Abstract

Background

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins are a large and complex multigene family of transcription factors with important roles in animal development, including that of fruitflies, nematodes and vertebrates. The identification of orthologous relationships among the bHLH genes from these widely divergent taxa allows reconstruction of the putative complement of bHLH genes present in the genome of their last common ancestor.

Results

We identified 39 different bHLH genes in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, 58 in the fly Drosophila melanogaster and 125 in human (Homo sapiens). We defined 44 orthologous families that include most of these bHLH genes. Of these, 43 include both human and fly and/or worm genes, indicating that genes from these families were already present in the last common ancestor of worm, fly and human. Only two families contain both yeast and animal genes, and no family contains both plant and animal bHLH genes. We suggest that the diversification of bHLH genes is directly linked to the acquisition of multicellularity, and that important diversification of the bHLH repertoire occurred independently in animals and plants.

Conclusions

As the last common ancestor of worm, fly and human is also that of all bilaterian animals, our analysis indicates that this ancient ancestor must have possessed at least 43 different types of bHLH, highlighting its genomic complexity.

Background

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcriptional regulators are key players in a wide array of developmental processes in metazoans, including neurogenesis, myogenesis, hematopoiesis, sex determination and gut development (reviewed in [1,2,3,4,5]). The bHLH domain is approximately 60 amino acids long and comprises a DNA-binding basic region (b) followed by two α helices separated by a variable loop region (HLH) (reviewed in [4]). The HLH domain promotes dimerization, allowing the formation of homodimeric or heterodimeric complexes between different family members. The two basic domains brought together through dimerization bind specific hexanucleotide sequences.

Over 400 bHLH proteins have been identified to date in organisms ranging from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to humans (see, for example [6,7,8]). In previous work, we took advantage of the complete sequencing of the nematode [9] and fly [10] genomes to extract a large, and possibly complete, set of bHLH genes from these two organisms [8]. A phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences of these bHLHs, together with a large number (> 350) of bHLH from other sources, in particular from mouse, led us to define 44 orthologous families (that is, groups of orthologous sequences that derive from the duplication of a common ancestor), among which 36 include bHLH from metazoans only, and 2 have representatives in both yeasts and metazoans [8] (Table 1). We also identified two bHLH motifs present only in yeast, and four that are present only in plants [8].

Table 1.

The 44 families of animal bHLH defined by our phylogenetic analyses

| Family name | Number of worm genes | Number of fly genes | Number of mouse genes | Number of human genes | Number of sea squirt genes | Number of pufferfish genes | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achaete-Scute a | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | A |

| Achaete-Scute b | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | A |

| MyoD | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | A |

| E12/E47 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | A |

| Neurogenin | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | A |

| NeuroD | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5 | A |

| Atonal | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | A |

| Mist | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | A |

| Beta3 | 1 or 2* | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | A |

| Oligo | 0 or 1* | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | A |

| Net | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | A |

| Mesp | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | A |

| Twist | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | A |

| Paraxis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | A |

| MyoR | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | A |

| Hand | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | A |

| PTFa | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | A |

| PTFb | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | A |

| SCL | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | A |

| NSCL | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | A |

| SRC | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | B |

| Figa | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | B |

| Myc | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | B |

| Mad | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 1 or 2† | 0 | B |

| Mnt | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 or 1† | 0 | B |

| Max | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | B |

| USF | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | B |

| MITF‡ | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 2 | B |

| SREBP‡ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | B |

| AP4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | B |

| MLX | 0 or 1§ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | B |

| TF4 | 0 or 1§ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | B |

| Clock | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | C |

| ARNT | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | C |

| Bmal | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | C |

| AHR | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | C |

| Sim | 0 to 1¶ | 1 | 2 or 3¶ | 2 or 3¶ | 1 or 2¶ | 4 or 5¶ | C |

| Trh | 0 to 1¶ | 1 | 1 or 2¶ | 1 or 2¶ | 0 or 1¶ | 0 or 1¶ | C |

| HIF | 1 to 2¶ | 1 | 3 or 4¶ | 3 or 4¶ | 0 or 1¶ | 2 or 3¶ | C |

| Emc | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 4 | D |

| Hey# | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | E |

| Hairy# | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | E |

| E (spl) # | 1 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 8 | E |

| COE | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | F |

| Orphans | 6 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | No |

Families have been named according to the name (or its common abbreviation) of the first discovered or best-known member of the family. The number of members per family in worm, fly and human (complete genomes) as well as in mouse, sea squirt, and pufferfish (uncompleted genomes) is reported. Each family has been tentatively assigned to a high-order group using the classification of Atchley and Fitch [6] and Ledent and Vervoort [8]. Genes that cannot be assigned to any families are categorized as 'orphan' genes. *Beta3 and Oligo are closely related families, one C. elegans gene (F38C2.2) belongs to the Beta3 family while another (DY3.3) is equally related to both Beta3 and Oligo families. †Mad and Mnt are closely related families, one Ciona gene (Not7) belongs to the Mad family while another (LQW20007) is equally related to both Mad and Mnt families. ‡These two families also include yeast genes. §TF4 and Mlx are closely related families, one C. elegans gene (T20B12.6) is equally related to both families. ¶The Hif, Sim, and Trh families form a strongly supported monophyletic group (bootstrap value, 95%). A few genes that are included in this group cannot be clearly related to one of the three families (see Additional data for details). #The Hey, Hairy and Enhancer of split families genes form a well-supported monophyletic group (group E; see Figure 1). Two clear families (Hairy and Hey families) with high bootstrap support emerge from this group. All the remaining sequences have been grouped in a single family (named Enhancer of split), which has no real phylogenetic support. A phylogenetic tree of the group can be found in the Additional data.

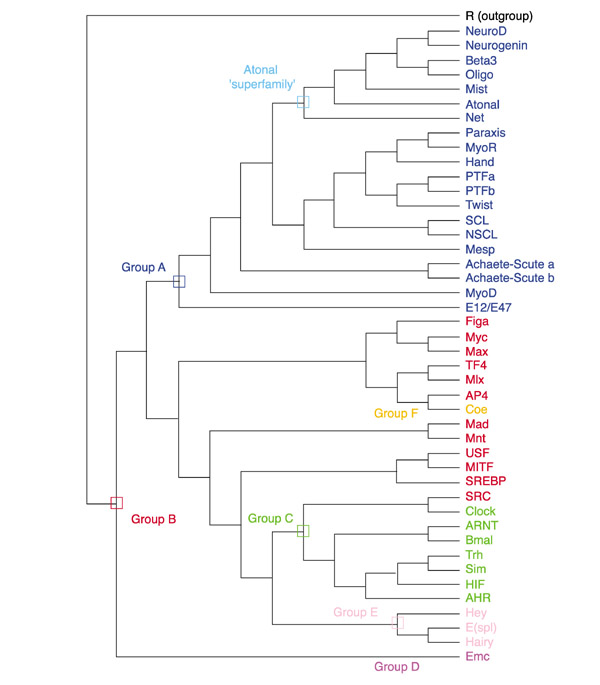

In addition, we defined higher-order groups which include several evolutionarily related families that share structural and biochemical properties [8]. The different groups were named A, B, C, D, E and F, in agreement with the nomenclature of Atchley and Fitch [6]. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic relationships between animal families and their tentative inclusion into the different higher-order groups. The properties of these groups have been described elsewhere [4,6,8].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships and high-order grouping of the bHLH families. A neighbor-joining (NJ) tree showing the evolutionary relationships of the 44 animal bHLH families listed in Table 1 is shown. We used one gene (usually from mouse) per family to construct this tree. Although there are strong theoretical reasons for preferring the unrooted tree, we show a rooted tree because it is easier to display compactly and more clearly represents the relationships at the tip of the branches. This tree is just a representation of an unrooted tree with rooting that should be considered arbitrary. We used the plant bHLH family (R family) as outgroup. For simplicity, we show a tree in which branch lengths are not proportional to distances between sequences. High-order groups [6,8] are shown. Some of these groups (A and E) are monophyletic groups, others (D and F) correspond to only one family, and yet others (B and C) are paraphyletic (the last common ancestor of the different families that constitute the group is also that of bHLHs that do not belong to that group). A subgroup of group A families (the Atonal 'superfamily' [8]) is also highlighted and is displayed in more detail in Figure 2.

In brief, groups A and B include bHLH proteins that bind core DNA sequences referred to as E boxes (CANNTG), respectively CACCTG or CAGCTG (group A) and CACGTG or CATGTTG (group B). Group C corresponds to the family of bHLH proteins known as bHLH-PAS, as they contain a PAS domain in addition to the bHLH. They bind to ACGTG or GCGTG core sequences. Group D corresponds to HLH proteins that lack a basic domain and are hence unable to bind DNA. These proteins act as antagonists of group A bHLH proteins. Group E includes proteins related to the Drosophila Hairy and Enhancer of split bHLH (HER proteins). These proteins bind preferentially to sequences referred to as N boxes (CACGCG or CACGAG). They also contain two characteristic domains in addition to the bHLH, the 'Orange' domain and a WRPW peptide in their carboxy-terminal part. Group F corresponds to the COE family, which is characterized by the presence of an additional domain involved both in dimerization and in DNA binding, the COE domain. Yeast and plant bHLHs are all included in group B [6,8].

The completion of the human genome sequencing project [11,12] now allows us to derive the complete set of bHLH present in a vertebrate genome. TBLASTN searches [13] on the human genome draft sequence enabled us to identify 125 different human bHLHs. After exhaustive searches with BLASTP in protein databases and the use of the SMART database (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool [14,15]) we also identified additional fly, worm and mouse bHLH sequences (total number: 58 in fly, 39 in worm, and 102 in mouse). In addition, we made TBLASTX searches on the incompletely sequenced genomes of the pufferfish Takifugu rubripes and the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis and retrieved 84 and 18 different bHLHs, respectively. We also retrieved, through BLASTP searches, eight different bHLH genes from the completely sequenced yeast genome.

Phylogenetic analysis of all these sequences allowed us to define 44 orthologous families of bHLH proteins in metazoans (the 38 families defined in our previous report plus 6 additional ones, arising out of the additional sequences used in this analysis). Our work now enables comparison of the putative complete repertoires of bHLHs in metazoans belonging to the two main subdivisions of bilaterian animals (the Bilateria; see [16] for a recent overview of the classification of metazoans) - the deuterostomes (human) and the protostomes (fly and worm). This comparison gives us the opportunity to analyze evolution of the diversity of the bHLHs on a metazoan-wide scale, thus giving useful insights into the evolution of multigenic families. In addition, our results allow us to reconstruct the minimum complement of bHLH genes that were present in the bilaterian common ancestor. We also discuss the evolution of the bHLH gene family.

Results and discussion

Isolation of bHLH sequences from protein and genome databases

To isolate human bHLH genes, we made TBLASTN searches [13] on the human genome draft sequence [11], as described in Materials and methods. We completed the list of the retrieved bHLH using the SMART database [14,15]. We eventually got 125 different human bHLH sequences, which are listed in Table 2. All retrieved sequences were used to make BLASTP searches against protein databases in order to detect those sequences that were already identified. We found that 80 sequences were already present in protein databases; 45 of the retrieved sequences from the human genome correspond to previously uncharacterized genes. We similarly retrieved, by TBLASTN, 84 and 18 different bHLH sequences from the incompletely sequenced genomes of the pufferfish T. rubripes and the sea squirt C. intestinalis, respectively (see Additional data files). In addition, we retrieved the complete set of bHLH genes present in the fly (total 58), worm (39), and yeast (8) genomes, as well as all the cloned mouse bHLH genes to date (102), as described in Materials and methods. These sequences with their accession numbers and some information (genomic localization and orthology relationships) are listed in Tables 3,4,5,6.

Table 2.

The complete list of bHLH genes from Homo sapiens

| Sequence identification | Gene name | Family | Mouse ortholog(s) | Contigs | Chromosome localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P50553 | Hash1 | Achaete-Scute a | Mash1 | NT_009439.3 | 12q22-q23 |

