Abstract

The cornea, the anterior meniscus-shaped transparent and refractive structure of the eyeball, is the first mechanical barrier of the eye. Its functionality heavily relies on the health of its endothelium, its most posterior layer. The treatment of corneal endothelial cells (CECs) deficiency is allogeneic corneal graft using stored donor corneas. One of the main goals of eye banks is to maintain endothelial cell density (ECD) and endothelial barrier function, critical parameters influencing transplantation outcomes. Unlike in vivo, the stored cornea is not subjected to physiological mechanical stimuli, such as the hydrokinetic pressure of the aqueous humor and intraocular pressure (IOP). YAP (Yes-Associated Protein), a pivotal transcriptional coactivator, is recognized for its ability to sense diverse biomechanical cues and transduce them into specific biological signals, varying for each cell type and mechanical forces. The biomechanical cues that might regulate YAP in human corneal endothelium remain unidentified. Therefore, we investigated the expression and subcellular localization of YAP in the endothelium of corneas stored in organ culture (OC). Our findings demonstrated that CEC morphology, ECD and cell–cell interactions are distinctly and differentially associated with modifications in the expression, subcellular localization and phosphorylation of YAP. Notably, this phosphorylation occurs in the basal region of the primary cilium, which may play central cellular roles in sensing mechanical stimuli. The sustained recruitment of YAP in cellular junctions, nucleus, and cilium under long-term OC conditions strongly indicates its specific role in maintaining CEC homeostasis. Understanding these biophysical influences could aid in identifying molecules that promote homeostasis and enhance the functionality of CECs.

Keywords: Cornea, Endothelium, Organ culture, Storage, Yes-Associated Protein (YAP), Biomechanics

Subject terms: Cell signalling, Fluorescence imaging, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Corneal homeostasis is largely dependent on the maintenance of a healthy endothelium, the most posterior layer of the cornea, in contact with the aqueous humor. This approximately 25 µm-thick layer plays a critical role in maintaining corneal transparency, regulating corneal deswelling by acting as a semi-permeable barrier to the movement of fluids and nutrients, and providing transport functions1. Corneal endothelial cells (CECs) are a monolayer of highly polarized cells which maintains the barrier, in part, through the expression of the tight junction (TJ) component Zonula-Occludens 1 (ZO-1)2. These cells exhibit specific structures that are related to their constant exposure to physiological mechanical cues, as defined by: (1) a hexagonal apical surface, well-characterized by ZO-1, actin and myosin, forming a dynamic network dependent on the hydrodynamics of the aqueous humor and intraocular pressure (IOP); (2) basal lateral membrane expansions forming interdigitating foot processes in contact with Descemet’s membrane to maximize intercellular exchange surfaces2. Endothelial cell density gradually decreases throughout life, at an extremely slow rate of 0.3–0.6% per year3–5. In vivo, human CECs are arrested at the G1 phase of the cell cycle, preventing endothelial regeneration by cell division6. Excessive pathological loss of CECs, along with damage or dysfunction, hinders efficient fluid pumping from the stroma, resulting in stromal and epithelial edema. Ultimately, this leads to the loss of corneal transparency and a permanent decrease in visual acuity. The corneal endothelium has long been considered to consist of a population of homogeneous cells. Single cell transcriptomics revealed the cell heterogeneity of the cornea endothelium in various species, including human. In healthy human corneas, Català et al., identified two major clusters of CECs, one possessing a lower expression of tight junction protein, ZO-1, and focal adhesion regulator microtubule-actin cross-linking factor-1 (MACF1) compared to cluster the other one7. In contrast, Wang et al., discovered 4 subpopulations of CECs with distinctive signatures8. The first CEC cluster was enriched in functions related to oxygen level response/oxidation–reduction and response to extracellular matrix organization, whereas the second one was related to regulation of cell death and response to stress. The third CEC subtypes was associated with DNA replication and the cell cycle, while the fourth one was associated with senescence. Altogether, these studies strongly revealed the heterogeneous cell composition with distinct transcriptional signals and functional commitments across clusters in human corneal endothelium.

Corneal graft is the most common transplant procedure worldwide, representing the only validated treatment for numerous corneal diseases, including endothelial dysfunctions. After retrieval from the cadaver, the corneas, along with a scleral rim, are immediately immersed in a culture medium to ensure the temporary survival of CECs, and stored in eye banks. Two methods are used: cold storage at + 4 °C for up to 15 days, and organ culture (OC) at physiological temperature (31–37 °C), allowing corneas to be stored for up to 5 weeks9. However, regardless of the method used so far, the daily loss of CECs during storage is significantly higher compared to physiological conditions, thus reducing the quality of the tissue. For instance, during OC, the CEC loss approaches 1% per day, approximately 600 times higher than under physiological in vivo conditions10–12. Once the cornea is harvested and immersed in the storage medium, it is no longer subject to the various physiological mechanical stimuli that may be essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis. In the first days of storage, the ex vivo cornea undergoes changes characterized by the onset of edema accompanied by the formation of deep corneal folds, leading to an increased mortality of CECs13,14. Rearrangements of the endothelial mosaic occurring after 15–60 min of incubation in OC, as damaged cells were expelled from the coherent cell sheet by neighbouring cells15. A localized cellular loss triggers remodelling and healing processes by the enlargement of neighbouring CECs to compensate for this loss and maintain the continuity of the endothelial layer. This gradual transformation shifts the mosaic pattern from a hexagonal arrangement into a disordered arrangement with increased polymegethism and pleomorphism2,16,17. This rearrangement, mediated by force transmission through cell–cell adhesion and shape change of cells, which become locked in place by their neighbours, allows for the maintenance of endothelial function18. The molecular impact of mechanical forces on the structure, integrity and cellular rearrangement of the corneal endothelium, as well as its functions, remains unclear and is not thoroughly established.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) is a transcriptional coactivator of the major biomechanical pathway, well known as Hippo pathway, which plays a key role as an integrator of signals switching between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, regulating tissue homeostasis19,20. The primary regulatory mechanism of YAP involves its nucleocytoplasmic translocation, which depends on its phosphorylation status, in response to various mechanical stimuli in in vitro proliferative models. Activation of the Hippo pathway inactivates YAP by repressing its nuclear translocation and activation via phosphorylation on the Serine 127 residue (p-YAP Ser127), leading to a cytoplasmic retention and degradation21. However, the simplistic notion of YAP inactivation through Ser127 phosphorylation solely in the cytoplasm is increasingly contentious, as recent studies have identified this phosphorylated protein in the nucleus, where it remains co-transcriptionally active. Nuclear localization of p-YAP Ser127 can occur under several biological phenomena, such as osmotic stress22, nutriment deprivation23, oxidative stress and cell density that promote the nuclear translocation of p-YAP Ser12724. This raises significant questions regarding the importance of nuclear phosphorylation of YAP at Ser127 and its implications based on its subcellular localization, particularly in view of these biological phenomena that may emerge during corneal OC.

Moreover, the interaction between plasma membrane sensing domains and the Hippo pathway, particularly the translocation of YAP to cell–cell junction complexes, is well established in proliferating cells, highlighting the importance of intercellular junctions and tension in the regulation of YAP mediated by mechanical stimuli25. Although the role of YAP is well described in many 2D-cell culture systems, where cell size and proliferation are highly interdependent, a global in situ understanding of YAP remains limited due to the understudied interaction between YAP activation and cell tension in in vivo non-proliferative cells. The YAP subcellular localization in quiescent cells has been poorly studied and remained to be clearly characterized. Moreover, key factors are altered between 2D/3D cell culture systems and in situ conditions, including cell morphology, cell density, cellular tension, intercellular junctions and signalling responses to mechanical forces, challenging in vitro data on nuclearization/activation of YAP. The relative contributions of each biophysical signal and the mechanisms by which they synergistically regulate YAP localization in realistic tissue microenvironments that provide multiplexed input signals remains unclear and poorly studied. The precise function of endogenous YAP in human corneal endothelium physiology remains elusive, yet its elucidation is crucial for understanding the mechanisms governing endothelial homeostasis and, consequently, preventing their irreversible loss.

In this study, we explored both the expression and the phosphorylation-dependent subcellular localization of YAP in human corneas stored in OC to understand the impact of various mechanical cues, such as cell density and cell–cell junctions on the mechanotransduction signalling pathways.

Results

Endothelial YAP expression fluctuated during corneal storage and was related with organ culture-induced tissue and cellular changes

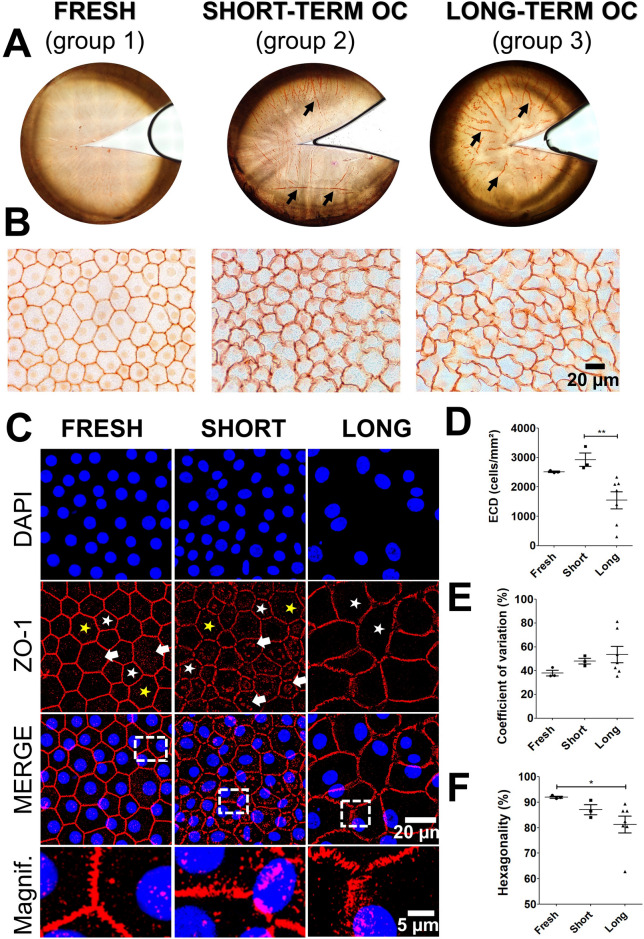

As expected, alizarin red highlighted the overall changes induced by OC in the endothelium and the progressive appearance of corneal folds during storage, ZO-1 immunostaining revealed structural alterations in intercellular junctions, and DAPI staining depicted changes in ECD and nuclear morphology (Fig. 1A–C). In group 1, the majority of intercellular junctions appeared straight and well-extended. The high ECD and the morphometric parameters were within physiological ranges, confirming that this group was representative of healthy corneas with mostly perfectly hexagonal cells (Fig. 1D–F). ZO-1 exhibited a thin, regular zig-zag pattern, and nuclei were evenly distributed and round. In contrast, group 2 displayed increased irregularity in cell shape, with a mix of hexagonal and pentagonal shapes, rounded and distended borders (Fig. 1B,C). ZO-1 patterns appeared enlarged and interrupted at Y-junctions between three cells. Interestingly, we detected the presence of ZO-1 cytoplasmic condensates forming a fragmented perinuclear and perijunctional belt in the CECs, whereas in group 1, these condensates were dispersed and punctate (Fig. 1C). This suggested junctional remodelling and an early adaptive response to OC. Although there was no significant difference in ECD, the distribution of cell nuclei was less uniform in group 2, with some nuclei displaying elongated shapes (Fig. 1D,E). In group 3, all the changes described above were amplified: the majority of cells were pentagonal and rectangular, exhibiting a tendency to become hypertrophic, without disruption in the endothelial mosaic; the ZO-1 zig-zag pattern continued to enlarge, and the nuclei were enlarged and tended to adopt an oval shape (Fig. 1B,C). The ZO-1 condensates pattern was less dense with an irregular distribution in the CECs, indicating a dynamic remodelling of ZO-1 throughout OC. The ECD and hexagonality were significantly lower, and CV of cell area tended to increase (Fig. 1D–F).

Fig. 1.

Morphological changes of the corneal endothelium during organ culture (OC). (A,B) Alizarin red staining of the human corneal endothelium. Corneal folds are indicated by black arrows. High magnification showing the morphology of corneal endothelial cells. (C) ZO-1 immunostaining of corneal endothelium (in red). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI in blue. The white and yellow stars indicate pentagonal and heptagonal cells, respectively. The white arrows indicate the presence of ZO-1 condensates in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells (D) Evaluation of Endothelial Corneal Density (ECD) relative to OC storage duration. (E,F) Quantification of morphometric parameters obtained through automated image analysis, including the coefficient of variation and hexagonality expressed as a percentage. Statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Moreover, the wide standard deviations of the mean values for morphometric parameters indicated substantial morphological heterogeneity among CECs during long-term storage. Collectively, these findings confirmed that our samples were representative of the early and continuous endothelial adaptation during OC. Indeed, the changes observed in the CECs have involved dynamic remodelling of cell–cell junctions, accompanied by an increase in entropy in the form of morphometric disorganization, gradually transitioning the mosaic from a hexagonal arrangement to a disrupted one. All these endothelial morphological changes observed during corneal storage, as illustrated in Fig. 1, suggest the potential involvement of biomechanical pathway components in this morphological alteration.

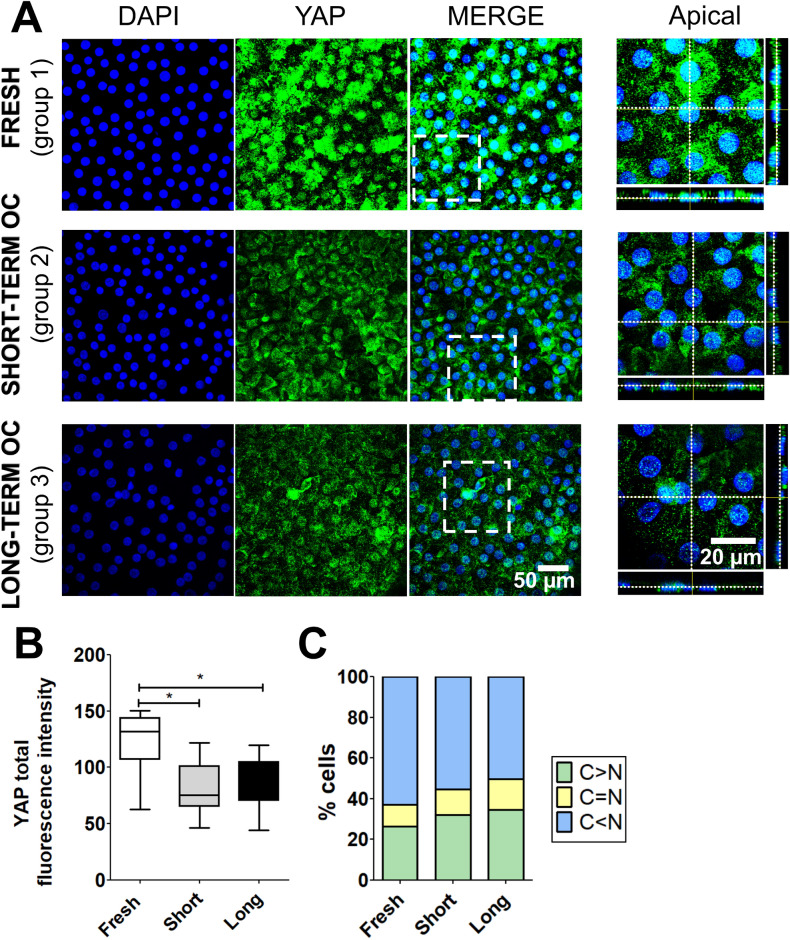

YAP is a protein sensitive to mechanical stimuli, including variations in cellular morphology and junctional tension. Hence, we investigated by immunostaining whether YAP expression and localization were affected during corneal OC. In the three groups, YAP was detected in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of CECs (Fig. 2A). Quantification of overall YAP demonstrated a significant 1.5-fold decrease in total fluorescence intensity in groups 2 and 3 compared to group 1 (Fig. 2B). Automated image processing revealed a predominant nuclear localization of YAP (C < N) in the three groups, with percentages of 63%, 55%, and 50% of cells, respectively (Fig. 2C). Cells with cytoplasmic localization of YAP (C > N) exhibited approximately one-fourth to one-third of the total YAP detection (fresh corneas: 26%, short-term OC corneas: 32%, and long-term OC corneas: 35%). Statistical analysis demonstrated significant changes in the subcellular distribution of YAP between the three groups (Khi2 test, p < 0.001). Taken together, OC induced a significant decrease in ECD and a significant alteration of YAP levels associated with subcellular localization changes.

Fig. 2.

Expression and subcellular localization of YAP in the corneal endothelium during organ culture (OC). (A) Immunostaining of YAP (in green) in fresh, short- and long-term OC corneas. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (in blue). (B) Quantification of total fluorescence intensity (unitless) of YAP in the three conditions. Statistical analysis was conducted using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, with *p < 0.05 (C) Quantification of the subcellular distribution of YAP based on the C/N ratio in the three conditions: cytoplasmic (C > N), nucleocytoplasmic (C = N), and nuclear (C < N) fraction. Khi2 test, p < 0.001.

During prolonged corneal storage, YAP subcellular localization was associated with the endothelial cell density and cell morphology

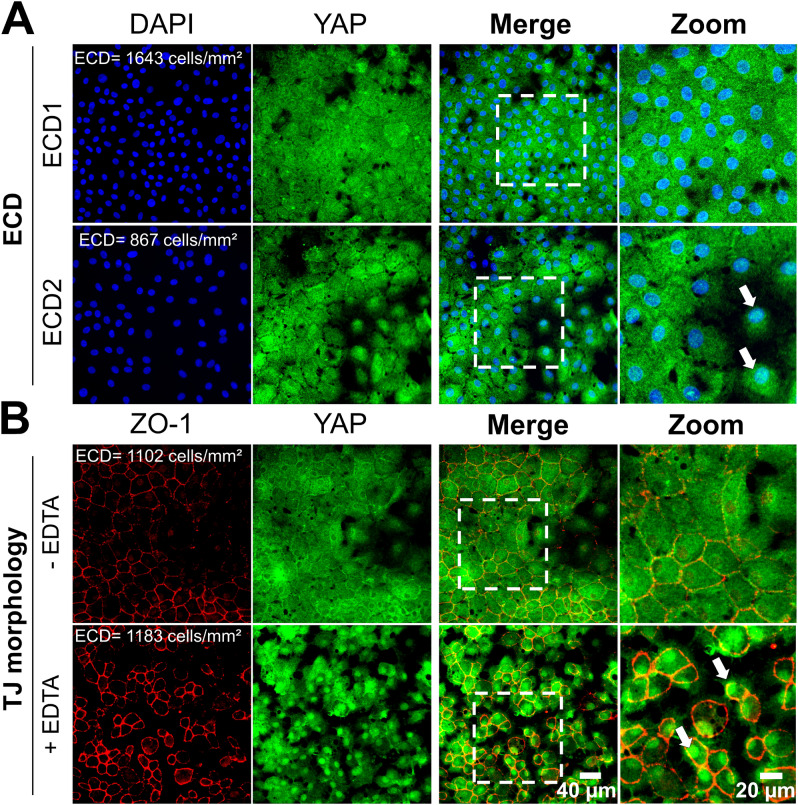

Monolayer cells maintain their cohesion under mechanical fluctuations as surface tension, cell density and cell size, by molecularly controlling cell–cell forces and collective cell dynamics26. Each cell adjusts its rheological properties individually by finely adjusting its mechanical characteristics in response to neighbouring cells and asymmetry. These mechano-adaptive responses imply that neighbouring cells join forces to transmit significant normal stress across the cell–cell junction, resulting in junctional rearrangements that occur differentially in various cell areas, thus reflecting heterogeneity in cellular behaviour27,28. For this purpose, we analysed in details the group 3, which exhibited heterogeneous endothelial cell morphology in long-term stored corneas (see Supplementary Fig. S1). We compared the three corneas with high ECD (2178 ± 137 cells/mm2, a value comparable to that of groups 1 and 2: greater than 2000 cells/mm2) with the four corneas with low ECD (1072 ± 703 cells/mm2). Endothelial cells from corneas with high ECD had 2 times less nuclear localization of YAP compared to corneas with low ECD, with C < N observed in 38% versus 77% of cells, respectively (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A,B). Moreover, we compared YAP localization in the three corneas with low CV (39 ± 4%, a physiological value comparable to group 1: 38 ± 4%), with the four corneas with high CV exhibiting polymegethism (64 ± 17%). The corneas with a homogeneous endothelial morphology exhibited nuclear localization of YAP in 55% of cells, versus 42% in the corneas displaying endothelial size heterogeneity (1.3-fold less, p < 0.001) (Figs. 3A,C). Interestingly, we also noted a 1.8-fold increase in the nucleocytoplasmic localization of YAP in corneas with high CV compared to those with low CV, suggesting dynamic changes in YAP shuttling associated with polymegethism. Statistical analysis demonstrated significant changes in the subcellular distribution of YAP with ECD and CV (Khi2 test, p < 0.001). Taken together, these findings suggested that ECD and cell–cell contact served as pivotal regulators in modulating the nuclear localization of YAP. In addition, they indicated that the ongoing evolution of corneal endothelium characteristics during long-term OC, governed by surface tension acting on cell boundaries, greatly modulated the nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution of YAP in CECs. The dynamic balance of a mixture of CEC morphology in long-term OC suggested that cell density, shape and size changes of cells could modify the YAP signalling-dependent fluid phase properties of the collective cell dynamics.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of YAP as a function of endothelial cell density and cell–cell contact in long-term organ cultured corneas. (A) Immunostaining of YAP (in green) and ZO-1 (in red) in corneal endothelial cells. Nuclei were counterstained by DAPI (in blue). Two representative endothelial morphologies were illustrated based on cell density. (B,C) Quantification of the subcellular localization of YAP (cytoplasmic: C > N, nuclear-cytoplasmic: C = N and nuclear: C < N) as a function of endothelial cell density (ECD in cells/mm2); Khi2 test, p < 0.001.

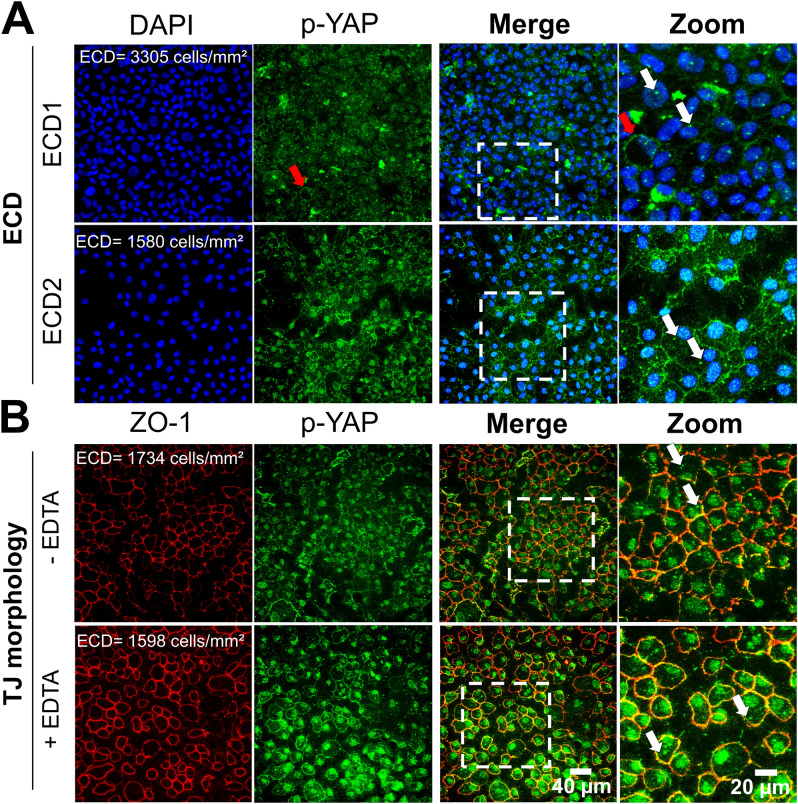

We first supported that cell density and morphological changes influence the YAP signalling pathway by conducting in vitro experiments on primary cells cultured from human corneas. Specifically, YAP predominantly localized in the cytoplasm (C > N in 65% of cells) at a cell density of 1643 cells/mm2 (ECD1). A two-fold reduction in cell number (ECD2 = 867 cells/mm2) resulted in a 1.7-fold decrease in cytoplasmic YAP localization (C > N in 38% of cells) (Fig. 4A). The nuclear localization of YAP increased by sevenfold between ECD1 and ECD2 (C < N: 1% vs. 7%, respectively), indicating that cell density influences the dynamic nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of YAP in CECs from the same donor cultured under similar culture conditions.

Fig. 4.

Subcellular localization of YAP in relation to cell density and morphological alterations in human corneal endothelial cells cultured in vitro. Immunostaining of YAP (in green) and ZO-1 associated-Tight Junctions (TJ, in red) in the corneal endothelial cells (A) at different endothelial cell density and (B) with/without Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-induced disrupted tight junctions. Nuclei were counterstained by DAPI (in blue). The cells used were primary human corneal endothelial cells cultured from ex vivo corneas (n = 2 donors). The white arrows indicated nuclear localization of YAP.

