Abstract

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (EC) is one of the most common malignancies in the female reproductive system, characterized by tumor heterogeneity at both radiological and pathological scales. Both radiomics and pathomics have the potential to assess this heterogeneity and support EC diagnosis. This study examines the correlation between radiomics features from Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps and post-contrast T1 (T1C) images with pathomic features from pathology images in 32 patients from the CPTAC-UCEC database. 91 radiomics features were extracted from ADC maps and T1C images, and 566 pathomic features from cell detections and cell density maps at four different resolutions. Spearman’s correlation and Bayes Factor analysis were used to evaluate radio-pathomic correlations. Significant cross-scale correlations were found, with strengths ranging from 0.57 to 0.89 in absolute value (9.47 × 104 < BF < 4.77 × 1014) for the ADC task, and from 0.64 and 0.70 (1.80 × 104 < BF < 5.69 × 105) for the T1C task. Most significant and high cross-scale associations were observed between ADC textural features and features from cell density maps. Correlations involving morphometric features and ADC and T1C first-order features were also observed, reflecting variations in tumor aggressiveness and tissue composition. These findings suggest that correlating radiomic features from ADC and T1C features with histopathological features can enhance understanding of EC intratumoral heterogeneity.

Keywords: Uterine corpus, Endometrial carcinoma, Pathomics, Digital pathology, Radiomics, MRI

Subject terms: Endometrial cancer, Image processing, Oncology

Introduction

Endometrial Carcinoma (EC) of uterine corpus is one of the most prevalent gynaecologic malignancies. It is often diagnosed at an early stage due to atypical uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Tumor stage, histologic grade, tissue invasion, and lymph node metastasis are critical EC prognostic indicators1,2. Uterine corpus EC exhibits both inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity at both radiological and histopathological scales, which manifests as variations in with histologic types differing in their morphology, cellular components, and molecular features3. Heterogeneity is an important biological characteristic of malignant tumors and manifests as inconsistencies in tumor cell density, microvascular density, cell proliferation and apoptosis. Tumor heterogeneity occurs due to changes in the lesion microenvironment caused by mutations in malignant oncogenes, which not only lead to unrestrained cell proliferation and apoptosis but also to the appearance of abnormal vascular structures4. Tumor heterogeneity may have important clinical implications, influencing diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic management for patients with EC3. Although surgery and biopsy are the standard techniques for staging EC, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) plays a key role in the disease evaluation. It is the preferred imaging modality for treatment planning, as it allows a better evaluation of the aggressiveness of EC especially in the preoperative phase, investigating the myometrial and cervical invasion and the identification of distant metastases5–7. In particular, multiparametric MRI combines sequences such as T2-weighted images, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and dynamic-enhanced contrast (DCE) for diagnosis, staging, assessment of response to treatment, and prognosis of EC. T2-weighted MRI allows an optimal depiction of the uterus anatomy and for myometrial invasion. The use of DWI increases the diagnostic accuracy for tumor research, myometrial and cervical stromal invasion and it shows the presence of small peritoneal implants. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps differentiate EC from normal endometrium and polyps thanks to the low ADC values, providing valuable suggestions for tumor aggressiveness. The DCE adds perfusion features to the assessment, including the arterial phase, which is useful for the subendometrial enhancement analysis as it enhances earlier than background myometrium; equilibrium phase which shows invasion of the myometrium as the contrast agent is maximal and the lesion presents a hypointense signal compared to the background myometrium; delayed phase that evaluates cervical stromal invasion 8.

Although several studies suggested that ADC and DCE can play a valuable role in EC diagnosis, staging, assessment of response to treatment, and prognosis2,9, the high EC intratumoral heterogeneity often constitutes a strong limitation for these imaging techniques, resulting in a poorer prognosis. Moreover, the relationships with underlying physio-pathological mechanisms are not always fully understood, which is a crucial step to understand EC heterogeneity.

Radiomics is an emerging field of medicine focused on extracting large amounts of numerical descriptors from standard radiologic images. These features, such as shape, texture, and intensity, provide a detailed description of tumor characteristics that go beyond what is visible to the human eye10,11. By transforming standard medical images into a rich dataset of quantitative descriptors, radiomics provides a deeper insight into intratumoral heterogeneity, which can influence diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response. One of the primary goals of radiomics is to create predictive models that can categorize patients based on their likely clinical outcomes. This process involves linking the extracted imaging features to clinical data, histopathology, or molecular characteristics. Machine learning techniques are often used to build these models, enabling the classification of tumors into risk groups or predicting patient responses to therapies. In this way, radiomics serves as a non-invasive tool to uncover biological information, often described as a “virtual biopsy”, offering a detailed view of the tumor’s structure and function without the need for invasive sampling10.

While radiomics operates on a macroscopic level compared to genomics or histological markers, it remains an effective indicator of intratumoral heterogeneity12–14.

Current radiomics studies in the EC field have shown promising results in demonstrating correlations between MRI features and EC diagnosis, molecular characteristics, and prognoses15–19.

However, correlating these MRI features with underlying histopathology presents challenges20.

A compelling approach to relate radiomic results to tumor pathologic findings relies on quantitative analysis of digitized histopathology images21. On a microscopic scale, the emerging and rapidly expanding field of pathomics aims to apply high-throughput image feature extraction techniques to interrogate the microscopic patterns in pathologic data, especially from hematoxylin–eosin–stained Sects. 22,23. The extracted features serve as the foundation for model building, where advanced algorithms, such as machine learning and deep learning models, are employed to discern patterns, classify tissue types, and predict diagnostic outcomes. Common examples of pathomics applications include spatial characterization of tumor and stromal regions, shapes and textures of nuclei, classifications of cell types22. By analyzing microscopic features, pathomics provides a deeper understanding of tumor biology on a cellular level, complementing the macroscopic insights provided by radiomics22.

