Abstract

Background

Breast cancer (BC) continues to be a significant global health issue, with a rising number of cases requiring ongoing research and innovation in treatment strategies. Curcumin (CUR), a natural compound derived from Curcuma longa, and similar compounds have shown potential in targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in BC progression.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of curcumin and its analogues on BC based on cellular and molecular mechanisms.

Materials & Methods

The literature search conducted for this study involved utilizing the Scopus, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases in order to identify pertinent articles.

Results

This narrative review explores the potential of CUR and similar compounds in inhibiting STAT3 activation, thereby suppressing the proliferation of cancer cells, inducing apoptosis, and inhibiting metastasis. The review demonstrates that CUR directly inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT3, preventing its movement into the nucleus and its ability to bind to DNA, thereby hindering the survival and proliferation of cancer cells. CUR also enhances the effectiveness of other therapeutic agents and modulates the tumor microenvironment by affecting tumor‐associated macrophages (TAMs). CUR analogues, such as hydrazinocurcumin (HC), FLLL11, FLLL12, and GO‐Y030, show improved bioavailability and potency in inhibiting STAT3, resulting in reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis.

Conclusion

CUR and its analogues hold promise as effective adjuvant treatments for BC by targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway. These compounds provide new insights into the mechanisms of action of CUR and its potential to enhance the effectiveness of BC therapies.

Keywords: apoptosis, cell proliferation, curcumin, curcumin analogues, STAT3

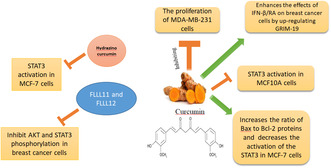

The figure is a graphical abstract illustrating the effects of curcumin and its derivatives on various breast cancer cell lines, including MCF‐7, MCF10A, and MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Curcumin is shown to inhibit the proliferation of MDA‐MB‐231 cells and enhance the effects of IFN‐β/RA on breast cancer cells by up‐regulating GRIM‐19. It also inhibits STAT3 activation in MCF10A cells and increases the ratio of Bax to Bcl‐2 proteins while decreasing the activation of STAT3 in MCF‐7 cells. Hydrazino curcumin specifically inhibits STAT3 activation in MCF‐7 cells. Additionally, FLLL11 and FLLL12 inhibit AKT and STAT3 phosphorylation in breast cancer cells.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) remains a significant global health issue, representing about 25% of all new cancer diagnoses among women and accounting for 15% of female cancer deaths. This malignancy not only poses a severe threat to women's lives and well‐being but also has profound economic, social, and familial impacts. 1 BCs are typically classified according to the presence or absence of certain receptors, which play a crucial role in determining their prognosis and treatment options. The three main categories are hormone receptor‐positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‐positive (HER2+), and triple‐negative breast cancers (TNBCs). HR+ BCs, which express estrogen and/or progesterone receptors, generally have a better prognosis and respond well to hormone therapies. HER2+ BCs are a subtype of BC characterized by the overexpression of the HER2 protein. This heightened expression of HER2 stimulates the proliferation of cancer cells and is linked to a more formidable disease progression. 2 , 3

TNBCs lack ER, PR, and HER2 expression, making them the most challenging to treat due to the absence of targeted therapies and their association with higher recurrence rates and poorer overall survival. 4 , 5 BC treatment methods are diverse and tailored to the specific characteristics of the tumor and the patient. 6 Surgery is often the first line of treatment, including procedures such as lumpectomy and mastectomy, which aim to remove the tumor and affected tissues. 7 Radiation therapy is a crucial component in the treatment of BC, significantly reducing local recurrence rates and improving BC‐specific survival after surgical interventions such as breast‐conserving surgery and mastectomy. 8 Chemotherapy is extensively employed in the management of both early and advanced stages of BC, with significant progress made in recent years to improve survival outcomes through newer therapies. 9 Hormone therapy is essential for patients with hormone receptor‐positive BC, effectively used in both adjuvant and metastatic settings to improve disease‐free survival and overall survival. 10 Targeted therapy for BC involves the use of drugs designed to specifically inhibit molecular pathways that drive tumor growth, such as HER2 inhibitors like trastuzumab and pertuzumab, which have significantly improved outcomes for HER2 − + BC patients. 11

Despite advancements, the need for new therapeutic methods and predictive factors remains critical, as the incidence of BC continues to rise globally, necessitating ongoing research and innovation in treatment strategies.

Natural compounds, such as antioxidants, are increasingly being chosen for the treatment and prevention of BC due to their ability to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and promote apoptosis without significant toxic effects. 12 , 13

These compounds, derived from plants and other natural sources, exhibit diverse biological activities, including anti‐inflammatory and anti‐carcinogenic effects, and can inhibit cancer cell growth and promote apoptosis. 14 , 15

Additionally, natural compounds often have fewer adverse effects compared to traditional chemotherapeutic drugs, making them a promising alternative or complementary approach in BC therapy. 14 , 16

Curcumin (CUR) has been extensively studied for its potential therapeutic effects in BC, particularly through its interaction with the STAT3 signaling pathway. 17 , 18 , 19

CUR directly inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT3, which is a critical step for its activation. This inhibition occurs both in constitutive and IL‐6‐inducible contexts. By preventing STAT3 phosphorylation, CUR blocks its subsequent nuclear translocation and DNA‐binding activity, thereby hindering its ability to promote gene transcription involved in cancer cell survival and proliferation. 20 , 21 CUR interferes with the IL‐6/STAT3 signaling axis, which is often upregulated in BC. By inhibiting IL‐6‐induced STAT3 activation, CUR reduces the pro‐tumorigenic effects of this pathway, such as enhanced cell proliferation and metastasis. 22 , 23 CUR has been shown to enhance the efficacy of other therapeutic agents by targeting the STAT3 pathway. For example, the combination of CUR with β‐interferon (IFN‐β) and retinoic acid (RA) has been found to synergistically inhibit STAT3 activity, leading to reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis in BC cells. 24 CUR also affects the tumor microenvironment by modulating the activity of tumor‐associated macrophages (TAMs). It effectively inhibits the PI3K/AKT/STAT3 signaling pathway in M2 macrophages, thereby significantly decreasing their capacity to induce chemoresistance in BC cells. 25 Additionally, CUR analogues inhibit STAT3 activation in BC through several specific mechanisms. CUR analogues such as hydrazinocurcumin (HC), FLLL11, FLLL12, and GO‐Y030 have been shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT3, which is a critical step for its activation. This inhibition prevents STAT3 from translocating to the nucleus and binding to DNA, thereby blocking its transcriptional activity. For example, it has been observed that HC is more effective than CUR in inhibiting the phosphorylation of STAT3 and downregulating its downstream targets. This ultimately results in a decrease in cell proliferation and an increase in apoptosis. 26 , 27 , 28

This review concludes that CUR and its analogues show promise as effective adjuvant treatments for BC by targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway, providing novel insights into the mechanisms of action of CUR and its potential to enhance the efficacy of BC therapies.

2. OVERVIEW OF CUR

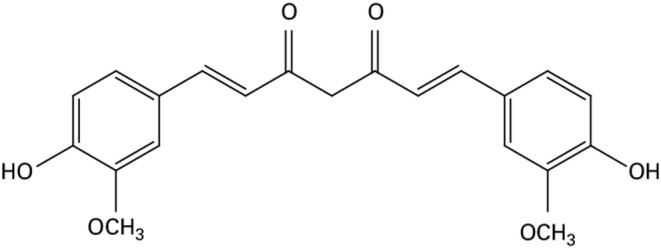

CUR, which was first discovered in 1815 and then isolated in 1842, 29 , 30 is a compound found in Curcuma, a genus of plants belonging to the Zingiberaceae family. There are approximately 50 species of Curcuma worldwide, with the main cultivation areas located in Southeast Asia and smaller populations found in Northern Australia and China. 31 CUR is extracted from Curcuma longa and has a chemical formula of C21H20O6 with a molecular mass of 368.38 g/mol (Figure 1). The chemical structure of CUR is characterized by a bis‐α, β‐unsaturated β‐diketone arrangement. This structure includes two aromatic rings with o‐methoxy phenolic groups connected by a seven‐carbon linker, which contains the α, β‐unsaturated β‐diketone moiety. 32 , 33 The unique chemical composition of CUR, also known as diferuloylmethane, is responsible for its biological properties. Curcuminoids make up approximately 2%–9% of turmeric, with commercially available turmeric extracts typically containing about 70%–75% CUR, 20% demethoxycurcumin, and 5% bisdemethoxycurcumin. 34

FIGURE 1.

Structure of CUR.

The pharmacological challenges associated with CUR, such as its limited solubility and rapid metabolism, have a significant impact on its absorption within the body's digestive system. 35 , 36

CUR is almost insoluble in water but exhibits high solubility in polar organic solvents such as DMSO and acetone, making these solvents effective for preparing concentrated solutions. In contrast, CUR is sparingly soluble in ethanol and moderately soluble in methanol, which limits its solubility in these solvents compared to DMSO and acetone. 32 , 37

Research on CUR's pharmacokinetics and bioavailability has shown that it is poorly absorbed in the gut after gastrointestinal assimilation, leading to rapid elimination from the body. 38 This limited bioavailability is attributed to CUR's low water solubility, which is approximately 11 ng/mL at pH 5.0, impeding its uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. 39 For instance, Wahlström and Blennow found that the gastrointestinal uptake of CUR in rats was only around 25%. 40 The challenge of CUR's limited bioavailability poses a barrier to its effective use in cancer treatment. However, there are various strategies available to overcome this hurdle. These include the development of novel CUR derivatives with enhanced bioavailability, the utilization of nanoparticles for CUR delivery, the implementation of combination therapy involving CUR and other substances, and the adoption of other tactical approaches to address this issue. 41 Emerging evidence suggests that synthesized CUR analogs exhibit improved solubility, enhanced bioavailability, and greater efficacy against cancers compared to CUR itself.

The CUR analogue, BDDD‐721, demonstrates enhanced efficacy in targeting medulloblastoma. BDDD‐721 effectively suppresses the growth, movement, and invasiveness of medulloblastoma cells, leading to apoptosis. This effect is primarily achieved by reducing the activity of the SHH/GLI1 signaling pathway. 42 The derivative of CUR, DMCH, has been observed to exhibit significant cytotoxicity towards human colon carcinoma cells, specifically HT29 and SW620 cell lines. Moreover, it has shown potential in inhibiting the metastasis of various colon cancer variants. These findings suggest a promising role for DMCH in the therapeutic landscape of colon cancer. 43 L48H37 effectively blocks the migratory and invasive characteristics of human osteosarcoma cell lines, U2OS and MG‐63, by modulating the JAK/STAT signaling cascade. This is achieved by suppressing urokinase‐type plasminogen activator (uPA), indicating a potential therapeutic strategy for osteosarcoma management. 44 Furthermore, through PP2A mediation, the CUR derivative EF‐24 deactivates ERK and induces cell death in acute myeloid leukemia cells by activating the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. 45

Nanomedicine provides advanced methods for targeting cancer, allowing for precise delivery of treatment to the blood vessels within the tumor, the immediate surroundings of the tumor, and individual cancer cells. 46 Various nanomaterials, such as lipid‐based nanoparticles (liposomes and solid lipid nanoparticles), polymeric nanoparticles, mesoporous silica nanoparticles, micelles, nanogels, and cyclodextrin, are commonly used in medicinal applications. 47 The utilization of these nanomaterials for drug delivery overcomes biological and disease‐related challenges, enabling the accumulation of drugs specifically in cancerous tissues. This approach improves the bioavailability of hydrophobic CUR. 48 A study suggests that the integration of CUR into nanoparticles enhances its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. These include improved dissolution, absorption, bioavailability, stability, plasma half‐life, targeted delivery, and anticancer effects. 49 The co‐delivery of doxorubicin and CUR in a polypeptide nanocarrier exhibits a synergistic effect, inducing cell death and inhibiting growth in invasive B‐cell lymphoma. This combination downregulates cancer‐promoting miRNAs like miR‐21 and miR‐199a, while simultaneously upregulating tumor‐suppressing miRNAs such as miR‐98 and miR‐200c. 50 Nanoformulated CUR is demonstrated to be more efficacious than native CUR in specifically targeting BC MDA‐MB‐231 cells. It effectively impedes growth, motility, and invasion through the attenuation of the JAK–STAT signaling pathway. 51 Magnetic nanoparticles coated with carboxymethyl chitosan and loaded with CUR exhibit enhanced effectiveness against BC MCF‐7 cells. They demonstrate lower IC50 values, signifying superior potency compared to native CUR. 52

CUR and resveratrol (RES) are two polyphenols derived from plants that are known for their beneficial properties, including anti‐inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects. 53 , 54 The concurrent administration of CUR and RES has been found to have an enhanced cytostatic effect on cells derived from breast and salivary gland cancers by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and upregulating the pro‐death UPR molecule CHOP. 55 Furthermore, the combination of CUR and RES effectively increases the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin by inhibiting the activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. 56 Additionally, the synergistic combination therapy of the polyphenols quercetin and CUR has been shown to significantly suppress the malignancy of persistent myelogenous leukemia K562 cells by modulating the p53, NF‐κB, and TGF‐α pathways. 57 Furthermore, the combination of CUR and quercetin showcases a collaborative inhibitory impact on the proliferation of A549 pulmonary cancer cells and HCT116 colonic cancer cells. Additionally, it enhances the apoptosis of A375 melanoma cells by mitigating the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway. 58 In the field of epigenetics, both CUR and quercetin have been observed to induce the acetylation of the BRCA1 promoter. The combined therapeutic application of these compounds significantly attenuates the survival and motility of TNBC cells, suggesting a potential synergistic effect in the treatment of TNBC. 59

Upon administration, CUR undergoes a complex metabolic process within the body, primarily in the liver and intestines. Initially, reductase enzymes target CUR, resulting in the loss of its double bonds and the generation of various metabolites such as octahydrocurcumins, dihydrocurcumins, and hexahydrocurcumins. These metabolites can be further converted into Mono‐C and epi‐A methylene. In the second stage of metabolism, CUR and its phase I metabolites undergo conjugation with sulfate and glucuronic acid. This leads to the formation of CUR sulfates and CUR glucuronides. 60 Subsequently, these metabolites enter the bloodstream and distribute themselves to different organs in the body. 61 Among all the metabolites, CUR glucuronide exhibits relatively lower bioactivity compared to CUR and the other metabolites. 62 Therefore, the metabolic changes in the gastrointestinal tract play a crucial role in the limited oral absorption efficiency of CUR. 61

Indeed, it is of utmost importance to recognize that the effectiveness of oral CUR intake and the metabolic pathways involved, as well as its resultant metabolites like ceruletin, DNFA, and RES, demonstrate notable inter‐individual variability. Genetic factors can also have an impact on these processes. Furthermore, the composition of the gut microbiota and the specific formulation of CUR can significantly influence the metabolic destiny of these substances. These points emphasize the intricate nature of CUR metabolism and highlight the necessity for personalized strategies in its therapeutic implementation. 63

3. OVERVIEW OF STAT3

The STAT3 gene, located on chromosome 17, encodes a protein that belongs to the STAT protein family, known for its involvement in crucial chemical signaling pathways within cells. Notably, the STAT3 gene plays a pivotal role in mediating signals for various cytokines and growth factors, such as IL‐6 and EGF. 64 , 65 The gene is rapidly tyrosine‐phosphorylated in response to these cytokines, which contributes to the redundancy and pleiotropy of cytokine actions. 64 STAT3 is an oncogene that plays a pivotal role as a crucial regulator in numerous cell‐fate determinations, particularly in myeloid cell differentiation. This gene encompasses two distinct isoforms, namely alpha (p92) and beta (p83), which exhibit dissimilarities in their transactivation domains (TAD) located at the C‐terminal region, resulting in divergent functional activities. 66

The activation of STAT3 occurs through phosphorylation, a tightly regulated and transient process in normal tissues. Research suggests that the phosphorylation level of STAT3 reaches its peak between 15 to 60 minutes after stimulation by cytokines and other factors, followed by a gradual decline. 67 The activation of STAT3 is strongly correlated with the phosphorylation of tyrosine 705 and serine 727 within the TAD. Once activated, STAT3 forms dimers that enter the nucleus to facilitate signal transduction and transcriptional activation. 68 The influence of STAT3 functional heterogeneity is attributed to the presence of four distinct isoforms: STAT3α (92 kDa), STAT3β (83 kDa), STAT3γ (72 kDa), and STAT3δ (64 kDa). These isoforms play a significant role in shaping the diverse functions of STAT3. 69 The primary isoform of STAT3, known as STAT3α, is generated through the transcription and translation of the entire STAT3 gene. It incorporates two phosphorylation sites, tyrosine and serine, within the TAD. STAT3α is instrumental in adjusting the reaction of macrophages to IL‐6 and IL‐10 at the cellular level. Furthermore, it participates in essential biological activities like immune control and cellular growth, differentiation, and the proliferation and movement of malignant cells. 70

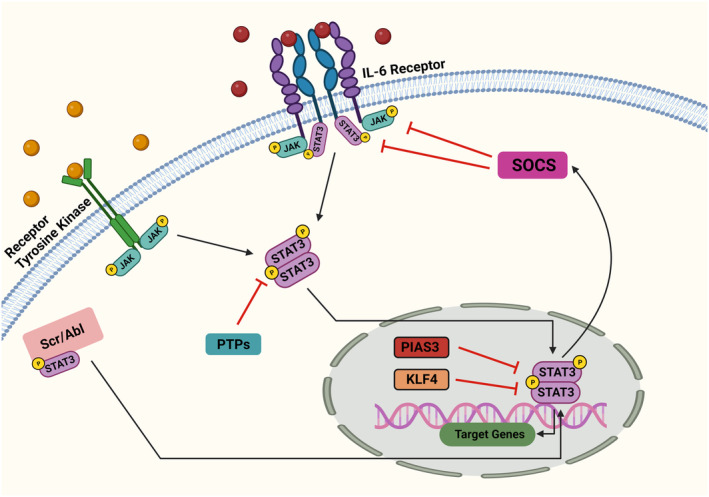

STAT3 activation can occur through multiple signaling pathways, including the canonical JAK pathway, RTKs, and other non‐ RTK pathways. The JAK pathway is typically activated by cytokines like IL‐6, where the cytokine binding to its receptor leads to JAK activation, STAT3 recruitment, phosphorylation, and subsequent dimerization and nuclear translocation to regulate gene transcription. 71 , 72 , 73 RTKs like EGFR can directly phosphorylate and activate STAT3, independently of JAKs. 74 Additionally, non‐RTKs such as Src can also phosphorylate and activate STAT3. 75 , 76 Conversely, STAT3 activity is tightly regulated by three main categories of inhibitory proteins: suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS), protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), and protein inhibitors of activated STAT (PIAS). SOCS proteins like SOCS1 and SOCS3 can inhibit STAT3 activation by 77 , 78 :

Binding to JAKs and inhibiting their kinase activity;

Competing with STAT3 for binding sites on cytokine receptors;

Targeting STAT3 regulators for proteasomal degradation.

PTPs such as SHP‐1, SHP‐2, PTPRD can directly dephosphorylate and inactivate STAT3. 77 , 79 PIAS proteins, especially PIAS3, can bind to STAT3 dimers and block their DNA‐binding ability, thereby inhibiting transcriptional activity. 80 , 81

Research suggests that Klf4 can regulate Stat3 signaling in various biological processes, such as cancer progression, neuronal development, and brain injury. 82 , 83 , 84 The activated pathways and regulators collaborate to control the activity and function of STAT3, playing crucial roles in both biological and disease‐related mechanisms. Figure 2 illustrates the activation pathways and regulators of this intricate control mechanism.

FIGURE 2.

The activity of STAT3 is regulated upstream. When cytokines or growth factors bind to their respective receptor sites, JAK kinases undergo phosphorylation and activation. This leads to the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on the receptor within the cellular structure. The unbound STAT3 protein is subsequently attracted to the receptor and binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine residue. This event occurs before STAT3 detaches from the receptor. After phosphorylation, the STAT3 protein forms dimers and translocates into the nucleus, where it influences the expression of target genes. The physiological control of STAT3 is managed by the SOCS and PIAS3. These regulators suppress JAK kinase activity and the DNA binding of STAT3, respectively. Additionally, PTP assists in dissociating activated STAT3 dimers through dephosphorylation. Interestingly, KLF4 has been found to bind to the phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705) protein, thereby suppressing STAT3 signaling upon the induction of KLF4.

Numerous cytokines and growth factors, such as IL‐6, IL‐11, oncostatin M, G‐CSF, and EGF, have the ability to activate STAT3 signaling. 82 , 83 Upon translocating into the nucleus, STAT molecules specifically bind to DNA sequences on promoters. This binding subsequently triggers the transcription of genes that regulate vital cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. 85 , 86 B cell lymphoma‐2 (Bcl‐2) and Bcl‐2 associated protein X (Bax) play crucial roles in controlling cellular longevity and apoptosis. They are significant transcriptional targets of STAT3, serving as key components of this regulatory mechanism. 87 Excessive activation of STAT3 can promote tumor development through direct pathways within tumor cells, as well as indirectly by modulating the anti‐tumor responses of cancer‐associated stromal tissue and the immune system. Within tumor cells, persistently activated STAT3 hampers the anti‐tumor immune response by continuously stimulating the production of IL‐6, IL‐10, and VEGF within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Furthermore, it induces the transcription and activation of crucial oncogenes, including programmed cell death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1), which contributes to immunosuppression. 88 , 89 , 90 Increased expression of STAT3 enhances the ability to evade the immune system or establish immune tolerance through various mechanisms. Moreover, the inflammatory milieu stimulates cancerous angiogenesis as well as the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of cancer cells. 91 Throughout the various stages of cancer development, the role of STAT3 in initiating and maintaining cancer‐promoting inflammation has been well‐established. 92 Inhibition of STAT3 has shown significant impact on the growth of BC. For instance, a study found that progestins induce the phosphorylation of Stat3 at the Ser727 residue, which is essential for the transcriptional stimulation of cyclin D1 gene expression and recruitment of Stat3 to the cyclin D1 promoter in vivo. When a STAT3S727A vector, which carries a serine‐to‐alanine mutation at codon 727, was introduced, it resulted in the abrogation of progestin‐induced proliferation of murine and human BC cells, both in vitro and in vivo. This suggests the critical role of this phosphorylation event in regulating cellular responses to progestins. 93 Another investigation demonstrated that simultaneous inhibition of STAT1 and STAT3 activation led to the downregulation of PD‐L1 expression in human BC cells. This suggests that suppression of Stat3 could influence the expression of PD‐L1, an immune checkpoint protein known to facilitate cancer growth and immune evasion. These findings highlight the potential therapeutic value of targeting STAT3 in cancer treatment strategies. 94 MARCH8, a recently discovered tumor suppressor, has been identified as having the ability to hinder the metastasis of BC and enhance the death of cancer cells by enlisting STAT3 for degradation through the proteasome‐dependent mechanism. This finding implies that the inhibition of STAT3 could potentially result in the degradation of STAT3 itself and the subsequent suppression of BC metastasis. 95 Furthermore, one study has demonstrated that the simultaneous inhibition of two signaling pathways, namely JAK2‐STAT3 and SMO‐GLI1/tGLI1, can effectively suppress BC stem cells, tumor proliferation, and metastasis. Consequently, this suggests that the inhibition of STAT3, alongside other signaling pathways, holds promise in effectively curbing the growth and progression of BC. 96

In summary, the inhibition of STAT3 has demonstrated a range of effects on BC growth. These effects encompass the suppression of cyclin D1 expression, downregulation of PD‐L1 expression, degradation of STAT3, and suppression of BC stem cells, as well as the prevention of cancer development and metastasis. These compelling findings indicate that Stat3 holds great promise as a target for the development of novel BC therapies.

4. THE REASON FOR CHOOSING THE STAT3 PATHWAY

Researchers have focused on the STAT3 signaling pathway when studying the anti‐cancer effects of CUR and its analogs/derivatives for several key reasons:

STAT3 is constitutively activated in many types of cancer cells, including BC, but not in normal cells. 51 , 97 This makes it an attractive target for cancer therapy.

STAT3 signaling plays a crucial role in the proliferation, survival, and metastasis of cancer cells. 23 , 98 Inhibiting STAT3 can lead to suppression of tumor growth and spread.

STAT3 is selectively activated in BC stem cell populations. 99 Targeting STAT3 can help eliminate the cancer stem cell phenotype and reduce the risk of tumor recurrence.

STAT3 interacts with other important transcription factors like NF‐κB, which are involved in regulating genes related to inflammation, cell survival, and angiogenesis. 99 , 100 Inhibiting the STAT3‐NF‐κB interaction can have broad anti‐tumor effects.

