ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Klebsiella pneumoniae commonly causes healthcare-associated infections and shows multidrug resistance. K. pneumoniae can produce biofilm. Carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae is due to the production of carbapenemases mainly. This study was done to evaluate the formation of biofilm and carbapenemase resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates.

Material and Methods:

A total of 110 K. pneumoniae isolated from various clinical samples were taken, the antibiotic susceptibility test was done by the Kirby disk diffusion method, and biofilm detection was done by the tissue culture plate method. All the carbapenem-resistant isolates were confirmed by multiplex real-time PCR (mPCR). Those found positive for any of the carbapenemase genes were tested by the modified Hodge test (MHT), modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM), and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-modified carbapenem inactivation method (eCIM).

Results:

Out of 110 isolates, 66% (72/110) were carbapenem-resistant (suggestive of carbapenemase producers) by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion but 58% (42/72) of Klebsiella isolates were confirmed for carbapenemase production by mPCR. Maximum number of carbapenemase gene were New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) 52% (N = 22), 29% (N = 12) coproducers (NDM+OXA-48), and lowest in oxacillinase (OXA-48), 19% (N = 8). The overall sensitivity of MHT and mCIM+eCIM was 62% and 93%, and specificity was 88% and 97%, respectively. Our study showed that moderate biofilm producers were 51% (N = 56) K. pneumoniae isolates, strong biofilm producers 27% (N = 30), and 22% (N = 30) were weak/non-biofilm producers. We also found the correlation between biofilm formation and carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CR-KP) genes was statistically significant with a P value of 0.01*<0.05.

Conclusion:

Most isolates of K. pneumoniae demonstrated a wide range of antibiotic resistance and were biofilm producers. Our results indicated that the combination of mCIM with eCIM showed high sensitivity and specificity to detect CR-KP compared with MHT.

Keywords: CR-KP - carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, eCIM - ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-modified carbapenem inactivation method, MBLs-Metallo-β-Lactamase, mCIM - modified carbapenem inactivation method, mPCR - multiplex real-time PCR

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an encapsulated gram-negative bacillus belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family.[1] In 1875, Edwin Klebs was the first to find it. The bacterium K. pneumoniae is a prevalent cause of hospital-acquired infections. Through enzyme synthesis like ESBLs (“Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase”) and carbapenemase, K. pneumoniae develops antibiotic resistance more rapidly than most other bacteria.[2]

K. pneumoniae primarily colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract and oropharynx, from which it may easily enter the bloodstream and cause infections like bacteremia, surgical site infection, septicemia, UTI (“Urinary Tract Infection”), hospital-acquired pneumonia, and VAP (“Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia”).[3] According to recent WHO research, K. pneumoniae’s resistance to carbapenem antibiotics has spread to all regions of the world.[4]

About 11.8 percent of all hospital-acquired pneumonia in the world are mainly due to K. pneumonaie. About 8% to 12% of patients who are on a ventilator develop pneumonia, and 7% occur in non-ventilated patients. Mortality varies from 50% to 100% in patients with alcoholism and septicemia.[5]

In India, carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is now increasing.[6]

Greece has been reported to have the greatest rate of carbapenem resistance in the world, with a reported 68 percent resistance rate, followed by India and the eastern Mediterranean areas with a reported 54 percent resistance rate. China and the USA have low resistance rates (11%).[7]

Carbapenemases are generally categorized into two groups, MBLs (metallo-β-lactamases) and serine carbapenemases, whereas the molecular classification by Ambler divides carbapenemases into classes A, B, and D. MBLs comprise class B as they require metal-like zinc as a cofactor for their activity whereas serine carbapenemases are grouped into Class A and D because they have a serine moiety at their active sites.[8]

Several plasmids (KPC, IMP, NDM, VIM, OXA) and chromosomal genes (SME, SFC, IMI) encoding carbapenemase production have been identified but the plasmid genes, being transferable by horizontal gene transfer, are more significant and require additional consideration.[9]

Carbapenem resistance, without the production of carbapenemases, has also been reported and this could be achieved by reduced outer membrane permeability along with the over-expression of beta-lactamases (ESBL, AmpC). This kind of carbapenem resistance is thought to be less important because the resistance is not transferable.[8]

K. pneumoniae has a well-known ability to produce biofilms that are bacterial populations encased in an extracellular matrix. This matrix contains lipopeptides, DNA, and exopolysaccharides. Biofilm facilitates bacterial adhesion to all surfaces (living and non-living), protects against antibiotic penetration, and reduces its effects.[10]

Properly detecting CR-KP (“Carbapenem-Resistant K. Pneumoniae”) is essential for patient care to initiate correct epidemiological data, and also therapeutic options. Thus, the current research was done to assess the extent of drug resistance, its ability to produce biofilm, and to detect the genes responsible for carbapenemase production by genotypic (multiplex real-time PCR (mPCR)) and phenotypic (MHT, mCIM, and eCIM) tests.

