [Comparison] Coffee consumption (+) vs No coffee consumption (-) | Outcomes [Effect measures] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee consumption and (STROKE) As per GradePRO Certainty of evidence Moderate Coffee consumption and CHDs/MI As per GradePRO Certainty of evidence Moderate | Larsson and Orsini 2011[11] | Meta analysis of prospective Cohort Studies | 1966-2011 | 11 | 479689 | 37674/407345 | Coffee consumption as the number of cups and stroke. Subgroup geographical country and continent, men and women, type of stroke as ischemia and haemorrhagic |

| Kim B et al. 2012[12] | Meta Analysis of prospective Cohort Studies | 2001-2011 | 9 | 206437 | Coffee consumption more than or equal to 4 cups a day and stroke risk. Subgroup geographical location, gender of study ( Women ), Total stroke, ischaemic stroke | ||

| Shao C et al. 2021[13] | Meta analysis of prospective cohort studies | 1998-2019 | 21 | 2488086 | 809614/259068 | Coffee consumption and relative RR. Subgroups gender wise risk Men, Women Type of coffee caffeinated decaffeinated ischemic stroke hemorrhagic stroke subarachnoid hemorrhage Continent/Country USA, Japan, European | |

| Chan L et al. 2021[14] | Meta analysis of prospective cohort studies | 1990-2020 | 7 | 2460031 | 216614/80086 | Coffee consumption summarized Hazard Ratio. Subgroup Women only, hemorrhagic, ischemic, | |

| Sofi F et al., 2007[15] | meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies | 1966 to 2006 | 13 case control and 10 cohort studies | 403631 | 49137/263213 | Coffee consumption as number of cups per day and CHDs. Stratification by region Europe, United States, stratification by year of publication <1995 >1995, stratification by outcome measure non-fatal events fatal events, stratification by years of follow up <15 yrs. >15 yrs. | |

| Wu JN et al. 2009[16] | meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | 1966 to 2008 | 21 | 407806 | 25603/290092 | Coffee consumption light, moderate, heavy, very heavy subgroups region United states, Europe, gender male female, CHDs outcomes total CHD fatal CHD non-fatal CHDs, Follow up years <10 years >10 years, confounder adjustments before after, study quality-quality score >median <median | |

| Mo L, et al., 2018[17] | Meta-analysis | 1970 to 2017) | 17 studies | 233617 | 33781/397238 | Coffee consumption with number of cups and relative risk of myocardial infarction. Sex male female, coffee type caffeinated decaffeinated all types, study location Europe, United states, study design cohort and case control, NOS score | |

| Park Y, et al., 2023[18] | Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | on December 21, 2021. | 32 prospective cohort study | 2234952 | 329065/1803162 | Coffee consumption and relative risk CHD. Sex male female, region Europe, North America, Asia, follow up years <10 10-20 >20 years, amount of coffee consumption low, moderate, and high type of CHD outcome incidence mortality, type of coffee caffeinated decaffeinated, methodology quality high and low. | |

| Coffee consumption and dementia As per GradePRO Certainty of evidence Low | Santos C et al. 2010[19] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 1989-2009 | 11 | 407806 | 25603/290092 | Coffee consumption light, moderate, heavy, and very heavy subgroups region United states and Europe, gender male female, CHDs outcomes total CHD fatal CHD non-fatal CHDs, follow up years <10 years >10 years, confounder adjustments before after, study quality-quality score >median <median |

| Liu QP et al. 2016[20] | Systemic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | 1966-2014 | 32 prospective cohort study | 2234952 | 329065/1803162 | Coffee consumption and relative risk CHD. Sex male female, region Europe, North America, and Asia, follow up years <10 10-20 >20 years, amount of coffee consumption low, moderate and high, type of CHD outcome incidence mortality, type of coffee caffeinated decaffeinated, methodology quality high and low. | |

| Larsson SC and Orsini 2018[21] | Meta-analysis of prospective studies | 1966-2018 | 403631 | 49137/263213 | Coffee consumption as number of cups per day and CHDs. Stratification by region Europe and United States, stratification by year of publication <1995 >1995, stratification by outcome measure non-fatal events fatal events, stratification by years of follow up <15 years. >15 years. |

