Abstract

Controlling gene expression is useful for many applications, but current methods often require external user inputs, such as the addition of a drug. We present an alternative approach using cell-autonomous triggers based on RNA stem loop structures in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNA. These stem loops are targeted by the RNA binding proteins Regnase-1 and Roquin-1, allowing us to program stimulation-induced transgene regulation in primary human T cells. By incorporating engineered stem loops into the 3′ UTRs of transgenes, we achieved transgene repression through Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 activity, dynamic upregulation upon stimulation, and orthogonal tunability. To demonstrate the utility of this system, we employed it to modulate payloads in CAR-T cells. Our findings highlight the potential of leveraging endogenous regulatory machinery in T cells for transgene regulation and suggest RNA structure as a valuable layer for regulatory modulation.

Introduction

Controlling gene expression is beneficial for a wide range of applications in both basic and translational sciences. However, most techniques used to modulate gene expression typically leverage molecular actuators, such as small molecule drugs, to induce changes in gene expression.1 While this type of external, user-dependent control is beneficial in many contexts, there may be instances in which cell-autonomous control, or modulation that does not require user-given external inputs to actuate, is preferable. These instances include situations when it is unclear when to invoke control or the desired modulation is in response to a specific cell state, neither of which can be adequately monitored in vivo.

T cells and immune cells more generally have become a desirable chassis for engineering regulatable transgene expression. This is largely due to the burgeoning of the cell therapy field, following earlier therapeutic successes in hematological malignancies using autologous T cells genetically modified with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs).2−6 Early iterations of CAR-T cells were not engineered with systems to dynamically modulate transgene expression; however more recent efforts have led to the development of drug-regulatable CAR-T cells, which can be leveraged to mitigate toxicity either through regulation of the CAR itself or other effector payloads.7−10 These systems are useful, yet methods to modulate transgene expression in a cell-autonomous way remain limited in T cells, a cell type in which drug-independent regulation may be particularly useful because of their current and potential therapeutic applications. Currently, the most notable way to dynamically modulate transgene expression in T cells without small molecule drugs is by using the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) promoter, which can enable activation-specific transgene expression.11

Promoter-level control of transgene expression is powerful; yet other layers of regulation may be similarly potent and used orthogonally. In T cells, post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression facilitated by RNA binding proteins (RBPs) also constitutes a significant layer of control that shapes functional responses. In particular, the RBPs Regnase-1 (Reg1) and Roquin-1 (Roq1) are potent negative regulators of T cell inflammatory gene expression, and disruption of their endogenous function leads to hyperinflammatory pathology.12−15 Recent studies have also shown that their disruption in therapeutic T cells enhances their antitumor activity, but also their toxicity.16−19 This body of work highlighted the strong regulatory capabilities of Reg1 and Roq1 in T cells and led us to consider whether this system could be harnessed to modulate transgenes of interest.

Both Reg1 and Roq1 bind to stem loops located at the 3′ UTR of mRNAs, many of which include factors associated with T cell activation, targeting them for destabilization and subsequent degradation in resting T cells.20−22 Upon stimulation through the T cell receptor (TCR), Reg1 and Roq1 are degraded by mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein 1 (MALT1), transiently halting the inhibitory effects of Reg1 and Roq1 activity on inflammatory gene expression (Figure 1A).21,22 Here we explore leveraging this endogenous regulatory system in primary human T cells to modulate the expression of transgenes. To test this, we designed stem loops based on select putative stem loop targets of Reg1 and Roq1 and encoded them into the transgene 3′ UTR. For initial proof-of-concept, we tested the effect of stem loops on in vitro transcribed mRNA, using the clinical stage CD19-targeting CAR (CAR019) as a model transgene. We then encoded stem loops into lentiviral constructs to determine whether their function was affected by the presence of other expression modulating elements in the 3′ UTR, namely the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE), a large enhancer element that is widely used to increase transgene expression in cell therapy settings. To evaluate the dynamics of transgene modulation mediated by stem loops, we measured the expression of regulated CAR019 after stimulation with CD3/CD28 or antigen-bearing tumor cells. Finally, we explore promoter-level expression tuning of regulated CAR019 and apply stem loop modulation to other molecular payloads. Overall, we find that stem loops targeted by Reg1 and Roq1 may be used to dampen transgene expression and to program stimulation-induced upregulation in human T cells.

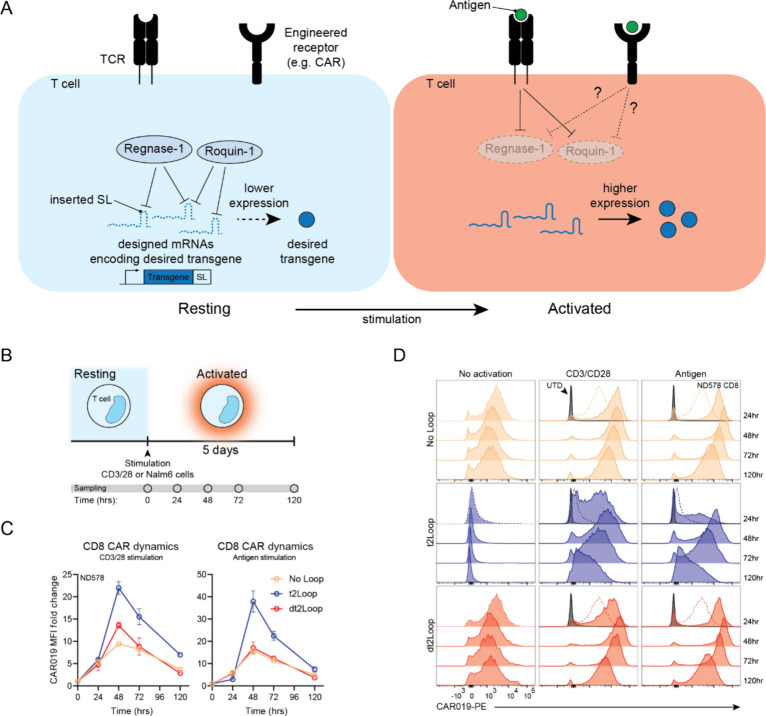

Figure 1.

Stem loop designs and their regulatory activity on transgene expression in primary human T cells. (A) Conceptual schematic demonstrating stem loop mediated transgene expression modulation triggered by T cell stimulation in endogenous and engineered T cell contexts. Top, in resting T cells, endogenous regulatory RBPs, specifically Regnase-1 and Roquin-1, regulate the expression of transcripts encoding inflammatory factors by acting on stem loops located at the 3′UTR. Upon stimulation and activation of T cells, Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 are degraded, increasing expression of inflammatory factors. Bottom, this system can be harnessed to regulate transgenes of interest by inserting regulated stem loops in the 3′UTR of transgenes, resulting in engineered regulation. (B) Top, single loop designs based on the endogenous TNFα stem loop. Bottom, double loop designs based on the TNFα stem loop joined to the endogenous ICOS stem loop. (C) Top, characterization of CAR-positive cells 24 h after electroporation of CAR mRNAs bearing different stem loops in CD8+ T cells. Each data point in each experimental group represents an independent donor (n = 4). Bottom, CAR expression kinetics over time after mRNA electroporation. Data shown is pooled from two independent donors (n = 2). Bars represent SD (D) Representative flow plots showing CAR expression 24 h after mRNA electroporation in CD8+ T cells from donor ND580.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Design and Construction

All plasmids used in this study were designed using Geneious Prime (Dotmatics) and generated via restriction cloning of synthesized DNA oligos (IDT) or gene fragments (Genscript) into pTRPE, a third-generation self-inactivating lentiviral vector, followed by sequence verification using Nanopore/Sanger sequencing (Plasmidsaurus/Genewiz).23 Plasmids and sequencing primers are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

In Vitro Transcription (IVT) of mRNA

mRNA was transcribed in vitro using previously described methods.24 Briefly, plasmids encoding a 4–1BB-based, second generation CD19-targeting CAR (CAR019) with variable stem loops in the 3′UTR region were linearized overnight, followed by in vitro transcription of mRNA using the T7 mMessage ULTRA kit (Thermo Fisher) per manufacturer instructions. mRNAs were purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen).

mRNA Electroporation into T Cells

T cells were washed three times with Opti-MEM (Gibco) reduced serum media and resuspended at 1 × 108 cells/mL in the same media. T cells were dosed at a concentration of 1 μg mRNA per 106 cells. Cells were electroporated in a 2 mm cuvette using the ECM830 Square Wave Electroporator (Harvard Apparatus BTX) with the following settings: 500 V, 700 μs.

Primary T Cell and Cell Line Culture

Healthy donor PBMCs were obtained after written informed consent under a University Institutional Review Board-approved protocol. The Human Immunology Core (HIC) at the Perelman School of Medicine processed donor PBMCs and isolated T cells. T cells were cultured in R10 media consisting of RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies) with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES (Gibco), 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), 1% MEM NEAA (Gibco), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cell lines used in this study Nalm6 and HEK293T cells we obtained from the ATCC, confirmed free from mycoplasma infection (Cambrex MycoAlert), authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling (ATCC), and used at passage numbers <25. Nalm6 cells were engineered to express GFP and luciferase by lentiviral transduction and were grown and maintained in R10 media.

Lentiviral Vector Production

Lentiviral vector production was performed using previously established techniques.25 Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with lentiviral vectors encoding the dual-promoter reporter system with various transgenes (see Supplementary Table S2) and lentiviral packaging plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Supernatants were collected at 24 and 48 h after transfection and concentrated using high-speed ultracentrifugation. To generate lentiviral stocks, concentrated batches of lentivirus were resuspended in cold R10 media and stored at −80C.

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout

Single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences targeting Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 from a previous study validating their efficiency were used to perform knockouts.19 sgRNA sequences were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Gene disruption was performed using a previously described protocol.26 Briefly, T cells were washed three times in Opti-MEM and resuspended in P3 nucleofection solution (Lonza) at 1 × 108 cells/mL. Each sgRNA (5 μg per 10 × 106 cells) was incubated with Cas9 nuclease (Aldevron, 10 μg per 10 × 106 cells) for 10 min at room temperature to generate ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. For no knockout (Mock) groups, no sgRNA was used and for multiple knockout groups, RNPs targeting each gene were incubated separately before combining. Cells were electroporated in batches of 10 × 106 cells (100 μL) with a mix of RNP complex and 16.8pmol of electroporation enhancer (IDT) in nucleofection cuvettes (pulse code EH111) using a 4D-Nucleofector X-Unit (Lonza). To quantify indel percentages, genomic DNA was isolated from cells using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. The target knockout locus was then PCR amplified using previously reported primers, gel extracted, and then Sanger sequenced. Sequencing traces were analyzed with Synthego’s browser-based ICE analysis tool to calculate the discordance in sequences for each sample compared to an unedited sequencing trace. This metric is used to estimate the percentage of indels present in the experimental sequencing trace.

Flow Cytometry Antibodies

The following antibodies were used (from BioLegend): CD3-BV711 (clone OKT3); (from BD): CD4-PE-Cy5 (clone RPA-T4), CD8-APC-Cy7 (clone SK1), ICOS-BV650 (clone DX29); (from CytoArt): FMC63-PE (clone R19M). Live/Dead Fixable Aqua (Invitrogen) was used delineate live and dead cells.

Intracellular Staining for Bcl-xL

Cells were incubated with Bcl-xL rabbit-derived monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen; clone C.85.1) at a 1:1000 dilution in FACS buffer (2% FBS in 1X PBS) for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were washed in FACS buffer and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated AffiniPure Donkey antirabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a 1:1000 dilution in 1X intracellular staining permeabilization wash buffer (BioLegend) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer before flow cytometry analysis.

Stimulation Assays

1 ×105 T cells were plated in triplicate in 96-well plates in 100 μL of R10 either alone, with 2.5 μL of CD3/CD28 activator (STEMCELL Technologies), or with 0.5 × 105 Nalm6 tumor cells in a total volume of 200 μL. For each time point, a separate set of triplicate wells were plated for each experimental group. Cells were then assayed by flow cytometry at 24, 48, 72, and 120 h time points.

Killing Assays

0.5 × 105 CAR-T cells (CAR% normalized across different groups) were plated in triplicate and cocultured with 0.5 × 105 Nalm6 tumor cells. After 18 h, remaining tumor cells were counted by flow cytometry using CountBright absolute counting beads (Invitrogen).

IL18 ELISA

0.5 × 105 CAR-T cells (CAR% normalized across different groups) were plated in triplicate and either cultured alone, with 2.5 μL of CD3/CD28 activator (STEMCELL Technologies), or cocultured with 1 × 105 Nalm6 tumor cells in 200 μL R10. Supernatants were sampled at 24 and 48 h and assayed neat with the total IL18 DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer instructions.

Results

Design and Testing of Stem Loops That Mediate Regulatory Activity

To establish proof-of-concept of transgene modulation using stem loops targeted by Reg1 and Roq1 in primary human T cells, we began with designs based on the well-characterized TNFα stem loop. The TNFα stem loop is an established target of Reg1 and Roq1 in T cells, and previous work has extensively detailed the biophysical interaction between the murine versions of Roq1 and the TNFα stem loop, which has high sequence and structural conservation with the human analog.27 While a minimal functional region of the constitutive decay element (CDE) was identified consisting of only the P2-L2 stem loop, we chose to use the full P1-L1-P2-L2 structure (WT loop) as our basic design (Figure 1B). In addition, TNFα was the most dynamically upregulated gene in activated versus resting T cells among a set of gene candidates bearing stem loops targeted by Roq1 in their 3′ UTRs, providing further support for the use of this CDE as a starting point (Supplementary Figure S1). Next, we converted the G-U wobble base pairing into canonical Watson–Crick G-C base pairing in the P1 stem (tight loop or tLoop) to increase the folding stability of the loop, since their function is dependent on secondary structure (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure S2A–D).27 We also altered the L2 bases known to interact with Roq1 from C-G-U to A-C-A (dead loop or dLoop) to abrogate Reg1 and Roq1 interaction as negative controls (Figure 1B).27 We considered that having additional loops could tighten regulation and designed double loop versions by adding the P1-L1 stem loop derived from inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS), an established target of both Reg1 and Roq1, and joining the loops with a poly-A linker (Figure 1B, Supplementary Table S1).19,27,28 Using CAR019 as a model transgene, we electroporated mRNAs encoding CAR019 and bearing the described 3′UTR loop variants into primary human T cells. In both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, mRNAs bearing single or double functional loops (WT or tight) demonstrated reduced CAR019 expression at 24 h and onward, while those bearing dead versions showed comparable expression to the no loop control (Figure 1C–D, Supplementary Figure S3A,B). Compared to the no loop control, the presence of the dead loops did not change CAR019 expression dynamics, suggesting that the loops themselves do not inherently affect expression (Figure 1C, Supplementary Figure S3A). These results established proof-of-concept that stem loops targeted by Reg1 and Roq1 can regulate transgene expression in primary human T cells. Since we observed greater expression from functional single loops compared to double loops, we chose the more dynamically regulated and less “leaky” double loop variants to test in a constitutive setting using lentiviral vectors (Figure 1C, Supplementary Figure S3A).

To analyze stem loop modulation in a constitutive setting using lentiviral vectors, we designed a test system with an independent reporter signal as baseline for normalization. In our system, reporter and loop-regulated transgenes are expressed by separate promoters and therefore independent mRNA transcripts (Figure 2A). With this dual-promoter system, stem loop modulated expression can be normalized to constant reporter expression. We combined murine phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (mPGK) and human elongation factor 1 alpha (hEF1α) promoters in a back-to-back orientation and used monomeric EGFP (mEGFP) as a fluorescent reporter (Figure 2B).29 Additionally, we wanted to explore if stem loop regulation is impacted by the WPRE sequence, which forms a large tertiary mRNA stabilizing structure and is widely used to boost transgene expression.30 To analyze its effects, we designed versions of our test system with and without WPRE downstream of the stem loop (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The impact of the WPRE on stem loop regulation and dependence on Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 activity. (A) Conceptual schematic depicting the dual-promoter test system and rationale of use. Top, reporter expression is constant while transgene expression is modulated through degradation (dotted). Bottom, transgene expression can be normalized to reporter expression. P = promoter, SL = stem loop. (B) Specific constructs tested with variable stem loops to determine the effect of the WPRE. (C) Comparison of normalized CAR expression (NE) with and without the WPRE using different stem loops in rested CD8+ T cells. Representative flow plots showing CAR and GFP expression from ND451 are shown on the right. 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis with significant P values shown for comparisons between loop and dead loop counterparts. (D) Characterization of regulation ratios for different stem loops with and without the WPRE in CD8+ T cells. Bars represent SD. Multiple unpaired t tests were used for statistical analysis. For (C–D), individual data points in each experimental group represent independent donors (n = 2 or 3). (E) Comparison of normalized CAR/GFP between mock unedited and Reg1 and Roq1 DKO CD8+ T cells. Representative flow plots showing CAR and GFP expression from ND578 are shown on the right. Individual data points in each experimental group represent independent donors (n = 4).

