Abstract

Background

The link between regional body fat distribution and overactive bladder (OAB) in prior epidemiological research has been uncertain. Our objective is to assess the relationship between increased regional body fat and the prevalence of OAB.

Methods

Within this analysis, 8,084 individuals aged 20 years and older were selected from NHANES surveys conducted from 2011 to 2018. The evaluation of OAB symptoms utilized the overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS). Fat mass (FM) across various regions was quantified employing dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, which assessed total FM, trunk FM, arm FM, and leg FM. The fat mass index (FMI) was calculated as the ratio of fat mass (kg) to the square of height (meters). Data weighting was performed in accordance with analysis guidelines. A linear logistic regression model was employed to assess the correlation between regional FMI and the occurrence of OAB. Stratified analyses were also conducted.

Results

The study found significant associations between total FMI and limb FMI with OAB. After adjusting for all variables in the analysis, higher total FMI (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.02–1.12) was linked to an increased risk of OAB. Trunk FMI (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.03–1.22), arm FMI (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.20–2.10), and leg FMI (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.01–1.25) demonstrated significant correlations with OAB. The weighted associations between total FMI and limb FMI with OAB incidence showed no significant differences among most subgroups.

Conclusions

The data indicates a correlation between higher regional FMI and increased OAB risk across different populations.

Keywords: Overactive bladder, Regional body fat, NHANES, Fat mass index

Introduction

Overactive Bladder (OAB) is a condition marked by symptoms such as urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). This condition not only has a high prevalence worldwide but also significantly impacts patients’ quality of life, social functioning, and mental health [1–3]. Statistics show that the incidence of OAB increases with age, particularly among the elderly population [2, 4]. Although the exact etiology of OAB is not fully understood, current research suggests that multiple factors, including the nervous system, urinary system, muscle function, and metabolic abnormalities, could be significant contributors to its development [5–8].

Obesity, especially abnormal body fat distribution, is considered an important risk factor for OAB [9–12]. Most existing studies focus on the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and OAB [13]; however, BMI may not accurately represent the distribution of body fat. Regional body fat distribution, that is, the accumulation of fat in specific parts of the body, may have different impacts on the risk of OAB. Nevertheless, the epidemiological study results on the association between regional body fat and OAB are still unclear. Some studies suggest that abdominal fat accumulation may increase the risk of OAB by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and affecting bladder function [14, 15]. However, these studies often lack large-scale data support and have certain methodological limitations.

To fill this research gap, this study uses 2011–2018 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to delve into the link between fat mass (FM) across distinct body regions and OAB incidence. Using body fat data measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), we can precisely evaluate total FM, trunk FM, arm FM, and leg FM, and analyze the relationship between these regional fats and OAB. We hypothesize that there is a significant correlation between increased regional fat mass index (FMI) and the risk of OAB, which will help reveal the potential pathophysiological mechanisms of OAB and provide new insights for clinical prevention and treatment.

Methods

Study population

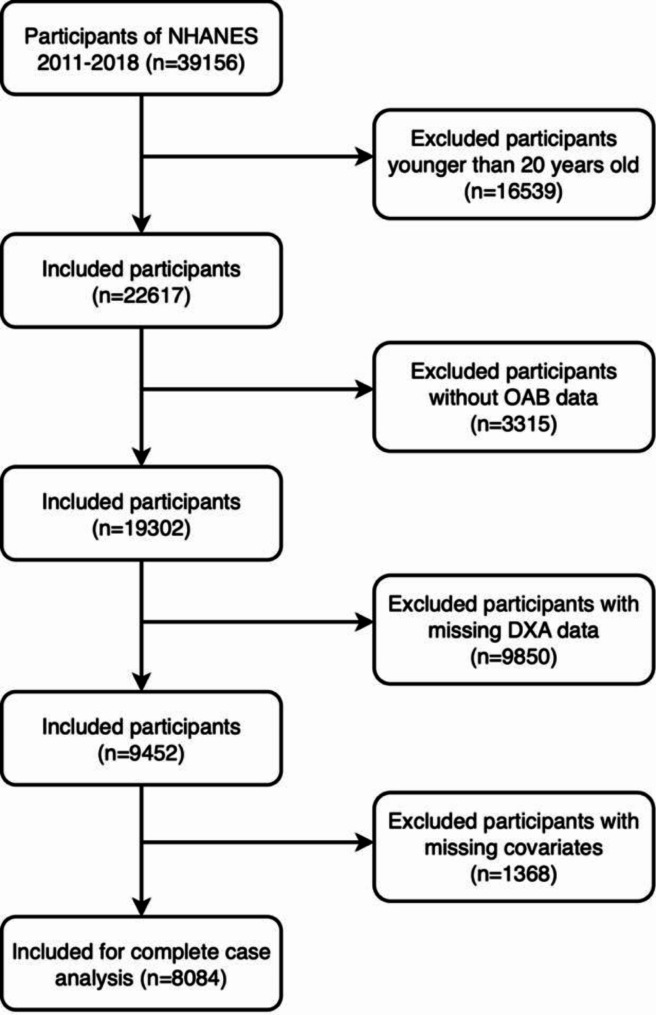

This cross-sectional study utilized NHANES data collected from 2007 to 2018. The NHANES database collects data every two years. Participants provided written informed consent following approval of the study by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board. Following relevant guidelines and regulations, a qualified research sample was selected from an initial pool of 39,156 candidates based on the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included individuals under 20 years of age (n = 16,539), individuals lacking key data related to the diagnosis of OAB (n = 3,315), individuals missing DXA data (n = 9,850), and individuals missing key covariate information (n = 1,368). Notably, among the 9,850 participants lacking DXA data, 6,657 were individuals aged 59 and above who were not subjected to DXA scans. Ultimately, this study included 8,084 eligible participants for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The participant flow diagram

Calculation of fat mass index

Participants aged 8–59 underwent whole-body DXA scans conducted by trained operators. Exclusions were made for pregnant individuals, those who reported recent use of radiographic contrast agents (barium) within the past 7 days, or those with self-reported weights exceeding 450 pounds or heights over 6 feet 5 inches. Scanning was performed using the Hologic Discovery A densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA, USA). All DXA scans required quality control and analysis to measure soft tissue and skeletal components of different body parts. The analysis covered FM, along with FM in both arms, legs, and trunk. Arm and leg FM were summed across both limbs. The FMI was computed by dividing FM (kg) by the square of height (m²).

Diagnosis of OAB

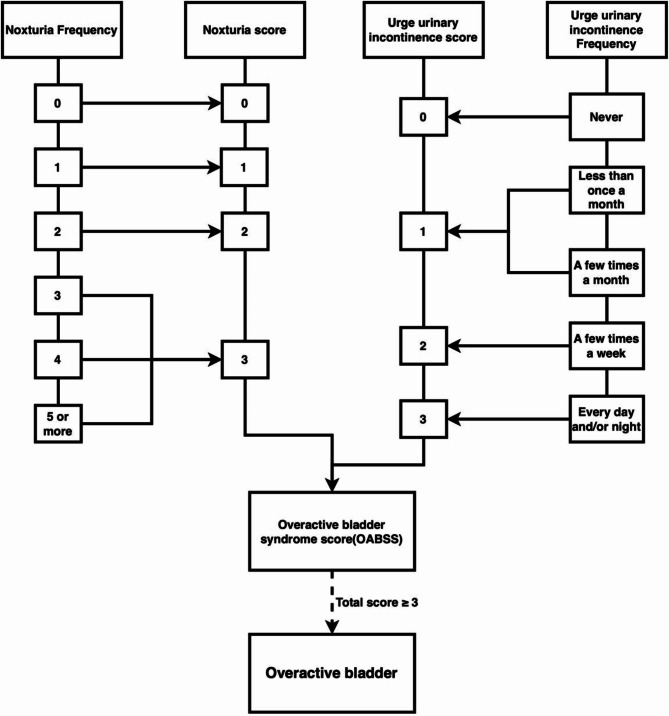

OAB is defined as a condition characterized by urinary frequency, UUI, and nocturia. In this study, data were collected by professionally trained researchers through face-to-face interviews and questionnaires. UUI assessment relied on the participant’s response to the question: “In the last 12 months, have you experienced leaking urine due to an uncontrollable urge or pressure to urinate, and were unable to reach the toilet in time?” Additionally, the severity of the condition was assessed by asking “How often did this happen?” Nocturia was evaluated by asking “Over the last 30 days, how often did you typically wake up at night to urinate while sleeping?” Furthermore, the overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS) was used to quantify the severity of OAB, with a score of 3 or above considered indicative of OAB (Fig. 2) [16].

Fig. 2.

Flowchart for diagnosing overactive bladder syndrome based on overactive bladder syndrome scores

Definition of covariates

In this study, we included a series of known covariates related to regional FMI and OAB risk, divided into three main categories: demographic indicators, lifestyle factors, and health status. Demographic indicators included age, sex, race, marital status, education level, and poverty rate. Lifestyle factors covered alcohol consumption (categorized as lifetime abstainers with fewer than 12 drinks ever, former drinkers with 12 or more drinks in the past but none in the last year, and current drinkers with 12 or more drinks ever and at least one drink in the past year) [17], smoking status (dependent on whether the individual smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), sedentary time (defined as sitting for more than 5 h a day), and physical activity level (assessed by the duration of moderate to vigorous activity lasting at least 10 min per week, with less than 10 min defined as inactive, excluding daily work and commuting tasks) [18]. Health indicators were collected through standard questionnaires and clinical assessments and included BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) status.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we considered NHANES sampling weights to calculate estimates for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were analyzed by presenting weighted means and standard errors, while categorical variables were examined using weighted counts and proportions. Weighted linear regression and chi-square tests were applied for the analysis of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. To explore the relationship between regional FMI and the occurrence of OAB, we used multivariable logistic regression models to calculate ORs and their associated 95% CIs for regional FMI in relation to OAB occurrence. Crude model was an unadjusted model; Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, marital status, and poverty rate; and Model 2 further accounted for smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, eGFR, sedentary time, physical activity level, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. Additionally, we used restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression models to assess the dose-response relationship between regional FMI and OAB risk, and subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the consistency of our findings across various demographic characteristics and health statuses. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

This study selected 8,084 participants from four cycles of the NHANES database (2011–2018), dividing them into groups diagnosed with OAB and those not diagnosed with OAB. Table 1 displays the participants’ mean age as 39.06 ± 0.28 years. Among these participants, 887 were diagnosed with OAB. Compared to participants not diagnosed with OAB, those diagnosed with OAB were generally older, had a higher proportion of females and non-Hispanic Blacks, were more likely to be single (divorced/separated/widowed), had lower education levels, lower poverty rate, higher BMI, were more likely to smoke or have a history of alcohol consumption, tended towards inactive lifestyles, had shorter sedentary times, tended to have lower eGFR, and were more likely to have a history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. Additionally, participants diagnosed with OAB had higher levels of total FMI, trunk FMI, arm FMI, and leg FMI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population by OAB

| Variable | Overall (n = 8084) | Without OAB (7197) | With OAB (887) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SE) | 39.06(0.28) | 38.45(0.30) | 45.12(0.41) | < 0.0001 |

| Sex, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Female | 3945(48.07) | 3367(46.40) | 578(64.89) | |

| Male | 4139(51.93) | 3830(53.60) | 309(35.11) | |

| Race, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Mexican American | 1201(10.21) | 1077(10.23) | 124(9.94) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2977(63.42) | 2691(64.11) | 286(56.48) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1596(10.22) | 1316(9.33) | 280(19.16) | |

| Other Hispanic | 804(6.88) | 703(6.80) | 101(7.62) | |

| Other Race | 1506(9.27) | 1410(9.52) | 96(6.80) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 1088(12.84) | 887(12.06) | 201(20.71) | |

| Married/Living with a partner | 4852(62.22) | 4385(62.65) | 467(57.88) | |

| Never married | 2144(24.94) | 1925(25.29) | 219(21.41) | |

| Education levels, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| High school and below | 3068(33.03) | 2625(31.87) | 443(44.73) | |

| Above high school | 5016(66.97) | 4572(68.13) | 444(55.27) | |

| Poverty ratio, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| <1.3 | 2534(22.28) | 2121(20.90) | 413(36.20) | |

| 1.3–3.5 | 2928(35.00) | 2636(35.02) | 292(34.84) | |

| >3.5 | 2622(42.71) | 2440(44.08) | 182(28.96) | |

| BMI, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| <25 | 2566(31.56) | 2383(32.46) | 183(22.53) | |

| 25-29.99 | 2618(33.42) | 2391(34.02) | 227(27.39) | |

| ≥30 | 2900(35.02) | 2423(33.52) | 477(50.08) | |

| Smoke, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 4896(58.96) | 4452(59.99) | 444(48.59) | |

