Abstract

Understanding how embryonic progenitors decode extrinsic signals and transform into lineage-specific regulatory networks to drive cell fate specification is a fundamental, yet challenging question. Here, we develop a new model of surface epithelium (SE) differentiation induced by human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) using retinoic acid (RA), and identify BMP4 as an essential downstream signal in this process. We show that the retinoid X receptors, RXRA and RXRB, orchestrate SE commitment by shaping lineage-specific epigenetic and transcriptomic landscapes. Moreover, we find that TCF7, as a RA effector, regulates the transition from pluripotency to SE initiation by directly silencing pluripotency genes and activating SE genes. MSX2, a downstream activator of TCF7, primes the SE chromatin accessibility landscape and activates SE genes. Our work reveals the regulatory hierarchy between key morphogens RA and BMP4 in SE development, and demonstrates how the TCF7-MSX2 axis governs SE fate, providing novel insights into RA-mediated regulatory principles.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-024-05525-4.

Keywords: Retinoic acid, Surface epithelium, TCF7, MSX2

Introduction

Extracellular signaling molecules known as morphogens play key roles in instructing and reinforcing cell fate and have been widely used to direct the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into various lineages in vitro [1, 2]. Large-scale studies have shown that the roles of morphogens in lineage determination are diverse and act in a concentration-, duration-, and cellular context-dependent manner [1–5]. For example, the rostral-to-caudal neural axis specification in early embryo development can be recreated by a linear gradient of WNT signals [6]. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) stimulation displays time-dependent effects on embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation: short-term BMP4 stimulation can mediate ESC differentiation into the primitive streak and mesoderm and long-term BMP4 treatment leads to trophoblast differentiation [7, 8]. In the absence of WNT signals, FGF signals induce epiblast cells into a neural fate; in the presence of WNT signals, FGF signals are repressed, driving epiblast cells toward an epidermal fate [9]. Despite the significance of morphogens in lineage fate commitments, there is a paucity of knowledge on how morphogen signaling cues are transformed into lineage-specific regulatory networks to orchestrate cell fate determination.

Retinoic acid (RA), a metabolic product of retinol (vitamin A), is well known for its influence on cell fate commitment during early embryogenesis and the maintenance of adult tissue homeostasis [10–12]. Previous studies have reported that RA signaling regulates the development of many organs and tissues, including the forebrain, forelimbs, body axis, spinal cord, eyes, heart, and reproductive tract [10–12]. The cellular effects of RA are mainly mediated by the activation of retinoid X receptor (RXR) and RA receptor (RAR) heterodimers. RXRs and RARs belong to two subfamilies of nuclear receptors, both containing three subtypes (α, β, and γ), that function as transcription factors (TFs) to bind to the RA-response element, recruit co-regulators such as TFs and epigenetic remodelers, and control transcriptional programs [11, 13]. However, a comprehensive dissection of the exact regulatory mechanisms of RA signaling in specific developmental contexts is required to fully understand the developmental transcriptional decisions.

A single-layered surface epithelium (SE) is derived from the ectoderm and expresses the epithelial markers keratin 8 (KRT8) and keratin 18 (KRT18) [14]. Previous studies have reported that the RA and BMP4 play crucial roles in SE fate specification during development, and their combined treatment can direct hESC differentiation into SE [15, 16]. Proper development of SE is essential for the normal development and function of the epidermis and other ectodermal appendages, including the oral, corneal, and conjunctival epithelium, as well as mammary glands and hair follicles [17–21]. As differentiation of SE into epidermal cells proceeds, SE commits to form basal keratinocytes expressing the epidermal master regulator, TP63, and the keratinocyte maturation markers, keratin 5 (KRT5) and keratin 14 (KRT14), followed by stratification to produce a multi-layered epidermis [22]. Although recent efforts have begun to identify key TFs of SE and dissect the TF regulatory networks governing SE fate, how morphogens connect with downstream transcription networks that drive SE fate determination remains unclear.

In this study, we developed an efficient SE differentiation system using RA stimulation and delineated the mechanisms by which the complete RA signaling cascade mediates SE fate determination. Our research reveals that BMP4, functioning as the downstream pathway of RA, is essential for mediating SE commitment, highlights the roles of RXRA and RXRB in SE lineage-specific epigenetic and transcriptomic remodeling, and underscores the importance of the TCF7-MSX2 axis in SE development. These findings offer a framework for understanding morphogen regulatory principles and contribute to an improved understanding of cell fate decisions and the advancement of regenerative therapy.

Results

RA is sufficient to drive SE commitment

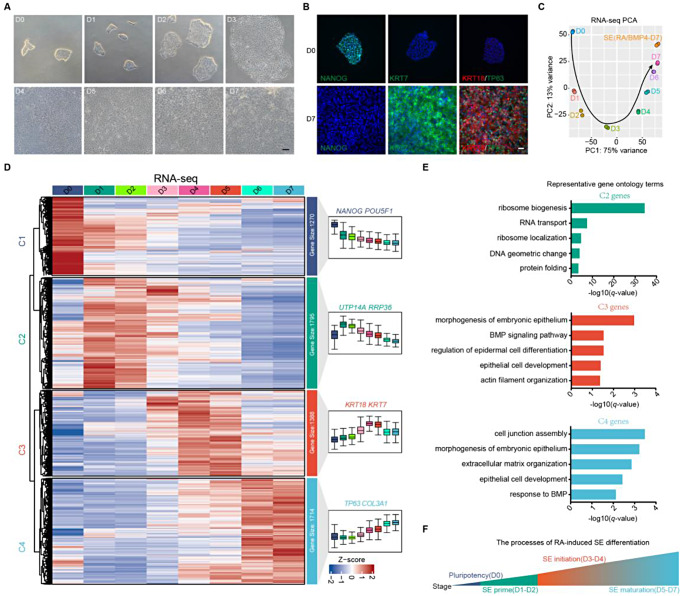

An SE differentiation system was developed using a pluripotency growth medium (mTeSR1) supplemented with RA. After 7 days of RA treatment, hESCs lost their embryonic stem cell morphology and were induced into a nearly homogeneous epithelial-like morphology, with robust expression of the SE markers KRT7 and KRT18 and the epidermal master regulator TP63, while the embryonic stem cell pluripotency marker NANOG was undetectable (Fig. 1A, B). To further confirm the SE differentiation phenotype, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) comparing RA-driven differentiated cells with SE generated according to previously published protocols [16]. Principal components analysis (PCA) revealed that the transcriptome landscape of D7-differentiated cells driven by RA closely resembled that of SE (Fig. 1C). Moreover, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that the transcriptome of D7 SE cells in our system was similar to that of mouse SE at embryonic day 9 [23] (Supplementary Fig. 1A). These results suggest that RA is capable of driving hESCs to acquire an SE phenotype.

Fig. 1.

RA induces SE commitment. A Phase contrast images of the differentiating hESCs during 7 days of RA induction. Scale bar, 100 μm. B Immunostaining for NANOG, KRT7, KRT18, and TP63 in the differentiated cells on D0 and D7. Scale bar, 100 μm. C PCA of RNA-seq data of cells at each time point during RA-driven differentiation and SE cells. D Heatmap of expression changes of the genes that were differentially expressed between at least two time points during 7 days of RA induction. These differential genes were clustered into four groups based on different variation tendency over time. The color bar shows the relative expression value (Z score of TPM [transcripts per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads]) from the RNA-seq data. E Representative GO terms (biological process) identified from the cluster II, III, and IV genes. F Schematic diagram of RA-induced SE differentiation

To determine whether RA-driven SE possesses further differentiation potential, we sequentially cultured the cells in keratinocyte maturation medium and terminal differentiation medium. We observed that the RA-driven SE could successfully differentiated into keratinocytes (hereafter “iKCs”) expressing KRT5, KRT14, TP63, ITGB4, LAMB3, and COL7A1, with decreased KRT8 and KRT18 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1B-D). After calcium-induced terminal differentiation, the iKCs highly expressed the terminal differentiation genes KRT1, KRT10, FLG, LOR, and TGM1, indicating their ability to undergo terminal differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 1B-D). Furthermore, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that the genes preferentially expressed in iKCs (compared with RA-driven SE) were significantly associated with epidermis and skin development, whereas those enriched in terminally differentiated iKCs (compared with iKCs) were preferentially linked to keratinocyte differentiation, cornification, and establishment of the skin barrier (Supplementary Fig. 1E). Thus, these results validate the functional capacity of the RA-driven SE.

