Abstract

Background

To investigate the associations between relative fat mass (RFM) and clinical outcomes in different glucose tolerance statuses and the modified effect of glucose tolerance status.

Methods

We analyzed 8,224 participants from a Chinese cohort study, who were classified into normal glucose status (NGT), prediabetes, and diabetes. Outcomes included fatal, nonfatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and all-cause mortality. Associations between RFM and outcomes were assessed using Cox regression. The modified effect of glucose tolerance status was investigated using mediation, interaction, and joint analyses.

Results

During up to 5 years of follow-up, 154 (1.9%) participants experienced fatal CVD, 153 (1.9%) experienced nonfatal CVD events, and 294 (3.6%) experienced all-cause death. 2,679 participants (32.6%) had NGT, 4,528 (54.8%) had prediabetes, and 1,037 (12.6%) had diabetes. RFM was associated with increased risk of fatal (HR [95% CI], 1.09 [1.06–1.12], p < 0.001), nonfatal CVD events (HR [95% CI], 1.12 [1.09–1.15], p < 0.001), and all-cause mortality (HR [95% CI], 1.10 [1.08–1.12), p < 0.001) in all and those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, and these associations were modified by glucose tolerance status, which included mediating (mediation proportion ranges from 4.74% to 8.69%) and synergistic interactive effects (multiplicative effect ranges from 1.03 to 1.06). The joint analysis identified the subclassification that exhibited the highest HR among 12 subclassifications.

Conclusions

RFM was associated with increased risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, and these associations were modified by glucose tolerance status, which could significantly influence how clinicians assess high risk and could lead to more personalized, effective prevention strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-024-01558-8.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, All-cause mortality, Glucose tolerance statuses, Relative fat mass, Mediation analysis, Interaction analysis, Joint analysis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. The global burden of this disease continues to rise and is estimated to cause 24 million deaths per year by 2030 [1]. Despite advances in treatment, the global burden continues to rise, highlighting the need for early detection. Obesity, a key risk factor for CVD and mortality, has become more common over recent decades, contributing to the “obesity epidemic” [2–6]. Therefore, accurate obesity screening is essential [2–6]. Body mass index (BMI) is commonly used for obesity screening, but it does not distinguish between fat and lean mass. Although more accurate methods exist, such as bioelectrical impedance and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, they are expensive and impractical for routine use. There is a need for simpler, cost-effective methods to assess obesity and CVD risk [2–6].

After a thorough examination of 365 possible measurements, Woolcott et al. found that relative fat mass (RFM) was the most accurate anthropometric measure for predicting whole-body fat percentage in a multi-ethnic cohort [7]. RFM, a sex-specific index based on height and waist circumference (WC), has been linked to CVD and all-cause mortality in the general population [2–7]. However, previous studies have not examined the relationship between RFM and CVD or mortality in populations with different glucose tolerance statuses (NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes) [2, 4–6, 8]. It remains unclear whether glucose tolerance status modifies these associations and influences clinical risk assessment. Additionally, Paek's study found that RFM overestimated body fat by 1.32% in men and 2.63% in women in the Korean population [9]. While RFM was developed for Mexican, European, and African Americans, its accuracy in Asian populations, including China, is uncertain and requires further validation [10]. Shen et al. found RFM associated with a 66% increased risk of CVD in a Chinese study [8], but no cohort studies have yet explored its relationship with all-cause mortality in Asian populations.

To address knowledge gaps, this study analyzed data from the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4C) to examine the relationship between RFM and the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality across different glucose tolerance statuses (NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes). Mediation and interaction analyses were used to explore how glucose tolerance modifies these associations. The joint analysis identified the subclassification with the highest HR for risk assessment. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was performed to assess the dose–response relationship between RFM and outcomes and identify potential RFM cutoffs. Finally, we compared the predictive performance of RFM with other obesity indices (BMI, WC, and WHR [waist-hip ratio]) for CVD and mortality risk across glucose tolerance statuses.

Materials and methods

Ethics committee statement

The Committee on Human Research at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved the study protocol (Numbers: 14/2004 and TJ-IRB20231125), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in compliance with the guidelines for cohort studies established by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Research in Epidemiology (STROBE) [11].

Study population

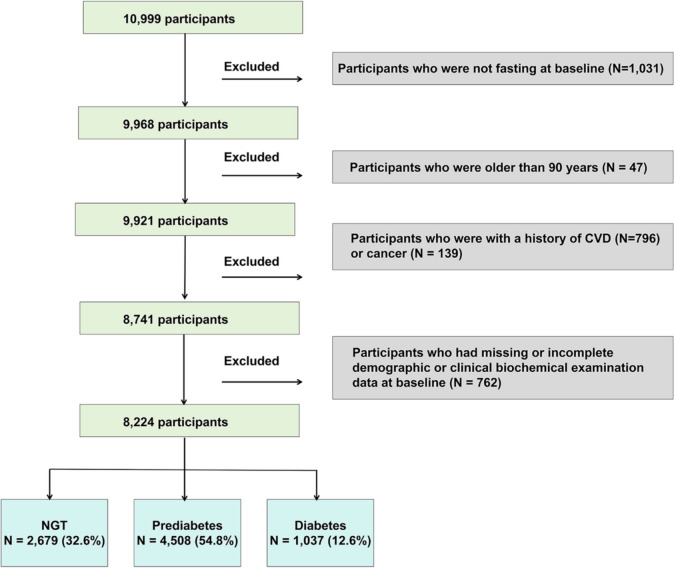

In this retrospective cohort study, 10,999 participants were included from Hubei Province, as part of the 4C study during 2011–2012 (baseline), which invited participants to attend follow-up visits during 2014–2016 [12–20]. Individuals who were 40 years of age or older and met the necessary criteria were selected from the resident registration systems. Community health workers who had received training visited the homes of eligible persons and extended invitations for their participation in the research. Individuals who provided their permission and consented to participate in the study were promptly booked for a face-to-face interview and a visit to the clinic within one week after being included. We excluded participants who were not fasting at baseline (N = 1,031), older than 90 years old (N = 47), with a history of CVD (N = 796) or cancer (N = 139), had missing or incomplete demographic or clinical biochemical examination data at baseline (N = 762) at baseline (Fig. 1). Finally, 8224 participants were included in the analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the cohort study. CVD cardiovascular disease, NGT normal glucose tolerance

Data collection

Baseline and follow-up data were gathered from neighborhood community clinics [14–16]. Trained staff used a standard questionnaire to gather information on family history, lifestyle variables, illness history, medication history, and sociodemographic traits. Clinical staff members with training and certification from nearby community clinics collected data and measured anthropometrically. Trained personnel measured the subjects' height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, waist and hip circumferences. More detailed descriptions of data collection are provided in the Supplementary materials.

Outcomes

Hospital records and death certificates were used to confirm all results. The primary outcomes are CVD events, which were defined as the combination of new fatal or nonfatal CVD events. Fatal CVD events encompassed all deaths due to CVD [21]. Nonfatal CVD events included myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke [21]. The secondary outcome was overall mortality. Data on participants were recorded at baseline, on the date of a CVD event, on the date of a non-CVD death, and at the end of the follow-up period.

Mediation analyses, interaction analyses, and joint analyses

We performed mediation analyses to investigate the potential mediation role of glucose tolerance status (mediator) in the association between RFM (exposure) and risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality (outcomes). In the interaction analyses of the present study, we investigated the potential interactive role of glucose tolerance status in the associations between RFM and risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality by calculating the additive and multiplicative effect. To identify specifically which populations exhibit high risk and low risk for outcomes, we assessed the joint associations as the methods previously reported [22]. More detailed descriptions are provided in the Supplementary materials.