| Yes | 3188(41.04) | 2745(40.01) | 443(51.41) | |

| Alcohol user, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Never | 1024(9.28) | 888(8.93) | 136(12.82) | |

| Former | 725(8.00) | 604(7.43) | 121(13.75) | |

| Now | 6335(82.72) | 5705(83.64) | 630(73.43) | |

| Recreational activity, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Inactive | 3510(39.03) | 3009(37.57) | 501(53.70) | |

| Active | 4574(60.97) | 4188(62.43) | 386(46.30) | |

| Sitting time, n (%) | 0.01 | |||

| <5 | 2932(33.33) | 2566(32.75) | 366(39.13) | |

| ≥5 | 5152(66.67) | 4631(67.25) | 521(60.87) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| No | 6271(78.49) | 5733(79.98) | 538(63.48) | |

| Yes | 1813(21.51) | 1464(20.02) | 349(36.52) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| No | 7363(93.01) | 6662(94.02) | 701(82.81) | |

| Borderline | 147(1.62) | 118(1.48) | 29(3.02) | |

| Yes | 574(5.37) | 417(4.50) | 157(14.17) | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| No | 3055(38.06) | 2823(39.25) | 232(26.03) | |

| Yes | 5029(61.94) | 4374(60.75) | 655(73.97) | |

| CVD, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| No | 8022(99.43) | 7159(99.56) | 863(98.03) | |

| Yes | 62(0.57) | 38(0.44) | 24(1.97) | |

| eGFR (mL/min), mean (SE) | 101.76(0.40) | 102.03(0.42) | 99.01(0.95) | 0.003 |

| Total FMI (kg/m²), mean (SE) | 9.68(0.08) | 9.47(0.08) | 11.81(0.22) | < 0.0001 |

| Trunk FMI (kg/m²), mean (SE) | 4.65(0.05) | 4.54(0.05) | 5.77(0.12) | < 0.0001 |

| Arm FMI (kg/m²), mean (SE) | 1.18(0.01) | 1.15(0.01) | 1.51(0.03) | < 0.0001 |

| Leg FMI (kg/m²), mean (SE) | 3.44(0.03) | 3.37(0.03) | 4.11(0.08) | < 0.0001 |

OAB, Overactive bladder; eGFR, Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; BMI, Body mass index; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; FMI, Fat mass index

Association between regional FMIs and OAB

Table 2 shows the correlation between regional FMIs and OAB. In the crude model, for each unit increase in total FMI, the OR for OAB increased (OR = 1.12, 95%[CI]: 1.09–1.14, P < 0.0001). The OR for OAB also increased with each unit increase in trunk and limb FMI, respectively, 1.23 (95%[CI]:1.18–1.28), 2.20 (95%[CI]:1.93–2.50), and 1.29 (95%[CI]:1.22–1.35). Even in Model 2, which adjusted for all covariates, this significant positive correlation persisted. For each unit increase in total FMI and regional FMI, the risk of OAB significantly increased, with ORs of 1.07 (95%[CI]:1.02–1.12), 1.12 (95%[CI]:1.03–1.22), 1.59 (95%[CI]:1.20–2.10), and 1.12 (95%[CI]:1.01–1.25), respectively.

Table 2.

Association of different regional body fat with OAB

| Exposure | Crude model | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Total FMI (kg/m²) | 1.12(1.09,1.14) | < 0.0001 | 1.08(1.05,1.11) | < 0.0001 | 1.07(1.02,1.12) | 0.01 |

| Trunk FMI (kg/m²) | 1.23(1.18,1.28) | < 0.0001 | 1.15(1.10,1.21) | < 0.0001 | 1.12(1.03,1.22) | 0.01 |

| Arm FMI (kg/m²) | 2.20(1.93,2.50) | < 0.0001 | 1.75(1.48,2.06) | < 0.0001 | 1.59(1.20,2.10) | 0.002 |

| Leg FMI (kg/m²) | 1.29(1.22,1.35) | < 0.0001 | 1.19(1.11,1.27) | < 0.0001 | 1.12(1.01,1.25) | 0.03 |

Crude model: unadjusted model; Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex, race, education levels, marital status, poverty ratio; Model 2: Additionally adjusted for BMI, smoking, alcohol user, recreational activity, sitting time, eGFR, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and CVD. OAB, overactive bladder; FMI, Fat mass index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

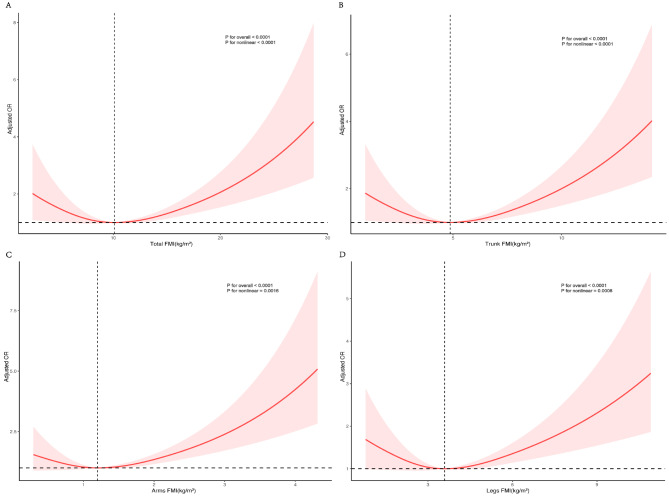

Restricted cubic spline analysis

In the RCS regression, after adjusting for covariates, a significant non-linear association was found between total FMI and regional FMI with OAB (non-linearity P < 0.01). Figure 3 A-D show that total FMI, trunk FMI, arm FMI, and leg FMI all had an inverted U-shaped relationship with OAB.

Fig. 3.

Correlation Between Regional FMI and Incidence of OAB. This figure displays the relationships between Total FMI (A), Trunk FMI (B), Arm FMI (C), and Leg FMI (D) and the incidence of OAB. The red solid lines represent the adjusted ORs, which quantify the association between increases in regional FMI and the likelihood of developing OAB. These ORs are adjusted for factors including age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education level, poverty ratio, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, recreational activity, sitting time, eGFR, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. The shaded areas surrounding each red line indicate the 95% confidence intervals, providing a visual estimate of the range within which the true values of the ORs are likely to fall, highlighting the precision and reliability of these estimates

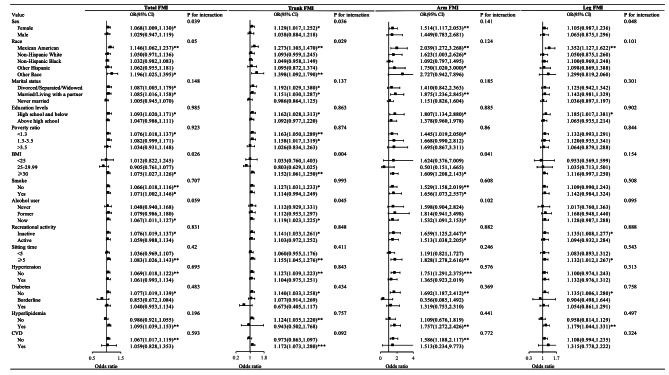

Subgroup analysis

As shown in Fig. 4, the subgroup analysis revealed variations in the correlation between total FMI and regional FMI with the risk of OAB among different populations. In the fully adjusted multivariable model (excluding the stratifying factor itself), the relationship between total FMI and regional FMI with OAB did not show significant differences among most subgroups (P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Presents a stratified analysis of different regional body fat and OAB. This analysis took into account adjustments for a range of factors including age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education levels, poverty ratio, BMI, smoking, alcohol user, recreational activity, sitting time, eGFR, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and CVD. *: 0.01 < p < 0.05, **: 0.001 < p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

Discussion

This study analyzed NHANES data to clarify the significant association between total FMI and regional FMIs (trunk FMI, arm FMI, and leg FMI) with OAB. We found that increases in total FMI and regional FMIs significantly increased the risk of OAB. This finding indicates that not only overall obesity but also the distribution of fat in different body regions significantly affects the risk of OAB. Even after adjusting for multiple confounding factors, these results remained statistically significant, indicating the robust independence of the relationship between regional body fat and OAB.

