Abstract

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a clinical condition that arises acutely in the pancreas through various inflammatory pathways due to multiple causes. Turkish Society of Gastroenterology Pancreas Working Group developed comprehensive guidance statements regarding the management of AP that include its epidemiology, etiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, disease severity, treatment, prognosis, local and systemic complications. The statements were developed through literature review, deliberation, and consensus opinion. These statements were ultimately used to develop a conceptual framework for the multidisciplinary management of AP.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, diagnosis, severity assessment, local pancreatic complications, treatment

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a clinical condition that arises acutely in the pancreas through various inflammatory pathways due to multiple causes. Acute pancreatitis remains one of the most common gastrointestinal diseases requiring hospitalization worldwide. Despite advances in imaging techniques, treatment, and interventional procedures, it still has significant morbidity and mortality. Patients frequently present with pain in the epigastric region or upper abdominal quadrant that radiates to the back, along with nausea and vomiting. Approximately 80% of AP cases are mild and generally self-limiting. Severe forms are less common but have mortality rates approaching 30%. In the management of AP, both symptom control and the diagnosis and treatment of complications that arise during the course of the disease are of great importance. Therefore, the approach to patient management must be individualized. Currently, there are still controversial points regarding the etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of the disease.

In this guide, we aim to address questions related to the definition, epidemiology, etiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, disease severity, treatment, prognosis, local and systemic complications of AP, and the management of these complications in light of current literature.

The Stakeholders (Participants)

The Turkish Society of Gastroenterology—Pancreas Working Group has formed a sub-working group consisting of 38 experts to prepare the AP consensus report. The group held an initial informational meeting on January 5th, 2022 and began consensus report development meetings on February 27th, 2022. Target users of the consensus report are all clinicians involved in the follow-up and treatment of patients with AP.

Methodology

As a first step in the preparation process of the AP consensus report, a coordination team specialized in AP was formed from the pancreas working group. This group’s systematic literature review provided evidence to address pre-determined topics (definition, etiology, diagnosis, disease severity, treatment, prognosis, local, and systemic complications). The group’s experience and views were integrated using an evidence-based methodology. The Delphi method was employed to ask the working group members to define research questions relevant to these topics. These questions were then consolidated and discussed face-to-face during a 1-day meeting, where they were finalized. During the same meeting, questions were tailored to fit a systematic literature search. As a result, a total of 49 questions were identified, comprising 10 main questions with their respective sub-questions. For each question, keywords for literature searches were specified. Decisions were made regarding the characteristics of articles to be included in the analysis, the evaluation criteria to be used during the analysis, and the method of analysis. This structured approach ensured the comprehensive and systematic gathering and evaluation of relevant evidence.

The members of the working group responsible for the systematic literature review received a half-day training on the review’s methodology, the selection of articles, the extraction of data from the articles, and the statistical methods to be used for combining and analyzing the obtained data.

Subsequently, each working group member responsible for the literature review conducted a systematic literature review related to their specific questions as described above. A literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and Embase for relevant articles. Searches focused primarily on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses. In addition, for topics not covered in these studies, retrospective analyses, case series, and prospective studies covering these topics were included. Inclusion criteria were determined as specific studies with a sample size of at least 20 patients, published in English and available in full text. Presented the results to the group during the second meeting. In the 2-day second meeting, the selected articles and the analysis of the data obtained from these articles were evaluated to answer each question. Draft recommendations were created for questions with sufficient data. For questions where the data were deemed insufficient by the working group, the missing analyses and additional analyses deemed necessary by the experts were identified.

The incomplete analyses were completed between the second and third meetings. During the 2-day third meeting, these analyses were presented to the working group by each member. Combining the evidence from the literature and the opinions of the working group, recommendations were formulated for each research question. For these recommendations, both the level of evidence and the recommendation grade were reported according to the Oxford criteria (Supplementary Table 1). Recommendations were prepared to be voted on by a larger group of gastroenterology experts related to the subject.

Supplementary Table 1.

Level of Evidence Classification

| Level of Evidence | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1a | Systematic reviews (meta-analyses) containing at least some trials of level 1b evidence, in which the results of separate, independently controlled trials are consistent |

| 1b | Randomized controlled trial of good quality and of adequate sample size (power calculations) |

| 2a | Randomized trials of reasonable quality and/or inadequate sample size |

| 2b | Nonrandomized trials, comparative research (parallel cohort) |

| 2c | Nonrandomized trials, comparative research (historical cohort, literature controls) |

| 3 | Nonrandomized, non-comparative trials, descriptive research |

| 4 | Expert opinions, including the opinion of work group members |

The final meeting was attended by 122 gastroenterologists from various provinces of Türkiye, including those working in university hospitals, government hospitals, and the private sector who are interested in AP. In this meeting, the results of the systematic literature review conducted for each question were presented along with the recommendations formed based on these results. Each recommendation was discussed by the group, and minor modifications were made if deemed necessary before being voted on. Recommendations that received an approval rate of 70% or higher from the group were accepted. Those that did not reach this approval rate were re-discussed, modified further, and voted on again. Ultimately, all recommendations were approved and accepted by the group with an approval rate of at least 70%. It was defined that “strong agreement” would require at least 80% of votes to be either “definitely yes” or “probably yes.”

Summary of the recommendations, level of evidence, and strength of recommendation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Recommendations on the Management of Acute Pancreatitis

| Diagnosis |

| Transabdominal ultrasonography (TAUS) can be used as a primary imaging method due to its ability to provide valuable information not only for diagnosing AP but also for etiological assessment, coupled with its widespread use. If the diagnosis of AP remains uncertain after TAUS, evaluation with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is recommended (Level of Evidence: 2B, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.4%)). |

| Initial Asessment and Risk Stratification |

| The severity of AP is categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the presence of local and systemic complications, as well as the state of necrosis and infected necrosis. The revised Atlanta classification is the most commonly used classification for this purpose (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (96.7%)). |

| Elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels during the course of AP or at 48 hours are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 150 mg/L (15 mg/dL) at 48 hours can be used as an indicator of poor prognosis in AP (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (91.7%)). |

| Given its simplicity in calculation and comparability to the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) score, the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score is the recommended scoring system for routine clinical practice (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (91.7%)). |

| Initial Management |

| Fluid Resuscitation |

| The fluid used in treatment should be isotonic crystalloid (isotonic NaCl or Ringer’s lactate (RL)). If there is no contraindication specific to the patient (e.g., hypercalcemia), RL can be preferred (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.7%)). |

| There is insufficient evidence regarding the use of hydroxyethyl starch (HES) in AP treatment. Its use is not recommended in AP treatment except for abdominal compartment syndrome (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.7%)). |

| The rate of fluid resuscitation should be tailored according to the patient’s clinical assessment at presentation and follow-up data (targeted) (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.7%)). |

| Aggressive fluid therapy in AP, particularly in moderate to severe and severe AP patients, is not recommended as it increases the risk of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), organ failure, the need for intensive care and ventilation, and the development of abdominal compartment syndrome (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.7%)). |

| Pain Control |

| In patients with mild AP, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Indomethacin, metamizole, dexketoprofen, diclofenac) have similar efficacy to opioids in pain palliation during the first 24 hours and can be used as alternatives to opioids. They should not be used in patients with renal failure (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.6%)). |

| Nutrition in AP |

| Unless there is an obstruction or contraindication to oral feeding (e.g., ileus, abdominal compartment syndrome), oral intake should not be discontinued (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (78.4%)). |

| If oral feeding cannot be initiated within the first 72 hours, nutritional support should be provided. For patients who cannot tolerate oral feeding, enteral nutrition (EN) should be prioritized. Feeding should commence using a nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal (NJ) tube (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (79%)). |

| For patients who cannot tolerate EN, where NG/NJ tube placement is not possible, or where target protein and calorie needs cannot be met by EN alone, parenteral nutrition (PN) should be administered (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.9%)). |

| Glutamine should be added to the nutritional solution for patients requiring nutritional support (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (84.9%)). |

| The Role of Antibiotics in AP |

| The use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended in AP, including severe pancreatitis and the presence of necrosis. However, antibiotics are recommended in cases of infected necrosis and extrapancreatic infections (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.1%)). |

| In AP, carbapenems, quinolones, metronidazole, and cephalosporins can be used. In the presence of infected necrosis, carbapenem antibiotics should be preferred (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.4%)). |

| ERCP in AP |

| In acute biliary pancreatitis, if there are signs of a stone impacted in the papilla or cholangitis, ERCP is recommended at the earliest possible stage. If these conditions are not present but there are signs of cholestasis, imaging of the common bile duct (endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)) is recommended (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (100%)). |

| Indications for Referral to a Tertiary Center and Admission to the Intensive Care Unit |

| Patients with a BISAP score of 3 or higher at diagnosis, and those experiencing moderate or severe attacks according to the revised Atlanta criteria during follow-up should be promptly referred to a tertiary center. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.2%)). |

| Patients with confirmed or strongly suspected biliary etiology (those considered for ERCP and/or cholecystectomy) should be referred to specialized centers. (Level of Evidence: 2B, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.2%)). |

| Patients with persistent organ dysfunction should be monitored in an intensive care unit. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.7%)). |

| Management of AP Complications |

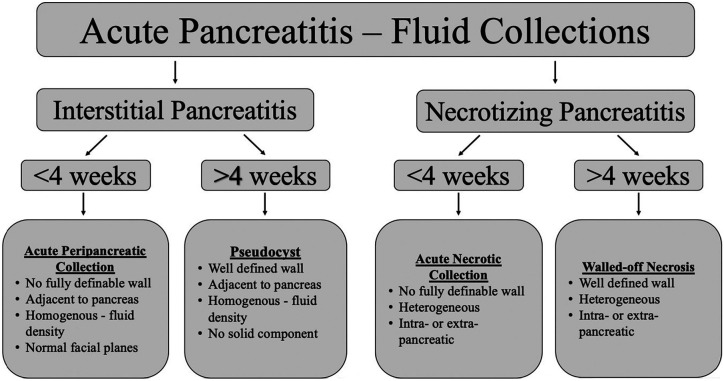

| Peripancreatic Fluid Collections |

| Pancreatic pseudocysts (PP) should be managed conservatively unless symptomatic. Indications for drainage include cyst infection, persistent intra-abdominal symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety), gastric outlet obstruction, and biliary obstruction with accompanying jaundice. (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (96.8%)). |

| Endoscopic drainage should be the preferred approach for draining PPs adjacent to the stomach or duodenum due to its less invasive nature and high clinical success rates. Surgical drainage may be considered for patients in whom endoscopic intervention fails and/or is anatomically unsuitable (Level of Evidence:1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (91.9%)). |

| Percutaneous drainage can be preferred for cysts inaccessible via endoscopy or for patients with comorbidities precluding endoscopy or surgery (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (91.9%)). |

| In patients with luminal compression, both conventional and EUS-guided drainage have similar technical success and complication rates. In cases of PP without luminal compression, in patients with coagulopathy, in the presence of cyst-adjacent vascular structures, and when complications arise during conventional procedures, EUS-guided drainage is specifically recommended (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (93.6%)). |

| Asymptomatic pancreatic and/or extrapancreatic necrosis do not require invasive intervention regardless of their size or location (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.3%)). |

| After the diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis, patients should be closely monitored under appropriate antibiotic and nutritional support, if necessary, in intensive care settings. Waiting at least 4 weeks before invasive interventions is a more suitable approach in terms of potential complications. However, if the patient’s clinical condition deteriorates minimal invasive intervention should be considered irrespective of time. (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (91.4%)). |

| Endoscopic drainage is the preferred treatment for walled-off necrosis (WONs). In patients with collections that are not suitable for endoscopic drainage, minimally invasive surgery or percutaneous drainage may be the preferred approach (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (100%)). |

| Patients with WON that extends into the paracolic gutters or pelvis may require percutaneous drainage in addition to the endoscopic procedure (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (100%)). |

| Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome (DPDS) |

| A step-up approach may be recommended for DPDS. In endoscopic treatment, long-term transmural drainage (TMD) with plastic stents is sufficient for most patients (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (88.5%)). |

| Transmural stents should be maintained for a long period. Before removal, imaging techniques (preferably secretin-enhanced MRCP) should confirm the absence of a pancreatic duct “feeding” the cyst (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (88.5%)). |

| Venous Thrombosis |

| If isolated splenic vein thrombosis is present, the thrombus extends to the mesenteric vein, or there is a portal vein thrombosis without collateral formation at the time of detection and anticoagulant use is not contraindicated, anticoagulant therapy should be administered with careful consideration of bleeding risk, particularly in patients with pseudocysts (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (97%)). |

| In patients starting anticoagulation therapy without an underlying thrombophilic disorder, the treatment duration should be 3-6 months (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (96%)). |

| In patients with severe AP where no contraindications exist, short-term (7-14 days) prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) therapy has beneficial effects on hospital stay, organ failure, and mortality (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.1%)). |

| Management of Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis (RAP) |

| Identification and treatment of the underlying etiological factor to reduce the number of attacks in RAP is recommended. However, there is insufficient evidence that specific treatments can reduce or prevent the number of RAP attacks (Level of Evidence: 2A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.1%)). |

| In biliary RAP patients who cannot undergo cholecystectomy due to high surgical risk, or in post-cholecystectomy patients with biliary RAP, biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy (BES) may prevent new attacks (Level of Evidence: 2A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (98.6%)). |

| In RAP patients associated with pancreas divisum without chronic pancreatitis findings, minor papilla endoscopic sphincterotomy may prevent the development of new attacks (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (100%)). |

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy is recommended in type I sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) and particularly in type II SOD with enzyme elevation (Level of Evidence: 2A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (98.9%)). |

| In cases of idiopathic RAP, although sufficient evidence is lacking, BES may be considered after investigating microlithiasis or other potential etiologies on a per-patient basis. Pancreatic endoscopic sphincterotomy is not routinely recommended (Level of Evidence: 2A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (97.9%)). |

| Management of Long-term Complications of AP |

| Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) |

| Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) should be administered to patients with AP-induced EPI. The initial dose is 40 000-50 000 units at main meals and 25 000 units at snacks. Based on treatment response, doses can be increased to a maximum of 80 000 units at main meals and half of this amount at snacks (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of Recommendation: Strong Consensus (92.3%)). |

| A dietary plan with frequent, small-volume meals is recommended. At least one meal should include a normal amount of fat (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of Recommendation: Strong Consensus (91.7%)). |

| Periodic screenings for nutritional deficiencies (fat-soluble vitamins, magnesium, zinc, vitamin B12) should be conducted, and supplementation should be provided if deficiencies are detected (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of Recommendation: Strong Consensus (94.3%)). |

| Pancreatic Ascites |

| Endoscopic treatment methods should be preferred in suitable cases. In cases of partial pancreatic duct disruption, transpapillary endoscopic drainage is an appropriate method (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of Recommendation: Strong Consensus (95.4%)). |

| Percutaneous drainage can be applied in the event of increased pain, clinical deterioration, new-onset organ failure, or abdominal compartment syndrome. Surgery should be considered in cases where endoscopic treatments are inappropriate or unsuccessful. (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of Recommendation: Strong Consensus (88%)). |

| Pseudoaneurysm |

| Pseudoaneurysm should be suspected in cases of abdominal pain, a drop in hemoglobin (gastrointestinal and intra-abdominal bleeding), and sudden growth of the cystic lesion. Endovascular embolization (coil) is the first treatment option. If this fails, surgical treatment may be applied (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (98.7%)). |

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM) |

| Metformin is effective in the treatment of DM after AP. Insulin therapy may be needed earlier compared to type 2 DM (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of Recommendation: Strong consensus (89.9%)). |

| The Role of Surgery in AP |

| Cholecystectomy in AP |

| In mild biliary AP, the patient should ideally be recommended cholecystectomy after the pancreatitis has subsided, preferably during the hospital stay and within 4 weeks if possible (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of Recommendation: Strong consensus (96.1%)). |

| Delaying cholecystectomy following moderate and severe biliary AP reduces morbidity. In patients who have survived an episode of moderate to severe acute biliary pancreatitis and present with pancreatic fluid collections, cholecystectomy should be postponed for 6-8 weeks (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.2%)). |

| Following an episode of AP with no identifiable cause, cholecystectomy should be considered in patients suitable for surgery to reduce the risk of recurrent pancreatitis attacks (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (80.1%)). |

| Indications for Surgical Intervention |

| Fistulization of the peripancreatic collection to the colon, intestinal ischemia, abdominal compartment syndrome where conservative and noninvasive treatments have failed, perforation, gastric outlet obstruction, intestinal obstruction, acute necrotizing cholecystitis, and bleeding where the endovascular approach has failed (Level of evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (96.3%)). |

| In patients with infected necrosis, surgery should be delayed for at least 4 weeks to allow the development of a fibrous wall around the necrosis, except in cases requiring emergency surgical intervention (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (100%)). |

| In acute necrotizing pancreatitis, open surgery should only be considered as a treatment method when other treatment options have failed or in cases requiring emergency surgery. When surgical treatment is necessary, minimally invasive surgical options should be prioritized. A step-up approach should be preferred (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (98.7%)). |

AP, acute pancreatitis; APACHE II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; BES, biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy; BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C-reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; DPDS, disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome; EN, enteral nutrition; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EPI, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency; EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography; HES, hydroxyethyl starch; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PERT, Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy; PN, parenteral nutrition; PP, pancreatic pseudocysts; RAP, management of recurrent acute pancreatitis; RL, Ringer’s lactate; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SOD, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction; TAUS, transabdominal ultrasonography; TMD, transmural drainage; WONs, walled-off necrosis.

Questions and Recommendations

1. Introduction, Definition and Epidemiology

Question 1.1: What is the definition of AP?

Recommendation 1.1:

Acute pancreatitis is an acute inflammatory disease of the pancreas caused by various factors. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89%)).

Question 1.2: What is the epidemiology of AP?

Recommendation 1.2:

The incidence of AP has been steadily increasing over the past 50 years. The annual incidence ranges from 5 to 100 per 100,000. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (97.5%)).

Comment : While the incidence of AP is high in Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and North America, the incidence in parts of Eastern Africa and South America is comparatively lower. While the incidence is rising in North America and Europe, it remains stable in Asia.1,2 When examining the distribution of etiology by region, gallstones are the predominant etiology in Southern Europe (Greece, Türkiye, Italy, Croatia), whereas alcohol is more prominent in Eastern Europe (Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, Finland, Hungary).3

Question 1.3: What are the risk factors for the development of AP?

Recommendation 1.3:

Advanced age, male sex, smoking, obesity, elevated triglycerides (TG), pregnancy, and being of black race. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.2%)).

Comment: The incidence of AP increases with age. Particularly in the geriatric population, both the incidence and mortality rates are higher compared to younger age groups.3,4 Although AP is observed equally in both sexes, some studies report that its incidence is 1.5-2 times higher in men than in women.5 In terms of etiological distribution by gender, gallstones are more frequently seen in women, whereas alcohol and other etiological factors are more common in men.6 The prevalence of AP is 2-3 times higher in individuals of Black race and in Aboriginal populations compared to other races.7 Smoking also increases the risk of AP. Obesity contributes to an increased risk of gallstone-associated pancreatitis and severe pancreatitis. Elevated TG and an increase in body mass index (BMI) also elevate the risk of recurrent AP.8-10 2. Etiology

Question 2: What is the etiology of AP?

Recommendation 2:

The most common causes of AP are gallstones (40-70%) and alcohol (25-35%). The prevalence of these etiological factors can vary based on geographic, demographic, and genetic factors. Other causes include hypertriglyceridemia (HTG), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), medications, infectious agents, hypercalcemia, genetic variants, toxins, smoking, trauma, tumors, certain surgical procedures, and anatomical and physiological disorders of the pancreas. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.1%)).

Comment : The etiology of AP encompasses a broad spectrum. According to the results of a recent prospective cohort study that included 2244 patients across 17 centers, biliary AP ranks first in the etiology of AP in Türkiye (67.1%). This is followed by idiopathic (12%), hypertriglyceridemia (6%), and alcohol induced AP (4.2%).11 A meta-analysis of 46 studies from 36 different countries reported gallstones and alcohol as the primary etiological factors in AP.12 According to this study, biliary AP was reported at 42% (39-44), alcohol-induced AP at 21% (17-25), and idiopathic AP at 18% (15-22). However, the prevalence of etiological factors can vary based on geographical, demographic, and genetic factors.13 For example, while both gallstones and alcohol are the main etiological factors in Northern European countries, gallstones are the most common etiological factor in Southern European countries.

Gallstone pancreatitis is more common in women, whereas alcoholic pancreatitis is more frequently observed in middle-aged men.14 Anatomical variations and genetic predispositions can also contribute to the development of biliary pancreatitis.15,16

Alcohol is one of the most common causes of AP, and it has been found that the risk of AP increases with higher alcohol consumption.17,18 However, the incidence of AP among heavy alcohol users is reported to be only around 5%, suggesting that other accompanying factors (such as smoking, genetic, and anatomical factors) also play a role in the development of AP.19,20

Hypertriglyceridemia is one of the leading causes of AP. Serum TG levels, particularly those exceeding 1000 mg/dL, should be considered a potential cause of AP.

In addition, ERCP (16-97%), tumors (2-67%), drugs (8-41%), trauma (1-69%), hypercalcemia (2-16%), infectious agents (2-35%), and more rarely, genetic variants, toxins, smoking, anatomical and physiological disorders of the pancreas, and surgical interventions are included in the etiology of AP.21,22 A recent systematic review evaluating 128 publications reported that viral hepatitis (A, B, C, D and E) is the most common among the viruses causing AP with 34.4%, followed by coxsackie and echoviruses (14.8%), hemorrhagic fever viruses (12.4%), cytomegalovirus (12%), varicella-zoster virus (10.5%).23 Additionally, AP development associated with the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has also been reported.24,25 Studies have shown that severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV-2 infects human endocrine and exocrine pancreatic cells, suggesting a direct role of SARS-CoV-2 in pancreatic disorders.26 Besides viruses, bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mycoplasmas, leptospirosis), parasites (Ascaris lumbricoides, Fasciola hepatica, and echinococcal cysts), and fungal infections (aspergillosis) are also etiological factors causing AP.27 An AP course associated with infectious agents has reported a mortality rate of 20%, which is higher than those reported for other etiologies. This situation is mostly associated with immunosuppression.23

Smoking also increases the risk of AP. The risk is higher in active smokers (Hazard Ratio (HR), 1.75; 95% Confidence interval (CI), 1.26-2.44); however, the risk persists in former smokers (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.18-2.27).28 Smoking additionally elevates the risk of alcohol-induced, idiopathic, and drug-induced pancreatitis, but no effect on biliary pancreatitis has been observed. Each additional 10 cigarettes smoked per day increases the risk of AP by 40%.29,30

Genetic factors play both direct and indirect roles in the etiology of AP. In individuals with early onset of AP and a family history following an autosomal dominant pattern, mutations in the serine protease 1 (PRSS1) gene should be investigated. Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) binds to prematurely activated intracellular trypsin, playing a protective role against pancreatitis. A meta-analysis showed that the p.N34S variant in this gene is more prevalent in patients who have experienced AP (Odds Ratio (OR) = 3.16, P < .001).31,32 Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene actually facilitate AP and are also a cause of chronic pancreatitis (CP). Some metabolic storage diseases, such as Gaucher disease, can also be counted among the genetic causes of AP.33

It is known that endoscopic or surgical interventions such as double balloon endoscopic examination, ERCP and intragastric balloon application can also lead to the development of AP.34,35 The incidence of AP following ERCP is reported to be approximately 3.5%. When ERCP is performed to treat sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, the risk of causing AP is higher. Other risk factors for the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis include younger age, female gender, the number of attempts to cannulate the papilla, and inadequate drainage of the pancreatic duct following the injection of contrast material.

Abdominal, cardiac, spinal surgeries, and vascular embolectomies can also lead to AP. Particularly during major vascular interventions, ischemia of the pancreas, emboli to vascular structures supplying the pancreas, direct injuries caused by retractors or incisions, and crush syndrome can cause AP.36-38

The most common drugs causing AP are azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, valproic acid, thiazides, tamoxifen, and exogenous estrogens. Pancreas divisum (PD) is the most frequently encountered anatomical variation of the pancreatic duct and is more commonly associated with recurrent AP.39-41 An arteriovenous shunt in the pancreas can lead to recurrent AP by causing ischemia or bleeding.42 Duodenal duplication cysts and juxtapapillary diverticula are also causes of AP.43,44 Metabolic conditions such as hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism, as well as parathyroid carcinoma, and benign or malignant mass lesions obstructing the main pancreatic duct, can cause AP.45,46 Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), hemolysis, arteriovenous malformations, venoms, and toxins are other causes of AP. Systemic lupus erythematosus–related pancreatitis can result from vasculitis, microthrombosis, anti-pancreatic autoantibodies, drug side effects, intimal thickening, and concurrent viral infections.47 In pregnancy, AP can also occur due to causes such as gallstones and HTG.48

3. Diagnostic Criteria (Laboratory, Clinical and Imaging)

Question 3.1: How is the diagnosis of AP made?

Recommendation 3.1:

The diagnosis is based on the presence of typical abdominal pain, laboratory findings including an elevation of amylase and/or lipase levels more than 3 times the normal, and supportive findings from imaging modalities such as transabdominal ultrasonography (TAUS), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with 2 out of these 3 criteria are diagnosed with AP. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong Consensus (99.2%)).

Comment : Abdominal pain is the primary symptom in AP, present in over 95% of patients.49,50 The typical abdominal pain associated with AP begins in the epigastric region or upper quadrant of the abdomen, radiating to the back. This pain is generally dull and severe, partially alleviated in the knee-chest (fetal) position, and intensified by eating or drinking. This type of pain occurs in 40-70% of patients.2 The second most frequent symptom is nausea and/or vomiting, which occurs in 90% of patients.51 Gastroparesis and localized or generalized ileus, resulting from peripancreatic inflammation, are responsible for the nausea and vomiting. Additionally, symptoms such as fever, tachycardia, distension, jaundice, and dyspnea may also be present to varying degrees.

The threshold value for amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of AP is 3 times the normal level, with sensitivities and specificities of 72% and 93% for amylase and 79% and 89% for lipase, respectively.52,53 A review comparing amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of AP indicated that the specificities of these tests are similar (around 90%), but lipase has a higher sensitivity (amylase sensitivity ranges from 45% to 85%, while lipase sensitivity ranges from 55% to 100%).54 In cases of AP due to hyperlipidemia or in acute attacks of CP, amylase and lipase levels may not be elevated.55 Studies have shown that biomarkers such as phospholipase, elastase, and carboxypeptidase have lower sensitivities and specificities compared to amylase and lipase in diagnosing AP.56 Additionally, these biomarkers are not widely used in clinical practice due to disadvantages in terms of time, cost, and application. However, studies on the urinary trypsinogen-2 test have shown that its sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing AP exceed 82% and 90%, respectively, with levels rising within a few hours after the onset of AP.57

Question 3.2: What is the role of imaging in the diagnosis of AP?

Recommendation 3.2:

Imaging methods are 1 of the 3 diagnostic criteria and are crucial in diagnosing AP. They play a significant role when the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of AP remains uncertain or when other potential conditions (such as organ perforation, mesenteric ischemia, ileus, etc.) are being considered. Transabdominal ultrasonography can be used as a primary imaging method due to its ability to provide valuable information not only for diagnosing AP but also for etiological assessment (differentiating between biliary and non-biliary causes), coupled with its widespread use. If the diagnosis of AP remains uncertain after TAUS, evaluation with CT or MRI is recommended. (Level of Evidence: 2B, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.4%)).

Comment : In the early stages of AP, radiological findings may not be pronounced and can even appear normal.58 However, imaging can reveal features such as focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement, irregular contours, parenchymal heterogeneity, increased density of peripancreatic fat planes, and intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal fluid collections.59 A meta-analysis comparing CT and MRI in diagnosing AP indicated that MRI is superior to CT in terms of sensitivity and specificity. According to this meta-analysis, the diagnostic sensitivity of MRI for AP is 92% and its specificity is 74%, while CT has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 64%.60 Additionally, a study assessing mild forms of AP found that MRI is particularly superior to CT in demonstrating peripancreatic inflammation.61 Magnetic resonance imaging offers additional advantages over CT due to its high resolution and lack of radiation exposure. Nevertheless, MRI has limitations, including long acquisition times, higher costs, less widespread availability, motion artifacts, inability to allow for interventional therapeutic procedures, and lower sensitivity in detecting gas bubbles and calcifications. There are also studies indicating that in cases of mild or uncomplicated AP, methods such as CT or MRI do not provide additional benefits.62

In the diagnosis of AP, TAUS should be the imaging method of first choice. However, it should be noted that in patients with atypical pain, severe pancreatitis, or suspected complications, TAUS may not fully replace CT or MRI.63 Additionally, conventional TAUS is not as sensitive as CT and MRI in detecting pancreatic necrosis and masses.58 While TAUS has a sensitivity of 95% for detecting cholelithiasis, its sensitivity for detecting choledocholithiasis ranges between 50-80%.64

4. Severity of AP

Question 4.1: How is the severity of AP categorized?

Recommendation 4.1:

The severity of AP is categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the presence of local and systemic complications, as well as the state of necrosis and infected necrosis. The Revised Atlanta Classification is the most commonly used classification for this purpose. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (96.7%)).

Comment : The severity of AP is categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the presence of local and systemic complications, as well as the state of necrosis and infected necrosis. The Revised Atlanta Classification (Supplementary Table 2) is the most commonly used classification for this purpose, categorizing AP as follows:

Supplementary Table 2.

Revised Atlanta Criteria for Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

| Severity Grades | Criteria |

| Mild |

|

| Moderate |

|

| Severe |

|

Local complications: Pancreatic/peripancreatic necrosis (sterile or infected), peripancreatic fluid collections, pseudocyst, walled-off necrosis (sterile or infected).

