Abstract

Antibiotic resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an urgent threat to human health. The biofilm and persister cells formation ability of MRSA and Staphylococcus epidermidis often companied with extremely high antimicrobial resistance. Pinaverium bromide (PVB) is an antispasmodic compound mainly used for irritable bowel syndrome. Here we demonstrate that PVB could rapidly kill MRSA and S. epidermidis planktonic cells and persister cells avoiding resistance occurrence. Moreover, by crystal violet staining, viable cells counting and SYTO9/PI staining, PVB exhibited strong biofilm inhibition and eradication activities on the 96-well plates, glass surface or titanium discs. And the synergistic antimicrobial effects were observed between PVB and conventional antibiotics (ampicillin, oxacillin, and cefazolin). Mechanism study demonstrated the antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects by PVB were mainly mediated by proton motive force disrupting as well as reactive oxygen species inducing. Although, relatively poor pharmacokinetics were observed by systemic use, PVB could significantly reduce the viable bacterial cell loads and inflammatory infiltration in abscess in vivo caused by the biofilm forming strain ATCC 43,300. In all, our results indicated that PVB could be an alternative antimicrobial reagent for the treatment of MRSA, S. epidermidis and its biofilm related skin and soft tissue infections.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13568-024-01809-x.

Keywords: Staphylococcus, Biofilm, Persister, Drug repurposing, Proton motive force

Key points

Pinaverium bromide (PVB) exhibited strong antimicrobial effects against Staphylococcus planktonic cells.

Significant biofilm inhibitory and eradicating activities by PVB.

Proton motive force disrupting and reactive oxygen species inducing are the main antimicrobial and antibiofilm mechanisms.

PVB reduce the viable bacterial cell loads and inflammatory infiltration in vivo.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13568-024-01809-x.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a common pathogen of hospital- and community-acquired infections, which can cause skin tissue infections, infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, bacteremia, and other diseases (Lowy 1998). S. aureus was first discovered in 1880 by a Scottish surgeon on ulcer patients. Two years after the emergence of antibiotics, S. aureus developed resistance, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) accounting for 25–50% of hospital acquired S. aureus infections (Diekema et al. 2001). Up to now, S. aureus has become the dominant pathogen in hospital infections in multiple countries. According to data collected by the US National Healthcare Security Network from approximately 2,000 hospitals, the infection rate of MRSA ranges from 43 to 58% (Sievert et al. 2013). According to a survey by the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention, S. aureus has become the second most common hospital acquired pathogen after Escherichia coli (Abdulgader et al. 2015).

As major human and animal pathogens, S. aureus and S. epidermidis can attach to medical implants, such as titanium (Ti) surface, or host tissue, and further establish a biofilm to enhance its resistance to antibiotics and host (Buttner et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2024). The formation of biofilms can lead to serious infections in the human body. Biofilm is formed through the aggregation of bacterial species and brings many complications. It mediates drug resistance and persistence, and promotes the recurrence of infection (Nasser et al. 2022). In addition, both of S. aureus and S. epidermidis can form persister cells (Conlon 2014; Yang et al. 2015). Persister cells are populations of dormant cells highly tolerant to antibiotics and occurred at a high frequency under growth-limiting conditions or biofilms. The persister cells creation mechanisms mainly include metabolism alterations, response to changing environmental, and gene regulators changes. For example, the intracellular ATP reduction or deficiency in electron transport chain could lead to the formation of persister cells. Agr, RsaA, MgrA and SaeRS system could also enhance persister cells formation by biofilm regulation (Chang et al. 2020). Studies widely reported the role of persister cells in chronic and relapsing infectious diseases (Conlon 2014).

The proton motive force (PMF) is an electrochemical gradient on both sides of a bacterial cell membrane that drives many basic bacterial physiological processes, including biofilm formation, ATP synthesis, nutrient uptake, and waste excretion. Antimicrobial agents that interfere with PMF affect bacterial physiology through damage to proton pump function (Formicki et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2023). For example, dehydroacetic acid chloride exhibits its antimicrobial effects by destroying the function of bacterial proton pumps, making protons unable to efficiently transport on either side of bacterial cell membranes. This interference disrupts the internal and external electrochemical gradients of the bacteria, affecting their energy metabolism and nutrient uptake. Due to the impaired function of the proton pump, the bacteria cannot maintain the required PMF, which leads to the growth of the bacteria is blocked or even death (Formicki et al. 2019). Antimicrobial drugs targeting PMF can effectively disrupt energy metabolism and other key physiological processes of bacteria through the above mechanisms, providing a new avenue for antimicrobial therapy, especially in the context of the increasing prevalence of biofilms and drug-resistant strains. It also demonstrates the potential and importance of targeting PMF in antimicrobial and antibiofilm drug development (Ikonomidis et al. 2008).

Pinaverium bromide (PVB) is a L-type calcium channel antagonist with highly selective affinity in the gastrointestinal tract. It works by inhibiting calcium ions flowing into smooth muscle cells of splanchnic muscle and preventing form the muscle over-contracting (Alhadidi et al. 2020; Christen 1990). PVB is mainly used for the treatment of abdominal pain, biliary tract dysfunction and irritable bowel syndrome (Guslandi 1994; Wall et al. 2014). However, the antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects, metabolic stability, in vivo antimicrobial efficacy and toxicity, and its underlying mechanisms by PVB against S. aureus and S. epidermidis were rarely reported.

In this study, the anti-planktonic cells and antibiofilm effects on polypropylene surface/glass/Ti-discs by PVB were detected, and the drug combinational activity between PVB and conventional antibiotics were determined by checkerboard dilution assay and time-killing assay. Meanwhile, the in vitro metabolic stability was assessed by plasma protein binding rate detection, liver microsome stability analysis, CYP450 catalytic activity assay as well as pharmacokinetic analysis. Mechanism study indicated that PVB exerted antimicrobial activity by PMF disruption and reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction. In addition, the in vivo antimicrobial efficacy of PVB was assessed in an abscess infection model. Our findings provide the insight that PVB, alone or in combination with conventional antibiotics, may be an alternative for the treatment of the infectious diseases caused by Staphylococcus and its biofilms or persister cells.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, culture conditions and reagents

S. aureus strains of Newman, MRSA USA300, and ATCC 43,300, Acinetobacter baumannii AB1069 and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains of KPLUO and KPWANG were a kind gift from Li Min at Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. S. epidermidis RP62A and ATCC 12,228 were kindly provided by Qu Di at Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. Escherichia coli Y9592 was donated by Chen Cha at Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. LZB1 was collected from the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (She et al. 2020). Other type strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). S. aureus and S. epidermidis were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Solarbio, Shanghai, China). Gram-negative bacteria and Candida strains were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) broth (TSB, Solarbio, Shanghai, China) and RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7·0 ± 0·1), respectively. PVB and other antibiotics were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or distilled water as storage solutions.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

The antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) (CLSI 2023), the antibacterial effects of the compounds were evaluated by the standard microdilution broth assay. At first, log-phase bacteria were diluted to a final concentration of approximately 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL with Mueller-Hinton (MH) II broth. These were then mixed with an equal volume of serial dilution compounds in a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 16–18 h, the optical density (OD) value at 630 nm was determined. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration that inhibited visible bacterial growth. Subsequently, the samples used for MIC determination were inoculated onto blood agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was defined as the lowest concentration that eradicated 99% of bacteria in the initial inoculum.

Bactericidal kinetics

Overnight cultures of S. aureus and S. epidermidis were diluted to 1 × 106 CFU/mL with TSB and incubated at 37 °C and 180 rpm in the presence or absence of serial concentrations of PVB. The colony forming unit (CFU) counts of the cultures were determined at time points of 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, respectively. Briefly, an aliquot of the bacterial suspension in each group was serially diluted with saline, and spotted onto sheep blood agar. After incubated at 37°C for 24 h, the colonies on the agars were counted (Li et al. 2017).