In line with results using electroporated mRNA, stem loops also demonstrated regulatory function in a constitutive setting in both CD4+ and CD8+ primary human T cells (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figures S4A, S5). Comparing median fluorescent intensities (MFIs) of CAR019 normalized to mEGFP (i.e., MFICAR/MFImEGFP = normalized expression or “NE”), we found that constructs with functional loops, 2Loop and t2Loop, demonstrated dampened NE while analogous constructs with dead loops, d2Loop and dt2Loop, retained comparable NE to each other and to the no loop control (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S4A). While not statistically significant, the “tightened” t2Loop showed slightly lower NE compared to 2Loop, suggesting that energetic changes such as replacing wobble base pairing with more energetically favorable Watson–Crick base pairing even in structures not directly required to mediate function (P1 stem) can potentially influence regulation in designed secondary RNA structures (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S4A). We also determined that the WPRE did not significantly affect stem loop regulation and instead only contributed to an overall increase in NE with the WPRE present (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figures S4A, S5). This is consistent with the known expression enhancing function of the WPRE and demonstrates that its effect can be separate from the stem loop when used together. To quantify this, we compared the “regulation ratio”, which we defined as the ratio between dead loop normalized expression (NEdead) and functional loop normalized expression (NEfunctional), between constructs with and without the WPRE (Figure 2D, Supplementary Figure S4B). A greater ratio indicated a larger difference between transgene expression and transgene repression with stem loops. There was no significant difference in the regulation ratios between constructs with or without the WPRE in both the normal and tight loop versions (Figure 2D, Supplementary Figure S4B). However, the tight loop version displayed a greater regulation ratio, indicating that it has a greater functional range between transgene expression and repression, motivating us to select the tight loop version for subsequent experiments (Figure 2D, Supplementary Figure S4B).

Confirming the Regulatory Roles of Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 on Stem Loop Mediated Transgene Modulation

While stem loop designs were inspired by putative targets of Reg1 and Roq1 and dead loop controls gave a degree of confidence that regulation was dependent on Reg1 and Roq1, we wanted to confirm the roles of Reg1 and Roq1 by measuring how Reg1- and Roq1- deficient T cells behaved when transduced with a transgene regulated by these loops. To this end, we generated Reg1 and Roq1 double knockout (DKO) primary human T cells and transduced them with the t2Loop-regulated CAR019 alongside no loop and dt2Loop controls. In both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, t2Loop attenuated CAR019 expression while dt2Loop maintained similar CAR019 expression compared to the no loop control in unedited Mock cells, as expected (Figure 2E, Supplementary Figures S6–S8). However, DKO of Reg1 and Roq1 attenuated expression modulation, rescuing CAR019 expression to levels near that of the no loop control and confirming that regulatory function is mediated through these RBPs (Figure 2E, Supplementary Figures S6–S8). To dissect the individual contributions of Reg1 and Roq1 on expression regulation, we further measured rescue of transgene repression in Reg1- or Roq1- deficient T cells. Interestingly, disruption of Roq1 alone was able to rescue transgene repression to expression levels near that with no stem loop regulation, while Reg1 disruption could not (Supplementary Figure S15). These observations suggest that modulation of transgene expression by inclusion of stem loops tested here in transcript 3′UTRs in human T cells is largely dependent on Roq1 activity.

T Cell Stimulation Can Trigger Upregulation in Transgenes Regulated by Stem Loops

Various studies have established that signaling downstream of the TCR transiently represses Reg1 and Roq1 activity through the MALT1 paracaspase.21,22 As a result, transcripts targeted by Reg1 or Roq1 are under a layer of post-transcriptional repression when T cells are resting and become derepressed upon activation through TCR stimulation (Figure 3A).21,22 We hypothesized that this dynamic could be potentially harnessed to program activation-specific upregulation of transgene expression. However, whether activation through an engineered receptor bearing analogous components of TCR intracellular domains, such as a CAR, can facilitate the same effect has not been explored (Figure 3A). To examine this, we monitored the expression dynamics of a stem loop regulated transgene after stimulation through anti-CD3/CD28 or through antigen-specific ligation of the engineered CAR receptor at 24, 48, 72, and 120 h (Figure 3B–C). We used the same constructs as previously described with CAR019 as the stem loop regulated transgene and observed changes in CAR019 expression after stimulation through the CAR itself. In the absence of stimulation, CAR019 expression remained consistent over time in all groups (Figure 3D). The dt2Loop demonstrated comparable CAR019 expression to no loop, while t2Loop showed dampened expression (Figure 3C,D, Supplementary Figures S9, S10). Treatment with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation induced similar fold changes of CAR019 upregulation in both the dt2Loop and no loop groups but the greatest upregulation in the t2Loop group (Figure 3C,D, Supplementary Figures S9, S10). Upregulation of CAR019 expression was transient and increased up to about 2 days before expression began to taper back down toward expression levels in unstimulated cells (Figure 3C,D, Supplementary Figures S9, S10). Similarly, stimulation through the CAR using CD19-positive Nalm6 tumor cells also induced the greatest expression upregulation in the t2Loop group and lower, comparable levels of upregulation in the dt2Loop and no loop groups (Figure 3C,D, Supplementary Figures S9, S10). These dynamics suggest that stem loops can facilitate transgene upregulation in response to both the T cell receptor and by ligation of the CAR scFv.

Figure 3.

Regulation by stem loops enables stimulation-induced upregulation of transgene expression. (A) Conceptual schematic depicting regulation of Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 activity and downstream stem loop regulated transgene expression through TCR stimulation and potential regulation from stimulation through engineered receptors, such as a CAR. (B) Conceptual schematic of the stimulation scheme used, and time points used to measure CAR expression. (C) CAR019 MFI fold change dynamics over time after CD3/CD28 (left) and antigen (right) stimulation in CD8+ T cells. Data shown is from one representative donor of the experiment performed in technical triplicate in 3 independent donors with bars representing SD (D) Representative flow plots of CAR019 expression following no (left), CD3/CD28 (middle), and antigen (right) stimulation over time in ND578. Dotted traces at the 24 h time point indicate expression levels without stimulation.

