Abstract

Background:

Relapse after corticosteroid withdrawal in eosinophilic esophagitis is not well understood.

Objectives:

Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) 2.0 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) was evaluated in two consecutive phase III studies (12 and 36 weeks, respectively). For clinicopathologic responders after 12 weeks of BOS treatment, we assessed randomized treatment withdrawal for up to 36 weeks of therapy.

Design:

Post hoc analysis of a phase III, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study.

Methods:

Clinicopathologic responders (⩽6 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) and ⩾30% reduction in Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) score from baseline) after 12 weeks of BOS were randomized to continue BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdraw to placebo (PBO; BOS–PBO) for up to 36 weeks. Relapsers (⩾15 eos/hpf (⩾2 esophageal regions) and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (DSQ)) could reinitiate BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. This post hoc analysis assessed a more clinically relevant relapse definition (⩾15 eos/hpf (⩾1 esophageal region) and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (DSQ)) for BOS–BOS versus BOS–PBO patients over 36 weeks. To account for BOS–PBO patients who reinitiated BOS before week 36, patients’ last observations before reinitiating BOS were carried forward (last observation carried forward (LOCF)) for histologic, symptom, and endoscopic efficacy endpoints (at weeks 12 and 36).

Results:

Of 48 patients included (BOS–BOS, n = 25; BOS–PBO, n = 23), significantly more BOS–PBO than BOS–BOS patients relapsed over 36 weeks using this post hoc relapse definition (60.9% vs 28.0%; p = 0.022). More BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients maintained histologic responses (all thresholds) and showed improvements in symptom and endoscopic efficacy endpoints.

Conclusion:

More BOS–PBO than BOS–BOS patients relapsed, determined by a more clinically relevant post hoc relapse definition. Using LOCF, more BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients also maintained or had improvements in efficacy endpoints.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers (https://clinicaltrials.gov/): NCT02605837, NCT02736409.

Keywords: budesonide oral suspension, eosinophilic esophagitis, last observation carried forward imputation, randomized treatment withdrawal

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, inflammatory condition that affects the mucosal lining of the esophagus, which can result in difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). 1 This disorder is characterized by esophageal symptoms and ⩾15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) on esophageal biopsy. 1 Existing treatment guidelines for the management of EoE provide conditional recommendations for the off-label use of proton-pump inhibitors and dietary elimination and a strong recommendation for the use of topical (swallowed/inhaled) corticosteroids.2–4

Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) 2.0 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) is a swallowed corticosteroid that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for 12-week use in pediatric and adult patients aged 11 years and older with EoE; BOS is not approved for treatment beyond 12 weeks, and additional data on long-term efficacy and safety are needed.4–9

The efficacy and safety of BOS in patients with EoE were initially assessed in two phase II studies5,6 and further evaluated in two consecutive phase III studies. The phase III studies were as follows: SHP621-301 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02605837), a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. in patients with EoE and dysphagia, 8 and SHP621-302 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02736409), a 36-week, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study of BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. in patients who completed SHP621-301. 4 During these studies, most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity, and no new safety concerns were identified.4,8

Patients who achieved a clinicopathologic response after 12 weeks of therapy with BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. during SHP621-301 were randomized to continue BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdraw to placebo (PBO; BOS–PBO) during SHP621-302. 4 Patients who did not achieve a clinicopathologic response continued to receive BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. during SHP621-302, and patients who received placebo during SHP621-301 initiated BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. during SHP621-302. 4 This study also assessed maintenance therapy with BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d., as EoE is a chronic condition that typically requires long-term therapy to manage the disease. 10 Although some studies have examined the effect of cessation of swallowed corticosteroids on relapse, there is a paucity of data on long-term therapy through randomized, placebo-controlled trials using robust methodology. 4

During the randomized withdrawal study, a highly stringent definition of clinicopathologic relapse was evaluated: ⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾2 esophageal regions (proximal, middle, and/or distal) and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) 11 ) in the 2-week period before a study visit. 4 Patients who relapsed during the randomized withdrawal study were eligible to reinitiate BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. at the next study visit in a blinded manner. 4 However, this prespecified definition of relapse does not align with the current diagnostic criteria for EoE (⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1 biopsy). 1 In addition, secondary efficacy endpoints were measured regardless of any intervening events or medication changes, such as reinitiating BOS, which could have resulted in an underestimation of the true impact of treatment withdrawal.

The impact of randomized treatment withdrawal following a response to swallowed corticosteroids in patients with EoE has not been extensively examined. This post hoc analysis therefore aimed to assess the impact of randomized withdrawal of BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. over 36 weeks in patients with EoE using a more clinically relevant relapse definition (⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1 esophageal region and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit), as well as a last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation, to better reflect patients’ treatment assignment and to account for any intervening events/medication changes during the study.

