Abstract

Dried blood spot (DBS) sampling offers significant advantages over conventional blood collection methods, such as reduced sample volume, minimal invasiveness, suitability for home-based sampling, and ease of transport. However, understanding the effects of variable storage temperatures and times on metabolite stability is crucial due to varying intervals and delivery conditions between sample collection and metabolomics analysis. To minimize biological variances, all samples were collected from the same individual simultaneously and stored at three different temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C) for diverse time points (3, 7, 14, and 21 days). Metabolic profiling was conducted an untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS)-based multi-platform metabolomics. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed alterations in metabolite stability at different temperatures, with phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and triglycerides (TAGs) as the first principal component (PC1). Specifically, we identified 69 metabolites that remained stable across all three temperatures over the 21-day period, while 78 metabolites exhibited instability. Furthermore, linear correlations between metabolite intensity and storage time were observed. Overall, our study elucidated the influence of storage temperature and time on specific metabolite stability in DBS samples, providing valuable insights for study design, biomarker selection, and data improvement.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82041-2.

Keywords: DBS, Metabolite stability, Metabolomics, Storage temperature and time

Subject terms: Metabolomics, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

Metabolomics, the comprehensive study of metabolites within biological systems, is pivotal for elucidating biochemical processes, understanding disease mechanisms, and evaluating drug responses1. This analytical approach offers valuable insights into the overall phenotype of biological systems. Blood stands out as one of the most frequently utilized biological fluids in medical diagnostics and research purposes due to its accessibility, complex composition, and ability to reflect systemic physiological states2. However, blood sample collection presents various challenges, such as the high costs of sampling procedures, the need for specialized handling post-collection, and logistical difficulties in transportation and storage, particularly in remote regions. Consequently, with the evolution of personalized precision medicine and population health research frameworks, developing a convenient sampling method and enhancing patient engagement for expanding bioanalytical capabilities in healthcare is necessary.

Dried blood spot (DBS) sampling, tracing back to its inception in 19633, has primarily been utilized for neonatal disease screening and health assessment4. Beyond its traditional role in newborn screening, DBS has found applications in diverse fields, including environmental contaminant tracking, drug monitoring, genomics, and proteomics5–7. Recently, DBS has garnered increased attention for its utility in metabolomics, particularly for biomarker discovery and disease diagnostics8–10. DBS presents an enticing alternative sampling approach for clinical applications, thanks to its notable benefits including reduced sample volume, minimal invasiveness, the feasibility of home-based sampling, and easy transportability11. Despite the significant advantages of DBS techniques in various fields, preserving metabolite stability during transportation and storage remains a significant challenge.

It is widely recognized that storing plasma or serum samples at -80℃ results in minimal alteration of metabolites12. Research has shown that storing DBS at temperatures of either − 20 °C or -80 °C effectively preserves most metabolites for at least 2 years13. Furthermore, research has indicated that storing DBS at -20 °C for one year is advantageous for preserving metabolite stability14. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that certain metabolites in DBS exhibit varying degrees of stability after 168 days of storage under different temperature conditions. Notably, lipid metabolites are less stable at higher temperatures, while amino acid metabolites show relatively moderate bidirectional concentration changes15. In contrast, most amino acids in DBS showed significant degradation after one year of storage at 4 °C, followed by four years at room temperature16. Notably, the majority (71%) of the metabolites remained stable during 10 years of storage at -20 °C, although lipid metabolites exhibited a decreasing trend17. However, the intervals and delivery conditions from sample collection to metabolomics analysis often do not match the ideal conditions. While controlled studies on metabolite stability in DBS have primarily focused on elevated temperatures such as room temperature18, our understanding of the detailed stability of specific metabolites remains limited. The storage conditions of DBS samples may have an adverse effect on the metabolite profiles, particularly affecting representative biomarker candidates and potentially compromising the reliability of DBS samples for clinical diagnosis applications. To improve the practicality of DBS sampling in clinical metabolomics, it is essential to identify which representative metabolites remain stable or unstable under various storage conditions, ensuring the scientific validity and accuracy of clinical studies.

In this study, we investigated the stability of metabolites in DBS samples stored under three different environmental conditions (4℃, 25℃, and 40℃) at various time points (3, 7, 14, and 21 days) using multi-platform untargeted metabolomics. We assessed the stability of identified metabolites in DBS samples by comparing the peak intensities of each time point at different temperatures against those in the controls (0 day). Our analysis yielded a comprehensive understanding of specific metabolites in DBS samples stored at different temperatures and durations, providing valuable insights for study design, standardizing biomarker selection, and improving data quality.

