ABSTRACT

Background:

The postpartum period is critically important for comprehensive obstetric care; however, most women are neglected during this important period.

Objective:

This study was carried out to determine the burden of postpartum morbidities and associated factors among the urban vulnerable population in Gautam Buddha district, Uttar Pradesh.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 150 postpartum women in urban slums of Gautam Buddha district. A semi-structured questionnaire was used along with a physical examination and assessment of anemia by Sahli’s hemoglobinometer.

Results:

A total of 106 (70.7%) mothers reported at least one of the postpartum morbidities (PPMs). The most frequently reported morbidity was anemia (55.3%) followed by backache (29.3%). Almost a third (39, 36.8%) of all women, who suffered from PPM, did not seek any treatment for the same. Univariate analysis revealed that morbidities were higher among women with low literacy (Odds Ratio, OR: 5.63, 95% CI: 2.508–13.54, p = 0.000), low socioeconomic status (OR: 0.317, 95% CI: 0.151–0.657, p = 0.002), and inadequate antenatal care (OR: 0.108, 95% CI: 0.044–0.246, p = 0.0001). Similarly, young mothers (OR: 2.599, 95% CI: 1.332–5.14), less educated (OR = 3.603, 95% CI: 1.838–7.203, p = 0.000), those from lower economic status (OR: 0.247, 95% CI: 0.119–0.497, p = 0.001), with inadequate antenatal care (OR: 0.112, 95% CI: 0.052–0.232, p = 0.005), and low iron folic acid intake (OR: 0.371, 95% CI: 0.184–0.732, p = 0.004) showed higher prevalence of anemia.

Conclusion:

The role of education and adequate antenatal care are highlighted in the study. Antenatal visits should be utilized as opportunities to increase awareness regarding various aspects of care during the postnatal period. Maintaining more comprehensive support and involvement between health care providers and the mothers is needed to prevent many of these postpartum morbidities.

Keywords: Anemia, postpartum morbidity, prevalence, mother and child health

Introduction

The postpartum period is a highly sensitive period for any pregnant woman, owing to physical as well as emotional vulnerability. The postpartum period begins soon after the delivery of the baby and usually lasts six to eight weeks and ends when the mother’s reproductive system has nearly returned to its prepregnant state. The postpartum period for a woman and her newborn is very important for both short-term and long-term health and well-being.[1] To ensure healthy motherhood, all causes of maternal mortality, maternal morbidities, and related disabilities need to be addressed together. Although the maternal mortality rate (MMR) has fallen from 130 per 100,000 live births in 2014–16 to 97 in 2018–20, it has been well established that maternal mortality represents only the tip of the iceberg, with the hidden portion being maternal morbidity.[2]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the postpartum period, or puerperium, as beginning immediately after the delivery of the baby and after-births continuing until 6 weeks (42 days) after the birth of the baby.[3] The burden of maternal morbidity, like that of maternal mortality, is estimated to be highest in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially among poor and vulnerable women.[4] The LMICs bear the greatest brunt of maternal morbidity because the postpartum period is the most neglected in these countries.[5] The true prevalence of maternal morbidity is still not known in most of the LMICs.

The postpartum period has been mostly ignored in terms of healthcare coverage. It has been repeatedly observed in LMICs that less than one-third of females receive any form of postnatal care.[6] The care and attention given to the woman by the family and the healthcare providers tend to shift toward the newborn after delivery, often leading to postpartum morbidity (PPM). Maternal morbidities can range from mild to severe complications, like hemorrhage or sepsis which can be life-threatening, but non-life-threatening illnesses occur more often. The PPM includes infection, anemia, breastfeeding problems, breast complications, bowel and bladder problems, backache, episiotomy wound complications, genital tract injuries, perineal pain, cesarean wound complications, hemorrhoids, headaches, and depression.[7,8,9,10] Anemia, which is one of the more prevalent PPMs can consequently lead to complications such as postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, preterm labor, low birth weight, and neonatal infections.[11]

Demographic factors such as religion, occupation, low standard of living, and obstetric factors such as place of delivery and type of delivery were found to be associated with various morbidities.[7]

In India, women seek postnatal care only if the problem becomes physically debilitating. In terms of disease burden, maternal morbidities are cited as the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost among women in the reproductive age group in LMICs.[12]

India has launched various schemes and initiatives to enhance maternal healthcare. Most of the schemes concentrate on antenatal care, intranatal care, and institutional delivery. However, it is now well understood that postnatal health is directly linked to antenatal health, and continuity of care from the antenatal period through the postpartum period is essential for preventing maternal deaths. The examination of mother and infant along with postpartum care counseling is part of home-based newborn care (HBNC), under which accredited social health activists (ASHAs) are required to recognize postpartum complications and refer appropriately.

Residents living in slum areas often face increased exposure to diseases and have limited access to healthcare services. For rational policy-making, inputs from studies among the underprivileged populations living in urban slums are essential. Such baseline statistics are missing for urban slums. Moreover, studies focused on maternal morbidity often rely on hospital-based data, offering insights primarily into those seeking medical attention rather than providing a comprehensive view of the entire population. With this background, the current study was done to measure the burden of postpartum morbidity and its determinants in an urban slum of Gautam Buddha Nagar, India.

Methodology

A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out from January 2017 to January 2018 among postpartum mothers residing in urban slum colonies in Gautam Buddha Nagar district, Uttar Pradesh, India. The area was attached to the urban field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine of a tertiary care teaching hospital in the same district.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated assuming the prevalence of postpartum morbidities to be 10.2% as per a study conducted in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra,[13] absolute error of 5%, power of 80%, and confidence interval of 95%. The sample size was 141 and was rounded off to 150 women.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All married women who were one to six weeks postpartum during the study period and those who had been residing for more than six months in the study area were selected for the study. Pregnancies not resulting in live birth or culminating into neonatal deaths, women from uncooperative families, and those women who were not available even on two subsequent visits were excluded.

Data collection

A list of deliveries in the study area during the period of data collection was obtained from accredited social health activist (ASHA) and Anganwadi workers. All the postpartum women were identified from the list, and subsequently, these women were contacted by conducting house-to-house visits. The women who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and consented to participate were included in the study. One Anganwadi has a maximum 2000 population; assuming a birth rate of 20 and birth wastage of 10%, there were maximum of 44 pregnancies in a year and around 22 were in records at any point of time. So, to cover 150 postpartum women, a total of 10 Anganwadi centers were contacted.

Study instrument

The participants were interviewed using a pretested, semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered by a trained interviewer. The examination was carried out with due privacy by a female doctor. Sahli’s acid hematin method was used for hemoglobin estimation. It is a simple, non-time-consuming, easy to conduct, and economical method for determining hemoglobin content in blood samples.[14] The study tool was divided into sections on the sociodemographic profile of the study participants, information regarding obstetric and postnatal period, and clinical examination findings.

Operational definitions

Adequate antenatal care—At least four antenatal visits, at least one tetanus toxoid (TT) injection, and iron folic acid (IFA) tablets or syrup taken for 100 or more days.[15]

Back pain—Any complaint of back pain from delivery to 42 days postpartum.

Anemia for pregnant women: Hemoglobin ≤ 11 g/dL was defined as anemia.[16]

Urinary tract infection—Any woman complaining of burning micturition with/without fever and/or increased frequency of micturition.

Puerperal sepsis—Infection of the genital tract occurring at any time between the onset of rupture of membranes or labor, and the 42nd day postpartum in which two or more of the following are present: a) Fever (oral temperature 38.5°C/101.3°F or higher on any occasion), b) lower abdominal pain, c) abnormal vaginal discharge, e.g. the presence of pus, abnormal smell/foul odor of discharge, and/or d) subinvolution of uterus.[17]

Breast engorgement—Engorged breasts and no fever, cracked and retracted nipple leading to difficulty in breastfeeding.

Breast abscess—Redness and swelling on one part of the breast and fever (temperature > 38°C).

