Abstract

Background/Objectives: The red-wing fish (Distoechodon macrophthalmus), an endangered species native to Yunnan, is endemic to Chenghai Lake. The natural population of this species has suffered a sharp decline due to the invasion of alien fish species. Fortunately, the artificial domestication and reproduction of D. macrophthalmus have been successful and this species has become an economic species locally. However, there is still little research on D. macrophthalmus. Methods: In this study, a high-quality genome of D. macrophthalmus was assembled and annotated. The genome was sequenced and assembled using the PacBio platform and Hi-C method. Results: The genome size is 1.01 Gb and N50 is 37.99 Mb. The assembled contigs were anchored into 24 chromosomes. BUSCO analysis revealed that the genome assembly has 95.6% gene coverage completeness. A total of 455.62 Mb repeat sequences (48.50% of the assembled genome) and 30,424 protein-coding genes were identified in the genome. Conclusions: This study provides essential genomic data for further research on the evolution and conservation of D. macrophthalmus. Meanwhile, the high-quality genome assembly also provides insights into the genomic evolution of the genus Distoechodon.

Keywords: Distoechodon macrophthalmus, genome assembly, annotation, evolution

1. Introduction

D. macrophthalmus, belonging to the Actinopterygii class, Cypriniformes order, Cyprinidae family, and Distoechodon genus [1], is commonly known as the red-wing fish. This species is restrictedly distributed in Chenghai Lake, located in the central part of Yongsheng County, Lijiang City, Yunnan Province, China. Importantly, Peters established the genus Distoechodon (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) in 1881 with the type species D. tumirostris, and D. macrophthalmus was described as a distinct species in 2009 by Zhao et al. [1], which has the diagnostic characters of lateral line scales of 78–85 and the predorsal scales of 34–39. As a new species in the genus Distoechodon, D. macrophthalmus exhibits similarities to D. multispinnis, particularly in terms of having higher lateral line and predorsal scale counts, but has relatively bigger eyes that are easily distinguished. D. macrophthalmus is an omnivorous fish that mainly feeds on underwater humus, diatoms, filamentous algae, and debris of higher plants [2]. The abundant and diverse algae in Chenghai Lake provide rich food resources for D. macrophthalmus, and D. macrophthalmus plays an important role in the water purification of Chenghai Lake, which has great industrial and ecological value.

D. macrophthalmus was one of the main indigenous economic fishes in Chenghai Lake, ever accounting for up to 30% of Chenghai’s fishing yield before the 1990s [3]. The shift in agricultural production methods around the lake and the rapid growth of spirulina culture in the lakeside area accelerated the eutrophication of Chenghai Lake, leading to an algal bloom outbreak in winter [4]. Additionally, the invasion of non-native fish species posed serious threats to the indigenous fish species in Chenghai Lake. Invasive species miniaturize the zooplankton community, resulting in the massive reproduction of algae and affecting the water quality. The number of indigenous fish species decreased from fifteen (six endemic) to ten, and the production of indigenous fish decreased sharply [5]. In 2004, no adult specimen of D. macrophthalmus was detected in Chenghai Lake and it was inferred that the primary threat stemmed from the introduction of icefishes (Family Salangidae) [1,6]. Impact factors such as overfishing of D. macrophthalmus and the invasion of Salangid fish have led to a sharp decline in the yield of D. macrophthalmus, accounting for less than 0.2% of the production of Chenghai fisheries [3]. Therefore, the artificial domestication and breeding of this fish have been in progress since 2004. At present, the population of D. macrophthalmus has recovered with the success of artificial breeding and release. Nowadays, over 1.2 million fries of D. macrophthalmus have been released into Chenghai Lake, greatly alleviating its population resources, protecting the aquatic biodiversity of Chenghai Lake, and promoting the sustainable development of fisheries.

The evolutionary status of Distoechodon is still ambiguous and confusing, especially when compared to the most similar genus, Xenocypris. In 2021, Liu et al. [7] sequenced the complete mitochondrial genome of Xenocypris fangi and found that X. fangi was closely related to D. tumirostris. In 2022, Zhang et al. [2] compared all the mitochondrial genomes of the Xenocypris subfamily and found that the genetic distance between Distoechodon and Xenocypris is very short. In 2023, Li et al. [8] evaluated the phylogenetic relationship and differentiation time of Xenocyprinae species based on two mitochondrial genes and five nuclear gene sequences and further distinguished different genera. At present, the extant scholarly literature pertaining to D. macrophthalmus is notably scarce, with a significant proportion of the available data being derived from reports issued by local governmental authorities within China. In addition, there are no available genomes of D. macrophthalmus that have been reported. Therefore, a high-quality reference genome and annotation of D. macrophthalmus is essential to reveal the phylogenetic relationships and the unique evolutionary characteristics of the genus Distoechodon. This study is the first genome report of D. macrophthalmus and offers crucial genomic resources and new perspectives for further genetic breeding and conservation studies on Distoechodon.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

A female individual of D. macrophthalmus was collected from Chenghai Lake, Yunnan province (Figure 1A) and the blood tissue was sampled for DNA sequencing. High-quality genomic DNA was extracted by the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Shanghai, China) and the DNA quality and quantity were examined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, respectively. Total RNA was extracted from five tissues of the specimen, including muscle, liver, brain, blood, and kidney, using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). RNA purity and integrity were monitored by a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, California, USA). Ethics Committee: Animal experimental ethical inspection of laboratory animal center, Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Approval code: YFI2021ZXY06; Approval date: 5 December 2021).

Figure 1.

Overview of the D. macrophthalmus. (A) D. macrophthalmus in dorsal view; (B) Hi-C interactive heatmap of genome-wide D. macrophthalmus. The depth of red color shows the contact density. A square represents a chromosome and the number represents the chromosome ID; (C) Circos of D. macrophthalmus genome characteristics. From outside to inside: gene density; transposon density; repeat elements; distribution of GC; self-collinearity of genes.

2.2. Genome Sequencing and RNA-seq

An SMRTbell library was constructed using the SMRT Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, California, USA) for sequencing on a PacBio Sequel II system by Frasergen Bioinformatics Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). High-quality Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) reads were obtained by using the CCS program [9] for preprocessing. The DNA sample extracted from blood tissue was used for the construction of the Hi-C library with a 4-cutter restriction enzyme MboI. The Hi-C library was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq X platform with 150 bp paired-end mode. An RNA sequencing library was constructed from a pooled sample with the equal amount of RNA extracted from the muscle, liver, brain, blood, and kidney. The full-length cDNA was prepared using a SMARTer™ PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit [10] (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Subsequently, SMRT sequencing was performed on a PacBio Sequel II platform.

2.3. Genome Assembly and Hi-C Scaffolding

Initially, jellyfish [11] was used to calculate the k-mer frequency and GCE [12] was used to estimate genome size, heterozygosity, and repetitive sequences. The CCS software v6.4.0 was used to generate the consensus reads (HiFi reads) with the parameter ‘-minPasses 3’. Subsequently, Hifiasm [13] was used to assemble these HiFi reads preliminarily. To identify the association between different contigs, the clean reads generated from the Hi-C library were mapped to the assembled contigs using Juicer [14] with the default parameters. Self-ligation, non-ligation, and other invalid reads were filtered using the Hicup software v0.8.2 [15]. Finally, error correction of the assembly generated by 3d-DNA [16] was performed using the juicebox [17] program to obtain the final chromosome-level genome. In order to assess the integrity of the assembly, the HiFi reads were realigned to the final assembly utilizing minimap2 v2.5 [18], employing the default parameters. To assess the completeness of the genome assembly, a quantitative evaluation was performed using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v3.1 [19] with the actinopterygii_odb9 geneset. We evaluated the mapping rate by mapping the PacBio and Illumina sequencing reads to the assembly using bowtie2 [20] and minimap2. The short reads were k-merized using jellyfish (k-mer = 21) and then the k-mer completeness scores were estimated using Merqury v1.3 [21].