Material and Methods

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study and was conducted in the Department of Microbiology at UPUMS, Saifai, Etawah over a period from November 2020 to June 2022. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institute Ethical Committee. (Letter no. 1910/UPUMS/Dean (M)/Ethical/2020-21 dated June 21, 2021).

Source of data

K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from cultures of various clinical samples in suspected cases of respiratory tract infections (sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, and endo-tracheal aspirates), urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections (blood, central line tips, umbilical catheter tips), skin and soft tissue infections (wound swabs, pus). These clinical samples were received at the microbiology department of UPUMS Saifai, Etawah for the routine bacteriological diagnosis. Samples of those patients having signs and symptoms of bacterial infections from RURAL MEDICAL INSTITUTE were included. Stool samples were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

Data collected was entered in a Microsoft Excel worksheet and statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 25 (Statistical package for social sciences). Chi-square test, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were used for the analysis and presentation of data.

Study methods

A total of 670 clinical samples were taken, out of which 110 K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from the patients of RURAL MEDICAL INSTITUTEs in the Department of Microbiology. The isolates were identified by using conventional biochemicals and VITEK 2® (Biomerieux: Marcy-IEtoile, France) compact system. Clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae (N = 110) were subjected to antibiotics susceptibility testing by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, making use of commercially available antibiotic disks (HiMedia, India), and were interpreted as per the standard CLSI, 2021 guidelines. The isolates found to be carbapenem (imipenem/meropenem/ertapenem) resistant were subjected to mPCR based on TaqMan probe technique (Hi-PCR® Carbapenemase Gene (Multiplex) PCR Kit, MB132, HIMEDIA, Mumbai). DNA extraction was done according to the manufacturer’s protocol by spin column solid phase extraction using silica membrane (HiPurA® Bacterial Genomic DNA Purification kit, MB505, HIMEDIA, Mumbai).

PCR reaction

Polymerase chain reactions were made in two tubes as per the manufacturer’s protocol by adding master mix, primer and probe mix, internal control, and DNA template along with positive and negative control, and a final reaction volume of 25 μl was prepared. The tube was centrifuged briefly at 6000 rpm for about 10 s and the tube was placed in a real-time PCR machine. Set the PCR program to interpret the data from the amplification plot. PCR program as per the manufacturer’s protocols is as follows: Initial denaturation was done at 95°C for 10 min, denaturation at 95°C for 05 s, annealing and extension were done at 60°C for 1 min, for 45 cycles, and results were interpreted. In this study, PCR has been taken as a gold standard test for the detection of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CR-KP) genes.

The CR-KP isolates were tested by the modified Hodge test (MHT) and modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) combined with ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-modified carbapenem inactivation method (eCIM). Isolates with both mCIM and eCIM tests positive were labeled as producing MBLSs and those with positive mCIM but negative eCIM tests were labeled as producing serine carbapenemases.

MHT test was performed according to a study done by Patidar N et al.[11]

Carbapenem inactivation methods of mCIM and eCIM: The procedure and interpretation of mCIM and eCIM as per CLSI guidelines 2018 are as follows.

About l μl loopful of test K. pneumoniae isolate was resuspended in two tubes containing 2 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB). One tube was devoid of EDTA (mCIM), while the other was supplemented with 20 μl EDTA (eCIM) of 5 mM. A meropenem (MEM) disk was submerged in each tube, and the tubes were incubated at 35°C for 4 h ± 15 min. The disks were then removed from the tubes and placed on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates upon which a carbapenem-susceptible reporter E. coli ATCC 25922 was applied. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 16 to 20 h and then the zone size was measured. The mCIM was considered negative if the zone size was >19 mm, positive if the zone size was 6 to 15 mm, or intermediate if pinpoint colonies were present within a 16 to 18 mm zone. An isolate was positive for MBL production when the eCIM zone size increases by >5 mm compared to the zone size observed for the mCIM and is taken negatively for MBLs if the increase in zone size is <4 mm.[12]

Biofilm assay

Biofilm assay was done by the tissue culture plate method as described by Christensen et al.[13] The interpretation of biofilm production was done according to the criteria of Stepanovic et al.[14]

Result

Out of 110 isolates, 66% (n = 72) were carbapenem-resistant by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion but 58% (42/72) of Klebsiella isolates were confirmed for carbapenemase production by mPCR. Of these, 22 (52%) were positive for the blaNDM gene, 8 (19%) were positive for the blaOXA48-like genes, and 12 (29%) were coproducers. The CR-KP was 65% (N = 27) in males and 35% (N = 15) in females. In the present study, we found that the maximum CR-KP of 36% (N = 15) was present in the age group >60 years old followed by the age group 50–59 years, 26% (N = 10). Sixty-seven percent (n = 28) of CR-KP were present in in-patient department (IPD) and intensive care unit (ICU) patients followed by out-patient department (OPD), 33% (n = 14).

Our study showed that the maximum CR-KP present in sputum was 29% (12/42) associated with 18% (4/22) New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), 25% (2/8) oxacillinase (OXA-48), and (6/12) 50% associated with coproducers gene. Minimum CR-KP was present in ascetic fluid 7% (2/42) of which 5% (1/22) was associated with NDM and 13% (1/12) was associated with the OXA-48 gene [Table 1]. Our study reported that the maximum risk factors were associated with diabetes at 33% and then chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at 29%.

Table 1.

Shows the distribution of carbapenemase resistance gene in various samples (N=42)

| Specimen | Number (n) | % | NDM (n) | % | OXA-48 (n) | % | NDM+OXA-48 (n) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum | 12 | 29 | 4 | 18 | 2 | 25 | 6 | 50 |

| E.T. aspirate | 3 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pus | 7 | 16 | 4 | 18 | 1 | 13 | 2 | 17 |

| Urine | 11 | 26 | 8 | 36 | 2 | 25 | 1 | 8 |

| CSF | 4 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 8 |

| Blood | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 2 | 17 |

| Ascitic fluid | 2 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 42 | 22 | 8 | 12 |