Statistical analysis

The cohort was divided into four groups based on its RFM quartile ranges, which were quartile 1 (Q1), Q2, Q3, and Q4. We compared the baseline characteristics and the frequencies of outcomes according to RFM quartile groups in all participants and those with different glucose statuses, respectively. Also, we compared the baseline characteristics according to different glucose statuses including NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes. Continuous variables that have a symmetric distribution were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas variables having a skewed distribution were provided as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were quantified using numerical values, namely frequencies and percentages. The baseline characteristics of participants in different groups were compared using several statistical tests. One-way analysis of covariance was used for symmetrically distributed continuous data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for characteristics having a skewed distribution, and the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

We conducted time-to-event analyses using Cox proportional hazard regression models to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the “survminer” R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html). The covariates in fully adjusted regression models were generated according to previous publications and potential risk factors related to the development and progression of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality from clinical experience [21, 23]. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 3 was adjusted for all variables in Model 2 plus (systolic blood pressure) SBP, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG), alanine transaminase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), creatinine, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, lipid-lowering drug, and diabetes therapy at baseline. We furthermore conducted the subgroup analyses according to subgroups of sex (male/female), age (< 60/ ≥ 60 years old), and hypertension (no/yes). Potential dose-dependent relationships between RFM and outcomes were examined by RCS using the “rms” R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html). The mediation analyses were conducted using the “mediation” R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mediation/index.html). The bootstrap testing method involving resampling 1000 times was set to calculate the CIs, which does not require a prior assumption of the sampling distribution [24, 25]. The interaction analyses were conducted using the “epiR” R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/epiR/index.html). CIs calculations are based on the delta method described by Hosmer and Lemeshow [24, 25]. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to estimate the predictive performance of possible predictors for CVD and all-cause mortality by the area under the curve (AUC). We furthermore compared the AUCs between RFM and other obesity indices including BMI, WC, and WHR in all participants and those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, respectively. A 2-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered significant. R (version 4.4.1) was used for all of the analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline analysis included 8,224 participants (Fig. 1), 34.30% of whom were male, with an average age of 60.12 ± 10.56 years old (Table 1). 2679 participants (32.6%) had NGT, 4508 (54.8%) had prediabetes, and 1037 (12.6%) had diabetes. In all participants, compared with those in the lowest RFM quartile group, individuals in the higher quartile groups were more likely to have higher levels of BMI, WHR, WC, SBP, 2 h plasma glucose concentration (PG2h), and blood lipids, and higher percentages of hypertension and dyslipidemia (P values < 0.05) (Table 1). In participants with NGT, compared with those in the lowest RFM quartile group, individuals in the higher quartile groups were more likely to have higher levels of BMI, WHR, WC, SBP, PG2h, and blood lipids, and a higher percentage of hypertension (P values < 0.05) (Table S1). In participants with prediabetes, compared with those in the lowest RFM quartile group, individuals in the higher quartile groups were more likely to have higher levels of BMI, WHR, WC, SBP, blood lipids, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and PG2h and a higher percentage of hypertension (P values < 0.05) (Table S2). In participants with diabetes, compared with those in the lowest RFM quartile group, individuals in the higher quartile groups were more likely to have higher levels of BMI, WHR, WC, SBP, blood lipids, ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and creatinine and higher percentages of hypertension and dyslipidemia (P values < 0.05) (Table S3). In addition, with the deterioration of glucose metabolism, the levels of RFM, BMI, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, blood lipids, ALT, GGT, and creatinine, and the percentages of hypertension and dyslipidemia were elevated (Table S4).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline demographic characteristics stratified according to RFM quartiles in all participants

| Characteristics | All participants | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 8224 | 2244 (27.3) | 2205 (26.8) | 1769 (21.5) | 2006 (24.4) | |

| RFM | 32.08 ± 8.23 | 21.47 ± 5.46 | 30.81 ± 2.35 | 36.59 ± 1.12 | 41.37 ± 2.21 | < 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 2821 (34.3) | 1935 (86.2) | 607 (27.5) | 67 (3.8) | 212 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age (y) | 60.12 ± 10.56 | 61.17 ± 10.10 | 58.92 ± 10.85 | 58.62 ± 10.56 | 61.59 ± 10.42 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.51 ± 3.45 | 19.86 ± 1.16 | 22.45 ± 0.60 | 24.41 ± 0.57 | 27.96 ± 3.16 | < 0.001 |

| WHR | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 80.67 ± 9.51 | 69.67 ± 4.48 | 78.04 ± 1.84 | 83.81 ± 1.74 | 93.10 ± 6.00 | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 150.03 ± 23.84 | 149.43 ± 23.30 | 148.35 ± 24.14 | 148.36 ± 22.92 | 154.02 ± 24.46 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.32 ± 12.16 | 81.44 ± 12.66 | 80.61 ± 11.97 | 80.73 ± 11.72 | 82.48 ± 12.08 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) | 5.80 ± 0.87 | 5.71 ± 0.71 | 5.76 ± 0.73 | 5.78 ± 0.79 | 5.98 ± 1.17 | < 0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.82 ± 4.17 | 5.97 ± 5.22 | 5.57 ± 2.80 | 5.62 ± 3.39 | 6.10 ± 4.68 | < 0.001 |

| PG2h (mmol/L) | 6.82 ± 2.73 | 6.40 ± 2.36 | 6.63 ± 2.50 | 6.80 ± 2.48 | 7.51 ± 3.37 | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.50 ± 1.10 | 1.35 ± 1.11 | 1.43 ± 1.03 | 1.54 ± 1.10 | 1.72 ± 1.15 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.08 ± 0.95 | 4.92 ± 0.92 | 5.03 ± 0.91 | 5.13 ± 0.95 | 5.28 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.52 ± 0.36 | 1.56 ± 0.39 | 1.54 ± 0.35 | 1.51 ± 0.34 | 1.46 ± 0.33 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.88 ± 0.79 | 2.73 ± 0.75 | 2.83 ± 0.76 | 2.93 ± 0.81 | 3.05 ± 0.81 | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.37 ± 13.05 | 16.53 ± 14.26 | 14.90 ± 11.77 | 14.39 ± 10.75 | 15.47 ± 14.63 | < 0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.87 ± 14.69 | 27.44 ± 17.83 | 24.24 ± 12.27 | 23.21 ± 10.18 | 24.13 ± 16.16 | < 0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 28.93 ± 48.70 | 34.87 ± 57.43 | 26.00 ± 27.71 | 24.87 ± 55.79 | 29.08 ± 48.83 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 63.78 ± 14.08 | 67.83 ± 16.45 | 62.57 ± 12.64 | 60.22 ± 9.66 | 63.71 ± 14.89 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 1323 (16.1) | 910 (40.6) | 264 (12.0) | 45 (2.5) | 104 (5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol (%) | 1720 (20.9) | 992 (44.2) | 375 (17.0) | 135 (7.6) | 218 (10.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 2106 (25.6) | 437 (19.5) | 526 (23.9) | 460 (26.0) | 683 (34.0) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 60 (0.7) | 14 (0.6) | 8 (0.4) | 17 (1.0) | 21 (1.0) | 0.036 |

| Diabetes (%) | 355 (4.3) | 61 (2.7) | 101 (4.6) | 63 (3.6) | 130 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hypotensive drug (%) | 1085 (13.2) | 212 (9.4) | 267 (12.1) | 236 (13.3) | 370 (18.4) | < 0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering drug (%) | 11 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 0.440 |

| Diabetes therapy (%) | 220 (2.7) | 40 (1.8) | 57 (2.6) | 41 (2.3) | 82 (4.1) | < 0.001 |