CUR has been shown to specifically inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation and its interaction with other proteins. 51 , 99 , 100 This makes it an effective agent for targeting the STAT3 pathway.

In summary, the constitutive activation of STAT3 in cancer cells, its critical role in tumor progression, and its interaction with other oncogenic pathways position it as a prime target for CUR and its analogs/derivatives in cancer therapy.

5. CUR EFFECTS ON STAT3 IN BC

Mammary carcinoma, a frequently observed cancer affecting females, is commonly treated with anti‐estrogen therapy in approximately 70% of individuals with ER‐positive tumors. This therapeutic approach aims to inhibit the effects of estrogen, a hormone that stimulates the growth of ER‐positive mammary carcinoma cells. 101 Recent evidence suggests that in complex malignancies, using a single molecule has limited impact on the intricate network of cellular crosstalk and negative feedback loops. To achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes, there is a significant trend in targeting multiple pathological signaling pathways simultaneously to overcome drug resistance in BC cells. 102 Researchers are actively investigating potential drug candidates to improve the management of breast carcinoma. 103 CUR has been recognized for its ability to modulate various intracellular signaling pathways. Its natural origin provides distinct advantages over synthetic compounds, offering improved safety profiles. 104 , 105 The following section will explore the therapeutic role of CUR in BC, focusing on its molecular targets, such as STAT3, and elucidating the underlying mechanisms of action (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Potential effects of CUR on BC via STAT3 signaling axis. (A) Interaction of CUR with cysteine 259 residue of STAT3 and induction of apoptosis. (B) Inhibition of JAK/STAT3 signaling axis and targeted genes by CUR results in cell cycle arrest. (C) CUR also inhibits cell growth via targeting mTOR, p53, and NF‐kβ. (D) CUR targets C‐myc and suppresses metastasis and cell survival.

Research conducted by Deng et al. revealed that CUR can spontaneously bind with STAT3 and subsequently decrease the genomic expression levels of STAT3 activity. Furthermore, in vitro studies illustrated that CUR can inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT3 in BC cells, suggesting its potential to suppress the JAK–STAT3 signaling pathway. These observations indicate that CUR may influence TNBC, at least partially, through its interactions with STAT3. 51

IFN‐β/RA refers to the combination of IFN‐β and all‐trans RA. These are two distinct compounds that are used in combination for therapeutic purposes. IFN‐β is a type of interferon, which is a protein that is part of the immune system's response to viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens. 106 It has been utilized in the therapy of diverse ailments, including specific types of cancer, due to its ability to modulate the immune response and inhibit the proliferation of malignant cells. 107 , 108 RA is a derivative of vitamin A that regulates cell growth and differentiation. 109 It has been used to treat various cancers, particularly in differentiation therapy, which aims to induce cancer cells to differentiate into more mature and less aggressive forms. 110 GRIM‐19 is a novel gene that has been the subject of scientific research due to its involvement in various cellular processes and its potential role in cancer. 111 Survivin is a protein that plays a pivotal role in regulating cell division and inhibiting apoptosis. 112 Specifically, survivin is important during the G2/M transition phase of the cellular cycle, ensuring proper cell division and the formation of new cells. 113 On the other hand, Bcl‐2 is well‐known for its anti‐apoptotic properties, which help prevent cell death. It functions by inhibiting the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, a crucial step in initiating apoptosis. 114 Bcl‐2 is essential for preserving the stability of the mitochondrial outer membrane, which is critical for cellular survival, and inhibiting the release of factors that promote apoptosis from the mitochondria. 115 Anomalies in Bcl‐2 expression are associated with various malignancies and disorders. 116 Increased expression of Bcl‐2 can enhance the survival and proliferation of neoplastic cells, making it an important target for oncological treatment. 117 In a study by Ren et al., it was observed that the combined therapy of CUR and IFN‐β/RA led to a significant increase in the expression of GRIM‐19, along with the inhibition of STAT3, survivin, and Bcl‐2 levels. These effects were particularly pronounced compared to the group treated with IFN‐β/RA alone. Overall, the study suggested that GRIM‐19 plays a significant role in BC, and its upregulation through IFN‐β/RA and CUR treatment may have potential therapeutic implications for BC treatment. The findings provided insights into the molecular mechanisms involving GRIM‐19 and its interaction with IFN‐β/RA and CUR in BC. 24

In the study conducted by Hahn et al., an investigation was carried out to examine the inhibitory effect of CUR on the STAT3 signaling pathway and its role in inducing apoptosis in H‐Ras MCF10A cells. The findings revealed that CUR has the ability to chemically modify the cysteine 259 residue in STAT3, resulting in the disruption of STAT3's phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation processes, ultimately leading to apoptosis in the cells. The study further highlighted that CUR significantly impeded the dimerization, DNA interaction, and transcriptional function of STAT3. Interestingly, its non‐electrophilic analogue, tetrahydrocurcumin, showed minimal impact on these processes. The use of thiol‐reducing agents like DTT and NAC successfully countered the suppression of STAT3 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity caused by CUR, indicating a direct correlation between CUR and STAT3, particularly at the cysteine residue(s). Furthermore, the study demonstrated that CUR's interaction with STAT3, specifically through the modification of cysteine 259, played a crucial role in triggering apoptosis. The downstream effects of STAT3 inhibition by CUR were also observed, including the suppression of Bcl‐xL, Bcl‐2, and Survivin and the induction of apoptosis in H‐Ras MCF10A cells. The research also emphasized CUR's ability to inhibit cell expansion and anchorage‐independent growth. In contrast, tetrahydrocurcumin, the non‐electrophilic analogue of CUR, had negligible effect on these cellular events. These findings highlight the unique properties of CUR in regulating biological functions and its potential as a therapeutic agent in oncology treatment. 118

The epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological process in which cells of epithelial origin undergo a transformation, losing their specific characteristics and acquiring traits typically associated with mesenchymal cells. 119 This transition involves changes in gene expression that promote the dissolution of intercellular connections and polarity, as well as the acquisition of migratory and invasive capabilities. 120 EMT is closely associated with cancer progression and metastasis, as it enables cancer cells to become more mobile and invasive. 121 Twist1 is a gene that encodes Twist‐related protein 1. 122 This protein plays a role in EMT and is known to induce EMT and extracellular matrix breakdown in cancer progression. 123 Twist1 promotes the transition of stationary epithelial cells to a more migratory and invasive phenotype associated with cancer metastasis. 124 p53 is an anti‐cancer gene that encodes a protein called p53. 125 This protein is crucial in cancer prevention by regulating the cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis. 126 p53 is often referred to as the ‘guardian of the genome’ due to its ability to respond to cellular stress and DNA damage. 127 Caveolin‐1 is a protein essential for the formation of caveolae, small invaginations in the cell plasma membrane. 128 These structures are involved in various biological functions, including signal transduction, lipid regulation, and endocytosis. 129 Gallardo and Calaf demonstrated that CUR reduced the expression of genes associated with EMT in BC cells exposed to low levels of α‐particles and estrogen in a controlled laboratory setting. Specifically, CUR decreased the expression of EMT‐related genes such as Twist1, STAT‐3, p53, and caveolin‐1. The decrease in STAT‐3 expression suggests that CUR has the potential to inhibit the regulatory responses of cytokines that are important for normal cell behavior and carcinoma development. CUR also decreased the expression of apoptotic genes including caspase‐3, caspase‐8, and cyclin D1, as well as NFκB. These changes reduced the migratory and invasive abilities of the cancer cells, indicating that CUR may affect the apoptotic processes and metastatic characteristics of BC cells. 130