Tuning of Stem Loop Mediated Transgene Modulation

In the systems tested so far, we have used the relatively strong hEF1α promoter to drive expression of the regulated transgene. As a result, while we observe expression regulation with the t2Loop compared to controls, transgene expression is still present compared to untransduced cells. This may or may not be desirable depending on the application. With a CAR as our model transgene, which can be used to induce modulation of itself, some level must be present at baseline to be able to trigger regulation. However, with other transgenes it may be unnecessary or undesirable to have baseline expression. As a result, we were interested to explore functionally tuning regulated expression levels to make them very low or absent at baseline.

To achieve this, we replaced the hEF1α promoter with weaker promoters including a previously reported weaker variant of hEF1α, hEF1α-3,31 and the ubiquitin C (UbC) promoter, which is reported to be one of the weakest across different cell types (Figure 4A).32 With the CAR as the regulated transgene, exchanging the hEF1α with hEF1α-3 led to no differences in CAR019 expression in either t2Loop or no loop versions (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S11). In contrast, exchanging the hEF1α promoter for the UbC promoter decreased CAR019 expression in both t2Loop and no loop versions, with the t2Loop version nearing UTD levels of expression (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S11). To confirm that these expression level differences have functional effects, we evaluated the tumor killing abilities of each of these versions. With the hEF1α promoter, CAR019 with no loop had the greatest killing while CAR019 with t2Loop had slightly weaker killing (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S12). Switching hEF1α for hEF1α-3 did not alter killing function, while switching it for UbC led to decreased killing in both t2Loop and no loop groups, with the t2Loop group decreasing to killing function comparable to that of UTD cells (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S12). These results suggest that varying the promoter strength provides another layer of control to functionally tune the desired regulated expression levels without disrupting the regulatory function of stem loops.

Figure 4.

Functional tuning and application of stem loop modulation to other transgenes in human CAR-T cells. (A) Constructs tested to determine whether expression can be tuned by varying promoter strength without affecting stem loop function. (B) CAR019 expression levels under different promoters in CD8+ T cells. Representative flow plots of CAR019 and GFP expression from ND580 are shown on the right. Individual data points in each experimental group represent independent donors (n = 4). Bars represent SD (C) Tumor killing after 18 h after coculture with CAR-T cells with different promoters. Data shown is from ND602 and is representative of two independent experiments using two independent donors (n = 2). Bars represent SD (D) Constructs tested to evaluate stem loop modulation of IL18 expression with constitutive CAR019 expression. (E) Constructs tested to evaluate stem loop modulation of Bcl-xL expression with constitutive CAR019 expression using tLNGFR as a control transgene. (F) IL18 production from CAR-T cells without stimulation, with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, and with antigen stimulation. Data shown is from ND616 and is representative of three independent experiments in three independent donors (n = 3). Bars represent SD. Multiple unpaired t tests were used for statistical analysis. (G) Bcl-xL expression in CD8+ CAR-T cells without stimulation, with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, and with antigen stimulation. Representative flow plots of Bcl-xL expression under different stimulation conditions from ND578 are shown on the right. Individual data points in each experimental group represent independent donors (n = 3). Bars represent SD 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis.

Application of Stem Loop Mediated Regulation to Other Transgenes in CAR-T Cells

With evidence that we could tune expression of transgenes regulated by stem loops without affecting stem loop function, we sought to apply regulation to other transgenes in T cells. Of particular interest in T cells are therapeutic payloads, such as effector cytokines or factors that promote survival or mitigate exhaustion.33,34 To apply and test stem loop modulation on other transgenes in CAR-T cells, we made new constructs by swapping out CAR019 from the previous construct architecture with other transgenes and moving it under the mPGK promoter (Figure 4D-E). We chose to test the cytokine, IL18, and the pro-survival factor, Bcl-xL, as examples of secreted and intracellular payloads respectively (Figure 4D-E). To test regulation of IL18, we used the stronger hEF1α promoter because baseline expression of IL18 has not been shown to be toxic and may be beneficial (Figure 4D).35 On the other hand, expression of the pro-survival factor Bcl-xL is implicated in some malignancies, motivating stricter control of baseline expression levels and use of the weaker UbC promoter (Figure 4E).36,37

Application of stem loop regulation to IL18 in CAR-T cells dampened IL18 secretion across different stimulation conditions (Figure 4F, Supplementary Figure S13). Interestingly, although we used the strong hEF1α to drive IL18 expression, in resting cells we observed below background levels of secreted IL18 (Figure 4F, Supplementary Figure S13). Stimulation with both anti-CD3/CD28 and antigen ligation of the CAR led to high IL18 secretion, but lower IL18 secretion when regulated with t2Loop compared to no loop (Figure 4F, Supplementary Figure S13). Application to Bcl-xL in CAR-T cells led to expression dynamics more consistent with activation-specific upregulation. Using truncated human low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (tLNGFR) as a control transgene, we similarly measured Bcl-xL expression across different stimulation conditions. Without stimulation, use of t2Loop dampened Bcl-xL expression compared to no loop, though both t2Loop regulated and no loop regulated Bcl-xL had greater Bcl-xL expression than tLNGFR and UTD controls (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S14). Stimulation of the TCR with anti-CD3/CD28 increased Bcl-xL expression in all groups to comparable expression levels (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S14). Compared to no stimulation, CD3/CD28 stimulation only slightly increased Bcl-xL expression in CAR-T cells with no loop regulation on Bcl-xL, but approximately doubled the Bcl-xL MFI in CAR-T cells with t2Loop regulated Bcl-xL (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S14). These dynamics indicate that these stem loops have the capacity to serve as expression dampeners in resting human CAR-T cells, which may be useful for controlling beneficial but potentially risky transgenes. Stimulation with antigen also equalized Bcl-xL expression levels between CAR-T cells with either t2Loop or no loop regulated Bcl-xL, which still displayed slightly greater Bcl-xL MFIs compared to CAR-T cells with tLNGFR controls and UTD cells (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S14). While antigen stimulation equalized Bcl-xL expression in Bcl-xL expressing CAR-T cells, this was due to a decrease in Bcl-xL MFI in the no loop regulated CAR-T cells, highlighting potential differences in downstream CAR signaling versus signaling through CD3 and CD28. Overall, these studies suggest that stem loops can be used to independently modulate expression of other transgenes in human CAR-T cells.