Results and discussion

Metabolites detection and identification of DBS samples

Metabolites are highly dynamic molecules that can degrade over time, especially when exposed to environmental factors such as diverse temperatures14,17,19. After home-based sampling, however, it is essential to recognize that during the transportation process from sample collection to mass spectrometry detection, DBS may encounter less than optimal conditions. Therefore, comprehensive understanding of metabolite stability from sample collection to analysis under adverse environmental conditions, such as 25 °C (mimicking the room temperature) and 40 °C, is necessary. Furthermore, Filippos et al. found that the DBS stored at room temperature exhibited poor stability over time, contrasting with relatively stable compositions observed at lower temperatures19. In addition, Trifonova et al. found that clinically relevant compounds such as creatine, glucose, carnitine, glutamine exhibited alterations of less than 15% (Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) < 15%) during four weeks of storage at room temperature18. However, these studies only provided annotations for a subset of metabolites, lacking extensive discussions on the stability of the large number of identified metabolites. To broaden the range of detectable metabolites, we employed both positive and negative modes UHPLC-MS and GC-MS-based multi-platform untargeted metabolomics, in conjunction with a method of extraction that separates hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds20. This comprehensive approach included metabolites of all polarities. Ultimately, we detected 1106 metabolic features, then we assigned 353 metabolites classified in subclasses, such as amino acids, carbohydrates, nucleotides, organic acids, peptides, ceramides, fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholines (LysoPCs), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LysoPEs), monoether phosphatidylcholines (MePCs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), sphingomyelins (SMs), triglycerides (TAGs), and Others (Table 1 and S1).

Table 1.

The number of metabolites identified as unstable in DBS samples following storage for 3, 7, 14, and 21 days at three different storage temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C).

| Metabolites subclass | Time comparison (Days) | Storge temperature (4 °C) | Storge temperature (25 °C) | Storge temperature (40 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | 0 vs. 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 4 (1.1%) | 12 (3.4%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 5 (1.4%) | 10 (2.8%) | 14 (4.0%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 1 (0.3%) | 11 (3.1%) | 18 (5.1%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 1 (0.3%) | 12 (3.4%) | 24 (6.8%) | |

| Carbohydrates | 0 vs. 3 | 4 (1.1%) | 13 (3.7%) | 16 (4.5%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 7 (2.0%) | 13 (3.7%) | 17 (4.8%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 8 (2.3%) | 17 (4.8%) | 20 (5.7%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 8 (2.3%) | 18 (5.1%) | 21 (5.9%) | |

| Nucleotides | 0 vs. 3 | 4 (1.1%) | 5 (1.4%) | 10 (2.8%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 3 (0.8%) | 3 (0.8%) | 10 (2.8%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 6 (1.7%) | 6 (1.7%) | 12 (3.4%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 1 (0.3%) | 6 (1.7%) | 13 (3.7%) | |

| Organic acids | 0 vs. 3 | 15 (4.2%) | 22 (6.2%) | 28 (7.9%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 16 (4.5%) | 23 (6.5%) | 28 (7.9%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 20 (5.7%) | 25 (7.1%) | 29 (8.2%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 19 (5.4%) | 28 (7.9%) | 36 (10.2%) | |

| Peptides | 0 vs. 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1.1%) | 5 (1.4%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 3 (0.8%) | 2 (0.6%) | 6 (1.7%) | |

| Ceramides | 0 vs. 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 7 (2.0%) | |

| Fatty acids | 0 vs. 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 6 (1.7%) | 6 (1.7%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 5 (1.4%) | 6 (1.7%) | 6 (1.7%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 3 (0.8%) | 6 (1.7%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 2 (0.6%) | 6 (1.7%) | 7 (2.0%) | |

| LysoPCs | 0 vs. 3 | 1 (0.3%) | 10 (2.8%) | 13 (3.7%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 1 (0.3%) | 18 (5.1%) | 16 (4.5%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 4 (1.1%) | 19 (5.4%) | 16 (4.5%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 2 (0.6%) | 20 (5.7%) | 16 (4.5%) | |

| LysoPEs | 0 vs. 3 | 4 (1.1%) | 7 (2.0%) | 7 (2.0%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 4 (1.1%) | 7 (2.0%) | 7 (2.0%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 5 (1.4%) | 7 (2.0%) | 7 (2.0%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 4 (1.1%) | 6 (1.7%) | 7 (2.0%) | |

| MePCs | 0 vs. 3 | 4 (1.1%) | 5 (1.4%) | 4 (1.1%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 4 (1.1%) | 4 (1.1%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 4 (1.1%) | 5 (1.4%) | 5 (1.4%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 4 (1.1%) | 6 (1.7%) | 5 (1.4%) | |

| PCs | 0 vs. 3 | 19 (5.4%) | 22 (6.2%) | 18 (5.1%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 19 (5.4%) | 20 (5.7%) | 19 (5.4%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 20 (5.7%) | 23 (6.5%) | 19 (5.4%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 22 (6.2%) | 22 (6.2%) | 29 (8.2%) | |

| PEs | 0 vs. 3 | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (5.9%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (5.9%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 21 (5.9%) | 21 (5.9%) | 22 (6.2%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 21 (5.9%) | 22 (6.2%) | 22 (6.2%) | |

| SMs | 0 vs. 3 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| TAGs | 0 vs. 3 | 20 (5.7%) | 38 (10.8%) | 38 (10.8%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 21 (5.9%) | 38 (10.8%) | 39 (11.1%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 26 (7.4%) | 40 (11.3%) | 39 (11.1%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 28 (7.9%) | 40 (11.3%) | 40 (11.3%) | |

