ABSTRACT

Background:

Domestic violence (DV) against women is a global problem and is present in every country. It is a matter of serious concern in most communities and cultures and has consequences on women’s mental, physical, reproductive, and sexual health. The study aimed to determine the prevalence and pattern of DV among married women.

Materials and Methods:

A community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted among 400 reproductive age group females in the rural area of district Saharanpur for a period of six months using multistage random sampling.

Results:

The prevalence of DV was found to be 21%. The most common type of DV was physical violence (18%) followed by psychological violence (12.8%), financial violence (5.5%), and sexual violence (2.3%). The major perpetrators of DV were the husbands in 79% of the cases. Regression analysis depicted a significant association between age, education of husband, husband’s addiction, and depression of study participants with events of DV. Multivariate analysis shows only the addictions of husbands and the depression status of study participants to be significantly associated with DV.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of DV was 21% which is still high and appropriate measures should be taken to strengthen the laws for women and to empower them.

Keywords: Domestic violence, mental health, reproductive health, rural women

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) against women is the most common type of violence against women. Violence is a behavioral pattern characterized by creating fear, threats, or rude behavior to achieve control over another person. This violence can be physical (beating), mental (humiliation), financial (husband withholding money from wife, husband hiding income from wife), and sexual (forced sexual relationship or belittling sexual expression).[1] DV against women is a global problem that is underreported and has a detrimental effect on the health and wellbeing of women. DV harms the physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health of millions of women resulting in depression, suicide, and temporary or permanent disability. It occurs globally in both developed and developing nations, regardless of culture, religion, or socioeconomic status, and varies in prevalence, type, and extent from one place to another.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) defines domestic violence as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, against a group, or a community that results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.[3] According to the World’s Women 2020: Trends and Statistics report, about one-third of women in the world have suffered physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner at some point in time.[4] Globally, an estimated 137 women are killed by their intimate partner or a family member every day. Women experience extremely high rates of violence in the sub-Saharan African (SSA) nations, particularly in areas with low socioeconomic status and inadequate access to education.[4] The WHO reported a few factors that are associated with increased risk of experiencing intimate partner violence, which include low educational qualification, exposure to violence between parents, abuse during childhood, and attitudes to accept violence and gender inequality.[5] Individuals, families, communities, and society are all affected by DV against women. It results in harm or death for individuals, difficulties with reproductive health, risky drug and alcohol use, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-harm, and suicide.[6,7,8] For families, it causes miscarriage, forced abortions, stillbirths, low birth weights, preterm deliveries, and more acts of violence.[9,10] It results in a lack of agency, limited engagement, and decreased economic productivity for communities and society.[10,11] In terms of women’s morbidity and mortality, it significantly contributes to the global burden of ill health, including rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections, psychological trauma and depression, suicide and murder, chronic pain, injuries, fractures, and disability.[12]

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 in India, among women aged 18–49 years, 29.3% of women experienced spousal violence after marriage, among which 31.6% were reported from rural families itself.[13] According to NFHS, data prevalence of DV in Uttar Pradesh is 34.8%.[14]

There is a lack of knowledge on this issue in India, particularly regarding the prevalence of DV and its contributing causes in rural areas. Therefore, the current study was carried out in the rural population of Saharanpur among married women of reproductive age 18–49 years with the objective of studying the prevalence, pattern, and causes of DV to provide recommendations to the lawmakers and enable the judicial system to handle medico-legal issues appropriately.

Material and Methods

Study design

A community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted in the rural area of district Saharanpur for a period of six months (October to March 2023).

Participants

All the married women >18 years of age were included in the study. Women who were seriously ill/unable to speak and did not consent to participate in the study were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the formula

n = [Z2 1-α/2*p (1-p)/d2],

where Z is the normal standard deviation set at 1.96, at 95% confidence level, d is the tolerable margin of error taken as 5%, and P is the prevalence of DV taken as 34.8%.[14] After adding a 5% non-response rate, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 366 rounded off to 400.

Method

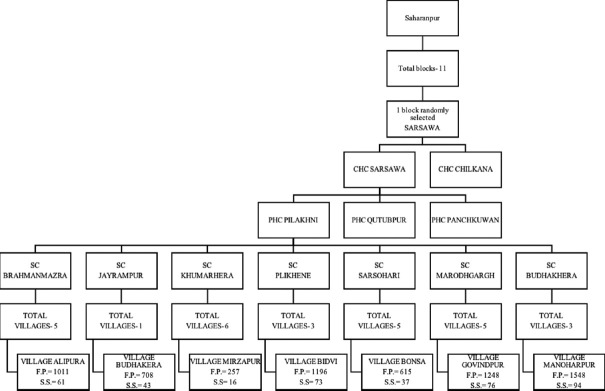

District Saharanpur is divided into 11 blocks, namely, Sadholi Kadeem, Muzaffarabad, Punwarka, Balia Kheri, Sarsawa, Nakur, Gangoh, Rampur Maniharan, Nagal, Nanauta, and Deoband. For the study purpose, out of these 11 blocks, one block was randomly selected, i.e., Sarsawa consisting of two Community Health Centers (CHCs)—Sarsawa and Chilkana—out of which one CHC, i.e., Sarsawa was randomly chosen. The CHC chosen had three Primary Health Centers (PHCs) under it, out of which one PHC, i.e., Pilakhni was randomly selected. The selected PHC has seven subcenters catering to the needs of 28 villages. A list of all the villages under each subcenter was prepared and one village from each subcenter was selected [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sampling method (F.P.- Female population; S.S.- Sample Size)

The total female population of the selected seven villages was obtained and the total number of women to be interviewed from each village was calculated using probability proportional to sample size technique [Figure 1].

A landmark in each village was decided (Anganwadi center, school, or a temple) where a bottle was spun. The starting point of the data collection was the first house pointing towards the tip of the bottle. If the woman in the house was found to be eligible for the study, data was collected using the study tool. The consecutive houses were visited till the desired sample from that village was obtained. If in case more than one eligible women were found in the house, then all the women were included in the study. If a house was locked or had no eligible women, then the adjoining house was visited.

Data collection

Data were collected preferably in the morning hours when the male members of the family had gone out in the field or to do their respective work. Data was collected using a predesigned pretested semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated into the local language and it consisted of five sections.

Section 1 contained information on sociodemographic factors; section 2 collected information on addiction of study participants and their spouse; section 3 collected information on the type of DV faced by study participant divided into physical, psychological, sexual, and financial [defined in the supplementary files]; section 4 collected information on reproductive health; and section 5 contained questions on mental health using Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).[15]

A pilot study was conducted on 20 women aged >18 years from the field practice area and the data collected was not included in the study sample. Based on the results of the pilot study, few changes were made to the questionnaire so that the questionnaire was better suited for the study populations.

Data analysis

Depending on the violence faced by the study participants, the participants were classified into two categories (faced DV/did not face DV).

The PHQ-9 scale contained nine questions whose scores were graded as 0, 1, 2, and 3. A total score was calculated by adding up the scores of all nine items. Based on the final score, the women were classified as follows: minimal depression (1–4), mild depression (5–9), moderate depression (10–14), moderately severe depression (15–19), and severe depression (20–27).

Based on the total scores of the PHQ-9 scale, the study participants were also classified as not depressed or depressed if the total scores were zero or not zero, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire forms were checked for completeness and quality, then the data were entered in Microsoft Excel for Mac, Version 16.6. The entered data was checked and in case of any incorrectness, it was matched with the respective questionnaire. The data were then analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0, IBM Inc. Chicago, USA software after coding it. Descriptive analysis was done for sociodemographic parameters, addiction status, DV parameters, reproductive history, and depression status. To observe any relationship between sociodemographic variables, addiction status, reproductive parameters, and depression status with a history of DV, a Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test was used. If any relationship was established, then regression analysis was done to find the degree of association which was represented in terms of odds ratio. For all the analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Tertiary Care Center of Saharanpur district. As the PHQ-9 was available publicly, hence no permission for its use for required. While collecting the data, privacy was ensured, and after explaining the purpose of the study, written consent was obtained from each study participant.