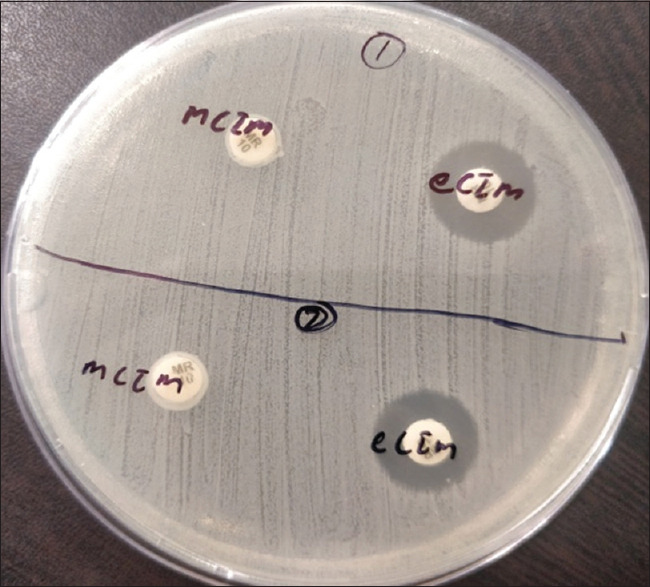

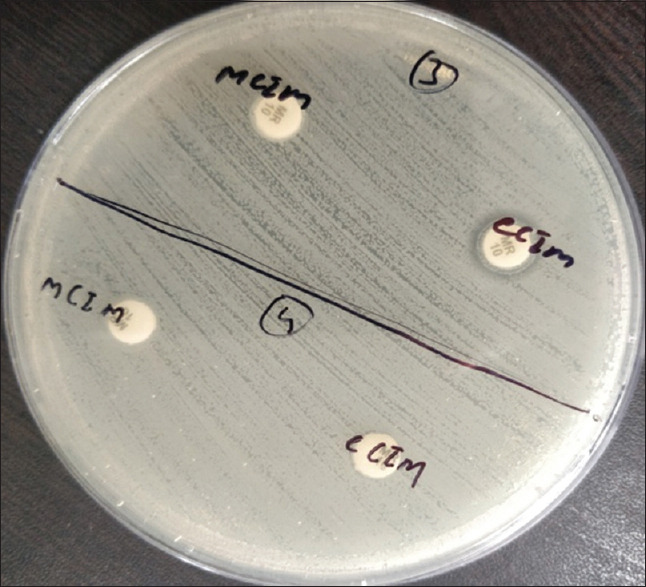

MHT was given positive in 26 CR-KP isolates and negative in 16 isolates. mCIM gave all genes (42) positive [Figures 1 and 2]. Thirty isolates were labeled as harboring MBLs and one as producing serine carbapenemases (OXA-48) by the eCIM test. A total of 11 isolates that were positive for CR-KP genes (seven for blaOXA48-like gene and four for both) by mCIM were negative for the eCIM test [Table 2 and Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Isolates 1 and 2 show mCIM and eCIM positive

Figure 2.

Isolates 3 and 4 show positive mCIM and negative eCIM

Table 2.

Comparison of CR-KP genes with phenotypic tests MHT, mCIM, eCIM (N=42)

| Real-time PCR | NDM (N=22) | OXA-48 (N=8) | NDM+OXA-48 (N=12) | Total (N=42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHT | ||||

| Positive | 10 | 7 | 9 | 26 |

| Negative | 12 | 1 | 3 | 16 |

| mCIM | ||||

| Positive | 22 | 8 | 12 | 42 |

| Negative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| eCIM | ||||

| Positive | 22 | 1 | 8 | 31 |

| Negative | 0 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

In this study, we have taken 30 carbapenemase-negative isolates as a control which was confirmed by mPCR. Our study presented that MHT is highly sensitive, 88% for the OXA-48 gene, moderate for coproducers (75%), and low for NDM (46%). The overall sensitivity of MHT for carbapenemase detection is 62%. Specificity, PPV, and NPV were 93%, 93%, and 64% [Table 3].

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity of MHT for the detection of carbapenemases producing K. pneumoniae isolates (N=72)

| NDM | OXA-48 | NDM+ OXA-48 | Carbapenemase negative (Controls N=30) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | 10 | 7 | 9 | - | 26 |

| FN | 12 | 1 | 3 | - | 16 |

| TN | - | - | - | 28 | 28 |

| FP | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 46 | 88 | 75 | - | 62 |

| Specificity (%) | - | - | - | 93 | 93 |

| PPV (%) | - | - | - | - | 93 |

| NPV (%) | - | - | - | 64 |

In the present study, after combining both carbapenem inactivation methods, we found that mCIM and eCIM tests were 88% sensitive and 97% specific in detecting MBLs (NDM, NDM+OXA-48), PPV is 97% while NPV is 90% [Table 4].

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of mCIM+eCIM test for the detection of carbapenemases producing K. pneumoniae isolates (N=72)

| mCIM+eCIM | Carbapenemase genes MBLs (NDM, NDM+OXA-48) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | TP (30) | FP (1) | 31 |

| Negative | FN (4) | TN (37) | 41 |

| Total | 34 | 38 | 72 |

| Sensitivity | 88% | ||

| Specificity | 97% | ||

| PPV | 97% | ||

| NPV | 90% | ||

This study showed that moderate biofilm producers were 51% (N = 56) K. pneumoniae isolates, strong biofilm producers 27% (N = 30), and 22% (N = 30) were weak/non-biofilm producers [Table 5].

Table 5.

Biofilm-producing capacity of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (N=110)

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Strong biofilm producer | 34 | 31 |

| Moderate biofilm producer | 52 | 47 |

| Weak/non-biofilm producer | 24 | 22 |

| Total | 110 | 100 |

In this study, we found highest sensitivity among the biofilm producers is given against the drug colistin, 97% followed by polymyxin-B, 92%, and amikacin 81%, and maximum resistance is shown against ampicillin 99%, ceftriaxone 74%, and ciprofloxacin 71%. In our study, we found that maximum sensitivity among non-biofilm producers was 100% given against the drug colistin, polymixin-B, meropenem, ertapenem, and fosfomycin. The highest resistance is shown against ampicillin at 92% followed by ciprofloxacin at 63% and norfloxacin at 50%.