Mild AP (interstitial edematous pancreatitis): There is no organ failure, and no local or systemic complications. It generally resolves within the first week.

Moderate AP: There is transient organ failure that resolves within 48 hours.

Severe AP: There is persistent organ failure involving one or more organs.65

Evaluating the severity of the disease solely based on clinical signs and symptoms is often unreliable and should be supported by objective measures. It is important to classify the severity of AP early, as patients with AP are at risk of developing persistent organ failure. Additionally, mortality rates differ among subtypes of AP. For instance, the mortality rate for mild edematous AP is 1%, whereas it reaches 15-25% for severe necrotizing AP.66,67 To reduce the mortality rate and improve prognosis in severe AP, it is crucial to assess the severity of AP early in the disease course, initiate appropriate treatment based on etiology, recognize pancreatitis complications early, and determine the need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

Question 4.2: Are there clinical-radiological scoring systems and biochemical markers that can aid in the early identification of severe AP?

Recommendation 4.2:

-

Rapid and accurate prediction of severe AP is essential for improving patient prognosis.

There is insufficient evidence and consensus on a “gold standard” biochemical parameter or prognostic score for predicting severe AP.

Elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels during the course of AP or at 48 hours are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 150 mg/L (15 mg/dL) at 48 hours can be used as an indicator of poor prognosis in AP.

Given its simplicity in calculation and comparability to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score is the recommended scoring system for routine clinical practice.

Imaging-based indices such as the computed tomography severity index (CTSI) and modified CTSI (mCTSI) can be useful in predicting severe AP and persistent organ failure due to their high positive predictive values. (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (91.7%)).

Comment : Severe AP has high morbidity and mortality rates, necessitating the early identification of potential cases for aggressive treatment.52,68 Rapid and accurate prediction of the progression of severe AP is essential to improve patient prognosis.69 Although numerous studies have been conducted on various parameters and scoring systems, there is still no sufficient evidence or consensus on a “gold standard” biochemical parameter or prognostic score for predicting severe AP.

To identify severe AP, multiple scoring systems with varying accuracy and low positive predictive values exist, none of which exhibit very high sensitivity or specificity. These include the Ranson criteria, CTSI, APACHE II score, Glasgow system, Harmless Acute Pancreatitis Score (HAPS), PANC 3, Japanese severity score (JSS), pancreatitis outcome prediction (POP), and BISAP score. Bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis is one of the most accurate and applicable scoring systems in daily clinical practice because it is simpler than traditional scoring methods, can be used within the first 24 hours, and closely predicts AP severity, organ failure, and mortality, similar to the complex APACHE II system. A BISAP score greater than 2 is sensitive for predicting severe AP (Area under the curve (AUC) 0.76-0.96; 61-97.6%), morbidity (AUC 0.67-0.93; 40-89%), and mortality (AUC 0.79-0.97; 75-100%). Mortality is below 1% with a BISAP score of 0, but it reaches 22% when the score is 5 (Supplementary Table 3).70-79

Supplementary Table 3.

BISAP Scoring System

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | BUN >25 mg/dL (8.9 mmol/L) (1 point) |

| Impaired mental status | Abnormal mental status with a Glasgow coma score <15 (1 point) |

| SIRS | Evidence of SIRS (1 point) |

| Age | Age >60 years old (1 point) |

| Pleural effusion | Imaging study reveals pleural effusion (1 point) |

0-2 points: Lower mortality (<2%)

3-5 points: Higher mortality (>15%)

SIRS (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome) is diagnosed by the presence of any 2 of the following criteria:

1) Temperature (<36°C or >38°C),

2) Pulse >90/min,

3) Respiratory rate >20 or PaCO2 <32mmHg, and 4) WBC > 12 000/mm3 or <4000/mm3 or >10% bands.

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

There are publications indicating that the rise in BUN and creatinine levels within the first 48 hours of AP suggests that pancreatitis will likely be severe, with high morbidity and mortality.71,72,80

Serum CRP and procalcitonin (PCT) levels can also be useful in predicting the severity of AP. A CRP level higher than 150 mg/L (15 mg/dl) at 48 hours from symptom onset has an 86% sensitivity and a 61% specificity in predicting the severity of AP.81 Similarly, a meta-analysis evaluating PCT as a diagnostic marker in severe AP found a sensitivity of 0.84, a specificity of 0.81, a diagnostic odds ratio of 21.26, and an AUC of 0.89.82 Another meta-analysis reported sensitivity, specificity, and AUC values of 0.73, 0.87, and 0.88, respectively, when using a PCT threshold value greater than 0.5 ng/mL, indicating that serum PCT is a reliable indicator of severe AP.83 Indices associated with imaging methods such as the Extra-pancreatic Inflammation on CT (EPIC) score, CTSI, and mCTSI can also be useful in predicting the severity of AP.74-79,84

5. Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis

It is important to initiate AP treatment early. In these patients, the basis of treatment includes pain relief, fluid replacement, combatting infections, providing nutritional support, tailoring treatment to the etiology, and addressing complications that arise during the course of the disease.

Question 5.1: How should fluid therapy be done in AP?

Recommendation 5.1:

-

Early fluid therapy is important in the treatment of AP.

The fluid used in treatment should be isotonic crystalloid (isotonic NaCl or Ringer’s lactate (RL)). If there is no contraindication specific to the patient (e.g., hypercalcemia), RL can be preferred.

There is insufficient evidence regarding the use of hydroxyethyl starch (HES) in AP treatment. Its use is not recommended in AP treatment except for abdominal compartment syndrome.

The rate of fluid resuscitation should be tailored according to the patient’s clinical assessment at presentation and follow-up data (targeted).

Aggressive fluid therapy in AP, particularly in moderate to severe and severe AP patients, is not recommended as it increases the risk of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), organ failure, the need for intensive care and ventilation, and the development of abdominal compartment syndrome. (Level of evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (94.7%)).

Comment : The correct management of fluid therapy in patients with AP is crucial. The period encompassing the first 72 hours from the onset of symptoms, referred to as the “golden hours,” is particularly critical. During this period, the treatment of intravascular hypovolemia, which can result from a severe inflammatory response, can be achieved with personalized, appropriate fluid support.85 Fluid therapy is especially important in severe AP due to its impact on early mortality and morbidity. Intravenous (IV) fluid therapy should be initiated immediately and at the highest possible targeted dose in patients diagnosed with AP or those being evaluated with a preliminary diagnosis of AP. The targeted initial fluid therapy should be determined by the attending physician based on clinical data at the time of presentation, such as cardiovascular or respiratory failure, hypo/hypervolemic status, renal failure, and hypercalcemia. While the definition of aggressive fluid therapy varies across studies, it can generally be characterized as IV hydration at a rate of 3 mg/kg/hour or more, independent of the initial bolus fluid loading therapy. Although previous studies found aggressive fluid therapy beneficial, its current use is not recommended in severe AP patients due to the potential for causing SIRS, organ failure, and abdominal compartment syndrome, as well as increasing the need for intensive care and ventilation.86-88 The rate of maintenance fluid therapy following the initial treatment should be determined by evaluating the patient’s clinical data, such as urinary volume, and signs of respiratory and circulatory failure.

In patients with AP, the fluid administered for replacement therapy should be an isotonic crystalloid solution (RL or normal saline). There is no difference between these 2 fluid therapies concerning mortality, local complications, or inflammatory parameters.89-92 However, a reduced need for intensive care has been observed in patients treated with RL. Although this effect is thought to be due to the anti-inflammatory properties of the lactate in RL, no significant difference in inflammatory parameters has been found between patients given isotonic normal saline and those given RL. Additionally, it has been observed that administering large volumes of normal saline in a short period increases metabolic acidosis.93,94 Thus, if there are no contraindications such as hypercalcemia, RL should be the first choice of fluid in treatment.

There is insufficient data regarding the use of osmotically active fluids like HES in the treatment of AP. Although some studies have shown that HES can reduce intra-abdominal pressure in patients who develop compartment syndrome, it has not been found to have an effect on mortality or inflammatory parameters.95,96 In a study involving 7000 patients admitted to intensive care for any reason, it was observed that those who received HES had an increased need for renal replacement therapy.97 Therefore, while HES can be added to treatment if abdominal compartment syndrome is present in severe cases of AP, its routine use is not recommended.

Question 5.2: How should the medical treatment of pain in AP be?

Recommendation 5.2:

Pain in AP is usually severe, necessitating pain control in most patients.

There is no sufficient evidence or consensus on the optimal analgesic and route of administration for pain associated with AP.

In the first 24 hours of AP treatment, opioid and non-opioid analgesics have similar efficacy and safety profiles.

Although opioid analgesics (Buprenorphine, pethidine, fentanyl, pentazocine, morphine, tramadol) are effective, special caution should be exercised regarding pethidine and morphine due to their side effects.

In patients with mild AP, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Indomethacin, metamizole, dexketoprofen, diclofenac) have similar efficacy to opioids in pain palliation during the first 24 hours and can be used as alternatives to opioids. They should not be used in patients with renal failure.

Although rarely used for pain palliation in the first 24 hours, epidural analgesic applications have been found effective. They can be employed as alternatives to or in combination with opioids before transitioning to other treatments. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.6%)).

Comment : Abdominal pain is the main symptom in almost all patients with AP who present to the hospital.98 The pain is often severe and requires effective medical management. Early and adequate pain control within the first 24 hours of hospitalization in patients diagnosed with AP improves quality of life and reduces patient anxiety, respiratory stress, hospital stay duration, and the risk of AP-related complications.99 Additionally, early analgesic use has been shown not to delay the diagnosis and treatment of AP.100 Although there are many pharmacological treatment options for managing pain in AP, opioid analgesics are the most commonly used. Agents such as buprenorphine, pethidine, morphine, and fentanyl can be administered parenterally. However, uncertainties remain regarding the clinical efficacy and safety of opioids. Since abdominal pain in AP is due to parenchymal inflammation, NSAIDs are used in pain management by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis through targeting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme. Non-steroidal a nti-inflammatory d rugs are not frequently preferred due to potential renal damage and gastrointestinal system (GIS) complications, but they have been shown to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, improve histopathological changes, and decrease potential systemic complications.101 Local anesthetics (e.g., procaine, bupivacaine) and paracetamol are also used less frequently to treat pain in AP.102 When local anesthetics are used systemically, they provide pain control through anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and motility-regulating effects.103 Epidural analgesia has been shown to improve pain scores, increase capillary perfusion in the GIS mucosa, prevent sepsis, and reduce the risk of respiratory depression in AP.104

The primary concern related to opioids is their potential to complicate the disease by causing sphincter of Oddi spasm. While it is suggested that this increase in pressure is associated with the plasma concentration and dosage of opioids, the clinical significance of this relationship remains unclear. This ambiguity arises because many studies are small-scale observational studies, and there is a lack of definitive evidence from controlled clinical trials supporting this theory.105 Additionally, side effects such as respiratory depression, paralytic ileus at high doses, and the widespread issue of opioid addiction necessitate the search for alternative treatments in the management of AP. Despite some evidence from RCTs, there is still no consensus on the most appropriate analgesics, their dosages, administration methods, and frequencies for treating pain associated with AP.

While optimal treatment strategies for managing pain associated with AP continue to be explored, 2 meta-analyses have been published in the last 2 years on this subject. The first is a meta-analysis by Thavanesan et al106, which evaluated 12 RCTs involving a total of 542 AP patients and reported significant methodological heterogeneity. The included studies compared opioids, NSAIDs, local anesthetics, epidural analgesia, paracetamol, and placebo for pain management in AP. This meta-analysis revealed that epidural analgesia provided the greatest improvement in VAS scores during the first 24 hours, although its effectiveness plateaued and became comparable to opioids at 48 hours. Continuous epidural analgesia infusion is not recommended for mild to moderate AP cases due to potential side effects like hypotension related to catheter placement and epidural abscesses. Additionally, NSAIDs provided similar pain relief to opioids in the first 24 hours, while local anesthetics were the least effective among all treatment agents in terms of pain palliation. Overall, comparisons of VAS score improvements at baseline and on day 1 indicated that opioids and non-opioids were similarly effective.

In a meta-analysis published by Cai et al107 in 2021, 12 RCTs involving a total of 699 patients were evaluated to assess the effectiveness of pain management in AP, with the primary endpoint being the number of patients requiring rescue analgesia. Among the included patients, 83% had mild AP. Both opioid and non-opioid analgesics reduced the need for a second opioid analgesic as rescue medication without significantly altering pain scores in the first 24 hours. Based on the results of studies with high heterogeneity, it was observed that the need for rescue analgesia was lower in the opioid group compared to the non-opioid group, although there was no significant difference in the changes in VAS scores between the 2 groups within the first 24 hours.108 Other subgroup analyses demonstrated no significant differences in efficacy and side effect rates between opioids and NSAIDs. In light of these findings, NSAIDs may be preferred over opioids as the first-line treatment for pain palliation in AP patients. However, due to the moderate quality and high heterogeneity of the included RCTs, a high-level recommendation for pain palliation in AP cannot be made. The heterogeneity among the studies is primarily due to differences in the routes of administration and dosages of the analgesics used.

According to a review by Wu et al101 in 2020, which evaluated the use of NSAIDs in the treatment of pain in AP across 36 studies (including 5 clinical trials with 580 patients and 31 animal studies), NSAIDs were found to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, pain, systemic complications, and mortality rates, with a very low likelihood of serious side effects.

In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence and consensus regarding the most appropriate analgesic and route of administration for the treatment of pain associated with AP. Within the first 24 hours of AP treatment, opioids and non-opioid analgesics exhibit similar efficacy and safety profiles. For the palliation of pain in mild to moderate cases of AP, both NSAIDs and opioids can be considered appropriate options. While opioids are generally used for pain palliation in patients with severe AP, there is a lack of sufficient evidence to determine the optimal pain management strategy.

Question 5.3: How should nutrition be managed in AP?

Recommendation 5.3:

Unless there is an obstruction or contraindication to oral feeding (e.g., ileus, abdominal compartment syndrome), oral intake should not be discontinued. (Level of Evidence: 1B, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (78.4%)).

If oral feeding cannot be initiated within the first 72 hours, nutritional support should be provided. For patients who cannot tolerate oral feeding, enteral nutrition (EN) should be prioritized. Feeding should commence using a nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal (NJ) tube. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (79%)).

For patients who cannot tolerate EN, where NG/NJ tube placement is not possible, or where target protein and calorie needs cannot be met by EN alone, parenteral nutrition (PN) should be administered. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.9%)).

Glutamine should be added to the nutritional solution for patients requiring nutritional support. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (84.9%)).

Comment : Despite the known positive impact of oral feeding on the course of AP, there is no consensus regarding the optimal time to initiate oral feeding. Recently, RCTs and meta-analyses based on these studies have been added to the literature, suggesting that oral intake should not be discontinued unless there is intolerance, contraindication, or another barrier to oral feeding.109-112 No significant differences in the incidence of SIRS or the exacerbation of disease symptoms have been reported between patients who started oral feeding at the earliest possible time and those whose oral feeding was delayed.110 In cases of mild AP, early oral feeding has been found to be safe and may accelerate recovery. These studies have shown that starting a normal solid diet in patients with mild AP reduces the duration of hospital stay and does not increase abdominal pain.

In patients who cannot tolerate oral feeding, the first choice should be EN. Enteral nutrition maintains the integrity of the intestinal mucosa, stimulates gut motility, prevents bacterial overgrowth, and increases splanchnic blood flow.113 Several RCTs and meta-analyses have demonstrated the superiority of EN over PN in the management of AP.114-119 Enteral nutrition has been found to reduce septic complications and inflammation more rapidly than PN, while also being cost-effective.118 Another meta-analysis comparing EN and PN found no differences in mortality and non-infectious complications, but EN was superior in terms of infections, surgical intervention requirements, and length of hospital stay.117 Additionally, 1 RCT noted that EN reduced infectious complications, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and mortality in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis, although other studies have reported no difference between EN and PN.120,121 It has been shown that initiating EN early (within 24-48 hours) is feasible, safe, well-tolerated, and provides significant clinical benefits over delayed EN in terms of mortality, organ failure, and infectious complications.122-129

For EN, either NG or NJ routes can be used. A meta-analysis found that, in patients with severe AP, NG and NJ feeding were similar in terms of mortality rate, tracheal aspiration, diarrhea, exacerbation of pain, and energy balance.130 The placement of NG tubes is significantly easier, more comfortable, and less expensive.131,132

In EN, both semi-elemental and polymeric feeding formulas can be used. Although both types of formulas are well tolerated in patients with AP, semi-elemental nutrition is thought to have more favorable clinical effects; however, the level of evidence supporting this is weak.133 It is recommended that enteral feeding be initiated with standard polymeric formulas in patients with severe AP.134

In patients who cannot tolerate EN, cannot have an NG/NJ tube placed, or cannot meet their target protein and calorie needs with EN alone, PN should be administered. While glutamine supplementation is not necessary for patients receiving EN, those on PN should be supplemented with 0.20 g/kg of L-glutamine daily.135,136 Studies have shown that glutamine supplementation in patients with AP has positive effects on serum albumin levels, CRP, infectious complications, length of hospital stay, and mortality.137-140 Apart from glutamine, immunonutrition has no established role in severe AP.

The addition of probiotics to the nutrition of patients with AP has not been shown to provide significant benefits in terms of pancreatic infection, systemic infection, the need for surgery, length of hospital stay, or mortality. In fact, one study observed higher mortality in the probiotic group.141,142

In patients with severe AP, nutritional support should provide 25-35 kcal/kg/day of energy, 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day of protein (unless there is renal failure or severe liver failure), 3-6 g/kg/day of carbohydrates, and up to 2 g/kg/day of lipids. Daily supplementation with multivitamins and trace elements is also recommended.142

5.4. Antibiotic Treatment

Question 5.4.1: In what situations should systemic antibiotic treatment be initiated in AP?

Recommendation 5.4.1:

The use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended in AP, including severe pancreatitis and the presence of necrosis. However, antibiotics are recommended in cases of infected necrosis and extrapancreatic infections. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (89.1%)).

Comment : In meta-analyses conducted before the year 2000, which included a small number of patients, it was reported that the use of prophylactic antibiotics in AP reduced mortality.143-145 However, results from meta-analyses and systematic reviews published from 2000 onwards have shown that routine prophylactic antibiotic use has no effect on mortality, morbidity, length of hospital stay, or the need for surgery in AP cases.143,146- 153 In light of these findings, routine prophylactic antibiotic use is not recommended during AP attacks, regardless of the type (interstitial or necrotizing) or severity of pancreatitis. Nevertheless, approximately 20% of AP patients may develop extrapancreatic infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, or acute cholangitis.154 Since these extrapancreatic infections are associated with increased mortality and morbidity, appropriate antibiotic treatment is recommended. If culture results are negative or no infectious focus is found, discontinuation of antibiotic use is advised.155

Antibiotic therapy is recommended in the presence of infected necrosis.155 There is no correlation between the extent of necrosis and the frequency of infection. Although infection typically appears around 10 days after the onset of necrosis, it can also occur in its early stages.156,157 Fungal infections are detected in 6-46% of bacterial cultures taken from sites of infected necrosis.158 However, the impact of prophylactic antifungal treatment on prognosis and mortality is unclear. Therefore, prophylactic antifungal treatment is also not recommended.159

Question 5.4.2: Which antibiotics should be preferred in AP?

Recommendation 5.4.2:

In AP, carbapenems, quinolones, metronidazole, and cephalosporins can be used. In the presence of infected necrosis, carbapenem antibiotics should be preferred. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (95.4%)).

Comment : Infected necrosis pathogens are typically of intestinal origin (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Enterococcus) and are usually monomicrobial. The presence of gas in the necrotic area on imaging supports infection and necessitates antibiotic treatment. Very few antibiotics can penetrate pancreatic necrosis. Studies on antibiotic use in acute necrotizing pancreatitis have shown the use of imipenem, meropenem, a combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, or ciprofloxacin alone. According to the results of these studies, carbapenem antibiotics should be preferred first due to their higher pancreatic penetration.160- 165

5.5. Treatments Targeting Etiology

Question 5.5.1: When should ERCP be performed in patients with Acute Biliary Pancreatitis?

Recommendation 5.5.1:

In acute biliary pancreatitis, if there are signs of a stone impacted in the papilla or cholangitis, ERCP is recommended at the earliest possible stage. If these conditions are not present but there are signs of cholestasis, imaging of the common bile duct (endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)) is recommended. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (100%)).

Comment : In cases of acute biliary pancreatitis where ERCP is indicated, there remains uncertainty in the literature regarding whether the procedure should be performed within 24 hours or within 72 hours. The timing of endoscopic intervention should be determined based on the patient’s clinical condition, comorbidities, and medications they are taking. A recent meta-analysis by Iqbal et al166 found that performing ERCP within the first 48 hours in cases of acute cholangitis significantly reduced in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, and hospital stay duration.

According to a Cochrane analysis conducted in 2012, early ERCP (<72 hours) in cases of acute cholangitis with biliary pancreatitis is superior to conservative treatment or elective ERCP in terms of mortality, hospital stay, and morbidity. In cases of biliary obstruction without cholangitis, early ERCP is also superior to conservative treatment or elective ERCP in reducing morbidity and preventing the development of local and systemic complications.167 A review by Shuntaro Mukai et al168 indicated that performing ERCP in patients with ongoing cholangitis and biliary obstruction significantly reduces mortality, morbidity, local complications, and sepsis compared to conservative treatment. According to the Tokyo 2018 guidelines, the diagnosis of acute cholangitis is established through clinical, laboratory, and imaging methods (fever and/or chills, elevated CRP levels, leukocytosis or other elevated inflammatory parameters, jaundice, and a 1.5-fold increase in aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels, with biliary dilation detected on imaging).169

According to a meta-analysis involving cases of biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis and impacted bile stones, early ERCP does not significantly differ from conservative treatment in terms of mortality (OR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.32-1.09; P = .09), complication development (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.30-1.01; P = .05), new-onset organ failure (OR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.65-1.75; P = .81), development of pancreatic necrosis (OR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.49-1.32; P = .38), development of pancreatic pseudocyst (PP) (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.16-1.24; P = .12), ICU admission (OR: 1.64, 95% CI: 0.97-2.77; P = .06), and pneumonia development (OR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.40-1.65; P = .56).170 Therefore, it is essential to assess the presence of stones in the biliary tract and plan ERCP for necessary cases. Endoscopic ultrasonography and MRCP are commonly used investigations for evaluating stones in the biliary tract. Endoscopic ultrasonography is particularly valuable for stones smaller than 5 mm. The sensitivity and specificity of EUS and MRCP for detecting stones in the biliary tract are 97% vs. 90% and 87% vs. 92%, respectively.171

Question 5.5.2: How should HTG-induced AP treatment (beyond standard treatment) be administered? What are the treatment options?

Recommendation 5.5.2:

It is recommended to add insulin infusion to the treatment of HTG-induced AP (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (91.2)).

There is insufficient evidence on the additional benefit of adding heparin infusion to insulin infusion (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (74.3%)).

Plasmapheresis has not been shown to provide additional benefit when combined with insulin infusion (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (74.3%)).

Comment : In HTG-induced AP, additional treatments beyond standard pancreatitis therapy include the administration of insulin and/or heparin, and plasmapheresis. Insulin aids in lowering TG levels by increasing peripheral lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity. Specifically, an IV insulin infusion at 0.1-0.4 units/kg/hour is preferred over subcutaneous (SC) insulin due to its easier monitoring and dose planning.172,173 A meta-analysis involving 118 cases indicated that, although the number of cases in the included studies was limited, intensive insulin therapy significantly reduced APACHE II scores at the 72-hour mark of treatment.174 In a study comparing insulin therapy and conservative AP treatment in HTG-induced AP (HTG-AP), TG reduction on days 2 and 4 were 69% vs. 85% and 63% vs. 79%, respectively, with no significant difference detected between the groups.175

Heparin also causes the release of LPL from endothelial cells, leading to a reduction in TG levels; however, prolonged administration of heparin results in the depletion of LPL stores, decreased chylomicron catabolism, and rebound HTG.176 In a retrospective study comparing insulin and heparin treatments, insulin was found to have a greater TG-lowering effect than heparin in cases of edematous pancreatitis, with no differences in complications observed between the 2 groups.177

Plasmapheresis treatment has been compared with insulin infusion and/or heparin therapy in numerous studies. In a 2022 meta-analysis by Yan LH et al178, although a significant reduction in TG levels at 24 hours was observed with plasmapheresis compared to conventional therapy, no differences were found in hospital stay duration, mortality, or morbidity. Another meta-analysis evaluating 934 patients also found no differences in efficacy and safety between plasmapheresis and conventional treatment.179

5.5.3. Acute Pancreatitis Due to Other Etiologies

Question 5.5.3.1: How should the alcohol cessation support program be for patients with acute alcoholic pancreatitis?

Recommendation 5.5.3.1:

A brief alcohol intervention is recommended to prevent an acute alcoholic pancreatitis attack. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (76.2%)).

Comment : Excessive alcohol consumption not only leads to significant mortality and morbidity but also causes social problems. To reduce heavy drinking, brief advice or brief counseling provided by doctors and nurses can be important.180 Brief interventions include feedback on risky alcohol use and health-related harms, identification of high-risk situations for heavy drinking, simple advice on reducing intake, strategies to increase motivation for behavior change, and the development of a personal plan. These brief interventions typically consist of 1-5 sessions of orally delivered information, advice, or counseling, designed to last 5-15 minutes with doctors and about 20-30 minutes with nurses.181

According to a meta-analysis of 22 RCTs involving 7619 participants, which did not include patients with alcoholic pancreatitis, counseling for alcohol cessation is important in preventing attacks of alcoholic pancreatitis. Participants who received brief interventions consumed less alcohol over a follow-up period of 1 year or longer compared to the control group that only received assessments. Additionally, longer interventions did not result in a significant reduction in alcohol consumption compared to brief interventions.182 Given the numerous studies conducted since the 2007 Cochrane review, an update was performed in 2017. This update included 69 studies randomizing a total of 33 642 participants, allowing for new subgroup analyses. The primary meta-analysis, which included 34 studies, provided moderate-quality evidence that participants who received brief interventions consumed less alcohol 1 year later compared to those who received minimal or no intervention.180

Another meta-analysis involving 22 RCTs suggested that multi-session brief interventions may be particularly beneficial in reducing alcohol consumption among non-dependent patients. However, due to the lack of quantitative analysis, additional evidence is needed to reach more robust conclusions.183

In another RCT, patients presenting to the hospital with alcohol-related AP were randomized to receive either repeated interventions or only an initial intervention against alcohol consumption. The group receiving repeated interventions, which included follow-up visits at outpatient clinics every 6 months over a period of 2 years, showed a reduction in the recurrence of AP compared to the group that only received the initial intervention during hospitalization. This resulted in a decrease in hospitalization rates.184

Question 5.5.3.2: Can the same drug be used again in patients with drug-related AP?

Recommendation 5.5.3.2:

The suspected drug should not be reused in cases of drug-related AP. However, if the drug is absolutely necessary for the disease, it may be used with close monitoring and dose reduction. (Level of Evidence: 3, Strength of recommendation: Weak consensus (75.2%)).

Comment : Although drug-induced AP is rare, identifying a drug as the cause of AP presents a challenge for clinicians.185 Most of the available data come from case reports or case-control studies. If the benefits of the drug causing AP outweigh its risks or the potential for another severe AP attack, the drug may be reused.186 While the exact cause of drug-induced pancreatic damage is unknown, it can be categorized into those drugs with dose-dependent intrinsic toxicity and those causing damage through idiosyncratic reactions in the host.187

A comprehensive analysis of 1060 cases of drug-induced AP observed that most drugs causing severe AP were administered to treat significant pathologies, cancers, and autoimmune diseases. The more severe the disease, the higher doses of the offending drugs were used, leading to severe AP. In this analysis, when the problematic drug was re-administered at a reduced dose, it led to less severe outcomes. If reuse of the drug is necessary, close monitoring of the patients and administering a reduced dose of the drug are recommended.188 Another study analyzing 250 cases of drug-induced pancreatitis suggested that if the diagnosis of drug-induced pancreatitis is highly suspicious, the patient significantly benefits from the responsible drug, and there are no alternative medications to treat the serious disease, the drug may be cautiously reintroduced despite the risks.184

Question 5.6: What are the indications for referral to a tertiary center and ICU admission in AP patients?

Recommendation 5.6:

Patients with a BISAP score of 3 or higher at diagnosis and those experiencing moderate or severe attacks according to the revised Atlanta criteria during follow-up should be promptly referred to a tertiary center. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.2%)).

Patients with confirmed or strongly suspected biliary etiology (those considered for ERCP and/or cholecystectomy) should be referred to specialized centers. (Level of Evidence: 2B, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.2%)).

Acute pancreatitis has a rapidly changing prognosis and should be closely monitored, especially within the first 48 hours. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (88.4%)).

Patients with persistent organ dysfunction should be monitored in an ICU. (Level of Evidence: 1A, Strength of recommendation: Strong consensus (87.7%)).

Comment : It is known that the course of AP can change rapidly, especially with treatment during the first 48 hour.66,190,191 Therefore, patients diagnosed with AP should be closely monitored in the initial hours, and necessary treatments should be promptly administered. Additionally, a study on the treatment of AP within the first 72 hours has demonstrated the impact of early intervention on the prognosis of the disease.192 Risk assessments should be conducted at the time of diagnosis to determine the disease prognosis. Patients with moderate or severe AP should be quickly referred to tertiary hospitals due to the need for intensive care.66,190 The BISAP and revised Atlanta criteria are recommended scoring systems in this context.191