Methods

Study design and patients

Patients 11–55 years old with EoE who achieved a clinicopathologic response (⩽6 eos/hpf and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from baseline) after 12 weeks of therapy with BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. during SHP621-301 were randomized (1:1) to continue BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdraw to placebo (BOS–PBO) for up to a further 36 weeks during the randomized withdrawal study.4,8 No additional external recruitment was undertaken for the randomized withdrawal study. 4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for both studies are reported elsewhere.4,8

Patients underwent a screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) up to 4 weeks before the randomized withdrawal study, as well as at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy (Figure 1). 4 The prespecified analysis included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug during the randomized withdrawal study. 4 BOS–PBO patients who relapsed during the 36 weeks of therapy of the randomized withdrawal study were eligible to reinitiate BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. at the subsequent study visit (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design and treatment allocation.

Source: Adapted from Dellon et al. 4 © 2021 AGA Institute. Distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

aOnly patients who completed the SHP621-301 study 8 were eligible for inclusion in the randomized withdrawal study. Nonresponders (n = 106) during the SHP621-301 study and patients receiving placebo (n = 105) were not included in this post hoc analysis.

bBOS–PBO clinicopathologic responders (defined as ⩽6 eos/hpf and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from baseline after an initial 12 weeks of therapy (during SHP621-301)) who relapsed could reinitiate BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (blinded) at the subsequent visit.

c⩾30% Reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-301).

d⩾30% Reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-302).

e⩽6 eos/hpf (all available esophageal regions) and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-301).

fChange in least-squares mean of change in DSQ scores from the baseline of SHP621-302.

g⩽1, ⩽6, and <15 eos/hpf (all esophageal regions); stars denote when an EGD was performed.b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high-power field; EREFS, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score; PBO, placebo.

This article has been prepared in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 12

Analysis of relapse upon randomized treatment withdrawal

A stringent prespecified relapse definition was used during the randomized withdrawal study. 4 In this post hoc analysis, an alternative definition of relapse (⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1 esophageal region and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit) was evaluated for BOS–BOS patients compared with BOS–PBO patients. This post hoc alternative relapse definition aligns with the current histologic diagnostic threshold for EoE 2 of ⩾15 eos/hpf and may therefore represent a more clinically relevant measure of relapse compared with the highly stringent definition. For example, a patient who reported symptoms of dysphagia and had ⩾15 eos/hpf in only one esophageal region upon biopsy would not have been considered to have relapsed using the prespecified relapse definition during the randomized withdrawal study; however, were this patient to be assessed in real-world clinical practice, they would have been characterized as having relapsed. 2 To compare treatment differences in the proportions of relapsers, p values based on the one-sided Fisher’s exact test were calculated.

To provide a detailed overview of when relapse occurred before reinitiation of BOS, a Kaplan–Meier plot was used to examine time to relapse using the alternative post hoc relapse definition and time to first dysphagia symptom relapse (⩾4 days of dysphagia (DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit) for BOS–BOS patients compared with BOS–PBO patients over 36 weeks of therapy. Hazard ratios and associated two-sided 95% confidence intervals were derived from a Cox proportional hazards model. p Values comparing the treatment groups were calculated using a two-sided log-rank test.

Post hoc analysis of efficacy endpoints using LOCF

A LOCF imputation was applied post hoc. This approach accounted for data captured after reinitiating BOS. In the original evaluation of maintenance of response during the randomized withdrawal period, all efficacy endpoints were included, irrespective of treatment switching. Efficacy endpoints were based on the original treatment assignment for all patients in the full analysis set (e.g. for a BOS–PBO patient who relapsed and reinitiated BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d., efficacy data after reinitiating BOS were initially evaluated as placebo treatment; instead, during this post hoc analysis, the last observations for BOS–PBO patients while still receiving placebo were carried forward to weeks 12 and 36, as required, to ensure that efficacy data were not reported for placebo-treated patients while they were receiving BOS). This LOCF imputation therefore addressed the seven BOS–PBO patients who relapsed according to the prespecified relapse definition 4 and reinitiated BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. before week 36 of therapy. The LOCF imputation also addressed the four BOS–PBO patients who, despite not having relapsed, inadvertently received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. before week 36 of therapy. 4 This ensured that the data reflected the true treatment status, rather than considering patients as receiving placebo when they had reinitiated BOS, the latter of which may have biased the results toward a positive placebo outcome.

