Abstract

A 92-year-old woman with normal systolic function had recently begun using the newly approved phosphodiesterase III inhibitor cilostazol when she was admitted with lower-extremity pain. Cilostazol is indicated for patients with intermittent claudication and contraindicated for patients with congestive heart failure. Two days after admission, the patient developed ventricular tachycardia. Cilostazol was discontinued, and shortly thereafter the ventricular tachycardia subsided. In this case, cilostazol was apparently an important predisposing factor for ventricular tachycardia. (Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29:140–2)

Key words: Cilostazol; phosphodiesterase inhibitors/adverse effects; tachycardia, ventricular

Since 1999, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor cilostazol (Pletal®, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Rockville, Md) has been approved in the United States for the reduction of symptoms of intermittent claudication. 1 It is contraindicated, however, in patients with congestive heart failure. 1 Cilostazol specifically inhibits type III phosphodiesterase (PDE III), which is compartmentalized in cardiac monocytes and vascular smooth vessels due to its sarcoplasmic reticulum-anchoring moiety; PDE III is also found in platelets. 2 Type III phosphodiesterase breaks down cyclic AMP (cAMP); inhibition of PDE III causes a cascade of effects that includes higher tissue levels of cAMP, local activation of protein kinase A, phosphorylation of phospholamban, and, ultimately, cardiac contractility. 1,2 We report a case of sudden-onset ventricular tachycardia in an elderly woman with lower-extremity pain and a recent history of cilostazol use.

Case Report

In April 2001, a 92-year-old woman presented at our institution with left-lower-extremity pain. Ten days before, she had experienced the sudden onset of this pain, in association with weakness, coldness, and bluish discoloration of the limb. The patient had a history of well controlled hypertension and chronic atrial fibrillation (for which she was on anticoagulant therapy). She lived alone and before this event had enjoyed a very active life. At the time of her admission, her medications included cilostazol (which she had started just a few days earlier), triamterene, clopidogrel, levothyroxine, digoxin, and aspirin.

On physical examination, the arterial blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, the heart rate was 60 beats/min, and the heart beat was irregular without an S3 gallop. Lower-extremity examination revealed the presence of normal pulses at the femoral level, but the absence of pulses below that level. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation and intraventricular conduction delay. Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 55% to 60% and a dilated right atrium. The other chambers of the heart were normal in size.

Laboratory studies revealed a subtherapeutic prothrombin time (international normalized ratio [INR] of 1.3). Other test results were: hemoglobin, 11.3 g/dL; hematocrit, 33.6%; sodium, 135 mmol/L; potassium, 4.2 mmol/L; magnesium, 3.1 mEq/L; calcium, 8.9 mg/dL; digoxin, 1.4 μg/L; BUN, 22 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL; chloride, 104 mmol/L; pH, 7.42; arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PCO2), 37 mmHg; and arterial oxygen partial pressure (PO2), 93 mmHg.

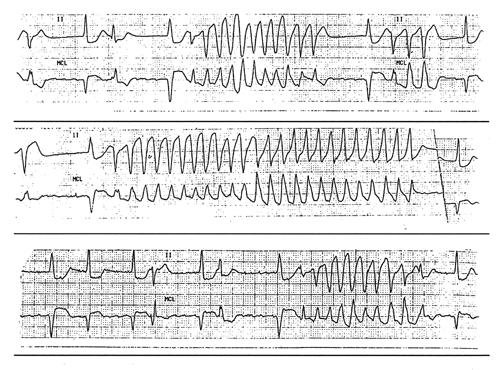

The patient was admitted and was started on intravenous heparin. The next day, selective arteriography revealed a fresh thrombus in the superficial femoral artery. The thrombus was extracted successfully, and angioplasty was performed on the artery. Two days after angioplasty, the patient developed several runs of polymorphic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 1). Empiric magnesium therapy did not resolve the arrhythmia. Cilostazol was discontinued, and the ventricular tachycardia runs subsided shortly thereafter. The patient was discharged on medical therapy. At her last follow-up, in October 2001, there had been no recurrence of ventricular tachycardia.

Fig. 1 Electrocardiograms showing ventricular tachycardia in this patient.

Discussion

Although nonspecific PDE inhibitors such as theophylline and caffeine were identified over 30 years ago, it was not until the 1980s that a number of specific PDE isoenzyme subclass-specific inhibitors became available. 3 Many organs, including the heart, contain members of all of the known PDE isoenzyme families. Several inhibitors of the PDE III family (for example, milrinone and amrinone) are used in the treatment of heart failure. 3

Although this group of drugs has not been shown to be directly arrhythmogenic, the ability of its members to increase levels of cAMP could theoretically predispose patients to ventricular arrhythmias. Supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias due to increasing ventricular automaticity have been reported in some patients with severe congestive heart failure who used amrinone. 4 In a high-risk population treated with milrinone, supraventricular and nonsustained ventricular tachycardias have been observed. 5 In a trial comparing milrinone and digoxin, milrinone performed no better than digoxin and, in fact, increased ventricular arrhythmias. 6 There are even reports that administration of other PDE inhibitors, such as the phosphodiesterase V inhibitor sildenafil (Viagra®), can prolong cardiac repolarization and Q-T interval in rats. 7

In animal studies, cilostazol increased heart rate, myocardial contractile force, ventricular automaticity, and ventricular conduction. 1 In human beings, its use has been associated with increased mean heart rate, conductivity in the atrioventricular node, ventricular premature beats, and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. 8,9 In a study comparing the effects of cilostazol and milrinone on cAMP, cilostazol and milrinone caused similar increases in cAMP levels in human and rabbit platelets, but milrinone elevated cAMP in rabbit cardiac monocytes more than did cilostazol. 10 These results suggest that the cardiac effects of cilostazol cannot be explained solely by PDE inhibition, since cilostazol and milrinone inhibit PDE III with similar potency. 10

In the present case, an elderly woman with no apparent predisposing factors and a recent history of cilostazol use suffered several episodes of ventricular arrhythmia. The patient had a normal ejection fraction and, except for cilostazol, was not using any drugs that alone or in combination might induce ventricular tachyarrhythmias. These facts and the prompt resolution of the arrhythmia after discontinuation of cilostazol suggest that, in this case, cilostazol was a predisposing factor for ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Conclusions

Cilostazol (and possibly other PDE III inhibitors) poses a probable risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmia, even in patients with normal left ventricular function. This risk might alter the risk-to-benefit ratio in certain populations of patients, although more data will be needed to determine exactly which populations might be affected.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Ali Massumi, MD, 6624 Fannin, Suite 2480, Houston, TX 77030

References

- 1.Approval of New Drug Application for Pletal (Cilostazol). Letter to Otsuka American Pharmaceutical, Inc., from Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health & Human Services; Rockville, Md; January 15, 1999. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/news/cilostazol/20863appletter.htm. Accessed 23 January 2002.

- 2.Bristow MR, Port JD, Kelly RA. Treatment of heart failure: pharmacological methods. In: Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P, editors. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. p. 562–99.

- 3.Kelley RA, Smith TW. Pharmacological treatment of heart failure. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman & Gilman's The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. p. 809–38.

- 4.Opie LH, Gersh BJ. Acute inotropes and inotropic dilators. In: Opie LH. Drugs for the heart. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. p. 154–86.

- 5.Pflugfelder PW, O'Neill BJ, Ogilvie RI, Beanlands DS, Tanser PH, Tihal H, et al. A Canadian multicentre study of a 48 h infusion of milrinone in patients with severe heart failure. Can J Cardiol 1991;7:5–10. [PubMed]

- 6.DiBianco R, Shabetai R, Kostuk W, Moran J, Schlant RC, Wright R. A comparison of oral milrinone, digoxin, and their combination in the treatment of patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1989;320:677–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Butrous G, Siegel RL. Sildenafil (Viagra) prolongs cardiac repolarization by blocking the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current. Circulation 2001;103: E119–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Toyonaga S, Nakatsu T, Murakami T, Kusachi S, Mashima K, Tominaga Y, et al. Effects of cilostazol on heart rate and its variation in patients with atrial fibrillation associated with bradycardia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2000;5:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Atarashi H, Endoh Y, Saitoh H, Kishida H, Hayakawa H. Chronotropic effects of cilostazol, a new antithrombotic agent, in patients with bradyarrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1998;31:534–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cone J, Wang S, Tandon N, Fong M, Sun B, Sakurai K, et al. Comparison of the effects of cilostazol and milrinone on intracellular cAMP levels and cellular function in platelets and cardiac cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1999;34:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed]