Abstract

MnO2 nanowires coated with conjugated microporous polymers (CMP) are applied as triboelectric energy harvesting materials. The tribopositive performance of the CMP shells is enhanced with the assistance of MnO2 nanowires (MnO2 NW), likely due to cationic charge transfer from the tribopositive CMP layers to the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW. This is supported by model studies. The MnO2@CMP‐2 with sub‐10 nm thick CMP layers shows promising triboelectric output voltages up to 576 V and a maximum power density of 1.31 mW cm−2. Spring‐assisted triboelectric nanogenerators fabricated with MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 films are used as power supplies to operate electronic devices.

Keywords: conjugated microporous polymer, manganese dioxide, nanowire, triboelectric material, triboelectric nanogenerator

MnO2@CMP nanowires show promising triboelectric performance. The possible cationic charge transfer from tribopositive CMP shells to the surface Mn2+/Mn3+ species of MnO2 nanowires is proposed as a mechanistic principle. TENGs fabricated with a MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film show the output peak‐to‐peak voltage of 576 V and a maximum power density of 1.31 mW cm−2.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, research on small‐scale energy harvesting and utilization has gained considerable significance.[ 1 ] For instance, triboelectric energy in everyday life can be harvested and utilized for various purposes.[ 2 ] Since the Wang group developed triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs),[ 3 ] extensive research has focused on fabricating new devices.[ 4 ] In addition, to improve the efficiency of TENGs, extensive studies have been conducted on triboelectric materials.[ 5 ]

As triboelectric energy harvesting materials, various organic polymers have been studied.[ 6 ] In addition, the surface areas and electronic properties of polymers have been tuned to enhance their triboelectric performance.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] For example, microporous organic materials with high surface areas have been studied for engineering TENGs.[ 7 , 8 ] As a class of microporous organic materials, conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs) have been prepared by the coupling of organic building blocks.[ 10 ] Recently, our research group reported that CMPs can be used as promising tribopositive materials for harvesting triboelectric energy.[ 11 ]

On the other hand, porous organic polymer‐inorganic composites have been studied to achieve enhanced triboelectric performance.[ 12 ] The triboelectrification performance of organic polymers can be enhanced with the assistance of inorganic nanomaterials. While organic polymer materials offer advantages in facile chemical engineering, inorganic nanomaterials can provide additional benefits such as facilitating redox reactions.

Recently, MnO2 nanomaterials have been utilized as energy storage materials in pseudocapacitors.[ 13 ] The morphology of MnO2‐based nanomaterials has been engineered into nanowires. Usually, the surface of MnO2 nanowires has an amorphous character and consists of Mn2+ and Mn3+ species,[ 14 ] which can be further oxidized to Mn4+ species by donating electrons.

It can be speculated that core–shell MnO2@CMP nanowires can be engineered to enhance the tribopositive performance of CMP materials with the assistance of surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species in the inner MnO2 nanowires. When preparing MnO2@CMP nanowires, we observed the facile generation of static electricity in a Falcon plastic tube (Figure S1 and Movie S1, Supporting Information). In this work, we report the preparation of MnO2@CMP nanowires and their enhanced triboelectric performance, compared to the corresponding MnO2 and CMP materials.

2. Results and Discussion

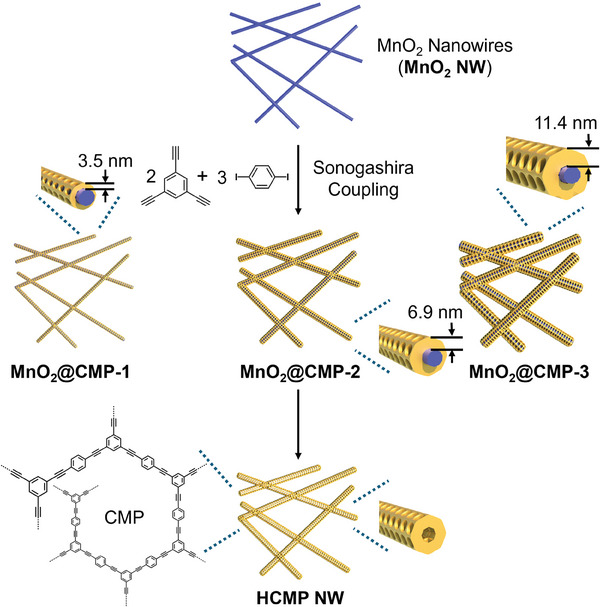

Figure 1 displays the synthetic scheme of MnO2@CMP nanowires.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of MnO2@CMP nanowires and HCMP nanowires (HCMP NW).

First, MnO2 nanowires (MnO2 NW) were prepared by reacting KMnO4 with H2O2 in acetic acid.[ 15 ] Through the Sonogashira coupling of 1,3,5‐triethynylbenzene with 1.5 eq. 1,4‐diiodobenzene in the presence of MnO2 NW, CMP layers were formed on the MnO2 NW. With a fixed amount of MnO2 NW (0.20 g), the amount of 1,3,5‐triethynylbenzene was gradually increased from 0.10 to 0.20 and 0.40 mmol to form three different MnO2@CMP nanowires (denoted as MnO2@CMP‐1, MnO2@CMP‐2, and MnO2@CMP‐3, respectively). As control materials, the inner MnO2 of MnO2@CMP‐2 was etched by treating with HCl to form hollow CMP nanowires (HCMP NW).

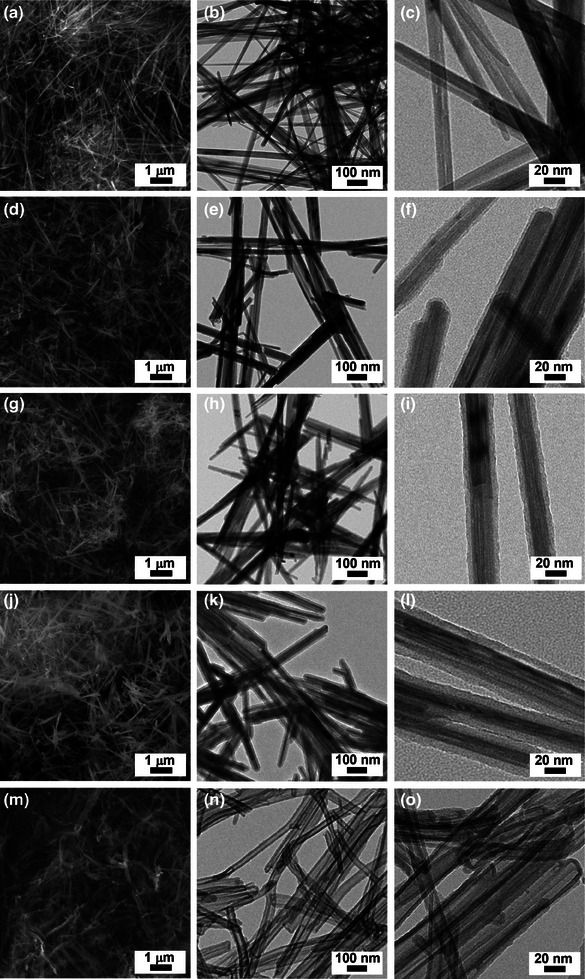

The morphologies of materials were examined using scanning (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 2 ). The SEM and TEM images of MnO2 NW revealed long nanowires with a thickness of 15–25 nm and a length of 2–5 µm (Figure 2a–c). While MnO2@CMPs retained wire‐like morphologies (Figure 2d,e,g,h,j,k), a closer inspection revealed a thin coating of CMP on the surface of MnO2 NW (Figure 2f,i,l). The coating thicknesses of CMPs in MnO2@CMP‐1, MnO2@CMP‐2, and MnO2@CMP‐3 were measured to be 3.5 ± 0.4, 6.9 ± 0.7, and 11.4 ± 0.7 nm, respectively (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Whilst the SEM images of HCMP NW showed wire‐like morphologies, the empty inner space could be confirmed by TEM analysis (Figure 2m–o).

Figure 2.

SEM and TEM images of (a,b,c) MnO2 NW, (d,e,f) MnO2@CMP‐1, (g,h,i) MnO2@CMP‐2, (j,k,l) MnO2@CMP‐3, and (m,n,o) HCMP NW.

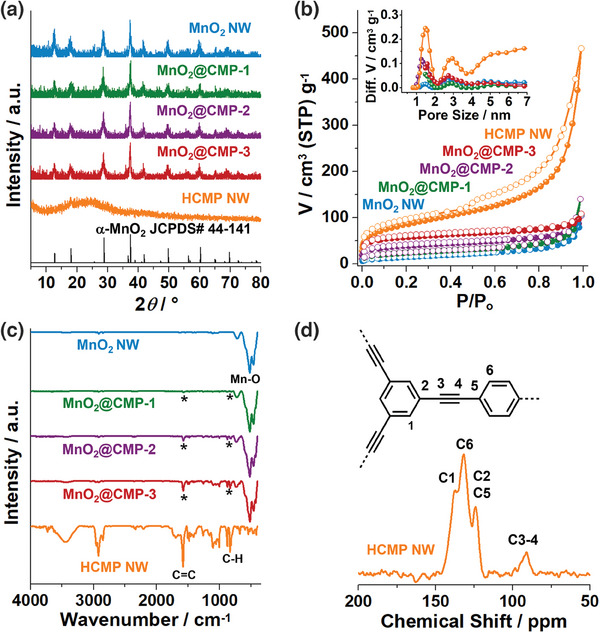

The chemical and physical features of materials were investigated using various analytical techniques (Figure 3 ). Powder X‐ray diffraction (PXRD) studies on MnO2 NW and MnO2@CMPs showed diffraction peaks at 12.5°, 17.9°, 28.6°, 37.5°, 41.6°, 50.0°, 60.3°, and 69.6°, corresponding to the (110), (200), (310), (211), (301), (411), (521), and (541) crystalline planes of α‐MnO2 (JCPDS# 44–141) (Figure 3a).[ 16 ] In comparison, HCMP NW exhibited an amorphous feature, which is a conventional characteristic of CMPs in the literature.[ 17 ]

Figure 3.

a) PXRD patterns, b) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm curves obtained at 77 K and pore size distribution diagrams based on the NL‐DFT method, c) IR spectra of MnO2 NW, MnO2@CMPs, and HCMP NW. d) A solid‐state 13C NMR spectrum of HCMP NW.

N2 sorption studies were conducted to investigate the surface areas and porosity of materials (Figure 3b). The analysis of N2 sorption isotherm curves based on the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory indicated that the MnO2 NW has a surface area of 54 m2 g−1 and poor porosity. In comparison, the HCMP NW showed a high surface area of 310 m2 g−1 and microporosity (pore sizes < 2 nm) with a total pore volume (Vt) of 0.46 cm3 g−1. As the amount of CMPs increased in the MnO2@CMPs, the surface areas gradually increased from 85 m2 g−1 (MnO2@CMP‐1) to 138 (MnO2@CMP‐2) and 207 m2 g−1 (MnO2@CMP‐3) with the increase of Vt from 0.11 cm3 g−1 to 0.12 and 0.13 cm3 g−1, respectively.

The infrared (IR) absorption spectra of MnO2 NW and MnO2@CMPs revealed broad peaks at 460–520 cm−1, corresponding to Mn─O vibrations (Figure 3c).[ 18 ] In comparison, HCMP NW showed aromatic C═C and C─H vibration peaks at 1581 and 837 cm−1, respectively, in addition to the C─O vibration at 1010–1105 cm−1, which was generated through the oxidation of CMP by MnO2 at the interfaces.[ 19 ] As expected, as the amount of CMP increased in MnO2@CMPs, the corresponding vibration peaks of CMPs gradually increased (indicated by asterisks in Figure 3c). A solid‐state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of HCMP NW exhibited alkyne and aromatic carbon peaks at 91 and 124–138 ppm, respectively, consistent with the CMPs reported in the literature (Figure 3d).[ 20 ]

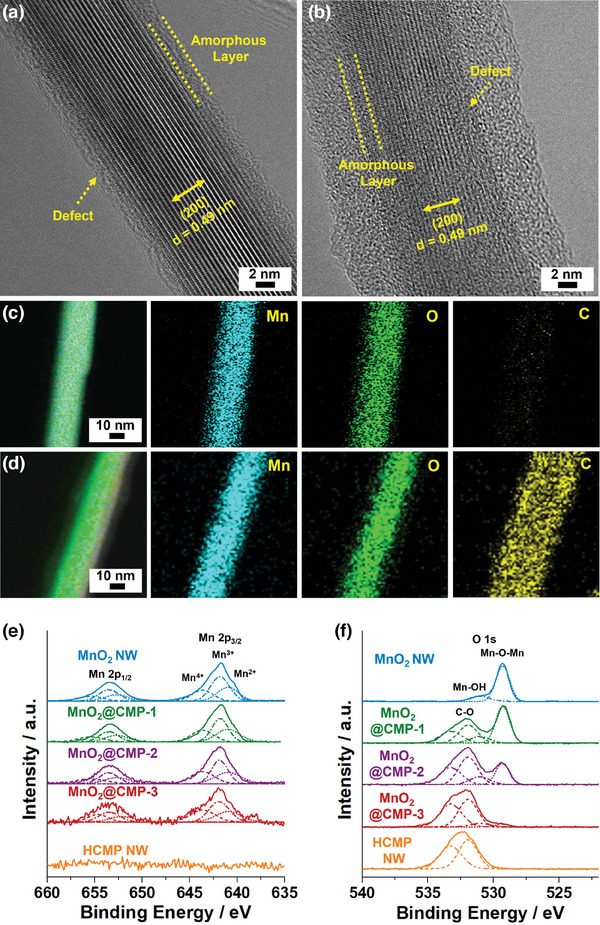

The high‐resolution (HR)‐TEM analysis of MnO2 NW and MnO2@CMP‐2 showed a crystalline inner part showing the (200) crystal plane of α‐MnO2 with an interlayer distance of 0.49 nm (Figure 4a,b).[ 21 ] The surface (a depth of ≈1.8 nm) of MnO2 NW displayed amorphous and defective features (indicated by dotted lines in Figure 4a,b). The MnO2@CMP‐2 showed the additional coating of amorphous CMP materials on the MnO2 NW (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

HR‐TEM images of a) MnO2 NW and b) MnO2@CMP‐2. EDS elemental mapping images of c) MnO2 NW and d) MnO2@CMP‐2. e,f) XPS Mn 2p and O 1s orbital peaks of MnO2 NW, MnO2@CMPs, and HCMP NW with normalized intensities (Refer to Figure S3, Supporting Information for unnormalized ones).

Energy dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDS)‐based elemental mapping studies of MnO2 NW showed homogeneous distributions of Mn and O elements (Figure 4c). In comparison, MnO2@CMP‐2 showed a homogeneous distribution of carbon elements on the surface of MnO2 NW, indicating a successful coating of CMP (Figure 4d).

The chemical surroundings of materials were investigated by X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The XPS Mn 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbital peaks of MnO2 NW and MnO2@CMPs were analyzed into three sets (Figure 4e; Figures S3 and S4, Supporting Information). Whilst the Mn 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbital peaks of Mn2+ species appeared at 641.0 and 652.7 eV, respectively, those of Mn3+ species appeared at 641.8 and 653.5 eV, respectively.[ 22 ] In comparison, those of Mn4+ species were observed at 643.7 and 655.4 eV, respectively.[ 22 ] The ratios of Mn4+/(Mn2++Mn3+) of MnO2 NW, MnO2@CMP‐1, MnO2@CMP‐2, and MnO2@CMP‐3 were analyzed to be 0.31, 0.38, 0.42, and 0.44, respectively. These observations indicate that the surface of MnO2 NW consists of defective Mn2+ and Mn3+ species. The O 1s orbital spectrum of MnO2 NW showed two peaks at 529.3 and 530.3 eV, corresponding to the Mn─O─Mn and Mn─OH species, respectively (Figure 4f; Figures S3 and S5, Supporting Information).[ 23 ] The O 1s orbital spectra of MnO2@CMPs and HCMP NW showed additional peaks at 531.9 and 533.2 eV, corresponding to C─O species that were generated through oxidation of CMP by MnO2 at the interfaces.[ 24 ]

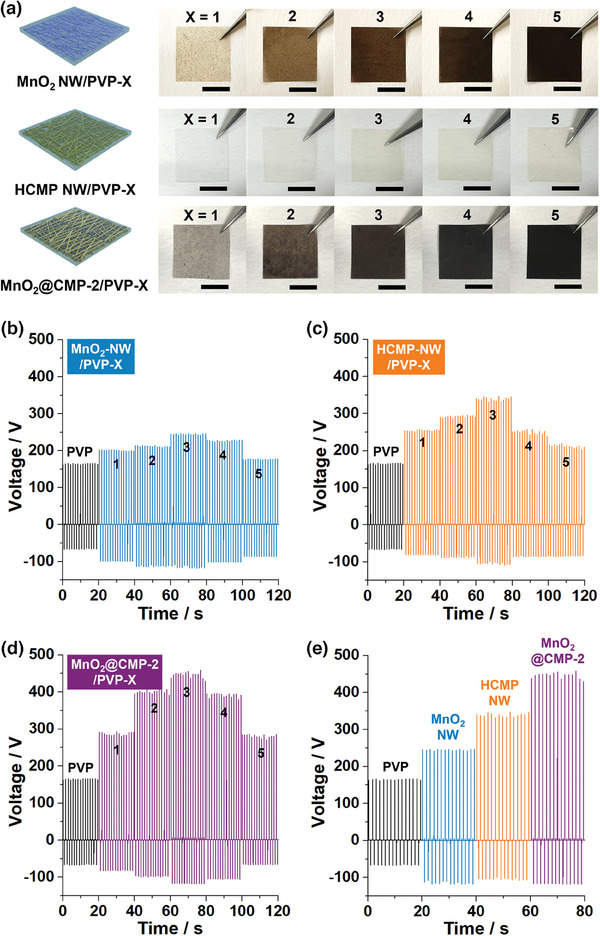

To study triboelectric performance, the films of materials were fabricated using polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a matrix (Figure 5a and refer to Experimental Section in the Supporting Information). First, five MnO2 NW/PVP films containing 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 wt.% MnO2 NW were fabricated (corresponding films were denoted as MnO2 NW/PVP‐1–5, respectively). As the amount of MnO2 NW increased, the brown color of the films became more intense (Figure 5a). According to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), the content of MnO2 NW in MnO2@CMP‐2 was analyzed to be 72 wt.% (Figure S6, Supporting Information). Considering the information, five brown MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP films containing 1.4, 4.2, 6.9, 9.7, and 13.9 wt.% MnO2@CMP‐2 (corresponding to 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 wt.% MnO2 NW and 0.4, 1.2, 1.9, 2.7, and 3.9 wt.% CMP‐2, respectively) were fabricated and denoted as MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1–5, respectively. In addition, five pale yellow HCMP NW/PVP films containing 0.4, 1.2, 1.9, 2.7, and 3.9 wt.% HCMP NW were fabricated and denoted as HCMP NW/PVP‐1–5, respectively.

Figure 5.

a) Photographs of MnO2 NW/PVP‐1–5, HCMP NW/PVP‐1–5, and MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1–5 films (scale bars: 1 cm). Triboelectric output voltages of b) MnO2 NW/PVP‐1–5, c) HCMP NW/PVP‐1–5, d) MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1–5 films. e) Comparative display of the output voltages of PVP, MnO2 NW/PVP‐3, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3, and HCMP NW/PVP‐3 films (a working area of 2 cm × 2 cm, pushing force of 2 kgf, pushing frequency of 0.73 Hz, RH 50%, PFA as a tribonegative material. Refer to Figure S11 (Supporting Information) for the output currents of corresponding films.

While the top view SEM images of MnO2 NW/PVP‐1–2, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1–2, and HCMP NW/PVP‐1–2 films exhibited flat surfaces, MnO2 NW, MnO2@CMP‐2, and HCMP materials were detected in the MnO2 NW/PVP‐3–5, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3–5, and HCMP NW/PVP‐3–5 films (Figure S7, Supporting Information). The thicknesses of MnO2 NW/PVP, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP, and HCMP NW/PVP films were measured to be 25 µm (Figure S8, Supporting Information). The IR spectra of films showed exclusively the C─H, C═O, C─N, and C─O vibration peaks of the PVP matrix at 2891–2957, 1659, 1450, and 1283 cm−1, respectively,[ 25 ] due to the relatively small amount of MnO2 NW, MnO2@CMP‐2, and HCMP in the films (Figure S9, Supporting Information). While the PXRD patterns of MnO2 NW/PVP‐1, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1, and HCMP NW/PVP‐1–5 films showed broad diffraction peaks at 2θ of 10.3° and 20.7°, corresponding to the PVP matrix,[ 26 ] those of MnO2 NW/PVP‐2–5 and MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐2–5 films revealed the original diffraction peaks of α‐MnO2 (Figure S10, Supporting Information).

The triboelectric performance of MnO2 NW/PVP, MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP, and HCMP/PVP films with an area of 2 cm × 2 cm was studied (Figure 5b–e; Figure S11, Supporting Information). As a tribonegative material, perfluoroalkoxy alkanes (PFA) were used.[ 27 ] In the case of pristine PVP and MnO2 NW/PVP films, as the amount of MnO2 NW increased, the output peak‐to‐peak voltages (Vp‐p) gradually increased from 234 V (PVP) to 302 (MnO2 NW/PVP‐1), 329 (MnO2 NW/PVP‐2), and 365 V (MnO2 NW/PVP‐3), respectively (Figure 5b). The corresponding output currents (Ip‐p) increased from 16.8 µA (PVP) to 21.1 (MnO2 NW/PVP‐1), 24.3 (MnO2 NW/PVP‐2), and 26.0 µA (MnO2 NW/PVP‐3), respectively (Figure S11, Supporting Information). Then, the Vp‐p of MnO2 NW/PVP‐4 and MnO2 NW/PVP‐5 films decreased to 331 and 265 V, respectively, with a decrease of Ip‐p to 24.1 and 19.6 µA. In the case of HCMP NW/PVP films, as the amount of HCMP NW increased, Vp‐p gradually increased from 339 V (HCMP NW/PVP‐1) to 385 (HCMP/PVP‐2) and 456 V (HCMP/PVP‐3) with an increase of Ip‐p from 23.8 to 25.9 and 31.7 µA (Figure 5c; Figure S11, Supporting Information). Then, the Vp‐p of HCMP NW/PVP‐4 and HCMP NW/PVP‐5 films decreased to 359 and 306 V, respectively, with a decrease of Ip‐p to 25.8 and 21.4 µA.

In comparison, as the amount of MnO2@CMP‐2 increased, Vp‐p significantly increased from 375 V (MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐1) to 507 (MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐2) and 576 V (MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3) with an increase of Ip‐p from 25.9 to 36.1 and 39.6 µA (Figure 5d; Figure S11, Supporting Information). Then, the Vp‐p of MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐4 and MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐5 films decreased to 359 and 306 V, respectively, with a decrease of Ip‐p to 36.1 and 24.4 µA. These observations indicated that the MnO2 NW/PVP‐3, HCMP NW/PVP‐3, and MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 are the best films. Among these films, the triboelectric performance was gradually enhanced in the order of MnO2 NW/PVP‐3 < HCMP NW/PVP‐3 < MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 (Figure 5e).

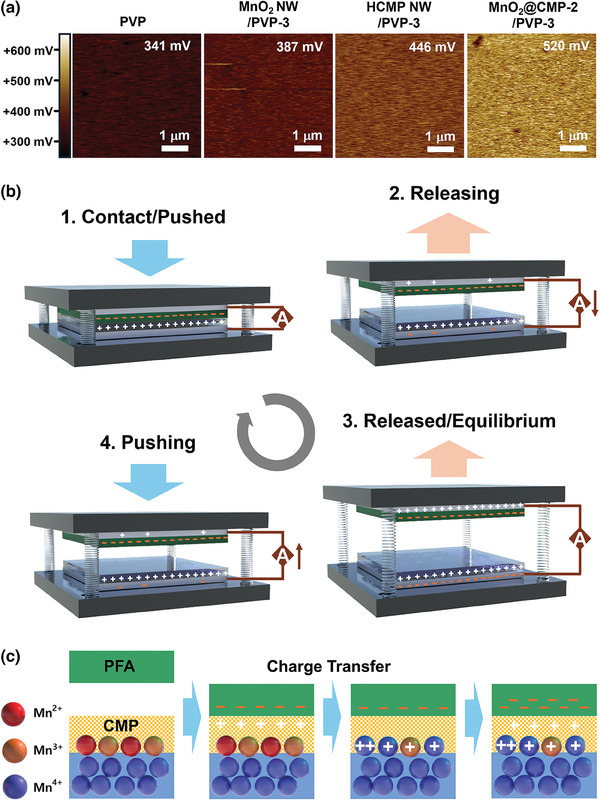

According to Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM), the surface potentials gradually increased from 341 mV (PVP) to 387 (MnO2 NW/PVP‐3), 446 (HCMP NW/PVP‐3), and 520 mV (MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3), matching with the observed trend of the tribopositive performance of films (Figure 6a). The mechanism of electricity generation through triboelectrification has been reported in the literature (Figure 6b).[ 28 ] At the contact of the pressed two films, electrons transfer from the tribopositive MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film to the tribonegative PFA film. In the releasing state, electrons flow from the supporting metal electrode of a PFA film to the supporting metal electrode of an MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film, reaching an equilibrium state. During the re‐pushing state of two films, electrons flow back from the supporting metal electrode of an MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film to the supporting metal electrode of a PFA film. This process was repeated in the pushing/releasing cycles.

Figure 6.

a) KPFM images of PVP, MnO2 NW/PVP‐3, HCMP NW/PVP‐3, and MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 films. b) A mechanism of the triboelectric energy harvesting process by a tribopositive a MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP film and a tribonegative PFA film. c) A suggested mechanism of the MnO2 NW‐assisted tribopositive performance of MnO2@CMP‐2.

We propose the following mechanistic principle for the enhanced tribopositive performance of MnO2@CMP‐2 (Figure 6c). When the PFA film is in contact with MnO2@CMP‐2, electrons transfer from the tribopositive CMP to the PFA. The surface Mn2+ (indicated as red balls in Figure 6c) and Mn3+ (indicated as orange balls in Figure 6c) species can be converted to Mn4+ (indicated as blue balls in Figure 6c) through electron transfer to the CMP layers. With the assistance of the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species in MnO2 NW, the CMP layers can further enhance their role as tribopositive materials.

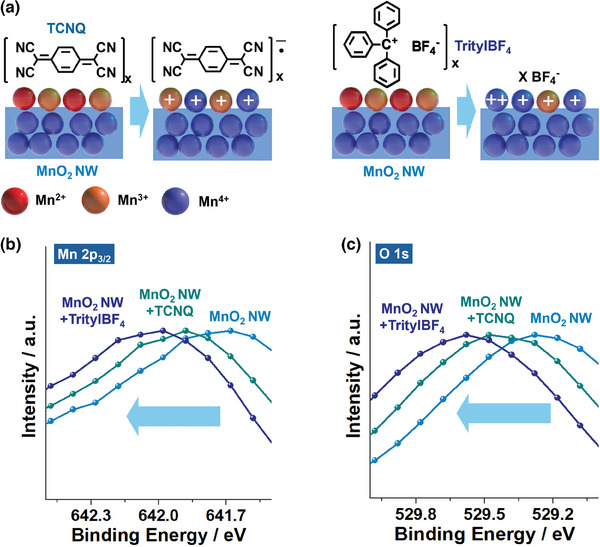

To investigate the possible redox behaviors of the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW, we conducted the following model studies (Figure 7 ; Figures S12–S14, Supporting Information). Because PFA is a polymeric material and the generation of cationic charges on CMP through triboelectrification is an instantaneous event, XPS studies on the changes of the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW are technically limited. Thus, we treated MnO2 NW with tetracyanoquinone (TCNQ), as an electron‐deficient model compound,[ 29 ] and trityl tetrafluoroborate (TritylBF4),[ 30 ] as a model carbocation (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

a) Model reactions of MnO2 NW with tetracyanoquinone (TCNQ) and trityl tetrafluoroborate (TritylBF4). XPS b) Mn 2p3/2 and c) O 1s orbital spectra of MnO2 NW with normalized intensities before and after treatment of MnO2 NW with TCNQ and TritylBF4 (Refer to Figures S12 and S13, Supporting Information for detailed analysis).

When the MnO2 NW was treated with TCNQ and TritylBF4, the XPS Mn 2p orbital peaks significantly shifted to the higher energy region by 0.21 and 0.35 eV, respectively, indicating the conversion of the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species to Mn3+ and Mn4+ species. The detailed analysis indicated an increase in the Mn4+/(Mn2+ + Mn3+) values from 0.31 to 0.42 and 0.43 after the treatment of the MnO2 NW with TCNQ and TritylBF4, respectively (Figure 7b; Figure S12, Supporting Information). In addition, the O 1s orbital peaks of Mn─O─Mn species also shifted to the higher energy region by 0.18 and 0.32 eV, respectively, indicating the increased oxidation state of Mn species (Figure 7c; Figure S13, Supporting Information). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra confirmed the generation of anionic TCNQ radicals and trityl radicals (Figure S14, Supporting Information). These observations indicate that the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW can be converted to Mn3+ and Mn4+ species through the interaction with electron‐deficient materials and carbocation species.

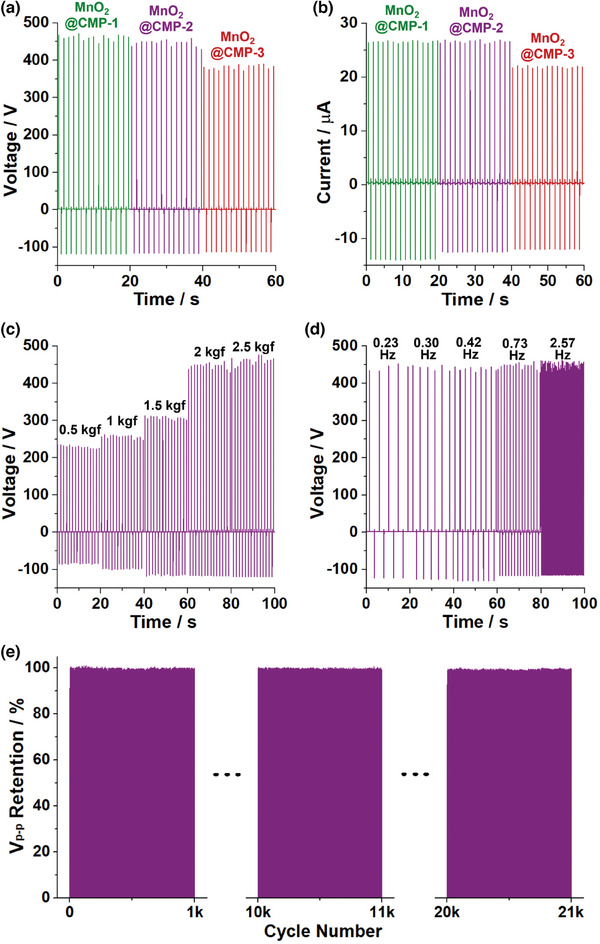

The thickness effect of CMP layers on the triboelectric performance of MnO2@CMPs was investigated (Figure 8a,b; Figure S15, Supporting Information). The MnO2@CMP‐1 with 3.5 ± 0.4 nm thick CMP layers showed slightly better triboelectric performance with Vp‐p of 590 V and Ip‐p of 40.8 µA than the MnO2@CMP‐2 with 6.9 ± 0.7 nm thick CMP layers displaying Vp‐p of 576 V and Ip‐p of 39.6 µA. In comparison, the MnO2@CMP‐3 with 11.4 ± 0.7 nm thick CMP layers showed significantly lower Vp‐p of 505 V and Ip‐p of 34.2 µA. These results indicate that the thickness of CMP layers should be sufficiently thin at a sub‐10 nm scale for efficient charge transfer to the inner MnO2 NW during the triboelectrification process.

Figure 8.

a,b) CMP layers thickness‐dependent output voltages and currents of MnO2@CMP/PVP films (Refer to Figure S15, Supporting Information for more studies). c) Pushing force and d) pushing frequency‐dependent output voltages and e) the retention of output voltages of MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film (standard working conditions: a working area of 2 cm × 2 cm, a pushing force of 2 kgf, a pushing frequency of 0.73 Hz, RH 50%). Refer to Figures S16 and S17, Supporting Information for the output currents of corresponding films.

The working condition‐dependent triboelectric performance of the MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 was investigated (Figure 8c,d; Figures S16 and S17, Supporting Information). At relative humidities (RH) of 30% and 50%, the MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 exhibited similar triboelectric performance with Vp‐p of 554 and 576 V, respectively, and Ip‐p of 39.2 and 39.6 µA, respectively (Figure S16, Supporting Information). When RH increased to 80%, the Vp‐p and Ip‐p significantly dropped to 310 V and 28.7 µA, respectively.

The triboelectric performance of MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 was sensitive to the pushing force (Figure 8c; Figure S17, Supporting Information). As the pushing forces increased from 0.5 to 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 kgf, the Vp‐p increased from 322 to 363, 431, 576, and 600 V, respectively, with an increase of Ip‐p from 22.5 to 24.6, 30.3, 39.6, and 42.0 µA. In contrast, the MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 exhibited similar triboelectric performance across a pushing frequency range of 0.23–2.57 Hz, maintaining Vp‐p of 575–576 V and Ip‐p of 39.6–39.8 µA (Figure 8d; Figure S17, Supporting Information).

The durability of MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 was studied through cycling tests (Figure 8e). At the optimized working conditions (a pushing force of 2 kgf, a pushing frequency of 0.73 Hz, RH 50%), the MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 maintained the original triboelectric performance in the range of 98.8–100% over 21 000 cycling tests.

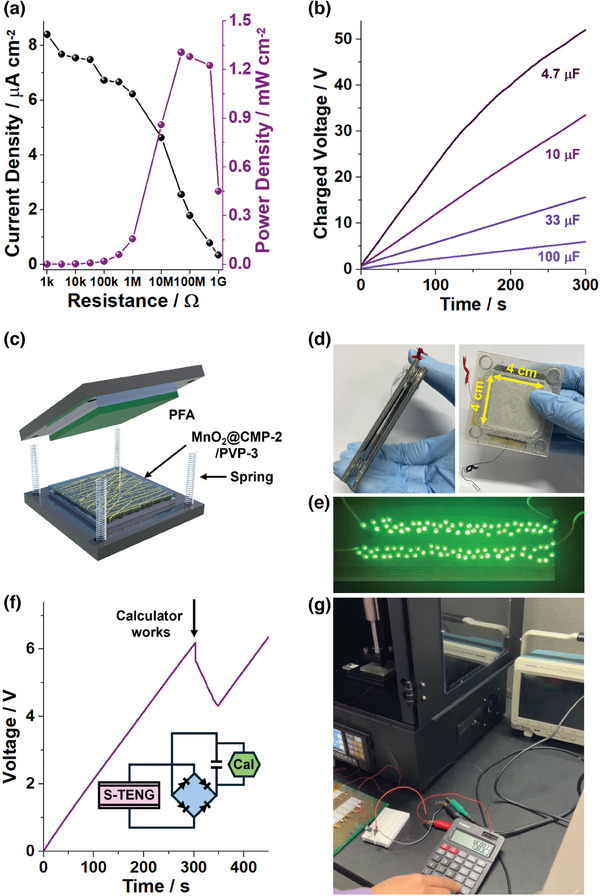

Resistance‐dependent current and power densities generated by triboelectric MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 films were measured, showing a maximum power density (Pmax) of 1.31 mW cm−2 at a resistance of 5 × 107 Ω (Figure 9a). Very recently, microporous organic materials such as covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and CMPs have been applied as triboelectric materials, showing Vp‐p of 40–815 V and Pmax of 0.364 µW cm−2–0.824 mW cm−2 (Table S1, Supporting Information).[ 8 , 11 ] In addition, metal–organic framework (MOF)‐based triboelectric materials showed the Vp‐p of 62–658 V and Pmax of 0.968 µW cm−2–0.508 mW cm−2 (Table S2, Supporting Information).[ 9 ] In this regard, the triboelectric performance of the MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film, showing Vp‐p of 576 V and Pmax up to 1.31 mW cm−2, is quite promising.

Figure 9.

a) Resistance‐dependent current and power densities (a film area of 2 cm × 2 cm, a pushing force of 2 kgf) and b) charged voltages of electrolytic capacitors by the triboelectric performance of a MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film. c) An illustration and d) a photograph of an S‐TENG fabricated using MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 and PFA films. e,f,g) Demonstration of S‐TENGs as power sources to turn on 100 green LED bulbs and to operate an electronic calculator (working conditions: a film area of 4 cm × 4 cm, a pushing force of 2 kgf, a pushing frequency of 0.73 Hz, RH 50%).

The triboelectric MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 film could be utilized to charge electrolytic capacitors (Figure 9b). After 5 min, voltages of 50, 32, 15, and 5 V were achieved for 4.7, 10, 33, and 100 µF capacitors, respectively. Spring‐assisted triboelectric nanogenerators (S‐TENGs) were fabricated using MnO2@CMP‐2/PVP‐3 and PFA films (Figure 9c,d). It was confirmed that the S‐TENG could work as a power supply to illuminate 100 green LED bulbs (Figure 9e; Movie S2, Supporting Information). Moreover, after a battery was removed from an electronic calculator, the S‐TENG was connected as a power supply. A capacitor charged to 6 V for 300 s using the S‐TENG could be used to operate a calculator (Figure 9f,g; Movie S3, Supporting Information).

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this work shows that the triboelectric performance of CMP materials can be significantly enhanced with the assistance of MnO2 NW. As a cooperative mechanistic principle for the triboelectrification of MnO2@CMP, the possible redox role of the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW was suggested. Especially, the CMP shell thickness of MnO2@CMP was also critical and should be a sub‐10 nm scale to ensure efficient tribopositive materials. Model studies supported the possible electron transfer from the surface Mn2+ and Mn3+ species of MnO2 NW to organic materials. Based on the observed results of this work, we believe that various redox‐active inorganic material@CMP systems can be developed as effective triboelectric materials.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1

Supplemental Movie 2

Supplemental Movie 3

Acknowledgements

H.J. and D.M.L. contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (Nos. RS‐2023‐00208797 and 2022R1A3B1078291) funded by the Korean government (MSIT).

Jung H., Lee D.‐M., Park J., Kim T., Kim S.‐W., Son S. U., MnO2 Nanowires with Sub‐10 nm Thick Conjugated Microporous Polymers as Synergistic Triboelectric Materials. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2409917. 10.1002/advs.202409917

Contributor Information

Sang‐Woo Kim, Email: kimsw1@yonsei.ac.kr.

Seung Uk Son, Email: sson@skku.edu.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Wang Z. L., MRS Bull. 2023, 48, 1014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng T., Shao J., Wang Z. L., Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 39. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fan F. R., Tian Z. Q., Wang Z. L., Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu D., Gao Y., Zhou L., Wang J., Wang Z. L., Nano Res. 2023, 16, 22698. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yu Y., Li H., Zhao D., Gao Q., Li X., Wang J., Wang Z. L., Cheng T., Mater. Today 2023, 64, 61. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen A., Zhang C., Zhu G., Wang Z. L., Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Shao Z., Chen J., Xie Q., Mi L., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 486, 215118; [Google Scholar]; b) Nitha P. K., Chandrasekhar A., Mater. Today Energy 2023, 37, 101393. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Zhai L., Wei W., Ma B., Ye W., Wang J., Chen W., Yang X., Cui S., Wu Z., Soutis C., Zhu G., Mi L., ACS Materials Lett 2020, 2, 1691; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhai L., Cui S., Tong B., Chen W., Wu Z., Soutis C., Jiang D., Zhu G., Mi L., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5784; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin C., Sun L., Meng X., Yuan X., Cui C. X., Qiao H., Chen P., Cui S., Zhai L., Mi L., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211601; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yao S., Zheng M., Wang S., Huang T., Wang Z., Zhao Y., Yuan W., Li Z., Wang Z. L., Li L., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2209142; [Google Scholar]; e) Hajra S., Panda J., Swain J., Kim H. G., Sahu M., Rana M. K., Samantaray R., Kim H. J., Sahu R., Nano Energy 2022, 101, 107620; [Google Scholar]; f) Shi L., Kale V. S., Tian Z., Xu X., Lei Y., Kandambeth S., Wang Y., Parvatkar P. T., Shekhah O., Eddaoudi M., Alshareef H. N., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2212891; [Google Scholar]; g) Meng N., Zhang Y., Liu W., Chen Q., Soykeabkaew N., Liao Y., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313534. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Khandelwal G., Chandrasekhar A., Raj N. P. M. J., Kim S. J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803581; [Google Scholar]; b) Guo Y., Cao Y., Chen Z., Li R., Gong W., Yang W., Zhang Q., Wang H., Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104517; [Google Scholar]; c) Khandelwal G., Raj N. P. M. J., Kim S. J., J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 17817; [Google Scholar]; d) Hajra S., Sahu M., Padhan A. M., Lee I. S., Yi D. K., Alagarsamy P., Nanda S. S., Kim H. J., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101829; [Google Scholar]; e) Huang C., Lu G., Qin N., Shao Z., Zhang D., Soutis C., Zhang Y. Y., Mi L., Hou H., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 16424; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Shaukat R. A., Saqib Q. M., Kim J., Song H., Khan M. U., Chougale M. Y., Bae J., Choi M. J., Nano Energy 2022, 96, 107128; [Google Scholar]; g) Chen Z., Cao Y., Yang W., An L., Fan H., Guo Y., J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 799; [Google Scholar]; h) Xi Q., Chen Z., Li Y., Liu F., Guo Y., A. C. S. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 5215. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee J. S. M., Cooper A. I., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park S. I., Lee D. M., Kang C. W., Lee S. M., Kim H. J., Ko Y. J., Kim S. W., Son S. U., J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 12560. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Kang C. W., Lee D. M., Park J., Bang S., Kim S. W., Son S. U., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202209659; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ghosh K., Iffelsberger C., Konečny M., Vyskočil J., Michalička J., Pumera M., Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2203476. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang X., Hirata A., Fujita T., Chen M., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Wang J., Zhang D., Nie F., Zhang R., Fang X., Wang Y., Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 15377; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang H., Wu A., Fu H., Zhang L., Liu H., Zheng S., Wan H., Xu Z., R. S. C. Adv. 2017, 7, 41228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Villegas J. C., Garces L. J., Gomez S., Durand J. P., Suib S. L., Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 1910; [Google Scholar]; b) Poyraz A. S., Laughlin J., Zec Z., Electrochim. Acta 2019, 305, 423. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davoglio R. A., Cabello G., Marco J. F., Biaggio S. R., Electrochim. Acta 2018, 261, 428. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho K., Kang C. W., Ryu S. H., Jang J. Y., Son S. U., J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 6950. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen H., Wang Y., Lv Y. K., R. S. C. Adv. 2016, 6, 54032. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ko J. H., Lee S. M., Kim H. J., Ko Y. J., Son S. U., ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jang J. Y., Kim G. H., Ko Y. J., Ko K. C., Son S. U., Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 2958. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khandare L., Terdale S., Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 418, 22. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tang Q., Fan Y. Z., Han L., Yang Y. Z., Li N. B., Luo H. Q., Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie G., Liu X., Li Q., Lin H., Li Y., Nie M., Qin L., J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 10915. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lopez G. P., Castner D. G., Ratner B. D., Surf. Interface Anal. 1991, 17, 267. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Basha M. A. F., Polymer J. 2010, 42, 728. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eisa W. H., Al‐Ashkar E., El‐Mossalamy S. M., Ali S. S. M., Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 651, 28. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim J., Ryu H., Kim S. M., Lee H. Y., Karami A., Galayko D., Kang D., Kwak S. S., Yoon H. J., Basset P., Kim S. W., Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2301309. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Z. L., ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Mullane A. P., Fay N., Nafady A., Bond A. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horn M., Mayr H., J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2012, 25, 979. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1

Supplemental Movie 2

Supplemental Movie 3

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.