Abstract

Background

Angiosarcoma is a rapidly proliferating vascular tumor that originates in endothelial cells of vessels. Rarely, it can be associated with consumptive coagulopathy due to disseminated intravascular coagulation eventually leading to thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. This specific manifestation is termed Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. Patients usually present with manifestations related to the primary diagnosis of angiosarcoma depending on the organ it is involving. However, if Kasabach–Merritt syndrome has occurred, it will present with manifestations such as bleeding and thromboembolic phenomenon. To date, no favorable outcomes have been documented, and the overall prognosis remains grim.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old male patient of Afghan origin developed typical signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, that is, fever, cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, and night sweats. He was initially managed in an Afghan medical facility where workup for tuberculosis was done but came back negative. He empirically received anti-tuberculous therapy owing to typical presentation and tuberculosis being endemic in the area. The condition of the patient worsened, and he presented to our facility (Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan). Workup led to the diagnosis of a metastatic vascular neoplasm, which was further complicated with consumptive coagulopathy, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. This presentation is known as Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. Multidisciplinary team discussion was called, and it was decided to proceed with palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel.

Conclusion

Although a patient may present with typical signs and symptoms of, but negative workup for, TB, if there is a high index of suspicion and the patient is receiving empirical treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis, clinical worsening should alert to think about differential diagnosis. In our case, histopathological analysis of lymph node and radiological findings led us to the diagnosis.

Keywords: Angiosarcoma, Kasabach–Merritt syndrome, Thrombocytopenia, Consumptive coagulopathy, Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA)

Introduction

Kasabach–Merritt syndrome (KMS) is characterized by thrombocytopenia and hyperconsumption of coagulation factors within a vascular tumor [2]. The association of vascular tumors, thrombocytopenia, and hypofibrinogenemia was first discovered by Kasabach and Merritt in 1940 [3], who took care of a boy with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, severe thrombocytopenia, anemia, and consumption coagulopathy. Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (KMP) with angiosarcoma was later detected in the skin [4], breast [5], and bone [6]. There are 72 case reports of KMS to date. Of those, 43 cases were associated with hemangioma, 16 with Kaposi hemangioendothelioma/tufted angioma, 8 with angiosarcoma, 2 with lymphangioma, 2 with angiolipoma, and 1 with Merkel cell carcinoma [2]. Case reports now show that Kasabach–Merritt syndrome is most commonly associated with vascular tumors of hepatic origin, hepatic angiosarcoma being one of them. Hepatic angiosarcoma is a malignant mesenchymal tumor with very low incidence of 0.14–0.25 per million inhabitants, representing 1.8% of all primary liver tumors [3]. Abdominal pain is the most common complaint, followed next by weakness, fatigue, and weight loss [7]. The clinical entity of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome (KMS) is indistinguishable from Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) by blood-based laboratory findings. The coagulopathy associated with KMS is characterized by hyperactivation of the coagulation cascade and entrapment of platelets within dilated sinusoids of the vascular tumor [10]. Unexplainable DIC may be a clue in identifying hepatic tumors of vascular origin [1]. The average lifespan after diagnosis has been reported to be 6 months [8]. An attempt of surgical resection or liver transplant does not provide significant advantage in extending life, as the tumor recurs in nearly all cases reported [9]. In addition, there are no well-established chemotherapy regimens, and accordingly, this has been primarily utilized as a palliative measure [9]. We present herein a unique case of angiosarcoma associated with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome that presented initially with typical signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis in a TB-endemic area.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old male, resident of Afghanistan, developed a cough that was initially dry for 5–6 weeks and later became productive. About 2 months after onset of symptoms, he experienced hemoptysis, which was about two tablespoons every day. This is when the patient got worried and approached a medical facility in his hometown. Upon detailed inquiry, it was revealed that the patient also had a low-grade fever, which he was experiencing nearly daily or on every alternate day and that was associated with sweating but no rigors or chills. He also had weight loss of 6 kg (8% of his body weight) in a span of 2 months. He also experienced moderately severe epigastric pain that radiated to the right side of the abdomen and was one of the most bothersome symptoms for him, being present for around the last 1.5 months. Additionally, the patient had vague lower back pain that was mild and was present for the last 1 month. He had no known comorbidity, but his past medical history was significant for enteric fever around 15 years ago, which was treated at that time. He had no surgical history. He was a shopkeeper by profession. He was married and a father of two children.

Investigations done in Afghanistan were all normal except for an eosinophil count of 20% with a total leukocyte count of 12,000/UL (4000–11000/UL), platelet count of 210,000/UL (150,000–400000/UL), and hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL (13–18 g/dL). A high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed and showed bilateral nodular infiltrates along with mediastinal and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Further workup was not done at that time, and he was treated with steroids for eosinophilic pulmonary disease owing to high eosinophil count, to which he did not respond at all.

Thorough workup for tuberculosis was then conducted in the Afghan medical facility, which included MTB GeneXpert PCR and interferon gamma release assay, both of which were negative. Typical signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, with the patient living in a TB-endemic area, led to a high index of suspicion, and he was treated for pulmonary TB with Anti Tuberculous Therapy (ATT) for 1 month. Instead of improving, his symptoms worsened over time. He was now experiencing severe bouts of cough, and hemoptysis also worsened. He also experienced a further weight loss of 4 kg over these 2 months.

The patient eventually presented to our facility after being on ATT for a month, initially visiting the gastroenterology outpatient department (OPD) for epigastric pain. Detailed history was obtained, and a physical examination was done, revealing diffuse crackles in the chest, mildly tender hepatomegaly, and tenderness on lower back. Owing to unrelated symptoms being present in different regions of the body, CT scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis was done and revealed patchy pulmonary nodular infiltrates, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and lesions in multiple levels of the spine. The largest lymph node was present in subcarinal location, being 16 mm in short axis. The pulmonology team was consulted at this time. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting with a gastroenterologist, pulmonologist, and infectious disease consultant was called, and it was decided to proceed with subcarinal lymph node biopsy. An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided subcarinal lymph node biopsy was performed and sent for histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Histopathology showed fragmented cores showing infiltrative dyshesive atypical cells with pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei forming slit-like spaces, and vague hob nailing. Immunohistochemistry showed CKAE1/3 negative, CD30 negative, SALL4 negative, and CD20 negative. All of the above findings favored a diagnosis of atypical vascular neoplasm, favoring angiosarcoma. At this time, an oncologist was consulted, and it was decided to proceed with a bone scan, which showed increased radiotracer uptake in multiple levels of spine DV8, LV2, LV5, left scapula, 6th and 7th ribs on the right, head and proximal shaft of the right humerus, and pelvic bones. Meanwhile, his hemoglobin level dropped from 12.5 g/dL (in Afghanistan) to 8.2 g/dL, and his platelet level dropped from 210,000/UL to 57,000/UL which was very concerning, and a hematologist was consulted at this point. Workup for disseminated intravascular coagulation was done and showed prothrombin time of 30 s and activated partial thromboplastin time of 66 s, and their peripheral smear showed 6–8 schistocytes per high-power field with platelets decreased on film. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) was 312 U/L (135–225 U/L), and fibrinogen was 112 mg/dL (200-400 mg/dL). All this workup suggested DIC with consumptive coagulopathy and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, suggesting Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. A multidisciplinary team meeting was again called, and this time a pulmonologist, oncologist, hematologist, radiation oncologist, and radiologist were all involved. It was mutually decided to start the patient on palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel.

Clinical findings

On physical examination, the patient had diffuse crackles on respiratory examination. He had some tenderness in the right upper quadrant along with hepatomegaly, and his lower back was also moderately tender. No other significant physical finding could be appreciated.

Timeline

January 14, 2022: patient first presented to a medical facility in Afghanistan.

January 16, 2022: patient was started on steroids empirically for eosinophilic pulmonary disease.

February 10, 2022: patient again presented to the medical facility in Afghanistan with worsening symptoms, and workup for tuberculosis was done.

February 13, 2022: initial workup for tuberculosis came back negative, culture was awaited, and he was started empirically on ATT.

March 25, 2022: Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) culture came back negative. Also, the patient had persistent worsening of symptoms and was therefore referred to Shifa International Hospital for further workup and management.

March 28, 2022: patient visited our gastroenterology outpatient department; CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast was performed.

April 3, 2022: patient seen by a pulmonologist and discussed with the gastroenterologist, MDT called.

April 4, 2022: first MDT took place, and it was decided to proceed with subcarinal lymph node biopsy.

April 5, 2022: EUS-guided subcarinal lymph node biopsy was performed.

April 14, 2022: report of histopathology and immunochemistry suggested atypical vascular neoplasm favoring angiosarcoma.

April 15, 2022: seen by Oncologist and bone scan performed.

April 18, 2022: patient had persistent worsening anemia and thrombocytopenia, for which a hematologist was involved. All workup for consumptive coagulopathy was done and came back positive. The hematologist diagnosed the case as Kasabach–Merritt syndrome secondary to angiosarcoma.

April 21, 2022: second MDT took place in which pulmonologist, oncologist, hematologist, radiation oncologist, and radiologist were all involved.

April 22, 2022: first session of palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel done.

April 29, 2022: patient last visited our facility with complaints of pain. Pain management team was taken on board in the emergency department, and they gave a prescription and discharged the patient from the emergency department as requested by the patient.

May 2, 2022: because of socioeconomic issues and the patient’s family being in a different country, the patient chose to return to Afghanistan.

Diagnostic assessment

Complete blood picture In Afghanistan, workup showed hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL and platelet count of 210,000/UL.

| 25-04-22 | 19-04-22 | 15-04-22 | 28-03-22 | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLC | 12,040 | 15,560 | 13,710 | 11,380 | 4000–10,500/UL |

| RBC | 3.68 | 3.95 | 3.44 | 3.77 | 4.5–6.5 m/UL |

| Hemoglobin | 8.0 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 13.5–18 g/dL |

| HCT | 26.4 | 28.6 | 24.7 | 27.1 | 42–52% |

| MCV | 71.7 | 72.4 | 71.8 | 71.9 | 78–100 fL |

| MCH | 21.7 | 22.0 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 27–31 pg |

| MCHC | 30.3 | 30.4 | 29.1 | 29.9 | 32–36 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 57,000 | 61,000 | 67,000 | 71,000 | 150,000/450,000/UL |

| Neutrophils | 85 | 59 | 56 | 67 | 54–62% |

| Lymphocytes | 9 | 18 | 19 | 16 | 25–33% |

| Monocytes | 2 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1–4% |

| Eosinophils | 4 | 16 | 17 | 10 | 1–3% |

| Basophils | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0–0.75% |

| RDW | 17.1 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 17.0 | 11.5–14% |

Liver function tests

| Patient value | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| AST | 19 U/L | Up to 50U/L |

| ALT | 25 U/L | Up to 50 U/L |

| ALP | 156 U/L | 40–130 U/L |

| T.B | 0.33 mg/dL | Up to 1.2 mg/dL |

| D.B | 0.17 mg/dL | Up to 0.30 mg/dL |

| GGT | 51 U/L | 51 U/L |

Coagulopathy workup

| Patient value | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Prothrombin time | 30 s | 10–12 s |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 66 s | 21–35 s |

| LDH | 312 U/L | 135–225 U/L |

| Fibrinogen | 112 mg/dL | 200–400 mg/dL |

Serum electrolytes

| Patient value | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 134 mEq/L | 136–145 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 3.9 mEq/L | 3.5–5.1 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 99 mEq/L | 98–107 mEq/L |

| Bicarbonate | 24 mEq/L | 22–29 mEq/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 13 mg/dL | 6–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.6 mg/dL | 0.72–1.25 mg/dL |

HBsAg: negative.

Anti-HCV: negative.

Peripheral film: Schistocytes 6–8/hpf. Platelets decreased on film. Anisopoikilocytosis along with microcytosis. Rule out microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

COVID PCR: negative.

MTB DNA by PCR (GenXpert): negative.

AFB culture: negative.

Sputum culture: negative.

Fungal culture: negative.

Fungal KOH: negative.

Fungal markers: galactomannan (borderline positive), β-d-glucan (negative).

ESR: 140 mm in first hour.

