Abstract

Objectives

To assess the outcomes of percutaneous nephrostomy in England for renal decompression, in the context of metastatic cancer.

Methods

Retrospective observational study of all patients undergoing nephrostomy with a diagnosis of metastatic cancer from 2010 to 2019 in England, identified and followed up within Hospital Episode Statistics.

The primary outcome measure was mortality (14-day and 30-day postprocedure). Secondary outcomes included subsequent chemotherapy or surgery and direct complications of nephrostomy.

Results

10 932 patients were identified: 58.0% were male, 51.0% were >70 years old and 57.7% had no relevant comorbidities (according to Charlson’s criteria, other than cancer).

1 in 15 patients died within 14 days of nephrostomy and 1 in 6 died within 30 days. Factors associated with higher 30-day mortality were the presence of comorbidities (Charlson score 1–4 (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.50, p=0.003), score 5+ (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.45), p<0.001)); inpatient nephrostomy (OR 3.76, 95% CI 2.75 to 5.14, p<0.001) and admitted under the care of specialities of internal medicine (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.84 to 2.40, p<0.001), oncology (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.51 to 2.15, p<0.001), gynaecology/gynaeoncology (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.28, p=0.002) or general surgery (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.32 to 1.98, p<0.001)), compared with urology.

25.4% received subsequent chemotherapy. Receiving chemotherapy was associated with younger patients (eg, age 18–29 (OR 4.04, 95% CI 2.66 to 6.12, p<0.001) and age 30–39 (OR 3.07, 95% CI 2.37 to 3.97, p<0.001)) and under the care of oncology (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.40 to 1.83, p<0.001) or gynaecology/gynaeoncology (OR 1.64, 95%CI 1.28 to 2.10, p<0.001) compared with urology.

43.8% had subsequent abdominopelvic surgery. Not receiving surgery was associated with inpatient nephrostomy (OR 0.82, 95%CI 0.72 to 0.95,p=0.007): non-genitourinary cancers (eg, gynaecology/gynaeoncology cancer (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99, p=0.037)); and under the care of a non-surgical specialty (medicine (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.77, p<0.001), oncology (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.66, p<0.001)).

24.5% of patients had at least one direct complication of nephrostomy: 12.5% required early exchange of nephrostomy, 8.1% had bleeding and 6.7% had pyelonephritis.

Conclusions

The decision to undertake nephrostomy in patients with poor prognosis cancer is complex and should be undertaken in a multidisciplinary team setting. Complication rates are high and minimal survival benefit is derived in many patients, especially in the context of emergency inpatient care.

Keywords: Cancer, Genitourinary, Clinical decisions, End of life care, Palliative Care, Quality of life

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Malignant ureteric obstruction (MUO) in the context of metastatic cancer indicates a poor prognosis.

Nephrostomy is commonly used for renal decompression in these cases but rarely confers survival benefit.

Living with a nephrostomy is associated with complications and a reduced quality of life.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study provides a large cohort at a national level, considering the outcomes for patients with MUO in the context of metastatic disease.

As this is a Hospital Episode Statistics-based study, it provides a review of national practice and factors associated with poor prognosis.

The extremely poor mortality, especially in the context of emergency nephrostomy, displayed in this study will aid clinicians in being more selective when offering patients nephrostomy when presenting with MUO.

This study has displayed that few patients go on to have further treatment, therefore, significant numbers of patients receive a quality-of-life altering nephrostomy with no benefit in the form of treatment or survival.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Future research may be able to identify those indications where nephrostomy may offer survival benefit.

Patients managed by urology or oncology teams, as a primary speciality, at the time of nephrostomy insertion have better-predicted outcomes. Therefore, this research will empower clinical teams to seek early involvement urology and oncology teams for decision-making, in order to improve patient outcomes.

This study gives insight into the national burden of renal decompression in the context of metastatic cancer. It can help direct resource allocation and national policy with regard to this patient population.

Introduction

Percutaneous nephrostomy is routinely used to decompress obstructed renal systems; along with ureteric stenting. It allows the drainage of urine directly from the renal pelvicalyceal region, thus diverting urine away from more distal obstruction.

Malignant ureteric obstruction (MUO) is a clinical indication of advanced or disseminated cancers. The benefit of renal decompression in patients with a limited prognosis is contentious, with no clear guidance available for such situations.1 While there may be some advantage to avoiding the sequelae of postrenal obstruction, such as uraemia, electrolyte imbalance or infection, it is unclear what benefit many of these patients derive from nephrostomy in end-of-life care settings. Survival benefit has only been demonstrated in specific malignancies and only for those with slow-growing cancers.2

The aim of this study was to examine the outcomes including short-term survival and complications of nephrostomy in England for patients with malignant disease. Associations with short-term mortality, subsequent surgery and chemotherapy were examined.

Methods

Data source

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) is a nationally curated administrative database of all patients interacting with publicly funded hospital care in England. Data are organised longitudinally by hospital episode; the period of time under the care of a single consultant team. In addition to demographic details, information pertaining to operative procedures and diagnostic records is stored as Office of Population Census and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures, version 4 codes, and International Classification of Diseases version 10 codes, respectively.

Inclusion criteria

All patients undergoing nephrostomy with a diagnosis of metastatic cancer, diagnosed at any time prior to nephrostomy or within 3 months following nephrostomy, with the presence of a metastatic cancer code, between January 2010 and December 2019.

Exclusion criteria

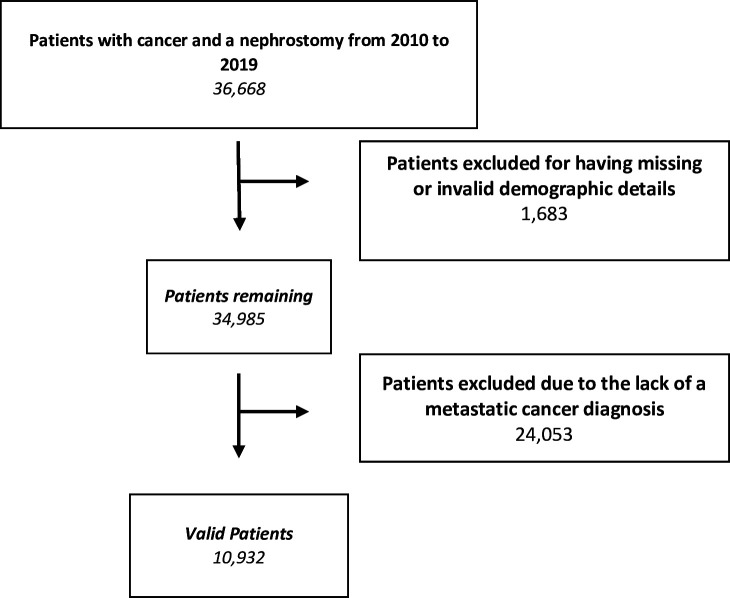

Patients were excluded for age <18, living outside of England and for missing data and follow-up. Further exclusions were made for lack of a metastatic cancer diagnosis (figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flow chart.

Demographic data

Age, sex, residential region, Index of Multiple Deprivations (IMD) 2010 quintile and ethnicity were included as demographic data. Charlson Comorbidity Score was calculated, with a modification to exclude a diagnosis of cancer; this has been validated in previous HES-based studies.3 4

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was 30-day mortality following index nephrostomy insertion. Secondary outcomes were receiving chemotherapy or further abdominopelvic surgery following nephrostomy and direct complications of nephrostomy.

Complications of nephrostomy were identified as pyelonephritis, bleeding/haematuria or early (within 2 months) exchange/resiting of nephrostomy.

Outpatient nephrostomy was defined as those patients attending electively as an outpatient or day case; with less than 1 night stay in hospital. Emergency admissions are flagged within the HES dataset.

Provider volume was identified as the total volume of cancer patients treated at the respective provider over the study period and was split into tertiles: low (1–1576 patients), medium (1577–3079) and high volume (3080+).

Site of cancer was split by primary tumour: genitourinary; gynaecological oncology; lower-gastrointestinal and all others. The primary specialty assigned to the index nephrostomy episode was considered to be the nephrostomy organising specialty.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed in order to consider the association of demographic and clinically relevant variables. Outcomes were likelihood of 30-day mortality, receiving further chemotherapy and receiving further abdominopelvic surgery. Codes for percutaneous procedures, purely diagnostic procedures and minor procedures not requiring regional or general anaesthetic were excluded.

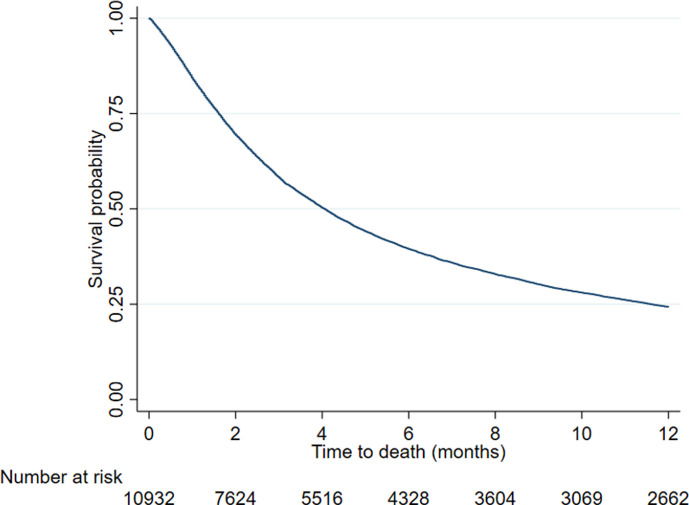

An unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curve following survival postnephrostomy for 6 months was constructed.

CIs were set at 95% and a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data extraction was performed in Microsoft SQL server and analyses were completed in STATA V16.

Results

Study patients

There were 10 932 patients identified as undergoing nephrostomy with a concurrent diagnosis of metastatic cancer. Median age was 70 years old (IQR 60–78). The majority were male (58%) (table 1). 57.7% of patients had no recorded comorbidities. Patients predominately had genitourinary cancers (53.2%), followed by gynaecological cancers (18.9%).

Table 1. Demographics details of the study patients.

| Demographic category | Patients | Percentage | |

| Sex | Male | 6341 | 58.0 |

| Female | 4591 | 42.0 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 102 | 0.9 |

| 30–39 | 294 | 2.7 | |

| 40–49 | 658 | 6.0 | |

| 50–59 | 1475 | 13.5 | |

| 60–69 | 2831 | 25.9 | |

| 70+ | 5572 | 51.0 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 9954 | 91.1 |

| Asian | 328 | 3.0 | |

| Other minority ethnicity | 370 | 3.4 | |

| Unknown | 280 | 2.6 | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 | 6307 | 57.7 |

| 1–4 | 1379 | 12.6 | |

| 5+ | 3246 | 29.7 | |

| IMD deprivation quintiles | 1 (most deprived) | 2059 | 18.8 |

| 2 | 2142 | 19.6 | |

| 3 | 2221 | 20.3 | |

| 4 | 2336 | 21.4 | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 2174 | 19.9 | |

| Procedure year | 2010–2011 | 2124 | 19.4 |

| 2012–2013 | 2224 | 20.3 | |

| 2014–2015 | 2186 | 20.0 | |

| 2016–2017 | 2173 | 19.9 | |

| 2018–2019 | 2225 | 20.4 | |

| Medium | 2927 | 26.8 | |

| High | 6781 | 62.0 | |

| Inpatient/outpatient | Inpatient | 9936 | 90.9 |

| Outpatient | 996 | 9.1 | |

| Cancer type | Genitourinary | 5812 | 53.2 |

| Gynaecological oncology | 2061 | 18.9 | |

| Digestive | 1767 | 16.2 | |

| Other | 1292 | 11.8 | |

| Provider cancer volume tertile | 1–1576 | 1694 | 15.5 |

| 1577–3079 | 3223 | 29.5 | |

| 3080+ | 6015 | 55.0 | |

| Specialty | Urology | 5106 | 46.7 |

| Medicine | 2423 | 22.2 | |

| Oncology | 1692 | 15.5 | |

| General surgery | 885 | 8.1 | |

| Gynaecology/gynaecological oncology | 345 | 3.2 | |

| Other | 481 | 4.4 | |

| Complications | Bleeding | 885 | 8.1 |

| Infection | 729 | 6.7 | |

| Exchange/reinsertion of nephrostomy | 1365 | 12.5 | |

| Nephrostomy performed at provider with radiotherapy unit | 5511 | 50.4 | |

| Mortality 14 days | 717 | 6.6 | |

| Mortality 30 days | 1701 | 15.6 | |

| Treatment received | Chemotherapy and surgery | 1617 | 14.8 |

| Chemotherapy only | 1157 | 10.6 | |

| Surgery only | 3172 | 29.0 | |

| No chemotherapy or surgery | 4986 | 45.6 | |

| Total patients | 10 932 | ||

IMDIndex of Multiple Deprivation

Outpatient or daycase nephrostomy was performed in only 9.1% of the cohort; of those with an inpatient nephrostomy, 78.7% were during an unplanned or emergency admission and median time to nephrostomy for such patients was 3 days (IQR 1–7).

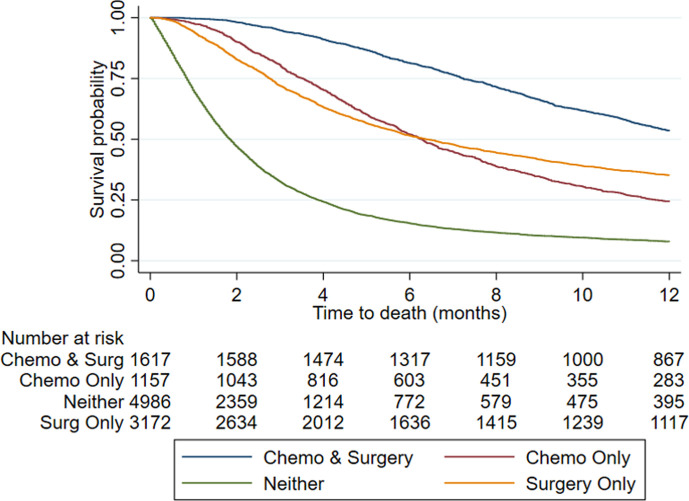

Mortality

Median survival was 124 (IQR 49–354 days (figure 2). Median survival for patients who have chemotherapy or surgery is 293 days (155 571) and 274 days (113 672), respectively (figure 3), compared with 56 days (26 118) for patients who have no treatment. Crude mortality data are described in table 2.

Figure 2. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meir survival curve for time to death (months) following insertion of nephrostomy.

Figure 3. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meir survival curve for time to death (months) following insertion of nephrostomy with cohort split by further treatment received.

Table 2. Descriptive data for deaths following nephrostomy.

| N | Death within 14 days | In hospital death within 14 days | Death within 30 days | In hospital death within 30 days | ||

| Total | 10 932 | 717 (6.6%) | 587 (5.4%) | 1701 (15.6%) | 1123 (10.3%) | |

| Inpatient nephrostomy(n=9936) | Elective inpatient | 2120 | 85 (4.0%) | 578 (3.6%) | 205 (9.7%) | 146 (6.9%) |

| Emergency inpatient | 7816 | 620 (7.9%) | 502 (6.4%) | 1451 (18.6%) | 956 (12.2%) | |

| Outpatient nephrostomy | 996 | 12 (1.2%) | 9 (0.9%) | 45 (4.5%) | 21 (2.1%) | |

A 30-day mortality was associated with the following variables: inpatient nephrostomy (OR 3.76, 95% CI 2.75 to 5.14, p<0.001); increasing comorbidity (score 1–4 (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.50, p=0.003), score 5+ (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.45), p<0.001)) and under the care of specialties other than urology (medicine (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.84 to 2.40, p<0.001), oncology (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.51 to 2.15, p<0.001), general surgery (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.32 to 1.98, p<0.001) and gynaecology/gynaeoncology (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.28, p=0.002) and older age compared with patients over 70 (age 18–29 (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.79, p=0.010), age 30–39 (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.99, p=0.043), age 40–49 (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.85, p=0.001)) (table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with death within 30 days of nephrostomy.

| Demographic category | OR | P value | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Male (baseline) | |||

| Female | 1.03 | 0.718 | 0.89 to 1.19 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 0.36 | 0.010 | 0.16 to 0.79 |

| 30–39 | 0.68 | 0.043 | 0.47 to 0.99 | |

| 40–49 | 0.65 | 0.001 | 0.51 to 0.85 | |

| 50–59 | 0.85 | 0.068 | 0.72 to 1.01 | |

| 60–69 | 0.91 | 0.160 | 0.80 to 1.04 | |

| 70+ (baseline) | ||||

| Ethnicity | White (baseline) | |||

| Asian | 0.73 | 0.066 | 0.52 to 1.02 | |

| Other minority ethnicity | 0.78 | 0.124 | 0.57 to 1.07 | |

| Unknown | 1.64 | 0.001 | 1.23 to 2.21 | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 (baseline) | |||

| 1–4 | 1.27 | 0.003 | 1.08 to 1.50 | |

| 5+ | 1.29 | <0.001 | 1.14 to 1.45 | |

| IMD deprivation quintiles | 1 (most deprived) (baseline) | |||

| 2 | 1.20 | 0.036 | 1.01 to 1.43 | |

| 3 | 1.20 | 0.037 | 1.01 to 1.42 | |

| 4 | 1.05 | 0.615 | 0.88 to 1.24 | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 1.04 | 0.695 | 0.87 to 1.24 | |

| Procedure year | 2010–2011 (baseline) | |||

| 2012–2013 | 1.17 | 0.058 | 0.99 to 1.38 | |

| 2014–2015 | 0.98 | 0.831 | 0.83 to 1.16 | |

| 2016–2017 | 0.93 | 0.379 | 0.78 to 1.10 | |

| 2018–2019 | 0.89 | 0.167 | 0.75 to 1.05 | |

| Provider cancer volume tertile | 1–1576 (baseline) | |||

| 1577–3079 | 1.00 | 0.957 | 0.85 to 1.18 | |

| 3080+ | 0.87 | 0.106 | 0.73 to 1.03 | |

| Inpatient/outpatient | Inpatient | 3.76 | <0.001 | 2.75 to 5.14 |

| Outpatient (baseline) | ||||

| Cancer type | Genitourinary (baseline) | |||

| Gynaecological oncology | 1.12 | 0.252 | 0.92 to 1.37 | |

| Digestive | 0.99 | 0.887 | 0.84 to 1.17 | |

| Other | 1.75 | <0.001 | 1.47 to 2.09 | |

| Specialty | Urology (baseline) | |||

| Medicine | 2.10 | <0.001 | 1.84 to 2.40 | |

| Oncology | 1.80 | <0.001 | 1.51 to 2.15 | |

| General surgery | 1.62 | <0.001 | 1.32 to 1.98 | |

| Gynaecology/gynaecological oncology | 1.66 | 0.002 | 1.21 to 2.28 | |

| Other | 1.72 | <0.001 | 1.29 to 2.30 | |

| Nephrostomy performed at provider with radiotherapy unit | 0.90 | 0.134 | 0.79 to 1.03 | |

p values < 0.001 are in bold.

IMDIndex of Multiple Deprivation

Chemotherapy

4986 (45.6%) patients had neither surgery nor chemotherapy following nephrostomy. 25.4% of patients received chemotherapy of any type within 6 months of index nephrostomy: 44.7% of outpatient nephrostomy patients but only 23.4% of inpatient nephrostomy patients.

Factors associated with later receiving chemotherapy (table 4) included: younger age(age 18–29 (OR 4.04, 95% CI 2.66 to 6.12, p<0.001), age 30–39 (OR 3.07, 95% CI 2.37 to 3.97, p<0.001), age 40–49 (OR 2.80, 95% CI 2.33 to 3.38, p<0.001), age 50–59 (OR 2.49, 95% CI 2.16 to 2.86, p<0.001), age 60–69 (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.89 to 2.38, p<0.001)); less deprivation (IMD deprivation quintile 4 (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.50, p=0.001), IMD deprivation quintile 5 (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.84, p<0.001)); nephrostomy in a more recently (years 2016/2017 (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.52, p=0.001), years 2018/2019 (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.67, p<0.001)); gynaecological cancer (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.47, p=0.009); under the care of oncology (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.40 to 1.83, p<0.001) or gynaeoncology (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.10, p<0.001), rather than medicine (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.72, p<0.001); increasing comorbidity (Charlson score 1–4 (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91, p=0.001), Charlson score 5 (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.59, p<0.001)) and inpatient nephrostomy (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.48, p<0.001).

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression for analysis of factors associated with chemotherapy following nephrostomy.

| Demographic category | OR | P value | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Male (baseline) | |||

| Female | 1.09 | 0.176 | 0.96 to 1.24 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 4.04 | <0.001 | 2.66 to 6.12 |

| 30–39 | 3.07 | <0.001 | 2.37 to 3.97 | |

| 40–49 | 2.80 | <0.001 | 2.33 to 3.38 | |

| 50–59 | 2.49 | <0.001 | 2.16 to 2.86 | |

| 60–69 | 2.12 | <0.001 | 1.89 to 2.38 | |

| 70+ (baseline) | ||||

| Ethnicity | White (baseline) | |||

| Asian | 0.94 | 0.645 | 0.72 to 1.23 | |

| Other minority ethnicity | 1.04 | 0.734 | 0.81 to 1.35 | |

| Unknown | 0.63 | 0.004 | 0.46 to 0.86 | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 (baseline) | |||

| 1–4 | 0.79 | 0.001 | 0.69 to 0.91 | |

| 5+ | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.47 to 0.59 | |

| IMD deprivation quintiles | 1 (most deprived) (baseline) | |||

| 2 | 1.18 | 0.034 | 1.01 to 1.37 | |

| 3 | 1.07 | 0.386 | 0.92 to 1.25 | |

| 4 | 1.29 | 0.001 | 1.11 to 1.50 | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 1.58 | <0.001 | 1.36 to 1.84 | |

| Procedure year | 2010–2011 (baseline) | |||

| 2012–2013 | 1.06 | 0.441 | 0.91 to 1.23 | |

| 2014–2015 | 1.14 | 0.086 | 0.98 to 1.32 | |

| 2016–2017 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 1.13 to 1.52 | |

| 2018–2019 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.24 to 1.67 | |

| Provider cancer volume tertile | 1–1576 (baseline) | |||

| 1577–3079 | 0.94 | 0.471 | 0.81 to 1.10 | |

| 3080+ | 1.07 | 0.428 | 0.91 to 1.25 | |

| Inpatient/outpatient | Inpatient | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.35 to 0.48 |

| Outpatient (baseline) | ||||

| Cancer type | Genitourinary (baseline) | |||

| Gynaecological oncology | 1.25 | 0.009 | 1.06 to 1.47 | |

| Digestive | 1.08 | 0.264 | 0.94 to 1.24 | |

| Other | 0.71 | <0.001 | 0.59 to 0.84 | |

| Specialty | Urology (baseline) | |||

| Medicine | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.55 to 0.72 | |

| Oncology | 1.60 | <0.001 | 1.40 to 1.83 | |

| General surgery | 0.85 | 0.085 | 0.71 to 1.02 | |

| Gynaecology/gynaecological oncology | 1.64 | <0.001 | 1.28 to 2.10 | |

| Other | 0.82 | 0.092 | 0.65 to 1.03 | |

| Nephrostomy performed at provider with radiotherapy unit | 1.08 | 0.196 | 0.96 to 1.21 | |

p values < 0.001 are in bold.

IMDIndex of Multiple Deprivation

Surgery

4789 (43.8%) of patients had later abdominopelvic surgery. Factors associated with proceeding to surgery were (table 5): younger age compared with those over 70 (age 18–29 (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.27, p=0.045), age 30–39 (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.94, p=0.001), age 40–49 (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.74, p<0.001), age 50–59 (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.52, p<0.001), age 60–69 (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.32, p<0.001)); female ((OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.26, p=0.029)); high comorbidity score, score 5+ (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.86), p<0.001)); inpatient nephrostomy (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.95, p=0.007); gynaeoncology cancer (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99, p=0.037), other cancers (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.86, p<0.001)) and under the care of medicine (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.77, p<0.001) or oncology (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.66, p<0.001).

Table 5. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with surgery following nephrostomy.

| Demographic category | OR | P value | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Male (Baseline) | |||

| Female | 1.13 | 0.029 | 1.01 to 1.26 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 1.51 | 0.045 | 1.01 to 2.27 |

| 30–39 | 1.52 | 0.001 | 1.18 to 1.94 | |

| 40–49 | 1.47 | <0.001 | 1.23 to 1.74 | |

| 50–59 | 1.34 | <0.001 | 1.19 to 1.52 | |

| 60–69 | 1.20 | <0.001 | 1.09 to 1.32 | |

| 70+ (Baseline) | ||||

| Ethnicity | White (Baseline) | |||

| Asian | 1.21 | 0.102 | 0.96 to 1.52 | |

| Other minority ethnicity | 1.15 | 0.197 | 0.93 to 1.43 | |

| Unknown | 0.76 | 0.036 | 0.59 to 0.98 | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 (Baseline) | |||

| 1–4 | 0.89 | 0.056 | 0.79 to 1.00 | |

| 5+ | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.72 to 0.86 | |

| IMD deprivation quintiles | 1 (Most Deprived) (Baseline) | |||

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.997 | 0.88 to 1.13 | |

| 3 | 1.09 | 0.178 | 0.96 to 1.24 | |

| 4 | 1.10 | 0.135 | 0.97 to1.25 | |

| 5 (Least Deprived) | 1.04 | 0.542 | 0.92 to 1.18 | |

| Procedure year | 2010–11 (Baseline) | |||

| 2012–13 | 0.93 | 0.262 | 0.83 to 1.05 | |

| 2014–15 | 0.86 | 0.017 | 0.76 to 0.97 | |

| 2016–17 | 0.86 | 0.013 | 0.76 to 0.97 | |

| 2018–19 | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.38 to 0.49 | |

| Provider cancer volume tertile | 1–1576 (Baseline) | |||

| 1577–3079 | 0.91 | 0.158 | 0.81 to 1.04 | |

| 3080+ | 1.02 | 0.740 | 0.90 to 1.16 | |

| Inpatient/Outpatient | Inpatient | 0.82 | 0.007 | 0.72 to 0.95 |

| Outpatient (Baseline) | ||||

| Cancer type | Genitourinary (Baseline) | |||

| Gynaecological oncology | 0.86 | 0.037 | 0.74 to 0.99 | |

| Lower GI | 0.94 | 0.350 | 0.84 to 1.06 | |

| Other | 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.65 to 0.86 | |

| Specialty | Urology (Baseline) | |||

| Medicine | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.63 to 0.77 | |

| Oncology | 0.58 | <0.001 | 0.51 to 0.66 | |

| General Surgery | 0.93 | 0.320 | 0.80 to 1.08 | |

| Gynaecology/gynaecological oncology | 1.01 | 0.920 | 0.80 to 1.29 | |

| Other | 0.75 | 0.005 | 0.61 to 0.92 | |

| Nephrostomy performed at provider with radiotherapy unit | 1.06 | 0.248 | 0.96 to 1.16 | |

p values < 0.001 are in bold.

IMDIndex of Multiple Deprivation

Complications of nephrostomy

2650 (24.2%) patients had at least one direct complication of nephrostomy. The most common complication was an early exchange of nephrostomy in 1365 (12.5%) patients, followed by bleeding in 885 (8.1%) and pyelonephritis in 729 (6.7%). In patients with an early exchange of nephrostomy, the median time to exchange was 10 days (IQR 5–25).

Discussion

This study has identified high mortality within 30 days of nephrostomy in the context of MUO in metastatic malignancy, particularly in patients during an emergency admission; with the majority of such patients dying as an inpatient. This study did not include locally advanced non-metastatic cancers, wherein a significant proportion of patients will have renal decompression. Survival for patients with MUO has been estimated to be between 3 and 7 months following diagnosis.5 This study identified a median survival of 4 months, indicating that insertion of a nephrostomy in this particular cohort of patients does not necessarily prolong life; this poor survival is in spite of improving biochemical renal function.6 Survival was markedly lower in patients not going on to have further treatment with chemotherapy or surgery.

Less than half of patients with MUO have an increased quality of life as a result of nephrostomy.6 Furthermore, if a nephrostomy is sited, it is estimated that patients spend 20% of their remaining lifetime as an inpatient in hospital7; with patients spending 14 days in hospital just for the nephrostomy itself.8 The majority of patients, despite nephrostomy or another modality of urinary diversion, have persisting symptoms from their cancer.9 Therefore, the insertion of percutaneous nephrostomy appears to have limited positive impact on length and quality of life, without commensurate symptom relief for this cohort of patients.

Complications from percutaneous urinary diversion should not be underestimated. Almost one in four patients in this study had a direct complication of nephrostomy insertion; delayed complications were not captured in this study and may reveal a higher rate. While most adverse effects pertain to displacement or blockage of drainage tubes, severe infection and bleeding can occur; almost half of patients may experience at least a single episode of pyelonephritis.10 Migration and extrusion of nephrostomy tubes can sometimes impact on the complex care needs of patients with external urinary drainage and emphasises the importance of fixation of the nephrostomy tubes to the skin. Furthermore, only 1 in 10 patients had a chance of internalisation of renal drainage, with an antegrade stent, further burdening patients and community care services.

Given that there is no extended survival or symptomatic improvement, nephrostomy is only indicated in circumstances to facilitate effective treatment, radical or palliative. A large proportion of patients with MUO receive no additional therapy beyond renal decompression.11 12

There have been a number of studies that have aimed to develop a prognostic model for predicting poor outcomes following nephrostomy for patients with ureteric obstruction secondary to malignant disease,13,17 considering both clinical presentations as well as biochemical parameters. While there is some overlap between factors in the studies identified, there is no consistently examined group of factors; hence there is no single approved risk prediction strategy in place at present. This highlights the complexity of decision-making for such patients and the importance of multidisciplinary cancer team input with individualised care plans for all such patients. We believe there is an urgent need for comprehensive prospective real-world data to better evaluate this clinical challenge.

Patients receiving nephrostomy as an inpatient, particularly in emergency settings, have a higher likelihood of dying within 30 days and are less likely to receive subsequent surgery or chemotherapy. Nephrostomy is performed by interventional radiology and requested by a wide variety of inpatient teams. Therefore, inpatient teams with limited experience of urinary diversion and complex oncological disease may be requesting nephrostomy insertion. It should be noted that only 1 in 10 patients had outpatient nephrostomy, yet half of these patients went on to receive chemotherapy. This is indicative of the improved outcomes in patients with planned procedures. Given that this study has identified that patients wait several days for nephrostomy in emergency settings; there is time for these patients to be discussed in a multidisciplinary cancer team meeting setting or in the context of a best interests meeting, to prevent patients undergoing futile procedures.

The volume of procedures at provider level can impact the outcomes of procedures in patients with poor prognosis cancers. For example, Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatograpy (ERCP) performed in the context of un-resectable cancer was associated with 30-day mortality in low volume providers,18 but no volume effect was seen in this study. The volume of cancer patients treated by a provider was used as a surrogate for experience in nephrostomy decision-making. Patients are regularly referred between hospital providers for nephrostomy insertion in the UK as interventional radiology services may be limited outside of tertiary care settings, particularly outside of normal working hours. No volume effect was observed in this study; this may be due to the fact that in HES we cannot be entirely sure which centre took the decision to site a nephrostomy.

Adequate counselling of patients, and by extension, consent prior to any intervention is paramount, underscored by the Montgomery ruling.19 Not only should risks, with the inclusion of impaired quality of life, be explained in detail, but comprehensive discussions must include adequate information pertaining to alternatives. This should not discount ‘doing nothing’ as an option, given the relatively short postnephrostomy life expectancy we have demonstrated. Individual disciplines managing patients with MUO in the acute setting are not necessarily equipped with the knowledge or skillset to manage this complex scenario. Despite several descriptions, heterogeneous cohorts and retrospective analyses mean that the existing data does not adequately inform discussions.20 This is also compounded by differing approaches that urologists and oncologists are likely to take21 and the potential for patients (and family) to be overwhelmed to the extent that it impairs decision-making.22 This is a complex process in a vulnerable patient group, where the default of simply decompressing the ‘obstructed urinary tract’ is no longer acceptable and a ‘realistic medicine’23 approach should be considered.

The main strengths of this study are that this was a nationwide sample of all patients undergoing nephrostomy for MUO and it is very unlikely that such procedures would be undertaken in the independent sector outside the NHS, and therefore, nearly all cases were captured. This makes the cohort characteristic of a real-world population. Further to this, the power of the study is high, as indicated by the narrow CIs and inferences can be made with more confidence. Importantly, data, in particular routine administrative data, in England is of extremely high quality. HES data pertaining to such procedures have been validated previously.24 However, there are a number of limitations to this study. As HES data are primarily administrative, there are no biochemical or histopathological data available, preventing a clear understanding of indication for nephrostomy. Furthermore, patients cannot be identified, therefore, qualitative research regarding quality of life cannot be undertaken. Multidisciplinary cancer team outcome data cannot be reviewed to examine the predicted prognosis or whether the patient was already considered for palliative care at time of nephrostomy; additionally, whether the decision was ratified by the multidisciplinary team. Although this study provides a picture of outcomes for this cohort of patients, it is not possible to control for all potential confounding variables.

Conclusions

Large numbers of patients undergo nephrostomy with no further treatment, with a significant proportion experiencing death within a short time frame and a high complication rate. The decision to perform nephrostomy in such patients is a complex one and should be reviewed in a multidisciplinary cancer team setting, with surgical, oncological and palliative care input. In acute inpatient settings, it should be discussed with expert teams, should a multidisciplinary cancer team meeting not be available within the required timeframe. Care must be taken to adequately counsel and inform patients of the advantages of nephrostomy in the context of such a poor prognosis.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Contributors: PP is the guarantor.

Ethics approval: HES data are available under a data sharing agreement with NHS Digital for the purposes of service evaluation and as such ethics approval is not required. Under the data sharing agreement with NHS digital, publication of data items that aggregate to <6 at a patient level is not permitted to protect patient confidentiality and is censored in this paper. This study had local institution approval.

Contributor Information

Amandeep Dosanjh, Email: amandeeprsdosanjh@gmail.com.

Benjamin Coupland, Email: ben.coupland@uhb.nhs.uk.

Jemma Mytton, Email: jmytton1@hotmail.co.uk.

Dominic Stephen King, Email: dominic.king@nhs.net.

Harriet Mintz, Email: hxm074@student.bham.ac.uk.

Anna Lock, Email: anna.lock@nhs.net.

Veronica Nanton, Email: V.Nanton@warwick.ac.uk.

Param Mariappan, Email: Param.Mariappan@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Nigel Trudgill, Email: nigel.trudgill@nhs.net.

Prashant Patel, Email: p.patel@bham.ac.uk.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.Tabib C, Nethala D, Kozel Z, et al. Management and treatment options when facing malignant ureteral obstruction. Int J Urol. 2020;27:591–8. doi: 10.1111/iju.14235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravantinos E, Anagnostou T, Karatzas AD, et al. Percutaneous nephrostomy in patients with tumors of advanced stage: treatment dilemmas and impact on clinical course and quality of life. J Endourol. 2007;21:1297–302. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuttall M, van der Meulen J, Emberton M. Charlson scores based on ICD-10 administrative data were valid in assessing comorbidity in patients undergoing urological cancer surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouba E, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS. Management of ureteral obstruction due to advanced malignancy: optimizing therapeutic and palliative outcomes. J Urol. 2008;180:444–50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson JR, Urwin GH, Stower MJ. The role of percutaneous nephrostomy in malignant ureteric obstruction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:21–4. doi: 10.1308/1478708051432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong L-M, Cleeve LK, Milner AD, et al. Malignant ureteral obstruction: outcomes after intervention. Have things changed? J Urol. 2007;178:178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan A, Morris M, Parry MG, et al. Interventions for obstructive uropathy in advanced prostate cancer: a population-based study. BJU Int. 2022;130:688–95. doi: 10.1111/bju.15766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shekarriz B, Shekarriz H, Upadhyay J, et al. Outcome of palliative urinary diversion in the treatment of advanced malignancies. Cancer. 1999;85:998–1003. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990215)85:4<998::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alma E, Ercil H, Vuruskan E, et al. Long-term follow-up results and complications in cancer patients with persistent nephrostomy due to malignant ureteral obstruction. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:5581–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05662-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunawan B, Foster K, Hardy J, et al. Survival following palliative percutaneous nephrostomy tube insertion in patients with malignant ureteric obstruction: validating a prognostic model. Progress in Palliative Care. 2022;30:21–8. doi: 10.1080/09699260.2021.1905145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkard SS, Banerjee S, Menzies-Wilson R, et al. Percutaneous nephrostomy in obstructing pelvic malignancy does not facilitate further oncological treatment. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52:1625–8. doi: 10.1007/s11255-020-02466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alawneh A, Tuqan W, Innabi A, et al. Clinical factors associated with a short survival time after percutaneous nephrostomy for ureteric obstruction in cancer patients: an updated model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordeiro MD, Coelho RF, Chade DC, et al. A prognostic model for survival after palliative urinary diversion for malignant ureteric obstruction: a prospective study of 208 patients. BJU Int. 2016;117:266–71. doi: 10.1111/bju.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishioka J, Kageyama Y, Inoue M, et al. Prognostic model for predicting survival after palliative urinary diversion for ureteral obstruction: analysis of 140 cases. J Urol. 2008;180:618–21. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lienert A, Ing A, Mark S. Prognostic factors in malignant ureteric obstruction. BJU Int. 2009;104:938–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Group SMS Predicted survival of patients following intervention (ureteric stent or nephrostomy) for malignant ureteric obstruction. https://webapps.igc.ed.ac.uk/world/research/muo_calculator/ n.d. Available.

- 18.Harvey PR, Baldwin S, Mytton J, et al. Higher volume providers are associated with improved outcomes following ERCP for the palliation of malignant biliary obstruction. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;18:100212. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Kingdom Supreme Court Montgomery (appellant) V Lanarkshire health board (respondent) (Scotland). 2015. 2015.

- 20.Prentice J, Amer T, Tasleem A, et al. Malignant ureteric obstruction decompression: how much gain for how much pain? A narrative review. J R Soc Med. 2018;111:125–35. doi: 10.1177/0141076818766725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyams ES, Shah O. Malignant extrinsic ureteral obstruction: a survey of urologists and medical oncologists regarding treatment patterns and preferences. Urology. 2008;72:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bester J, Cole CM, Kodish E. The limits of informed consent for an overwhelmed patient: clinicians' role in protecting patients and preventing overwhelm. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18:869–86. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.9.peer2-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eggers MJ, Doyle JT, Lefthand MJ, et al. Community engaged cumulative risk assessment of exposure to inorganic well water contaminants, crow reservation, Montana. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:76. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mintz HP, Dosanjh A, Parsons HM, et al. Development and validation of a follow-up methodology for a randomised controlled trial, utilising routine clinical data as an alternative to traditional designs: a pilot study to assess the feasibility of use for the BladderPath trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020;6:165. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.