Abstract

Background

Polio, a debeilitating and potentially life-threatening disease, continues to pose a risk to young children globally. While vaccination offers a powerful shield, its reach is not always equal. This study explores socioeconomic and geographical inequalities in polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019.

Methods

The study utilised data from the Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey rounds conducted in 2008, 2013, and 2019 to examine polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds. The World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit software calculated various inequality measures, including simple difference, ratio, population-attributable risk, and population-attributable fraction. An inequality assessment was conducted for six stratifiers: maternal age, maternal economic status, maternal level of education, place of residence, sex of the child, and sub-national region.

Results

Polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone increased from 48.7% in 2008 to 77.1% in 2013, then declined to 61.2% in 2019. No significant inequalities were observed based on maternal age, child’s sex or maternal educational level. Coverage was higher among children of mothers from the poorest households, and in rural areas. However, the main inequality identified was subnational inequality.

Conclusion

The initial increase in coverage followed by a decline underscores the need for sustained efforts to maintain and improve immunization rates, particularly in the Western, Northwestern, and Northern provinces, where significant subnational inequalities exist. The absence of disparities related to maternal age, child sex, and education suggests that traditional demographic factors may not be the primary barriers to immunization; instead, geographic and socioeconomic contexts play a more pivotal role. This indicates that targeted interventions should focus on improving access to vaccination services in underserved areas, potentially through community outreach and mobile vaccination units. Additionally, the better coverage among children of poorer mothers and those in rural areas highlights the importance of understanding local dynamics and leveraging community strengths to enhance immunization uptake.

Keywords: Children, Immunisation, Polio, Public Health, Sierra Leone

Introduction

Poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, is a contagious viral disease that primarily affects children younger than five [1–4]. Eradicating polio remains a global priority, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, as the disease is highly contagious but entirely preventable through vaccination [5]. The virus spreads primarily by the fecal-oral route, and less frequently, by a shared medium (such as contaminated food or water). It is passed from person to person and multiplies in the intestine before entering the neurological system, causing paralysis [1, 2, 4]. Since there is no cure for polio, prevention through vaccination is the only effective strategy. Repeated doses of the polio vaccine can provide a lifelong immunity. Two types of vaccines are currently available: the oral polio vaccine (OPV) and the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). Both are safe and effective, and used globally in varying combination [2].

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), launched by the World Health Assembly in 1988, includes collaboration among national governments, the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance [1]. Between 1988 and October 2023, only two countries Afghanistan and Pakistan remained endemic for wild poliovirus type 1. This marks a significant decline of nearly 99% from around 350,000 reported cases in more than 125 endemic nations [1–5]. Among the three strains of wild poliovirus (type 1, type 2, and type 3), wild poliovirus type 2 was eradicated in 1999, and wild poliovirus type 3 was eradicated in 2020 [1].

Despite the progress in polio reduction, Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly West Africa, continues to report the highest rates of polio cases [5]. This highlights persistent challenges in achieving equitable immunization coverage. Immunization rates vary significantly based on regional, demographic, and socioeconomic factors, especially in low- and middle-income countries [2]. Reports from WHO and UNICEF indicate that, despite advancements, immunization coverage remains inconsistent, with gaps persisting across and within countries and regions [3]. The GAVI Alliance’s 2021–2025 high-level strategy emphasizes the importance of reaching marginalized groups to address these disparities and prioritize equity in immunization efforts [4]. This continued focus is crucial for ensuring that all children, particularly those in high-burden areas like Sub-Saharan Africa, receive the protection they need against polio.

According to the International Health Regulations (IHR), Sierra Leone is no longer affected with circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (cVDPV) but is still susceptible to infection. As of March 2024, the country is subject to the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee on Polio Eradication’s Temporary Recommendations [6]. However, in March 2024, a confirmed type 2 poliovirus (cVDPV2) outbreak was reported in the country and neighbouring Guinea and Liberia. This led to coordinated house-to-house vaccination campaigns against polio in the first round, which involved five additional countries: Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Guinea. The novel oral polio vaccine (nOPV2) was used in these campaigns. To eradicate polio, all children under five years old needed to receive the vaccination simultaneously, which is why the synchronization was implemented [7, 8]. About 1,669,594 children under five had received vaccinations nationwide in the first vaccination round [7]. During the campaign, more than 4,000 medical teams were called to participate in community outreach and provide vaccines [7].

Sierra Leone has shown its dedication to public health by working with partners to lessen the effects of the polio outbreak and stopping it spread [8]. However, there is no study on the trends and inequalities in polio vaccination coverage in Sierra Leone. Gaining insight into the inequalities of polio immunization coverage can guide stakeholders in implementing targeted interventions, particular for underserved population, thereby improving overall population immunity. Therefore, this study aimed to explore socioeconomic and geographical inequalities in polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019.

Methods

Study design and source

We used data from the Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey (SLDHS) conducted in 2008, 2013, and 2019. The SLDHS is a comprehensive national survey designed to identify trends in social issues, health indicators, and demographics for all age groups and genders. Participants were selected for the study using a stratified multi-stage cluster sampling technique applied in a cross-sectional design. Detail information on the sampling procedure can be found in the SLDHS report [9]. Two-year-old children whose mothers provided information on their polio vaccination records during the relevant SLDHS cycles were included in this study. The SLDHS data from 2008, 2013, and 2019 were accessed through the WHO Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT) online platform [10]. HEAT is a software application developed by the World Health Organization. HEAT is designed to facilitate the exploration, analysis, and reporting of health inequality data. It includes data from the Health Inequality Data Repository, allowing users to assess and visualize health disparities effectively. For our analysis, we utilized disaggregated data from the Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey (SLDHS) health indicators available in HEAT. However, it is important to note that HEAT does not encompass all data from the SLDHS; it specifically includes selected datasets relevant to health equity assessments. In this study, we focused on the Childhood Immunization dataset within HEAT to analyze polio immunization inequalities among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone.The study was carefully designed, considering the recommendations made in the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [11].

Outcome measure and dimensions of inequality

The coverage of polio vaccinations was estimated for two-year-olds. The percentage of children aged 12 to 23 months who received the polio vaccine at least three times before the survey was analyzed to assess vaccination coverage in this critical age group. We chose to focus on children between 12 and 23 months rather than one-year-olds because this age range allows us to capture a more comprehensive picture of immunization coverage. By including children up to 23 months, we account for variations in vaccination schedules and ensure that we assess those who may have received their vaccinations later than the standard timeline. This approach provides a clearer understanding of overall vaccination trends and helps identify any disparities in coverage. The mother’s account of the immunisation card given to the interviewer is the basis for this information. When the interviewee did not provide a card (that is, when this option was not available), the mother’s report was the source of information on the child’s status as a recipient of the polio vaccination. The absence of the mother’s immunisation record proved that the polio vaccine had not been given. There were two age groups of the mothers (current age of mothers): 15–19 years and 20–49 years in the HEAT software. Those were the only two age brackets provided in the dataset, which limited our options for segmentation. Women’s economic status was categorized into five groups: poorest, poorer, middle-class, rich, and richest based on household wealth quintiles, which were determined by dividing the wealth index into five equal parts according to the distribution of wealth index scores in the dataset. The cut points for the wealth index scores defining each quintile were as follows: Poorest (Quintile 1: -5.09077 to -2.74422), Poorer (Quintile 2: -2.74422 to -1.32015), Middle-class (Quintile 3: -1.32015 to 0.25678), Rich (Quintile 4: 0.25678 to 2.14567), and Richest (Quintile 5: 2.14567 to 5.89012). These ranges ensured an equal division of the population into five groups based on household wealth. Three groups were obtained from the HEAT software based on the mother’s educational status: no, primary, and secondary or higher education. The HEAT software combined secondary and higher education into a single category due to the small sample sizes for both categories in the 2008 dataset. By merging these two levels of education, they aimed to enhance the statistical power of their analysis and ensure more reliable results. The place of residence was either in an urban or rural area. The child’s sex was noted as either male or female. The sub-national provinces of Sierra Leone consist of five distinct geographical areas: the Western Area, which includes the capital city Freetown; Northern Province, characterized by diverse communities and agricultural activities; Southern Province, known for its rich cultural heritage and agricultural economy; Eastern Province, marked by unique ethnic groups and economic activities; and the Northwest Region, a newer administrative designation encompassing several districts.

Data analysis

We utilized the web-based version of the WHO Health Equity Assessment Toolkit for analysis. This platform designed to facilitate the exploration of health inequality data and provides estimates, confidence intervals, and summary measures of inequality. This toolkit allowed for a detailed analysis of polio immunization coverage disaggregated by six dimensions of inequality. These insights enabled a comprehensive evaluation of disparities, and informed conclusions based on the data. Maternal age, province, child’s sex, socioeconomic status, education level, and place of residence were the inequality dimensions used.

Four metrics were utilized to calculate inequality: Difference (D), Ratio (R), Population Attributable Fraction (PAF), and Population Attributable Risk (PAR). D measures the absolute gap in polio vaccination coverage between two subgroups, providing a straightforward comparison of their respective rates. R compares the vaccination coverage of two subgroups by dividing the coverage of one subgroup by the other, offering a relative measure of inequality. Both Difference and Ratio are unweighted measures, meaning they do not account for the population sizes of the subgroups and focus solely on the two groups being compared. On the other hand, PAR estimates the proportion of a health outcome that can be attributed to a specific risk factor within the population, while PAF indicates the percentage of the total health outcome that would be eliminated if the risk factor were removed. These measures provide insights into the potential impact of reducing inequalities on overall health outcomes. For a comprehensive explanation of the calculation of these measures, please refer to the literature [12]. R and PAF are relative measures of inequality, used to evaluate and compare the differences between various elements in relation to one another. In contrast, D and PAR are absolute measures, providing clear-cut values that indicate the actual gap in vaccination coverage or the proportion of health outcomes attributable to a specific risk factor. This distinction is important, as absolute measures like D and PAR offer straightforward insights into the magnitude of inequality, while relative measures like R and PAF contextualize these differences within the broader population dynamics. The World Health Organisation (WHO) acknowledged that to derive conclusions that are useful to policy, summary metrics must be included in absolute and relative forms. The World Health Organisation metrics’ summary measurements and computations are thoroughly explained in the literature [13, 14].