Discussion

Here we explore a new method of transgene modulation in human T cells by encoding stem loop sequences in the transgene 3′UTR to harness the endogenous activities of the regulatory RBPs Reg1 and Roq1. Methods to modulate transgene expression in T cells are of particular interest because they can be used to design novel or improved function in a therapeutic setting. Currently, major ways to control transgene function in T cells include use of small molecules or conditional logic systems.7,9,38−42 Small molecules are relatively simple to use, and their dose-dependent function is straightforward to characterize. However, the requirement for an external input to mediate regulatory function may not be optimal in all settings, such as those in which the conditions used to trigger regulation are difficult to know or observe. Indeed, laboratory tests typically generate results hours or even days after a sample is drawn from the patient, thus controlling therapeutic payloads in real time using small molecules switches may be especially challenging. Conditional logic systems can be used to overcome this limitation if conditions to trigger regulation are known a priori and can be encoded in biomolecular logic systems. However, many such systems require multiple components which can be challenging to integrate into lentiviral vectors due to the underlying transgene sizes and thus pose a limitation in both basic science and translational settings.

An alternative strategy to encode dynamic transgene regulation is to harness the dynamics of endogenous regulatory systems. While potentially promising, this strategy can also be challenging to implement because it requires1 understanding of the dynamics of the regulatory system and2 mechanistic understanding of how regulatory effects are achieved. In addition, many such systems are bespoke to specific cell types, limiting the portability of systems across different cell types and likely requiring unique engineering efforts for each desired cell chassis. Here we explore the potential of harnessing an endogenous regulatory system for restraining inflammatory gene expression as an orthogonal mechanism in T cells to repress transgene expression in resting T cells.

Notably, this exploration was enabled by the well-defined regulatory roles and mechanisms of Reg1 and Roq1 on transcripts encoding inflammatory factors in T cells. However, this system had other complexities since regulatory function was dependent on RNA secondary structure rather than sequence. Currently there are limited tools to comprehensively predict RNA secondary structure on a whole-transcript scale, limiting the ability to design stem loops that would confidently fold into the desired secondary structure in the context of an entire mRNA. Interestingly, we observed that manual design of stem loops proved to be successful in IVT and lentiviral settings, even when placed adjacent to the much larger WPRE secondary structure, indicating that design could be more straightforward than anticipated, at least for well-established stem loop structures.

Transgene modulation using stem loops worked well after TCR stimulation using anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, which is the endogenous mechanism for T cell activation and downstream repression of Reg1 and Roq1. However, stimulation through CAR019, a synthetic receptor designed to recapitulate 4–1BB and partial CD3 signaling, demonstrated more nuanced responses, especially when the CAR itself was the regulated transgene. While CARs are known to have idiosyncrasies in expression and surface recycling, differential responses may also underlie differences between TCR and CAR stimulation and make CAR activation not as adaptable for regulation mediated through stem loops targeted by Reg1 and Roq1. Various factors such as the costimulatory domains and binding domains used can influence the activation strength of a CAR, which may affect downstream Reg1 and Roq1 activity, thereby influencing the regulatory dynamics. As a result, whether any synthetic receptor can be adaptable for this type of modulation may require empirical evaluation.

Overall, we explore the use of stem loops targeted by Reg1 and Roq1 to dynamically modulate transgene expression in human T cells. Designed stem loops based on structures in natively regulated genes were able to modulate transgenes in a Reg1- and Roq1-dependent manner and enabled stimulation-specific transgene upregulation. Application in CAR-T cells demonstrated the potential for using stem loops to dampen or restrict payload expression to activated cells. Future work could explore other loops that mediate similar regulation in different contexts and the suitability of this regulatory system in other synthetic receptor architectures, including those that bear different costimulatory or binding domains.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Donna Gonzales for help with molecular cloning. The authors thank Dr. Kristen Lynch, Dr. Peter Choi, Dr. Regina Young, Dr. Evan Weber, Dr. Fyodor Urnov, and members of the June academic lab and TCEL for helpful discussions. The authors also thank Lynn Chen, Max Eldabbas, and Emileigh Maddox of the HIC at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania for providing purified human T cells. The HIC is supported in part by NIH P30 AI045008 and P30 CA016520. HIC RRID: SCR_022380.

Data Availability Statement

The constructs underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.4c00152.

Additional expression data on individual or additional human donors, flow cytometry plots, and knockout validation (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ P.C.R., N.C.S., and C.H.J. contributed equally. D.M.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. C.H.: Investigation. A.S.: Investigation. P.C.R.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing—review and editing. N.C.S.: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. C.H.J.: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

This work was supported by the Emerson Collective and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. D.M. is supported by the Fontaine Fellowship, the Norman and Selma Kron Endowed Fellowship, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Health Policy Research Scholars program, and the Centurion Foundation. Funding for open access charge: institutional funding.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): D.M., P.C.R., N.C.S., and C.H.J. are co-inventors on a provisional patent describing this system. N.C.S. is a scientific co-founder and holds equity in Bluewhale Bio, is a scientific advisor for Tome Biosciences and Pan Cancer T, and holds equity in Tmunity Therapeutics, and Pfizer Inc. C.H.J. is a scientific co-founder and holds equity in Capstan Therapeutics, Dispatch Biotherapeutics and Bluewhale Bio. C.H.J. serves on the board of AC Immune and is a scientific advisor to BluesphereBio, Cabaletta, Carisma, Cartography, Cellares, Cellcarta, Celldex, Danaher, Decheng, ImmuneSensor, Kite, Poseida, Verismo, Viracta, and WIRB-Copernicus group.