| Others | 0 vs. 3 | 5 (1.3%) | 9 (2.5%) | 7 (2.0%) |

| 0 vs. 7 | 7 (2.0%) | 10 (2.8%) | 13 (3.7%) | |

| 0 v 14 | 8 (2.3%) | 12 (3.4%) | 14 (4.0%) | |

| 0 vs. 21 | 9 (2.5%) | 10 (2.8%) | 21 (5.9%) |

Effect of storage temperatures and durations

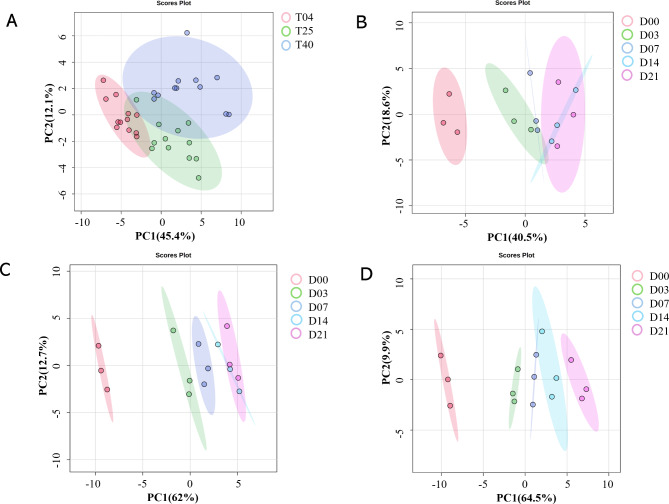

The data were analyzed by unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA), which showed the overall effect of storage temperatures. The scores plot generated from the PCA model distinctly illustrated the differentiation of DBS samples based on storage temperatures (Fig. 1A). In addition, the score plot derived from partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) also exhibited a clear separation among samples stored at different temperatures (Figure S1A). Furthermore, we explored the impact of storage durations on metabolite composition in DBS samples stored at different temperatures. We also performed a PCA to get a first overview on the data set (Fig. 1B–D). The PCA scores plot revealed that the samples from the same days formed distinct clusters, and the five clusters could be separated by the first principal component (PC1) at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively. As illustrated by the loading plots, the main factors driving the separation of the five clusters in the PC1 were PCs and TAGs (Figure S1B–D). Indeed, specifically PCs with carbon chain lengths of 34, 36, and 38, as well as TAGs with carbon chain lengths of 50 and 52, demonstrated markedly decreased metabolite intensities according to the storage times (Figure S2). During the same time period, notably increased metabolite intensities were observed for LysoPCs at 25 °C and 40 °C, which comprised the predominant species in the second principal component (PC2). These results suggest that the metabolic profiles can be distinguished based on storage temperatures, and significant time-dependent changes occurred in metabolite intensities.

Fig. 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) scores plot of the metabolomics data obtained from the DBS samples. (A) PCA score plot of the DBS samples stored at 4 °C (red), 25 °C (green), and 40 °C (blue). The T04, T25, and T40 mean the storage temperature of 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively. PCA scores plot of the metabolic profiling obtained from DBS samples following storage for 0 (red), 3 (green), 7 (dark blue), 14 (sky blue), and 21 (pink) days at 4 °C (B), 25 °C (C), and 40 °C (D), respectively.

Stability of DBS samples at different temperatures

Based on previously published studies, metabolites are deemed stable if the relative standard deviation (RSD) of each metabolite remains below 15% or 20% during storage18,21–22. To distinguish stable and unstable metabolites, we assessed changes in metabolite intensities relative to the reference (0 day), considering an RSD greater than 15% as indicative of instability (Table S1). We determined the counts of metabolites identified as unstable in DBS samples following storage for 3, 7, 14, and 21 days at three different storage temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C). The majority of metabolites remained stable, except for organic acids, PCs, TAGs, and PEs (Table 1). We observed that the alterations in these metabolites at each time point exceeded 4.2% regardless of temperatures, with TAGs exhibiting the most significant variation, exceeding 5.7%. At both 25 °C and 40 °C, we observed significant alterations in LysoPCs and carbohydrates, exceeding 4.5% over 7 days and 14 days, respectively. Studies have shown that PCs, TAGs, PEs, and LysoPCs often contain ester bonds and/or unsaturated bonds, making them susceptible to degradation under conditions, such as exposure to moisture, elevated temperatures, or suboptimal storage environments23,24. Furthermore, amino acids showed instability when stored at 40 °C for over 14 days. Studies have indicated that the instability of amino acids at elevated temperatures is primarily attributed to their propensity for complex chemical transformations, including pyrolysis, dehydration, oxidation, and polymerization. These reactions may alter the molecular structure of amino acids, significantly affecting their chemical properties and biological functionality25. Conversely, for other subclasses such as nucleotides, peptides, ceramides, fatty acids, LysoPEs, MePCs, and SMs, regardless of temperatures, the number of changes was less than 4%, indicating relative stability. Additionally, from 3 days to 21 days, there was no significant increase in quantity, all being less than 4%, suggesting that the number of unstable metabolites did not markedly change after 3 days.