2.4. Repeat and Protein-Coding Gene Annotation

The Tandem Repeats Finder v4.09 (TRF) [22] was utilized to predict the tandem repeats in the genome. The identification of repeat contents was achieved through the integration of homology-based predictions and de novo predictions. The known transposable elements (TEs) were identified using RepeatMasker v4.0.9 [23] with the Repbase TE library. Meanwhile, RepeatModeler [24] was used to construct a de novo repeat library. Additionally, we conducted a de novo investigation of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons within the genomic sequences of D. macrophthalmus using LTR_FINDER v1.0.7 [25], LTR_harvest v1.5.11 [26], and LTR_retriever v2.7 [27]. Ultimately, we integrated the library files from both methodologies and employed RepeatMasker v4.0.7 to analyze the repetitive elements present in the data. We predicted the protein-coding genes using three approaches, including ab initio gene prediction, homology-based gene prediction, and RNA-Seq-guided gene prediction. Augustus v3.3.3 [28] and GeneScan were used to perform the ab initio gene prediction. Gene models were developed utilizing a collection of high-quality proteins derived from the RNA-Seq dataset. Maker v2.31.10 [29] was used to conduct the homology-based gene prediction. The homology protein sequences obtained from five closely related species (i.e., Danio rerio, Ctenopharyngodon idella, Megalobrama amblycephala, Triplophysa tibetana, and Colossoma macropomum) were aligned to the genome assembly. Additionally, the transcripts were obtained from PacBio SMRT reads using the ISO-Seq pipeline [30] and aligned to the genome using PASA [31]. Finally, EVidenceModeler (EVM) v1.1.1 [32] was used to integrate the predictions to obtain the final gene models.

The functional annotations were performed with the public databases, including the non-redundant protein database (NR), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, euKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG), Gene Ontology (GO), and Pfam databases, using diamond v0.9.30.131 [33] blastp with the parameters “–outfmt 6 –max-target-seqs 1 –evalue 1 × 10−6”. Additionally, special functional databases such as the Comprehensive Antibiotic Research Database (CARD), Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy), Phibase (PHI), and Virulence Factors Database (VFDB) were used to functionally annotate the proteins. Annotations of noncoding RNA, including tRNA, rRNA, miRNA, and snRNA, were also performed. We used tRNAscan-SE v1.3.1 [34] to identify the tRNA; we identified rRNAs using RNammer v1.2 [35] with the parameters “-S euk -m lsu, ssu, tsu”. MicroRNAs and snRNAs were identified by CMSCAN [36] v1.1.2 software against the Rfam v14.0 [37] database with default parameters.

2.5. Gene Family and Evolutionary Analysis of D. macrophthalmus

To delineate gene families derived from protein-coding genes, protein sequences from D. macrophthalmus and 40 other closely related species were collected. The identification of gene families was performed using OrthoFinder v2.0 [38]. A phylogenetic tree of D. macrophthalmus and the 40 other fish species was constructed using the MUSCLE v3.8.31 [39] program and RAxML v8.2.11 [40]. We used CAFÉ v3.1 [41] to analyze gene family expansion and contraction.

To investigate the chromosome evolution of D. macrophthalmus and D. rerio (Zebrafish), a genome alignment between the D. macrophthalmus and Zebrafish genomes was generated using LASTZ v1.1 [42] with the parameter settings “T = 2 C = 2 H = 2000 Y = 3400 L = 6000 K = 2200”. Following the exclusion of aligned blocks shorter than 2 kilobases, the syntenic relationships between the two genomes were illustrated using Circos v0.69-6 [43].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

The genome size estimated by GCE was 957.64 Mb, the heterozygosity was 0.4%, and the repeat sequence content was 38%. A total of 1,888,999 high-quality ccs reads and 35.36 Gb HiFi bases were generated by PacBio Sequel II systematic sequencing and the N50 was 18,854 bp in length. The ccs reads were assembled into primary contigs using hifiasm, yielding 89 contigs. The genome assembly of D. macrophthalmus is 1.01 Gb in size with an N50 length of 36.05 Mb. A total of 95.09 Gb of Hi-C data, corresponding to approximately 99× coverage, was generated using the MGI-seq platform and utilized for the assembly at the chromosome level. Following the quality control assessment of Hi-C reads conducted with Hicup software v0.8.2, the effective data yield was determined to be 28.14% (27.9 Gb, ~28X coverage depth). The assembled chromosome-level genomes contain 29 contigs and 62 scaffolds. Utilizing Hi-C data, a total of 29 contigs were successfully anchored to 24 chromosomes, resulting in an aggregate length of 939.42 Mb. The lengths of the anchored chromosomes varied, ranging from 29.29 Mb to 55.47 Mb (Table 1). Subsequently, the assembled genomes were subjected to BUSCO with the actinopterygii database to evaluate the completeness of the genome. Using the 4584 direct homologous single-copy gene database constructed by BUSCOs as a reference, the assembly of D. macrophthalmus included 4385 (95.6%) complete BUSCOs, of which 4228 (92.2%) were complete single-copy BUSCOs and 157 (3.4%) were completely duplicated BUSCOs. The mapping rate of PacBio long reads to the assembly was 99.38% and the mapping rate of short reads to the assembly was 99.86%. The k-mer based QV (quality value) was 59.24. These results indicate a high quality of genome assembly in this study (Figure 1B,C).