| Q99929 | Hash2 | Achaete-Scute a | Mash2 | NT_009368.3 | 11p15.5 |

| N024228 | Hash3a* | Achaete-Scute b | Mash3 | NT_024228.3 | 11p15.3 |

| N004680 | Hash3b* | Achaete-Scute b | ? | NT_004680.3 | 1q31-q32 |

| N009720 | Hash3c* | Achaete-Scute b | ? | NT_009720.3 | 12q23-q24 |

| P15173 | Myf4 | MyoD | Myogenin | NT_004662.3 | 1q31-41 |

| P23409 | Myf6 | MyoD | Myf6 | NT_024473.2 | 12q21 |

| P15172 | Myf3 | MyoD | MyoD | NT_009307.3 | 11p15.4 |

| P13349 | Myf5 | MyoD | Myf5 | NT_024473.2 | 12q21 |

| N011269 | E2A* | E12/E47 | E2A | NT_011269.3 | 19p13.3 |

| Q99081 | TF12 | E12/E47 | TF12 | NT_010289.3 | 15q21 |

| P15884 | TCF4 | E12/E47 | TCF4 | NT_011059.5 | 18q21.1 |

| P15884 D | TCF4b* | E12/E47 | TCF4 | NT_029427.1 | 12 |

| P15923 | TCF3 | E12/E47 | ? | NT_011269.3 | 19p13.3 |

| N008413 | E12/E47 | ? | NT_008413.3 | 9p22-q22 | |

| Q92858 | Hath1 | Atonal | Math1 | ? | 4q22 |

| N029388 | Hath5* | Atonal | Math5 | NT_029388.3 | 10q21-q26 |

| N007816 | Mist1* | Mist | Mist1 | NT_007816.3 | 7q21-q31 |

| N011512 | Oligo1* | Oligo | Oligo 1 | NT_011512.3 | 21q21-q22 |

| Q9NZ14 | Oligo2* | Oligo | Oligo 2 | ? | ? |

| N025741 | Oligo3* | Oligo | Oligo 3 | NT_025741.3 | 6q22-q24 |

| N030199 | Beta3a* | Beta3 | Beta3 | NT_030199.1 | 8q21 |

| N011333 | Beta3b* | Beta3 | Q9H494 | NT_011333.4 | 20p11-q13 |

| Q9H2A3 | Neurogenin2 | Neurogenin | Math4a | NT_022859.3 | 4 |

| N024089 | Hath4b | Neurogenin | Math4b | NT_024089.3 | 10q21.3 |

| Q92886 | NDF3 | Neurogenin | NDF3 | NT_007091.3 | 5q23-Q31 |

| N009563 | Hath3* | NeuroD | Math3 | NT_009563.3 | 12q13-q14 |

| N007819 | Hath2* | NeuroD | Math2 | NT_007819.6 | 7p14-p15 |

| Q15784 | NDF2 | NeuroD | NDF2 | NT_010685.3 | 17q12 |

| Q13562 | NDF1 | NeuroD | NDF1 | NT_005272.3 | 2q32 |

| N010356a | Mesp1* | Mesp | ? | NT_010356.6 | 15q25-q26 |

| N010356b | Mesp2* | Mesp | ? | NT_010356.6 | 15q25-q26 |

| N010356c | Mesp3* | Mesp | ? | NT_010356.6 | 15q25-q26 |

| N015926 | Mesp4* | Mesp | pMeso1 | NT_015926.3 | 2p24 |

| N015805 | Hath6* | Net | Math6 | NT_015805.6 | 2p11-q24 |

| N005204a | MyoR1* | MyoR | Pod1 | NT_005204.6 | 2p21-p25 |

| N008253 | MyoR2* | MyoR | MyoR | NT_008253.3 | 8q13 |

| N005204b | MyoR3* | MyoR | ? | NT_005204.6 | 2p21-p25 |

| N008166 | MyoR4* | MyoR | ? | NT_008166.3 | 8q13-q22 |

| Q9HC25 | P48 | PTFa | PTF1 | NT_008895.6 | 10p12-q22 |

| N007918 | PTFb* | PTFb | ? | NT_007918.6 | 7p15-p21 |

| O96004 | ehand | Hand | eHand | NT_026280.4 | 5q33 |

| O95300 | dHand | Hand | dHand | NT_006257.3 | 4q31-q33 |

| Q15672 | twist | Twist | Twist | NT_007918.3 | 7p21 |

| N011493 | paraxis* | Paraxis | paraxis | NT_011493.3 | 20 |

| Q02577 | NSCL-2 | NSCL | Hen2 | NT_021883.3 | 1p11-p12 |

| Q02575 | NSCL-1 | NSCL | Hen1 | NT_004406.3 | 1q22 |

| Q16559 | Tal2 | SCL | Tal2 | NT_008470.3 | 9q31 |

| P17542 | Tal1 | SCL | Tal1 | NT_004701.3 | 1p32 |

| P12980 | Lyl | SCL | Lyl1+Lyl2 | NT_011247.3 | 19p13.2 |

| Q01664 | AP4 | AP4 | AP4 | NT_015360.3 | 19p13 |

| Q99583 | Mnt | Mnt | Mnt | NT_010692.3 | 17p13.3 |

| Q14582 | Mad4 | Mad | Mad4 | NT_022865.3 | 4p16.3 |

| Q9H7H9 | Mad4b* | Mad | ? | NT_022865.3 | 4p16.3 |

| P50539 | Mxi1 | Mad | Mxi1 | NT_024048.3 | 10q25 |

| Q05195 | Mad1 | Mad | Mad1 | NT_005420.3 | 2p12-p13 |

| AAH00745 | Mad3 | Mad | Mad3 | ? | ? |

| P25912 | Max | Max | Max | NT_025892.3 | 14q23 |

| P04198 | N-Myc | Myc | N-Myc | NT_026240.1 | 2p24.1 |

| P01106 | C-Myc | Myc | C-Myc | NT_008012.3 | 8q24 |

| P12524 | L-Myc1 | Myc | L-Myc | NT_004893.3 | 1p34 |

| P12525 | L-Myc2 | Myc | ? | NT_011762.3 | Xq22-q23 |

| N011572 | L-Myc3* | Myc | ? | NT_011572.3 | Xq27 |

| O43792 | SRC1 | SRC | SRC1 | NT_005204.3 | 2p22-p25 |

| Q15596 | SRC2 | SRC | SRC2 | NT_023676.3 | 8p22-q21 |

| Q9Y6Q9 | SRC3 | SRC | SRC3 | NT_011371.3 | 20q12 |

| O75030 | MITF | MITF | MITF | NT_005510.3 | 3p12-p14 |

| P19532 | TFE3 | MITF | TFE3 | NT_011611.3 | Xp11 |

| P19484 | TFEB | MITF | TFEB | NT_023409.3 | 6p21 |

| O14948 | TFEC1 | MITF | TFEC | NT_026338.1 | 7 |

| N009714 | TFEC2* | MITF | TFEC | NT_009714.3 | 12p11-q14 |

| P36956 | SREBP1 | SREBP | SREBP1 | NT_010657.3 | 17p11.2 |

| Q12772 | SREBP2 | SREBP | SREBP2 | NT_011520.3 | 22q13 |

| P22415 | USF1 | USF | USF1 | NT_026219.3 | 1q22-q23 |

| Q15853 | USF2 | USF | USF2 | NT_011294.3 | 19q13 |

| N009711 | USF2b* | USF | USF2 | NT_009711.6 | 12 |

| Q9NP71 | MLXa | MLX | MLX | NT_023557.3 | 7q11 |

| Q9HAP2 | Mondoa | MLX | ? | ? | 12q21 |

| Q9UH92 | TF4a* | TF4 | TF4 | NT_010771.3 | 17q21.1 |

| N005106 | TF4b* | TF4 | ? | NT_005106.6 | 2p24-q36 |

| N005420 | Figa | Figa | Figa | NT_005420.3 | 2p13-p24 |

| O00327 | Bmal1 | Bmal | Bmal1 | NT_017854.3 | 11p15 |

| Q9NYQ5 | Bmal2 | Bmal | ? | NT_009622.3 | 12p11-p12 |

| P27540 | ARNT1 | ARNT | ARNT1 | NT_004811.3 | 1q21 |

| Q9HBZ2 | ARNT2 | ARNT | ARNT2 | NT_004811.6 | 1q21 |

| O15516 | clock1 | Clock | clock | NT_029271.2 | 4q12 |

| Q99743 | NPAS2 | Clock | NPAS2 | NT_022171.6 | 2q13 |

| Q16665 | Hif1a | HIF | Hif1a | ? | 14q21-q24 |

| Q99814 | EPAS1 | HIF | EPAS1 | NT_029237.2 | 2p21-p16 |

| O95262 | Hif3a | HIF | Hif3a | NT_011166.6 | 19q13 |

| Q99742 | NPAS1 | HIF/Sim/Trh | NPAS1 | NT_011166.3 | 19q13 |

| P81133 | Sim1 | Sim | Sim1 | NT_019424.3 | 6q16-q21 |

| Q14190 | Sim2 | Sim | Sim2 | NT_011512.3 | 21q22.13 |

| Q9H323 | NPAS3 | Trh | NPAS3 | NT_010164.3 | 14q12-13 |

| Q13804 | AHR1 | AHR | AHR | NT_007755.4 | 7p15 |

| N016866 | AHR2* | AHR | ? | NT_016866.3 | 5p15 |

| Q9HAZ3 | AHR3* | AHR | ? | NT_016866.3 | 5p15 |

| N030106 | AHR4* | AHR | ? | NT_030106.1 | 11q12-q13 |

| Q9Y5J3 | Herp2 | Hey | Hey1 | NT_023700.5 | 8q21 |

| Q9UBP5 | Herp1 | Hey | Herp1 | ? | ? |

| Q9NQ87 | HEYL | Hey | ? | NT_004893.5 | 1p34.3 |

| Q9NQ87D | HEYLb* | Hey | ? | NT_004893.5 | 1p34.3 |

| N029966 | Hey4* | Hey | ? | NT_029966.1 | 4 |

| O14503 | Dec1 | E(spl) | Dec1 | NT_005927.3 | 3p24-p26 |

| BAB21502 | Dec2 | E(spl) | Dec2 | NT_009471.3 | 12p11-p12 |

| N029854 | Hes5* | E(spl) | Hes5 | NT_029854.1 | 1p36 |

| Q9BYEO | Hes7 | E(spl) | Hes7 | NT_010841.2 | 17p12-p13 |

| N019265 | Hes3* | E(spl) | Hes3+BAA9469 | NT_019265.6 | 1p36 |

| Q9P2S3 | Hes6* | E(spl) | Hes6 | NT_005139.6 | 2q36-q37 |

| Q9Y543 | Hes2 | E(spl) | Hes2 | NT_019265.6 | 1p36 |

| Q9BYW0 | Cha | E(spl) | ? | NT_011333.4 | 20q11-q13 |

| Q14469 | Hes1 | Hairy | Hes1 | NT_005571.3 | 3q28-q29 |

| Q9HCC6 | Hes4 | Hairy | ? | NT_025635.5 | 1p36 |

| P41134 | Id1 | Emc | Id1 | NT_028392.4 | 20q11 |

| N00599 | Id2 | Emc | ? | NT_005999.3 | 3p21-q13 |

| Q02363 | Id2 | Emc | Id2 | NT_022194.3 | 2p25 |

| Q02535 | Id3 | Emc | Id3 | NT_004359.6 | 1p36 |

| P47928 | Id4 | Emc | Id4 | NT_027049.3 | 6p21-p22 |

| Q9UH73 | EBF1 | Coe | Coe1 | NT_007006.4 | 5q34 |

| Q9BQW3 | Coe2* | Coe | ? | NT_023666.3 | 8p21-p22 |

| Q9H4W6 | EBF3 | Coe | ? | NT_008818.6 | 10q25-q26 |

| Q9NUB6 | Coe4* | Coe | ? | ? | 20p11-p13 |

| N010809 | ? | Orphan | ? | NT_010809.6 | 17p13.3 |

| Q9NX45 | ? | Orphan | ? | NT_030131.1 | 13q12-q14 |

| Q9H8R3 | ? | Orphan | ? | NT_010194.6 | 15q14-q22 |

Human sequences are identified using their accession number from Swissprot, Trembl, Smart or NCBI genome project sequences. In the latest case, the accession number is that of the contig which includes the bHLH gene. This accession number NT_XXXXXX.Y (XXXXXX identifies the contig and Y the version of the draft) has been abbreviated as NXXXXXXX. Gene names are those reported in protein databases or have been assigned by us on the basis of the orthology relationships with mouse genes (these names are marked by an asterisk). The identification of the contig in which each of the bHLH gene is included is also given. In a few cases (marked with a question mark), we were unable to retrieve, in the genome sequence, previously cloned genes. This may be due to the fact that these genes lie in still unsequenced regions of the genome, or to some limitations of the current version of BLAST (see text for details). Chromosomal localizations are given as reported in the NCBI human genome sequence database (LocusLink and/or OMIM [77,78]).

Table 3.

The complete list of bHLH genes from Drosophila melanogaster

| Full gene name | Symbol | ID | Family | Localization | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| daughterless | da | CG5102 | E12/E47 | 31D11-E1 | pir||A31641 |

| nautilus | nau | CG10250 | MyoD | 95B3-5 | SW:P22816 |

| achaete | ac | CG3796 | Achaete-Scute a | 1B1 | gb|AAF45498.1 |

| scute | sc | CG3827 | Achaete-Scute a | 1B1 | gb|AAA28313.1 |

| lethal of scute | l'sc | CG3839 | Achaete-Scute a | 1B1 | gb|AAF45500.1 |

| asense | ase | CG3258 | Achaete-Scute a | 1B1 | gb|AAF45502.1 |

| target of poxn (biparous) | tap (bp) | CG7659 | Neurogenin | 74B1-2 | emb|CAA65103.1 |

| Mist1-related | Mistr | CG8667 | Mist | 39D3 | gb|AAF53991.1 |

| Olig family | Oli | CG5545 | Beta3 | 36C6-7 | gb|AAF53631.1 |

| cousin of atonal | cato | CG7760 | Atonal | 53A1-2 | gb|AAF58026.1 |

| atonal | ato | CG7508 | Atonal | 84F6 | gb|AAF54209.1 |

| absent MD and olfactory sensilla | amos | CG10393 | Atonal | 37A1-2 | gb|AAF53678.1 |

| net | net | CG11450 | Net | 21A5-B1 | gb|AAF51562.1 |

| HLH54F (MyoR*) | MyoR* | CG5005 | MyoR | 54E7-9 | gb|AAF57795.1 |

| salivary gland-expressed bHLH | sage | CG12952 | Mesp | 85D7-10 | gb|AAF54351.1 |

| paraxis* | Pxs* | CG12648 | Paraxis | 9A4 | sp|Q9W2Z5 |

| twist | twi | CG2956 | Twist | 59C2-3 | emb|CAA32707.1 |

| 48 related 1 | Fer1 | CG10066 | PTFa | 84C3-4 | gb|AAF54058.1 |

| 48 related 2 | Fer2 | CG5952 | PTFb | 89B9-12 | gb|AAF55280.1 |

| 48 related 3 | Fer3 | CG6913 | PTFb | 86F1-2 | gb|AAF54684.1 |

| hand | Hand | CG18144 | Hand | 31D1-6 | gb| AAF52900.1 |

| HLH3b (SCL*) | SCL* | CG2655 | SCL | 3B3-4 | gb|AAF45802.1 |

| HLH4C (NSCL*) | NSCL* | CG3052 | NSCL | 4C6-7 | gb|AAF45967.1 |

| EG:114E2.2 (Mnt*) | Mnt* | CG2856 | Mnt | 3F2-3 | sp|O46042 |

| max | max | CG9648 | Max | 76A3 | gb|AAF49179.1 |

| diminutive | dm | CG10798 | Myc | 3D3-4 | gb|AAB39842.1 |

| USF | USF | CG17592 | USF | 4C4 | gb|AAF45953.1 |

| cropped | crp | CG7664 | AP4 | 35F6-7 | gb|AAF53510.1 |

| bigmax | bmx | CG3350 | TF4 | 97F5-6 | gb|AAF56696.1 |

| MLX* | MLX* | CG18362 | MLX | 39D1-2 | gb|AAF53989.1 |

| HLH106 (SREBP*) | SREBP* | CG8522 | SREBP | 76D1-3 | gb|AAF49115.1 |

| taiman | tai | CG13109 | SRC | 30A7-8 | sp|Q9VLD9 |

| clock | clk | CG7391 | Clock | 66A11-B1 | gb|AAD10630.1 |

| Resistance to Juvenile Hormone | Rst(1)JH | CG1705 | Clock | 10C6-8 | gb|AAC14350.1 |

| germ cell-expressed bHLH-PAS | gce | CG6211 | Clock | 13C1 | gb|AAF48439.1 |

| AHR2* | AHR2* | CG12561 | AHR | 96F14-97A1 | gb|AAF56569.1 |

| spineless | ss | CG6993 | AHR | 89C1-2 | gb|AAD09205.1 |

| single-minded | sim | CG7771 | Sim | 87D12-13 | gb|AAF54902.1 |

| trachealess | trh | CG6883 | Trh | 61C1 | gb|AAA96754.1 |

| similar (Hif-1) | sima | CG7951 | HIF | 99D5-F1 | gb|AAC47303.1 |

| tango | tgo | CG11987 | ARNT | 85C5-7 | gb|AAF54329.1 |

| cycle | cyc | CG8727 | BMAL | 76D2-3 | gb|AAF49107.1 |

| extramacrochaete | emc | CG1007 | Emc | 61D1-2 | gb|AAF47413.1 |

| Hey | Hey | CG11194 | Hey | 43F9-44A1 | gb|AAF59152.1 |

| Sticky ch1 | Stich1 | CG17100 | Hey | 86A5-6 | gb|AAF24476.1 |

| hairy | h | CG6494 | Hairy | 66D11-12 | emb|CAA34018.1 |

| deadpan | dpn | CG8704 | Hairy | 44B3-4 | gb|AAB24149.1 |

| similar to deadpan | side | CG10446 | Hairy | 37B9-11 | gb|AAF53741.1 |

| Enhancer of split m3 | E(spl) m3 | CG8346 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | gb|AAF56550.1 |

| Enhancer of split m5 | E(spl) m5 | CG6096 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | emb|CAA34552.1 |

| Enhancer of split m8 | E(spl) m8 | CG8365 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | sp|P13098 |

| Enhancer of split m7 | E(spl) m7 | CG8361 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | emb|CAA34553.1 |

| Enhancer of split mB (g) | E(spl) mB (g) | CG8333 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | gb|AAA28910.1 |

| Enhancer of split mC (d) | E(spl) mC (d) | CG8328 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | gb|AAA28911.1 |

| Enhancer of split mA (b) | E(spl) mA (b) | CG14548 | E (spl) | 96F10-12 | gb|AAA28909.1 |

| HES-related | Her | CG5927 | E (spl) | 17A3 | gb|AAF48810.1 |

| knot (collier) | kn (col) | CG10197 | COE | 51C2-5 | gb|AAF58204.1 |

| Delilah | del | CG5441 | Orphan | 97B1-2 | gb|AAF56590.1 |

Gene names (with commonly used synonyms in some cases) and their usual abbreviation are as reported in FlyBase [79,80], except those marked by an asterisk. In these cases, we propose names based on the orthology relationships with well-characterized vertebrate genes. Identification numbers are those from the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project [81]. Sequences are listed with the family in which there are included (or stated as orphan genes), their chromosomal localization (position on the polytene chromosomes map as found in FlyBase), and their accession number. The 'orphan' gene Delilah clearly belongs to the high-order group A and is most probably a highly divergent NeuroD family gene (see [8] for discussion).

Table 4.

The complete list of bHLH genes from Caenorhabditis elegans

| Sequence name | Family | Localization | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLH-2 (MO5B5.5) | E12/E47 | I: 1,82 | TR:Q17588 |

| HLH-1 (BO3O4.1) | MyoD | II: -4,51 | SW:P22980 |

| HLH-3 (T29B8.6) | Achaete-Scute a | II: 1 | gb|AAB38323.1 |

| C18A3.8 | Achaete-Scute a | II:1,11 | TR:Q09961 |

| F57C12.3 | Achaete-Scute a | X: -19,47 | TR:Q20941 |

| C28C12.8 | Achaete-Scute a | IV: 3,86 | TR:Q18277 |

| T15H9.3 | Achaete-Scute b | II: 1,51 | emb|CAA87416.1 |

| C34E10.7 (cnd-1) | NeuroD | III: -2,01 | sp|P46581 |

| Y69A2AR | Neurogenin | **** | **** |

| F38C2.2 | Beta3 | IV: 24,06 | TR:O45489 |

| DY3.3 | Beta3/Oligo | I: 3,04 | TR:O45320 |

| T14F9.5 (lin-32) | Atonal | X: -15,13 | TR:10574 |

| T05G5.2 | Net | III:0,92 | sp|P34555|YNP2 |

| ZK682.4 | MyoR | V: 1,87 | TR:Q23579 |

| HLH-8 (CO2B8.4) | Twist | X: -0,63 | gb|AAC26105.1 |

| C44C10.8 | Hand | X: 5,8 | TR:Q18612 |

| F48D6.3 | PTFb | X: -8,42 | TR:Q20561 |

| C43H6.8 | NSCL | X: -14 | TR:Q18590 |

| F46G10.6 | Max | X: 12,32 | TR/Q18711 |

| T19B10.11 | Max | V: 3,05 | TR:P90982 |

| RO3E9.1 (MDL-1) | Mad | X:-2,63 | sp|Q21663 |

| F40G9.11 | USF | III: -28,29 | gb|AAC68792 |

| W02C12.3 | MITF | IV: -1, 14 | TR:P91527 |

| F58A4.7 | AP4 | III: 0,63 | SW:P34474 |

| Y47D3B.7 | SREBP | III: 8,9 | TR:Q9XX00 |

| T20B12.6 | TF4/Mlx | III:-0,71 | gb|AAA19059.1 |

| C15C8.2 | Clock | V: 4,63 | emb|CAA99775.1 |

| C41G7.5 | AHR | I: 3,75 | emb|CAB51463.1 |

| F38A6.3 | HIF | V: 27,08 | pir||T21944 |

| T01D3.2 | HIF/Sim/Trh | V: 5,39 | TR:P90953 |

| C25A11.1 (AHA-1) | ARNT | X: 0,43 | TR:O02219 |

| lin-22 | E (spl) | IV: 6,9 | gb|AAB68848.1 |

| Y16B4A.1 (Unc-3) | COE | X: 19,39 | gb|AAC06226.1 |

| Y39A3CR.6 | Orphan | III: -19,16 | gb|AAF605231 |

| T01E8.2 (REF-1) * | Orphan | II: 2,22 | emb|CAA88744.1 |

| C17C3.10* | Orphan | II: -1,28 | gb|AAB52693.1 |

| F31A3.4 (F31A3.2)* | Orphan | X: 24,06 | TR:Q19917 |

| C17C3.7* | Orphan | II: -1,28 | gb|AAK31421 |

| C17C3.8* | Orphan | II:1,28 | TR:Q18053 |

Gene identifications are those of the C. elegans genome project. The localization of the genes referred to the worm recombination genetic map as found in Wormbase [82]. Sequences marked with an asterisk form a well supported monophyletic group and encode proteins with two bHLH (see text for details). The Y69A2AR gene was not found in the databases. Its sequence comes from [45].

Table 5.

The complete list of bHLH genes from Mus musculus

| Gene name | Family | Human ortholog(s) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mash1 | Achaete-Scute a | P50553 | gb|AAB28830.1 |

| Mash2 | Achaete-Scute a | Q99929 | gb|AAD33794.1 |

| Mash3 | Achaete-Scute b | N024228 | sp|CAC37689 |

| Myogenin | MyoD | P15173 | sp|P12979 |

| Myf6 | MyoD | P23409 | ref|NP_032683.1 |

| MyoD | MyoD | P15172 | sp|P10085 |

| Myf5 | MyoD | P13349 | ref|NP_032682.1 |

| E2A | E12/E47 | N011269 | sp|15806 |

| TF12 | E12/E47 | Q99081 | ref|NP_035674.1 |

| TCF4 | E12/E47 | P15884/P15884 D | ref|NP_038713.1 |

| KA1 | E12/E47 | ? | dbj|BAA06218.1 |

| Math1 | Atonal | Q92858 | dbj|BAA07791.1 |

| Math5 | Atonal | N024033 | gb|AAC68868.1 |

| Mist1 | Mist | N007757 | gb|AAF17706.1 |

| Oligo1 | Oligo | N011512 | ref|NP_058664.1 |

| Oligo2 | Oligo | Q9NZ14 | sptrembl|Q9EQW6 |

| Oligo3 | Oligo | N025741 | sptrembl|Q9EQW5 |

| Beta3 | Beta3 | N023718 | gb|AAF32324.1 |

| Q9H494 | Beta3 | N011476 | sptrembl|Q9H494 |

| Math4a | Neurogenin | Q9H2A3 | gb|AAC53028.1 |

| Math4b | Neurogenin | N024089 | emb|CAA70366.1 |

| Math4C | Neurogenin | Q92886 | sp|P70660 |

| Math2 | NeuroD | N007825 | dbj|BAA07923.1 |

| Math3 | NeuroD | N009563 | gb|AAC15969.1 |

| NDF1 | NeuroD | Q13562 | sp|Q62414 |

| NDF2 | NeuroD | Q15784 | gb|AAC52203.1 |

| Math6 | Net | N005263 | spnew|BAB39468 |

| Mesp1 | Mesp | ? | gb|AAF70375.1 |

| Mesp2 | Mesp | ? | gb|AAB51199.1 |

| pMeso1 | Mesp | N015926 | ref|NP_062417.1 |

| Pod1 | MyoR | N007203 | gb|AAC62513.1 |

| MyoR | MyoR | N008253 | gb|AAD10053.1 |

| PTF1 | PTFa | Q9HC25 | emb|CAB65273.1 |

| eHand | Hand | O96004 | gb|AAB35104.1 |

| dHand | Hand | O95300 | gb|AAC52338.1 |

| Twist | Twist | Q15672 | gb|AAA40514.1 |

| Dermo1 | Twist | ? | emb|CAA69333.1 |

| Paraxis | Paraxis | N011493 | gb|AAA86825.1 |

| Scleraxis | Paraxis | ? | gb|AAB34266.1 |

| Hen1 | NSCL | Q02575 | gb|AAA39840.1 |

| Hen2 | NSCL | Q02577 | gb|AAB22580.1 |

| Tal1 | SCL | P17542 | emb|CAB72256.1 |

| Tal2 | SCL | Q16559/N024631 | gb|AAA40162.1 |

| Lyl1 | SCL | P12980 | emb|CAA40870.1 |

| Lyl2 | SCL | P12980 | pir||B43814 |

| Figa | Figa | N005420 | sptrembl|O55208 |

| AP4 | AP4 | Q01664 | gb|AAF80448.1 |

| Mnt | Mnt | Q99583 | swissprot|O08789 |

| Mxi1 | Mad | P50539 | swissprot|P50540 |

| Mad1 | Mad | Q05195 | swissprot|P50538 |

| Mad3 | Mad | AAH00745 | sptrembl|Q60947 |

| Mad4 | Mad | Q14582 | pir||S60006 |

| Max | Max | P25912 | sp|P28574 |

| N-Myc | Myc | P04198 | gb|AAA39833.1 |

| C-Myc | Myc | P01106 | emb|CAA25508.1 |

| L-Myc | Myc | P12524 | emb|CAA32128.1 |

| S-Myc | Myc | ? | ref|NP_034980.1 |

| SRC1 | SRC | O43792 | gb|AAB01228.1 |

| SRC2 | SRC | Q15596 | gb|AAB06177.1 |

| SRC3 | SRC | Q9Y6Q9 | sp|O09000 |

| MITF | MITF | O75030 | gb|AAF81266.1 |

| TFE3 | MITF | P19532 | gb|AAB21130.1 |

| TFEB | MITF | P19484 | gb|AAD20979.1 |

| TFEC | MITF | N009714/O14948 | gb|AAD24426.1 |

| SREBP1 | SREBP | P36956 | dbj|BAA74795.1 |

| SREBP2 | SREBP | Q12772 | gb|AAG01859.1 |

| USF1 | USF | P22415 | emb|CAA64627.1 |

| USF2 | USF | Q15853/N026304 | pir||A56522 |

| Mlx | MLX | Q9NP71 | gb|AAK20940.1 |

| TF4 | TF4 | Q9UH92 | gb|AAB51368.1 |

| Bmal1 | BMAL | O00327 | dbj|BAA76414.1 |

| ARNT1 | ARNT | P27540 | gb|AAA56717.1 |

| ARNT2 | ARNT | Q9HBZ2 | dbj|BAA09799.1 |

| Clock | Clock | O15516 | swissnew|O08785 |

| NPAS2 | Clock | Q99743/N023384 | gb|AAB47249.1 |

| Hif1a | HIF | Q16665 | emb|CAA70306.1 |

| EPAS1 | HIF | Q99814 | gb|AAC12871.1 |

| Hif3a | HIF | O95262 | gb|AAC72734.1 |

| NPAS1 | HIF/Sim/Trh | Q99742 | gb|AAB47247.1 |

| Sim1 | Sim | P81133 | gb|AAC05481.1 |

| Sim2 | Sim | Q14190 | gb|AAB84099.1 |

| NPAS3 | Trh | Q9H323 | gb|AAF14283.1 |

| AHR | AHR | Q13804 | dbj|BAA07469.1 |

| Id1 | Emc | P41134 | sp|P20067 |

| Id2 | Emc | Q02363 | gb|AAA79771.1 |

| Id3 | Emc | Q02535 | sp|P41133 |

| Id4 | Emc | P47928 | emb|CAA05120.1 |

| Hey1 | Hey | Q9Y5J3 | emb|CAB51321.1 |

| Herp1 | Hey | Q9UBP5 | gb|AAF37298.1 |

| Hes1 | Hairy | Q14469 | dbj|BAA03931.1 |

| Dec1 | E(spl) | O14503 | sptrembl|O14503 |

| Dec2 | E(spl) | BAB21502 | spnew|BAB21503 |

| Hes2 | E(spl) | Q9Y543 | dbj|BAA24091.1 |

| Hes3 | E(spl) | N019265 | dbj|BAA19799.1 |

| Hes5 | E(spl) | N004350 | dbj|BAA06858.1 |

| Hes6 | E(spl) | Q9P2S3 | gb|AAF63757.1 |

| Hes7 | E(spl) | Q9BYEQ | spnew|BAB39526 |

| BAA9469 | E(spl) | N019265 | spnew|BAA9469 |

| Coe1 | Coe | Q9UH73 | swissprot|Q07802 |

| MOTF1 | Coe | ? | gb|AAB58423.1 |

| Coe2 | Coe | ? | swissprot|O08792 |

| Coe3 | Coe | ? | swissprot|O08791 |

Mouse genes are listed with the family in which they are included, the identification of their human ortholog(s) (? indicates that no clear ortholog was found, see text for details), and their accession number. In most cases, several names exist for each gene. We report here only one name; synonyms can be found in the protein databases using the reported accession numbers.

Table 6.

The complete list of bHLH genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae

| Gene name | Accession number | Family |

|---|---|---|

| RTG3P | gb|AAA86842.1 | RTG3P |

| RTG1 | sp| P32607 | MITF |

| TYE7 | sp|P33122 | SREBP |

| HMS1 | sp|Q12398 | SREBP |

| Pho4 | ref|NP_011227.1 | Pho4 |

| CBP | gb|AAA34490.1 | CBP |

| Ino2 | sp| P26798 | Orphan |

| Ino4 | sp|P13902 | Orphan |

Yeast genes are listed with the family in which they are included and their accession number.

Determination of orthology relationships

To carry out evolutionary analyses of multigene families requires one to distinguish orthologs, which have evolved by vertical descent from a common ancestor, from paralogs, which arise by duplication and domain shuffling within a genome [17]. Failure to do so can result in functional misclassification and inaccurate molecular evolutionary reconstructions [18,19]. The overall similarity (as determined by the BLAST E-value) is often used as a criterion to determine orthology relationships within large data sets such as complete genomes [20,21,22,23], but there is evidence that more rigorous phylogenetic reconstructions are required to confidently determine orthologies [22,24]. We therefore constructed phylogenetic trees to define groups of orthologous sequences, as we did previously [8] (see Materials and methods).

We determined 44 orthologous families that contain most of the metazoan bHLH families (Table 1 and Additional data). Two of these families also contain yeast genes. The criterion we used to define orthologous families was as in [8,25]; that is, orthologous families are monophyletic groups found in the gene trees constructed by different phylogenetic methods and whose monophyly is supported by bootstrap values larger than 50%. We named each family according to its first discovered member or, in a few cases, its best-characterized member. This analysis gave similar results to that described in [8], except that the additional sequences included in the present phylogenetic analyses led us to define six additional families of bHLHs from metazoans, compared with our previous report. We have also to mention the existence of three yeast-specific families.

Comparison of the human and mouse bHLH repertoires

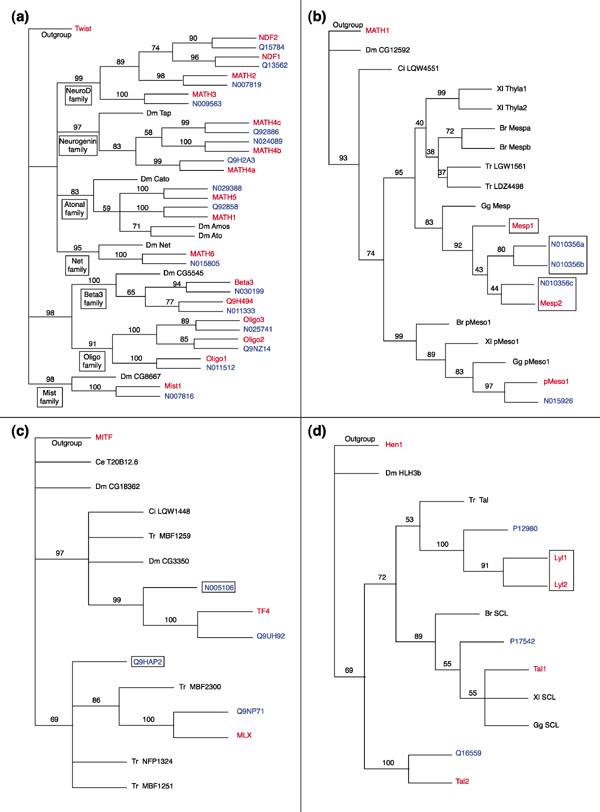

We found a total of 125 and 102 different bHLH sequences in human and mouse, respectively (Tables 2 and 5). These sequences were used to make phylogenetic reconstructions as described above and in Materials and methods. This allows us to infer orthology relationships between mouse and human sequences. Two sequences were considered as orthologs if they are more closely related to each other than to any other mouse or human sequences. This can be easily detected in the phylogenetic trees, as the two sequences will form an exclusive monophyletic group (Figure 2a). Among the 125 human sequences, 94 can be accurately related to 1 (or in a few cases 2, see below) mouse genes (Table 2) and, conversely, human orthologs can be confidently assigned to 93 of the 102 mouse genes (Table 5). Among the 31 human genes and 9 mouse genes that do not show clear orthology relationships to any mouse or human genes, respectively, 8 human genes and 6 mouse genes are members of families in which phylogenetic relationships are uncertain - the Mesp, E12 and Coe families (Figure 2b and Additional data). The Mesp family contains four human genes and three mouse genes, the E12 family seven human and four mouse genes, and the Coe family four human and four mouse genes. Some of these genes cannot be clearly linked to each other (see Figure 2b for an example). It is, however, conceivable that such relationships do exist but that phylogenetic reconstruction methods fail to detect them. We therefore consider that, in the Mesp family for example (Figure 2b), three of the four human genes correspond to the three mouse genes, and so, to date, one human gene lacks an ortholog among the cloned mouse genes.

Figure 2.

Some examples of phylogenetic relationships among human and mouse bHLH. Rooted NJ trees are shown. Numbers above branches indicate per cent support in bootstrap analyses (1,000 replicates). As in Figure 1, the rooting should be considered arbitrary. Branch lengths are proportional to distance between sequences. Mouse genes are shown in red, human genes in blue, and other species in black. Species abreviations are as followed: Br, Brachydanio rerio; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Ci, Ciona intestinalis; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Gg, Gallus gallus; Tr, Takifugu rubripes; Xl, Xenopus laevis. (a) Evolutionary relationships among Atonal 'superfamily' members (see Figure 1). The different constituting families are pointed out. For sake of simplicity, only mouse, human and fly genes are shown. This tree is rooted using the closely related twist gene from mouse (see Figure 1) as outgroup. In all cases, a human and a mouse sequence cluster together with high bootstrap values, indicating orthology relationships. (b) Evolutionary relationships among Mesp family members. This tree is rooted using the closely related MATH1 gene from mouse (see Figure 1) as outgroup. Whereas one human and one mouse bHLH (N015926 and pMeso1, respectively) are clearly orthologs, there is no one-to-one relationship between two mouse bHLH (Mesp1 and Mesp2) and three human bHLH (N010356a, b, c), although these bHLH cluster together with a high bootstrap value. (c) Evolutionary relationships among TF4 and MLX family members. This tree is rooted using the closely related MITF gene from mouse (see Figure 1) as outgroup. Two human genes have clear mouse orthologs but two others (Q9HAP2 and N005106) have no such orthologs. (d) Evolutionary relationships among SCL family members. This tree is rooted using the closely related Hen1 gene (NSCL family) from mouse (see Figure 1) as outgroup. The Lyl1 and Lyl2 mouse genes are collectively orthologs to one human gene (P12980), indicating a probable gene duplication specific to mouse.

Applying the same reasoning to the E12 and Coe families leads us to conclude that at least 26 human genes (20% of the total) do not have orthologs among the mouse bHLH genes cloned to date and only 3 mouse bHLHs (3%) have no orthologs in the bHLH set we derived from the human genome sequence draft. Figure 2c shows a typical phylogenetic tree of a family containing human genes that lack mouse orthologs. The fact that only three mouse genes lack human orthologs strongly argues that, although our analysis was made on a draft version of the human genome sequence, the set of bHLH we retrieved is likely to be almost complete, and hence gives a highly accurate view of the bHLH repertoire of a human being. Additional BLAST searches for human orthologs of the three mouse bHLHs that lacked orthologs (Scleraxis, Dermo-1 and S-Myc) were unsuccessful, suggesting that these orthologs either do not exist in humans or are not in the draft sequence. We were recently made aware that there is some incompatibility between the current version of BLAST and the human genome sequence (probably due to the large number of Ns (unassigned nucleotides) in the sequence), which makes BLAST unable to locate some of the best or even exact matches of small query sequences (J.A.M. Leunissen, personal communication). This may explain why we missed the four genes cited above, and also why, in a few cases, we were unable to find known cloned human genes in the genome sequence (see Table 2).

We also found eight cases in which two human genes group together (with high statistical support) to the exclusion of any other genes and are often orthologs of a single mouse gene (Figure 2b and Additional data). Conversely, we found two cases in which two mouse genes are, collectively, orthologs of a single human gene (Figure 2d). This may reveal relatively recent duplications specific to the human or mouse lineage. In agreement with this, in all cases amino-acid identity between the two duplicates is high and is not confined to the bHLH. In addition, we found that in two cases (human sequences Q9UH92/N005106 and Q02363/N005999), one of the two duplicates lacks introns. The two copies are, furthermore, on different chromosomes. This strongly suggests that the duplications have occurred by retrotransposition, a type of event that appears to be rather frequent in humans [26]. In both cases, the copy lacking introns has stop codons in the bHLH, suggesting that it is a pseudogene.

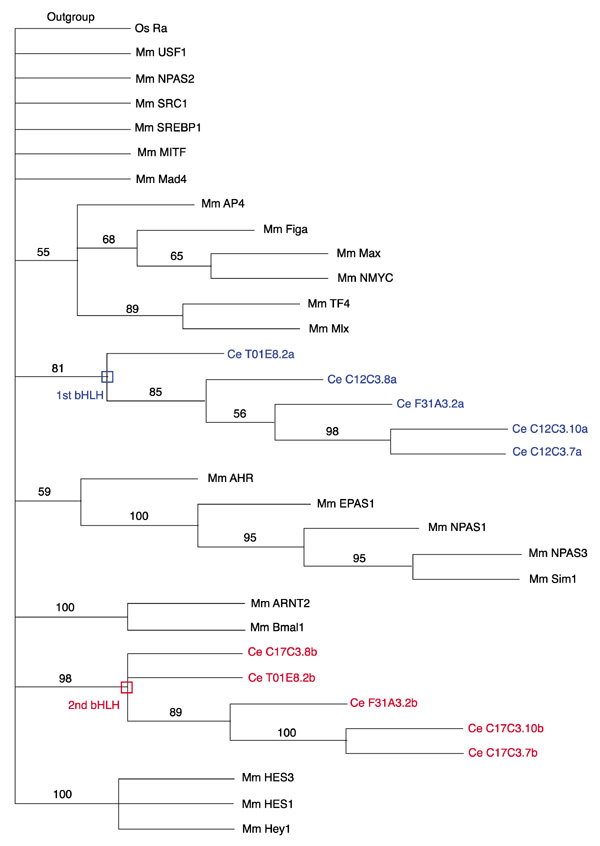

Proteins with two bHLHs

Among the 39 bHLH from the worm, 6 cannot be assigned to any family (orphan genes; see Tables 1 and 4). Five of these have an unusual architecture in they contain two bHLH domains (see also [27,28]). Phylogenetic analysis of these proteins indicates that they result from the duplication of an ancestral gene that already contained two bHLHs (Figure 3). Both bHLH domains are loosely related (on the basis of overall similarity) to HER proteins (group E; Figure 1), but their inclusion in group E is not supported by phylogenetic reconstruction (Figure 3). In addition, they lack the Orange domain, which is characteristic of most HER proteins and provides them with functional specificity [29]. They also lack the WRPW motif found in the carboxy-terminal region of almost all HER proteins and which allows interaction with the Groucho represser protein [30,31,32]. Moreover, they lack a conserved proline in the basic domain that confers DNA-binding specificity on the HER proteins [30].

Figure 3.

Worm proteins with two bHLH domains. A rooted NJ tree is shown that depicts the phylogenetic relationships of the five worm proteins with two bHLH domains. Mouse genes representative of some of the animal families have been included in this analysis. Rooting is as in Figure 1. Numbers above branches indicate per cent support in bootstrap analyses (1,000 replicates). As in Figure 1, the rooting should be considered arbitrary. Branch lengths are proportional to distance between sequences. Mm, Mus musculus; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans. The sequences of the first bHLH of each worm proteins are shown in blue, the second in red. Both form monophyletic groups with high bootstrap values, indicating that these proteins originate from an ancestral protein that already had two bHLH domains. There is, furthermore, a weaker support (40% bootstraps) for an association of the two bHLH domains into a monophyletic group (not shown in the figure, as only nodes with 50% or more support are shown), suggesting that the ancestral protein may have acquired its two bHLH domains through tandem duplication rather than by association of unrelated bHLH domains.

No other protein with two bHLHs has been reported in other metazoans and we were unable to find such proteins in the fly and human genomes. A protein with two bHLH domains is found in rice (Oryza sativa; protein P0498B01.20; accession number BAB61947) but its sequence is completely unrelated to that of the worm protein. Several bHLH proteins do contain other DNA-binding and/or dimerization domains in addition to their bHLH, such as the PAS domain, leucine zippers or the Coe domain [6,33,34]. It is conceivable that these domains may cooperate and thereby confer particular functions on the proteins containing them. Similarly, the presence of two bHLHs might modify the specificity of the proteins containing them.

The establishment of the bHLH gene family

bHLH genes are found in all major subdivisions of the eukaryotes: metazoans, fungi and plants. In contrast, no bHLH sequences can be found in prokaryotes. It seems, therefore, that the bHLH motif was established in early eukaryote evolution. We have found eight different bHLH genes in the unicellular eukaryote, the yeast S. cerevisiae. Most of these genes were already cloned and have been functionally characterized (reviewed in [7]). These genes often regulate biochemical pathways (such as phosphate utilization, phospholipid and amino-acid biosynthesis, glycolysis) through the transcriptional activation of more-or-less large sets of genes involved in these pathways [7]. Orthologs of these genes are found in other distantly related yeasts such as Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Kluyveromyces lactis (our unpublished observations), indicating an ancient origin for the different bHLH genes among yeasts.

The relatively small number of bHLH genes found in the unicellular yeast contrasts with the large number found in multicellular eukaryotes such as animals and plants. We report here the existence of 39 different bHLH genes in C. elegans, 58 in D. melanogaster, and 125 in humans. Preliminary analysis of plant genomes, in particular of Arabidopsis thaliana and O. sativa, similarly indicates a large number of bHLH genes (more than 100 in the completely sequenced genome of A. thaliana, our unpublished observations). This important diversification of the bHLH repertoire in animals and plants has occurred independently, as plant and animal bHLH genes are never found in a same family. The current view of eukaryote phylogeny suggests that fungi and animals are more closely related to each other than to the plants [35]. Nevertheless, we found that only two families contain both yeast and animal genes (see Table 1), suggesting that the common ancestor of fungi and animals may have possessed even fewer bHLH genes than the present-day yeasts. In the near future, the genome projects currently underway on various 'basal' eukaryotes (see [36,37]) may give important insights into the very early evolutionary history of the bHLH family.

We suggest that the diversification of bHLH genes is directly linked to the acquisition of multicellularity and hence to the recruitment of genes involved in cell functions such as metabolism into the developmental processes required to build multicellularity. Indeed, in animals, bHLH genes are generally involved in development and in tissue-specific gene regulation (reviewed in [1,2,3,4,5]). A similar situation may exist in plants, although very few bHLH genes have been functionally characterized. In addition, in both animals and plants, the diversification of bHLH genes seems to have occurred early in the evolution of these lineages.

Indeed, our phylogenetic analysis of animal bHLH genes shows that most belong to 44 different orthologous families. Of these families, 43 contain representatives from both protostomes and deuterostomes, and must therefore be represented in their common ancestor (often called Urbilateria) [38], which lived in pre-Cambrian times (600 million years ago). In addition, the few bHLH genes that have been cloned from cnidarians, which are not bilaterians, are clearly included in families (see the Twist, MyoD and ASC families in Additional data), suggesting that the establishment of at least some families predates the divergence of bilaterians and non-bilaterians. Further analyses of bHLH genes in cnidarians, sponges and slime molds will help to resolve the issue of the early evolution of bHLH genes in animals.

Our preliminary analyses of plant bHLH genes are consistent with an early diversification in plants, as in animals. Indeed, many A. thaliana bHLH genes have clear orthologs in a distantly related plant, O. sativa, whose genome has been partially sequenced (our unpublished observations). Arabidopsis is a eudicotyledon and Oryza a member of the Liliopsida (a monocotyledon), and given the phylogenetic relationships of these clades [39] this suggests that the possession of numerous bHLH genes might be ancestral to angiosperms. Further analysis of the evolution of bHLH in plants will require the completion of the genome projects currently underway on rice and tomato (a eudicotyledon of a different lineage from Arabidopsis), as well as the isolation of bHLH in a broader spectrum of plant species, in particular in basal angiosperms and non-angiosperms.

Evolution of bHLH genes in metazoans

Comparison of the bHLH repertoires found in the protostomes and the deuterostomes gives important insights in to the evolution of the bHLH family in metazoans. The conclusions that can be drawn are completely consistent with those presented in our previous work [8] but the inclusion of the probable complete set of bHLH from a vertebrate strengthens these conclusions.

Most families (43/44) contain genes from protostomes (fly and/or nematode) and deuterostomes, indicating that these families were already present in the last common ancestor of both protostomes and deuterostomes, that is, of all bilaterians. The fact that most families contain both protostome and deuterostome genes also suggests that there was no addition of new bHLH types in the corresponding lineages, and therefore no important diversification of the ancestral repertoire. A single family contains vertebrate members and no fly or worm genes. This may represent the emergence of new bHLH types in the vertebrate lineage, or alternatively a loss of ancestral types in both fly and nematode. The analysis of bHLH genes from molluscs or annelids might help to settle this question. It is now widely believed that the Bilateria (the triploblastic metazoans) are composed of three main lineages: deuterostomes (which include vertebrates and echinoderms) and protostomes, which themselves include two large groups, the ecdysozoans (for example, arthropods and nematodes) and the lophotrochozoans (for example, annelids, molluscs and flatworms) (reviewed in [16]). Therefore, the finding of ortholog genes in vertebrates and lophotrochozoans but not in fly and nematode would strongly suggest that gene loss(es) has (have) occurred in the ecdysozoan lineage.

Similarly, the case of families that contain vertebrate and either worm or fly genes is best explained by gene losses that occurred, inside the ecdysozoan clade, in either lineage after the arthropod/nematode divergence. This occurred in the fly lineage for very few families (4/44), suggesting the existence of a strong pressure to maintain the entire bHLH repertoire. The much larger number of families (13/44) that have vertebrate and fly members but no nematode representative suggests that extensive bHLH gene losses have occurred in the worm lineage. Strikingly, the worm lacks the important cellular and developmental regulator Myc. A similar absence of important developmental regulators, such as Hedgehog, Toll/IL-1 and JAK/STAT pathway elements has also been reported in the nematode [27]. In addition, a large number of nematode genes (6/39) cannot be clearly assigned to specific families (orphan genes). This is probably due to the high divergence rate reported for nematode genes in general [40,41] and which we found within our specific data set ([8] and data not shown).

Interestingly, however, some nematode sequences have diverged very little from their fly or mouse counterparts. These include the few functionally characterized C. elegans bHLH genes that show overall functional conservation with their vertebrate and/or fly orthologs; for example, the C. elegans orthologs of twist and myoD are involved in muscle formation [42,43], and the orthologs of atonal and NeuroD (lin-32 and cnd-1) have a role in nervous-system development [44,45]. The genetic control of developmental processes such as neurogenesis and myogenesis relies on small sets of interacting genes (syntagms) [46]. The function of syntagms crucially relies on specific molecular interactions among their members, hence imposing strong structural constraints on them and preventing structural diversification (for discussion on syntagms and evolution, see [47]). This may explain why such networks are strongly conserved throughout metazoan evolution [48,49] and why nematode genes involved in such networks have been subject to special constraints.

Duplication of bHLH genes in vertebrates

An extensive increase of bHLH family complexity has occurred in vertebrates: the most frequent number of different bHLH genes per family is one in fly (30/44) and worm (27/44), and two in human (14/44; but 20/44 human families do in fact contain more than two genes). Most bHLH families (32/44), as with other gene families, have more members in vertebrates than in other phyla (Table 1). Of these families, 14 (32%) contain four or more vertebrate genes (Table 1) and hence may reveal the occurrence of two whole-genome duplications (the 2R hypothesis) in early vertebrate evolution. In the most popular version, this is thought to have occurred by one duplication at the root of the vertebrates and a second in the Gnathostomata lineage, after its divergence from Agnatha (reviewed in [50]).

Several recent analyses, however, tend to refute (at least, do not support) this hypothesis (reviewed in [51]). For example, the current mammalian gene number estimations based on the human draft sequence, ESTs and comparisons with other vertebrates propose that the human genome would contain no more than 35,000 genes; that is, about twice the number of fly and worm [12]. Consistent with this, many gene families in vertebrates have fewer than four genes. This might, however, result from gene loss during or after the rounds of duplication [50]. In addition, phylogenetic analyses of gene families that comprise four members cast doubt on the 2R hypothesis.

As pointed out by Hughes [52], the presence of four members in a vertebrate gene family by itself does not support the genome duplication hypothesis. Support may only come from families whose phylogenetic tree shows a topology of the (AB) (CD) form, that is, two pairs of two closely related paralogs [52]. Hughes [52] discussed the phylogenies of 13 protein families important in development, and found that only one of them shows an (AB) (CD) topology. Similar results were recently obtained by Martin [53] and Hughes et al. [54] on several other families with much more rigorous phylogenetic tests. These results have led to the alternative hypothesis that the abundance of duplicated genes in vertebrates compared to invertebrates may be due to a high rate of local duplications, rather than entire genome duplications (reviewed in [51]). The analysis of additional gene families may help to discriminate between these hypotheses. Phylogenetic trees of the 14 bHLH families that contain four or more members do not clearly show such (AB) (CD) topologies (see Additional data). We have, however, to note that the phylogenies inside families often have only poor resolution and it is therefore difficult to draw firm conclusions from them. Nevertheless, our data clearly do not support the 2R hypothesis.

Conclusions

We identified the probable full complement of bHLH in three different metazoans that are representative of the two major subdivisions of the animal kingdom, the protostomes (C. elegans and D. melanogaster) and the deuterostomes (humans). Most of these genes belong to one of 44 orthology families. Most of these families (43/44) have protostome and deuterostome members, and must therefore have been represented in their common ancestor before the Cambrian radiation which saw the emergence of all present-day phyla, and many extinct ones. Morphologically, these ancestors (also called Urbilateria [38]) were probably coelomates with antero-posterior and dorso-ventral polarity, rudimentary appendages, some form of metamerism, a heart, sense organs such as photoreceptors and a complex nervous system [55]. Genetically, they possessed numerous homeobox genes (among which are at least seven Hox genes [56]), several intercellular signaling pathways (TGF-β, Hedgehog, Notch, EGF), at least four Pax genes [25], and 38 C2H2 zinc-finger proteins [57]. Our analysis suggests that their genome contained at least 43 different bHLH genes. The functional conservation that is often observed between protostome and deuterostome orthologs indicates that some of the developmental functions associated with the present-day genes were already established in Urbilateria, further indicating the genomic and developmental complexity of these ancient ancestors.

Materials and methods

BLAST searches

The full set of bHLH sequences in the fly, worm, and yeast were obtained mostly by BLASTP searches [13] against the new releases of the complete genomic sequences of C. elegans [58], D. melanogaster [59], and S. cerevisiae [59]. Mouse bHLH genes were obtained by BLASTP searches [13] against the more recent versions of the non-redundant database at NCBI [59] and the Sanger protein databases [60]. In addition, we retrieved and analyzed all the bHLHs from these organisms that are listed in the SMART database [14,15,61]. The comparison with the lists of bHLHs found in the SMART database and published by other groups [20,27,62,63] strongly suggests that we retrieved the full set of bHLH genes present in the fly, yeast, and worm genomes, as well as all the cloned mouse bHLH genes to date.

TBLASTN searches were done at the NCBI on the human genome [64] and at the Doe Joint Genomic Institute (University of California and the US Department of Energy) for the pufferfish and sea squirt genomes [65]. We used as query two different sequences (usually one from mouse and one from fly or worm) of each of the families we defined previously [8]. Searches were done at two stringencies, E < 1 and E < 0.01, with all other parameters set to default. The BLAST searches detected some sequences that display only low overall similarity with the query, or similarities only to a part of the bHLH domain. We checked these sequences by hand and found that in all cases they did not correspond to bona fide bHLH domains. We hence did not include these sequences in our subsequent analyses. During the course of our work, four different successive drafts of the human genome have become available. The data presented in this paper come from the third version (April 2001). Careful examination of the fourth version (July 2001) did not give additional data. A final check has been done on the latest release (version 6) in November 2001 with no significant changes, except that some contigs have been renamed and two sequences were no longer found. We do not include these two sequences (which were closely related duplications of existing bHLH genes) as they may represent artifacts of the genome sequence assembly process. We cannot exclude the possibility, however, that they are bona fide bHLH genes that were no longer detected as a result of limitations of the current version of BLAST (see Results and discussion).