In the present study, strong biofilm producers have been associated with 38% (16/42) CR-KP genes, moderate biofilm producers were only 57% while 5% were weak/non-biofilm producers. We also found the correlation between the biofilm formation ability of carbapenem-resistant genes with biofilm formation carbapenem sensitive isolates which was statistically significant with a P value of 0.003*<0.05 [Table 6].

Table 6.

Correlation between Biofilm formation ability with CR-KP genes and carbapenem-sensitive isolates (N=110)

| CR-KP genes associated with Biofilm formation | Biofilm formation with sensitive isolates | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N | % | NDM | OXA-48 | NDM+OXA-48 | |||

| Strong | 16 | 38 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 0.003<0.05 |

| Moderate | 24 | 57 | 16 | 2 | 6 | 28 | |

| Weak/non-biofilm producer | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 22 | |

| Total | 42 | 22 | 8 | 12 | 68 | ||

Discussion

Carbapenems serve as last-line antibiotics for severe infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. However, the production of carbapenemase enzyme renders bacteria resistant to nearly all traditional antibiotics including carbapenems, resulting in treatment failure and a high mortality rate.

Our study was conducted on a total of 670 clinical samples, out of that 110 (16.5%) samples showed growth of K. pneumoniae. This result was similar to a study conducted by Nirwati H et al.[15] (17%). However, a study by Khan ER et al.[16] reported a 51% isolation rate of K. pneumoniae among CRE isolates which was higher than our result. Variation in isolation rate may be associated with the fact that microbial growth varies from place to place based on environmental conditions and the health status of the population.

In our study, 66% (72/110) of total K. pneumoniae isolates were screened by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method with carbapenem disk (MRP/IPM/ETP) as carbapenem-resistant but 58% (42/72) of total K. pneumoniae isolates were confirmed for carbapenemase production by mPCR. Our result was lower than the previously published reports by Moghadampour M et al.[17] who reported a rate of 90% of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Our study showed a higher prevalence as compared to the study conducted by Srivastava et al.[18] and El-Badawy[19] who reported lower rates of 29.3% and 20%, respectively. Variation of carbapenemase resistance in K. pneumoniae has been reported by many studies in the range of 25 to 90%. This may be due to the use of different isolation techniques, use of different antibiotics, and methods of detecting genes in different places.

Our study showed that blaNDM genes were predominantly detected (52%) followed by the blaNDM+OXA-48 gene (29%), and blaOXA-48 gene (19%) in CR-KP. The high rate of blaNDM gene harboring K. pneumoniae was reported by Gupta V et al.[8] (70%).

Meatherall et al.[20] reported 75.4% blaOXA-48 gene harboring K. pneumoniae which was higher than our study. The study conducted by El-Domany R et al.[21] from Egypt revealed a high prevalence of 48% coharbored blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes as compared to our result. Our result was higher than a study conducted by Pyakurel S et al.[22] in Nepal in which the co-existence of both genes was found in 11.1% of the CR-KP. This may be due to geographical, environmental, and genus-based variations in carbapenemase gene distribution in different areas and countries. This has been documented by several researchers in their studies.

Our study showed that out of 42 CR-KP isolates, 65% were obtained from males and 35% from females. The findings of our results are similar to a study done by Amin A et al.[23] in Pakistan who found that the majority of the patients were males (64%) than females (36%). The higher incidence of K. pneumoniae in males may be due to a poor lifestyle in the form of smoking and alcoholism.

In our study, the maximum number of CR-KP isolates has been obtained from sputum 29% followed by urine 26% and pus sample 16%. Sample-wise variation has already been observed for the isolation of CR-KP in several studies. The sputum sample showed a 50% association with the coproducer gene. Our result is contrary to the study conducted by Wang P et al.[24] who reported that 71.4% of NDM-producing K. pneumoniae were isolated from sputum samples. However, our study is similar in the case of urine samples as a study conducted by Srivastav P et al.[18] (32.1%) where NDM producers were from urine samples. The high rate of NDM+OXA-48 producers from sputum samples may be due to the reason that a maximum number of the patients with carbapenemase-producing CR-KP were having respiratory tract infections which are easily transmitted by droplets in the hospital environment.

