Abstract

Background:

In Confucian-influenced Asian societies, explicit end-of-life conversations are uncommon and family involvement in decision-making is crucial, which complicates the adoption of culturally sensitive advance care planning.

Aim:

To develop a consensus definition of advance care planning and provide recommendations for patient-centered and family-based initiatives in Asia.

Design:

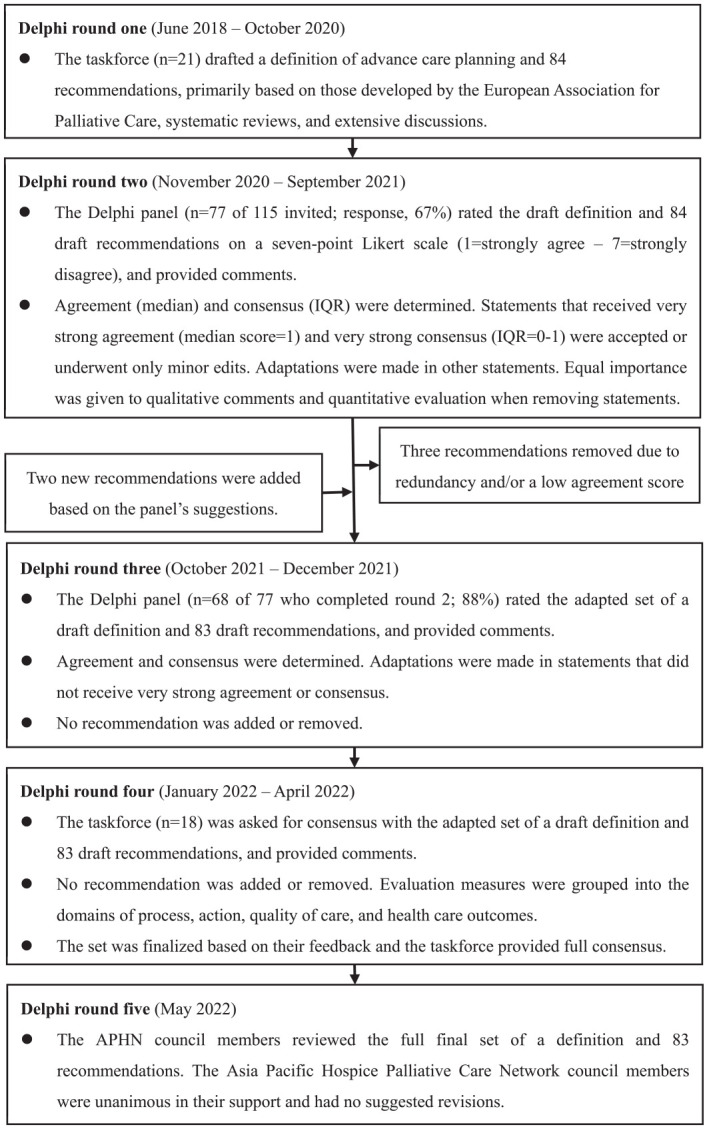

A five-round Delphi study was performed. The rating of a definition and 84 recommendations developed based on systematic reviews was performed by experts with clinical or research expertise using a 7-point Likert scale. A median = 1 and an inter-quartile range = 0–1 were considered very strong agreement and very strong consensus, respectively.

Setting/participants:

The Delphi study was carried out by multidisciplinary experts on advance care planning in five Asian sectors (Hong Kong/Japan/Korea/Singapore/Taiwan).

Results:

Seventy-seven of 115 (67%) experts rated the statements. Advance care planning is defined as “a process that enables individuals to identify their values, to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these values, goals, and preferences with family and/or other closely related persons, and health-care providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate.” Recommendations in the domains of considerations for a person-centered and family-based approach, as well as elements, roles and tasks, timing for initiative, policy and regulation, and evaluations received high levels of agreement and consensus.

Conclusions:

Our definition and recommendations can guide practice, education, research, and policy-making in advance care planning for Asian populations. Our findings will aid future research in crafting culturally sensitive advance care planning interventions, ensuring Asians receive value-aligned care.

Keywords: Advance care planning, Delphi, definition, recommendations, Asia

Key statements

What is already known about the topic?

As in Western countries’ health-care systems, advance care planning is being increasingly implemented in Asian ones, but consensus on its definition and recommendations based on Asian culture are lacking.

In high-context, Confucian-influenced Asian societies, explicit conversations about end-of-life care with patients are not always the norm. Family involvement is crucial in decision-making. Health-care providers in Asia uncommonly involve patients in advance care planning, partly due to their lack of knowledge and skills in advance care planning, personal uneasiness, fear of conflicts with families and their legal consequences, and the lack of a standard system for advance care planning.

What this paper adds

A key domain not previously highlighted in Western Delphi studies is “a person-centered and family-based approach” that facilitates families’ involvement to support an individual’s engagement in advance care planning and the attainment of the individual’s best interest through shared decision-making. Treatment preferences in Asian contexts are often shaped by relationships and responsibilities toward others, with families and health-care providers supporting individuals to meaningfully participate, even in the presence of physical or cognitive impairments.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

Our definition and recommendations can guide clinical practice, education, research, and policy-making in advance care planning, not only in the Asian sectors included in our study, but also in regions with Asian residents and other areas where implicit communication and family-centered decision-making are valued.

Our findings, combined with the existing evidence, will help future investigations to develop culturally sensitive advance care planning interventions, identify appropriate outcomes, and build an infrastructure where Asian individuals receive care consistent with their values, goals, and preferences.

Introduction

Advance care planning enables individuals to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, discuss these with family and health-care providers, and record and review them if appropriate. 1 While debates exist regarding its usefulness, studies have shown that advance care planning can improve various health-care outcomes, including patient-provider communication, documentation of preferences, patient’s satisfaction, mental health, and health-care utilization.2 –9

The concept and practice of advance care planning vary considerably across different settings, cultures, and countries. In 2017, the European Association for Palliative Care and researchers from North America and other Western countries independently proposed international consensus definitions and recommendations for advance care planning.1,10,11 Both studies emphasized individual autonomy by empowering individuals to express their own care decisions through a personalized, value-centered approach, followed by documentation and the continuous review of preferences. These studies offered useful consensus focused on enabling individuals to define and share their values, goals, and preferences for future medical care. However, the panel consisted of experts from Western countries with no representation from Asia.