The quartile ranges were Q1 (0–26), Q2 (26–33), Q3 (33–38) and Q4 (38–59)

Data are presented as the means ± SDs or numbers (%)

RFM relative fat mass, SDs standard deviations, BMI body mass index, WHR waist-hip ratio, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TG triglycerides, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, FPG fasting plasma glucose, PG2h 2-h plasma glucose, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase

The associations between RFM and the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and different glucose tolerance statuses

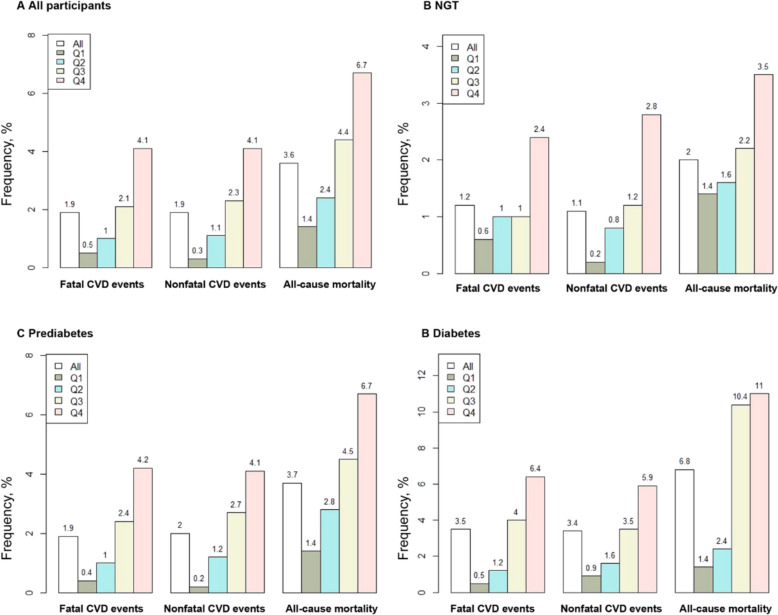

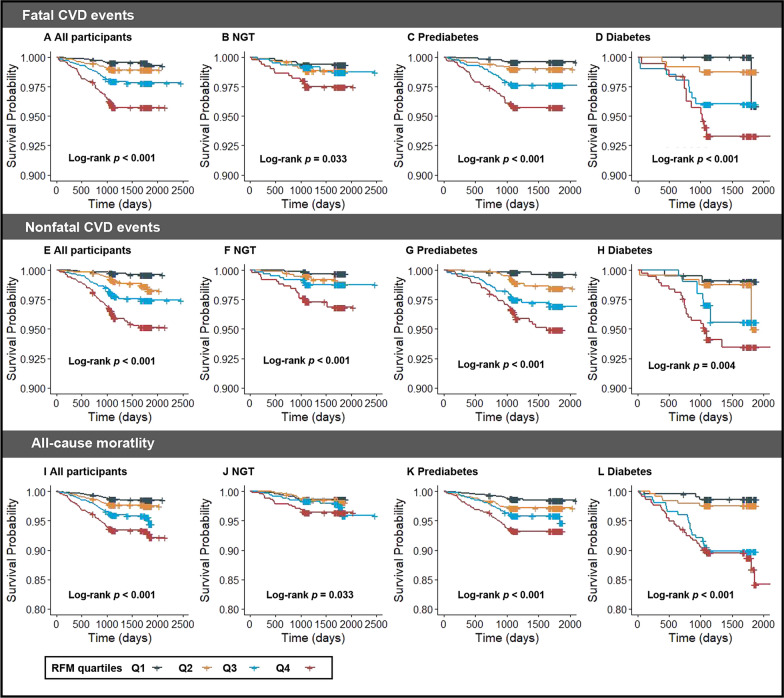

During up to 5 years of follow-up, of the 8,224 participants, 307 (3.8%) individuals experienced CVD events, including 154 (1.9%) fatal CVD events and 153 (1.9%) nonfatal CVD events (Table S5). A total of 294 (3.6%) participants experienced all-cause death (3.6%) (Table S5). In all participants, the percentage of fatal CVD, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in the highest RFM quartile was higher than those in the other lower RFM quartiles (Table S5, Fig. 2). Similarly, the percentages of outcomes in participants with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes also increased with the elevated level of RFM (Table S5, Fig. 2). Kaplan–Meier curves revealed that the cumulative incidence of fatal CVD was significantly higher in the fourth RFM quartile than in the other lower quartiles in all participants and those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes (log-rank p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and populations with different glucose tolerance statuses. A All participants, B NGT, C prediabetes, and (D) diabetes. RFM relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease

Fig. 3.

Kaplan‒Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of outcomes. Kaplan‒Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of fatal CVD events: A all participants, B NGT, C prediabetes, and D diabetes. Kaplan‒Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of nonfatal CVD events: E all participants, F NGT, G prediabetes, and H diabetes. Kaplan‒Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality: I all participants (J) NGT (K) prediabetes, and (L) diabetes. RFM, relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease

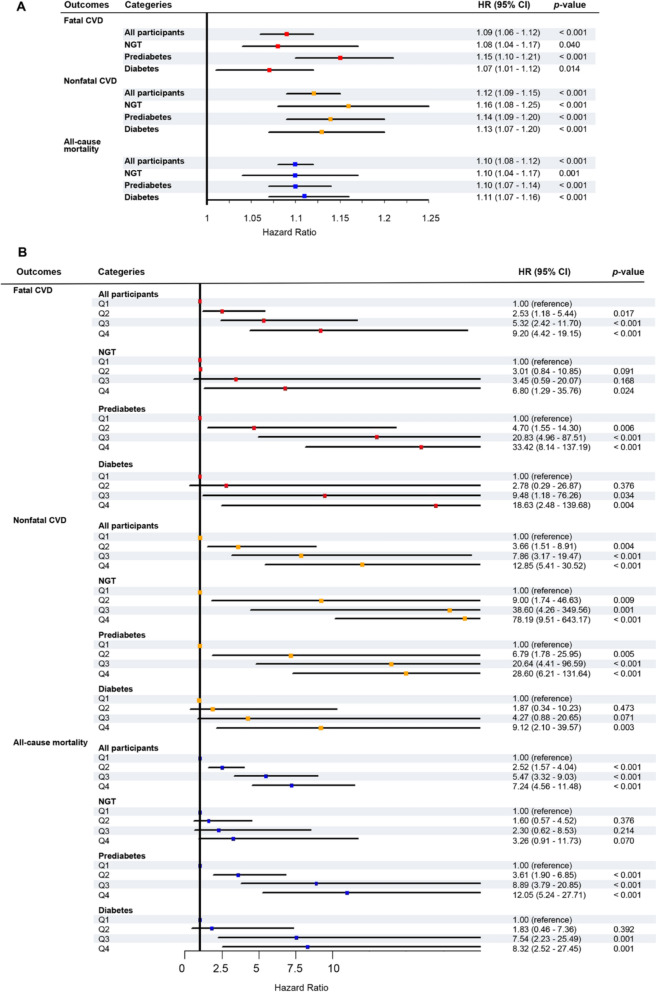

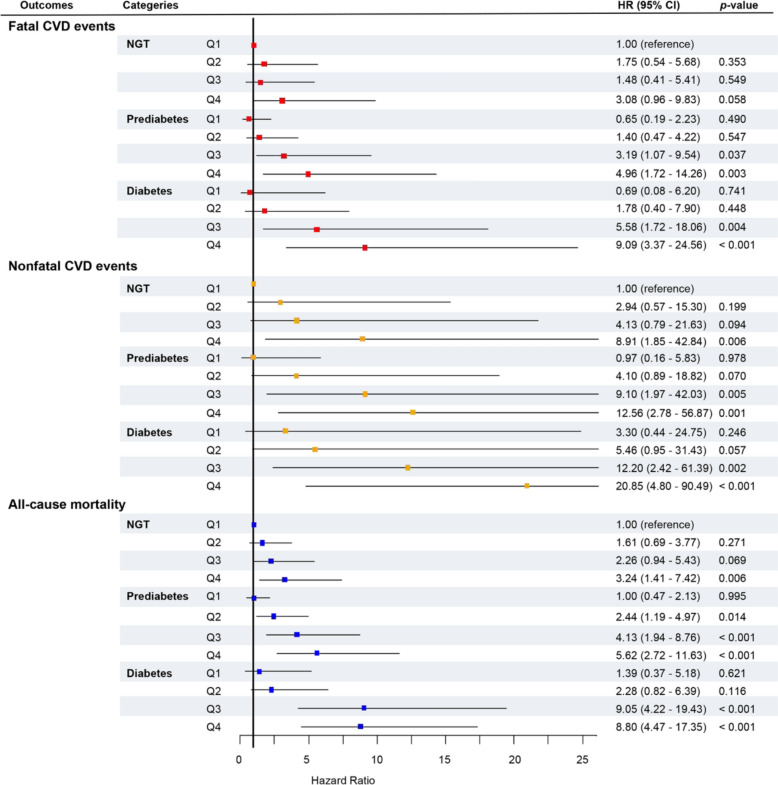

Cox proportional hazard regressions indicated that the associations between RFM and outcomes were significant in all glucose tolerance statuses, which were shown in Fig. 4, Table S6, and Table S7. First, when RFM was calculated as a continuous variable, after full adjustment, elevated RFM levels were associated with a higher risk of fatal CVD events in all participants (HR [95% CI], 1.09 [1.06–1.12], p < 0.001) and those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes (Fig. 4A, Table S6). In addition, considering nonfatal CVD events as the outcome, those with NGT exhibited significant HRs, which was similar to those with prediabetes and diabetes after full adjustment (Fig. 4A, Table S6). The higher levels of RFM, the higher the risk for all-cause mortality, which was observed in those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes after full adjustment (Fig. 4A, Table S7). Second, we calculated the HRs using RFM as a categorical variable according to RFM quartile ranges. The fourth RFM quartile displayed a higher risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality compared with the first quartile in all glucose tolerance statuses (Fig. 4B, Table S6-7).

Fig. 4.

The forest plots showed the adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) of RFM for fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and populations with different glucose tolerance statuses. RFM as a continuous variable. (B) RFM as a categorical variable according to RFM quartiles. The models were adjusted for age, sex, SBP, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, creatinine, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, lipid-lowering drug, and diabetes therapy at baseline. RFM, relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, SBP systolic blood pressure, TG triglycerides, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, ALT alanine transaminase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase

The subgroup analyses

First, considering fatal CVD events as the outcome, the subgroup analyses (Table 2) showed that in all participants, the relationships between RFM and fatal CVD events were more prominent in the subgroups of females and those with hypertension (p for interaction < 0.05). In participants with prediabetes, the relationship was more notable in the subgroups those of aged < 60 years old (p for interaction = 0.009) (Table 2). In participants with diabetes, the relationship was stronger in the subgroups of females, those aged ≥ 60 years old, and those with hypertension (p for interaction < 0.05) (Table 2). Second, considering nonfatal CVD events as the outcome, in participants with NGT, the relationship was more pronounced in the subgroups of those without hypertension (p for interaction = 0.006) (Table 2). Third, considering all-cause mortality as the outcome, in all participants and those with diabetes, the relationship between RFM and all-cause mortality was more obvious in the subgroup of females (p for interaction < 0.05) (Table 2). In participants with NGT, the relationship was more prominent in the subgroups of those aged ≥ 60 years old, while it was stronger in subgroups of those aged < 60 years old in those with prediabetes (p for interaction < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the hazard ratios of outcomes of RFM in all participants and populations with different glucose tolerance statuses

| All participants | NGT | Prediabetes | Diabetes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | p for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P value | p for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P value | p for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P value | p for interaction | |

| Fatal CVD | ||||||||||||

| Sex | < 0.001 | 0.586 | 0.908 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.915 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | 0.302 | 1.17 (1.03–1.33) | 0.017 | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | 0.029 | ||||

| Female | 1.19 (1.14–1.24) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 0.007 | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.25 (1.15–1.35) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Age, years old | 0.624 | 0.710 | 0.009 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| < 60 | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 0.002 | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.496 | 1.25 (1.14–1.36) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.121 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.016 | 1.09 (1.05–1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06–1.24) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.027 | 0.260 | 0.327 | 0.012 | ||||||||

| No | 1.08 (1.04–1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.344 | 1.12 (1.07–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.96–1.06) | 0.851 | ||||

| Yes | 1.15 (1.09–1.21) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 0.044 | 1.17 (1.08–1.27) | < 0.001 | 1.16 (1.05–1.29) | 0.004 | ||||

| Nonfatal CVD | ||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.199 | 0.788 | 0.537 | 0.903 | ||||||||

| Male | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | 0.011 | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) | 0.009 | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 0.149 | ||||

| Female | 1.15 (1.11–1.20) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.09–1.22) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.07–1.22) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Age, years old | 0.570 | 0.390 | 0.229 | 0.994 | ||||||||

| < 60 | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) | 0.174 | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.00–1.22) | 0.040 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) | 0.001 | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 0.006 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.290 | 0.006 | 0.385 | 0.079 | ||||||||

| No | 1.14 (1.09–1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.18 (1.08–1.28) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.09–1.21) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.124 | ||||

| Yes | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 0.961 | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.18 (1.07–1.31) | 0.001 | ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.010 | 0.844 | 0.961 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) | 0.017 | 1.13 (1.05–1.23) | 0.002 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.954 | ||||

| Female | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.05–1.21) | 0.001 | 1.13 (1.08–1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.21 (1.14–1.28) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Age, years old | 0.162 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.687 | ||||||||

| < 60 | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | < 0.001 | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.211 | 1.21 (1.14–1.29) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 0.004 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | < 0.001 | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.05–1.16) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.610 | 0.509 | 0.808 | 0.403 | ||||||||

| No | 1.09 (1.06–1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 0.026 | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1.10 (1.06–1.13) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (1.01–1.17) | 0.026 | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06–1.24) | < 0.001 | ||||

NGT normal glucose status, RFM relative fat mass, CVD cardiovascular diseases, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