Our study showed that MHT is highly sensitive, with 88% for OXA-48 gene detection, a moderate 75% for coproducers, and at least 46% for NDM. The overall sensitivity of MHT for carbapenemase detection is 62%. Specificity, PPV, and NPV are 93%, 93%, and 64%, respectively. Our study showed higher sensitivity as compared to the study conducted by Pyakurel S et al.[22]; they have shown 51% positivity with carbapenemase genes by MHT. This may be due to that our study showed more OXA-48 genes (serine group) as compared to their study. Tsai YM et al.[13] reported higher sensitivity and specificity of MHT 85% and 98%, respectively, as compared to our study because they had more serine carbapenemases and fewer MBLs. MHT has some limitations as they are insensitive to the detection of MBL enzymes. MHT results are difficult to interpret and false positive results are observed for ESBL or AmpC beta-lactamases with porin loss.

Our study showed that mCIM has 100% sensitivity and specificity in detecting carbapenemase genes. However, 16 isolates with false negative results on MHT were mCIM positive. Our results showed the sensitivity of mCIM is 100% to detect MBLs and is more accurate as compared to MHT. mCIM can detect carbapenemase genes more accurately as reported by many studies but it cannot differentiate between serine and MBLs, therefore a modification of mCIM with the addition of eCIM has been endorsed in guidelines. After combining both carbapenem inactivation methods (mCIM+eCIM), we find that the test is 88% sensitive and 97% specific in detecting MBLs (NDM, NDM+OXA-48); PPV is 97% while NPV is 90%. Four isolates of MBLs showed false negatives with mCIM and eCIM tests. This result may suggest the expression of both carbapenemase genes may cause the misidentification of MBL genes by mCIM and eCIM tests. One isolate of the OXA-48 gene showed a false positive with eCIM based on the PCR targeting carbapenemase genes as a gold standard. Our study is very similar to a study conducted by Tsai YM et al.[13]; they reported sensitivity and specificity of mCIM is 100% and mCIM combined with eCIM showed sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 98%, respectively. A study conducted by Hu YM et al.[25] reported that the combined detection of mCIM and eCIM for serine carbapenemase had a sensitivity and specificity of 100%. The combined detection sensitivity and specificity of mCIM and eCIM for MBLs are 92.9% and 100%, respectively.

Our study showed that moderate biofilm producers are 47% (N = 52) K. pneumoniae isolates, strong biofilm producers 31% (N = 34), and 22% (N = 24) are weak/non-biofilm producers. This result was similar to a study by Hassan et al.[14] who showed that 29% produced strong and 47% of isolates showed moderate biofilm production. Mathur et al.[26] have also reported that 14.47%, 39.4%, and 46% of bacteria produced strong, moderate, and weak/none biofilm production, respectively.

In this study, we found highest sensitivity among the biofilm producers was against the drug colistin, 97%, and the maximum resistance was shown against ampicillin, 99%. We also found that maximum sensitivity among non-biofilm producers is 100% against the drug colistin, Polymixin-B, meropenem, ertapenem, and fosfomycin. Our study showed that biofilm producers have greater antibiotic resistance compared to non-biofilm producers of K. pneumoniae. This finding has been reported in many studies. A study conducted by Saha et al.[27] showed that all the biofilm-producing isolates demonstrated more resistant patterns as compared to non-biofilm producers.

In our study, strong biofilm producers were associated with 38% (16/42) CR-KP genes, moderate biofilm producers were only 57%, and 5% were weak/non-biofilm producers. Our study was contrary to a study conducted by Rahdar H et al.[28] showing 36% CR-KP genes with 52% strong, 38% moderate biofilm, and 10% weak/non-biofilm producers. We also found the correlation between biofilm formation ability and CR-KP genes is statistically significant with a P value of 0.01*<0.05. We could not find other carbapenemase genes (KPC/IPM/VIM); the reason behind this may be due to the higher prevalence of NDM/OXA-48/coproducers and the small sample size.