Efficacy endpoints included in this LOCF imputation were as follows: histologic response (thresholds of ⩽1, ⩽6, and <15 eos/hpf (across all esophageal regions)) at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy; maintenance of symptom response (⩾30% reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-301)) at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy; an additional symptom response (⩾30% reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-302)) at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy; maintenance of clinicopathologic response (⩽6 eos/hpf (all available esophageal regions) and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score (measured from the baseline of SHP621-301)) at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy; and least-squares (LS) mean of change in DSQ scores, EoE Endoscopic Reference Scores (EREFS), 13 and EoE Histology Scoring System (EoEHSS) grade and stage total score ratios (TSRs) 14 from the baseline of SHP621-302 to weeks 12 and 36 of therapy (Figure 1).

For the analysis of binary endpoints using the LOCF imputation, nominal p values were based on a one-sided Fisher’s exact test. To calculate one-sided p values for the change from baseline in DSQ scores, total EREFS, and EoEHSS TSRs, an analysis of covariance model with treatment, age group, and dietary restriction (EoEHSS TSRs only) as factors, and with baseline scores as continuous covariates, was performed.

Results

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

Overall, 48 patients (BOS–BOS, n = 25; BOS–PBO, n = 23) who underwent randomized withdrawal were included in this post hoc analysis (Figure 2). 4 Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were generally similar for patients from the BOS–BOS and BOS–PBO groups (Table 1). 4

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

aSeven patients relapsed and reinitiated BOS.

BOS, budesonide oral suspension; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; PBO, placebo.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with EoE who received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdrew to placebo (BOS–PBO) during the randomized withdrawal study and were included in the post hoc analysis.

| Demographics and clinical characteristics | BOS–BOS (n = 25) | BOS–PBO (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 36.8 (14.1) | 36.1 (11.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 14 (56.0) | 16 (69.6) |

| Female | 11 (44.0) | 7 (30.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 24 (96.0) | 22 (95.7) |

| Black or African American | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) |

| Prior therapy or procedure for EoE, n (%) | ||

| Dietary therapy | 8 (32.0) | 8 (34.8) |

| Systemic (oral) corticosteroids | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.7) |

| Fluticasone aerosol | 7 (28.0) | 6 (26.1) |

| Esophageal dilation | 9 (36.0) | 7 (30.4) |

| Concomitant medications, n (%) | ||

| Corticosteroids (inhaled/nasal) | 6 (24.0) | 3 (13.0) |

| PPIs | 22 (88.0) | 20 (87.0) |

| DSQ score, mean (SD) | ||

| SHP621-301 baseline | 29.0 (12.0) | 23.0 (14.5) |

| SHP621-302 baseline | 9.7 (10.7) | 8.3 (10.0) |

| Peak eosinophil count, eos/hpf, mean (SD) | ||

| SHP621-301 baseline | ||

| Overall | 67.6 (42.0) | 86.0 (46.6) |

| Proximal | 25.9 (25.0) | 37.7 (36.3) |

| Middle | 57.7 (43.5) | 54.9 (33.4) |

| Distal | 51.8 (30.8) | 69.4 (54.5) |

| SHP621-302 baseline | ||

| Overall | 1.3 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.8) |

| Proximal | 0.3 (1.2) | 0.2 (0.5) |

| Middle | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.9) |

| Distal | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.9) |

| Total EREFS, mean (SD) | ||

| SHP621-301 baseline | 7.4 (3.0) | 5.8 (2.5) |

| SHP621-302 baseline | 2.9 (2.8) | 2.7 (3.1) |

| EoEHSS grade TSR, mean (SD) | ||

| SHP621-301 baseline | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) |

| SHP621-302 baseline | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.1) |

| EoEHSS stage TSR, mean (SD) | ||

| SHP621-301 baseline | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) |

| SHP621-302 baseline | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.1) |

Data are reported for the baseline of SHP621-302 unless otherwise stated.

b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EoEHSS, EoE Histology Scoring System; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high-power field; EREFS, EoE Endoscopic Reference Score; PBO, placebo; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; TSR, total score ratio.