Phylogenetic analyses

Protein alignments were made using ClustalW [66] with no adjustment of the default parameters and were subsequently edited and manually improved in Genedoc Multiple Sequence Alignment Editor and Shading Utility (Version 2.6.001) [67]. The evaluation of percentage conservation of residues in multiple sequence alignments was done using the Blosum62 Similarity Scoring Table [68]. Only the bHLH motif (determined as in [69]), plus a few flanking amino acids, was used in most of our analyses because the remaining parts of proteins from independent clades are either not homologous or have diverged so much that the alignments are meaningless. The facilities of the Belgian EMBnet Node [70] were used for sequence analysis using Genedoc software and for most of the protein alignments using ClustalW.

Distance trees were constructed with the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm [71] using PAUP 4.0 [72] based on a Dayhoff PAM 250 distance matrix [73]. The resultant trees were bootstrapped (1,000 bootstrap replicates) to provide information about their statistical reliability. Bootstraps were made with PAUP 4.0, parameters set to default values. Given the large number of sequences (> 300), we were unable, because of computer calculation limitations, to perform maximum-parsimony (MP) and maximum-likelihood (ML) analyses on the multiple alignment that contains all sequences. We made several additional alignments that include only those bHLH sequences that belong to a particular high-order group (Figure 1) [8]. NJ, MP and ML trees were constructed from these alignments and were fully congruent with the NJ trees constructed from the general alignments. The MP analysis was performed using PAUP 4.0 with the following settings: heuristic search over 100 bootstrap replicates, MAXTREES set up to 1,000 due to computer limitations, other parameters set to default values. Maximum likelihood (ML) was done using TreePuzzle 4.0.2 [74]. The ML was performed using the quartet-puzzling tree-search procedure with 25,000 puzzling steps, using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model of substitution [75], the frequencies of amino acids being estimated from the data set [74], with an uniform rate of substitution. The trees were displayed with the Tree view program (version 1.5) [76], saved as PICT files, converted into JPEG files using Graphic Converter, and then annotated using Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator.

Additional data files

Additional data files are available with the online version of this paper as follows:

Multiple alignments (in rich text format) on which the trees displayed in the figures are based.

A list of all bHLH sequences from human in rich text format

Multiple alignments for each family of bHLH proteins: the Achaete-Scute a family, the Achaete-Scute b family, the AHR family, the AP4 family, the ARNT family, the Atonal family, the Beta3 and Oligo families, the Bmal family, the Clock family, the E12/E47 family, the Extramacrochaete family, the Enhancer of split family, the Fig alpha family, the Hairy family, the Hand family, the Hey family, the Mad and Mnt families, the Max family, the Mesp family, the Mist family, the MITF family, the Myc family, the Myod family, the MyoR family, the Net family, the NeuroD family, the Neurogenin family, the NSCL family, the Paraxis family, the PTF a and b families, the SCL family, the SRC family, the SREBP family, the TF4 and Mlx families, the Trh, Hif, and Sim families, the Twist family, and the USF family.

Representative phylogenetic trees (NJ trees bootstrapped 1,000 times to provide statistical support to the nodes, usually rooted with a sequence from a closely related family. In a few cases, closely related families are shown in the same phylogenetic tree) of each family of bHLH proteins: the Achaete-Scute a family, the Achaete-Scute b family, the AHR family, the ARNT family, the Atonal family, the Beta3, Mist, and Oligo families, the Bmal family, the Clock family, the E12/E47 family, the Extramacrochaete family, the Enhancer of split family, the Fig alpha family, the Hairy family, the Hand family, the Hey family, the Mad and Mnt families, the Max family, the Mesp family, the MITF family, the Myc family, the Myod family, the MyoR family, the Net family, the NeuroD family, the Neurogenin family, the NSCL family, the Paraxis family, the PTF a and b families, the SCL family, the SRC family, the SREBP family, the TF4 and Mlx families, the Trh, Hif, and Sim families, the Twist family, and the USF family.

Species name abbreviations are as in the figure legends and as below: Av, Asteris vulgaris; AVIM, avian myelocytomatosis virus CMII; Bb, Branchiostoma belcheri; Bf, Branchiostoma floridae; Bm, Bombyx mori (domestic silkworm); Caebr, Caenorhabditis briggsae; Cc, Ceratitis capitata; Cp, Cynops pyrrhogaster; Cs, Cupiennius salei; Cyca, Cyprinus carpio; Ds, Drosophila simulans; Dv, Drosophila virilis; Dy, Drosophila yakuba; Hr, Halocynthia roretzi; Hv, Hydra vulgaris (Hydra attenuata); Ilo, Ilyanassa obsoleta; Jc, Juonia coenia (Precis coenia) (peacock butterfly); Kl, Kluyveromyces lactis; Lv, Lytechinus variegatus (green urchin); Nv, Notophtalmus viridens; Ol, Oryzias latipes (Japanese medaka); Om, Oncorhyncus mikis; pc, Podocorine carnea; Pv, Patella vulgata (common limpet); Rn, Rattus norvegicus; Sb, Spermophilus beecheyi; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast); Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Spu, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (purple urchin); St, Silurana tropicalis; Tc, Tribolium castaneum; Tricho, Trichinella spiralis

Supplementary Material

Multiple alignment on which Figure 1 is based

A list of all bHLH sequences from human

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Achaete-Scute a family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Achaete-Scute b family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of AHR family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of AP4 family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of ARNT family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Atonal family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Beta3 and Oligo families proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Bmal family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Clock family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of E12/E47 family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Extramacrochaete family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Enhancer of split family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Fig alpha family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Hairy family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Hand family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Hey family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Mad and Mnt families proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Max family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Masp family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Mist family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of MITF family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Myc family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Myod family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Myor family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Net family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of NeuroD family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Neurogenin family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of NSCL family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Paraxis family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of PTF a and b families proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of SCL family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of SRC family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of SREBP family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of TF4 and Mlx families proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Trh, Hif, and Sim families proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of Twist family proteins

Multiple Alignment of the bHLH of USF family proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Achaete-Scute a family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Achaete-Scute b family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the AHR family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the ARNT family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Atonal family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Beta3, Mist, and Oligo families of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Bmal family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Clock family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the E12/E47 family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Extramacrochaete family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Enhancer of split family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Fig alpha family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Hairy family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Hand family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Hey family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Mad and Mnt families of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Max family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Mesp family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the MITF family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Myc family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Myod family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the MyoR family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Net family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the NeuroD family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Neurogenin family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the NSCL family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Paraxis family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the PTF a and b families of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the SCL family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the SRC family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the SREBP family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the TF4 and Mlx families of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Trh, Hif, and Sim families of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the Twist family of bHLH proteins

Representative phylogenetic tree of the USF family of bHLH proteins

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Herzog, Marc Colet and André Adoutte for support. We are grateful to Lionel Christiaen who made us aware of the Takifugu and Ciona genome projects, and to Marc Colet and Robert Herzog for comments on the manuscript. This work has been supported by the Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs (V.L.) and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut Français de la Biodiversité, and the Université Paris-Sud (M.V.).

References

- Weintraub H. The MyoD family and myogenesis: redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell. 1993;3:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan YN, Jan LY. HLH proteins, fly neurogenesis, and vertebrate myogenesis. Cell. 1993;3:827–830. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90525-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan BA, Bellen HJ. Doing the MATH: is the mouse a good model for fly development? Genes Dev. 2000;3:1852–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;3:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort M, Ledent V. The evolution of neural basic helix-loop-helix proteins. The Scientific World. 2001;3:396–426. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2001.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley WR, Fitch WM. A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;3:5172–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KA, Lopez JM. Saccharomyces cerevisiae basic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;3:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent V, Vervoort M. The basic helix-loop-helix protein family: comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis. Genome Res. 2001;3:754–770. doi: 10.1101/gr.177001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;3:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF. et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;3:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;3:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Sutton GG, Kerlavage AR, Smith HO, Hunkapiller M. Shotgun sequencing of the human genome. Science. 1998;3:1540–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;3:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Copley RR, Doerks T, Ponting CP, Bork P. SMART: a web-based tool for the study of genetically mobile domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;3:231–234. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;3:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adoutte A, Balavoine G, Lartillot N, Lespinet O, Prud'homme B, de Rosa R. The new animal phylogeny: reliability and implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;3:4453–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM. Distinguishing homologous from analogous proteins. Syst Zool. 1970;3:99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle RF, Feng DF, Tsang S, Cho G, Little E. Determining divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science. 1996;3:470–477. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng DF, Cho G, Doolittle RF. Determining divergence times with a protein clock: update and reevaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;3:13028–13033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK, Fortini ME, Li PW, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W. et al. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. 2000;3:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;3:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervitz SA, Aravind L, Sherlock G, Ball CA, Koonin EV, Dwight SS, Harris MA, Dolinski K, Mohr S, Smith T. et al. Comparison of the complete protein sets of worm and yeast: orthology and divergence. Science. 1998;3:2022–2028. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruepp A, Graml W, Santos-Martinez ML, Koretke KK, Volker C, Mewes HW, Frishman D, Stocker S, Lupas AN, Baumeister W. The genome sequence of the thermoacidophilic scavenger Thermoplasma acidophilum. Nature. 2000;3:508–513. doi: 10.1038/35035069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski LB, Golding GB. The closest BLAST hit is often not the nearest neighbor. J Mol Evol. 2001;3:540–542. doi: 10.1007/s002390010184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliot B, de Vargas C, Miller D. Evolution of homeobox genes: Q50 Paired-like genes founded the Paired class. Dev Genes Evol. 1999;3:186–197. doi: 10.1007/s004270050243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ED, Chakravarti A. The human genome sequence expedition: views from the ''base camp". Genome Res. 2001;3:645–651. doi: 10.1101/gr.188701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G., Hobert O. The taxonomy of developmental control in Caenorhabditiselegans. Science. 1998;3:2033–2041. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper S, Kenyon C. REF-1, a protein with two bHLH domains, alters the pattern of cell fusion in C. elegans by regulating Hox protein activity. Development. 2001;3:1793–1804. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]