Search strategy and selection criteria: We performed an umbrella meta-analysis on previously published meta-analyses (studies) using PRISMA guidelines from January 1, 2016, to August 31, 2023. We used PubMed to find out a meta-analysis comparing coffee consumption vs no coffee consumption and its effect on health in terms of the occurrence of stroke, CHDs, and dementia. We used keywords: caffeine intake, coffee intake, caffeine use, coffee use, coffee consumption, or caffeine consumption. Stroke or cerebrovascular events or neurogenic stroke or ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack or hemorrhagic stroke for finding stroke association and coffee. For CHDs, we used coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, ischaemic heart disease, cardiovascular heart diseases, cardiac arrest, or heart attack. For dementia, we used Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive decline, dementia, memory loss, or cognitive impairment. All search results were then merged using the term AND to get our final list of studies. These were then individually sorted following the PRISMA protocol, as mentioned.[22]

Study selection

All studies were identified using the search strategy described above and screened independently by RP, HG, NN, SK, LK, VS, and NP for their eligibility, and any disagreement was resolved through discussion with RKR and UP. Studies describing a meta-analysis of observational cohort studies were considered for full-text evaluation.

Inclusion criterion

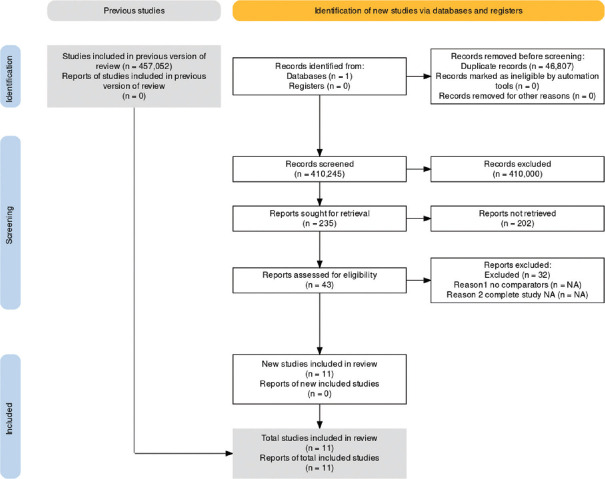

Any literature other than meta-analyses such as case reports, review articles, and observational studies were excluded. Non-English literature, non-full text, and non-human studies were excluded. Flow diagram of the study selection process is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA table detailing the selection and inclusion of various studies in the analysis Source- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction form on an Excel sheet was used to extract data from the included studies for the assessment of literature synthesis. The data extraction form was designed in consultation with the biostatistician and methodologist on the team (NP and SK). Extracted information included: study setting (study name, year of publication), study design, study population demographics (mean/median age and sex%), sample size, coffee consumption, type of coffee consumption in terms of number of cups, primary outcomes such as overall relative risk ratio, and other associated secondary outcomes such as type of stroke, occurrence of dementia, and information for assessment of the risk of bias. Two review authors (RKR and HG) extracted the data independently, and the differences identified were resolved through discussion with reviewers (RKR and UP).

Statistical analysis

We performed analysis using Review Manager 5.3 software (Rev Man, The Cochrane Collaboration). Hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were mainly used for data analysis. A pooled relative risk ratio >1 in those who consumed coffee implied a causation. The Mantel-Haenszel formula was used to calculate dichotomous variables to obtain ORs along with their 95% CIs to describe the outcome comparison between the occurrence of stroke, CHDs, and dementia in coffee drinkers vs non-drinkers. Inverse variance was used regardless of heterogeneity to estimate the combined effect and its precision, to give a more conservative estimate of the ORs and 95% CI. To evaluate heterogeneity, we used I2 statistics, and >70% was considered significant heterogeneity. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots [Online Supplemental File 1 (114KB, tif) ], and individual and overall study bias were described using the RoBANS integrated in RevMan shown in Forrest plots.[23] The cumulative evidence was assessed for the reliability using the GRADE PRO tool [Online Supplemental File 2].[24] The pooled OR and 95% CI are represented in the form of Forrest plots. Between-study heterogeneity (I-square), evidence of small-study effects, and excess significance were assessed.

Results of literature screening and study selection

A PubMed database search generated a total of 457052 articles. Before screening, 46807 ineligible articles were removed resulting in 410245 records. Using filters and after removing 410000 were excluded owing to non-conformity to our objectives of search. Out of 245 reports sought for retrieval of which 202 were not retrieved. The remaining 43 studies were assessed for eligibility. 32 were excluded for not being meta-analysis and two were excluded for not assessing prognosis. Finally, 11 meta-analyses were included for umbrella review with a total of 9.85 million sample size. The screening procedure in the study selection process is shown in the flowchart below as depicted in Figure 1.

Results

We chose total 11 studies which were meta-analysis spanning across the globe included more than 42 million individuals who were consuming coffee and the outcomes in terms of the selected ailments [Table 1].