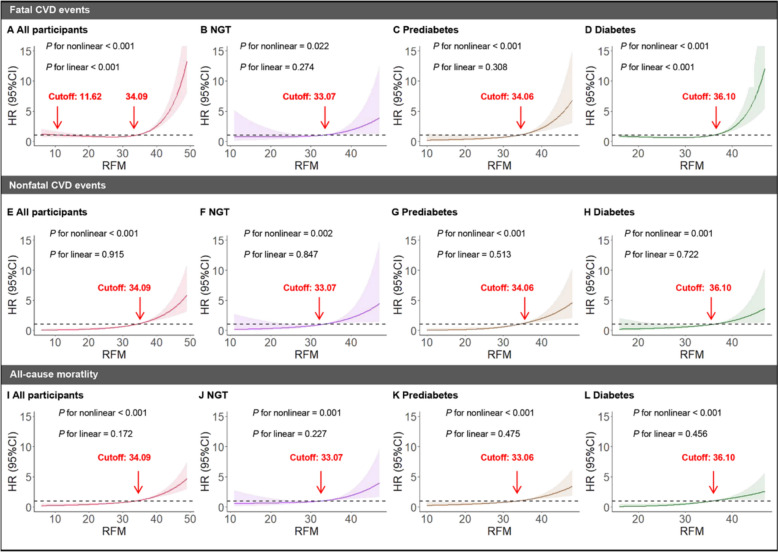

The dose–response associations between RFM and the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and different glucose tolerance statuses

RCS analyses revealed dose–response associations between RFM and the risk of fatal CVD events in all participants (Fig. 5A) and different glucose tolerance statuses including NGT (Fig. 5B), prediabetes (Fig. 5C), and diabetes (Fig. 5D). We also calculated the cutoffs of RFM respectively, which indicated that those with higher RFM values exceeding the relative cutoff are at a higher risk of fatal CVD events. Similarly, RFM and the risk of nonfatal CVD events (Fig. 5E–H) and all-cause mortality (Fig. 5I–L) exhibited dose–response associations in all participants and different glucose tolerance statuses.

Fig. 5.

RCS showed the dose–response relationship between RFM and risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and populations with different glucose tolerance statuses. risk of fatal CVD events: A all participants, B NGT, C prediabetes, and D diabetes. risk of nonfatal CVD events: E all participants, F NGT, G prediabetes, and H diabetes. risk of all-cause mortality: I all participants, J NGT, K prediabetes, and L diabetes. RCS restricted cubic splines, RFM, relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease

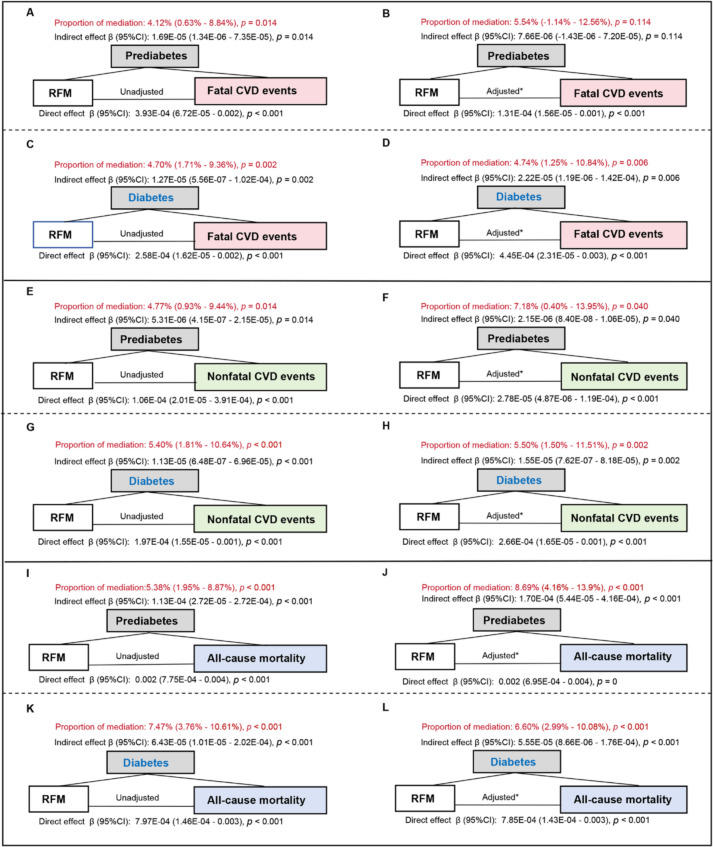

The mediating effect of glucose tolerance status in the associations between RFM and the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality

Mediation analyses (Fig. 6) showed that prediabetes and diabetes mediated the association between RFM and fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in unadjusted and adjusted models except when prediabetes was the mediator and fatal CVD events were the outcome in the adjusted model (Fig. 6 B). More specifically, the mediation proportion of prediabetes in the association between RFM and fatal CVD events was significant in the unadjusted model (4.12% [0.63%–8.84%], p = 0.014) (Fig. 6A), while nonsignificant in the adjusted model (Proportion of mediation: 5.54% [−1.14%–12.56%], p = 0.114) (Fig. 6B). When considering diabetes as the mediator, the mediating effects were significant both in the unadjusted (Fig. 6C) and adjusted models (Fig. 6D). Similarly, when considering nonfatal CVD events as the outcome, prediabetes exhibited a mediation proportion of 7.18% (Fig. 6F) and diabetes exhibited 5.50% (Fig. 6H) after adjustment. When considering all-cause mortality as the outcome, prediabetes displayed a mediation proportion of 8.69% (Fig. 6J) and diabetes exhibited 6.60% (Fig. 6L) after adjustment.

Fig. 6.

The mediating effect of glucose tolerance status in the associations between RFM and risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality. Considering fatal CVD events as the outcome: prediabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (A) and adjusted model (B); diabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (C) and adjusted model (D). Considering nonfatal CVD events as the outcome: prediabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (E) and adjusted model (F); diabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (G) and adjusted model (H). Considering all-cause mortality as the outcome: prediabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (I) and adjusted model (J); diabetes as the mediator in the unadjusted model (K) and adjusted model (L). *The adjusted models were adjusted for age, sex, SBP, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, creatinine, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, lipid-lowering drug, and diabetes therapy at baseline. RFM relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, SBP systolic blood pressure, TG triglycerides, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, ALT alanine transaminase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase

Interaction analyses of RFM and glucose tolerance status on the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality

We observed significant multiplicative interactive effects between RFM and prediabetes and diabetes on fatal (multiplicative effect: 1.06), nonfatal CVD events (multiplicative effect:1.03), and all-cause mortality (multiplicative effect:1.06) after adjustment except between RFM and prediabetes on nonfatal CVD events (Table 3). Whereas, the additive effect between RFM and glucose tolerance status was nonsignificant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interactive effects of RFM and glucose tolerance status on outcomes

| Outcomes | Interactive items | Glucose tolerance status | Unadjusted model | Fully adjusted model* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | |||

| Fatal CVD events | ||||

| Additive effects | ||||

| RERI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | −0.04 (−0.07–−0.01) | −0.06 (−0.12–−0.01) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.11 (−0.17–0.38) | 0.07 (−0.22–0.35) | ||

| AP | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | −0.21 (−0.71–0.29) | −0.25 (−0.94–0.44) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.06 (−0.01–0.13) | ||

| SI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 1.79 (0.97–1.67) | ||

| Multiplicative effect | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.07 (1.00–1.13) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | ||

| Nonfatal CVD events | ||||

| Additive effects | ||||

| RERI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | −0.02 (−0.16–0.11) | −0.04 (−0.24–0.15) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.11 (−0.42–0.64) | −0.02 (−0.18–0.14) | ||

| AP | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | −0.04 (−0.34–0.27) | −0.06 (−0.47–0.35) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.05 (−0.05–0.15) | −0.03 (−0.44–0.37) | ||

| SI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) | 1.19 (0.82–1.73) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | ||

| Multiplicative effect | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | ||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| Additive effects | ||||

| RERI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 0.03 (−0.08–0.13) | 0.09 (−0.20–0.38) | ||

| Diabetes | −0.01 (−0.09–0.08) | 0.00 (−0.12–0.12) | ||

| AP | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 0.02 (−0.03–0.07) | 0.07 (−0.05–0.19) | ||

| Diabetes | −0.01 (−0.19–0.17) | 0.00 (−0.24–0.23) | ||

| SI | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.11 (0.73–1.68) | 1.39 (0.43–4.54) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.02 (0.86–1.20) | 1.01 (0.78–1.29) | ||

| Multiplicative effect | NGT | Reference | Reference | |

| Prediabetes | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | ||

In the absence of an interactive effect, RERI and AP were equal to 0, SI was 1, and the multiplicative effect was 1