Furthermore, disrupting cell junctions with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) led to an evident increase in nuclear YAP localization in rounded CECs (C < N in 94% of cells) compared to conditions without EDTA (C < N in 1% of cells) at similar cell densities (Fig. 4B), confirming that cell morphology also affects the subcellular localization of YAP.

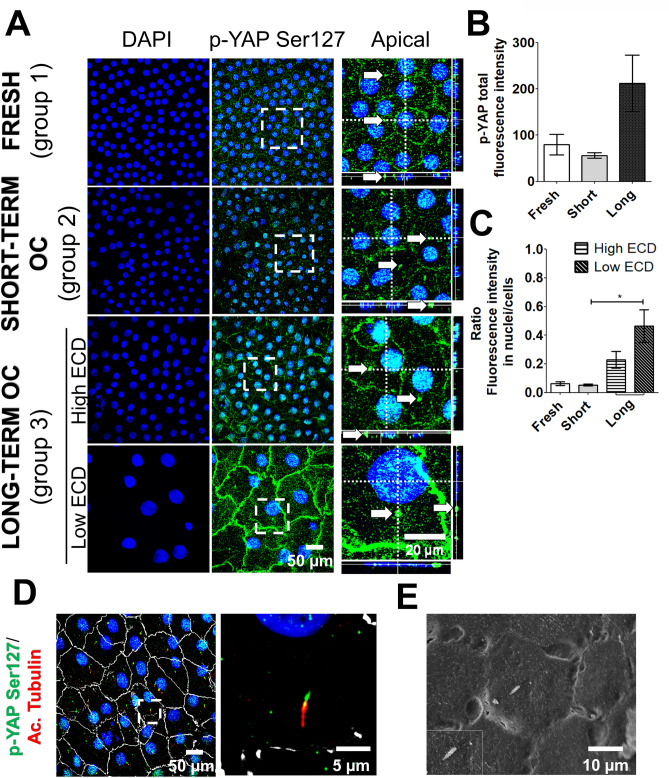

Organ culture profoundly impacted subcellular localization of phosphorylated YAP

The prevailing paradigm describes that the co-transcriptional activity of YAP is widely regulated by phosphorylation at Ser127 (p-YAP Ser127), resulting in the sequestration and subsequent inactivation of YAP within the cytoplasm in cellular proliferative models21. However, more recent studies reveal a new aspect of YAP regulation by phosphorylation, now detecting p-YAP Ser127 in cell nuclei22–24.Therefore, we investigated the presence of p-YAP Ser127 to characterize the impact of OC—biomechanically distinct from the in vivo conditions—on the regulation of YAP localization. In group 1 and 2, p-YAP Ser127 was expressed in the nucleus of all CECs and also in the cytoplasm and the plasma membrane, exhibiting a subtle and granular pattern (Fig. 5A). Additionally, we identified a positive speckled antennae-like staining pattern for p-YAP Ser127 in the cytoplasm of the great majority of CECs in both groups (Fig. 5A, white arrows). Automated image processing revealed no significant difference in fluorescence intensity between group 1 and 2, whether considering total fluorescence or fluorescence within nuclei (Fig. 5B,C). In group 3, p-YAP Ser127 was found in the same subcellular compartments as in the two other groups (Fig. 5A). However, within group 3, corneas exhibiting low ECD displayed two additional characteristics: a significant increase in nuclear fluorescence intensity and markedly heightened expression in the plasma membrane compared to both group 1 and 2, as well as to group 3 with high ECD (Fig. 5B,C). Co-staining of p-YAP Ser127 and acetylated tubulin revealed that the positive speckled needle-like staining pattern for p-YAP Ser127 detected in all 3 groups corresponded to the basal zone of the primary cilium. Scanning electron microscopy characterized the morphology of primary cilium, similar to the structure observed with the co-labelling of p-YAP Ser127 and acetylated tubulin (Fig. 5D,E). Overall, these findings indicated that both the duration of OC and the decrease of ECD had a significant effect on the level of phosphorylated YAP at Ser 127 and regulated its subcellular localization within the plasma membrane, nuclei, and cytoplasm.

Fig. 5.

Subcellular localization of phosphorylated YAP at Serine 127 as a function of endothelial cell density during corneal organ culture. (A) Immunostaining of p-YAP Ser127 (in green) in corneal endothelial cells, compared across different storage durations (fresh, short-term, and long-term). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (in blue). (B,C) Quantification of p-YAP Ser127 fluorescence total and in nuclei across fresh, short-term, and long-term storage. Differences were studied using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with * indicating significance when p < 0.05. (D) Immunostaining of p-YAP Ser127 (in green), acetylated α tubulin (in red) and ZO-1 (in white) in long-term organ-cultured cornea. (E) Scanning electron microscopy of primary cilium in corneal endothelial cells of a long-term organ-cultured cornea.

Colocalization of phosphorylated YAP and ZO-1 associated-tight junctions increased during organ culture

It has been demonstrated that the recruitment of the phosphorylated YAP at the junctional complex is dynamically regulated by cell density and cell–cell cohesion forces29. Double-labelling of p-YAP Ser127 and ZO-1 allowed us verifying whether the localization of the phosphorylated protein at the plasma membrane corresponds to the cell–cell junctional complex and assessing the influence of ECD and cell–cell contact on this spatial distribution. In group 1, a subtle and discontinuous pattern of p-YAP Ser127 staining was detected, concomitant with junctional ZO-1 staining (Fig. 6A). Automated image processing showed that 35 ± 21% of the ZO-1 fraction contained p-YAP Ser127 (Fig. 6B), indicating a scattered and heterogenous association of phosphorylated YAP with tight junctions. In group 2, the junctional localization of p-YAP Ser127 displayed punctuate pattern in most junctions, while a few others showed a linear staining (Fig. 6A). The average overlap of 23 ± 5% was not significantly different from fresh corneas (Fig. 6B). In group 3, the double staining showed a linear and continuous p-YAP Ser127 staining along cell junctions (Fig. 6A), contrasting with the other groups, with a significantly higher overlap with ZO-1: 66 ± 27% (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, in group 3, the junctional p-YAP Ser127 was significantly higher in corneas with low ECD: 73 ± 26% of overlap with ZO-1 versus 59 ± 28% in corneas with high ECD (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these findings suggest that OC duration and ECD significantly influence the recruitment of phosphorylated YAP at Ser127 in both cell–cell junctional complex and nuclei of CECs.

Fig. 6.

Junctional localization of phosphorylated YAP at Serine 127 as a function of endothelial cell density during corneal organ culture. (A) Immunostaining p-YAP Ser127 (in green) and ZO-1 associated-tight junctions (in red) in fresh, short-term and long-term stored corneas. (B) Quantification (in %) of the fraction of ZO-1 overlapping with the fraction of p-YAP Ser127 (in yellow) across all three conditions. Statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

We supported these findings by conducting in vitro experiments on primary cells cultured from human corneas, illustrating the effects of cell density and morphology on p-YAP Ser127 localization in primary cells cultured from human corneas. At a density of ECD1 = 3305 cells/mm2, p-YAP Ser127 predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, displaying a distinctive punctate antennae-like staining pattern. A very few numbers of cells exhibited membrane-bound p-YAP Ser127 staining (2% of cells). No cells showed colocalization of p-YAP Ser127 in the nuclei at ECD1 (Fig. 7A). Upon reducing the cell density by half (ECD2 = 1580 cells/mm2), p-YAP displayed a sparse and punctate distribution in the cytoplasm and localized at the cell membrane (29% of cells). The presence of p-YAP Ser127 at cell junctions was confirmed by co-staining with ZO-1. Conversely to the absence of nuclear p-YAP Ser 127 at ECD1, all cells showed nuclear p-YAP Ser127 at ECD2 (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Subcellular localization of phosphorylated YAP (p-YAP) at Serine 127 in relation to cell density and morphological alterations in human corneal endothelial cells cultured in vitro. Immunostaining of p-YAP (in green) and ZO-1 associated-Tight Junctions (TJ, in red) in the corneal endothelial cells (A) at different endothelial cell density and (B) with/without Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-induced disrupted tight junctions. Nuclei were counterstained by DAPI (in blue). The cells used were primary human corneal endothelial cells cultured from ex vivo corneas (n = 2 donors). The white arrows indicated a positive speckled antennae-like staining pattern for p-YAP Ser127 close to the nucleus in cell.