Table 1.

Summary of chromosome length of D. macrophthalmus genome.

| Pseudo-Chromosomes | Length (bp) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Chr01 | 55,467,930 | 5.50% |

| Chr02 | 52,268,502 | 5.19% |

| Chr03 | 52,175,653 | 5.18% |

| Chr04 | 50,776,516 | 5.04% |

| Chr05 | 47,134,997 | 4.68% |

| Chr06 | 45,016,773 | 4.47% |

| Chr07 | 42,254,842 | 4.19% |

| Chr08 | 39,626,809 | 3.93% |

| Chr09 | 39,485,572 | 3.92% |

| Chr10 | 39,347,628 | 3.90% |

| Chr11 | 37,993,288 | 3.77% |

| Chr12 | 37,680,446 | 3.74% |

| Chr13 | 36,358,430 | 3.61% |

| Chr14 | 36,223,197 | 3.59% |

| Chr15 | 36,052,844 | 3.58% |

| Chr16 | 35,777,427 | 3.55% |

| Chr17 | 35,622,143 | 3.54% |

| Chr18 | 34,144,175 | 3.39% |

| Chr19 | 33,406,070 | 3.32% |

| Chr20 | 32,652,807 | 3.24% |

| Chr21 | 32,218,678 | 3.20% |

| Chr22 | 30,659,034 | 3.04% |

| Chr23 | 29,287,022 | 2.91% |

| Chr24 | 27,792,149 | 2.76% |

| Unmapped | 68,215,872 | 6.77% |

| Total | 1,007,638,804 | 100.00% |

3.2. Genome Annotation

A total of 455.62 Mb tandem repeat sequences were predicted, accounting for approximately 48.50% of the genome. Among them, long terminal repeats (LTRs) accounted for 3.32%, DNA transposons accounted for 3.25%, and long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) accounted for 1.81%. Subsequently, we predicted 30,424 protein-coding genes in D. macrophthalmus genome. The average length of the protein-coding genes was 14,272 bp, with a GC content of 50.4%, and the completeness of the predicted protein-coding genes as assessed by BUSCO was 91.6%. A total of 30,376 genes (99% of all predicted genes) were annotated by the seven known databases (Table 2). Additionally, special functional databases such as the Comprehensive Antibiotic Research Database (CARD), Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy), Phibase (PHI), and Virulence Factors Database (VFDB) were used to functionally annotate the proteins and 2168 genes were successfully annotated. Meanwhile, a total of 604 rRNAs, 346 snRNAs, 14,422 tRNAs, and 21 snoRNAs were identified in the genome (Table 3).

Table 2.

Number of genes annotated using different databases.

| Database | Number of Annotated Genes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| GO | 14,606 | 48% |

| kEGG | 13,416 | 44% |

| KOG | 17,520 | 57% |

| NR | 30,229 | 99% |

| Pfam | 22,982 | 75% |

| swiss_prot | 23,051 | 75% |

| TrEMBL | 29,350 | 96% |

| Total | 30,376 | 99% |

Table 3.

Number of the annotated non-coding RNA.

| Type | Number | Total Length | Average Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rRNA | 18s_rRNA | 22 | 41,761 | 1898.23 |

| 28s_rRNA | 21 | 109,601 | 5219.10 | |

| 5.8S_rRNA | 24 | 3672 | 153.00 | |

| 5S_rRNA | 537 | 62,757 | 116.87 | |

| tRNA | 14,422 | 1,071,936 | 74.00 | |

| snRNA | 346 | 54,608 | 157.83 | |

| snoRNA | 21 | 2707 | 128.90 |

3.3. Evolutionary Analysis of D. macrophthalmus

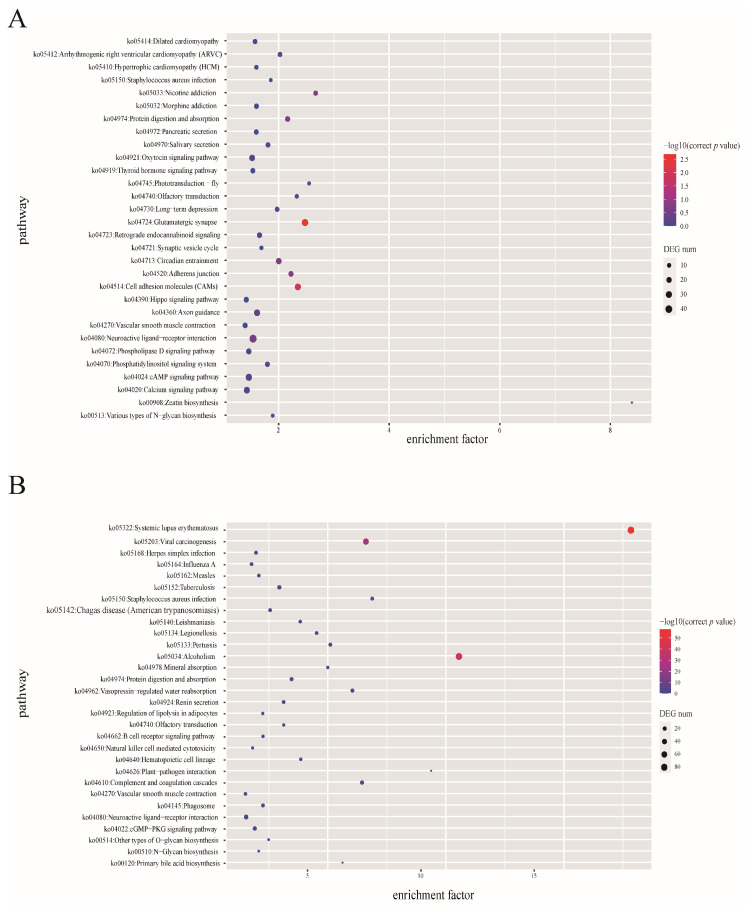

Based on the protein sequences of D. macrophthalmus and 40 other fish species, a total of 1,583,574 gene families were identified from the 41 fish species, of which 2568 genes were shared by the selected species, representing ancestral gene families (Figure 2). Importantly, 3355 gene families were unique to the D. macrophthalmus genome. KEGG enrichment analysis of D. macrophthalmus-specific genes showed that the specific genes were significantly enriched in environmental information processing, cellular processes, and organismal systems (Figure 3A). The phylogenetic tree showed that D. macrophthalmus was grouped with the species in families of Ctenopharyngodon and Megalobrama, indicating a closer relationship with these species. C. idella and D. macrophthalmus share a common ancestor and the divergence of these two species is at around 32.51 MYA; the divergence time between the first two and M. amblycephala was estimated to be 37.46 MYA before (Figure 3B). A prior investigation presents genetic evidence indicating that the divergence of the Xenocypris species from the Distoechodon and Pseudobrama species occurred approximately 10 MYA [2], as determined through mitochondrial gene analysis. The significant divergence among Xenocyprinae species is likely to have transpired during the Middle to Late Miocene and Late Pliocene epochs, implying that the processes of speciation and diversification may be linked to the climatic influences of the Asian monsoon.

Figure 2.

Comparative genomic analysis reveals phylogenetic positioning and genome evolution of D. macrophthalmus. (A) Statistics of orthologous gene families in 41 representative fish species; (B) Phylogenetic tree and estimated divergence time of D. macrophthalmus and other representative species, where D. macrophthalmus is represented in red font. Statistical analysis of contraction and expansion of gene families.

Figure 3.

KEGG enrichment analysis of gene families. (A) Enrichment analysis of D. macrophthalmus specific gene families; (B) enrichment analysis of D. macrophthalmus expansion gene family.

The expansion or contraction of gene families plays a key role in driving the adaptive evolution of D. macrophthalmus. In comparison with gene families of C. idella, gene families significantly expanded and contraction increased by 258 and 72, respectively. KEGG enrichment analysis of the expanded gene families demonstrates that they were mainly assigned to “signal transduction”, “signaling molecules and interaction”, “transport and catabolism”, “immune system”, “endocrine system”, “digestive system”, and “sensory system” (Figure 3B). The results of the KEGG enrichment analysis on gene family expansion showed that the expansion gene family enriched in the hematopoietic cell lineage of D. macrophthalmus is consistent with the lifestyle of D. macrophthalmus living in turbulent rivers in the high-altitude area of Chenghai Lake. Genes related to olfactory perception can increase D. macrophthalmus’s adaptability to environmental changes. Therefore, genes related to olfactory translation are significantly expressed in both D. macrophthalmus’s unique genes and the expansion gene families.

3.4. Synteny of D. macrophthalmus and Zebrafish Genome

In order to conduct a more comprehensive assessment of the quality of genome assembly, the synteny of the D. macrophthalmus genome (n = 24) with the zebrafish genome (n = 25) was investigated. Figure 4 illustrates the gene synteny between the genomes of D. macrophthalmus and zebrafish. The chromosomes of D. macrophthalmus demonstrated a significant degree of homology with those of the zebrafish, with one chromosome corresponding to zebrafish chromosomes 22 and 10. This indicates that zebrafish possess 25 pairs of chromosomes, whereas D. macrophthalmus is characterized by having only 24 pairs of chromosomes. This observation aligns with earlier findings related to grass carp and blunt snout bream [44]. This research provides additional evidence that East Asian cyprinids may exhibit a chromosomal configuration consisting of only 24 pairs, a condition attributed to the fusion of two ancestral chromosomes [45,46]. Research on Drosophila species indicates that chromosome fusion may significantly contribute to adaptive evolution and speciation [47,48,49]. This process can result in reproductive isolation among species, thereby facilitating the emergence of new species.

Figure 4.

Circos diagram of chromosome synteny between D. macrophthalmus and D. rerio. Each colored line represents a gene model match between the two species.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, we have constructed a chromosomal-level genome assembly of D. macrophthalmus, which provides a reference for genomic studies of D. macrophthalmus in the future. We revealed that a common chromosome fusion event happened in the ancestral East Asian cyprinid. Additionally, the systematic phylogenetic relationships of the East Asian cyprinid were reconstructed, which contributed to a better understanding of the confusing taxonomic relations of the East Asian cyprinid. The expanded gene families characterized an adaptive evolution that could explain the restricted distribution of D. macrophthalmus. These genomic data serve as a significant resource for advancing research on economically important Xenocyprinae fish species, particularly in the areas of evolution, conservation, and aquaculture breeding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. (Xiangyun Zhu), Q.S. (Qiang Sheng) and J.W.; Data curation, Q.S. (Qi Shen) and X.Z. (Xingyu Zheng); Formal analysis, M.X.; Funding acquisition, X.Z. (Xiangyun Zhu); Investigation, Y.L.; Methodology, Q.S. (Qiang Sheng); Project administration, J.W.; Resources, X.Z. (Xiangyun Zhu); Software, B.M.; Supervision, Q.S. (Qiang Sheng); Validation, Y.L.; Writing–original draft, X.Z. (Xiangyun Zhu); Writing–review and editing, Q.S. (Qiang Sheng) and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal experimental ethical inspection of laboratory animal center, Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Approval code: YFI2021ZXY06; Approval date: 5 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The final genome assembly has been deposited into the Genome Warehouse (GWH) of National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) with the accession number GWHEUUS00000000.1. The Hi-C (SRR28352443), Iso-seq (SRR28352442), and HiFi (SRR28352444) reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under BioProject number PRJNA1084914. The genome annotation files have been saved in figshare with the accession number 10.6084/m9.figshare.26310445.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the funding of “Selection of sex-specific molecular markers using chromosomal characteristics in the Parachromis managuensis and new variety breeding” (202401AT070091).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Zhao Y., Kullander F., Kullander S.O., Zhang C. A Review of the Genus Distoechodon (Teleostei: Cyprinidae), and Description of a New Species. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2009;86:31–44. doi: 10.1007/s10641-008-9421-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Z., Li J., Zhang X., Lin B., Chen J. Comparative Mitogenomes Provide New Insights into Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Subfamily Xenocyprinae (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) Front. Genet. 2022;13:966633. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.966633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao X., Liu C., Huang B., Yang Q., Yang L., Chen H., Xing R., Hong L. Key Points of Artificial Reproduction Technology in Distoechodon Macrophthalmus. OJFR. 2020;7:129. doi: 10.12677/OJFR.2020.73018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zan F., Huo S., Xi B., Zhang J., Liao H., Wang Y., Yeager K.M. A 60-Year Sedimentary Record of Natural and Anthropogenic Impacts on Lake Chenghai, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2012;24:602–609. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(11)60784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y., He S., Peng J., Huang F., Huo X., Tu H., Cai Y., Huang X., Sun J. Mobile Generalist Species Dominate the Food Web Succession in a Closed Ecological System, Chenghai Lake, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022;36:e02122. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge Y., Gu X., Zeng Q., Mao Z., Chen H., Yang H. Risk Screening of Non-Native Freshwater Fishes in Yunnan Province, China. Manag. Biol. Invasions. 2024;15:73–90. doi: 10.3391/mbi.2024.15.1.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nannan L., Haoran G., Xinkai C., Yuanfu W., Zhijian W. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of Xenocypris Fangi. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 2021;6:1200–1201. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1903361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L., Chen W.T., Tang Y.T., Zhou C.J., He S.P., Feng C.G. Molecular Systematics of Xenocyprinae (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae) Acta Hydr. Sin. 2023;47:628–636. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travers K.J., Chin C.-S., Rank D.R., Eid J.S., Turner S.W. A Flexible and Efficient Template Format for Circular Consensus Sequencing and SNP Detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villalva C., Touriol C., Seurat P., Trempat P., Delsol G., Brousset P. Increased Yield of PCR Products by Addition of T4 Gene 32 Protein to the SMARTTM PCR cDNA Synthesis System. BioTechniques. 2001;31:81–86. doi: 10.2144/01311st04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marçais G., Kingsford C. A Fast, Lock-Free Approach for Efficient Parallel Counting of Occurrences of k-Mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B., Shi Y., Yuan J., Hu X., Zhang H., Li N., Li Z., Chen Y., Mu D., Fan W. Estimation of Genomic Characteristics by Analyzing k-Mer Frequency in de Novo Genome Projects. arXiv. 20131308.2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H., Concepcion G.T., Feng X., Zhang H., Li H. Haplotype-Resolved de Novo Assembly Using Phased Assembly Graphs with Hifiasm. Nat. Methods. 2021;18:170–175. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand N.C., Shamim M.S., Machol I., Rao S.S.P., Huntley M.H., Lander E.S., Aiden E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingett S.W., Ewels P., Furlan-Magaril M., Nagano T., Schoenfelder S., Fraser P., Andrews S. HiCUP: Pipeline for Mapping and Processing Hi-C Data. F1000Research. 2015;4:1310. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7334.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y., Xiong Y., Xiao Y. 3dDNA: A Computational Method of Building DNA 3D Structures. Molecules. 2022;27:5936. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson J.T., Turner D., Durand N.C., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Mesirov J.P., Aiden E.L. Juicebox.Js Provides a Cloud-Based Visualization System for Hi-C Data. Cell Syst. 2018;6:256–258.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadasivan H., Maric M., Dawson E., Iyer V., Israeli J., Narayanasamy S. Accelerating Minimap2 for Accurate Long Read Alignment on GPUs. J. Biotechnol. Biomed. 2023;6:13. doi: 10.26502/jbb.2642-91280067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simão F.A., Waterhouse R.M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E.V., Zdobnov E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness with Single-Copy Orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhie A., Walenz B.P., Koren S., Phillippy A.M. Merqury: Reference-Free Quality, Completeness, and Phasing Assessment for Genome Assemblies. Genome Biol. 2020;21:245. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benson G. Tandem Repeats Finder: A Program to Analyze DNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarailo-Graovac M., Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to Identify Repetitive Elements in Genomic Sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2009;25:4–10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flynn J.M., Hubley R., Goubert C., Rosen J., Clark A.G., Feschotte C., Smit A.F. RepeatModeler2 for Automated Genomic Discovery of Transposable Element Families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Z., Wang H. LTR_FINDER: An Efficient Tool for the Prediction of Full-Length LTR Retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David E., Stefan K., Ute W. LTRharvest, an Efficient and Flexible Software for de Novo Detection of LTR Retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou S., Jiang N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brůna T., Li H., Guhlin J., Honsel D., Herbold S., Stanke M., Nenasheva N., Ebel M., Gabriel L., Hoff K.J. Galba: Genome Annotation with Miniprot and AUGUSTUS. BMC Bioinform. 2023;24:327. doi: 10.1186/s12859-023-05449-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson H., Mark Y. MAKER2: An Annotation Pipeline and Genome-Database Management Tool for Second-Generation Genome Projects. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin Z., Lv X., Sun Y., Fan Z., Xiang G., Yao Y. Comprehensive Discovery of Salt-Responsive Alternative Splicing Events Based on Iso-Seq and RNA-Seq in Grapevine Roots. EEB. 2021;192:104645. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia H., Wei H., Zhu D., Ma J., Yang H., Wang R., Feng X. PASA: Identifying More Credible Structural Variants of Hedou12. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2019;17:1493–1503. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2019.2934463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas B.J., Salzberg S.L., Zhu W., Pertea M., Allen J.E., Orvis J., White O., Buell C.R., Wortman J.R. Automated Eukaryotic Gene Structure Annotation Using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchfink B., Xie C., Huson D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan P.P., Lowe T.M. tRNAscan-SE: Searching for tRNA Genes in Genomic Sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1962:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rødland E.A., Stærfeldt H.H., Rognes T., Ussery D.W. RNAmmer: Consistent and Rapid Annotation of Ribosomal RNA Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawrocki E.P., Eddy S.R. Infernal 1.1: 100-Fold Faster RNA Homology Searches. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2933–2935. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sellés Vidal L., Ayala R., Stan G.-B., Ledesma-Amaro R. rfaRm: An R Client-Side Interface to Facilitate the Analysis of the Rfam Database of RNA Families. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0245280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emms D.M., Kelly S. OrthoFinder: Solving Fundamental Biases in Whole Genome Comparisons Dramatically Improves Orthogroup Inference Accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamatakis A. RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han M.V., Thomas G.W.C., Lugo-Martinez J., Hahn M.W. Estimating Gene Gain and Loss Rates in the Presence of Error in Genome Assembly and Annotation Using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1987–1997. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris R.S. Ph.D. Thesis. Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA, USA: 2007. Improved Pairwise Alignment of Genomic DNA. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludwig M., Sophie M. Visualization of Oligonucleotide-Based Probes Along Pseudochromosomes Using RIdeogram, KaryoploteR, and Circlize (Circos) Methods Mol. Biol. 2023;2672:409–444. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-3226-0_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu C.-S., Ma Z.-Y., Zheng G.-D., Zou S.-M., Zhang X.-J., Zhang Y.-A. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) Provides Insights into Its Genome Evolution. BMC Genom. 2022;23:271. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08503-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y., Lu Y., Zhang Y., Ning Z., Li Y., Zhao Q., Lu H., Huang R., Xia X., Feng Q., et al. The Draft Genome of the Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idellus) Provides Insights into Its Evolution and Vegetarian Adaptation. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:625–631. doi: 10.1038/ng.3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren L., Li W., Qin Q., Dai H., Han F., Xiao J., Gao X., Cui J., Wu C., Yan X., et al. The Subgenomes Show Asymmetric Expression of Alleles in Hybrid Lineages of Megalobrama Amblycephala × Culter Alburnus. Genome Res. 2019;29:1805–1815. doi: 10.1101/gr.249805.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Painter T.S., Stone W. Chromosome Fusion and Speciation in Drosophilae. Genetics. 1935;20:327–341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/20.4.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo J., Sun X., Cormack B.P., Boeke J.D. Karyotype Engineering by Chromosome Fusion Leads to Reproductive Isolation in Yeast. Nature. 2018;560:392–396. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ayala F.J., Coluzzi M. Chromosome Speciation: Humans, Drosophila, and Mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6535–6542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501847102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The final genome assembly has been deposited into the Genome Warehouse (GWH) of National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) with the accession number GWHEUUS00000000.1. The Hi-C (SRR28352443), Iso-seq (SRR28352442), and HiFi (SRR28352444) reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under BioProject number PRJNA1084914. The genome annotation files have been saved in figshare with the accession number 10.6084/m9.figshare.26310445.