Special Issue

Published as part of ACS Synthetic Biologyspecial issue “Mammalian Cell Synthetic Biology”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Siddiqui M.; Tous C.; Wong W. W. Small molecule-inducible gene regulatory systems in mammalian cells: progress and design principles. Curr. Opin Biotechnol 2022, 78, 102823 10.1016/j.copbio.2022.102823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D. L.; Levine B. L.; Kalos M.; Bagg A.; June C. H. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J. Med. 2011, 365, 725–733. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp S. A.; Kalos M.; Barrett D.; Aplenc R.; Porter D. L.; Rheingold S. R.; Teachey D. T.; Chew A.; Hauck B.; Wright J. F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J. Med. 2013, 368, 1509–1518. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude S. L.; Frey N.; Shaw P. A.; Aplenc R.; Barrett D. M.; Bunin N. J.; Chew A.; Gonzalez V. E.; Zheng Z.; Lacey S. F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude S. L.; Laetsch T. W.; Buechner J.; Rives S.; Boyer M.; Bittencourt H.; Bader P.; Verneris M. R.; Stefanski H. E.; Myers G. D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melenhorst J. J.; Chen G. M.; Wang M.; Porter D. L.; Chen C.; Collins M. A.; Gao P.; Bandyopadhyay S.; Sun H.; Zhao Z.; et al. Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4(+) CAR T cells. Nature 2022, 602, 503–509. 10.1038/s41586-021-04390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E. W.; Lynn R. C.; Sotillo E.; Lattin J.; Xu P.; Mackall C. L. Pharmacologic control of CAR-T cell function using dasatinib. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 711–717. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018028720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J. H.; Watchmaker P. B.; Simic M. S.; Gilbert R. D.; Li A. W.; Krasnow N. A.; Downey K. M.; Yu W.; Carrera D. A.; Celli A. SynNotch-CAR T cells overcome challenges of specificity, heterogeneity, and persistence in treating glioblastoma. Sci. Transl Med. 2021, 13, eabe7378. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abe7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labanieh L.; Majzner R. G.; Klysz D.; Sotillo E.; Fisher C. J.; Vilches-Moure J. G.; Pacheco K. Z. B.; Malipatlolla M.; Xu P.; Hui J. H.; et al. Enhanced safety and efficacy of protease-regulated CAR-T cell receptors. Cell 2022, 185, 1745. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. S.; Wong N. M.; Tague E.; Ngo J. T.; Khalil A. S.; Wong W. W. High-performance multiplex drug-gated CAR circuits. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1294. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T.; Ma D.; Lu T. K. Sense-and-Respond Payload Delivery Using a Novel Antigen-Inducible Promoter Improves Suboptimal CAR-T Activation. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 1440–1453. 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D.; Tan A. H.; Hu X.; Athanasopoulos V.; Simpson N.; Silva D. G.; Hutloff A.; Giles K. M.; Leedman P. J.; Lam K. P.; et al. Roquin represses autoimmunity by limiting inducible T-cell co-stimulator messenger RNA. Nature 2007, 450, 299–303. 10.1038/nature06253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K.; Takeuchi O.; Standley D. M.; Kumagai Y.; Kawagoe T.; Miyake T.; Satoh T.; Kato H.; Tsujimura T.; Nakamura H.; et al. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature 2009, 458, 1185–1190. 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier S. J.; Athanasopoulos V.; Verloo P.; Behrens G.; Staal J.; Bogaert D. J.; Naesens L.; De Bruyne M.; Van Gassen S.; Parthoens E.; et al. A human immune dysregulation syndrome characterized by severe hyperinflammation with a homozygous nonsense Roquin-1 mutation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4779. 10.1038/s41467-019-12704-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens G.; Edelmann S. L.; Raj T.; Kronbeck N.; Monecke T.; Davydova E.; Wong E. H.; Kifinger L.; Giesert F.; Kirmaier M. E.; et al. Disrupting Roquin-1 interaction with Regnase-1 induces autoimmunity and enhances antitumor responses. Nat. Immunol 2021, 22, 1563–1576. 10.1038/s41590-021-01064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J.; Long L.; Zheng W.; Dhungana Y.; Lim S. A.; Guy C.; Wang Y.; Wang Y. D.; Qian C.; Xu B.; et al. Targeting REGNASE-1 programs long-lived effector T cells for cancer therapy. Nature 2019, 576, 471–476. 10.1038/s41586-019-1821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W.; Wei J.; Zebley C. C.; Jones L. L.; Dhungana Y.; Wang Y. D.; Mavuluri J.; Long L.; Fan Y.; Youngblood B.; et al. Regnase-1 suppresses TCF-1+ precursor exhausted T-cell formation to limit CAR-T-cell responses against ALL. Blood 2021, 138, 122–135. 10.1182/blood.2020009309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Liu Y.; Wang L.; Jin G.; Zhao X.; Xu J.; Zhang G.; Ma Y.; Yin N.; Peng M. Genome-wide fitness gene identification reveals Roquin as a potent suppressor of CD8 T cell expansion and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep 2021, 37, 110083 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai D.; Johnson O.; Reff J.; Fan T. J.; Scholler J.; Sheppard N. C.; June C. H. Combined disruption of T cell inflammatory regulators Regnase-1 and Roquin-1 enhances antitumor activity of engineered human T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2218632120 10.1073/pnas.2218632120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel K. U.; Edelmann S. L.; Jeltsch K. M.; Bertossi A.; Heger K.; Heinz G. A.; Zoller J.; Warth S. C.; Hoefig K. P.; Lohs C.; et al. Roquin paralogs 1 and 2 redundantly repress the Icos and Ox40 costimulator mRNAs and control follicular helper T cell differentiation. Immunity 2013, 38, 655–668. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehata T.; Iwasaki H.; Vandenbon A.; Matsushita K.; Hernandez-Cuellar E.; Kuniyoshi K.; Satoh T.; Mino T.; Suzuki Y.; Standley D. M.; et al. Malt1-induced cleavage of regnase-1 in CD4(+) helper T cells regulates immune activation. Cell 2013, 153, 1036–1049. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch K. M.; Hu D.; Brenner S.; Zoller J.; Heinz G. A.; Nagel D.; Vogel K. U.; Rehage N.; Warth S. C.; Edelmann S. L.; et al. Cleavage of roquin and regnase-1 by the paracaspase MALT1 releases their cooperatively repressed targets to promote T(H)17 differentiation. Nat. Immunol 2014, 15, 1079–1089. 10.1038/ni.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey A. D. Jr.; Schwab R. D.; Boesteanu A. C.; Steentoft C.; Mandel U.; Engels B.; Stone J. D.; Madsen T. D.; Schreiber K.; Haines K. M.; et al. Engineered CAR T Cells Targeting the Cancer-Associated Tn-Glycoform of the Membrane Mucin MUC1 Control Adenocarcinoma. Immunity 2016, 44, 1444–1454. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N.; Liu X.; Hulitt J.; Jiang S.; June C. H.; Grupp S. A.; Barrett D. M.; Zhao Y. Nature of tumor control by permanently and transiently modified GD2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells in xenograft models of neuroblastoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014, 2, 1059–1070. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner R. H.; Zhang X. Y.; Reiser J. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc 2009, 4, 495–505. 10.1038/nprot.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Wellhausen N.; Levine B. L.; June C. H. Production of Human CRISPR-Engineered CAR-T Cells. J. Vis Exp. 2021, 15 (169), 1. 10.3791/62299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppek K.; Schott J.; Reitter S.; Poetz F.; Hammond M. C.; Stoecklin G. Roquin promotes constitutive mRNA decay via a conserved class of stem-loop recognition motifs. Cell 2013, 153, 869–881. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino T.; Murakawa Y.; Fukao A.; Vandenbon A.; Wessels H. H.; Ori D.; Uehata T.; Tartey S.; Akira S.; Suzuki Y.; et al. Regnase-1 and Roquin Regulate a Common Element in Inflammatory mRNAs by Spatiotemporally Distinct Mechanisms. Cell 2015, 161, 1058–1073. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias D. A.; Violin J. D.; Newton A. C.; Tsien R. Y. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 2002, 296, 913–916. 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R.; Donello J. E.; Trono D.; Hope T. J. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J. Virol 1999, 73, 2886–2892. 10.1128/JVI.73.4.2886-2892.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C.; Baum B. J. All human EF1alpha promoters are not equal: markedly affect gene expression in constructs from different sources. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 404–408. 10.7150/ijms.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J. Y.; Zhang L.; Clift K. L.; Hulur I.; Xiang A. P.; Ren B. Z.; Lahn B. T. Systematic comparison of constitutive promoters and the doxycycline-inducible promoter. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10611 10.1371/journal.pone.0010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneru M.; Purdon T. J.; Spriggs D.; Koneru S.; Brentjens R. J. IL-12 secreting tumor-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells eradicate ovarian tumors in vivo. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e994446 10.4161/2162402X.2014.994446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn R. C.; Weber E. W.; Sotillo E.; Gennert D.; Xu P.; Good Z.; Anbunathan H.; Lattin J.; Jones R.; Tieu V.; et al. c-Jun overexpression in CAR T cells induces exhaustion resistance. Nature 2019, 576, 293–300. 10.1038/s41586-019-1805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers J. E.; Khan J. F.; Godfrey W. D.; Lopez A. V.; Ciampricotti M.; Rudin C. M.; Brentjens R. J. IL-18-secreting CAR T cells targeting DLL3 are highly effective in small cell lung cancer models. J. Clin Invest 2023, 133 (9), e166028. 10.1172/JCI166028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trisciuoglio D.; Tupone M. G.; Desideri M.; Di Martile M.; Gabellini C.; Buglioni S.; Pallocca M.; Alessandrini G.; D’Aguanno S.; Del Bufalo D. BCL-X(L) overexpression promotes tumor progression-associated properties. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, 3216. 10.1038/s41419-017-0055-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr A. L.; Mock A.; Gdynia G.; Schmitt N.; Heilig C. E.; Korell F.; Rhadakrishnan P.; Hoffmeister P.; Metzeler K. H.; Schulze-Osthoff K.; et al. Identification of BCL-XL as highly active survival factor and promising therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 875. 10.1038/s41419-020-03092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Y.; Roybal K. T.; Puchner E. M.; Onuffer J.; Lim W. A. Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor. Science 2015, 350, aab4077 10.1126/science.aab4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano-Attianese G.; Gainza P.; Gray-Gaillard E.; Cribioli E.; Shui S.; Kim S.; Kwak M. J.; Vollers S.; Corria Osorio A. J.; Reichenbach P.; et al. A computationally designed chimeric antigen receptor provides a small-molecule safety switch for T-cell therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 426–432. 10.1038/s41587-019-0403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roybal K. T.; Rupp L. J.; Morsut L.; Walker W. J.; McNally K. A.; Park J. S.; Lim W. A. Precision Tumor Recognition by T Cells With Combinatorial Antigen-Sensing Circuits. Cell 2016, 164, 770–779. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roybal K. T.; Williams J. Z.; Morsut L.; Rupp L. J.; Kolinko I.; Choe J. H.; Walker W. J.; McNally K. A.; Lim W. A. Engineering T Cells with Customized Therapeutic Response Programs Using Synthetic Notch Receptors. Cell 2016, 167, 419. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousley A. M.; Rotiroti M. C.; Labanieh L.; Rysavy L. W.; Kim W. J.; Lareau C.; Sotillo E.; Weber E. W.; Rietberg S. P.; Dalton G. N.; et al. Co-opting signalling molecules enables logic-gated control of CAR T cells. Nature 2023, 615, 507–516. 10.1038/s41586-023-05778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The constructs underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.