In low cell density cultures, disruption of cell junctions with EDTA induced cell rounding and led to a marked continuous membrane pattern of p-YAP Ser127 in CECs (72% of cells) (Fig. 7B). In contrast, only 24% of cells exhibited a junctional colocalization of p-YAP with ZO-1 under non-EDTA conditions at a comparable low cell density (Fig. 7B). Additionally, all cell nuclei exhibited colocalization of p-YAP Ser127 under both conditions; however, a punctate staining pattern was observed without EDTA, while a consistent and uniform staining pattern occurred with EDTA (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

Improving the storage of corneas is a major challenge to prevent tissue loss during eye banking and to provide higher quality tissue to patients. However, corneas undergo degradation, at various levels, that limit their shelf life during OC10: (1) at the tissue level, stromal edema causes the formation of posterior corneal folds30; (2) at the cellular level, these folds induce CECs apoptosis14, resulting in a rapid decrease in ECD and morphological shift with increased polymegethism and pleomorphism31; (3) at the molecular level, ZO-1 junctional remodelling leads to a dramatically amplified zigzag pattern2. In this study, we observed a new occurrence where ZO-1 condensates were dispersed throughout the cytoplasm of CECs, eventually coalescing to form a fragmented perinuclear and perijunctional belt, particularly observed in the early stages of OC. We hypothesized that cytoplasmic ZO-1 condensates may contribute to maintain cell–cell adhesion by enhancing TJs, a cellular mechanism previously described during the early development of the ectoderm32. All these morphological endothelial changes reflect an adaptive mechanism, potentially related to the reparative capacity to maintain their functionality in their role as a uniform endothelial barrier during OC, as described previously33. Therefore, studying the subcellular localization of YAP, a crucial mechanosensitive transcriptional co-activator in cellular adaptation mechanisms, represents a challenging approach for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms maintaining cellular homeostasis in CECs. We found only one published study on the role of YAP in cultured immortalized human CECs: Hsueh et al. elucidated YAP’s involvement in CEC proliferation via PI3K and ROCK pathways induced by Lysophosphatidic acid34.

For the first time to our knowledge, our study demonstrates the expression, localization, and phosphorylation of YAP according to storage conditions within fresh and OC corneas. We demonstrated that cell density differentially regulates the subcellular distribution of YAP in CECs during OC, on whole corneas that constitute a more complex model than immortalized 2D cell cultures. When the ECD is below 2000 cells/mm2 (consensual threshold for corneal transplantation), we observed a two fold increase in the nuclear translocation of YAP in CECs compared to corneas with higher ECD. This nuclear translocation at low ECD has been described in proliferative cell types, such as mouse embryonic fibroblasts, human mammary epithelial or also cancer cells to regulate cell proliferation in response to cell–cell contact21,35,36. However, since CECs do not proliferate in adults either in vivo or ex vivo, the nuclear localization of YAP in CECs likely reflects the activation of alternative cellular mechanisms such as tissue repair, apoptosis, or migration, all of which are also regulated by the YAP signalling. Further studies will be required to better understand the nuclear role of YAP by developing models of YAP overexpression or inactivation in ex vivo corneas. Another well-established mechanical parameters are cell morphology and cell–cell tension mediated by stress fibers, which play a pivotal role in the nuclear translocation of YAP in fibroblastic cell cultures37. In this study, we identified a distinct nucleocytoplasmic localization of YAP within a cell morphology exhibiting polymegethism compared to a homogeneous morphology. This suggest that YAP is an essential mediator in detecting and adaptively responding to the constant mechanical fluctuations experienced by this interconnected collective network. However, the association between morphometric factors of CECs and the nuclear regulation of YAP remains inconclusive, as the overall initial morphological quality of the majority of long-term stored corneas exhibited hexagonality values (percentage of cells with 6 neighbours) exceeding 60%, falling within physiological thresholds observed in vivo16. Interestingly, disrupting intercellular TJs using EDTA in primary in vitro CECs mimics the subcellular localization of YAP and p-YAP observed in ex vivo CECs with low ECD. This data supports the hypothesis that a dynamic interplay between TJ integrity, YAP/p-YAP pathway regulation, and cell morphology, although the mechanism of these interactions remains unclear in the non-proliferative corneal endothelium. Further investigation could involve recruiting rare corneas that exhibit comparable ECD but significantly different morphologies, or employing agents to disrupt TJs or actomyosin contractility. These strategies will help understanding the role of CEC morphology in regulating YAP expression and phosphorylation.

For several decades, a dogma on the regulation and activation of YAP has been the LATS1/2-mediated phosphorylation of YAP at Ser127, which promotes cytoplasmic sequestration, thereby suppressing its nuclear localization and co-transcriptional activity in various healthy and diseased cells lines38. In this study, long-term stored corneas with low ECD revealed a significantly increased of p-YAP Ser 127 within the CEC nuclei. A minor proportion of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated YAP was observed in the cytoplasm, suggesting a non-exclusive distribution of YAP, regardless of corneal storage conditions. Recently, various in vitro models have provided unprecedented insights into the dynamic nuclear‐cytoplasmic shuttling of YAP by showing damped and even sustained oscillations in the YAP nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, following those of mechanical stimuli39,40. The sequestration of YAP, whether in the cytoplasm or bound to junctional proteins, and its subsequent translocation to the nucleus dictate distinct roles that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Indeed, YAP nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling is not merely binary, as conventional models suggest, but rather it captures a dynamic continuum of movement between the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments, involving sequential translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. Moreover, Hong et al. demonstrated that osmotic stress induces the nuclear localization of YAP and increases its co-transcriptional activity, even when YAP is phosphorylated at the Ser127 residue in immortalized human embryonic kidney, revealing a new stress-induced mechanism of YAP activation for enhanced cellular stress adaptation22. Additionally, serum deprivation have been demonstrated to be associated with nuclear p-YAP Ser127 in human embryonic kidney cells.23 More recently, Wehling et al. showed that oxidative stress lead to both nuclear enrichment of YAP and p-YAP Ser127 in a hepatocyte-derived cell line24. Thus, the nuclear translocation of p-YAP Ser127 triggered by oxidative and osmotic stresses suggests that elevated levels of this phosphorylated protein in CECs during long-term OC could serve as markers of stress within the corneal endothelium. As the alternative model involving nuclear p-YAP Ser127 begins to emerge in various in vitro cellular stress models, it raises significant inquiries regarding the mechanism of YAP phosphorylation at Ser127 within the nucleus and its functional implications. This challenges the oversimplified model of YAP inactivation through LATS1/2-mediated phosphorylation at Ser127 in the cytoplasm, especially since recent studies have shown that LATS1 can be detected in the cell nucleus and that nuclear LATS1/2 can regulate the nuclear phosphorylation and localization of YAP24,41. Future investigations examining the expression and localization of LATS1/2 in CECs during OC may provide valuable insights.

Another significant finding from our study is that the TJs is a mechanosensitive compartment for phosphorylated YAP recruitment in CECs during OC, particularly at low ECD, as illustrated by a significant increase in the colocalization of p-YAP Ser127 and ZO-1. Recently, Kim et al. demonstrated that YAP is required for ZO-1 mediated TJs integrity by interacting with Angiomotin (AMOT) family proteins at TJs in cancer cells42, suggesting a non-co-transcriptional activity within junctional complex. All the more so as knockdown of ZO-1 resulted in reduced YAP at cell junctions, strongly suggesting a pivotal role of YAP in sensing mechanical stimuli at TJs42. Regarding the mechanism of YAP junctional recruitment, Paramasivam et al. showed that AMOT are novel activators of the LATS2 kinase-induced phosphorylation of YAP at Ser127 in renal, epithelial and cancer cells43, while another study suggested that AMOT-mediated localization of YAP to the cytoplasm and cell junctions is independent of YAP phosphorylation by LATS1/2 in the same types of cultured cells44. Another theory is that YAP could be recruited to TJs as a client protein in condensates formed by TJ-associated proteins, such as ZO proteins, as it has newly been demonstrated that YAP may function as a potential phase separation protein (PSP) in cancer and hyperosmotic stressed cells45,46. These findings would suggest that YAP liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) or condensate formation might occur and be induced by mechanical forces or post-translational modifications like phosphorylation, akin to ZO proteins. While the exact signalling pathways governing YAP junctional recruitment remain elusive, the notable junctional reorganization observed during long-term OC implies a distinct role for YAP phosphorylation at the Ser127 residue in preserving CEC homeostasis to maintain the endothelial mosaic, with functional barriers and intact cell–cell junctions.

Moreover, a notable outcome is the discovery of p-YAP Ser127 within the basal region of the primary cilium in ex vivo human CECs. It is interesting to note that acetylated tubulin consistently colocalized with p-YAP Ser127, indicating the presence of an elongated cilium. However, some speckled antennae-like patterns positive for p-YAP Ser127 lacked co-staining with acetylated tubulin. This observation suggests that while the basal structure of the cilium is present, the fully elongated ciliary structure may be absent. Morphologically defined structures within the plasma membrane, such as cellular junctions, along with the primary cilium, as demonstrated in our study, play central cellular roles in sensing mechanical stimuli through YAP. The primary cilium is expressed by CECs during embryonic development and wound healing, whereas it disappears in in vivo adult mice corneal endothelium47. The cilium has been recently identified as a central regulator of primary ZO-1-dependent cell junction integrity in vascular endothelium cells48, whereas p-YAP Ser127 was associated with serum starvation-mediated ciliogenesis in polycystic kidney disease endothelial cells49. Recently, Tanioka et al. demonstrated the disappearance and reappearance of the primary cilium in rabbit CECs under temperature fluctuations50, highlighting the adaptive dynamism of the cilium as a sensor. In accordance with the specific effects of long-term OC on the colocalization of junctional ZO-1 with p-YAP Ser127, we therefore hypothesized that long-term OC stimulates ciliogenesis as an adaptative response of the endothelium to maintain cell–cell interaction, and its morphology and functions.

Finally, the relative contributions of each biomechanical signal, such as cell density and morphology, and the mechanisms by which they synergistically regulate YAP subcellular localization within complex tissue microenvironments that offer multiplexed input signals, are still not fully understood. Ege et al. demonstrated a striking positive correlation between increased nuclear localization of YAP and expanding cytoplasmic perimeter in cultured fibroblastic cells, along with a negative correlation between nuclear YAP and cytoplasmic circularity41. This suggests that cell stretching is linked to elevated nuclear YAP levels. Furthermore, since spatiotemporal in vitro cellular models of YAP signalling activation, coupled with cellular force-generation machinery, showed a constant ratio between nuclear and cytoplasmic YAP under a fixed biomechanical stimulus51–53. As predicted by different computational models, we hypothesized that this ratio would vary according to different factors evolving during the various phases of OC kinetics. Perez-Gonzalez et al. employed a theoretical model of 3D cell shape to demonstrate that higher levels of nuclear YAP are connected to cell tension, thereby linking mechanical cell tension with cell size homeostasis in fibroblasts54. In this study, the absence of IOP and aqueous humor hydrodynamics—critical for maintaining corneal endothelial homeostasis—may constitute an important driver of the morphological alterations observed in CEC during OC, and potentially of their functionality12,55. Thus, among the factors influencing the adaptive response of CECs are cell–cell junctions and surface tension, along with other key factors such as cell–matrix interactions, matrix stiffness, shear stress, IOP, and cell volume, all contributing to the cellular adaptation aimed at maintaining cell homeostasis. During the storage of corneas in OC, their cells undergo a variety of biological processes, including cell survival56,57, apoptosis13,14, and loss of cell adherence to the Descemet membrane during the morphological rearrangement of the endothelial mosaic2,58. Studying all these biological processes in relation to YAP expression would represent an entire study in itself.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the biomechanical regulatory pathways are still unknown for the corneal endothelium. These new insights on YAP represents an essential approach for determining the effects of these biophysical cues, which could allow the identification biomechanics-associated molecules able to promote homeostasis and stimulate functions of CECs. To achieve this goal, it would be essential to identify the nuclear and cytoplasmic roles of YAP and to identify the YAP signalling pathway involved in normal corneal homeostasis and during OC. This will, open the way for a better corneal storage in eye banks and new pharmacological treatments for endothelial insufficiencies.

Methods

Human corneas, primary culture of endothelial cells and ethics statements

The handling of donor tissues adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 and its 1983 revision in protecting donor confidentiality. Three groups of corneas were obtained by in situ corneoscleral excision. Their characteristics were detailed in Table 1. Fresh corneas (group 1) were procured from 3 donors at the anatomy laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine of Saint-Etienne (body donation to Science). Each donor voluntarily donated their body and provided informed written consent to the Laboratory of Anatomy. Fresh corneas, by definition, were processed directly after excision without storage. These corneas were selected from donors with the shortest possible time between death and procurement to closely approximate physiological conditions. The remaining corneas were stored using the OC technique applied by the eye banks of Europe and Australia. Corneas were immersed in sealed flasks containing 100 mL of OC medium with 2% foetal calf serum (CorneaMax, Eurobio-Scientific, Les Ulis, France) and placed in a dry incubator at 31 °C. These corneas were deemed not suitable for transplantation because of medical and serological contraindications. The short-term storage group (group 2) comprised 3 corneas procured at the University Hospital of Saint-Etienne and stored for 19, 18 and 66 h, respectively, before processing. The long-term storage group (group 3) consisted of 7 corneas discarded by the eye banks of Saint-Etienne or Besancon. The time between death and procurement was equivalent between these 2 groups. There was no significant difference in the mean age of the 3 groups of donors (p = 0.17). All corneas were processed identically and were subjected to thickness measurement and immunostaining on flat-mounted whole corneas.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of fresh, short-term and long-term stored corneas used for immunostaining of YAP. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (min–max).

| Fresh corneas (Group 1) | Short-term storage (Group 2) | Long-term storage (Group 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of corneas | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Age of donors (years) | 82 ± 10 (71–91) | 80 ± 14 (70–96) | 71 ± 7 (65–80) |

| % of women | 25 | 67 | 20 |

| Time between death and procurement (hours) | 19 ± 12 (9–33) | 11 ± 5 (7–16) | 11 ± 7 (2–16) |

| Storage time in organ culture medium (days) | None | Max of 3 days | 30 ± 9 (18–40) |

In the in vitro experiments, primary human endothelial cells were cultured from ex vivo corneas obtained from two donors, aged 29 and 81 years. The culture methodology, previously detailed was applied59. Cells were seeded at a density of 500 cells/mm2 in 384-well plate (ref: 353961, Falcon, USA). To assess the impact of cell density, immunostaining was performed on non-confluent (day 7 post-seeding) and confluent cells (week 3 post-seeding). To investigate morphological changes following tight junction disruption and YAP subcellular localization, endothelial cells were incubated with 0.2 mg/ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS for 2.5 min at room temperature prior to fixation with 0.5% paraformaldehyde or 100% methanol depending on the primary antibody. Following fixation, cells were processed for immunostaining similarly to ex vivo corneas, as described above.

Corneal endothelium staining with alizarin red

Corneas were rinsed in balanced salt solution (BSS, Alcon, Texas, USA) beforehand and then incubated in 0.5% of alizarin red dye (A5533, Sigma, diluted in 0.9% of sodium chloride, pH 5.1), for 1 min at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, they were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 min at room temperature to remove excess staining and preserve the CEC, and then post-fixed in 100% ethanol. The corneas were flat-mounted between a slide and coverslip and observed under a bright-field optical microscope equipped with a colour camera (DP 26, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Scanning electron microscopy

Corneas were fixed in 0.1 N cacodylate-buffered 2% glutaraldehyde pH 7.4 at 4 °C for 48 h. Then, the samples were washed with 0.2 N cacodylate and distilled water, post-fixed in 0.1 M cacodylate-buffered 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. The specimens were then dehydrated through ascending concentrations of ethanol up to pure ethanol and finally with HMDS (hexamethydisilazane). Corneas were mounted on metal stubs with a double-sided adhesive tape and then coated with gold–palladium in a mini sputter coater (Polaron SC7620; Quarum technologies). The corneal endothelium was observed using a Hitachi S-3000N SEM (Tokyo, Japan) at an electron accelerating voltage of 5 kVolt.

Immunostaining on flat-mounted whole corneas

The protocol was previously developed and validated for the whole flat-mounted corneas60,61. Human corneas were fixed in pure methanol or in 0.5% PFA for 45 min at RT. Permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 (EuroMedex, 2000-B, Souffelweyersheim, France) was required for PFA-fixed corneas for 10 min at RT. Non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubating PFA and methanol-fixed corneas in blocking buffer (Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline, DPBS supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin) for 30 min at 37 °C. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer at 1:200 and 1:500 respectively (Table 2). The corneas were then cut into wedge-shaped segments to investigate target proteins (YAP and p-YAP Ser127) for the same donor. Each wedge was incubated with the primary antibody solution at 4 °C overnight and with the secondary antibodies at 37 °C for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with 2 µg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, D1306, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in DPBS at RT for 10 min. Three rinses in DPBS were performed between all steps, except between saturation of non-specific protein binding sites and incubation with primary antibody. Non-specific rabbit and mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Zymed, Carlsbad, CA) were used as primary antibodies for negative controls. The secondary antibodies were the same as for the targeted proteins in order to confirm the specificity of all markers. Flat-mounted corneas were covered with fluorescence mounting medium (NB-23-00158-2, Neobiotech, Nanterre, France) and then immobilized by a large glass coverslip. Images were acquired using an Olympus FV1200 Confocal Scanning Laser Microscope, CLSM (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with FV10-ASW4.1 imaging software. The objective employed was an Olympus UPlanSApo 60x/1.35 Oil ∞/0.17/FN26.5. Stacks were conducted three times per cornea for each target protein, generating orthogonal views from 15 to 20 image stacks. Excitation and intensity parameters remained consistent during image acquisition. For in vitro experiments on primary cells cultured from human corneas, images were acquired using an epifluorescence microscope (IX-81, Olympus, Japan) equipped with a × 40 objective.