Results

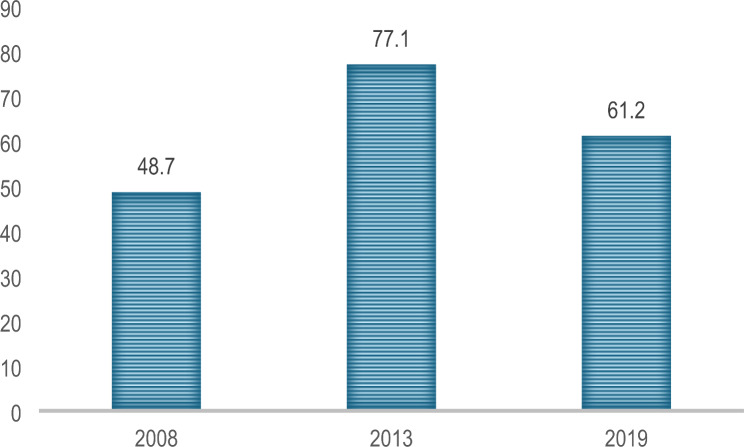

Figure 1 shows polio immunization coverage among children aged two-year-olds in Sierra Leone. In 2008, the polio immunization coverage was 48.7%. This figure increased to 77.1% by 2013, and later declined to 61.2% in 2019.

Fig. 1.

Polio immunisation coverage among children aged two-year-olds in Sierra Leone 2008, 2013 and 2019

Source: World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit, 2024

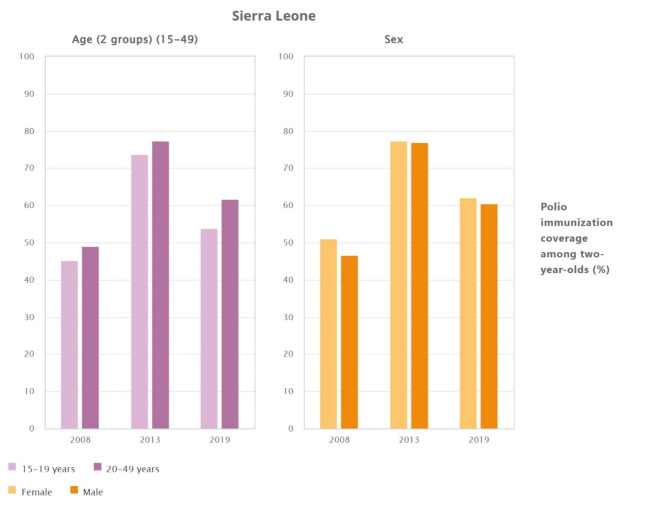

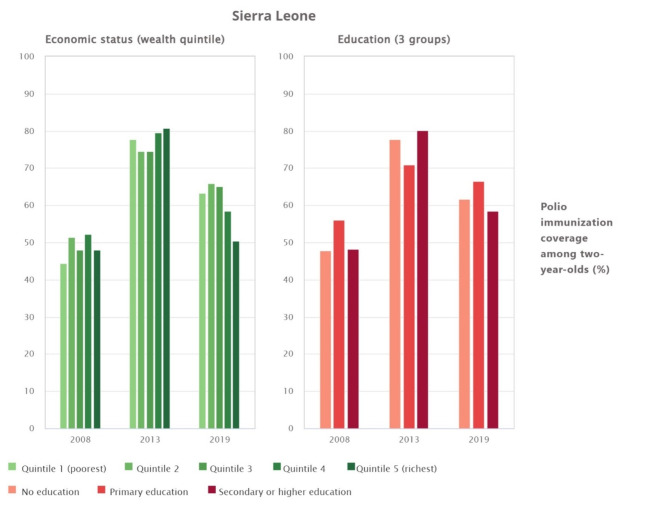

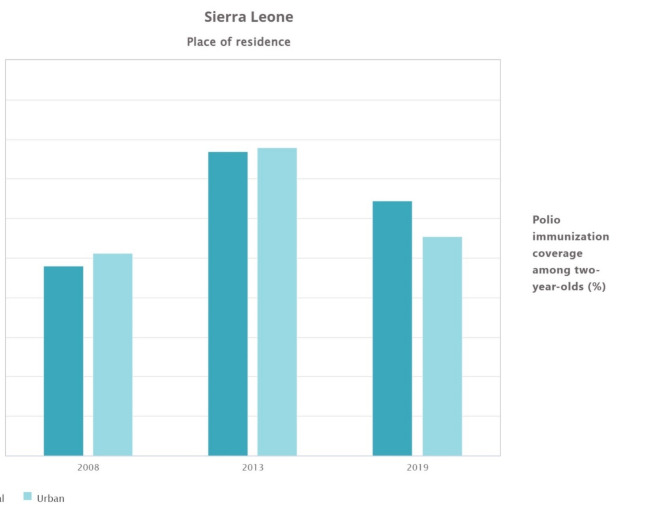

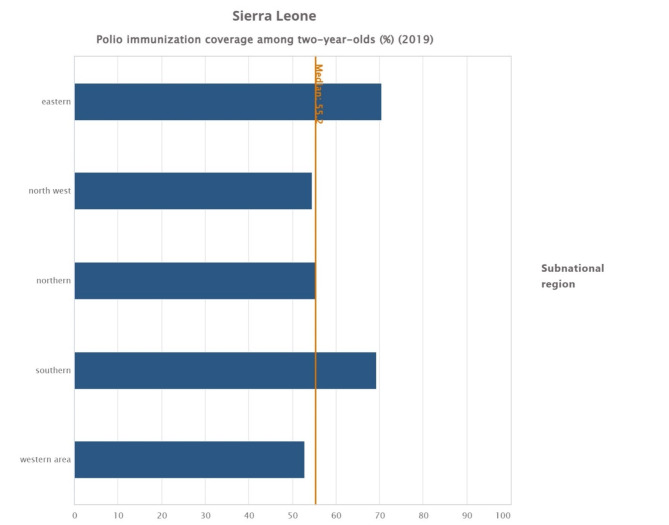

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 shows polio immunisation coverage trends among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone by different inequality dimensions. Among children of mothers aged 15–19 years old, coverage was 45.1% in 2008, 73.6% in 2013, and 53.7% in 2019. For children of mothers aged 20–49 years old, coverage was 49.0% in 2008, 77.3% in 2013, and 61.6% in 2019. The children of mothers in the poorest quintile (Quintile 1) had 44.4% coverage in 2008, 77.7% in 2013, and 63.2% in 2019. The children of mothers in the richest quintile (Quintile 5) had 47.9% coverage in 2008, 80.6% in 2013, and 50.3% in 2019. Children with parents with no education had 47.7% coverage in 2008, 77.6% in 2013, and 61.6% in 2019. The primary education group had 56.0% coverage in 2008, 70.9% in 2013, and 66.4% in 2019. The secondary or higher education group had 48.2% coverage in 2008, 80.1% in 2013, and 58.3% in 2019. Urban areas had 51.1% coverage in 2008, 77.8% in 2013, and 55.4% in 2019. Rural areas had 47.9% coverage in 2008, 76.9% in 2013, and 64.4% in 2019. Females had 51.0% coverage in 2008, 77.3% in 2013, and 62.0% in 2019. Males had 46.6% coverage in 2008, 76.9% in 2013, and 60.5% in 2019. The Eastern province had the highest coverage (58.8% in 2008, 78.7% in 2013, and 70.5% in 2019). The Northern province had 43.6% coverage in 2008, 74.7% in 2013, and 55.2% in 2019. The Southern province had 54.4% coverage in 2008, 81.8% in 2013, and 69.3% in 2019. The Western Area had 41.2% coverage in 2008, 70.2% in 2013, and 52.8% in 2019 (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Trends in the prevalence of polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds by age of mother and sex of the child inequality dimensions in Sierra Leone, 2008, 2013, and 2019

Source: World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit, 2024

Fig. 3.

Trends in the prevalence of polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds by maternal economic status and education inequality dimensions in Sierra Leone, 2008, 2013, and 2019

Source: World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit, 2024

Fig. 4.

Trends in the prevalence of polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds by place of residence inequality dimension in Sierra Leone, 2008, 2013, and 2019

Source: World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit, 2024

Fig. 5.

Provincial coverage of polio immunisation among children aged two-year-olds in Sierra Leone 2019. Source: World Health Organisation Health Equity Assessment Toolkit, 2024

Table 1.

Trends in the prevalence of Polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds by different inequality dimensions in Sierra Leone, 2008–2019

| 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | N | %. | LB | UB | N | %. | LB | UB | N | %. | LB | UB |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 15–19 years | 57 | 45.1 | 30.2 | 61.0 | 129 | 73.6 | 65.1 | 80.6 | 85 | 53.7 | 42.4 | 64.6 |

| 20–49 years | 881 | 49.0 | 45.1 | 52.9 | 1881 | 77.3 | 74.3 | 80.1 | 1580 | 61.6 | 58.5 | 64.6 |

| Economic status | ||||||||||||

| Quintile 1 (poorest) | 196 | 44.4 | 36.4 | 52.6 | 480 | 77.7 | 72.5 | 82.2 | 378 | 63.2 | 57.2 | 68.7 |

| Quintile 2 | 197 | 51.4 | 41.3 | 61.3 | 470 | 74.4 | 68.7 | 79.4 | 370 | 65.9 | 60.5 | 71.0 |

| Quintile 3 | 233 | 48.0 | 39.9 | 56.3 | 392 | 74.5 | 68.8 | 79.5 | 343 | 65.1 | 59.6 | 70.2 |

| Quintile 4 | 176 | 52.2 | 43.5 | 60.8 | 393 | 79.5 | 74.0 | 84.1 | 309 | 58.3 | 52.1 | 64.3 |

| Quintile 5 (richest) | 134 | 47.9 | 38.6 | 57.3 | 275 | 80.6 | 68.9 | 88.6 | 264 | 50.3 | 41.2 | 59.4 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 731 | 47.7 | 43.0 | 52.6 | 1431 | 77.6 | 74.3 | 80.6 | 889 | 61.6 | 57.9 | 65.2 |

| Primary education | 107 | 56.0 | 44.3 | 67.1 | 276 | 70.9 | 62.3 | 78.1 | 240 | 66.4 | 59.4 | 72.8 |

| Secondary or higher education | 99 | 48.2 | 36.9 | 59.6 | 303 | 80.1 | 73.8 | 85.2 | 535 | 58.3 | 52.8 | 63.6 |

| Residence | ||||||||||||

| Rural | 686 | 47.9 | 43.1 | 52.8 | 1543 | 76.9 | 73.5 | 79.9 | 1076 | 64.4 | 61.1 | 67.7 |

| Urban | 252 | 51.1 | 44.8 | 57.3 | 467 | 77.8 | 70.7 | 83.5 | 589 | 55.4 | 49.6 | 60.9 |

| Sex of child | ||||||||||||

| Female | 462 | 51.0 | 45.1 | 56.8 | 1035 | 77.3 | 73.3 | 80.8 | 843 | 62.0 | 58.1 | 65.7 |

| Male | 476 | 46.6 | 41.3 | 51.9 | 975 | 76.9 | 73.5 | 79.9 | 821 | 60.5 | 56.2 | 64.5 |

| Province | ||||||||||||

| Eastern | 195 | 58.8 | 51.9 | 65.3 | 494 | 78.7 | 73.0 | 83.4 | 355 | 70.5 | 63.5 | 76.7 |

| Northern | 415 | 43.6 | 37.0 | 50.5 | 745 | 74.7 | 70.0 | 78.9 | 289 | 55.2 | 48.8 | 61.5 |

| Northwestern | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 320 | 54.5 | 48.8 | 60.1 |

| Southern | 199 | 54.4 | 47.0 | 61.6 | 540 | 81.8 | 76.3 | 86.2 | 394 | 69.3 | 63.7 | 74.4 |

| Western | 128 | 41.2 | 32.4 | 50.6 | 230 | 70.2 | 57.4 | 80.5 | 305 | 52.8 | 44.2 | 61.2 |

N: Sample size; NA-Not available as between 2008 and 2013, Sierra Leone had four regions; LB: Lower Bound; UB: Upper Bound

Table 2 presents the inequality measures for polio immunization in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019. Maternal age-related inequality, shifted from a difference of 3.8% points in 2008 to 7.9% points in 2019. However, the CIs of D for both 2008 and 2019 cross the value of zero and the CIs for R cross the value of one, meaning that there was no statistically significant difference in polio immunization coverage between the two age groups. The PAR and PAF indicate that the setting average could have been 0.2% points, or 0.4 times, higher in 2008, 0.3% points, or 0.3 times, higher in 2013, and 0.6% points, or 0.4 times, higher in 2019 without age-related inequality. Economic inequality, measured as the difference in immunization coverage between the richest and poorest groups, showed a shift from 3.5% points in 2008 to -12.8% points in 2019. This indicates that coverage was higher among the richest in 2008 but became higher among the poorest in 2019, reflecting a positive pro-poor change in immunization coverage. The PAR and PAF for economic inequality were zero in both 2008 and 2019, suggesting no further improvement. Inequality in education, measured as the difference in coverage between children of mothers with secondary or higher education and with no education, shifted from a difference of 0.4% points in 2008 to -3.2% points in 2019. However, the CIs of D show little inequality in 2008 but no inequality in 2019, meaning that there was no statistically significant difference in polio immunization coverage between the education groups. For place of residence, measured as the difference in immunization coverage between urban and rural areas changed from a difference of 3.1% points in 2008 to -9.0% points in 2019. This reflects a positive shift, with rural children achieving higher immunization levels than their urban counterparts. Regarding the child’s sex, the difference in coverage between male and female children shifted from a difference of 4.4% points in 2008 to 1.5% points in 2019. This indicates a decrease in sex-related inequality, with female children reaching closer levels of immunization to male children. However, the CIs of D for both 2008 and 2019 cross the value of zero and the CIs for R cross the value of one, meaning that there was no statistically significant difference in polio immunization coverage between the sex of the child. Lastly, regional inequality measured as the difference between the best and the worst performing region showed no significant change, remaining at 17.5% points in 2008 and 17.7% points in 2019, as indicated by the overlapping confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Inequality indices of estimates of factors associated with polio immunisation coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone, 2008–2019

| 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Est. | LB | UB | Est. | LB | UB | Est. | LB | UB |

| Age | |||||||||

| D | 3.8 | -12.5 | 20.1 | 3.7 | -4.4 | 12.0 | 7.9 | -3.7 | 19.6 |

| R | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| PAF | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| PAR | 0.2 | -0.5 | 1.0 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Economic status | |||||||||

| D | 3.5 | -8.9 | 15.9 | 2.8 | -8.0 | 13.8 | -12.8 | -23.6 | -2.0 |

| R | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| PAF | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 |

| PAR | 0 | -7.8 | 7.8 | 3.5 | -0.8 | 7.9 | 0 | -5.5 | 5.5 |

| Education | |||||||||

| D | 0.4 | -12.0 | 12.9 | 2.5 | -3.9 | 8.9 | -3.2 | -9.7 | 3.1 |

| R | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| PAF | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 |

| PAR | 0 | -9.2 | 9.2 | 3.0 | -1.1 | 7.2 | 0 | -3.4 | 3.4 |

| Residence | |||||||||

| D | 3.1 | -4.7 | 11.0 | 0.8 | -6.2 | 8.0 | -9.0 | -15.6 | -2.5 |

| R | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.24 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| PAF | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 |

| PAR | 2.3 | -2.9 | 7.6 | 0.6 | -2.6 | 3.9 | 0 | -3.2 | 3.2 |

| Sex of child | |||||||||

| D | -4.4 | -12.3 | 3.4 | -0.4 | -5.2 | 4.4 | -1.5 | -7.1 | 4.1 |

| R | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| PAF | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | -0.0 | 0.0 |

| PAR | 0 | -3.1 | 3.1 | 0 | -1.8 | 1.8 | 0 | -2.3 | 2.3 |

| Province | |||||||||

| D | 17.5 | 6.2 | 28.9 | 11.5 | -1.1 | 24.1 | 17.7 | 6.9 | 28.5 |

| R | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| PAF | 20.5 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 15.1 | 15.0 | 15.2 |

| PAR | 10.0 | 3.8 | 16.2 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 13.6 |

Est: Estimate; LB: Lower Bound; UB: Upper Bound; D: Difference; PAF: Population Attributable Fraction; PAR: Population Attributable Risk; R: Ratio

Discussion

The study on the socioeconomic and geographical inequalities in polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019 reveals critical insights into the dynamics of health equity in the country. The initial increase in coverage from 48.7% in 2008 to 77.1% in 2013 indicates successful public health interventions during this period, likely influenced by increased awareness and accessibility of vaccination services [15–18]. However, the subsequent decline to 61.2% in 2019 raises concerns about sustainability and the potential impact of external factors, such as economic instability, health system challenges, or changes in public health policy [19–22]. This fluctuation underscores the necessity for continuous monitoring and adaptive strategies to ensure that immunization coverage remains robust and equitable.

The results indicate that there is no maternal age-related inequality in polio immunization coverage in Sierra Leone for both 2008 and 2019. This finding contrasts with a study in Kenya, where maternal age often correlates with disparities in immunization rates [23]. The lack of significant disparity in Sierra Leone may suggest effective health policies or community outreach programs that have successfully mitigated age-related gaps [24]. The implications of these findings are twofold: they underscore the importance of maintaining and enhancing current immunization strategies while also indicating that age may not be a critical factor affecting coverage in this context. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to provide insights into how these dynamics evolve over time, particularly in response to changing health policies and socio-economic conditions.

The shift in economic inequality from a 3.5% point advantage for the richest in 2008 to a -12.8-percentage point advantage for the poorest in 2019 highlights a significant pro-poor trend in immunization coverage. This finding is consistent with a study on economic-related inequalities in child health interventions [25]. However our finding is inconsistent with a study on inequalities in maternal healthcare use in Sierra Leone using demographic health survey data from 2008 to 2019 [26]. In that study, women’s accessibility to healthcare services favored women with high socioeconomic status [26]. The shift towards pro-poor immunization coverage in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019 can be attributed to several national policies and campaigns that likely influenced this positive trend. Between 2013 and 2019, Sierra Leone implemented targeted health initiatives aimed at increasing access to immunization for vulnerable populations, including the National Immunization Days and enhanced outreach programs in underserved areas [27]. These efforts were complemented by international support and funding, particularly in the wake of the Ebola outbreak, which heightened awareness of the importance of health infrastructure and equitable access to healthcare services. Additionally, the government prioritized routine immunization through policy reforms that focused on integrating immunization services into primary healthcare, thereby improving accessibility for low-income families [27]. The collaboration between governmental and non-governmental organizations in mobilizing resources and awareness campaigns played a crucial role in reaching marginalized communities. Other countries can learn from Sierra Leone’s experience by emphasizing the importance of targeted health initiatives, fostering partnerships between various stakeholders, and ensuring that health policies are inclusive and responsive to the needs of the poorest populations. Sustaining these gains will require continuous investment in health equity and monitoring the impact of economic factors on access to immunization services. The results show that there was no education-related inequality in Sierra Leone. Contrary to our finding several studies have reported inequality in favor of children whose caregivers had secondary or higher education than their counterparts whose parents/caregivers had no education in the African region [28–30]. In Sierra Leone initiatives such as community outreach programs, mobile vaccination clinics, and collaboration with local leaders have enhanced awareness and encouraged participation among parents [27]. Furthermore, the integration of immunization education into primary health care services and schools has helped inform families about the importance of vaccinations, fostering a more equitable environment for immunization. These efforts, combined with targeted campaigns addressing cultural beliefs and misinformation, have played a crucial role in ensuring that all children, regardless of their parents’ educational background, receive essential vaccinations.

The significant change in place of residence inequality, with the difference in coverage between rural and urban areas shifting from 3.1% points in 2008 to -9.0% points in 2019, illustrates a remarkable improvement in rural health access. This finding is inconsistent to a study conducted in Ethiopia [4], where the authors reported a higher polio immunization coverage among children in urban areas. Our findings indicate that rural children are increasingly receiving vaccinations at rates higher than their urban counterparts, likely due to intensified outreach efforts and the establishment of more accessible healthcare facilities in rural areas [31]. The establishment of mobile vaccination units and community health worker programs in the country significantly improved accessibility for rural populations, ensuring that immunization services reached even the most remote areas [27]. Additionally, public awareness campaigns played a crucial role in educating communities about the importance of vaccinations, fostering greater demand among rural families. This shift highlights the effectiveness of comprehensive health strategies that address geographical disparities and ensure equitable access to healthcare services. Other countries can learn from Sierra Leone’s experience by prioritizing rural health initiatives, investing in healthcare infrastructure, and fostering community engagement to sustain and enhance immunization coverage across diverse populations. Continuous monitoring and support will be essential to maintain these gains and address any emerging challenges in rural health systems.

The results indicate that there was no sex-related inequality in polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone for both 2008 and 2019. The absence of significant gender disparities in Sierra Leone reflects successful public health initiatives aimed at promoting equitable immunization practices, driven by community awareness campaigns and government policies focused on gender equality in healthcare access [27]. The implications of these findings are significant, suggesting that Sierra Leone’s immunization programs are effectively reaching both male and female children, which is crucial for achieving herd immunity and overall public health goals. Other countries can learn from Sierra Leone’s experience by adopting similar gender-focused health policies, enhancing community engagement, and ensuring that immunization campaigns explicitly address and promote equity for all children, regardless of sex. Sustaining this momentum will require ongoing monitoring and commitment to gender equity in healthcare access to prevent any regression in these gains.

Conversely, the lack of significant change in provincial inequality, which remained stable at approximately 17.5% points, highlights persistent disparities that require focused interventions. The lower coverage in the Western, Northwestern, and Northern provinces may stem from several factors, including limited access to healthcare facilities, inadequate transportation infrastructure, and socio-economic challenges that hinder vaccination outreach efforts [20]. Additionally, cultural beliefs and misinformation about vaccines can further exacerbate these disparities, particularly in more remote areas. Addressing these regional inequalities is essential for achieving comprehensive health equity in Sierra Leone. Targeted policies should be developed that consider the unique needs and challenges faced by these regions. This could include increasing the availability of mobile vaccination units to reach underserved populations, enhancing community engagement to build trust and dispel myths surrounding immunization, and investing in infrastructure to improve access to healthcare services. Furthermore, collaboration with local leaders and organizations can help tailor interventions to specific community contexts, ensuring that immunization campaigns are culturally sensitive and effectively address barriers to access. By focusing on these strategies, it is possible to reduce regional disparities and improve overall immunization coverage across Sierra Leone.

Policy and practice implications

The findings from our study on the socioeconomic and geographical inequalities in polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone between 2008 and 2019 have several important implications for policy and practice. The decline in immunization coverage from 2013 to 2019 signifies the need for robust strategies to sustain and enhance immunization rates. Policymakers should prioritize the development and implementation of comprehensive immunization campaigns that are adaptable to changing circumstances and responsive to community needs. The lack of maternal-age inequality in Sierra Leone suggest effective health policies or community outreach programs that have successfully mitigated age-related gaps and efforts should continue. The positive shift in economic inequality indicates that interventions have benefited poorer populations. Policymakers should continue to prioritize pro-poor health policies, ensuring that immunization services remain accessible and affordable for low-income families. This may involve subsidizing vaccination costs or providing incentives for families to participate in immunization programs. The convergence in immunization coverage between children of educated and less educated parents suggests that educational outreach is effective. Health authorities should expand educational initiatives that empower parents with knowledge about the importance of vaccinations, utilizing community leaders and local organizations to disseminate information effectively. The improvement in rural immunization coverage underscores the importance of continued investment in rural healthcare infrastructure. Policymakers should ensure that rural health facilities are adequately equipped and staffed to provide essential immunization services, thereby maintaining high coverage rates in these areas. The no sex-related inequality is a positive outcome; however, efforts must continue to promote gender equity in health access. The persistent provincial inequality indicates the need for localized health strategies that address the unique challenges faced by different regions. Policymakers should conduct thorough assessments to identify specific barriers to immunization in underperforming areas and implement tailored interventions to address these issues effectively. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of immunization coverage and inequalities are crucial for informed policymaking. Establishing robust data collection systems will enable health authorities to track progress, identify emerging disparities, and adjust strategies as needed to ensure equitable access to immunization.

Strengths and limitations

The SLDHS 2008, 2013 and 2019 datasets provide data that reflects the situation across the country, not just specific provinces. The dataset allows for comparison of data across different years within the study period (2008–2019). The dataset includes information on factors like wealth, education, residence, and child’s sex, allowing for analysis of socioeconomic and geographic inequalities. The WHO HEAT makes data analysis and visualisation accessible even for researchers without extensive statistical expertise. However, there are some caveats that reliance on participants’ memory for information like wealth or education can lead to inconsistencies. Cross-sectional design cannot establish causal relationships between factors and immunisation coverage.

Conclusion

The study highlights significant trends in polio immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone from 2008 to 2019, revealing an initial increase followed by a notable decline. The findings suggest that socioeconomic factors such as maternal age, child sex, and maternal education do not significantly influence immunization rates; rather, children from the poorest households and those living in rural areas exhibited better coverage. The main inequality needing to be addressed is subnational inequality particularly in the Western, Northwest, and Northern regions. Therefore, it is recommended that public health strategies prioritize enhancing access to immunization services in the affected regions, potentially through community-based outreach programs, increased funding for health infrastructure, and engaging local leaders to raise awareness about the importance of vaccination. Additionally, ongoing monitoring and evaluation should be implemented to assess the effectiveness of these interventions and ensure equitable coverage across all demographics, ultimately aiming to eliminate the disparities observed in polio immunization rates in Sierra Leone.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to MEASURE DHS and the World Health Organization for making the dataset and the HEAT software accessible.

Abbreviations

- D

Difference

- HEAT

Health Equity Assessment Toolkit

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- PAF

Population Attributable Fraction

- PAR

Population Attributable Risk

- R

Ratio

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

AO contributed to the study design and conceptualisation. AO performed the analysis. AO, AUBS, US, AT, CB, and JBK developed the initial draft. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version. AO had the final responsibility of submitting it for publication.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Data availability

The dataset used can be accessed at https://whoequity.shinyapps.io/heat/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not seek ethical clearance since the WHO HEAT software and the dataset are freely available in the public domain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Poliomyelitis. (polio). https://www.who.int/health-topics/poliomyelitis. 2024. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- 2.Poliomyelitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/poliomyelitis. 2023. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- 3.World Health Organization. State of inequality: childhood immunization. 2016.

- 4.Fekadu H, Mekonnen W, Adugna A, Kloos H, HaileMariam D. Inequities and trends of Polio immunisation among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMJ Open. 2024;14(3):e079570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zegeye B, El-Khatib Z, Oladimeji O, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, et al. Demographic and health surveys showed widening trends in Polio immunisation inequalities in Guinea. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(12):3334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GPEI-Sierra Leone. https://polioeradication.org/where-we-work/sierra-leone/. 2024. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- 7.Sierra Leone concludes First Round of a Nationwide Polio Vaccination. - Sierra Leone | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/sierra-leone/sierra-leone-concludes-first-round-nationwide-polio-vaccination. 2024. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- 8.WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Sierra Leone Confirms New Cases of Polio Variant, Implements Comprehensive Response Plan. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/sierra-leone/news/sierra-leone-confirms-new-cases-polio-variant-implements-comprehensive-response-plan. 2024. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- 9.Statistics Sierra Leone - StatsSL, ICF. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2019. StatsSL/ICF; 2020.

- 10.Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT). Software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. Built-in database edition. Version 6.0. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlotheuber A, Hosseinpoor AR. Summary measures of health inequality: a review of existing measures and their application. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low and middle-income countries. Geneva World Health Organization; 2013.

- 14.Hosseinpoor AR, Nambiar D, Schlotheuber A, Reidpath D, Ross Z. Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT): software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witter S, Brikci N, Harris T, Williams R, Keen S, Mujica A, et al. The free healthcare initiative in Sierra Leone: evaluating a health system reform, 2010-2015. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(2):434–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Sierra Leone Launches the 1st Round of Polio National Immunization Days Campaign. https://www.afro.who.int/news/sierra-leone-launches-1st-round-polio-national-immunization-days-campaign-2012. 2012. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- 17.World Health Organization. Sierra Leone Launches 2nd Round Polio National Immunization Campaign. https://unipsil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/who_sl_launches_2nd_polio_nationalimmunizationcampaign2012.pdf. 2012. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- 18.Jalloh MB, Bah AJ, James PB, Sevalie S, Hann K, Shmueli A. Impact of the free healthcare initiative on wealth-related inequity in the utilization of maternal & child health services in Sierra Leone. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. 2014–2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html. 2020. Accessed March 24, 2024.

- 20.Elston JWT, Moosa AJ, Moses F, Walker G, Dotta N, Waldman RJ et al. Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. J Public Health. 2015;fdv158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sun X, Samba TT, Yao J, Yin W, Xiao L, Liu F, et al. Impact of the Ebola Outbreak on Routine Immunization in Western Area, Sierra Leone - a Field Survey from an Ebola Epidemic Area. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brolin Ribacke KJ, van Duinen AJ, Nordenstedt H, Höijer J, Molnes R, Froseth TW et al. The Impact of the West Africa Ebola Outbreak on Obstetric Health Care in Sierra Leone. Bouchama A, editor. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0150080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mutua MK, Kimani-Murage E, Ettarh RR. Childhood vaccination in informal urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya: who gets vaccinated? BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborne A, Sesay U, Tommy A, Bangura C, Ahinkorah BO. Inequalities in measles immunization coverage among two-year-olds in Sierra Leone, 2008–2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Kim R, Subramanian SV. Economic-related inequalities in child health interventions: an analysis of 65 low-and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2021;277:113816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsawe M, Susuman AS. Inequalities in maternal Healthcare use in Sierra Leone: evidence from the 2008–2019 demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0276102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Government of Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, COMPREHENSIVE EPI MULTI-YEAR. PLAN 2012–2016. https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/country_docs/Sierra%20Leone/cmyp-_2012-2016_narrative_for_sierra_leone_final_updated_on_the_23_jan_2014.pdf. 2014. Accessed October 12, 2024.

- 28.Raru TB, Ayana GM, Zakaria HF, Merga BT. Association of higher Educational Attainment on Antenatal Care utilization among pregnant women in East Africa Using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 2010 to 2018: a Multilevel Analysis. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amwonya D, Kigosa N, Kizza J. Female education and maternal health care utilization: evidence from Uganda. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adedokun ST, Adekanmbi VT, Uthman OA, Lilford RJ. Contextual factors associated with health care service utilization for children with acute childhood illnesses in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caviglia M, Dell’Aringa M, Putoto G, Buson R, Pini S, Youkee D, Jambai A, Vandy MJ, Rosi P, Hubloue I, Della Corte F. Improving access to healthcare in Sierra Leone: the role of the newly developed national emergency medical service. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used can be accessed at https://whoequity.shinyapps.io/heat/.