Bacterial resistance inducing assay

Firstly, the MICs of PVB and ciprofloxacin (CIP, positive control) against S. aureus and S. epidermidis were determined on the first day. After incubation at 37 °C for 16–18 h, 50 µL of the bacterial suspension at the 1/2× MIC were 1,000-fold diluted with fresh MH broth. Then, 50 µL of the diluted suspension and equal volume of serially diluted PVB were added to a 96-well plate. The MICs were determined after 24 h of incubation. This process was repeated continuously for 15 days (Martin et al. 2020).

Antibiofilm effects of PVB in 96-well cell culture plate

TSBg (TSB with 0.2% glucose) culture medium was used for the biofilm related assays. For biofilm inhibition assay, 100 µL of serially diluted PVB with equal volume of 1: 200 diluted overnight cultured S. aureus ATCC 43,300 were added into a 96-well cell culture plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the plate was washed by 1×PBS, and the biofilms were quantified by crystal violet staining and CFU counting, respectively. Briefly, for crystal violet staining, the plate was added with 200 µL of 0.25% (w/v) crystal violet. After incubation for 15 min, the excess dye was removed and washed by 1×PBS. Then, the adhered dye was dissolved in 95% ethanol for 30 min, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured. For CFU counting assay, the biofilms were resuspended in 200 µL of 1×PBS, sonicated for 15 min and serially diluted with 1×PBS. The diluted bacterial suspension was then spotted on sheep blood agar plates, and the CFUs were counted after overnight cultured at 37 °C.

For biofilm eradication assay, overnight cultured S. aureus was 1: 200 diluted with TSBg, and 200 µL of the bacterial suspension was added into each well in a 96-well cell culture plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the wells were rinsed twice with 1×PBS, and added with indicated concentrations of PVB. After incubation for further 24 h, the biofilm was washed again and quantified by crystal violet staining and CFU counting, respectively, as described above (Kazmierczak et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2021).

Biofilm observation by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LCSM)

For biofilm formation inhibition, the bacteria overnight cultured were 1: 200 diluted with TSBg medium, then 2 mL of the bacterial suspension in the presence or absence of PVB was transferred into a 6-well cell culture plate with a glass cover slide in each well. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the cover slides were gently washed twice with saline and stained with 10 µM SYTO9/PI for 15 min in the dark. Then, the excess dye was removed by 1×PBS washing, and the biofilms were observed with a LCSM (Zeiss LSM800, Jena, Germany). The excitation and emission wavelengths for SYTO9 and PI were 485 nm/530 nm and 485/630 nm, respectively.

For biofilm eradication, the biofilms were formed on the cover slide with TSBg medium for 24 h, then, washed and treated with indicated concentrations of PVB. After further incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the cover slides were washed, stained with SYTO9/PI and observed by the LCSM as described above (Liu et al. 2015).

Biofilm inhibition on Ti-discs

Overnight cultures of S. aureus or S. epidermidis were diluted 1: 200 in fresh TSBg with or without PVB at concentrations ranging from 4 to 64 µg/mL. DMSO was used as a control. Then, 2 mL of the bacterial suspension was added in a 6-well cell culture plate in the presence of a Ti-disc in each well. Following static incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the Ti-discs were washed by transferring to a new plate containing sterile saline. For viable cells counting, the biofilms on the discs were dispersed in 2 mL of saline by sonication for 15 min, then serially diluted and spotted on sheep blood agar. After overnight incubation, the colonies on the agar were counted. For crystal violet staining, the discs were stained with 0.25% (w/v) crystal violet for 15 min. The discs were washed again and solubilized with 95% ethanol for 30 min, and the total biofilm biomass was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm (A570).

Biofilm eradication on Ti-discs

The 24-hour biofilms on the Ti-discs were formed in TSBg as described above. After washed with saline, the discs were treated with 2 mL of TSBg in the presence or absence of PVB ranging from 4 to 64 µg/mL. After further incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the remaining biofilm was washed and quantified either by CFU counting or crystal violet staining as described above (Gomes et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2018).

Persister cells killing assay

The S. aureus and S. epidermidis persister cells were obtained by incubation at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 24 h to the stationary phase in TSB. The persister cells were washed three times with 1× PBS (pH = 7.4) and then adjusted to approximately OD630nm = 0.2. Then, the persister cells were treated with 64 µg/mL of vancomycin (VAN) or indicated concentrations of PVB, respectively. The CFU counts were performed at the time point of 0, 2, and 4 h, respectively. DMSO (1%, vol/vol) was utilized as a control (Kim et al. 2018).

Checkerboard dilution assay

The effects of PVB in combination with conventional antibiotics were assessed by checkerboard dilution assay. Briefly, log-phased S. aureus ATCC 43300 was diluted with MH broth to 1 × 106 CFU/mL. Equal volumes of serially diluted PVB and antibiotics in the presence of the bacterial suspensions were added into the rows and columns of an “8 × 8” checkerboard in a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37°C for 16–18 h, the MICs were determined and the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) values were calculated as follows:

|

Synergistic effect was defined as FICI ≤ 0.5; additive effect was defined as 0.5 < FICI ≤ 1; indifference effect was defined as 1 < FICI ≤ 4; antagonism effect was defined as FICI > 4 (Dupieux et al., 2017).

Ultrastructure observation by electronic microscopy

S. aureus ATCC 43,300 overnight cultures were sub-cultured with TSB to log phase. The bacterial suspension was then washed twice with 1×PBS (pH = 7.4) and adjusted to 0.5 McF with TSB medium containing 5×MIC of PVB or 0.1% DMSO (control). After incubation at 37°C and 180 rpm for 1 h, the bacterial suspensions were further washed with 1×PBS and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 8 min. The cell pellets were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Solarbio, Shanghai, China) and stored at 4°C overnight. For scanning electronic microscopy (SEM), after removing the fixative with 1×PBS, the bacteria pellets were dehydrated using a series of ethanol concentrations (25, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100%). Then, the dried samples were covered with gold palladium and observed by a SEM (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). For transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) observation, the bacteria were dehydrated and infiltrated in epoxy resin. Two days later, the materials were cut into the ultrathin sections and counterstained with lead citrate solution. Finally, the samples were observed by a TEM (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) (Pengfei et al. 2022).

Erythrocytes hemolysis assay

Human erythrocytes (Hemo Pharmaceutical & Biological Co. Shanghai, China) were washed three times with 1×PBS (pH = 7.4) and resuspended to the concentration of 10% (v/v). Then, the cells were exposed to equal volumes of PVB at the indicated concentrations and incubated statically at 37 °C for 1 h. The negative and positive controls were prepared by using 0.1% DMSO and 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively. After incubation, 100 µL of supernatant was transferred to a new 96-well plate and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm. The rate of hemolysis was calculated using the following formula (Tan et al. 2020):

|

Antimicrobial effects of PVB in the presence of L-Glutathione (GSH) or anaerobic condition

To explore the role of ROS on the antimicrobial ability by PVB, the MIC of PVB against MRSA ATCC 43,300 was determined as described above in the presence of 10 mM reduced GSH (a ROS scavenger). Further, the MIC was also detected in the anaerobic condition by using AnaeroGen anaerobic system envelopes (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Cytotoxicity determination by CCK-8 kit

The cells of LO2 and HepG2 were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. One hundred microliters of logarithmic phased cells were seeded into a 96-well cell culture plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. After incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, a indicated concentrations of PVB was added to each well. The cells treated with 0.1% DMSO were set as a control. After incubation for 24 h, 10 µL of CCK-8 solution were added to each well, and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The cell viability was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm (A450) (Liu et al. 2015).

Apoptosis determination by flow cytometer

Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry with Annexin APC/PI kit. Briefly, the cells were prepared as described above, and then digested with trypsin. After centrifuged and washed twice with 1×PBS, the cells were resuspended in 1×PBS with Annexin APC/PI. After incubation in the dark for 10 min, the cells were analyzed by a flow cytometry (BD, USA) (Liu et al. 2015).

Transmembrane potential detection by DiSC3(5) probe

The mid-log phase S. aureus strains were adjusted to an OD630nm of 0.2 in HEPES buffer in the presence of 5 mM glucose and 100 mM KCl. DiSC3(5) (MedChem Express, New Jersey, USA) was added to the bacterial suspension to a final concentration of 2 µM. Following the gently mixing of the DiSC3(5)-labelled bacteria with indicated concentrations of PVB, the fluorescence intensity was measured at the excitation/emission wavelengths of 622 nm/670 nm, respectively, after incubation for 30 s. Melittin (2 µg/mL) and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (Liu et al. 2022).

Transmembrane proton concentration detection by BCECF-AM probe

The S. aureus strains were grown in TSB to a mid-log phase. Then the bacteria were washed and resuspended in 5 mL of HEPES buffer in the presence of 10 µM of BCECF-AM (MedChem Express, New Jersey, USA). After incubation in the dark for 30 min, the bacteria were treated with indicated concentrations of PVB. Melittin (2 µg/mL) and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The fluorescence intensities were monitored at an interval of 5 min with the excitation/emission wavelength of 500 nm/522 nm, respectively (Liu et al. 2020).

Intracellular ROS quantification by 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe

The mid-log phased S. aureus strains were adjusted to OD630nm = 0.5 with 1×PBS. And the bacterial suspension was incubated with 10 µM of DCFH-DA (MedChem Express, New Jersey, USA) for 30 min in the dark. Then, 90 µL of the labeled bacterial suspension with 10 µL of indicated concentrations of PVB were added to a black 96-well plate. After incubation for 30 min, the fluorescence was observed by the LCSM, and the intensities were quantified by measured at the excitation/emission wavelength of 488 and 525 nm, respectively (Song et al. 2020).

ROS components determination

Intracellular ROS is mainly comprised of specific reactive species, including superoxide (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH). These can be evaluated by using the fluorescence probes of HKSOX-1, HKperox-2, and HKOH-1r (MedChem Express, New Jersey, USA), respectively. Briefly, the log-phased bacterial suspension was adjusted to OD630nm = 0.5 in the presence of 10 µM specific probes in 1×PBS. After incubation for 30 min in the dark, the bacteria suspension was mixed with indicated concentrations of PVB and further incubated for 30 min. Melittin (2 µg/mL) and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The fluorescence intensities were monitored at the excitation/emission wavelength of 500/520 nm, 520/543 nm, and 500/520 nm for HKSOX-1, HKperox-2, and HKOH-1r, respectively (She et al. 2023).

The in vivo mice models and other methods were shown in the Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative measurments were performed in triplicate. The data were processed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (Software Inc., CA, USA). Student’s t-test was applied for comparison between two independent groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for comparison between multiple groups. Statistical significance was considered with P < 0.05.

Results

Bactericidal activity of PVB against S. aureus and S. epidermidis without resistance occurrence

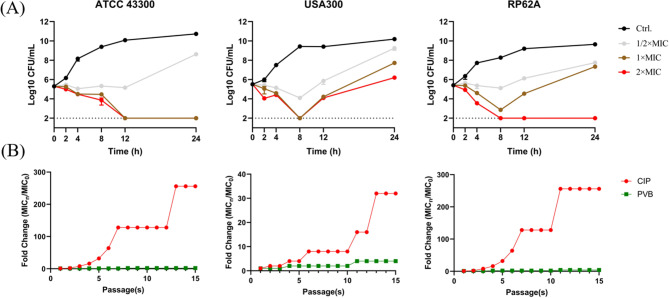

By micro-dilution assay, PVB was found to be effective against S. aureus and S. epidermidis with the MIC and MBC values of 8–16 µg/mL and 16–64 µg/mL, respectively. However, extremely low or none antimicrobial activity was observed by PVB against Gram-negative pathogens or fungi (Table 1). Meanwhile, PVB showed time- and concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against S. aureus and S. epidermidis. As shown in Fig. 1A/2×MIC of PVB could effectively inhibit the bacterial growth, and 1–2×MIC of PVB significantly reduce the viable cell counts to the limit of detection. Noticeably, a rebound of the CFU count was found by USA300 after 8 h of treatment with 1–2×MIC of PVB, the widely reported phenomenon could be probably due to the depletion of the antimicrobial agent, the limitation of detection limit, or/and the resistance occurrence (Li et al. 2023). In addition, by consecutive inducing in the presence of sub-MIC of PVB for a total of 15 passages, almost none or extremely low resistance was occurred by S. aureus or S. epidermidis (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of PVB against pathogens

| Strains | Resistance pattern | PVB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) | ||

| S. aureus | |||

| ATCC 29,213 | MSSA | 8 | 64 |

| ATCC 25,923 | MSSA | 8 | 16 |

| Newman | MSSA | 8 | 16 |

| ATCC 43,300 | MRSA | 16 | 16 |

| USA300 | MRSA | 8 | 64 |

| LZB1 | MSSA, BFP | 8 | 32 |

| S. epidermidis | |||

| RP62A | MSSE, BFP | 8 | 16 |

| ATCC 12,228 | MSSE, BFN | 8 | 16 |

| E. coli | |||

| ATCC 25,922 | Non-MDR | 128 | 256 |

| Y9592 | XDR | 128 | 128 |

| K. pneumoniae | |||

| ATCC 700,603 | Non-MDR | > 256 | > 256 |

| ATCC 4352 | Non-MDR | 32 | 64 |

| KPLUO | XDR | 256 | 256 |

| KPWANG | XDR | 256 | 256 |

| A. baumannii | |||

| ATCC 19,606 | Non-MDR | 256 | 256 |

| AB1069 | XDR | > 256 | > 256 |

| P. aeruginosa | |||

| PAO1 | Non-MDR, BFP | 256 | > 256 |

| C. albicans | |||

| ATCC 14,053 | Non-MDR | 128 | > 256 |

| C. parapsilosis | |||

| ATCC 22,019 | Non-MDR | 128 | > 256 |

BFP: biofilm formation positive; BFN: biofilm formation negative

Fig. 1.

Effective bactericidal activity of PVB against Staphylococcus avoiding resistance occurrence. (A) Bacterial killing dynamics of PVB against MRSA ATCC 43,300/USA300 and S. epidermidis RP62A. (B) Resistance inducing ability of PVB against MRSA and S. epidermidis. CIP was used as a positive control

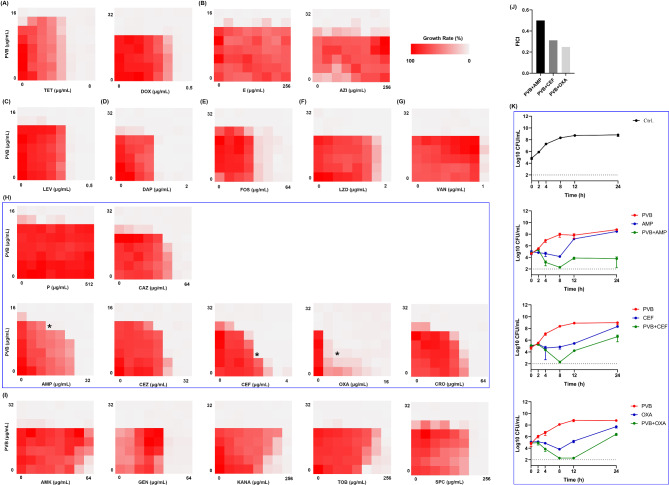

Next the synergistical antimicrobial effects were screened between PVB and conventional antibiotics by checkerboard dilution assay. As shown in Fig. 2A and I; Table 2, AMP, CEF, and OXA were exhibited synergy when combined with PVB with the FICI values of 0.5, 0.313, and 0.25, respectively (Fig. 2J). The time-killing assay further exhibited the synergistical bactericidal activity between 1/4×MIC of PVB and 1/4×MIC of AMP/CEF/OXA (Fig. 2K).