Several studies have explored the application of pathomics in EC, utilizing both handcrafted methods and deep learning techniques24–26.

Because of the close similarity of the radiomic and pathomic approaches, the radiomic features from in vivo images may be compared with the pathomic features extracted from histopathological images, often benefiting from a clearer biological definition of the image patterns and hence a better understanding of the features.

MRI and digital pathology offer complementary information about the tumor, prompting the question of whether radiomics and pathomics features are related.

Integrating data from these different imaging scales holds the promise of enhancing diagnostics and expanding molecular knowledge of EC, with significant implications for clinical decision-making. Radiomics and pathomics could address the need to assess the tumor heterogeneity that characterizes EC, and their integration could validate the radiomic approach as a “virtual biopsy” in clinical practice10,27.

As previously highlighted, it has been shown that both radiomic and pathomic image-based signatures can independently predict outcomes of interest in EC17,24,28.

Some previous studies investigated the correlation between MRI-based features and histopathological findings, although not performing a quantitative histopathological analysis1,5,29.

However, there are no studies that have explored the associations between MRI images of EC patients and features arising from histopathologic images.

To address this gap, the present study explores whether radiomics features extracted from preoperative ADC maps and post-contrast T1 (T1C) images correlate with pathomic features derived from histological images of EC patients. In particular, we focused on functional MRI images such as ADC and post-contrast T1C images since they are expected to be more closely related to the microscopic characteristics of the tumor, such as cellularity and vascularity, compared to purely morphological MRI images. In fact, ADC maps are particularly valuable as they reflect the diffusion of water molecules within tissues, which is indicative of cellular density and the integrity of cellular membranes, thus providing insights into tumor cellularity and structure30,31. In addition, T1C images highlight areas of increased vascularity and perfusion, which can reveal information about tumor angiogenesis and vascular characteristics32,33.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori “Fondazione G. Pascale (protocol number 6/22). The subjects used for the study belong to the public database Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium-Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma (CPTAC-UCEC), accessed in April 2024 (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cptac-ucec/). Informed consent of patients in the CPTAC cohorts was acquired for the provision of biospecimens and data. Radiology images, clinical data, digital histopathology slides, and associated quantified features (cellularity, necrosis, tumor nuclei, age, tumor weight) of samples included were downloaded from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA).

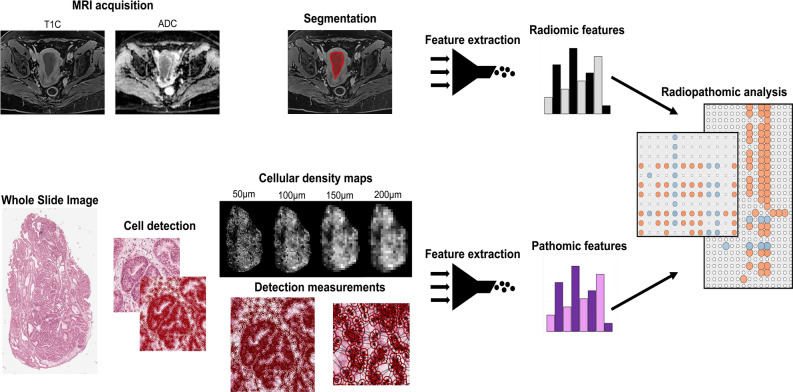

The inclusion criteria for this study were: the availability of pretreatment T1C images and ADC maps, availability of corresponding digital pathology whole-slides images (WSI), WSI slides with at least 80% of tumor nuclei and 50% of tumor cellularity, and at most 10% necrosis. Moreover, patients were excluded if i) the quality of MRI was insufficient to perform imaging analysis and/or obtain measurements, ii) the quality of WSI did not meet diagnostic standards (e.g. due to tissue folds or torn tissue), or iii) images had a positive value of Clinical Trial Time Point ID (which refers to the number of days from the patient’s was initial pathological diagnosis to the date of the scan). Finally, a total of 32 subjects met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Refer to Fig. 1 for an example of EC MRI radiology (ADC and T1C) and digital pathology images, and to Table 1 for the clinical characteristics and outcomes of included patients. Demographic, genomic, and other clinical features of these patients were published in Duo et al.34.

Fig. 1.

Example of Endometrial Carcinoma (EC) located in anterior endometrium. (A) In the delayed phase of DCE (dynamic contrast enhanced) Magnetic Resonance images, the EC (red arrow) was low in signal compared to the enhancing myometrium; (B) the lesion on the axial ADC (apparent diffusion coefficient) map showed a hypointense signal (red arrow). (C) histological slide of G2 (grade) EC in FFPE (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded) (percent tumor nuclei: 90; percent total cellularity: 90; percent necrosis: 0).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of the included patients.

| Clinical and pathologic characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Progression/Recurrence [n (%)] | |

| Y | 7 (21,8) |

| N | 21 (65,6) |

| NR | 4 (12,5) |

| Grade [n (%)] | |

| G1 | 5 (15,6) |

| G2 | 16 (50) |

| G3 | 10 (31,2) |

| AJCC Pathologic Stage | |

| Stage I | 19 (59,3) |

| Stage II | 5 (15,6) |

| Stage III | 4 (12,5) |

| Stage IV | 2 (6,2) |

| Stage IVB | 1 (3,1) |

| AJCC Pathologic T | |

| T1a | 14 (43,7) |

| T1b | 6 (18,7) |

| T2 | 5 (15,6) |

| T3a | 2 (6,2) |

| T3b | 3 (9,3) |

| T4 | 1 (3,1) |

| AJCC Pathologic N | |

| NX | 3 (9,3) |

| N0 | 22 (68,7) |

| N1 | 3 (9,3) |

| N2 | 3 (9,3) |

| AJCC Pathologic M | |

| MX | 2 (6,2) |

| M0 | 27 (84,3) |

| M1 | 2 (6,2) |

The total of the various pathological characteristics is not equal to 100, as patients who do not have the reported data have been omitted.

Y Yes, N No, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, T Tumor, N Nodes, M Metastasis.

MRI acquisition and processing

A 1.5 T SIEMENS MR scanner was used to perform MRI, and EC images were acquired with a protocol including: i) coronal, axial and sagittal T2W turbo spin echo images (TR/TE, 3660–9820/98–119 ms; slice thickness, 4–8 mm, FOV, 256 × 256 or 320 × 320); ii) axial and sagittal T1W fat suppression TSE (TR/TE, 160–625/3.16–7.4 ms; slice thickness, 4–8 mm; FOV, 256 × 256–430 × 320); iii) axial or sagittal DCE (dynamic contrast enhanced) (TR/TE, 4.35–4.78/2.1–2.39 ms; slice thickness, 2–4.6 mm; FOV, 312 × 224 or 512 × 512), obtained using the 3D fat-suppressed gradient-echo (GRE) T1W sequence after intravenous administration of 14–22 ml of gadolinium contrast agent and with the dynamic sequence consisting of a precontrast image followed by images acquired at 20, 60, 120, 180, and 240 s after contrast agent injection; iv) DWI (TR/TE, 3200–6000/71–62 ms; slice thickness, 4–6 mm; FOV, 162 × 108- 256 × 256 and b-values were 50, 400, 800 and 1200 s/mm2). Automatic creation of ADC maps was carried out on the post-processing workstation.

MRI acquisitions were converted from DICOM format to NIfTI format using ITK-SNAP (version 4.2.0-alpha.3, http://www.itksnap.org). Prior to segmentation, all images were carefully reviewed by a radiologist with 8 years of experience for the presence of critical artifacts, including those caused by gastrointestinal peristalsis or contractions, to ensure only high-quality images were used for analysis. Using the same software, the radiologist then manually delineated the VOIs (volumes of interest) with the round brush shape tool, slice by slice, on the axial plane acquired in late phase T1C, with the possibility of examining the extension of the EC on the coronal and sagittal images. Subsequently, the segmentations were also applied on the registered ADC maps. During segmentation, the sequences examined were compared to high b-value DWI (1200 s/mm2) and T2-weighted images in order to accurately and completely delineate EC. In these acquisitions tumor presented an intermediate SI (signal intensity) on T2-weighted images, a high SI on DWI, while on the respective ADC maps the lesion was as an area of hypointensity.

WSI acquisition and processing

H&E-stained formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues obtained from surgical resection of primary tumors were utilized for pathological examination. Subsequently, the slides were digitized into SVS format at 20 × magnification, with a resolution of 0.494 μm per pixel. A comprehensive manual inspection of all WSIs was conducted to identify and exclude any of them with artifacts. Artifact-free WSIs without any preprocessing were imported in QuPath digital pathology software. A clinical expert delineated regions containing the largest feasible tissue area characterized by viable tissue displaying vivid histopathological features and without artifacts34,35.

Pathomic workflow

Pathomic features extraction

Two feature groups were extracted to perform pathomic analysis, namely those extracted by each nucleus of WSIs (detection measurements), and features derived from cell density maps at four different resolutions (50 μm, 100 μm, 150 μm, 200 μm).

Detection measurements

The H&E-stained WSIs of H&E-stained slides were processed using QuPath digital pathology software36 for cell and nuclear segmentation. The segmentation was carried out by applying the cell detection function within the software’s analysis module. Nuclear segmentation utilized watershed cell detection37,38, which was guided by specific segmentation parameters including the morphological characteristics of cells, nuclei, and cytoplasm. Hematoxylin Optical Density (OD) was set as setup parameter for detection image, with pixel size of 0.5 μm. For nucleus parameters, the background radius and sigma were set as 8 and 1.5 μm, respectively. For intensity parameters, the threshold was set as 0.1 and the max background intensity was set as 2. Other parameters were set as their respective default values. The quality of the automated cell detection was checked by an expert microscopist.

Detection measurements including shape characteristics, Haralick texture features39 from different channels/color transforms (Optical Density Sum -ODSum-, Haematoxylin, Eosin, Red, Green, Blue, Hue, Saturation, and Brightness), and Delaunay triangulation measurements40 were calculated for all detections. The following parameters were used to extract intensity features: preferred pixel size = 2 μm, region = ROI, tile diameter = 25 μm, Haralick distance = 1, Haralick number of bins = 32. and spatial analysis. A distance threshold of 0 μm was set for Delaunay triangulation measurements calculation.

A total of 202 features were measured for each detection on the candidate slide (as detailed in Supplementary Table S1) and exported into a tab-delimited file via a custom QuPath script. These detection measurements were aggregated at the case level by averaging the values across tiles. For patients with multiple slides, feature values were averaged across the WSIs. Additionally, annotation metrics such as WSI-selected area, nuclei count, extracellular area, total cytoplasm, and extracellular area were also computed. The nuclear segmentation and feature extraction process was facilitated through Groovy scripts executed within the QuPath script editor, and the resulting data was imported into R version 3.4.2 for subsequent statistical analysis.

Cell density maps measurements

Cell density maps corresponding to regions of interest (ROIs) on WSIs were generated at varying resolutions (50 μm, 100 μm, 150 μm, and 200 μm). Cellular density within each tile, corresponding to the chosen resolution, was calculated by analyzing the segmented nuclei, with each tile assigned a gray level reflecting the number of nuclei it contained. This process produced a spatial map of cellular density across the digitized histopathology for each resolution. A total of 91 features were extracted from these cell density maps using PyRadiomics [https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/] (Supplementary Table S1). For patients with multiple slides, the feature values were averaged across the WSIs.

Radiomic workflow

Before extracting radiomic features, T1C image intensities were normalized by centering them around their mean value and scaling them using the standard deviation of all gray values in the original image. Ninety-one radiomic features were extracted from the segmented VOIs in the enhanced regions of T1C and ADC maps using the open-source Python package PyRadiomics (https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/Latest/). These features were divided into two categories: 18 first-order features, representing intensity statistics, and 73 multi-dimensional texture features. The texture features included 23 from the gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), 16 from the gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM), 16 from the gray level run length matrix (GLRLM), 14 from the gray level dependence matrix (GLDM), and 5 from the neighboring gray tone difference matrix (NGTDM). These features are detailed in Supplementary Table S2, with feature algorithms available at https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/features.html.

Radiopathomic analysis

A comprehensive study design was established to assess the potential correlations between radiomic and pathomic features in the patient cohort. The workflow is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Radiopathomic workflow implemented in the study. Abbreviations: ADC = Apparent Diffusion Coefficient; T1C = post-contrast T1 images.

A preliminary analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the mean ADC and basic histopathologic features associated with cellular density, including nuclei count, extracellular space area, and the combined area of extracellular space and cytoplasm. These features were normalized to the regions analyzed within the WSI.

A more in-depth radiopathomic correlation analysis followed, investigating associations between the extracted pathomic and radiomic features mentioned earlier. The analysis was performed separately for ADC and T1C images.

Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between radiomic features and pathomic features. The ρ was calculated between the selected ADC radiomic features and the pathomic features that remained after the correlation filtering. The same process was applied to T1C radiomic features. p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method, with a significance threshold set at an FDR-adjusted p-value (q-value) below 0.05. The correlation strength was categorized as very weak if |ρ|= 0.00–0.19, weak if |ρ|= 0.20–0.39, moderate if |ρ|= 0.40–0.59, strong if |ρ|= 0.60–0.79, and very strong if |ρ|= 0.80–1.0041.

To complement the correlation analysis, Bayes Factors were estimated to quantify the evidence for or against the null hypothesis42. The Bayes Factor, expressed as the logarithm of the ratio of the likelihoods for the experimental and null hypotheses, indicated substantial evidence when the absolute log Bayes Factor exceeded 0.5, and strong evidence when it exceeded 142,43.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2.

Results

Preliminary analysis of ADC mean value and basic histopathological features revealed moderate but significant negative correlations between ADC and nuclei area (ρ = -0.433, p = 0.0133), and weak but significant positive correlations with extracellular space area (ρ = 0.369, p = 0.0363) and the sum of extracellular space and cytoplasm (ρ = 0.374, p = 0.0349).

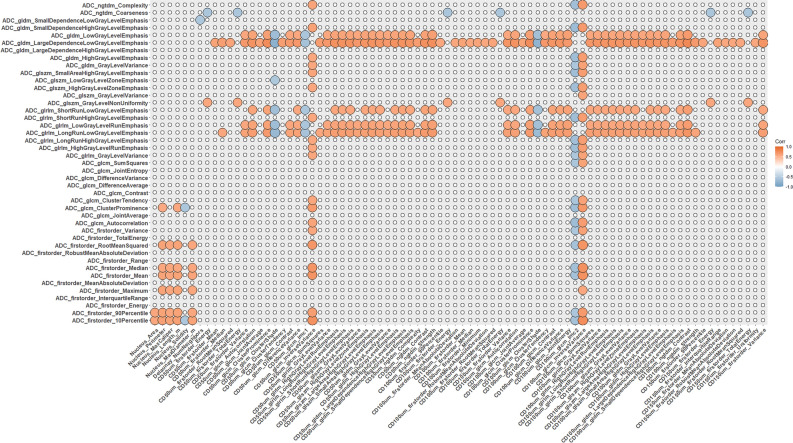

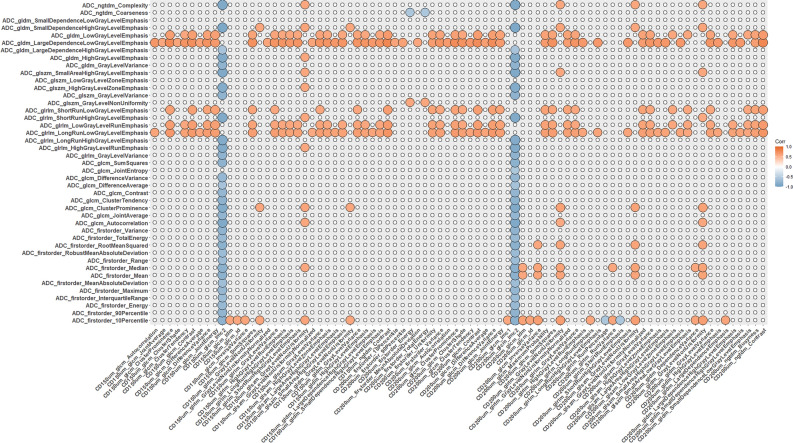

Radiopathomic analysis between ADC radiomic and pathomic features revealed 683 significant correlations after FDR correction, including 116 negative correlations (-0.8929 < ρ < − 0.5743, 9.52 × 102 < BF < 4.77 × 1014) and 567 positive correlations (0.5742 < ρ < 0.7866, 9.47 × 102 < BF < 3.18 × 108). The ADC radiomic features included 13 firstorder and 30 texture features, while pathomic features included 6 morphometric features associated with nuclei (Area, Perimeter, Maximum Caliper, Length, Solidity, and Max Diameter), Delaunay number of neighbors, and 157 cell-density map features (of which 31 from 50 μm resolution, 35 from 100 μm resolution, 41 from 150 μm resolution and 50 from 200 μm resolution).

The strongest ADC-pathomic relationships (23 out of 683 with ρ = 0.80–1.00) involved the textural feature Information Measure of Correlation 2 from cell density maps, of which 3 correspond to associations with ADC firstorder features and the remaining 20 were with textural ADC features. Concerning other strong associations (416/683 with ρ = 0.60–0.79), most of them involved textual features from cell density maps at different resolutions (404/416) with ADC firstorder features (67 associations) and textural features (349 associations), while the remaining 12 involved nuclear morphometric features (Perimeter, Max Diameter) and ADC firstorder features (10th and 90th percentile, Mean, Root Mean Squared, Mean and Maximum).

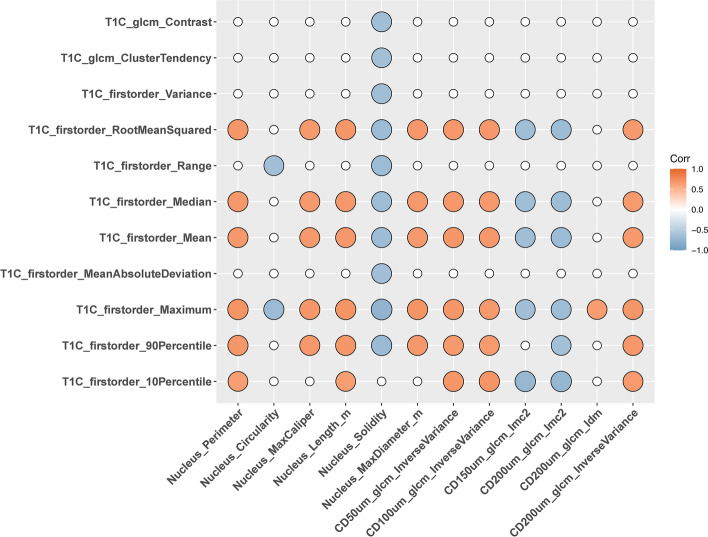

Radiopathomic analysis between T1C radiomic features and pathomic features revealed 73 significant correlations after FDR correction, of which 32 negative correlations (-0.764 < ρ < -0.6417, 9.47 × 104 < BF < 4.37 × 107) and 41 positive correlations (0.641 < ρ < 0.7082, 1.74 × 10e04 < BF < 7.53 × 105). The T1C radiomic features included 10 firstorder features and 11 texture features, while pathomic features included 6 morphometric features associated with nuclei (Perimeter, Circularity, Maximum Caliper, Length and Solidity) and 6 cell-density map features (of which 1 from 50 μm resolution, 1 from 100 μm resolution, 1 from 150 μm resolution and 3 from 200 μm resolution).

All significant T1C-pathomic associations were associated with strong correlation values (ρ = 0.60–0.79), with most of them (43/73) involving morphometric nuclear features and T1C firstorder (33/43) or textural features (10/43). The remaining 30 associations involved textural features from cell density maps and firstorder T1C features. Refer to Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 for the complete set of radiopathomic associations, with the radiopathomic features pairs sorted by |ρ|.

Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the resulting correlation heatmaps, displaying Spearman’s ρ between radiomic features (from ADC and T1C, respectively) and pathomic features.

Fig. 3.

Radiopathomic analysis between ADC radiomic features and pathomic features (part 1). Correlation matrix filtered from nonsignificant correlations (rows and columns with non-significant values were deleted, while non-significant values surviving were set to zero).

Fig. 4.

Radiopathomic analysis between ADC radiomic features and pathomic features (part 2). Correlation matrix filtered from nonsignificant correlations (rows and columns with non-significant values were deleted, while non-significant values surviving were set to zero).

Fig. 5.

Radiopathomic analysis between ADC radiomic features and pathomic features (part 2). Correlation matrix filtered from nonsignificant correlations (rows and columns with non-significant values were deleted, while non-significant values surviving were set to zero).

Discussion

The integration of radiomic and pathomic data offers significant potential for enhancing the diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic management of EC of uterine corpus. This study explored whether radiomic features from functional MRI images such as ADC and T1C, which provide macroscopic tumor assessments, correlate with pathomic features from histopathological images of H&E-stained tissue slides, which offer microscopic insights into tumor heterogeneity.

Although previous studies support the hypothesis that radiomic and pathomic signatures can independently predict clinically relevant outcomes in EC17,24,28, the novelty of this study lies in investigating the associations between these imaging modalities, a gap previously unaddressed in the literature.

Our preliminary results revealed significant cross-scale associations between radiomic features from preoperative ADC maps and T1C images and pathomic descriptors derived from histological images. Specifically, the correlation strengths for ADC radiopathomic correlations ranged from 0.57 and 0.89 in absolute value, whereas they ranged from 0.64 and 0.70 for T1C radiopathomic correlations. These findings were supported by very large BF values, which ranged from 9.47 × 104 to 4.77 × 1014 for the ADC task and from 1.80 × 104 to 5.69 × 105 for the T1C task.

Notably, the number of significant cross-scale associations involving ADC was approximately nine times higher than those involving T1C, with most significant and high cross-scale associations found between ADC textural features and features from cell density maps. This observation may be attributed to the closer imaging scale of cell density maps to radiology images, compared to pathomic features at the nuclear or cellular level. Furthermore, as also observed in our previous glioblastoma study44, the number of significant radiopathomic correlations between ADC texture features and cell density map features increased with decreasing resolution of the cell density maps—31 correlations at 50 μm resolution, 35 at 100 μm resolution, 41 at 150 μm resolution, and 50 at 200 μm resolution.

However, other interesting radiopathomic correlations involving morphometric features associated with nuclei (Area, Perimeter, Maximum Caliper, Length, Solidity, and Max Diameter) and ADC firstorder features were found. These relationships could be related to the influence of nuclear morphometry on tissue microstructure, which affects water diffusion patterns captured by ADC imaging. Nuclei with larger or more irregular shapes may indicate areas of higher cellularity or altered extracellular matrix, leading to restricted diffusion and lower ADC values. Additionally, these morphometric features can reflect variations in tumor aggressiveness and heterogeneity, which are also detectable through changes in ADC measurements. Thus, the observed correlations suggest a link between nuclear characteristics and the broader tissue architecture, impacting diffusion properties measured by ADC.

Of note, in the T1C pipeline, most of the radiopathomic correlations involved morphometric nuclear features (Perimeter, Circularity, Maximum Caliper, Length and Solidity) and T1C first-order features. These correlations might be due to the fact that T1C imaging highlights tissue contrast based on the uptake of contrast agents, which can reflect underlying variations in tissue composition and structure. Morphometric nuclear features such as area, perimeter, and solidity are indicative of the cellular and nuclear architecture within the tissue. Therefore, areas with larger or more irregularly shaped nuclei might correspond to regions with altered vascularity or extracellular matrix, which are captured by T1C imaging through variations in contrast enhancement.

Despite a smaller proportion of radiopathomic correlations involving textural features from cell density maps and first-order T1C features, it is worth noting that the number of correlated pairs also increases as the resolution of the cell density map decreases.

To our knowledge, this is the first study aiming at investigating radiopathomic associations in EC.

Previous research has demonstrated that both radiomic and pathomic image-based signatures can independently predict outcomes of interest in EC17,24,28.

However, no studies have explored the associations between MRI images of EC patients, which capture the tumor at a macroscopic scale, and features derived from histopathologic images, which depict the tumor at a microscopic scale.

While some previous studies investigated the correlation between MRI-based features and histopathological findings, they did not perform a quantitative histopathological analysis1,5,29. Dokter et al.45 presented a pictorial essay on radiology–pathology correlation at different FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stages to help reporting radiologists to have a better understanding of the local spread of endometrial carcinoma and its imaging appearance. However, their review was limited to a visual comparison and did not include the extraction of numerical descriptors from radiology or pathology images.

Other studies have investigated radio-genomic correlations in EC46,47.

Radiopathomic studies have been conducted in the context of other cancer types such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, and brain tumors44,48–51.However, most of these studies focused on developing prediction models that combine features extracted from both radiological and digital pathology images, without exploring the underlying correlations among them. It is worth noting that before making predictions it is important to understand if there are actually correlations between radiomic and pathomic characteristics52. In our previous study on glioblastoma patients44, we pursued a similar aim with respect to the current study. Interestingly, the findings of the current study are comparable to those of our previous study, particularly regarding the higher number of significant cross-scale associations involving ADC compared to those involving T1C. One possible explanation of these similarities is surely the inherent sensitivity of ADC imaging to cellular density and microstructural variations within the tumor environment. This makes ADC particularly effective in identifying significant correlations with histopathologic features, especially those derived from cell density maps, across different types of tumors. Additionally, similar to our previous study on glioblastoma, we observed an increase in the number of significant radiopathomic correlations between MRI texture features and cell density map features as the resolution of the cell density maps decreased. This observation may be attributed to the inherently closer imaging scale of cell density maps to radiology images, a proximity that becomes even more pronounced as the resolution decreases.

At lower resolutions, cell density maps provide a more aggregated and smoothed representation of tissue structure that highlights broader tissue patterns that align more closely with the macroscopic scale of MRI images. Such alignment could facilitate stronger and more consistent correlations between MRI texture features and cell density features, irrespective of the specific tumor type. This suggests a generalizable principle in radiopathomic studies, where cell density maps serve as a reliable intermediary between microscopic histopathological details and macroscopic radiological features.

It is worth noting that, while our comparison with the previous study on glioblastoma offers valuable insights, it is essential to interpret these findings with caution due to several key differences between the two studies. First, there are inherent differences in the radiopathomic workflow, particularly regarding the radiological analysis. Segmenting glioblastoma poses unique challenges, such as the presence of significant edema, necrosis, and other microstructural abnormalities that are less prominent in EC53,54. Moreover, glioblastoma and EC represent two distinct tumor types, both in terms of biology and microenvironment. Glioblastoma is a highly aggressive brain tumor with considerable heterogeneity and rapid progression, while endometrial cancer typically presents a different pathology, often with less pronounced necrosis and microstructural complexity3,55. These biological differences naturally influence both the radiologic and pathologic characteristics of the tumors, as well as their respective correlations with imaging features.

Despite these differences, we believe the comparison between the two studies is justified, particularly in light of the limited number of radiopathomic studies available in the literature. By comparing our findings across different tumor types, we aim to contribute to the growing body of knowledge in this emerging field, while acknowledging the limitations inherent in cross-tumor comparisons.

Despite the promising preliminary results obtained, the study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the small population size limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies with larger cohorts are essential to validate and expand upon our results. Another limitation is the inability to investigate the association between pathomic features and features derived from quantitative parameters associated with perfusion, such as Ktrans, Kep, Ve, and CBV, due to the non-availability of DCE/DSC images for the included patients. This constraint limits our understanding of the full spectrum of tumor physiology.

Another limitation relates to the imaging parameters of the publicly available dataset used, particularly in terms of DWI acquisition. The selection of b-values and slice thickness can influence ADC accuracy, as lower b-values may introduce perfusion-related effects, and larger slice thickness can lead to partial volume averaging, particularly in regions with smaller anatomical structures56–58. These limitations are inherent in working with publicly available dataset, as we did not have control over the acquisition protocols used. Despite this, our results demonstrate meaningful radiopathomic correlations, suggesting the utility of the dataset, though the impact of these factors should be carefully considered. Future studies should aim to utilize optimized acquisition parameters to enhance the accuracy of ADC calculations and their subsequent correlation with histopathologic features.

The study also faced challenges related to the precise colocalization of radiological images and histological tissue. Although this lack of precise colocalization could be seen as a limitation, it also reflects the real-world data scenario, where such colocalization is typically not available in clinical practice. To mitigate this issue, we attempted to align the data by segmenting as accurately as possible and excluding areas of necrosis and large vessels. This approach helps to approximate the real clinical environment and ensures that our findings are more applicable to everyday clinical settings.

Additionally, the lack of standardization in radiomic and pathomic procedures and features poses a challenge. Despite this, we employed pyradiomics, which is IBSI-compliant, and meticulously described all procedures to enhance reproducibility59. Adhering to standardized protocols in future studies will be crucial to improving consistency and comparability across different studies.

Despite these limitations, our preliminary study provides a valuable foundation for future investigations and highlights the potential of integrating radiomic and pathomic data to enhance the understanding of tumor biology. This relationship could validate radiomic approaches in clinical practice, positioning them as “virtual biopsies” that provide comprehensive tumor characterization without invasive procedures10.

In conclusion, the advances in knowledge from this study lie in the detailed exploration of the relationship between functional MRI features and histopathologic characteristics in uterine corpus EC. The identification of stronger and more frequent correlations between ADC texture features and cell density maps, and the resolution-dependent nature of these correlations, offers novel insights into how MRI can non-invasively reflect tumor heterogeneity and cellular architecture. These findings suggest that ADC could play a central role in non-invasive tumor characterization and may support the use of radiomics as a surrogate for tissue biopsy in clinical practice. T1C, while showing fewer associations, primarily correlated with nuclear morphometric features, reflecting tumor vascularity and extracellular matrix changes. Together, these results contribute to the growing field of radiopathomics by highlighting the potential of integrating radiomic and pathomic data to enhance the diagnostic and prognostic understanding of UCEC and provide a foundation for further research to expand these findings into broader clinical applications.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Data used in this publication were generated by the National Cancer Institute Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium -CPTAC- (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cptac-ucec/).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, V.B. and C.C.; Methodology, V.B. and N.G.; Data Curation: N.G., Visualization, M.A.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, V.B. and N.G.; Writing-Review and Editing, C.C., M.S., M.A., and M.S.; Supervision, M.S. and C.C.

Funding

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (“Ricerca Corrente” project).

Data availability

The original dataset analysed during this study are publicy available (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cptac-ucec/). The processed datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78987-y.

References

- 1.Zheng, T. et al. Combination analysis of a radiomics-based predictive model with clinical indicators for the preoperative assessment of histological grade in endometrial carcinoma. Front Oncol.11, 582495 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin, M., Osman, M., Abdel Reheim, A. & Hassan, R. The Role of Dynamic Post Contrast Enhanced and Diffusion Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Detection of Endometrial Carcinoma. Minia J. Med. Res.31, 322–331 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatius, S. et al. Tumor Heterogeneity in Endometrial Carcinoma: Practical Consequences. Pathobiology85, 35–40 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin, F.-F. et al. Intra-tumor heterogeneity for endometrial cancer and its clinical significance. Chinese Med. J.132, 1550–1562 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada, I. et al. Endometrial Carcinoma: Texture Analysis of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Maps and Its Correlation with Histopathologic Findings and Prognosis. Radiol. Imaging Cancer1, e190054 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urushibara, A. et al. The efficacy of deep learning models in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer using MRI: a comparison with radiologists. BMC Med Imaging22, 80 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meissnitzer, M. & Forstner, R. MRI of endometrium cancer – how we do it. Cancer Imaging16, 11 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maheshwari, E. et al. Update on MRI in Evaluation and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer. Radiographics42, 2112–2130 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sala, E., Rockall, A., Rangarajan, D. & Kubik-Huch, R. A. The role of dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the female pelvis. Eur. J. Radiol.76, 367–385 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambin, P. et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.14, 749–762 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures They Are Data. Radiology278, 563–577 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Greca Saint-Esteven, A. et al. Systematic Review on the Association of Radiomics with Tumor Biological Endpoints. Cancers13, 3015 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, X. et al. Radiomics predicts the prognosis of patients with locally advanced breast cancer by reflecting the heterogeneity of tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res24, 20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sala, E. et al. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity using next-generation imaging: radiomics, radiogenomics, and habitat imaging. Clin. Radiol.72, 3–10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo, W. et al. Advances in Radiomics Research for Endometrial Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. J. Cancer14, 3523–3531 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno, Y. et al. Endometrial Carcinoma: MR Imaging–based Texture Model for Preoperative Risk Stratification—A Preliminary Analysis. Radiology284, 748–757 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob, H. et al. An MRI-Based Radiomic Prognostic Index Predicts Poor Outcome and Specific Genetic Alterations in Endometrial Cancer. JCM10, 538 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He, J., Liu, Y., Li, J. & Liu, S. Accuracy of radiomics in the diagnosis and preoperative high-risk assessment of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol.14, 1334546 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, M.-L. et al. Application of magnetic resonance imaging radiomics in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiol med129, 439–456 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim, A. et al. Radiomics for precision medicine: Current challenges, future prospects, and the proposal of a new framework. Methods188, 20–29 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abels, E. et al. Computational pathology definitions, best practices, and recommendations for regulatory guidance: a white paper from the Digital Pathology Association. J. Pathol.249, 286–294 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta, R., Kurc, T., Sharma, A., Almeida, J. S. & Saltz, J. The Emergence of Pathomics. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep.7, 73–84 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui, M. & Zhang, D. Y. Artificial intelligence and computational pathology. Lab. Investig.101, 412–422 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, Y.-L. et al. Role of artificial intelligence in digital pathology for gynecological cancers. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J.24, 205–212 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De, S. et al. A fusion-based approach for uterine cervical cancer histology image classification. Computerized Med. Imaging Graphics37, 475–487 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo, P. et al. Nuclei-Based Features for Uterine Cervical Cancer Histology Image Analysis With Fusion-Based Classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform.20, 1595–1607 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Gonzalez, P. et al. Integrative radiogenomics for virtual biopsy and treatment monitoring in ovarian cancer. Insights Imaging11, 94 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manganaro, L. et al. Radiomics in cervical and endometrial cancer. Br. J. Radiol.94, 20201314 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo, S., Cho, J. Y., Kim, S. Y. & Kim, S. H. Histogram analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient map of diffusion-weighted MRI in endometrial cancer: a preliminary correlation study with histological grade. Acta Radiol.55, 1270–1277 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishimoto, K. et al. Endometrial cancer: correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) with tumor cellularity and tumor grade. Acta Radiol.57, 1021–1028 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrila, O., Nistor, I., Romedea, N. S., Negru, D. & Scripcariu, V. Can the ADC Value Be Used as an Imaging “Biopsy” in Endometrial Cancer?. Diagnostics14, 325 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, S. H. et al. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Perfusion Parameters as Imaging Biomarkers of Angiogenesis. PLoS ONE11, e0168632 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turkbey, B., Thomasson, D., Pang, Y., Bernardo, M. & Choyke, P. L. The role of dynamic contrast enhanced MR imaging in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Diagn. Interv. Radiol.10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.2537-08.1 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dou, Y. et al. Proteogenomic Characterization of Endometrial Carcinoma. Cell180, 729-748.e26 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dou, Y. et al. Proteogenomic insights suggest druggable pathways in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Cell41, 1586-1605.e15 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep.7, 16878 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malpica, N. et al. Applying watershed algorithms to the segmentation of clustered nuclei. Cytometry28, 289–297 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuadros Linares, O. et al. Efficient Segmentation of Cell Nuclei in Histopathological Images. in 2020 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS) 47–52 (IEEE, Rochester, MN, USA, 2020). 10.1109/CBMS49503.2020.00017.

- 39.Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.10.1109/TSMC.1973.4309314 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paul Chew, L. Constrained delaunay triangulations. Algorithmica4, 97–108 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swinscow, T. D. V. & Campbell, M. J. Statistics at Square One (BMJ Publ. Group, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kass, R. E. & Raftery, A. E. Bayes Factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.90, 773–795 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stefan, A. M., Gronau, Q. F., Schönbrodt, F. D. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. A tutorial on Bayes Factor Design Analysis using an informed prior. Behav. Res. Methods51, 1042–1058 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brancato, V. et al. The relationship between radiomics and pathomics in Glioblastoma patients: Preliminary results from a cross-scale association study. Front. Oncol.12, 1005805 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dokter, E. et al. Radiology–pathology correlation of endometrial carcinoma assessment on magnetic resonance imaging. Insights Imaging13, 80 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Celli, V. et al. MRI- and histologic-molecular-based radio-genomics nomogram for preoperative assessment of risk classes in endometrial cancer. Cancers14, 5881 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoivik, E. A. et al. A radiogenomics application for prognostic profiling of endometrial cancer. Commun. Biol.4, 1363 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, J. et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomic model for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer23, 431 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bobholz, S. A. et al. Radio-Pathomic Maps of Cell Density Identify Brain Tumor Invasion beyond Traditional MRI-Defined Margins. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.43, 682–688 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bobholz, S. A. et al. Radio-pathomic maps of glioblastoma identify phenotypes of non-enhancing tumor infiltration associated with bevacizumab treatment response. J. Neurooncol.167, 233–241 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hiremath, A. et al. An integrated radiology-pathology machine learning classifier for outcome prediction following radical prostatectomy: Preliminary findings. Heliyon10, e29602 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu, C., Shiradkar, R., Liu, Z., Biomedical Engineering Department, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland 44106, OH, USA, & Department of Radiology, Guangzhou First People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510080, China. Integrating pathomics with radiomics and genomics for cancer prognosis: A brief review. Chinese Journal of Cancer Research33, 563–573 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Bonada, M. et al. Deep Learning for MRI segmentation and molecular subtyping in glioblastoma: critical aspects from an emerging field. Biomedicines12, 1878 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.dupont, c, betrouni, n, reyns, n & vermandel, m. on image segmentation methods applied to glioblastoma: state of art and new trends. IRBM37, 131–143 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parker, N. R., Khong, P., Parkinson, J. F., Howell, V. M. & Wheeler, H. R. Molecular Heterogeneity in Glioblastoma: Potential Clinical Implications. Front. Oncol.10.3389/fonc.2015.00055 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He, Y. et al. Impact of different b-value combinations on radiomics features of apparent diffusion coefficient in cervical cancer. Acta Radiol.61, 568–576 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogura, A., Hayakawa, K., Miyati, T. & Maeda, F. Imaging parameter effects in apparent diffusion coefficient determination of magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. J. Radiol.77, 185–188 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asai, A., Ogura, A., Sotome, H. & Fuju, A. Effect of Slice Thickness for Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Measurement of Mass. Nippon Hoshasen Gijutsu Gakkai Zasshi74, 805–809 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zwanenburg, A. et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative Radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology295, 328–338 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original dataset analysed during this study are publicy available (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cptac-ucec/). The processed datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.