Effect of storage times

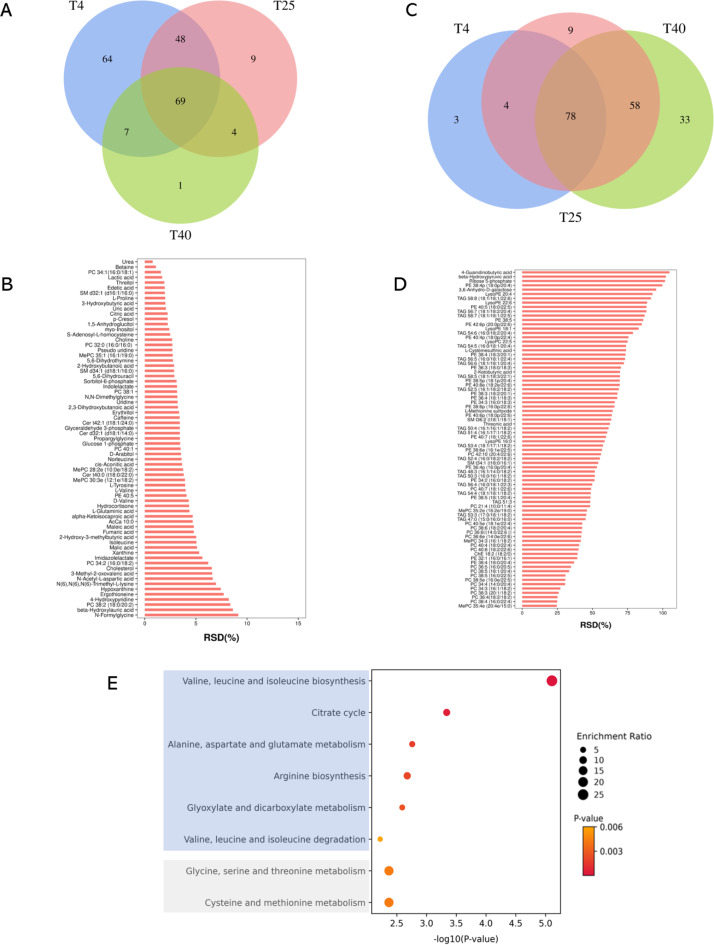

During 21 days of long-term storage, we found that the intensities of 188, 130, and 81 metabolites changed by less than 15% (RSD < 15%) at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively (Fig. 2A). Among them, sixty-nine out of 353 metabolites remained stable even when stored at three different temperatures (Fig. 2B). These included 15 (21.7%) lipids, 9 (13.0%) amino acids, 8 (11.6%) carbohydrates, 10 (14.5%) nucleotides, and 16 (23.2%) organic acids, respectively. These metabolites can be effectively utilized as biomarker candidates in biological functions. Furthermore, the remaining 61 metabolites exhibited stability at 25 °C and can serve as dependable metabolic molecules for disease risk assessment or prognosis evaluation (Figure S3A). If we consider that the typical shipping time is less than 3 days, extending the time criterion to 3 days would result in approximately 186 metabolites remaining stable at 25 °C (see Table S1). In contrast, we identified 85, 149, and 169 metabolites whose intensities changed by more than 15% regardless of the storage temperatures (Fig. 2C). Among them, 78 metabolites exhibited instability at all three different temperatures, comprising 69 (88.5%) lipids, 3 (3.8%) carbohydrates, and 5 (6.4%) organic acids, respectively (Fig. 2D). These results suggested that lipids are relatively unstable, and the aforementioned 78 metabolites should be excluded from consideration as biomarker candidates. Additionally, 71 metabolites showed instability at 25 °C and should also be avoided for biomarker purposes (Figure S3B).

Fig. 2.

The identification of stable and unstable metabolites. Venn diagrams of identified stable (A) and unstable (C) metabolites detected in DBS samples following storage for 3, 7, 14, and 21 days at three different storage temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C). The stability of metabolites was determined by comparing the relative standard deviation (RSD) of metabolite intensities at each time point against the reference (0 day), with an RSD less than 15% considered as stable. With the average of RSD values of each time point, the distribution of shared 69 stable (B) and 78 unstable (D) metabolites in DBS samples stored at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C were presented. (E) The metabolic pathways comprising with stable (blue) and unstable (gray) metabolites. The p-value of showed pathways is less than 0.01. The T4, T25, and T40 mean the storage temperature of 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively.

We also identified four clinically relevant compounds and obtained similar results18. For instance, the degradation of creatine initiated after 7 days in our dataset, consistent with their results. Additionally, the degradation of glucose and carnitine began after 7 days and steadily declined until the end of the 3-week period. Interestingly, previous studies have identified glutamine as the most stability-sensitive of the 23 amino acids, with significant degradation observed after three weeks of storage at room temperature16. In contrast, our findings reveal that glutamine stability was compromised as early as seven days under similar conditions, likely attributable to the activity of glutaminase13. We observed that certain cancer-associated metabolites, such as xanthine and hypoxanthine22.26,27, exhibited stability across diverse temperatures and storage periods, indicating their potential as promising biomarker candidates for cancer diagnosis. An even higher rate of degradation has been observed for carnitine and acetyl-carnitine across all storage temperatures28, which consistent with our findings. Similarly, our results indicate that lysoPCs exhibited a tendency toward degradation, aligning with earlier reports29.

From the stable and unstable metabolites, comprising 69 and 78 metabolites respectively, we selected those with HMDB IDs and conducted pathway enrichment analysis separately (Fig. 2E). We found that pathways related to valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis/degradation, citrate cycle, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, arginine biosynthesis, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism could be reliably analyzed using DBS samples. In contrast, pathways associated with glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, as well as cysteine and methionine metabolism, showed significant alterations, suggesting their unsuitability for pathway analysis.

