Abstract

Background:

Outcome measurement is essential to progress clinical practice and improve patient care.

Aim:

To develop a Core Outcome Set for best care for the dying person.

Design:

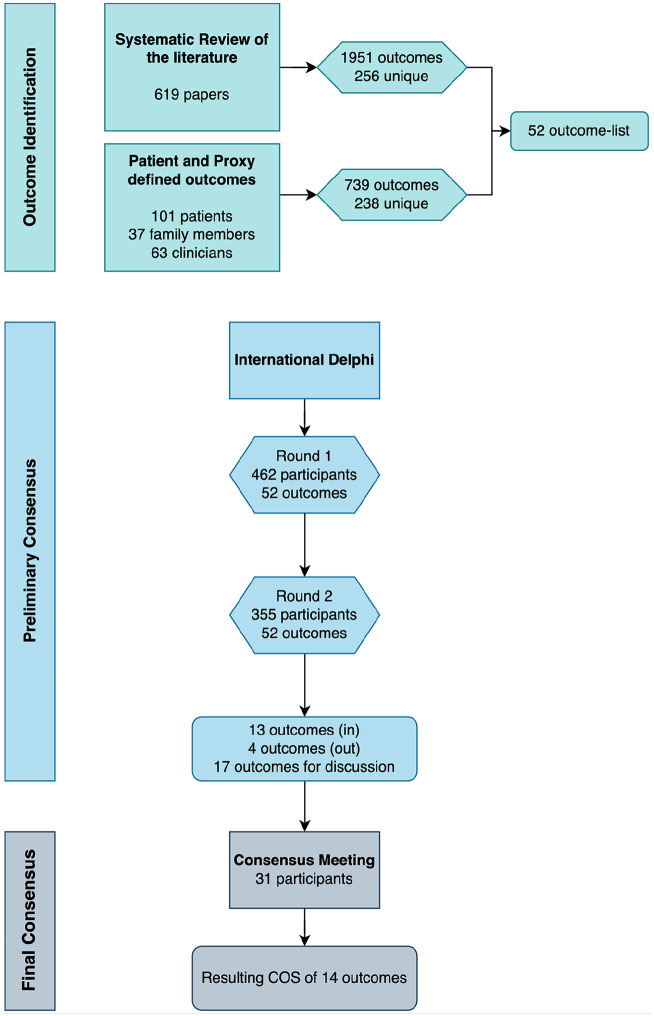

We followed the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative guidelines, which involved identifying potential outcomes via a systematic literature review (n = 619 papers) and from participants in the “iLIVE” project (10 countries: 101 patients, 37 family members, 63 clinicians), followed by a two-round Delphi study, and a consensus meeting.

Setting/participants:

Clinicians, researchers, family members, and patient representatives from 20 countries participated in the Delphi Rounds 1 (n = 462) and 2 (n = 355). Thirty-two participants attended the consensus meeting.

Results:

From the systematic review and the cohort study we identified 256 and 238 outcomes respectively, from which we extracted a 52-outcome list covering areas related to the patients’ physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions, family support, place of care and care delivery, relational aspects of care, and general concepts. A preliminary 13-outcome list reached consensus during the Delphi. At the consensus meeting, a 14-item Core Outcome Set was ratified by the participants.

Conclusions:

This study involved a large and diverse sample of key stakeholders in defining the core outcome set for best care for the dying person, focusing on the last days of life. By actively integrating the perspectives of family carers and patient representatives from various cultural backgrounds this Core Outcome Set enriches our understanding of essential elements of care for the dying and provides a solid foundation for advancing quality of end-of-life care.

Keywords: terminal care, palliative care, quality of care, core outcome set, Delphi method

What is already known about the topic?

Outcome measurement is essential in palliative care to assess the effectiveness of clinical care and demonstrate its value.

Outcomes relevant to the last days of life remain understudied.

Patient and family caregiver perspectives have been underrepresented in defining care outcomes for the last days of life.

What this paper adds?

A 14-item core outcome set was developed from the perspective of key stakeholders focused on key aspects for best care for the dying person.

The core outcomes are connected to key dimensions of palliative care, which include physical, psychological, and social aspects, the place of care and care delivery, relational aspects of care, and general concepts.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Adopting the core outcome set can enhance care in the last days of life by standardizing clinical care aspects, improving patient and family experiences.

The core outcome set offers a basis for advancing research about the last days of life, encouraging outcome standardization.

Utilizing the core outcome set in policy can further support the development of quality benchmarks, influencing guidelines and resource allocation for palliative care services.

Introduction

Since the inception of palliative care as a specialized medical field, researchers and clinicians have strived to develop and use measures to continuously assess and improve patient outcomes. Assessing outcomes is important in improving patient care and care for family caregivers, as well as in demonstrating the tangible benefits and cost-effectiveness of palliative care interventions; goals important in providing evidence to prioritize funding and support for this critical aspect of healthcare.

Numerous studies have been undertaken and tools have been developed to facilitate outcome measurement in palliative care (e.g. the Palliative Care Outcome scale 1 ), including international projects and national initiatives to harmonize palliative care measurements (e.g. the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration in Australia, 2 the EAPC Taskforce on Outcome Measurement, 3 and PRISMA 4 which was funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program).

Given the diverse range of available measurement tools and instruments, understanding what and when to measure becomes paramount, especially considering that palliative care encompasses a wide spectrum of care: from the diagnosis of life-limiting illnesses to care of the dying and the bereaved. 5 When defining “what” to measure, most studies within palliative care have done so based on expert consensus, 6 with a minority taking into account the mix of relevant stakeholders, 7 thus potentially giving more weight to medical aspects of care. 8 In addition, studies focused on what matters to patients and family carers have assessed needs at earlier illness stages, leaving outcomes relevant to the last days of life understudied. 9

In this study, we aimed to develop a Core Outcome Set for best care for the dying patient, focusing on the last days of life, to be used in research and to guide patient care. For the development of this core outcome set, we followed the steps recommended by the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative, 10 as previously described in our study protocol. 11 Our approach began with a systematic review of the literature to identify outcomes relevant to the last days of life 12 and with an international cohort study 13 via which we identified key outcomes from the perspectives of patients and family members. After consolidating a shorter list of potential outcomes derived from these sources, we sought consensus on core outcomes among key stakeholders through a Delphi study and a consensus meeting. In this paper, we present the results from the international Delphi study and the consensus meeting and publish the final core outcome set.

Method

The Delphi study and consensus meeting were prospectively reviewed by the Bernese Cantonal Ethical Commission, which provided a declaration of no objection, meaning that the study was exempted from further ethical review and could be performed by the researchers (req-2019-00200). The manuscript has been written using the COS-STAR recommendations for the reporting of core outcome set development studies. 14

Participants

We invited participants from four stakeholder groups relevant to end-of-life care, namely: clinicians, researchers, family members, and patient representatives.

From 10 out of 11 countries participating in the “iLIVE” project, 13 Argentina, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, New Zealand, and the UK, we received a list of at least 10 potential participants per stakeholder group and invited them to participate in the Delphi study. All participants were contacted by email. To facilitate participation of individuals with a non-academic background, we provided definitions, explanations, and clear instructions through written means, based on those employed by the EPSET Core Outcome Set development team. 15 We also gave participants details of a contact person in case unanticipated issues arose both during the Delphi and the consensus meeting, for both technical and emotional support if/as needed.

Outcome list development process

In this study, we adopted a broad definition of “outcome” taking into consideration the specific features and domains of palliative care, as well as the outcome classification taxonomy developed by Dodd et al. 16 Outcomes were defined as the effect or result of a given treatment/intervention on the patient or the family, encompassing not only clinical changes but also the emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions that are essential to palliative care. Additionally, because the core outcome set was designed to be applicable to both research and clinical care, and the outcomes were derived from clinical research and from the perspectives of patients and family members, they also reflect processes of care that are critical to delivering high-quality palliative care to both patients and families.

To develop the list of outcomes for the Delphi study, we merged and condensed the list of outcomes initially identified in the systematic review, 12 and from the “iLIVE” project’s cohort study, in the following fashion:

From the systematic review we extracted 1951 outcomes, of which 256 were unique, that is, similar outcomes described using different wording were only included once. The process of outcome extraction and selection is described in the systematic review publication. 12

In parallel, from the cohort study, we identified outcomes for 108 patients who were in the last month of life. Patients were on average 70 years old (range 42–94), 52% were men, and over 90% had cancer. For those 108 patients, we included the responses of 101 patients, 37 relatives, and of 63 clinicians, which made up a total of 201 responses. Most responses covered more than one outcome, and therefore from the 201 responses, we identified 739 outcomes, of which 238 were unique. The most common outcome was “having constant companionship from family and friends” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome list and frequency for the top 20 outcomes from the cohort study.

| Outcome name | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Constant companionship to patient by family and friends | 53 |

| Pain management | 52 |

| Pain free | 32 |

| Symptom control | 31 |

| Communication with health personnel | 27 |

| Comfort | 26 |

| No suffering | 25 |

| Personal hygiene | 24 |

| Psychosocial and emotional support | 23 |

| Medical care with humanism | 23 |

| Sedation | 20 |

| Professional support | 19 |

| Palliative care | 14 |

| To stay at home | 12 |

| To be treated with dignity and respect | 12 |

| Care focused on patient wishes | 10 |

| Quality of life | 8 |

| To feel cared for | 7 |

| Support for relatives | 7 |

| Peace | 7 |

Of the 256 outcomes identified in the systematic review, 112 overlapped with the 238 from the cohort study, leaving a total of 382 unique outcomes. As core outcome set development Delphi studies with long outcome lists have low response rates, 17 a palliative care specialist (SE), a psychologist (SCZ), and an epidemiologist (VGJ) further reduced the list, with support from a core outcome set development expert (PRW).

Outcomes were first grouped in categories of a higher order; for example, we combined “Respiratory tract secretions management” with “Dyspnea management” and with “Noisy breathing management” and created a new category that included all three, called “Management of respiratory symptoms.” We put outcomes together and created categories as long as they were logical and respected the uniqueness of the outcomes. To ensure that the different outcomes were clear for the Delphi participants, we operationalized all outcome descriptions to clearly indicate what each outcome encompassed (Appendix 1). With outcomes not covered by developed categories, we could make two choices: create a new category or exclude them. For this, we considered the outcome relevance for the last days of life; for example, we excluded the outcome “to prolong life” because it is not aligned with good care for the dying. Additionally, we based the decision on the frequency with which the outcome had been reported; for example, we excluded “Falls” and “Ambulance use” because, in addition to not fitting into any of the developed categories, they were reported infrequently, sometimes only in either the cohort or the systematic review.

Following this process, we generated a final list of 52 clustered outcomes, which included grouped outcomes as well as global measures such as “quality of death and dying.” These global measures were included when they represented general overarching outcomes, rather than composites, as suggested by the taxonomy for core outcome set development studies. 16 Of these, 37 were derived from the systematic review and the cohort study, 6 from the systematic review only, and 9 from the cohort study only.

Delphi rounds

The Delphi study consisted of two rounds of iterative surveys aimed at reaching consensus on the outcomes to be included in the core outcome set. Participants rated the importance of each outcome using a pre-defined scale from the GRADE group 18 : the lowest scores (1, 2, and 3) were considered as “not that important,” 4–6 were considered as “important but not critical,” and 7–9 were considered as “important and critical.” Additionally, in the first round, participants could provide feedback on each outcome and suggest new outcomes, with the intention of including outcomes not identified in the review or the cohort study. Each new outcome was reviewed and included only if it was: a) not already covered by other outcomes or their explanations, b) focused on the patient or the family, and c) suggested by at least two participants.

To determine which outcomes were perceived as “core,” we defined a priori the following thresholds: for consensus to include, we would include any item for which at least 80% of participants in all four participant groups had rated the outcome as “important and critical” (rating 7–9). Consensus to exclude an item, on the other hand, was achieved when 50% or less of the participants in all stakeholder groups rated the outcome as “important and critical” (rating 7–9). These thresholds were adapted from those proposed in the protocol, 11 as the original thresholds had been the reference cut-offs recommended at the time by COMET, however later developments with scoring of core outcome set Delphi studies led to the modified version that is currently more often employed (e.g. 19 ). Outcomes that did not meet these criteria were retained for discussion during the consensus meeting.

Participant information about the Delphi was provided in English, Spanish, German, Icelandic, Slovenian, Norwegian, Dutch, and Swedish using translations made by each national team. The Delphi survey itself was available in English, Spanish, Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic, Swedish, and German. We employed the DelphiManager system from COMET to build, distribute, and manage the Delphi surveys.

Round 2 included all initial outcomes as well as all new outcomes proposed by the participants. In addition, during Round 2, participants were shown a histogram displaying the Round 1 distribution of scores given by participants from each stakeholder group, along with their own previous score, and were asked to re-score each item if they wished to do so. After two rounds, the Delphi study was terminated.

Consensus meeting

Following the Delphi study, a consensus meeting was held to further refine and finalize the core outcomes. At first, participants were shown the items for which there was consensus to include, for ratification. This was followed by asking participants to ratify the outcomes that had consensus to be excluded. Next, participants were asked to vote for the outcomes for which no consensus was achieved in the Delphi (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study overview.

The voting was structured as follows: First, participants would see the results from all stakeholder groups for a group of outcomes and be given ample time to discuss each of the outcomes within the group. After discussion, participants were asked to vote for each of the outcomes using the same GRADE scores (1–9) in a specific order: family members and patient representatives first, followed by clinicians and researchers. This process was followed for each of the outcome groups that were brought for voting: a group of outcomes which reached consensus for inclusion in three of the four groups, followed by a group of outcomes that reached consensus for inclusion in two of the four groups, and a group of outcomes that reached consensus for inclusion in only one of the groups. The consensus meeting was led by PRW, an experienced facilitator of core outcome set development. ME, SE, and SCZ attended the meeting, but as core members of the core outcome set development team, none of them voted in the meeting.

Data analysis

We analyzed all responses from participants who had assigned a score to at least 50% of the outcomes. We employed descriptive statistics to display the scores from the two Delphi rounds, and to determine which outcomes would be brought to the consensus meeting for discussion. The analyses were carried out separately for each stakeholder group during the Delphi and presented in the same way at the consensus meeting.

Results

Delphi study

A total of 462 individuals participated in the first round, of these, 433 were eligible to be invited to the second round, as the Delphi Manager system was set to automatically invite only those with 100% complete responses to the second round. For Round 1, we analyzed the full dataset of 462 participants, as they had provided answers to at least 50% of the items. Of the 433 invited to the second round, 355 participated (82%).

In both rounds, clinicians were the largest participant group and there was a majority of women. Participants came from 20 different countries, with Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain being the most represented. Participants were on average 50 years old in both rounds (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

| Round 1 n=462 n (%) | Round 2 n=355 n (%) | Consensus meeting n = 32 n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant type | Clinician | 220 (48) | 157 (44) | 23 (72) |

| Researcher | 91 (20) | 81 (23) | ||

| Family member | 85 (18) | 71 (20) | 9 (28) | |

| Patient representative | 66 (14) | 46 (13) | ||

| Gender i | Female | 376 (81) | 285 (80) | 23 (72) |

| Male | 83 (18) | 69 (19) | 9 (28) | |

| Country i | Sweden | 93 (20) | 59 (17) | 5 (16) |

| Switzerland | 56 (12) | 48 (14) | 4 (13) | |

| Spain | 53 (11) | 45 (13) | 4 (13) | |

| Argentina | 46 (10) | 34 (10) | 4 (13) | |

| Netherlands | 32 (7) | 27 (8) | 2 (6) | |

| Norway | 31 (7) | 26 (7) | 4 (13) | |

| Iceland | 33 (7) | 24 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| Germany | 26 (6) | 21 (6) | 3 (9) | |

| Slovenia | 23 (5) | 20 (6) | 2 (6) | |

| New Zealand | 24 (5) | 18 (5) | ||

| United Kingdom (UK) | 15 (3) | 13 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| Austria | 13 (3) | 11 (3) | ||

| Australia | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (3) | |

| Portugal | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Belgium | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Denmark | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| France | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Hungary | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Italy | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Pakistan | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Age | Mean 51 (min 22, max 87) |

Mean 51 (min 22, max 87) |

Mean 54 (min 23, max 87) |

The total counts for gender and country do not add up to the overall N due to missing data from some participants.

Of the 157 clinicians who participated in Round 2, there was an even number of physicians (n = 64, 45%) and nurses (n = 64, 45%) followed by allied health practitioners (n = 18, 12%). Clinicians had on average 15 years of experience in end-of-life or palliative care (min 1, max 42). The researchers had on average 12 years of experience (min < 1, max 40) and 58% had been involved in clinical trial research. Most bereaved family members were grieving patients with cancer (n = 46, 68%). Their dying relatives had been cared for in diverse settings of care of which the majority died in a hospital (n = 24, 35%), at home (n = 15, 22%), or in a hospice or palliative care unit (n = 15, 22%). Most patient representatives were palliative care volunteers (n = 26, 62%) who had been supporting patients in average 7.4 years (min < 1, max, 30).

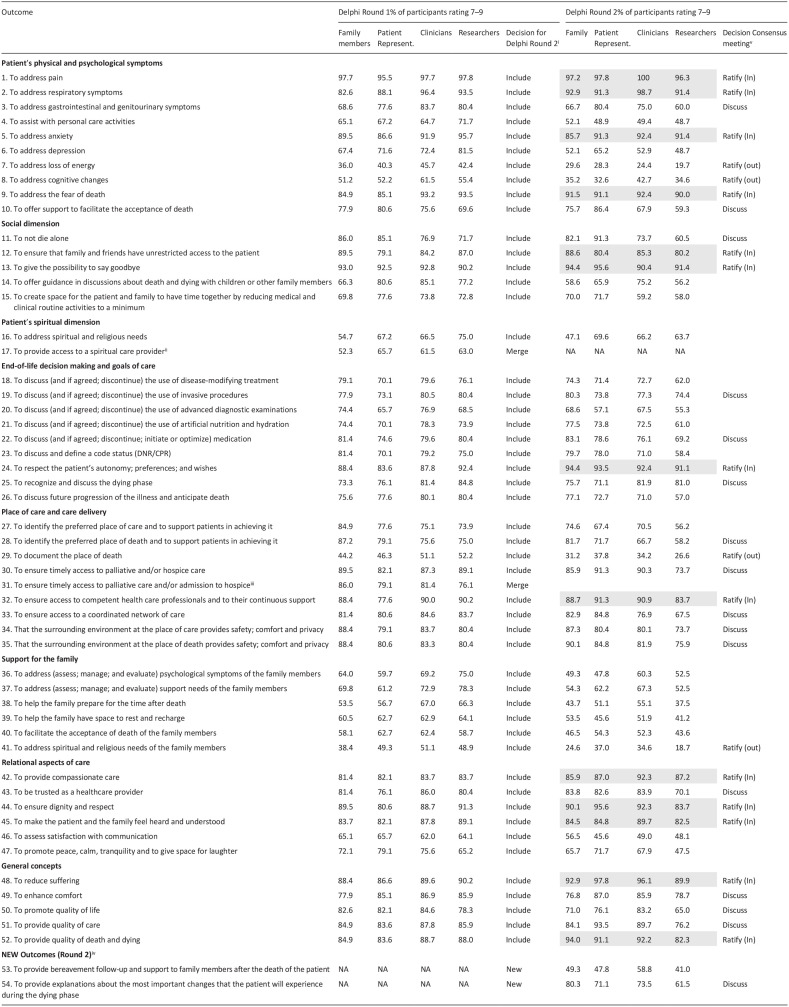

Round 1 took place between September and October 2022. In Round 1, 16 of the 52 outcomes met criteria for inclusion in the core outcome set, and one met exclusion criteria. As it had been established a priori that all outcomes would be shown again in Round 2, no exclusions or inclusions were made at this stage (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of Delphi scores in Rounds 1 and 2.

|

Outcomes from Round 1 were automatically included in Round 2, except for decisions to merge some of them based on feedback.

Outcome was merged with previous one.

Outcome was merged with previous one.

For round 2, from all suggested “new outcomes,” 2 outcomes were included.

For the consensus meeting, all outcomes with more than 80% importance in the 4 groups were included for ratification (these items appear highlighted in gray) and all those scoring 80% in at least one group were left for discussion. All items with less than 50% in the four groups were also left for ratification of exclusion.

In this same round, participants suggested the inclusion of 80 “new outcomes Only two of the proposed new outcomes met criteria for inclusion: “to provide bereavement follow-up and support to family members after the death of the patient” and “to provide explanations about the most important changes that the patient will experience during the dying phase” and were therefore added. An extension to outcome 3 was also made by adding “genitourinary symptoms” to gastrointestinal symptoms.

Of the feedback per outcome, 496 comments were received, with an average of 10 comments per outcome. Feedback was mostly related to personal experience, or the importance of the given outcome in patient care. Where the feedback was about the description or about the outcome itself, we made minor changes where needed. The biggest change was merging Outcome 17 with Outcome 16 and Outcome 31 with Outcome 30, as participants highlighted that they were not distinct from each other. In addition, in all family related outcomes, the word “caregiver” was replaced by “family.” The specific changes made to the outcomes between Round 1 and 2, as well as all outcome descriptions can be found in Appendix 1.

In Round 2, which was open between December 2022–January 2023, of the final 52 outcomes presented to participants, 13 met criteria for inclusion and four for exclusion (refer to Table 3).

Consensus meeting

The online consensus meeting took place on February 28th, 2023 with the attendance of 32 participants: 9 family members or patient representatives, and 23 clinicians or researchers.

In the meeting, participants were first asked to ratify the 13 outcomes that had met criteria for inclusion in the Delphi. Participants were given ample time for discussions before voting and after a discussion round, participants’ votes were unanimous in favor of the 13 outcomes. Then they were shown the four fulfilling criteria for exclusion, which after discussions were ratified as “consensus out” unanimously.

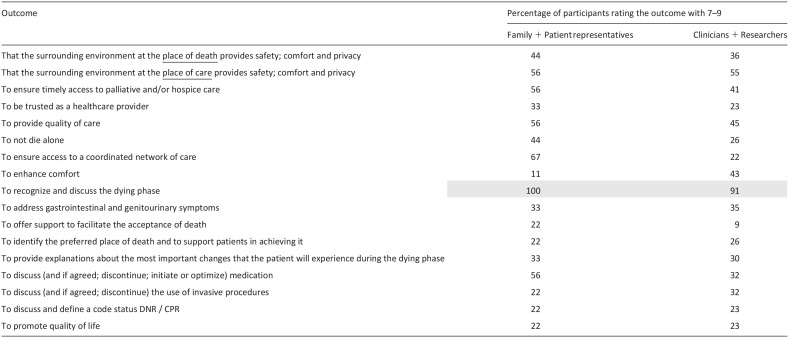

After this, participants were shown all outcomes for which there had been “no consensus” (Table 4). Due to time constraints, all other outcomes which had been voted with 79.9% or less by all groups, were not discussed.

Table 4.

Voting rounds for outcomes for which there had been no consensus in the Delphi rounds.

|

Following the voting rounds, the only outcome added to the ratified list of 13 outcomes was “to recognize and discuss the dying phase.” During discussions at the meeting, this outcome was viewed with high importance and not covered by any of the other outcomes. Thus, as endorsed by consensus meeting participants, the final core outcome set contains 14 outcomes in total (Table 5), covering areas related to the patients’ physical and psychological symptoms, their social dimension, the place of care and care delivery, relational aspects of care, and more general concepts of care, such as “quality of death and dying.” No outcomes were considered as core from the “Support for the family” category, including those specific to the bereavement phase, nor for the “patients’ spiritual dimension.”

Table 5.

Final core outcome set for best care for the dying person.

| To address pain |

| To address anxiety |

| To address respiratory symptoms |

| To ensure that family and friends have unrestricted access to the patient |

| To address the fear of death |

| To give the possibility to say goodbye |

| To recognize and discuss the dying phase |

| To reduce suffering |

| To ensure dignity and respect |

| To ensure access to competent health professionals and to their continuous support |

| To provide compassionate care |

| To make the patient and the family feel heard and understood |

| To respect the patient’s autonomy, preferences and wishes |

| To provide quality of death and dying |

Discussion

We identified a set of 14 core outcomes for Best Care for the Dying Person via a Delphi study and a consensus meeting involving clinicians, researchers, bereaved family members, and patient representatives, following the approach developed by COMET. 10 The resulting set represents multiple dimensions essential to the care of patients in the last days of life and shares consistent domains and outcomes with those identified for earlier phases of serious illness and palliative care,6,20 such as managing physical symptoms, psychological support, and ensuring patient dignity. This continuity underscores the importance of addressing key needs throughout the trajectory of illness, from diagnosis to the last days of life.

The more general outcomes that we identified, namely, “to reduce suffering,” “to ensure dignity and respect,” “to ensure access to competent health professionals and to their continuous support,” “to provide compassionate care,” “to make the patient and the family feel heard and understood,” and “to respect the patient’s autonomy, preferences and wishes” are closely linked to factors that characterize best quality, patient-centered health care within21,22 and beyond Palliative Care. For example, the goals of care concept, especially within the context of serious illness and shared decision-making, mirrors some of these outcomes: promotion of patient autonomy and patient-centered care, respecting the patient’s underlying values and priorities, and the provision of sensitive psychological and emotional support for patients and their families. 23 Similarly, the Lancet Global Health Commission report highlights the need not only of a highly adaptable system with outcomes related to the changing population’s needs, but also focused on other care principles such as equity, trust, and access to competent care. 24

In terms of the more specific core outcomes, the bio-psycho-social model central to palliative care since its inception remains present via the three symptom-related outcomes of addressing “pain,” “anxiety”, and “respiratory symptoms”. These dimensions are widespread within quality of end-of-life care international frameworks, as well as in the many existing measurement tools within palliative care. For example, a comprehensive review of systematic reviews and gray literature 25 identified 152 palliative care assessment tools, with 58 focusing on physical symptoms. Within these, 25 specifically assess pain, while 26 target dyspnea. Additionally, among 26 tools focused on psychosocial and psychiatric aspects, 10 measure anxiety.

More explicit for the last days of life, extensive work has been done by the International Collaborative for Best Care for the Dying Person, which developed the “10/40-model,” a framework for quality improvement in this field. This model was recently validated via a consensus process. 26 The “10/40” model and the newly developed core outcome set share the importance of specific outcomes such as “recognizing and communicating the dying phase,” as well as “addressing pain,” “anxiety,” “respiratory symptoms” and the “fear of death.” The explicit wish “to be able to say goodbye” and to “have permanent access to the dying person,” as expressed in our core set, may reflect the perspective of patient representatives and family carers who were an integral part of our expert panel, but not of other studies. 27 Other models or strategies to evaluate care quality in palliative care or more specifically the care for the dying person such as “Care of the Dying Evaluation” CODE, 28 the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standards on the care of dying adults, 29 or the Swedish Palliative Registry, 30 a national database to evaluate care for the dying patients in Sweden, identify similar items to the developed core outcome set, as essential indicators for quality of care for the dying. The overlap with existing quality indicators can be explained by the inclusion of both patient and care process outcomes in the core outcome set, ensuring that it captured not only the clinical effects of interventions but also how care in the last days of life can be aligned with best practices.

Limitations and strengths

Conceived as a work package within the larger European Union funded “iLIVE” project 13 our study involved collaboration with experts in the field of care for the dying person. The overreliance on obtaining samples via these experts, may have introduced a potential selection bias. Additionally, the core outcome set does not include outcomes relevant to the family or covering spiritual aspects. While these outcomes were included in the Delphi, they ranked too low to be seen as core. Health economics-related outcomes were not considered for inclusion in the Delphi, but recommendations for their implementation exist.31,32 Additionally, in developing the outcome list for the Delphi, some important outcomes may have been under-included. This is a recognized risk in core outcome set development 10 that needs to be balanced against the total number of outcomes to be shown in the Delphi. While we made efforts to mitigate it, such as by allowing participants to suggest new outcomes during the first Delphi round, the risk of having excluded some relevant outcomes remains. Moreover, capturing the direct perspectives of patients and families in the dying phase remains particularly challenging. In our study, we could only involve patient representatives rather than patients themselves, due to how advanced their condition would have needed to be to capture their perspectives during the dying phase. Additionally, the family members included were bereaved, meaning that their views were collected retrospectively. This approach, while valuable, may not fully have captured the immediate needs of patients and their families during the dying phase. This highlights how difficult it is to directly involve individuals facing imminent death, as both ethical considerations and their physical and psychological state can often make participation impractical or distressing. Despite these limitations, our core outcome set is the first in palliative care to fully adhere to the rigorous methodology of COMET, including a large sample size and international variability. A key strength of this approach was that the perspectives of non-professional stakeholders, such as family members and patient representatives, were given equal weight alongside those of healthcare professionals and researchers, ensuring a more inclusive approach to the development of the core outcome set. The international collaboration within the “iLIVE” project allowed to integrate experts and panel members from different cultures representing diverse European regions and beyond. The two international Delphi rounds and the final online consensus meeting were performed rigorously with key stakeholders from 20 countries. Importantly, our core outcome set focused on “what” to measure, hence future studies should focus on specifying the instruments via which these outcomes could effectively be measured following established guidelines. 33

Conclusion

This core outcome set for best care for a dying patient, focusing specifically on the last days of life, may impact future research and clinical practice through its broad geographical and cultural diversity and its approach to adding the perspectives of patient representatives and family carers. It can also serve as a solid basis for future definition of comparable core outcomes in research, and for the development of meaningful quality indicators for the care of the dying regardless of country, care setting, financial resources and care organization.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241300867 for A core outcome set for best care for the dying person: Results of an international Delphi study and consensus meeting by Sofia C. Zambrano, Martina Egloff, Valentina Gonzalez-Jaramillo, Andri Christen-Cevallos Rosero, Simon Allan, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, John Ellershaw, Claudia Fischer, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Urška Lunder, Marisa Martin-Rosello, Stephen Mason, Birgit Rasmussen, Valgerdur Sigurðardóttir, Judt Simon, Vilma A. Tripodoro, Agnes van der Heide, Lia van Zuylen, Raymond Voltz, Carl Johan Fürst, Paula R. Williamson, Steffen Eychmüller and on behalf of iLIVE in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants in the Delphi study and consensus meeting.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PRW chairs the COMET Management Group. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: iLIVE is a project funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant agreement no: 825731. The dissemination activities within the iLIVE project do not represent the opinion of the European Community and only reflect the opinion of the authors and/or the Consortium.

SCZ was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) via an Eccellenza Professorial Fellowship (grant number PCEFP1_194177).

Data Availability: Data from the Delphi study can be obtained via the corresponding author.

ORCID iDs: Zambrano Sofia C  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0918-9722

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0918-9722

Gonzalez-Jaramillo Valentina  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2470-7022

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2470-7022

Fischer Claudia  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7574-8097

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7574-8097

Eychmüller S  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1734-2237

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1734-2237

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Qual Health Care 1999; 8(4): 219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. University of Wollongong. Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration, 2020, https://www.uow.edu.au/australasian-health-outcomes-consortium/pcoc/ accessed October 13, 2023 2023).

- 3. Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, et al. EAPC white paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services - recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on outcome measurement. Palliat Med 2016; 30(1): 6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harding R, Higginson IJ; PRISMA. PRISMA: A pan-European co-ordinating action to advance the science in end-of-life cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care 2010; 46(9): 1493–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(1): 96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Wolf-Linder S, Dawkins M, Wicks F, et al. Which outcome domains are important in palliative care and when? an international expert consensus workshop, using the nominal group technique. Palliat Med 2019; 33(8): 1058–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015; 49(4): 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carter H, MacLeod R, Brander P, et al. Living with a terminal illness: patients’ priorities. J Adv Nurs 2004; 45(6): 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan RJ, Webster J, Bowers A. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 2(2): CD008006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017; 18(Suppl 3): 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zambrano SC, Haugen DF, van der Heide A, et al. ; iLIVE consortium. Development of an international core outcome set (COS) for best care for the dying person: study protocol. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19(1): 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. González-Jaramillo V, Luethi N, Egloff M, et al. Outcomes of care during the last month of life: a systematic review to inform the development of a core outcome set. Ann Palliat Med 2024; 13(3): 627–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yildiz B, Allan S, Bakan M, et al. Live well, die well – an international cohort study on experiences, concerns and preferences of patients in the last phase of life: the research protocol of the iLIVE study. BMJ Open 2022; 12(8): e057229. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome set-standards for reporting: the COS-STAR statement. PLoS Med 2016; 13(10): e1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitchell JW, Noble A, Baker G, et al. Protocol for the development of an international core outcome set for treatment trials in adults with epilepsy: the EPilepsy outcome set for effectiveness trials project (EPSET). Trials 2022; 23(1): 943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, et al. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 96: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gargon E, Crew R, Burnside G, et al. Higher number of items associated with significantly lower response rates in COS Delphi surveys. J Clin Epidemiol 2019; 108: 110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64(4): 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munblit D, Nicholson T, Akrami A, et al. A core outcome set for post-COVID-19 condition in adults for use in clinical practice and research: an international Delphi consensus study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 715–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palliative Care Evidence Review Service. What outcome domains are considered core to assessing the impact of adult specialist palliative care services in Wales? a rapid review. Cardiff: Palliative Care Evidence Review Service; (PaCERS); 2021. December. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Finkelstein EA, Bhadelia A, Goh C, et al. Cross country comparison of expert assessments of the quality of death and dying 2021. J Pain Symptom Manag 2022; 63(4): e419–e429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ingersoll LT, Saeed F, Ladwig S, et al. Feeling heard and understood in the hospital environment: benchmarking communication quality among patients with advanced cancer before and after palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018; 56(2): 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Secunda K, Wirpsa MJ, Neely KJ, et al. Use and meaning of “goals of care” in the healthcare literature: a systematic review and qualitative discourse analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35(5): 1559–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6(11): e1196–e1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aslakson RA, Dy SM, Wilson RF, et al. Patient- and caregiver-reported assessment tools for palliative care: summary of the 2017 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Technical Brief. J Pain Symptom Manag 2017; 54(6): 961–972.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGlinchey T, Early R, Mason S, et al. Updating international consensus on best practice in care of the dying: a Delphi study. Palliat Med 2023; 37(3): 329–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LPM, et al. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr 2016; 24(4): 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mayland CR, Keetharuth AD, Mukuria C, et al. Validation of ‘Care Of the Dying Evaluation’ (CODE(TM)) within an international study exploring bereaved relatives’ perceptions about quality of care in the last days of life. J Pain Symptom Manag 2022; 64(1): e23–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Care of dying adults in the last days of life: quality standard. London: NICE, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lind S, Adolfsson J, Axelsson B, et al. Quality indicators for palliative and end of life care: a review of Swedish policy documents. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(4): 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischer C, Masel EK, Simon J. Methodological factors regarding patient-reported outcome information for value assessment in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2024; 13(2): 440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fischer C, Bednarz D, Simon J. Methodological challenges and potential solutions for economic evaluations of palliative and end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2024; 38(1): 85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prinsen CAC, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials 2016; 17(1): 1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163241300867 for A core outcome set for best care for the dying person: Results of an international Delphi study and consensus meeting by Sofia C. Zambrano, Martina Egloff, Valentina Gonzalez-Jaramillo, Andri Christen-Cevallos Rosero, Simon Allan, Pilar Barnestein-Fonseca, John Ellershaw, Claudia Fischer, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Urška Lunder, Marisa Martin-Rosello, Stephen Mason, Birgit Rasmussen, Valgerdur Sigurðardóttir, Judt Simon, Vilma A. Tripodoro, Agnes van der Heide, Lia van Zuylen, Raymond Voltz, Carl Johan Fürst, Paula R. Williamson, Steffen Eychmüller and on behalf of iLIVE in Palliative Medicine