Fig. 2.

Combinational antimicrobial effects between PVB and conventional antibiotics against MRSA ATCC 43,300. Drug combinational activity between PVB and (A) tetracyclines, (B) macrolides, (C) levofloxacin (LEV), (D) daptomycin (DAP), (E) fosfomycin (FOS), (F) linezolid (LZD), (G) vancomycin (VAN), (H) β-lactams, and (I) aminoglycosides, respectively. (J) FICI values of the synergistical combinations. (K) Bacterial killing dynamics of the synergistical combinations. PVB and the conventional antibiotics were used at the concentration of 1/4×MIC. TET, tetracycline. DOX, doxycycline. E, erythromycin. AZI, azithromycin. P, penicillin. CAZ, ceftazidime. AMP, ampicillin. CEZ, cefazolin. CEF, cefotaxime. OXA, oxacillin. CRO, ceftriaxone. AMK, amikacin. GEN, gentamycin, KANA, kanamycin. TOB, tobramycin. SPC, spectinomycin

Table 2.

Combinational antimicrobial effects between PVB and conventional antibiotics

| Groups | Drugs | MICalone | MICcombined | Fold change | FICI | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PVB | 8 | 16 | 2 | 3 | indifference |

| TET | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 2 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| DOX | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | |||

| 3 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| E | > 256 | > 256 | 1 | |||

| 4 | PVB | 16 | 16 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| AZI | > 256 | > 256 | 1 | |||

| 5 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| LEV | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | |||

| 6 | PVB | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 1 | additive |

| DAP | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |||

| 7 | PVB | 16 | 16 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| FOS | 32 | 32 | 1 | |||

| 8 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| LZD | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 9 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| VAN | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 10 | PVB | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 1.5 | indifference |

| P | > 256 | > 256 | 1 | |||

| 11 | PVB | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.75 | additive |

| CAZ | 32 | 8 | 0.25 | |||

| 12 | PVB | 16 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | synergy |

| AMP | 16 | 4 | 0.25 | |||

| 13 | PVB | 8 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.5625 | additive |

| CEZ | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | |||

| 14 | PVB | 16 | 1 | 0.0625 | 0.3125 | synergy |

| CEF | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |||

| 15 | PVB | 8 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | synergy |

| OXA | 16 | 2 | 0.125 | |||

| 16 | PVB | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5625 | additive |

| CRO | 32 | 2 | 0.0625 | |||

| 17 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | > 2 | indifference/antagonism |

| AMK | 64 | > 64 | > 1 | |||

| 18 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| GEN | 16 | 16 | 1 | |||

| 19 | PVB | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 4.5 | antagonism |

| KANA | 256 | 1024 | 4 | |||

| 20 | PVB | 8 | 8 | 1 | 5 | antagonism |

| TOB | 64 | 256 | 4 | |||

| 21 | PVB | 16 | 16 | 1 | 2 | indifference |

| SPC | 128 | 128 | 1 |

A synergistic effect was defined as FICI ≤ 0.5; an additive effect was defined as 0.5 < FICI ≤ 1; an indifference effect was defined as 1 < FICI ≤ 4; an antagonism effect was defined as FICI > 4

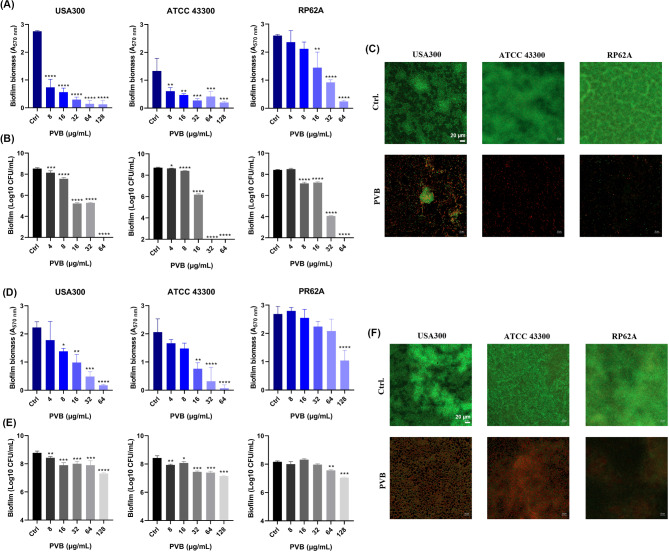

Effective antibiofilm and anti-persister cells activity by PVB

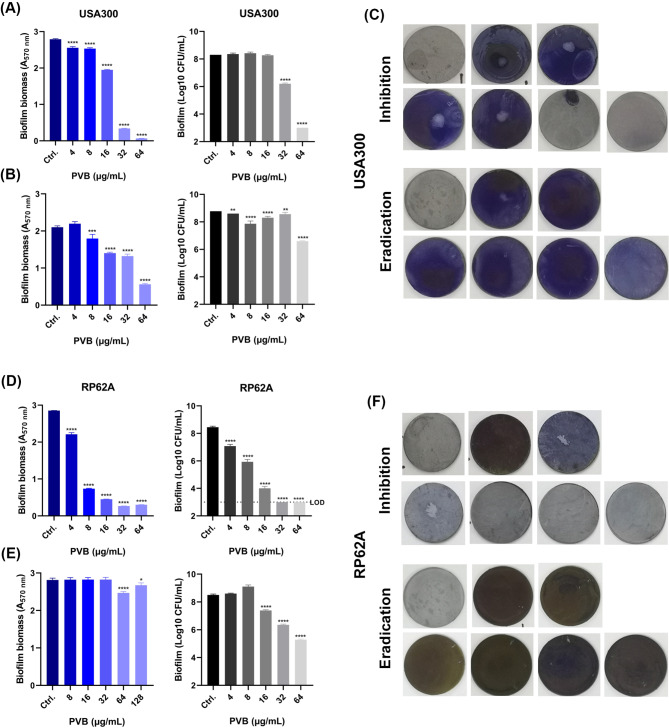

PVB was found to inhibit the biofilm formation on polypropylene 96-well plate (include the total biofilm biomass and viable bacterial cells in the biofilms) of MRSA USA300 and ATCC 43,300 as well as S. epidermidis RP62A at the concentration of around 1×MIC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A and B). And the effective biofilm inhibitory effects by 1×MIC of PVB against the Staphylococcus on glass cover slides were also observed by LCSM with the reduced biofilm biomass and increased proportion of PI-stained (impaired or dead) cells (Fig. 3C). Although, as reported widely, the pre-formed biofilm exhibited higher antibiotic resistance than its related planktonic cells (Mah 2012), PVB also showed effective antimicrobial activity against the pre-formed biofilms (include the total biofilm biomass and viable bacterial cells in the biofilms) of the MRSA and S. epidermidis. As we expected, the pre-formed biofilm eradication activity by PVB was, to some extent, slightly inferior than that of the biofilm inhibition (Fig. 3D and E). And the LCSM also exhibited the effective biofilm eradication effects by 16 µg/mL and 128 µg/mL of PVB against S. aureus and S. epidermidis, respectively (Fig. 3F). In addition, PVB was also found to inhibit the biofilm formation or eradicate the pre-formed biofilms against USA300 and RP62A on Ti-discs. As shown in Fig. 4A C, 4 µg/mL of PVB started to inhibit the biofilm formation of USA300 on Ti-discs by crystal violet staining, and 32 µg/mL of PVB could significantly reduce the viable cell counts in the biofilms. While, 8 µg/mL of PVB showed effective biofilm eradication activity against the pre-formed biofilms, and 64 µg/mL PVB could largely decrease the total viable cells in the biofilms (Fig. 4B and C). Similarly, PVB also exhibited effective biofilm inhibitory (Fig. 4D and F) and eradicating (Fig. 4E and F) effects against S. epidermidis RP62A on Ti-discs.

Fig. 3.

Antibiofilm activity by PVB. (A) Biofilm inhibition activity of PVB determined by crystal violet staining. (B) Biofilm inhibition activity of PVB determined by CFU counting. (C) Biofilm inhibition activity of PVB observed by LCSM. (D) Biofilm eradication activity of PVB determined by crystal violet staining. (E) Biofilm eradication activity of PVB determined by CFU counting. (F) Biofilm eradication activity of PVB observed by LCSM. SYTO9 and PI were used for the live and dead bacterial cells tracing, respectively. Scale: 20 μm

Fig. 4.

Antibiofilm effects of PVB against MRSA and S. epidermidis on Ti-discs. (A-B) Biofilm inhibitory (A) and eradicating (B) activity of PVB against USA300 determined by crystal violet staining and CFU counting, respectively. (C) Representative images of inhibition and eradication effects of PVB against USA300 biofilms on Ti-discs determined by crystal violet staining. (D-E) Biofilm inhibitory (D) and eradicating (E) activity of PVB against USA300 determined by crystal violet staining and CFU counting, respectively. (F) Representative images of inhibition and eradication effects of PVB against RP62A biofilms on Ti-discs determined by crystal violet staining

In addition, PVB also exhibited bactericidal activity against MRSA and S. epidermidis persister cells. The persister cells were formed by overnight culture in TSB at 37°C to stationary phase. As shown in Figure S1, all the persister cells were resistant to high concentration (64 µg/mL) of VAN. However, 1–4×MIC of PVB could effectively kill the persister cells in a concentration-dependent manner within 4 h.

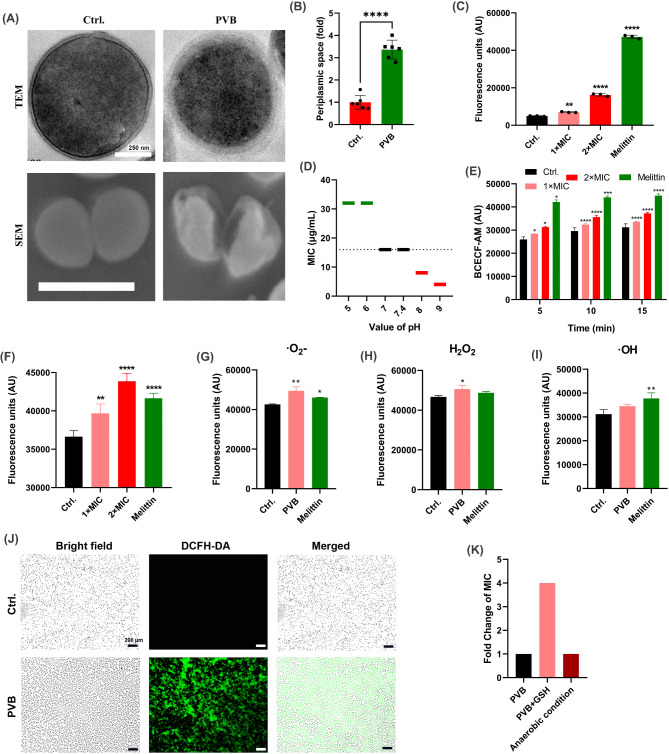

Model of action

The microstructure of PVB-treated S. aureus cells was observed by TME and SEM, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the periplasmic space was significantly increased, and some of the bacterial cells were shrunk or broken after treated with PVB. Thus, we supposed that there could be osmotic pressure imbalance between the inner and outer membranes which could be probably due to the disruption of PMF. And the PMF was also an important factor for the ATP synthesis, and the ATP is vital for the maintenance of bacteria normal morphology (Yang et al. 2023). Meanwhile, PVB was found to significantly increase the fluorescence intensity of DiSC3(5) probe, which indicated the disruption of transmembrane potential, a component of PMF (Fig. 5C). Further, the PVB exhibited varied antimicrobial ability in the presence of different proton concentrations (Fig. 5D). As the transmembrane proton concentration was also the main component of the PMF, thus, PVB could probably also disrupt the transmembrane ΔpH balance. In addition, as we expected, PVB could effectively increase the fluorescent intensity of the intracellular pH indicator BCECF-AM probe (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

PMF disruption and ROS inducing activities by PVB. (A) Microstructure observation of MRSA ATCC 43,300 by TEM and SEM, respectively. The bacterial cells were treated with 5×MIC of PVB for 1 h. The representative images were selected randomly. Scale: 250 nm for TEM and 1 μm for SEM. (B) Relative periplasmic space quantification of the S. aureus determined by the SEM. (C) Fluorescence unit quantification of DiSC3(5) probe after treated with PVB for 30 s. Melittin (2 µg/mL) was used as control. (D) MIC changes of PVB against MRSA ATCC 43,300 in the presence of varied proton concentrations. (E) PMF determination by BCECF-AM probe after treated with PVB for indicated time. Melittin (2 µg/mL) was used as control. (F-I) ROS (F) and its components of O2- (G), H2O2 (H), and OH (I) quantification after treated with 1×MIC of PVB for 30 min. (J) ROS tracing by DCFH-DA probe after treated with 1×MIC of PVB for 30 min. (K) Fold change of MIC values in the presence of GSH or anaerobic condition

As PMF was the driving force for ATP synthesis, the disruption of PMF could probably induce the electron transfer chain rearrangement. By using DCFH-DA probe, we found that PVB could significantly induce the ROS production (Fig. 5F). With in-depth analysis, the components of the increased ROS mainly included the ‧O2- (Fig. 5G) and H2O2 (Fig. 5H), although no significantly ‧OH production enhancement was observed (Fig. 5I). And the increased ROS production was also observed by LCSM tracing with DCFH-DA probe (Fig. 5J). The MIC value of PVB against MRSA ATCC 43,300 was 4-fold increased in the presence of GSH, a ROS scavenger, which indicated the important role of ROS in the antimicrobial effects by PVB (Fig. 5K). However, the MIC of PVB remained unchanged in anaerobic condition (Fig. 5K), which was because that there could be alternative antimicrobial mechanism by PVB in anaerobic condition.

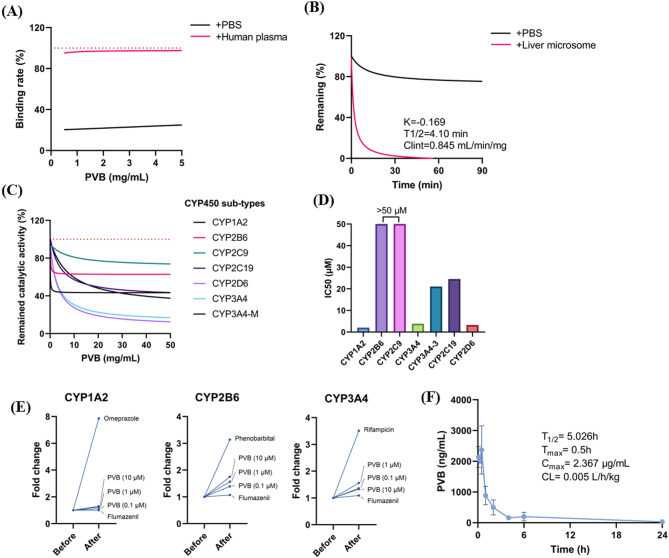

In vitro metabolic stability and cytotoxicity

No significantly RBC hemolysis activity was determined in the presence of PVB even at the concentration up to 64 µg/mL (Figure S2A). Meanwhile, by using CCK-8 kit, no cytotoxicity was found by PVB after 24 h of treatment at the concentration around MIC values (Figure S2B). And by using flow cytometer analysis, no obvious apoptosis inducement was observed by PVB (Figure S2C). In addition, there was no genotoxicity found after treated with varied concentrations of PVB in the presence or absence of S9 liver microsomes (Table S1). PVB exhibited high plasma protein binding ability, which indicated that it could be stably released in the blood (Fig. 6A), however, the compound was relatively unstable in the presence of liver microsome with the half-life of 4.1 min and clearance rate of 0.845 mL/min/mg (Fig. 6B). Meanwhile, PVB could significantly inhibit the catalytic activity of CYP450 sub-types of CYP1A2, CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 with IC50 < 10 µM (5.91 µg/mL) (Fig. 6C and D), while moderately induce the catalytic activity of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 (Fig. 6E). By intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, PVB showed relatively poor pharmacokinetic profile as an antimicrobial agent with the Cmax of only 2.367 µg/mL, which was lower than the value of MICs (Fig. 6F). In all, PVB, as an antimicrobial agent, was more suitable for topical use rather than systemic administration.

Fig. 6.

In vitro metabolic stability analysis. (A) Plasma protein bind rate of PVB. The binding rate of 200 µg/mL warfarin sodium was set as 100%. (B) Remaining rate of PVB in the presence of liver microsome. (C) Inhibitory effects of PVB against CYP450 sub-types. (D) IC50 values distribution by PVB against the CYP450 sub-types. (E) Catalytic activity determination of CYP450 sub-types after induced by PVB. (F) Pharmacokinetics analysis of PVB by i.p. injection

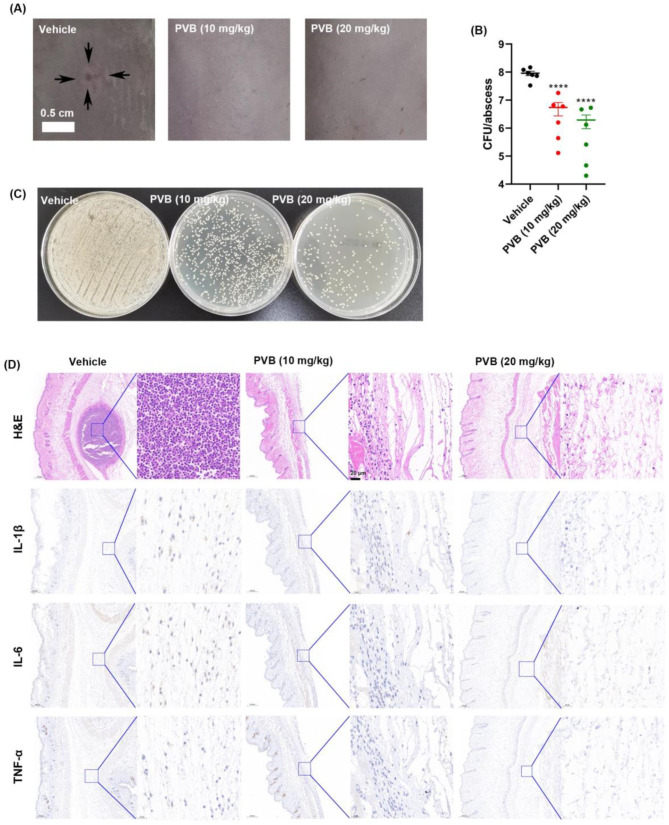

In vivo efficacy by PVB in an abscess model caused by the biofilm forming strain

The abscess infection model was constructed by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection with the biofilm forming strain MRSA ATCC 43,300. After 24 h post infection, an obvious abscess was observed in the vehicle group, while there was no visible abscess in the PVB-treated group (Fig. 7A). Accordingly, by CFU counting, 10–20 mg/kg of PVB was found to significantly reduced the viable bacterial loads in the abscess (Fig. 7B and C). The pathological analysis by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry indicated that there was an obvious abscess in the vehicle group with a lot of inflammatory cells infiltration and inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) expression. However, the abscess area and its related inflammation was almost disappeared after treated with 10 or 20 mg/kg of PVB (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Effective in vivo antimicrobial effects of PVB in an abscess model. (A) Representative images of abscesses after treated or untreated with PVB. (B) Viable cells quantification of the abscess (N = 6 mice per group). (C) Representative images of the viable cells counting in the abscess. (D) Pathological detection of the abscessed by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), respectively

The mice were well-tolerant with 20 mg/kg of PVB treatment by systemic (i.p.) administration (Figure S3A) without significant body weight fluctuation (Figure S3B). Meanwhile, no significant difference was observed between the vehicle group and PVB-treated group by blood routine analysis (Figure S3C). There was also no significant difference in the myocardial and renal function biomarkers CK and BUN between the vehicle and PVB-treated group, respectively (Figure S3D). Further, by Masson (s.c.) and H&E staining (i.p.), PVB exhibited neither fibroblasts toxicity nor systemic toxicity in vivo against myocardium, liver, spleen, lung or kidney without pathological changes observed (Figure S3E).

Discussion

With the emergence of increased drug resistance by S. aureus and S. epidermidis, it is urgently needed for new antimicrobial development. Moreover, the biofilm formation ability of S. aureus and S. epidermidis largely enhances the antibiotic resistance and makes the infections refractory. By drug repurposing, our present study identified a L-type calcium channel blocker PVB with in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial effects against Staphylococcus without resistance occurrence. PVB exhibited strong antibiofilm activity against the Staphylococcus on varied surfaces. And PVB could also showed synergistical antimicrobial activity with some conventional antibiotics. Mechanism study indicated that the transmembrane PMF disruption and ROS induction were the new antimicrobial targets by PVB.

PVB exhibited effective antimicrobial activity against both S. aureus and S. epidermidis with the MIC of 8–16 µg/mL. Similarly, Mao et al. (2023). reported the MIC50/MIC90 values of PVB against S. aureus were 12.5–25 µM (7.39–14.79 µg/mL). Although, the biofilm inhibitory effects by PVB were identified by Mao et al., they reported that no eradicating effects against the pre-formed biofilm of a S. aureus clinical isolate CHS101. However, in our study, by using the crystal violet staining, CFU counting and LCSM observation, we found that PVB could significantly inhibit the biofilm formation and further eradicate the established biofilms against both S. aureus and S. epidermidis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). In addition, PVB could also exhibit antibiofilm effects against the biofilms on Ti-discs (Fig. 4). The difference between our study and the previously reported data could probably be due to the different bacterial strains used and incubation conditions. Furthermore, our study identified new antimicrobial mechanisms by PVB that have not been reported yet. On one hand, PVB could disrupt the transmembrane PMF balance, which is an important factor for biofilm formation. On the other hand, PVB could effectively induce ROS production. In addition, PVB was widely repurposed for other diseases. For example, PVB was reported to reduce excessive systemic inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide by inhibiting neutrophil priming (Chen et al. 2021). PVB can specifically induce apoptosis in melanoma cell lines by inhibiting the intracellular chaperone activity of Hsp70 system. Thus, PVB was also a promising anti-cancer agent (Dublang et al. 2021).