Adipose tissue functions not just as an energy storage unit but also as an active endocrine organ, releasing diverse metabolically active substances like leptin, adiponectin, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [19, 20]. These substances regulate systemic metabolic processes and may affect bladder function through various pathways. Obese individuals have elevated leptin levels and decreased adiponectin levels in their blood [21–23]. Leptin and adiponectin not only affect energy balance and insulin sensitivity but may also influence bladder function directly by acting on bladder smooth muscle cells or indirectly through the central nervous system [24–26]. Increased leptin levels may lead to abnormal contraction of the detrusor muscle, causing OAB symptoms [27]. Chronic low-grade inflammation linked to obesity might also contribute significantly to the pathophysiology of OAB. Inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-6 can activate various inflammatory signaling pathways, potentially leading to abnormal bladder smooth muscle and nerve function, resulting in symptoms such as urgency and frequency [28, 29].

Trunk fat accumulation (especially abdominal fat) is associated with metabolic syndrome and may mechanically increase intra-abdominal pressure, affecting bladder storage function [30]. Increased intra-abdominal pressure may reduce bladder capacity and promote abnormal detrusor activity, thereby increasing the risk of OAB. Additionally, abdominal fat accumulation may increase intra-abdominal inflammation levels, further affecting bladder function [31]. While arm and leg fat accumulation may have a smaller direct impact on intra-abdominal pressure, their metabolic and endocrine functions are equally important [32]. Limb fat accumulation may affect the overall metabolic state by secreting various metabolically active substances, indirectly influencing bladder function [33]. Moreover, limb fat accumulation may reflect overall obesity, which is also associated with the risk of OAB.

The distribution of adipose tissue may affect bladder activity by influencing the autonomic nervous system function. Studies have shown that obesity is associated with an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, both of which play vital roles in regulating bladder function [34, 35]. Specifically, abdominal fat accumulation may stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to hyperactivity of the detrusor muscle and causing OAB symptoms [36]. Additionally, obesity may affect the pelvic nervous system, altering bladder sensory and motor functions [37, 38].

Our study found that female participants were more likely to develop OAB, which may be related to gender differences. Women are generally more likely than men to accumulate fat in the abdomen and lower limbs, which may lead to a higher susceptibility to the effects of regional body fat, increasing the risk of OAB [39, 40]. Moreover, hormonal fluctuations in women, particularly the decline in estrogen levels after menopause, may also affect fat distribution and bladder function, increasing the incidence of OAB [41, 42].

In our study, while most subgroups did not show significant differences in the incidence of OAB, individual subgroup analyses revealed notable exceptions, particularly among females and those categorized as ‘other races’, along with individuals with a higher BMI. These specific findings underline the importance of targeted clinical strategies to address these disparities. Personalized treatment approaches that consider these subgroup-specific susceptibilities could potentially enhance the management of OAB. For instance, interventions tailored to address the unique physiological and hormonal characteristics of women, culturally adapted strategies for diverse racial groups, and weight management programs aimed at reducing body fat in obese patients may significantly improve therapeutic outcomes.

The findings of this study carry significant clinical implications. First, measuring body fat distribution can be part of OAB risk assessment, providing a basis for early intervention in high-risk populations. For individuals with high regional body fat distribution, lifestyle interventions, nutritional adjustments, and appropriate physical activity can reduce the risk of OAB. Second, targeted reduction of trunk and limb fat accumulation may become a new strategy for preventing and treating OAB. Finally, understanding the relationship between regional body fat and OAB can help clinicians consider individual body fat distribution characteristics when treating OAB, allowing for more personalized treatment plans. For example, patients with high abdominal fat may need more aggressive lifestyle interventions and medication to reduce the occurrence and severity of OAB symptoms.