Alteration of metabolite intensities according to the storage time

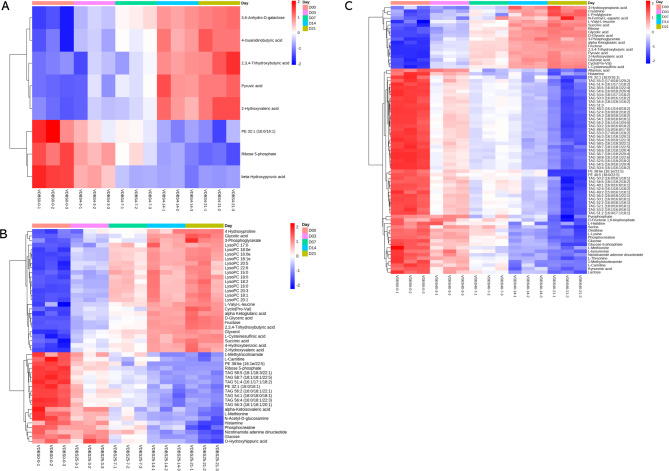

Given the variability already defined above, certain metabolites may be present a consistent trend of alteration in metabolite intensities. To assess this, we conducted linear correlation analysis based on storage time at each temperature. Employing a threshold of |R| ≧ 0.9, we identified a total of 8, 47, and 77 metabolites showing higher correlations at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively (see Table S1). All of these metabolites exhibited an RSD greater than 15% compared to the reference metabolite intensities for at least one day. Subsequently, we conducted heatmap analysis, which revealed that most metabolites exhibited gradual increases or decreases over time at three different storage temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C) (Fig. 3A–C). Notably, among them, 2,3,4-trihydroxybutyric acid, pyruvic acid, and 2-hydroxyvaleric acid showed gradual increases, yet displayed insignificant changes until 7 days later at 4 °C. Conversely, o-hydroxyhippuric acid, glucose, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, phosphocreatine, and alpha-ketoisovaleric acid presented the trends of decrement and exhibited insignificant changes until after 7 days at 25 °C. Interestingly, all types of PCs, PEs, and TAGs metabolites displayed a gradual decrease, in contrast to the increase observed in LysoPCs, indicating a propensity for degradation of PCs, PEs, and TAGs into LysoPC forms at 25 °C. Moreover, metabolites exhibiting R values below 0.9 and consistently maintaining an RSD below 15% across all time points, despite not demonstrating significant changes presently, could potentially undergo notable alterations with an extended time frame.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between metabolite intensity and storage duration. Heatmap shows the alteration of relative metabolite intensities of 8, 47, and 77 metabolites following storage for 3, 7, 14, and 21 days at temperature of 4 °C (A), 25 °C (B), and 40 °C (C), with a threshold of |R| ≧ 0.9, respectively. Columns represent the sample types. Red indicates high levels of metabolites, and blue indicates low levels of metabolites.

Conclusion

Blood, plasma, and serum, which collectively offer a comprehensive reflection of biological systems, have proven invaluable in providing mechanistic insights into the diagnosis of various clinical diseases and identifying potential metabolic biomarkers30. The logistical simplicity of DBS collection, storage, and transportation has led to a substantial rise in interest regarding the utilization of DBS in application of clinical diagnosis. The storage conditions of DBS samples may adversely affect the metabolite profiles, particularly for representative biomarker candidates, potentially impacting the reliability of DBS samples for clinical diagnosis applications. To improve the practicality of DBS sampling methods for clinical metabolomics, it is essential to identify which representative metabolites remain stable or unstable under different storage conditions, ensuring the scientific validity and accuracy of clinical studies. Therefore, studying the stability of metabolites and gaining a comprehensive understanding of the differences in metabolite levels in DBS samples stored at various temperatures, ranging from refrigerated to elevated temperatures, is crucial. In current study, DBS samples were obtained from the same participant to minimize biological variability. These samples were stored at three different temperatures (4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C) and extracted at four different time points: 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after storage, in order to evaluate the stability of metabolites over time. Ultimately, we detected 1106 features and identified 353 metabolites (see Table S1), encompassing nearly all classes of metabolites found in plasma. Furthermore, we observed that approximately 130 metabolites remained stable at 25 °C for the entire 21-day duration. These metabolites show potential as biomarker candidates for metabolomic clinical research. Our results offer valuable insights into the impact of pre-storage conditions on metabolite profiles, facilitating robust untargeted metabolomics studies using both novel and traditional micro-blood samples. In addition, stable metabolites can be confidently utilized in DBS-based metabolomics for clinical application, while unstable metabolites should be avoided. However, there are various limitations to this study. (1) The information provided regarding storage temperature and duration is inherently constrained by the metabolites that were measured. (2) It would be even better to have a DBS stored at −80 °C as a control at each time point. (3) Further investigation incorporated with desiccants is essential to determine whether the degradation of metabolites in DBS is caused by residual moisture.

Overall, our study provided a thorough understanding of specific metabolites in DBS samples stored at different temperatures and durations. To our knowledge, this study is the first comprehensive investigation into the detailed stability of hundreds of metabolites under varying storage conditions. Nevertheless, this study will offer valuable insights for study design, standardizing biomarker selection, and enhancing data quality.

Materials and methods

Chemical and reagents

MS-grade methanol, acetonitrile (ACN), formic acid, water, ammonium acetate, and HPLC-grade methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC-grade isopropanol (IPA) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Whatman 903TM protein saver cards, utilized for DBS sample preparation, were obtained from Whatman (Maidstone, UK). The internal standards, including gibberellic acid A3, 13C sorbitol, and PE (17:0/17:0) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Sample preparation

For the DBS storage stability study, samples were all collected from a single individual simultaneously to minimize any potential biological variability. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and the informed consents were obtained from the participant. Venipuncture was conducted on the subject’s cubital vein under the fasting condition. Following collection, 50 µL of whole blood was promptly transferred onto Whatman 903TM protein saver cards. Subsequently, all samples underwent complete air drying for four hours at room temperature. The DBS paper cards were then individually enclosed in zip-closure foil bags and stored at temperatures of 4℃, 25℃, and 40℃ for durations of three days, one week, two weeks, and three weeks. To ensure robustness and reliability, triplicate samples were collected for each temperature and time interval. Furthermore, control samples were obtained at the initial time point (0 day) and stored at -80℃. Additionally, samples were collected on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days from each storage temperature. DBS samples retrieved at each time point were preserved at -80℃ until analysis throughout the study.

Sample extraction

For each specified time point (3, 7, 14, and 21 days) and temperature (4℃, 25℃, and 40℃), samples were retrieved from their respective storage environments and promptly preserved at -80℃ until analysis. DBS underwent processing by excising four dried blood slices, each with a diameter of 3 mm from a single dried spot, which were then directly transferred into individual microcentrifuge tubes. DBS samples were extracted as previously reported31. In brief, DBS slices were mixed with 700 µL MTBE buffer containing 0.45 µg/mL of gibberellic acid A3, 1 µg/mL of 13C sorbitol, and 0.45 µg/mL of PE (17:0/17:0) as internal standards. Gibberellic acid A3 and PE (17:0/17:0) were relatively used as the internal standard of hydrophilic and lipophilic phase detection LC-MS platform. In addition, 13C sorbitol was applied for GC-MS platform. Internal standards were utilized to monitor the stability of extraction and the on-board process of the MS platform. The coefficient of variation (CV) for each substance less than or equal to 20% was considered as stable. Then, the samples were sonicated for 15 min in a 4 °C bath. Subsequently, 350 µL solution (methanol/water, v/v, 1:3) was added to facilitate phase separation. The upper lipophilic phases and lower hydrophilic phases were separated by high-speed centrifugation (12,700 rpm, 5 min at 4 °C, Centrifuge 5430R, Eppendorf, Germany). Next, 400 µL of the lower hydrophilic phase was further mixed with 1.1 mL of methanol, incubated at 4 °C for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 12,700 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The upper phase containing the lipophilic phase (350 µL) was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube for lipid analysis. The hydrophilic phase was divided into two microcentrifuge tubes, one containing 350 µL and the other containing 1000 µL, intended for GC-MS and UHPLC-MS metabolite analysis, respectively. All aliquots were dried using a speed vacuum concentrator and stored at -80 °C. Before use, the dried samples of lipophilic and hydrophilic constituents were dissolved in 200 µL of ACN/IPA (v/v, 7:3) and water, respectively. Finally, they were transferred into sample vials for further analysis. To ensure measurement quality and equipment performance, three types of quality control (QC) samples were prepared according to the aforementioned procedure. These included a pooled sample consisting of 50% randomly selected DBS samples (QCbio), a mixture of chemical standards (QCmix), and a sample containing only solvents (QCblank). To identify impurities in the solvents or contamination in the separation system, the analytical batch run began with a QCblank. QCmix and QCbio samples were inserted after every ten biological samples during analysis.

Sample detection by GC-MS and UHPLC-MS

The derivatization of the dried hydrophilic metabolites was performed according to Lisec et al.32. Briefly, the dried fractions were oximilised by methoxyammonium pyridine solution and derivatized by adding MSTFA for GC-MS analysis. The analysis of derivatization of the hydrophilic metabolites was conducted utilizing an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph with an Rxi®-5SilMS GC column (30 m, 0.25 × 30 mm, 0.25 μm), coupled to time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (Leco Corp., St. Joseph, MI, USA) with an electron ionization source by an Agilent 7683 series autosampler (Agilent Technologies GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany). High-purity helium was set as carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The temperature was initially set at 50 °C for 2 min, and then reaching 330 °C at a rate of 1 °C per minute. The ion source temperature and interface were set at 250 °C and 280 °C, respectively. The detector voltage and electron energy were set at 1.2KV and 70 eV, respectively.

The analysis of lipophilic and hydrophilic extractions was performed using an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC, Waters ACQUITY (Milford, MA, USA) ) system coupled to Thermo-Fisher Q-Exactive (Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometers with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source under both positive and negative modes. For lipophilic samples, a BEH C8 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) was used for chromatographic separation with a column temperature of 60 °C. Gradient elution was performed using a mobile phase A water and B ACN/IPA (70/30, V/V), both containing 0.1% acetic acid and 0.1% ammonium acetate at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The optimal gradient elution program was set as follows: 55% B at 0–1 min, 75% B at 4 min, 89% B at 12 min, 100% B at 12 min, 100% B at 19.5 min, 55% B at 19.51 min, 55% B at 24 min. The injection volume of the sample was set at 2 µL with a temperature held at 10 °C. For hydrophilic samples, chromatographic separations were performed on a HSS T3 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) with a column temperature of 40 °C. Gradient elution was carried out using mobile phase A water and B ACN, both containing 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The gradient elution program was operated as follows: 1% B at 0 min, 70% B at 13 min, 99% B at 13.01 min, 99% B at 18 min, 1% B at 18.01 min, and 1% B at 22 min. The injection volume of the sample was set at 3 µL with the temperature held at 10 °C. For both lipophilic and hydrophilic metabolite analyses, full scan and data-dependent acquisition (DDA) were employed to acquire MS and MS/MS spectra. Full scanning analyses were performed in the range of m/z 100–1500 Da. The DDA was carried out for targeting the top five most intense precursor ions for MS/MS analysis in the pooled DBS samples (QCbio) with the scan ranges of m/z 100 − 310 Da, 300 − 710 Da, and 700 − 1500 Da, respectively. The operating conditions of the mass spectrometer were as follows: 3500 V in positive mode and 3000 V in negative mode of ion spray voltage, 20 psi nebulizer, 400 sheath gas temperature, 10 L/min sheath gas flow, and 30 V normalized collision energy was used for MS/MS20. Each sample was injected three times, and the average intensity was used to represent the relative intensity of the metabolites.

Data processing and analysis

The raw data acquire by GC-MS was first analyzed by using Leco ChromaTOF (version 5.40). Target Search of Bioconductor package in R (version 4.0.3) was used for peak detection, fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) based retention time, and mass spectral comparison with the Fiehn reference libraries33. The identification of metabolite was further confirmed using manual inspection of chromatograms.

UHPLC-MS chromatograms were processed by using Metanotitia Inc. in-house developed software PAppLineTM, supplemented by commercial software including Compound Discoverer 3.1 and LipidSearch (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The first processing step was including peak detection, peak filtering, baseline correction and removing isotopic peaks34. The lipids and metabolites were annotated based on the retention time, precursor ion and product ions fragmentation pattern by using the Metanotitia Inc. library, UlibMS. In detail, the establishment of metabolite database via a sub-library of six thousand compounds, which were developed according to same chromatographic and spectrometric conditions as the measured samples, and the lipids were annotated with a sub-library of 1,700 lipids based on the precursor m/z, fragmentation spectrum, and elution patterns20. The matching criteria were retention time within of 0.2 min and mass accuracy lower than 10 ppm. Then, the features that were detected in less than 60% of the DBS samples were remove for further analysis. The missing values were imputed by using Mice random forest algorithm according to the sample type and peak intensity34. Finally, a calibration procedure including logarithm transformation and scaling was performed.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate statistical analysis was performed by using MetaboAnalyst 6.0. (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). A log transformation based on 10 and pareto scalling were implemented to generate “Principal component analysis” (PCA) and “Partial least squares discriminant analysis” (PLS-DA) models. The stability of metabolites was determined by comparing the relative standard deviation (RSD) of metabolite intensities at each time point against control samples collected on Day zero, with an RSD less than 15% indicating stability. Conversely, the variability of RSD exceeding 15% was deemed unstable. The statistical analysis and Spearman correlation analysis of metabolites were performed to investigate the differences of metabolites by using Python software. The Venn and Barplot diagrams were generated using OmicStudio tools (https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool). The violin plot was generated using Hiplot tool (https://hiplot.cn/ ). Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) heatmap analysis was conducted with MetaboAnalyst 6.0 using Euclidean distance measurement method and Ward clustering method to display the relative intensity changes of metabolites. Additionally, pathway enrichment analysis was also employed to further elucidate the characteristics of stable or unstable metabolites using MetaboAnalyst 6.0, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the volunteer who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- DBS

Dried blood spot

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- MTBE

Methyl tert-butyl ether

- IPA

Isopropanol

- UHPLC-MS

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- GC-MS

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- FAME

Fatty acid methyl esters

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PC1/2

First/second principal component

- PLS-DA

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- RSD

Relative standard deviation

- HCA

Hierarchical cluster analysis

- PCs

Phosphatidylcholines

- PEs

Phosphatidylethanolamines

- TAGs

Triglycerides

- LysoPCs

Lysophosphatidylcholines

- LysoPEs

Lysophosphatidylethanolamines

- MePCs

Monoether phosphatidylcholines

- SMs

Sphingomyelins

- AcCa

Acetyl-coA carboxyltransferase α

- TOF

Time-of-flight

Author contributions

L.L., Y.L. and H.W. were responsible for the design of this work. HN.C., F.S., and G.H. were responsible for sampling, data acquisition, and metabolic assignments. S.Y. were responsible for data processing. HN.C., Y.H., and H.W. contributed data analysis and data interpretation. H.W., and Y.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript editing and revision. All authors approved the submission of the final manuscript for publication. All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and the informed consents were obtained from the participant. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yan Li, Email: yan.li@metanotitia.com.

He Wen, Email: he.wen@metanotitia.com.