Table 2.

List of antibodies used to study corneal endothelial cells on flat-mounted whole corneas.

| Target protein | Source | Isotype | Laboratory | Reference | Fixation | Secondary antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-YAP1 (63.7) | Mouse | IgG2a |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Germany |

sc-101199 | Methanol | Goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor™ 488, A32723, Invitrogen |

| Anti-phospho-YAP1, p-YAP; D9W2I (ser127) | Rabbit | / | Cell signaling Technology, Danvers MA | 13008S | PFA | Goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor™ 488, A11034, Invitrogen |

| Anti-ZO-1 | Rabbit | / | ThermoFisher Scientific Inc., USA | 40-2200 |

Methanol PFA |

Goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor™ 555, A21428, Invitrogen |

| Mouse | IgG1 | BD Bioscience, Belgium | 610967 | PFA |

1. Goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor™ 555, A11003, Invitrogen 2. Goat anti-mouse IgG1, Alexa Fluor™ 633, A21126, Invitrogen |

|

| Anti-acetylated α tubulin (6-11 B-1) | Mouse | IgG2b | Santa Cruz | sc-23950 | PFA |

1. Goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor™ 555, A11003, Invitrogen 2. Goat anti-mouse IgG2b, Alexa Fluor™ 555, A21147, Invitrogen |

Automated image processing

We analysed the relationship between the subcellular localization of YAP and p-YAP Ser127, based on three quantitative parameters serving as indirect indicators of endothelial quality, commonly employed in clinical practice and eye banking: ECD (cells/mm2), coefficient of variation of cell area (CV, in %), and hexagonality (%). These parameters were automatically quantified using the image analysis software, Image J (https://imagej.fr.softonic.com/telecharger). Briefly, stacked images subjected to automatic processing using Image J’s basic functions within a custom macro. This facilitate the reconstruction of stacked images for each of the three fluorescence channels: DAPI (405 nm), YAP and p-YAP Ser127 (455 nm), and ZO-1 (555 nm). ECD was determined by segmenting DAPI-stained nuclei using the Stardist plugin62,63. The mean ECD was then calculated from the three images per cornea. As in most corneal banks, we chose the threshold of 2000 cells/mm2 to define endothelial quality (high and low ECD). The CV and the hexagonality were calculated by analysing the ZO-1-labeled images, using a custom macro and the MorphoLibJ plugin for automated cell contour characterization64. The CV represented the standard deviation of each cell’s surface divided by the mean cell surface, indicating the degree of variation in endothelial cell size (polymegethism). A physiological coefficient of variation (CV) of less than 30% was observed alongside the absence of polymegethism. Hexagonality (HEX) corresponded to the percentage of cells with 6 neighbours.

Automated image processing was employed to quantify the subcellular localization of YAP and p-YAP Ser127 using fluorescence channels. We acquired three images per cornea, which were then segmented through image processing to quantify the subcellular localization of YAP. Nuclei and cytoplasm were identified using DAPI and ZO-1 labelling, respectively. The nuclear area was delineated from each cytoplasmic region. The fluorescence intensity (unitless) of YAP and p-YAP Ser127 was measured in both compartments. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of YAP staining was calculated for each cell. YAP localization was categorized as nuclear, cytoplasmic, or nuclear-cytoplasmic based on the ratio: equal distribution (C = N), predominantly nuclear (C < N), or predominantly cytoplasmic (C > N). The percentage of cells with each localization pattern was determined from the total number of analysed cells. In terms of subcellular localization of YAP, the total number of segmented cells for each group was as follows: Fresh (n = 683), Short (n = 585), and Long (n = 702). Regarding the nuclear distribution of p-YAP Ser127, the total number of segmented cells in each group was: Fresh (n = 646), Short (n = 1281), and Long (n = 1298). For the peri-membrane localization of YAP, the colocalization between ZO-1 and p-YAP was quantified using the Jacop extension module V2.1.465. Manual thresholding was applied to determine the fraction of ZO-1 containing p-YAP, indicating the percentage of overlap in p-YAP + ZO-1 staining. For the in vitro experiments on primary cells cultured from human corneas, we quantified the subcellular localization of YAP by manually selecting cells using the multi-point tool in ImageJ software. For the nucleocytoplasmic localization of YAP, the total number of selected cells for each group was as follows: cell density (ECD1: n = 87, ECD2: n = 167) and conditions with and without EDTA (n = 483 and n = 402, respectively).

Statistical analysis

To assess the impact of OC on quantified cellular morphological parameters, as well as the fluorescence intensity of YAP and p-YAP, the statistical significance was determined using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test; a p-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 7 software (La Jolla, CA, USA), and descriptive statistics were provided in terms of mean with standard deviation (SD). To analyse the differences in YAP labelling (percentage of cells with nuclear, nucleocytoplasmic, or cytoplasmic labelling) between the corneal groups, we used the Chi-square test. Percentages have been rounded to the nearest decimal for simplicity. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM.SPSS.statistics V28.0.0.0 (190).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the donors who did not oppose the donation of their corneas for scientific purposes, the doctors and nurses of the hospital coordination units for organ and tissue procurement at the University Hospitals of Saint-Etienne and Besancon, as well as Mr. Florian Bergandi from the Anatomy Laboratory at the Faculty of Medicine of Saint-Etienne.

Author contributions

H.V., O.B.M., G.T., and F.M. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. H.V., O.B.M., C.M, I.A, P.F., C.P., J.T., E.C, Z.H., and F.M. participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. H.V., O.B.M., C.P., G.T., and F.M. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. P.G., G.T., and F.M. supported the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. H.V., O.B.M., E.C and G.T. conducted the statistical analysis. G.T. and P.G. took part in obtaining funding. P.G., G.T., and F.M. played a role in administrative, technical, or material support.

Funding

Supported by Fondation de France, Bourse Berthe FOUASSIER 2020 (Hanielle VAITINADAPOULE) and ANR AAPG 2022 CORNEA (Jean-Yves & Gilles THURET).

Data availability

All relevant data is provided within the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hanielle Vaitinadapoulé and Olfa Ben Moussa contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82269-y.

References

- 1.Srinivas, S. P. Dynamic regulation of barrier integrity of the corneal endothelium. Optom. Vis. Sci.87, E239-254 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He, Z. et al. 3D map of the human corneal endothelial cell. Sci. Rep.6, 29047 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson, R. S. & Roper-Hall, M. J. Effect of age on the endothelial cell count in the normal eye. Br. J. Ophthalmol.66, 513–515 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Møller-Pedersen, T. A comparative study of human corneal keratocyte and endothelial cell density during aging. Cornea16, 333–338 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne, W. M., Nelson, L. R. & Hodge, D. O. Central corneal endothelial cell changes over a ten-year period. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.38, 779–782 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joyce, N. C. Proliferative capacity of the corneal endothelium. Prog. Retin Eye Res.22, 359–389 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Català, P. et al. Single cell transcriptomics reveals the heterogeneity of the human cornea to identify novel markers of the limbus and stroma. Sci. Rep.11, 21727 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, Q. et al. Heterogeneity of human corneal endothelium implicates lncRNA NEAT1 in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids27, 880–893 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pels, E. & Rijneveld, W. J. Organ culture preservation for corneal tissue. Technical and quality aspects. Dev. Ophthalmol.43, 31–46 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thuret, G. et al. Prospective, randomized clinical and endothelial evaluation of 2 storage times for cornea donor tissue in organ culture at 31 degrees C. Arch. Ophthalmol.121, 442–450 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borderie, V. M., Kantelip, B. M., Delbosc, B. Y., Oppermann, M. T. & Laroche, L. Morphology, histology, and ultrastructure of human C31 organ-cultured corneas. Cornea14, 300–310 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcin, T. et al. Innovative corneal active storage machine for long-term eye banking. Am. J. Transplant.19, 1641–1651 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albon, J., Tullo, A. B., Aktar, S. & Boulton, M. E. Apoptosis in the endothelium of human corneas for transplantation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.41, 2887–2893 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gain, P. et al. Value of two mortality assessment techniques for organ cultured corneal endothelium: trypan blue versus TUNEL technique. Br. J. Ophthalmol.86, 306 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sperling, S. Early morphological changes in organ cultured human corneal endothelium. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh)56, 785–792 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galgauskas, S., Norvydaitė, D., Krasauskaitė, D., Stech, S. & Ašoklis, R. S. Age-related changes in corneal thickness and endothelial characteristics. Clin. Interv. Aging8, 1445–1450 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doughty, M. J. Further analysis of the predictability of corneal endothelial cell density estimates when polymegethism is present. Cornea36, 973–979 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doughman, D. J., Van Horn, D., Rodman, W. P., Byrnes, P. & Lindstrom, R. L. Human corneal endothelial layer repair during organ culture. Arch. Ophthalmol.94, 1791–1796 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moya, I. M. & Halder, G. Hippo-YAP/TAZ signalling in organ regeneration and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.20, 211–226 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moroishi, T. et al. A YAP/TAZ-induced feedback mechanism regulates Hippo pathway homeostasis. Genes Dev.29, 1271–1284 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao, B. et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev.21, 2747–2761 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong, A. W. et al. Osmotic stress-induced phosphorylation by NLK at Ser128 activates YAP. EMBO Rep.18, 72–86 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang, J.-W. et al. RAC-LATS1/2 signaling regulates YAP activity by switching between the YAP-binding partners TEAD4 and RUNX3. Oncogene36, 999–1011 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehling, L. et al. Spatial modeling reveals nuclear phosphorylation and subcellular shuttling of YAP upon drug-induced liver injury. Elife11, e78540 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rausch, V. & Hansen, C. G. The hippo pathway, YAP/TAZ, and the plasma membrane. Trends Cell Biol.30, 32–48 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bazellières, E. et al. Control of cell-cell forces and collective cell dynamics by the intercellular adhesome. Nat. Cell Biol.17, 409–420 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tambe, D. T. et al. Collective cell guidance by cooperative intercellular forces. Nat. Mater.10, 469–475 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serra-Picamal, X. et al. Mechanical waves during tissue expansion. Nat. Phys.8, 628–634 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad, U. S., Uttagomol, J. & Wan, H. The Regulation of the Hippo Pathway by Intercellular Junction Proteins. Life (Basel)12, 1792 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jumelle, C. et al. Considering 3D topography of endothelial folds to improve cell count of organ cultured corneas. Cell Tissue Bank18, 185–191 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acquart, S. et al. Endothelial morphometry by image analysis of corneas organ cultured at 31°C. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.51, 1356–1364 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinoshita, N. et al. Force-dependent remodeling of cytoplasmic ZO-1 condensates contributes to cell-cell adhesion through enhancing tight junctions. iScience25, 103846 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nejepinska, J., Juklova, K. & Jirsova, K. Organ culture, but not hypothermic storage, facilitates the repair of the corneal endothelium following mechanical damage. Acta Ophthalmol.88, 413–419 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsueh, Y.-J. et al. Lysophosphatidic acid induces YAP-promoted proliferation of human corneal endothelial cells via PI3K and ROCK pathways. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev.2, 15014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das, A., Fischer, R. S., Pan, D. & Waterman, C. M. YAP nuclear localization in the absence of cell-cell contact is mediated by a filamentous actin-dependent, Myosin II- and Phospho-YAP-independent pathway during extracellular matrix mechanosensing. J. Biol. Chem.291, 6096–6110 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, J. et al. MAML1/2 promote YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.117, 13529–13540 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wada, K.-I., Itoga, K., Okano, T., Yonemura, S. & Sasaki, H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development138, 3907–3914 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu, M. et al. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.7, 376 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shreberk-Shaked, M. & Oren, M. New insights into YAP/TAZ nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling: new cancer therapeutic opportunities?. Mol. Oncol.13, 1335–1341 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon, H., Kim, J. & Jho, E. Role of the Hippo pathway and mechanisms for controlling cellular localization of YAP/TAZ. FEBS J.289, 5798–5818 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ege, N. et al. Quantitative analysis reveals that actin and Src-family kinases regulate nuclear YAP1 and its export. Cell Syst.6, 692-708.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim, S.-Y., Park, S.-Y., Jang, H.-S., Park, Y.-D. & Kee, S.-H. Yes-associated protein is required for ZO-1-mediated tight-junction integrity and cell migration in E-cadherin-restored AGS gastric cancer cells. Biomedicines9, 1264 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paramasivam, M., Sarkeshik, A., Yates, J. R., Fernandes, M. J. G. & McCollum, D. Angiomotin family proteins are novel activators of the LATS2 kinase tumor suppressor. Mol. Biol. Cell22, 3725–3733 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao, B. et al. Angiomotin is a novel Hippo pathway component that inhibits YAP oncoprotein. Genes Dev.25, 51–63 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao, S. et al. Phase separation of YAP mediated by coiled-coil domain promotes hepatoblastoma proliferation via activation of transcription. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.38, 1398–1407 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai, D. et al. Phase separation of YAP reorganizes genome topology for long-term YAP target gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol.21, 1578–1589 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blitzer, A. L. et al. Primary cilia dynamics instruct tissue patterning and repair of corneal endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.108, 2819–2824 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diagbouga, M. R. et al. Primary cilia control endothelial permeability by regulating expression and location of junction proteins. Cardiovasc. Res.118, 1583–1596 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim, J. et al. Actin remodelling factors control ciliogenesis by regulating YAP/TAZ activity and vesicle trafficking. Nat. Commun.6, 6781 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanioka, H., Shinomiya, K., Kinoshita, S. & Sotozono, C. Temperature effects on the disappearance and reappearance of corneal-endothelium primary cilia. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol.66, 481–486 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott, K. E., Fraley, S. I. & Rangamani, P. Transfer function for YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation revealed through spatial systems modeling. 2020.10.14.340349. 10.1101/2020.10.14.340349 (2020).

- 52.Scott, K. E., Fraley, S. I. & Rangamani, P. A spatial model of YAP/TAZ signaling reveals how stiffness, dimensionality, and shape contribute to emergent outcomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.118, e2021571118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novev, J. K., Heltberg, M. L., Jensen, M. H. & Doostmohammadi, A. Spatiotemporal model of cellular mechanotransduction via Rho and YAP. Integr. Biol. (Camb.)13, 197–209 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez Gonzalez, N. et al. Cell tension and mechanical regulation of cell volume. Mol Biol Cell29, 0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Garcin, T. et al. Three-month storage of human corneas in an active storage machine. Transplantation104, 1159–1165 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pels, E., Beele, H. & Claerhout, I. Eye bank issues: II. Preservation techniques: warm versus cold storage. Int. Ophthalmol.28, 155–163 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crewe, J. M. & Armitage, W. J. Integrity of epithelium and endothelium in organ-cultured human corneas. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.42, 1757–1761 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hermel, M., Salla, S., Fuest, M. & Walter, P. The role of corneal endothelial morphology in graft assessment and prediction of endothelial cell loss during organ culture of human donor corneas. Acta Ophthalmol.95, 205–210 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He, Z. et al. Corneal endothelial cell therapy: feasibility of cell culture from corneas stored in organ culture. Cell Tissue Bank22, 551–562 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forest, F. et al. Optimization of immunostaining on flat-mounted human corneas. Mol. Vis.21, 1345–1356 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He, Z. et al. Optimization of immunolocalization of cell cycle proteins in human corneal endothelial cells. Mol. Vis.17, 3494–3511 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt, U., Weigert, M., Broaddus, C. & Myers, G. Cell detection with star-convex polygons. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2018 (eds. Frangi, A. F., Schnabel, J. A., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C. & Fichtinger, G.) 265–273. 10.1007/978-3-030-00934-2_30 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

- 63.Weigert, M., Schmidt, U., Haase, R., Sugawara, K. & Myers, G. Star-convex polyhedra for 3D object detection and segmentation in microscopy. In 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) 3655–3662. 10.1109/WACV45572.2020.9093435 (2020).

- 64.Legland, D., Arganda-Carreras, I. & Andrey, P. MorphoLibJ: integrated library and plugins for mathematical morphology with ImageJ. Bioinformatics32, 3532–3534 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bolte, S. & Cordelières, F. P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc.224, 213–232 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is provided within the manuscript.