Coffee and stroke

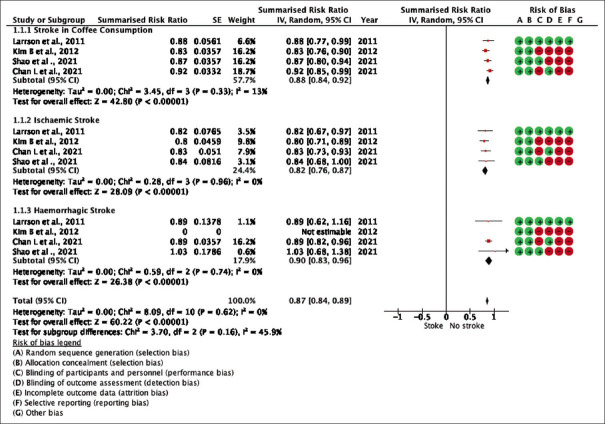

Coffee and stroke we performed our umbrella meta-analysis showed the beneficial effect of drinking coffee against the risk of getting stroke. Collectively, the analysis included about 44357 stroke cases out of a large sample size of 5427806. A comparison was made between no coffee consumption and at least some coffee consumption, which showed about 12 per cent less risk of stroke in people who drink up to 4 cups of coffee daily [0.88 (CI of 0.84-0.92, I2 of 13%, P < 0.00001)]. In terms of subgroup analysis, the RR of ischemic stroke was 0.82 (CI 0.76-0.87, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001), and haemorrhagic stroke was 0.90 (CI 0.83-0.96, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Results for coffee consumption and stroke in the form of Forrest plot

Coffee and CHDs

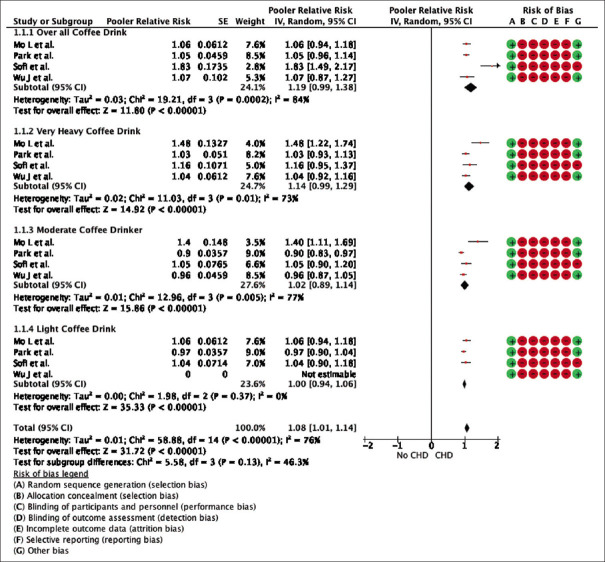

We performed the umbrella review on selected four studies, including 3.28 million participants, to compare the effect of coffee consumption and the relationship of CHDs. As the included meta-analysis clubbed coffee consumption and outcomes in terms of consumption of coffee as very heavy, moderate, and light drinkers, compared with non-coffee drinkers, people drinking coffee had a summarized risk ratio of 1.19 (CI of 0.99–1.38, I2 = 84%, P < 0.00001). Leaving one study out for sensitivity analysis to decrease the heterogeneity, the summarized RR obtained was 1.06 (CI of 0.99–1.12, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001). In terms of subgroup analysis, after leaving one study out, as it did not have data related to consumption of coffee in terms of very heavy or no coffee, the pooled relative risk for very heavy coffee drinkers was 1.05 (CI 0.98–1.12, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001), Moderate Coffee Drinkers was 0.95 (CI 0.88–1.02, I2 = 43%, P < 0.00001), and Light Coffee Drinkers was 1.00 (CI 0.94–1.06, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Forrest plot for coffee consumption and CHDs

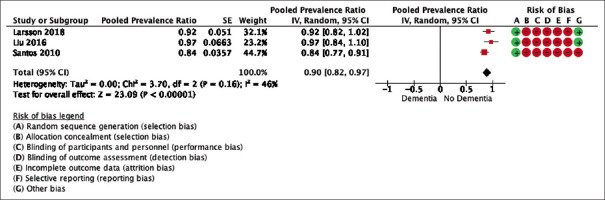

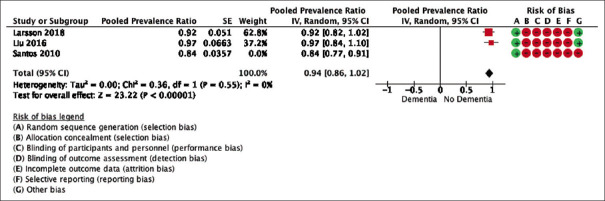

Coffee and dementia

An umbrella review on selected three studies was performed, including 377,663 participants to compare the effects of caffeine consumption in relation to Dementia. When compared with non-consumers, people with caffeine intake had a summarized risk ratio of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.82-0.97, I2 = 46%, P < 0.00001). We performed a sensitivity analysis, and one study was excluded to decrease the heterogeneity. The summarized relative risk obtained was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.86-1.02, I2 = 0%, P < 0.00001). Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Forrest plot for coffee consumption and dementia

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis Forrest plot for coffee consumption and dementia (Leave one study out)

Discussion

We did an umbrella meta-analysis looking into the effect of coffee consumption on stroke risk, the risk of CHDs, and dementia. Our analysis involved clinical studies and the populations of the US, Europe, and Asia. Our umbrella meta-analysis’s main strength was its number of participants, which comprised more than 5 million people all over the world. All prospective studies gave us a better perspective on understanding the overall risk of various diseases and their occurrences among coffee consumers. In our understanding, this is a unique analysis, clubbing all the existing meta-analyses available and using statistics to validate them.

Coffee and stroke

We established a protective effect regarding stroke occurrence in coffee drinkers. This was in line with other available meta-analyses that were reviewed. All these included prospective studies and the overall occurrence of stroke without subclassifications as haemorrhagic or infarct.[12,13,21] The exploration of possible reasons behind the protective effects of coffee and hypertension, ischemia, and other related pathological reasons has been explored. One of the postulated mechanisms for this has been the effect of an inverse relationship with endothelial dysfunction.[9,25,26] Yamagata et al.[27] in their comprehensive review, they advocate the role of coffee consumption over a prolonged period in maintaining normal endothelium function. One of the most plausible explanations given behind the effect is the presence of chlorogenic acids and other hydroxyhydroquinone metabolites, which act as antioxidants. Several bioactive constituents found in coffee have been suggested to play a role in the beneficial metabolic effects associated with its consumption. These constituents include caffeine, phenolics such as chlorogenic acid (CGA), lignans, trigonelline, and N-methylpyridinium; minerals and vitamins such as magnesium, potassium, and niacin; proteins; and lipids, particularly diterpenes such as cafestol and kahweol.[28] Although the evidence regarding the effect of chlorogenic acids from coffee consumption is not definitive, it has been demonstrated to have antioxidant effects. The fact that it has been documented that chlorogenic acid exhibits neuroprotective effects against excitotoxic insults holds significance because of the recognized involvement of glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity in various neurodegenerative disorders, notably Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, ischemic stroke, and epilepsy.[29,30] Indeed, coffee has been noted to be protective for type 2 diabetes mellitus, as found by Carlström and Larsson[31] in their exhaustive meta-analysis.

Coffee and CHDs

Coffee and CHDs in this umbrella review of 3.28 million participants, we observed that the high consumption of coffee was associated with an increased risk for CHDs as compared to non-coffee drinkers. (OR) Also in our study, on the basis of subgroup analysis on different coffee consumption levels, very heavy coffee drinkers showed an increased risk of CHDs as compared to moderate and light coffee drinkers. The results obtained align with the conclusions published in a case-control study conducted in Italy.[32] Although in prospective observational study where men who drank coffee at a rate of >28 cups/week had a 36% higher risk of CVD mortality.[33] Moreover, these findings are also consistent with the results of other studies that have demonstrated an increased risk of coronary heart diseases (CHDs) associated with heavy coffee consumption.[34,35] In addition, moderate and light coffee drinkers did not show a significant increase in the risk of CHD, suggesting no significant association, which aligns with conclusions in a review article.[36]

The Panagiotakos DB et al.[37] study demonstrated a J-shaped association between coffee consumption and the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes. In particular, very heavy consumption (>300 mL of coffee per day) was associated with a significant increase in the risk of CHDs. Several proposed biological mechanisms might explain the mechanisms that may be contributing to an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) associated with coffee consumption, such as the elevation of blood pressure, suggested with an increase of approximately 2.4 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure and a 1.2 mm Hg increase in diastolic blood pressure,[38] and raise in the plasma total homocysteine concentrations,[39] and also an increase in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels, as evidenced by the first-ever BIOBANK trials on the genetic structure of humans.[40]

It has been observed that an elevated risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) or acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was primarily evident among individuals with specific genotypes associated with slow caffeine metabolism, such as CYP1A21F instead of CYP1A21A, as reported by Cornelis et al.[41] (2006), or those with genotypes linked to low COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase gene) activity indicative of reduced catecholamine metabolism as per Happonen et al. (2006)[42] whereas other studies have shown that coffee, driven by caffeine and chlorogenic acid, can raise homocysteine levels, contributing to inflammation and arterial stiffness, potentially worsening atherosclerosis. Heavy coffee intake, especially in hypertensive individuals, is linked to increased inflammatory markers and impaired thrombosis/fibrinolysis, potentially harming vascular health.[43]

Happonen et al.[44] also found in their study that there is an independent, U-shaped dose-response relationship between the consumption of caffeine-containing coffee and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction or coronary death over a 5-year follow-up period. Interestingly, even when observing individuals over a more extended mean follow-up of 14 years, they observed that the incidence of acute coronary events remained higher among heavy coffee drinkers when compared with moderate coffee drinkers.

Coffee consumption and dementia

Coffee consumption and dementia: we used pooled data from three meta-analyses involving 377,663 participants in our umbrella review. (OR) From our study, it was evident that coffee consumption is associated with a decreased risk of dementia when compared with people who do not consume coffee. The results are similar to other exhaustive reviews performed on Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, based on the data obtained from two case-control and two cohort studies.[45,46] Another meta-analysis conducted by Wei Xu et al.[46] in China, based on 323 prospective cohort and case-control studies evaluating various modifiable risk factors, also supports an inverse relation between the two. They mention the role of coffee in short-acting terms and its long-term action if consumed over a long period. Short-term effect for stimulating the nervous system, whereas its long-term usage has been revalidated by them in preventing the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease, which is one of the major causes of dementia. Studies have explored and even validated improved cognitive performance in diseased populations such as those with chronic kidney diseases.[47] Prospective studies have explored the association between coffee and dietary habits for assessing cognitive functioning as well.[48]

But the long-term effect on memory and other neurocognitive functions which requires complex judgments and execution of higher-order skills have always been a debatable topic.[49]

The proposed pathological mechanism to corroborate these findings has been suggested following various experiments on mice. Arendash et. al., in their successive experiments, have been able to prove the effect of caffeine both as a preventer and as capable of inducing a reversal on the brain Amyloid β levels.[50,51] These brain amyloid β levels have been attributed to the main precursor for the development of dementia in humans by disrupting the adenosine A2a receptors in varied ways, as explained by Dall’Igna et al.[52] In their experiments on cerebellar cell cultures, chronic and sub-chronic coffee treatment significantly protected against Aβ peptide toxicity. Based on these, they proposed how caffeine and antagonists to adenosine A2a receptors prevent cognitive decline in mice. Ullah et al.[53] further provided evidence of caffeine therapy leading to significantly reduced d-galactose-induced neuroinflammation by inhibiting COX-2, NOS-2, TNF, and IL-1.

Evidence related to the neuroprotective provided by coffee has also been suggested from the neuroprotective effect induced by chlorogenic acid owing to its antioxidant-rich activity. Studies have demonstrated the effect of chlorogenic acid and how it works. Putting chlorogenic acid on PC12 cells stopped the cell death caused by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) very well. The observed protective effect can be attributed to the reduction in intracellular build-up of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the suppression of activation of the JNK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Through two mechanisms, the research by Kim et al. showed that chlorogenic acid effectively reduced apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. Firstly, it inhibited the downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL induced by H2O2. Secondly, it prevented the H2O2-induced cleavage of caspase-3 and pro-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (pro-PARP), which are known to promote apoptosis. Another thing it did was increase the production of an antioxidant enzyme called NAD (P) H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO-1). This study also provided evidence that the neuroprotective benefits of both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee were comparable. This finding implies that substances other than caffeine, such as chlorogenic acids, might play a role in the neuroprotective qualities of coffee.[54,55] Other studies have also demonstrated the protection chlorogenic acid provides from brain β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity.[56] The exact mechanism detailing how coffee works as a neuroprotective agents is still not very clearly understood.

Strengths of the study

The large number of studies included makes our study more robust and brings out recent, definitive evidence.

Limitations of the study

Only accessing one database is a major limitation, whereas other limitations were that there was no differentiation between the types of coffee consumed; no quantification of coffee in a cup being consumed, not considering variability because of type of brewing, we have not checked whether the coffee was consumed with milk, sugar, or anything else; and the results were of a dichotomous nature.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study, involving a substantial sample size of more than 5.42 million people, showed a significant risk reduction of 12% of stroke among individuals consuming up to 4 cups of coffee daily, highlighting the protective benefits of coffee consumption against stroke. The risk reduction was seen in both ischemic and haemorrhagic strokes, possibly attributing to the role of coffee in maintaining endothelial function and its antioxidant properties. Our study also suggests that coffee consumption may be associated with a reduced risk of dementia, with a summarized risk ratio after sensitivity analysis of 0.94. This finding may be attributed to the possible neuroprotective mechanisms of caffeine and chlorogenic acids. Conversely, our analysis indicated an increased risk of coronary heart diseases (CHDs) among heavy coffee drinkers. This risk was particularly pronounced in very heavy coffee drinkers and is in line with previous research, increasing the importance of considering coffee intake when assessing CHD risk. Blood pressure increases, changes in homocysteine levels, and changes in lipid profiles are just a few biological factors that may have an impact on this association between coffee consumption and CHDs. Based on our umbrella meta-analysis, we suggest adding some statutory warnings in collaboration with nutrition guidelines about excessive coffee consumption, which can increase the risk of CHDs.

Ethical approval

Although this article does not contain any studies with the direct involvement of human participants or animals performed by any of the authors, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The data used in this study is deidentified from PubMed, so informed consent or IRB approval was not needed for this study.

Availability of data and material

The data is collected from the studies published online and is publicly available, and specific details related to the data and/or analysis will be made available upon request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: UP, RKR, HG

Methodology: SJ, VS, NN

Acquisition of data: SMJ, TK, SK

Software: HG, RBP, NP

Formal analysis and investigation: AN, LV, CS

Resources: UP, RKR, LV, CS

Validation: SJ, VS, NN, LV

Data Curation: SMJ, TK, SK

Writing: original draft preparation: RKR, UP, HG

Writing: review, critical feedback, and editing: UP, RKR

Visualization: RKR, UP, NN, LV

Project administration: RKR, UP, NN

Supervision: UP, RKR

Funding acquisition: None; All authors went through the manuscript before submission.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Online Supplemental File 2

| Coffee Consumers compared to Non consumers for health problems Stroke , Cardiovascular heart diseases and Dementia. Bibliography: . Coffee Consumption and Stroke Umbrella. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Certainty assessment | Summary of findings | ||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Participants (studies) Follow-up | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty of evidence | Study event rates (%) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | ||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| With placebo | With Stroke in Coffee Consumers | Risk with placebo | Risk difference with Stroke in Coffee Consumers | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Coffee Consumption and Stroke (assessed with: Summarised Risk Ratio) | |||||||||||

| 1068682 (4 non-randomised studies) | serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect dose response gradient | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate | 0/259068 (0.0%) | 0/809614 (0.0%) | Summarised Risk Ratio 0.88 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0 per 1,000 | -- per 1,000 (from -- to --) |

CI: confidence interval

| Coffee Consumption and Cardiovascular heart diseases (assessed with: Summarised Risk Ratio) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27791291 (4 non-randomised studies) | serious | not serious | serious | not serious | strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect dose response gradient | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate | 0/27353705 (0.0%) | 0/437586 (1.7%) | Summarised Risk Ratio 1.19 (0.99 to 1.38) | Low | |

| 100 per 1,000 | -- per 1,000 (from -??to???)- to -?)-) | ||||||||||

| Moderate | |||||||||||

| 300 per 1,000 | -- per 1,000 (from -??to???)- to -?)-) | ||||||||||

| Coffee Consumption and Dementia (assessed with: Summarised Risk Ratio) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 437586 (3 non-randomised studies) | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | publication bias strongly suspected all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect dose response gradienta | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | /437586 (0) | Pooled Prevalence Ratio 0.90 (0.82 to 0.97) | 0 per 1,000 | -- per 1,000 (from -- to --) |

CI: confidence interval. aRisk of Bias ascertained as high

References

- 1.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iriondo-DeHond A, Uranga JA, del Castillo MD, Abalo R. Effects of coffee and its components on the gastrointestinal tract and the brain–gut axis. Nutrients. 2020;13:88. doi: 10.3390/nu13010088. doi:10.3390/nu13010088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abalo R. Coffee and caffeine consumption for human health. Nutrients. 2021;13:2918. doi: 10.3390/nu13092918. doi:10.3390/nu13092918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.statista.com. Worldwide-production-of-coffee. 2023. [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 03]. Available from:https://www.statista.com/statistics/263311/worldwide-production-of-coffee/?kw=&crmtag=adwords&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu-KiBhCsARIsAPztUF183tIsReufj19aEprJsyWIIdd_aYopwOGXjTT3DQ2cDSk_6RjZ4tAaAqgzEALw_wcB .

- 5.harvard.com. [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 03]. Available from:https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/food-features/coffee .

- 6.Zhang Y, Yang H, Li S, Li WD, Wang Y. Consumption of coffee and tea and risk of developing stroke, dementia, and poststroke dementia: A cohort study in the UK Biobank. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003830. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed. 1003830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita N, Nakanishi Y, Watanabe Y, Kitamura K, Kabasawa K, Takahashi A, et al. Association of coffee, green tea, and caffeine with the risk of dementia in older Japanese people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:3529–44. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbel D, Åsvold BO, Kolberg M, Selbæk G, Noordam R, Skjellegrind HK. The association between coffee and tea consumption at midlife and risk of dementia later in life: The HUNT study. Nutrients. 2023;15:2469. doi: 10.3390/nu15112469. doi:10.3390/nu15112469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Satija A, van Dam RM, Hu FB. Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2014;129:643–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H. Use, application, and interpretation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2021;74:369–70. doi: 10.4097/kja.21374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson SC, Orsini N. Coffee consumption and risk of stroke: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:993–1001. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim B, Nam Y, Kim J, Choi H, Won C. Coffee consumption and stroke risk: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33:356–65. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.6.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao C, Tang H, Wang X, He J. Coffee consumption and stroke risk: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 2.4 million men and women. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. 2021;30:105452. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105452. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan L, Hong C-T, Bai C-H. Coffee consumption and the risk of cerebrovascular disease: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Neurol. 2021;21:380. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02411-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofi F, Conti AA, Gori AM, Eliana Luisi ML, Casini A, Abbate R, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17:209–23. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Ho SC, Zhou C, Ling WH, Chen WQ, Wang CL, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of coronary heart diseases: A meta-analysis of 21 prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2009;137:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mo L, Xie W, Pu X, Ouyang D. Coffee consumption and risk of myocardial infarction: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget. 2018;9:21530–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park Y, Cho H, Myung S-K. Effect of coffee consumption on risk of coronary heart disease in a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Cardiol. 2023;186:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A, Lunet N. Caffeine intake and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:S187–204. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu QP, Wu YF, Cheng HY, Xia T, Ding H, Wang H, et al. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of cognitive decline/dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrition. 2016;32:628–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson S, Orsini N. Coffee consumption and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutrients. 2018;10:1501. doi: 10.3390/nu10101501. doi:10.3390/nu10101501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;72:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Lee Y, Seo H, Jang B, Son H, Kim S, et al. Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS) Abstracts of the 19th Cochrane Colloquium. 2011. [Last accessed 2024 Feb 18]. https://abstracts.cochrane.org/2011-madrid/risk-bias-assessment-tool-non-randomized-studies-robans-development-and-validation-new.

- 24.McMaster University and Evidence Prime. GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software] 2024. [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 18]. Available from:https://www.gradepro.org/terms/cite .

- 25.Natella F, Nardini M, Belelli F, Scaccini C. Coffee drinking induces incorporation of phenolic acids into LDL and increases the resistance of LDL to ex vivo oxidation in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:604–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mubarak A, Bondonno CP, Liu AH, Considine MJ, Rich L, Mas E, et al. Acute effects of chlorogenic acid on nitric oxide status, endothelial function, and blood pressure in healthy volunteers: A randomized trial. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9130–6. doi: 10.1021/jf303440j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamagata K. Do coffee polyphenols have a preventive action on metabolic syndrome associated endothelial dysfunctions?An assessment of the current evidence. Antioxidants. 2018;7:26. doi: 10.3390/antiox7020026. doi:10.3390/antiox7020026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos RMM, Lima DRA. Coffee consumption, obesity and type 2 diabetes: A mini-review. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:1345–58. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajikawa M, Maruhashi T, Hidaka T, Nakano Y, Kurisu S, Matsumoto T, et al. Coffee with a high content of chlorogenic acids and low content of hydroxyhydroquinone improves postprandial endothelial dysfunction in patients with borderline and stage 1 hypertension. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:989–96. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewerenz J, Maher P. Chronic glutamate toxicity in neurodegenerative diseases—What is the evidence? Front Neurosci. 2015;9 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00469. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlström M, Larsson SC. Coffee consumption and reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2018;76:395–417. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuy014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavani A, Bertuzzi M, Negri E, Sorbara L, La Vecchia C. Alcohol, smoking, coffee and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:1131–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1021276932160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Sui X, Lavie CJ, Hebert JR, Earnest CP, Zhang J, et al. Association of coffee consumption with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1066–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenland S. A meta-analysis of coffee, myocardial infarction, and coronary death. Epidemiology. 1993;4:366–74. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammar N, Andersson T, Alfredsson L, Reuterwall C, Nilsson T, Hallqvist J, et al. Association of boiled and filtered coffee with incidence of first nonfatal myocardial infarction: The SHEEP and the VHEEP study. J Intern Med. 2003;253:653–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattioli AV. Effects of caffeine and coffee consumption on cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Future Cardiol. 2007;3:203–12. doi: 10.2217/14796678.3.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Kokkinos P, Toutouzas P, Stefanadis C, et al. The J-shaped effect of coffee consumption on the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes: The CARDIO2000 case-control study. J Nutr. 2003;133:3228–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urgert R, van Vliet T, Zock PL, Katan MB. Heavy coffee consumption and plasma homocysteine: A randomized controlled trial in healthy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1107–10. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jee SH, He J, Appel LJ, Whelton PK, Suh I, Klag MJ. Coffee consumption and serum lipids: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:353–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou A, Hyppönen E. Habitual coffee intake and plasma lipid profile: Evidence from UK Biobank. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:4404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A, Kabagambe EK, Campos H. Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;295:1135–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Happonen P, Voutilainen S, Tuomainen TP, Salonen JT. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism modifies the effect of coffee intake on incidence of acute coronary events. PLoS One. 2006;1:e117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000117. doi:10.1371/journal.pone. 0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim D, Chang J, Ahn J, Kim J. Conflicting effects of coffee consumption on cardiovascular diseases: Does coffee consumption aggravate pre-existing risk factors? Processes. 2020;8:438. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Happonen P, Voutilainen S, Salonen JT. Coffee drinking is dose-dependently related to the risk of acute coronary events in middle-aged men. J Nutr. 2004;134:2381–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quintana JLB, Allam MF, Del Castillo AS, Fernández-Crehuet Navajas R. Alzheimer's disease and coffee: A quantitative review. Neurol Res. 2007;29:91–5. doi: 10.1179/174313206X152546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu W, Tan L, Wang H-F, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1299–306. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia L, Zhao H, Hao L, Jia LH, Jia R, Zhang HL. Caffeine intake improves the cognitive performance of patients with chronic kidney disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:976244. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.976244. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.976244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paz-Graniel I, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Toledo E, Camacho-Barcia L, Corella D, et al. Association between coffee consumption and total dietary caffeine intake with cognitive functioning: Cross-sectional assessment in an elderly Mediterranean population. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:2381–96. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02415-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR. A review of caffeine's effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:294–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arendash GW, Schleif W, Rezai-Zadeh K, Jackson EK, Zacharia LC, Cracchiolo JR, et al. Caffeine protects Alzheimer's mice against cognitive impairment and reduces brain b-amyloid production. Neuroscience. 2006;142:941–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arendash GW, Mori T, Cao C, Mamcarz M, Runfeldt M, Dickson A, et al. Caffeine reverses cognitive impairment and decreases brain amyloid-b levels in aged Alzheimer's diseas Dall'Igna e mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:661–80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dall’Igna OP, Fett P, Gomes MW, Souza DO, Cunha RA, Lara DR. Caffeine and adenosine A2a receptor antagonists prevent b-amyloid (25–35)-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ullah F, Ali T, Ullah N, Kim MO. Caffeine prevents d-galactose-induced cognitive deficits, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the adult rat brain. Neurochem Int. 2015;90:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nabavi SF, Tejada S, Setzer WN, Gortzi O, Sureda A, Braidy N, et al. Chlorogenic acid and mental diseases: From chemistry to medicine. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15:471–9. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160325120625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J, Lee S, Shim J, Kim HW, Kim J, Jang YJ, et al. Caffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and the phenolic phytochemical chlorogenic acid up-regulate NQO1 expression and prevent H2O2-induced apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:466–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei M, Chen L, Liu J, Zhao J, Liu W, Feng F. Protective effects of a Chotosan Fraction and its active components on b-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is collected from the studies published online and is publicly available, and specific details related to the data and/or analysis will be made available upon request.