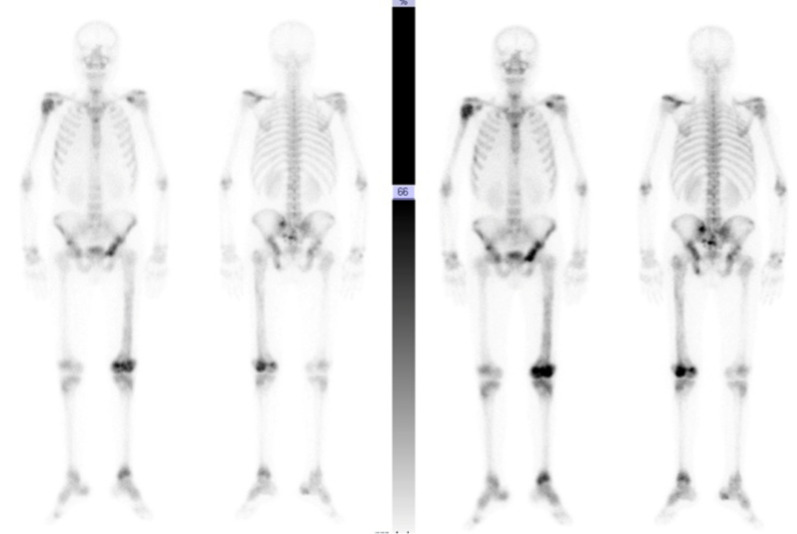

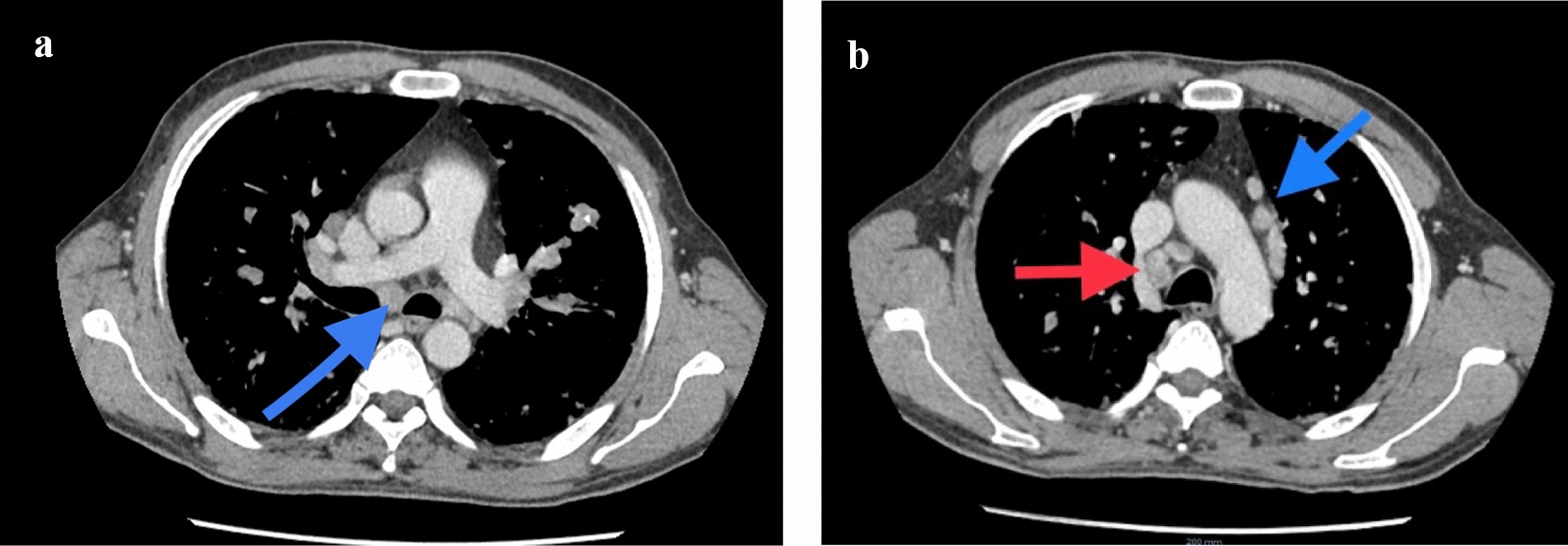

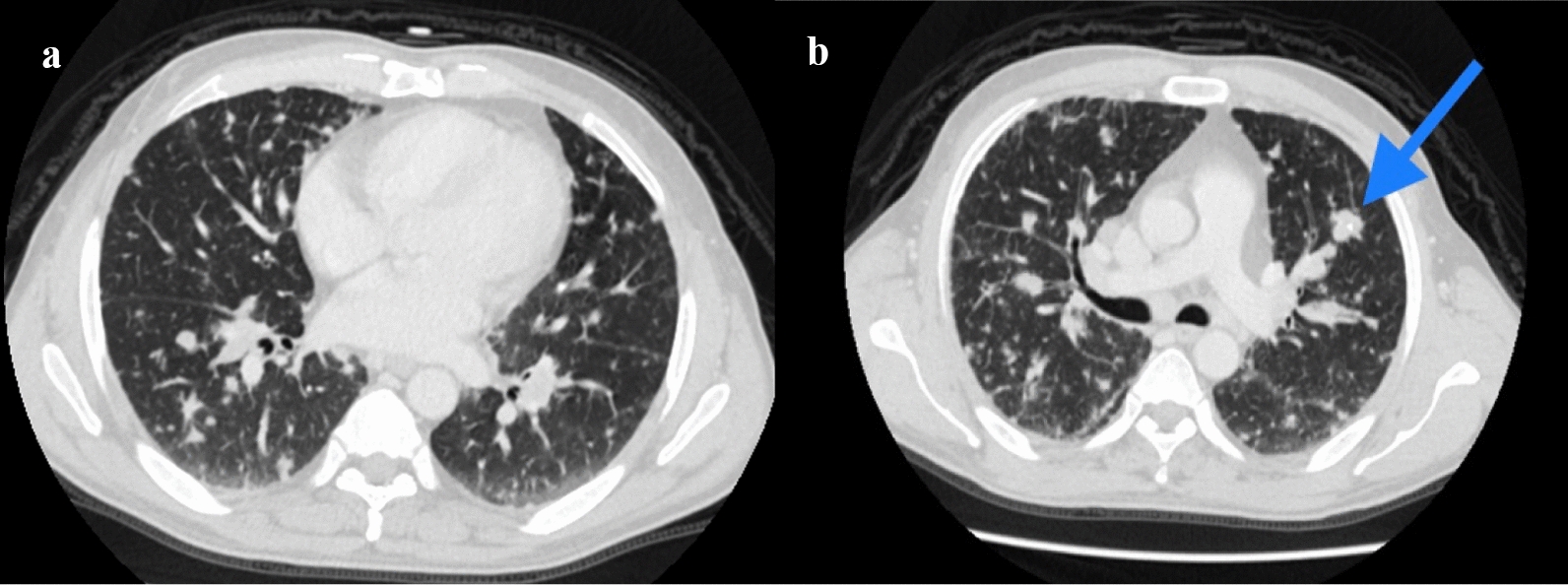

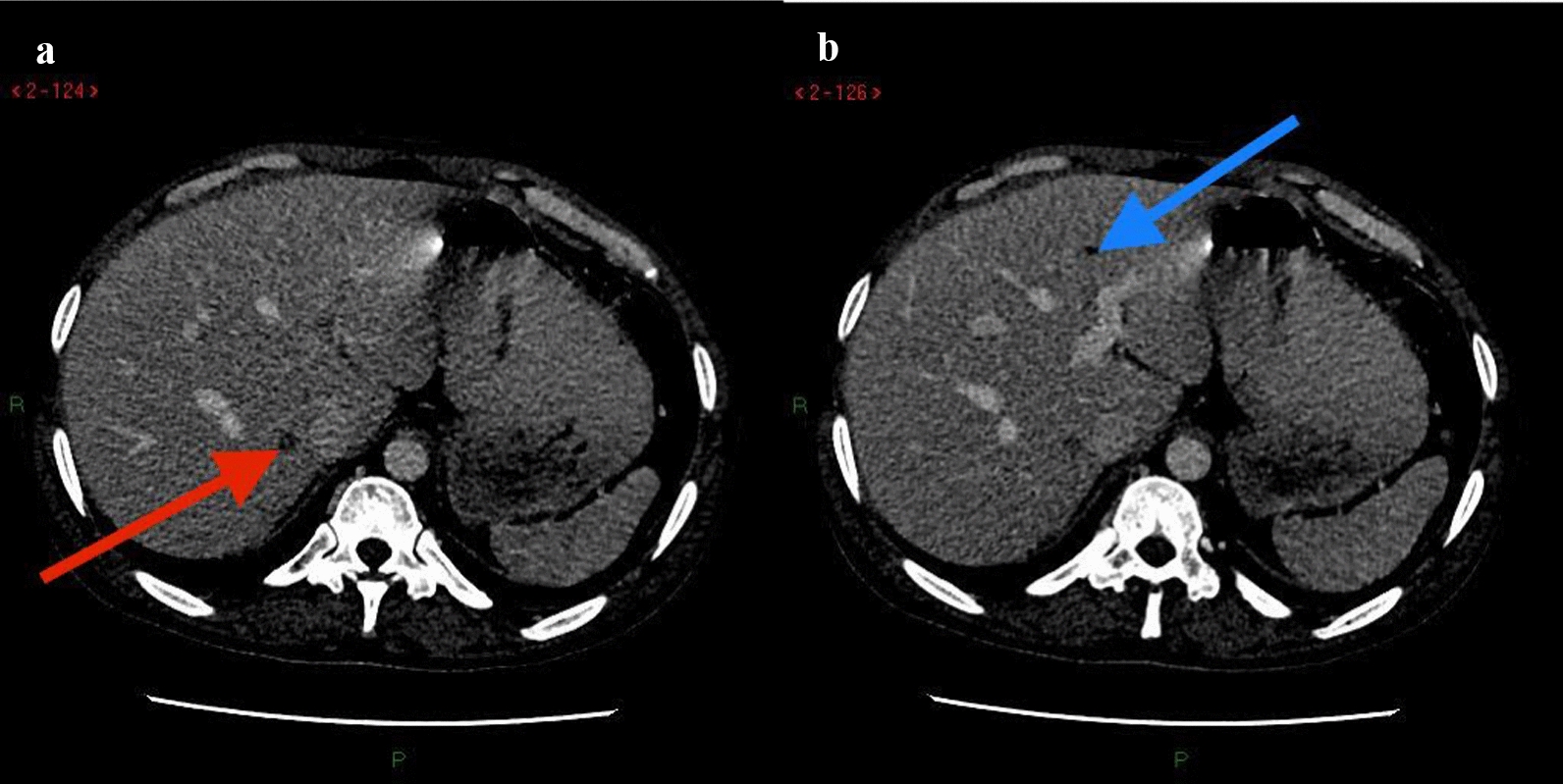

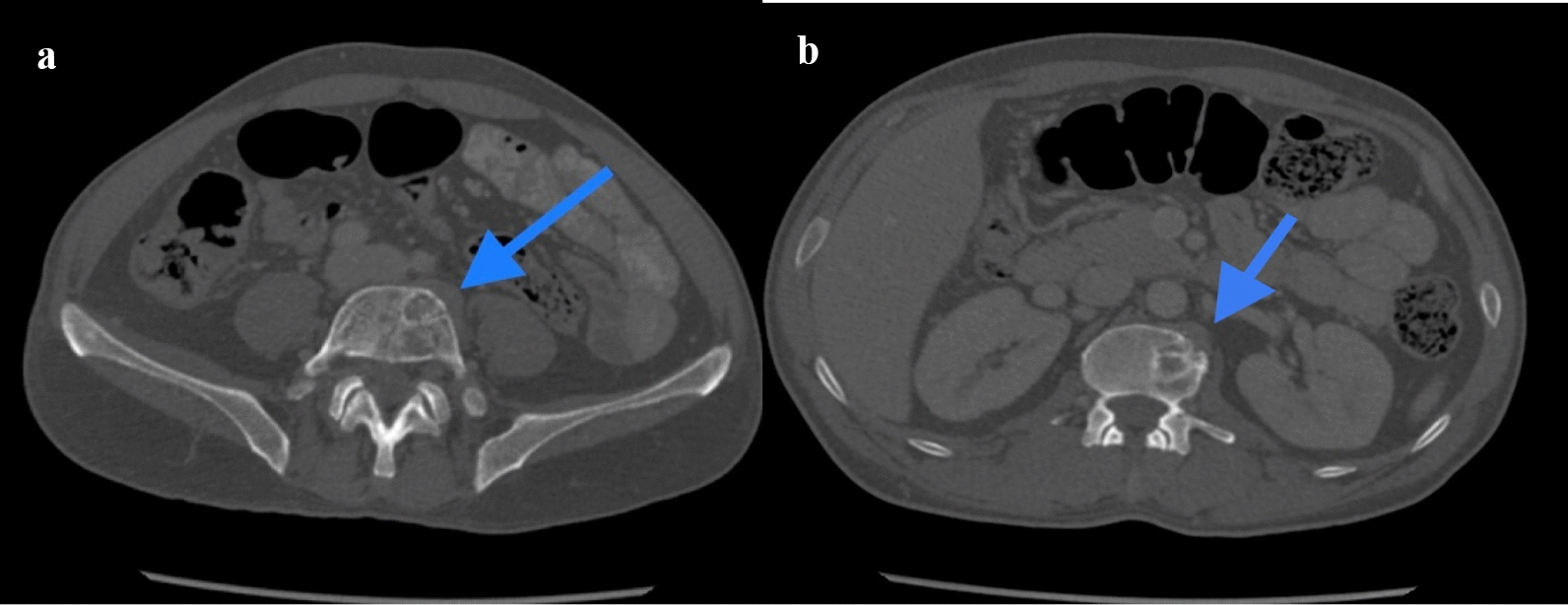

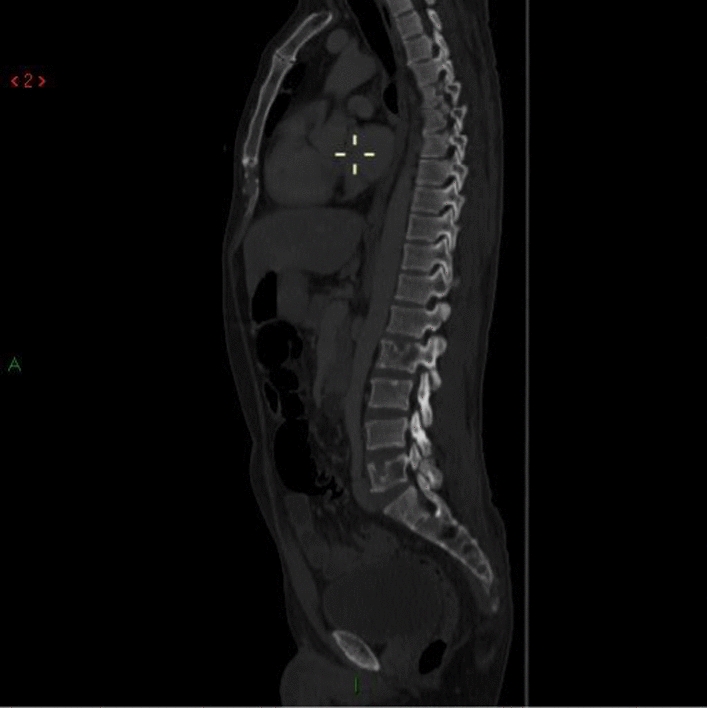

CT of the chest abdomen pelvis with contrast showed extensive mediastinal and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1a, b) with multiple innumerable variable-sized bilateral pulmonary nodules (Fig. 2a, b). Associated interlobular septal thickening with mild fissural nodularity. The largest lymph node was seen in the subcarinal location, measuring 16 mm in short axis. Few hypodensities in the liver were also seen, as shown in Fig. 3a, b, with the largest measuring approximately 8 × 9 mm2 (Fig. 3a). Similar changes also seen in the spleen. Lytic expansile lesions with associated soft tissue components involving L5 and L2 vertebral bodies were also noted (Figs. 4a, b and 5). Prominent Schmorl’s nodules involving L2 and L5 vertebral bodies. Patchy areas of sclerosis involving S1, right iliac, bilateral pubic, and femoral bones.

Fig. 1.

Axial slices of contrast-enhanced CT of chest, mediastinal window showing enlarged subcarinal lymph node (a, blue arrow) and enlarged pre- and paratracheal and prevascular lymph nodes (b, red and blue arrows, respectively)

Fig. 2.

a, b Axial slices of CT chest lung window showing innumerable, variable-sized, randomly distributed bilateral pulmonary nodules with the largest nodule containing internal calcification (blue arrow in b)

Fig. 3.

a, b Axial slices of contrast enhanced CT showing a small hypodensity at the junction of segments VII and VIII (red arrow in a) and segment IVa (blue arrow in b)

Fig. 4.

a, b Axial slices of CT bone window showing lytic expansile lesions with associated soft tissue components involving L5 vertebral body (blue arrow in a) and L2 vertebral body (blue arrow in b)

Fig. 5.

Sagittal CT, bone window showing lytic lesions in L2 and L5

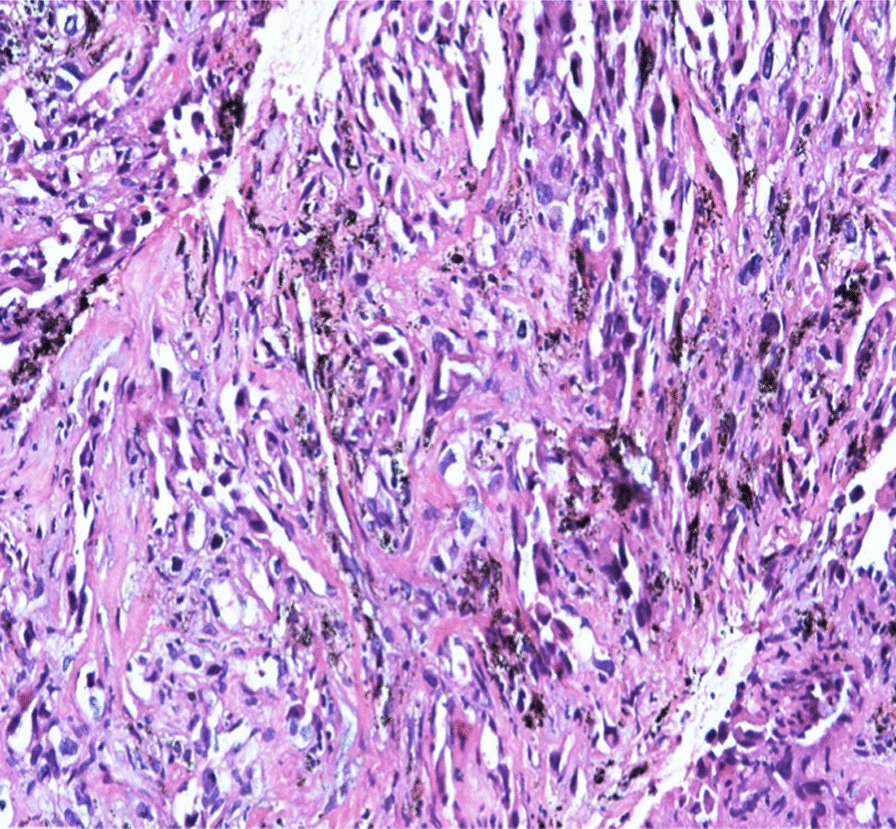

EUS-guided biopsy: biopsy of the subcarinal lymph node was performed.

Histopathology: Showed fragmented cores of infiltrative dyshesive atypical cells with pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei forming slit-like spaces, and vague hob nailing as depicted in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Histopathology specimen of subcarinal lymph node

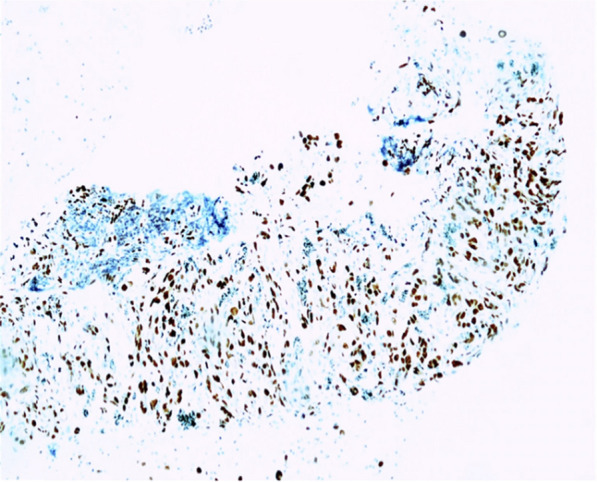

Immunohistochemistry

As shown in Fig. 7:

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemistry slide

CKAE1/3: negative.

CD30: negative.

SALL4: negative.

CD20: negative.

All of the above findings favored a diagnosis of atypical vascular neoplasm, favoring angiosarcoma.

Bone scan: Inhomogenous tracer uptake in multiple levels of spine DV8, LV2, LV5, left scapula, 6th and 7th ribs on the right, head and proximal shaft of the right humerus, and pelvic bones as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Bone scan with multi-level inhomogenous radiotracer uptake

Echocardiography: ejection fraction 60%. Normal study.

Therapeutic intervention

The case was thoroughly discussed by a multidisciplinary team comprising an oncologist, hematologist, gastroenterologist, radiologist, and pulmonologist, and it was decided that the best course of action was to provide palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel. He received a dose of paclitaxel. After that, he decided to proceed with palliative and comfort care and refused any further chemotherapy.

Follow-up and outcomes

The merit and demerits of continuing palliative chemotherapy were discussed in detail with the patient and his family. The patient wanted to return to his homeland and opted not to undergo the second session of chemotherapy. Hence, he was referred to a palliative care consultant, where he was guided about comfort care and pain management. He returned to Afghanistan on 2 May 2022, and no contact could be established with him since then.

Discussion

Angiosarcoma can occur anywhere in the body, with the liver being the most common location for the primary tumor. Our patient initially presented with significant respiratory symptoms, so the primary pathology was thought to be present in the lungs. This is why he was first treated along the lines of eosinophilic pulmonary disease for 1 month, and later despite negative workup of tuberculosis, he was treated with ATT for another month. We need to consider a wide list of differentials, especially when, instead of getting better, the patient gets worse after treatment. Every case with fever, cough, hemoptysis, and weight loss is not pulmonary tuberculosis. Definitive diagnosis should be made before starting ATT. We obtained histopathological evidence of angiosarcoma from a lymph node biopsy and performed a workup for coagulopathy, resulting in a definitive diagnosis of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. Hemoptysis and cough were most likely due to lung metastasis, fever, cough, and weight loss were most probably due to malignancy, and lower back pain was due to bone metastasis. However, we were unable to determine the primary tumor site. A hypodense lesion was visualized in the liver, which is the most common site of angiosarcoma, raising the suspicion of hepatic angiosarcoma. However, we respected the patient’s wish to not perform a diagnostic biopsy of the liver lesion to determine the primary neoplasm. Moreover, he was at higher risk of bleeding during biopsy owing to his coagulopathy.

Conclusion

The patient initially presented with predominant respiratory complaints; his eosinophil count was raised, owing to which he was treated for eosinophilic pulmonary disease. Later he was believed to have tuberculosis. Workup of TB was negative. At that time, alternative diagnoses should have been considered. Empirical treatment with Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB) was started since the patient was in an endemic area. This is somewhat justified but still the patient deteriorated after 1 month of ATT. One must remain vigilant for alternative diagnoses in the case of clinical worsening despite treatment. In our case, histopathological analysis of lymph node and radiological findings led us to the diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Syed Murtaza Hassan Kazmi (pulmonologist) and Dr. Shahzad Riyaz (gastroentrologist).

Declarations

No declaration needed.

Ahmad Talha Tariq

is the main author of this case report. He is currently working as a Resident in Internal Medicine in Shifa International Hospital.

Author contributions

All authors were actively involved during the whole diagnostic workup of the patient and then during management of the case.

Funding

Since this is a case report, no funding was required.

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data for this case are available. All labs and radiological evidence is available. The MDT decision and prescription of palliative chemotherapy record is available and can be produced if required at any moment.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval and consent to participate has been obtained and can be produced at any moment if required.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests in publishing this case report.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fujii F, Kimura T, Tanaka N, et al. Hepatic angiosarcoma with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17(4):655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadhwa S, Kim TH, Lin L, Kanel G, Saito T. Hepatic angiosarcoma with clinical and histological features of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(13):2443–7. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i13.2443.PMID:28428724;PMCID:PMC5385411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasabach HH, Merritt KK. Capillary hemangioma with extensive purpura. Am J Dis Child. 1940;59:1063–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imafuku S, Hosokawa C, Moroi Y, Furue M. Kasabach–Merritt syndrome associated with angiosarcoma of the scalp successfully treated with chemoradiotherapy. Acta Dermato-ve-nereologica. 2008;88:193–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernathova M, Jaschke W, Pechlahner C, Zelger B, Bodner G. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast associated Kasabach–Merritt syndrome during pregnancy. Breast. 2006;15:255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi JJ, Murphey MD. Angiomatous skeletal lesions. Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiol. 2000;4:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Locker GY, Doroshow JH, Zwelling LA, Chabner BA. The clinical features of hepatic angiosarcoma: a report of four cases and a review of the English literature. Medicine. 1979;58:48–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mani H, Van Thiel DH. Mesenchymal tumors of the liver. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:219–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, Hui ZZ, Du WJ, Li RM, Ren XB. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Rafferty C, O’Regan GM, Irvine AD, Smith OP. Recent advances in the pathobiology and management of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data for this case are available. All labs and radiological evidence is available. The MDT decision and prescription of palliative chemotherapy record is available and can be produced if required at any moment.