In our present study, PVB was found to disrupt the PMF components of both transmembrane potential and transmembrane proton concentration. PMF regulates various bacterial biological processes, such as ATP synthesis, signal transduction, motility, and active transport of molecules (Yang et al. 2023). PMF is also essential for phenotypic antibiotic tolerance in bacteria and is correlated with the formation of biofilms and high resistant persister cells (Wan et al. 2023). In addition, since some antibiotics penetrating the bacterial cell membranes rely on the transmembrane electrochemical gradient, PMF disruptors could be potential adjuvants exerting synergistically antimicrobial effects with antibiotics (Liu et al. 2021). As we expected, PVB exhibited obvious synergistical antimicrobial effects with AMP, CEF, and OXA, respectively (Fig. 2J), however, some antibiotics (like KANA and TOB) could show antagonistic effect with the PMF disruptor. Because PMF also controls the antibiotics efflux (Liu et al. 2021).

PVB also induces the ROS production, which mainly included the components of •O2- and H2O2. H2O2 could directly kill bacteria by interacted with thiol groups in proteins, cell membranes, as well as DNA (Dryden et al. 2017). Although, the activity of H2O2 is extremely short, other component, such as •O2-, may enhance its antimicrobial activity. And ROS may also be one of the key reasons for the antibiofilm effects (Dryden 2018) by PVB. Additionally, as Mao et al. (2023). reported, PVB could increase the bacterial cell membrane permeability. Cell membrane disruptor often exhibits rapidly bacterial killing activity without probability of resistance occurrence, which is also effective against persister cells due to its proliferation-independent antimicrobial effects (Kim et al. 2018). Thus, PVB exhibited triple antimicrobial mechanisms against Staphylococcus. Multiple antimicrobial targets by PVB exerted advantages that are unreplaceable by conventional antibiotics. As previously reported, Martin et al. identified a compound SCH-79,797 and its optimized derivative Irresistin-16 with great antimicrobial potential against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens without resistance occurrence by targeting the folate metabolism and bacterial membrane integrity (Martin et al. 2020).

Although PVB is safe in vivo as a non-antibiotic, the toxicity is still needed re-assessed in the present study as an antimicrobial agent. Through a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in refractory dyspepsia patients, PVB was proved to be well-tolerant even after 8 weeks of treatment with 50 mg and 3 times per day, although, no significant benefit in improving the symptoms was found (Kamolsripat et al. 2024). And by a Meta-analysis, Qin et al. included 42 clinical trials with 8457 participants to assess the efficacy and safety of antispasmodics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. They found that PVB showed no significantly adverse events compared with the placebo (Qin et al. 2022). In addition, 3–10 µM of PVB was reported to significantly inhibit primed neutrophil-specific respiratory bursts and migration. PVB can prevent the liver and lung form LPS-induced damage in a mice model at the dose of 15 mg/kg (Chen et al. 2021). Thus, PVB is relative safe in vivo by systemic use. Similarly, Ouyang et al. (2024) reported that PVB could inhibit the activation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways and reduce ROS production in neutrophils, hence inhibit the inflammatory progression. In this study, given that the relatively poor pharmacokinetic results with toxicity to CYP450 by PVB, and to minimize the toxicity of PVB, we assessed the in vivo antimicrobial activity by an abscess model, which is one of the most common skin and soft tissue infection types caused by S. aureus. By topical use of 10–20 mg/kg of PVB, the viable bacterial loads in the abscess were significantly reduced with diminished inflammation infiltration (Fig. 7), which could probably due to the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory dual mechanisms by PVB.

Antibiotics development, especially for the treatment of Staphylococcus high resistant phenotypes and biofilms, is undoubtedly one of the greatest challenges to global health. By drug repurposing, the antispasmodic reagent, L-type calcium channel blocker, PVB exhibited strong bactericidal activity against S. aureus/S. epidermidis, its biofilms and persister cells. Mechanism study identified two new antimicrobial models of action by PVB, which included the disruption of transmembrane PMF and induction of ROS. The rapid bacterial killing activity and low probability of resistance occurrence of PVB may owning to its multiple antimicrobial targets. Although, our data indicates that PVB exhibits relatively poor pharmacokinetics by systemic use with moderate impact on CYP450, PVB exhibited effectively in vivo antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects in an abscess model caused by the biofilm forming strain MRSA ATCC 43,300. Thus, PVB is a promising antimicrobial and immunomodulatory reagent with significant interest for the treatment of refractory skin and soft tissue infections caused by MRSA/S. epidermidis and its biofilm or persister cells.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank WellBio (Changsha, China) for the assistance of flow cytometry analysis.

Abbreviations

- PVB

Pinaverium bromide

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- Ti

titanium

- PMF

proton motive force

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute

- MH

Mueller-Hinton

- OD630nm

optical density at 630 nm

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MBC

minimum bactericidal concentration

- CFUs

colony forming units

- CIP

ciprofloxacin

- VAN

vancomycin

- FICI

fractional inhibitory concentration index

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- SEM

scanning electronic microscopy

- TEM

transmission electronic microscopy

Author contributions

PS and YW conceived and designed research. PS, YY and SL conducted most of the experiments. PS wrote the manuscript. PS, SG and GH analyzed the research data and made data curation and figures. YY and DX prepared study materials, reagents, and analysis tools. YW reviewed and edited the manuscript. PS and YW supervised the entire experimental work. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82202591 and 82072350), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant number 2024JJ5514 and 2022JJ70046).

Data availability

All data associated with the article have been included in this manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This murine-related laboratory procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (NO. CSU-2022-0599).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdulgader SM, Shittu AO, Nicol MP, Kaba M (2015) Molecular epidemiology of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Africa: a systematic review. Front Microbiol 6:348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhadidi A, Alzer H, Kalbouneh H, Abu-Ghlassi T, Alsoleihat F (2020) Assessment of the dental morphological pattern of living Jordanian Arabs suggesting a genetic drift from the Western-Eurasia pattern: a cone beam computed tomography study. Anthropol Anz 77(3):205–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner H, Mack D, Rohde H (2015) Structural basis of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation: mechanisms and molecular interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 5:14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Lee RE, Lee W (2020) A pursuit of Staphylococcus aureus continues: a role of persister cells. Arch Pharm Res 43(6):630–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu Y, Dolin H, Liu J, Jiang Y, Pan ZK (2021) Pinaverium bromide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced excessive systemic inflammation via inhibiting neutrophil priming. J Immunol 206(8):1858–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen MO (1990) Action of pinaverium bromide, a calcium-antagonist, on gastrointestinal motility disorders. Gen Pharmacol 21(6):821–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2023) M100 performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 33rd edition [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Conlon BP (2014) Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: Evidence of a role for persister cells: an investigation of persister cells, their formation and their role in S. aureus disease. Bioessays 36(10):991–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Schmitz FJ, Smayevsky J, Bell J, Jones RN, Beach M, Group SP (2001) Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin Infect Dis 32(Suppl 2):S114-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden M (2018) Reactive oxygen species: a novel antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 51(3):299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden MS, Cooke J, Salib RJ, Holding RE, Biggs T, Salamat AA, Allan RN, Newby RS, Halstead F, Oppenheim B, Hall T, Cox SC, Grover LM, Al-Hindi Z, Novak-Frazer L, Richardson MD (2017) Reactive oxygen: a novel antimicrobial mechanism for targeting biofilm-associated infection. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 8:186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dublang L, Underhaug J, Flydal MI, Velasco-Carneros L, Marechal JD, Moro F, Boyano MD, Martinez A, Muga A (2021) Inhibition of the human Hsc70 system by small ligands as a potential anticancer approach. Cancers 13(12):66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupieux C, Trouillet-Assant S, Camus C, Abad L, Bes M, Benito Y, Chidiac C, Lustig S, Ferry T, Valour F, Laurent F (2017) Intraosteoblastic activity of daptomycin in combination with oxacillin and ceftaroline against MSSA and MRSA. J Antimicrob Chemother 72(12):3353–3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formicki K, Korzelecka-Orkisz A, Tanski A (2019) Magnetoreception in fish. J Fish Biol 95(1):73–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FI, Teixeira P, Azeredo J, Oliveira R (2009) Effect of farnesol on planktonic and biofilm cells of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Curr Microbiol 59(2):118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guslandi M (1994) The clinical pharmacological profile of pinaverium bromide. Minerva Med 85(4):179–185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis A, Tsakris A, Kanellopoulou M, Maniatis AN, Pournaras S (2008) Effect of the proton motive force inhibitor carbonyl cyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Lett Appl Microbiol 47(4):298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Jin Z, Sun B (2018) MgrA negatively regulates biofilm formation and detachment by repressing the expression of psm operons in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol 84(16):66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamolsripat T, Thinrungroj N, Pinyopornpanish K, Kijdamrongthum P, Leerapun A, Chitapanarux T, Thongsawat S, Praisontarangkul OA, Pojchamarnwiputh S (2024) Efficacy and safety of pinaverium bromide as an add-on therapy in refractory dyspepsia: a randomized controlled trial. JGH Open 8(3):e13051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak N, Grygorcewicz B, Roszak M, Bochentyn B, Piechowicz L (2022) Comparative assessment of bacteriophage and antibiotic activity against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Int J Mol Sci 23(3):66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Zhu W, Hendricks GL, Van Tyne D, Steele AD, Keohane CE, Fricke N, Conery AL, Shen S, Pan W, Lee K, Rajamuthiah R, Fuchs BB, Vlahovska PM, Wuest WM, Gilmore MS, Gao H, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E (2018) A new class of synthetic retinoid antibiotics effective against bacterial persisters. Nature 556(7699):103–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhao Y, Zhao D, Gong T, Wu Y, Han H, Xu T, Peschel A, Han S, Qu D (2015) Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of thiazolidione derivatives against clinical staphylococcus strains. Emerg Microbes Infect 4(1):e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Mao R, Teng D, Hao Y, Chen H, Wang X, Wang X, Yang N, Wang J (2017) Antibacterial and immunomodulatory activities of insect defensins-DLP2 and DLP4 against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep 7(1):12124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, She P, Liu Y, Xu L, Li Y, Liu S, Hussain Z, Li L, Yang Y, Wu Y (2023) Triple combination of SPR741, clarithromycin, and erythromycin against Acinetobacter baumannii and its tolerant phenotype. J Appl Microbiol 134(1):66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jia Y, Yang K, Li R, Xiao X, Zhu K, Wang Z (2020) Metformin restores tetracyclines susceptibility against multidrug resistant bacteria. Adv Sci (Weinh) 7(12):1902227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tong Z, Shi J, Jia Y, Deng T, Wang Z (2021) Reversion of antibiotic resistance in multidrug-resistant pathogens using non-antibiotic pharmaceutical benzydamine. Commun Biol 4(1):1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, She P, Li Z, Li Y, Yang Y, Li L, Zhou L, Wu Y (2022) Insights into the antimicrobial effects of ceritinib against Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo by cell membrane disruption. AMB Express 12(1):150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WF, Jiang QY, Qi ZR, Zhang F, Tang WQ, Wang HQ, Dong L (2024) CD276 promotes an inhibitory tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma and is associated with poor prognosis. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 11:1357–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy FD (1998) Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339(8):520–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah TF (2012) Biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol 7(9):1061–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao T, Chai B, Xiong Y, Wang H, Nie L, Peng R, Li P, Yu Z, Fang F, Gong X (2023) In vitro inhibition of growth, biofilm formation, and persisters of Staphylococcus aureus by pinaverium bromide. ACS Omega 8(10):9652–9661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Sheehan JP II, Bratton BP, Moore GM, Mateus A, Li SH, Kim H, Rabinowitz JD, Typas A, Savitski MM, Wilson MZ, Gitai Z (2020) A dual-mechanism antibiotic kills gram-negative bacteria and avoids drug resistance. Cell 181(7):1518–1532e1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nasser A, Dallal MMS, Jahanbakhshi S, Azimi T, Nikouei L (2022) Staphylococcus aureus: biofilm formation and strategies against it. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 23(5):664–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang J, Hong Y, Wan Y, He X, Geng B, Yang X, Xiang J, Cai J, Zeng Z, Liu Z, Peng N, Jiang Y, Liu J (2024) PVB exerts anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the activation of MAPK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways and ROS generation in neutrophils. Int Immunopharmacol 126:111271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengfei S, Yaqian L, Lanlan X, Zehao L, Yimin L, Shasha L, Linhui L, Yifan Y, Linying Z, Yong W (2022) L007–0069 kills Staphylococcus aureus in high resistant phenotypes. Cell Mol Life Sci 79(11):552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin D, Tao QF, Huang SL, Chen M, Zheng H (2022) Eluxadoline versus antispasmodics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: an adjusted indirect treatment comparison meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 13:757969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She P, Liu Y, Wang Y, Tan F, Luo Z, Wu Y (2020) Antibiofilm efficacy of the gold compound auranofin on dual species biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Candida sp. J Appl Microbiol 128(1):88–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She P, Yang Y, Li L, Li Y, Liu S, Li Z, Zhou L, Wu Y (2023) Repurposing of the antimalarial agent tafenoquine to combat MRSA. mSystems 8(6):e0102623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, Network NHS, T, Participating NF, (2013) Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34(1):1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Liu Y, Huang X, Ding S, Wang Y, Shen J, Zhu K (2020) A broad-spectrum antibiotic adjuvant reverses multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Nat Microbiol 5(8):1040–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P, Lai Z, Jian Q, Shao C, Zhu Y, Li G, Shan A (2020) Design of heptad repeat amphiphiles based on database filtering and structure-function relationships to combat drug-resistant fungi and biofilms. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 12(2):2129–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall GC, Bryant GA, Bottenberg MM, Maki ED, Miesner AR (2014) Irritable bowel syndrome: a concise review of current treatment concepts. World J Gastroenterol 20(27):8796–8806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Wai Chi Chan E, Chen S (2023) Maintenance and generation of proton motive force are both essential for expression of phenotypic antibiotic tolerance in bacteria. Microbiol Spectr 11(5):e0083223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, She P, Chen L, Li S, Zhou L, Hussain Z, Liu Y, Wu Y (2021) Repurposing candesartan cilexetil as antibacterial agent for MRSA infection. Front Microbiol 12:688772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Li Y, Xu A, Soteyome T, Yuan L, Ma Q, Seneviratne G, Li X, Liu J (2024) Cell-wall-anchored proteins affect invasive host colonization and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Res 285:127782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Hay ID, Cameron DR, Speir M, Cui B, Su F, Peleg AY, Lithgow T, Deighton MA, Qu Y (2015) Antibiotic regimen based on population analysis of residing persister cells eradicates Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Sci Rep 5:18578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Tong Z, Shi J, Wang Z, Liu Y (2023) Bacterial proton motive force as an unprecedented target to control antimicrobial resistance. Med Res Rev 43(4):1068–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Isguven S, Evans R, Schaer TP, Hickok NJ (2023) Berberine disrupts staphylococcal proton motive force to cause potent anti-staphylococcal effects in vitro. Biofilm 5:100117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with the article have been included in this manuscript.