Results

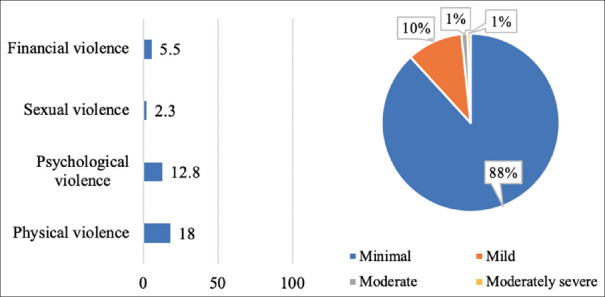

In the present study, data was collected from 400 married women from the rural field practice area of Saharanpur among which, 21% reported being abused in some form of DV among which physical violence was reported by the majority (18.0%) while sexual abuses were the least reported (2.3%) [Figure 2]. “Slapping” was the most commonly reported type of physical violence while “humiliating/insulting in front of others” was the most common psychological violence. The duration of violence for 78.3%, 15.5%, and 6.3% of women who faced DV was <1 year, 1 to 5 years, and >5 years, respectively. The major perpetrators of DV were the husbands in 79% of the cases while it was the family in case of 11.5%.

Figure 2.

Distribution of study participants based on the prevalence of types of violence and depression

Based on the PHQ-9, 59% of the study participants reported no depression while among the rest, depression was categorized from minimal to moderately severe category [Figure 2].

The majority of women (92%) belonged to the age group of 15–49 years who were Hindu by religion (61.3%) [Table 1]. Maximum participants belonged to the Other Backward Class (OBC) caste (60%), lived in joint families (68%), and belonged to a low socioeconomic class (89.8%). Around 60% of the women studied up to intermediate while 74.3% were housewives and they were financially dependent on their husbands (84.8%).

Table 1.

Association of domestic violence with sociodemographic factors (n=400)

| Sociodemographic variables | Subvariables | n (%) | Domestic violence | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age | 18-49 | 368 (92) | 70 (19.0) | 298 (81.0) | 10.851 | <0.01 |

| >50 | 32 (8) | 14 (43.8) | 18 (56.3) | |||

| Religion | Hindu | 245 (61.3) | 52 (21.2) | 193 (78.8) | 0.19 | 0.890 |

| Muslim | 155 (38.8) | 32 (20.6) | 123 (79.4) | |||

| Caste | General | 99 (24.8) | 18 (18.2) | 81 (81.8) | 0.678 | 0.712 |

| OBC | 240 (60.0) | 52 (21.7) | 188 (78.3) | |||

| SC/ST | 61 (15.3) | 14 (23.0) | 47 (77.0) | |||

| Type of family | Nuclear | 128 (32) | 34 (26.6) | 94 (73.4) | 3.511 | 0.61 |

| Joint and three generation | 272 (68) | 50 (18.4) | 222 (81.6) | |||

| Education | Illiterate and just literate | 104 (26.0) | 27 (26.0) | 77 (74.0) | 3.826 | 0.148 |

| 1st–12th | 247 (61.8) | 51 (20.6) | 196 (79.4) | |||

| Graduate and above | 49 (12.3) | 6 (12.2) | 43 (87.8) | |||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 297 (74.3) | 60 (20.2) | 237 (79.8) | 1.267 | 0.531 |

| Unskilled to clerical | 91 (22.8) | 20 (22.0) | 71 (78.0) | |||

| Semi and professional | 12 (3.0) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | |||

| Education of the husband | Illiterate and just literate | 69 (17.3) | 22 (31.9) | 47 (68.1) | 9.521 | <0.01 |

| 1st-12th | 270 (67.5) | 56 (20.7) | 214 (79.3) | |||

| Graduate and above | 61 (51.3) | 6 (9.8) | 55 (90.2) | |||

| Occupation of the husband | Unemployed | 8 (2.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4.924 | 0.085 |

| Unskilled to clerical | 352 (88.0) | 74 (21.0) | 278 (79.0) | |||

| Semi and professional | 40 (10.0) | 6 (15.0) | 34 (85.0) | |||

| Nature of the marriage | Arranged | 384 (96) | 81 (21.1) | 303 (78.9) | 0.51 | 1.000 |

| Love | 16 (4.0) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | |||

| Duration of marriage | 0-10 years | 195 (48.8) | 28 (14.4) | 167 (85.6) | 10.115 | <0.01 |

| >10 years | 205 (51.2) | 56 (27.3) | 149 (72.7) | |||

| Any previous marriage | Yes | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0.266 | 1.000 |

| No | 399 (99.8) | 84 (21) | 315 (78.9) | |||

| Husband previous marriage | Yes | 1 (0.3) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 3.771 | 0.210 |

| No | 399 (99.8) | 83 (20.8) | 316 (79.2) | |||

| Financially dependent on husband | Yes | 359 (89.8) | 70 (19.5) | 289 (80.5) | 4.759 | <0.05 |

| No | 41 (10.3) | 14 (34.1) | 27 (65.9) | |||

| Socioeconomic status | Upper | 17 (4.3) | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | 1.819 | 0.403 |

| Middle | 44 (11.0) | 7 (15.9) | 37 (84.1) | |||

| Lower | 339 (84.8) | 75 (22.1) | 264 (77.9) | |||

None of the participants were addicted to alcohol or tobacco; however, 1.8% reported the use of smokeless tobacco [Table 2]. On the contrary, 15.3%, 21.3%, and 12.0% of the spouses were addicted to alcohol, tobacco, and smokeless tobacco, respectively.

Table 2.

Association of domestic violence with behavioral factors (n=400)

| Addiction | Subvariables | n (%) | Domestic violence | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Consumes alcohol | No | 400 (100.0) | 84 (21) | 316 (79.0) | - | - |

| Smokes tobacco | No | 400 (100.0) | 84 (21) | 316 (79.0) | - | - |

| Consume smokeless tobacco | Yes | 7 (1.8) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | 10.921 | <0.01 |

| No | 393 (98.2) | 79 (20.1) | 314 (79.9) | |||

| Husband consumes alcohol | Yes | 61 (15.3) | 33 (54.1) | 28 (45.9) | 47.529 | <0.01 |

| No | 339 (84.8) | 51 (15.0) | 288 (85.0) | |||

| Husband smokes tobacco | Yes | 85 (21.3) | 37 (43.5) | 48 (56.5) | 33.023 | <0.01 |

| No | 315 (78.8) | 47 (14.9) | 268 (85.1) | |||

| Husband consumes smokeless tobacco | Yes | 48 (12.0) | 27 (56.3) | 21 (43.8) | 40.854 | <0.01 |

| No | 352 (88.0) | 57 (16.2) | 295 (83.8) | |||

| Depression among women | Yes | 48 (29.3) | 116 (70.7) | Yes | 11.455 | <0.01 |

| No | 36 (15.3) | 200 (84.7) | No | |||

Univariate regression depicted a significant association between age, education of husband, husband’s addiction, and depression of study participants with events of DV [Table 3, 4]. However, on multivariate analysis, only the addictions of the husband and the depression status of study participants were found to be significantly associated.

Table 3.

Association of domestic violence with reproductive health (n=400)

| Reproductive health | Subvariables | n (%) | Domestic violence | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Currently pregnant | Yes | 119 (29.8) | 13 (10.9) | 106 (89.1) | 10.366 | <0.01 |

| No | 281 (70.3) | 71 (25.3) | 210 (74.7) | |||

| Number of children | 1-5 | 320 (80.0) | 69 (21.6) | 251 (78.4) | 0.305 | 0.581 |

| >5 | 80 (20.0) | 15 (18.8) | 65 (81.3) | |||

| Gender of children | All females | 74 (18.5) | 14 (18.9) | 60 (81.1) | 3.917 | 0.141 |

| Any male | 274 (68.5) | 64 (23.4) | 210 (76.6) | |||

| Infertility | Yes | 7 (1.8) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.246 | 0.641 |

| No | 393 (98.3) | 82 (20.9) | 311 (79.1) | |||

| Any menstrual disorder | Yes | 32 (8.0) | 9 (28.1) | 23 (71.9) | 1.064 | 0.302 |

| No | 368 (92) | 75 (20.4) | 293 (79.6) | |||

| Any genital tract infection | Yes | 28 (7.0) | 9 (32.1) | 19 (67.9) | 2.253 | 0.133 |

| No | 372 (93.0) | 75 (20.2) | 297 (79.8) | |||

| History of abortion | Yes | 83 (20.8) | 20 (24.1) | 63 (75.9) | 0.605 | 0.437 |

| No | 317 (79.3) | 64 (20.2) | 253 (79.8) | |||

| Any pregnancy complications | Yes | 23 (5.8) | 6 (26.1) | 17 (73.9) | 0.381 | 0.597 |

| No | 377 (94.3) | 78 (20.7) | 299 (79.3) | |||

| Institutional deliveries | Yes | 235 (58.8) | 42 (17.9) | 193 (82.1) | 3.359 | 0.067 |

| No | 165 (41.3) | 42 (25.5) | 123 (74.5) | |||

| Received antenatal care | Yes | 288 (72.0) | 53 (18.4) | 235 (81.6) | 4.182 | <0.05 |

| No | 112 (28.0) | 31 (27.7) | 81 (72.3) | |||

| Received postnatal care | Yes | 249 (62.3) | 49 (19.7) | 200 (80.3) | 0.694 | 0.405 |

| No | 151 (37.8) | 35 (23.2) | 116 (76.8) | |||

| Use of family planning | Yes | 59 (14.8) | 19 (32.2) | 40 (67.8) | 5.236 | <0.01 |

| No | 341 (85.3) | 65 (19.1) | 276 (80.9) | |||

| Problem in breast feeding | Yes | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 1.346 | 0.589 |

| No | 395 (98.8) | 84 (21.0) | 316 (79.0) | |||

Table 4.

Regression analysis for factors of domestic violence (n=400)

| Variables | Subvariables | n (%) | Domestic violence | UOR | P | AOR | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18-49 | 368 (92) | 70 (19.0) | 3.126 (1.491-6.538) | <0.01 | 1.079 (0.407-2.862) | 0.879 |

| >50 | 32 (8) | 14 (43.8) | |||||

| Education of the husband | Illiterate | 69 (17.3) | 22 (31.9) | 2.031 (1.141-3.615) | <0.05 | 1.840 (0.903-3.753) | 0.093 |

| Literate | 331 (82.8) | 62 (18.7) | |||||

| Duration of marriage | 0-10 yrs | 195 (48.8) | 28 (14.4) | 2.242 (1.353-3.713) | <0.05 | 1.592 (0.863-2.936) | 0.137 |

| >10 yrs | 205 (51.2) | 56 (27.3) | |||||

| Financially dependent on husband | Yes | 359 (89.8) | 70 (19.5) | 2.141 (1.067-4.295) | <0.01 | 1.632 (0.706-3.775) | 0.252 |

| No | 41 (10.3) | 14 (34.1) | |||||

| Consume smokeless tobacco | Yes | 7 (1.8) | 5 (71.4) | 9.937 (1.893-52.170) | <0.01 | 6.613 (0.977-44.759) | <0.05 |

| No | 393 (98.2) | 79 (20.1) | |||||

| Husband consumes alcohol | Yes | 61 (15.3) | 33 (54.1) | 6.655 (3.708-11.947) | <0.01 | 3.995 (1.966-8.120) | <0.01 |

| No | 339 (84.8) | 51 (15.0) | |||||

| Husband smokes tobacco | Yes | 85 (21.3) | 37 (43.5) | 4.395 (2.590-7.461) | <0.01 | 2.769 (1.456-5.269) | <0.01 |

| No | 315 (78.8) | 47 (14.9) | |||||

| Husband consumes smokeless tobacco | Yes | 48 (12.0) | 27 (56.3) | 6.654 (3.520-12.580) | <0.01 | 3.512 (1.631-7.561) | <0.01 |

| No | 352 (88.0) | 57 (16.2) | |||||

| Received antenatal care | Yes | 288 (72.0) | 53 (18.4) | 1.697 (1.019-2.826) | <0.05 | 1.457 (0.775-2.740) | 0.242 |

| No | 112 (28.0) | 31 (27.7) | |||||

| Use of family planning | Yes | 59 (14.8) | 19 (32.2) | 2.017 (1.097-3.709) | <0.05 | 1.747 (0.836-3.652) | 0.138 |

| No | 341 (85.3) | 65 (19.1) | |||||

| Depression | Yes | 164 | 48 (29.3) | 2.299 (1.410-3.748) | <0.01 | 2.064 (1.140-3.739) | <0.05 |

| No | 236 | 36 (15.3) |

Discussion

DV against women is a global problem and is present in every country. It is a matter of serious concern in most communities and cultures and has consequences on women’s mental, physical, reproductive, and sexual health.

In the present study, the prevalence of DV among women was reported to be 21% which was very low when compared with the data of NFHS-5 Uttar Pradesh where the prevalence was reported to be 35.5%.[14] Even in other studies like that of Vinay J et al.,[16] Jawarkar AK et al.,[17] Ahmad J et al.,[18] and Babu BV et al.,[19] the prevalence of DV reported has been very high (39.5%, 40.25%, 47%, and 56%, respectively). The difference in results could be because of three reasons; first, the sample size taken here was small and limited to district whereas other studies have reported the results from a larger sample size. Secondly, not only the prevalence of DV is higher among reproductive age group women but also the studies conducted are more focused on this age group.[19] However, the sample size of the present study included all the married women from all age groups, hence this factor could have diluted the prevalence in this study. Thirdly, DV being a sensitive issue tends to be underreported.

This study depicted that the low education of husbands resulted in a two times higher prevalence of DV faced by their spouses. Similarly, addictions of husbands; be it alcohol, tobacco, or smokeless tobacco were identified as a major risk factor for DV in the present study. Study of Vinay J et al.[16] also reported similar findings where illiterate husbands were four times more violent with their spouses. Literature suggested that the prevalence of DV was four times higher if the husband was found to be an alcoholic and two times more if the husband was found to be a smoker.[20,21] Results from the present study also depict the same as the odds of DV increased fourfold if the husband was an alcoholic and nearly threefold if he consumed tobacco. Strategies of educational empowerment and efforts to discourage excessive consumption of alcohol intake and substance abuse can lead to a change in attitude and prevention of DV.[2,22,23,24]

Exposure to DV not only makes a woman vulnerable to addictions but also lowers their self-esteem which leads to depression.[25,26,27] The present study also stated a similar finding as 71.3% of the abused women were addicted to smokeless tobacco and 29.3% of them were suffering from depression. The factor of mental disorders among women was found to be strongly associated with violence against women in a study conducted by Sharma et al.[12] Bivariable associations in Lövestad et al.[28] stated that women who were exposed to physical and sexual violence were 3.78 and 5.10 times at a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms similar to the present study where the risk was 2.064 times.

In spite of the high prevalence of DV in rural communities of Uttar Pradesh, this is the first community-based study to collect information on DV in the study area. Therefore, the results of this study will prove beneficial to target interventions through which women can be educated about the policies and programs implemented by the government to protect themselves from DV.

Considering the sensitive nature of the issue, there is a scope of underreporting and also the current study design does not link causality of the risk factors to DV. Hence, there is a need to conduct similar studies in different study designs which can help in overcoming this limitation.

Conclusion

Overall prevalence of DV was found to be 21% among which physical violence was the most common type of DV. Addiction habits of the husband was found to be the independent risk factors for DV. While addictions among the women and their mental status also had significant associations with the prevalence of DV.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank our head of department, faculty members, and the study participants.

SUPPLEMENTARY FILE

Physical violence included beating, slapping, twisting an arm, pulling of hair, kicking, pushing, shaking, dragging, banging the head, throwing something, hit or punch with fist or with something that could hurt, pinching, threatened or attacked with knife, gun, or any other weapon, burning, suffocating/ chocking or poisoning.

Psychological violence included jealous, becoming angry if the women talked to other men, accused of being unfaithful, not permitting to meet female friends, limiting to contact her family, insisting on knowing her whereabouts, humiliating/insulting in front of others, threatening to hurt, body shaming, isolating and not including in family decisions, blaming for every negative thing, being unfaithful or having an extramarital affair, treating like a servant, insulting for not having baby, insulting for not having son, threatening to send to parents house, not allowing to work, commenting on not cooking properly.

Sexual violence included pressure for sex, hurting during sex, having forceful unprotected sex, having forced to perform unnatural sexual practices, ignored her purposely by not having sexual intercourse with her for weeks, under the influence of alcohol while having sex, forceful sex during menstruation, forced to have sex with other person.

Financial violence included demand of dowry, keeping record of all expenses, denying of basic needs/ not allowing to spend, taking all salary, threatening to deprive the women and children from using financial resources/assets, not trusting her with any money.

References

- 1.Yari A, Zahednezhad H, Gheshlagh RG, Kurdi A. Frequency and determinants of domestic violence against Iranian women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1727. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nmadu AG, Jafaru A, Dahiru T, Joshua IA, Nwankwo B, Mohammed-Durosinlorun A. Cross-sectional study on knowledge, attitude and prevalence of domestic violence among women in Kaduna, north-western Nigeria. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e051626. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051626. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women. World Health Organziation. 2005. [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 16]. Available:https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43310/9241593512_eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

- 4.United Nations. The World's Women 2020: Trends and Statistics. New York: Statistics Division Demographic and Social Statistics; 2020. 2020. [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 16]. Available:https://worlds-women-2020-data-undesa.hub.arcgis.com . [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Factsheet on Violence against women. World Health Organization. 2024. [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 16]. Available:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women#:~:text=Globally%20as%20many%20as%2038, sexual%20violence%20are%20more%20limited .

- 6.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stöckl H, Devries K, Rotstein A, Abrahams N, Campbell J, Watts C, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review. Lancet. 2013;382:859–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satyanarayana VA, Chandra PS, Vaddiparti K. Mental health consequences of violence against women and girls. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:350–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 16]. Available:https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris-Gehring A, Heise L, Amin A, Abrahams N, et al. Addressing violence against women: A call to action. Lancet. 2015;385:1685–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solotaroff JL, Pande RP. Violence against women and girls: Lessons from South Asia. South Asia Development Forum, World Bank Forum. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma KK, Vatsa M, Kalaivani M, Bhardwaj D. Mental health effects of domestic violence against women in Delhi: A community-based study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2522–7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_427_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Family welfare. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5)- India fact sheet. [Last accessed on 2023 May 12]. Available from:http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/India.pdf .

- 14.Ministry of Health and Family welfare. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5)- State fact sheet: Uttar Pradesh. [Last accessed on 2023 May 12]. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/Uttar_Pradesh.pdf.

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ- 9:a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinay J, Raghavendra SK, Thejaswini P, Kumar AV. A cross-sectional study on domestic violence among married women of reproductive age in rural Mandya. Indian J Forensic Community Med. 2019;6:188–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jawarkar AK, Shemar H, Wasnik VR, Chavan MS. Domestic violence against women: A cross sectional study in rural area of Amravati district of Maharashtra, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:2713–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad J, Khan ME, Mozumdar A, Varma DS. Gender-based violence in rural Uttar Pradesh, India: Prevalence and association with reproductive health behaviors. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31:3111–28. doi: 10.1177/0886260515584341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babu BV, Kar SK. Domestic violence against women in eastern India: A population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, Gupta V. The risk factor of domestic violence in India. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37:153–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.99912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finnbogadóttir H, Dykes AK, Wann-Hansson C. Prevalence of domestic violence during pregnancy and related risk factors: A cross-sectional study in southern Sweden. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:1–3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-63. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson J. Effects of Education on Victims of Domestic Violence. Walden University. 2015. [Last accessed on 2023 May 12]. Available from:https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1345&context=dissertations .

- 23.Taghdisi MH, Estebsari F, Dastoorpour M, Jamshidi E, Jamalzadeh F, Latifi M. The impact of educational intervention based on empowerment model in preventing violence against women. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e14432. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.14432. doi:10.5812/ircmj.14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J, Rambo K, Irving S, Armstead TL, et al. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies and Practise. National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control. Division of Violence Prevention. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:266–71. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. JAMA. 2008;300:703–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heise L, Ellsberg M. Ending Violence Against Women [Internet] Population Information Program, Centes for Communication Programs, The John Hopkins University School of Public Health. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lövestad S, Löve J, Vaez M, Krantz G. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and its association with symptoms of depression;a cross-sectional study based on a female population sample in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:335. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4222-y. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4222-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]