*The fully adjusted model was adjusted for age, sex, SBP, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, creatinine, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, lipid-lowering drug, and diabetes therapy at baseline

RFM relative fat mass, CVD cardiovascular diseases, RERI relative excess risk due to interaction, AP proportion attributable to interaction, SI synergy index, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, SBP systolic blood pressure, TG triglycerides, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, ALT alanine transaminase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase

Joint analyses of RFM and glucose tolerance status on the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality

Figure 7 showed the joint association of RFM and glucose tolerance status on the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality after adjusting for confounders. Compared with individuals with NGT and RFM falling in Q1, the highest HRs were observed in individuals with diabetes and RFM falling in Q4 for fatal CVD events and nonfatal CVD events among 12 distinct classifications. Individuals with diabetes and RFM falling in Q3 for all-cause mortality also achieved the highest HR which was slightly higher than individuals with diabetes and RFM falling in Q4 with individuals with NGT and RFM falling in Q1 as the reference among 12 distinct classifications.

Fig. 7.

Joint effects of RFM and glucose tolerance statuses on nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality. The models were adjusted for age, sex, SBP, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, creatinine, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, lipid-lowering drug, and diabetes therapy at baseline. RFM, relative fat mass, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, SBP systolic blood pressure, TG triglycerides, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, ALT alanine transaminase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase

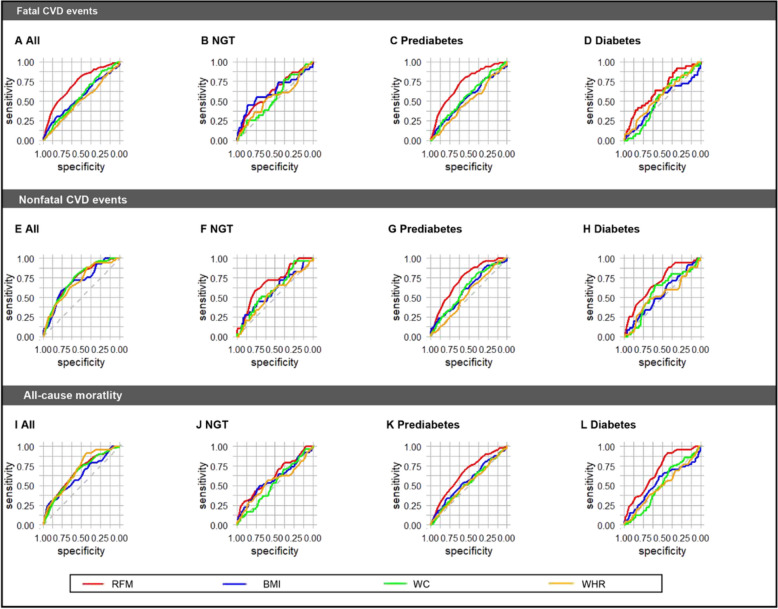

Comparison of the predictive performance of ROC curves of RFM with that of other obesity indices including BMI, WC, and WHR for the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in different glucose tolerance statuses.

The ROC analyses (Fig. 8, Table S8) revealed that the AUC of RFM exhibited the highest predictive performance compared with other obesity indices including BMI, WC, and WHR for the risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in all participants and those with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes. Although some comparisons had no significant difference (Table S8), this is probably due to the low number of outcomes reducing statistical power.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of predictive performances of ROC curves for fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality between RFM and other obesity indices in all participants and populations with different glucose tolerance statuses. Considering fatal CVD events as the outcome: A all participants, B NGT, C prediabetes, and D diabetes. Considering nonfatal CVD events as the outcome: E all participants, F NGT, G prediabetes, and H diabetes. Considering all-cause mortality as the outcome: I all participants, J NGT, K prediabetes, and L diabetes. ROC receiver operator characteristic, NGT normal glucose tolerance, CVD cardiovascular disease, RFM relative fat mass, BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, WHR waist-hip ratio

Discussion

Our retrospective cohort study found that the elevated baseline RFM was associated with an increased risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, and these associations were modified by glucose tolerance statuses. We identified mediating and synergistic effects in the associations between RFM and outcomes, and through joint analysis, we pinpointed the subclassification with the highest HR among 12 groups. These findings could influence clinicians' assessment of high-risk cases and lead to more personalized prevention strategies. In addition, RCS analyses indicated the dose–response relationships between RFM and the outcomes and identified the potential RFM cutoffs. Finally, among all obesity indices including RFM, BMI, WC, and WHR, RFM displayed the largest predictive performance in all glucose tolerance statuses.

Our study reiterates the associations between RFM and the risk of CVD events and all-cause mortality, which is consistent with previous studies [4, 5, 8, 26–28]. The present study corroborated these associations and extended these in the Asian population with cohort epidemiological evidence. Mechanically, excessive body fat (increased RFM levels) causes adipocyte dysfunction by aberrant release of pro-inflammatory and adipocytokines, which may be involved in vascular dysfunction and systemic insulin resistance, subsequently triggering CVD and death [2–6, 8]. However, previous studies only focused on the general population. The evidence on populations with NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, respectively is scarce [2, 4–6, 8]. The present study revealed that the associations between RFM and outcomes were significant in all glucose tolerance statuses, respectively. In line with our result, Asgari et al. reported that general obesity defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 increased the risk of CVD mortality and all-cause mortality events in all glucose tolerance statuses, respectively, from three longitudinal Iran studies [29]. However, Asgari et al. reported that the association considering the outcomes of CVD was non-significant [29]. We assume this is because the reason that Asians exhibit several morphological characteristics and have a shorter height, greater percentage of body fat, and substantially bigger trunk adiposity and waist circumference compared with Caucasians of the same age and BMI, which are risk factors for CVD and death [30].

Furthermore, the modified effects including mediating and interactive roles of glucose tolerance status in the associations between RFM and fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality have been less addressed. The present study therefore delved into the mediation analysis, interaction analysis, and joint analysis. Firstly, mediation analysis found that glucose tolerance status partially mediated the associations between RFM and risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. Consistently, Suthahar et al. found RFM is strongly associated with new-onset diabetes from a prospective cohort study in the Netherlands [3]. Lu et al. reported that BMI was linked to diabetes in a cohort study including 20,944 participants in the NAGALA [31]. Mechanically, obesity (high levels of RFM) causes adipose tissue fibrosis by increased rates of fibrogenesis, strengthens inflammation by increased proinflammatory macrophage and T cell content, and the production of exosomes, leading to both insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, and finally results in prediabetes and diabetes [32–35]. Furthermore, prediabetes and diabetes could induce CVD and death via abnormalities in cardiac metabolism, physiological and pathophysiological signaling, and the mitochondrial compartment, in addition to oxidative stress, inflammation, myocardial cell death pathways, and neurohumoral mechanisms [21]. Healthcare practitioners should assess glucose tolerance status in persons with high RFM, leading to more personalized, effective prevention strategies.

Secondly, interaction analysis revealed significant multiplicative interactive effects between RFM and glucose tolerance status on fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality, which indicated that RFM and prediabetes and diabetes could induce CVD and death in a synergistic method. In line with our study, Shen et al. also found the synergistic effects of obesity and high hemoglobin A1c status on increased levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in a cross-sectional Chinese study that included 1,630 adults aged 18–75 years [36]. Xu et al. found the interactive effect of diabetes with BMI for survival among 4,515 recipients of liver transplants [37]. The multiplicative interactive effect means that the combined effect is larger than the product of the individual effects of RFM and prediabetes and diabetes. We assumed this synergistic effect may be due to a positive feedback mechanism between RFM and prediabetes and diabetes. On the one hand, obesity leads to prediabetes and diabetes by both insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction via pathways about fibrogenesis and inflammation [32]. On the other hand, prediabetes and diabetes cause obesity by: (i). improper metabolism of glucose in cells, leading to an excessive generation of reactive oxygen species, which harm cellular function and insulin receptors, causing insulin resistance and therefore adipose tissue accumulation [32, 36, 37]. (ii). hyperglycemia is often accompanied by an elevation of free fatty acids [32, 36, 37]. Hence, the reciprocal promotion of high RFM and hyperglycemia contributes to the development of metabolic and inflammation disorders, exacerbating the progression of CVD and mortality [32, 36, 37]. The interactive effects underscore the importance of considering RFM and glucose tolerance status jointly in CVD and death risk assessment.

Thirdly, with the combination of mediating and interactive effects, we conducted the joint association and identified the subclassification that displayed the highest HR among the 12 subclassifications. When comparing persons with NGT and RFM in the first quartile, the greatest HRs were observed in individuals with diabetes and RFM in the fourth quartile among 12 distinct groups for both fatal and nonfatal CVD events. Asgari et al. reported that individuals with diabetes and obesity exhibited the highest HR compared with other diabesity phenotypes for risk of CVD, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality in an Iran cohort study [29]. Whereas, we observed that those who have diabetes and a high RFM in the third quartile for all-cause mortality had the greatest HR, which was slightly higher than those with diabetes and a high RFM lying in the fourth quartile based on NGT&RFM Q1 as reference. The difference may be due to the following reasons. First, there may be a potential nonlinearity in the joint effect of RFM and prediabetes and diabetes for all-cause mortality. Second, Asgari's research classified obesity as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above, while we categorized participants based on quartiles of RFM. Third, the ethnic differences may also account for the disparity [30]. Join analysis could significantly influence how clinicians assess high-risk individuals, lead to more personalized and effective strategies, and underscore the importance of comprehensive prevention strategies that combine obesity with hyperglycemia.

By subgroup analysis, we observed that RFM and fatal CVD events and all-cause mortality showed more prominent relationships in the subgroup of females in all and those with diabetes. Differently, Zwartkruis et al., found that RFM was more greatly associated with CVD in males [5]. Most of the women included in our study were postmenopausal with a median age of 60.12 years old, while the median age was 45 years old in Zwartkruis’s study. With the absence of the protective effect of estrogen on CVD and death [38], females therefore exhibit a higher risk than men. Moreover, those with prediabetes displayed stronger HR in the subgroup of age < 60. This may be due to that in the subgroup of ≥ 60, the independent risk of RFM may be attenuated by other stronger risk factors. Furthermore, RCS suggested dose-dependent associations between RFM and outcomes and identified the relative cutoffs for clinical practice. Wang et al. also found a U-shaped RCS in males and an approximately J-shaped RCS in females [4]. The RCS were mostly approximately J-shaped in our cohort, which may be because most subjects were females. In addition, by comparison with other obesity indices including BMI, WC, and WHR, RFM exhibited the highest predictive performance. Shen et al. also found the RFM had the highest AUC compared with other indices in a cross-sectional study consisting of 11,532 adult Chinses participants [8]. We extended this with cohort epidemiological evidence for Asians.

The strengths of this study are as follows. First, the present study is the first to investigate the associations between RFM and CVD events and all-cause mortality in NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, respectively, and investigate the modified effect including mediating and interactive effects of glucose tolerance statuses on these relationships, which provides practical implications for clinical practice of risk stratification and comprehensive prevention. We also conducted the joint analysis and identified the subclassification that exhibited the highest HR among 12 subclassifications, which might have a substantial impact on how medical practitioners evaluate high-risk cases and could result in the development of more personalized, effective prevention strategies. Second, we filled the knowledge gap of the association between RFM and the risk of CVD events and all-cause mortality with the cohort epidemiological evidence for the Asian population, which has been rarely reported. Third, the present study discovered the dose-dependent association between RFM and outcomes and provided potential RFM cutoffs by RCS analyses, which lack evidence in population-based cohorts for Asians. Fourth, we compared the predictive performance of RFM with other standardized obesity indices including BMI, WC, and WHR, and extended the comparisons to different glucose tolerance statuses. Fifth, the present study was performed in a large, longitudinal, contemporary, population-based cohort with a follow-up of up to 5 years.

This study has several limitations. First, while RFM accurately predicts fat mass, it cannot distinguish between visceral and subcutaneous fat. Imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging can provide more precise fat compartment measurements but are not feasible for large cohorts. However, RFM is easy to calculate, gender-specific, non-invasive, cost-effective, and more accurate in estimating total body fat [5, 7]. Second, the relatively short follow-up duration reduced the number of clinical outcome events and affected the statistical power, but our findings were nonetheless meaningful. Hence, further investigations need to include more extensive sample sizes and extended follow-up durations. Third, although we adjusted for numerous potential confounders, other unknown or unmeasured variables, including diet, etc., may have influenced these associations. Fourth, it is important to note that this study only focused on people of Chinese ethnicity who were 40 years old or older. Therefore, further research is needed in other countries and across different age groups to confirm these findings. Fifth, the baseline analysis included 32.6% with NGT, 54.8% with prediabetes, and 12.6% with diabetes. Wang et al. [39] reported a prediabetes prevalence of 38.1% and a diabetes prevalence of 12.4% in a nationally representative Chinese sample of 173,642 adults. While our study's diabetes prevalence aligns with Wang's, the prediabetes prevalence was higher, likely due to the older average age in our cohort (60.1 vs. 51.3 years) [39]. Although our sample may not fully represent the general population, the study remains valuable as we analyzed each group (NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes) separately, making the results relevant to each group.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study shed light on that the elevated baseline RFM was associated with increased risk of fatal, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality in NGT, prediabetes, and diabetes, and these associations were modified by glucose tolerance statuses. Mediation analysis found that glucose tolerance status partially mediated the associations between RFM and risk for outcomes and interaction analysis revealed that RFM and prediabetes and diabetes could induce outcomes in a synergistic method. The joint analysis identified the subclassification that exhibited the highest HR among 12 subclassifications, which underscores the importance of a comprehensive approach to practical prevention, could significantly influence how clinicians assess high-risk and could lead to more personalized, effective prevention strategies. Finally, RFM outperformed all other obesity indices (BMI, WC, WHR) in predictive performance.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Zhangping Li in the clinical laboratory of the Division of Endocrinology for their contributions to collecting and handling samples.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations

- 4C

The China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort

- AP

Proportion attributable to interaction

- AUC

Areas under curves

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- CVD

Cardiovascular diseases

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

Hazard ratio; IQI: interquartile interval

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NGT

Normal glucose status

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- PG2h

2-H plasma glucose

- RCS

Restricted cubic splines

- RERI

Relative excess risk due to interaction

- RFM

Relative fat mass

- ROC

Receiver operator characteristic

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SI

Synergy index

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Total triglycerides

- WC

Waist circumference

- WHR

Waist-hip ratio

Author contributions

XY and PL designed the study. YG, DL, XM, RK, and PL collected the data. PL performed the statistical analysis. XY and PL wrote the paper. All reviewed the paper and provided suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions of the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470907 and 82270880).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Committee on Human Research at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved the study protocol (Numbers: 14/2004 and TJ-IRB20231125), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in compliance with the guidelines for cohort studies established by the STROBE.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Omachi DO, Aryee ANA, Onuh JO. Functional lipids and cardiovascular disease reduction: a concise review. Nutrients. 2024;16(15):2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suthahar N, Meems LMG, Withaar C, Gorter TM, Kieneker LM, Gansevoort RT, et al. Relative fat mass, a new index of adiposity, is strongly associated with incident heart failure: data from PREVEND. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suthahar N, Wang K, Zwartkruis VW, Bakker SJL, Inzucchi SE, Meems LMG, et al. Associations of relative fat mass, a new index of adiposity, with type-2 diabetes in the general population. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;109:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Guan J, Huang L, Li X, Huang B, Feng J, et al. Sex differences in the associations between relative fat mass and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;34(3):738–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwartkruis VW, Suthahar N, Idema DL, Mahmoud B, van Deutekom C, Rutten FH, et al. Relative fat mass and prediction of incident atrial fibrillation, heart failure and coronary artery disease in the general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47(12):1256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacciatore S, Calvani R, Marzetti E, Coelho-Junior HJ, Picca A, Fratta AE, et al. Predictive values of relative fat mass and body mass index on cardiovascular health in community-dwelling older adults: results from the Longevity Check-up (Lookup) 7. Maturitas. 2024;185: 108011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolcott OO, Bergman RN. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage horizontal line a cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen W, Cai L, Wang B, Wang Y, Wang N, Lu Y. Associations of relative fat mass, a novel adiposity indicator, with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease: data from SPECT-China. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:2377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paek JK, Kim J, Kim K, Lee SY. Usefulness of relative fat mass in estimating body adiposity in Korean adult population. Endocr J. 2019;66(8):723–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu P, Huang T, Hu S, Yu X. Predictive value of relative fat mass algorithm for incident hypertension: a 6-year prospective study in Chinese population. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10): e038420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(1):S31–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Xu Y, Wan Q, Shen F, Xu M, Zhao Z, et al. Individual and combined associations of modifiable lifestyle and metabolic health status with new-onset diabetes and major cardiovascular events: the China cardiometabolic disease and cancer cohort (4C) study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou H, Xu Y, Meng X, Li D, Chen X, Du T, et al. Circulating ANGPTL8 levels and risk of kidney function decline: results from the 4C Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, Wang S, Li M, Gao Z, Xu Y, Zhao X, et al. Association of serum bile acids profile and pathway dysregulation with the risk of developing diabetes among normoglycemic chinese adults: findings from the 4C Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong L, Wang C, Ning G, Wang W, Chen G, Wan Q, et al. High concentrations of triglycerides are associated with diabetic kidney disease in new-onset type 2 diabetes in China: findings from the China cardiometabolic disease and cancer cohort (4C) Study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(11):2551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou H, Xu Y, Chen X, Yin P, Li D, Li W, et al. Predictive values of ANGPTL8 on risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients: results from the REACTION Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J, Bi Y, Wang T, Wang W, Mu Y, Zhao J, et al. The relationship between insulin-sensitive obesity and cardiovascular diseases in a Chinese population: results of the REACTION study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172(2):388–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bi Y, Lu J, Wang W, Mu Y, Zhao J, Liu C, et al. Cohort profile: risk evaluation of cancers in Chinese diabetic individuals: a longitudinal (REACTION) study. J Diabetes. 2014;6(2):147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ning G, Reaction Study G. Risk evaluation of cancers in chinese diabetic individuals: a longitudinal (REACTION) study. J Diabetes. 2012;4(2):172–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ning G, Bloomgarden Z. Diabetes and cancer: findings from the REACTION study: REACTION. J Diabetes. 2015;7(2):143–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flora GD, Nayak MK. A brief review of cardiovascular diseases, associated risk factors and current treatment regimes. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(38):4063–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huo RR, Liao Q, Zhai L, You XM, Zuo YL. Interacting and joint effects of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) and body mass index on stroke risk and the mediating role of TyG in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kartiosuo N, Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Viikari JSA, Sinaiko AR, Venn AJ, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and adulthood and cardiovascular disease in middle age. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6): e2418148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung SJ. Introduction to mediation analysis and examples of its application to real-world data. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021;54(3):166–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rijnhart JJM, Lamp SJ, Valente MJ, MacKinnon DP, Twisk JWR, Heymans MW. Mediation analysis methods used in observational research: a scoping review and recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suthahar N, Zwartkruis V, Geelhoed B, Withaar C, Meems LMG, Bakker SJL, et al. Associations of relative fat mass and BMI with all-cause mortality: confounding effect of muscle mass. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2024;32(3):603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolcott OO, Bergman RN. Defining cutoffs to diagnose obesity using the relative fat mass (RFM): Association with mortality in NHANES 1999–2014. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020;44(6):1301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreasson A, Carlsson AC, Onnerhag K, Hagstrom H. Predictive capacity for mortality and severe liver disease of the relative fat mass algorithm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2619–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asgari S, Molavizadeh D, Soltani K, Khalili D, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. The impact of obesity on different glucose tolerance status with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality events over 15 years of follow-up: a pooled cohort analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams R, Periasamy M. Genetic and environmental factors contributing to visceral adiposity in Asian populations. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2020;35(4):681–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu S, Wang Q, Lu H, Kuang M, Zhang M, Sheng G, et al. Lipids as potential mediators linking body mass index to diabetes: evidence from a mediation analysis based on the NAGALA cohort. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024;24(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein S, Gastaldelli A, Yki-Jarvinen H, Scherer PE. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022;34(1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinning C, Makarova N, Volzke H, Schnabel RB, Ojeda F, Dorr M, et al. Association of glycated hemoglobin A(1c) levels with cardiovascular outcomes in the general population: results from the BiomarCaRE (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe) consortium. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y. Postprandial plasma glucose measured from blood taken between 4 and 7.9 h Is positively associated with mortality from hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024. 10.3390/jcdd11020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Zhang W, Dai J, Deng Q, Yan Y, Liu Q. Associations of fasting plasma glucose with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in older Chinese diabetes patients: a population-based cohort study. J Diabetes Investig. 2024. 10.1111/jdi.14196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen Q, He T, Li T, Szeto IM, Mao S, Zhong W, et al. Synergistic effects of overweight/obesity and high hemoglobin A1c status on elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1156404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu F, Zhang S, Ye D, Chen Z, Ding J, Zhang T, et al. The interaction of T2DM and BMI with NASH in recipients of liver transplants: an SRTR database analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;17(2):215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiang D, Liu Y, Zhou S, Zhou E, Wang Y. Protective effects of estrogen on cardiovascular disease mediated by oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5523516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Peng W, Zhao Z, Zhang M, Shi Z, Song Z, et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 2013–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.