Conclusions

Understanding the carbapenem resistance pattern of K. pneumoniae has an important role in prevention and antibiotic therapy. In comparison to MHT, the phenotypic technique of mCIM paired with eCIM demonstrated greater sensitivity and specificity for detecting carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Among the bacterial population, the acquisition of specific antibiotic resistance may impact biofilm production. Consequently, the incidence of drug-resistant and biofilm-producing K. pneumoniae is increasing, primarily in hospital-associated settings, and the correlation of biofilm formation with antibiotic resistance acquisition is supported by our results and alerts us even more regarding the concern about this bacteria.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengoechea JA, Sa Pessoa J. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection biology: Living to counteract host defenses. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2019;43:123–44. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109:309–18. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyres KL, Holt KE. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;45:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veeraraghavan B, Shankar C, Karunasree S, Kumari S, Ravi R, Ralph R. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from bloodstream infection: Indian experience. Pathog Glob Health. 2017;111:240–6. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2017.1340128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazi M, Drego L, Nikam C, Ajbani K, Soman R, Shetty A, et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae at a tertiary care laboratory in Mumbai. Eur J Clin Microbial Infect Dis. 2015;34:467–72. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashurst JV, Dawson A. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): 2021. Klebsiella Pneumonia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta V, Garg R, Kumaraswamy K, Datta P, Mohi GK, Chander J. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Klebsiella pneumoniae from blood culture specimens: A study from North India. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10:125–9. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_155_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conlan S, Lau AF, Palmore TN, Frank KM, Segre JA NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Complete genome sequence of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain carrying bla NDM-1 on a multidrug resistance plasmid. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e00664–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00664-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donlan RM. Biofilms: Microbial life on surfaces. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:881–90. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patidar N, Vyas N, Sharma S, Sharma B. Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase production in carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae by modified Hodge test and modified Strip Carba NP test. J Lab Physicians. 2021;13:14–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1723859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Younger JJ, Baddour LM, Barrett FF, Melton DM, et al. Adherence of Coagulase negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: A Quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:996–1006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.996-1006.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai YM, Wang S, Chiu HC, Kao CY, Wen LL. Combination of modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-02010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan A, Usman J, Kaleem F, Omair M, Khalid A, Iqbal M. Evaluation of different detection methods of biofilm formation in the clinical isolates. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:305–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nirwati H, Sinanjung K, Fahrunissa F, Wijaya F, Napitupulu S, Hati VP, et al. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from clinical samples in a tertiary care hospital, Klaten, Indonesia. BMC Proc. 2019;13:20. doi: 10.1186/s12919-019-0176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan ER, Aung MS, Paul SK, Ahmed S, Haque N, Ahamed F, et al. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase genes in Bangladesh. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24:1568–79. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghadampour M, Rezaei A, Faghri J. The emergence of bla OXA-48 and bla NDM among ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in clinical isolates of a tertiary hospital in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2018;65:335–44. doi: 10.1556/030.65.2018.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava P, Bisht D, Kumar A, Tripathi A. Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in rural Uttar Pradesh. J Datta Meghe Institute Med Sci Univ. 2022;17:584. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Badawy MF, El-Far SW, Althobaiti SS, Abou-Elazm FI, Shohayeb MM. The First Egyptian report showing the co-existence of bla NDM-25, bla OXA-23, bla OXA-181, and bla GES-1 among carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae clinical isolates genotyped by BOX-PCR. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;29:1237–50. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S244064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meatherall BL, Gregson D, Ross T, Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Am J Med. 2009;122:866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Domany RA, Emara M, El-Magd MA, Moustafa WH, Abdeltwab NM. Emergence of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Egypt Coharboring VIM and IMP carbapenemases. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2017;23:682–6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pyakurel S, Ansari M, Kattel S, Rai G, Shrestha P, Rai KR, et al. Prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae at a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Trop Med Health. 2021;49:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00368-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amin A, Ghumro PB, Hussain S, Hameed A. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Pakistan. Malaysian J Microbiol. 2009;5:81–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang P, Chen S, Guo Y, Xiong Z, Hu F, Zhu D, et al. Occurrence of false positive results for the detection of carbapenemases in carbapenemase-negative Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu YM, Li J. Clinical application of mCIM and eCIM combined detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Zhonghua yu Fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine] 2021;55:506–11. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20200821-01142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathur P. Prevention of healthcare-associated infections in low- and middle-income Countries: The 'bundle approach'. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2018;36:155–62. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_18_152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha A, Devi KM, Damrolien S, Devi KS, Krossnunpuii, Sharma KT. Biofilm production and its correlation with antibiotic resistance pattern among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital in north-East India. Int J Adv Med. 2018;5:964–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahdar HA, Malekabad ES, Dadashi AR, Keikha M, Kazemian H, Karami-zarandi M. Correlation between biofilm formation and carbapenem resistance among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2019;29:745–50. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i6.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]