Asia has distinct cultural norms compared with the West. Particularly in high-context, Confucian-influenced societies, explicit conversations about end-of-life care with patients are not always the norm, and family involvement is crucial in decision-making. 12 This is partly due to “filial piety,” where children are expected to care for their parents and make decisions in their best interest.13,14 In these societies, concerns arise about whether Western-origin advance care planning aligns with family-centered values, as patient autonomy is often secondary to family influence.12,15,16 Balancing family involvement with patient autonomy is a critical focus in the region. A recent systematic review revealed that while Asian health-care providers recognize the importance of advance care planning, they uncommonly involve patients and struggle to initiate it. 17 Challenges include a lack of knowledge and skills, personal discomfort, fear of family conflicts and legal repercussions, and the absence of standardized systems. Most studies in Asia report low engagement and delayed initiation of advance care planning by health-care providers, with patients’ preferences rarely documented in medical records.17 –19 Cross-cultural differences in patient autonomy and concepts of a good death are shaped by regional religions and beliefs.20 –22 Therefore, developing definitions and recommendations regarding the elements, roles, timing, policy, regulation, and evaluation of advance care planning would lay a foundation for future activities in Asia, and benefit other regions that value implicit communication and family-centered decision-making.

The aim of this study was to develop a consensus definition of advance care planning and present recommendations for use by health-care providers, educators, policymakers, and researchers across diverse populations, disease categories, and cultures in Confucian-influenced Asian regions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Delphi consensus process on the definitions and recommendations of advance care planning. IQR: inter-quartile range.

Methods

We conducted a Delphi study across five Asian countries/regions (“sectors”): Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. These sectors were chosen due to their existing advance care planning practices and shared Confucian cultures. Supported by the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network, this consensus project was chaired by MM and YK. They invited 21 experts in advance care planning from the five sectors to form an interdisciplinary taskforce, with expertise in oncology, palliative care, internal medicine, family medicine, nursing, psychology, ethics, and law. These experts were identified based on their clinical roles, publication citation records, or through professional contacts. Most taskforce members, excluding the co-chairs, were included in the expert panel for the Delphi study detailed in round 2.

We also invited the co-chairs of the previous European Association for Palliative Care Delphi study on advance care planning (IK/JR) and an Asian researcher (DM), who has conducted systematic reviews on advance care planning among Asians, to offer methodological insights.1,17,23

Design and outcomes

We followed the five-round design and mixed-method approach from the European Association for Palliative Care Delphi study on advance care planning, adhering to standard guidelines for conducting and reporting Delphi Studies.1,24 Rounds 1 and 5 used qualitative methods, whereas rounds 2–4 employed quantitative assessment. Although we initially anticipated five rounds, 1 the exact number of rounds was determined by consensus. The structured rounds featured anonymity, iteration, and controlled feedback.25,26

Round 1

To facilitate Delphi discussions, we summarized the current status of advance care planning in Asia. 27 In June 2018, the taskforce reviewed both online and in person the draft definition and five core domains of advance care planning (elements, roles and tasks, timing, policy and regulation, and evaluation) developed by the European Association for Palliative Care. 1 We adopted the European study’s structure because it offers a comprehensive framework to address the multifaceted challenges of advance care planning in Asia. This framework was extensively modified based on additional evidence from another Western Delphi study10,11 and systematic reviews of advance care planning studies in both English and local languages from the five sectors.17,23,27 –29 A new domain, “recommended consideration for a person-centered and family-based approach in advance care planning,” was added to reflect the emphasis on harmony and relational autonomy in Asian cultures.12,28 This domain includes four recommendations to support individual engagement in advance care planning through family involvement and shared decision-making. Relational autonomy, which places the individual within a socially embedded network, is relevant in both Asia and the West.30 –35 As for the evaluation domain, we focused on identifying overarching outcome constructs rather than individual measures, as standardized validated measures for advance care planning are still lacking.1,10 The taskforce reviewed the detailed evaluation structure of another Western Delphi study in order to identify additional items pertinent to advance care planning in Asia. 10

The draft was discussed and revised iteratively by the taskforce. The first version was created in English and then translated into Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Korean through a rigorous forward-backward translation method conducted by bilinguals. Both the English and translated versions were reviewed by expert panel representatives in each sector to ensure clarity and relevance. In Hong Kong and Singapore, the English version was used for further examination. This process resulted in a definition of advance care planning and 84 draft recommendations (see Supplemental Material). After round 1, three members withdrew from the taskforce due to other commitments.

Round 2

From November 2020 to April 2021, the first version was presented to an expanded expert panel, including the majority of taskforce members, via an online questionnaire. Experts were identified through publication records and citation analysis, or the taskforce’s professional network. Our goal was to form an interdisciplinary group of advance care planning experts, encompassing research, practice, and education, with backgrounds in medicine, nursing, palliative care, psychology, ethics, law, and policy. The panel also included a patient representative familiar with advance care planning. We invited 115 experts from all five sectors, of whom 77 completed the questionnaire (response rate = 67%).

Panelists rated their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree) and provided feedback in free text boxes. Agreement was measured by the percentage of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing, and by the median score. A median score of 1 indicated very strong agreement, and median of 2 indicated strong agreement. 1 The ad hoc criterion for the percentage of agreement was set at 75% based on previous systematic reviews and Delphi study guidelines.24,36 Consensus was calculated using the interquartile range (IQR), with IQR of 0-1 indicating very strong consensus, and IQR of 2 indicating strong consensus. 1 Open-text comments were analyzed by the taskforce.

Recommendations with “very strong agreement” and “very strong consensus” were accepted with minimal edits. Other recommendations were adapted or removed to reduce redundancy. In rounds 2 and 3, the taskforce considered both qualitative comments and quantitative evaluation equally when deciding whether to remove items. While quantitative evaluations were considered, statements were not removed solely based on cutoff values for agreement. Statements were retained if they were deemed conceptually important. Bilingual taskforce members translated free text comments into English. Newly added statements were translated into Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Korean through formal translation processes. The taskforce kept procedures for unresolved consensus open throughout the study.

Round 3

To maintain consistency, only panelists who responded in round 2 rated the revised statements in this round. In October 2021, they received both the original and revised sets of definitions and recommendations, including agreement and consensus findings. Panelists rated agreement on a 7-point Likert scale and provided feedback. If a recommendation had received very strong agreement and very strong consensus in round 2, experts could either select the default option (the median score from the previous round) or rate the recommendation again. Of the 77 panelists from round 2, 68 responded in this round (response rate = 88%).

Round 4

Recommendations with very strong agreement and very strong consensus were accepted or minimally edited. MM and YK adapted the other recommendations based on panelists’ comments. The revised set was sent to 18 taskforce members in January 2022, with 16 either indicating agreement (“yes” or “no”) or suggesting further improvements.

Round 5

The set of definitions and recommendations was adapted based on taskforce feedback and reviewed by the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network Council in May 2022.

Ethical consideration

Ethical and scientific validity were confirmed by the institutional review board of Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital, Japan, and by review boards in other sectors. The Delphi process utilized an anonymous online survey platform supported by The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Participants indicated their informed consent by checking a box on the platform prior to starting the survey.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the Delphi panel experts are summarized in Table 1. In round 2, the extended/brief definition received a median score of 2 and IQR of 1. Of the 84 recommendations, 20 (24%) received very strong agreement and very strong consensus, 42 (50%) received strong agreement and very strong consensus, and 20 (24%) received strong agreement and strong consensus. One item received strong agreement, but did not reach consensus (IQR = 2.5). Adaptations to the definition clarified terminology, with detailed descriptions added in the footnote. After round 2, two recommendations were added, and three were removed due to redundancy and/or a low agreement score. In round 3, the definition and 30 (36%) of the 83 recommendations received very strong agreement and very strong consensus, including all recommendations for a person-centered and family-based approach. Forty-nine (59%) received strong agreement and very strong consensus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Delphi panel experts (round 2).

| Characteristics | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 25–29 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–34 | 2 | 3 |

| 35–39 | 9 | 12 |

| 40–44 | 20 | 26 |

| 45–49 | 16 | 21 |

| 50–54 | 13 | 17 |

| 55–59 | 7 | 9 |

| 60–64 | 3 | 4 |

| 65–69 | 2 | 3 |

| 70–74 | 1 | 1 |

| Age not stated | 4 | 5 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 42 | 55 |

| Male | 34 | 44 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 1 |

| Profession/primary discipline (multiple options available) | ||

| Physician | 39 | 51 |

| Nurse | 11 | 14 |

| Lawyer/legal scholar | 5 | 6 |

| Researcher | 10 | 13 |

| Psychologist | 4 | 5 |

| Medical social worker | 9 | 12 |

| Other (ACP trainer/specialist/coordinator; administrator; ethicist; patient/patient supporter; patient association leader; philanthropic worker; physiotherapist; policy maker) |

11 | 14 |

| Primary practice (multiple options available) | ||

| Clinician | 48 | 62 |

| Educator | 25 | 32 |

| Researcher | 24 | 31 |

| Policy maker | 5 | 6 |

| Other (ACP facilitator; court case management; health-care administrator; implementation of ACP across settings; manager; program management; service provider) |

9 | 12 |

ACP: advance care planning.

In round 4, advance care planning evaluation measures were categorized according to those proposed by a prior study. 10 Of the extended/brief definitions and 83 recommendations, 69 (81%) received full agreement from the taskforce, while 16 received agreement from 11 to 15 members. Feedback emphasized retaining all recommendations from round 3 with minor phrasing adjustments, which were incorporated. This led to a final set of recommendations that achieved consensus among the entire taskforce. The final set included an extended/brief definition of advance care planning and 83 recommendations, with seven receiving less than 75% agreement in round 3 (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Final set of recommendations on advance care planning with ratings, as provided by the panel in Delphi round 3 (agreement ⩾75%).

| Agreement (%) | Agreement (median) | IQR | Comments that were written by the panel in rounds 2 and 3 (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | ||||

| Extended definition: Advance care planning is a process that enables individuals who have decisional capacity a to identify their values, to reflect upon the meanings and consequences of serious illness scenarios, to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, and to discuss these with family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers. ACP addresses individuals’ concerns across the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. It encourages individuals to identify a personal representative c and to record and regularly review any preferences, so that their preferences can be taken into account should they, at some point, be unable to make their own decisions. |

91 | 1 | 1 | 30 |

| Brief definition: Advance care planning is a process that enables individuals to identify their values, to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these values, goals, and preferences with family and/or other closely related persons b and health-care providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate. |

94 | 1 | 1 | |

| Recommended elements of ACP | ||||

| 1. ACP is relevant for both patients and healthy individuals. | 79 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 2. The individual’s preferences should be explored regarding the extent to which ACP is discussed, as well as who to include in the ACP discussions. | 84 | 1 | 1 | 25 |

| 3. The ACP process includes an exploration of the understanding of ACP among the individual and family and/or other closely related persons b if the individual allows, and an explanation of the aims, elements, benefits, and limitations of ACP, as well as its legal status, if necessary. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| 4. ACP should be adapted to the individual’s readiness to engage in the ACP process, and if allowed by the individual, the family and/or other closely related persons b may also engage in the ACP process. | 96 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 5. ACP includes the exploration of health-related experiences, knowledge, concerns, and personal values of the individual across the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. | 97 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 6. ACP includes exploring goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care. | 97 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 7. Where appropriate, ACP includes information about diagnosis, disease course, prognosis, advantages and disadvantages of possible treatment, and care options. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 8. ACP includes clarification of goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care according to the individual’s degree of readiness; if appropriate, ACP includes an exploration to the extent to which these goals and preferences are realistic. | 91 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 9. ACP includes discussing the option and role of the personal representative, c who might act on behalf of the individual when he or she loses decisional capacity, according to relevant laws or social conventions in each sector. | 88 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 11. ACP might include the appointment of a personal representative(s) c and the documentation of such an appointment. | 88 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 12. ACP includes providing information about an advance directive, d and might include its completion according to relevant laws or social conventions in each sector. | 81 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| 13. The content of ACP discussions is encouraged to be documented with permission of the individual. | 78 | 2 | 1 | 26 |

| 14. ACP includes supporting an individual to share their values, goals, and preferences with family and/or other closely related persons b and health-care providers, where appropriate. This includes sharing documentation of the ACP discussion with whosoever the individual wishes to. | 82 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Recommended consideration for a person-centered and family-based approach in ACP | ||||

| 15. It is desirable that ACP discussions between the individual and health-care providers also include people chosen by the individual to engage in the ACP process. These people may include family and/or other closely related persons. b | 93 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| 16. When assisting individuals in making person-centered decisions, health-care providers should understand that individuals’ treatment preferences may sometimes be made in the context of their relationship with and responsibilities for others. | 96 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 17. ACP helps promote mutual understanding and shared decision-making between the individual and family and/or other closely related persons b regarding future medical treatment and care. | 94 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 18. Health-care providers and family and/or other closely related persons b should provide maximum support for individuals with physical or partial cognitive impairment to meaningfully participate in ACP. This may include revisiting the ACP discussion at various timepoints, using communication aids, and checking the individual’s capacity to understand and register information, to weigh options, and to communicate reasoning underlying decisions made. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Recommended roles and tasks | ||||

| 19. It is desirable for health-care providers to build a trusting relationship with individuals and their family and/or other closely related persons b before initiating ACP conversations, whenever possible. | 84 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 20. Health-care providers should ensure that the individual has a sufficient decision-making capacity to engage in the ACP process. | 87 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| 21. Health-care providers should adopt a person-centered approach when engaging in ACP conversation with an individual and, if the individual wishes, their family and/or other closely related persons b to the extent desired by the individual; this approach requires tailoring the ACP conversation to the individual’s health literacy, style of communication, and personal values and preferences. | 96 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 22. Health-care providers should facilitate a shared understanding between the individual(s) and family and/or other closely related persons, b whenever possible, and ensure that ultimately, the individual’s preferences are respected. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| 23. Health-care providers should be attuned to the emotions of individuals and their family and/or other closely related persons b in the process of ACP. | 91 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 24. Health-care providers need to have the necessary communication skills and show an openness to talk about diagnosis, prognosis, and death and dying with individuals and their families and/or other closely related persons. b | 99 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 25. Health-care providers should provide individuals and their families and/or other closely related persons b with clear and coherent information concerning ACP. | 91 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 26. Where appropriate, a multidisciplinary approach is encouraged to provide support in the ACP process, and this may include clinicians and/or trained non-clinician facilitators. | 81 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| 27. The initiation of an ACP conversation can occur in any setting not just in health-care systems. | 87 | 1·5 | 1 | 14 |

| 28. Appropriate health-care providers are needed for the clinical elements of ACP, when necessary, such as discussing diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and care options, exploring the extent to which goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care are realistic, and documenting the discussion in the medical file of the patient. | 88 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| 29. In supporting the practice of ACP, there should be continual education for health-care providers about bioethical issues, knowledge, communication skills, regulatory frameworks, and implementation workflows related to ACP. | 99 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 30. Health-care providers should share contents of discussions upon the transition of care across settings. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 31. Within the health-care system, the health-care team in charge of an individual should encourage opportunities for ACP facilitation, according to the readiness of an individual. | 97 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 32. Colleagues with appropriate training and experience in ACP are encouraged to support the health-care teams in charge upon request. | 94 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| 33. Health-care providers should promote shared decision-making between the health-care providers and individuals as well as family and/or other closely related persons b during the ACP process. Ultimately, the shared discussions should always help to achieve the goal of respecting the patient’s preference. | 93 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 34. Health-care providers should respect the faith, belief system, and culture of each individual throughout the process of ACP. | 99 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Recommended timing of ACP | ||||

| 35. Individuals can engage in ACP at any stage of their life, but its content can be more targeted as their physical or cognitive health worsens or as they age. | 76 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 36. ACP conversations and documents should be updated periodically as an individual’s health condition, treatment plan, values, and preferences might change over time. | 96 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 37. Public awareness of ACP should be raised, especially about the aims and content of ACP, its legal status, and how to access it. | 96 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Recommended elements of policy and regulation | ||||

| 38. Health authorities should provide policy and ethicolegal guidance on ACP as a reference. | 84 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| 39. A system should be built to capture the contents of ACP conversation and the information should be made visible across the health-care continuum. | 87 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| 40. It is desirable that individuals be guided in their selection of a personal representative c to indicate treatment and care preferences when the individual loses capacity. | 78 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| 42. Advance directives d may also include any format that is acceptable within guidelines and/or laws of the sectors, in order for the individual to indicate his or her values, goals, and preferences in more detail. | 78 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 43. Health-care organizations should be aware of the importance of ACP and create opportunities for its initiation and review. | 91 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| 44. Health-care organizations should develop a collaborative system to support the individual’s decision-making by multidisciplinary health-care providers in any setting (e.g., hospital, care facility, and community). | 88 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 45. Reliable and secure systems should be created to store copies of official or medical ACP-related documents for ease of retrieval, transfer, and update. | 91 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 46. Governments should play a part in supporting efforts related to ACP development. | 91 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| 47. Health-care organizations should secure appropriate funding and organizational support for ACP including time, education, and training for health-care providers. | 94 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 48. Health professional bodies and policy makers should recognize that the results of an ACP process guide medical decision-making. | 84 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| 49. Health-care systems should have processes in place to ensure that an individual’s preferences in ACP are shared with all those concerned with the individual’s care, with permission of the individual. | 87 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Recommended evaluation of ACP | ||||

| 50. Depending on the study or project aims, we recommend the following constructs be assessed: | 0 | |||

| Process outcomes domain | ||||

| Behavior change constructs | ||||

| Knowledge of ACP (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 81 | 2 | 1 | |

| Self-efficacy to engage in ACP (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 85 | 2 | 1 | |

| Readiness to engage in ACP (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 91 | 2 | 1 | |

| Willingness to engage in ACP discussions (rated by the individual, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 88 | 2 | 1 | |

| Perception constructs | ||||

| Prognostic awareness (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons b ) | 88 | 2 | 1 | |

| Understanding of end-of-life care (rated by individuals and family and/or other closely related persons b ) | 94 | 2 | 1 | |

| Action outcomes domain | ||||

| Communication and documentation | ||||

| Personal representative constructs | ||||

| Identification of a personal representative c | 79 | 2 | 1 | |

| Values and preferences constructs | ||||

| Identification of the individual’s values, goals, and preferences | 94 | 1 | 1 | |

| Communication about values, goals, and preferences between the individual and family and/or other closely related persons b | 90 | 1 | 1 | |

| Communication about values, goals, and preferences between the individual and health-care providers | 91 | 1 | 1 | |

| Congruence between an individual’s stated wishes and personal representative’s reports of an individual’s wishes | 78 | 2 | 1 | |

| Documentation of values, goals, and preferences | 94 | 2 | 1 | |

| Documents and recorded wishes to be accessible when needed | 93 | 2 | 1 | |

| A flexible process that allows regular updates of ACP discussions and documents over time | 94 | 1 | 1 | |

| Quality of care outcomes domain | ||||

| Care consistent with goal constructs | ||||

| Whether care received was consistent with the individual’s expressed goals and preferences | 91 | 2 | 1 | |

| Satisfaction with care | ||||

| Quality of end-of-life care | 85 | 2 | 1 | |

| Satisfaction with decision-making | ||||

| Decisional conflict (e.g., within individuals, among individuals, families and/or other closely related persons, b and/or health-care providers) | 82 | 2 | 1 | |

| Satisfaction with communication | ||||

| Extent to which ACP was considered meaningful and helpful (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 90 | 2 | 1 | |

| Quality of ACP conversations (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and facilitators or health-care providers, or both) | 85 | 2 | 1 | |

| A clinician’s provision of prognostic information tailored to individual/family readiness | 88 | 2 | 1 | |

| Health-care outcomes domain | ||||

| Health status and mental health | ||||

| Psychological distress (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 85 | 2 | 1 | |

| Peace of mind (rated by individuals and family and/or other closely related persons b ) | 76 | 2 | 1 | |

| Preparation for end of life (rated by individuals and family and/or other closely related persons b ) | 91 | 2 | 1 | |

| Quality of life (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, b and health-care providers) | 76 | 2 | 1 | |

| Care utilization constructs | ||||

| Use of life-sustaining treatment | 81 | 2 | 1 | |

| Place of death | 75 | 2 | 2 | |

| Use of palliative care | 84 | 2 | 1 | |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| The level of public awareness of ACP | 79 | 2 | 1 | |

| 51. We recommend identifying or developing outcome measures based on these constructs and using relevant outcome measures on an as-needed basis so that results can be pooled and compared across studies or projects; these outcome measures should have sound psychometric properties, be sufficiently brief, and validated within relevant populations. | 85 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

ACP: advance care planning; IQR: inter-quartile range.

Agreement (%): Of the total participants in the Round 3 survey (n = 68), percentage of panelists who gave the Likert response options “strongly agree” or “agree”; answering categories: 1 = strongly agree; 2 = agree; 3 = agree somewhat; 4 = undecided; 5 = disagree somewhat; 6 = disagree; 7 = strongly disagree. Agreement (median): Of scores on the Likert scale that were given by panelists, indicating agreement. Inter-quartile range (IQR): Of scores on the Likert scale that were given by panelists, indicating consensus.

Decisional capacity: A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that he or she lacks capacity, and all practicable steps must be taken to empower the individual to maximize his or her decisional capacity in the ACP process.

Other closely related persons: “Other closely related persons” are those trusted by an individual, and may include, but are not limited to, significant others, close friends, donees of a lasting power of attorney, and court-appointed deputies, according to relevant laws or social conventions in each region.

Personal representative: A personal representative is appointed by the individual to speak for himself or herself once he or she lacks capacity to make decisions. Some regions have legislation for personal representatives, and others do not. In the former, relevant laws will be followed. In the latter, roles of personal representatives are often played by the individual’s family and/or other closely related persons nominated by the individual who regularly participate in ACP discussions.

Advance directive: An advance directive is a document that explains how the individual wants medical decisions about himself or herself to be made if he or she cannot make the decisions himself or herself. In regions where an advance directive and/or personal representative are not legalized, an “advance directive” indicates ACP-related documents to record values, goals, and preferences to be considered when the individual is unable to express their preferences.

Table 3.

Final set of recommendations on advance care planning with ratings, as provided by the panel in Delphi round 3 (agreement <75%).

| Agreement (%) | Agreement (median) | IQR | Comments that were written by the panel in rounds 2 and 3 (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended elements of ACP | ||||

| 10. Where local laws or conventions apply, ACP discussion includes an exploration of the degree of leeway the personal representative a has in making decisions on behalf of the individual if the individual loses decisional capacity. | 68 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Recommended policy and regulation | ||||

| 41. Advance directives need a structured format to enable easy identification of an individual’s specific goals and preferences for future care. | 60 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| Recommended evaluation | ||||

| Process outcomes domain | 0 | |||

| Perception constructs | ||||

| Anxiety over thinking about death (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons b , and health-care providers) | 68 | 2 | 1 | |

| Action outcomes domain | ||||

| Communication and documentation | ||||

| Personal representative constructs | ||||

| An individual’s decision on the amount of flexibility/leeway in decision-making to give a personal representative | 65 | 2 | 1 | |

| Quality of care outcomes domain | ||||

| Satisfaction with care | ||||

| Decision control preferences, that is, control over decision making (rated by individuals and family and/or other closely related persons) | 72 | 2 | 2 | |

| Satisfaction with communication | ||||

| Satisfaction with the ACP process (rated by individuals, family and/or other closely related persons, health-care providers, or both | 68 | 2 | 2 | |

| Health-care outcomes domain | ||||

| Health status and mental health | ||||

| Psychological well-being of the bereaved | 74 | 2 | 1 | |

ACP: advance care planning; IQR: inter-quartile range.

Personal representative: A personal representative is appointed by the individual to speak for himself or herself once he or she lacks capacity to make decisions. Some regions have legislation for personal representatives, and others do not. In the former, relevant laws will be followed. In the latter, roles of personal representatives are often played by the individual’s family and/or other closely related persons nominated by the individual who regularly participate in ACP discussions.

Other closely related persons: “Other closely related persons” are those trusted by an individual, and may include, but are not limited to, significant others, close friends, donees of a lasting power of attorney, and court-appointed deputies, according to relevant laws or social conventions in each region.

In round 5, the complete final set was reviewed and supported by the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network Council. Tables 2 and 3 present the final set, including agreement levels, median scores, and IQRs. The six domains include: 14 elements (four for a person-centered and family-based approach), 16 roles and tasks, three for timing, 12 on policy and regulations, and 34 on evaluation.

Discussion

Main findings

These are, to the best of our knowledge, the first consensus definition and recommendations for advance care planning in Asia developed through a rigorous Delphi study. The level of agreement and consensus suggests that our recommendations are suitable for various settings and patient populations in Asia.

What this study adds

The first important finding is that most recommendations, partly adopted from the European advance care planning consensus, received marked agreement and consensus with minor revisions. 1 This indicates that advance care planning in the five Asian sectors has been heavily influenced by the Western concept of patient autonomy. 37 Asian experts have adapted Western models to their contexts, leading to person-centric elements. For example, Korea and Taiwan enacted advance care planning legislation supporting patient autonomy in the late 2010s, with similar policies put forward in Hong Kong, Japan, and Singapore. 27 Western training programs have also been introduced.27,38 –40 While Western models emphasize individualized autonomy,1,11 Asian cultures traditionally value relational autonomy, where decisions are made within family and community contexts.12,15,17,23,27,29,35,41 The convergence highlights the growing acceptance of individualized autonomy in Asian advance care planning, despite cultural differences. 42 However, recommendations regarding documentation, advance directives, and surrogate decision-making (e.g., items 10, 13, and 40–42) received lower-level agreement, possibly due to varying regulations and implementation across sectors. 27 Therefore, our Delphi recommendations should be adapted to complement local legislation, health-care systems, and practice patterns.

The second important finding is that all items of the new domain relevant to Asian culture, “recommended consideration for a person-centered and family-based approach in advance care planning,” received very strong agreement and consensus. Traditionally, Asian patients prioritize family harmony over individual autonomy, often deferring decision-making to families and health-care providers. 12 Harmony is maintained through relational autonomy.30,35,43 However, public values in Asia are shifting towards more active and shared decision-making, partly influenced by the globalization of liberal values.17,21,23,44 –47 Clinicians in Asia also recommend not making assumptions based on cultural backgrounds.29,48 –50 Our recommendation emphasizes valuing individual preferences while ensuring family involvement in advance care planning (e.g., items 22 and 33). 51

Most proposed measures to evaluate advance care planning did not receive very strong agreement, reflecting current controversies over advance care planning outcomes. 7 However, many measures proposed in Western Delphi studies received high-level agreement and consensus in our study.1,10 Six of the top 10 measures proposed from a Western study received over 90% agreement from our panelists. 10 These included readiness to engage in advance care planning, and the identification, communication, and documentation of the individual’s values, goals, and preferences, as well as care consistent with the individual’s expressed goals and preferences. This underscores the importance of communication in advance care planning in Asia.27 –29 Measures with lower-level agreement, such as anxiety about death, decision control preferences, and psychological well-being of the bereaved, were also ranked low in the previous Western study. 10 These measures may be abstract or not universally recognized, suggesting that they should be used with caution. In contrast, newly added measures such as understanding end-of-life care and preparation for end-of-life received marked agreement, highlighting the iterative process of advance care planning.

Overall, our study underscores the fact that the core principles of advance care planning, such as prioritizing individual values and preferences, have universal applicability. The European consensus on advance care planning can be adapted across cultural contexts, indicating its broad relevance. However, cultural nuances, such as the family-based approach prevalent in Asia and many other societies, require tailored adaptations to ensure local relevance. This adaptability is crucial for the effective global implementation of advance care planning programs. Our findings provide a foundation for culturally-sensitive advance care planning interventions, ensuring appropriate outcomes worldwide.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. First, we applied rigorous methodology by following the reporting guidance, 24 and collaborated with field and methodology experts.1,17,23 Second, contextual evidence was used to inform the study procedure.1,10,11,17,23,27 –29 Third, the support of the Asia-Pacific regional network allowed the engagement of 77 multidisciplinary experts from various backgrounds. Fourth, we adopted a measure to avoid discrepancies by asking only panelists who responded to the round two survey to actually complete the round three survey. Finally, we enhanced study robustness by applying conservative cut-off levels for agreement and a mixed-method approach.

Our study had some limitations. First, as we conducted this study in only five Asian sectors where palliative care is highly integrated into health-care systems, 52 our findings may not be applicable to other regions. However, these findings may contribute to other regions with family-centered decision-making cultures, such as Muslim or Hindu communities. Second, subtle differences in meaning from the English version may have been present in each of the translated versions among the five sectors. Third, the respondents were predominantly physicians, and so perspectives were limited.

Future implications

We recommend implementing the definition and recommendations for practice, education, research, and policy-making for those living in Asia and Asians in Western countries. Such endeavors should consider various barriers and facilitators affecting attitudes toward advance care planning, including health literacy, generational differences, and acculturation to Western culture.47,53 –57 Future efforts should develop culturally attuned approaches and quality indicators for advance care planning outcomes, and formulate systematic plans for implementation and dissemination to improve local health-care systems and legal jurisdictions. Lastly, attention should be given to pediatric populations, patients with limited or no decisional capacity, and populations in low/middle-income regions in Asia. We suggest that future studies should explore whether our findings are applicable to other parts of Asia outside the five sectors and non-Asian regions with similar cultures.

Conclusion

Our Delphi study developed consensus on the definition of advance care planning and recommendations for its application in an Asian context, both within Asia and for Asians living in Western countries. The study represents an important first step in providing clarity and guidance for further practice, education, research, and policy-making concerning advance care planning in Asia. We hope that our findings will help to develop culturally sensitive advance care planning interventions, identify appropriate outcomes, and build an infrastructure where Asian individuals can receive care concordant with their values, goals, and preferences.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241284088 for Definition and recommendations of advance care planning: A Delphi study in five Asian sectors by Masanori Mori, Helen Y. L. Chan, Cheng-Pei Lin, Sun-Hyun Kim, Raymond Ng Han Lip, Diah Martina, Kwok Keung Yuen, Shao-Yi Cheng, Sayaka Takenouchi, Sang-Yeon Suh, Sumytra Menon, Jungyoung Kim, Ping-Jen Chen, Futoshi Iwata, Shimon Tashiro, Oi Ling Annie Kwok, Jen-Kuei Peng, Hsien-Liang Huang, Tatsuya Morita, Ida J. Korfage, Judith A. C. Rietjens and Yoshiyuki Kizawa in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

We thank all panel experts who participated in the Delphi study for their valuable input; Prof. Pang Weng Sun, Dr. Hsueh-Lin Ho, and Dr. Grace Pang for their cooperation during Round 1 of the Delphi study; and the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network council and research committee members for their generous support. We also appreciate Ms. Trudy Giam and Ms. Joyce Chee from the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network and Ms. Jennifer Andrea for their secretariat support.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition of subjects and/or data: Masanori Mori, Helen Y.L. Chan, Cheng-Pei Lin, Sun-Hyun Kim, Raymond Ng Han Lip, Kwok Keung Yuen, Shao-Yi Cheng, Sayaka Takenouchi, Sang-Yeon Suh, Sumytra Menon, Jungyoung Kim, Ping-Jen Chen, Futoshi Iwata, Shimon Tashiro, Oi Ling Annie Kwok, Jen-Kuei Peng, Hsien-Liang Huang, Tatsuya Morita, and Yoshiyuki Kizawa. Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors. Masanori Mori and Yoshiyuki Kizawa have directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. Preparation of manuscript: All authors. All authors sufficiently contributed to this manuscript in accordance with the “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.” All authors have confirmed full access to all the data in the study and have given their permission for publication.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Hospice Palliative Care Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI (JP18H02736, 20K20618). The funding source had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Research ethics and participant consent: Ethical and scientific validities were confirmed by the institutional review board of the principal investigator’s institution, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital, Japan (No. 18-39), on October 15, 2018, and by institutional review boards in all other sectors. We conducted the Delphi process using an online survey system supported by the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The survey among Delphi panel panelists was completely anonymous and participation was voluntary. Participants indicated their informed consent by checking the box prior to the survey.

| Will individual participant data be available (including data dictionaries)? | Yes |

| What data in particular will be shared? | Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after de-identification (text, tables, figures, and appendices) |

| What other documents will be available? | Study protocol |

| When will data be available (start and end dates)? | Beginning 3 months and ending 5 years following article publication |

| With whom? | Investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose |

| For what types of analyses? | To achieve aims in the approved proposal |

| By what mechanisms will data be made available? | Proposals should be directed to masanori.mori@sis.seirei.or.jp; to gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement. |

ORCID iDs: Masanori Mori  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5489-9395

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5489-9395

Helen Y. L. Chan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4038-4654

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4038-4654

Cheng-Pei Lin  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5810-8776

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5810-8776

Shao-Yi Cheng  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2224-4140

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2224-4140

Sumytra Menon  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9129-4072

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9129-4072

Ping-Jen Chen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7636-0801

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7636-0801

Hsien-Liang Huang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2163-5596

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2163-5596

Ida J. Korfage  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6538-9115

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6538-9115

Judith A. C. Rietjens  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, et al. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klingler C, In Der Schmitten J, Marckmann G. Does facilitated Advance Care Planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morrison RS. Senior associate editor’s response to readers’ comments to Morrison: advance directives/care planning: clear, simple, and wrong. J Palliat Med 2021; 24: 14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What’s wrong with advance care planning? JAMA 2021; 326: 1575–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Periyakoil VS, Gunten CFV, Arnold R, et al. Caught in a loop with advance care planning and advance directives: how to move forward? J Palliat Med 2022; 25: 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, et al. Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: summary of evidence and global lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 56: 436–459 e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL. Deconstructing the complexities of advance care planning outcomes: what do we know and where do we go? A scoping review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021; 69: 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, et al. Outcomes that define successful advance care planning: a Delphi panel consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55(2): 245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 821–832 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mori M, Morita T. End-of-life decision-making in Asia: a need for in-depth cultural consideration. Palliat Med 2020; 34(2): NP4–NP5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy S, et al. Bioethics in a different tongue: the case of truth-telling. J Urban Health 2001; 78: 59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ. Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: “you got to go where he lives”. JAMA 2001; 286: 2993–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miyashita J, Shimizu S, Shiraishi R, et al. Culturally adapted consensus definition and action guideline: Japan’s advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022; 64: 602–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mori M, Lin CP, Cheng SY, et al. Communication in cancer care in Asia: a narrative review. JCO Glob Oncol 2023; 9: e2200266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martina D, Lin CP, Kristanti MS, et al. Advance care planning in Asia: a systematic narrative review of healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude, and experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021; 22: 349 e1–349 e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miyashita J, Kohno A, Shimizu S, et al. Healthcare providers’ perceptions on the timing of initial advance care planning discussions in Japan: a mixed-methods study. J Gen Intern Med 2021; 36: 2935–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamano J, Oishi A, Morita T, et al. Frequency of discussing and documenting advance care planning in primary care: secondary analysis of a multicenter cross-sectional observational study. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng SY, Suh SY, Morita T, et al. A cross-cultural study on behaviors when death is approaching in East Asian countries: what are the physician-perceived common beliefs and practices? Medicine 2015; 94: e1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mori M, Kuwama Y, Ashikaga T, et al. Acculturation and perceptions of a good death among Japanese Americans and Japanese living in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 55: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morita T, Oyama Y, Cheng SY, et al. Palliative care physicians’ attitudes toward patient autonomy and a good death in East Asian countries. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 50: 190–199 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martina D, Geerse OP, Lin CP, et al. Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning: a mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework. Palliat Med 2021; 35(10): 1776–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Junger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. Guidance on conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017; 31: 684–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Vet E, Brug J, De Nooijer J, Dijkstra A, et al. Determinants of forward stage transitions: a Delphi study. Health Educ Res 2005; 20: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Biondo PD, Nekolaichuk CL, Stiles C, et al. Applying the Delphi process to palliative care tool development: lessons learned. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16: 935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng SY, Lin CP, Chan HY, et al. Advance care planning in Asian culture. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2020; 50: 976–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chikada A, Takenouchi S, Nin K, et al. Definition and recommended cultural considerations for advance care planning in Japan: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2021; 8: 628–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin CP, Cheng SY, Mori M, et al. 2019 Taipei declaration on advance care planning: a cultural adaptation of end-of-life care discussion. J Palliat Med 2019; 22: 1175–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dove ES, Kelly SE, Lucivero F, et al. Beyond individualism: is there a place for relational autonomy in clinical practice and research? Clin Ethics 2017; 12: 150–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ells C, Hunt MR, Chambers-Evans J. Relational autonomy as an essential component of patient-centered care. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth 2011; 4: 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, et al. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25: 741–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ho A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand J Caring Sci 2008; 22: 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Killackey T, Peter E, Maciver J, et al. Advance care planning with chronically ill patients: a relational autonomy approach. Nurs Ethics 2019; 27(2): 360–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin CP, Cheng SY, Chen PJ. Advance care planning for older people with cancer and its implications in Asia: highlighting the mental capacity and relational autonomy. Geriatrics 2018; 3: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Will JF. A brief historical and theoretical perspective on patient autonomy and medical decision making: Part II: the autonomy model. Chest 2011; 139: 1491–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu CC, Koh EJ, Low JA, et al. A multi-site study on the impact of an advance care planning workshop on attitudes, beliefs and behavioural intentions over a 6-month period. BMC Med Educ 2021; 21: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ito K, Uemura T, Yuasa M, et al. The feasibility of virtual VitalTalk workshops in Japanese: can faculty members in the US effectively teach communication skills virtually to learners in Japan? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2022; 39(7): 785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Onishi E, Nakagawa S, Uemura T, et al. Physicians’ perceptions and suggestions for the adaptation of a US-based serious illness communication training in a non-US culture: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021; 62: 400–409 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Foo KF, Lin YP, Lin CP, et al. Fostering relational autonomy in end-of-life care: a procedural approach and three-dimensional decision-making model. J Med Ethics. Epub ahead of print 25 March 2024. DOI: 10.1136/jme-2023-109818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gomez-Virseda C, de Maeseneer Y, Gastmans C. Relational autonomy: what does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jia Z, Leiter RE, Yeh IM, et al. Toward culturally tailored advance care planning for the Chinese diaspora: an integrative systematic review. J Palliat Med 2020; 23: 1662–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Matsushima E, et al. Preferences of advanced cancer patients for communication on anticancer treatment cessation and the transition to palliative care. Cancer 2015; 121: 4240–4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yennurajalingam S, Rodrigues LF, Shamieh OM, et al. Decisional control preferences among patients with advanced cancer: an international multicenter cross-sectional survey. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miyashita J, Kohno A, Cheng SY, et al. Patients’ preferences and factors influencing initial advance care planning discussions’ timing: a cross-cultural mixed-methods study. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Matsumura S, Bito S, Liu H, et al. Acculturation of attitudes toward end-of-life care: a cross-cultural survey of Japanese Americans and Japanese. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17: 531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2007; 21: 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin CP, Evans CJ, Koffman J, et al. What influences patients’ decisions regarding palliative care in advance care planning discussions? Perspectives from a qualitative study conducted with advanced cancer patients, families and healthcare professionals. Palliat Med 2019; 33(10): 1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tse CY, Chong A, Fok SY. Breaking bad news: a Chinese perspective. Palliat Med 2003; 17: 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kishino M, Ellis-Smith C, Afolabi O, et al. Family involvement in advance care planning for people living with advanced cancer: a systematic mixed-methods review. Palliat Med 2022; 36: 462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clark D, Baur N, Clelland D, et al. Mapping levels of palliative care development in 198 countries: the situation in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 59: 794–807 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hong M, Yi EH, Johnson KJ, et al. Facilitators and barriers for advance care planning among ethnic and racial minorities in the U.S.: a systematic review of the current literature. J Immigr Minor Health 2018; 20: 1277–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chiang FM, Wang YW, Hsieh JG. How acculturation influences attitudes about advance care planning and end-of-life care among Chinese living in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Australia. Healthcare 2021; 9: 1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gao X, Sun F, Ko E, et al. Knowledge of advance directive and perceptions of end-of-life care in Chinese-American elders: the role of acculturation. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13: 1677–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. West SK, Hollis M. Barriers to completion of advance care directives among African Americans ages 25–84: a cross-generational study. Omega 2012; 65: 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. de Vries K, Banister E, Dening KH, et al. Advance care planning for older people: the influence of ethnicity, religiosity, spirituality and health literacy. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 1946–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241284088 for Definition and recommendations of advance care planning: A Delphi study in five Asian sectors by Masanori Mori, Helen Y. L. Chan, Cheng-Pei Lin, Sun-Hyun Kim, Raymond Ng Han Lip, Diah Martina, Kwok Keung Yuen, Shao-Yi Cheng, Sayaka Takenouchi, Sang-Yeon Suh, Sumytra Menon, Jungyoung Kim, Ping-Jen Chen, Futoshi Iwata, Shimon Tashiro, Oi Ling Annie Kwok, Jen-Kuei Peng, Hsien-Liang Huang, Tatsuya Morita, Ida J. Korfage, Judith A. C. Rietjens and Yoshiyuki Kizawa in Palliative Medicine