M2 macrophages are a subset of macrophages involved in tissue repair, remodeling, and immunoregulation. 131 These cells are recognized for their capability to generate anti‐inflammatory cytokines, notably IL‐10, and are closely linked to facilitating tissue repair and promoting wound healing. 132 , 133 M2 macrophages are linked to promoting cancer expansion, infiltration, and dissemination by creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment that supports tumor progression. 134 M2 macrophages contribute to tissue remodeling and angiogenesis, which can facilitate the growth and spread of BC cells. 135 M2 macrophages secrete factors that sustain cancer cell existence, proliferation, and therapeutic unresponsiveness. 136 Dendrosomal CUR (DNC) is a CUR formulation, a bioactive compound extracted from the plant Curcuma longa. 137 It is a lipid‐soluble compound encapsulated in dendrosomes, which are polymeric nanocarriers. 137 DNC is designed to boost the absorption and efficacy of CUR. This formulation is intended to improve the delivery of CUR to target tissues and cells, thereby enhancing its therapeutic effects. 138 Shiri et al. found that DNC treatment down‐regulated STAT3 gene expression in mammary neoplasm and splenic tissues. This down‐regulation of STAT3 is significant as it can reduce the expression of IL‐10 and arginase I, which are associated with M2 macrophages. The decrease in STAT3 and its downstream targets suggests a decrease in M2 macrophages, which are known to promote tumor progression and growth. Additionally, the study proved that DNC therapy elevated the expression of STAT4 and IL‐12 genes, characteristic of M1 macrophages. This shift in the balance of M1 and M2 macrophages indicates the potential of DNC to exert protective effects against metastatic BC by altering the composition of macrophages in the neoplastic microhabitat. Overall, the observations indicate that DNC positively impacts the M1/M2 macrophage balance, contributing to its protective effects against metastatic BC. 139

Wang et al. demonstrated that a synergistic protocol involving CUR, arctigenin, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) significantly decreased the phosphorylation of STAT3 in MCF‐7 cells. This suggests that the combined treatment exerts an inhibitory effect on the STAT3 pathway, which is known to play a critical role in cellular proliferation, survival, and motility. This finding highlights the potential of this combination treatment as a therapeutic strategy for modulating key cellular processes. Therefore, the combination treatment exhibits promise in modulating the STAT3 pathway, which is essential for cancer prevention and treatment. 140

JAK2, also known as Janus kinase 2, plays a critical role as a non‐RTK in the JAK–STAT signaling pathway. 141 This signal transduction system is responsible for transmitting extracellular signals from cytokines and growth factors to the nucleus, ultimately regulating gene expression. 141 JAK2 is essential in various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune responses. 142 Dysregulation of JAK2 signaling has been implicated in several diseases, such as cancer and inflammatory disorders. 143 , 144 C‐Myc, a proto‐oncogene, encodes a transcription regulator that is vital in controlling cell growth, proliferation, and apoptosis. 145 It plays a crucial role in maintaining normal cellular functions and is frequently dysregulated in cancer. 146 The c‐Myc protein acts as a key transcriptional regulator, significantly influencing various cellular activities, including cell cycle progression, metabolic processes, and cellular differentiation. 147 Hendrayan et al. conducted a study which demonstrated that CUR significantly reduced the activated form of JAK2 and its downstream regulator STAT3, while leaving the inactive variants unaffected. These findings suggest that CUR effectively hinders the phosphorylation of these two proteins, particularly in mammary stromal fibroblasts. Additionally, CUR inhibited the STAT3 pathway, leading to the downregulation of its downstream targets c‐Myc and survivin. As a result, the study concluded that CUR exerts its effects by suppressing oncogenic cytokines and inhibiting the STAT3 pathway. This discovery highlights the potential therapeutic use of CUR as a medicinal compound in the field of oncology. 148

In summary, the overactivation of STAT3 has been implicated in various cancers, suggesting that inhibiting its activity could yield therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment. By specifically targeting STAT3, it may be possible to disrupt pro‐oncogenic signaling pathways, thereby impeding cancer cell growth and survival. Moreover, the role of STAT3 in the tumor microenvironment suggests that targeting this transcription factor could also influence the immune response within the tumor, which holds potential implications for cancer immunotherapy and immunology. These broader implications underscore the significance of targeting STAT3 in developing more effective and comprehensive strategies for cancer prevention and therapy. CUR has shown promise as a potential treatment for BC due to its ability to inhibit STAT3 signaling, induce apoptosis, and hinder proliferation. These findings shed light on CUR's potential as a targeted therapy for BC, providing novel insights into its mechanism of action and its capacity to modulate STAT3 signaling. A summary of study results can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Curcumin effects on STAT3 in breast cancer.

| Authors | Dosage of curcumin (CUR) | Type of model | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deng et al. | (0.27, 2.71, 13.57, 54.29, 135.73 μM) | MDA‐MB‐231 cell | Both CUR and its nano‐formulations (CUR‐NPs) were capable of inhibiting the invasion, migration, and proliferation of MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Additionally, they induced apoptosis in these cells and downregulated the genetic expression levels of the aforementioned targets |

| Ren et al. | 40 μM | MCF‐7 cell | CUR synergistically enhances the effects of IFN‐β/RA on BC cells by up‐regulating GRIM‐19 through these pathways |

| Hahn et al. | (25, 10, and 50 μM) | H‐Ras MCF10A cells | CUR seems to directly interact and inhibit STAT3 activation, hence preventing mammary carcinogenesis by promoting apoptosis in H‐Ras MCF10A cells. |

| Shiri et al. | 40 and 80 mg/kg | mice | Treatment with dendrosomal curcumin (DNC) decreased the expression of STAT3, indicating low levels of M2 macrophage. This suggests that CUR has an inhibitory effect on STAT3, ultimately influencing the balance of M1/M2 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment |

| Wang et al. | (5–10 μM) | MCF‐7 cell | Green tea polyphenol, and CUR increased the ratio of Bax to Bcl‐2 proteins and decreased the activation of NFκB, PI3K/Akt, and STAT3 pathways, thereby reducing cell migration |

| Hendrayani et al. | 10 μM | CAF cell | CUR induces p16‐dependent senescence in active breast cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs). This senescence significantly reduces the procarcinogenic paracrine effects of CAFs on BC cells. |

6. CUR ANALOGUES EFFECTS ON STAT3 IN BC

CUR analogues are synthetic compounds that have been developed to enhance the effectiveness of CUR as a therapeutic agent for cancer. These analogues specifically target the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, which is associated with oncogenic processes and drug resistance in cancer cells. Examples of CUR analogues include FLLL31, FLLL32, and FLL6217–19, which have been designed to improve the bioavailability and anticancer properties of CUR by stabilizing the central β‐diketone linker. 149 , 150 , 151 Ongoing research efforts are focused on developing these analogues as more efficient treatments for various types of cancer, including BC.

AKT, a serine/threonine‐specific protein kinase, plays a crucial role in a range of cellular activities, including cell growth, survival, and metabolism. 152 Activation of AKT promotes cell proliferation, which contributes to the growth and spread of BC cells. This highlights the importance of targeting AKT as a potential therapeutic strategy in oncology. 153 HER2/neu, also known as the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, is a 185‐kDa protein located on the cell membrane. It is found to be overexpressed in approximately 25–30% of BCs, primarily due to gene amplification of HER2. 154 This overexpression of HER2/neu is associated with poor prognosis, reduced recurrence intervals, and low survival rates in patients with BC. 155 Furthermore, evidence suggests that cancer cells with overexpression of HER2/neu may exhibit reduced sensitivity to chemotherapy treatments. Therefore, HER2/neu is a crucial physiological indicator and a significant medicinal objective in BC. 156 Lin et al. elucidated that the CUR derivatives, FLLL11 and FLLL12, effectively inhibit the STAT3, AKT, and HER2/neu pathways in BC cells. These analogues exhibited greater potency than CUR in reducing cell survivability, inhibiting cellular movement, and obstructing the development of colonies in soft agar, along with their role in triggering apoptosis in human BC cells. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that FLLL11 and FLLL12 work synergistically with doxorubicin to effectively inhibit the proliferation of MDA‐MB‐231 BC cells. The study also confirmed that FLLL11 and FLLL12 downregulate HER2/neu expression and AKT phosphorylation, which is crucial in cancer cells' resistance to medication, invasion, and blood vessel formation. Additionally, FLLL11 and FLLL12 were discovered to be potent inhibitors of activated STAT3 in vitro. This underscores the potential of these CUR analogues as therapeutic agents in cancer treatment. 28

HC is a synthetic analogue of CUR that is obtained as a pale yellow gum. 157 In comparison to CUR, HC demonstrates a significant improvement in water solubility and stability. Furthermore, it exhibits high cell permeability, resulting in enhanced bioavailability and more favorable pharmacological activity. These characteristics suggest that HC may be a more effective therapeutic agent due to its improved physicochemical properties and pharmacodynamics. 26 Wang et al. have demonstrated that HC exhibits greater efficacy in inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation and downregulating various downstream targets of STAT3. Consequently, HC effectively suppresses cell proliferation, inhibits colony formation, reduces cell migration and invasion, and induces apoptosis in human BC cells. Moreover, HC demonstrates significantly higher potency than CUR in suppressing cell viability, anchorage‐independent growth, cell cycle progression, apoptosis, cell migration, and invasion. Additionally, HC proves to be more effective than CUR in inhibiting the expression of the STAT3 protein and its downstream targets, including MMP‐9, Mcl‐1, c‐Myc, Bcl‐2, and survivin. These findings suggest that HC shows promising potential as a therapeutic or preventive agent for human breast carcinoma, indicating its potential for clinical application. 26 In another study, Zhang et al. conducted research on HC‐encapsulated nanoparticles (HC‐NPs) and their effects on TAMs. The study found that HC‐NPs were successful in re‐educating TAMs from a pro‐tumor M2‐like phenotype to an anti‐tumor M1‐like phenotype by inhibiting STAT3 signaling. This re‐education led to the regulation of the interaction between tumor cells and TAMs, resulting in the inhibition of tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Furthermore, the HC‐NPs induced morphological changes in the treated cells and caused a shift from the M2‐like phenotype to the M1‐like phenotype in macrophages. As a result, the re‐educated macrophages showed a significant decrease in 4 T1 breast tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and an increase in apoptosis. Overall, the findings of this study highlight the substantial impact of HC‐NPs in inhibiting STAT3 activity and modulating the crosstalk between TAMs and tumor cells, ultimately restraining tumor progression. 158

ROS are highly reactive molecules that contain oxygen and are naturally produced in cells as byproducts of normal cellular metabolism. 159 , 160 Cancer cells, in response to oncogenic signals, typically experience moderate levels of ROS due to their increased metabolic activity. 161 While moderate oxidative stress can benefit various processes in cancer cells, excessive levels of ROS can cause irreversible damage to DNA and lipids. This damage can ultimately trigger apoptosis in cancer cells. 162 In a study by Zhang et al., compound 6b, a monocarbonyl analogue of CUR conjugated with a bis(thiosemicarbazone) moiety, was found to exhibit potent and selective cytotoxic activity against MCF‐7 and MCF‐7/DOX cells, while having minimal cytotoxic effects on MCF‐10A breast epithelial cells. The compound showed a 7‐ to 21‐fold increase in its selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells compared to normal cells. Importantly, compound 6b was found to strongly bind to the SH2 domain of STAT3, suggesting its potential as a potent inhibitor of the STAT3‐SH2 domain. Furthermore, it effectively blocked both constitutive and IL‐6‐induced STAT3 phosphorylation, regulated the expression of STAT3 downstream target genes, suppressed STAT3‐mediated P‐gp expression, induced ROS production, and demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting xenografted human BC in vivo without causing any apparent harm. These findings highlight the potential of compound 6b as a promising therapeutic agent for BC. The study also suggests that compound 6b and similar novel compounds with direct STAT3 inhibition and ROS production activity could be potential therapeutics for BC. 19

GO‐Y030 is an artificial derivative of CUR, a polyphenolic compound extracted from the rhizome of the perennial herb Curcuma longa. 163 It was developed as a potential solution to the low bioavailability of CUR, which hampers its use in therapeutic applications. 164 Hutzen et al. have highlighted that GO‐Y030 demonstrates significantly higher potency than CUR in suppressing the viability of human BC cells. GO‐Y030 was observed to induce apoptosis and disrupt the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of STAT3 in BC cells. The compound also exhibited the ability to inhibit STAT3‐dependent transcriptional activity and suppress the anchorage‐independent growth of cancer cells. These findings suggest that GO‐Y030 holds promising potential as a therapeutic agent for cancers with elevated levels of activated STAT3, highlighting its potential for clinical application. This emphasizes the need for further research into the efficacy of GO‐Y030 in cancer treatment. 27 By overcoming the limitation of low bioavailability of CUR and acting as a potent inhibitor of cancer cell growth, GO‐Y030 could have practical applications in cancer chemotherapy. The observed synergistic effects with low toxicity and the ability to overcome drug resistance seen with GO‐Y030 could make it valuable for combination therapy with cytotoxic agents, opening up new possibilities for future treatments in cancer therapy. 165

In summary, the research regarding CUR analogs indicates considerable potential for the development of innovative therapies for BC through the modulation of the tumor microenvironment, inhibition of tumor growth, suppression of STAT3 activity, and enhancement of the survival rate among BC patients. These findings further emphasize the significance of ongoing exploration and advancement in the realm of CUR analogs for the future management and treatment of BC. A comprehensive overview of the study outcomes can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Curcumin analogues effects on STAT3 in breast cancer.

| Authors | Curcumin analogues/dosage of curcumin analogues | Type of model | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. |

FLLL11: 0.3–5.7 FLLL12: 0.3–3.8 micromol/L |

MDA‐MB‐231 MCF‐7 MDA‐MB‐468 |

New CUR analogues exhibited significantly enhanced growth‐suppressive activity against BC cells compared to CUR itself. These analogues potently inhibited the phosphorylation and activation of AKT and STAT3, two key signaling proteins implicated in cancer cell survival and proliferation |

| Wang et al. | Hydrazinocurcumin (HC): 1 and 5 μmol/L | MDA‐MB‐231 and MCF‐7 cancer cells | HC exhibited strong inhibitory effects on the carcinogenicity of BC cells through the inhibition of STAT3. |

| Zhang et al. | HC: 180 μM | 4 T1 | HC‐NPs were able to ‘re‐educate’ tumor‐associated macrophages (TAMs), causing them to switch from M2 to M1‐like phenotype by suppressing STAT3 activity |

| Hutzen et al. | GO‐Y030: 1.0, 2.5, and 5 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 | GO‐Y030 was able to interfere with STAT3, a persistently activated transcription factor in breast cancer, by inhibiting its phosphorylation and transcriptional activity |

7. CONCLUSION

This review presents an overview of the potential of CUR and its analogues in targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway for the treatment of BC. It explores the role of STAT3 in the progression of BC and the potential of CUR and its analogues in modulating this pathway. Research findings demonstrate that CUR and its analogues effectively inhibit STAT3, resulting in downstream effects such as the suppression of cancer cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of metastasis. This review also highlights the potential synergistic effects of combining CUR with other compounds to enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to treatment. Furthermore, it discusses the development of CUR analogues, namely FLLL31, GO‐Y030, and HC, which are designed to enhance the potency of CUR as a therapeutic agent for cancer treatment, with a particular focus on their potential in targeting the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. The review emphasizes the broader implications of targeting STAT3 in the development of more effective and comprehensive strategies for cancer prevention and therapy. In conclusion, CUR and its analogues show promise as effective adjuvant treatments, providing new insights for the development of more targeted and comprehensive strategies for BC therapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Maryam Golmohammadi: Writing – original draft. Mohammad Yassin Zamanian: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration. Ahmed Muzahem Al‐Ani: Resources. Thaer L. Jabbar: Writing – original draft. Ali Kamil Kareem: Resources; writing – original draft. Zeinab Hashem Aghaei: Visualization. Hossein Tahernia: Writing – original draft. Ahmed Hjazi: Writing – review and editing. Saad Abdul‐ridh Jissir: Data curation; resources. Elham Hakimizadeh: Conceptualization; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

CONSENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Golmohammadi M, Zamanian MY, Al‐Ani AM, et al. Targeting STAT3 signaling pathway by curcumin and its analogues for breast cancer: A narrative review. Anim Models Exp Med. 2024;7:853‐867. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12491

Maryam Golmohammadi and Mohammad Yasin Zamanian contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Yassin Zamanian, Email: mzamaniyan66@yahoo.com.