To further understand the process of SE fate determination induced by RA, we analyzed transcriptome dynamics during differentiation. 6,167 genes that were differentially expressed (DEGs) across at least two time points were identified and clustered into 4 groups based on the main temporal expression patterns observed during differentiation (Fig. 1D). Specifically, Cluster I DEGs, typified by pluripotency markers NANOG and POU5F1, were highly expressed in hESCs and sharply downregulated as SE differentiation proceeded (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1F). Cluster II DEGs, typified by ribosome assembly genes, UTP14A and RRP36, were progressively upregulated during the first 2 days of differentiation, with enrichment in the ribosome biogenesis, RNA transport, and protein folding, and then gradually declined thereafter (Fig. 1D, E and Supplementary Fig. 1F ). Ribosome biogenesis is known to play key roles in the transition from self-renewal to differentiation [24, 25], implying that during the first 2 days of differentiation, cells prepared for SE initiation by increasing protein synthesis. Cluster III DEGs, typified by SE markers KRT18 and KRT7, were slightly upregulated during the first 2 days of differentiation, abundantly expressed on D3, and peaked on D4 (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1F, G ). These DEGs were preferentially linked to epithelium development, BMP signaling pathway, and actin filament organization (Fig. 1E). Finally, cluster IV DEGs, typified by SE maturation genes TP63 and COL3A1, were gradually upregulated as SE differentiation progressed and were significantly associated with epithelium development, response to BMP, and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 1D, E and Supplementary Fig. 1F).

Taken together, these results confirm that RA is sufficient to drive hESCs to adopt an SE phenotype and that the RA-driven differentiation process can be categorized into four distinct stages: D0 (pluripotency phase), D1-D2 (SE prime phase), D3-D4 (SE initiation phase), and D5-D7 (SE maturation phase) (Fig. 1F).

BMP4 signaling serves as the RA downstream to mediate SE commitment

Given that previous studies have demonstrated the essential role of BMP signaling in SE fate determination and that BMP4 has been used to induce SE fate in vitro [15, 16, 26], we hypothesized that RA may induced SE differentiation by activating endogenous BMP4 signaling. By profiling dynamic changes in BMP family member expression during RA-driven SE differentiation, we discovered BMP4 as the predominantly expressed member during differentiation (Fig. 2A). BMP4 expression is activated on the second day of differentiation, peaks on the third day, and then slightly downregulates while maintaining its expression. (Fig. 2B). Additionally, we observed that RA induced SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSMAD1/5/8), the downstream nuclear effector of BMP signaling, indicating activation of BMP signaling (Fig. 2C). Through functional validation, we found that BMP4-knockdown cells maintained hESC-like morphology and failed to acquire an epithelial-like morphology, with undetectable expression of pSMAD1/5/8, KRT18 and TP63 (Fig. 2C). Meanwhile, BMP4-knockdown cells showed a significant decrease in the expression of SE genes (KRT8, KRT18, KRT7, KRT19, TP63, TFAP2C, and GRHL3) and an upregulation of pluripotency genes (NANOG, POU5F1, SOX2, and DNMT3B) (Fig. 2D, E). Moreover, GO analysis revealed that genes downregulated upon BMP4 depletion were significantly associated with SE development biological processes, such as response to BMP stimulus, embryonic epithelium morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 2F). These results demonstrated that BMP4 signaling as downstream of RA is required to mediate SE fate determination.

Fig. 2.

RA drives SE fate determination by activating BMP4 signaling. A Heatmap of the expression changes of BMP family members during SE differentiation. The color bar shows the expression value (TPM) from the RNA-seq. B Immunostaining of BMP4 during 7 days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. C Phase contrast images and immunostaining for pSMAD1/5/8, KRT18, and TP63 in scrambled shRNA- and shBMP4-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. D qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes in scrambled shRNA- and shBMP4-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. qRT-PCR values were normalized to the values in scrambled shRNA group. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 t test). E Heatmap showing expression levels of representative genes in shBMP4- and scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. F GO (biological process) analysis of the downregulated genes upon BMP4 knockdown. G Scatterplot of differential accessibility in shBMP4- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. Sites identified with significant differential accessibility are highlighted in color (red, peaks increased; green, peaks decreased). H Transcription factor motif enrichment in the regions with increased (left) or decreased (right) accessibility in shBMP4- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. I Genome browser tracks comparing ATAC-seq signal across NANOG, POU5F1, SOX2, KRT8/18, KRT7, and TP63 loci of scrambled shRNA- or shBMP4-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation

Although the role of BMP4 in SE development is well-established, the molecular regulatory mechanisms through which BMP4 controls this process remain unclear. To elucidate the mechanism underlying BMP4-mediated SE commitment, we performed an assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq). Upon BMP4 depletion, we observed substantial changes in global chromatin accessibility and identified 52,644 differentially accessible regions, in which 64.6% and 35.4% of the loci display a marked decrease and increase in chromatin accessibility, respectively (Fig. 2G). Moreover, TF motif enrichment analysis of these loci revealed that the motifs for SE regulators (TFAP2A, TFAP2C, GATA3, and GRHL2) were specifically enriched in loci with decreased accessibility, whereas the motifs for core pluripotent factors (OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG) were specifically enriched in loci with increased accessibility (Fig. 2H). This suggests a significant repression in the binding of SE regulators and an activation in the binding of hESC critical regulators after BMP4 depletion. Specifically, the loci of SE genes (KRT7, KRT8, KRT18, and TP63) favored a closed chromatin state, and the loci of pluripotency genes (NANOG, POU5F1, and SOX2) exhibited a gain in chromatin accessibility in BMP4-knockdown differentiated cell (Fig. 2I). Collectively, these results demonstrate that BMP4 functions downstream of RA and plays a decisive role in SE development by mediating the establishment of the SE chromatin landscape.

RXRA/B prime lineage-specific epigenetic landscape and regulates SE gene expression

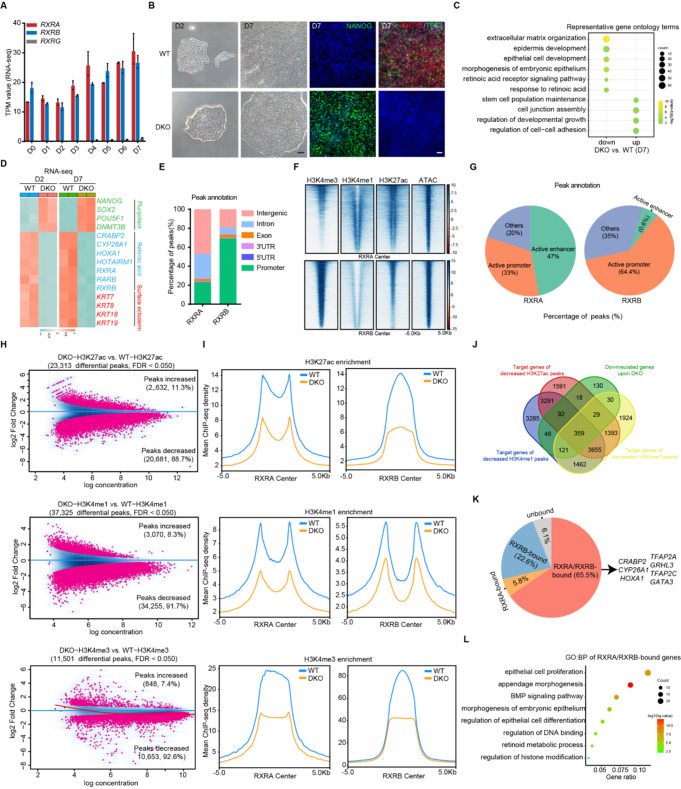

Given that RA played a vital role in SE commitment, we aimed to clarify how RA impels SE determination. RA typically exerts its effects through its nuclear receptors that act as RA-modulated TFs to regulate gene expression [11]. In this study, we focused on elucidating the role of RXRs in RA-driven SE fate determination. We first examined the expression of the three RXR family members (RXRA, RXRB, and RXRG) and observed that RXRA and RXRB were ubiquitously expressed during RA-driven differentiation, whereas RXRG expression was not detectable (Fig. 3A). Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, we generated RXRA-knockout (KO) and RXRB-KO hESCs and found that either RXRA- or RXRB-KO prevented RA-induced SE differentiation of hESCs and inhibited the expression of SE marker genes in the SE initiation stage (Supplementary Fig. 2A-C). However, after 7 days of RA induction, RXRA- and RXRB-KO-differentiated cells displayed a transition to an epithelial-like morphology, with no difference in SE marker gene expression compared with that in the wild-type (WT) group (Supplementary Fig. 2A-C). Based on these results, we speculated that RXRA and RXRB likely function with partial redundancy.

