Abstract

The self-renewal characteristics of stem cells render them vital engines of development. To better understand the molecular mechanisms that determine the properties of stem cells, transcript profiling was conducted on quiescent center (QC) cells from the Arabidopsis thaliana root meristem. The AGAMOUS-LIKE 42 (AGL42) gene, which encodes a MADS box transcription factor whose expression is enriched in the QC, was used to mark these cells. RNA was isolated from sorted cells, labeled, and hybridized to Affymetrix microarrays. Comparisons with digital in situ expression profiles of surrounding tissues identified a set of genes enriched in the QC. Promoter regions from a subset of transcription factors identified as enriched in the QC conferred expression in the QC. These studies demonstrated that it is possible to successfully isolate and profile a rare cell type in the plant. Mutations in all enriched transcription factor genes including AGL42 exhibited no detectable root phenotype, raising the possibility of a high degree of functional redundancy in the QC.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells, valued for their medical potential, have long been recognized for their self-renewal properties and lack of differentiated characteristics. These same features also render them vital engines of development; the process of building tissues and organs relies on the availability of a proliferative pool of undifferentiated cells. In animals, organogenesis is largely completed in the embryo, so that adult stem cells are primarily involved in homeostasis, germline maintenance, and repair of damaged tissues. To respond to environmental challenges without the benefit of locomotion, plants have evolved a radically different life strategy in which organogenesis provides morphological changes throughout postembryonic development. Continuous growth is a function of cell divisions in the meristems, which are maintained through the activity of stem cell populations.

In particular, the root meristem is an excellent system in which to study stem cell biology. The root meristem is a largely invariant structure made up of few tissue types that undergo predictable divisions and do not produce lateral structures (Dolan et al., 1993). Primary root tissues are organized in concentric cylinders of epidermis, ground tissue (cortex and endodermis), and stele from outside to in (Figure 1A). These, in turn, are made up of longitudinal cell files that originate from single cells termed initials (Scheres et al., 1994). Initials fulfill the minimal definition of a stem cell by producing two cells in every division: the regenerated initial, and a daughter cell that differentiates progressively upon displacement by further rounds of division. Two terminal tissues, the columella (central) and lateral root cap, are also produced by the activity of initials. Together, initials for all tissue types surround a group of four to seven mitotically less active cells in Arabidopsis thaliana known as the quiescent center (QC).

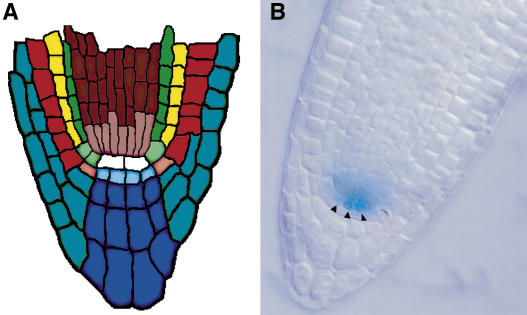

Figure 1.

ET433 Enhancer Trap Expression.

(A) Scheme of the Arabidopsis root tip. Tissues are depicted in a median longitudinal section with corresponding initials in lighter color at the base of each cell file. Epidermis (orange), cortex (yellow), endodermis (green), and stele (red) make up most of the root, and lateral (turquoise) and columella (blue) root caps surround the apex. Epidermis and lateral root cap share a common initial, as do endodermis and cortex. Initial cells surround the QC (white).

(B) ET433 staining in a lateral root tip after emergence from the primary root. Pattern is identical in primary root tips at 7 d after germination. Arrowheads indicate QC cells.

Nearly every animal system relies on local signaling to form a stem cell niche, or microenvironment, that promotes stem cell status (reviewed in Spradling et al., 2001; Fuchs et al., 2004). Laser ablation experiments have shown that this is also the case for the plant root and have identified the QC as the source of a signal that inhibits differentiation of the contacting initials (van den Berg et al., 1997). QC cells position the stem cell niche but also behave as stem cells in their own right. Occasional QC divisions are self-renewing and replenish initials that have been displaced from their position (Kidner et al., 2000).

Little is known about the molecular mechanisms that determine the properties of the QC or initial cells. Stem cell fate has been correlated with the position of a local maximum of auxin phytohormone perception in the QC and columella root cap initials (Sabatini et al., 1999). Auxin signaling is necessary for QC initiation in the embryo (Hardtke and Berleth, 1998; Hamann et al., 2002) and may direct expression of the PLETHORA1 (PLT1) and PLT2 transcription factors, which function redundantly in specifying QC fate (Aida et al., 2004). The SCARECROW (SCR) and SHORT-ROOT (SHR) transcriptional regulators were initially isolated for their role in radial patterning (Benfey et al., 1993) but are also required for QC function (Sabatini et al., 2003). In plt1 plt2 as well as in scr and shr mutants, some QC markers are not expressed and the root meristem progressively loses its ability to undergo cell divisions (Sabatini et al., 2003; Aida et al., 2004). Recently, ectopic expression of CLAVATA3 (CLV3) and related putative ligands suggested the existence of a CLV signaling pathway involved in regulating cell divisions in the root meristem (Casamitjana-Martinez et al., 2003; Hobe et al., 2003). CLV3 signaling through the CLV1 receptor kinase defines an autoregulatory loop in the shoot meristem that maintains the size of the stem cell population (Fletcher et al., 1999; Jeong et al., 1999; Trotochaud et al., 1999).

Most of what is known about stem cell function involves regulation either by transcription factors (SCR, SHR, or PLT) or signal transduction pathways that produce transcriptional changes (auxin and possibly a CLV pathway). Thus, at least some of the differences between these cells and their differentiating offspring must occur at the level of gene expression. Fundamental questions remain regarding what transcriptional features distinguish the QC and to what extent stem cells in root and shoot share molecular machinery.

Here, we define a set of genes enriched in the QC. To produce this gene set, we first generated a QC-enriched marker based on cis regulatory sequences of the MADS box transcription factor AGAMOUS-LIKE 42 (AGL42). Using a cell-sorting strategy, we obtained the transcriptional profile of the QC and compared it against a high-resolution spatial map, or digital in situ, of gene expression in the root (Birnbaum et al., 2003). This analysis provides a broad picture of which genes contribute to QC activity and maintenance and forms the basis for a reverse genetic screen aimed at assigning roles for these factors. Our finding that none of the transcription factors surveyed, including AGL42 and several floral regulators, gave rise to root phenotypes when mutated argues for a significant degree of redundancy among transcriptional regulators in the QC. We describe the use of the root digital in situ in combination with phylogenetic information as a strategy to narrow the focus of multiple mutant combinations in reverse genetic analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression of the AGL42 MADS Box Gene Marks the QC

To initiate a reverse genetic characterization of the root stem cell niche, we screened an enhancer trap library carrying the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter driven by a minimal promoter (Malamy and Benfey, 1997). One line, ET433, showed striking expression in the QC cells, with much weaker expression in cells proximal to the QC (Figure 1B). Flanking sequences isolated from the tagged locus revealed that ET433 was inserted in the first intron of the MADS box gene AGL42 (Figure 2A).

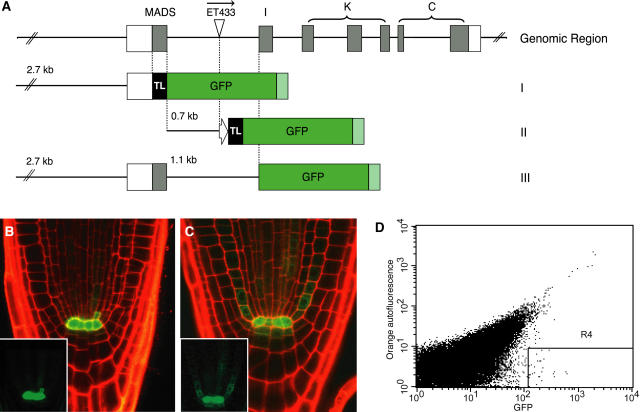

Figure 2.

AGL42 cis Elements Mark the QC for Cell Sorting.

(A) AGL42 genomic region (top), indicating exons (closed boxes) with corresponding protein-coding domains above, 5′ and 3′ UTRs (open boxes), and ET433 enhancer trap insertion site and orientation in the first intron. Promoter (construct I), partial first intron (construct II), and promoter plus intron (construct III) fusions to GFP are indicated with corresponding lengths of promoter and intron sequence. Note that terminator sequences (light green) were not derived from AGL42. MADS, MADS DNA binding domain; I, intervening region; K, K domain; C, C-terminal domain; TL, signal sequence for endoplasmic reticulum; block arrow, −46 minimal promoter from Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter used in ET433.

(B) Overlay of GFP (green) and propidium iodide (red) channels of construct III imaged at 4 d after germination. The inset shows the GFP channel only.

(C) Same as (B) at 7 d after germination.

(D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter acquisition dot plots. Each dot corresponds to a single sorting event, and only cells with a high ratio of green to orange fluorescence (within the trapezoidal R4 gate) are collected. Background protoplasts show nearly equivalent levels of orange and green autofluorescence.

We were interested in using the AGL42 expression pattern as a vital marker of QC identity. To this end, we created a series of transgenes bearing presumptive cis element–containing sequences of AGL42 fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Figure 2A). Neither the promoter with the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) nor a fragment of the first intron upstream of the ET433 insertion site conferred expression detectable with confocal laser scanning microscopy. In combination, however, the promoter, 5′ UTR, first exon, and complete first intron (referred to as AGL42:GFP) recapitulated the enhancer trap pattern (Figure 2B), reminiscent of the regulation of AGAMOUS by cis elements within its large second intron (Sieburth and Meyerowitz, 1997; Deyholos and Sieburth, 2000).

Isolation of the AGL42:GFP Marked Population

Acquiring a snapshot of transcription for a specific tissue requires that it be isolated from the rest of the organism. Large QCs such as those found in the maize root are amenable to microdissection, but this approach would be extremely challenging given the four- to seven-cell size of the Arabidopsis QC. As an alternative, Birnbaum et al. (2003) developed a method whereby roots possessing a subpopulation of fluorescing cells can be protoplasted and sorted without significantly disturbing their transcriptional status. Using this technique, we were able to sort AGL42:GFP-positive cells, then extract, label, and amplify their RNA. Plants were harvested at 4 d after germination, when expression was most tightly restricted to the QC (Figures 2B and 2C). However, a small fraction of the roots also exhibited weak expression in stele and ground tissue initials at this stage.

The low number of cells marked by AGL42 expression poses a unique challenge for sorting, because even a small proportion of incorrectly sorted cells can skew the RNA pool. We limited the possibility of collecting autofluorescent background cells by using a very conservative fluorescence gate (Figure 2D). Wild-type roots with no GFP expression sorted using similar parameters collected <10% of the number of positive cells in the AGL42 sort (data not shown). In addition, only tips were harvested from the seedling roots to reduce the proportion of nonfluorescing cells. After hybridization to Affymetrix ATH1 microarrays, we obtained two clean replicates, the transcriptional profile of which had a correlation coefficient of 0.90.

Comparison with Other Root Tissues Defines a Set of QC-Enriched Transcripts

Previously, we had obtained global expression profiles for stele, ground tissue, atrichoblasts (epidermal cells lacking root hairs), and lateral root cap (Birnbaum et al., 2003). To identify the set of genes specifically enriched in the QC, it was necessary to compare AGL42:GFP with all surrounding tissues. However, a critical tissue, the columella root cap, was not represented in the data set. As a first step, we expanded the spatial expression map to include columella root cap by sorting seedlings expressing the PET111 enhancer trap (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). This reporter marks all columella cells except for the initials.

Next, we performed a linear mixed-model analysis of variance on the microarray data using SAS statistical software (Cary, NC). This strategy disregards mismatch probe data that can artificially dampen signal while removing technical noise, modeled on the Affymetrix GeneChip platform (Wolfinger et al., 2001; Chu et al., 2002). The analysis yielded p values for pairwise comparisons of AGL42:GFP against each of the other cell populations on a per-gene basis. These were converted to q values representing the false-discovery rate parameter to correct for multiplicity of testing (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). Expression means and the pairwise comparison results with p and q values for ∼22,000 genes are available in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3 online.

To determine enrichment, we applied a rigid q value cutoff corresponding to less than one predicted false positive (q < 0.0001 for all except columella, which is q < 0.001) and required a fold change of at least 1.5 for every pairwise comparison. Output was filtered further to remove sucrose and protoplasting effects (see Methods and Supplemental Table 1 online), resulting in a final set of 290 QC-enriched transcripts (Tables 1 and 2). No transcripts were significantly depleted in AGL42-expressing cells using these criteria.

Table 1.

Number of Enriched Genes by Category

| Category | No. Enriched |

|---|---|

| Hormone-related | |

| Auxin | 5 |

| Gibberellic acid | 3 |

| Brassinosteroid | 1 |

| Receptor-like kinases | 16 |

| Phosphatidylinositol and Ca2+ signaling | 5 |

| Transcriptional regulators | 37 |

| General transcription | 11 |

| Protein turnover | 12 |

| RNA silencing | 4 |

| Cell division | 2 |

| DNA replication and repair | 10 |

| Cell wall | 8 |

| Cytoskeleton | 7 |

| Transporter, carrier, or channel | 15 |

| Disease resistance | 4 |

| Metabolism/enzymatic activity | 63 |

| Other | 25 |

| Unknown | 62 |

| Total | 290 |

Table 2.

All Enriched Transcripts by Category

| AGI No.a | Description | Gene Name(s) | Meanb | Ratioc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auxin | ||||

| At2g20610 | Tyr aminotransferase | SUPERROOT1 (SUR1); RTY/ALF1 | 8.7 | 5.5 |

| At4g31500 | Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | SUPERROOT2 (SUR2); CYP83B1 | 31.9 | 18.0 |

| At3g62100 | Aux/IAA family transcriptional repressor | IAA30 | 4.8 | 5.5 |

| At2g21050 | AAAP (amino acid/auxin permease); AUX1 family | 10.9 | 7.4 | |

| At1g73590 | Auxin efflux carrier | PIN-FORMED1 (AtPIN1) | 5.6 | 5.1 |

| Gibberellin | ||||

| At4g02780 | ent-Kaurene synthetase A | GA-DEFICIENT1 (GA1) | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| At5g25900 | Cytochrome P450 ent-kaurene oxidase | GA-DEFICIENT3 (GA3); CYP701A3 | 11.1 | 5.9 |

| At2g32440 | Cytochrome P450 ent-kaurene oxidase | CYP88A | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Brassinosteroid | ||||

| At1g55610 | LRR X receptor-like kinase | BRI1-LIKE (BRL1) | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Receptor-like kinases | ||||

| At4g21400 | DUF26 receptor-like kinase | 1.9 | 2.2 | |

| At4g21410 | DUF26 receptor-like kinase | 2.4 | 2.9 | |

| At3g58690 | Extensin | 2.4 | 2.0 | |

| At3g53380 | Lectin receptor-like kinase | 2.5 | 3.2 | |

| At1g34210 | LRR II | 1.9 | 2.2 | |

| At5g45780 | LRR II | 1.6 | 2.2 | |

| At5g67200 | LRR III | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| At5g51560 | LRR IV | 2.6 | 2.2 | |

| At2g45340 | LRR IV | 4.7 | 6.5 | |

| At1g11140 | LRR V | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| At1g53440 | LRR VIII-2; S-domain (type 1) | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| At5g48940 | LRR XI | 5.4 | 3.2 | |

| At5g13290 | Receptor-like kinase | 1.7 | 2.3 | |

| At5g39790 | Pro-rich receptor-like kinase | 1.4 | 2.0 | |

| At5g56790 | Pro-rich receptor-like kinase | 10.4 | 6.8 | |

| At5g15080 | RLCK VII | 1.8 | 1.9 | |

| Phosphatidylinositol and Ca2+ signaling | ||||

| At5g63980 | 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase; PI signaling | FIERY1 (FRY1); AtSAL1 | 10.0 | 2.8 |

| At5g10170 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase | 3.9 | 4.9 | |

| At4g05520 | Calcium ion binding EF hand | 1.8 | 2.0 | |

| At3g56690 | Calmodulin binding protein | 2.0 | 1.8 | |

| At1g72670 | Calmodulin binding protein | 1.6 | 1.9 | |

| Transcriptional regulation | ||||

| At1g25470 | AP2 | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| At1g72360 | AP2 | 2.5 | 3.1 | |

| At2g41710 | AP2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | |

| At3g20840 | AP2 | PLETHORA1 (PLT1) | 6.3 | 5.7 |

| At5g17430 | AP2 | 5.0 | 5.9 | |

| At1g35460 | bHLH | AtbHLH80 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| At2g27230 | bHLH | 5.2 | 3.4 | |

| At3g19500 | bHLH | AtbHLH113 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| At1g12860 | bHLH with F-box | AtbHLH33 | 3.4 | 4.5 |

| At1g21740 | bZIP | 1.8 | 1.6 | |

| At1g68640 | bZIP | PERIANTHIA (PAN); AtbZIP46 | 4.1 | 5.6 |

| At3g60630 | GRAS | SCL6 | 3.9 | 1.9 |

| At2g01430 | HD-Zip | AtHB-17 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| At5g20240 | MADS box (type II) | PISTILLATA (PI) | 4.1 | 7.3 |

| At5g47390 | Myb | 2.7 | 1.8 | |

| At5g11510 | Myb (R2R3) | AtMYB3R4 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| At5g17800 | Myb (R2R3) | AtMYB56 | 6.1 | 6.4 |

| At5g60890 | Myb (receptor-like kinase); Trp biosynthetic pathway | ALTERED TRYPTOPHAN REGULATION (ATR1); AtMYB34 | 9.2 | 12.1 |

| At5g44190 | Myb; GARP | 1.3 | 1.8 | |

| At1g69490 | NAC | NAC-LIKE; ACTIVATED BY AP3/PI (NAP) | 8.6 | 6.3 |

| At3g13000 | NAC | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| At2g13840 | Putative DNA binding | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

| At4g22770 | Putative DNA binding | 1.9 | 2.1 | |

| At5g48090 | Putative DNA binding | 1.2 | 1.6 | |

| At5g51590 | Putative DNA binding | 3.0 | 1.8 | |

| At5g54930 | Putative DNA binding | 1.8 | 1.9 | |

| At1g14410 | Putative DNA binding; p24-related | 2.6 | 1.8 | |

| At5g51910 | TCP | 2.8 | 2.8 | |

| At1g16070 | TUBBY | ATLP8 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| At1g76900 | TUBBY (F-box) | ATLP1 | 4.3 | 2.5 |

| At5g48250 | Zn finger (C2C2) CO-like B-box | COL10 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| At3g50870 | Zn finger (C2C2) GATA | HANABA TARANU (HAN) | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| At5g03150 | Zn finger (C2H2) | 2.4 | 2.9 | |

| At3g20880 | Zn finger (C2H2) | 8.2 | 8.3 | |

| At2g38970 | Zn finger (C3HC4 RING) | 4.1 | 4.1 | |

| At5g40320 | Zn finger (CHP-rich) | 1.8 | 2.0 | |

| At3g22780 | Zn finger (CPP1-related) | TSO1 | 3.2 | 1.8 |

| Transcription (general) | ||||

| At1g29940 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit | 4.8 | 2.2 | |

| At5g45140 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit | 2.5 | 2.1 | |

| At1g60620 | RNA polymerase subunit (isoform B) | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| At3g02980 | GCN5-related histone N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) family | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| At5g35330 | Methyl binding domain protein | MBD2 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| At4g23800 | Nucleosome/chromatin assembly factor (HMG homolog) | NFD6 | 5.3 | 2.9 |

| At3g03790 | Regulator of Chromosome Condensation (RCC1) family | 2.5 | 2.0 | |

| At5g43990 | SET-domain histone methyltransferase | SDG18; SET18; SUVR2 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| At2g18850 | SET-domain histone methyltransferase | 1.6 | 1.6 | |

| At2g17900 | SET-domain histone methyltransferase | ASHR1; SET37 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| At5g44560 | SNF7 family | 3.9 | 2.8 | |

| Protein turnover | ||||

| At3g23880 | F-box A3 subfamily protein | 2.0 | 2.6 | |

| At1g47340 | F-box A5 subfamily protein | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| At3g58530 | F-box B1 subfamily protein | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| At3g03360 | F-box B5 subfamily protein | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| At1g06630 | F-box B7 subfamily protein | 3.1 | 2.8 | |

| At4g05460 | F-box C5 subfamily protein | AtFBL20 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| At1g30090 | F-box D subfamily protein | 1.5 | 1.8 | |

| At1g68050 | F-box E subfamily protein with PAS and Kelch repeats | FKF1 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| At5g56380 | F-box family protein | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| At3g51530 | F-box family protein | 1.8 | 2.1 | |

| At1g47570 | Ubiquitin ligase complex; zinc finger (C3HC4 RING) | 2.2 | 1.9 | |

| At5g65450 | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-like | 1.5 | 1.7 | |

| RNA silencing | ||||

| At2g27040 | AGO1-related protein | ARGONAUTE4 (AGO4) | 5.7 | 2.8 |

| At5g43810 | AGO1-related protein | PINHEAD (PNH)/ZLL/AGO10 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| At3g03300 | DEAD/DEAH box helicase | DICER-LIKE2 (DCL2) | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| At2g19930 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | 1.3 | 1.6 | |

| Cell division | ||||

| At5g67260 | Cyclin | CYCD3;2 | 4.9 | 2.5 |

| At4g02060 | DNA replication licensing factor | PROLIFERA (PRL1) | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| DNA replication and repair | ||||

| At5g41880 | DNA polymerase α subunit (primase) activity | 2.4 | 1.9 | |

| At4g24790 | DNA polymerase III–like γ subunit | 1.5 | 1.9 | |

| At2g41460 | DNA (apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase (ARP) | 2.0 | 2.1 | |

| At1g19485 | HhH-GPD superfamily base excision DNA repair protein | 1.8 | 2.0 | |

| At3g22880 | Meiotic recombination protein | AtDMC1 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| At3g24320 | MutS family; mitochondrial recombination | CHLOROPLAST MUTATOR (CHM) | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| At4g02390 | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) | APP | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| At2g31320 | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) | 2.0 | 1.8 | |

| At3g14890 | PARP, DNA ligase zinc finger (nick sensor) | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| At1g21710 | Purine-specific base lesion DNA N-glycosylase | 2.6 | 1.9 | |

| Cell wall | ||||

| At2g31960 | Callose synthase gene | AtGSL3 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| At2g35650 | Cellulose-synthase–like gene | CslA7 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| At4g31590 | Cellulose-synthase–like gene | CslC5 | 3.2 | 2.6 |

| At2g28950 | Expansin | EXP6 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| At3g15720 | Polygalacturonase (predicted GPI-anchored) | 2.4 | 4.1 | |

| At3g53190 | Pectate and pectin lyase | 5.6 | 4.0 | |

| At2g26440 | Pectin methyl esterase | 4.6 | 7.3 | |

| At4g03210 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase | XTH9 | 4.6 | 5.4 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||

| At5g42480 | DNAJ plastid division protein (ARC6-like) | 2.7 | 2.3 | |

| At5g48360 | Formin homology-2 (FH2) domain protein | 3.3 | 3.4 | |

| At5g55000 | Formin homology (FH) binding protein | FIP2 | 2.5 | 2.1 |

| At5g60210 | Expressed protein slow myosin heavy chain 2 | 4.7 | 3.3 | |

| At4g33200 | Myosin | AtXI-I | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| At1g63640 | Kinesin | 2.3 | 1.7 | |

| At5g60930 | Kinesin | 1.9 | 2.2 | |

| Transporter, carrier, or channel | ||||

| At2g28070 | ABC (ATP binding cassette) transporter | WBC3 | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| At2g26900 | Bile acid:Na+ symporter | AtSbf1 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| At5g36940 | Cationic amino acid transporter–like | 2.0 | 1.7 | |

| At5g53130 | Cyclic nucleotide/voltage-regulated cation channel | 2.5 | 2.3 | |

| At5g57100 | Drug/metabolite transporter superfamily | 3.7 | 3.0 | |

| At3g05290 | Mitochondrial carrier | PHT2 | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| At5g01500 | Mitochondrial carrier | 4.6 | 2.6 | |

| At5g09690 | Mitochondrial mRNA splicing-2 protein; Mg transporter | 2.6 | 3.0 | |

| At1g33110 | Multiantimicrobial extrusion family (MATE) transporter | 3.4 | 4.0 | |

| At3g17650 | Oligopeptide transporter OPT | 2.1 | 1.9 | |

| At3g47950 | Plasma membrane H+-ATPase | AHA4 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| At1g59740 | Proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter | MRS2 | 5.7 | 7.3 |

| At2g26180 | SF sugar porter | 3.3 | 2.6 | |

| At2g16990 | Tetracycline transporter–like | 1.6 | 2.2 | |

| At4g33670 | Voltage-gated K+ channel β subunit | 3.4 | 2.2 | |

| Disease resistance | ||||

| At1g58410 | CNL (CC-NBS-LRR) class protein | 1.8 | 2.4 | |

| At1g72840 | TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR) class protein | 3.7 | 3.9 | |

| At1g72850 | TN (TIR-NBS) class putative disease resistance protein | 4.9 | 6.0 | |

| At4g09940 | Avirulence-induced gene (AIG1) family | 2.1 | 3.9 | |

| Metabolism/enzyme | ||||

| At1g62960 | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (1-ACC) synthase | ACS10 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| At1g20490 | 4-Coumarate:CoA ligase 1 (4-coumaroyl-CoA synthase 1) | 4CL1 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| At4g39940 | Adenosine-5-phosphosulfate-kinase | 10.8 | 8.9 | |

| At5g08380 | α-Galactosidase | 2.8 | 3.0 | |

| At1g55510 | α-Galactosidase | 1.8 | 2.0 | |

| At5g09300 | α-Ketoacid decarboxylase E1 subunit | 11.6 | 5.8 | |

| At3g55850 | Amidohydrolase | LONG AFTER FAR-RED3 (LAF3) | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| At3g47040 | β-d-Glucan exohydrolase | 2.3 | 3.1 | |

| At4g09510 | β-Fructofuranosidase | 1.9 | 1.7 | |

| At5g57850 | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| At1g50110 | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | 2.6 | 1.9 | |

| At1g53520 | Chalcone-flavanone isomerase-related | 1.6 | 2.0 | |

| At1g69370 | Chorismate mutase (Phe biosynthesis) | CM3 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| At3g57470 | Cys-type endopeptidase activity | 1.7 | 2.2 | |

| At2g46650 | Cytochrome b5 | 5.6 | 7.4 | |

| At4g15920 | Cytochrome c oxidoreductase | 3.1 | 3.6 | |

| At4g12300 | Cytochrome P450; flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase | CYP706A | 2.5 | 3.2 |

| At4g39950 | Cytochrome P450; N-hydroxylase for Trp | CYP79B | 29.6 | 15.7 |

| At1g72040 | Deoxyguanosine kinase | 3.6 | 2.5 | |

| At3g23570 | Dienelactone hydrolase | 11.6 | 9.3 | |

| At1g48430 | Dihydroxyacetone kinase | 1.4 | 2.0 | |

| At1g12130 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase | 1.4 | 2.2 | |

| At1g49390 | Flavonol synthase | 2.1 | 2.8 | |

| At4g37550 | Formamidase | 1.7 | 2.7 | |

| At1g66250 | Glucan endo-1,3-β-glucosidase | 3.3 | 2.7 | |

| At4g29360 | Glucan endo-1,3-β-glucosidase | 2.7 | 3.1 | |

| At5g56590 | Glucan endo-1,3-β-glucosidase | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| At5g27380 | Glutathione synthetase | GSH2 | 7.8 | 3.2 |

| At1g11820 | Glycoside hydrolase family 17 | 2.2 | 1.9 | |

| At1g30530 | Glycosyl transferase | 1.1 | 2.1 | |

| At3g21750 | Glycosyl transferase | 4.2 | 5.7 | |

| At5g54690 | Glycosyl transferase | 1.6 | 2.0 | |

| At3g07270 | GTP cyclohydrolase 1 | 4.5 | 2.0 | |

| At1g79790 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase family | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| At3g25470 | Hemolysin | 5.0 | 2.4 | |

| At2g18950 | Homogentisate phytylprenyltransferase family protein | 2.5 | 3.2 | |

| At3g16260 | Hydrolase | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| At3g48410 | Hydrolase | 5.4 | 4.3 | |

| At2g04400 | Indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase | 10.2 | 4.7 | |

| At3g14360 | Lipid acylhydrolase–like | 2.1 | 2.0 | |

| At3g53450 | Lys decarboxylase | 2.1 | 3.0 | |

| At1g13270 | Met aminopeptidase | 2.0 | 2.6 | |

| At5g55130 | Molybdenum cofactor synthesis protein 3 | 4.7 | 2.2 | |

| At1g32160 | Obtusifoliol 14-α-demethylase | 1.5 | 1.7 | |

| At2g39220 | Patatin-like acyl hydrolase | 2.2 | 3.2 | |

| At5g13640 | Phosphatidylcholine-sterol O-acyltransferase | 2.6 | 2.1 | |

| At1g48600 | Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase | 13.9 | 5.6 | |

| At1g74720 | Phosphoribosylanthranilate transferase | 1.7 | 2.2 | |

| At1g16220 | Protein phosphatase 2C | 1.7 | 2.3 | |

| At5g51140 | Pseudouridylate synthase activity | 3.1 | 2.1 | |

| At2g40760 | Rhodanese-like protein | 2.3 | 2.0 | |

| At3g23580 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | 6.8 | 4.2 | |

| At2g17640 | Ser acetyltransferase | 2.6 | 3.6 | |

| At1g43710 | Ser decarboxylase | 9.0 | 2.0 | |

| At4g11640 | Ser racemase; Thr dehydratase | 1.7 | 1.9 | |

| At1g70560 | Similar to aliinase | 11.6 | 7.9 | |

| At5g51970 | Sorbitol dehydrogenase | 4.9 | 2.6 | |

| At3g14240 | Subtilisin-like Ser protease | 6.0 | 4.8 | |

| At5g05980 | Tetrahydrofolylpolyglutamate synthase | 3.6 | 1.9 | |

| At3g06730 | Thioredoxin | 1.6 | 2.0 | |

| At2g41680 | Thioredoxin reductase, putative | 1.9 | 2.4 | |

| At3g02660 | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

| At5g40870 | Uridine kinase | 3.7 | 3.0 | |

| Other | ||||

| At1g60860 | ARF GTPase-activating (GAP) protein | 2.6 | 2.3 | |

| At4g03100 | Rac GTPase-activating (GAP) protein | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| At2g23460 | Extra-large GTP binding protein | XLG1 | 2.7 | 1.9 |

| At3g53800 | Armadillo/β-catenin repeat family | 2.0 | 2.2 | |

| At4g33400 | Defective embryo and meristems (DEM)–like | 3.6 | 2.4 | |

| At1g72070 | DNAJ chaperone | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| At5g16650 | DNAJ chaperone | 2.7 | 2.3 | |

| At1g53140 | Dynamin | 2.9 | 2.0 | |

| At3g60190 | Dynamin | ADL4 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| At3g19720 | Dynamin | 2.4 | 1.6 | |

| At1g29980 | GPI-anchored protein | 14.3 | 9.8 | |

| At1g21880 | GPI-anchored protein | 5.6 | 2.7 | |

| At2g36730 | Pentatricopeptide (PPR) protein | 1.2 | 1.7 | |

| At2g23050 | Phototropic-responsive NPH3 family; phosphorelay | 12.6 | 10.7 | |

| At5g46420 | 16S rRNA processing protein | 2.0 | 1.8 | |

| At2g47250 | RNA helicase | 3.8 | 2.1 | |

| At3g26120 | RNA binding protein | 1.8 | 2.2 | |

| At5g23690 | Poly A polymerase–like | 1.6 | 1.8 | |

| At1g35610 | Putative electron transport activity | 1.7 | 2.2 | |

| At1g50240 | Armadillo/β-catenin repeat family | 2.5 | 2.0 | |

| At2g19430 | Transducin/WD-40 repeat family | 2.5 | 1.6 | |

| At5g15550 | Transducin/WD-40 repeat family | 5.3 | 2.3 | |

| At4g37110 | tRNA aminacylation; protein translation | 1.6 | 2.2 | |

| At3g46210 | tRNA nucleotidyl transferase; protein translation | 2.3 | 2.0 | |

| At1g13030 | tRNA splicing | 2.4 | 2.0 | |

| Unknown | ||||

| At1g08020 | Unknown | 1.5 | 2.2 | |

| At1g09450 | Unknown | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| At1g09980 | Unknown | 5.5 | 3.3 | |

| At1g17650 | Unknown | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| At1g21560 | Unknown | 1.9 | 2.1 | |

| At1g23370 | Unknown | 1.3 | 2.0 | |

| At1g29270 | Unknown | 4.6 | 8.0 | |

| At1g35612 | Unknown | 5.1 | 7.3 | |

| At1g48460 | Unknown | 2.3 | 2.1 | |

| At1g53460 | Unknown | 3.9 | 2.8 | |

| At1g61065 | Unknown | 1.8 | 1.6 | |

| At1g63260 | Unknown | 3.3 | 3.4 | |

| At1g67660 | Unknown | 1.5 | 1.8 | |

| At1g68080 | Unknown | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| At1g68220 | Unknown | 3.6 | 2.2 | |

| At1g68820 | Unknown | 2.9 | 2.8 | |

| At2g03280 | Unknown | 1.1 | 1.8 | |

| At2g03780 | Unknown | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| At2g25270 | Unknown | 2.3 | 2.2 | |

| At2g26200 | Unknown | 1.9 | 1.7 | |

| At2g32590 | Unknown | 2.2 | 2.2 | |

| At2g38370 | Unknown | 5.1 | 6.5 | |

| At2g39070 | Unknown | 1.9 | 1.7 | |

| At2g45830 | Unknown | 3.4 | 3.7 | |

| At3g01810 | Unknown | 5.2 | 3.4 | |

| At3g09000 | Unknown | 1.8 | 1.7 | |

| At3g15351 | Unknown | 2.7 | 2.2 | |

| At3g17680 | Unknown | 2.8 | 2.4 | |

| At3g22970 | Unknown | 4.3 | 2.8 | |

| At3g26750 | Unknown | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| At3g29185 | Unknown | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| At3g43240 | Unknown | 3.9 | 2.4 | |

| At3g43540 | Unknown | 1.4 | 2.0 | |

| At3g50190 | Unknown | 1.3 | 2.1 | |

| At3g50620 | Unknown | 1.7 | 2.0 | |

| At3g51290 | Unknown | 1.5 | 2.3 | |

| At3g53540 | Unknown | 1.7 | 2.3 | |

| At3g63090 | Unknown | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| At4g02790 | Unknown | 1.7 | 2.1 | |

| At4g13140 | Unknown | 1.7 | 1.9 | |

| At4g16620 | Unknown | 1.5 | 1.9 | |

| At4g18570 | Unknown | 3.9 | 3.3 | |

| At4g19400 | Unknown | 3.3 | 2.4 | |

| At4g22890 | Unknown | 1.9 | 2.0 | |

| At4g24750 | Unknown | 2.3 | 2.0 | |

| At4g25170 | Unknown | 1.9 | 2.8 | |

| At4g35910 | Unknown | 2.7 | 2.2 | |

| At5g02010 | Unknown | 2.3 | 2.6 | |

| At5g12080 | Unknown | 5.7 | 3.9 | |

| At5g15170 | Unknown | 1.7 | 1.9 | |

| At5g23780 | Unknown | 1.3 | 2.2 | |

| At5g27400 | Unknown | 3.5 | 2.5 | |

| At5g29771 | Unknown | 3.9 | 2.0 | |

| At5g37010 | Unknown | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| At5g41620 | Unknown | 4.6 | 6.2 | |

| At5g44650 | Unknown | 1.5 | 2.1 | |

| At5g47440 | Unknown | 6.6 | 9.1 | |

| At5g48960 | Unknown | 1.6 | 1.8 | |

| At5g51850 | Unknown | 2.1 | 4.4 | |

| At5g63040 | Unknown | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| At5g65685 | Unknown | 2.1 | 1.8 | |

| At5g66180 | Unknown | 2.5 | 2.3 | |

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative number.

Mean normalized expression of AGL42IV:GFP sort.

Average ratio of AGL42IV:GFP sort to five other root tissue sorts.

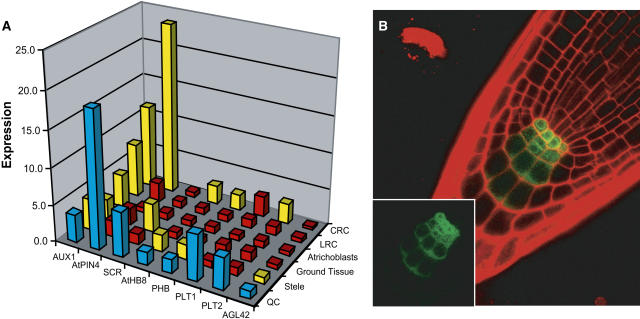

Several genes with known QC expression were found in the QC-enriched gene set, validating our approach (Figure 3A). The PLT1 and PLT2 genes were recently shown to play a key role in QC establishment and maintenance, and PLT1 expression is tightly restricted to the QC region (Aida et al., 2004). Genes expressed in QC plus other tissues, such as PIN-FORMED4 (AtPIN4), SCARECROW (SCR), PHABULOSA, and HOMEOBOX-LIKE8 (AtHB-8), were only enriched significantly over those tissues that lacked expression, confirming the accuracy of this method. AGL42 itself was not enriched over stele, presumably because of its low-level expression in the initials. By contrast, genes expressed ubiquitously in the meristem, such as AUX1, were not enriched significantly in the QC over any other tissue. These results strongly suggest that the transcriptional content of the QC is represented in the AGL42:GFP profile. Some genes with robust stele expression, such as WOODEN LEG and SHORT-ROOT (SHR), appeared with relatively high expression in the AGL42:GFP data, but, with the exception of AtPIN1, none was enriched significantly in the AGL42 sorted population over other tissues. This provides further evidence that a small fraction of the sorted cells were derived from stele cells proximal to the QC and likely explains why some factors involved in cell division, such as genes for cell expansion, nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis, and DNA polymerase subunits, were enriched in the sort data. A potential G1-associated cyclin, CYCD3:2 (Vandepoele et al., 2002), was enriched, in addition to the DNA replication licensing factor PROLIFERA that is present in dividing cells (Springer et al., 1995, 2000).

Figure 3.

Verification of the AGL42:GFP Transcriptional Profile.

(A) Digital in situ of genes with known QC expression. Normalized expression values are shown for the QC (blue) and other root tissues. Expression in the QC is either significantly enriched over other tissues (red) or not (yellow). CRC, columella root cap; LRC, lateral root cap. See text for gene abbreviations.

(B) Expression of a GFP fusion to the promoter of C2H2 basic domain/leucine zipper transcription factor AtWIP4 (At3g20880), predicted to be enriched in the QC. Note the strongest expression in the QC.

Promoters of QC-Enriched Genes Confer QC-Specific Expression

As a further test of the data and of our statistical approach, we cloned the promoters of seven putative transcription factors predicted to be enriched in the QC. We fused them to GFP and introduced the constructs into plants. Three of these lines exhibited expression in the QC as well as weaker expression in either stele and ground tissue or columella root cap (Figures 3B and 4A to 4C). One promoter region conferred expression in the columella initials (not represented in the PET111 sort) and the QC (Figure 4D). A fifth was found predominantly in the stele, and two did not give any expression. Together, these results support the validity of the QC transcriptional profile and the comparative approach for determining statistically significant enrichment.

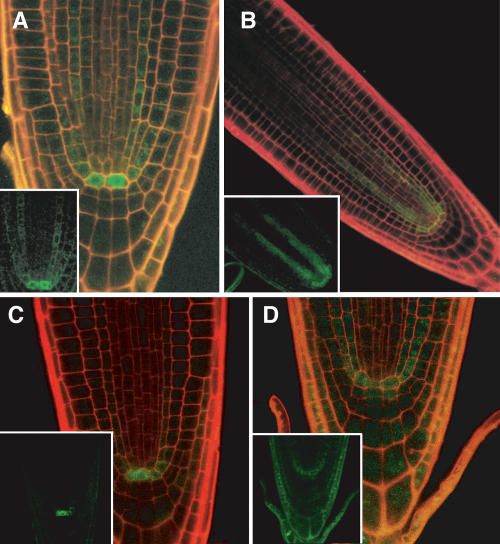

Figure 4.

Expression of Floral Regulators in the QC.

(A) and (B) NAP promoter fusion to GFP exhibits some stele expression and enrichment in the QC.

(C) PI promoter fusion to GFP has highest levels in the QC and young ground tissue.

(D) PAN promoter fusion to GFP has highest expression in the columella initials and QC.

Phytohormone-Related Features of the QC-Enriched Transcript Pool

Among the enriched genes, we detected several themes, including several indications that phytohormones play important roles in stem cell processes (Tables 1 and 2). Auxin signaling has been implicated in the maintenance of an apical-basal axis and is required for the production of distal cell types that make up the embryonic root (Hardtke and Berleth, 1998; Hamann et al., 2002). A local auxin maximum in the postembryonic QC and columella initials has also been correlated with distal patterning and QC fate (Sabatini et al., 1999). An auxin sink near the same location ensures that the maximum is maintained at a specific size (Friml et al., 2002). We detected two enriched transcripts, SUPERROOT1 (SUR1) and SUR2, which function as negative regulators of auxin biosynthesis (Boerjan et al., 1995; Barlier et al., 2000), suggesting that active inhibition of biosynthesis may be a mechanism for limiting auxin levels in parts of the root meristem.

In the presence of transported auxin, bioactive gibberellin (GA) has been shown to promote wild-type root growth by affecting cell expansion (Olszewski et al., 2002; Fu and Harberd, 2003). We identified ent-kaurene oxidases involved in the early steps of GA biosynthesis and confirmed QC enrichment of ent-kaurene synthetase A (GA1), previously shown to be expressed in the root tip (Silverstone et al., 1997). Localization of these enzymes in proximity to the auxin peak is consistent with the finding that GA biosynthesis is upregulated by auxin (Ross et al., 2000). These findings suggest the existence of a GA point source that is centered at the QC.

Brassinosteroids have been correlated with root growth through the analysis of biosynthetic and signaling mutants as well as exogenous hormone application (Mussig et al., 2003). We detected BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1-LIKE1 (BRL1), which has previously been shown by GUS reporter analysis to exhibit high levels in the QC as well as in the columella root cap and mature stele (Cano-Delgado et al., 2004). BRL1 was assigned a role in promoting xylem differentiation at the expense of phloem, but effects on meristem function or root growth have not been documented.

Absence of Phenotype in QC-Enriched Transcription Factor Mutants

To fulfill its critical function in the root meristem, the QC must be resistant to differentiation and able to undergo regenerative divisions to replace initials that have expired. It must also signal locally to inhibit the differentiation of surrounding cells (van den Berg et al., 1997), yet we do not have a good understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms that specify these properties. We reasoned that regulatory genes enriched in the QC might reveal roles in these processes when mutated. Therefore, we recovered and analyzed mutants for several transcription factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mutations Analyzed for QC-Enriched Transcription Factors

| Arabidopsis Genome Initiative No. | Class | Gene Name | Allele(s) | Position(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At1g21740 | bZIP | SALK_100864 | Exon 1 | |

| At1g25470 | AP2 | SALK_059502 | Exon 1 | |

| At1g68640 | bZIP | PERIANTHIA(PAN) | SALK_057190 | Exon 3 |

| At1g69490 | NAC | NAM-LIKE;ACTIVATED BY AP3/PI(NAP) | SALK_005010 | Exon 2 |

| At2g28550 | AP2 | RAP2.7 | SALK_069677 | Exon 6 |

| At2g41710 | AP2 | SALK_111105, SALK_151761 | Exon 6, intron 2 | |

| At3g20880 | Zinc finger (C2H2) | AtWIP4 | SALK_014672 | Exon 1 |

| At5g11510 | Myb (R2R3) | AtMYB3R4 | SALK_034806, SALK_059819 | 5′ UTR, exon 1 |

| At5g17800 | Myb (R2R3) | AtMYB56 | SAIL_587_D06, SALK_062413 | Exon 1, exon 2 |

| At5g20240 | MADS | PISTILLATA(PI) | pi-1 | |

| At5g28770 | bZIP | AtbZIP63 | SALK_006531 | Exon 1 |

To ensure that subtle phenotypes were not overlooked, one or two independent mutations in each gene were brought to homozygosity and assessed for differences in root growth on plates and for anatomical defects by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Three of the genes had previously characterized roles in the flower. PERIANTHIA (PAN) functions in regulating floral organ number (Running and Meyerowitz, 1996; Chuang and Meyerowitz, 2000). PISTILLATA (PI) is a floral homeotic MADS box gene that is required for the specification of petals and stamens (Bowman et al., 1989). In the flower, PI heterodimerizes with APETALA3 (AP3) to activate downstream targets, including NAC-LIKE;ACTIVATED BY AP3 (NAP). NAP is required for correct cell expansion in the petals and stamens (Sablowski and Meyerowitz, 1998). Interestingly, although both PI and its target were detected in the QC, the digital in situ of AP3 suggested that it is entirely absent from the root.

None of the mutations in this study gave a root phenotype under the conditions we tested. Therefore, we narrowed our analysis to a single gene, AGL42, to attempt some alternative approaches to determining gene function.

Manipulation of AGL42 Does Not Reveal a Role in the Root Meristem

To confirm the expression pattern of AGL42, we engineered a new marker that included the complete upstream intergenic sequence as well as mutated start codons (ATGs) in the MADS box (Figure 5A). These changes resulted in more specific but weaker expression in the QC using the GUS marker gene (Figure 5B). The lower level of expression was apparently insufficient to drive a nonenzymatic reporter, as the same regulatory sequences did not give rise to any fluorescence when fused to GFP (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Mutant Analysis and Expression of AGL42.

(A) Genomic region of AGL42, indicating positions of insertions (wedges) and point mutations (asterisks) for corresponding allele numbers. agl42-4 is a splice acceptor mutation for the third exon, and agl42-5 gives rise to a G113R substitution in the fourth exon. Below is a scheme of the complete promoter and intron, with exon 1 bearing mutated ATGs (small asterisks) driving the GUS reporter (construct IV).

(B) Whole-mount staining of construct IV at 7 d after germination showing tight QC expression.

(C) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR of AGL42 transcript in whole roots as ratios relative to wild-type Columbia (Col) root. RNAi, RNA interference; Ws, Wassilewskija.

Both the ET433 enhancer trap (agl42-1) and an independent insertion in the first intron (agl42-2) (Sussman et al., 2000) resulted in a reduction of mature AGL42 root RNA by one order of magnitude (Figure 5C). In addition to these, a series of insertion and point mutations (Figure 5A) were isolated and RNA interference was attempted (Figure 5C). No changes were detected in root anatomy in any of these or in the expression of the QC markers SCR:GFP (Wysocka-Diller et al., 2000) and AGL42:GFP in an agl42-1 background or of QC-46 (Sabatini et al., 1999) in an agl42-2 background (data not shown). Also, agl42-1 did not enhance the phenotypes of the scr-4 or shr-2 mutants, both of which have disorganized QCs and compromised meristems (data not shown).

Because AGL42 is a member of a large family of transcriptional regulators, one explanation for a lack of phenotype in agl42 mutants is that in the root its function is redundant. In an attempt to overcome the potential masking effects of redundancy, we used a gain-of-function approach. An insertion in the 5′ UTR (agl42-3) and experiments using AGL42 cDNA under the control of the 35S promoter resulted in 38- and 70-fold overexpression of root RNA, respectively (Figure 5C). However, neither of these gave rise to a phenotype. MADS box genes function as dimers, and AGL42 lacks a C-terminal Gln-rich region that has been associated with transcriptional activation in some other family members, such as AP1 and SEP3 (Honma and Goto, 2001). Reasoning that AGL42 may also require a partner to act as an activator or repressor, we constructed a series of AGL42 fusions to the VP16 strong activation domain (Cousens et al., 1989; Busch et al., 1999) and the EAR strong repression domain (Hiratsu et al., 2002, 2003). These were driven by AGL42 cis elements or the strong constitutive 35S promoter. Considering the possibility that the ectopic overexpressing lines became lethal or AGL42 was regulated at the level of nuclear localization, we constructed dexamethasone-inducible GR fusions of the AGL42-VP16 and AGL42-EAR cDNA with and without an exogenous nuclear localization signal. None of these lines gave rise to a root phenotype when grown on dexamethasone. Evidence that at least some of these constructs produced functional proteins comes from striking differences in flowering time in the 35S-AGL42-EAR construct and modest differences with the 35S-AGL42 construct compared with the wild type (data not shown). SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS1/AGL20 (SOC1) activity promotes flowering and is induced with similar kinetics to AGL42 during the floral transition (Schmid et al., 2003), suggesting a shared function in flowering for these two related genes.

The lack of phenotypes for AGL42 and other tested transcription factors suggests a degree of redundancy that may not be circumvented through gain-of-function approaches. Numerous examples of redundancy exist in the MADS box gene family, and all involve closely related genes with overlapping expression (Ferrándiz et al., 2000; Liljegren et al., 2000; Pelaz et al., 2000; Pinyopich et al., 2003; Ditta et al., 2004). None of the genes in the AGL42 clade, namely AGL14, AGL19, SOC1, AGL71, and AGL27 (Parenicova et al., 2003), showed tissue-specific expression in the root. However, other members of the family, including AGL16, AGL17, AGL18, and AGL21, are expressed at relatively high levels in the QC (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). As single mutants, agl19, soc1, agl71, and agl72 do not exhibit an obvious root phenotype, nor do the agl42-1 agl19-1 and agl42-1 soc1 double mutants (T. Nawy and P.N. Benfey, unpublished data). The time and difficulty of producing mutant combinations within such an extensive gene family invokes the need for detailed spatial information to guide further combinatorial genetic studies.

Analysis of Shoot Meristematic Genes in the Root

An important question is to what extent signaling pathways are shared between the root and shoot meristems. Both structures maintain a set of slowly cycling stem cell initials that occupy a niche formed by local signaling. In the shoot, the niche is defined by expression of the WUSCHEL (WUS) homeodomain transcription factor in a region below the stem cells known as the organizing center. WUS induces expression of the CLV3 ligand in the stem cells, and CLV3 signals through the CLV2 receptor and CLV1 receptor kinase to restrict WUS expression. The CLV1-like subfamily of Leu-rich repeat (LRR) receptor-like kinases includes 28 members (Torii, 2004). Although ectopic expression of CLV3 and CLV3-like ligands suggests that these genes function in the root (Casamitjana-Martinez et al., 2003; Hobe et al., 2003), attempts to knock out single or multiple receptor kinases have failed to produce any phenotypes. A possible reason for this emerges from analysis of the digital in situ: many members are either absent from the root or expressed in different tissue-specific domains (Figure 6A). Only At5g48940 is enriched specifically in the QC, but a handful of other receptor-like kinases show overlapping expression with the QC (e.g., At5g65700, At1g72180, At1g09970, At5g25930, and At1g73080). The most specific of these could serve as the starting point of a combinatorial genetic approach that incrementally incorporates related mutants with overlapping expression. This illustrates how the digital in situ can provide critical spatial expression data at the genomic level that can inform a multiple mutation approach.

Figure 6.

Digital in Situ of Shoot Stem Cell Signaling Genes.

CLV1 family of LRR receptor-like kinases. Normalized expression values are shown for the QC (blue) and other root tissues. Expression in the QC is either significantly enriched over other tissues (red) or not (yellow). CRC, columella root cap; LRC, lateral root cap.

Conclusion

Here, we applied a cell-sorting strategy to extract global transcriptional information from a rare and relatively inaccessible cell type in the plant. We surveyed a sample of QC-enriched transcription factor mutants, of which none exhibited a phenotype in the root. This may have been attributable to a number of reasons, including the fact that some alleles were not null and that expression was not independently confirmed for all of the genes. Also, although we used confocal laser scanning microscopy to detect potentially subtle phenotypes, some phenotypes may not have manifested themselves under our experimental conditions. However, most alleles harbored insertions in upstream exons that would be expected to completely abolish function, and four of five candidates tested by GFP reporter were enriched in the QC region, implying high accuracy of the QC profiling data. A more likely explanation involves a significant degree of functional redundancy in the root QC.

Genomic sequencing and the availability of large sequence-tagged mutant collections are powerful reverse genetic tools when combined with the ability to discern overlapping expression. We propose the use of the digital in situ to limit the mutant combinatorial space and to generate hypotheses about the nature of QC function, such as in relation to phytohormone activity. It is currently possible to cluster genes based on functional annotations (Beissbarth and Speed, 2004). In the future, as annotations become increasingly accurate, this may be a useful way of grouping genes to reveal functional redundancy in addition to expression data. With the set of genes enriched in the QC, it should be possible to screen for and discover at least some factors that are required to perform the unique functions of this stem cell population, which is so critical for plant development.

METHODS

Plant Growth and Transformation

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were surface-sterilized and grown as described by Benfey et al. (1993) except that the growth medium was prepared with 1.0% agar and supplemented with 1.0% sucrose. Plants were grown under long-day conditions (16 h light, 8 h dark). Transformation was performed on Columbia ecotype plants according to the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998).

Cloning of AGL42 and Isolation of Mutant Alleles

The ET433 enhancer trap was created as described by Malamy and Benfey (1997). Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR was performed on ET433 (agl42-1) genomic DNA to isolate flanking sequences (Liu et al., 1995).

To isolate agl42-2, collections at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (Sussman et al., 2000) were screened for left and right border T-DNA insertions using the primers 5′-ACTGGCTTGTTTAGGGTTTCAATCTTTAC-3′ and 5′-GGTTACAATAGAAAGCCAAAAGGGACTTA-3′ and confirmed by DNA gel blot analysis with AGL42 cDNA probe. agl42-3 corresponds to SALK_076684 isolated from a collection of sequence-indexed T-DNA insertion lines at the Salk Institute (Alonso et al., 2003). The agl42-4 and agl42-5 point mutants were recovered from the TILLING collection of ethyl methanesulfonate mutant lines at the University of Washington (Seattle) (McCallum et al., 2000). The agl42-8 allele is a sequence-indexed line from the GABI-Kat collection (Rosso et al., 2003) bearing an En-1 autonomous transposable element.

The pi-1 mutant was described previously (Bowman et al., 1989), and all other mutants were recovered from the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress) as insertions from the Salk collection or the Syngenta SAIL collection (Sessions et al., 2002). Seedling DNA was collected using the Extract-N-Amp plant PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Genotyping primers are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online. Primers with asterisks amplify the wild-type allele or the insertion allele in combination with a T-DNA primer: −46R, 5′-GCGTGTCCTCTCCAAATGAA-3′ (for agl42-1); JL202′, 5′-TATAATAACGCTGCGGACATCTAC-3′ (for agl42-2); LBb1′, 5′-GTGGACCGCTTGCTGCAACT-3′ (for all Salk insertions); GABI.8049, 5′-ATATTGACCATCATACTCATTGC-3′ (for agl42-8); and SAIL.LB1, 5′-TTCATAACCAATCTCGATACAC-3′ (for SAIL insertions). Both agl42-4 and agl42-5 primers amplify derived cleaved amplified product markers (MaeIII-digested agl42-4, 277 bp wild type and 220/57 bp mutant; BsmAI-digested agl42-5, 340 bp wild type and 150/190 bp mutant). The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative number for AGL42 is At5g62165.

Reporter Construction

For AGL42:GFP construct I, the 2.7-kb promoter and the 5′ UTR were amplified from Columbia genomic DNA using 5′FF (5′-CCCAAGCTTGGATCCCCCCTTCAAATAGGATATGCC-3′) and PromR (5′-GCTCTAGAGAATTCTTTTCTTGCTTTGACTTCATTTTTTCTGCCAC-3′) and cloned into pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as a HindIII/EcoRI fragment. This was removed with HindIII/SmaI for subcloning into the binary vector pBIN-GFP.Link, a pBIN19 derivative including a polylinker upstream of mGFP5-ER (Haseloff et al., 1997; Malamy and Benfey, 1997).

For AGL42:GFP construct II, the Int1F (5′-CCCAAGCTTGAATTCTAGCTCTGAGTATGTTTTCTTC-3′) and −46R primers were used to amplify from genomic DNA prepared from ET433 plants, ligated to pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and dropped into pBIN-GFP.Link as a HindIII/BamHI fragment.

For AGL42:GFP construct III, the MADS box and first intron were amplified from No-0 genomic DNA using Prom1F (5′-GTGGCAGAAAAAATCAAGTCAAAGC-3′) and Ex2R (5′-CATGCCATGGTCGTCTTCTGCATACTGATGATC-3′) primers and cloned into pAVA393 (von Arnim et al., 1998) containing a red-shifted GFP5 modified for N-terminal fusion (GenBank accession number AF078810). The 2.7-kb promoter, 5′ UTR, and MADS box were amplified using 5′FF and Int1R (5′-CTAGCTCTGAGTATGTTTTCTTC-3′) and inserted into the intron-bearing construct by EcoRV/EcoRI. The entire fragment containing promoter, UTR, first exon, first intron, and GFP5 was subcloned into pBIN19.

For AGL42:GUS construct IV, to introduce mutations into the six ATG sequences in the MADS box, two rounds of primer extension PCR were performed using two sets of long primers containing point mutations at ATG sites.

The MADS box to the start of the second exon was amplified with Ex1.KpnF′ (5′-AGCGGGATCCAAATTGGTACCAGGAAAGATAGAGACGAAGAAAATAG-3′) and Ex1.3′R (5′-CCTGGTACCAATTTTCTTGCTTTGACTTGATT-3′) and subcloned into pBluescript SK+ with a destroyed KpnI site using BamHI/XhoI. The full-length (3.4-kb) promoter was amplified using 5′Most (5′-ACGGGATCCAGTTATTCTTGCTTGTTTTTTGAG-3′) and Ex1.KpnR primers with high-fidelity Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes, Helsinki, Finland) from Columbia genomic DNA. Promoter was cloned into the intron-bearing construct with BamHI/KpnI and subcloned into modified pDONR P4-P1R containing BamHI/XhoI using those sites. This was used for Gateway-based (Invitrogen) cloning (see below).

The GUS gene was amplified from pRTL-GUS (Carrington and Freed, 1990) and recombined with pDONR 221 for subsequent Gateway cloning.

For promoter-GFP constructs, the primers listed in Supplemental Table 2 online were used to amplify promoters for transcriptional fusions to mGFP5-ER (Haseloff et al., 1997). Reporters were constructed by recombination into the pDONR P4-P1R vector and subsequent three-way Gateway recombination into a modified binary destination vector (J.-Y. Lee, J. Colinas, and P.N. Benfey, unpublished data) to fuse to mGFP5-ER.

Cloning of AGL42 Loss-of-Function and Gain-of-Function Variations

Constructions for AGL42 gain-of-function experiments were made using the Multisite Gateway three-fragment vector construction kit (Invitrogen) with a binary destination vector modified to include a NOS terminator and resistance to glufosinate ammonium. AGL42 cDNA was placed in pENTR format by amplifying and recombining with pDONR 221. The nuclear localization signal and the Myc tag were taken from pRTL2 (a gift of Detlef Weigel, Max Planck Institute, Tubingen, Germany) by NcoI digestion and ligated to the N terminus of a partial digestion of pENTR-AGL42, which contains two NcoI sites. We amplified the HSV-1 a-Trans inducing protein VP16 transactivation domain (amino acids 413 to 490; Cousens et al., 1989) from pTA700 (Aoyama and Chua, 1997) and recombined product with pDONR P2R-P3. For EAR, complementary sense (5′-GGGGACAGCTTTCTTGTACAAAGTGGGACTTGATTTGGATCTTGAGTTGAGACTTGGATTCGCTTAACAACTTTATTATACAAAGTTGTCCCC-3′) and antisense oligonucleotides were mixed and recombined directly into pDONR P2R-P3. The entire VP16:GR region of pTA700 was amplified and subsequently recombined with pDONR P2R-P3. The 35S promoter was taken from pBS-35S (Helariutta et al., 2000) and inserted into pDONR P4-P1R.

For RNA interference, the GUS spacer from pCRII-GUS (Chuang and Meyerowitz, 2000) was subcloned into pBluescript SK+ with destroyed EcoRI and EcoRV sites. AGL42 coding sequence lacking the MADS box was amplified from cloned cDNA (see above) using IKC.SenF (5′-AGCGGATATCCCAGCAATCACGACTCACA-3′) and IKC.SenR.NotI (5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCCCCAAATCATTACCTCACA-3′) for the sense orientation and IKC.AntF (5′-AGCGGAATTCCCAGCAATCACGACTCACA-3′) and IKC.AntR (5′-ACGCGGATCCCCCAAATCATTACCTCACA-3′) for the antisense orientation. Sense product was cloned into the pBluescript-GUS using EcoRV/NotI. Antisense product was inserted into this vector with EcoRI/BamHI. Both orientations and GUS spacer were cloned into the binary pCGN.

Microscopy

Histochemical staining for the GUS reaction was performed as described by Malamy and Benfey (1997), and roots were either cleared according to this protocol or as described by Liu and Meinke (1998). Light micrographs were taken using a Qimaging (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) Micropublisher 5.0 camera mounted on a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) DM/RXA2 microscope. Images were captured using Qcapture software by Qimaging.

For confocal laser scanning microscopy, seedling roots were stained in 10 mg/L propidium iodide for 2 to 5 min, rinsed, and mounted in water. Visualization was performed using a Zeiss LSM 510 system mounted on an Axioplan 2 microscope. After excitation by a Kr/Ar 488-nm laser line, propidium iodide was detected with a long-pass 560-nm filter and GFP was detected with a band-pass 505- to 550-nm filter.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA for quantitative PCR was extracted using the RNeasy plant extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) from root tissue of synchronized seedlings harvested at 7 d after germination. TaqMan reverse transcriptase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used to synthesize cDNA. Quantification was performed using the Roche LightCycler real-time thermocycler with a SYBR green probe. The clathrin gene was included in all reactions to control for RNA quantity. Primers used were as follows: Clathrin.F (5′-TGACGTTCACGATACCTAT-3′), Clathrin.R (5′-AGGTCATATCCTAGCCA-3′), madsboxF (5′-ATTGAAACAAGAAGCAAGCCA-3′), and madsboxR (5′-CATTCTTTTGATGTAACTTGACG-3′).

Cell Sorting and Microarray Analysis

AGL42:GFP and PET111 seedlings were grown, harvested, protoplasted, and sorted as described by Birnbaum et al. (2003). Briefly, ∼30,000 seeds were used to obtain 1000 to 2000 GFP-positive cells. The Affymetrix small sample labeling protocol VII was used to amplify mRNA from the GFP-positive cells. The biotin-labeled complementary RNA was hybridized to the Arabidopsis ATH1 GeneChip array (Affymetrix) by the Duke Microarray Core Facility and Expression Analysis (Durham, NC).

One of the AGL42:GFP sorts was from seedlings grown on nutrient agar medium supplemented with 4.5% sucrose, and the other was supplemented with 1% sucrose. To control for sucrose effects, we profiled whole roots grown on the two sucrose concentrations (three replicates each) without protoplasting and subjected the results to a mixed-model analysis (Chu et al., 2002). Significantly overrepresented or underrepresented genes (q < 0.001- and > 1.2-fold enriched in either 4.5 or 1% sucrose) are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online and were removed from the QC-enriched gene set (35 of 325 genes).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Renze Heidstra for making the PET111 line available and Mike Cook of the Comprehensive Cancer Facility at Duke University for expert assistance with cell sorting. Special thanks to Mitch Levesque and Jeremy Erickson for statistical support and to Ben Scheres, Renze Heidstra, and Kim Gallagher for critical reading of the manuscript. We also acknowledge Jee Jung, Joe Franklin, and Betty Kelley for valuable technical help. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant 0209754 and National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM-043778.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Philip N. Benfey (philip.benfey@duke.edu).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.105.031724.

References

- Aida, M., Beis, D., Heidstra, R., Willemsen, V., Blilou, I., Galinha, C., Nussaume, L., Noh, Y.S., Amasino, R., and Scheres, B. (2004). The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.M., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301, 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama, T., and Chua, N.H. (1997). A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 11, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlier, I., Kowalczyk, M., Marchant, A., Ljung, K., Bhalerao, R., Bennett, M., Sandberg, G., and Bellini, C. (2000). The SUR2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes the cytochrome P450 CYP83B1, a modulator of auxin homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14819–14824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissbarth, T., and Speed, T.P. (2004). GOstat: Find statistically overrepresented gene ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics 20, 1464–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfey, P.N., Linstead, P.J., Roberts, K., Schiefelbein, J.W., Hauser, M.T., and Aeschbacher, R.A. (1993). Root development in Arabidopsis: Four mutants with dramatically altered root morphogenesis. Development 119, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, K., Shasha, D.E., Wang, J.Y., Jung, J.W., Lambert, G.M., Galbraith, D.W., and Benfey, P.N. (2003). A gene expression map of the Arabidopsis root. Science 302, 1956–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan, W., Cervera, M.T., Delarue, M., Beeckman, T., Dewitte, W., Bellini, C., Caboche, M., Onckelen, H.V., Montagu, M.V., and Inze, D. (1995). superroot, a recessive mutation in Arabidopsis confers auxin overproduction. Plant Cell 7, 1405–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, J.L., Smyth, D.R., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1989). Genes directing flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1, 37–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, M.A., Bomblies, K., and Weigel, D. (1999). Activation of a floral homeotic gene in Arabidopsis. Science 285, 585–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Delgado, A., Yin, Y., Yu, C., Vafeados, D., Mora-Garcia, S., Cheng, J.-C., Nam, K.H., Li, J., and Chory, J. (2004). BRL1 and BRL3 are novel brassinosteroid receptors that function in vascular differentiation in Arabidopsis. Development 131, 5341–5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, J.C., and Freed, D.D. (1990). Cap-independent enhancement of translation by a plant potyvirus 5′ nontranslated region. J. Virol. 64, 1590–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana-Martinez, E., Hofhuis, H., Xu, J., Liu, C., Heidstra, R., and Scheres, B. (2003). Root-specific CLE19 overexpression and the sol1/2 suppressors implicate a CLV-like pathway in the control of Arabidopsis root meristem maintenance. Curr. Biol. 13, 1435–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.-M., Weir, B., and Wolfinger, R. (2002). A systematic statistical linear modeling approach to oligonucleotide array experiments. Math. Biosci. 176, 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, C., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (2000). Specific and heritable genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4985–4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousens, D.J., Greaves, R., Goding, C.R., and O'Hare, P. (1989). The C-terminal 79 amino acids of the herpes simplex virus regulatory protein, Vmw65, efficiently activate transcription in yeast and mammalian cells in chimeric DNA-binding proteins. EMBO J. 8, 2337–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyholos, M.K., and Sieburth, L.E. (2000). Separable whorl-specific expression and negative regulation by enhancer elements within the AGAMOUS second intron. Plant Cell 12, 1799–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditta, G., Pinyopich, A., Robles, P., Pelaz, S., and Yanofsky, M.F. (2004). The SEP4 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana functions in floral organ and meristem identity. Curr. Biol. 14, 1935–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, L., Janmaat, K., Willemsen, V., Linstead, P., Poethig, S., Roberts, K., and Scheres, B. (1993). Cellular organisation of the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Development 119, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrándiz, C., Gu, Q., Martienssen, R., and Yanofsky, M.F. (2000). Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture by FRUITFULL, APETALA1 and CAULIFLOWER. Development 127, 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J., Brand, U., Running, M., Simon, R., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283, 1911–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml, J., Benkova, E., Blilou, I., Wisniewska, J., Hamann, T., Ljung, K., Woody, S., Sandberg, G., Scheres, B., Jurgens, G., and Palme, K. (2002). AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 108, 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X., and Harberd, N.P. (2003). Auxin promotes Arabidopsis root growth by modulating gibberellin response. Nature 421, 740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, E., Tumbar, T., and Guasch, G. (2004). Socializing with the neighbors: Stem cells and their niche. Cell 116, 769–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, T., Benkova, E., Baurle, I., Kientz, M., and Jurgens, G. (2002). The Arabidopsis BODENLOS gene encodes an auxin response protein inhibiting MONOPTEROS-mediated embryo patterning. Genes Dev. 16, 1610–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke, C.S., and Berleth, T. (1998). The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 17, 1405–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseloff, J., Siemering, K.R., Prasher, D.C., and Hodge, S. (1997). Removal of a cryptic intron and subcellular localization of green fluorescent protein are required to mark transgenic Arabidopsis plants brightly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 2122–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helariutta, Y., Fukaki, H., Wysocka-Diller, J., Nakajima, K., Jung, J., Sena, G., Hauser, M., and Benfey, P. (2000). The SHORT-ROOT gene controls radial patterning of the Arabidopsis root through radial signaling. Cell 101, 555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu, K., Matsui, K., Koyama, T., and Ohme-Takagi, M. (2003). Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 34, 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu, K., Ohta, M., Matsui, K., and Ohme-Takagi, M. (2002). The SUPERMAN protein is an active repressor whose carboxy-terminal repression domain is required for the development of normal flowers. FEBS Lett. 514, 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobe, M., Muller, R., Grunewald, M., Brand, U., and Simon, R. (2003). Loss of CLE40, a protein functionally equivalent to the stem cell restricting signal CLV3, enhances root waving in Arabidopsis. Dev. Genes Evol. 213, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma, T., and Goto, K. (2001). Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 409, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S., Trotochaud, A.E., and Clark, S. (1999). The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell 11, 1925–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidner, C., Sundaresan, V., Roberts, K., and Dolan, L. (2000). Clonal analysis of the Arabidopsis root confirms that position, not lineage, determines cell fate. Planta 211, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljegren, S.J., Ditta, G.S., Eshed, Y., Savidge, B., Bowman, J.L., and Yanofsky, M.F. (2000). SHATTERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature 404, 766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.M., and Meinke, D.W. (1998). The titan mutants of Arabidopsis are disrupted in mitosis and cell cycle control during seed development. Plant J. 16, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-G., Mitsukawa, N., Oosumi, T., and Whittier, R.F. (1995). Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J. 8, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy, J.E., and Benfey, P.N. (1997). Analysis of SCARECROW expression using a rapid system for assessing transgene expression in Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 12, 957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, C.M., Comai, L., Greene, E.A., and Henikoff, S. (2000). Targeting Induced Local Lesions IN Genomes (TILLING) for plant functional genomics. Plant Physiol. 123, 439–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussig, C., Shin, G.-H., and Altmann, T. (2003). Brassinosteroids promote root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133, 1261–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, N., Sun, T.-p., and Gubler, F. (2002). Gibberellin signaling: Biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S61–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenicova, L., de Folter, S., Kieffer, M., Horner, D.S., Favalli, C., Busscher, J., Cook, H.E., Ingram, R.M., Kater, M.M., Davies, B., Angenent, G.C., and Colombo, L. (2003). Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: New openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 15, 1538–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz, S., Ditta, G.S., Baumann, E., Wisman, E., and Yanofsky, M.F. (2000). B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405, 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyopich, A., Ditta, G.S., Savidge, B., Liljegren, S.J., Baumann, E., Wisman, E., and Yanofsky, M.F. (2003). Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 424, 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.J., O'Neill, D.P., Smith, J.J., Kerckhoffs, L.H.J., and Elliott, R.C. (2000). Evidence that auxin promotes gibberellin A1 biosynthesis in pea. Plant J. 21, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, M.G., Li, Y., Strizhov, N., Reiss, B., Dekker, K., and Weisshaar, B. (2003). An Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutagenized population (GABI-Kat) for flanking sequence tag-based reverse genetics. Plant Mol. Biol. 53, 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running, M.P., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1996). Mutations in the PERIANTHIA gene of Arabidopsis specifically alter floral organ number and initiation pattern. Development 122, 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, S., Beis, D., Wolkenfelt, H., Murfett, J., Guilfoyle, T., Malamy, J., Benfey, P., Leyser, O., Bechtold, N., Weisbeek, P., and Scheres, B. (1999). An auxin-dependent distal organizer of pattern and polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Cell 99, 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, S., Heidstra, R., Wildwater, M., and Scheres, B. (2003). SCARECROW is involved in positioning the stem cell niche in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Genes Dev. 17, 354–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablowski, R.W., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1998). A homolog of NO APICAL MERISTEM is an immediate target of the floral homeotic genes APETALA3/PISTILLATA. Cell 92, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres, B., Wolkenfelt, H., Willemsen, V., Terlouw, M., Lawson, E., Dean, C., and Weisbeek, P. (1994). Embryonic origin of the Arabidopsis primary root and root meristem initials. Development 120, 2475–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, M., Uhlenhaut, N.H., Godard, F., Demar, M., Bressan, R., Weigel, D., and Lohmann, J.U. (2003). Dissection of floral induction pathways using global expression analysis. Development 130, 6001–6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions, A., et al. (2002). A high-throughput Arabidopsis reverse genetics system. Plant Cell 14, 2985–2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, L.E., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1997). Molecular dissection of the AGAMOUS control region shows that cis elements for spatial regulation are located intragenically. Plant Cell 9, 355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone, A.L., Chang, C.-w., Krol, E., and Sun, T.-p. (1997). Developmental regulation of the gibberellin biosynthetic gene GA1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 12, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling, A., Drummond-Barbosa, D., and Kai, T. (2001). Stem cells find their niche. Nature 414, 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, P.S., Holding, D.R., Groover, A., Yordan, C., and Martienssen, R.A. (2000). The essential Mcm7 protein PROLIFERA is localized to the nucleus of dividing cells during the G(1) phase and is required maternally for early Arabidopsis development. Development 127, 1815–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, P.S., McCombie, W.R., Sundaresan, V., and Martienssen, R.A. (1995). Gene trap tagging of PROLIFERA, an essential MCM2-3-5-like gene in Arabidopsis. Science 268, 877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey, J.D., and Tibshirani, R. (2003). Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9440–9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, M.R., Amasino, R.M., Young, J.C., Krysan, P.J., and Austin-Phillips, S. (2000). The Arabidopsis Knockout Facility at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Plant Physiol. 124, 1465–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii, K.U. (2004). Leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases in plants: Structure, function, and signal transduction pathways. Int. Rev. Cytol. 234, 1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud, A.E., Hau, T., Wu, G., Yang, Z., and Clark, S. (1999). The CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase requires CLAVATA3 for its assembly into a signaling complex that includes KAPP and a Rho-related protein. Plant Cell 11, 393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, C., Willemsen, V., Hendriks, G., Weisbeek, P., and Scheres, B. (1997). Short-range control of cell differentiation in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Nature 390, 287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele, K., Raes, J., De Veylder, L., Rouze, P., Rombauts, S., and Inze, D. (2002). Genome-wide analysis of core cell cycle genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14, 903–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim, A.G., Deng, X.W., and Stacey, M.G. (1998). Cloning vectors for the expression of green fluorescent protein fusion proteins in transgenic plants. Gene 221, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger, R.D., Gibson, G., Wolfinger, E.D., Bennett, L., Hamadeh, H., Bushel, P., Afshari, C., and Paules, R.S. (2001). Assessing gene significance from cDNA microarray expression data via mixed models. J. Comput. Biol. 8, 625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka-Diller, J., Helariutta, Y., Fukaki, H., Malamy, J., and Benfey, P. (2000). Molecular analysis of SCARECROW function reveals a radial patterning mechanism common to root and shoot. Development 127, 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.