Although this study has several strengths, such as using a large sample size of NHANES data and accurate body fat measurements from DXA, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the study design precludes us from establishing causal relationships. While we have identified significant associations, the cross-sectional data only reflect a single moment in time, making it challenging to ascertain whether increased body fat precedes OAB or results from lifestyle changes following OAB diagnosis. This limitation is critical in interpreting our findings as indicative of potential links rather than direct causative pathways. Secondly, our use of DXA for measuring body fat does not allow us to distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral fat. This is a significant limitation given that these fat types are metabolically distinct and may differentially impact health. Visceral fat is often more closely linked with metabolic and inflammatory disturbances that could influence OAB, whereas subcutaneous fat might have less of a direct impact on the condition. The inability to differentiate between these fat depots limits our understanding of the specific pathways through which body fat may influence OAB and restricts the generalizability of our findings to broader implications about body fat distribution. Third, while our study employed rigorous statistical controls to adjust for a comprehensive range of confounding factors, the potential for residual confounding remains a concern. This may stem from unmeasured or imprecisely measured variables that could influence the observed relationships between regional body fat and overactive bladder symptoms. Additionally, the use of NHANES data, while providing a robust sample size and diverse demographic representation within the United States, does pose limitations in terms of global applicability. The findings derived from this dataset predominantly reflect the health dynamics of the U.S. population and may not be directly generalizable to other countries with different cultural, dietary, and healthcare landscapes. Lastly, our analysis, which reveals associations between regional and total body fat indices and the presence of OAB symptoms, must be interpreted with caution. It is essential to understand that these associations do not establish causality due to the intricate and multifaceted nature of OAB. The condition comprises various subtypes, each potentially driven by unique mechanisms influenced by body fat distribution. For example, increased abdominal fat may heighten intra-abdominal pressure, exacerbating symptoms such as urgency and frequency. This mechanical effect could influence bladder outlet obstruction differently compared to how metabolic factors associated with obesity might affect detrusor overactivity or bladder hypersensitivity.

To deepen our understanding of how regional body fat contributes to OAB, it is imperative that future studies delve into the molecular and physiological pathways potentially mediating this relationship. Investigating the roles of adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin, which are significantly modulated by body fat distribution, could provide critical insights. Leptin, often elevated in individuals with higher amounts of visceral fat, has been implicated in promoting inflammation and may influence bladder signaling pathways, potentially exacerbating OAB symptoms. Conversely, adiponectin, typically lower in individuals with obesity, could play a protective role that might be compromised in the presence of OAB. Additionally, accurate differentiation between subcutaneous and visceral fat is essential for clarifying their respective impacts on OAB. Advanced imaging techniques such as MRI or CT scans should be employed to precisely correlate specific fat depots with OAB prevalence and severity, thereby providing a clearer picture of the causal relationships. Integrating these findings with longitudinal studies that track changes in body fat and OAB symptoms over time is crucial. Such studies would not only validate the associations found in cross-sectional studies like ours but also help establish a temporal sequence of events. This approach will clarify whether changes in body fat distribution precede the development of OAB or occur as a consequence of the condition. Moreover, expanding this research to include non-U.S. populations is vital. It will enhance the external validity of our results and provide insights into the global applicability of our findings, ensuring that our research contributions are relevant and beneficial for diverse demographic settings. By aligning these approaches, future research can effectively address the gaps identified in our study, offering a comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between body fat distribution and OAB. We believe this integrated approach will substantially contribute to the field, guiding targeted interventions and informing clinical management strategies for OAB influenced by body fat.

In summary, this study uncovered a noteworthy link between regional body fat and OAB risk through the analysis of extensive epidemiological data. These findings not only enrich our understanding of the etiology of OAB but also provide new ideas for clinical prevention and treatment. Future research should continue to explore the mechanisms of regional body fat and verify these results in different populations to further advance the prevention and treatment of OAB.

Conclusions

This study, based on NHANES data, detected a noteworthy correlation between regional body fat and OAB. The overall FMI and the FMI of various limbs were positively correlated with the risk of OAB, a relationship that was consistently observed across different populations. This finding highlights the close link between body fat and OAB, providing important insights for future research and interventions.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the NHANES databases for granting access to this invaluable data.

Author contributions

DYZ, HHJ, YJQ: Contributed to paper design and data processing. YQ, HR: Involved in data collection. DQX, GB: Drafted the manuscript. CY, GJ: Revised the manuscript.

Funding

Science and Technology Department Foundation of Jiangxi Province (No: 20202BBGL73090).

Data availability

All data used in this study are available in the NHANES database, accessible at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Consent for publication

Relevant data from participants were collected from the publicly accessible NHANES database, eliminating the need for obtaining additional consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuan-Zhuo Du, Hong-Ji Hu and Jia-Qing Yang contributed equally to this work as Co-first author.

Contributor Information

Ying Cao, Email: 1251704690@qq.com.

Ju Guo, Email: ndyfy02371@ncu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Coyne KS, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104(3):352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin DE et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol, 2006;50(6):1306-14; discussion 1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Coyne KS, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101(11):1388–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20(6):327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB. Neurophysiology of lower urinary tract function and dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(Suppl 8):S3–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osman NI, Chapple CR. Contemporary concepts in the aetiopathogenesis of detrusor underactivity. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(11):639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steers WD, Tuttle JB. Mechanisms of Disease: the role of nerve growth factor in the pathophysiology of bladder disorders. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2006;3(2):101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillespie JI. The autonomous bladder: a view of the origin of bladder overactivity and sensory urge. BJU Int. 2004;93(4):478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagovska M, et al. The relationship between overweight and overactive bladder symptoms. Obes Facts. 2020;13(3):297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagovska M, et al. Comparison of body composition and overactive bladder symptoms in overweight female university students. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;237:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subak LL, et al. Weight loss: a novel and effective treatment for urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005;174(1):190–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings JM, Rodning CB. Urinary stress incontinence among obese women: review of pathophysiology therapy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2000;11(1):41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez M, Ortiz AP, Vargas R. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and its association with body mass index among women in Puerto Rico. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(10):1607–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gacci M, et al. Central obesity is predictive of persistent storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) after surgery for benign prostatic enlargement: results of a multicentre prospective study. BJU Int. 2015;116(2):271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai HH, et al. Relationship between central obesity, General Obesity, overactive bladder syndrome and urinary incontinence among male and female patients seeking care for their lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 2019;123:34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu S, et al. Relationship between Marijuana Use and overactive bladder (OAB): a cross-sectional research of NHANES 2005 to 2018. Am J Med. 2023;136(1):72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hicks CW, et al. Peripheral neuropathy and all-cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in U.S. adults: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasquez E, et al. Impact of obesity and physical activity on functional outcomes in the elderly: data from NHANES 2005–2010. J Aging Health. 2014;26(6):1032–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fain JN. Release of interleukins and other inflammatory cytokines by human adipose tissue is enhanced in obesity and primarily due to the nonfat cells. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:443–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. Leptin: a pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(3):S980–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Considine RV, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(5):292–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastard JP, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(9):3338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara T, et al. Decreased plasma adiponectin levels in young obese males. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003;10(4):234–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahima RS, et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382(6588):250–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamauchi T, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7(8):941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395(6704):763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanca AJ, et al. Leptin induces oxidative stress through activation of NADPH oxidase in renal tubular cells: antioxidant effect of L-Carnitine. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(10):2281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang YH, et al. Increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, C-reactive protein and nerve growth factor expressions in serum of patients with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, et al. Inhibition of TNF-alpha improves the bladder dysfunction that is associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61(8):2134–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang B, et al. Relationships between body fat distribution and metabolic syndrome traits and outcomes: a mendelian randomization study. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(10):e0293017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang JW, et al. Metabolic syndrome and abdominal fat are associated with inflammation, but not with clinical outcomes, in peritoneal dialysis patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu W, et al. The myokine CCL5 recruits subcutaneous preadipocytes and promotes intramuscular fat deposition in obese mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;326(5):C1320–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cnop M, et al. The concurrent accumulation of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous fat explains the association between insulin resistance and plasma leptin concentrations: distinct metabolic effects of two fat compartments. Diabetes. 2002;51(4):1005–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo B et al. Autonomic nervous system in obesity and insulin-resistance-the Complex interplay between Leptin and Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci, 2021;22(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Roy HA, Green AL. The Central Autonomic Network and Regulation of bladder function. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim KH, et al. Nonselective blocking of the sympathetic nervous system decreases detrusor overactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(4):5048–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayaraman A, Lent-Schochet D, Pike CJ. Diet-induced obesity and low testosterone increase neuroinflammation and impair neural function. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malykhina AP, et al. VEGF induces sensory and motor peripheral plasticity, alters bladder function, and promotes visceral sensitivity. BMC Physiol. 2012;12:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Power ML, Schulkin J. Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism, and the health risks from obesity: possible evolutionary origins. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(5):931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellissimo MP, et al. Sex differences in the relationships between body composition, fat distribution, and mitochondrial energy metabolism: a pilot study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2022;19(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurylowicz A. Estrogens in adipose tissue physiology and obesity-related dysfunction. Biomedicines, 2023;11(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Weber MA, et al. Local Oestrogen for Pelvic Floor disorders: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0136265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available in the NHANES database, accessible at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.