Fig. 3.

RXRA/B primes SE epigenetic and transcriptomic landscape. A RNA-seq analysis of RXRA, RXRB, and RXRG expression during seven days of RA induction. B Left two panels, phase contrast images of the differentiating hESCs on D2 and D7. Scale bar, 100 μm. Right two panels, immunofluorescence staining of NANOG, KRT18, and TP63 in WT and RXRA/B DKO cells after seven days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. C Representative GO terms (biological processes) identified from the genes highly expressed in WT or RXRA/B DKO cells after seven days of differentiation. D Heatmap of expression of pluripotency, RA and SE-related genes in WT and RXRA/B DKO cells after two days or seven days of differentiation. E Histogram showing the distribution patterns of RXRA and RXRB peaks in the differentiated cells on D2. F Heatmaps of binding signals of H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and ATAC-seq at the center of RXRA or RXRB peaks. G Pie chart showing the percentage of RXRA or RXRB peaks located in active enhancers or active promoters. H Scatterplot of differential H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 peaks in WT versus RXRA/B DKO cells after two days of differentiation. Sites identified as differentially bound with significance (FDR < 0.05) are shown in red. I Metaplots of average H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 density around RXRA or RXRB peaks in WT and RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells on D2. J Venn diagram showing the overlap among downregulated genes and the target genes of decreased H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 signals in differentiated WT versus RXRA/B DKO cells on D2. K Pie chart showing percentage of the overlap genes obtained from (J) with or without RXRA and RXRB binding. L Representative GO terms (biological process) identified from the genes bound by both RXRA and RXRB obtained from (K)

Subsequently, we generated RXRA/B double-KO (DKO) hESCs (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 2D). We found that RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells on D7 maintained hESC clonal morphology with robust expression of NANOG, and undetectable expression of KRT18 and TP63, validating the critical role of RXRA/B in RA-driven SE commitment (Fig. 3B). PCA demonstrated that RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells exhibited transcriptome landscapes similar to that of hESCs (Supplementary Fig. 2E). Specifically, RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells exhibited a remarkable reduction in the expression of SE genes (KRT8, KRT18, KRT7, KRT19, TP63, TFAP2C, and GRHL3) and maintained expression of the pluripotency-related genes (NANOG, POU5F1, and SOX2) (Supplementary Fig. 2F-G). GO analysis showed that the genes downregulated in RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells were enriched for epithelium development, response to RA, and extracellular matrix organization, whereas genes preferentially expressed in RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells were associated with stem cell population maintenance and developmental growth regulation (Fig. 3C). These results highlight that RA-driven SE differentiation is governed by RXRA/B.

Given that significant morphological alteration and increased expression of RA and SE -related genes were observed at the SE prime stage (Fig. 3B, D), we focused on investigating the regulatory mechanisms underlying the function of RXRA/B during early RA differentiation. To characterize the global genomic occupancy of RXRA/B, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq). Intriguingly, the distribution analysis of RXRA and RXRB binding maps demonstrated distinct DNA-binding modes: RXRA binding sites were mainly located in intergenic and intronic regions away from the transcription start site, as well as promoter regions, whereas RXRB binding sites were predominantly in promoter regions (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 2H). Moreover, epigenetic modifications in RXRA and RXRB binding sites were determined and annotated based on ChromHMM segmentation annotation (Supplementary Fig. 2I). RXRA binding sites were mainly located in active enhancers (47%) and promoters (33%) rich in H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K4me1 histone modifications, whereas RXRB binding sites were mostly located in active promoters (64.4%) rich in H3K4me3 and H3K27ac histone modifications (Fig. 3F, G).

Lineage commitment is highly dependent on the specific epigenetic environment established by the core lineage-determining TFs that dominate transcriptional decisions [27, 28]. To investigate the roles of RXRA and RXRB in rewiring the epigenetic landscape during SE differentiation, we compared the binding maps of H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 between WT and RXRA/B DKO-differentiated cells at the SE prime stage. We identified 23,313 differential H3K27ac, 37,325 differential H3K4me1, and 11,501 differential H3K4me3 peaks, most of which displayed diminished deposition of H3K27ac (88.7%), H3K4me1 (91.7%), and H3K4me3 (92.6%) (Fig. 3H). Notably, the RXRA and RXRB binding sites showed decreased H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H4K4me3 signals in RXRA/B DKO cells (compared with that in the WT group), suggesting their essential role in epigenetic remodeling underlying RA-driven SE differentiation (Fig. 3I). By combining the epigenome and transcriptome data, we found that 43.4% (359/827) of the genes that were significantly downregulated in RXRA/B DKO cells were accompanied by simultaneous decreases in H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 signals near their loci (Fig. 3J). Additionally, most of these genes (65.5%) contained both RXRA and RXRB binding sites near their loci and were significantly enriched in biological processes of epithelium development, RA metabolism, histone modification, and BMP signaling (Fig. 3K, L). Specifically, RXRA and RXRB bound to loci near RA target genes (CRABP2, CYP26A1, and HOXA1) and SE regulators (TFAP2C, GRHL3, TFAP2A, and GATA3), regulating their H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 deposition and gene expression, whereas in the deficiency of RXRA/B, these processes were remarkably disturbed (Fig. 3K). Taken together, these data demonstrate that RXRA/B modulate SE lineage-specific epigenetic and transcriptomic remodeling.

TCF7 is required for RXRA/B to mediate exit from pluripotency and initiates SE fate determination

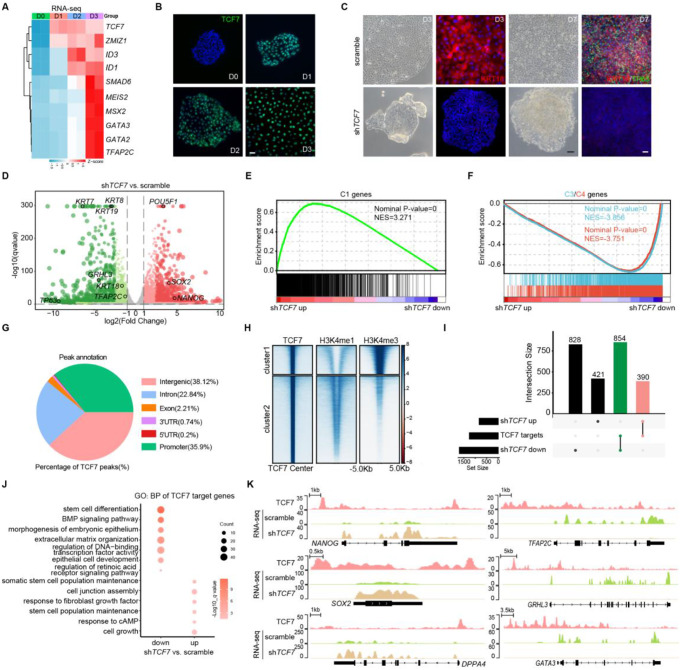

To further uncover the RXRA/B regulatory process, we screened the top 10 differentially expressed downstream TFs of RXRA/B (Fig. 4A). Notably, several of these TFs, including TFAP2C and GATA3, are well-known SE development regulators [16], indicating their potential roles in SE fate determination. We then analyzed the trend of expression changes of the top 10 candidate TFs during the early stages of SE differentiation. We focused on TCF7, which has not previously been reported in SE development and exhibited a substantial increase on the first day of differentiation, to further investigate its involvement in SE commitment (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

TCF7 is required to mediate the transition from pluripotency to SE initiation. A Heatmap of the expression of the top 10 candidate transcription factors during the first three days of differentiation. B Immunostaining of TCF7 during the first three days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. C Phase contrast images and immunostaining for KRT18 and TP63 in scrambled shRNA- and shTCF7-treated hESCs after three or seven days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. D Volcano map of differentially expressed genes of shTCF7- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. The significant DEGs (fold change ≥ 2 and q-value < 0.05) are highlighted in red (upregulated genes) or green (downregulated genes). E GSEA for Cluster I genes in the gene expression matrix of shTCF7- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. F GSEA for Cluster III and IV genes in the gene expression matrix of shTCF7- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. G Pie chart showing the distribution patterns of TCF7 peaks in the differentiated cells on D3. H Heatmaps of binding signals of H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 at the center of TCF7 peaks in the differentiated cells on D3. I Upset plot depicting the overlap between genes bound by TCF7 and the genes that were differentially expressed upon TCF7 depletion. J GO (biological process) analysis of the differentially expressed target genes of TCF7. K Genome browser view of TCF7 peaks and RNA-seq signal across representative loci

We knocked down TCF7 to explore its function during RA-driven SE differentiation. Remarkably, the absence of TCF7 repressed RA-induced SE initiation and prevented cells from acquiring epithelial-like morphology, as indicated by undetectable expression of KRT18 at the SE initiation stage (Fig. 4C). After 7 days of induction, TCF7-knockdown differentiated cells retained the clonal morphology and failed to differentiate into the SE, as evidenced by undetectable KRT8 and TP63 expression, a significant decrease in the expression of SE genes (KRT8, KRT18, KRT7, KRT19, TP63, TFAP2C, and GRHL3), and an upregulation of pluripotency-related genes (POU5F1, SOX2, and NANOG) (Fig. 4C, D). GSEA revealed that Cluster I genes, which are specifically expressed in hESC (shown in Fig. 1D), were upregulated in TCF7-depleted cells, whereas Cluster III and IV genes, which are highly expressed during the SE initiation and maturation stages (shown in Fig. 1D), respectively, were significantly suppressed (Fig. 4E, F).

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying TCF7-mediated SE commitment, we generated the binding map of TCF7 by performing ChIP-seq. The distribution analysis demonstrated that TCF7 binding sites were located in intergenic, intronic, and promoter regions (Fig. 4G). Combined with H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 epigenetic maps, we found that TCF7 binding sites were clustered into two groups: cluster 1 represented promoters with H3K4me3 positivity; cluster 2 were enhancers defined by H3K4me1 enrichment. This indicated that TCF7 regulates downstream genes through promoters and enhancers (Fig. 4H). By integrating TCF7 ChIP-Seq and RNA-seq analyses, we observed that TCF7 targets were enriched among downregulated (854/1682, 50.7%) and upregulated (390/811, 48%) genes, indicating that TCF7 regulates both gene activation and silencing (Fig. 4I). GO analysis showed that the upregulated target genes linked to stem cell population maintenance, response to fibroblast growth factor, and cell growth (Fig. 4J). The downregulated target genes were associated with epithelium development, regulation of the BMP and RA receptor signaling pathways, and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 4J). Specifically, TCF7 bound to loci near pluripotency genes (NANOG, SOX2, and DPPA4), which were silenced during SE differentiation, and to loci close to SE genes (TFAP2C, GRHL3, and GATA3), which were activated as differentiation progressed (Fig. 4K). Taken together, these results indicate that TCF7, acting as a downstream effector of RA, promotes hESC to exit pluripotency and drives SE differentiation.

MSX2 regulates SE commitment via opening chromatin and mediating SE gene expression

To further decipher the downstream mechanisms by which TCF7 mediates SE commitment, we identified its potential downstream mediators. We screened the top 10 TFs that were bound by TCF7 and significantly affected by its depletion (Fig. 5A). Among these, MSX2 attracted our attention and was chosen for further investigation to explore its role in SE initiation (Fig. 5B). We first examined the expression of MSX2 during SE initiation and observed that MSX2 was absent in hESCs and on the first day of differentiation (Fig. 5C). Its expression remained relatively low on day 2 and underwent a substantial increase during the SE initiation stage (Fig. 5C). Focusing on understanding the role of MSX2 in SE commitment, we knocked down MSX2 and found that MSX2-knockdown differentiated cells exhibited a phenotype resembling that of TCF7-knockdown cells (Fig. 5D). These cells maintained hESC clonal morphology, failed to acquire an epithelial-like morphology, and had undetectable SE marker KRT18 and SE maturation gene TP63 (Fig. 5D, E). Additionally, the loss of MSX2 remarkably suppressed the activation of SE-specific keratins (KRT7, KRT8, KRT18, and KRT19) and SE regulators (GRHL2, GRHL3, TFAP2A, TFAP2C, and GATA3) (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). GSEA showed that loss of MSX2 decreased the expression of Cluster III and IV genes enriched in SE (Fig. 5F and Supplementary Fig. 3C). In contrast, Cluster I genes, which are highly expressed in hESCs, were upregulated when MSX2 was knocked down (Supplementary Fig. 3D). These results indicate that MSX2 is required to mediate SE initiation. Interestingly, despite MSX2 being a downstream target of BMP4 signaling, perturbing MSX2 expression inhibited the expression of BMP4 and its downstream target genes (GRHL3, GATA3, ID2, MSX1, DLX5, and DLX6) (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. 3A-B). Furthermore, transcriptome changes occurring upon loss of BMP4 and MSX2 were highly similar, demonstrating a positive feedback regulatory loop between MSX2 and BMP4 (Fig. 5G and Supplementary Fig. 3E).

Fig. 5.

MSX2 opens chromatin and activates SE gene expression. A Volcano map of differentially expressed genes of shTCF7- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. The candidate downstream activators of TCF7 are highlighted in dark blue text. B Genome browser view of indicated ChIP-seq and RNA-seq signal across MSX2 loci. C Immunostaining of MSX2 during the first three days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. D Phase contrast images and immunostaining for KRT18 and TP63 in scrambled shRNA- and shMSX2-treated hESCs after three or seven days of differentiation. Scale bar, 100 μm. E Heatmap of expression of represented genes in scrambled shRNA- and shMSX2-treated hESCs after three or seven days of differentiation. F GSEA for Cluster III and IV genes in the gene expression matrix of shMSX2- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after seven days of differentiation. G GSEA for downregulated genes upon BMP4 knockdown in the gene expression matrix of shMSX2- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three or seven days of differentiation. H Pie chart showing the distribution patterns of MSX2 peaks in the differentiated cells on D3. I Heatmaps of binding signals of H3K4me1, H3K27ac, H3K4me3 and ATAC-seq at the center of MSX2 peaks in hESCs and the D3-differentiated cells. J Enrichment of TF motifs identified by HOMER at MSX2 peaks. K Heatmaps of binding signals of GRHL3, GRHL2, TFAP2C, and GATA3 at the center of MSX2 peaks. L Pie chart of the percentages of downregulated genes induced by MSX2 knockdown with or without MSX2 binding in D3-differentiated cells. M GO (biological process) analysis of the target genes of MSX2. N Left panel: Scatterplot of differential accessibility in shMSX2- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three days of differentiation. Sites identified as significant differential accessibility are shown in color (red, peaks increased; blue, peaks decreased). Right panel: TF motif enrichment in the regions of differential accessibility in shMSX2- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three days of differentiation. O Metaplots of average ATAC-seq density around the MSX2 target genes in shMSX2- and scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three days of differentiation. P Genome browser view of MSX2, ATAC-seq and RNA-seq signal across MSX2, TFAP2C, GRHL3, and KRT8/18 loci

Next, we sought to dissect the contribution of MSX2 in SE initiation and performed ChIP-seq to identify genome-wide binding sites of MSX2. Distribution analysis demonstrated that MSX2 binding sites were predominantly located in intergenic and intronic regions distant from the transcription start site of the target genes (Fig. 5H and Supplementary Fig. 3F). Combining this with epigenetic maps, we showed that MSX2 binding sites in SE-initiating cells had increased chromatin accessibility and higher enrichment of active histone marks (H3K27ac and H3K4me1) compared with those in hESCs, implying that MSX2 predominantly occupied enhancers to activate gene transcription during SE initiation (Fig. 5I). This was validated by gene expression analysis, which exhibited significantly higher expression levels of MSX2 target genes in SE-initiating cells compared with those in hESCs (Supplementary Fig. 3G). Furthermore, TF motif enrichment analysis revealed significant co-enrichment of motifs for SE regulators (GATA3, TFAP2A, TFAP2C, and GRHL2) at MSX2 binding sites (Fig. 5J). Notably, integrating the ChIP-seq data of MSX2 with previously published SE regulator (GATA3, TFAP2A, TFAP2C, GRHL2, and GRHL3) ChIP-seq data [26], we found frequent co-binding of MSX2 and SE regulators (Fig. 5K). These findings suggest that MSX2 may cooperate with these factors to regulate SE lineage gene expression and SE commitment. Moreover, by integrating MSX2 ChIP-seq and transcriptome data, we observed that most genes downregulated upon MSX2 knockdown (61%) exhibited MSX2 binding, and these MSX2 target genes were enriched in GO terms associated with pan-epithelial development processes, such as morphogenesis, proliferation, migration, cell junction assembly, and response to BMP, indicating that MSX2 mediated SE differentiation mainly through direct binding (Fig. 5L, M).

To further investigate the mechanisms mediating the effects of MSX2 in SE commitment, we performed genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiling by ATAC-seq. Notably, substantial changes in chromatin accessibility was observed upon MSX2 knockdown (Fig. 5N). Among differentially accessible regions, 93.3% of the loci showed a significant decrease in chromatin accessibility in MSX2-knockdown cells (compared with those in the control cells) and were enriched for motifs of well-known SE regulators, including TFAP2C, TFAP2A, GRHL2, and GATA3. However, only 6.7% of the loci showed a significant increase in chromatin accessibility and were enriched for motifs of core pluripotent factors, including NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2. This suggests a critical role of MSX2 in shaping the SE lineage-specific chromatin accessibility landscape during SE commitment (Fig. 5N). Furthermore, MSX2 knockdown substantially inhibited the opening chromatin accessibility around its target gene loci (Fig. 5O). Specifically, MSX2 bound to loci near itself, SE regulators (TFAP2C and GRHL3), and SE markers (KRT8 and KRT18), opening their chromatin accessibility and activating gene transcription, whereas upon knockdown of MSX2, their chromatin accessibilities were notably interfered, and their gene expression was remarkedly suppressed (Fig. 5P). Collectively, these results demonstrate that MSX2 regulates SE initiation by remodeling nuclear architecture to activate SE lineage-specific genes.

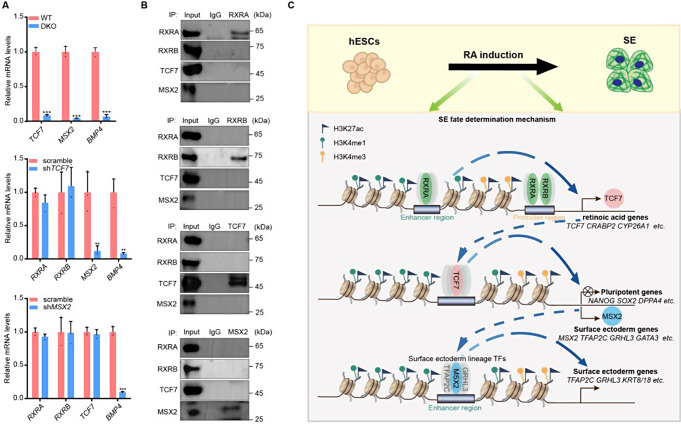

The regulatory hierarchy of RXRA/B, TCF7, and MSX2 in SE lineage regulatory networks

To accurately clarify the regulatory hierarchy among RXRA/B, TCF7, and MSX2 during SE fate determination, we silenced each gene individually and assessed its effect on the expression of the other two genes and BMP4. We found that RXRA/B DKO significantly suppressed the activation of TCF7, MSX2, and BMP4; loss of TCF7 significantly inhibited the expression of MSX2 and BMP4 but did not affect RXRA/B expression; and the absence of MSX2 suppressed BMP4 expression, but had no effect on RXRA/B and TCF7 expression (Fig. 6A). These results establish a regulatory hierarchy governing SE commitment, positioning RXRA/B at the top, followed sequentially by TCF7, MSX2, and BMP4. We next conducted co-immunoprecipitation to further define the roles of these regulators in the RXRA/B-TCF7-MSX2 regulatory network and observed no physical interaction between RXRA/B, TCF7, and MSX2 (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results demonstrated that RXRA/B, TCF7, and MSX2 control SE commitment by forming the RXRA/B-TCF7-MSX2 regulatory axis (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

The hierarchical regulation of RXRA/B, TCF7, and MSX2 during SE commitment. A qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes in the differentiated cells on D3. Top panel, WT and DKO hESCs after three days of differentiation; Middle panel, shTCF7- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three days of differentiation; Bottom panel, shMSX2- versus scrambled shRNA-treated hESCs after three days of differentiation. qRT-PCR values were normalized to the values in control group. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 t test). B Co-immunoprecipitation analysis of the interactions among endogenous RXRA, RXRB, TCF7, and MSX2 in the differentiated cells on D3. C The graphical summary of the function and mechanism of the RXRA/B-TCF7-MSX2 regulatory axis in RA-driven SE commitment

Discussion

The development of the SE is a vital process in vertebrate embryogenesis, giving rise to the formation of essential ectodermal appendages such as the epidermis, corneal, conjunctival, and oral epithelium as well as mammary glands and, hair follicles [17–21]. Abnormalities in SE development can lead to severe defects or diseases, impacting the formation and function of ectodermal appendages. For instance, disruptions in the ectodysplasin pathway can cause dysplasia of the skin, hair, teeth, and sweat glands [29–31]. Defects in the BMP and WNT pathways during SE development can result in impaired ocular morphogenesis [32, 33]. Additionally, mutations or dysfunctions in SE lineage-specific regulators GRHL2 and TFAP2A perturb ectodermal development, resulting in autosomal-recessive ectodermal dysplasia syndrome and craniofacial malformation, respectively [34, 35]. Thus, dissecting morphogen-signaling regulatory networks and identifying SE lineage-determining TFs holds paramount importance in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. Here, we introduced a novel SE differentiation system to elucidate the role of RA signaling in driving the specification of the SE lineage. We found that RA alone is sufficient to induce a SE phenotype and elucidated how the RXRA/B-TCF7-MSX2 axis bridges RA and BMP4 signalings with SE regulatory networks in determining SE fate (Fig. 6C). Our study offers an integrated paradigm for signaling pathways, epigenetics and transcriptional mechanisms for SE lineage determination, provides insights into the pathogenesis of ectodermal dysplasia and contributes to potential therapeutic targets for treatment of disorders related to ectodermal dysplasia.

RA plays a crucial role in the fate determination of various lineages, with its developmental functions being highly dependent on its concentration, duration, and cellular context. Different RA concentrations stringently regulate neuralization and positional specification [36]. However, improper duration and dosage of RA exposure in vertebrate embryos can lead to teratogenic effects [37–39]. A comprehensive understanding of RA’s functions and precise regulatory mechanisms in specific developmental processes could provide valuable insights into its role in development and guide its therapeutic use in regenerative medicine. Previous research has demonstrated that the morphogens RA and BMP4 synergistically direct SE development. Combined treatment of hESCs with RA and BMP4 yields a homogeneous population of SE cells [15, 16, 26]. RA is thought to promote an epithelial state, while BMP4 prompts SE differentiation and inhibits neural differentiation [40]. However, the precise mechanism by which these two signals integrate to coordinate SE fate specification remains unclear. In this study, we found that efficient SE differentiation could be achieved with RA stimulation alone. We observed that BMP4 signaling is activated during RA-driven SE differentiation, and that the loss of BMP4 significantly interferes with SE fate progression, indicating that BMP4 is an essential signal required for the regulation of SE fate downstream of RA. In addition to the RA and BMP4 pathways, WNT and FGF signaling have also been reported to be involved in SE fate determination [9]. Lateral epiblast cells express FGF and WNT, with WNT signaling blocking the response of epiblast cells to FGF, enabling BMP expression, which promotes SE fate and represses neural fate [9]. The details of how RA, BMP4, WNT, and FGF pathways cross-talk and integrate SE lineage-specific regulatory networks remain an interesting area for future studies.

We found that knockout of either RXRA or RXRB in hESCs resulted in delayed SE initiation without affecting ultimate SE commitment. However, RXRA/B DKO resulted in a complete block of SE fate determination. The common target genes of RXRA and RXRB were remarkedly associated with epithelium development and RA metabolism. These findings reveal redundant functions between RXRA and RXRB in driving SE commitment. Mechanically, RXRA/B directly mediate H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 histone modifications at SE lineage and RA response gene loci, positively modulating their expression. This aligns with previous observations that RA nuclear receptors mediate gene transcription by altering epigenetic landscape involved in lineage commitment [41–45]. It has been shown that, upon binding of RA, nucleic receptors recruit co-activators and activate chromatin remodelers, such as steroid receptor co-activators (SRC) and the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) p300/CBP, to RA response elements [41–44]. These findings prompt further investigation into the precise mechanisms underlying the interacting co-activators and chromatin remodelers with RXRA/B in regulating epigenetic remodeling, thereby influencing gene transcription. Additionally, in the classical model of RA signaling, RXRs modulate gene transcription as a heterodimer complex with RARs at RA response elements. Thus, identifying the RARs that interact with RXRA/B could facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the RA-driven SE commitment process.

Previous studies have reported important roles of TCF7, mainly focusing on T-lymphocyte differentiation [46]. TCF7 forms a complex with beta-catenin and activates transcription through canonical WNT signaling during T-lymphocyte development [47]. However, TCF7 also plays distinct roles in different biological processes. Through integrated analysis of the epigenomic and transcriptomic changes mediated by RXRA/B, along with RXRA/B ChIP-seq data, we identified TCF7 as a downstream effector of RXRA/B during RA-driven SE differentiation. TCF7 is rapidly expressed after RA induction but its expression is terminated when RXRA/B are knocked out. TCF7 depletion leads to defects in pluripotency exit and SE initiation owing to deregulation of the activation of SE genes and silencing of pluripotent genes. These observations demonstrate that TCF7 mediates RA signaling transduction and controls the switch from pluripotency to differentiation during SE commitment.

MSX2 is a recognized downstream mediator of BMP4, modulating gene transcription by interacting with TFs or chromatin regulators. Previous reports have demonstrated that MSX2 is involved in many developmental processes and can drive placenta, mesendoderm, and mesenchymal stem/stromal cell development [48–50]. Here, we identified MSX2 as a novel regulator of SE initiation from the downstream target genes of TCF7. Notably, we found that MSX2 depletion impedes SE commitment and significantly decreases BMP4 expression and signaling, revealing a positive feedback loop between MSX2 and BMP4 during SE commitment. Moreover, MSX2 binding leads to nucleosome displacement, enrichment of activating histone modification (H3K4me1 and H3K27ac), and higher transcriptional activity, indicating that MSX2 functions as a transcriptional activator to promote SE gene transcription during SE commitment. We also observed that MSX2 plays a role in altering the chromatin environment and mediates the opening of chromatin regions containing transcriptional regulatory elements bound by SE regulators such as TFAP2C, GRHL2, GRHL3, and GATA3. Additionally, upon reanalyzing our previously published ChIP-seq data for SE regulators (TFAP2C, GRHL2, GRHL3, and GATA3) in SE-initiating cells [26] alongside MSX2 ChIP-seq data, we found that these SE regulators exhibit a correlative binding pattern with MSX2. Therefore, it will be highly interesting to further elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying the interactions of MSX2 with these SE regulators and chromatin remodelers, such as SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex members, in future studies.

Materials and methods

Human ESC culture

H1 hESCs (XY) and genome-edited cell lines were cultured in pluripotency growth media (mTeSR1) (STEMCELL Technologies) on hESC-Qualified Matrix (Corning). The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2, passaged every 4–5 days with gentle cell dissociation reagent (STEMCELL Technologies), and routinely screened for mycoplasma.

In vitro induction of hESCs into keratinocytes

For surface epithelium differentiation, H1 hESCs were digested into colonies of 100–200 μm diameter using cell dissociation reagent (STEMCELL Technologies) and seeded on Matrigel-matrix-coated plates. The next day, hESCs were treated with 1 µM retinoic acid (R&D Systems) in mTeSR1 medium for 7 days. The differentiation media was replaced every 2 days. For keratinocyte maturation, SE derived from hESCs were cultured in Defined Keratinocyte-SFM medium (DKSFM, GIBCO) supplemented with 10 ng/ml FGF2 (R&D Systems) and 10 ng/ml EGF (Millipore) for 60 days. The culture media was replaced every day.

Calcium induced keratinocytes differentiation

To mimic the differentiation process of keratinocytes in vitro, keratinocytes derived from hESCs were culture to reach full confluence, and then were treated with 1.2 mM CaCl2 in DKSFM medium for 7 days. The differentiation media was replaced every day.

Generating gene knockout cell line using CRISPR-Cas9 system

We generated gene knockout hESC cell lines using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) oligos targeting the indicated genes were designed using an online gRNA design tool (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/) and were cloned into LentiCRISPRv2 plasmid for gRNA production. H1 hESCs were infected with gRNA lentivirus and selected with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for 2 days. The remaining viable clones were digested into single cells using accutase (STEMCELL Technologies) and cultured in mTeSR1 medium supplemented with the Rho-associated protein kinases inhibitor Y-27,632 (Tocris). The knockout clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and western blotting analysis. The sequences of gRNAs used in this paper are listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Generating gene knockdown cell line using short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

shRNAs targeting TCF7, BMP4, or MSX2 were designed using the Merck online tool and subcloned into the pLKO.1 plasmid. A nontargeting scrambled shRNA was used as a negative control. Two target-specific shRNAs were designed for each gene and used separately. For knockdown experiments, lentivirus particles were prepared by transfecting HEK293T cells with pLKO.1-shRNA vectors along with the packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G. hESCs were infected with lentivirus particles encoding target-specific shRNAs for 24 h in fresh mTeSR1 containing 8 µg/mL polybrene, followed by selection with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for 48 h. The sequences of shRNAs used in this paper are listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with MolPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Kit (Yeasen) and reverse transcribed using PrimeScript RT Master Mix Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix Kit (BioRad) on a realtime detection system. The PCR program consisted of an denaturation for 3 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of PCR (95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as the internal control for normalization. The primers used in this paper are listed in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

Protein extraction and western blotting

Proteins in cells were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (0.5% SDS, 1% IGEPAL CA6300, 5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF). Proteins were electrophoresed on a FastPAGE Precast Gel (Tsingke), and the separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (Tris-buffered Saline, 0.1% Tween-20). The membrane was incubated with primary antibody at 4℃ overnight and secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The proteins were detected using an ECL detection kit (FUDE BioTech) and imaged using a chemiluminescence detection system. The antibodies used for western blotting are as follows: anti-RXRA (Abcam, ab125001, 1:2000), anti-RXRB (Cell Signaling, 8715 S, 1:2000), anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, 5174 S, 1:2000).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed using an immunoprecipitation kit (Proteintech) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were collected and resuspended in IP lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors for 30 min on ice, gently inverting the mixture every 10 min. Protein lysates were incubated with primary antibodies and incubation buffer overnight at 4 °C with rotation, followed by incubation with rProtein A/G beads at 4 °C for 3 h. The protein-bead complexes were washed four times using washing buffer and eluted from beads in Elution buffer. The elution fractions were denatured by adding of 1× loading buffer and subsequently used for western blotting with the following antibodies: anti-RXRA (Abcam, ab125001), anti-RXRB (Cell Signaling, 8715 S), anti-TCF7 (Cell Signaling, 2203 S), and anti-MSX2 (Sigma, HPA005652).

Immunofluorescence staining (IF)

Cells growing on plated were washed briefly twice with cold PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and subsequently permeabilized and blocked with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times with PBS prior to incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After three washes in PBS, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, images were acquired using a Leica microscope. The primary antibodies used for IF are as follows: anti-KRT18 (Invitrogen, MA5-12104; 1:500), anti-KRT7 (Cell Signaling, 4465 S; 1:500), anti-KRT14 (Invitrogen, MA5-11599, 1:500), anti-KRT1 (Santa Cruz, SC-376224, 1:1000), anti-KRT10 (Invitrogen, MA1-06319, 1:1000), anti-TP63 (Cell Signaling, 67825 S, 1:500), anti-NANOG (GeneTex, GTX100863; 1:500), anti-TCF7 (Cell Signaling, 2203 S, 1:500), anti-BMP4 (Abcam, ab124715, 1:500), anti-MSX2 (Sigma, HPA005652, 1:500) and anti-pSMAD1/5/8 (Cell Signaling, 13820 S, 1:500). The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated (Cell Signaling, 1:1000).

RNA-seq and data analysis

RNA-seq libraries were prepared using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit (Illumina) following manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed on a NovaSeq 6000 Platform (Illumina) using 150 base pairs (bp) paired-end reads. For RNA-seq data analysis, raw reads were quality- and adaptor-trimmed using trimmomatic-0.39 tools [51] prior to alignment. The trimmed reads were aligned to human hg19 reference genome using STAR-2.6.1 software [52] and quantified using RSEM-1.3.053. Differentially expressed genes were determined using DESeq2-1.20.0 R package with q-value ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 as the cutoff [54]. Gene ontology analysis was performed using Clusterprofiler R package with qvalueCutoff ≤ 0.0555. GSEA was performed using javaGSEA desktop application from Broad institute with weighted enrichment statistic and signal2noise ranking metric [56]. The RNA-seq data were from two biological samples.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq assays were performed as previously described [26]. Briefly, adherent cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and then neutralized with DMEM containing 10% FBS. After being washed with cold PBS, 60,000 cells were collected and incubated in ice-cold lysis buffer (0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.1% Tween-20, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) for 5 min. Immediately after lysis, nuclei were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove the supernatant. Nuclei were then washed with cold PBS, resuspended in transposase reaction mix (Vazyme Biotech, TD501), and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The transposed fragments were isolated using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN), and PCR amplification was carried out using the TruePrep DNA Library Prep Kit (Vazyme Biotech, TD501) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the ATAC-seq library were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (Illumina).

ChIP-seq

ChIP-seq assays were performed as previously described [26]. Briefly, cells were harvested and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28906) for 10 min at room temperature. Crosslinking was then quenched by incubating with 125 mM Glycine (Sigma, 50046) for 5 min at room temperature. After washing with cold PBS, cells were lysed in sonication buffer (0.1% SDS, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA). The chromatin DNA was fragmented with ultrasonicator (Covaris M220) to generate fragments of 200 ~ 500 bp. Then, the chromatin was incubated with indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4℃ and then addition of Protein A/ G magnetic beads (1:1, Invitrogen) to capture the immunocomplexes. The beads were sequentially washed three times with sonication buffer, twice with low-salt wash buffer (0.5% NP40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 250 mM LiCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 1 mM EDTA), and once with TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 1 mM EDTA). The immunoprecipitated complex was eluted from beads and decross-linked with elution buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA) at 65 °C for 4 h, followed by treatment with proteinase K (Invitrogen) and ribonuclease A (Invitrogen) at 55 °C for 1 h. Finally, the DNA was purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). ChIP-seq libraries were constructed using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, KK8502) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (Illumina) using 150 bp paired-end reads. Antibodies used for ChIP-seq are as follows: H3K4me1 (Active Motif, 39297), H3K4me3 (Cell Signaling, 9751 S), H3K27ac (Millipore, 07-360), H3K27me3 (Cell Signaling, 9733 S), RXRA (Abcam, ab125001), TCF7 (Cell Signaling, 2203), MSX2 (Sigma, HPA005652) and FLAG (Cell Signaling, 14793 S). For RXRB ChIP-seq, FLAG-RXRB-expressing vector was constructed and used to capture RXRB-bound chromatin fragments.

Data analysis of ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq

ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data were analyzed as previously described [26]. Briefly, raw reads were quality- and adaptor-trimmed using trimmomatic-0.39 tools [51], prior to alignment. The trimmed reads were aligned to human hg19 reference genome using BWA-0.7.17 software [57], followed by removal of PCR duplicates using Picard tools-2.18.16 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq peak calling were performed using MACS2-2.1.158. For broad histone marks (H3K4me1 and H3K27me3), peaks were called with options “--fix-bimodal --extsize 500 --broad --broad-cutoff 0.01”. For narrow histone marks and TF ChIP-seq, peaks were called using the following options “--call-summits --fix-bimodal --extsize 200 -q 0.001”. For ATAC-seq peaks, we used the following parameters: “--nomodel --shift − 100 --call-summits --extsize 200 --q 0.001”. The overlapping peaks between two biological replicates were identified by Homer mergePeaks program [59]. The resulting bedGraph files generated from MACS2 were converted to bigwig files using deepTools bamCoverage program [60] for visualization in Integrative Genomics Viewer [60]. Average profiles and heatmaps for ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data were plotted using deepTools 3.0.260. The ChIPseeker package [61] was used for Peak distributions analysis, and the HOMER’s annotatePeaks.pl program [59] was employed for peak annotation. TF motif enrichment analysis was performed using the HOMER findMotifsGenome program [59]. Differential ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq peaks were identified using DiffBind R package with FDR ≤ 0.05 as the cutoff [62]. Chromatin state annotations were generated using ChromHMM-1.1063.

Statistical analyses

Statistical measurements were conducted using GraphPad Prism v6.0. Statistical significance between two groups were evaluated using Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-tailed). All error bars were calculated in GraphPad Prism v6.0 and data were presented as the means ± SD. In all experiments, the n value represents the number of independently performed experiments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Nan Cao for sharing H1 human embryonic stem cells.

Author contributions

H.O. and Z.M. conceived and guided this project and contributed to writing. H.H. designed and performed experiments and bioinformatics analyses, and wrote the manuscript. J.L. and F.A. performed the cellular and molecular biology experiments and contributed to experimental design. S.W. performed cell culture. M.L. and L.W. provided comments and supervised the manuscript. H.G., B.W., K.M., Y.H., J.T., J.Z., Z.L., Z.H. and L.W. helped the experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 82271043), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (NO. 2023A1515012719), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (NO. 2023M734023).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supporting Information. Other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The accession number for the publicly available RNA-seq data used in this paper is GEO: GSE97213 and GSE270184.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors declare their consent for this publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Hong Ouyang Lead Contact.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huaxing Huang, Jiafeng Liu and Fengjiao An contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhen Mao, Email: ophmaozhen@gmail.com.

Hong Ouyang, Email: Ouyhong3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kicheva A, Briscoe J (2023) Control of tissue development by Morphogens. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-020823-011522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camacho-Aguilar E, Warmflash A (2020) Insights into mammalian morphogen dynamics from embryonic stem cell systems. Curr Top Dev Biol 137:279–305. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagner A, Briscoe J (2019) Establishing neuronal diversity in the spinal cord: a time and a place. Development 146. 10.1242/dev.182154 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rogers KW, Schier AF (2011) Morphogen gradients: from generation to interpretation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27:377–407. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sagner A, Briscoe J (2017) Morphogen interpretation: concentration, time, competence, and signaling dynamics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 6. 10.1002/wdev.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rifes P, Isaksson M, Rathore GS, Aldrin-Kirk P, Moller OK, Barzaghi G, Lee J, Egerod KL, Rausch DM, Parmar M et al (2020) Modeling neural tube development by differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in a microfluidic WNT gradient. Nat Biotechnol 38:1265–1273. 10.1038/s41587-020-0525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu RH, Chen X, Li DS, Li R, Addicks GC, Glennon C, Zwaka TP, Thomson JA (2002) BMP4 initiates human embryonic stem cell differentiation to trophoblast. Nat Biotechnol 20:1261–1264. 10.1038/nbt761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang P, Li J, Tan Z, Wang C, Liu T, Chen L, Yong J, Jiang W, Sun X, Du L et al (2008) Short-term BMP-4 treatment initiates mesoderm induction in human embryonic stem cells. Blood 111:1933–1941. 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson SI, Rydstrom A, Trimborn T, Willert K, Nusse R, Jessell TM, Edlund T (2001) The status of wnt signalling regulates neural and epidermal fates in the chick embryo. Nature 411:325–330. 10.1038/35077115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham TJ, Duester G (2015) Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16:110–123. 10.1038/nrm3932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghyselinck NB, Duester G (2019) Retinoic acid signaling pathways. Development 146. 10.1242/dev.167502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gudas LJ, Wagner JA (2011) Retinoids regulate stem cell differentiation. J Cell Physiol 226:322–330. 10.1002/jcp.22417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM (1995) The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell 83:841–850. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens DW, Lane EB (2003) The quest for the function of simple epithelial keratins. BioEssays 25:748–758. 10.1002/bies.10316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattison JM, Melo SP, Piekos SN, Torkelson JL, Bashkirova E, Mumbach MR, Rajasingh C, Zhen HH, Li L, Liaw E et al (2018) Retinoic acid and BMP4 cooperate with p63 to alter chromatin dynamics during surface epithelial commitment. Nat Genet 50:1658–1665. 10.1038/s41588-018-0263-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Wang Y, Torkelson JL, Shankar G, Pattison JM, Zhen HH, Fang F, Duren Z, Xin J, Gaddam S et al (2019) TFAP2C- and p63-Dependent networks sequentially rearrange chromatin landscapes to drive human epidermal lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell 24:271–284e278. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Girolamo N, Park M (2023) Cell identity changes in ocular surface Epithelia. Prog Retin Eye Res 95:101148. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lwigale PY (2015) Corneal development: different cells from a common progenitor. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 134:43–59. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collomb E, Yang Y, Foriel S, Cadau S, Pearton DJ, Dhouailly D (2013) The corneal epithelium and lens develop independently from a common pool of precursors. Dev Dyn 242:401–413. 10.1002/dvdy.23925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones KB, Klein OD (2013) Oral epithelial stem cells in tissue maintenance and disease: the first steps in a long journey. Int J Oral Sci 5:121–129. 10.1038/ijos.2013.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biggs LC, Mikkola ML (2014) Early inductive events in ectodermal appendage morphogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 25–26:11–21. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koster MI, Roop DR (2007) Mechanisms regulating epithelial stratification. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23:93–113. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan X, Wang D, Burgmaier JE, Teng Y, Romano RA, Sinha S, Yi R (2018) Single cell and open chromatin analysis reveals molecular origin of epidermal cells of the skin. Dev Cell 47:133. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez CG, Teixeira FK, Czech B, Preall JB, Zamparini AL, Seifert JR, Malone CD, Hannon GJ, Lehmann R (2016) Regulation of Ribosome Biogenesis and protein synthesis controls germline stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 18:276–290. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buszczak M, Signer RA, Morrison SJ (2014) Cellular differences in protein synthesis regulate tissue homeostasis. Cell 159:242–251. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H, Liu J, Li M, Guo H, Zhu J, Zhu L, Wu S, Mo K, Huang Y, Tan J et al (2022) Cis-regulatory chromatin loops analysis identifies GRHL3 as a master regulator of surface epithelium commitment. Sci Adv 8:eabo5668. 10.1126/sciadv.abo5668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Adli M, Zou JY, Verstappen G, Coyne M, Zhang X, Durham T, Miri M, Deshpande V, De Jager PL et al (2013) Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell 152:642–654. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natoli G (2010) Maintaining cell identity through global control of genomic organization. Immunity 33:12–24. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu K, Huang C, Wan F, Jiang C, Chen J, Li X, Wang F, Wu J, Lei M, Wu Y (2023) Structural insights into pathogenic mechanism of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia caused by ectodysplasin A variants. Nat Commun 14. 10.1038/s41467-023-36367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Kowalczyk-Quintas C, Schneider P (2014) Ectodysplasin A (EDA) - EDA receptor signalling and its pharmacological modulation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 25:195–203. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itin PH (2014) Etiology and pathogenesis of ectodermal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet A 164A:2472–2477. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuta Y, Hogan BL (1998) BMP4 is essential for lens induction in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev 12:3764–3775. 10.1101/gad.12.23.3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter AC, Smith AN, Wagner H, Cohen-Tayar Y, Rao S, Wallace V, Ashery-Padan R, Lang RA (2015) Wnt ligands from the embryonic surface ectoderm regulate ‘bimetallic strip’ optic cup morphogenesis in mouse. Development 142:972–982. 10.1242/dev.120022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Otterloo E, Milanda I, Pike H, Thompson JA, Li H, Jones KL, Williams T (2022) AP-2alpha and AP-2beta cooperatively function in the craniofacial surface ectoderm to regulate chromatin and gene expression dynamics during facial development. Elife 11. 10.7554/eLife.70511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Petrof G, Nanda A, Howden J, Takeichi T, McMillan JR, Aristodemou S, Ozoemena L, Liu L, South AP, Pourreyron C et al (2014) Mutations in GRHL2 result in an autosomal-recessive ectodermal dysplasia syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 95:308–314. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada Y, Shimazaki T, Sobue G, Okano H (2004) Retinoic-acid-concentration-dependent acquisition of neural cell identity during in vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol 275:124–142. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maden M (1982) Vitamin A and pattern formation in the regenerating limb. Nature 295:672–675. 10.1038/295672a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kochhar DM (1973) Limb development in mouse embryos. I. Analysis of teratogenic effects of retinoic acid. Teratology 7:289–298. 10.1002/tera.1420070310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tickle C, Alberts B, Wolpert L, Lee J (1982) Local application of retinoic acid to the limb bond mimics the action of the polarizing region. Nature 296:564–566. 10.1038/296564a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metallo CM, Ji L, de Pablo JJ, Palecek SP (2008) Retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein signaling synergize to efficiently direct epithelial differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 26:372–380. 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatagnon A, Veber P, Morin V, Bedo J, Triqueneaux G, Semon M, Laudet V, d’Alche-Buc F, Benoit G (2015) RAR/RXR binding dynamics distinguish pluripotency from differentiation associated cis-regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res 43:4833–4854. 10.1093/nar/gkv370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kashyap V, Gudas LJ (2010) Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms distinguish retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional responses in stem cells and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 285:14534–14548. 10.1074/jbc.M110.115345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urvalek AM, Gudas LJ (2014) Retinoic acid and histone deacetylases regulate epigenetic changes in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 289:19519–19530. 10.1074/jbc.M114.556555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillespie RF, Gudas LJ (2007) Retinoic acid receptor isotype specificity in F9 teratocarcinoma stem cells results from the differential recruitment of coregulators to retinoic response elements. J Biol Chem 282:33421–33434. 10.1074/jbc.M704845200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kashyap V, Laursen KB, Brenet F, Viale AJ, Scandura JM, Gudas LJ (2013) RARgamma is essential for retinoic acid induced chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation in embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci 126:999–1008. 10.1242/jcs.119701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raghu D, Xue HH, Mielke LA (2019) Control of lymphocyte fate, infection, and Tumor immunity by TCF-1. Trends Immunol 40:1149–1162. 10.1016/j.it.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeannet G, Boudousquie C, Gardiol N, Kang J, Huelsken J, Held W (2010) Essential role of the wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9777–9782. 10.1073/pnas.0914127107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Q, Zhang L, Su P, Lei X, Liu X, Wang H, Lu L, Bai Y, Xiong T, Li D et al (2015) MSX2 mediates entry of human pluripotent stem cells into mesendoderm by simultaneously suppressing SOX2 and activating NODAL signaling. Cell Res 25:1314–1332. 10.1038/cr.2015.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hornbachner R, Lackner A, Papuchova H, Haider S, Knofler M, Mechtler K, Latos PA (2021) MSX2 safeguards syncytiotrophoblast fate of human trophoblast stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. 10.1073/pnas.2105130118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Zhang L, Wang H, Liu C, Wu Q, Su P, Wu D, Guo J, Zhou W, Xu Y, Shi L, Zhou J (2018) MSX2 initiates and accelerates mesenchymal Stem/Stromal cell specification of hPSCs by regulating TWIST1 and PRAME. Stem Cell Rep 11:497–513. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR (2013) STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29:15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li B, Dewey CN (2011) RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of Fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY (2012) clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16:284–287. 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H, Durbin R (2010) Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26:589–595. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS (2008) Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9:R137. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK (2010) Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38:576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramirez F, Ryan DP, Gruning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dundar F, Manke T (2016) deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W160–165. 10.1093/nar/gkw257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen TW, Li HP, Lee CC, Gan RC, Huang PJ, Wu TH, Lee CY, Chang YF, Tang P (2014) ChIPseek, a web-based analysis tool for ChIP data. BMC Genomics 15. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Wu DY, Bittencourt D, Stallcup MR, Siegmund KD (2015) Identifying differential transcription factor binding in ChIP-seq. Front Genet 6:169. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ernst J, Kellis M (2017) Chromatin-state discovery and genome annotation with ChromHMM. Nat Protoc 12:2478–2492. 10.1038/nprot.2017.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supporting Information. Other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The accession number for the publicly available RNA-seq data used in this paper is GEO: GSE97213 and GSE270184.