References

- 1.Pang, H., Jia, W. & Hu, Z. Emerging applications of metabolomics in clinical pharmacology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.106 (3), 544–556 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin, J. R. et al. Metabolomic biomarkers in blood samples identify cancers in a mixed population of patients with nonspecific symptoms. Clin. Cancer Res.28 (8), 1651–1661 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthrie, R. & Susi, A. A simple phenylalanine method for detecting phenylketonuria in large populations of newborn infants. Pediatrics32 (3), 338–343 (1963). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puck, J. M. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency and T-cell lymphopenia. Immunol. Rev.287 (1), 241–252 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr, D. B. et al. The use of dried blood spots for characterizing children’s exposure to organic environmental chemicals. Environ. Res.195, 110796 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen, G. et al. Precision sirolimus dosing in children: the potential for model-informed dosing and novel drug monitoring. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1126981 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polo, G. et al. Plasma and dried blood spot lysosphingolipids for the diagnosis of different sphingolipidoses: a comparative study. CCLM57 (12), 1863–1874 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrick, L. et al. Untargeted metabolomics of newborn dried blood spots reveals sex-specific associations with pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res.106, 106585 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao, G. et al. A metabolomic study for chronic heart failure patients based on a dried blood spot mass spectrometry approach. RSC Adv.10 (33), 19621–19628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catanese, S. et al. Biomarkers related to fatty acid oxidative capacity are predictive for continued weight loss in cachectic cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 12 (6), 2101–2110 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirev, P. A. Dried blood spots: analysis and applications. Anal. Chem.85 (2), 779–789 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn, W. B. et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc.6 (7), 1060–1083 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice, P., Turner, C., Wong, M. C. & Dalton, R. N. Stability of metabolites in dried blood spots stored at different temperatures over a 2-year period. Bioanalysis5 (12), 1507–1514 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer, E. A., Cooper, H. J. & Dunn, W. B. Investigation of the 12-month stability of dried blood and urine spots applying untargeted UHPLC-MS metabolomic assays. Anal. Chem.91 (22), 14306–14313 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrick, L. M. et al. Effects of storage temperature and time on metabolite profiles measured in dried blood spots, dried blood microsamplers, and plasma. Sci. Total Environ.912, 169383 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dijkstra, A. M. et al. Important lessons on long-term stability of amino acids in stored dried blood spots. Int. J. Neonatal Screen.9 (3), 34 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottosson, F. et al. Effects of long-term storage on the biobanked neonatal dried blood spot metabolome. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom.34 (4), 685–694 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trifonova, O. P., Maslov, D. L., Balashova, E. E. & Lokhov, P. G. Evaluation of dried blood spot sampling for clinical metabolomics: effects of different papers and sample storage stability. Metabolites9 (11), 277 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michopoulos, F., Theodoridis, G., Smith, C. J. & Wilson, I. D. Metabolite profiles from dried blood spots for metabonomic studies using UPLC combined with orthogonal acceleration ToF-MS: effects of different papers and sample storage stability. Bioanalysis3 (24), 2757–2767 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi, Z. et al. A comprehensive mass spectrometry-based workflow for clinical metabolomics cohort studies. Metabolites12 (12), 1168 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong, S. T., Lin, H. S., Ching, J. & Ho, P. C. Evaluation of dried blood spots as sample matrix for gas chromatography/mass spectrometry based metabolomic profiling. Anal. Chem.83 (11), 4314–4318 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zelena, E. et al. Development of a robust and repeatable UPLC - MS method for the long-term metabolomic study of human serum. Anal. Chem.81 (4), 1357–1364 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams, D. E., Kathryn, B. & Grant Metal-assisted hydrolysis reactions involving lipids: a review. Front. Chem.7, 14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortensen, M. S. & Ruiz, J. Watts. Polyunsaturated fatty acids drive lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Cells12 (5), 804 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss, I. M. et al. Thermal decomposition of the amino acids glycine, cysteine, aspartic acid, asparagine, glutamic acid, glutamine, arginine and histidine. BMC Biophys.11, 1–15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long, Y. et al. Global and targeted serum metabolic profiling of colorectal cancer progression. Cancer123 (20), 4066–4074 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong, E. S. et al. Metabolic profiling in colorectal cancer reveals signature metabolic shifts during tumorigenesis. MCP. 1–42 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Strnadova, K. et al. Long-term stability of amino acids and acylcarnitines in dried blood spots. Clin. Chem.53 (4), 717–722 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haid, M. et al. Long-term stability of human plasma metabolites during storage at -80 ℃. J. Proteome Res.17 (1), 203–211 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sotelo-Orozco, J., Chen, S. Y., Hertz-Picciotto, I. & Slupsky, C. M. A comparison of serum and plasma blood collection tubes for the integration of epidemiological and metabolomics data. Front. Mol. Biosci.8, 682134 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song, G. et al. Circulating metabolites as potential biomarkers for the early detection and prognosis surveillance of gastrointestinal cancers. Metabolomics19 (4), 36 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lisec, J., Schauer, N., Kopka, J., Willmitzer, L. & Fernie, A. R. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry–based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc.1 (1), 387–396 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuadros-Inostroza, Á. et al. TargetSearch-a Bioconductor package for the efficient preprocessing of GC-MS metabolite profiling data. BMC Biophys.10, 1–12 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doove, L. L., Van Buuren, S. & Dusseldorp, E. Recursive partitioning for missing data imputation in the presence of interaction effects. Comput. Stat. Data Anal.72, 92–104 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.