Ethical approval

Approval of the institutional ethical committee (IEC/2016/76-A/23) was obtained before commencing the study and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013. Prior to the interview, written informed consent was taken from each participant.

Data analysis

The information collected was kept confidential. Data entry and analysis were conducted utilizing Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Descriptive analysis was carried out followed by analytical tests using Chi-square statistics. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered significant at a 95% confidence level.

Results

The age of participants ranged from 15 to 40 years old. Three-fifths (89, 59.3%) of the study subjects were in the age group of 15–25, followed by 26 years and older (61, 40.7%). The majority of the women (138, 92.0%) were Hindus and most of them belonged to nuclear families (84, 56.0%). The majority (144, 96.0%) of the study subjects were homemakers by occupation. Less than half of the mothers were educated up to the middle school level (72, 48.0%), while the remaining had a high school and above degree (78, 52.0%). More than half (94, 62.7%) of the study participants belonged to the upper lower class (IV), followed by 56 (37.3%) who belonged to the lower middle class (III). (Modified Kuppuswamy scale 2018).

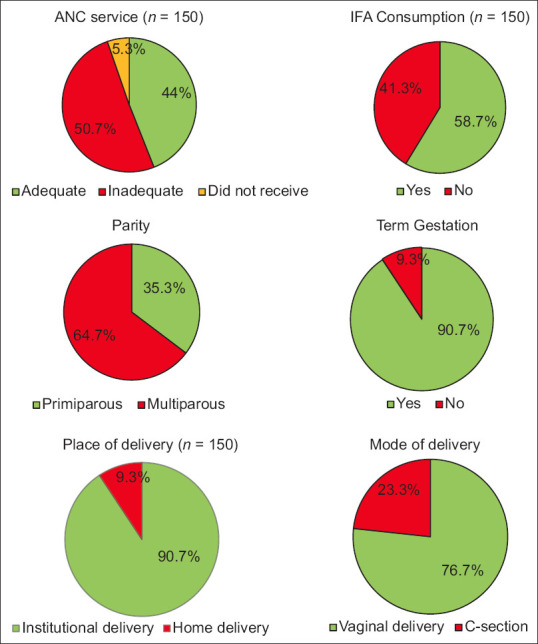

Out of 150 women, more than half of the women (84, 56.0%) had received inadequate ANC services and eight (5.3%) females did not receive it at all. Nearly three-fifths of the women (88, 58.7%) consumed iron and folic acid for 100 days during the antenatal period. The majority (97, 64.7%) were multiparous among whom 19 (19.6%) had less than three years of birth spacing. Most women (136, 90.7%) had full-term and institutional deliveries (136, 90.7%). Among the 136 women who had institutional delivery, more than two-thirds (94, 69.1%) delivered in government institutions, and an equal number (95, 69.9%) received advice regarding personal and newborn care at the time of discharge from the hospital [Figure 1]. It was also observed that almost three-fourths (115, 76.7%) of the women had a vaginal delivery and only one-fourth (35, 23.3%) had lower segment caesarean section (LSCS). Half of the women (71, 47.3%) had a hospital stay of less than 48 hours.

Figure 1.

Distribution of study subjects according to obstetric events

Nearly two-thirds (106, 70.7%) suffered from at least one postpartum morbidity, while the remaining 44 (29.3%) women did not suffer from any morbidity. The most frequently reported morbidity was anemia (83, 55.3%), followed by back pain (44, 29.3%) [Table 1]. None of the women experienced severe anemia. Fourteen women (9.3%) had puerperal infection of the genital tract and urinary tract infection was reported by 13 (8.7%) women. Problems relating to breasts (breast engorgement, breast abscess, retracted nipple, and cracked nipple) were reported by 17 women (11.3%). Of these 106 women who experienced problems in the postpartum period, almost one-third (39, 36.8%) did not seek care treatment, another third (51, 34.0%) of the women utilized allopathic treatment, followed by 16 (10.6%) women who relied on Ayurveda, homeopathy or home remedies [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of study subjects according to postpartum morbidities and care-seeking behavior (n=150)

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 83 | 55.3 |

| Back pain | 44 | 29.3 |

| UTI | 13 | 8.67 |

| Puerperal sepsis | 14 | 9.33 |

| PPH | 3 | 2.00 |

| Breast problem | 17 | 11.33 |

| Treatment sought | ||

| Yes | 67 | 44.67 |

| No | 39 | 26.00 |

| Not applicable | 44 | 29.3 |

| Type of treatment | ||

| Allopathy | 51 | 34.0 |

| Ayurveda | 5 | 3.33 |

| Homeopathy | 4 | 2.67 |

| Home remedy | 7 | 4.67 |

| No treatment | 39 | 26.0 |

| Not applicable | 44 | 29.3 |

*UTI: Urinary tract infection, PPH: postpartum hemorrhage

No association was found between postpartum morbidity and age, religion, or type of family (p value > 0.05). [Table 2] Morbidity was significantly more prevalent among lesser educated women (63, 87.5%) as compared to those with high school and above education (43, 55.1%) (Odds Ratio, OR: 5.63, 95% CI: 2.508–13.54, p = 0.000), those belonging to the lower class (75, 79.8%) as compared to the middle class (31, 55.4%) (OR: 0.317, 95% CI: 0.151–0.657, p = 0.002) and those who had received inadequate antenatal care (75, 89.3%) as compared to women who had received adequate antenatal care (31, 47.0%) (OR: 0.108, 95% CI: 0.044–0.246, p = 0.0001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association of postpartum morbidity with sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics (n=150)

| Variables | Postpartum morbidity | Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | χ 2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total | ||||

| Age (in years) | ||||||

| 15-25 | 66 (74.2) | 23 (25.8) | 89 (59.3) | 1.502 (0.733–3.078) | 1.286 | 0.258 |

| ≥26 | 40 (65.7) | 21 (34.3) | 61 (40.7) | |||

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 99 (71.7) | 39 (28.3) | 138 (92.0) | 1.805 (0.497–6.188) | 0.957 | 0.328 |

| Muslim | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 12 (8.0) | |||

| Type of family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 59 (70.2) | 25 (29.8) | 84 (56.0) | 0.954 (0.464–1.946) | 0.017 | 0.897 |

| Joint | 47 (71.2) | 19 (28.8) | 66 (44.0) | |||

| Literacy status | ||||||

| Below high school | 63 (87.5) | 9 (12.5) | 72 (48.0) | 5.63 (2.508–13.54) | 18.928 | 0.0001 |

| High school and above | 43 (55.1) | 35 (44.9) | 78 (52.0) | |||

| *SE status | ||||||

| Middle class | 31 (55.4) | 25 (44.6) | 56 (37.3) | 0.317 (0.151–0.657) | 10.104 | 0.0015 |

| Lower class | 75 (79.8) | 19 (20.2) | 94 (62.7) | |||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primiparous | 38 (71.7) | 15 (28.3) | 53 (35.3) | 1.08 (0.516–2.305) | 0.042 | 0.838 |

| Multiparous | 68 (70.1) | 29 (29.9) | 97 (64.7) | |||

| Antenatal care | ||||||

| Adequate | 31 (47.0) | 35 (53.0) | 66 (44.0) | 0.108 (0.044–0.246) | 31.928 | 0.0001 |

| Inadequate | 75 (89.3) | 9 (10.7) | 84 (56.0) | |||

| Term gestation | ||||||

| Yes | 95 (69.9) | 41 (30.1) | 136 (90.7) | 0.634 (0.136–2.272) | 0.139 | 0.708 |

| No | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | 14 (9.3) | |||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 85 (73.9) | 30 (26.1) | 115 (76.7) | 1.88 (0.835–4.181) | 2.506 | 0.114 |

| Cesarean section | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | 35 (23.3) | |||

| Place of delivery | ||||||

| Home delivery | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | 14 (9.3) | 0.725 (0.228–2.525) | 0.303 | 0.581 |

| Institutional delivery | 97 (71.3) | 39 (28.7) | 136 (90.7) | |||

*Socioeconomic status was merged into two categories middle class and lower class, statistically significant p values are shown in bold fonts

An important sociodemographic determinant of anemia was younger age less than 25 years (OR: 2.599, 95% CI: 1.332–5.14). Anemia was also associated with lower education levels (below high school) as compared to high school and above (OR = 3.603, 95% CI: 1.838–7.203, p = 0.000), lower socioeconomic class compared to middle socioeconomic class (OR: 0.247, 95% CI: 0.119–0.497, p = 0.001), women who did not consume IFA during antenatal period (43, 69.4%) compared to those who consumed (40, 45.5%) (OR: 0.371, 95% CI: 0.184–0.732, p = 0.004) and those who did not receive adequate ANC (65, 77.4%) compared to those who received ANC care (18, 27.3%) (OR: 0.112, 95% CI: 0.052–0.232, p = 0.005) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association of anemia with sociodemographic characteristics and obstetric events

| Sociodemographic | Anemia | Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | χ 2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 15-25 | 56 (62.9) | 33 (37.1) | 89 (59.3) | 2.599 (1.332–5.14) | 8.084 | 0.004 |

| ≥26 | 24 (39.3) | 37 (60.7) | 61 (40.7) | |||

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 73 (52.9) | 65 (47.1) | 138 (92.0) | 0.803 (0.223–2.723) | 0.131 | 0.717 |

| Muslim | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 12 (8.0) | |||

| Type of family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 45 (53.6) | 39 (46.4) | 84 (56.0) | 1.022 (0.533–1.959) | 0.004 | 0.947 |

| Joint | 35 (53.0) | 31 (47.0) | 66 (44.0) | |||

| Literacy status | ||||||

| Below high school | 50 (69.4) | 22 (30.6) | 72 (48.0) | 3.603 (1.838–7.203) | 14.44 | 0.0001 |

| High school and above | 30 (38.5) | 48 (61.5) | 78 (52.0) | |||

| *SE status | ||||||

| Middle class | 18 (32.1) | 38 (67.9) | 56 (37.3) | 0.247 (0.119–0.497) | 16.122 | 0.0001 |

| Lower middle class | 62 (66.0) | 32 (34.0) | 94 (62.7) | |||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primiparous | 36 (67.9) | 17 (32.1) | 53 (35.3) | 2.241 (1.116–4.597) | 5.257 | 0.022 |

| Multiparous | 47 (48.5) | 50 (51,5) | 97 (64.7) | |||

| Antenatal care** | ||||||

| Adequate | 18 (27.3) | 48 (72.7) | 66 (44.0) | 0.112 (0.052–0.232) | 37.55 | 0.0001 |

| Inadequate | 65 (77.4) | 19 (22.6) | 84 (56.0) | |||

| IFA intake | ||||||

| Yes | 40 (45.5) | 48 (54.5) | 88 (58.7) | 0.371 (0.184–0.732) | 8.407 | 0.004 |

| No | 43 (69.4) | 19 (30.6) | 62 (41.3) | |||

| Term gestation | ||||||

| Yes | 75 (55.1) | 61 (44.9) | 136 (90.7) | 0.923 (0.285–2.865) | 0.020 | 0.886 |

| No | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) | 14 (9.3) | |||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 69 (60.0) | 46 (40.0) | 115 (76.7) | 2.238 (1.033–4.946) | 4.343 | 0.037 |

| Cesarean Section | 14 (40.0) | 21 (60.0) | 35 (23.3) | |||

| Place of delivery† | ||||||

| Home delivery | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | 14 (9.3) | 5.442 (1.312–37.03) | 4.49 | 0.034 |

| Institutional delivery | 71 (52.2) | 65 (47.8) | 136 (90.7) | |||

*Socioeconomic status was merged into two categories middle class and lower middle class. †Fisher exact test, significant p values are in bold fonts

Discussion

Maternal health care is a concept that encompasses family planning, preconception, prenatal, and postnatal care. In the past, the primary emphasis has been on high-quality antenatal care. In recent years, it has been found that the postnatal period is equally important. Exploring the extent of ill-health is essential for understanding the postpartum disease burden and identifying care-seeking behavior. For optimal maternal health, timely, high-quality, postnatal care is essential. To highlight this, the following study was conducted in an urban slum to determine the extent and determinants of postpartum morbidity.

In the present study, nearly two-thirds of women suffered from at least one postpartum complication. Findings from various studies exhibit significant variations in reported maternal morbidity rates, a community-based study in Haryana reported 74% while a study in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, noted a 48.9% prevalence rate.[7,18] A study from West Ethiopia had reported a 32.8% prevalence of maternal morbidity.[19] Interestingly, a study conducted in Marrakesh, Morocco, observed a notably lower prevalence of self-reported PPM at 13.1%.[20]

The PPM prevalence identified in the current study was high. Due to women’s own perceptions and beliefs about their experiences of considering certain illnesses inherent to the delivery process, there is a risk of underreporting complaints, while an inclination to view their experiences as more severe might result in exaggerated complaints. The variability in geographical regions studied, spanning hospital-based and community-based research, may also influence the observed prevalence rates of the condition due to diverse demographic and environmental factors. Furthermore, there is no universally accepted definition of PPM, and there is a wide variation in the definitions employed in various studies. The recall period for the studies using self-reported morbidity can also influence the observed prevalence.

Contrary to our study, a significantly higher occurrence of postpartum morbidities was reported among Muslims and Christians in comparison with Hindus.[7,21] In line with the previously conducted studies, a decreasing trend in morbidity was observed with increasing socioeconomic status in our study as well.[21,22] Higher education and socioeconomic conditions can facilitate better nutrition status and prenatal care. Moreover, an educated mother has better knowledge about the importance of good nutrition and diet, which may influence the risk of the occurrence of morbidities. In contrast to previous studies that had reported higher maternal morbidities among women with higher parity, the current study found no link between parity and morbidity.[19,21]

The most frequently reported morbidity was anemia in the current study. A similar prevalence was reported by a study on secondary data related to the National Family health survey-3 (NFHS-3) which revealed a 62.9% prevalence of anemia, while another study from rural Karnataka reported a 65.8% occurrence of anemia among postpartum women.[23,24] The recently concluded NFHS-5 from 2019–21 had reported an increase in the prevalence of anemia among pregnant women aged 15–49 years in Gautam Buddha Nagar to 61.9% as compared to the 49.7% reported in the previous round in the same district (NFHS-4 during 2015–16). The current study was conducted in 2017–18 between the two rounds of NFHS and reported a 55.3% prevalence of anemia, which falls between the values reported in the two consecutive rounds of NFHS. Other reasons for the discrepancy can be the smaller sample-size and the difference is anemia estimation methodology (NFHS uses HemoCueHb201 + analyzer). These findings contrast with the varying prevalence of postpartum anemia observed across Indian states, ranging from 26.5% in coastal Karnataka to 47.3% in rural Tamil Nadu block, peaking at 76.2% in Puducherry.[25,26,27] Additionally, a prevalence of 32.7% was reported across China.[28] In the current study, the prevalence of anemia was higher when compared with reports from other parts of the country. This could be attributed to the differing cutoff points employed in various studies, potentially leading to overestimation or underestimation of the actual prevalence. Furthermore, antepartum anemia, the mother’s poor nutritional state prior to the pregnancy, as well as poor iron absorption could be contributing factors of postpartum anemia.

In consonance with our study, previous studies had also reported a higher burden of anemia among younger postnatal mothers.[24,25,26] A study in coastal Karnataka found a higher prevalence of anemia among illiterate women.[29] Inadequate iron supplementation in the postnatal phase and the presence of antenatal anemia were found to be determinants of postnatal anemia among lactating women in a study among the rural population of north Karnataka.[26] Literacy rate was one of the determinants of postnatal anemia in a study conducted in rural Karnataka while socioeconomic status did not play any role.[23] Similar to the present study, a cross-sectional study from China found no association between anemia and mode of delivery.[28] As opposed to our study, a higher prevalence of anemia was noted in multiparous mothers in the studies conducted in coastal Karnataka and Puducherry.[27,29] Anemia was more common among primiparous women in our study, which could be attributed to a lack of understanding about the importance of iron folic acid (IFA) supplements, whereas multiparous women are already aware of the importance of IFA supplements due to past pregnancy experience.

Back pain was the second most frequently reported problem in our study (29.2%). A similar finding was reported in China, where 29.6% of women reported back pain.[10] The occurrence of back pain is influenced by factors such as the nutritional status of the women and the interval between childbirths, which enables the body to restore vital nutrients like calcium.[30] Thus, spacing between deliveries supports better nutritional recovery, potentially impacting the prevalence of back pain. The persistence of back pain could be attributed to incomplete recovery of bone mineral density during the index pregnancy leading to sustained pain.

In our study, only one-third of mothers sought allopathic treatment for their morbidity from a modern medicine practitioner. A similar observation was made by another study that reported that about 55.1% of mothers took treatment for their problems.[21] The women in the study belonged to vulnerable groups with low levels of education and socioeconomic status that might influence their care-seeking behavior.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of the study is the reduced impact of recall bias. By administering the questionnaire during the postpartum period, the potential for inaccuracies stemming from reliance on memory was minimized, ensuring more reliable responses and avoiding the influence of a time lag. One of the limitations of the study was not using multivariable analysis, and finding the determinants based on univariate analysis only. The self-reported nature of the study can lead to underreporting or overreporting of symptoms, and inherent problems of social desirability bias. Another limitation of the research is the absence of an exploration into the association between antenatal and postnatal anemia. Furthermore, the use of Sahli’s method for hemoglobin estimation had its limitations, as nonhemoglobin substances like protein and lipids in plasma and cell stroma may influence the color of the blood when diluted with acid, potentially influencing the results.

Conclusion

In view of the high prevalence of postpartum morbidities in the vulnerable community as reported by the present study, there is a need for clear-cut guideline for care during the postnatal period. The role of education and literacy in the use of maternal services is evident in this study. Antenatal visits should be utilized as opportunities to increase awareness regarding various aspects of care during the postnatal period. Maintaining more comprehensive support and involvement between healthcare providers and the mothers is needed and efforts should be made to increase access to health facilities for care seeking. The study highlighted the association between inadequate antenatal care and anemia. Accessibility to healthcare services of the slum population must be considered in the health planning process by ensuring that all women receive early postpartum visits after delivery at home and after discharge from the institution to detect and manage maternal morbidity. Furthermore, the hospitals should also ensure that women are properly screened for complications before their discharge after delivery. Multicentric studies are recommended to get the true picture for the whole country and community-based studies should be conducted to examine the relationship between postpartum care seeking and other factors including education and beliefs. This will provide valuable insights into this neglected area of research, and also help to reduce the plight of millions of postpartum women suffering from avoidable morbidities.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lopez-Gonzalez DM, Kopparapu AK. Postpartum Care of the New Mother. StatPearls. 2022. [Last accessed on 2024 Apr 15]. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565875/ [PubMed]

- 2.India-Sample Registration System (SRS)-Special Bulletin On Maternal Mortality in India 2018-20. [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 28]. Available from:https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/44379 .

- 3.WHO Technical Consultation on Postpartum Care. 2010. [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 28]. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310595/

- 4.Storeng KT, Murray SF, Akoum MS, Ouattara F, Filippi V. Beyond body counts: A qualitative study of lives and loss in Burkina Faso after “near-miss”obstetric complications. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1749–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO recommendations on Postnatal care of the mother and newborn. [Last accessed on 2024 Feb 28]. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506649 .

- 6.Aziz S, Basit A, Sultana S, Homer CSE, Vogel JP. Inequalities in women's utilization of postnatal care services in Bangladesh from 2004 to 2017. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06672-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vyas N, Kamath R, Pattanshetty S, Binu VS. Postpartum related morbidities among women visiting government health facilities in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:320. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahri N, Quchan ADM, Attar F, Talasaz FH, Bahri N. Postpartum morbidities and the influential factors in Gonabad, Iran (2016) Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2018;21:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wickramasinghe ND, Horton J, Darshika I, Galgamuwa KD, Ranasinghe WP, Agampodi TC, et al. Productivity cost due to postpartum ill health: A cross-sectional study in Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao L, Ma L, Liu N, Chen B, Lu Q, Ying C, et al. Self-reported health problems related to traditional dietary practices in postpartum women from urban, suburban and rural areas of Hubei province, China: The “zuòyuèzi.”. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25:158–64. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2016.25.2.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firoz T, Chou D, von Dadelszen P, Agrawal P, Vanderkruik R, Tunçalp O, et al. Measuring maternal health: Focus on maternal morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:794–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.117564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bang RA, Bang AT, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB, Filippi V. Maternal morbidity during labour and the puerperium in rural homes and the need for medical attention: A prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. BJOG. 2004;111:231–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alstead S. Observations on Sahli's Haemoglobinometer. Postgrad Med J. 1940;16:278. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.16.178.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponna SN, Upadrasta VP, Geddam JJB, Dudala SR, Sadasivuni R, Bathina H. Regional variation in utilization of Antenatal care services in the state of Andhra Pradesh. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6:231. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.220024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. [Last accessed on 2023 Nov 24]. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1 .

- 17.Van Dillen J, Zwart J, Schutte J, Van Roosmalen J. Maternal sepsis: Epidemiology, etiology and outcome. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:249–54. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328339257c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patra S, Singh B, Reddaiah VP. Maternal morbidity during postpartum period in a village of north India: A prospective study. Trop Doct. 2008;38:204–8. doi: 10.1258/td.2008.070417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talie A, Yekoye A, Alemu M, Temesgen B, Aschale Y. Magnitude and associated factors of postpartum morbidity in public health institutions of Debre Markos town, North West Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2018;4:19. doi: 10.1186/s40748-018-0086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottoman AW, Angira C, Owenga J, Ogendi J. Health systems determinants of occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage among women of reproductive age 15-49 years-Kenya. Int J Soc Sci Res. 2021;9:8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh A, Kumar A. Factors associated with seeking treatment for postpartum morbidities in rural India. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014026. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abate T, Kebede B, Feleke A, Misganaw E, Rogers N. Prospective Study on Birth Outcome and Prevalence of Postpartum Morbidity among Pregnant Women Who Attended for Antenatal Care in Gondar Town, North West Ethiopia. Andrology. 2014;3:125. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patil SD, Bhovi RA. Prevalence of anaemia in pregnant and lactating women in rural Vijayapur. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2020;7:224–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siddiqui MZ, Goli S, Reja T, Doshi R, Chakravorty S, Tiwari C, et al. Prevalence of anemia and its determinants among pregnant, lactating, and nonpregnant nonlactating women in India. Sage Open. 2017;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mremi A, Rwenyagila D, Mlay J. Prevalence of post-partum anemia and associated factors among women attending public primary health care facilities: An institutional based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0263501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakesh PS, Gopichandran V, Jamkhandi D, Manjunath K, George K, Prasad J. Determinants of postpartum anemia among women from a rural population in southern India. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:395. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S58355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selvaraj R, Ramakrishnan J, Sahu SK, Kar SS, Laksham KB, Premarajan KC, et al. High prevalence of anemia among postnatal mothers in Urban Puducherry: A community-based study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2703. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_386_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao A, Zhang J, Wu W, Wang P, Zhan Y. Postpartum anemia is a neglected public health issue in China: A cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019;28:793–9. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.201912_28(4).0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhagwan D, Kumar A, Rao CR, Kamath A. Prevalence of Anaemia among Postnatal Mothers in Coastal Karnataka. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:LC17. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/14534.7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To WWK, Wong MWN. Persistence of back pain symptoms after pregnancy and bone mineral density changes as measured by quantitative ultrasound--A two year longitudinal follow up study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]