Analysis of relapse upon randomized treatment withdrawal

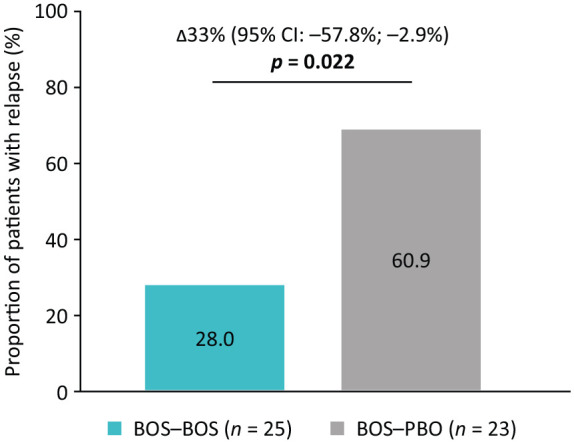

Over 36 weeks of therapy, a significantly greater proportion of BOS–PBO patients than BOS–BOS patients experienced relapse using the alternative post hoc definition of ⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1 esophageal region and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit (60.9% (14/23) vs 28.0% (7/25); p = 0.022; Figure 3). The prespecified relapse definition (⩾15 eos/hpf (⩾2 esophageal regions) and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit) measured a numerical difference between BOS–PBO patients and BOS–BOS patients (43.5% (10/23) vs 24.0% (6/25); p = 0.131). 4 The Kaplan–Meier plot of time to relapse, according to the alternative post hoc definition, demonstrated that relapse occurred significantly earlier in BOS–PBO patients than BOS–BOS patients (p < 0.01; Figure 4(a)). The median time to relapse for the BOS–PBO group (n = 13/23) was 28.14 weeks. As too few patients relapsed in the BOS–BOS group (n = 5/25) over 36 weeks of therapy, the median time to relapse could not be calculated for these patients. The Kaplan–Meier plot of time to first dysphagia symptom relapse demonstrated that a similar proportion of BOS–BOS and BOS–PBO patients experienced dysphagia symptom relapse over 36 weeks of therapy (Figure 4(b)). The median time to first dysphagia symptom relapse was also similar in the BOS–PBO group (8.43 weeks) and the BOS–BOS group (12.14 weeks; p = 0.6209).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients who received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdrew to placebo (BOS–PBO) and experienced relapse at or before week 36 of therapy using an alternative post hoc relapse definition.Reprinted from Dellon ES et al., Effect of randomized withdrawal of budesonide oral suspension on efficacy in patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis: post hoc analysis of histologic, symptom and endoscopic outcomes, 162, S-238, Copyright (2022) AGA Institute, with permission from Elsevier.

Relapse was defined as ⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1 esophageal region and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit. Patients who did not have a relapse status were excluded from this analysis. Patients were considered not to have a relapse status if they did not have data from an EGD at week 36 and did not meet the histology relapse criteria before visit 8 but met the symptom relapse criteria at visit 8. If ⩾4 days of dysphagia were reported and ⩾8 diary entries of the DSQ were recorded in the 2-week period before a study visit, the patient was considered to meet symptom relapse criteria.

b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; CI, confidence interval; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high-power field; PBO, placebo.

Figure 4.

Time to relapse (a) and time to first dysphagia symptom relapse (b) for patients who received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdrew to placebo (BOS–PBO) over 36 weeks of therapy using an alternative post hoc relapse definition.

Relapse was defined as ⩾15 eos/hpf from ⩾1 esophageal region and ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit. Dysphagia symptom relapse was defined as ⩾4 days of dysphagia (measured by the DSQ) in the 2-week period before a study visit. Patients who had missing data on relapse status were censored.

b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high-power field; PBO, placebo.

Post hoc analysis of efficacy endpoints at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy using LOCF

At week 12 of therapy, significantly more BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients achieved histologic responses using LOCF, across all thresholds (Table 2); these findings were similar to those at week 36 where significantly more BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients achieved histologic responses using LOCF (⩽1 eos/hpf: 44.0% vs 8.7%, p = 0.007; ⩽6 eos/hpf: 52.0% vs 17.4%, p = 0.013; <15 eos/hpf: 60.0% vs 21.7%, p = 0.008; Table 2). In addition, significantly more BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients achieved an additional symptom response at week 12 of therapy (Table 2). A numerically greater proportion of BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients maintained a symptom response (84.0% vs 65.2%, p = 0.121) and achieved an additional symptom response (40.0% vs 30.4%, p = 0.349) using LOCF at week 36 of therapy (Table 2). Lastly, significantly more BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients maintained a clinicopathologic response using LOCF at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy (week 12, 64.0% vs 4.3%, p < 0.001; week 36, 48.0% vs 13.0%, p = 0.010; Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints for patients who received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdrew to placebo (BOS–PBO) using LOCF in the post hoc analysis.

| Efficacy endpoints | Week 12 (LOCF imputation) | Week 36 (LOCF imputation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOS–BOS (n = 25) | BOS–PBO (n = 23) | p Value | BOS–BOS (n = 25) | BOS–PBO (n = 23) | p Value | |

| Histologic response, eos/hpf | ||||||

| ⩽1 | 15 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 | 11 (44.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.007 |

| ⩽6 | 19 (76.0) | 1 (4.3) | <0.001 | 13 (52.0) | 4 (17.4) | 0.013 |

| <15 | 19 (76.0) | 3 (13.0) | <0.001 | 15 (60.0) | 5 (21.7) | 0.008 |

| Maintenance of symptom response | ||||||

| ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from the SHP621-301 baseline | 21 (84.0) | 16 (69.6) | 0.199 | 21 (84.0) | 15 (65.2) | 0.121 |

| Additional symptom response | ||||||

| ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from the SHP621-302 baseline | 11 (44.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.007 | 10 (40.0) | 7 (30.4) | 0.349 |

| Maintenance of clinicopathologic response | ||||||

| ⩽6 eos/hpf (all available esophageal regions) and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from the SHP621-301 baseline | 16 (64.0) | 1 (4.3) | <0.001 | 12 (48.0) | 3 (13.0) | 0.010 |

Data are reported as n (%). Histologic response thresholds were achieved across all esophageal regions. Patients who had missing data were classified as nonresponders for this analysis. Statistically significant values are in bold (p < 0.05).

b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high-power field; LOCF, last observation carried forward; PBO, placebo.

