Abstract

Objective

IgA vasculitis (IgAV) is the most frequently experienced subtype of vasculitis seen in children. Most children fully recover, however, complications including chronic kidney disease are recognised. The aim of this project was to use a best available evidence, group agreement, based approach to develop national recommendations for the initial management of IgAV and its associated complications.

Methods

A fully representative multiprofessional guideline development group (GDG), consisting of 28 members, was formed and met monthly. Graded recommendations were generated using nationally accredited methods, which included a predefined scope, open consultation, systematic literature review, evidence appraisal, review of national or international guidelines and a period of open consultation. Audit measures and research priorities were incorporated.

Results

The IgAV GDG met over a 14-month period. A total of 82 papers were relevant for evidence synthesis. For the initial management, four topic areas were identified with five key questions generating six graded recommendations related to classification, specialist referral and musculoskeletal involvement. For the associated complications, five topic areas with 12 key questions generated 15 graded recommendations covering nephritis, gastrointestinal and testicular involvement, atypical disease and follow-up. Open consultation feedback was incorporated. The guidelines were endorsed by the UK Kidney Association and Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and are available online.

Conclusion

Despite IgAV being a rare disease with limited evidence, a national standardised approach to the clinical management for children and young people has been achieved. This should unite approaches to care and act as a foundation for improvement.

Keywords: Child Health, Nephrology, Rheumatology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

A multiprofessional derived national guideline to align the care of IgA vasculitis for children and young people based on a best available evidence and group agreement structured approach.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

A unified approach to enable equity of care for children and young people with IgA vasculitis.

Nationally accredited guidance that can act as a framework for audit and evidence generation to improve future outcomes of this condition.

Introduction

IgA vasculitis is a rare disease, however it is the most frequently experienced subtype of vasculitis in children with an estimated annual incidence of 6.8 to 30 per 100 000 childhood population.1 2 Adult-onset disease is ultrarare with an estimated incidence of 0.8–1.8 per 100 000 adult population.3 It is classified as a small-vessel vasculitis characterised by IgA1-dominant immune deposits in the vasculature and affected tissues. The condition typically presents as a purpuric, symmetrical, non-blanching rash, predominating on the extensor surfaces of the lower limbs.4 5 It is associated mainly with skin involvement together with any of gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and/or renal involvement (termed IgAV nephritis, IgAVN).6 Overall, the disease is self-limiting in most children, however short-term morbidity related to abdominal involvement is seen and recurrent episodes are reported.7 In the longer term chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major consequence of this condition. The incidence of kidney failure in all children presenting with IgAV is consistently reported at 1%–2%,8 9 yet it is much higher at around 10% in adult-onset disease. In studies that capture children with biopsy-proven kidney disease, termed IgAV nephritis, the rates of CKD are much higher, especially in patients with poor prognostic features such as impaired baseline kidney function.10 Current treatment options for established nephritis rely on broad-spectrum immunosuppressive agents and randomised controlled trial data have shown that the prophylactic use of high-dose corticosteroids at disease onset in all patients does not reduce the risk of developing subsequent nephritis.11 12 A lack of a standardised approach to this disease promotes variability in patient care and is a barrier to improving outcomes. Furthermore, the rarity of the disease in the adult population means that extrapolation of evidence has not been feasible. In 2019, an international European-wide collaborative effort—called the Single Hub and Access point for paediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE) initiative—provided a milestone in advancing this condition internationally.13

The aim of this project was to use a best available evidence, group agreement, based approach to create national recommendations for the initial management and associated complications of IgAV for children and young people in the United Kingdom.

Methods

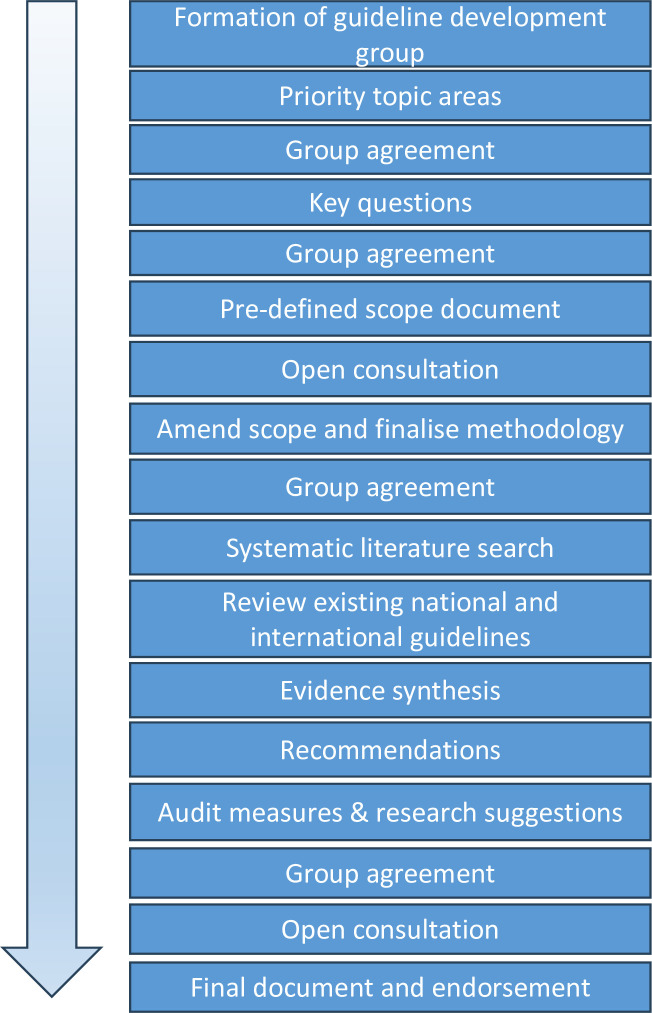

The methodological approach used a multiprofessional working group, topic areas with priority questions, a predefined scope and evidence synthesis to develop graded recommendations for IgAV (outlined in figure 1).

Figure 1. A summary of the methodology used to generate recommendations for a rare disease using a best available evidence and group agreement-based approach.

Establishing a multiprofessional working group

A multiprofessional guideline development group (termed the IgAV GDG) was established via the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) Research and Evidence team. Members were required to submit an expression of interest and declare any conflicts of interest. The methodology adhered to clinical guideline standards outlined by the RCPCH and the UK Kidney Association (National Institute of Clinical Excellence accredited) as a collaborative venture.

Developing the scope and key questions

The IgAV GDG defined the topic areas and key questions for the scope document (table 1). The scope included the population, setting, target audience, intended users and key clinical questions. The key questions provided a framework for the systematic literature review. The scope had a period of open consultation that included direct approach to multiple stakeholder groups (see online supplemental information). The IgAV GDG agreed to present the findings as two guidelines; one for the initial management of IgAV with the intended audience to be general practitioners and general paediatricians (termed guideline 1) and a second guideline for the management of complications associated with IgAV aimed for general paediatricians and paediatric subspecialists (termed guideline 2).

Table 1. Topic areas and key questions derived for the systematic review (taken from the UK Kidney Association99,100).

| Topic area | Questions for systematic review |

| Initial management (guideline 1) | |

| Classification of IgAV | In children and young people with IgAV under the age of 18 years, do classification tools allow professionals to classify IgAV from other clinical diseases to support diagnosis? |

| Outcome of initial assessment in IgAV | In children and young people with IgAV under the age of 18 years, are there clinical signs and symptoms that indicate urgent complications that require a referral to a specialist? |

| Nephritis screening in IgAV | In children and young people with IgAV under the age of 18 years, what are the best clinical tests to detect a diagnosis of nephritis? |

| Treatment of initial presentation of IgAV | In children and young people with IgAV under the age of 18 years, what are the clinical signs and symptoms that indicate the need for therapeutics to manage joint involvement and reduce symptom duration and/or severity? |

| In children and young people with IgAV under the age of 18 years, what are the clinical signs and symptoms that indicate the need for therapeutics to manage gastrointestinal involvement and reduce symptom duration and/or severity? | |

| Management of complications (guideline 2) | |

| IgAV associated nephritis | In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are the best investigations to confirm a clinical diagnosis of nephritis? |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are the best classification tools to grade a histological diagnosis of IgAV nephritis? | |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs, symptoms or investigations define nephritis that requires treatment to reduce the risk of chronic kidney disease? | |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are acceptable treatments for nephritis to reduce the risk of chronic kidney disease? | |

| IgAV associated gastrointestinal, urological involvement | In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are acceptable treatments for gastrointestinal bleeding that would reduce the duration and/or severity of symptoms? |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are acceptable treatments or interventions for the management of intussusception that would reduce the duration and/or severity of symptoms? | |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs, symptoms or investigations would support a diagnosis of testicular involvement that requires treatment? | |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what are acceptable treatments or interventions for the management of testicular involvement that would reduce the duration and/or severity of symptoms? | |

| IgAV associated skin involvement | In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs or symptoms would support for the need to perform a skin biopsy to support a diagnosis? |

| IgAV persisting, prolonged, recurrent disease | In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs or symptoms would support a diagnosis of persisting disease? |

| In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs or symptoms would support a diagnosis of recurrent disease? | |

| Long-term follow-up | In children and young people under the age of 18 years with IgAV, what clinical signs or symptoms would indicate the need for follow-up after initial screening to detect long-term complications? |

IgAVIgA vasculitis

Evidence synthesis

A systematic literature review was performed with predefined criteria. Questions about interventions were framed in Patient, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome format. The population were children and young people (aged <18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of IgAV. The intervention was a classification tool, monitoring or therapeuticmanagement. The comparison was any intervention compared with another. The outcome was related to the diagnosis, complications, duration or severity of symptoms. General concepts were used for the population (“pediatric”, “paediatric”, “child*”, “adolescen*”) and disease (“immunoglobulin A vasculitis”, “IgA vasculitis”, “IgAV”, “Henoch Schonlein purpura”, “HSP”). Concepts were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR and NOT).14 Three bibliographic databases were searched; Medline (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medline), Embase (https://www.embase.com) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central).15 The process was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of interventions.15 The results were merged, and duplicates were removed. The articles were independently screened and for full-text review according to the eligibility criteria (table 2). Two members synthesised the literature and discussed areas of disagreement. Searching of reference lists was permitted. An evidence table and a narrative summary were produced.

Table 2. Eligibility criteria for the literature search.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Publication date | Papers published between 2002 and 2022 | Papers published prior to 2002 |

| Research type | Primary research | Secondary research |

| Study type | Randomised controlled trials (RCT)If no RCT available to consider;Cohort studiesCase series>5 patientsCase–control studiesMeta-analysisSystematic reviews | Case reportsEditorialsCommentsAnnotationsLettersCommentariesBooks and book chaptersUpdated systematic reviews by same methodology, for example, Cochrane (most recent version will be included)Non-traditional therapies (eg, Chinese medicines) and surgical intervention |

| Publication and study status | PublishedCompleted | UnpublishedOngoing |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Text availability | Full text available | Full text unavailable |

Generation and grading of recommendations

During the process of achieving group agreement, discussions took into account existing clinical practice and national or international guidelines were evidence was limited or lacking. The modified Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used to evaluate the strength of the recommendation, with grade 1 being a strong recommendation (depicted by ‘we recommend’), and grade 2 being a weaker recommendation (depicted by ‘we suggest’). The quality of evidence was graded A–D with grade A being high-quality evidence, grade B moderate-quality, grade C low-quality evidence from observational studies, or controlled trials with very serious limitations, grade D evidence was generally case studies or expert opinion. Studies were downgraded if there was evidence of bias, indirectness, imprecision or inconsistency of results and the strength of the recommendation could be adjusted taking into context of the balance of benefit or harms to patients. The final draft underwent a period of 4 weeks of open consultation prior to final endorsement.

Results

A representative multiprofessional working group

The multiprofessional working group consisted of 28 members including two patient representatives, six general paediatric consultants, one general paediatric trainee, two paediatric surgeons, one paediatric pathologist, one radiologist, three adult nephrologists with expertise in vasculitis, one paediatric gastroenterology trainee, one paediatric emergency consultant, two general practitioners, one medical student, two paediatric rheumatologists, one paediatric gastroenterologist and four paediatric nephrologists. The IgAV GDG met monthly over a 14-month period.

Generation of the scope document and primary evidence

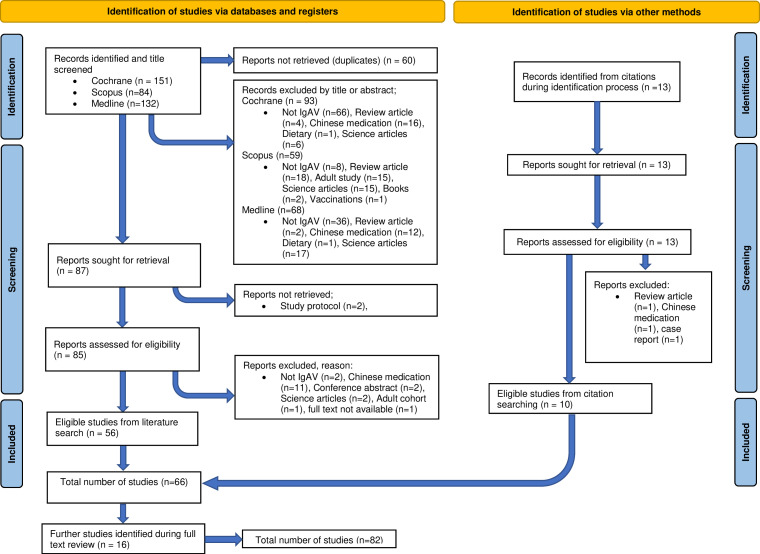

The scope document was distributed to stakeholders and open consultation and feedback was discussed in the monthly working group meeting on 21 January 2022. Following feedback, the GI key questions were united and placed into the complication’s guideline. The systematic literature search was completed on 11 March 2022 and 82 papers were identified. The screening process is illustrated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram (figure 2) and studies were divided according to topic areas. The initial management guideline had 66 relevant papers of which, 55 related to classification, 16 to specialist referral, 28 to nephritis and 8 to musculoskeletal involvement. The associated complication guideline had 82 relevant papers of which 33 were relevant to established nephritis, 23 to gastrointestinal or urological involvement, 3 to skin, 8 to persisting disease, 34 to recurrent disease and 22 for long-term follow-up. There were no cases of disagreement for inclusion of the papers and 33 papers were helpful for background information however they were ultimately not used to directly inform a recommendation.16,48

Figure 2. A PRISMA diagram to illustrate the selection of literature for the IgAV recommendations. IgAV, IgA vasculitis; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Recommendations and brief rationale

This article provides a brief summary of the underpinning rationale to support the recommendations (tables3 4). The guidelines are available on the UK Kidney Association website (https://ukkidney.org/renal-association/news/iga-vasculitis-guideline-rcpch-endorsed).

Table 3. The recommendations for the initial management of children and young people with IgA vasculitis (IgAV) as taken from The UK Kidney Association99.

| Number | Recommendation | Grade |

| Section 1: Classification of IgAV in clinically suspected disease | ||

| 1.1 | We recommend that professionals follow the EULAR/PRINTO/PRES 2010 classification criteria of IgAV. 49 | 1B |

| Section 2: Specialist referral in IgAV* | ||

| 2.1 |

We recommend that specialist advice should be sought for children and young people with IgAV and the following clinical presentations (and symptoms or signs):

|

1C |

| 2.2 |

We suggest that specialist advice should be sought for children and young people with IgAV and the following clinical presentations (and symptoms or signs):

|

2D |

| Section 3: Nephritis screening in IgAV | ||

| 3.1 | We recommend that children and young people should have urinalysis testing performed frequently over a period of 6 months to detect a diagnosis of nephritis (for example weekly screening for the first 4–6 weeks then monthly thereafter). | 1B |

| 3.2 | We suggest that blood pressure assessment should be performed in children and young people with IgAV at diagnosis and if there is evidence of nephritis. | 2C |

| Section 4: Musculoskeletal involvement in IgAV | ||

| 4.1 | We recommend appropriate analgesia and rest for musculoskeletal involvement in children and young people with IgAV. | 1C |

IgAVIgA vasculitisUP:UCurine protein to urine creatinine ratio

Table 4. The recommendations for the management of complications associated with IgA vasculitis (IgAV) in children and young people (taken from The UK Kidney Association100).

| Number | Recommendation | Grade |

| Section 1: Clinically suspected IgAV nephritis | ||

| 1.1 | We recommend that a kidney biopsy is undertaken to confirm a diagnosis of severe nephritis in children and young people with IgAV, where the definition of severe nephritis includes persisting severe proteinuria (UP: UC>250 mg/mmol for up to 4 weeks), persisting moderate proteinuria (UP: UC 100–250 mg/mmol for 3 months), AKI stage 1 or greater (at any time), or nephrotic syndrome (at any time; also see Section 2.2). | 1C |

| Section 2: Management of histologically proven IgAV nephritis | ||

| 2.1 | We recommend that the kidney histology should be classified using the ISKDC classification criteria for children and young people with IgAV. | 1C |

| 2.2 |

We recommend that a combination of clinical features and the histological ISKDC classification should guide decisions about treatment choices to offer children and young people with IgAV nephritis.The following are clinical indications;

|

1C |

| 2.3 | We suggest that the management of biopsy proven IgAV nephritis should be directed by, or in conjunction with, a paediatric nephrologist | 2B |

| 2.4 |

We suggest using the following disease-modifying drugs, or a combination of corticosteroids together with a disease-modifying drug, depending on the clinical and histological features in children and young people with biopsy proven IgAV nephritis.Corticosteroids;

|

2B |

| 2.5 | We suggest that in cases of IgAV nephritis with persisting proteinuria (UP: UC>100 mg/mmol for 3 months or UP: UC>50 mg/mmol for 6 months) the use of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) should be considered as adjunctive or monotherapy under the guidance of a nephrologist, even if they haven’t met the threshold for performing a kidney biopsy (section 1.1). | 2C |

| Section 3: Management of acute GI bleeding | ||

| 3.1 | We suggest that corticosteroids (prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg/day for 1–2 weeks) are considered for children and young people with IgAV within 3 days of onset of severe abdominal pain (defined as pain requiring hospital admission) or acute GI bleeding after appropriate clinical review and the exclusion of other causes including intussusception. | 2B |

| Section 4: Management of suspected or proven intussusception | ||

| 4.1 | We recommend that specialist surgical and(/or)radiological advice is sought for children and young people with IgAV and abdominal symptoms suggestive of intussusception. | 1C |

| Section 5: Management of suspected or proven testicular involvement | ||

| 5.1 | We suggest that testicular involvement (orchiditis) should be considered in boys with IgAV who develop painful scrotal oedema that is associated with palpable purpuric lesions. | 2D |

| 5.2 | We suggest that treatment with corticosteroids (prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg/day for 1–2 weeks) should be considered in boys with IgAV who develop orchiditis after appropriate specialist advice such as a surgical opinion has been sought. | 2D |

| Section 6: Management of cases with atypical features | ||

| 6.1 | We suggest that a skin biopsy is undertaken in children and young people with IgAV who have an atypical purpuric/petechial rash or to exclude alternative diagnoses. | 2B |

| 6.2 | We suggest that when a skin biopsy is performed the histological analysis should specifically include evaluation of IgA deposition using immunofluorescence (fresh specimen) or immunohistochemistry (fixed tissue). | 2C |

| Section 7: Definition of persisting or recurrent disease | ||

| 7.1 | We suggest that children and young people with IgAV and a typical purpuric/petechial rash persisting for more than 1 month should be defined as having persisting disease. | 2B |

| 7.2 | We suggest that children and young people with IgAV who present with a reappearance of the typical purpuric/petechial rash after a symptom-free period of greater than 1 month should be defined as having recurrent disease. | 2B |

| Section 8: Long term follow up in IgAV | ||

| 8.1 | We recommend that children and young people with IgAV should have follow up whilst there is evidence of nephritis and for at least 3 years if they have experienced biopsy proven nephritis. | 1C |

AKIacute kidney injuryISKDCInternational Study of Kidney Diseases in ChildrenUP:UCurine protein to urine creatinine ratio

Initial management

Disease classification

European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR)/Paediatric Rheumatology INternational Trials Organisation (PRINTO)/Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES) Classification criteria were agreed by the IgAV GDG to classify IgAV. This was based on a study published by Ozen et al49 involving 860 children, demonstrating excellent sensitivity and specificity when used to distinguish it from other forms of vasculitis. It formed a strong recommendation and aligned with the SHARE consortium.13

Early specialist referral

No studies were identified that adequately addressed indications for specialist referral. Therefore, studies related to the need for hospital admission and/or treatment were used to generate discussion and create two recommendations. Severe organ involvement was felt to be so significant that if missed, there may be patient harm and assigned as a strong recommendation.

Nephritis screening

There were no studies directly comparing different clinical tests for the detection of nephritis. A total of 28 studies reported the use of clinical tests, including urinalysis (20/28 studies; 71%), a combination of urinalysis and other tests (7 studies; 25%) or renal function alone (1 study; 4%). In view of the lack of evidence, the group concluded that urinalysis was the minimal acceptable standard for nephritis screening incorporating existing clinical practice.

Treatment of musculoskeletal involvement

There were no specific studies found that robustly evaluated treatments for joint involvement. Five reports included analgesia, symptomatic support, hydration and bed rest. Prednisolone, given at a high dose over 4 weeks, was evaluated in a randomised controlled trial of 171 children where it reduced pain score and duration of pain, although the duration was not statistically significant.50 Due to the lack of long-term musculoskeletal morbidity related to this condition, the IgAV GDG agreed that the limited evidence did not justify the use of high-dose corticosteroids due to the side effect profile.

Management of complications

IgAV nephritis

The clinical indications for conducting a kidney biopsy were adapted from the SHARE initiative as this was felt to be the strongest evidence available. The ISKDC classification criteria were used in 21 studies. Koskela et al specifically compared the ISKDC classification criteria with the modified semiquantitative score suggesting superiority in predicting renal outcomes.51 The IgAV GDG were aware that studies in this area were ongoing and agreed that the ISKDC criteria were the most widely accepted in the literature and clinical practice at the time of deriving the recommendations. This is likely to be a priority area for the future update. To determine treatment initiation, the histological classification grade alone was used by most studies (9/13; 69%). No studies made direct comparisons. A further two studies (2/13; 15%) used a combination of histological features and clinical features,52 which aligned with the European SHARE initiative recommendation.13 A combination of clinical and histological features was agreed to be most reflective of clinical practice.

Aligned with previous Cochrane reviews, no studies provided conclusive evidence of a preferred treatment option for biopsy-proven nephritis. Treatments alluding to benefit included corticosteroids,1113 17 52,70 cyclophosphamide,11 13 52 53 55 56 59 60 62 65 68 70 71 azathioprine,11 13 53 55 56 64 68 70 ciclosporin A,11 52 58 63 72 mycophenolate mofetil,11 13 52 70 tacrolimus,52 67 intravenous immunoglobulin,54 69 urokinase,60,62 triptolide,66 low molecular-weight heparin,73 plasma exchange,62 74 warfarin,61 62 dipyridamole.61 62 65 The quality of studies was weak with heterogeneity and a short list of potential agents was developed.

The use of renin-angiotensin aldosterone system inhibition (RAASi) was reviewed in six low-quality studies.1113 53 55,57 As RAASi is standard of care for children with proteinuria, this was a specific recommendation.

Gastrointestinal involvement

For severe GI involvement, 16 studies reported positive efficacy from corticosteroids.1339 50 59 75,86 This included one placebo controlled randomised trial (n=171 participants) demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in the severity of abdominal pain within 2 weeks from diagnosis compared with placebo.50 A systematic review by Weiss et al found a statistically significant benefit from abdominal pain within 24 hours following the use of corticosteroids.87 Weiss et al and Zhao et al demonstrated a decreased risk of intussusception, abdominal surgery, endoscopy and imaging if corticosteroids were received within 72 hours.88 89 Due to short-term morbidity, the IgAV GDG concluded that on balance, the evidence was sufficient to consider the use of a short course of corticosteroids for severe abdominal pain and/or GI bleeding, once intussusception had been excluded. Specific investigations for GI bleeding were beyond the scope.

Intussusception management

There were 11 studies regarding intussusception management (10/23; 43%).5976 78 79 84 87,91 Weiss et al88 described the most common abdominal surgery, which was intra-abdominal small bowel manipulation.87 88 No studies compared interventions and the quality of the evidence was weak. Due to the high risk of complications, the IgAV GDG agreed on a strong recommendation to obtain specialist advice.

Testicular involvement

Reports on testicular involvement were limited with orchiditis, defined as painful, acute scrotal oedema associated with palpable purpuric lesions.79 Five small studies described treatment,13 75 79 81 85 including the effective use of corticosteroids (a total of 15 patients in three studies).79 81 85 The literature highlighted that surgical exploration may be required to exclude differential diagnoses.75 The group agreed that a short course of corticosteroids could be considered for this complication and this aligned with the European SHARE initiative.13

Atypical disease course

Three studies (3/83; 3.6%) included performing a skin biopsy in atypical disease and it forms part of the classification criteria, therefore it was recommended.

Persisting or recurrent disease

Eight studies (8/82; 9.8%) included a definition for persisting disease and agreed on skin lesions for >1 month and 34 provided a definition for recurrent IgAV with the majority (n=19/34; 56%) using rash reappearance after a 1-month symptom-free period.

Long-term follow-up

There were 22 studies (22/82; 27%) with indications for long-term follow-up,1719 39 52 55 56 61 63 66 68 70 71 75 82 84,86 92 of which 17 related to nephritis.1952 55 56 61 63 66 68 70 71 75 84,86 93 94 96 Based on low-quality evidence, the IgAV GDG made a strong recommendation to follow-up patients who had experienced biopsy-proven nephritis due to the risk of CKD.

Discussion

IgA vasculitis is a small vessel vasculitis characterised by IgA1-dominant immune deposits. Due to the recognised risk of kidney failure that is consistently reported at 1%–2% in children, and far greater at 2.9%–23.9% in the adult population, there is a major unmet need for evidence generation for this condition.6 97 The aim of this project was to use a best available evidence, group agreement, based approach to develop national recommendations for the initial management of IgAV and its associated complications in children and young people. Using accredited methodology and an inclusive, multiprofessional, representative working group, evidence was generated based on key topics. Recommendations for both the initial management, aimed at primary and secondary care colleagues, and the management of complications, aimed at secondary and tertiary care colleagues, for IgAV in children and young people have been established. These guidelines have been endorsed nationally and are available online.

The derived recommendations were developed from primary evidence, incorporating pooled expertise where evidence was lacking, and largely aligned with existing international consensus management such as that published by the SHARE initiative.13 Similarities to this previous work included the accepted classification criteria, screening for nephritis and broadly the management of gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal symptoms. Topic areas that required added detail or were new included when to consider a specialist referral, kidney biopsy indications and nephritis management, the use of RAASi and the definitions of recurrent or persisting disease.

Guidelines form an important component to guide equity of treatment for rare diseases across regions and facilitate standardisation as a pathway for clinical trials. While suitable targets for this disease may not yet be apparent as the underlying pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, the reported mechanisms leading to IgAV nephritis are strikingly similar to those described in IgA nephropathy with galactose-deficient IgA1 acting as a key antibody for immune complex formation, there therefore may be repurposing opportunities.98 These first national guidelines also include parameters for audit and highlight research priorities, including defining the rates of hypertension; the indications, timing and duration of corticosteroids for GI involvement; suitable GI outcome measures and GI biomarkers; management of persisting and/or recurrent disease; and predictors and treatments for biopsy-proven nephritis. This study does have limitations, which includes the significant lack of high-quality evidence to generate strong recommendations together with areas of actively evolving research that may be subjected to change in the near future, for example, the optimal method to score the kidney histology, and finally the national based approach when this disease has unmet need for children worldwide. However, this manuscript demonstrates a successful method to unite clinical approaches despite these recognised limitations in a disease with a severe paucity of evidence. Future updates will continue to incorporate emerging evidence and reflect changes in clinical management.

Conclusion

IgAV is a rare condition that predominates in children where there is huge unmet need in evidence-based management. These guidelines provide an important foundation to standardise management nationally, which should reduce variability in clinical care ensuring equity of access for all children. Indirectly it is also anticipated that they will be a catalyst to enhance the generation of evidence.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The team would like to acknowledge the support received by patient associations and parent representatives who are co-authors.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was conducted without any dedicated funding however an educational grant provided by Novartis covered the costs associated with the face-to-face events. The Wellcome Trust provided a strategic institutional grant in support of the lead author and Versus Arthritis provide funding to support the Experimental Arthritis Treatment Centre for Children which is based at Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust Hospital and provides infrastructure to support several of the authors. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the industry partners, the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Louise Oni, Email: louise.oni@liverpool.ac.uk.

Caroline Platt, Email: caroline.platt@uhbw.nhs.uk.

Matko Marlais, Email: matko.marlais@gosh.nhs.uk.

Liza McCann, Email: liza.mccann@alderhey.nhs.uk.

Farah Barakat, Email: farah.barakat@nhs.net.

Markus Hesseling, Email: markus.hesseling@childrenshealthireland.ie.

Hannah Cottis, Email: hannahcottis@nhs.net.

Sue Protheroe, Email: sue.protheroe@nhs.net.

Gabrielle Haigh, Email: g.a.haigh@doctors.org.uk.

Kerstin Nott, Email: kerstinnott@doctors.org.uk.

Julien Marro, Email: J.G.Marro@student.liverpool.ac.uk.

Elizabeth King, Email: elizabethjking@hotmail.com.

Jane Kelly, Email: jane.kelly8@nhs.net.

Jill Sussens, Email: jill.sussens@nuh.nhs.uk.

Shirley Mulvaney, Email: shirley.mulvaney@alderhey.nhs.uk.

Thomas Whitby, Email: thomas.whitby@alderhey.nhs.uk.

Iona Morgan, Email: iona.morgan3@ggc.scot.nhs.uk.

Amita Sharma, Email: amita.sharma@ggc.scot.nhs.uk.

Reem Al-Jayyousi, Email: reem.aljayyousi@mbru.ac.ae.

Chee Kay Cheung, Email: ckc15@leicester.ac.uk.

Christopher Ng, Email: christopher.ng1@nhs.net.

Anthony David Lander, Email: t.lander@nhs.net.

William Simmons, Email: william.simmons@alderhey.nhs.uk.

Charlotte Melling, Email: charlotte.melling@alderhey.nhs.uk.

Rebecca Grandison, Email: rebeccaclapham@hotmail.com.

Leanne Treitl, Email: leanne.treitl@gmail.com.

Alan D Salama, Email: a.salama@ucl.ac.uk.

Jan Dudley, Email: jan.dudley@uhbw.nhs.uk.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

References

- 1.Tracy A, Subramanian A, Adderley NJ, et al. Cardiovascular, thromboembolic and renal outcomes in IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura): a retrospective cohort study using routinely collected primary care data. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:261–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piram M, Maldini C, Biscardi S, et al. Incidence of IgA vasculitis in children estimated by four-source capture-recapture analysis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:1358–66. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin A vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:171–8. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835d8e2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu L, Li Y, Wu X. IgA vasculitis update: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and biomarkers. Front Immunol. 2022;13:921864. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.921864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:603–6. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0869-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oni L, Sampath S. Childhood IgA Vasculitis (Henoch Schonlein Purpura)-Advances and Knowledge Gaps. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:257. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marro J, Williams C, Pain CE, et al. A case series on recurrent and persisting IgA vasculitis (Henoch Schonlein purpura) in children. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2023;21:85. doi: 10.1186/s12969-023-00872-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronkainen J, Nuutinen M, Koskimies O. The adult kidney 24 years after childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2002;360:666–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butani L, Morgenstern BZ. Long-term outcome in children after Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007;46:505–11. doi: 10.1177/0009922806298896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mary A-L, Clave S, Rousset-Rouviere C, et al. Outcome of children with IgA vasculitis with nephritis treated with steroids: a matched controlled study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38:3317–26. doi: 10.1007/s00467-023-05981-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn D, Hodson EM, Willis NS, et al. Interventions for preventing and treating kidney disease in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD005128. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005128.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartapisak W, Opastirakul S, Hodson EM, et al. Interventions for preventing and treating kidney disease in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD005128. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005128.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozen S, Marks SD, Brogan P, et al. European consensus-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of immunoglobulin A vasculitis—the SHARE initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:1607–16. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luqmani RA, Suppiah R, Grayson PC, et al. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis - update on the ACR/EULAR diagnosis and classification of vasculitis study (DCVAS) Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 Suppl 1:11–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021) Cochrane; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gökçe Ş, Kurugöl Z, Koturoğlu G, et al. Predictive role of laboratory markers and clinical features for recurrent Henoch-Schönlein Purpura in childhood: A study from Turkey. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30:1047–52. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2019.1690966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162–8. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, et al. Clinical course of extrarenal symptoms in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a 6-month prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:871–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.167874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfredo CS, Nunes NA, Len CA, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: recurrence and chronicity. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2007;0:177–80. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan H, Tang Y-L, Lv X-H, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Renal Involvement in Childhood Henoch-Schönlein Purpura: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demirkaya E, Ozen S, Pistorio A, et al. Performance of Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score and disease extent index in childhood vasculitides. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:S162–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolezalová P, Telekesová P, Nemcová D, et al. Incidence of vasculitis in children in the Czech Republic: 2-year prospective epidemiology survey. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley J, Smith G, Llewelyn-Edwards A, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether steroids reduce the incidence and severity of nephropathy in Henoch-Schonlein Purpura (HSP) Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:756–63. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekinci RMK, Balci S, Sari Gokay S, et al. Do practical laboratory indices predict the outcomes of children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Postgrad Med. 2019;131:295–8. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1609814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Porrúa C, Calviño MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: Clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149–56. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.33980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, et al. Renal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura in a 6-month prospective study of 223 children. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:877–82. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.182394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH, Hong SH, Jun J, et al. Treatment of refractory IgA vasculitis with dapsone: a systematic review. Clin Exp Pediatr . 2020;63:158–63. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2019.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu SH, Liao PY, Chen XQ, et al. Add-on therapy with montelukast in the treatment of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:315–22. doi: 10.1111/ped.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei W-T, Tsai P-L, Chu S-H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for recurrent Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from a 16-year nationwide database. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16:25. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0247-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Tang M, Yao X, et al. A clinicopathological comparison between IgA nephropathy and Henoch–Schönlein purpura nephritis in children: use of the Oxford classification. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2019;23:1382–90. doi: 10.1007/s10157-019-01777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao CH, Tsai M, Yang YH, et al. Onset age is a risk factor for refractory pediatric IgA vasculitis: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18:86. doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-00480-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma D-Q, Li Y, Han Z-G, et al. Analysis on kidney injury-related clinical risk factors and evaluation on the therapeutic effects of hemoperfusion in children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:3894–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao S, Xuan X, Sha Y, et al. Clinico-pathological association of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura nephritis and IgA nephropathy in children. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2334–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Özdemir ZC, Çetin N, Kar YD, et al. Hemotologic Indices for Predicting Internal Organ Involvement in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (IgA vasculitis) J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42:e46–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhim JW, Lee YT, Kang HM, et al. Changes in clinical features in Henoch-Schönlein purpura during three decades: an observational study at a single hospital in Korea. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2811–8. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JI, Park JM, Shin YH, et al. Predictive factors for nephritis, relapse, and significant proteinuria in childhood Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:56–60. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin JI, Lee SJ, Lee JS, et al. Intravenous dexamethasone followed by oral prednisolone versus oral prednisolone in the treatment of childhood Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1429–32. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng MC, Wang LC, Yu HH, et al. Kawasaki disease and Henoch–Schönlein purpura – 10 years’ experience of childhood vasculitis at a university hospital in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapani S, Micheli A, Grisolia F, et al. Henoch Schonlein purpura in childhood: epidemiological and clinical analysis of 150 cases over a 5-year period and review of literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:143–53. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uehara E, Nagata C, Masuda H, et al. Risk factors of long hospital stay for immunoglobulin A vasculitis: Single‐center study. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:918–22. doi: 10.1111/ped.13685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson L, Richardson ARW, Holt RCL, et al. Henoch schonlein purpura--a 5-year review and proposed pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao YL, Liu ZJ, Bai XM, et al. Obesity increases the risk of renal involvement in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:1357–63. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Calviño MC, Vazquez-Lopez ME, et al. Implications of upper respiratory tract infections and drugs in the clinical spectrum of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:781–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JJ, Xu Y, Liu FF, et al. Association of the infectious triggers with childhood Henoch-Schonlein purpura in Anhui province, China. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan GZ, Li RX, Jiang Q, et al. Streptococcal infection in childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a 5-year retrospective study from a single tertiary medical center in China, 2015-2019. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19:79. doi: 10.1186/s12969-021-00569-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Xia G, Nie X, et al. Differences in Manifestations and Gut Microbiota Composition Between Patients With Different Henoch-Schonlein Purpura Phenotypes. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:641997. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.641997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sestan M, Srsen S, Kifer N, et al. Persistence and Severity of Cutaneous Manifestations in IgA Vasculitis Is Associated with Development of IgA Vasculitis Nephritis in Children. Dermatology . 2022;238:340–6. doi: 10.1159/000516765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y, Wang JJ, Liu FF, et al. Predisposing factors of childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura in Anhui province, China. J Investig Med . 2019;67:771–8. doi: 10.1136/jim-2018-000906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, et al. EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, Ala-Houhala M, et al. Early prednisone therapy in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2006;149:241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koskela M, Ylinen E, Ukonmaanaho E-M, et al. The ISKDC classification and a new semiquantitative classification for predicting outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:1201–9. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen RF, Rubak S, Jespersen B, et al. Early high-dose immunosuppression in Henoch-Schönlein nephrotic syndrome may improve outcome. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:409–15. doi: 10.3109/00365590903164480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altugan FS, Ozen S, Aktay-Ayaz N, et al. Treatment of severe Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: justifying more immunosuppression. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51:551–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L, Wang X, Yin L, et al. Effects of dexamethasone and gamma globulin combined with prednisone on the therapeutic effect and immune function of Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis in children. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e23580. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delbet JD, Hogan J, Aoun B, et al. Clinical outcomes in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis without crescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:1193–9. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delbet J-D, Geslain G, Auger M, et al. Histological prognostic factors in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:313–20. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04363-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gómez S, Pérez M, Pellegrini M, et al. Henoch-Schonlein purpura in pediatrics: Ten years of experience at a moderate risk office of a general hospital. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2020;118:31–7. doi: 10.5546/aap.2020.eng.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Autio-Harmainen H, et al. Cyclosporine A vs. methylprednisolone for Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: a randomized trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:2159–66. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1919-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karadağ ŞG, Tanatar A, Sönmez HE, et al. The clinical spectrum of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children: a single-center study. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:1707–14. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04460-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawasaki Y, Suzuki J, Suzuki H. Efficacy of methylprednisolone and urokinase pulse therapy combined with or without cyclophosphamide in severe Henoch-Schoenlein nephritis: a clinical and histopathological study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:858–64. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawasaki Y, Suzuki J, Nozawa R, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone and urokinase pulse therapy for severe Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Pediatrics. 2003;111:785–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawasaki Y, Suyama K, Yugeta E, et al. The incidence and severity of Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis over a 22-year period in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:1023–9. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koskela M, Jahnukainen T, Endén K, et al. Methylprednisolone or cyclosporine a in the treatment of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: a nationwide study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1447–56. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Devidayal SS, Kumar L, Joshi K, et al. Severe Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: resolution with azathioprine and steroids. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22:133–7. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanaka H, Suzuki K, Nakahata T, et al. Early treatment with oral immunosuppressants in severe proteinuric purpura nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:347–50. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xia Y, Mao J, Chen Y, et al. Clinical outcomes in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis grade IIIa or IIIb. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1083–8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang D-F, Hao G-X, Li C-Z, et al. Off-label use of tacrolimus in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis: a pilot study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:772–5. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dundar HA, Pektanc M, Bayram MT, et al. Obesity is associated with severe clinical course in children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:2327–33. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buscatti IM, Casella BB, Aikawa NE, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis: initial risk factors and outcomes in a Latin American tertiary center. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:1319–24. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schinzel V, Fernandez JD, Clemente G, et al. The profile and clinical outcomes of patients with renal involvement due to IgA vasculitis: is azathioprine a good option for treatment? Adv Rheumatol . 2019;59:21. doi: 10.1186/s42358-019-0064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tarshish P, Bernstein J, Edelmann CM., Jr Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis: course of disease and efficacy of cyclophosphamide. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:51–6. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ronkainen J, Autio-Harmainen H, Nuutinen M. Cyclosporin A for the treatment of severe Henoch-Schönlein glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:1138–42. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tian M, Liu C. Heparin calcium treated Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis in children through inhibiting hyperfibrinolysis. Ren Fail. 2015;37:1100–4. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2015.1061668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shenoy M, Ognjanovic MV, Coulthard MG. Treating severe Henoch-Schönlein and IgA nephritis with plasmapheresis alone. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1167–71. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0498-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lardhi AA. Henoch-Schonlein purpura in children from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:973–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rubino C, Monacelli C, Marrani E, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in IgA vasculitis: a single-center 11-year study on a cohort of 118 children. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:5041–6. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05863-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anil M, Aksu N, Kara OD, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children from western Turkey: a retrospective analysis of 430 cases. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51:429–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cakir M, Orhan F, Mungan I, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in north-eastern Turkey. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2006;26:59–65. doi: 10.1179/146532806X90628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.de Almeida JLJ, Campos LMA, Paim LB, et al. Renal involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a multivariate analysis of initial prognostic factors. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2007;83:259–66. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sestan M, Kifer N, Frkovic M, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement and its association with the risk for nephritis in IgA vasculitis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X211024828. doi: 10.1177/1759720X211024828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yilmaz A, Aytac MB, Ekinci Z. Retrospective Assessment of Children with Henoch-Schonlein Purpura in and around Kocaeli Province and Comparison with Literature. Erciyes Med J . 2014;36:62–7. doi: 10.5152/etd.2013.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prais D, Amir J, Nussinovitch M. Recurrent Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:25–8. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000255692.46165.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Calvo-Río V, Hernández JL, Ortiz-Sanjuán F, et al. Relapses in patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Analysis of 417 patients from a single center. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4217. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ekinci RMK, Balci S, Melek E, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of 420 children with Henoch Schönlein Purpura from a single referral center from Turkey: A three-year experience. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30:1039–46. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2019.1687074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fretzayas A, Sionti I, Moustaki M, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a long-term prospective study in Greek children. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14:324–31. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31817a240a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee YH, Kim YB, Koo JW, et al. Henoch-Schonlein Purpura in Children Hospitalized at a Tertiary Hospital during 2004-2015 in Korea: Epidemiology and Clinical Management. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr . 2016;19:175–85. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2016.19.3.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weiss PF, Feinstein JA, Luan X, et al. Effects of corticosteroid on Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1079–87. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Localio R, et al. Corticosteroids may improve clinical outcomes during hospitalization for Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatrics. 2010;126:674–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao Q, Yang Y, He SW, et al. Risk factors for intussusception in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura: A case-control study. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:6244–53. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huber AM, King J, McLaine P, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of prednisone in early Henoch Schönlein Purpura [ISRCTN85109383] BMC Med. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hwang HH, Lim IS, Choi BS, et al. Analysis of seasonal tendencies in pediatric Henoch-Schönlein purpura and comparison with outbreak of infectious diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12217. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rigante D, Candelli M, Federico G, et al. Predictive factors of renal involvement or relapsing disease in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:45–8. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shi D, Chan H, Yang X, et al. Risk factors associated with IgA vasculitis with nephritis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis) progressing to unfavorable outcomes: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Narchi H. Risk of long term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schonlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916–20. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.074641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Koskimies O, et al. Outcome of Henoch-Schönlein purpura 8 years after treatment with a placebo or prednisone at disease onset. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:933–9. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sano H, Izumida M, Shimizu H, et al. Risk factors of renal involvement and significant proteinuria in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:196–201. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0922-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stanway J, Brown N, Pervez A, et al. IgA vasculitis nephritis-outcomes in adult-onset disease. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2024:keae030. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Williams CEC, Lamond M, Marro J, et al. A narrative review of potential drug treatments for nephritis in children with IgA vasculitis (HSP) Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42:3189–200. doi: 10.1007/s10067-023-06781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.The UK Kidney Association The initial management of iga vasculitis (henoch schonlein purpura) in children and young people. 2022. https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/R2vFINAL_IgA%20vasculitis%20-%20initial%20management220523.pdf Available.

- 100.The UK Kidney Association The management of complications associated with iga vasculitis (henoch schonlein purpura) in children and young people. 2022. https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/R1vFINAL_IgA%20vasculitis%20-%20complications220523.pdf Available.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.