Elham Hakimizadeh, Email: hakimizadeh_elham@yahoo.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reddy TP, Rosato RR, Li X, Moulder S, Piwnica‐Worms H, Chang JC. A comprehensive overview of metaplastic breast cancer: clinical features and molecular aberrations. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, et al. Strategies for subtypes—dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1736‐1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patnayak R, Jena A, Rukmangadha N, et al. Hormone receptor status (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor), human epidermal growth factor‐2 and p53 in south Indian breast cancer patients: a tertiary care center experience. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 2015;36(2):117‐122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maqbool M, Bekele F, Fekadu G. Treatment Strategies against Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer: an Updated Review. Targets and Therapy; 2023:15‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li L, Zhang F, Liu Z, Fan Z. Immunotherapy for triple‐negative breast cancer: combination strategies to improve outcome. Cancer. 2023;15(1):321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zardavas D, Irrthum A, Swanton C, Piccart M. Clinical management of breast cancer heterogeneity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(7):381‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kunkler IH, Williams LJ, Jack WJL, Cameron DA, Dixon JM. Breast‐conserving surgery with or without irradiation in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(7):585‐594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Riaz N, Jeen T, Whelan TJ, Nielsen TO. Recent advances in optimizing radiation therapy decisions in early invasive breast cancer. Cancer. 2023;15(4):1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van den Ende NS, Nguyen AH, Jager A, Kok M, Debets R, van Deurzen CHM. Triple‐negative breast cancer and predictive markers of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magno E, Bussard KM. A representative clinical course of progression, with molecular insights, of hormone receptor‐positive, HER2‐negative bone metastatic breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(6):3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swain SM, Shastry M, Hamilton E. Targeting HER2‐positive breast cancer: advances and future directions. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(2):101‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herdiana Y, Sriwidodo S, Sofian FF, Wilar G, Diantini A. Nanoparticle‐based antioxidants in stress signaling and programmed cell death in breast cancer treatment. Molecules. 2023;28(14):5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herdiana Y, Husni P, Nurhasanah S, Shamsuddin S, Wathoni N. Chitosan‐based nano systems for natural antioxidants in breast cancer therapy. Polymers. 2023;15(13):2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alam B et al. Plant‐based natural products for breast cancer prevention: a south Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries perspective. Clin Surg. 2021;2021(6):3047. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noel B, Singh SK, Lillard JW, Singh R. Role of natural compounds in preventing and treating breast cancer. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2020;12:137‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Islam MR, Islam F, Nafady MH, et al. Natural small molecules in breast cancer treatment: understandings from a therapeutic viewpoint. Molecules. 2022;27(7):2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pluta R, Januszewski S, Ułamek‐Kozioł M. Mutual two‐way interactions of curcumin and gut microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oglah MK et al. Curcumin and its derivatives: a review of their biological activities. Syst Rev Pharm. 2020;11(3):472‐481. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang W, Guo J, Li S, et al. Discovery of monocarbonyl curcumin‐BTP hybrids as STAT3 inhibitors for drug‐sensitive and drug‐resistant breast cancer therapy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):46352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bharti AC, Donato N, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits constitutive and IL‐6‐inducible STAT3 phosphorylation in human multiple myeloma cells. J Immunol. 2003;171(7):3863‐3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glienke W, Maute L, Wicht J, Bergmann L. Curcumin inhibits constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation in human pancreatic cancer cell lines and downregulation of survivin/BIRC5 gene expression. Cancer Investig. 2009;28(2):166‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Farghadani R, Naidu R. Curcumin: modulator of key molecular signaling pathways in hormone‐independent breast cancer. Cancer. 2021;13(14):3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. To, S.Q et al. STAT3 signaling in breast cancer: multicellular actions and therapeutic potential. Cancer. 2022;14(2):429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ren M, Wang Y, Wu X, Ge S, Wang B. Curcumin synergistically increases effects of β‐interferon and retinoic acid on breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by up‐regulation of GRIM‐19 through STAT3‐dependent and STAT3‐independent pathways. J Drug Target. 2017;25(3):247‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deswal B, Bagchi U, Kapoor S. Curcumin suppresses M2 macrophage‐derived paclitaxel Chemoresistance through inhibition of PI3K‐AKT/STAT3 signaling. Anti‐Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry‐Anti‐Cancer Agents). 2024;24(2):146‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X et al. The curcumin analogue hydrazinocurcumin exhibits potent suppressive activity on carcinogenicity of breast cancer cells via STAT3 inhibition. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(4):1189‐1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hutzen B, Friedman L, Sobo M, et al. Curcumin analogue GO‐Y030 inhibits STAT3 activity and cell growth in breast and pancreatic carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2009;35(4):867‐872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin L, Hutzen B, Ball S, et al. New curcumin analogues exhibit enhanced growth‐suppressive activity and inhibit AKT and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 phosphorylation in breast and prostate cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(9):1719‐1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vogel A, Pelletier J. Examen chimique de la racine de Curcuma. J Pharm. 1815;1:289‐300. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farooqui T, Farooqui AA. Curcumin: historical background, chemistry, pharmacological action, and potential therapeutic value. Curcumin for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. 2019;1:23‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie L, Ji X, Zhang Q, Wei Y. Curcumin combined with photodynamic therapy, promising therapies for the treatment of cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146:112567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Priyadarsini KI. The chemistry of curcumin: from extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules. 2014;19(12):20091‐20112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kawano S‐i et al. Analysis of keto‐enol tautomers of curcumin by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Chin Chem Lett. 2013;24(8):685‐687. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cacciola NA, Cuciniello R, Petillo GD, Piccioni M, Filosa S, Crispi S. An overview of the enhanced effects of curcumin and chemotherapeutic agents in combined cancer treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sabet S, Rashidinejad A, Melton LD, McGillivray DJ. Recent advances to improve curcumin oral bioavailability. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;110:253‐266. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Z, Smart JD, Pannala AS. Recent developments in formulation design for improving oral bioavailability of curcumin: a review. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2020;60:102082. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Horosanskaia E, Yuan L, Seidel‐Morgenstern A, Lorenz H. Purification of curcumin from ternary extract‐similar mixtures of curcuminoids in a single crystallization step. Crystals. 2020;10(3):206. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):807‐818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tønnesen HH, Másson M, Loftsson T. Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids. XXVII. Cyclodextrin complexation: solubility, chemical and photochemical stability. Int J Pharm. 2002;244(1–2):127‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wahlström B, Blennow G. A study on the fate of curcumin in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1978;43(2):86‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ming T, Tao Q, Tang S, et al. Curcumin: an epigenetic regulator and its application in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gong W, Zhao W, Liu G, Shi L, Zhao X. Curcumin analogue BDDD‐721 exhibits more potent anticancer effects than curcumin on medulloblastoma by targeting Shh/Gli1 signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2022;14(13):5464‐5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rahim NFC, Hussin Y, Aziz MNM, et al. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis effects of curcumin analogue (2E, 6E)‐2, 6‐Bis (2, 3‐Dimethoxybenzylidine) cyclohexanone (DMCH) on human colon cancer cells HT29 and SW620 in vitro. Molecules. 2021;26(5):1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lu K‐H, Wu HH, Lin RC, et al. Curcumin analogue l48h37 suppresses human osteosarcoma u2os and mg‐63 cells' migration and invasion in culture by inhibition of upa via the jak/stat signaling pathway. Molecules. 2020;26(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hsiao P‐C, Chang JH, Lee WJ, et al. The curcumin analogue, EF‐24, triggers p38 MAPK‐mediated apoptotic cell death via inducing PP2A‐modulated ERK deactivation in human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer. 2020;12(8):2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kydd J, Jadia R, Velpurisiva P, Gad A, Paliwal S, Rai P. Targeting strategies for the combination treatment of cancer using drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2017;9(4):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maleki Dizaj S, Alipour M, Dalir Abdolahinia E, et al. Curcumin nanoformulations: beneficial nanomedicine against cancer. Phytother Res. 2022;36(3):1156‐1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farhoudi L, Kesharwani P, Majeed M, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Polymeric nanomicelles of curcumin: potential applications in cancer. Int J Pharm. 2022;617:121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amekyeh H, Alkhader E, Sabra R, Billa N. Prospects of curcumin nanoformulations in cancer management. Molecules. 2022;27(2):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo W, Song Y, Song W, et al. Co‐delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin with polypeptide nanocarrier for synergistic lymphoma therapy. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Deng Z, Chen G, Shi Y, et al. Curcumin and its nano‐formulations: defining triple‐negative breast cancer targets through network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental verification. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:920514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pazouki N, Irani S, Olov N, Atyabi SM, Bagheri‐Khoulenjani S. Fe3O4 nanoparticles coated with carboxymethyl chitosan containing curcumin in combination with hyperthermia induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Progress in Biomaterials. 2022;11(1):43‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. He Y, Yue Y, Zheng X, Zhang K, Chen S, du Z. Curcumin, inflammation, and chronic diseases: how are they linked? Molecules. 2015;20(5):9183‐9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Han G, Xia J, Gao J, Inagaki Y, Tang W, Kokudo N. Anti‐tumor effects and cellular mechanisms of resveratrol. Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 2015;9(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Arena A, Romeo MA, Benedetti R, et al. New insights into curcumin‐and resveratrol‐mediated anti‐cancer effects. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(11):1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Muhanmode Y et al. Curcumin and resveratrol inhibit chemoresistance in cisplatin‐resistant epithelial ovarian cancer cells via targeting P13K pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2022;41:9603271221095929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mutlu Altundağ E, Yılmaz AM, Serdar BS, Jannuzzi AT, Koçtürk S, Yalçın AS. Synergistic induction of apoptosis by quercetin and curcumin in chronic myeloid leukemia (K562) cells: II. Signal transduction pathways involved. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(4):703‐712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Srivastava NS, Srivastava RAK. Curcumin and quercetin synergistically inhibit cancer cell proliferation in multiple cancer cells and modulate Wnt/β‐catenin signaling and apoptotic pathways in A375 cells. Phytomedicine. 2019;52:117‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kundur S, Prayag A, Selvakumar P, et al. Synergistic anticancer action of quercetin and curcumin against triple‐negative breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(7):11103‐11118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dei Cas M, Ghidoni R. Dietary curcumin: correlation between bioavailability and health potential. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zheng B, McClements DJ. Formulation of more efficacious curcumin delivery systems using colloid science: enhanced solubility, stability, and bioavailability. Molecules. 2020;25(12):2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tsuda T. Curcumin as a functional food‐derived factor: degradation products, metabolites, bioactivity, and future perspectives. Food Funct. 2018;9(2):705‐714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moetlediwa MT, Ramashia R, Pheiffer C, Titinchi SJJ, Mazibuko‐Mbeje SE, Jack BU. Therapeutic effects of curcumin derivatives against obesity and associated metabolic complications: a review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(18):14366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shi W, Inoue M, Minami M, et al. The genomic structure and chromosomal localization of the mouse STAT3 gene. Int Immunol. 1996;8(8):1205‐1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kato K, Nomoto M, Izumi H, et al. Structure and functional analysis of the human STAT3 gene promoter: alteration of chromatin structure as a possible mechanism for the upregulation in cisplatin‐resistant cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)‐Gene Structure and Expression. 2000;1493(1–2):91‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shao H, Quintero AJ, Tweardy DJ. Identification and characterization of cis elements in the STAT3 gene regulating STAT3α and STAT3β messenger RNA splicing. Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2001;98(13):3853‐3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Subramaniam A, Shanmugam MK, Perumal E, et al. Potential role of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 signaling pathway in inflammation, survival, proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)‐reviews on. Cancer. 2013;1835(1):46‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lin W‐H, Chang YW, Hong MX, et al. STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727 and Tyr705 differentially regulates the EMT–MET switch and cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2021;40(4):791‐805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tolomeo M, Cascio A. The multifaced role of STAT3 in cancer and its implication for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dewilde S et al. Of alphas and betas: distinct and overlapping functions of STAT3 isoforms. Frontiers in Bioscience‐Landmark. 2008;13(17):6501‐6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peyser ND, Freilino M, Wang L, et al. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of PTPRT increases STAT3 activation and sensitivity to STAT3 inhibition in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35(9):1163‐1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang X, Guo A, Yu J, et al. Identification of STAT3 as a substrate of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase T. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(10):4060‐4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL‐6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(4):234‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jin W. Role of JAK/STAT3 signaling in the regulation of metastasis, the transition of cancer stem cells, and chemoresistance of cancer by epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cells. 2020;9(1):217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gu Y, Mohammad IS, Liu Z. Overview of the STAT‐3 signaling pathway in cancer and the development of specific inhibitors. Oncol Lett. 2020;19(4):2585‐2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wu M et al. Negative regulators of STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:4957‐4969. doi: 10.2147/CMAR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Xia T, Zhang M, Lei W, et al. Advances in the role of STAT3 in macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1160719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tamiya T, Kashiwagi I, Takahashi R, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and JAK/STAT pathways: regulation of T‐cell inflammation by SOCS1 and SOCS3. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(5):980‐985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wu M, Song D, Li H, et al. Negative regulators of STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:4957‐4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shuai K, Liu B. Regulation of gene‐activation pathways by PIAS proteins in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):593‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yagil Z, Nechushtan H, Kay G, Yang CM, Kemeny DM, Razin E. The enigma of the role of protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 (PIAS3) in the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2010;31(5):199‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Luo D‐D, Zhao F. KLF4 suppresses the proliferation and metastasis of NSCLC cells via inhibition of MSI2 and regulation of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. Transl Oncol. 2022;22:101396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cui DM, Zeng T, Ren J, et al. KLF 4 knockdown attenuates TBI‐induced neuronal damage through p53 and JAK‐STAT 3 signaling. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(2):106‐118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sahin GS, Dhar M, Dillon C, et al. Leptin stimulates synaptogenesis in hippocampal neurons via KLF4 and SOCS3 inhibition of STAT3 signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2020;106:103500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Okitsu K, Kanda T, Imazeki F, et al. Involvement of interleukin‐6 and androgen receptor signaling in pancreatic cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(8):859‐867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bharadwaj U, Marin‐Muller C, Li M, Chen C, Yao Q. Mesothelin overexpression promotes autocrine IL‐6/sIL‐6R trans‐signaling to stimulate pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(7):1013‐1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gozgit JM, Bebernitz G, Patil P, et al. Effects of the JAK2 inhibitor, AZ960, on Pim/BAD/BCL‐xL survival signaling in the human JAK2 V617F cell line SET‐2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32334‐32343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang T, Niu G, Kortylewski M, et al. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat‐3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):48‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wang Y‐S, Chen C, Zhang SY, Li Y, Jin YH. (20S) Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits STAT3/VEGF signaling by targeting annexin A2. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Song TL, Nairismägi ML, Laurensia Y, et al. Oncogenic activation of the STAT3 pathway drives PD‐L1 expression in natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma. Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2018;132(11):1146‐1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wang Y, Shen Y, Wang S, Shen Q, Zhou X. The role of STAT3 in leading the crosstalk between human cancers and the immune system. Cancer Lett. 2018;415:117‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bollrath J, Phesse TJ, von Burstin VA, et al. gp130‐mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell‐cycle progression during colitis‐associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):91‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tkach, M. , et al., p42/p44 MAPK‐Mediated Stat3 Ser727 Phosphorylation Is Required for Progestin‐Induced Full Activation of Stat3 and Breast Cancer Growth. Endocrine‐Related Cancer. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Song Y‐M, Qian XL, Xia XQ, et al. STAT3 and PD‐L1 are negatively correlated with ATM and have impact on the prognosis of triple‐negative breast cancer patients with low ATM expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;196(1):45‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chen W, Patel D, Jia Y, et al. MARCH8 suppresses tumor metastasis and mediates degradation of STAT3 and CD44 in breast cancer cells. Cancer. 2021;13(11):2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Doheny D, Sirkisoon S, Carpenter RL, et al. Combined inhibition of JAK2‐STAT3 and SMO‐GLI1/tGLI1 pathways suppresses breast cancer stem cells, tumor growth, and metastasis. Oncogene. 2020;39(42):6589‐6605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Banerjee K, Resat H. Constitutive activation of STAT 3 in breast cancer cells: a review. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(11):2570‐2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zuo M, Li C, Lin J, Javle M. LLL12, a novel small inhibitor targeting STAT3 for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6(13):10940‐10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Chung SS, Vadgama JV. Curcumin and epigallocatechin gallate inhibit the cancer stem cell phenotype via down‐regulation of STAT3–NFκB signaling. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(1):39‐46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Afshari H, Noori S, Daraei A, Azami Movahed M, Zarghi A. A novel imidazo[1,2‐a]pyridine derivative and its co‐administration with curcumin exert anti‐inflammatory effects by modulating the STAT3/NF‐κB/iNOS/COX‐2 signaling pathway in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. A Novel Imidazo [1, 2‐a] Pyridine Derivative and its co‐Administration with Curcumin Exert Anti‐Inflammatory Effects by Modulating the STAT3/NF‐κB/iNOS/COX‐2 Signaling Pathway in Breast and Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Vol 14. BI; 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Del Re M et al. Pharmacogenetics of anti‐estrogen treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):442‐450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Huang M, Zhai BT, Fan Y, et al. Targeted drug delivery systems for curcumin in breast cancer therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023;18:4275‐4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wang Y, Yu J, Cui R, Lin J, Ding X. Curcumin in treating breast cancer: a review. Journal of Laboratory Automation. 2016;21(6):723‐731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]