The improvement from the SHP621-302 baseline to weeks 12 and 36 of therapy in DSQ scores was numerically greater for BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients using LOCF (LS mean (standard error of the mean (SEM)) of change: week 12, −0.7 (2.19) vs +1.6 (2.33), p = 0.398; week 36, −3.8 (1.94) vs −2.0 (1.98), p = 0.428; Figure 5(a) and (e)). However, neither finding was statistically significant. The improvement from the SHP621-302 baseline to week 36 of therapy in total EREFS was numerically greater for BOS–BOS patients than BOS–PBO patients in the LOCF analysis (LS mean (SEM) of change: −0.2 (0.78) vs +0.9 (0.80), p = 0.114; Figure 5(f)). However, the improvement from the SHP621-302 baseline to week 12 of therapy in total EREFS was significantly greater for BOS–BOS patients than BOS–PBO patients (LS mean (SEM) of change: −0.6 (0.63) vs +1.3 (0.68), p = 0.009; Figure 5(b)). The LS mean (SEM) of change from the SHP621-302 baseline to weeks 12 and 36 of therapy in EoEHSS grade and stage TSRs was significantly smaller for BOS–BOS than BOS–PBO patients using LOCF (week 12: grade 0.08 (0.06) vs 0.26 (0.07), p < 0.001; stage 0.09 (0.06) vs 0.25 (0.07), p < 0.001; week 36: grade 0.06 (0.07) vs 0.19 (0.08), p = 0.009; stage 0.07 (0.07) vs 0.19 (0.07), p = 0.009; Figure 5(c), (d), (g), and (h)).

Figure 5.

LS mean (SEM) of change in DSQ scores, EREFS, and EoEHSS grade and stage TSRs from the baseline of the randomized withdrawal study (SHP631-302) to weeks 12 (a–d) and 36 (e–h) of therapy for patients who received BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (BOS–BOS) or withdrew to placebo (BOS–PBO) using LOCF in a post hoc analysis.

b.i.d., twice daily; BOS, budesonide oral suspension; DSQ, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; EoEHSS, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Histology Scoring System; EREFS, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score; LOCF, last observation carried forward; LS, least-squares; PBO, placebo; SEM, standard error of the mean; TSR, total score ratio.

Further details of the prespecified analysis of efficacy endpoints at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy are presented in the Supplemental Material (Table S1 and Figure S1).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis assessed the impact of the randomized withdrawal of BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. on histologic, symptom, and endoscopic efficacy endpoints over 36 weeks in patients with EoE 4 using an alternative post hoc relapse definition and LOCF imputation. Using this alternative definition, which better aligns with current diagnostic criteria and clinical practice for EoE, 4 significantly more BOS–PBO than BOS–BOS patients relapsed. The LOCF imputation substantially improved upon the histologic, symptom, and endoscopic efficacy endpoints compared with the prespecified analysis at weeks 12 and 36, by accounting for any intervening events or medication changes during the study, thus more accurately assessing the impact of treatment withdrawal.

Although the prespecified definition of relapse was selected to align with the inclusion criteria of SHP621-301 and diagnostic guidelines for EoE at the time of study design,15,16 these management guidelines have since been updated.2,17 Therefore, it is more clinically relevant for histologic relapse to be assessed as ⩾15 eos/hpf in ⩾1, rather than ⩾2, esophageal regions. An additional five patients (BOS–PBO, n = 4; BOS–BOS, n = 1) were classified as relapsers using the alternative post hoc relapse definition versus the prespecified relapse definition, which had a meaningful impact, owing to the small randomized withdrawal population. 4 Relapse also occurred significantly earlier in BOS–PBO than BOS–BOS patients; for BOS–BOS patients, the median time to relapse was not calculable, due to the infrequency at which relapse was reported in this group. Of note, neither relapse in BOS–PBO patients nor maintenance of response in BOS–BOS patients was consistently observed over 36 weeks. The proportions of patients who experienced dysphagia symptom relapse at each time point examined were similar for BOS–PBO and BOS–BOS patients over 36 weeks; the median time to first dysphagia symptom relapse was also similar between BOS–PBO and BOS–BOS groups (8.43 and 12.14 weeks; p = 0.6209, respectively). These data demonstrate that dysphagia symptom improvements following an initial 12 weeks of therapy with BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. (SHP621-301) can be maintained, even after treatment is stopped in some patients. Although data on the randomized withdrawal of swallowed corticosteroids in EoE are limited, our post hoc alternative definition of histologic relapse has been used in other studies.18–20 A randomized withdrawal study of budesonide orodispersible tablet (BOT; 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg b.i.d.) over 48 weeks of therapy assessed a combined symptom (dysphagia score of ⩾4 using a 0–10 point numerical rating scale) and histologic (⩾15 eos/hpf (⩾1 esophageal region)) definition of relapse. 18 In that study, significantly more patients who withdrew from treatment relapsed compared with those who continued to receive treatment (60.3% for placebo, 10.3% for BOT 0.5 mg b.i.d., and 7.4% for BOT 1.0 mg b.i.d.); relapse also occurred significantly earlier in patients who withdrew to placebo than in those who continued to receive BOT at either dose. 18 In a retrospective study that evaluated the efficacy of swallowed topical corticosteroids (budesonide and fluticasone; low dose: ⩽0.5 mg every day (q.d.); high dose: >0.5 mg q.d.), in patients with EoE over a median of 2.2 years, histologic relapse (⩾15 eos/hpf) occurred in 67.1% (55/82) of patients. 20 Relapse, based on reported symptoms or the DSQ, has been investigated following discontinuation of oral viscous budesonide (1.0 mg b.i.d.) or fluticasone (880 µg b.i.d.; swallowed from a multidose inhaler) in patients with EoE. 19 Symptom recurrence was reported in 56.9% (33/58) of patients in the year following discontinuation, 19 compared with 34.8% (8/23) of BOS–PBO patients who did not maintain a symptom response over 36 weeks during our study.

As mentioned above, the LOCF imputation provided improved results for histologic, symptom, and endoscopic efficacy endpoints for BOS–BOS patients at week 36 of therapy compared with the prespecified analysis, the latter of which was confounded by patients who were considered to be placebo-treated, but who had reinitiated BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d., either following relapse or inadvertently as part of the subsequent study (SHP621-303).4,21 By accounting for this, we more accurately determined clinical outcomes following the randomized withdrawal of BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d.

A National Research Council panel report recommends minimizing the extent of missing data when making conclusions from clinical studies, 22 and an LOCF imputation can be used to account for these missing data.23–27 This approach has been used in EoE, including for BOT (1.0 mg b.i.d.)23,24 and the monoclonal antibody dupilumab (300 mg once weekly). 25 This approach has also been applied to clinical studies of budesonide (200 µg b.i.d.) 26 and dupilumab (300 mg once fortnightly) 27 for mild or moderate asthma and corticosteroid-dependent severe asthma, respectively.

Overall, 13.0% of BOS–PBO patients and 48.0% of BOS–BOS patients maintained a clinicopathologic response after up to 36 weeks of therapy, using LOCF (p = 0.010), suggesting that continued disease remission may not be guaranteed. These findings may also reinforce the need to assess the response to treatment using combined clinicopathologic assessment, rather than just monitoring histology or symptoms alone.9,10,17,18 In a study of oral viscous budesonide (1.0 mg b.i.d.) and fluticasone (880 µg b.i.d.; swallowed from a multidose inhaler), 22% of patients maintained histologic remission for up to 1 year after treatment withdrawal (<15 eos/hpf), compared with 21.7% of BOS–PBO patients at week 36 in our analysis. 17 During our study, over half of the BOS–PBO patients maintained symptom responses, despite discontinuing BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d., which is also consistent with previous data on randomized withdrawal of swallowed corticosteroids in EoE. 17

The limitations of this study include the small population size during the randomized withdrawal period, 4 which can be attributed to the study design and stringent inclusion criteria, which may have disproportionately enrolled patients with more severe baseline disease.4,8 In addition, only patients who achieved a clinicopathologic response (⩽6 eos/hpf and ⩾30% reduction in DSQ score from baseline) during SHP621-301 were eligible for the randomized withdrawal study. 4 Furthermore, EGDs with biopsies were only carried out at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy, unless patients reported symptoms that led to an unscheduled EGD; therefore, the time to histologic relapse could not be adequately evaluated. The LOCF imputation assumes that patients’ responses would remain constant throughout the study, which may have introduced either a positive or negative bias. 22 The study design may have masked the true week at which relapse occurred in some patients because an EGD was only performed at weeks 12 and 36 of therapy unless a patient reported symptoms before these time points. 4

The strengths of our study include that we used a rigorous study design 4 with validated efficacy outcome measures (the DSQ, total EREFS, and EoEHSS grade and stage TSRs), which are recommended as core outcomes in EoE.11,13,14,28 The double-blinded nature of the study enabled the objective use of a validated patient-reported outcome measure (the DSQ). The randomized withdrawal study was the first to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of BOS, a swallowed corticosteroid specifically developed for EoE. 4 The analysis described here used a more clinically relevant alternative post hoc relapse definition than the prespecified relapse definition. Using LOCF provided a more accurate assessment of the efficacy endpoints examined during the randomized withdrawal study, 4 by accounting for patients who discontinued placebo and reinitiated BOS therapy before the final evaluation at week 36 of therapy.

Conclusion

This post hoc analysis demonstrated that in patients with EoE who achieved a clinicopathologic response to an initial 12 weeks of therapy during SHP621-301, continuing BOS 2.0 mg b.i.d. for up to a further 36 weeks generally reduced the occurrence of relapse compared with randomized treatment withdrawal using the more clinically relevant alternative post hoc relapse definition. In addition, randomized treatment withdrawal may lead to histologic and dysphagia symptom relapse in some patients over 36 weeks. Furthermore, using an LOCF imputation, post hoc efficacy analyses resulted in improved findings from the prespecified analyses for histologic, symptom, and endoscopic efficacy endpoints. These data highlight the importance of maintenance therapy in patients with EoE and the need to closely monitor patients with EoE who achieve a clinicopathologic response after 12 weeks of therapy. Future studies should consider the optimal schedule for repeat endoscopy with biopsy18–20 and the use of a reliable histologic relapse definition, which aligns with the current diagnostic criteria and clinical practice, 2 as this will help to support meaningful comparisons between clinical studies evaluating treatments for EoE.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241307602 for Effect of randomized treatment withdrawal of budesonide oral suspension on clinically relevant efficacy outcomes in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a post hoc analysis by Evan S. Dellon, Margaret H. Collins, David A. Katzka, Vincent A. Mukkada, Gary W. Falk, Wenwen Zhang, Bridgett Goodwin, Brian Terreri, Mena Boules, Nirav K. Desai and Ikuo Hirano in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Tsvetana Stoilova, PhD, Joanna L. Donnelly, PhD, and Jessica Boles, PhD, of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, and funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Evan S. Dellon  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1167-1101

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1167-1101

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Evan S. Dellon, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 130 Mason Farm Road, Bioinformatics Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7080, USA.

Margaret H. Collins, Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA

David A. Katzka, Division of Gastroenterology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Vincent A. Mukkada, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Gary W. Falk, Division of Gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Wenwen Zhang, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA.

Bridgett Goodwin, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA.

Brian Terreri, Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Lexington, MA, USA.

Mena Boules, Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Lexington, MA, USA.

Nirav K. Desai, Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA

Ikuo Hirano, Kenneth C. Griffin Esophageal Center, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The clinical studies included in this analysis were approved by independent institutional review boards or independent ethics committees and were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and relevant regulatory requirements. Patients provided written informed consent, signed by the patient and by the investigator, before study enrollment.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Evan S. Dellon: Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Margaret H. Collins: Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

David A. Katzka: Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Vincent A. Mukkada: Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Gary W. Falk: Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Wenwen Zhang: Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Bridgett Goodwin: Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Brian Terreri: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Mena Boules: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Nirav K. Desai: Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Ikuo Hirano: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Shire ViroPharma, Inc., a member of the Takeda group of companies. Post hoc analyses were supported by Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.

Competing interests: E.S.D. has received research funding from Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Celldex Therapeutics, EuPRAXIA, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GSK, Meritage Pharma, Inc., Miraca Life Sciences, Nutricia, Pfizer/Arena Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Revolo Biotherapeutics, and Shire, a Takeda company; is a consultant for AbbVie, Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Akeso Biopharma, Alfasigma Global, ALK, Allakos, Amgen, Aqilion AB, ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Avir Pharma, Calypso Biotech, Calyx Clinical Trial Solutions/Parexel, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Celldex Therapeutics, Inc., Dr Falk Pharma, EsoCap Biotech, EuPRAXIA, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GSK, GI reviewers, Holoclara, Inc., Invea Therapeutics, Knightpoint, Lucid Diagnostics, Morphic Therapeutic, Nexstone Immunology/Uniquity Bio, Nutricia, Pfizer/Arena Pharmaceuticals, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Robarts Clinical Trials, Inc./Alimentiv, Inc., Sanofi, Shire, a Takeda company, Target RWE, and Upstream Bio; and has received educational grants from Allakos, Aqilion AB, Holoclara, Inc., and Invea Therapeutics. M.H.C. is a consultant for Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Calypso Biotech, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, EsoCap Biotech, GSK, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials, Inc./Alimentiv, Inc., and Shire, a Takeda company. D.A.K. has received research funding from Shire, a Takeda company, and has provided consultancy for Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb. V.A.M. has received research funding from Meritage Pharma, Inc., and Shire, a Takeda company; serves on an adjudication committee for Alladapt Immunotherapeutics; and is a consultant for Allakos, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi/Genzyme, and Shire, a Takeda company. G.W.F. has received research funding from Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Allakos, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Lucid Diagnostics, Nexteos, Pfizer/Arena Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Shire, a Takeda company; and is a consultant for Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Allakos, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Lucid Diagnostics, Nexstone Immunology/Uniquity Bio, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Shire, a Takeda company, and Upstream Bio. B.G., W.Z., and N.K.D. are employees of Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc.; and stockholders of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Limited. B.T. is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; and a stockholder of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Limited. M.B. is an employee of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., but was an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., and a stockholder of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Limited, at the time this study was conducted. I.H. has received research funding from Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Meritage Pharma, Inc., Pfizer/Arena Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Shire, a Takeda company; and is a consultant for Adare Pharmaceuticals/Ellodi Pharmaceuticals, Allakos, ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Calyx/Parexel, Celgene/Receptos/Bristol Myers Squibb, Celldex Therapeutics, Inc., Lilly, EsoCap Biotech, Gossamer Bio, Meritage Pharma, Inc., Nexstone Immunology, Pfizer/Arena Pharmaceuticals, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi/Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Shire, a Takeda company.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participant data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available in the 3 months after the initial request, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after their de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization.

References

- 1. Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, et al. AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters clinical guidelines for the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1776–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias A, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J 2017; 5: 335–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dellon ES, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Long-term treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with budesonide oral suspension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 1488–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta SK, Vitanza JM, Collins MH. Efficacy and safety of oral budesonide suspension in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Budesonide oral suspension improves symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic parameters compared with placebo in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2017; 152: 776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Safety and efficacy of budesonide oral suspension for maintenance therapy in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Budesonide oral suspension improves outcomes in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: results from a phase 3 trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc. EOHILIA (budesonide oral suspension) prescribing information. US Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/213976s000lbl.pdf (2024, accessed 22 February 2024).

- 10. Dellon ES. No maintenance, no gain in long-term treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hudgens S, Evans C, Philips E, et al. Psychometric validation of the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with oral budesonide suspension. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017; 1: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Equator Network. CONSORT 2010. Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials, https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/consort/ (2010, accessed 3 May 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut 2013; 62: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, et al. Newly developed and validated Eosinophilic Esophagitis Histology Scoring System and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis Esophagus 2017; 30: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arnim UV, Biedermann L, Aceves SS, et al. Monitoring patients with eosinophilic esophagitis in routine clinical practice—international expert recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 10: 2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Straumann A, Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, et al. Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintain remission in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1672–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A, et al. Rapid recurrence of eosinophilic esophagitis activity after successful treatment in the observation phase of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1483–1492.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greuter T, Godat A, Ringel A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of high versus low dose swallowed topical steroids for maintenance treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a multi-center observational study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 12: 2514–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ClinicalTrials.gov. Continuation study with budesonide oral suspension (BOS) for adolescent and adult participants with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03245840 (2022, accessed 14 November 2023).

- 22. Lachin JM. Fallacies of last observation carried forward analyses. Clin Trials 2016; 13: 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, et al. Efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets as induction therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019; 157: 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miehlke S, Schlag C, Lucendo AJ, et al. Budesonide orodispersible tablets for induction of remission in patients with active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a 6-week open-label trial of the EOS-2 Programme. United European Gastroenterol J 2022; 10: 330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hirano I, Dellon ES, Hamilton JD, et al. Efficacy of dupilumab in a phase 2 randomized trial of adults with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hatter L, Houghton C, Bruce P, et al. Asthma control with ICS-formoterol reliever versus maintenance ICS and SABA reliever therapy: a post hoc analysis of two randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open Respir Res 2022; 9: e001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sher LD, Wechsler ME, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab reduces oral corticosteroid use in patients with corticosteroid-dependent severe asthma: an analysis of the phase 3, open-label extension TRAVERSE trial. Chest 2022; 162: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. COREOS Collaborators, Ma C, Schoepfer AM, et al. Development of a core outcome set for therapeutic studies in eosinophilic esophagitis (COREOS). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 149: 659–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241307602 for Effect of randomized treatment withdrawal of budesonide oral suspension on clinically relevant efficacy outcomes in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a post hoc analysis by Evan S. Dellon, Margaret H. Collins, David A. Katzka, Vincent A. Mukkada, Gary W. Falk, Wenwen Zhang, Bridgett Goodwin, Brian Terreri, Mena Boules, Nirav K. Desai and Ikuo Hirano in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology